Abstract

Irrigation exerts a strong influence on carbon dynamics in agroecosystems. However, global patterns of soil organic carbon (SOC) and soil inorganic carbon (SIC) responses to irrigation remain insufficiently characterized. Here, we synthesized 223,593 observations to derive 2217 representative soil profile measurements and estimated the differential effects of irrigation on SOC and SIC. Our results show that soil carbon responses to irrigation vary with soil depth and are related to the amount of irrigation water applied. Specifically, SOC and SIC of cropland increased by 127% and 57.09%, respectively, under 200–300 mm irrigation compared to the reference study sites. In global upscaling experiments, we mapped the vulnerability distribution of SOC and SIC losses in irrigated cropland by applying a meta-forest model. We found that 54.58% of stable cropland areas were projected to experience SOC losses, and 60.22% were projected to experience SIC losses, under long-term continuous irrigation, with SIC at greater global risk. These findings highlight the need for strategic consideration of carbon sequestration potential in irrigation management to support climate adaptation efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Irrigation is a key practice for regulating soil moisture and boosting crop yields1. Irrigation has expanded rapidly worldwide since the 20th century, which has led to significant impacts on soil carbon pools and climate change2,3,4. Despite increasing research on the relationship between irrigation and soil carbon5,6,7, the global distribution and controlling factors of soil carbon responses to irrigation remain largely unexplored8. In view of the high heterogeneity in soil carbon and the complexity of the environmental impacts of irrigation7,9, a quantitative analysis of irrigation’s impact on soil carbon is needed to improve the knowledge of the soil carbon cycle and the feasibility of irrigation as a climate adaptation strategy10,11,12.

Soil represents the largest terrestrial carbon pool, including both organic soil organic carbon (SOC) and soil inorganic carbon (SIC)13. Most irrigation-soil carbon studies have focused primarily on SOC4,14,15, and the distribution of SOC is well-documented16,17. Presently, there are mixed findings regarding the effect of irrigation on SOC and SIC accumulation4. On the one hand, some studies indicate that irrigation enhances SOC storage by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting crop growth18,19,20, while others find that irrigation effects on SOC are minimal or even negative21, likely due to flood irrigation in monsoon wet areas could lead to anaerobic conditions, increasing methane emissions22,23. Particularly on sites with limited organic matter inputs, increased microbial activity as a result of pulse wetting may result in losses of SOC24. On the other hand, Dong et al. observed that long-term saline irrigation decreased SIC content in the 0–20 cm soil layer in the northeast of North China Plain25. A seven-year study in Navarre, northern Spain, found that while irrigation rapidly altered carbonate types, it did not affect total SIC content26. The discrepancies in these findings are likely attributable to the inconsistency of research scales, the high heterogeneity of irrigation water quality and amount, and the complex environment of croplands. Furthermore, most studies frequently overlooked the SIC as it was conventionally viewed as a relatively stable carbon pool that was not typically included in the carbon budget27,28. It is well known that irrigation is generally implemented in arid and semi-arid regions, which are high in SIC and low in SOC. With the worldwide agricultural intensification and anthropogenic reactive N addition, it would indirectly exacerbate SIC losses29,30, and most of the lost SIC was converted to CO227, indicating SIC is not as stable as previously thought. Research by Huang et al. estimated that global SIC stocks could decrease by 23 billion tons over the next 30 years31. Huang’s research provides an opportunity to quantify the effects of irrigation on SIC, especially SIC change in arid and semi-arid regions, and its threat to climate change10,12.

Irrigation is a complex driver of soil environmental changes, with numerous nonlinear feedbacks and interactions7,10. For example, intensive irrigation in India has been demonstrated to decrease surface temperature32,33, which, in turn, enhances carbon uptake in croplands34,35. Additionally, a recent study suggested that the temperature sensitivity of SIC dissolution increases with increasing natural aridity and that this process is regulated by pH and base cations36. Flood irrigation stores more SIC than under no-irrigation conditions in arid calcarine fields, which is influenced by soil chemistry as well as bacterial biomass5. Irrigation combined with fertilization is a common management practice. Several studies have proposed that Nitrogen fertilizer application and atmospheric nitrogen deposition would induce soil acidification, resulting in carbonate dissolution and SIC neutralization30,37. Therefore, synthesizing the interaction between irrigation and environmental factors is key to comprehending the soil carbon change in croplands. Moreover, most studies have focused on field and local scales19,22,38, which do not adequately consider the large-scale spatial heterogeneity and complexity of soil environments under global irrigation expansion27,39. The global distribution pattern of soil carbon impacted by irrigation can facilitate ongoing efforts to understand the global carbon cycle. The spatial information on soil carbon change can contribute to agricultural management, and local, national, and international carbon remediation and sequestration efforts.

Our objective was to systematically quantify the impacts of irrigation on SOC and SIC and to estimate the controlling factors underlying these effects. Therefore, we synthesized irrigation data40 (multiyear average water use, IWU), multi-source environmental datasets, and soil profile data based on the global database compiled by Huang et al.31. Additionally, we applied conditional screening to select 2212 soil profiles representing long-term irrigated and unchanged cropland. First, we investigated the effects of irrigation amount on SOC and SIC at different soil depths. Second, we explored the sensitivity of SOC and SIC to environmental factors in irrigated agricultural systems. Finally, we upscaled the geographic distribution of relative changes in SOC and SIC in irrigated cropland to identify high-loss risk areas for SOC and SIC.

Results

Soil depth-dependent response of SOC and SIC to different irrigation amounts

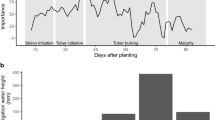

The meta-experiment strictly controlled environmental variables in irrigation-soil carbon analysis, ensuring similar environmental conditions between the control and experimental groups (“Methods” section). The results revealed that there were significant differences in the responses of SOC and SIC to irrigation amounts (Fig. 1). Compared non-irrigated cropland, the response of SOC to irrigation amounts \(({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{r})\) varied as follows: −11.83% under 0–50 mm, −4.39% under 50–100 mm, −31.09% under 100–200 mm, 127% under 200–300 mm, −40.32% under 300–400 mm and 74.09% under 400–500 mm. The response of SIC to irrigation amounts (\({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{r}\)) varied as follows: 60.20% under 0–50 mm, 83.94% under 50–100 mm, 44.74% under 100–200 mm, 73.82% under 200–300 mm, 57.09% under 300–400 mm, and −36.5% under 400–500 mm. Meanwhile, soil carbon response to irrigation varied by soil depth, the results revealed that \({{\mathrm{SIC}}}\) responses were greater than those of \({{\mathrm{SOC}}}\), especially in shallow (0–10 cm) and deep (200–500 cm) soils (Fig. 1). Specifically, in the 0–10 cm soil layer with irrigation (200–300 mm), the \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{r}\) was 3.35 (95% CI: 2.73–3.80), indicating that higher irrigation tended to have greater SIC compared to the reference study sites. In contrast, \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{r}\) was relatively low, suggesting that irrigation had a relatively weaker effect on SOC. As the soil depth increased, the values of \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{r}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{r}\) became more similar. In the 60–100 cm and 100–200 cm soil layers, the values of \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{r}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{r}\) were near zero to 0 or slightly positive, indicating that the effects of irrigation on SOC and SIC tend to be balanced. At the 200–500 cm soil depth, the irrigation amount had a positive effect on the SOC and SIC. Overall, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{r}\) was relatively small in the entire soil layer, and there was an environmental limitation on the promotion of SOC by the irrigation amount. Irrigation had some positive effects on SOC only at specific depths and under specific irrigation conditions (e.g., 10–30 cm, 30–60 cm, or 60–100 cm under 200–300 mm irrigation). This may be attributed to the fact that SIC can accumulate in the soil through long-term water infiltration and mineral dissolution41, whereas the accumulation of SOC is more dependent on processes such as surface organic matter input and microbial decomposition.

The average change in SOC and SIC (relative to unirrigated cropland in similar environmental conditions) for each soil layer depth under different irrigation amount treatments is shown. Depth increments are shown at the top of each panel. The solid triangles and circles with error lines indicate the average changes in SOC and SIC, respectively, and their respective 95% CIs. When the 95% CIs did not overlap with 0% (indicated by the vertical gray line), significant changes in SOC and SIC occurred over time. Data points may contain studies of different durations, where irrigation refers to the average irrigation water use over the years.

The differences between SOC and SIC responses to irrigation across natural conditions and management practices

Meta-regression analyses showed that SOC and SIC responses to irrigation (\({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\)) varied with natural conditions (temperature, precipitation, topography, and soil type) and management practices (crop type and irrigation water amount) (Fig. 2). Specifically, the average values of SOC and SIC in the surface soil of irrigated croplands decreased by 41.5% and 32.7%, respectively, compared with non-irrigated cropland. In terms of temperature, when the multiyear average ranged from 0 to 22 °C, both \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were negative. Furthermore, the negative impacts on SIC became increasingly pronounced with higher temperatures. Regarding precipitation, \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) was positive (0.31 with 95% CIs: 0.06–0.55) under humid condition, whereas both \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were negative in areas with other precipitation classes. Topographically, the value of \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) was 0.15 (95% CIs: −0.14 to 0.45) under high mountainous conditions, while it was negative in other topographic settings. Subgroup analysis by soil type revealed that the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) exhibited positive effects in ATF, GLa, NTh, ALh, and CMe, with \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) showing greater variability across soil types. These findings underscore the importance of site-specific factors (such as temperature, moisture, topography, soil properties, and crop management) in influencing soil carbon dynamics under irrigation implementation.

Environmental factors are on the left side of each panel. The solid triangles and circles with error lines indicate the average changes in SOC and SIC, respectively, and their respective 95% CIs. When the 95% CIs did not overlap with 0% (indicated by the vertical gray line), significant changes in SOC and SIC occurred over time. The number to the right of each panel indicates the total number of observations used to calculate the average. All data points are cropland without land use change. Temperature and precipitation are multi-year averages. The soil classification system used for soil types is FAO-90 (Note: GLa(Andic Gleysols), ATf(Fimic Anthrosols), NTh(Haplic Nitisols), LVa(Albic Luvsiols), ALh(Haplic Alisols), CMe(Eutric Cambisols), ACp(Plinthic Acrisols), CMg(Gleyic Cambisols), and GYk(Calcic Gypsisols)). Crop types come from the Global High Precision Crop Spatial Distribution (SPAM2020), and crop types other than rice, wheat, and corn are treated as others. Data points may contain studies of different durations, where IWU refers to the average irrigation water use over the years.

Effects of environmental factors on SIC and SOC in irrigated agricultural systems and their response curves

We further investigated the nonlinear effects of environmental factors on SOC and SIC in irrigated agricultural practices by screening data from the 0–30 cm soil profile with relevant environmental variables (pH, average temperature, precipitation, nitrogen fertilizer, phosphorus fertilizer, and elevation) (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). In the meta-experiments, there was significant residual heterogeneity in \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) (Response of SIC to irrigation amount relative to unirrigated) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) (Response of SIC to irrigation amount relative to unirrigated) with a random effect (\({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\): Qt = 97785.68, P < 0.0001; \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\): Qt = 79425.73, P < 0.0001).

In terms of soil properties, the stability of SIC is regulated by soil pH. The response of SOC and SIC to irrigation varies greatly across pH types. When irrigating in acidic soil (pH <6.5), the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.05 (95% CIs: −0.15 to 0.05) and −2.09 (95% CIs: −2.24 to −1.92), respectively. In neutral soil (6.5<pH <7.5), the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were 0.03 (95% CIs: −0.03 to 0.95) and −2.02 (95% CIs: −2.14 to −1.9), respectively. In alkaline soil (pH > 7.5), the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.54 (95% CI: −0.58 to −0.5) and 0.17 (95% CI: 0.13–0.22), respectively. The response curves revealed that SOC was more sensitive to irrigation in acidic soil than in alkaline soil. In acidic soil, SIC increased significantly with higher irrigation, while SOC showed a minimal response. In neutral soils, both SOC and SIC exhibited relatively complex nonlinear changes.

Regarding natural factors, temperature and precipitation are key determinants of agricultural productivity and can indicate the level of aridity. The results revealed that when irrigation was performed at 0–10 °C, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.42 (95% CI: −0.51 to 0.34) and 0.11 (95% CI: 0.003–0.23), respectively. At 10 to 22 °C, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) values were −0.35 (95% CI: −0.39 to −0.32) and −0.4 (95% CI: −0.46 to −0.34), respectively. At temperatures above 22 °C, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.34 (95% CI: −0.42 to −0.27) and −0.55 (95% CI: −0.64 to −0.36), respectively. In addition, data from non-irrigated areas below 0 °C showed the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) values were 0.79 (N = 34, 95% CI: 0.43–1.14) and −0.55 (N = 34, 95% CI: −1.32 to 0.2), respectively. The response curves revealed that SIC was more sensitive to irrigation at temperatures between 10–22 °C and 0–10 °C, particularly between 10–22 °C, where SIC fluctuated more with increasing irrigation. The sensitivity of SOC to irrigation was higher at temperatures above 22 °C.

When irrigation was implemented in arid areas, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were 0.17 (95% CI: 0.09–0.24) and −1.38 (95% CI: −1.53 to −1.22), respectively. In semi-arid areas, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.18 (95% CI: −0.24 to −0.13) and −1.06 (95% CI: −1.15 to −0.97), respectively. In optimal areas, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.60 (95% CI: −0.66 to −0.53) and 0.39 (95% CI: 0.31–0.47), respectively. In semi-humid areas, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −0.74 (95% CI: −0.80 to −0.67) and 0.30 (95% CI: 0.22–0.38), respectively. In humid areas, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) were −1.28 (95% CI: −1.45 to −1.11) and 0.18 (95% CI: 0.39–0.76), respectively. Compared with the average of SOC and SIC for non-irrigated areas, both \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) showed significant negative effects at lower irrigation levels, especially in arid and semi-arid regions. However, with increasing irrigation amount, the response curves of both SOC and SIC gradually levelled off, indicating that increasing irrigation amount could alleviate this negative effect. Notably, the change range of \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) is larger and more pronounced, especially under arid conditions. While the variation in the SOC is relatively small. These findings indicate that irrigation has a greater impact on SIC than on SOC, especially in water-scarce croplands.

In terms of farm management practices, previous studies have emphasized the close relationship between fertilization and SOC42. Both biotic and abiotic factors regulate the responses of SOC and SIC to irrigation, with fertilization playing a significant role. The results revealed that the application of nitrogen fertilizer (0–30 g/kg) had negative effects on \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) compared to non-irrigated areas. However, when nitrogen fertilizer exceeded 30 g/kg, the \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) was 0.56 (N = 22, 95% CI: −0.06 to 1.19). In the nitrogen fertilizer experiments, the response of SOC to irrigation was moderate, whereas the response of SIC to irrigation was relatively strong. This difference likely stems from the distinct mechanisms of nitrogen fertilizer action. Nitrogen fertilizer promotes plant growth, directly increasing SOC, whereas it alters soil chemistry and carbonate deposition in irrigation water, affecting SIC accumulation. In the phosphorus fertilizer experiments, the absence of phosphorus application showed a negative correlation between \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and the increase in irrigation amount. With increased phosphorus fertilizer, its positive effect on SOC was more apparent under high irrigation. When low-phosphorus fertilizer was applied, \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) decreased while \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) increased slightly with increasing irrigation amount, indicating that insufficient phosphorus may exacerbate SOC loss under increased irrigation. These findings underscore the differential sensitivity of SOC and SIC to the interaction between fertilizer and irrigation.

Global mapping of relative SOC and SIC changes under irrigation

We developed a meta-forest model that integrates the strengths of meta-analysis and random forests, accounting for interactions, nonlinearities, and geographic heterogeneity among environmental factors43. This approach enabled us to better understand the geographic variability of SOC and SIC, and to predict their long-term responses to irrigation. The model’s performance was validated with a tenfold cross-validation, achieving an \({R}_{{{\mathrm{CV}}}}^{2}\) of 0.74 for predicting SOC responses to long-term irrigation and \({R}_{{{\mathrm{CV}}}}^{2}\) of 0.70 for SIC responses (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Among the environmental variables, pH was the most influential factor for predicting SIC changes, consistent with findings from previous studies27,31,37, followed by temperature, seasonal variability, and nitrogen fertilizer. In contrast, the primary predictors for SOC changes were total nitrogen, phosphorus fertilizer, and nitrogen fertilizer (Fig. 5).

a showed the percentage change in SOC scaled up by applying the meta-forest approach. b showed the percentage change in SIC scaled up by applying the meta-forest approach. c denoted the uncertainties in the mapped changes of a expressed in terms of the root-mean-square error (MSE). d denoted the uncertainties in the mapped changes of b expressed in terms of the root-mean-square error (MSE). The maps were produced by applying machine learning-based meta-forest models constrained by global soil profile data, multi-year unchanged cropland, and multi-year irrigation levels, with a resolution of 25 km. (\({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{yi}\) represents the response of SOC to long-term irrigation relative to unirrigated cropland, and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) represents the response of SIC to long-term irrigation relative to unirrigated cropland. IWU: multiyear average water use).

We then applied the validated meta-forest model to generate global predictions of SOC and SIC responses to irrigation. Finally, we produced the upscaled maps of \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) along with their associated uncertainty distributions (Fig. 5). The global upscaling maps showed that 54.58% of the stable cropland would have a decrease in SOC and 60.22% in SIC under long-term continuous irrigation, relative to the unirrigated cropland. Geographic heterogeneity in SOC changes was evident, with increases primarily concentrated in mid-latitude regions such as Europe (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the decrease in SOC was mainly concentrated in parts of Asia (Central Asia, Western India, North China). The uncertainty in SOC estimates was larger in regions like India, Southeast Asia, and North China (Fig. 5c). SIC changes were most pronounced in Asia and parts of Europe, with decreases primarily concentrated in India and China (Fig. 5b). Previous research has shown that regions such as South America, the Eastern United States, Central and Western Europe, and Southeast Asia typically have low SIC due to soil properties or limitations in soil profile data31. More importantly, the \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) prediction has greater uncertainty (Fig. 5d), indicating the need for further strengthening of soil monitoring and data collection, especially in regions with high-intensity irrigated areas and in developing countries where data is scarce41.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that irrigation has a negative effect on SOC, especially in surface soils, which was consistent with previous study results8,44. However, under certain conditions, long-term irrigation promotes SOC accumulation, especially in deep soil (beyond 200 cm), contributing to increased soil carbon storage. As a primary method for artificial regulation of soil water, irrigation directly or indirectly affects the transformation and storage of soil carbon7. We observed that irrigation amounts between 200–300 mm enhanced SOC and SIC accumulation at depths of 10–30 cm compared to unirrigated cropland. The responses of soil carbon to irrigation vary significantly under different environmental conditions, which suggests that there may be an optimal irrigation threshold in a specific region that can meet the water demand for crop growth and maximize soil carbon accumulation. Specifically, the mechanisms behind the optimal irrigation threshold differ for SOC and SIC. For SOC, the accumulation and decomposition processes of SOC are regulated mainly by microbial activities, and microbial activity is highly dependent on the soil water status29. When soil moisture is suitable, microbes efficiently decompose plant residues and root exudates, releasing carbon dioxide and stabilizing part of the carbon as SOC45. For SIC, the effects of irrigation are realized primarily by changing the chemistry of the soil environment. Appropriate irrigation can promote the precipitation and accumulation of carbonate, especially in arid and semi-arid areas, where the rate of carbonate formation is relatively slow, and irrigation can constantly replenish carbonate on the soil surface, improving the carbon sequestration capacity5,28.

Our results found that SOC and SIC responses to irrigation are influenced by different environmental factors (e.g., natural conditions, topography, management practices), which often vary by geography. Although we found differences in SOC and SIC responses to irrigation across different amounts of irrigation water, there are also geographical constraints in the application of irrigation. Non-irrigated areas may not be irrigated because it is unnecessary or due to limited access caused by systematic barriers. Moreover, irrigation methods vary geographically, and different techniques exert distinct effects on plant water uptake, depending on crop types, thereby indirectly influencing the SOC and SIC contents of the field5. Specifically, traditional flood irrigation applied to rice easily leads to excessive soil moisture, which results in an anoxic environment and reduces the efficiency of SOC stabilization22. In contrast, precision irrigation methods, such as drip irrigation and sprinklers, allow for better control of soil moisture, reduce evaporation and leakage losses, and help maintain conditions favorable for SOC accumulation14,46,47. Precision irrigation can further optimize carbonate precipitation conditions by adjusting the chemical composition of irrigation water. Subsoil drip irrigation has also been proven to be an effective method for reducing the outgassing of greenhouse gases48. Therefore, future inclusion of irrigation practices in different geographic regions could improve the understanding of irrigation impacts on global soil carbon changes.

In the scale-up maps, the worldwide SIC losses are significantly higher than SOC, especially in China and India. Several factors contribute to this trend. Firstly, extensive irrigation can lead to SIC leaching into groundwater through carbonate dissolution, diminishing long-term carbon stability. Secondly, with global warming and the expansion of agricultural land, the demand for water resources continues to increase, and warming aggravates SIC loss in drylands36. In contrast, SOC primarily derives from the decomposition of plant residues and microbial activity, exhibiting faster turnover rates and more seasonal variation, and responding more quickly to environmental changes. The formation of SIC depends on the slow process of mineral reactions in the soil, and the participation in exchange with the atmosphere and the biological carbon cycle is much slower13. Once subjected to environmental disturbance, the loss rate of SIC is much faster than that of SOC, and the long-term impact on soil carbon pools is greater, which could even be difficult to reverse27,49.

Although current soil carbon management practices primarily focus on SOC, the loss of SIC should not be overlooked from the perspective of global soil carbon storage and the long-term carbon cycle50. The main driving forces of this loss risk are the solubility and mobility of SIC. Our study further analyzed the sensitivity of environmental factors to SOC and SIC responses along the irrigation amounts, highlighting the significant moderating role of these factors. Among them, the response curves of SIC were significantly different in different pH, temperature, nitrogen, and phosphorus fertilizer groups. Especially in arid and semiarid areas, heavy use of nitrogenous fertilizer causes soil acidification, and acidification-induced SIC loss is aggravated30,36,51. Therefore, agricultural irrigation strategies must focus not only on maintaining and accumulating SOC but also on protecting SIC. In high-loss risk areas for SIC, refined irrigation and optimized fertilization strategies should be implemented52. For example, reducing the overuse of nitrogen fertilizer, increasing the application of organic manure53,54,55, and appropriately using alkaline regulators such as lime can improve soil microbial communities, maintain suitable soil pH conditions, and reduce the dissolution and loss of SIC. Additionally, crop rotation and returning crop residues to the soil can help protect soil carbon pools, thereby supporting both soil carbon storage and sustainable agricultural development56.

Limitations and uncertainties

We recognize that the potential bias of source studies for meta-analysis and the upscaling approach may affect our global estimates. First of all, regarding source studies for meta-analysis, most of the primary studies included in our meta‑analysis originate from regions with low to moderate irrigation amounts. Consequently, predicted SOC and SIC changes in the under‑sampled regions display both larger mean responses and larger uncertainty. Secondly, the soil profile data used pertain to croplands without land-use changes in the past 30 years, thereby minimizing carbon loss from anthropogenic land-use change. However, historic land-use change has been shown to impact SOC on the centennial timescale57 and could contribute to some of the observed changes in SOC. Thirdly, 10‑fold cross‑validation of meta-forest models revealed modest shrinkage (Supplementary Fig. 2), which may have led to conservative estimates of the most extreme SOC and SIC responses during global upscaling. In scale-up maps, upscaling results from specific study sites to a global scale revealed geographic uncertainty, since local environmental and management conditions may not be fully represented by the prediction results, potentially leading to overgeneralization or inaccuracies in global estimates. Specifically, irrigation practices, timing, and water quality vary significantly across regions, potentially affecting SOC and SIC differently, and the meta-analyses may not fully capture these nuances. Irrigation practices vary widely by geographic region, reflecting local water availability, climatic conditions, and infrastructural constraints. Fourthly, the idea of space for time could not capture the potential positive effects due to environmental factors associated with irrigation9,39,58. The irrigation data were derived from multi-source data products, covering at least 18 years. While this accounts for long-term irrigation patterns, it assumes that environmental factors across experimental and control groups are either similar or that the effects of environmental factors are relatively very small. In fact, we found significant differences in changes in SOC and SIC across environmental factors as indicated by their sensitivity to irrigation in different subgroups. In reality, irrigation can alter the physicochemical properties of the soil, which in turn affects the biochemical processes of SOC and SIC production and decomposition. Furthermore, the crop growth-promoting effects of fertilizer application, which typically accompanies irrigation, are not sufficiently captured by LAI alone. For example, pH emerged as the most important predictor of SIC loss, however, pH is a comprehensive indicator influenced by multiple factors, such as irrigation, fertilization, and temperature, reflecting the complex interactions between soil and its environment59. In summary, we generated the first global-scale, grid-based atlas of the impact of irrigation on soil carbon, which identifies high-risk areas for the loss of SOC and SIC in stable cropland, offering insights into soil carbon sequestration49. In the future, more measured data on SIC in irrigation practices could help to accurately quantify soil carbon changes, thus facilitating stronger regional and global impacts and reliable predictions.

Methods

Data preprocessing

Site‑level measurements of SOC, SIC, and related soil properties were obtained from the ISRIC World Soil Information Service (WoSIS), supplemented by the Global Soil Inorganic Carbon Database31. The latest global soil profile database has been quality-controlled using standardized processes60. To facilitate comparison and analysis, we harmonized Soil carbon data (SOC and SIC) concentrations into several depth intervals (0–10 cm,10–30 cm, 30–60 cm, 60–100 cm, 100–200 cm, and 200–500 cm), using mass‑preserving spline interpolation implemented with the mpspline2 package in R 4.4.1. Finally, we retained profiles that include SOC and SIC observations in these standard soil layers. Other soil physical and chemical properties were similarly standardized to these depth layers.

On the basis of the idea of the space-for-time approach9,43, first, we categorize the soil profile data according to the irrigation increment of interest (0–50 mm, 50–100 mm, 100–200 mm, 200–300 mm, 300–400 mm, 400–500 mm). To control for the effects of environmental variables, the soil profiles of all the experimental (irrigated) and control (unirrigated) groups should have the same environmental characteristics, which should satisfy the following conditions:

-

(1)

Terrain. Global elevation data were obtained from the WorldClim version 261, and the global land was divided into five general landform types: lowlands (<−50 m), plains (−50 to 200 m), hills (200–500 m), mountains (500–2000 m), high mountains (2000–4500 m), and plateaus (≥4500 m).

-

(2)

Soil type and soil texture. The data were obtained from the World Soil Database version 2.062 (HWSD v2.0). The soil type classification standard was FAO 90 (FAO SOILS PORTAL).

-

(3)

Precipitation. The multiyear precipitation data obtained from WorldClim version 261 were reclassified into five categories: drought (≤400 mm), semiarid (400–600 mm), optimal (600–1000 mm), semihumid (1000–1400 mm), and humid (≥1400 mm).

-

(4)

Temperature. The multiyear mean temperature data were obtained from WorldClim version 261. The temperature difference between the control and experimental groups was maintained within 1 °C.

-

(5)

Fertilization. The nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer data were obtained from the PANGAEA maps63. The difference in the amount of cultivated nitrogen fertilizer applied to the experimental and control groups was not greater than 1 g·m−2·year−1. The same was true for the amount of phosphorus fertilizer applied to the experimental and control groups.

-

(6)

Land use type and tillage intensity. The land use data for 1992-2020 were obtained from the European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (ESA CCI)64. The land use data were used to screen the soil profile data, and the land use type for the experimental and control groups was cropland that had not changed from 1992 to 2020, and the 4427 soil points were stable cropland (Fig. 6). The tillage intensities of the arable land in the control group and the experimental group remained consistent65.

-

(7)

Irrigation water data. The global multiyear agricultural irrigation water usage (IWU) data were obtained from Zhang et al.40. In fact, the IWU was set to be the actual volume of water entering the cropland. The time frame of the IWU data is from 2011-2018, on a monthly scale. Compared with traditional statistical data, these data have lower variation at different spatial scales40, with a spatial resolution of 25 km. Furthermore, the global area of irrigation facilities (AEI) is derived from Mehta et al., and the data spans the period 2000–2015, with a spatial resolution of 5 arcmin. The AEI data are used to determine the historical irrigation duration. Combining the AEI and IWU data, the soil profiles of the experimental and control groups were continuously irrigated from 2000 to 2018. IWU digital maps are used to set the amount of irrigation water of interest.

Meta-analysis

We used a hybrid approach combining space-for-time substitution with meta-analytic techniques that has been successfully applied in several studies8,9,18, and we applied this approach to obtain SOC and SIC datasets differentiated by irrigation amount, including the experimental group (the irrigation increment of interest, 0–500 mm) and the control group (0 mm).

We used a random effects meta-analysis to assess the response of SOC and SIC to irrigation. The “escalc” function in the R package “metafor” was used to quantify the effect size66. The logarithmic response ratio (InRR) and the percentage change (P) in the SOC and SIC in the irrigation experiment were calculated as follows:

where \({\bar{X}}_{it}\) and \({\bar{X}}_{ic}\) represent the mean values of the experimental group and the control group, respectively. \({v}_{i}\), where \({{{\mathrm{SD}}}}_{it}^{2}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SD}}}}_{ic}^{2}\) represent the standard deviations of the experimental group and the control group, respectively. \({n}_{{it}}\) and\({n}_{{ic}}\) represent the first i-th group, the numbers of samples in the experimental group and the control group,\({v}_{i}^{* }\) is the total variance of Group i, \({r}^{2}\) is the variance between different groups, and\({w}_{i}^{* }\) is the weight of the first group of studies. \({{Q}}_{t}\) The chi-square statistic was used to assess population heterogeneity among the studies. If \({Q}_{t}\) if P < 0.05, the residual differences are significant, and a regression model needs to be introduced to elucidate the source of the heterogeneity.

Variable importance and scaling-up approach

We introduced explanatory variables to the meta-analysis of the random effects model, that is, the environmental variables in the irrigation experimental system. We included 23 potential influencing factors. However, the 23 adjustment factors in the meta-regression may overfit the model. Therefore, we used the R package “Metaforest” in R 4.4.1 to determine the final potential adjustment factors that need to be included, and the final filtered environment variables are shown in Fig. 5. This meta-forest method is robust to overfitting, and the idea is to combine the variance and weight of each experiment into the meta-analysis model43. Therefore, we used a meta-forest model to determine the relative importance of environmental variables on SOC and SIC irrigation responses. \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) represents the response of SOC to long-term irrigation relative to unirrigated cropland, and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) represents the response of SIC to long-term irrigation relative to unirrigated cropland.

Specifically, we preselected 23 predictors in metaforest, used the “preselect” function of the “metafor” package to repeat the recursive algorithm 100 times, and iterated this process 10,000 times. We used the “preselect_vars” function to remove environmental variables that always have negative importance and use the environmental variables that enhance the predictive performance to optimize the model38. We then used the “train” function in the “caret” package to optimize the parameters and calculated the 10-fold cross-validation R2 to generate the model with the best generalizability. The model performances are \({R}_{{{\mathrm{OBB}}}}^{2}\) = 0.58 and \({R}_{{{\mathrm{CV}}}}^{2}\) = 0.74 for \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) prediction, and the model performances are \({R}_{{{\mathrm{OBB}}}}^{2}\) = 0.51 and \({R}_{{{\mathrm{CV}}}}^{2}\) = 0.70 for \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) prediction, with the cross-validation results presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Finally, the validated meta-forest model is applied to the global grid data of the predictor variables to estimate the upscaled \({{{\mathrm{SOC}}}}_{{yi}}\) and \({{{\mathrm{SIC}}}}_{{yi}}\) in global irrigated cropland. The relative uncertainty of the prediction was estimated by the coefficient of variance (C.V., %) of the ten simulations when training random forest models.

Data availability

All the data used in this study are from publicly accessible data sources. World Soil Information Service60 (WoSIS) and Global Soil Inorganic Carbon Database31 (https://figshare.com/s/26f03972cc42b2e1e09f) provided quality-assessed and standardized global soil profile data. The soil property grid data were obtained from SoilGrid 2.067 (https://soilgrids.org/) and the Harmonized World Soil Database version 2.062 (HWSD v2.0) (https://gaez.fao.org/pages/hwsd). Terrain data and climate data were obtained from WorldClim version 261 (https://worldclim.org/). The nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer data in croplands were derived from the PANGAEA maps63 (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.863323), which provides annual estimates from 1900 onward based on national statistics and modeling themselves. The tillage intensity data were derived from Liu et al.65 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.15128076). The global estimation of irrigation water use (IWU) data was obtained from Zhang et al.40 (https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030031). The global area of irrigation facilities (AEI) was derived from Mehta et al.2 (https://zenodo.org/records/6886564). Crop type data was from the 2020 SPAM68 (Spatial Production Allocation Model) products in the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SWPENT). The cropland distribution was from ESA Climate Change Initiative (CCI) Land Cover Maps64 (https://data.ceda.ac.uk/neodc/esacci/land_cover/data).

Code availability

All the code was compiled in R 4.4.1. The R code for the full analysis can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wang, X. H. et al. Global irrigation contribution to wheat and maize yield. Nat. Commun. 12, (2021).

Mehta, P. et al. Half of twenty-first century global irrigation expansion has been in water-stressed regions. Nat. Water 2, 254–261 (2024).

Lal, R. Digging deeper: a holistic perspective of factors affecting soil organic carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 3285–3301 (2018).

Emde, D., Hannam, K. D., Most, I., Nelson, L. M. & Jones, M. D. Soil organic carbon in irrigated agricultural systems: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 3898–3910 (2021).

Ball, K. R., Malik, A. A., Muscarella, C. & Blankinship, J. C. Irrigation alters biogeochemical processes to increase both inorganic and organic carbon in arid-calcic cropland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 187, 109189 (2023).

Xiao, C. et al. Optimizing drip irrigation and nitrogen fertilization regimes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, increase net ecosystem carbon budget and reduce carbon footprint in saline cotton fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 366, 108912 (2024).

McDermid, S. et al. Irrigation in the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 435–453 (2023).

Yao, X. C., Zhang, Z. Y., Yuan, F. H. & Song, C. C. The impact of global cropland irrigation on soil carbon dynamics. Agric. Water Manag. 296, 108806 (2024).

Wang, M. M. et al. Global soil profiles indicate depth-dependent soil carbon losses under a warmer climate. Nat. Commun. 13, 5514 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Sustainable irrigation and climate feedbacks. Nat. Food 4, 654–663 (2023).

You, Y. F. et al. Net greenhouse gas balance in US croplands: How can soils be part of the climate solution? Glob. Chang. Biol. 30, 17109 (2024).

Abdo, A. I. et al. Conventional agriculture increases global warming while decreasing system sustainability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 110–117 (2025).

Zamanian, K., Pustovoytov, K. & Kuzyakov, Y. Pedogenic carbonates: forms and formation processes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 157, 1–17 (2016).

Li, G. C. et al. Effects of drip irrigation upper limits on rhizosphere soil bacterial communities, soil organic carbon, and wheat yield. Agric. Water Manag. 293, 108701 (2024).

Tan, M. D. et al. Long-term mulched drip irrigation enhances the stability of soil aggregates by increasing organic carbon stock and reducing salinity. Soil Till Res. 240, 106069 (2024).

Guo, H. B., Du, E., Terrer, C. & Jackson, R. B. Global distribution of surface soil organic carbon in urban greenspaces. Nat. Commun. 15, 806 (2024).

Crowther, T. W. et al. The global soil community and its influence on biogeochemistry. Science 365, 772–77 (2019).

Núñez, A. & Schipanski, M. Changes in soil organic matter after conversion from irrigated to dryland cropping systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 347, 108392 (2023).

Zhu, K. Y. et al. Controlled irrigation can mitigate the greenhouse effects of rice paddy fields with long-term straw return and stimulate microbial necromass carbon accumulation. Field Crop Res. 317, 109571 (2024).

Trost, B. et al. Irrigation, soil organic carbon and NO emissions. a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 33, 733–749 (2013).

Condron, L. M., Hopkins, D. W., Gregorich, E. G., Black, A. & Wakelin, S. A. Long-term irrigation effects on soil organic matter under temperate grazed pasture. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 65, 741–750 (2014).

Feng, Z. Y., Qin, T., Du, X. Z., Sheng, F. & Li, C. F. Effects of irrigation regime and rice variety on greenhouse gas emissions and grain yields from paddy fields in central China. Agric. Water Manag. 250, 106830 (2021).

Nie, T. Z. et al. The inhibitory effect of a water-saving irrigation regime on CH4 emission in Mollisols under straw incorporation for 5 consecutive years. Agric. Water Manag. 278, 108163 (2023).

Gao, D., Bai, E., Wasner, D. & Hagedorn, F. Global prediction of soil microbial growth rates and carbon use efficiency based on the metabolic theory of ecology. Soil Biol. Biochem. 190, 109315 (2024).

Dong, X. et al. Long-term saline water irrigation decreased soil organic carbon and inorganic carbon contents. Agr. Water Manag. 270, 107760 (2022).

De Soto, I. S. et al. Changes in the soil inorganic carbon dynamics in the tilled layer of a semi-arid Mediterranean soil due to irrigation and a change in crop. Uncertainties in the calculation of pedogenic carbonates. Catena 246, 108362 (2024).

Song, X. D. et al. Significant loss of soil inorganic carbon at the continental scale. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, 120 (2022).

Liang, J., Zhao, Y., Chen, L. & Liu, J. Soil inorganic carbon storage and spatial distribution in irrigated farmland on the North China Plain. Geoderma 445, 116887 (2024).

Zamanian, K., Zarebanadkouki, M. & Kuzyakov, Y. Nitrogen fertilization raises CO efflux from inorganic carbon: a global assessment. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 2810–2817 (2018).

Raza, S. et al. Dramatic loss of inorganic carbon by nitrogen-induced soil acidification in Chinese croplands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 3738–3751 (2020).

Huang, Y. et al. Size, distribution, and vulnerability of the global soil inorganic carbon. Science 384, 233–239 (2024).

Mishra, V. et al. Moist heat stress extremes in India enhanced by irrigation. Nat. Geosci. 13, 722–72 (2020).

Thiery, W. et al. Warming of hot extremes alleviated by expanding irrigation. Nat. Commun. 11, 290 (2020).

Pries, C. E. H., Castanha, C., Porras, R. C. & Torn, M. S. The whole-soil carbon flux in response to warming. Science 355, 1420–1422 (2017).

García-Palacios, P. et al. Evidence for large microbial-mediated losses of soil carbon under anthropogenic warming (vol 2, pg 507, 2021). Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 585–585 (2021).

Li, J. Q., Pei, J. M., Fang, C. M., Li, B. & Nie, M. Drought may exacerbate dryland soil inorganic carbon loss under warming climate conditions. Nat. Commun. 15, 617 (2024).

Raza, S. et al. Inorganic carbon losses by soil acidification jeopardize global efforts on carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation. J. Clean. Prod. 315, 128036 (2021).

Gao, R. et al. Effects of alternate wetting and drying irrigation on yield, water-saving, and emission reduction in rice fields: a global meta-analysis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 353, 110075 (2024).

Rossel, R. A. V. et al. Continental-scale soil carbon composition and vulnerability modulated by regional environmental controls. Nat. Geosci. 12, 547–54 (2019).

Zhang, K., Li, X., Zheng, D. H., Zhang, L. & Zhu, G. F. Estimation of global irrigation water use by the integration of multiple satellite observations. Water Resour. Res. 58, 30031 (2022).

Bughio, M. A. et al. Neoformation of pedogenic carbonates by irrigation and fertilization and their contribution to carbon sequestration in soil. Geoderma 262, 12–19 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Effects of fertilization applications on soil aggregate organic carbon content and assessment of their influencing factors: a meta-analysis. Catena 242, 108135 (2024).

Terrer, C. et al. A trade-off between plant and soil carbon storage under elevated CO. Nature 591, 599–59 (2021).

Yan, Z. X. et al. Changes in soil organic carbon stocks from reducing irrigation can be offset by applying organic fertilizer in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 266, 107539 (2022).

Tao, F. et al. Microbial carbon use efficiency promotes global soil carbon storage. Nature 618, 981–98 (2023).

Jiang, Q. J. et al. Potential contribution of water management practices under intensive crop production to climate-change-associated global warming. J. Clean. Prod 470, 143230 (2024).

Chai, Q. et al. Regulated deficit irrigation for crop production under drought stress. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36, 3 (2016).

Huo, P. & Gao, P. C. Degassing of greenhouse gases from groundwater under different irrigation methods: a neglected carbon source in agriculture. Agric. Water Manag. 301, 108941 (2024).

Goldstein, A. et al. Protecting irrecoverable carbon in Earth’s ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 287–295 (2020).

Liu, J. B., Zhang, P. & Gao, Y. Effects of vegetation rehabilitation on soil inorganic carbon in deserts: a meta-analysis. Catena 231, 107290 (2023).

Zamanian, K. & Kuzyakov, Y. Contribution of soil inorganic carbon to atmospheric CO: More important than previously thought. Glob. Change Biol. 25, E1–E3 (2019).

Li, C. H., Yan, K., Tang, L. S., Jia, Z. J. & Li, Y. Change in deep soil microbial communities due to long-term fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem 75, 264–272 (2014).

Liu, J. A. et al. Long-term organic fertilizer substitution increases rice yield by improving soil properties and regulating soil bacteria. Geoderma 404, 115287 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Nitrogen fertilization weakens the linkage between soil carbon and microbial diversity: a global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 6446–6461 (2022).

Liu, H. W. et al. Organic substitutions improve soil quality and maize yield through increasing soil microbial diversity. J. Clean. Prod. 347, 131323 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Crop residue return sustains global soil ecological stoichiometry balance. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2203–2226 (2023).

Emde, D., Poeplau, C., Don, A., Heilek, S. & Schneider, F. The centennial legacy of land-use change on organic carbon stocks of German agricultural soils. Glob. Chang. Biol. 30, 8 (2024).

Crowther, T. W. et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104–10 (2016).

Wang, C. Q. & Kuzyakov, Y. Soil organic matter priming: the pH effects. Glob. Chang. Biol. 30, 6 (2024).

Batjes, N. H., Calisto, L. & de Sousa, L. M. Providing quality-assessed and standardised soil data to support global mapping and modelling (WoSIS snapshot 2023). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 4735–4765 (2024).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Sinitambirivoutin, M. et al. An updated IPCC major soil types map derived from the harmonized world soil database v2.0. Catena 244, 108258 (2024).

Lu C. & Tian H. Half-degree gridded nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer use for global agriculture production during 1900-2013. In: Supplement to: Lu, C; Tian, H (2017): Global nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer use for agriculture production in the past half century: shifted hot spots and nutrient imbalance. Earth System Science Data, 9(1), 181-192, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-181-2017) (PANGAEA, 2016).

Harper, K. L. et al. A 29-year time series of annual 300 m resolution plant-functional-type maps for climate models. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1465–1499 (2023).

Liu, X. X. et al. Annual dynamic dataset of global cropping intensity from 2001 to 2019. Sci. Data 8, 283 (2021).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. Soil-Ger. 7, 217–240 (2021).

International Food Policy Research I. Global Spatially-Disaggregated Crop Production Statistics Data for 2020 Version 1.0. V3 edn (ed International Food Policy Research I). Harvard Dataverse (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.2022YFB3903302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.T. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, field research, analysis, writing, and editing. Y.X. contributed to data interpretation and writing. L.H. contributed to the methodology. Y.C. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, analysis, and writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Roberta Farina and David Emde, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Q., Xu, Y., Hua, L. et al. Global soil organic and inorganic carbon vulnerability in response to irrigation. Commun Earth Environ 6, 599 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02591-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02591-9