Abstract

Tropical cyclones can cause severe damage to coastal communities and the marine industry. However, trends in their intensity remain uncertain due to observational challenges, especially for the more frequent weak tropical cyclones, defined as tropical storms to category-1 tropical cyclones on the Saffir–Simpson scale. Here we develop an inversion model using surface drifter observations to estimate sea-surface wind speed, aiming to reassess the long-term global trend in the intensity of weak tropical cyclones from 1993 to 2022. Our results indicate that the global intensification of weak tropical cyclones has been insignificant, with only a modest upward trend of about 3.4 cm s−1 decade−1. Furthermore, we found that weak tropical cyclones have intensified only in the Southern Hemisphere, rather than across all ocean basins. The present work suggests that global warming is probably having only a limited impact on the evolution of weak tropical cyclones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are among the most destructive of natural disasters and are of great interest to the broad oceanic and atmospheric scientific community1,2,3,4,5,6. Over the past few decades, climate change has been linked to an increase in both the frequency7,8 and intensity9,10,11 of TCs. However, the challenges associated with observing these extreme weather phenomena have fueled continued debates on this trend12,13,14,15. Weak TCs, characterized by maximum sustained wind speeds of 17 to 42 m s−1 at the time of measurement, are the most common16,17. They play a crucial role in TC landfall forecasting and the prevention of socioeconomic damage18,19. Unfortunately, accurately determining the intensity of TCs remains a challenge. Conventionally, the Dvorak technique20,21, which estimates TC intensity based on cloud patterns and infrared cloud-top temperatures derived from satellite imagery, is considered the most effective method. In operational settings, the Dvorak technique involves estimating a final T number (FT) from cloud features, converting it to a current intensity number (CI) using empirical rules, and then mapping the CI to maximum sustained wind speed based on agency-specific conversion tables. Due to the subjectiveness of the FT estimates, CI assignment and differences in the conversion table in use, the resulting intensity estimates can differ significantly, even when based on identical satellite inputs. Moreover, the accuracy of the Dvorak technique is inevitably affected by various factors, including rainfall, clouds, breaking waves, and sea spray. These factors can lead to non-negligible errors in TC intensity estimates22, highlighting the need for continued research and improvement in this area.

Ocean observations with high temporal and spatial accuracy from a large volume of surface drifter are less affected by complex atmospheric conditions, which allows for a more objective and consistent estimation of TC intensity changes over time. Recently, Wang et al.23 have proposed an intriguing approach to estimating TC intensity based on ocean current data. They derived sea-surface wind speeds (SSWSs) from drifter-measured ocean currents using a simplified formula based on Ekman theory24 \({U}_{10}=\frac{\sqrt{\sin \left|\varphi \right|}}{0.0127}{V}_{0}\,(\,\left|\varphi \right|\ge 10)\), where \({U}_{10}\) represents the wind speed at a height of 10 m (i.e., the SSWS), \(\varphi\) denotes latitude, and \({V}_{0}\) is the Ekman current speed at the ocean surface derived from the drifter current measurements. Their study found a robust global upward trend of 1.8 m s−1 decade−1 in the intensity of weak TCs between 1991 and 2020. However, because the majority of the drifters (97.72%) measured the ocean currents at drogue depths of 10–15 m, Wang et al.23 neglected the potential impact of the exponential term in the original Ekman theory formula, that could have led to significant errors in their calculations of the SSWS (see Supplementary Discussion 1). Additionally, the Ekman theory is not applicable to regions between 10°S and 10°N, which hinders a comprehensive analysis of the intensity trends of weak TCs at the GLOBAL scale.

Results and discussion

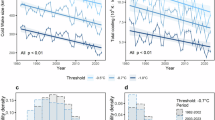

Here, we apply a data-driven model (see “Methods”) to estimate weak-TC intensity over the global ocean. The model derives SSWSs directly from the near-surface currents measured by drifters under weak TCs (Fig. 1a). The main steps in the process are as follows. First, the model was trained using a large amount of wind-current data pairs observed by 37 tropical moored buoys. Following the Eulerian observation principle, the buoys are fixed in position and capable of collecting comprehensive measurements at a single location, including wind speed (measured at 4 m above the sea surface), ocean currents, sea surface temperature (SST), rainfall, heat fluxes, and so on. The observed 4 m wind speeds were converted to standard 10 m wind speeds (i.e., the SSWS) using the COARE 3.5 algorithm25,26. Additionally, given the significant thermal response of the ocean to TCs27,28, we incorporated the sea surface temperature (SST) as an another input parameter to enhance effectiveness of the model inversion (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Secondly, to evaluate the performance of the model, we compared the SSWSs inverted by the model with those derived using the Ekman theory, employing randomly selected buoy-observed currents and referencing the corresponding buoy-observed 10 m wind speeds. The root mean square error (RMSE) of the inverted SSWSs was 1.56 m s−¹ on average, obtaining a 71.68% decrease compared to the RMSE of 5.51 m s−¹ derived using the Ekman-theory-based approach as Wang et al.23. Comparisons of the RMSE in three typical basins are shown in Fig. 1b–d. Therefore, we expected our model to be more effective with respect to analysing the trends in weak-TC intensity. We then applied our fully-trained model to the globally distributed drifter data collected under weak TCs, and inverted the SSWSs from the drifter current and SST measurements. Drifters follow the Lagrangian observation principle, drifting with ocean currents and recording environmental variables along their paths. Due to the widespread deployment of global drifters, a certain number of drifters are always located within the proximity of each weak TC. Consequently, we were able to obtain inverted SSWSs for all of the weak TCs that developed during the study period. Finally, these inverted SSWSs were spatially averaged to represent the intensity of weak TCs.

a Process for estimating the intensity of weak TCs using the SSWS inversion model. Step 1: Convert 4-m height wind speed (U4) to 10-m height wind speed (i.e., U10 = SSWS) using the COARE 3.5 algorithm. All input data for the COARE 3.5 were obtained from 37 tropical moored buoy observations. Step 2: Train the SSWS inversion model. The training process involves feeding the near-surface current speed (V0), sea surface temperature (SST), and U10 data from the buoy observations into the model. The model is expected to develop a robust understanding of how V0 and SST influence U10. Step 3: Apply the fully-trained SSWS inversion model to drifter observations. A substantial volume of drifter-observed V0 and SST data from the region near each weak TC are fed into the model to estimate the corresponding U10 under these weak TCs. Step 4: Obtain spatially averaged inverted SSWSs to represent the intensity of weak TCs. This is achieved by calculating the average of n U10 values, where n represents the number of data points input into the model. b–d Comparison of the SSWS inversion model and the Ekman method. The blue lines and dots represent the inversion results from our model, and the red lines and dots are from the Ekman method. Lines show linear regression based on buoy-observed U10 and inverted U10 from the corresponding buoy-observed currents (dots) under weak TCs, with the RMSE indicated in the upper right. Data in (b) includes 114 observations from the Research Moored Array for African-Asian-Australian Monsoon Analysis and Prediction (RAMA), c 217 observations from the Tropical Atmosphere Ocean/Triangle Trans-Ocean Buoy Network (TAO/TRITON), and d 115 observations from the Prediction and Research Moored Array in the Tropical Atlantic (PIRATA).

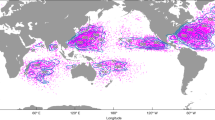

Weak TCs account for a substantial proportion of total TC occurrences (Supplementary Table 3), particularly in the Indian Ocean (62.23%) and Northeast Pacific (57.71%). They are also associated with a significantly larger number of available drifter observations compared to strong TCs (categories 3–5). This higher data availability enhances the statistical robustness of long-term trend analysis. Figure 2 shows the global distributions of weak TC occurrences, and the corresponding drifter observations that were located within seven radii of the maximum sustained wind speed (\({R}_{\max }\)) of these weak TCs, spanning the period from 1993 to 2022. The weak TCs and drifter observations have a similar spatial distribution, thereby ensuring a sufficient amount of drifter data to accurately reconstruct the intensity of the weak TCs. As shown in Supplementary Table 4, the total number of drifter records under weak TCs in each ocean basin was as follows: 50,834 in the North Atlantic Ocean (NA), 23,089 in the Northeast Pacific Ocean (NEP), 29,240 in the Northwest Pacific Ocean (NWP), 2594 in the North Indian Ocean (NI), 14,256 in the South Indian Ocean (SI), and 8947 in the South Pacific Ocean (SP). Evidently, all ocean basins have been adequately sampled under weak-TC conditions. Moreover, we incorporated 5538 weak-TC records (12.23% of the total) and 13,373 drifter observations (10.37% of the total) that were located within the latitude range of 10°S to 10°N. These data are essential if we wish to conduct a global analysis. These data are essential if we wish to conduct a global analysis.

Global distributions of a weak TC occurrences and b drifter observations that located within the vicinity of these weak TCs, both on 2° × 2° (latitude × longitude) grids for the period 1993–2022. The total number of weak TCs recorded was 45,299, and 5538 (12.23% of the total) were observed between 10°S and 10°N (indicated by the regions between red lines). The total number of drifter records was 128,960, with 13,373 (10.37% of the total) under weak TCs.

Figure 3 illustrates the derived trends in weak-TC intensity at the global and basin scales, covering the period from 1993 to 2022. Overall, the global trend in weak-TC intensity is not statistically significant, as the Mann-Kendall test (see “Methods”) yields a P value exceeding 0.05. Despite this, a slight upward trend of 0.34 cm s−1 year−1 is observed. In fact, the trends in weak-TC intensity appear to be insignificant across all ocean basins, with the exception of the NI, as indicated in Table 1. This upward trend is much smaller than the 0.11 m s−¹ year−¹ increase estimated using the Ekman-theory-based method (see Supplementary Discussion 2). We also obtained consistently similar results when calculating the trends in weak-TC intensity using the SSWS model and drifter measurements from within one to six \({R}_{\max }\) of the TC centres. However, none of the model-inverted trends in weak-TC intensity were statistically significant (Table 2). In addition, despite a negligible global-averaged upward trend in the intensity of weak TCs, the weak TCs in the Northern Hemisphere (i.e., NA, NEP, NWP, and NI) weakened, implying that the global upward trend is driven primarily by weak TCs in the Southern Hemisphere (i.e., SP and SI).

Trends in both current and wind speeds are characterized by the slopes of the fitted lines (denoted as “s”), along with their 95% confidence intervals. The statistical significance of these trends was assessed using the P value (denoted as “p”) obtained from an F-test. The number of weak TCs considered in this analysis for each ocean basin were as follows: 4874 for the NA (a), 5682 for the NEP (b), 6623 for the NWP (c), 1032 for the NI (d), 4654 for the SI (e), and 2579 for the SP (f). The global ocean analysis integrates data from all of these basins (g).

In contrast to Wang et al.23, we have demonstrated that regions within the low-latitude range of 10°S to 10°N should be included when analysing trends in weak-TC intensity (Fig. 4). When drifter data from these low-latitude regions are excluded from the analysis, the estimated global trend in weak TC intensity, inverted from ocean current measurements, decreases from 0.34 cm s−1 to 0.22 cm s−1 year−1. This finding underscores the necessity of including data from these low-latitude regions when assessing the global trend in weak-TC intensity. Moreover, the statistically significant downward trend in the intensity of weak TCs in the NI, as inverted from the ocean current speed, is reduced when drifter data from the low-latitude regions between 10°S and 10°N are excluded; i.e., it decreases from –4.02 to –2.75 cm s–1 year–1. This further emphasizes the critical role of including data from these low-latitude regions if we wish to accurately capture the trends in weak-TC intensity, particularly in specific regions such as NI.

Trends in both current and wind speeds are characterized by the slopes of the fitted lines (denoted as “s”), along with their 95% confidence intervals. The statistical significance of these trends was assessed using the P value (denoted as “p”) obtained from an F-test. The proportion of drifter records located in regions with \(\left|\varphi \right|\ge {10}^{\circ }\) to the total number of global drifter records under weak TCs is also presented for each ocean basin, as shown in a NA, b NEP, c NWP, d NI, e SI, and f SP. A global ocean analysis that integrates data from all these basins is shown in (g).

On the other hand, an upward trend of approximately 0.17 cm s−1 year−1 has been observed in global near-surface current speeds under weak TCs over the period 1993–2022, as illustrated in Fig. 3g. However, this trend is much weaker than that reported by Wang et al.23, who indicated a trend of about 0.40 cm s−1 year−1 for the period 1991–2020. This discrepancy in the upward trends in global near-surface current speeds under weak TCs can be attributed to the additional drifter observations used in this study. Compared to the dataset used by Wang et al.23 (1991–2020), which included 104,284 drifter observations, our study utilizes 128,960 observations from 1993 to 2022, reflecting a 23.66% increase in data volume. This increase primarily stems from the inclusion of low-latitude observations within the 10°S to 10°N band, which were previously omitted, and from the additional observations recorded during 2021–2022. Specifically, drifters within the 10°S to 10°N band contributed 11,191 observations between 1993 and 2020, with a further 2182 observations added from 2021–2022. Moreover, the number of observations during 2021–2022 (17,870) greatly exceeds the 4998 recorded in 1991–1992 (Fig. 5). These additions provide a more comprehensive dataset, offering improved spatial and temporal coverage, especially in previously underrepresented regions. Overall, the incorporation of additional 13,373 drifter records from the 10°S to 10°N latitude band (Supplementary Table 5) significantly enhances the global assessment of trends related to weak TCs, allowing for a more refined understanding of the dynamics and predictions of weak TCs.

Conclusion

In this study, we have demonstrated that the intensification of weak TCs across the global oceans over recent decades, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, has been insignificant. This conclusion contrasts with previous theoretical predictions29,30 and numerical modelings31, which suggest that TCs intensify as the ocean warms. However, our analysis indicates that global warming over the past three decades may not have had a noticeable impact on the evolution of weak TCs. It is important to note that the drifter-based approach inherently carries certain limitations, including potential effects from wave-induced motions, variable distances between drifter observations and TC centers, and the influence of background geostrophic currents. While these uncertainties are partially addressed through rigorous data preprocessing and robust model validation, the absence of complementary measurements, such as wave parameters or sea surface height, inevitably constrains the precision of SSWS inversion. Sustained endeavors to broaden observational datasets and refine inversion models are of paramount importance. These efforts will enable us to attain a more profound comprehension of tropical cyclone dynamics and conduct more accurate assessments of how climate change may potentially influence their development and progression.

Methods

SSWS inversion model

A total of 832,435 simultaneous oceanic and atmospheric observations were collected from 37 tropical moored buoys to develop our SSWS inversion model. These buoys were deployed across three ocean basins: 12 from the RAMA in the Indian Ocean, 12 from the TAO/TRITON in the Pacific Ocean, and 13 from the PIRATA (Fig. 6). Each observation includes the buoy location (longitude and latitude), 4-m height wind speed (denoted as \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}4{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)), near-surface current speed, and various additional environmental parameters. The 10-m height wind speed (denoted as \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}10{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) was derived from the \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}4{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) data using the COARE 3.5 algorithm, which requires various environmental inputs to calculate the wind speed at different heights. As these inputs are not uniformly available across all buoy deployments, only the aforementioned 37 moorings with sufficiently complete records were included to ensure reliable COARE-based conversion. The comparison between the \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}10{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}4{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) values is illustrated in Fig. 7.

Subsequently, we developed an inversion model to determine the relationship between \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}10{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) and near-surface current speed, using the extensive dataset obtained from these tropical moored buoys. The model was formulated as follows:

Here, \({{{{\rm{Lon}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{Lat}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}}\) represent the longitude and latitude of the buoy, respectively. The \({{{{\boldsymbol{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}}\) function can indeed be implemented using any data-driven regression approach. In the present study, we have employed seven distinct regression techniques to implement the \({{{{\boldsymbol{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}}\) function, namely: linear regression32, decision tree (DT)33, random forest (RF)34, extreme gradient boosting35 (XGBoost), light gradient boosting machine36 (lightGBM), support vector regression37 (SVR), and multilayer perceptron38 (MLP).

The parameter configurations for all the regression methods employed in the SSWS model, as well as for the Ekman method, are detailed in Table 3. As for the data used in the model, 80% of the observations at each buoy were randomly selected as the training set and the remaining 20% were used as the test set. The training results obtained from the various regression approaches are shown in Table 4 and indicate that the data-driven model with each regression approach outperforms the Ekman method. The model with the RF regression approach stands out as the optimal choice, achieving a significant reduction in both the RMSE (by up to 53.90%, from 4.49 to 2.07 m s−1) and the mean absolute error (MAE; by up to 55.03%, from 3.58 to 1.61 m s−1). The inversion errors will increase when the SST information is excluded. This underscores the pivotal role of incorporating thermal effects in the accurate modelling of the complex relationship between near-surface currents and sea surface winds.

Consequently, we selected the best-trained RF model, denoted as \({{{{\boldsymbol{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{buoy}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{* }}}}}\), as our definitive SSWS inversion model. The weighting factors of input variables, namely, the longitude, latitude, zonal and meridional components of current, and SST, were 0.0417, 0.0448, 0.2290, 0.2241, and 0.4604, respectively.

Ultimately, the SSWSs inverted from the near-surface current speeds observed by drifters within the vicinity of a weak TC were spatially averaged to serve as an alternative measure to assess the intensity of the weak TCs, \(I\). This was formulated as follows:

Here, \(n\) represents the number of drifters located within seven \({R}_{\max }\) of each weak TC, and \({{{{\rm{Wind}}}}}_{{{{\rm{drifter}}}}10{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) is the SSWSs inverted from the drifter-observed near-surface current speeds.

Mann-Kendall test

The Mann-Kendall test39,40 is a non-parametric statistical method designed to detect trends in time series data. To determine the trends in the weak-TC intensity, we carried out the Mann-Kendall test as follows.

Step 1: Given the input sequence \({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}=\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2,}\ldots ,{x}_{n}\}\), we compare each pair of data points of the sequence and calculate an \(S\) statistic, which represents the cumulative count of increases or decreases within the sequence. The process can be described as follows:

Step 2: We then standardize the \(S\) statistic to obtain the \(Z\) statistic, which is used to ascertain the significance of the trend. The standardization process is as follows:

Step 3: To assess the significance of the trend, we compare the \(Z\) statistic against critical values derived from the standard normal distribution. The comparison process is as follows:

Here, \(a\) is set to 0.05, indicating a confidence level of 0.95. The percent point function (\({{{\rm{ppf}}}}\)) is used to determine the critical values.

Step 4: The P value is calculated as follows:

where \({{{\rm{cdf}}}}\) denotes the cumulative distribution function. The P value represents the probability obtained from the test, reflecting the likelihood of observing the trend in the data under the null hypothesis (i.e., no underlying trend). If the P value exceeds 0.05, we conclude that the sequence fails the Mann-Kendall test, indicating that it does not exhibit a significant trend.

Data availability

The hourly current and wind data from the TAO/TRITON, RAMA and PIRATA buoy arrays were downloaded from https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/drupal/disdel/. The 6-hourly positions and upper-ocean current velocities from the drifters were obtained from https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/phod/gdp/interpolated/data/all.php. TC occurrence, with a 6-h temporal resolution, was acquired from the best track data of the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (https://www.metoc.navy.mil/jtwc/jtwc.html?best-tracks) for the Western Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean and the Southern Hemisphere, and from the National Hurricane Center and Central Pacific Hurricane Center (https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/) for the Atlantic and Northeast and Central Pacific Oceans. The source data used to generate the figures in this study are available at Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/1457638441.

Code availability

The code and scripts used to analyse the data and to produce the plots presented in this paper are accessible via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/1457638441. The original versions of the NOAA COARE 3.5 algorithm are available at https://github.com/NOAA-PSL/COARE-algorithm.

References

Knutson, T. R. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change. Nat. Geosci. 3, 157–163 (2010).

Peduzzi, P. et al. Global trends in tropical cyclone risk. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 289–294 (2012).

Mendelsohn, R., Emanuel, K., Chonabayashi, S. & Bakkensen, L. The impact of climate change on global tropical cyclone damage. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 205–209 (2012).

Moon, I.-J., Kim, S.-H. & Wang, C. El Niño and intense tropical cyclones. Nature 526, E4–E5 (2015).

Xi, D., Lin, N. & Gori, A. Increasing sequential tropical cyclone hazards along the US East and Gulf coasts. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 258–265 (2023).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent migration of tropical cyclones toward coasts. Science 371, 514–517 (2021).

Yoshida, K., Sugi, M., Mizuta, R., Murakami, H. & Ishii, M. Future changes in tropical cyclone activity in high-resolution large-ensemble simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9910–9917 (2017).

Webster, P. J., Holland, G. J., Curry, J. A. & Chang, H.-R. Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. Science 309, 1844–1846 (2005).

Kang, N.-Y. & Elsner, J. B. Trade-off between intensity and frequency of global tropical cyclones. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 661–664 (2015).

Elsner, J. B., Kossin, J. P. & Jagger, T. H. The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones. Nature 455, 92–95 (2008).

Bender, M. A. et al. Modeled impact of anthropogenic warming on the frequency of intense Atlantic Hurricanes. Science 327, 454–458 (2010).

Lin, I. I. & Chan, J. C. Recent decrease in typhoon destructive potential and global warming implications. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–8 (2015).

Pielke, R. A. Jr Are there trends in hurricane destruction?. Nature 438, E11–E11 (2005).

Sobel, A. H. et al. Human influence on tropical cyclone intensity. Science 353, 242–246 (2016).

Zhao, H. et al. Decreasing global tropical cyclone frequency in CMIP6 historical simulations. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl2142 (2024).

Emanuel, K. A. The dependence of hurricane intensity on climate. Nature 326, 483–485 (1987).

Klotzbach, P. J. et al. Trends in global tropical cyclone activity: 1990–2021. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL095774 (2022).

Feng, X. & Shu, S. How do weak tropical cyclones produce heavy rainfall when making landfall over China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 11–830 (2018).

Zhan, R. & Wang, Y. Weak tropical cyclones dominate the poleward migration of the annual mean location of lifetime maximum intensity of northwest Pacific tropical cyclones since 1980. J. Clim. 30, 6873–6882 (2017).

Dvorak, V. F. Tropical cyclone intensity analysis and forecasting from satellite imagery. Mon. Weather Rev. 103, 420–430 (1975).

Dvorak, V. F. Tropical cyclone intensity analysis using satellite data. NOAA Tech. Rep. NESDIS 11, 47 (1984).

Knaff, J. A., Brown, D. P., Courtney, J., Gallina, G. M. & Beven, J. L. An evaluation of Dvorak technique–based tropical cyclone intensity estimates. Weather Forecast 25, 1362–1379 (2010).

Wang, G., Wu, L., Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Ocean currents show global intensification of weak tropical cyclones. Nature 611, 496–500 (2022).

Stewart, R. H. Introduction to Physical Oceanography (Robert H. Stewart, 2008).

Edson, J. B. et al. On the exchange of momentum over the open ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43, 1589–1610 (2013).

Sauvage, C., Seo, H., Clayson, C. A. & Edson, J. B. Improving wave-based air-sea momentum flux parameterization in mixed seas. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 128, e2022JC019277 (2023).

Vecchi, G. A. & Soden, B. J. Effect of remote sea surface temperature change on tropical cyclone potential intensity. Nature 450, 1066–1070 (2007).

Sriver, R. L. & Huber, M. Observational evidence for an ocean heat pump induced by tropical cyclones. Nature 447, 577–580 (2007).

Emanuel, K. The theory of hurricanes. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 23, 179–196 (1991).

Holland, G. J. The maximum potential intensity of tropical cyclones. J. Atmos. Sci. 54, 2519–2541 (1997).

Knutson, T. R. & Tuleya, R. E. Impact of CO2-induced warming on simulated hurricane intensity and precipitation: Sensitivity to the choice of climate model and convective parameterization. J. Clim. 17, 3477–3495 (2004).

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A. & Vining, G. G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

Breiman, L. Classification and Regression Trees (Routledge, 2017).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (ACM, 2016).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 3146–3154 (2017).

Basak, D., Pal, S. & Patranabis, D. C. Support vector regression. Neural Inf. Process. 11, 203–224 (2007).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Mann, H. B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 13, 245–259 (1945).

Kendall, M. G. & Gibbons, J. D. Rank Correlation Methods (Oxford University Press, 1990).

Tang, H. Codes and source data for “Are there trends in weak tropical cyclones in recent 30 years?”. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14576384 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42274067) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQN25D060005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.F.M. designed the study. H.T. processed the data and wrote the manuscript under instruction of D.F.M. and J.M.L. L.W.W. performed the analysis and contributed to improving the manuscript. J.M.L. initiated the idea, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Weiqing Han and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, D., Tang, H., Wu, L. et al. Limited global intensification of weak tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Commun Earth Environ 6, 563 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02561-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02561-1

This article is cited by

-

Assessment of Coastal Socio-economic Exposure under the Impact of Future Typhoons Landing in China

Chinese Geographical Science (2026)