Abstract

The Eocene period experienced several hyperthermal events with the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum being the most significant. During this event, global mean surface temperatures were 5–6 °C higher and latitudinal temperature gradients were reduced compared to the late Paleocene. Unlike marine temperature records, terrestrial archives are limited, posing challenges for testing climate model competence in simulating the magnitude and spatial patterns of temperature change under a high carbon dioxide climate. Here we analysed mudstone paleosols from the Tremp Group in Spain to reconstruct soil temperatures using carbonate nodules. Clumped isotopes revealed median calcification temperatures of 33.9 and 39.2 °C for the Late Paleocene and Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, respectively. The findings suggest a ~5 °C summer soil temperature increase during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Continental proxy and model data indicate reduced (0.7–0.4 °C/degree) meridional temperature gradients between 25 and 75°N latitudes, indicating more uniform heat distribution across latitudes than at present.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superimposed on the generally warm late Paleocene (LP) climate, the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM, ~56 Ma) was a 170–200 thousand year (kyr) long hyperthermal event1,2, when deep ocean and sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were globally 4–5 °C warmer than over the LP3,4,5. Although the PETM onset occurred near a 405-kyr eccentricity maximum, suggesting an orbital trigger2,6, it is most likely to be driven by geologically rapid (3–5 kyr)7 addition(s) of large amounts (~3000–10,000 Pg C) of 13C-depleted CO2 to the carbon reservoirs of the Earth surface7,8,9,10, most probably originating from volcanism associated with the North Atlantic Igneous Province11,12,13,14. Both proxy and model evidence document a substantial alteration of the hydrological cycle15,16,17 and intensified chemical weathering18,19 associated with global warming over the PETM.

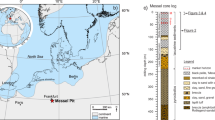

Not only SSTs20, but also the much sparsely available continental temperature proxy data indicate reduced latitudinal thermal gradients21,22,23 and warm continental interiors24,25 under the early Eocene greenhouse climate. However, the locations where climate change over the Paleocene–Eocene (P–E) boundary is reliably resolved using quantitative proxy data are limited and are unevenly distributed in space26. The relatively sparse proxy network hinders the derivation of the spatial patterns of temperature changes across the PETM and proxy-model data comparison. To fill one of these gaps, we provide temperature estimates using the clumped isotope composition (Δ47) of soil carbonates (SCs) collected in the Esplugafreda sedimentary record, Spain, a well-known and investigated subtropical (paleolatitude ~32.3°N; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) continental record of climate and hydrological cycle changes across the P–E boundary15,27,28,29,30. The upper Maastrichtian to lower Ypresian terrestrial deposits of the Tremp Group at Esplugafreda is made up of ~250 m of red/grey/yellow mudstones with abundant paleosols, deposited in a coastal alluvial setting15,27,31. The paleosols, which are dominantly cumulative in nature32, contain widespread centimetre-sized, pedogenic soil nodules and gypsum indicating a semi-arid to arid paleoenvironment with seasonal precipitation15. The P–E boundary is located near the top of the continental section (Fig. 2), based on a pronounced negative carbon isotope excursion (CIE) found in soil carbonates15,33. The CIE spans more than 15–20 m of yellow cumulate paleosols formed during the PETM (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). The post-PETM interval in the Esplugafreda section comprises 20 m of red paleosols rich in gypsum and characterised by normal soil nodule δ13C values15,28,30.

a Synthetic lithostratigraphy and soil carbonate δ13C isotope profile of the Paleocene–Eocene interval (after Payros et al.30, modified from Pujalte et al.28) with (b) a field photo of the Esplugafreda and Claret Formation members in the western part of the Esplugafreda sector (from Pujalte et al.28).

Alluvial deposits of the Esplugafreda section were formed in a climatically sensitive region at the northernmost part of the subtropical zone, a latitudinal belt fringing the temperate climate zone. Indeed, vertisols of the Esplugafreda Formation (EF) attest climatic regime shifts from Mediterranean to subtropical monsoon climate over the LP31 and even more profound climate change from temperate, humid subtropical climate with hot summers (Köppen-Geiger climate class: Cfa) to tropical climate across the P–E boundary34. Climatic swings of this magnitude must have been preserved in soil carbonates, which provide the only means of quantitatively reconstructing temperature changes and precipitation δ18O values for this key site over the LP and PETM. Carbonate clumped isotope thermometry35,36 allows paleotemperature reconstructions without requiring independent estimates of the oxygen isotope composition of soil water (i.e. precipitation) from which the carbonate grew. Pedogenic carbonates are assumed to form in isotopic equilibrium with soil CO2 and water37. Local environmental and soil conditions, including soil temperature (Tsoil), moisture and pCO238, are the major controls on the stable carbon and oxygen isotopic compositions of soil carbonate (δ13Ccarb, δ18Ocarb), which provide a time-integrated record of these parameters over hundreds to thousands of years of carbonate formation. While vegetation, soil productivity/CO2 and soil temperature and water isotopic compositions define δ13Ccarb and δ18Ocarb37,39, Tsoil is the only factor that determines clumped isotope compositions of soil carbonates (Δ47-carb)40,41. Soil carbonate formation usually follows frequent dewatering and CO2 outgassing events during warm/dry episodes of the summer season38, causing a warm season bias in carbonate growth and thus SC-derived clumped isotope temperatures (TΔ47-carb)40,41,42,43,44. A warm-season biased carbonate formation is likely valid for the mudstone paleosols (vertisols) of the Esplugafreda sedimentary record, as soil pCO2 is dominantly controlled by cracking and shrink-swell processes in vertisols, occurring during late spring and summer45. In summary, Δ47-carb is a promising proxy for quantifying the magnitude of warming recorded in continental sediments at Esplugafreda over the LP and PETM and understanding the climatic response of the former subtropical Pyrenean region to high CO2 conditions. Furthermore, the TΔ47-carb proxy data can be useful to assess model competence of the Deep Time Model Intercomparison Project (DeepMIP)46 and contribute to paleoclimate data assimilation to improve estimates of the magnitude and spatial patterns of climatic changes during the PETM26.

We find that the mudstone paleosols of the Esplugafreda record contained carbonate nodules with internal features suggesting near-surface precipitation and high Mn2+ content, indicating reducing conditions potentially related to temporary aquic soil conditions. The PETM was marked by clear CIEs of ~–2.0‰ in organic matter and –5.5‰ in soil carbonates. Clumped isotope analyses of these nodules revealed calcification temperatures being in interquartile ranges of 27.5–37.1 °C for the LP and 35.3–41.2 °C for the PETM. Calculated median soil temperatures were 33.9 °C and 39.2 °C for the LP and PETM intervals, respectively, suggesting a significant soil warming of ~5 °C during the PETM when excluding potential seasonal effects on carbonate formation.

Results

Sediment grain size, mineralogy and organic matter δ13C

The grain size distributions (GSDs) of the Esplugafreda sediments are relatively uniform throughout the record (Supplementary Fig. 5). In general, GSDs are uni- to polymodal, dominantly fine skewed with the mode/mean in the coarse silt/very fine sand fraction (Fig. 3). The sediments are poorly sorted and belong to the sandy mud/muddy sand textural groups and sandy silt/silty sand category (Supplementary Fig. 6). Mudstone paleosols of the EF between 140 and 110 m composite depth were found to be much finer (mean grain size (MGS): 15–35 µm) than the overlying deposits, which exhibit significant internal variations in MGS between 20 and 80 µm without clear grain size trends (Fig. 3).

AL alveolina limestone, Ivf incised valley fill, CC claret conglomerate, YS yellowish soils, GrU gypsum-rich unit, UrU upper red unit; kln kaolinite, ilt illite, POE pre-onset excursion, CIE carbon isotope excursion based on δ13Ccarb and δ13Corg. CIEorg1-2 and CIEcarb are defined in the text. Error bars of soil carbonate calcification temperatures represent 95% CL.

The clay mineral assemblage of the upper Paleocene sediments is dominated by illite and smectite (45 ± 7, 40 ± 7 wt%) with smaller amounts of kaolinite and chlorite (7 ± 2, 8 ± 1 wt%, Supplementary Dataset 1). Clay mineralogy of the incised valley fill resembles that of upper Paleocene mudstone paleosols (Supplementary Fig. 7). By contrast, the PETM yellowish soils are lower in illite (31 ± 6 wt%) but have more smectite and kaolinite (48 ± 6, 12 ± 2 wt%), which is also reflected in elevated kaolinite/illite (klt/ilt) and smectite/(illite + chlorite) (sme/(ilt + chl)) ratios (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Dataset 1). The Upper reddish Unit sediments show relatively smectite-poor compositions with higher illite contents (65–66 wt%).

Organic matter δ13C of the EF mudstone paleosols of LP age vary around a median (Q2) value of –25.19 ‰ and exhibit a weak negative trend towards the younger sediments (Fig. 3). The incised valley fill deposits generally show more positive δ13Corg values compared to the underlying EF paleosols (median: –24.86‰), with a negative excursion exceeding 1‰. The PETM yellowish soils provide the most negative δ13Corg values in the entire record, sometimes lower than –27‰, fluctuating around a median value of –26.83‰. The calculated CIEorg1 and CIEorg2 values, which are based on the difference between the median δ13Corg values of incised valley fill (Ivf), LP and PETM sediments, are –1.97‰ and –1.64‰, clearly identifying the body of PETM. Paleosols of the Gypsum-rich Unit and Upper reddish Unit display heavier carbon isotope compositions again.

Soil carbonate petrography

In general, soil carbonates originating from LP paleosols of the EF are slightly larger (1–2 cm) in size than those of the PETM yellowish soils (0.5–1 cm, Supplementary Fig. 8a). All investigated SCs exhibit features of the alpha-type end-member47, dominantly consisting of dense, continuous, non-porous micritic groundmass incorporating clay to silt-sized (Supplementary Fig. 8b, d) or rarely sand-sized (Supplementary Fig. 8e) floating framework grains. Some SCs include zones of displacive/replacive spars and microspars potentially resulting from dissolution/recrystallisation of some micrite (e.g. Supplementary Fig. 8d). Few SCs comprise coalesced larger calcite crystals cemented by sparry calcite (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Cracking features are absent. CL images of most SCs show bright, relatively homogeneous orange to reddish cathodoluminescence of calcite groundmass (Supplementary Fig. 8b, d, e), sometimes with less bright or even dull luminescence when calcites are coarser-grained (Supplementary Fig. 8c). This latter form very rarely occurs and only in EF paleosols.

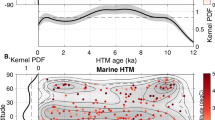

Soil carbonate stable carbon, oxygen and clumped isotope compositions

Following a thorough review of our measurement datasets, a single sample (ITS/W-YS7, 8-16 July 2022) was selected for which isobaric contamination could not be excluded. Consequently, the results of this carbonate sub-sample were not considered further. Soil carbonates of the EF yield δ13Ccarb values between –8.55 and –5.85 ‰, while the PETM yellowish soil carbonates are significantly more negative (–13.84 to –10.12 ‰). The CIEcarb value, calculated as the difference between the median δ13Ccarb values of LP (EF, –6.93 ‰) and PETM carbonates (YS, –12.44 ‰), is –5.51 ‰ (Fig. 4a). A much smaller, –1.40 ‰ difference can be observed in the oxygen isotope compositions of these two SC populations (δ18Ocarb: –5.54 to –4.13 in LP versus –6.15 to –5.81 ‰ in YS; Fig. 4), which almost disappears when SC-derived soil water δ18O values are considered (Fig. 4b).

a, b Carbon and oxygen isotope compositions and c, d clumped isotope temperatures. See Table 1 for stable isotope data and sample information. Note that error bars are in many cases smaller than symbols. Q2 denotes the median values, and the carbon isotope excursion (CIE) in (a) is based on the difference of median δ13Ccarb values of LP and PETM carbonates. Soil water δ18O data displayed on (b) were calculated from δ18Ocarb and TΔ47-carb values as defined in Table 1. In (c, d) the colour shadings represent the interquartile range (Q1–Q3) of the soil carbonate temperatures (TΔ47-carb), with the median value (Q2) indicated. Error bars of soil carbonate calcification temperatures represent 95% Cl. More information is provided in the text.

The statistical analysis of Δ47-based paleotemperatures (TΔ47-carb) provide a median soil carbonate formation of 33.9 °C with an interquartile (Q1-Q3) range of 27.5–37.1 °C during the LP (Fig. 4c, d), considering all Δ47-carb measurements of EF carbonates. By contrast, much higher temperatures were recorded by soil carbonates of the PETM yellowish soils (median: 39.2 °C), with a much higher interquartile range (35.3–41.2 °C) than over the LP. As demonstrated by a two-sided Wilcoxon ranksum and Kruskal-Wallis test (Supplementary Table S1), the calculated medians are different, and the TΔ47-carb values of LP and PETM carbonates do not originate from the same distribution at the 95% confidence level. Both the difference in the median values (5.3 °C) and the positive shift in the interquartile range provide evidence for significant warming of soils over the PETM.

Paleoclimate simulation results

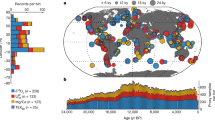

Near-surface air temperatures derived for the paleo-location of the Esplugafreda site using eight Earth system models of the DeepMIP for 280–1680 ppm atmospheric CO2 concentrations demonstrate increasing monthly temperatures, with mean annual and summer season air temperatures (MAT, TJJA) between 19.6 and 29.6 (280–1120 ppm), as well as 26.8–38.4 °C (280–1120 ppm) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 9). Model results indicate seasonal variations in temperature rise, with the winter season warming being more intense than for the summer season (Supplementary Fig. 10). Simulated precipitation rates do not vary much between 280 and 840 ppm CO2 levels (mean annual precipitation/MAP: 905–972 mm) with the highest rates/values over the summer and early autumn (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 11). Ensemble means of the simulations run for more extreme PETM-like CO2 concentrations provided smaller (1120 ppm) and much higher (1680 ppm) precipitation rates and MAP (585 and 1372 mm), especially for June to October (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 10).

a near-surface air temperature and (b) daily precipitation. Model data displayed are ensemble means of eight Earth system models of DeepMIP45. Reconstructed (soil carbonate-based) TJJA values for the LP and PETM are also shown for comparison.

The DeepMIP models demonstrate that the meridional temperature distribution also changes significantly with increasing CO2 concentration (Fig. 6), particularly in the extratropical region. The simulation results are otherwise in relatively good agreement with the continental proxy data for the LP (2–3 × CO2) and PETM (4–6 × CO2), particularly in regions <50°N latitude. Proxy data from higher latitudes (50–77°N) suggest that continental warming modelled at the highest CO2 levels underestimates values that were characteristic at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary, although the sparseness of the proxy data makes this observation uncertain. At low CO2 levels (1× CO2), the meridional (latitudinal) temperature gradient (Fig. 6a) is around the present-day value of 0.8–1.0 °C/deg. between 25 and 75°N latitudes. However, at higher CO2 concentrations, the thermal gradient declines to ~0.6–0.7 °C/deg. between 25 and 50°N, and even to 0.4 °C/deg. between 50 and 75°N.

a Mean annual temperatures (MAT) and (b) summer mean temperatures (TJJA) as a function of latitude. Modelled temperatures are from DeepMIP simulations and represent the ensemble means (lines) with one standard deviation (shaded areas). Proxy-based temperatures are from the literature (see Supplementary Dataset 2) and this study. Error bars of proxy temperature data represent 2 sigma uncertainties. Proxy symbols with bold frames denote summer-biased MAT.

Discussion

Sedimentary environment and soil carbonate formation in the Esplugafreda record

Terrestrial deposits of the Esplugafreda and Claret Formations record sedimentation in changing alluvial environments under a generally arid/semi-arid climate during the LP and early Eocene28,29,30. Two successive pedotypes were described in mudstone paleosols (basically vertisols) of the EF representing Mediterranean climate with arid soil conditions (Pont d’Orrit pedotype) followed by monsoon climate with aquic soil conditions (Areny pedotype)31. Over the PETM, formation of the Claret Conglomerate demonstrates a substantially enhanced hydrological cycle and high kaolinite influx implies higher continental physical erosion rates15,27. Our grain size data indicate that the LP and PETM paleosols are basically very similar in terms of soil textures, but the Pont d’Orrit pedotype is characterised by finer grain size at the base (140–110 m) of the EF. Whether this relates to the different climate regime (Mediterranean, Pont d’Orrit pedotype) and/or the alluvial environment in which these soils formed is unclear. The significantly increased klt/ilt and sme/(ilt + chl) ratios in the PETM yellowish soils (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Dataset 1) further confirm observations of Schmitz and Pujalte27, and in line with their interpretation, it is most probably attributable to higher detrital input of kaolinite and smectite from deeper physical erosion of rocks in the hinterland.

The form and size of collected soil nodules (Supplementary Fig. 8) and the presence of a suite of carbonate textures such as floating silicate grains and micrite-microspar fabrics implies that the studied carbonates originated from near-surface precipitation48. However, carbonate nodules in mudstones may be pedogenic or the result of shallow groundwater invasion of the vadose zone, and little or no difference exists in their petrographic character49. The mostly bright, orange to reddish cathodoluminescence of calcite groundmass (Supplementary Fig. 8) of the studied carbonates is indicative of elevated Mn2+ concentrations50 and precipitation under low-Eh (i.e. reducing) conditions51. These observations imply that the investigated nodules may have dominantly formed in stagnant water under temporary aquic conditions, in agreement with the abundant redoximorphic features in EF vertisols31 and frequent purple mottling of the yellowish soils (Supplementary Fig. 4c–e), demonstrating imperfectly or poorly drained paleosol conditions52 for most of the year. As such, soil carbonates may have formed during warmer, drier periods when soil pCO2 was reduced. In this process, stagnant soil water became supersaturated in Ca ions, leading to carbonate precipitation under water-logged conditions. However, it is also conceivable that stagnant water may have potentially disappeared completely from the soil for shorter periods. In vertisols, soil CO2 (and soil moisture) is controlled by soil crack porosity and ultimately by shrink-swell processes, which are amplified during dry periods (typically late spring to summer)45. For these reasons, it seems very likely that although soil carbonate Δ47 values in fine-grained soils often reflect MAT53,54, in vertisols, shrink-swell phenomena (and cracking) are the primary drivers of pedogenic carbonate precipitation. Consequently, the TΔ47-carb values are most likely warm-season biased temperatures.

CIE recorded in organic matter and soil carbonates

Estimates of the PETM carbon cycle perturbation rely on the magnitude of CIE associated with this hyperthermal event1. However, there is a discrepancy between CIE values preserved in marine sediment organic matter (2–5‰)1 and continental soils (3–7‰)55. Likewise, terrestrial organic matter and soil carbonates record systematic differences in CIE magnitudes56. In our δ13Corg dataset, both the LP and PETM sediment carbon isotope values are slightly more negative than those measured by Manners et al.55 for the Esplugafreda record, but the calculated CIEorg1 (–1.97‰, Fig. 3) is in good correspondence with the previously established CIE magnitude of ~2‰. This provides further evidence that the yellowish soils represent the body of PETM. More positive values around –25‰ of the Gypsum-rich Unit potentially mark the recovery phase of the PETM28,30. A striking feature of the δ13Corg record is the more positive values of incised valley fill sediments compared to the EF paleosols and the ~1.5‰ negative shift within the Ivf deposits. The so-called pre-onset excursion (POE), which marks the first massive carbon release right before the PETM10, was identified in Ivf carbonates33. Considered in isolation, the negative δ13Corg excursion in Ivf sediments resembles the POE. However, even the most negative values of this potential POE are not more negative than most of the δ13Corg of EF paleosols (Fig. 3). Thus, in contrast to δ13Ccarb of Tremblin et al.33, our δ13Corg dataset does not provide unambiguous evidence for the appearance and preservation of the POE in the Esplugafreda record. Unfortunately, soil carbonates were not found in and analysed from the Ivf sediments.

Compared to the organic matter δ13C record, the δ13Ccarb values obtained from SCs yield a more than 2 times larger average CIEcarb (–5.51 ‰, Fig. 4a), although this value was calculated from SCs collected in the mudstone paleosols of the EF (LP) and yellowish soils (PETM) and did not include carbonates from Ivf sediments. This is surprisingly consistent with a CIEcarb of –5.7 ‰ recorded in paleosol carbonates at Polecat Bench, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming10. The 3.9‰ difference in CIEorg2 and CIEcarb in our records exceeds that (~2‰) preserved in organic matter and soil nodules in paleosols of the Bighorn Basin56. The discrepancy between CIE values based on δ13Corg and δ13Ccarb in the interpretation of Gallagher et al.56 is most probably caused by increased soil respiration rates and/or a seasonal shift in carbonate formation and less likely by soil methane oxidation.

Soil water δ18O and temperature reconstructions for the LP/PETM

Measured soil nodule δ18Ocarb values indicate a relatively small, 1.4‰ negative shift (calculated from the medians) in SCs formed over the PETM compared to LP nodules (Fig. 4a, d). This is, however, an effect of calcification temperatures, as the calculated δ18Osoil-w values representing local precipitation δ18O only reflect minor changes (median offset: –0.31‰) in the source water oxygen isotope compositions (Fig. 4b). Absolute δ18Osoil-w values dominantly vary within the range of ~–3 to +3‰ for both SC populations of LP and PETM age. The limited shift in precipitation δ18O across the P–E boundary is basically very similar to modelled surface ocean Δδ18O (–0.5 to –1 ‰) around the Iberian Peninsula over the LP to PETM57 and may indicate that precipitation sources did not change much in this interval.

SC calcification temperatures (TΔ47-carb) for both intervals (LP and PETM) were found to be in a broad range between 20.5 ± 9.3 and 58.2 ± 8.9 °C (error: 95% CL), with interquartile ranges of LP and PETM carbonates within 27.5–37.1 and 35.3–41.2 °C (Fig. 4c). While some SCs were found to be relatively homogeneous in terms of recorded formation temperatures (e.g. ITS-EF sc 5.3 or ITS/E-YS9, Table 1), others were heterogeneous with significant internal variations in TΔ47-carb exceeding 10–15 °C (e.g. ITS-EF sc 19.9, ITS/E-YS13). Repeat measurements on SCs yielding very low or high TΔ47-carb values (e.g. ITS/W-YS10, ITS/E-YS13 or ITS-EF sc 26.40) usually gave calcification temperatures close to or within the interquartile range of TΔ47-carb values characteristic for the central groups of carbonates. The effect of (1) isobaric contaminants and (2) kinetic fractionation are among the potential reasons for the sometimes large internal variations of TΔ47-carb. Geological reasons may include (3) reprecipitation of micritic carbonate during shallow burial and subsequent exhumation of Esplugafreda sediments, (4) carbonate growth at changing depths in the paleosols over hundreds to thousands of years of nodule formation, and (5) a seasonal shift in SC growth.

It is well-known that N2O, hydrocarbons, chlorinated hydrocarbons and sulphur-bearing contaminants may cause isobaric interference during Δ47 analyses of CO258,59,60. A recent study demonstrated that nitrate-derived NO2 constitutes an isobaric interferent for the extracted CO2 for some carbonates, which cannot be effectively removed during gas purification and may cause –Δ47/ + Δ48 bias, leading to an overestimation of formation temperatures61. In our soil carbonate clumped isotope dataset, no clear relationship was found between Δ48 WG (PBL) and calcification temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Datasets 3-4). This observation implies that a robust correlation between the measured elevated Δ48 WG (PBL) values and possible nitrate contamination of the studied carbonate samples cannot be demonstrated with the analytical system employed. Since Fiebig et al.61 found that the ETH-3 standard is affected by nitrate contamination a bleaching experiment was performed in October 2024 using 1 ml 2.5% NaOCl on 30 mg ETH-3 samples with a reaction time of 8 h. Altogether, 20 replicates of bleached ETH-3 were measured, using non-bleached ETH-3 (along with ETH-1 and ETH-2) as standard during the data processing. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, the Δ47 values of bleached (0.618 ± 0.013‰) and non-bleached (0.613 ± 0.006‰) ETH-3 statistically overlap with the reference Δ47 value of ETH-3 (0.6132‰). Considering these findings, the elevated temperatures obtained for some carbonates are unlikely to be the result of nitrate contamination or at least this cannot be detected using our measurement system. Consequently, no objective criteria were found to exclude these values from the interpretations.

Regarding explanation (2) CO2 degassing via bicarbonate dehydration, which is the dominant reaction at typical soil pH levels during carbonate precipitation, may often result in disequilibrium isotope signatures with 13C and 18O enrichment and lower Δ47 values in calcite relative to the expected equilibrium isotope composition44,62,63. Guo64 developed a model of kinetic isotope fractionations associated with bicarbonate dehydration. This model predicts that, at 25 °C, for every 1‰ increase in calcite δ18O, there is a corresponding 3.26‰ increase in δ13C and a ~0.022‰ decrease in Δ47. Given the findings of Guo64 the sometimes substantial (>10 °C) temperature variations measured in certain soil carbonates are predicted to result in several permil shifts in δ13C and δ18O within a single carbonate. By contrast, soil carbonates were found to be very homogeneous in terms of carbon and oxygen isotope compositions (Table 1). Furthermore, an anomalous increase in calcification temperatures (lower Δ47) due to kinetic fractionation would be expected to be associated with higher δ13C and δ18O values for these sub-samples. However, such a positive relationship appears not to be evident in the data shown in Fig. 4c, d. Thus, while kinetic effects cannot be ruled out entirely for the unusually high calcification temperatures, they do not appear to be significant for these subsamples.

As for explanation (3), several SCs incorporate zones of sparry calcite, and while we focussed on micro-sampling micritic carbonate, potentially unintentionally sampled fractions of sparry calcite invisible at that scale. Regarding explanation (4), it may have a limited effect on SC temperatures as the development of cumulate soils is associated with low sedimentation rates (0.05–0.5 mm/yr)31,32. Therefore, considering continuous aggradation and zero surface erosion of soils, a growing nodule gets to a deeper position in the soil profile at a rate of 5–50 cm/1000 years, leading to a small to moderate (on the order of <~5 °C) temperature effect especially when formation occurs >30–50 cm41. Explanation (5) will be discussed below.

Since we consider all the reported data in Table 1 analytically correct (except for one, see above) we calculated soil temperatures from the full dataset, yielding median values of 33.9 and 39.2 °C for the LP and PETM. According to this scenario, the full range of TΔ47-carb is considered valid, including seemingly anomalous values. Provided that formed close (<20 cm) to the soil surface, some TΔ47-carb values exceeding 40 °C may record real Tsoil due to radiative heating of the ground surface40,41 under the extreme warm conditions and sparse vegetation30 of the LP and PETM at Esplugafreda. Based on the above figures, a significant soil temperature warming on the order of ~5 °C is obtained for the PETM, provided that there was no significant seasonal shift in SC formation between the LP and PETM intervals.

Comparison of proxy-based and simulated temperatures: implications for PETM warming and latitudinal temperature gradients

Simultaneous air and ground surface temperature measurements demonstrate a strong coupling between these two climatic parameters under modern climatic conditions65. The temperature difference between the two variables was found to be 2.47 K on average, exhibiting a seasonal variation with ~1–4 K difference over the winter and summer seasons due to changing incident solar radiation66. Subsequent studies concluded that soil radiative heating is limited, <2 K for clayey soils67 and <3 °C for most soils below 50 cm68. In another study, Molnar69 established relationships between Tsoil and MAT (ΔTsoil–MAT) for various land surface covers on theoretical grounds and using FLUXNET2015 datasets. Dependent on surface wetness/aridity, ΔTsoil–MAT was found to be between 1 and 4 °C for shrublands and 1–3 °C for grasslands. However, these values are given for the soil surface, while soil nodules do not usually form close to the ground surface (<20–50 cm). Based on this fact and previous evidence for sparse vegetation and prevailing arid/semi-arid climate with seasonal precipitation at the Esplugafreda site over the LP and PETM intervals30,31, we considered a Tsoil–air temperature difference of 0–3 °C to put our Tsoil average values in a paleoclimate modelling context.

Mean summer air temperatures at the Esplugafreda site must have been around 30.9–33.9 °C over the LP, calculating with the median TΔ47-carb value and subtracting 0–3 °C as discussed above. In comparison with DeepMIP model ensembles of near-surface air temperatures (Fig. 5), these values agree well with the summer season temperatures (TJJA) of the DeepMIP × 2 simulation for a CO2 concentration of 560 ppm and is slightly lower than those of DeepMIP × 3 (840 ppm), which is closer to the 900 ± 100 ppm CO2 estimate for the pre-PETM interval70. For the PETM, the mean summer air temperature is estimated to be 36.2–39.2 °C (same approach), in good correspondence with both the DeepMIP ×4 and ×6 (1120 and 1680 ppm) simulation results for the summer season. As such, this provides evidence for a summer season bias for SC growth, which would be expected considering the warm temperatures and excessive evaporation and drying (potentially after larger precipitation infiltration events44; Fig. 5b) during the June to August period simulated for the study region in front of the Pyrenees71. Since the mean soil and air temperatures obtained from both SC populations of LP and PETM age seem to reflect summer season temperatures, it is less likely that the temperature differences reconstructed between the LP and PETM intervals at Esplugafreda would have been caused by a significant seasonal shift in carbonate formation. Thus, the ~+5 °C mean warm-season anomaly between the LP and PETM found at Esplugafreda is regarded as a robust estimate, which matches well the simulated range of 4–6 °C of mean summer temperature warming in this region26,71. A recent study has reconstructed a slightly smaller warming of ~3 °C between the POE (24.2 ± 1.0 °C) and the PETM (27.0 ± 0.8 °C) using the hydrogen and oxygen isotope compositions of smectites72. However, this is not an estimate for the summer season, rather, it represents the difference in MATs. In order to make a comparison of the PETM temperature values reconstructed by the two different methods, we use the MAT-TJJA relationship calculated from the DeepMIP models (see Supplementary Fig. 13). The smectite-based MAT of 27.0 ± 0.8 °C reconstructed by Jaimes-Gutierrez et al.72 yields a TJJA value of 34.8 ± 3.7 °C, which statistically overlaps with the mean TJJA range of 36.2–39.2 °C calculated from soil carbonates in this study.

The available continental temperature proxy data indicate that the late Palaeocene, and in particular the PETM, was not only a period of significantly higher temperatures than the present day, but that the climate at the Palaeocene-Eocene boundary was characterised by a more even distribution of heat across latitudes than at present21. The latest Eocene DeepMIP climate models clearly demonstrate this reduced meridional surface temperature gradient22,46,73, showing relatively good agreement with the continental proxy data (Fig. 6). In particular, models run for CO2 levels typical of the LP and early Eocene demonstrate a significantly reduced temperature gradient (0.4–0.5 °C/deg.) for the region between 50 and 75°N latitudes. However, the proxy data suggest an even smaller continental thermal gradient, closer to the latest estimate (~0.3 °C/deg.)23.

Methods

Depositional setting, stratigraphy and sampling

The Tremp-Graus Basin developed as a piggy-back basin during the early Paleogene74, which was located at ~32.3°N paleolatitude and preserves terrestrial clastic deposits, informally named “Garumnian” (formally: Tremp Group) and composed of the Thanetian to early Ypresian age Esplugafreda and Claret Formations28,75. These continental deposits interfinger to the west with lacustrine and shallow marine carbonates30 and are under-/overlain by the transitional Aren Sandstone Formation (Maastrichtian) and the shallow marine “Alveolina limestone” (lower Ypresian) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1)28.

The 165–350 m thick, alluvial EF is made up of cumulative red mudstone paleosols (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) and contains numerous multi-episodic channel-like bodies of calcareous conglomerates and calcarenites (Schmitz and Pujalte, 2007). The paleosols contain abundant centimetre-sized soil nodules and gypsum, and the two pedotypes (Pont d’Orrit and Areny) recognised by Basilici et al.31 belong to the vertisol order. An erosion surface associated with the incision of a valley network defines the boundary between the Esplugafreda and Claret Formations28,29.

The 10–70 m thick Claret Formation is composed of a suite of mudstones, sandstones, and conglomerates, with local gypsum accumulations and consists of five members28. Member 1 comprises the deposits, mostly grey calcarenites and marlstones to red marls, infilling several incised valleys30. Member 2 is a 0.5-7 m thick30, extensive, sheet-like conglomeratic unit with clasts dominantly in the 20–40 cm range28, called the Claret Conglomerate (CC) (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). The CC has been suggested to be deposited either by braided rivers29,63 or an alluvial megafan15, the latter interpretation implying a dramatic change in the hydrological cycle at the PETM onset. Member 3, the Yellowish Soils (YS), is up to 20 m thick and consists of yellowish silty mudstones with purple mottling (Supplementary Fig. 4) and dispersed, small-sized (0.5–1 cm) carbonate nodules, with intercalated sandstone bodies28,30. Member 4, the Gypsum-rich Unit (GrU), is represented by red mudstones with gypsum occurring either as veins, root-like concretions, or centimetre sized nodules28. Member 5, the Upper reddish Unit (UrU), which only exists at Esplugafreda, is up to 17 m thick and is made up of red mudstone with dispersed carbonate nodules. The overlying “Alveolina limestone” (AL) is a time-transgressive marine unit, which onlaps member 5 at Esplugafreda30.

Bulk sediment samples were collected in ~1 m resolution for grain size, mineralogical and organic matter carbon isotope analyses from sections #1–3 and 5 (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), representing the Esplugafreda and Claret Formations. A composite profile was created using sections #1, 2 and 5, with the Claret Conglomerate being the reference horizon, while sedimentological and geochemical data from sections #3 and #7 are not discussed in this study. Soil carbonates for clumped isotope analyses were exclusively collected in section #5 (EF) in irregular intervals and sections #4 and #6 (Claret Formation, Member 3: Yellowish Soils) in ~0.3 and ~1 m resolution (Supplementary Fig. 2). Most paleosols of the EF and the yellow soils are cumulative in nature, implying that these soil profiles are generated by slow and continuous sedimentation32. This process leads to gradual overprinting as the soil profile aggrades and the paleosol profile boundaries are diffuse and not marked by deposits or erosional surfaces31. Consequently, the depth of soil carbonate formation cannot be constrained.

Grain size and mineralogical analyses

Prior to laser diffraction measurements, samples (~3 g) were pretreated with 10 ml 20% H2O2 and 10 ml 10% HCl to remove organic matter and carbonates. Subsequently, samples were mixed with 10 ml of 0.05 N Na(PO3)6, and ultrasonicated for about 1 min. Grain size of bulk sediment samples was analysed using a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 laser diffractometer at the Szentágothai Research Centre (SRC), University of Pécs. This instrument has a measurement range of 0.01–3500 μm, divided into 100 size bins. Constants of 1.33 for the refractive index of water, 1.544 for the refractive index of solid phases, and an absorption index of 0.1 were applied. Bulk grain size analyses reported in this study are the averages of three successive laser diffraction runs, and the Malvern Mastersizer 3000 software (version 3.10) was used to transform diffraction data to grain size based on the Mie Scattering Theory. Grain size statistics (mean, median) and the volume percentage values of various grain size fractions were calculated from the Mastersizer 3000 software outputs using the latest 9.1 version of GRADISTAT76.

Bulk and clay mineralogical analyses were performed at the Institute for Geological and Geochemical Research (IGGR, HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Budapest). The clay fraction (<2 μm) was separated by wet sedimentation after hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid treatments by adding 10% H2O2 and 10% CH3COOH to the samples sequentially until suspension no longer effervesced. The remaining material was then sedimented on glass slides for X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis following a modified USGS methodology77. Samples were subject to ethylene-glycol solvation (at 60 °C, overnight) and heating at 550 °C (1 h) for diagnosing smectite and kaolinite. XRD measurements were performed on a RIGAKU Miniflex 600 equipment at 45 kV voltage and 35 mA current applying a graphite monochromator with CuKα radiation. The 2θ range was set to 2–70° and a counting speed of 0.05°/2 s was applied for the analyses. The Rigaku PDXL2 software was used for phase identification based on the ICDD database. Quantitative analyses of bulk mineralogy were carried out with full profile fitting combined with Rietveld refinement using the SiroQuant V4.0 software. Clay mineral compositions were determined on sedimented samples by semi-quantitative phase analysis following the method of Biscaye78.

Petrography

Internal structures of half-cut soil carbonates were investigated by a Nikon SMZ 800N stereomicroscope. Cathodoluminescence (CL) analysis of SCs was performed using a Reliotron cold-cathode equipment mounted on a Nikon E600 polarizing microscope. The equipment operated at 5–10 kV accelerating voltage and 0.4–1.2 mA current. CL images were obtained using a defocused electron beam and a Nikon Coolpix 4500 digital camera with automatic exposure.

Organic matter carbon isotope analysis

Bulk sediment samples (~2.5 g each) were powdered and treated with 10% HCl to remove carbonates until the effervescence (CO2 formation) ceased. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged and washed three times in distilled water and dried in an oven at ~60–65 °C. The dried samples were powdered again and 2.5-3 mg aliquots were packed in Sn capsules for stable carbon isotope measurements performed at the IGGR. Samples were combusted using an Organic Elemental Analyzer (Thermo Scientific, Rhodano, Italy) and the yielded gases were transferred via a Conflo III into an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta V Advantage, Thermo Finnigan) operating in continuous flow mode with a carrier gas of He + O2 and flow speed of 90 ml/min. A two-point linear normalisation was applied to recalculate raw isotope values to the VPDB scale79 by measuring reference standards IAEA-CH-6 (δ13C: −10.45‰) and IAEA-CH-7 (δ13C: −32.151‰)80. Standard deviation of the reference standards were <0.06‰ (IAEA-CH-6, n = 114) and <0.05‰ (IAEA-CH-7, n = 116) for δ13C. Each unknown sample was measured three times and the average carbon isotope ratios of the bulk organic matter are reported in permil (‰) using the δ-notation.

Soil carbonate carbon, oxygen and clumped isotope analyses

Stable carbon, oxygen and clumped isotope analyses of soil carbonates were performed at the HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research (ATOMKI), on a Thermo ScientificTM 253 Plus 10 kV high-resolution Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer following phosphoric acid digestion at 70 °C using a Thermo Scientific Kiel IV automatic carbonate device, which is coupled by inert silica coated capillary to the IRMS. For the digestion, 3 drops of 1.95 g/cm3 phosphoric acid were applied on each carbonate sample. An additional Thermo Scientific™ PoraPak Unit is installed between the two cold fingers of the Kiel IV device, the first one being a water trap and cold finger whereas the second one is a preparation cold finger. The role of the PoraPak column is to decrease organic contamination of the extracted CO2 gas. This column is filled with PoraPak™ Q 50–80 mesh porous polymer adsorbent and sealed with glass wool at both ends. The trap operation temperature is –30 °C and an hour long regeneration process is done at 120 °C following the measurement of a full sample magazine. After cryogenic purification the CO2 gas is measured against a working CO2 gas (Linde AG, δ13CV-PDB = –3.9 ‰, δ18OV-PDB = –12.5 ‰, purity = 99.998%) for m/z 44-49 in micro-volume inlet mode and following the long integration dual inlet (LIDI) method81,82.

Aliquots of 100–140 μg of each unknown sample, collected using a dental drill from the visually most homogeneous, micritic parts of the soil carbonates, were replicated 8–16 times (12 on average) and measured alongside carbonate standards (100–110 μg). For some carbonates a second/third aliquot was also used representing a different sub-sample of the sample powder from the same drilling. For two carbonates (ITS/E-YS1 and YS9), numerous independent samples were drilled at several points across the carbonate interior (labelled d1-d3 in Table 1), and thus these aliquots represent different domains of the same soil carbonate.

The pressure-sensitive baseline (PBL) correction method of Bernasconi et al.83 was applied to correct the raw beam signals for negative background caused by secondary electrons on higher Faraday-cup detectors. The PBL correction algorithm, which is implemented in the Easotope software (Release 20190125)84, used peak scans at four different intensities. Our methodology followed the full carbonate-based standardisation scheme85 using the ETH-1, ETH-2, and ETH-3 InterCarb calcite standards86. Consequently, Δ47 values are presented on the I-CDES scale (Intercarb-Carbon Dioxide Equilibrium Scale)86. Corrections for ion-source non-linearity effects were done using measured ETH-1 and ETH-2 values, while the transfer function to I-CDES was determined using ETH-1, ETH-2, and ETH-3. IAEA-C2 was used as a monitoring sample to determine long-term reproducibility, which was found to be between 0.030 and 0.032‰ (1 SD) during the measurement periods. The 1 SD uncertainties of ETH-1, 2 and 3 carbonate standards ranged between 0.029–0.032‰, 0.028–0.032‰ and 0.029–0.031‰. Alongside the clumped isotope analyses, the conventional carbonate stable isotope compositions of the studied samples were also determined using ETH-1, ETH-2 and ETH-3 as normalisation standards87. The applied δ18O (70 °C) acid fractionation factor for calcite was 1.00870904388.

Data evaluation, standardisation, and analytical error propagations of clumped isotope measurements were performed following the CO2 Clumped ETH PBL replicate analysis method using the revised IUPAC parameters for 17O correction89. Soil carbonate calcification temperatures in °C were calculated using the Δ47-temperature calibration of Anderson et al.90. The temperature uncertainties were propagated from the 95% CL of the Δ47 value and the uncertainties of the calibration equation.

Paleoclimate simulation data

For a qualitative comparison of the soil carbonate Δ47-based temperatures with paleoclimate model outputs, paleotemperature and precipitation data were obtained from standardised simulations of the early Eocene climate, carried out in the framework of the DeepMIP46. Simulation data used represent ensemble means of eight Earth system models run for different atmospheric CO2 concentrations (DeepMIP 1×-4 and 6×: 280, 560, 840, 1120 and 1680 ppm), plus an associated preindustrial control simulation (piControl: 280 ppm CO2). Model data were specifically extracted for the paleolatitude of the Esplugafreda site using the DeepMIP online interface at https://data.deepmip.org/91. For the calculation of simulated continental heat distribution and meridional (latitudinal) thermal gradients, 2 m air temperature data of all available model runs for each scenario were considered. Note that the number of simulations varies for the different scenarios46. All simulations were bilinearly interpolated onto a common grid with 3.75° longitude × 2.5° latitude to compute an ensemble mean for each scenario. Then, the zonal mean and standard deviation of the ensemble mean continental temperature were calculated.

Proxy data of LP and PETM continental paleotemperatures of the northern hemisphere are from published literature including leaf physiognomic data23,92,93, the MBT′/CBT organic mineral soil temperature proxy25,94,95,96 and lignite brGDGT data97, as well as mammal δ18O98, smectite δ18O and δ2H72, and soil carbonate clumped isotope data24,99. The primary criteria for selecting proxy data were that it should be chronologically well-defined for the LP or PETM period and indicative of MAT or TJJA. Paleolatitude of each proxy site was calculated using paleolatitude.org100 with the Vaes et al.101 paleomagnetic reference frame.

Data availability

All data reported in this paper are available in the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/15629019. Paleoclimate model data in the framework of DeepMIP is freely available via the CEDA data archive91 (https://archive.ceda.ac.uk/about/).

References

McInerney, F. A. & Wing, S. L. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: a perturbation of carbon cycle, climate, and biosphere with implications for the future. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 39, 489–516 (2011).

Zeebe, R. E. & Lourens, L. J. Solar System chaos and the Paleocene–Eocene boundary age constrained by geology and astronomy. Science 365, 926–929 (2019).

Tripati, A. & Elderfield, H. Deep-sea temperature and circulation changes at the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Science 308, 1894–1898 (2005).

Sluijs, A. et al. Subtropical Arctic Ocean temperatures during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum. Nature 441, 610–613 (2006).

Dunkley-Jones, T. et al. Climate model and proxy data constraints on ocean warming across the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Earth Sci. Rev. 125, 123–145 (2013).

Piedrahita, V. A. et al. Orbital phasing of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 598, 117839 (2022).

Turner, S. K. Constraints on the onset duration of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170082 (2018).

Zachos, J. C., Dickens, G. R. & Zeebe, R. E. An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 451, 279–283 (2008).

Zeebe, R. E., Zachos, J. C. & Dickens, G. R. Carbon dioxide forcing alone insufficient to explain Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum warming. Nat. Geosci. 2, 576–580 (2009).

Bowen, G. J. et al. Two massive, rapid releases of carbon during the onset of the Palaeocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Nat. Geosci. 8, 44–47 (2015).

Storey, M., Duncan, R. A. & Swisher, C. C. Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum and the opening of the Northeast Atlantic. Science 316, 587–589 (2007).

Saunders, A. D. Two LIPs and two Earth-system crises: the impact of the North Atlantic Igneous Province and the Siberian Traps on the Earth-surface carbon cycle. Geol. Mag. 153, 201–222 (2016).

Gutjahr, M. et al. Very large release of mostly volcanic carbon during the Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nature 548, 573–577 (2017).

Kender, S. et al. Paleocene/Eocene carbon feedbacks triggered by volcanic activity. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–10 (2021).

Schmitz, B. & Pujalte, V. Abrupt increase in seasonal extreme precipitation at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary. Geology 35, 215–218 (2007).

Carmichael, M. J., Pancost, R. D. & Lunt, D. J. Changes in the occurrence of extreme precipitation events at the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 501, 24–36 (2018).

Rush, W. D., Kiehl, J. T., Shields, C. A. & Zachos, J. C. Increased frequency of extreme precipitation events in the North Atlantic during the PETM: observations and theory. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 568, 110289 (2021).

Ravizza, G., Norris, R. N., Blusztajn, J. & Aubry, M.-P. An osmium isotope excursion associated with the late Paleocene Thermal Maximum: evidence of intensified chemical weathering. Paleoceanography 16, 155–163 (2001).

Pogge von Strandmann, P. A. E. et al. Lithium isotope evidence for enhanced weathering and erosion during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh4224 (2021).

Evans, D. et al. Eocene greenhouse climate revealed by coupled clumped isotope-Mg/Ca thermometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1174–1179 (2018).

Greenwood, D. R. & Wing, S. L. Eocene continental climates and latitudinal temperature gradients. Geology 23, 1044–1048 (1995).

Huber, M. & Caballero, R. The early Eocene equable climate problem revisited. Clim. Past 7, 603–633 (2011).

van Dijk, J. et al. Spatial pattern of super-greenhouse warmth controlled by elevated specific humidity. Nat. Geosci. 13, 739–744 (2020).

Snell, K. E. et al. Hot summers in the Bighorn Basin during the early Paleogene. Geology 41, 55–58 (2013).

Naafs, B. D. A. et al. High temperatures in the terrestrial mid-latitudes during the early Palaeogene. Nat. Geosci. 11, 766–771 (2018).

Tierney, J. et al. Spatial patterns of climate change across the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205326119 (2022).

Schmitz, B. & Pujalte, V. Sea-level, humidity, and land-erosion records across the initial Eocene thermal maximum from a continental-marine transect in northern Spain. Geology 31, 689–692 (2003).

Pujalte, V., Schmitz, B. & Baceta, J. I. Sea-level changes across the Paleocene–Eocene interval in the Spanish Pyrenees, and their possible relationship with North Atlantic magmatism. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 393, 45–60 (2014).

Colombera, L., Arévalo, O. J. & Mountney, N. P. Fluvial-system response to climate change: the Paleocene-Eocene Tremp Group, Pyrenees, Spain. Global Planet. Change 157, 1–17 (2017).

Payros, A., Pujalte, V. & Schmitz, B. Mid-latitude alluvial and hydroclimatic changes during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum as recorded in the Tremp-Graus Basin, Spain. Sediment. Geol. 435, 106155 (2022).

Basilici, G. et al. Variations from dry to aquic conditions in Vertisols (Esplugafreda Formation, Eastern Pyrenees, Spain): implications for late Paleocene climate change. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 595, 110972 (2022).

Wright, V. P. & Marriott, S. B. A quantitative approach to soil occurrence in alluvial deposits and its application to the Old Red Sandstone of Britain. J. Geol. Soc. London 153, 907–913 (1996).

Tremblin, M. et al. Mercury enrichments of the Pyrenean foreland basins sediments support enhanced volcanism during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum (PETM). Glob. Planet. Change 212, 103794 (2022).

Korasidis, V. A., Wing, S. L., Shields, C. A. & Kiehl, J. T. Global changes in terrestrial vegetation and continental climate during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 37, e2021PA004325 (2022).

Ghosh, P. et al. 13C–18O bonds in carbonate minerals: a new kind of paleothermometer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 1439–1456 (2006).

Eiler, J. M. Paleoclimate reconstructions using carbonate clumped isotope thermometry. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 3575–3588 (2011).

Cerling, T. E. & Quade, J. Stable carbon and oxygen isotopes in soil carbonates. In Climate Change in Continental Isotopic Records Vol. 78 (eds Swart, P.K., Lohmann, K.C., McKenzie, J. & Savin, S.) 217–231 (AGU, 1993).

Breecker, D. O., Sharp, Z. D. & McFadden, L. D. Seasonal bias in the formation and stable isotopic composition of pedogenic carbonate in modem soils from Central New Mexico, USA. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 121, 630–640 (2009).

Cerling, T. E. The stable isotopic composition of modern soil carbonate and its relationship to climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 71, 229–240 (1984).

Passey, B. H., Levin, N. E., Cerling, T. E., Brown, F. H. & Eiler, J. M. High-temperature environments of human evolution in East Africa based on bond ordering in paleosol carbonates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11245–11249 (2010).

Quade, J., Eiler, J., Daëron, M. & Achyuthan, H. The clumped isotope geothermometer in soil and paleosol carbonate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 105, 92–107 (2013).

Peters, N. A., Huntington, K. W. & Hoke, G. D. Hot or not? Impact of seasonally variable soil carbonate formation on paleotemperature and O-isotope records from clumped isotope thermometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 361, 208–218 (2013).

Hough, B. G., Fan, M. & Passey, B. H. Calibration of the clumped isotope geothermometer in soil carbonate in Wyoming and Nebraska, USA: implications for paleoelevation and paleoclimate reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 391, 110–120 (2014).

Burgener, L. et al. Variations in soil carbonate formation and seasonal bias over>4 km of relief in the western Andes (30°S) revealed by clumped isotope thermometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 441, 188–199 (2016).

Breecker, D. O. et al. CO2 concentrations in vertisols: seasonal variability and shrink-swell. In New Frontiers in Paleopedology and Terrestrial Paleoclimatology: Paleosols and Soil Surface Analog Systems Vol. 104 (eds Driese, S.G., Nordt, L.C. & McCarthy, P.J.) 35–45 (SEPM Special Publications, 2013).

Lunt, D. J. et al. DeepMIP: model intercomparison of early Eocene climatic optimum (EECO) large-scale climate features and comparison with proxy data. Clim. Past 17, 203–227 (2021).

Wright, V. P. A micromorphological classification of fossil and recent calcic and petrocalcic microstructures. In Soil Micromorphology: A Basic and Applied Science (ed. Douglas, L.A.) 401–407 (Elsevier, 1990).

Pimentel, N. L., Wright, V. P. & Azevedo, T. M. Distinguishing early groundwater alteration effects from pedogenesis in ancient alluvial basins: examples from the Palaeogene of southern Portugal. Sed. Geol. 105, 1–10 (1996).

Mack, G. H., Cole, D. R. & Trevino, L. The distribution and discrimination of shallow, authigenic carbonate in the Pliocene–Pleistocene Palomas Basin, southern Rio Grande rift. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 112, 643–656 (2000).

Hemming, N. G., Meyers, W. J. & Grams, J. C. Cathodoluminescence in diagenetic calcites: the roles of Fe and Mn as deduced from electron probe and spectrophotometric measurements. J. Sediment. Petrol. 59, 404–411 (1989).

Mintz, J. S., Driese, S. G., Breecker, D. O. & Ludvigson, G. A. Influence of changing hydrology on pedogenic calcite precipitation in Vertisols, Dance Bayou, Brazoria County, Texas, USA: implications for estimating paleoatmospheric pCO2. J. Sediment. Res. 81, 394–400 (2011).

Kraus, M. J. & Hasiotis, S. T. Significance of different modes of rhizolith preservation to interpreting palaeoenvironmental and palaeohydrologic settings: examples from Palaeogene palaeosols, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, U.S.A. J. Sediment. Res. 76, 633–646 (2006).

Kelson, J. R. et al. A proxy for all seasons? A synthesis of clumped isotope data from Holocene soil carbonates. Quat. Sci. Rev. 234, 106259 (2020).

Havranek, R., Snell, K., Brookins, S. & Davidheiser-Kroll, B. Timing of pedogenic carbonate formation in fine-grained soils: decoupled T(Δ47) and δ18Ow seasonal bias. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 40, e2024PA005071 (2025).

Manners, H. R. et al. Magnitude and profile of organic carbon isotope records from the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum: evidence from northern Spain. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 376, 220–230 (2013).

Gallagher, T. M., Cacciatore, C. G. & Breecker, D. O. Interpreting the difference in magnitudes of PETM carbon isotope excursions in paleosol carbonate and organic matter: oxidation of methane in soils versus elevated soil respiration rates. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 2113–2128 (2019).

Zhu, J. et al. Simulation of early Eocene water isotopes using an Earth system model and its implication for past climate reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 537, 116164 (2020).

Eiler, J. M. & Schauble, E. 18O13C16O in Earth’s atmosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 4767–4777 (2004).

Huntington, K. W. et al. Methods and limitations of ’ clumped’ CO2 isotope (Δ47) analysis by gas-source isotope ratio mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 44, 1318–1329 (2009).

Bergmann, K. D. et al. A paired apatite and calcite clumped isotope thermometry approach to estimating Cambro-Ordovician seawater temperatures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 224, 18–41 (2018).

Fiebig, J. et al. Carbonate clumped isotope values compromised by nitrate-derived NO2 interferent. Chem. Geol. 670, 122382 (2024).

Tripati, A. K. et al. Beyond temperature: clumped isotope signatures in dissolved inorganic carbon species and the influence of solution chemistry on carbonate mineral composition. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 166, 344–371 (2015).

Burgener, L. K. et al. Clumped isotope constraints on equilibrium carbonate formation and kinetic isotope effects in freezing soils. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 235, 402–430 (2018).

Guo W. Carbonate Clumped Isotope Thermometry: Application to Carbonaceous Chondrites and Effects of Kinetic Isotope Fractionation. Phd thesis, California Institute of Technology (2009).

Melo-Aguilar, C. et al. Near-surface soil thermal regime and land–air temperature coupling: a case study over Spain. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 7516–7534 (2021).

Bartlett, M. G., Chapman, D. S. & Harris, R. N. A decade of ground-air temperature tracking at Emigrant Pass Observatory, Utah. J. Clim. 19, 3722–3731 (2006).

Cermak, V., Bodri, L., Kresl, M., Dedecek, P. & Safanda, J. Eleven years of ground–air temperature tracking over different land cover types. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 1084–1099 (2016).

Burgener, L. K., Hyland, E. G., Huntington, K. W., Kelson, J. R. & Sewall, J. O. Revisiting the equable climate problem during the Late Cretaceous greenhouse using paleosol carbonate clumped isotope temperatures from the Campanian of the Western Interior Basin, USA. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 516, 244–267 (2019).

Molnar, P. Differences between soil and air temperatures: implications for geological reconstructions of past climate. Geosphere 18, 800–824 (2022).

Anagnostou, E. et al. Proxy evidence for state-dependence of climate sensitivity in the Eocene greenhouse. Nat. Commun. 11, 4436 (2020).

Kiehl, J. T., Shields, C. A., Snyder, M. A., Zachos, J. C. & Rothstein, M. Greenhouse and orbital-forced climate extremes during the early Eocene. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170085 (2018).

Jaimes-Gutierrez, R. et al. Deciphering Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum climatic dynamics: insights from oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in clay minerals of Paleosols from the Southern Pyrenees. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 39, e2024PA004858 (2024).

Lunt, D. J. et al. A model–data comparison for a multi-model ensemble of early Eocene atmosphere–ocean simulations: EoMIP. Clim. Past 8, 1717–1736 (2012).

Chanvry, E. et al. The influence of intrabasinal tectonics in the stratigraphic evolution of piggyback basin fills: towards a model from the Tremp-Graus-Ainsa Basin (South-Pyrenean Zone, Spain). Sediment. Geol. 377, 34–62 (2018).

Dreyer, T. Quantified fluvial architecture in ephemeral stream deposits of the Esplugafreda Formation (Paleocene), Tremp-Graus Basin, northern Spain. In Alluvial Sedimentation Vol. 17 (eds Marzo, M. & Puigdefábregas, C.) 337–362 (IAS Special Publication, 1993).

Blott, S. J. & Pye, K. GRADISTAT: a grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 26, 1237–1248 (2001).

Poppe, L. J., Paskevich, V. F., Hathaway, J. C. & Blackwood, D. S. A laboratory manual for X-ray powder diffraction. Open-File Report 2001-41, USGS (2001).

Biscaye, P. E. Mineralogy and sedimentation of recent deep-sea clay in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas and oceans. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 76, 803–832 (1965).

Paul, D., Skrzypek, G. & Fórizs, I. Normalization of measured stable isotope composition to isotope reference scale – a review. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 21, 3006–3014 (2007).

Coplen, T. B. et al. New guidelines for δ13C measurements. Anal. Chem. 78, 2439–2441 (2006).

Hu, B. et al. A modified procedure for gas-source isotope ratio mass spectrometry: the long-integration dual-inlet (LIDI) methodology and implications for clumped isotope measurements. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 28, 1413–1425 (2014).

Müller, I. et al. Carbonate clumped isotope analyses with the long-integration dual-inlet (LIDI) workflow: scratching at the lower sample weight boundaries. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 31, 1057–1066 (2017).

Bernasconi, S. M. et al. Background effects on Faraday collectors in gas source mass spectrometry and implications for clumped isotope measurements. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 27, 603–612 (2013).

John, C. M. & Bowen, D. Community software for challenging isotope analysis: first applications of ‘Easotope’ to clumped isotopes. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 2285–2300 (2016).

Meckler, A. N. et. al. Long-term performance of the Kiel carbonate device with a new correction scheme for clumped isotope measurement. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 28, 1705–1725 (2014).

Bernasconi, S. M. et al. InterCarb: a community effort to improve inter-laboratory standardization of the carbonate clumped isotope thermometer using carbonate standards. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 22, e2020GC009588 (2021).

Bernasconi, S. M. et al. Reducing uncertainties in carbonate clumped isotope analysis through consistent carbonate-based standardization. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 2895–2914 (2018).

Kim, S.-T., Coplen, T. B. & Horita, J. Normalization of stable isotope data for carbonate minerals: implementation of IUPAC guideline. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 158, 276–289 (2015).

Schauer, A. J., Kelson, J., Saenger, C. & Huntington, K. W. Choice of 17O correction affects clumped isotope (Δ47) values of CO2 measured with mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 2607–2616 (2016).

Anderson, N. T. et al. A unified clumped isotope thermometer calibration (0.5–1100 °C) using carbonate-based standardization. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL092069 (2021).

Steinig, S. et al. Deep-Time Model Intercomparison Project (DeepMIP) Eocene model data version 1.0. NERC EDS Centre for Environmental Data Analysis, https://doi.org/10.5285/95aa41439d564756950f89921b6ef215 (2024).

Kowalski, E. A. & Dilcher, D. L. Warmer paleotemperatures for terrestrial ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 167–170 (2003).

Sunderlin, D. et al. Paleoenvironment and paleoecology of a Late Paleocene high-latitude terrestrial succession, Arkose Ridge Formation at Box Canyon, Southern Talkeetna Mountains, Alaska. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 401, 57–80 (2014).

Weijers, J. W., Schouten, S., Sluijs, A., Brinkhuis, H. & Damsté, J. S. S. Warm arctic continents during the Palaeocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 261, 230–238 (2007).

Sluijs, A. et al. Warming, euxinia and sea level rise during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum on the Gulf Coastal Plain: implications for ocean oxygenation and nutrient cycling. Clim. Past 10, 1421–1439 (2014).

Schoon, P. L., Heilmann-Clausen, C., Schultz, B. P., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. & Schouten, S. Warming and environmental changes in the eastern North Sea Basin during the Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum as revealed by biomarker lipids. Org. Geochem. 78, 79–88 (2015).

Collinson, M. E. et al. Palynological evidence of vegetation dynamics in response to palaeoenvironmental change across the onset of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum at Cobham, Southern England. Grana 48, 38–66 (2009).

Fricke, H. C. & Wing, S. L. Oxygen isotope and paleobotanical estimates of temperature and δ18O-latitude gradients over North America during the Early Eocene. Am. J. Sci. 304, 612–635 (2004).

Kelson, J. R. et al. Warm terrestrial subtropics during the Paleocene and Eocene: carbonate clumped isotope (Δ47) evidence from the Tornillo Basin, Texas (USA). Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 1230–1249 (2018).

van Hinsbergen, D. J. J. et al. A paleolatitude calculator for Paleoclimate studies. PLoS ONE 10, e0126946 (2015).

Vaes, B. et al. A global apparent polar wander path for the last 320 Ma calculated from site-level paleomagnetic data. Earth Sci. Rev. 245, 104547 (2023).

Kim, S.-T. & O’Neil, J. R. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium oxygen isotope effects in synthetic carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3461–3475 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH) through the K-137767 OTKA project. A.P. received funding from the State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Spain (PID2019-105670GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades). K.H.S. thanks the AXA Research Fund for support. Sampling permissions were not required. Insightful and constructive comments of the three anonymous reviewers improved the paper substantially and are much appreciated.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. Újvári devised the project, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. S. Kele helped with funding acquisition and contributed to data analysis. L. Rinyu performed the clumped isotope measurements and verified the datasets. A. Payros provided help with field work and sampling, and together with V. Pujalte and B. Schmitz contributed to geological interpretations; V. Pujalte, B. Schmitz and S.M. Bernasconi supervised the project. Kim H. Stadelmaier did the post-processing of DeepMIP model outputs. J. Kovács conducted grain size analyses, I. Kovács did XRD measurements and B. Bajnóczi performed CL imaging. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Feifei Zhang, Carolina Ortiz Guerrero and Aliénor Lavergne. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Újvári, G., Kele, S., Rinyu, L. et al. Substantial continental temperature rise over the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum in the Pyrenees. Commun Earth Environ 6, 499 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02479-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02479-8