Abstract

Microearthquakes generated by subsurface fluid injection record the evolving stress state and permeability of reservoirs. Forecasting their spatiotemporal evolution is therefore critical for applications such as enhanced geothermal systems, carbon dioxide sequestration and other geoengineering applications. Here we propose a transformer neural network model that ingests hydraulic stimulation history and prior microearthquake observations to forecast four key quantities: cumulative microearthquake count, cumulative logarithmic seismic moment, and the 50th- and 95th-percentile extents of the microearthquake cloud. Applied to the EGS Collab Experiment 1 dataset, the model achieves R2 > 0.98 for the 1-s forecast horizon and R2 > 0.88 for the 15-s forecast horizon across all targets, and supplies uncertainty estimates through a learned standard deviation term. These accurate, uncertainty-quantified forecasts enable real-time inference of fracture propagation and permeability evolution, demonstrating the strong potential of deep-learning approaches to improve seismic-risk assessment and guide mitigation strategies in future fluid-injection operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subsurface applications for climate mitigation and sustainability are essential to achieving the net-zero emissions target set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for 20501. Key geo-engineering strategies include the development of enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) for renewable energy generation and the geological storage of carbon dioxide (CO2) to reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimates that EGS could provide over 500 GWe of electricity in the western United States alone2. In addition, carbon dioxide sequestration has the potential to store at least 1000 GtCO2 in saline aquifers, with further storage capacity available in depleted oil and gas reservoirs and coal formations3,4. Despite the immense potential to reduce greenhouse gases through these subsurface applications, a key challenge is the induced seismicity that can result from fluid injection operations5,6,7. Fluid injection perturbs in-situ stress fields in the subsurface, potentially leading to the reactivation of preexisting faults or the creation of new fractures, both potentially compromising the integrity of reservoirs8. Notable examples include the magnitude 5.7 2015 Prague and magnitude 5.8 2016 Pawnee earthquakes in Oklahoma after wastewater injection9,10,11,12—and a magnitude 3.9 earthquake following circulation tests for the EGS project in Vendenheim, France13. These events underscore the critical need for accurate forecasting of induced seismicity to ensure the safe implementation of subsurface technologies.

Accurately forecasting fluid-induced seismicity remains a challenge due to the complex interactions between geological, hydrological, and mechanical factors5,14. Traditional approaches rely on physics-based models to estimate induced seismicity by coupling fluid flow, mechanical deformation, and seismicity rates15,16,17,18. Although these models can capture intricate subsurface interactions, they face limitations in real-world applications. Challenges include uncertainties in fracture geometries, material heterogeneity, and in-situ stress conditions. Moreover, assumptions such as isotropic material properties or idealized fracture networks are often required, reducing predictive accuracy. High computational costs associated with three-dimensional modeling with complex fracture geometries further restrict their use in practical forecasting and operational decision-making15,17. As a result, discrepancies between modeled and observed seismicity frequently occur.

From a statistical perspective, the Epidemic-Type Aftershock Sequence (ETAS) model provides a forecasting approach for both natural and fluid-induced seismicity, based on the assumption that an earthquake can trigger clusters of aftershocks19,20. In particular, nonstationary ETAS models have effectively demonstrated their capability in detecting the impacts of fluid-induced seismicity by employing a nonstationary background rate19,21,22,23. This capability positions ETAS as a valuable tool for generating probabilistic earthquake forecasts. However, determining key parameters, including the timing of peak activity, solely based on statistical analysis has been challenging24. Thus, successful applications of ETAS models to spatiotemporal forecasting of microearthquakes (MEQs) due to fluid injection may be limited.

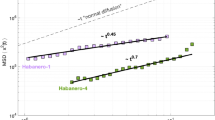

Data-driven approaches—particularly machine learning—have emerged as powerful complements or alternatives to traditional frameworks including both physics-based and statistical approaches, in a range of geoscientific applications25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. These methods do not require detailed prior knowledge of uncertain subsurface properties but instead leverage large datasets from monitoring systems to identify patterns and correlations that can be used for forecasting. For instance, deep learning—with and without physical constraints—was used to forecast the seismicity rate, which was then used to estimate the maximum magnitude of fluid-induced microseismicity38. A bidirectional long short-term memory neural network predicted fluid-induced permeability evolution based on MEQ features, including seismic rate and cumulative logarithmic seismic moment39. In addition, an LSTM model was employed to predict average permeability changes inferred from the seismicity data. Another LSTM model was used to predict pore pressure and associated fault displacements given the fluid injection cycles40. These studies demonstrate that deep learning approaches can effectively capture the temporal evolution of permeability or micro-seismicity based on operational parameters. However, they often focus solely on temporal predictions without considering the spatial evolution of MEQs, which is critical for assessing the extent of affected areas and potential impacts. Furthermore, these models rely on simplified assumptions for permeability changes, such as the migration of the triggering front of the MEQ cloud assuming proportionality to the square root of time since the initiation of injection, which is inconsistent with observed MEQ data41. These idealizations limit the applicability and accuracy of the models in complex scenarios.

Our study advances the forecasting of the spatiotemporal evolution of MEQs induced by hydraulic stimulation using a deep learning approach that tackles these challenges. Specifically, we employ transformer networks, a type of neural network architecture that uses self-attention mechanisms to capture complex dependencies within data sequences42,43. Compared with recurrent neural networks such as LSTMs, transformer networks can model long-range temporal dependencies more efficiently and are less susceptible to issues like vanishing gradients44. Their ability to focus on different parts of the input data through attention mechanisms makes them particularly well-suited for capturing both spatial and temporal patterns in MEQ data. Based on hydraulic stimulation history, our model predicts key MEQ features, including the cumulative number of MEQs, cumulative seismic moment, and the spatial extent of induced micro-seismicity. By incorporating both spatial and temporal information, the model provides more comprehensive forecasts that can inform real-time monitoring and risk mitigation strategies in subsurface activities.

Results

We use hydraulic stimulation data and MEQ history from the EGS Collab45,46. Figure 1 shows the architecture of our transformer model for forecasting the spatiotemporal evolution of MEQs based on hydraulic stimulation and MEQ histories (see Section “ Method: Transformer neural network architecture ”).

EGS Collab hydraulic stimulation datasets

We utilize hydraulic stimulation and MEQ data from the EGS Collab project, intermediate-scale (10–20 m) field tests at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota. This study focuses on Experiment 1 data, aimed at producing a fracture network connecting an injection well to a production well via hydraulic fracturing47. A series of stimulations and flow tests were conducted at a depth of 1.5 km to re-open and generate hydraulic fractures in crystalline rock under reservoir-like stress conditions, with passive seismic data cataloged48 and Continuous Active-Source Seismic Monitoring45,49,50.

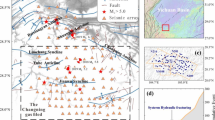

Figure 2 shows the stimulation-induced MEQs for each stimulation event along with the injection and production wells. Two 60 m boreholes were used for injection (E1-I) and production (E1-P), respectively. A total of five stimulation episodes were carried out in May 2018. During the first two stimulations, injections at flow rates less than 1L/min produced few MEQs. In addition, water leakage was observed between the production well and one monitoring well. Thus, the injection point was moved to a notch at a depth of 50 m in the injection hole (red triangle in Fig. 2) starting from Stimulation 3 and used through Stimulation 5. From Stimulations 3–5, three continuous hydraulic stimulations were performed using controlled step-rate injections to re-open or create fractures around the injection well, with the maximum injection rate reaching up to 5 L/min, resulting in rich MEQ signals46,51. Thus, this study uses data from Stimulations 3 to 5, generated from the same injection point with a rich MEQ history, to train neural networks. The data were recorded at 1-s intervals. Stimulations 3 and 4 each lasted approximately 1 h (3600 time steps), and the first 1 h and 10 min of Stimulation 5 were used (4100 time steps). These continuous records were segmented into overlapping input-output windows for supervised training, validation, and testing, as described in section “Data preprocessing: crop and normalization”.

The figure shows the three-dimensional spatial distribution of microearthquakes (MEQs) generated during three hydraulic stimulation episodes. The solid black line represents the injection well, and the dashed black line represents the production well. A red triangle marks the injection point located at the 50 m notch in the injection well. Colored scatter points indicate MEQ locations: yellow for stimulation 3, green for stimulation 4, and purple for stimulation 5.

Figure 3 presents the series of stimulations along with the spatiotemporal MEQ data and corresponding magnitudes. Detailed information about the MEQs—including location, time, and magnitudes—was continuously monitored during the hydraulic stimulations45,46. In addition, to quantify the spatial extent of MEQs in response to fluid injection, we extracted the 95th and 50th percentiles (median) distances of the MEQ clouds from the injection points as a function of time. Although the monitoring array is extensive, the catalog still carries intrinsic uncertainties: hypocenter locations are accurate to about 1 m and there is no reported uncertainty range for magnitude45. These uncertainties limit the fidelity of the training data and establish a floor on achievable forecast accuracy. Additionally, including all raw events—without excluding those below the magnitude of completeness—could constrain the neural network’s capability to learn underlying MEQ patterns (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Columns correspond to: Stimulation 3 (training data), Stimulation 4 (validation data), and Stimulation 5 (test data). The first row presents the hydraulic stimulation history, showing injection rate (blue) and injection pressure (red). The second row displays the locations of microearthquakes (MEQs) relative to the injection point, with distances calculated as the Euclidean distance between the injection point and observed microseismic events. P95 and P50 represent the 95th and 50th percentile distances over time. The third row shows the cumulative number of MEQ events and the magnitude of each discrete event.

Forecasting performance

We evaluate three forecast intervals—1 s, 15 s, and 30 s—using a sliding-window strategy. At each forecasting instant tn, the model ingests the entire monitoring history [t0, tn] and predicts subsequent interval [tn+1, tn + lfuture], where lfuture is the forecast range (e.g., 1 s, 15 s, or 30 s). For instance, when using a 15 s range, the model forecasts the next 15 s (e.g., t101–t115) based on the history data t1−t100. Once actual monitoring for these 15 s is recorded, these new data (t101−t115) are appended to the monitoring history. The model then uses the extended history t1−t115 to forecast the following segment t116−t130, and this procedure repeats until the monitoring concludes. Since the model consistently utilizes actual measurements without recycling previously predicted outputs, forecasting errors do not accumulate over successive forecasts (Fig. 4).

Figure 5 compares the forecasted and observed cumulative MEQ counts. For the 1-second forecast model the predicted curves are virtually indistinguishable from the ground truth, even on unseen data (validation R2 = 0.999, test R2 = 0.980). The 15-second forecast model maintains high fidelity (validation R2 = 0.929, test R2 = 0.972), with a slight tendency to overestimate MEQ growth during the most intense injection phases. The 30-s forecast model still captures the overall trend but systematically underpredicts the MEQ count late in each episode (validation R2 = 0.649, test R2 = 0.809). These results show that the transformer delivers excellent short-term forecasts, with accuracy declining gradually as the forecast window lengthens.

Each forecast curve is constructed by predicting successive, non-overlapping segments whose length equals the forecast interval and concatenating them to cover the full record. Panels show the training (left), validation (middle), and test (right) sets. Shaded bands denote ±σ (one predicted standard deviation, corresponding to ≈ 68% coverage under a Gaussian assumption).

Second, we forecast the cumulative logarithmic seismic moment, a proxy for the activated reservoir volume and thus a key metric for planning new production wells52,53. The cumulative moment \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\) is defined as39

with

where M0 is the seismic moment, Mw the moment magnitude, t0 the start of injection, and ti the current injection time.

Figure 6 compares the predicted and observed cumulative moments for the 1-, 15-, and 30-s forecast models across the three data splits. The 1-s forecast model reproduces the observations almost exactly (validation R2 = 0.999, test R2 = 0.978). Performance remains high at 15-s forecast model (validation R2 = 0.878, test R2 = 0.935), although the predictive bands widen compared with the 1-s case. At 30-s forecast the model still captures the overall trend but underestimates the released seismic energy (validation R2 = 0.546, test R2 = 0.765). These results confirm that our neural network effectively links hydraulic-energy input to seismic-energy release, providing reliable short-term estimates of cumulative moment while showing a gradual and interpretable loss of accuracy as the forecast range increases.

Accurately forecasting the spatial evolution of MEQ clouds is critical for delineating the affected area, guiding mitigation, and optimizing future well placement15. Figure 7 compares the spatial extent of the MEQ clouds across the training, validation, and test sets, quantified by the 50th and 95th percentiles of the Euclidean distance from the injection point. The 1-s and 15-s forecast models reproduce the ground truth trajectories of both the median distance (P50) and the far distance (P95), achieving R2 > 0.97 for the 1-s forecast model and R2 > 0.94 for the 15-s forecast model.

The three rows correspond to the training (top), validation (middle), and test (bottom) datasets. In each row, the solid curve shows the observed 50th-percentile distance (P50) and the dashed curve the observed 95th-percentile distance (P95). Forecasts from the 1-, 15-, and 30-s models are plotted in blue, red, and green, respectively. Shaded regions denote ±σ (standard deviation).

Figure 8 illustrates the final stabilized extents predicted by these models: absolute errors are below 0.4 m for the 1-s model and below 2 m for the 15-s model (Table 1). For the 1-second case, the observed-predicted differences lie within the model’s ±σ band, indicating that the discrepancies are consistent with the reported uncertainty. In contrast, the 15-s differences exceed σ, revealing the limitations of the mid-range model. The 30-s model underestimates both P50 and P95 in all data splits, highlighting its reduced reliability for long-range spatial forecasts.

The figure shows the spatial distribution of MEQs and forecast results for different datasets and time horizons. Each row represents a dataset: training (top), validation (middle), and test (bottom). Each column shows projections on the XY, YZ, and ZX planes. Solid circles indicate the observed 50th-percentile radius (P50), while dashed circles represent the 95th-percentile radius (P95). Blue and red lines show forecasts from the 1-s and 15-s models, respectively, with shaded regions denoting ±σ (one predicted standard deviation). Colored dots represent MEQs from different stimulation phases: yellow for Stim 3, green for Stim 4, and purple for Stim 5. Solid black lines indicate the injection well, dashed black lines the production well, and red triangles mark the injection point. All spatial dimensions are in meters.

Discussion and conclusion

Our transformer model accurately forecasts fluid-induced MEQs, capturing both their temporal evolution and spatial growth (Table 2). This dual capability is, to the best of our knowledge, novel; earlier studies focused mainly on temporal predictions39,54. Reliable spatiotemporal forecasts are essential for estimating permeability changes and mitigating the risks associated with induced seismicity. In the following, we discuss how permeability enhancement can be inferred from monitoring data and model outputs, how fracture characteristics can be estimated, and the potentials and limitations of deep-learning-based forecasting for field-scale, fluid-induced earthquakes.

Estimation of permeability enhancement

Estimating permeability enhancement is a critical task in EGS, yet direct measurements are challenging in the subsurface. This limitation also applies to our study—we aim to understand how permeability evolves during hydraulic stimulation, but no direct measurements were available from the field experiment. Although the correlation between MEQs and permeability remains elusive55, we derive a physically grounded rationale to indirectly estimate permeability using model outputs. Specifically, we apply the cubic law for permeability, which relates changes in fracture aperture to permeability change56,57:

where Δk is the permeability change, b0 is the initial fracture aperture, Δb is the aperture change, and s is the spacing between parallel fractures. Assuming that the initial aperture b0 is negligible compared to the aperture change (i.e., b0 ≪ Δb), we approximate the permeability evolution as \(\Delta k\approx \frac{\Delta {b}^{3}}{12s}\). Given that the EGS Collab Experiment 1 aimed to establish fracture networks via hydraulic fracturing (i.e., tensile fractures)55,58, we assume the seismic moment is linked to normal displacement by tensile opening. The equivalent moment M0 for a tensile opening can be expressed as39:

where G is the shear modulus, A is the area of the fracture, and Δun is the normal displacement across the fracture. Assuming the area A of the fracture is proportional to the aperture (A ∝ Δb)59, we establish a direct proportionality between seismic moment M0 and permeability change as60:

With these scaling relationships, we infer that the overall logarithmic permeability increment is linearly proportional to the logarithmic seismic moment, though this assumption primarily holds during early stimulation, where the initial aperture is substantially smaller than the aperture increment (i.e., b0 ≪ Δb).

During the first stimulation, the observed cumulative logarithmic seismic moment reaches ≈3 (Fig. 6 left), implying a permeability increase of roughly two orders of magnitude. The 1-s forecast reproduces this estimate, whereas the 15-s forecast model overpredicts the moment by about one order of magnitude, and the 30-s forecast model underpredicts it by a similar amount. Because the cumulative seismic moment predicted by our network can be mapped directly to permeability changes, the model provides a practical, indirect means of tracking permeability evolution during hydraulic stimulation—though this mapping is valid only for the initial seismic—moment range where the derivation’s assumptions hold.

Inference of the fracture characteristics

In fluid injection operations, we need to control the spatial extent of fracturing. As an example, in EGS fields, it is crucial to prevent MEQs from extending beyond the region between injection and production wells while enhancing permeability within this region through fracturing. Our model provides estimates of two spatial extents of MEQs: the 95th percentile distance (P95) and the 50th percentile distance (P50). P95 represents the far extent of MEQs, while P50 indicates the most active MEQ regions, which likely correspond to areas of greatest permeability increase due to fracture generation and re-opening.

The importance of tracking P95 and P50 becomes clear when the spatial extents from each stimulation are compared (Table 1). From stimulation 3 (training) to stimulation 4 (validation), the observed P95 grows by 3.85 m (from 10.23 to 14.08 m), while P50 retreats by 0.21 m (from 5.92 to 5.71 m), indicating a slight shrinkage of the seismically active zone. Our 1-s forecast model reproduces these shifts almost exactly, predicting a 4.27 m increase in P95 (from 10.74 to 15.01 m) and 0.13 m retreat in P50 (from 6.29 to 6.16 m); all absolute errors fall within the 1-s forecast model’s ±σ band. Between stimulation 4 (validation) and stimulation 5 (test), the observed P95 increases by 1.15 m (from 14.08 to 15.23 m), whereas P50 advanced by 4.21 m (from 5.71 to 9.92 m). The 1-s forecast model again captures these trends, predicting a 0.94 m rise in P95 (from 15.01 to 15.95 m) and 4.09 m increase in P50 (from 6.16 to 10.25 m). By accurately forecasting P50 and P95 in real time, the network enables practitioners to infer fracture propagation and activation, making it a practical tool for managing stimulation where direct measurements are not feasible.

Potential and challenges of deep learning forecasting

Among the various deep learning approaches, we chose the transformer model as our core architecture. The success of the transformer model is driven by several key factors. First, the self-attention mechanism allows the model to capture long-term dependencies42,61,62, which are crucial in fluid-induced seismicity, where MEQs are influenced by cumulative fluid injection, pore pressure changes, and perturbed in-situ stress conditions2. In particular, fluid-induced seismicity often exhibits long time intervals between injection and seismicity. For instance, the largest earthquake (local magnitude 3.9) at the deep geothermal site GEOVEN in Vendenheim occurred more than six months after shut-in63. The self-attention mechanism enables the model to weigh the importance of different input features over time, making it highly suited for sequential data44.

Second, transformers excel at processing spatiotemporal data64, which is vital for accurately predicting the spatial distribution of MEQs. This ability provides critical insights into fracture propagation65 and fluid migration66, both of which are key factors in assessing the effectiveness of hydraulic stimulation. The model’s performance in predicting the spatial extent of seismic events reflects its capacity to capture both the temporal and spatial dynamics of fluid injection-induced microseismicity. Third, the transformer’s non-recurrent architecture allows it to handle irregular time series data67, a common occurrence in microseismic monitoring due to variable injection schedules and operational pauses. This flexibility enhances the model’s robustness across different stimulation phases and geological settings, making it adaptable to varying conditions and data availability—a common challenge in real-world geophysical applications.

While the model shows promising results, extending it to large-scale field operations introduces additional uncertainties due to unknown geological heterogeneity and the extended temporal dependencies inherent to fluid-induced seismicity. The data used in this study were collected from an intermediate-scale (10–20 m) experiment with comprehensive monitoring tools from the EGS Collab project47,50. Such dense instrumentation may not be feasible in reservoir-scale engineering applications, raising questions about the model’s generalizability to less controlled, large-scale environments. One promising strategy for adapting deep learning forecasting techniques to larger-scale fluid-induced seismicity applications involves transfer learning with fine-tuning. For example, successful transferability between datasets from Utah FORGE and EGS Collab was recently demonstrated using appropriate fine-tuning methods39. Although further fine-tuning will likely be required to adjust the model to larger operational scales, the fundamental assumption remains that the neural network model learns generalizable signal patterns associated with fluid-induced MEQs. Additionally, integrating uncertainty quantification into predictions becomes increasingly important given the higher uncertainty inherent in real-field-scale operations. By incorporating these strategies, along with judicious monitoring, transformer networks could be systematically validated and effectively implemented at larger scales. Future work could involve training and validating the model’s performance with field-scale fluid-induced seismic data and hydraulic stimulation histories, thus ensuring robustness in more complex geological settings.

In summary, despite limitations related to monitoring systems and scale, this study presents a deep learning based approach for forecasting MEQs in response to fluid injection. The transformer model’s ability to predict both temporal and spatial evolution highlights its potential as a valuable tool in subsurface operations, offering substantial improvements in safety and efficiency.

Method: transformer neural network architecture

We employ a transformer neural network to forecast the spatiotemporal evolution of fluid-induced microearthquakes (MEQs). The attention mechanism captures dependencies in the monitoring time series, allowing the model to learn patterns across multiple temporal scales. Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture. Given a sequence of past monitoring data, the model predicts the future MEQ features. The following subsections describe data processing, network architecture, loss function, and hyperparameter tuning.

Data preprocessing: crop and normalization

We first construct training segments by sliding a growing stimulation history across the cumulative time series and advancing the forecast horizon in non-overlapping blocks. The monitoring data at discrete time index t are defined as:

where the monitoring dimension M = 6 includes hydraulic stimulation features —(1) flow rate (x1) and (2) well head pressure (x2)— and spatiotemporal MEQ features —(3) cumulative MEQ numbers (x3), (4) \(\log {M}_{0}\) (x4), (5) 95th percentile distance (x5), (6) 50th percentile distance)(x6).

The cropping procedure is controlled by two hyperparameters. The minimum history length \({l}_{\min }\) specifies the number of monitoring samples always available, and the forecast horizon lfuture specifies how many future steps are predicted at once. For a monitoring ending at tend, the number of segments is

For each segment index k ∈ {0, . . . , N − 1} the split time is set as

Thus, the cumulative monitoring input (X(k)) and the subsequent forecast window (Y(k)) are defined as:

where F = 4 corresponds to the forecasting MEQ features: (1) cumulative MEQ count, (2) \(\log {M}_{0}\), (3) P95, and (4) P50. Each successive segment index k advances the split by lfuture, ensuring that the predicted time blocks Y(k) are non-overlap and contiguous, while the input window grows monotonically. This approach yields continuous, leakage-free forecasting segments that can be applied in real time once at least \({l}_{\min }\) monitoring have been acquired (Fig. 4).

To fairly normalize the data without information leakage from future steps, normalization is applied individually to each input window X(k). For each monitoring dimension m ∈ {1, . . . , M} and each segment k, we define the normalization using only the known input window as follows:

The normalization parameters obtained from each input window X(k) are then consistently applied to scale the corresponding forecast window Y(k). This ensures that normalization relies exclusively on information available at the prediction time, thus avoiding any data leakage from future observations.

Neural network architecture

Our transformer neural network architecture employs a multi-head attention mechanism designed to effectively capture temporal dependencies from variable-length sequences. Given an input monitoring sequence X(k), the multi-head attention layer processes the input as follows42:

where Q = X(k)WQ, K = X(k)WK, and V = X(k)WV are the query, key, and value matrices, respectively; WQ, WK, and WV are learnable weight matrices; dk is the dimension of key vectors.

Following the attention layer, a feed-forward network (FFN)68 is applied independently to each time step. The FFN consists of two linear transformations with a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function:

where z denotes the input from the attention output, and W1, W2, b1, and b2 are learnable parameters.

To enhance training stability, layer normalization and residual connections are applied after both attention and feed-forward layers. These ensure effective gradient propagation and prevent training instabilities.

After attention and feed-forward layers, global average pooling and dense layers reduce the sequence to a single vector, producing predictions for the forecasting window Y(k). In particular, the model predicts both the mean (μ) and log-variance (\(\log {\sigma }^{2}\)) of these forecasting MEQ features to quantify prediction uncertainty:

The model is trained using the Adam optimizer69 with a heteroscedastic Gaussian negative log-likelihood (NLL) loss function70,71, augmented by a monotonicity penalty weighted by the hyperparameter (λ):

The NLL explicitly measures the discrepancy between predictions and true values, accounting for predictive uncertainty. Given the predicted mean (μpred and log-variance (\(\log {\sigma }_{\,{\mbox{pred}}\,}^{2}\)), the NLL is defined as:

where N is the number of time steps in the forecast window, F is the number of MEQ target features, and α is the hyperparameter to discourage the model from inflating variance. This formulation captures both prediction accuracy and model confidence, penalizing over- or under-confident forecasts.

To enforce non-decrease for the cumulative term forecastings, a monotonicity penalty is applied to cumulative MEQ count and cumulative logarithmic seismic moment. The penalty is defined as:

where only the selected cumulative features are included in the penalty term.

Finally, all predictions are rescaled using the inverse of the normalization applied during preprocessing. The model performance is evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2):

where Y includes the four spatiotemporal MEQ features.

Neural-network hyper-parameter tuning

The transformer model is trained to forecast spatiotemporal MEQs from hydraulic-stimulation history and past MEQ responses. While network weights are learned automatically, several settings—loss-function coefficients, architectural widths, batch size, dropout rate, and penalty weights—must be chosen by the user72,73. Supplementary Table 1 lists the values that remain fixed in every experiment.

Two coefficients are tuned by grid search: β (the variance-regularization weight inside the heteroscedastic Gaussian NLL term) and λ (the weight on the monotonic-increase penalty applied to cumulative MEQ count and cumulative seismic moment). For each forecast horizon lfuture ∈ {1, 15, 30} models are trained with β, λ ∈ {0.1, 1.0, 10.0}. Validation R2 scores identify the optimal pair (β⋆, λ⋆); the corresponding results appear in Supplementary Table 2.

Short-horizon models—forecast windows of up to fifteen seconds— achieve excellent accuracy; for example, the lfuture = 15 model reaches \({R}_{\,{\mbox{val}}\,}^{2}=0.924\). As the horizon lengthens, performance degrades: at nfuture = 30 the best model attains \({R}_{\,{\mbox{val}}\,}^{2}=0.046\). The horizon-specific models reported in Supplementary Table 2 are used for all subsequent experiments.

Data availability

The EGS Collab experiment’s stimulation data and seismic catalog are available at https://doi.org/10.15121/1651116 and https://doi.org/10.15121/1557417.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available on GitHub at https://github.com/jh-chung1/Transformer_MEQ_Forecasting.

References

Metz, B., Davidson, O., De Coninck, H., Loos, M. & Meyer, L. IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Williams, C. F., Reed, M. J., Mariner, R. H., DeAngelo, J. & Galanis, S. P. Assessment of Moderate-and High-Temperature Geothermal Resources of the United States. Technical Report (Geological Survey (US), 2008).

Bachu, S. & Adams, J. J. Sequestration of CO2 in geological media in response to climate change: capacity of deep saline aquifers to sequester CO2 in solution. Energy Convers. Manag. 44, 3151–3175 (2003).

Damen, K., Faaij, A. & Turkenburg, W. Health, safety and environmental risks of underground CO2 storage–overview of mechanisms and current knowledge. Clim. Change 74, 289–318 (2006).

Rutqvist, J. The geomechanics of CO2 storage in deep sedimentary formations. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 30, 525–551 (2012).

Yeo, I., Brown, M. R., Ge, S. & Lee, K. Causal mechanism of injection-induced earthquakes through the Mw 5.5 Pohang earthquake case study. Nat. Commun. 11, 2614 (2020).

Ellsworth, W. L., Giardini, D., Townend, J., Ge, S. & Shimamoto, T. Triggering of the Pohang, Korea, earthquake Mw 5.5 by enhanced geothermal system stimulation. Seismol. Res. Lett. 90, 1844–1858 (2019).

Wang, C.-Y., Manga, M., Shirzaei, M., Weingarten, M. & Wang, L.-P. Induced seismicity in Oklahoma affects shallow groundwater. Seismol. Res. Lett. 88, 956–962 (2017).

Rajesh, R. & Gupta, H. K. Characterization of injection-induced seismicity at north central Oklahoma, USA. J. Seismol. 25, 327–337 (2021).

Johann, L., Shapiro, S. A. & Dinske, C. The surge of earthquakes in Central Oklahoma has features of reservoir-induced seismicity. Sci. Rep. 8, 11505 (2018).

Hincks, T., Aspinall, W., Cooke, R. & Gernon, T. Oklahoma’s induced seismicity strongly linked to wastewater injection depth. Science 359, 1251–1255 (2018).

Manga, M., Wang, C.-Y. & Shirzaei, M. Increased stream discharge after the 3 September 2016 Mw 5.8 Pawnee, Oklahoma earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 11–588 (2016).

Fiori, R., Vergne, J., Schmittbuhl, J. & Zigone, D. Monitoring induced microseismicity in an urban context using very small seismic arrays: the case study of the Vendenheim EGS project. Geophysics 88, WB71–WB87 (2023).

Shapiro, S. A. Fluid-Induced Seismicity (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Boyet, A., Vilarrasa, V., Rutqvist, J. & De Simone, S. Forecasting fluid-injection induced seismicity to choose the best injection strategy for safety and efficiency. Philos. Trans. A 382, 20230179 (2024).

Lu, J. & Ghassemi, A. Coupled thermo–hydro–mechanical–seismic modeling of EGS collab experiment 1. Energies 14, 446 (2021).

McClure, M. W. & Horne, R. N. Investigation of injection-induced seismicity using a coupled fluid flow and rate/state friction model. Geophysics 76, WC181–WC198 (2011).

Zhai, G., Shirzaei, M., Manga, M. & Chen, X. Pore-pressure diffusion, enhanced by poroelastic stresses, controls induced seismicity in Oklahoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 16228–16233 (2019).

Kumazawa, T. & Ogata, Y. Nonstationary ETAS models for nonstandard earthquakes. Ann. Appl. Stat. 8, 1825–1852 (2014).

Ritz, V. A. et al. Pseudo-prospective forecasting of induced and natural seismicity in the Hengill geothermal field. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 129, e2023JB028402 (2024).

Hainzl, S. & Ogata, Y. Detecting fluid signals in seismicity data through statistical earthquake modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 110, B05S07 (2005).

Kumazawa, T. & Ogata, Y. Quantitative description of induced seismic activity before and after the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake by nonstationary ETAS models. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 118, 6165–6182 (2013).

Petrillo, G., Kumazawa, T., Napolitano, F., Capuano, P. & Zhuang, J. Fluids-triggered swarm sequence supported by a nonstationary epidemic-like description of seismicity. Seismol. Res. Lett. 95, 3207–3220 (2024).

Aochi, H., Maury, J. & Le Guenan, T. How do statistical parameters of induced seismicity correlate with fluid injection? case of oklahoma. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92, 2573–2590 (2021).

Qin, Y., Chen, T., Ma, X. & Chen, X. Forecasting induced seismicity in Oklahoma using machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 12, 9319 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Application of machine learning, deep learning and optimization algorithms in geoengineering and geoscience: comprehensive review and future challenge. Gondwana Res. 109, 1–17 (2022).

Chung, J., Ahmad, R., Sun, W., Cai, W. & Mukerji, T. Prediction of effective elastic moduli of rocks using graph neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 421, 116780 (2024).

Camps-Valls, G., Tuia, D., Zhu, X. X. & Reichstein, M. Deep Learning for the Earth Sciences: A Comprehensive Approach to Remote Sensing, Climate Science and Geosciences (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

Maniar, H., Ryali, S., Kulkarni, M. S. & Abubakar, A. Machine-learning methods in geoscience. In Proc. SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, SEG–2018 (SEG, 2018).

Bergen, K. J., Johnson, P. A., de Hoop, M. V. & Beroza, G. C. Machine learning for data-driven discovery in solid earth geoscience. Science 363, eaau0323 (2019).

Yu, S. & Ma, J. Deep learning for geophysics: current and future trends. Rev. Geophys. 59, e2021RG000742 (2021).

Mousavi, S. M. & Beroza, G. C. Deep-learning seismology. Science 377, eabm4470 (2022).

Zhu, W. & Beroza, G. C. PhaseNet: a deep-neural-network-based seismic arrival-time picking method. Geophys. J. Int. 216, 261–273 (2019).

Reichstein, M. et al. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven earth system science. Nature 566, 195–204 (2019).

Anikiev, D. et al. Machine learning in microseismic monitoring. Earth-Sci. Rev. 239, 104371 (2023).

Jinqiang, W., Basnet, P. & Mahtab, S. Review of machine learning and deep learning application in mine microseismic event classification. Min. Miner. Depos. 15, 19–26 (2021).

Mousavi, S. M., Horton, S. P., Langston, C. A. & Samei, B. Seismic features and automatic discrimination of deep and shallow induced-microearthquakes using neural network and logistic regression. Geophys. J. Int. 207, 29–46 (2016).

Li, Z., Eaton, D. W. & Davidsen, J. Physics-informed deep learning to forecast m^ max during hydraulic fracturing. Sci. Rep. 13, 13133 (2023).

Yu, P. et al. Crustal permeability generated through microearthquakes is constrained by seismic moment. Nat. Commun. 15, 2057 (2024).

Mital, U., Hu, M., Guglielmi, Y., Brown, J. & Rutqvist, J. Modeling injection-induced fault slip using long short-term memory networks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16, 4354–4368 (2024).

Hummel, N. & Shapiro, S. A. Nonlinear diffusion-based interpretation of induced microseismicity: A Barnett shale hydraulic fracturing case study. Geophysics 78, B211–B226 (2013).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017).

Zeng, A., Chen, M., Zhang, L. & Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 37, 11121–11128 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Informer: beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 35, 11106–11115 (2021).

Schoenball, M. et al. Creation of a mixed-mode fracture network at mesoscale through hydraulic fracturing and shear stimulation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2020JB019807 (2020).

Fu, P. et al. Close observation of hydraulic fracturing at EGS Collab Experiment 1: fracture trajectory, microseismic interpretations, and the role of natural fractures. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB020840 (2021).

Kneafsey, T. J. et al. An overview of the EGS Collab project: field validation of coupled process modeling of fracturing and fluid flow at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, Lead, SD. In Proc. 43rd Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, vol. 2018 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Qin, Y. et al. Source mechanism of khz microseismic events recorded in multiple boreholes at the first EGS Collab Testbed. Geothermics 120, 102994 (2024).

Feng, Z. et al. Monitoring spatiotemporal evolution of fractures during hydraulic stimulations at the first EGS collab testbed using anisotropic elastic-waveform inversion. Geothermics 122, 103076 (2024).

Kneafsey, T. J. et al. EGS Collab project: status and progress. In Proc. 44th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering (Stanford University, 2019).

Kneafsey, T. J. et al. The EGS Collab project: learnings from experiment 1. In Proc. 45th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, 10–12 (Stanford University 2020).

Rothert, E. & Baisch, S. Passive seismic monitoring: mapping enhanced fracture permeability. In Proc. World Geothermal Congress 25–29 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2010).

Baisch, S., Vörös, R., Weidler, R. & Wyborn, D. Investigation of fault mechanisms during geothermal reservoir stimulation experiments in the Cooper Basin, Australia. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 99, 148–158 (2009).

Li, Z., Elsworth, D., Wang, C. & EGS-Collab. Induced microearthquakes predict permeability creation in the brittle crust. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1020294 (2022).

Kneafsey, T. et al. The EGS Collab project: Outcomes and lessons learned from hydraulic fracture stimulations in crystalline rock at 1.25 and 1.5 km depth. Geothermics 126, 103178 (2025).

Witherspoon, P. A., Wang, J. S., Iwai, K. & Gale, J. E. Validity of cubic law for fluid flow in a deformable rock fracture. Water Resour. Res. 16, 1016–1024 (1980).

Ouyang, Z. & Elsworth, D. Evaluation of groundwater flow into mined panels. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstracts, 30, 71–79 (1993).

Morris, J. P. et al. Experimental design for hydrofracturing and fluid flow at the DOE EGS collab testbed. In Proc. ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, ARMA–2018 (ARMA, 2018).

Olson, J. E. Sublinear scaling of fracture aperture versus length: an exception or the rule? J Geophys Res. Solid Earth 108, 2413 (2003).

Ishibashi, T., Watanabe, N., Asanuma, H. & Tsuchiya, N. Linking microearthquakes to fracture permeability change: the role of surface roughness. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 7486–7493 (2016).

Chen, Z., Ma, M., Li, T., Wang, H. & Li, C. Long sequence time-series forecasting with deep learning: a survey. Inf. Fusion 97, 101819 (2023).

Nie, Y., Nguyen, N. H., Sinthong, P. & Kalagnanam, J. A time series is worth 64 words: long-term forecasting with transformers. arXiv preprint. (2022).

Lengliné, O. et al. The largest induced earthquakes during the geoven deep geothermal project, Strasbourg, 2018–2022: from source parameters to intensity maps. Geophys. J. Int. 234, 2445–2457 (2023).

Giuliari, F., Hasan, I., Cristani, M. & Galasso, F. Transformer networks for trajectory forecasting. In Proc. 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 10335–10342 (IEEE, 2021).

Gischig, V. S. Rupture propagation behavior and the largest possible earthquake induced by fluid injection into deep reservoirs. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7420–7428 (2015).

Bhattacharya, P. & Viesca, R. C. Fluid-induced aseismic fault slip outpaces pore-fluid migration. Science 364, 464–468 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Contiformer: continuous-time transformer for irregular time series modeling. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36 (2024).

Svozil, D., Kvasnicka, V. & Pospichal, J. Introduction to multi-layer feed-forward neural networks. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 39, 43–62 (1997).

Kingma, D. P. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980 (2014).

Nix, D. A. & Weigend, A. S. Estimating the mean and variance of the target probability distribution. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’94), vol. 1, 55–60 (IEEE, 1994).

Lakshminarayanan, B., Pritzel, A. & Blundell, C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty estimation using deep ensembles. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vol 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Feurer, M. & Hutter, F. Hyperparameter optimization. Automated Machine Learning: Methods, Systems, Challenges 3–33 (Springer, 2019).

Yang, L. & Shami, A. On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: theory and practice. Neurocomputing 415, 295–316 (2020).

Acknowledgements

J.C. gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ingenuity: Next Generation Nuclear Waste Disposal Internship program, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Nuclear Energy, and Office of Spent Fuel and Waste Disposition. This work was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), the Office of Nuclear Energy, Spent Fuel and Waste Science and Technology Campaign, and by the US Department of Energy (DOE), under Contract Number DE-AC02-05CH11231 with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. C. Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Review and editing. M. M. Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Review and editing. T. K. Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Review and editing. T. M. Investigation, Supervision, Review and editing. M. H. Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Marisol Monterrubio-Velasco and Joe Aslin. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, J., Manga, M., Kneafsey, T. et al. Deep learning forecasts the spatiotemporal evolution of fluid-induced microearthquakes. Commun Earth Environ 6, 643 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02644-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02644-z

This article is cited by

-

Coupled processes in fractured media: a key to the energy transition

GeoEnergy Communications (2025)