Abstract

Latitudinal variations in the carbon:nitrogen (C:N) ratio of particulate organic matter are well-established, but vertical (depth) variations within the euphotic zone remain largely unexplored. Here, we found that C:N ratios (mol:mol) of three size fractions of particulate organic matter exceeded the canonical Redfield ratio of 6.6 within the low-nutrient upper euphotic zone in the stratified northwest Sargasso Sea. In larger particles ( >20 μm), these ratios reached as high as 10–16. Elevated C:N ratios in all size fractions of particles (0.3 to >20 μm) in the upper euphotic zone coincided with the accumulation of glucose-rich carbohydrates. In contrast, particles within or below the nitracline, within the lower euphotic zone (~90–140 m), exhibited C:N ratios of <6.6 and contained comparatively less carbohydrate and greater amounts of amino acids. Additionally, patterns in the composition of individual carbohydrate monomers suggest that the vertical variations originate from both primary production and degradative processes. These variations in particle composition over depth will affect the stoichiometry in models of primary production, microbial remineralization, and carbon export.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Particulate organic matter (POM) in the ocean plays important roles in sequestering carbon in the deep ocean, maintaining the global climate, and providing nutrition for microbial and metazoan communities1. POM is comprised of living autotrophic and heterotrophic cells as well as non-living detrital material (i.e., cell debris, zooplankton molts, fecal pellets, organic gels, etc.)2. Primary production of POM mainly occurs within the euphotic zone by phytoplankton, but environmental conditions during primary production, secondary POM sources, and degradative alteration can result in substantial variations in POM chemical composition across time, space, and particle size fractions3,4. POM can be remineralized and solubilized by microbes, consumed or broken apart by zooplankton, or exported from the euphotic zone via sinking flux or advection. The chemical constituents of POM vary in their reactivity5, and POM of different sizes may be subjected to different degradative pathways6,7. Therefore, both the chemical composition and particle size can influence POM export potential as well as the rate and mechanism of POM utilization.

A common metric of particle chemical composition is the ratio of organic carbon to nitrogen (OC:N, henceforth simplified as C:N). Historically, this ratio was found to be relatively constant in marine POM, approximately 106:16 (≈6.6) on a molar basis, forming part of what is known as the Redfield ratio8. Subsequent studies have identified large variations (C:N < 6–10) over latitude in the surface ocean and attributed these to variations in the products of primary production caused by spatial variations in nutrient stress, light limitation, and phytoplankton community composition3,9. Despite variations in these same parameters over depth, there has been little exploration of vertical (depth) variations in C:N ratios of POM. Some individual studies have found higher C:N ratios below the euphotic zone compared to within it10,11,12, but few studies discuss vertical variations within the euphotic zone, where most POM is produced and where vertical export originates.

The C:N stoichiometry of POM influences the efficiency of export as well as the biogeochemical outcomes of its remineralization. Export of POM with an elevated C:N ratio is more efficient in terms of carbon export13 and yields relatively less nitrogen upon remineralization, affecting subsequent nitrogen assimilation and nitrification. The composition of organic matter also influences the stoichiometric oxygen demand required for its remineralization14,15. Thus, C:N stoichiometry is an important parameter in biogeochemical models. Though some models use fixed (Redfield) ratios for phytoplankton and POM16,17,18,19, there is growing recognition that adopting variable stoichiometry is important for properly predicting oceanic responses to continued warming20,21,22,23. Improved understanding of the magnitude of depth-related variations may help guide future modeling efforts that include variable stoichiometry24.

The C:N ratios of POM are controlled by the relative amounts of different classes of biochemicals, including amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids. Each biochemical class exhibits varying levels of lability5 and is broken down by different enzymes during heterotrophy25. Thus, the biochemical makeup of POM dictates which metabolic capabilities are required for heterotrophic microbes to assimilate or remineralize the material, and some microbial populations may preferentially respond to POM of specific chemical composition26. Many studies report concentrations of amino acids or carbohydrates in marine POM27,28,29,30,31,32, as they are common and accessible substrates for heterotrophic bacteria to assimilate and/or remineralize due to their prevalence in biomass33 and relative lability5. One recent study identified broad shifts in biochemical composition associated with variations in C:N over a latitudinal gradient34; however, few studies discuss these parameters in the context of their relationship to varying C:N ratios or focus on variations over depth within the euphotic zone35,36. Furthermore, common oceanographic methods, such as collecting bulk POM from Niskin bottles, do not differentiate particle sizes, which can have unique organic compositions and may contribute differently to export and nutritional resources for heterotrophs. Therefore, characterization of biomolecular content within size-fractionated POM provides deeper insight into the potential biogeochemical implications of both the production and fate of this material.

Here, we present a unique dataset in which we examine the stoichiometric composition of POM (1) at high depth resolution within the euphotic zone, (2) as it specifically relates to carbohydrate (high C:N) and amino acid (low C:N) content, and (3) within small particles (0.3–1.2 and 1.2–6 μm) and large particles (>20 μm). We collected samples using McLane in situ pumps within a thermally stratified euphotic zone during several cruises in summer and autumn in the vicinity of the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) site. The site is located within the North Atlantic subtropical gyre and is an example of the open-ocean environments that comprise most of the global ocean area. Employing methods to measure organic carbon and nitrogen concentrations (elemental analysis) and individual carbohydrate monomers and amino acids (high-performance liquid chromatography), we observe significant variations in C:N ratios and biochemical composition of POM across depth and size fraction during multiple sampling periods. We also examine the relative and absolute abundances of individual amino acids and carbohydrate monomers across samples to better understand the drivers of observed biochemical variations over depth and size fraction and propose pathways of organic matter alteration over depth. The resulting data elucidate previously unidentified features of POM composition within the euphotic zone and may inform and/or validate biogeochemical modeling efforts.

Results and discussion

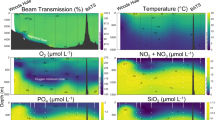

Mixed layer depths, nutrient concentrations, and the size distribution of POM

Samples were collected from cruises aboard the R/V Atlantic Explorer in July 2018, July 2019, August 2021, November 2021, July 2022, and July 2023 (Supplementary Table 1). Mixed layer depths varied between 16–24 m for all cruises except November 2021, when the mixed layer extended to 73 m (see Methods). Nitrate concentrations, defined here as [NO3-] + [NO2-], were below the limit of detection (0.2 μmol kg-1; see Methods) in the upper 80 m of the water column during almost all sampling events from all cruises, including sampling in November when the mixed layer was deepest (Fig. 1). Phosphate concentrations were below the limit of detection (0.1 μmol kg−1) throughout the euphotic zone (0–160 m) during all cruises with few exceptions (Supplementary Fig. 1). The euphotic depth, defined here as the depth at which irradiance was 0.1% of that at the surface, ranged between 136–200 m (Supplementary Table 1). For simplicity, we define the upper euphotic zone as 0–80 m and the lower euphotic zone as 80−160 m across data from all cruises based on the typical depth of the nitracline (Fig. 1).

Dotted and solid lines represent the average mixed layer depth and euphotic depth, respectively, during each cruise. Between 11 and 20 individual profiles are compiled for each cruise. Limit of detection is 0.2 μmol kg−1; concentrations reported below this limit are statistically indistinguishable from blanks and are shown in gray, while concentrations measured above the limit of detection are plotted in blue. Most of the data points in the upper 80 m were indistinguishable from blanks.

The particulate organic carbon (POC) and nitrogen (PN) content of size-fractionated POM was measured for samples from all cruises. The size fractions collected were 0.3–1.2 μm, 1.2–6 μm, 6–20 μm, and >20 μm (see Methods). All size fractions were analyzed except for the 6–20 μm size fraction, which did not regularly contain enough material to make reliable measurements. Total POC and PN concentrations were calculated from the sum of the three analyzed size fractions (Methods). Maximum concentrations of POC (~19–24 μg L−1) were found at ~40–80 m for all cruises except November 2021, where concentrations were relatively constant at ~15 μg L−1 throughout the upper 50 m (Supplementary Fig. 2). POC concentrations for all cruises decreased to <5 μg L−1 by 140 m (Supplementary Fig. 2). Maximum concentrations of PN (~3–4 μg L-1) were found at 60-90 m for all cruises except November 2021, where concentrations were approximately constant at ~2.4 μg L-1 throughout the upper 90 m (Supplementary Fig. 2). On average, 24 ± 5%, 68 ± 5%, and 8 ± 4% of total PN and 22 ± 5%, 64 ± 9%, and 14 ± 7% of total POC were contained within the 0.3–1.2 μm, 1.2–6 μm, and >20 μm size fractions, respectively, within the upper 200 m (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Underexplored variability in C:N ratios across particle size fractions and depth in the euphotic zone

We observed systematically higher C:N ratios in the low-nutrient upper euphotic zone than in the lower euphotic zone within all size fractions of POM during our six cruises (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.001; Figs. 2, 3a; Supplementary Data 1). Considering all size fractions together, the weighted-average C:N ratios (mol:mol; Eq. 1, Methods) averaged 8.1 ± 0.4 (mean ± 1σ) within the upper 60 m, carbon-rich relative to the canonical Redfield ratio of 6.6 (Fig. 2a). In the lower euphotic zone (80–140 m), weighted average C:N ratios were 6.1 ± 0.2 (Fig. 2a). In comparison, total (non-size fractionated) POM from the BATS data set (July-August 1988-2022 average, https://bats.bios.asu.edu/bats-data/) shows mean C:N ratios matching those described here: ~8 in the upper 60 m and ~6 within the lower euphotic zone (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, the magnitude of vertical variation and the general pattern in the weighted average C:N of our particle size fractions were consistent with other measurements of total POM at the BATS site. Similar trends have been observed across the western North Atlantic, with median C:N ratios of ~7 in the upper 50 m and decreasing to ~6 around the base of the euphotic zone14.

Samples were analyzed after acidification for the bulk organic carbon measurement and without acidification for the bulk nitrogen measurement. Error bars represent the standard deviation and encompass analytical uncertainty as well as uncertainty associated with splitting the filters by weight. In a the solid black line is the weighted average C:N ratio of all three size fractions calculated from the moving averages seen in b–d (solid black lines) and the fraction of total PN in each size fraction. The solid gray lines are median C:N ratios and almost entirely overlap with the mean values. The mean C:N ratios and the fraction of total PN for each size fraction are reported in Supplementary Fig. 3.

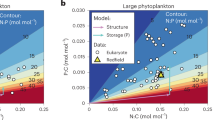

Within each size fraction of POM, C:N ratios were significantly higher at depths where nitrate was below the limit of detection compared to depths where nitrate concentrations were detectable (Fig. 3b, Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.001), suggesting that high C:N ratios in the upper euphotic zone may be a biological response to low nutrient conditions. In the upper euphotic zone, the C:N ratios of total POM averaged 8.1, but our size-fractionated data revealed much higher C:N ratios of ~10-16 in large particles (Fig. 2d) and 5-11 in small (0.3–1.2 and 1.2–6 μm) particles at these depths (Fig. 2b, c). The observed higher C:N ratios of large particles in comparison to small particles in the upper euphotic zone may result from more severe effects of nutrient limitation on larger phytoplankton with relatively low surface area to volume ratios37. Indeed, a previous modeling study38 found C:N ratios of ~13 for large phytoplankton (diatoms) and ~11 for small phytoplankton (picoplankton) in the upper 80 m at the BATS site, and low, convergent C:N (≤5) of both phytoplankton groups between 80–120 m, consistent with our large and small POM fractions presented here (Figs. 2, 3a). However, in our data, the C:N of large particles increases below this depth and diverges from that of small particles, similar to previous work showing elevated C:N ratios below the euphotic zone compared to the surface10,11,12. Overall, these results suggest that variations in C:N ratios across environmental gradients and particle size may be caused by both variations in phytoplankton community composition and taxon-specific acclimation to nutrient stress33.

C:N (mol:mol) ratios of particle size fractions (x-axis labels, in μm) are grouped by (a) depth range (upper or lower euphotic zone) and (b) nitrate concentration at the sampling depth (detectable or undetectable). Red lines represent medians, boxes represent the interquartile range, and brackets represent the range of data, with outliers represented by red crosses for each category. In panel a, the upper euphotic zone is defined as 0–80 m, and the lower euphotic zone is defined as 80-160 m. Differences in C:N between the upper and lower euphotic zones are statistically significant for all size fractions (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.001). In panel b, samples were divided into depths where nitrate + nitrite concentrations were undetectable (<0.2 μmol kg−1) and depths where nitrate + nitrite concentration were detectable (≥0.2 μmol kg−1). Differences in the C:N ratios between these depth divisions are statistically significant for all size fractions (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.001).

Elevated C:N ratios of large particles (>20 μm) within the upper euphotic zone may result from two factors: elevated C:N ratios within large phytoplankton cells or the accumulation of C-rich extracellular material, such as transparent exopolymeric particles (TEP), within this size fraction (or a combination of both). Notably, the C:N ratios of phytoplankton cells are generally elevated relative to the Redfield ratio under nutrient-deficient conditions33. However, previous work suggests that living phytoplankton only comprise an estimated ~30% of POC in the stratified euphotic zone at the BATS site4,39, and thus POM from sources other than phytoplankton may also modulate C:N ratios. Aggregates formed from TEP typically have high C:N ratios (>20)40 due to high carbohydrate content41,42, and thus may contribute to the high C:N ratios of large particles observed here (Fig. 2d). Further, the conditions present within the low-nutrient upper euphotic zone at this site—including high irradiance, oxidative stress, and nutrient limitation—may encourage TEP formation43. Other non-phytoplankton sources of POM include living and dead bacterial cells, fecal pellets, and detrital material. Fecal pellets can have widely variable C:N ratios (i.e., 4–11) depending on the species44, and the C:N ratio of bacterial biomass varies from ~5 under nutrient-replete conditions to up to ~12 under low-nutrient conditions45. Thus, the vertical variations we observe are likely a product of both variable phytoplankton production over depth and variations in contributions from these other sources.

Carbohydrate and amino acid content as the driver of C:N ratios in POM

We measured the abundances of carbohydrates and amino acids in POM collected during cruises in August and November 2021 (Supplementary Data 2 and 3). Carbohydrates have very high C:N ratios (e.g., average of 610 across all samples based on the monomers characterized here), as the dominant carbohydrate monomers in phytoplankton contain no nitrogen46. In contrast, amino acids in our samples had an average C:N ratio of 4.3. Consequently, variations in the relative contributions of these biochemical classes to POM have the potential to modulate C:N ratios. Considering the carbon contribution from each biochemical class, we found that amino acid carbon comprised 12–46% of POC in all size fractions throughout the euphotic zone (Fig. 4b, f; Methods), similar to a previous study in this region27. Carbohydrate carbon comprised 3–18% of POC (with one outlier at 47%) within the upper euphotic zone and <1–10% of POC within the lower euphotic zone in all size fractions (Fig. 4c, g).

Data are shown from two cruises in August 2021 (a–d) and November 2021 (e–h). Amino acid and carbohydrate concentrations were calculated as the sum of the individual monomers quantified. Error bars for C:N ratios represent the standard deviation and include analytical error and uncertainty associated with splitting filters by weight. Error bars for amino acids, carbohydrates, and carbo:AA ratios represent the standard deviation of replicate analyses. One sample (~50 m, large particle, August 2021) is an outlier (identified using MATLAB function ‘isoutlier’) in terms of its carbohydrate content (%POC) and carbo:AA ratio and is plotted on a broken axis because of this (c, d). Error for the carbo: AA ratio of the outlier is ±0.55 molC/molC (not shown).

We found that the contributions of carbohydrates and amino acids to POM varied systematically across our samples, both over depth and across particle size fractions. Notably, large particles (>20 μm), which may be likely to directly sink out of the euphotic zone and fuel mesopelagic communities, contained relatively N-poor, carbohydrate-rich material. Carbohydrate content (as %POC) of the >20 μm particles was higher than that of 0.3–1.2 μm (Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.08) and 1.2–6 μm (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.01) particles throughout the entirety of the euphotic zone (Fig. 4c, g), while amino acid content as a proportion of POC was higher in both small particle size fractions than in large particles at all depths (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.0001). These data provide further evidence that low inorganic nitrogen availability may shape POM composition. Carbohydrate content was significantly higher in the low-nutrient upper euphotic zone than in the higher-nutrient lower euphotic zone (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.05), potentially due to the low nitrogen requirements of carbohydrate biosynthesis. Further, amino acid yields as a proportion of POC were the highest around the top of the nitracline (~80 m in November 2021, ~100 m in August 2021) in all size fractions (Fig. 4b, f).

We found that carbohydrates and amino acids together comprised 16–60% of total POC within the euphotic zone, consistent with previous observations of surface ocean POM and plankton at the BATS site27 as well as cultured phytoplankton33. We did not quantify lipids due to their reduced lability relative to carbohydrates and amino acids5 and their low expected contribution (<15% of POC) in the Sargasso Sea during stratified conditions47. Although a sizable portion of POC in our samples remains uncharacterized via the HPLC methods we used here, the variations that we found in carbohydrate and amino acid abundances explained most of the observed variation in overall C:N ratios. We observed that C:N ratios were significantly positively correlated with carbohydrate content and negatively correlated with amino acid content, with carbohydrates and amino acids explaining 60% and 35% of variation in C:N ratios, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Together, the ratio of carbohydrate:amino acid (carbo:AA, on a mol carbon basis; Fig. 4d, h) explained 67% of the variation in C:N ratios of particles, i.e., higher carbo:AA ratios were found in particles with higher C:N ratios (Fig. 5). We also computed the average C:N ratio of the summed carbohydrates and amino acid monomers that we characterized, weighted by the seawater concentration of each compound; this molecular average C:N ratio also is strongly linearly correlated with bulk C:N (Supplementary Fig. 5c). The slope of the relationship suggests that the portion of the POM pool that we did not characterize molecularly has a relatively high C:N ratio, potentially pointing to incomplete characterization of the carbohydrate pool with the methods used here48 as well as contributions from lipids and other high C:N organic compounds. In all comparisons, one sample (August 2021, >20 μm, ~50 m) had anomalously high carbohydrate content (%POC) and carbo:AA ratio and was identified as an outlier within these data (Methods; Fig. 4c, d; Supplementary Fig. 6). The outlier is consistent with the depth trends in both variables and with our interpretations of this data (Fig. 4c, d; Supplementary Fig. 6) but was omitted from further statistical analyses.

Data are from size-fractionated particles within the euphotic zone at the BATS site in August and November 2021. Orthogonal regression was fit using the MATLAB function linortfit2. One outlier was omitted, with a carbo:AA ratio of ~3.6 and a C:N ratio of ~14. The same figure, including the outlier, can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 6. Horizontal error bars represent standard deviations of replicates, while vertical error bars represent the standard deviation and include uncertainty from blank corrections and filter splitting by weight.

Glucose-rich carbohydrates drive high C:N of POM in the low-nutrient upper euphotic zone

Our characterization of individual carbohydrate monomers and amino acids offers additional information on the sources and degradation of POM. Our methods included an initial hydrolysis step and thus captured the total carbohydrate monomers deriving from all carbohydrate structures within POM (monomers, oligomers, and polymers). Neutral sugars dominated the particulate carbohydrate pool throughout the euphotic zone in both small and large particles, comprising, on average, 91% (range 80–99%) of total particulate carbohydrates on a molar basis (Supplementary Figs. 7, 8), similar to previous results from surface POM at the BATS site (≥90%)27. Glucose, galactose, and mannose+xylose (quantified together) were the dominant neutral sugars present, also similar to other studies of marine POM27,29,30, although ribose and fucose occasionally formed sizable portions of the carbohydrate pool (up to 14% and 8%, respectively; Supplementary Figs. 7-8).

Large particles within the upper euphotic zone, which were characterized by distinctly high C:N ratios and total carbohydrate content, also had significantly higher relative contributions of glucose (43–90% of total carbohydrate) than both small particles at the same depths (Kruskal-Wallis p = 6.9 × 10−8) and large particles deeper in the euphotic zone (Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.0084; Fig. 6; Supplementary Figs. 7, 8). Glucose is a major constituent of common algal polymers, such as chrysolaminarin, laminarin, cellulose, hemicellulose, and glycogen49,50,51, and it dominates the cellular carbohydrates of cultured phytoplankton52,53,54. We thus suggest that elevated glucose contributions to large particles, and, to a lesser extent, small particles, in the upper euphotic zone reflect photoautotrophic carbohydrate production. For instance, the colonial cyanobacterium Trichodesmium spp. was occasionally visible in our large particle fraction, and glucose comprised 70–90% of carbohydrates within Trichodesmium spp. colonies isolated from net tows (Methods; Supplementary Fig. 9). Additionally, many cultured phytoplankton produce greater amounts of carbohydrates, particularly glucose-rich ones, as storage or reserve molecules55,56 under nutrient-deficient conditions49,55,56,57,58. However, small eukaryotic phytoplankton may be limited in their ability to accumulate storage carbohydrates and may favor the accumulation of lipids instead59. Though glucose dominated the carbohydrate pool of most samples in the upper euphotic zone, we observed small but significant differences in carbohydrate monomer composition between the two cruises (PERMANOVA p < 0.001), with galactose dominating small particles in the upper euphotic zone during August 2021 (Supplementary Figs. 7-8). These differences in carbohydrate monomer composition may derive from different storage and structural polymers within different phytoplankton taxa and/or differences in growth phase52,54,60, or contributions from non-phytoplankton sources.

Shapes denote the different particle size fractions (in μm), and colors denote the sample depth. The vector length reflects the importance of the relative abundance of a particular monomer in determining the dimensional separation between samples along the direction of the vector. The proportion of variance in the dataset encompassed by each axis is noted in the axis labels. Ellipses reflect the 95% confidence intervals for each size fraction. Fuc fucose; Rha rhamnose, GalN galactosamine, Ara arabinose, GlcN glucosamine, Gal galactose, Glc glucose, ManXyl mannose/xylose, Rib ribose, MurAc muramic acid, GalURA galacturonic acid, GlcURA glucuronic acid.

Interestingly, POM collected at depths around 50 m routinely had the maximal carbo:AA ratios (Fig. 4d, h) and C:N ratios (Fig. 4a, e). This depth is also characterized by maxima in POC concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 2), bacterial abundances61, phytoplankton biomass4, and gross primary production62, further suggesting that high carbohydrate content may result from phytoplankton production. In contrast to the near-surface where high irradiance might inhibit carbohydrate production63,64, the 50 m depth is characterized by moderate irradiance. Coupled with relatively high primary production62 and low-nutrient conditions (Fig. 1), this may result in greater photoautotrophic biosynthesis of carbohydrates rather than N-rich proteins at this depth. Alternatively, the high-light, low-nutrient conditions of near-surface depths may induce elevated extracellular release of photosynthate65—primarily as polysaccharide41,42—to the dissolved organic matter (DOM) pool by phytoplankton, resulting in relatively lower carbohydrate yields in POM. This idea may be supported by elevated contributions of dissolved combined neutral sugars to DOM in the surface compared to deeper in the euphotic zone at the BATS site66.

Productive and degradative controls on biochemical content of POM in the lower euphotic zone

In contrast to the upper euphotic zone, particulate carbohydrates in all size fractions within the lower euphotic zone contained lower relative contributions from glucose and higher relative contributions from most other monomers (Fig. 6, Supplementary Figs. 7, 8). Similarly, a recent study in the Fram Strait found that particles above the deep chlorophyll maximum were enriched in glucose relative to particles below the deep chlorophyll maximum and nitracline36. We hypothesize that phytoplankton production of carbohydrates, specifically glucose-rich polymers, is diminished in the lower euphotic zone due to higher nutrient concentrations and lower light intensities67. An early model of phytoplankton physiology suggests that carbohydrates accumulate when nutrients, especially nitrogen, are in short supply, resulting in high carbohydrate to cellular carbon ratios68. However, when the cell has obtained the necessary nutrients to synthesize other compounds, the carbohydrate content of a cell is predicted to decrease68. Thus, lower particulate carbohydrate content indicates greater photoautotrophic synthesis of more nitrogen-rich compounds (e.g., amino acids; Fig. 4b, f) under the low-light, higher-nutrient conditions of the lower euphotic zone. Consistent with this model, we observe greater relative contributions from the particularly N-rich amino acids, histidine (C:N = 2) and arginine (C:N = 1.5; Supplementary Figs. 10, 11), and N-containing carbohydrate monomers, glucosamine and galactosamine (Supplementary Figs. 7,8), within the lower euphotic zone.

We also observed small differences in the carbohydrate monomer composition of large vs. small particles throughout the euphotic zone, reflecting the diverse and variable phytoplankton producing carbohydrates within these size fractions61. Compared to small particles, large particles contained elevated concentrations of fucose and glucuronic acid as a proportion of POC (Supplementary Fig. 12), which may derive from cell-wall polysaccharides in diatoms or TEP-rich aggregates69,70. Previous work measuring phytoplankton pigments at the BATS site demonstrated that diatoms are most abundant within the lower euphotic zone61, consistent with the greater relative concentrations of fucose and glucuronic acid within the lower euphotic zone presented here (Fig. 6, Supplementary Figs. 7,8). Large particles throughout the euphotic zone also contained greater contributions from glucosamine and galactosamine than small particles (Supplementary Fig. 12)—possibly due to contributions of chitin and other polymers from zooplankton waste and/or diatoms71,72. In contrast, small particles contained greater contributions from arabinose, likely reflecting the differences in the structural carbohydrate composition of small and large phytoplankton53,56.

Diagenetic alteration of organic matter was also evident over depth, imprinted on top of biochemical variability likely arising from phytoplankton production. Carbohydrate yields within the lower euphotic zone (average 3% POC, range 0.6–10% POC) were lower than what would be expected from fresh phytoplankton biomass (11–51% of POC, estimated from cultures53,54 using a conservative conversion factor of POC = 45% dry weight46), indicating degradation of the particulate carbohydrate pool. Compared to particles in the upper euphotic zone, those in the lower euphotic zone contained elevated relative concentrations of muramic acid (Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.016) and glucosamine (Kruskal-Wallis p = 2.5e-06; Supplementary Figs. 7-8), both constituents of the bacterial polymer peptidoglycan, which derives from both heterotrophic bacteria and cyanobacteria72. The lower euphotic zone was also characterized by elevated relative concentrations of the non-protein forming amino acids β-alanine (Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.15) and γ-aminobutyric acid (Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.19), relative to the upper euphotic zone (Supplementary Figs. 10,11), indicating degradation of protein-forming amino acids. Lastly, the decrease in the relative concentration of glucose with depth may partially result from the preferential solubilization and/or utilization of glucose-rich storage polysaccharides by heterotrophic bacterial communities73,74,75,76, as these molecules are more labile than structural polysaccharides55,60,73 that contain greater proportions of other monomers, such as mannose, xylose, galactose, arabinose, rhamnose, and fucose29,69,73,77. Interestingly, the distribution of carbohydrates within DOM can show opposite trends66—e.g., increasing glucose-containing polymers with depth—to those we observed here in POM. This may be due to differences in the relative lability of the polymeric structures within the POM and DOM pools78 or solubilization of glucose-rich polymers in POM contributing to the DOM pool.

Implications of variable POM composition for global biogeochemistry

Previous work has demonstrated variations in the stoichiometry of both phytoplankton and total POM within the global surface ocean. However, to date, there has been little explicit exploration of these patterns across the varying nutrient and light conditions found over depth within the euphotic zone. Similar to open-ocean data from global compilations of surface ocean POM9, our data show that C:N ratios of total POM are higher than the Redfield ratio within the low-nitrate, high-light upper euphotic zone of the subtropical gyres. Yet, we observe that C:N ratios of total POM are less than or equal to the Redfield ratio within the higher-nitrate, low-light lower euphotic zone. These observations are consistent with a recent study that modeled cellular C and N quotas for different biochemical classes as controlled by nitrate concentrations and light availability24.

Many models continue to use fixed (Redfield) stoichiometric ratios of phytoplankton and/or POM16,17,18,19, but this approach may underestimate primary productivity under low-nutrient conditions. We estimated the C:N ratio of particulate primary production at the BATS site by integrating our C:N measurements across the euphotic zone, weighted by the relative rates of net primary production (NPP) at different depths (Eq. 2, Methods). This resulted in a C:N ratio of 7.7 for integrated particulate primary production—considerably higher than the canonical Redfield ratio of 6.6. Assuming a fixed stoichiometry would therefore underestimate NPP within stratified, open-ocean environments like the BATS site by ~17%. These findings align with recent studies indicating that the variable C:N:P ratios of phytoplankton-derived POM may partially compensate for the predicted declines in NPP and carbon export associated with increased stratification in a warming ocean20,21,22. However, there has been little discussion of stoichiometric variation over depth within these studies.

Notably, the vertical variations in the chemical composition of POM within the euphotic zone we observe here may be obscured or weakened during times of deep convective mixing at this site and in other seasonally oligotrophic environments. Data from the BATS program demonstrates that there is less vertical variation in C:N ratios of total POM during February-March (deep mixing/spring bloom) compared to the stratified conditions observed here, with C:N ratios in the upper euphotic zone of <7 compared to ~8 during stratified conditions, and similar C:N ratios in the lower euphotic zone in both seasons, ~6 (Supplementary Fig. 438). Thus, fixed stoichiometric ratios may be more representative of this site and others like it during deep convective mixing and spring bloom periods than during thermally stratified periods. Overall, our data highlight the importance of not only including variable stoichiometry in models but also validating these models with high-resolution data where possible.

Additionally, our collection of size-fractionated particles elucidates a previously unidentified feature of POM at the BATS site: large particles within the upper euphotic zone have C:N ratios much higher (C:N 10–16) than both the Redfield ratio (C:N 6.6) and the mean C:N ratio of total POM at these depths (C:N 8.1). We also observed elevated, glucose-rich carbohydrate content within all size fractions of particles in the upper euphotic zone, especially large particles, likely due to accumulation of carbohydrates by phytoplankton under low nitrate concentrations. The composition of this material indicates uptake of inorganic C and N by primary producers in non-Redfield C:N ratios within this depth range (surface to ~80 m).

The POM with the highest C:N ratios and carbohydrate content was found in our largest size fraction, which is most likely to directly sink out of the euphotic zone and fuel mesopelagic carbon demand. Bacterial carbon demand in the mesopelagic ocean is higher than measured particulate and dissolved carbon export61,79,80, leading to an imbalance in the carbon budget at the BATS site. Previous work suggests that these budgets may be remedied by the export of gel-like organic matter with very high C:N ratios at this site81, which could originate from material like the large particles we characterized in the upper euphotic zone. We did not observe evidence of these particles contributing substantially to POM in the lower euphotic zone, and the export during this time period is usually low61; however, we did not characterize sinking/exported POM directly in this work. Thus, it is possible that the carbohydrate-rich material sinks very quickly and is not adequately represented in our in situ pump-collected samples from the lower euphotic zone. In data from BATS sediment traps, exported material during our sampling months has a median C:N ratio of 8.1 (July-August, 1988–2023; https://bats.bios.asu.edu/bats-data/), suggesting that N-poor, carbohydrate-rich material from the upper euphotic zone may contribute to export under these conditions.

The variable stoichiometry and biochemical content of POM we observed here also should affect the mechanisms and net biogeochemical outputs of remineralization. Remineralization of POM with low N content provides less fuel for nitrate regeneration via nitrification and may require heterotrophic bacteria to assimilate inorganic nutrients, as observed during the summertime in the lower euphotic zone and upper mesopelagic at the BATS site81. Further, a recent study demonstrated that the potential respiratory quotient—or the ratio of oxygen uptake to carbon respiration—of POM varies with depth both within and below the euphotic zone14, likely due to variation in phytoplankton community structure and relative abundances of different biomolecules. Additionally, the biochemical composition of POM defines the specific metabolic capabilities required for its breakdown, uptake, and remineralization25 and therefore, which microbes may interact with the material. Thus, future work should examine the genes encoding for and the expression of carbohydrate-active enzymes and proteases in microbial communities within and below the euphotic zone, especially within the context of variable composition of organic substrates.

Conclusions

We present a unique data set exploring the elemental and biochemical composition of three size fractions of particles within a stratified euphotic zone. We find weighted average C:N ratios of POM of 8.1 in the upper euphotic zone and 6.1 in the lower euphotic zone, demonstrating considerable variability around the canonical Redfield ratio of 6.6. However, our size fractionation additionally revealed that a subset of particles, those >20 μm in size, regularly contribute material with very high C:N ratios ( ~ 10–16) within the high-light, low-nitrate upper euphotic zone. Though the contributions of both amino acids and carbohydrates to POC vary over depth, carbohydrate contributions to POC appear to primarily drive the patterns we observe in C:N ratios, with decreasing carbohydrate content from the upper to the lower euphotic zone. Overall, these data highlight significant and systematic variations in elemental and biochemical composition over depth within a thermally stratified euphotic zone, likely indicating strong photosynthetic response to varying nutrient conditions across all size fractions. However, contributions from heterotrophic biomass, zooplankton fecal pellets, and/or degraded POM are substantial26 and thus could also be important in modulating C:N ratios here.

Recent work has indicated a need to incorporate variable stoichiometry of phytoplankton and POM into global biogeochemical models20,21, mainly in response to known stoichiometric variability within the surface ocean9. Our data demonstrate that vertical variability in C:N ratios of POM is also prevalent under stratified, oligotrophic conditions, further supporting the need to include variable stoichiometry in global models. Further, the N-poor, carbohydrate-rich large particles identified within the upper euphotic zone here may contribute disproportionately to export, and remineralization of this material has different biogeochemical outcomes (i.e., inorganic nitrogen yields, oxygen utilization) than remineralization of material with Redfield C:N stoichiometry. Lastly, variation in the biochemical composition of POM within the euphotic zone indicates that a diverse suite of metabolic capabilities is required to break down this material. Future work linking the biochemical composition of organic substrates to the metagenomes, metatranscriptomes, and/or metaproteomes of microbial communities over depth would advance our understanding of how microbes respond to and shape the composition of organic matter.

Methods

Study area and environmental conditions

Samples were collected during July 2018, July 2019, August 2021, November 2021, July 2022, and July 2023 at or near the BATS site (31°40’ N, 64°10’ W) or at Hydrostation S (32°10’ N, 64°30’ W; Supplementary Table 1). Total water depth is ~4600 m at BATS and ~3300 m at Hydrostation S, with seasonal variation in mixed layer depths ranging from <20 m in the summertime and as deep as 400 m in the winter/spring61,82. The mixed layer depth during the study periods was determined as the depth where the potential density (σT) of the water was equal to sea surface σT plus an increment in σT equivalent to 0.2 times the thermal expansion coefficient83.

Seawater nitrate+nitrite concentrations

Nitrate+nitrite (NO3- + NO2-) concentrations were measured for samples collected during each sampling period. For simplicity, “nitrate” is used to represent nitrate+nitrite throughout the text. Seawater samples were collected directly from the Niskin into 20 mL HDPE vials, stored and transported at −20 °C, and analyzed using flow injection analysis on a QuickChem 8000 (Lachat Instruments, Zellweger Analytics, Inc.) at the Marine Science Institute Analytical Laboratory at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The limit of detection was 0.2 μmol kg−1; thus, nitrate concentrations reported below 0.2 μmol kg−1 are statistically indistinguishable from blanks.

Seawater nitrate concentrations were estimated at each specific depth of collected particle samples. Raw nitrate data were binned by depth (6 m bin) at discrete target depths aligned with in situ pump collections throughout the cruises to compile a single, representative profile for each cruise. The composite profile was used to interpolate measured concentrations to the depths of particle collections. An average concentration was calculated from the concentrations within each depth bin. The compiled profile was interpolated to the depths of particle samples using the MATLAB function interp1 with default settings, and interpolated concentrations were classified as either undetectable (<0.2 μmol kg-1) or detectable (≥0.2 μmol kg−1) for comparison with C:N data.

Collection of size-fractionated particles via in situ pumps

Size-fractionated particles were sampled via McLane WTS-LV in situ pumps (4 L min−1 maximum pumping rate; McLane Research Laboratories, Inc.) during all sampling periods. Five to eight depths were sampled within the upper 200 m during each cruise. Most pumps were dual-flow and collected water through two separate filter holders simultaneously for geochemical and taxonomic analyses, with size fractions coordinated across the sampling collaboration to roughly separate size classes of free-living and particle-attached microbes as well as different size classes of detritus, as described by Henderson et al4. and Comstock et al26. Each filter holder was a vertical-intake (McLane) or mini-MULVFS84 style comprised of four 142 mm diameter filter tiers containing the following filters (from top to bottom) for the geochemical analyses reported here: [1] 20 μm Nitex filter, [2] 6 μm Nitex filter (with the exception of AE2213 and AE2315, 5 μm polyester filter), [3] two stacked 1.2 μm glass fiber filters (GF/C), [4] two stacked 0.3 μm glass fiber filters (GF75). The first three tiers were equipped with a 150 μm Nitex filter beneath the filter(s) of interest to assure filter structural integrity4. All filters were cleaned before use and processed/stored after pump recovery as described by Henderson et al4. Flow meters were placed in-line on each flow path of the pumps, and exact filtered volumes for each flow path were determined; flow rates through filter stacks used for organic analyses averaged <3 L min-1. We collected dip blanks—filters that did not have any water pumped through them, but were submerged in natural seawater—along with our samples.

Processing of large particle (>20 µm) samples

Samples were stored at −80 °C until processing. Once in the lab, particles collected on 20 µm Nitex filters were rinsed off the filters onto 47 mm diameter, pre-combusted (450 °C, for 5 h) glass fiber filters with a nominal pore size of 0.7 μm (GF/F) using combusted glass filter towers and 0.2 µm-filtered seawater obtained from low-nutrient surface waters of Biscayne Bay7. Briefly, particles were rinsed from the Nitex filters using an acid-clean squirt bottle to spray across the filter. The Nitex filter was then sonicated for three minutes in an acid-clean polypropylene Nalgene bottle with more filtered seawater. After sonication, this water was poured into the filter tower. The process was repeated three times, with all filtered seawater being drained from the filter tower with gentle vacuum after each rinse and sonication onto the same GF/F filter7. Samples were then freeze-dried and inspected under a dissecting microscope to visually characterize the particles and remove intact zooplankton swimmers or contaminant fibers, which were both rare in the samples.

Concentrations of bulk POC and PN

Glass fiber filters of both pore sizes (0.3 and 1.2 μm) and 47 mm GF/F filters containing the washed-down particles from the Nitex size fraction were quantitatively split radially while frozen, and portions were freeze-dried. Freeze-dried filters were quantitatively split radially by weight for separate elemental analyses for POC (after acidification) and for PN (without acidification) for samples collected during all six cruises. For acidified filter splits, carbonates were removed via dropwise addition of concentrated sulfurous acid directly to the filters, which were then dried overnight at 60 °C4. Bulk POC and PN concentrations and isotopic compositions were analyzed using a Thermo Scientific Flash elemental analyzer coupled to a MAT 253 Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS) via a Conflo IV interface. The EA oxidation and reduction reactors were held at 980 °C and 650 °C, respectively, and the gas chromatography column was held at 65 °C. Acetanilide and glycine standards (Schimmelmann Lab, Indiana University) of known mass (range 5–600 μg) were analyzed alongside samples to calculate sample concentrations. Dip blanks were analyzed alongside samples, and the POC and PN concentrations measured for these blanks were subtracted from those of samples on a filter area basis, as determined by weight7. Data from the 0.3–1.2 µm, 1.2–6 μm and >20 µm size fractions are reported here because the 6–20 μm size fraction did not contain enough material to obtain reliable measurements.

POC/PN (C:N) ratios were calculated from acidified measurements of POC and nonacidified measurements of PN for each size fraction. All C:N ratios throughout this manuscript are reported on a molar basis (mol C/mol N). To compare the composition of total POM between the upper and lower euphotic zones, we calculated a concentration-weighted average C:N ratio across the three size fractions of particles using Eq. 1:

where the subscripts indicate the individual size fractions (in μm) and f indicates the proportion of total material contained in that size fraction, as calculated from PN concentrations. Mathematically, this is identical to the ratio of the absolute C and N concentrations, summed across size classes. C:N ratios for each individual size fraction were averaged across all cruises using the moving mean across 15 m depth bins (with a minimum number of two observations within each bin to reduce variability associated with single data points; result shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a); these averages, along with the fraction of PN contained in each size fraction (Supplementary Fig. 3b), were used to calculate the weighted average C:N of total POM (sum of all size fractions; Supplementary Fig. 3c, Fig. 2a). The proportion of total PN in each size fraction was calculated for each individual sample set (i.e., a single pump that collected the three analyzed size fractions from the same time and depth). Partitioning of PN among filter size fractions was only calculated for sample sets that were complete (i.e., all three size fractions were analyzed), all others were omitted. Proportions of PN in each size fraction were depth-resolved (Supplementary Fig. 3b); similar to the C:N averages for individual size fractions, a moving mean with 15 m depth binning was used to calculate average proportion of PN in each size fraction. Averages were only calculated when two or more data points fell within the bin in the upper 130 m; this requirement was reduced to one data point per bin below 130 m where data were more limited. The C:N ratios of total POM integrated over the whole euphotic zone were calculated using the weighted average C:N ratio discussed above (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and mean total PN concentrations at each depth (sum of three size fractions; Supplementary Fig. 2).

A NPP-weighted average C:N ratio was calculated using the depth-resolved total POM C:N ratio (calculated as described above) and NPP data from the BATS program as in Eq. 2:

where z is depth, and C:Nz and NPPz are the C:N ratio and NPP (in mgC m−3 d−1) interpolated at one meter intervals from 1 to 160 m. NPP data from the BATS program (July-August 2016–2023 average), was accessed via https://bats.bios.asu.edu/bats-data/.

All C:N ratios reported here were calculated from POC concentrations measured after acidification (to remove carbonates) and PN concentrations measured without acidification. This method requires separate pieces of filter to measure POC and PN concentrations, which increases uncertainty due to error associated with splitting filters by weight; error bars on figures visualizing this data incorporate this uncertainty. However, the systematic patterns we observed in C:N ratios were similar when calculated from POC and PN measured simultaneously on the acidified filter split (Supplementary Fig. 13), a method that is not subject to uncertainties from filter splitting but is nonetheless not preferred due to potential adverse effects of acidification on nitrogenous compounds, especially if isotopic analysis is also an objective85. Specifically, in the acidified POC:PN data, differences between large (>20 μm) and small (0.3-1.2 μm and 1.2–6 μm) particles throughout the euphotic zone were still statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.0001), and differences within size fractions between the upper and lower euphotic zones were also still significant (Kruskal-Wallis p < 0.01).

Analysis of individual carbohydrate and amino acid monomers

Freeze-dried filters (0.3 and 1.2 µm filters and 47-mm GF/F filters containing particles from the >20 µm size fraction) were also quantitatively split radially by weight for analysis of carbohydrate and amino acid content for selected samples from August and November 2021. Analyses for both carbohydrate and amino acid content measure individual monomers derived from all hydrolysable carbohydrate- and amino acid-containing polymers due to hydrolysis before analysis.

For carbohydrate monomer analysis, two or three filter splits (replicates/triplicates) were prepared per sample. Filter splits were hydrolyzed (20 h, 100 °C) using 0.4 N hydrochloric acid36, and hydrolysate was separated from filter material by pushing through combusted glass syringes with combusted glass wool in the tip and 0.2 μm polyethersulfone syringe-tip filters. Samples were neutralized by evaporating acid under N2, reconstituted in ultrapure water, and filtered again through combusted quartz wool to remove any residual particulates before quantitative aliquots (by volume) were taken for analysis. Frozen samples were transported to the University of California Santa Barbara for analysis via high-performance anion exchange chromatography coupled with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD)86. Here, we quantified neutral, amino, and acidic carbohydrate monomers following Engel and Händel86. The mobile phase was as follows: eluent A was 100 mmol L−1 sodium hydroxide and 200 mmol L−1 sodium acetate, eluent B was 18 mmol L−1 sodium hydroxide, eluent C was 1000 mmol L−1 sodium hydroxide, and eluent D was ultrapure water. Eluent A was filtered through a 0.2 μm nylon membrane filter, and subsequently all eluents were bubbled with N2 gas for 45 min and degassed before being attached to the system and pressurized with N2 gas. Individual carbohydrates were separated on a Dionex CarboPac PA10 analytical column (4 × 250 mm) with a Dionex CarboPac PA10 guard column (4 × 50 mm). The column, detector, and autosampler were temperature controlled, held constant at 25 °C, 30 °C, and 4 °C, respectively. The flow rate was 1 mL min−1, and the elution gradient was as follows:

−15 to 22 min: 100% eluent B

23 min: 9:1 eluent D/C

27–37 min: 100% eluent A

42–57 min: 4:1 eluent D/C

60 min: 100% eluent B

A standard curve was analyzed alongside samples during each run. A stock solution was prepared in ultrapure water to achieve concentrations of 1 mmol L−1 fucose, rhamnose, arabinose, galactose, glucose, mannose/xylose, ribose, galacturonic acid, and glucuronic acid, and 0.5 mmol L−1 galactosamine, glucosamine, and muramic acid. The solution was prepared all at once, and then aliquoted and stored at –20 °C until analysis. Standard aliquots were thawed alongside samples and diluted to concentrations of 10 to 10000 nmol L−1 per monomer for analysis. Standards of appropriate sizes (i.e., bracketing those of each monomer sample peak) were used to determine sample concentrations. To verify consistent instrument performance, a 1000 nmol L−1 standard was analyzed after every eight samples and compared to the original standard curve66. An aliquot of a sample with ample material was also analyzed during every day of analysis to confirm day-to-day consistency. Sample concentrations were calculated from recorded peak areas using the calibration from the standard curve. Blanks of ultrapure water and full process blanks were analyzed alongside samples to check for background carbohydrate content in reagents or contamination. Full process blanks consisted of dip blank filter splits and 0.4 M hydrochloric acid blanks that were processed exactly as samples. Seawater particulate carbohydrate concentrations (nmol L−1) were calculated based on the original amount of seawater filtered through the portion of sample analyzed during each run (material extracted from 0.1 to 2.5 L of seawater injected for a single run). We report concentrations here as (1) total carbohydrate carbon as a proportion of POC, where carbon from individual monomers was calculated from the molecular formula for each monomer, summed, and divided by the total POC concentration in that particle size fraction, and (2) individual monomers as mol%, where the concentrations (in nmol L−1) of individual monomers were each divided by the total carbohydrate concentration for that sample (sum of individual monomer concentrations in nmol L−1).

For amino acid analysis, one filter split was prepared per sample, and three aliquots from the final prepared solution were analyzed (triplicate injections). Filter splits were hydrolyzed (20 h, 110 °C) using trace metal grade 6 N hydrochloric acid. Hydrolysate was separated from filter material using combusted glass syringes with glass wool in the tip and syringe-tip 0.2 μm polyethersulfone filters. Samples were neutralized by evaporating acid under N2, reconstituted in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid, and purified via cation exchange chromatography7,44,87. Notably, we found that cation exchange chromatography was crucial in achieving acceptable yields; trial samples analyzed without undergoing this purification step resulted in yields much lower than expected and much lower than when analyzed after the purification procedure, likely due to chromatographic interference from compound(s) that were effectively removed via the cation exchange procedure. Samples were aliquoted into individual 2 mL HPLC vials, and known quantities of the synthetic amino acid aminoadipic acid were added as an internal standard to confirm accurate analysis. Samples were then dried under N2, reconstituted in 60/40 ultrapure water/methanol (v/v), and derivatized with o-phthaldialdehyde and 2-mercaptoethanol 2 min before injection for analysis via reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1100) with fluorescence detection (Agilent G1321A FLD; excitation 250 nm, emission 410 nm)88,89. The mobile phase was as follows: eluent A was 50 mmol L-1 sodium acetate (HPLC-grade; adjusted to pH 5.7), and eluent B was 100% methanol (HPLC-grade). The stationary phase was a C18 column (KinetexTM EVO-C18, 5 µm, 100 Å, 4.6×250 mm) with a C18 guard column (EVO-C18 ULTRA cartridge, 4.6 mm) at 20 °C. The flow rate was constant at 0.9 mL min−1 and the elution gradient of eluent B added to eluent A was as follows:

−12 min to 0 min: 5% eluent B

4 min: 23% eluent B

8 min: 29% eluent B

24 min: 44% eluent B

37 to 44 min: 60% eluent B

52 min: 77% eluent B

57–62 min: 100% eluent B

A standard curve was analyzed alongside samples during each run. The standard used was a mixed amino acid standard solution initially prepared in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid. We measured the following amino acids: alanine, arginine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, serine, threonine, tyrosine, valine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and β-alanine. The standard also included cysteine and proline, though these amino acids are not detectable with the OPA derivatization method88,89. The standard was prepared from the Pierce amino acid calibration standard H with the addition of non-protein forming amino acids γ-aminobutyric acid and β-alanine. The standard solution was prepared to a concentration of 92 μmol L−1 for all amino acids except for γ-aminobutyric acid and β-alanine, which were prepared to concentrations of 30 and 34 μmol L−1, respectively. The standard solution was aliquoted by weight to exact concentrations targeting a range of 0.2–50 μmol L−1 for the protein-forming amino acids. As with the samples, standards were aliquoted directly into individual 2 mL HPLC vials, supplemented with known quantities of aminoadipic acid as an internal standard, dried under N2, and reconstituted in 60/40 ultrapure water/methanol (v/v). The effect of cation exchange chromatography on measured amino acid yields in the standard was determined by subjecting two aliquots of the standard mixture to the procedure; average yields for each amino acid were 87–98% with the exception of arginine (40%) and lysine (71%). Yields were consistent for each amino acid across the duplicate standard aliquots. Sample concentrations were corrected, assuming a yield of 40% for arginine, 71% for lysine, and 91% (average) for all other amino acids. Sample peak areas were converted to molar quantities using the calibration from the standard curve. Blanks of ultrapure water and full process blanks were analyzed alongside samples to check for any background amino acid content in reagents or contamination. Full process blanks consisted of dip blank filter splits that were processed exactly as sample filter splits. Seawater particulate amino acid concentrations (nmol L−1) were calculated based on the original volume of seawater filtered through the portion of sample analyzed during each run (material extracted from 0.7 to 10.5 L of seawater injected for a single run). We report concentrations here as (1) total amino acid carbon as a proportion of POC, where carbon from individual amino acids was calculated (via the molecular formula for each monomer), summed, and divided by the total POC concentration in that particle size fraction, and (2) individual amino acids as mol%, where the concentrations (in nmol L−1) of individual amino acids were each divided by the total amino acid concentration in that sample (sum of individual concentrations in nmol L-1)90.

Statistical methods

Outliers were identified using the MATLAB function isoutlier. Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed using the built-in MATLAB function kruskalwallis to compare differences between groups and establish statistical significance. The presence and strength of linear relationships were established using orthogonal linear regression with the MATLAB function linortfit291. Principal components analysis was performed in RStudio using the built-in function prcomp. Statistical significance of differences in carbohydrate monomer composition and amino acid composition between groups (i.e., size fraction, season, and depth) was established with PERMANOVA (permutational ANOVA) using the adonis2 function from package vegan in RStudio92,93.

Data availability

All data associated with this manuscript are available on the BIOS-SCOPE BCO-DMO project page (https://www.bco-dmo.org/project/826178). Specifically, the carbohydrate monomer data94 are available at https://doi.org/10.26008/1912/bco-dmo.964801.1, the amino acid data95 are available at https://doi.org/10.26008/1912/bco-dmo.964684.1, and the bulk POM data96 are available at https://doi.org/10.26008/1912/bco-dmo.964826.1.

References

Iversen, M. H. Carbon export in the ocean: a biologist’s perspective. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 357–381 (2023).

Kharbush, J. J. et al. Particulate organic carbon deconstructed: molecular and chemical composition of particulate organic carbon in the ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 518 (2020).

Martiny, A. C., Vrugt, J. A., Primeau, F. W. & Lomas, M. W. Regional variation in the particulate organic carbon to nitrogen ratio in the surface ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 723–731 (2013).

Henderson, L. C., Wittmers, F., Carlson, C. A., Worden, A. Z. & Close, H. G. Variable carbon isotope fractionation of photosynthetic communities over depth in an open-ocean euphotic zone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2304613121 (2024).

Arndt, S. et al. Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: a review and synthesis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 123, 53–86 (2013).

Amaral, V. J. et al. Particle cycling rates at Station P as estimated from the inversion of POC concentration data. Elem. Sci. Anth. 10, 00018 (2022).

Wojtal, P. K. et al. Deconvolving mechanisms of particle flux attenuation using nitrogen isotope analyses of amino acids. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 1965–1981 (2023).

Redfield, A. C. On the proportions of organic derivatives in sea water and their relation to the composition of plankton. James Johnstone Memorial Volume. 176–192 (1934).

Martiny, A. C. et al. Strong latitudinal patterns in the elemental ratios of marine plankton and organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 6, 279–283 (2013).

Lam, P. J. et al. Size-fractionated distributions of suspended particle concentration and major phase composition from the U.S. GEOTRACES Eastern Pacific Zonal Transect (GP16). Mar. Chem. 201, 90–107 (2018).

Gordon, D. C. Distribution of particulate organic carbon and nitrogen at an oceanic station in the central Pacific. Deep Sea Res. 18, 1127–1134 (1971).

Schneider, B., Schlitzer, R., Fischer, G. & Nöthig, E. Depth-dependent elemental compositions of particulate organic matter (POM) in the ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1032 (2003).

Michaels, A., Karl, D. & Capone, D. Element stoichiometry, new production and nitrogen fixation. Oceanog. 14, 68–77 (2001).

Gerace, S. D. et al. Depth variance of organic matter respiration stoichiometry in the subtropical north atlantic and the implications for the global oxygen cycle. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007814 (2023).

Stephens, B. M. et al. Oxidation state of bioavailable dissolved organic matter influences bacterioplankton respiration and growth efficiency. Commun. Biol. 8, 145 (2025).

Dutkiewicz, S. et al. Capturing optically important constituents and properties in a marine biogeochemical and ecosystem model. Biogeosciences 12, 4447–4481 (2015).

Aumont, O., Ethé, C., Tagliabue, A., Bopp, L. & Gehlen, M. PISCES-v2: an ocean biogeochemical model for carbon and ecosystem studies. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 2465–2513 (2015).

Somes, C. J., Schmittner, A., Muglia, J. & Oschlies, A. A three-dimensional model of the marine nitrogen cycle during the last glacial maximum constrained by sedimentary isotopes. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 108 (2017).

Stock, C. A. et al. Ocean biogeochemistry in GFDL’s earth system model 4.1 and its response to increasing atmospheric CO2. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS002043 (2020).

Tanioka, T. & Matsumoto, K. Buffering of ocean export production by flexible elemental stoichiometry of particulate organic matter. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 1528–1542 (2017).

Kwiatkowski, L., Aumont, O., Bopp, L. & Ciais, P. The impact of variable phytoplankton stoichiometry on projections of primary production, food quality, and carbon uptake in the global ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 516–528 (2018).

Martiny, A. C. et al. Marine phytoplankton resilience may moderate oligotrophic ecosystem responses and biogeochemical feedbacks to climate change. Limnol. Oceanogr. 67, S378–S389 (2022).

Letscher, R. T., Moore, J. K., Martiny, A. C. & Lomas, M. W. Biodiversity and stoichiometric plasticity increase pico-phytoplankton contributions to marine net primary productivity and the biological pump. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007756 (2023).

Inomura, K., Deutsch, C., Jahn, O., Dutkiewicz, S. & Follows, M. J. Global patterns in marine organic matter stoichiometry driven by phytoplankton ecophysiology. Nat. Geosci. 15, 1034–1040 (2022).

Arnosti, C. Microbial extracellular enzymes and the marine carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 401–425 (2011).

Comstock, J. et al. Marine particle size-fractionation indicates organic matter is processed by differing microbial communities on depth-specific particles. ISME Commun. 4, ycae090 (2024).

Kaiser, K. & Benner, R. Biochemical composition and size distribution of organic matter at the Pacific and Atlantic time-series stations. Mar. Chem. 113, 63–77 (2009).

Wakeham, S. G., Lee, C., Hedges, J. I., Hernes, P. J. & Peterson, M. J. Molecular indicators of diagenetic status in marine organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 5363–5369 (1997).

D’Souza, F. & Bhosle, N. B. Variation in the composition of carbohydrates in the Dona Paula Bay (west of India) during May/June 1998. Oceanologica Acta 24, 221–237 (2001).

Hamanaka, J., Tanoue, E., Hama, T. & Handa, N. Production and export of particulate fatty acids, carbohydrates and combined amino acids in the euphotic zone. Mar. Chem. 77, 55–69 (2002).

Lee, C., Wakeham, S. & Arnosti, C. Particulate organic matter in the sea: the composition conundrum. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 33, 565–575 (2004).

Jo, N. et al. Different biochemical compositions of particulate organic matter driven by major phytoplankton communities in the northwestern Ross Sea. Front. Microbiol. 12, 623600 (2021).

Geider, R. & La Roche, J. Redfield revisited: variability of C:N:P in marine microalgae and its biochemical basis. Eur. J. Phycol. 37, 1–17 (2002).

Liefer, J. D. et al. Latitudinal patterns in ocean C:N:P reflect phytoplankton acclimation and macromolecular composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2404460121 (2024).

Fabiano, M., Povero, P. & Danovaro, R. Distribution and composition of particulate organic matter in the Ross Sea (Antarctica). Polar Biol 13, 522–533 (1993).

Grosse, J., Nöthig, E.-M., Torres-Valdés, S. & Engel, A. Summertime amino acid and carbohydrate patterns in particulate and dissolved organic carbon across Fram Strait. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 684675 (2021).

Kriest, I. & Oschlies, A. Modelling the effect of cell-size-dependent nutrient uptake and exudation on phytoplankton size spectra. Deep Sea Res. I 54, 1593–1618 (2007).

Mongin, M., Nelson, D. M., Pondaven, P., Brzezinski, M. A. & Tre, P. Simulation of upper-ocean biogeochemistry with a flexible-composition phytoplankton model: C, N and Si cycling in the western Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Res. I 50, 1445–1480 (2003).

Casey, J. R., Aucan, J. P., Goldberg, S. R. & Lomas, M. W. Changes in partitioning of carbon amongst photosynthetic pico- and nano-plankton groups in the Sargasso Sea in response to changes in the North Atlantic Oscillation. Deep Sea Res. II 93, 58–70 (2013).

Passow, U. Transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) in aquatic environments. Prog. Oceanogr. 55, 287–333 (2002).

Myklestad, S., Holm-Hansen, O., Vårum, K. M. & Volcani, B. E. Rate of release of extracellular amino acids and carbohydrates from the marine diatom Chaetoceros affinis. J. Plankton Res. 11, 763–773 (1989).

Granum, E. & Myklestad, S. M. A simple combined method for determination of β-1,3-glucan and cell wall polysaccharides in diatoms. Hydrobiologia 477, 155–161 (2002).

Bidle, K. D. The molecular ecophysiology of programmed cell death in marine phytoplankton. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 7, 341–375 (2015).

Doherty, S. C., Maas, A. E., Steinberg, D. K., Popp, B. N. & Close, H. G. Distinguishing zooplankton fecal pellets as a component of the biological pump using compound-specific isotope analysis of amino acids. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 2827–2841 (2021).

Vrede, K., Heldal, M., Norland, S. & Bratbak, G. Elemental composition (C, N, P) and cell volume of exponentially growing and nutrient-limited bacterioplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 2965–2971 (2002).

Biersmith, A. & Benner, R. Carbohydrates in phytoplankton and freshly produced dissolved organic matter. Mar. Chem. 63, 131–144 (1998).

Pedrosa-Pàmies, R., Conte, M. H., Weber, J. C. & Johnson, R. Carbon cycling in the Sargasso Sea water column: Insights from lipid biomarkers in suspended particles. Prog. Oceanogr. 168, 248–278 (2018).

Panagiotopoulos, C. & Sempéré, R. Analytical methods for the determination of sugars in marine samples: a historical perspective and future directions. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 3, 419–454 (2005).

González-Fernández, C. & Ballesteros, M. Linking microalgae and cyanobacteria culture conditions and key-enzymes for carbohydrate accumulation. Biotechnol. Adv. 30, 1655–1661 (2012).

Mühlenbruch, M., Grossart, H.-P., Eigemann, F. & Voss, M. Mini-review: phytoplankton-derived polysaccharides in the marine environment and their interactions with heterotrophic bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2671–2685 (2018).

Becker, S. et al. Laminarin is a major molecule in the marine carbon cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 6599–6607 (2020).

Parsons, T. R., Stephens, K. & Strickland, J. D. H. On the chemical composition of eleven species of marine phytoplankters. J. Fish. Res. Bd. Can. 18, 1001–1016 (1961).

Brown, M. R. The amino-acid and sugar composition of 16 species of microalgae used in mariculture. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 145, 79–99 (1991).

Brown, M. R., Jeffrey, S. W., Volkman, J. K. & Dunstan, G. A. Nutritional properties of microalgae for mariculture. Aquaculture 151, 315–331 (1997).

Handa, N. Carbohydrate metabolism in the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum. Mar. Biol. 4, 208–214 (1969).

Myklestad, S. Production of carbohydrates by marine planktonic diatoms. II. Influence of the ratio in the growth medium on the assimilation ratio, growth rate, and production of cellular and extracellular carbohydrates by Chaetoceros affinis var. willei (Gran) Hustedt and Skeletonema costatum (Grev.) Cleve. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 29, 161–179 (1977).

Harrison, P. J., Thompson, P. A. & Calderwood, G. S. Effects of nutrient and light limitation on the biochemical composition of phytoplankton. J. Appl Phycol. 2, 45–56 (1990).

Finkel, Z. V. et al. Phylogenetic diversity in the macromolecular composition of microalgae. PLoS ONE 11, e0155977 (2016).

Liefer, J. D. et al. The macromolecular basis of phytoplankton C:N:P under nitrogen starvation. Front. Microbiol. 10, 763 (2019).

Handa, N. & Yanagi, K. Studies on water-extractable carbohydrates of the particulate matter from the northwest Pacific Ocean. Mar. Biol. 4, 197–207 (1969).

Lomas, M. W. et al. Two decades and counting: 24-years of sustained open ocean biogeochemical measurements in the Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Res. II: 93, 16–32 (2013).

Nicholson, D. P. et al. Evaluating triple oxygen isotope estimates of gross primary production at the Hawaii Ocean time-series and Bermuda Atlantic Time-series study sites. J. Geophys. Res. 117, 2010JC006856 (2012).

Li, W. K. W., Glover, H. E. & Morris, I. Physiology of carbon photoassimilation by Oscillatoria thiebautii in the Caribbean Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25, 447–456 (1980).

Ho, S.-H., Chen, C.-Y. & Chang, J.-S. Effect of light intensity and nitrogen starvation on CO2 fixation and lipid/carbohydrate production of an indigenous microalga Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N. Bioresour. Technol. 113, 244–252 (2012).

Thornton, D. C. O. Dissolved organic matter (DOM) release by phytoplankton in the contemporary and future ocean. Eur. J. Phycol. 49, 20–46 (2014).

Goldberg, S. J., Carlson, C. A., Hansell, D. A., Nelson, N. B. & Siegel, D. A. Temporal dynamics of dissolved combined neutral sugars and the quality of dissolved organic matter in the Northwestern Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Res. I 56, 672–685 (2009).

Laws, E. A. et al. Controls on the molecular distribution and carbon isotopic composition of alkenones in certain haptophyte algae. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2, 2000GC000057 (2001).

Mague, T. H., Friberg, E., Hughes, D. J. & Morris, I. Extracellular release of carbon by marine phytoplankton; a physiological approach. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25, 262–279 (1980).

Haug, A. & Myklestad, S. Polysaccharides of marine diatoms with special reference to Chaetoceros species. Mar. Biol. 34, 217–222 (1976).

Huang, G. et al. Secretion of sulfated fucans by diatoms may contribute to marine aggregate formation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 3768–3782 (2021).

Hecky, R. E., Mopper, K., Kilham, P. & Degens, E. T. The amino acid and sugar composition of diatom cell-walls. Mar. Biol. 19, 323–331 (1973).

Benner, R. & Kaiser, K. Abundance of amino sugars and peptidoglycan in marine particulate and dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 118–128 (2003).

Handa, N. & Tominaga, H. A detailed analysis of carbohydrates in marine particulate matter. Mar. Biol. 2, 228–235 (1969).

Hitchcock, G. L. The concentration of particulate carbohydrate in a region of the West Africa upwelling zone during March, 1974. Deep Sea Res. 24, 83–93 (1977).

Ittekkot, V., Degens, E. T. & Brockmann, U. Monosaccharide composition of acid-hydrolyzable carbohydrates in particulate matter during a plankton bloom. Limnol. Oceanogr. 27, 770–776 (1982).

Liebezeit, G. Particulate carbohydrates in relation to phytoplankton in the euphotic zone of the Bransfield Strait. Polar Biol. 2, 225–228 (1984).

Hernes, P. J., Hedges, J. I., Peterson, M. L., Wakeham, S. G. & Lee, C. Neutral carbohydrate geochemistry of particulate material in the central equatorial Pacific. Deep Sea Res. II 43, 1181–1204 (1996).

Sannigrahi, P., Ingall, E. D. & Benner, R. Cycling of dissolved and particulate organic matter at station Aloha: Insights from 13C NMR spectroscopy coupled with elemental, isotopic and molecular analyses. Deep Sea Res. I52, 1429–1444 (2005).

Carlson, C. A., Ducklow, H. W. & Michaels, A. F. Annual flux of dissolved organic carbon from the euphotic zone in the northwestern Sargasso Sea. Nature 371, 405–408 (1994).

Burd, A. B. et al. Assessing the apparent imbalance between geochemical and biochemical indicators of meso- and bathypelagic biological activity: what the @$♯! is wrong with present calculations of carbon budgets? Deep Sea Res. II 57, 1557–1571 (2010).

Fawcett, S. E., Johnson, K. S., Riser, S. C., Van Oostende, N. & Sigman, D. M. Low-nutrient organic matter in the Sargasso Sea thermocline: A hypothesis for its role, identity, and carbon cycle implications. Mar. Chem. 207, 108–123 (2018).

Steinberg, D. K. et al. Overview of the US JGOFS Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS): a decade-scale look at ocean biology and biogeochemistry. Deep Sea Res. II 48, 1405–1447 (2001).

Sprintall, J. & Tomczak, M. Evidence of the barrier layer in the surface layer of the tropics. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 97, 7305–7316 (1992).

Bishop, J. K. B., Lam, P. J. & Wood, T. J. Getting good particles: accurate sampling of particles by large volume in-situ filtration. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 10, 681–710 (2012).

Lorrain, A., Savoye, N., Chauvaud, L., Paulet, Y.-M. & Naulet, N. Decarbonation and preservation method for the analysis of organic C and N contents and stable isotope ratios of low-carbonated suspended particulate material. Analytica Chim. Acta 491, 125–133 (2003).

Engel, A. & Händel, N. A novel protocol for determining the concentration and composition of sugars in particulate and in high molecular weight dissolved organic matter (HMW-DOM) in seawater. Mar. Chem. 127, 180–191 (2011).

Hannides, C. C. S., Popp, B. N., Choy, C. A. & Drazen, J. C. Midwater zooplankton and suspended particle dynamics in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre: a stable isotope perspective. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 1931–1946 (2013).

Lindroth, P. & Mopper, K. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of subpicomole amounts of amino acids by precolumn fluorescence derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde. Anal. Chem. 51, 1667–1674 (1979).

Liu, S. et al. Linkages among dissolved organic matter export, dissolved metabolites, and associated microbial community structure response in the northwestern Sargasso Sea on a seasonal scale. Front. Microbiol. 13, 833252 (2022).

Kaiser, K. & Benner, R. Organic matter transformations in the upper mesopelagic zone of the North Pacific: Chemical composition and linkages to microbial community structure. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 117, 7141 (2012).

Carr, F. Orthogonal Linear Regression (https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/16800-orthogonal-linear-regression), MATLAB Central File Exchange. MATLAB Central File Exchange (2023).

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. PBC (RStudio, 2020).