Abstract

Warm sea surface temperature anomalies in the north tropical Atlantic are conducive to increased intensity and frequency of Atlantic hurricanes. The period 2023-2024 saw two consecutive warm events but with distinct anomaly patterns. Here we use observations and model outputs over the past several decades to determine whether there exists inherent diversity in north tropical Atlantic surface temperature spatial structures and impacts. We find two distinctive modes of variability: a basin-wide mode and a coastal mode, underpinned by differing relationships between air-sea heat flux and sea surface temperature anomalies. The basin-wide mode has a stronger influence on Atlantic hurricane activity due to its more westward and persistent anomaly pattern. Since the 1990s, the well-known impact from El Niño-Southern Oscillation on the north tropical Atlantic is felt through its influence on the basin-wide mode. Our results highlight the importance of distinguishing the two distinctive modes in assessing and predicting their impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

North tropical Atlantic climate variability, referred to as the NTA mode, features spatially-coherent sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies that typically span from the equator to about 20°N and peak in boreal spring1,2. The NTA mode is mainly driven by anomalous northeasterly trade wind and anomalous latent heat flux3,4,5,6, a consequence of localized air-sea interaction and remote forcing from El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)1,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. A positive NTA (pNTA) event, characterized by warm SST anomalies, exerts a profound impact to Atlantic-rim continental regions. Coupled with a northward swing of the Atlantic Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a pNTA event favors droughts and subsequent wildfires in the Amazon basin and Northeast Brazil15,16,17,18. Although the NTA mode matures in boreal spring, it still has considerable strength in the Atlantic hurricane season which runs June to November, as a strong pNTA is often associated with an active hurricane season with stronger and more frequent hurricanes striking the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico19,20.

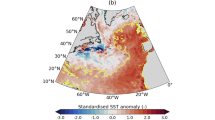

Observational records reveal several remarkable pNTA events, such as in 2005 and 2010, with exceptional warming and consequential impacts21,22,23,24. An unusual sequence of two-consecutive pNTA events occurred in 2023–2024. In the boreal spring of 2023, an SST warming pattern developed off the West African coast while the tropical Pacific was still in a La Niña condition (Fig. 1b). The anomalous warming then decayed but reappeared when a strong El Niño began to develop in boreal summer. After the El Niño peaked in the late 2023, large-scale warming spread over the north tropical Atlantic in 2024 with an unprecedented amplitude (Fig. 1a). The 2024 pNTA event ranks as the second highest NTA warm anomaly following the previous record in 2010 after the mean warming trend is removed.

Spatial anomaly patterns of SST (shadings) and surface wind (vectors) over the north tropical Atlantic in (a) MAM-averaged 2024 and (b) MAM-averaged 2023. Spatial patterns of regression coefficients for anomalous MAM-averaged SST (shadings) and surface wind (vectors) regressed onto (c) the first principal component (PC1) extracted from the first EOF mode (EOF1) and (d) the second principal component (PC2) extracted from the second EOF mode (EOF2). Only regression coefficients that exceed the 90% confidence level according to the Student’s t-test are shown. Same as (c-d), but for (e) BNTA index and (f) CNTA index, constructed by the combination of PC1 and PC2 (see ‘Definition of two NTA flavors’ in Methods). Values in parentheses in (c)-(f) indicate the proportion of variance explained by the corresponding EOF mode. Time series of (g) traditional NTA index (normalized), calculated as MAM-averaged SST anomalies over 57°W-15°W, 5°N-23°N (see ‘Definitions of other climate indices’ in Methods), and (f) BNTA (red curve) and CNTA (green curve) index. The 2023 and 2024 pNTA events are marked out as green and red dots, respectively. The NTA mode consists of two different flavors with distinct spatial patterns as seen in the 2023 and 2024 pNTA events.

The extremely warm north tropical Atlantic during 2023-2024 was followed by two consecutive above-normal hurricane seasons. As the fourth-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record, the 2023 hurricane season produced 7 hurricanes with accumulated cyclone energy reaching 139 104knots2 25. The 2024 hurricane season even saw more high-impact hurricanes with accumulated cyclone energy reaching 162 104knots2. In early July 2024, the earliest-formed Category-5 hurricane on record (Beryl) hit Texas and caused at least 68 fatalities26. In late September and early October, two consecutive major hurricanes (Helene and Milton) made landfall in Florida, claiming at least 250 lives resulting in an estimated loss of $250 billion to the southeastern United States27. The massive loss makes them both the deadliest and costliest hurricanes to the mainland U.S. since Katrina in 200528.

The 2023 and 2024 pNTA anomalies manifested as consecutive events, but here we show that substantial differences exist in their preconditions, spatial patterns, and impacts. In contrast to a confined warming off the west coast of Africa in 2023, the 2024 event, fueled by the 2023/24 strong El Niño, saw a basin-wide warming, leading to more destructive landfalling hurricanes. To date, the NTA mode has been considered as a single SST anomaly pattern, but the differences in the 2023 and 2024 pNTA events highlight that substantial diversity exists in its dynamics and impacts. Here we show that there are two distinctive flavors of the NTA mode with substantially different dynamical preconditioning, spatial patterns, and impacts on Atlantic hurricane activity.

Results

Two flavors of the NTA mode

The difference in the SST anomaly center between the 2023 and 2024 pNTA events indicates that at least two indices are required to depict them. We apply an empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis of March-May (MAM) SST anomalies in the north tropical Atlantic Ocean (80°W-10°W, 5°N-20°N) to extract two modes of the NTA (see ‘Definition of two NTA flavors’ in Methods). The first EOF mode (EOF1), used to represent the traditional NTA mode29, accounts for 67.6% of the total SST variance. Its positive phase depicts an overall SST warming over the entire north tropical Atlantic Ocean but with a concentrated warming in the coastal east, associated with southwesterly anomalies against the climatological trade winds30 (Fig. 1c). The second EOF mode (EOF2) features a zonal dipole-like pattern, with an anomalous cooling in the West African coastal upwelling area and warming in the Atlantic warm pool region, accounting for 10.8% of the total SST variance (Fig. 1d). The EOF2 is significantly separated from neighboring modes according to the North test31.

The EOF1 captures the averaged spatial pattern of all NTA events over time, and the EOF2 modifies the EOF1 SST anomaly to produce an inter-event difference in the spatial pattern. As such, we can construct two indices of two NTA flavors by a combination of EOF1 and EOF2. A basin-wide warming event, as seen in 2024, can be described by the warm anomaly in the northwestern tropical Atlantic in EOF2 superimposed on the overall warm anomaly in EOF1 making the SST anomaly center located in the central basin (Fig. 1e). By contrast, a coastal warming event, as seen in 2023, can be described by the opposite sign of EOF2 superimposed onto EOF1 making the SST anomaly center in the West African coast, but with the absence of warming in the northwestern tropical Atlantic (Fig. 1f).

Accordingly, we define the two indices for the basin-wide NTA mode (BNTA) and the coastal NTA mode (CNTA) by a combination of the associated first and second principal component (PC1 and PC2), as \({BNTA}=({PC}1+{PC}2)/\surd 2\) and \({CNTA}=({PC}1-{PC}2)/\surd 2\), respectively (see ‘Definition of two NTA flavors’ in Methods). The two indices are orthogonal and therefore capture SST variability of two different flavors of the NTA mode. As such, the 2024 pNTA is a strong positive BNTA event while the 2023 pNTA is a strong CNTA event (Fig. 1h), a distinct feature of two consecutive warming events (Fig. 1g). We also select 6 years when BNTA > 1 s.d. and 6 years when CNTA > 1 s.d. to construct composites of their spatial patterns, which accord with the respective spatial patterns defined by EOF approach (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To test the robustness of the two different flavors of the NTA mode, we apply the same EOF analysis on reanalysis products beyond the satellite era (see ‘Datasets’ in Methods). The nature of two flavors is a consistent feature across different datasets and time periods (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, we conduct the same EOF analysis on outputs of historical simulations from 48 state-of-the-art climate models that participated in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6, see ‘Datasets’ in Methods)32. All the CMIP6 models simulate the two flavors, with reasonable spatial patterns for the multi-model ensemble mean that distinguish the BNTA and CNTA mode in a similar way to the observations (Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 1). The consistency between models and the observation, across reanalysis products and models, suggests that diversity of the NTA mode is a real feature of the climate system.

Different heat flux response generates the two flavors

The two flavors of the NTA mode differ in their spatial pattern, evolution and dynamics. To compare their evolution, we conduct a lead-lag regression of monthly fields onto the BNTA and CNTA index, respectively. For a positive BNTA, a prominent weakening of the North Atlantic Subtropical High in boreal winter drives basin-scale southwesterly anomalies and initial SST warm anomalies. The southwesterly and warm anomalies reinforce each other through a positive wind-evaporation-SST (WES) feedback33 over the central basin, reaching a peak in boreal spring but persisting into early summer (Supplementary Fig. 4). For a positive CNTA, however, SST warming is confined to the coast zone of west Africa, driven by more localized alongshore wind anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 5). Different from a basin-wide warming, the coastal warming peaks in early boreal spring and decays from late spring (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The different evolution between BNTA and CNTA suggests different dynamics in generating the two flavors. Previous studies have found that the WES feedback dominates large-scale SST variability over the north tropical Atlantic3,5. A mixed-layer heat budget analysis further reveals that latent heat flux dominates the evolution of both NTA modes (Supplementary Fig. 6a-b). In addition to the presence of coastal upwelling, which plays a part in coastal SST variability34, the most distinctive difference between the two modes is the relationship of SST to latent heat flux anomalies. For a positive BNTA, anomalous downward latent heat flux acts as a positive feedback to southwesterly winds and SST warm anomalies over the central basin from boreal winter to early summer, driving growth of SST warm anomalies into summer (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 6a). For a positive CNTA, however, latent heat flux firstly acts as positive feedback to alongshore southerly winds and SST warm anomalies, but then switches to negative feedback to damp the warming in the east coast (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 6b).

A longitude-time diagram of regressed monthly SST (shadings), surface wind (vectors) and latent heat flux (dots) anomalies associated with (a) BNTA and (b) CNTA, meridionally averaged over 5°N to 20°N. Purple (blue) dots indicate anomalous downward (upward) latent heat fluxes, with different sizes indicating their magnitudes. For SST and latent heat flux, only statistically significant values above the 90% confidence level are shown; for surface wind, significant (insignificant) signals above (below) the 90% confidence level are shown in black (grey) vectors. c Nonlinear relationship between PC1 (x-axis) and PC2 (y-axis). Red dots denote four strong positive BNTA events as in 1983, 2005, 2010 and 2024; green dots denote three strong positive CNTA events as in 2000, 2008 and 2023. \(\alpha\) is the quadratic coefficient of the nonlinear fit \({PC}2\left(t\right)=\alpha {\left[{PC}1(t)\right]}^{2}+\beta {PC}1\left(t\right)+\gamma\), which is statistically significant above the 99% confidence level. Fitted quadratic function is shown in grey curve. The different heat flux feedback generates the two NTA flavors.

Such a different response is mainly due to a difference in the background mixed-layer depth between central basin and east coast (Supplementary Fig. 7), as the strong coastal upwelling leads to a shallower mixed layer off the West African coast compared with central basin of the north tropical Atlantic. A thicker mixed layer over the central basin indicates a great capacity of heat storage such that a positive BNTA warms slowly, which in turn favors persistent warming from latent heat flux. By contrast, a shallower mixed layer near the West African coast enables a more rapid warming in the coastal zone than in the central basin, and the faster warming in turn leads to a fast thermal damping that curtails further SST warming. To illustrate the difference, we decompose the latent heat flux anomalies into components arising from WES feedback and Newtonian damping (see ‘Decomposition of latent heat flux’ in Methods)35,36,37. For a positive BNTA, the WES feedback is greater than the Newtonian damping in the central basin, favoring SST warming towards early summer (Supplementary Fig. 8a). But for a positive CNTA, the Newtonian damping starts to overcome WES feedback beginning in late spring, curtailing CNTA warming. This leads to a weaker warming than for the BNTA, such that the seasonal cycle can trigger a demise in the CNTA more easily (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

The different heat flux response is associated with a nonlinearity between the two flavors of the NTA mode, that is, the two PC time series display a quadratic relationship of \({PC}2\left(t\right)=\alpha {\left[{PC}1(t)\right]}^{2}+\beta {PC}1\left(t\right)+\gamma\) (Fig. 2c). The value of \(\alpha\) is −0.34, which significantly differs from zero above the 99% confidence level. Such nonlinearity between the two EOF modes indicates that strong pNTA events, as seen in 2024, locate in the quadrant where both PC1 and PC2 are positive, as is the case for other strong pNTA events in 1983, 2005, and 2010 (red dots in Fig. 2c). On the other hand, a moderate pNTA event tends to appear in the quadrant where PC1 is positive but PC2 is negative, leading to the warming centered in the east coast as a positive CNTA event, as seen in 2023 (green dot in Fig. 2c).

Distinct impact on Atlantic hurricane activity

A strong NTA warming reduces vertical wind shear to weaken atmospheric stability, as well as increases low-level vorticity and mid-level humidity over the main development region of Atlantic hurricanes (80°W-20°W, 10°N-20°N, box in Supplementary Fig. 9a-b), leading to a more active Atlantic hurricane season22,38,39,40. In addition, an NTA warming during boreal spring can trigger a Gill-type subtropical teleconnection to cool the equatorial Pacific and result in La Niña development in the following months41,42. A joint impact of both a warm NTA and a developing La Niña phase further reduces vertical wind shear to favor more frequent and intense hurricanes43,44,45.

We examine the diverse impacts of the two NTA flavors on hurricane-related atmospheric conditions during June-September (JJAS) when springtime NTA warming still has a lagged effect (Supplementary Fig. 10a-b). Compared to CNTA, the SST warm anomaly center associated with BNTA is more superimposed on the Atlantic warm pool where the background SST is higher than in the coastal zone of west Africa46. The BNTA warm anomaly also persists more into the hurricane season than the CNTA warm anomaly (Fig. 2a) and is more effective in triggering an early-stage La Niña than CNTA due to its stronger persistence and more westward anomaly center (Supplementary Fig. 9a-b). Due to this joint impact, a positive BNTA leads to a greater increase in low-level vorticity and mid-level humidity (Supplementary Fig. 9c-d; 10c-d), as well as a greater decrease in vertical wind shear and increase in anomalous ascending motion (Supplementary Fig. 9e-f; 10e-f; see ‘Definitions of hurricane metrics’ in Methods) over the main development region for hurricanes, favoring their genesis and development.

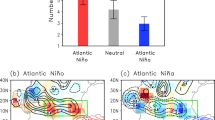

We select 6 years when BNTA > 1 s.d. and 6 years when CNTA > 1 s.d. to construct composites and compare the spatial pattern and magnitude of Atlantic hurricane activity. We focus on tropical cyclone genesis frequency (TCGF), track density (TCTD), and accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) during JJAS, which are common metrics used to measure the general activity of tropical cyclones (see ‘Definitions of hurricane metrics’ in Methods). A positive BNTA tends to be followed by more cyclone geneses over the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 3a), whereas a positive CNTA is followed by more geneses in the coastal zone of West Africa (Fig. 3b). Consistent with the contrast, there are more westward-shifted tropical cyclone tracks following a positive BNTA (Fig. 3c), but more eastward-shifted tropical cyclone tracks following a positive CNTA (Fig. 3d). Thus, probability of landfalling tropical cyclones with devasting impacts to Caribbean and U.S. southeast coast43,47 is higher for a positive BNTA than for a CNTA. The contrast is also reflected by a stronger anomalous ACE over the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico following a positive BNTA (Fig. 3e), whereas less cyclone energy is accumulated following a positive CNTA (Fig. 3f). Therefore, a positive BNTA tends to favor stronger Atlantic hurricane activity with more severe impacts to Caribbean and U.S. southeastern coastal region than a positive CNTA.

Spatial patterns of composite anomalies of JJAS TCGF for (a) six positive BNTA events (as in 1983, 1995, 1998, 2005, 2010, 2024) and (b) six positive CNTA events (as in 1987, 1997, 2000, 2008, 2020, 2023). Stippled areas indicate where composite anomalies are statistically significant above the 90% confidence level according to the two-tailed t-test. c, d Same as (a, b), but for TCTD. e, f Same as (a, b), but for ACE. A positive BNTA event has an overall stronger impact on Atlantic hurricane activity due to its more westward and persistent warm anomaly pattern.

Collapsing ENSO-CNTA teleconnection since 1990s

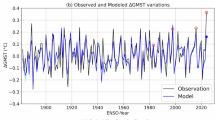

An El Niño (La Niña) in boreal winter can trigger a positive (negative) NTA event in the following spring via atmospheric teleconnection and oceanic Kelvin waves7,8,9,10,11, but this teleconnection has weakened since the 1990s48,49. Here we examine the ENSO-NTA teleconnection in terms of the BNTA and CNTA modes separately by computing a 31-year running correlation from 1950 onward. The ENSO-BNTA teleconnection is robust and statistically significant over the entire period (Fig. 4a). In contrast, although statistically significant and comparable to that of the ENSO-BNTA teleconnection before 1990s, the ENSO-CNTA teleconnection after 1990s weakens (Fig. 4a). Hence, the observed weakening in the ENSO-NTA teleconnection is primarily attributed to a collapsing ENSO-CNTA teleconnection.

a Time series of 31-year running correlation coefficient between DJF-averaged Niño3.4 with subsequent MAM BNTA (red line) and CNTA (blue line) index during the period of 1950–2024. The x-axis indicates the central year of 31-year running window (for example, coefficient at year 2000 represents the running correlation for the period of 1985–2015). Dots on each line indicate the correlation coefficient is statistically significant above the 90% confidence level. Spatial patterns of ENSO teleconnection to SST variability in the north tropical Atlantic during two different periods, represented by regression coefficients of MAM-averaged SST anomalies onto DJF-averaged Niño3.4 during the period of (b) 1965-1999 (P1) and (c) 2000–2024 (P2). The ENSO-CNTA teleconnection has been weakening since 1990s whereas the ENSO-BNTA teleconnection remains robust and stable.

The contrasting evolution of ENSO teleconnection with the BNTA and CNTA modes coincides with a phase transition of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO, Supplementary Fig. 10a)48,50. We compare the spatial patterns of ENSO teleconnection over the north tropical Atlantic during a negative phase (1965–1999, P1) and a positive phase (2000–2024, P2) of the AMO and find that ENSO-forced SST variability features a traditional NTA pattern during P1 (Fig. 4b), but a BNTA-like pattern without an SST anomaly center off the African coast during P2 (Fig. 4c). This change is reflected in an ENSO-CNTA teleconnection that decreases from 0.53 (P1) to −0.08 (P2), but an ENSO-BNTA teleconnection increases from 0.49 (P1) to 0.71 (P2).

Such contrasting response is caused by AMO-related changes in both mean state and ENSO characteristics. A positive phase of the AMO leads to a warmer northern hemisphere with a northward shift of Atlantic Intertropical Convergence Zone51,52 (Supplementary Fig. 11b). As a result, northerly trade winds weaken along the West African coast inhibited by cross-equatorial southerly anomalies, but northeasterly trade winds strengthen over the central basin at higher latitudes (Supplementary Fig. 11b). A stronger (weaker) mean trade wind corresponds to a more (less) intense WES feedback33,35,53. In addition, a positive phase of the AMO favors more frequent central Pacific ENSO events than eastern Pacific ENSO events48,54,55, which leads to a more westward-shifted atmospheric teleconnection pattern that less effectively weakens the North Atlantic Subtropical High and thus trade wind anomalies in the West African coastal region14,56,57 (Supplementary Figs. 12-14). This in turn results in a weaker ENSO impact on coastal SST variability and a weaker CNTA after 2000 (Supplementary Fig. 14). In contrast, SST variability in the central basin associated with the BNTA is more responsive to ENSO teleconnection forcing during the post-2000 period than during the pre-2000 period.

CNTA variability remains active and comparable to BNTA variability despite a collapsed ENSO-CNTA teleconnection (Supplementary Fig. 15), suggesting a strengthened local feedback that dominates CNTA variability, making the CNTA mode less predictable from remote influences such as ENSO. During the positive phase of the AMO, weakened northerly coastal winds make it easier to generate southerly anomalies and establish local convection. The importance of local forcing is highlighted in 2023, when a strong positive CNTA occurred following a multi-year La Niña. However, a despite an overall weakening in the ENSO-NTA teleconnection previously found48,49, ENSO’s influence on the BNTA remained strong as did the BNTA impact on Atlantic hurricanes.

Discussion

We find that the NTA mode exhibits diversity featuring two different flavors, each with a distinct spatial pattern, dynamics, and climatic impact, which we refer to as the BNTA and CNTA modes. The two flavors are characterized by different SST anomaly centers, in the central basin for BNTA and off the northwest coast of Africa for CNTA. A contrasting background mixed-layer depth, deep in the central basin but shallow off the west African coast, results in a different response to wind forcing and air-sea latent heat flux with more persistent SST anomalies for the BNTA mode but faster decaying SST anomalies for the CNTA mode. Due to a more westward and persistent warm SST anomaly pattern, a positive BNTA tends to precondition a stronger Atlantic hurricane season than a positive CNTA, with higher probability of landfalling hurricanes in the Caribbean and along the U.S. southeast coast. Our finding explains the different spatial patterns and dynamics as seen in 2023 and 2024, as well as different impacts on the Atlantic hurricane season in historical NTA events. The diversity also explains the post-1990s weakening in the ENSO-NTA teleconnection, which we find is due to a weakening of the ENSO-CNTA teleconnection likely driven by a negative-to-positive phase transition of the AMO, while the ENSO-BNTA remains stable. Consequently, since 1990s, ENSO impacts on the north tropical Atlantic are conveyed mainly through the BNTA mode. Our study highlights an inherent diversity that should be considered for studies of the NTA variability, including its dynamics, interaction with the tropical Pacific, and effects on Atlantic hurricane activity. Although other factors beyond the NTA region, such as ENSO, should be considered for hurricane prediction, our findings indicate that the NTA SST influence on Atlantic hurricane activity is more nuanced than previously thought due to the existence of the two NTA modes.

Methods

Datasets

We use the monthly SST data from NOAA Optimum Interpolation SST (OISST) Version 2 for the period of 1982-202458. Based on satellite products and in situ data from ships and buoys, OISST is most accurate and truthful to the observations, and therefore employed to conduct main results in this study. To validate the results in OISST, we also use two sets of reanalysis SST data for a common period of 1950–2024, they are Hadley Center Global Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature (HadISST) Version 1.159 and NOAA Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature Version 560. Particularly, we use HadISST to study the evolution of ENSO teleconnection with the two flavors of the NTA mode in recent decades. For atmospheric fields on both surface layer and pressure level, we use the data from National Centers of Environmental Predictions (NCEP-NCAR) Reanalysis 1 for the period of 1950–202461. Mixed layer depth data is obtained from NCEP Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS) covering the period of 1980–202462. Monthly anomalies are constructed with reference to a full-period climatology of each dataset, and then linearly detrended to remove global warming signal.

To investigate the impact on Atlantic hurricane activities, we obtain the best-track tropical cyclone (TC) data from the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (iBTrACS)63, containing the locations (longitude and latitude) and intensity (surface wind speed) of TC records at a 6-hour temporal resolution. A TC genesis location is defined as where its intensity is equal to or larger than 35 knot for the first time, and then a TC track is calculated at 6-hour intervals.

To validate the inherent diversity of the NTA mode as seen in observations, we further analyze outputs from 48 climate models participated in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), forced under historical anthropogenic and natural forcings from 1850 to 201432. To be comparable with observational datasets, we focus on the period of 1950–2014 for model outputs. All variables in each model are re-gridded into a common 1°\(\times\)1° resolution and then detrended prior to analysis.

Definition of two NTA flavors

To extract the leading modes of SST variability in the north tropical Atlantic, we apply an EOF analysis64 to MAM-averaged SST anomalies over 80°W-10°W, 5°N-20°N, yielding two leading modes each with a principal pattern and a PC scaled to unity. We focus on the MAM season in which an NTA event typically peaks. EOF1 exhibits an overall SST warming over the entire basin with a concentrated warming in the costal east (Fig. 1c), and is used to represent a traditional NTA mode29. EOF2 showcases a dipole-like pattern zonally, featuring as anomalous cooling along the west coast of Africa and warming in the central basin (Fig. 1d). An EOF significance test31 indicates that these two EOFs are robust and stable given the sample size of our data set. We define indices for the two distinct flavors of NTA mode through a linear combination of the two leading EOFs, namely \(({PC}1+{PC}2)/\surd 2\) for BNTA and and \(({PC}1-{PC}2)/\sqrt{2}\) for CNTA. This approach has previously been employed to distinguish two flavors of other prominent modes of climate variability, such as ENSO65,66, the Indian Ocean Dipole67,68, and Atlantic Niño/Niña69. The demoninator of \(\surd 2\) allows both BNTA and CNTA index to be scaled to unity.

Definitions of other climate indices

The Niño3.4 index is calculated by DJF SST anomalies averaged within 120°W-170°W, 5°S-5°N. The NTA index is calculated by MAM SST anomalies averaged within 57°W-15°W, 5°N-23°N70. To depict the variance of eastern Pacific ENSO and central Pacific ENSO, we apply an EOF analysis to DJF SST anomalies over 140°E-80°W, 15°S-15°N, yielding two leading modes each with a principal pattern and a PC scaled to unity. The eastern Pacific ENSO index is calculated by E-index \(=({PC}1-{PC}2)/\surd 2\) while the central Pacific ENSO index is calculated by C-index \(=({PC}1+{PC}2)/\surd 2\)65,66.

Mixed-layer heat budget analysis

We diagnose the role of air-sea interactions and oceanic processes in the development of the NTA modes based on a mixed layer heat budget analysis:

where we focus on the mixed layer heat budget with all terms low pass filtered to extract interannual variations. The variable \(T\) is the potential temperature averaged over the mixed layer; \({{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}\cdot \nabla T\) is the horizontal advection of temperature by meridional and zonal ocean current \({{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}\); \(H\) is the climatological mixed layer depth; \({T}_{d}\) is the potential temperature at the bottom of mixed layer; w is the entrainment velocity, calculated as \(w=\frac{\partial H}{\partial t}+{u}_{d}\frac{\partial H}{\partial x}+{v}_{d}\frac{\partial H}{\partial y}+{w}_{d}\) (\({u}_{d}\), \({v}_{d}\), \({w}_{d}\) are the zonal, meridional, vertical ocean current velocities at the bottom of mixed layer); \({Q}_{{net}}\) is the downward net air-sea surface heat flux, which is the sum of latent heat flux (\({Q}_{{LHF}}\)), sensible heat flux, longwave radiation flux, and shortwave radiation flux (\({Q}_{{SWR}}\)); \(\rho\) is the seawater density (1025 kg m−3); \({C}_{p}\) is the specific heat of seawater at constant pressure (3986 J kg−1 °C−1); \(R\) is the residual term including mixing and diffusion processes. Coordinates \(x\) and \(y\) represent the zonal and meridional directions, and \(t\) represents time. Regardless of residual term, the mixed layer heat budget can be generally divided into four parts: change in heat content \(\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\), surface heat flux \(\frac{{Q}_{{net}}}{\rho {C}_{p}H}\), horizontal advection \(-{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}\cdot \nabla T\), and entrainment \(-w\frac{T-{T}_{d}}{H}\). The relative contributions of latent heat flux and shortwave radiation flux can be calculated as \(\frac{{Q}_{{LHF}}}{\rho {C}_{p}H}\) and \(\frac{{Q}_{{SWR}}}{\rho {C}_{p}H}\), respectively.

Decomposition of latent heat flux

We decompose surface latent heat flux anomalies (\({Q}_{E}^{{\prime} }\)) on interannual time scales into components arising from atmospheric forcing such as surface wind changes, and oceanic response to SST changes35,36,37:

where \({Q}_{N}^{{\prime} }=\bar{{Q}_{E}}\alpha T\) is Newtonian damping, which is derived from Newton’s law of cooling, refers to thermodynamical relaxation of abnormal SST back to a prescribed equilibrium SST at a rate proportional to its deviation from that equilibrium state. \(\alpha =\frac{1}{{q}_{s}}\frac{d{q}_{s}}{{dT}}\) is a damping coefficient, with \({q}_{s}\) is the saturated specific humidity following the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. We neglect the surface air-sea temperature variations of relative humidity because in the tropics, strong air-sea coupling allows for an almost instantaneous near-surface atmospheric adjustment to SST variations, maintaining a negligible air-sea temperature difference and small temporal variations of relative humidity. We also examine that in the north tropical Atlantic, effects of air-sea temperature difference and relative humidity are insignificant and very weak compared with surface wind speed changes. Then \({Q}_{A}^{{\prime} }=\bar{{Q}_{E}}\frac{{U}^{{\prime} }}{\bar{U}}\) is the WES effect and \(U\) is surface wind speed. Here overbar denotes the climatology and prime denotes the anomaly, respectively. We verify that the sum of different latent heat flux components reproduces the total variation of actual latent heat flux.

Definitions of hurricane metrics

We utilize three common metrics, tropical cyclone genesis frequency (TCGF), track density (TCTD), and accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), to evaluate the general activity of Atlantic hurricanes. We apply an adjusted kernel density method to define the TCGF (TCTD) on each grid was counted as the number of TCs (≥35 knots) generated in (passed by) an area of 20° zonally and 10° meridionally away from the center of the grid point, with a 1°grid spacing71. Such approach transforms discrete genesis points into spatial-continuous records and results in a stable spatial relationship between the TCGF/TCTD and related environmental and oceanic factors. We choose a 20°\(\times\)10° box because the synoptic waves (such as equatorial Rossby waves, mixed Rossby–gravity waves, and easterly waves, or other types of synoptic disturbances) triggering TC genesis generally have a zonal scale of about 2,000 km and a meridional e-folded scale72,73,74. We also conduct a sensitivity test by using a 30°\(\times\)15° and 10°\(\times\)5° box. Generally, the result from a 30°\(\times\)15° box shows a similar correlation with that using a 20°\(\times\)10° box, whereas the correlation contains much noise by using a 10°\(\times\)5° box. Subtropical storms are excluded in our calculation. The ACE is calculated by summing the squares of maximum sustained wind speed of TC at 6-hour intervals after removing post-tropical stages75.

Data availability

All datasets used in this study are publicly accessible and can be downloaded from the following websites: OISST v2, https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.html; HadISST v1.1, https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/; ERSST v5, https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html; NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis 1, https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis.html; GODAS, https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.godas.html; IBTrACS v4.01, https://doi.org/10.25921/82ty-9e16; CMIP6 from https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The post-processed data of hurricane metrics (TCGF, TCTD, ACE) used in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15760345.

Code availability

The codes to calculate results associated with main figures in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15760345.

References

Czaja, A., Van der Vaart, P. & Marshall, J. A diagnostic study of the role of remote forcing in tropical Atlantic variability. J. Clim. 15, 3280–3290 (2002).

Huang, B., Schopf, P. S. & Shukla, J. Intrinsic ocean–atmosphere variability of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. J. Clim. 17, 2058–2077 (2004).

Xie, S.-P. & Carton, J. A. Tropical Atlantic variability: Patterns, mechanisms, and impacts. Earth’s Climate: The Ocean–Atmosphere Interaction. Geophys. Monogr. 147, 121–142 (2004).

Chang, P., Ji, L. & Li, H. A decadal climate variation in the tropical Atlantic Ocean from thermodynamic air-sea interactions. Nature 385, 516–518 (1997).

Amaya, D. J., DeFlorio, M. J., Miller, A. J. & Xie, S.-P. WES feedback and the Atlantic meridional mode: Observations and CMIP5 comparisons. Clim. Dyn. 49, 1665–1679 (2017).

Foltz, G. R. et al. The tropical Atlantic observing system. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 206 (2019).

Nobre, P. & Shukla, J. Variations of sea surface temperature, wind stress, and rainfall over the tropical Atlantic and South America. J. Clim. 9, 2464–2479 (1996).

Enfield, D. B. & Mayer, D. A. Tropical Atlantic sea surface temperature variability and its relation to El Niño-Southern Oscillation. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 102, 929–945 (1997).

Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. Interaction between tropical Atlantic variability and El Niño–Southern oscillation. J. Clim. 13, 2177–2194 (2000).

Giannini, A., Kushnir, Y. & Cane, M. A. Interannual variability of Caribbean rainfall, ENSO, and the Atlantic Ocean. J. Clim. 13, 297–311 (2000).

García-Serrano, J., Cassou, C., Douville, H., Giannini, A. & Doblas-Reyes, F. J. Revisiting the ENSO teleconnection to the tropical North Atlantic. J. Clim. 30, 6945–6957 (2017).

Cai, W. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav4236 (2019).

Jiang, L. & Li, T. Relative roles of El Niño-induced extratropical and tropical forcing in generating Tropical North Atlantic (TNA) SST anomaly. Clim. Dyn. 53, 3791–3804 (2019).

Liu, Y., Li, Z., Lin, X. & Yang, J. C. Enhanced eastern Pacific ENSO-tropical North Atlantic connection under greenhouse warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095332 (2021).

Giannini, A., Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. Oceanic forcing of Sahel rainfall on interannual to interdecadal time scales. Science 302, 1027–1030 (2003).

Cai, W. et al. Climate impacts of the El Niño–southern oscillation on South America. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 215–231 (2020).

Liu, Y., Cai, W., Lin, X. & Li, Z. Increased extreme swings of Atlantic intertropical convergence zone in a warming climate. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 828–833 (2022).

Liu, Y., Cai, W., Zhang, Y., Lin, X. & Li, Z. Near-term projection of Amazon rainfall dominated by phase transition of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 46 (2024).

Xie, L., Yan, T., Pietrafesa, L. J., Morrison, J. M. & Karl, T. Climatology and interannual variability of North Atlantic hurricane tracks. J. Clim. 18, 5370–5381 (2005).

Vimont, D. J. & Kossin, J. P. The Atlantic meridional mode and hurricane activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L07709 (2007).

Foltz, G. R. & McPhaden, M. J. Unusually warm sea surface temperatures in the tropical North Atlantic during 2005. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L19703 (2006).

Trenberth, K. E. & Shea, D. J. Atlantic hurricanes and natural variability in 2005. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L12704 (2006).

Zeng, N. et al. Causes and impacts of the 2005 Amazon drought. Environ. Res. Lett. 3, 014002 (2008).

Lewis, S. L., Brando, P. M., Phillips, O. L., Van Der Heijden, G. M. & Nepstad, D. The 2010 amazon drought. Science 331, 554–554 (2011).

Klotzbach, P. J. et al. The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season: An above-normal season despite strong El Niño conditions. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 105, E1644–E1661 (2024).

National Hurricane Center. Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Beryl (AL022024). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL022024_Beryl.pdf (2024).

Wilcox, C. & Jacobs, P. Hurricane-battered researchers assess damage. Science 386, 367 (2024).

Beven, J. L. et al. Atlantic hurricane season of 2005. Monthly Weather Rev. 136, 1109–1173 (2008).

Yang, Y. et al. Greenhouse warming intensifies north tropical Atlantic climate variability. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg9690 (2021).

Chiang, J. C. & Vimont, D. J. Analogous Pacific and Atlantic meridional modes of tropical atmosphere–ocean variability. J. Clim. 17, 4143–4158 (2004).

North, G. R., Bell, T. L., Cahalan, R. F. & Moeng, F. J. Sampling errors in the estimation of empirical orthogonal functions. Monthly Weather Rev. 110, 699–706 (1982).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geoscientific Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Xie, S. P. & Philander, S. G. H. A coupled ocean-atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus A 46, 340–350 (1994).

Oettli, P., Morioka, Y. & Yamagata, T. A regional climate mode discovered in the North Atlantic: Dakar Niño/Niña. Sci. Rep. 6, 18782 (2016).

Xie, S.-P. A dynamic ocean–atmosphere model of the tropical Atlantic decadal variability. J. Clim. 12, 64–70 (1999).

Du, Y., Xie, S.-P., Huang, G. & Hu, K. Role of air–sea interaction in the long persistence of El Niño–induced north Indian Ocean warming. J. Clim. 22, 2023–2038 (2009).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Eastern Pacific ITCZ dipole and ENSO diversity. J. Clim. 31, 4449–4462 (2018).

Kaplan, J. & DeMaria, M. Large-scale characteristics of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic basin. Weather Forecast. 18, 1093–1108 (2003).

Latif, M., Keenlyside, N. & Bader, J. Tropical sea surface temperature, vertical wind shear, and hurricane development. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L01710 (2007).

Murakami, H., Levin, E., Delworth, T., Gudgel, R. & Hsu, P.-C. Dominant effect of relative tropical Atlantic warming on major hurricane occurrence. Science 362, 794–799 (2018).

Ham, Y.-G., Kug, J.-S., Park, J.-Y. & Jin, F.-F. Sea surface temperature in the north tropical Atlantic as a trigger for El Niño/Southern Oscillation events. Nat. Geosci. 6, 112–116 (2013).

Ham, Y. G., Kug, J. S. & Park, J. Y. Two distinct roles of Atlantic SSTs in ENSO variability: North tropical Atlantic SST and Atlantic Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4012–4017 (2013).

Pielke, R. A. Jr & Landsea, C. N. La nina, el nino, and atlantic hurricane damages in the united states. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 80, 2027–2034 (1999).

Klotzbach, P. J. El Niño–Southern Oscillation’s impact on Atlantic basin hurricanes and US landfalls. J. Clim. 24, 1252–1263 (2011).

Patricola, C. M., Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. The impact of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Atlantic meridional mode on seasonal Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. J. Clim. 27, 5311–5328 (2014).

Wang, C. & Lee, S. K. Atlantic warm pool, Caribbean low-level jet, and their potential impact on Atlantic hurricanes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L02703 (2007).

Bell, G. D. & Chelliah, M. Leading tropical modes associated with interannual and multidecadal fluctuations in North Atlantic hurricane activity. J. Clim. 19, 590–612 (2006).

Park, J.-H. & Li, T. Interdecadal modulation of El Niño–tropical North Atlantic teleconnection by the Atlantic multi-decadal oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 52, 5345–5360 (2019).

Park, J.-H. et al. Two regimes of inter-basin interactions between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans on interannual timescales. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 13 (2023).

Martín-Rey, M., Polo, I., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B., Losada, T. & Lazar, A. Is there evidence of changes in tropical Atlantic variability modes under AMO phases in the observational record?. J. Clim. 31, 515–536 (2018).

Knight, J. R., Folland, C. K. & Scaife, A. A. Climate impacts of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L17706 (2006).

Zhang, R. et al. A review of the role of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in Atlantic multidecadal variability and associated climate impacts. Rev. Geophysics 57, 316–375 (2019).

Jia, F., Cai, W., Gan, B., Wu, L. & Di Lorenzo, E. Enhanced North pacific impact on El Niño/southern oscillation under greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 840–847 (2021).

Yu, J.-Y. et al. Linking emergence of the central Pacific El Niño to the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. J. Clim. 28, 651–662 (2015).

Chen, S. et al. Enhanced impact of the Aleutian Low on increasing the Central Pacific ENSO in recent decades. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 29 (2023).

Taschetto, A. S., Rodrigues, R. R., Meehl, G. A., McGregor, S. & England, M. H. How sensitive are the Pacific–tropical North Atlantic teleconnections to the position and intensity of El Niño-related warming?. Clim. Dyn. 46, 1841–1860 (2016).

Amaya, D. J. & Foltz, G. R. Impacts of canonical and Modoki El Niño on tropical Atlantic SST. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 119, 777–789 (2014).

Reynolds, R. W., Rayner, N. A., Smith, T. M., Stokes, D. C. & Wang, W. An improved in situ and satellite SST analysis for climate. J. Clim. 15, 1609–1625 (2002).

Rayner, N. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

Huang, B. et al. NOAA extended reconstructed sea surface temperature (ERSST), version 5. NOAA Natl. Cent. Environ. Inf. 30, 25 (2017).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Renew. Energ. 1_146-141_194 (2018).

Behringer, D. W., Ji, M. & Leetmaa, A. An improved coupled model for ENSO prediction and implications for ocean initialization. Part I: The ocean data assimilation system. Monthly Weather Rev. 126, 1013–1021 (1998).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The international best track archive for climate stewardship (IBTrACS) unifying tropical cyclone data. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Lorenz, E. N. Empirical orthogonal functions and statistical weather prediction. 1 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Meteorology Cambridge, 1956).

Takahashi, K., Montecinos, A., Goubanova, K. & Dewitte, B. ENSO regimes: Reinterpreting the canonical and Modoki El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L10704 (2011).

Cai, W. et al. Increased variability of eastern Pacific El Niño under greenhouse warming. Nature 564, 201–206 (2018).

Yang, K. et al. Oceanic processes in ocean temperature products key to a realistic presentation of positive Indian Ocean Dipole nonlinearity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089396 (2020).

Cai, W. et al. Opposite response of strong and moderate positive Indian Ocean Dipole to global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 27–32 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Emergence of the central Atlantic Niño. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi5507 (2023).

Enfield, D. B., Mestas-Nuñez, A. M., Mayer, D. A. & Cid-Serrano, L. How ubiquitous is the dipole relationship in tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures?. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 104, 7841–7848 (1999).

Song, K., Zhao, J., Zhan, R., Tao, L. & Chen, L. Confidence and uncertainty in simulating tropical cyclone long-term variability using the CMIP6-HighResMIP. J. Clim. 35, 6431–6451 (2022).

Chen, G. & Huang, R. Interannual variations in mixed Rossby–gravity waves and their impacts on tropical cyclogenesis over the western North Pacific. J. Clim. 22, 535–549 (2009).

Feng, X., Yang, G.-Y., Hodges, K. I. & Methven, J. Equatorial waves as useful precursors to tropical cyclone occurrence and intensification. Nat. Commun. 14, 511 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Lapsed El Niño impact on Atlantic and Northwest Pacific tropical cyclone activity in 2023. Nat. Commun. 15, 6706 (2024).

Bell, G. D. et al. Climate assessment for 1999. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 81, S1–S50 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42376022). Y.Z. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2411039), Laoshan Laboratory (LSKJ202202602), and the project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M703034). Y.L. is supported in part by a National Research Council Research Associateship Program postdoc at NOAA/PMEL. Z.L. is supported by the Hainan Provincial Joint Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (2021JJLH0056). H.C.N was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant 456490637. This is PMEL contribution no. 5719.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., M.J.M., and Y.Z. codesigned this study. Y.L. wrote the initial manuscript in discussion with M.J.M., W.C, and Y.Z. Y.L. performed analyses and generated all figures. J.Z. calculated the hurricane metrics. Y.L., M.J.M., W.C, Y.Z., J.Z., H.C.N. contributed to discussion of associated dynamics. Y.L., M.J.M., W.C, Y.Z., J.Z., H.C.N., X.L., Z.L. and J.C.Y. contributed to interpreting the results and improving the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Chris Landsea and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Chao He and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., McPhaden, M.J., Cai, W. et al. Basin-wide and coastal modes of north tropical Atlantic variability have distinct impacts on hurricanes. Commun Earth Environ 6, 549 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02529-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02529-1