Abstract

Geochemical traces of past environments are preserved in the geological record. Although secondary processes often erase this information, fluid inclusions in hydrothermal minerals act as time capsules for reconstructing the evolution of Earth’s atmosphere and oceans, including the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). Here, we summarize decades of insights from analyses of ancient fluids in hydrothermal minerals worldwide. These geochemical constraints illuminate the formation of the atmosphere, its evolution through volcanism, escape to space, and subduction. Reconstructions of past atmospheric noble gas and nitrogen compositions, along with ocean salinity, reveal major steps in our planet’s evolution. They shed unique light on long-standing questions, including Earth’s climate under a faint young Sun, the missing Xe paradox, the cause and timing of oxygenation, the emergence of continents, and the flourishing of life. A refined understanding of the physical mechanisms driving xenon isotopic evolution prior to the GOE may further constrain links between early solar activity and early environmental changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geofluids (waters, hydrocarbons, supercritical fluids, volatile gases) play a crucial role in many geological processes, ranging from molecular-scale fluid-rock reactions to global tectonics, and biological activity within Earth’s crust1. Fluid inclusions represent remnants of ancient geofluids that have been trapped in hydrothermal minerals (e.g., quartz, baryte). These hydrothermal minerals are typically found in so-called epithermal veins (low to intermediate temperature hydrothermal systems) formed by the intrusion of mineralizing fluids through volcanic, sedimentary, or intrusive units within shallow crustal levels. The distribution of fluid inclusions in hydrothermal minerals depends on several factors, including crystal growth, deformation, and post-crystallization processes. In particular, populations of primary fluid inclusions (formed during crystal growth) are typically aligned along growth zones, trapped in clusters or isolated within the mineral lattice, whereas secondary inclusions preferentially form along healed fractures or microcracks after the mineral has crystallized. Analyzing these inclusions thus provides invaluable information about the geological processes and paleoenvironments in which the minerals formed (e.g., temperature, pressure, and composition). Basically, the volatile element concentrations in any fluid at equilibrium with a gas phase are primarily controlled by Henry’s law, where the concentration of a dissolved gas depends on the partial pressure of the gas times a solubility coefficient, which is a function of temperature and salinity2. For example, recent analytical developments have demonstrated that Henry’s law can be applied to dissolved noble gas concentrations in fluid inclusions from speleothems to reconstruct the cave temperature evolution on millennial timescales, with key implications for paleoclimate studies3,4. Fluid inclusions trapped within hydrothermal minerals (e.g., quartz or barite), however, display much more complex histories, with multiple sources and potentially multiple generations of fluid inclusions. Fluid inclusions can be primary, if they were introduced during the formation of the host rocks, or secondary, if they were trapped during subsequent geological events5. Assessing the history of these geofluids and understanding the paleoenvironmental information they contain thus invariably requires identifying the timing of formation, the nature, and the composition of their multiple components. In the case of contributions from multiple generations of fluid inclusions, identifying the endmember compositions can be achieved through step-crushing or multiple sample analysis by recognizing chemical and isotopic correlations involving key geochemical tracers (Box Fig. 1).

Elemental ratios (e.g., N2/Ar) may be fractionated by various processes during fluid inclusion formation, presenting a significant challenge in reconstructing the elemental ratios of the paleo-atmospheric component. Importantly, however, isotope fractionation resulting from differences in the solubility of various isotopes is minimal compared to the typical precision of mass spectrometers6. As a consequence, the isotope composition of dissolved gases is considered representative of the environment in which the paleofluids circulated. This isotope composition is thus recorded during the formation of fluid inclusions and preserved over geological time (Box Fig. 1). In addition, secondary isotopes (e.g., 40Ar, 136Xe) have been/are still being produced in situ by radiogenic and fissiogenic reactions or inherited from paleofluids that circulated through the Earth’s crust7. The magnitude of these excesses, relative to isotopes that are not significantly produced by secondary processes (e.g., 36Ar, 130Xe), can be quantified and potentially used as a tool to date the fluid inclusions (e.g., Ar-Ar geochronology8) and place time constraints on reconstructed paleoenvironments.

Over the past decades, many studies have attempted to peer through the veil of volatile compositions in fluid inclusions in hydrothermal minerals worldwide to reconstruct the evolution of Earth’s atmosphere and oceans over time, including major events such as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE), around 2.4 to 2.0 billion years ago9,10. As of today, the cause(s) and exact timing of the GOE remain debated11. The appearance of oxygenic photosynthesis, the reduction of methanogen activity, and drastic changes in tectonic activity (including continent weathering rates) and volcanic activity are all factors that could have contributed to or modulated the rise of O2 in the atmosphere, whether it occurred gradually or suddenly12. Over geological time, the composition of the atmosphere results from a balance between outgassing of the solid Earth (mantle and crust) and ingassing into the solid Earth via subduction13,14. While volcanoes are a major pathway for outgassing, especially for CO2, other volatiles—including noble gases—are also significantly released to the atmosphere during cryptic degassing, erosion, and metamorphic processes15. In a net outgassing regime, the inventories of volatiles at Earth’s surface (assuming no escape to space) will increase with time. Varying the inventories of nitrogen and halogens at Earth’s surface could, for example, have implications for the total atmospheric pressure and ocean salinity, respectively, with key implications for the climate and the development of life. Because the isotopic and elemental composition of the degassing mantle is distinct from that of Earth surface, the composition of the atmosphere and oceans is also expected to change through time15. Unraveling the timing and extent of these changes in the volatile content of the Earth's surface inventory has implications for understanding long-term interactions between our planet’s interior and surface, and their implications for the evolution of surface environments. In this contribution, we summarize the wealth of information that has been gained from the analysis of fluid inclusions trapped in ancient minerals on the formation and evolution of our planet’s atmosphere and oceans, ultimately leading to the establishment of a hospitable environment for life.

Noble gases

Noble gases are considered inert under most terrestrial conditions, meaning they are not influenced by chemical or biological processes. Under ionized conditions or at high temperature/high pressure in the deep Earth, however, the enhanced reactivity of heavy noble gases (especially Xe) makes it possible for these elements to be incorporated into molecules and mineral phases16,17. Under neutral ambient conditions at Earth’ surface, the concentrations and isotope compositions of noble gases dissolved in paleo-fluids are controlled solely by physical and nuclear processes, which can be modeled and quantified18. Although the lightest noble gases, helium and sometimes neon19, have shown a propency for diffusive loss, fluid inclusions are generally retentive of heavier noble gases, including argon, krypton, and xenon.

Atmospheric xenon isotopes as a tracer of Earth’s surface oxidation

One of the most remarkable observations that has come from the analysis of noble gases contained in fluid inclusions trapped in ancient minerals is that Archean atmospheric Xe presents an isotopic composition intermediate between the one of modern atmospheric xenon and that of xenon from planetary precursors referred to as U-Xe20,21,22,23,24 (Fig. 1). When combined together, ancient atmospheric Xe data point towards a global and protracted evolution of atmospheric Xe isotopes via mass-dependent fractionation (MDF, i.e., a process by which isotopes of an element are separated or fractionated according to their mass differences), presumably from the Hadean until the late Archean25. In contrast, Kr isotope signatures in ancient atmosphere samples have consistently been found to be indistinguishable from modern composition. To have a higher degree of MDF for Xe despite Kr being a lighter element is unexpected, suggesting that a Xe-specific process is required to account for atmospheric Xe MDF throughout the Archean. Because Xe has a low ionization threshold (12.13 eV) relative to the other noble gases (e.g., 15.76 and 14.00 eV for Ar and Kr, respectively; making it easier to remove an electron from its outermost shell), atmospheric Xe could have been readily ionized by enhanced ultraviolet radiation. Ionized Xe could then have then been being dragged along open magnetic field lines and lost to space via ionic coupling with escaping H+26 or becoming trapped in organic hazes possibly formed within the CH4-rich early atmosphere27. One major challenge of this atmospheric Xe escape model is that vertical atmospheric transfer is required to sustain the upward transport of Xe ions through the molecular ionosphere to the base of the outflowing hydrogen corona and to maintain Xe escape26. The nature and timescales of the mechanisms driving such vertical transfer remain to be described. While the exact mechanisms behind Xe isotope evolution over time are still being explored, it is understood that this evolution was global, prolonged, and reflects long-term atmospheric changes.

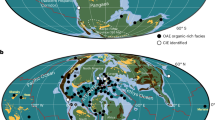

a The isotopic evolution of atmospheric Xe is shown along with the evolution of mass-independent sulfur isotope signals (MIF), and atmospheric oxygen concentration. This evolution of atmospheric Xe has been primarily derived from the analysis of fluid inclusions in hydrothermal minerals22. Whether the evolution of atmospheric Xe was continuous or occurred in steps remains debated24. b Time evolution of the deficit of 129Xe (Δ129Xe) in ancient atmospheric gases relative to the modern atmosphere, compared to petrological estimates of mantle potential temperature (TP) for non-arc lavas60. Recent reanalysis of the 3.3 Gyr-old Barberton quartz revealed no apparent 129Xe deficit (see gray dot noted with a question mark), indicating that more data is needed to assess the magnitude and timing of Δ129Xe evolution in the ancient atmosphere43.

Variations in atmospheric Xe isotopes through the Archean period appear to have stopped around the GOE, similar to sulfur mass-independent fractionation (S-MIF) signals25. Although it is not possible to firmly establish whether Xe isotope evolution followed a linear, exponential, or power law decay throughout the Archean23, these variations may provide insights into past history of continental crust build up28 and ancient levels of oxygen (O2), methane (CH4), and hydrogen (H2) in the atmosphere29. In particular, the Xe isotope trend is thought to relate to how much hydrogen escaped from Earth, serving as a potential indicator of Earth’s overall oxidation over time30. The progressive mass fractionation of xenon is best explained by xenon being dragged into space by escaping hydrogen during the Hadean and Archean eons26. Xenon ions could have been carried away by hydrogen escaping Earth’s atmosphere through strong polar winds, which required significant hydrogen from CH4 and/or H2 in the lower atmosphere. As such, the isotopic evolution of atmospheric Xe serves as a direct proxy for hydrogen escape from early Earth, a process that would tend to oxidize Earth’s surface30, until the rise of free atmospheric O225,29. Models also suggest that at least 1% of total hydrogen (e.g., stored in H2 and CH4) must have been present to facilitate xenon escape26. Considering independent constraints that set an upper limit of 10-2 bar for the partial pressure of H2, this suggests that a significant portion of hydrogen was stored in methane30,31. Crucially, this Xe escape scenario is only possible in an anoxic atmosphere, as oxygen-rich (oxic) air destroys H2 and CH4, reducing the hydrogen needed to drag xenon out of the atmosphere. Additionally, in an oxygen-rich environment, O2 would remove Xe ions through efficient resonant charge exchange reactions26.

According to recent modeling by Zahnle et al.26, the prolonged period of Xe escape suggests that, if this process were constant, Earth would have lost hydrogen equivalent to at least one ocean’s worth of water, roughly divided between the Hadean and Archean eons. These authors concluded that Xe escape must have rather occurred through small openings or in brief episodes, which appears consistent with growing evidence that Xe escape was not a continuous process24. Although the characteristics of Earth’s magnetic field during the Hadean and Archean eons remain uncertain32, one possibility is that Xe escape was confined to polar regions due to opening of the geomagnetic field, driven by sporadic bursts of intense solar activity, restricted to short periods with abundance hydrogen, or a combination of all these factors. Although the exact mechanism (or combination of mechanisms) controlling atmospheric Xe escape from the ancient atmosphere remains to be understood, the isotopic evolution of atmospheric Xe could represent a new geochemical proxy of past solar activity and geomagnetic field variations, which both remain largely uncertain33,34. Interestingly, atmospheric xenon on Mars also presents a mass-dependent enrichment in heavy Xe isotope35. The extent of Xe isotope fractionation in the Martian atmosphere (2.5%/amu relative to a solar initial composition) has long been considered smaller than that on Earth (~3.8%/amu relative to U-Xe36). However, more recent estimates of present-day terrestrial atmospheric Xe isotope fractionation, relative to its initial precursor, revise this value down to 2.6%/amu, comparable to that of Mars37. It was historically proposed that Earth could have formed from Mars-like embryos, and that certain characteristics of the present-day atmosphere (e.g., atmospheric Xe isotope fractionation) could reflect processes that occurred on these early building blocks38. However, measurements of trapped Martian atmospheric xenon in Martian meteorites also suggest that the isotopic fractionation of atmospheric xenon was still ongoing 4.4 Ga ago, but that the final amplitude was established as soon as 4.1–4.2 Gyr ago39. Recently, Shorttle et al.40 proposed that energetic collisions that happened on early Mars (200–300 Ma after solar system formation) were powerful enough to drive atmospheric escape of xenon. It remains unknown if this process was also efficient on the Hadean Earth. Zahnle et al.26 also noted that the relative Xe depletion differs between the two planets, with Xe in the Martian atmosphere being ~50% less depleted than in Earth’s atmosphere. This suggests that the Xe escape process operated differently on the two planets, and that gravity is not the dominant factor in atmospheric escape (as Mars, being smaller, would be expected to have lost more Xe). Instead, this points to a non-thermal escape process involving ion loss. As detailed below, the scenario of atmospheric Xe escape is consistent with the fact that Earth’s atmosphere has a Xe/Kr ratio that is 10 to 20 times lower than expected from its cosmochemical precursors, suggesting selective Xe loss21,22,41,42,43.

Missing atmospheric Xenon

Over the past decades, several hypotheses have been proposed to account for the apparent missing Xe via sequestration into various terrestrial reservoirs (including shales44, ice45, the continental crust46, and the Earth’s mantle28,47 and/or core48; Box 2). However, these hypotheses face great challenges in accounting for the depletion of Xe relative to Kr in Earth’s atmosphere and, most critically, the isotopic evolution of atmospheric Xe throughout the Archean (Fig. 1). That the analysis of noble gases trapped in Archean rocks revealed no significant evolution in atmospheric Kr isotopes over time is consistent with the fact that only Xe eventually went missing49.

Atmospheric isotopes can be fractionated by escape to space due to differences in mass between isotopes, which affect how they interact with physical processes that drive escape. In the case of thermal escape (also referred to as Jeans Escape50), lighter isotopes, having lower mass, can reach the escape velocity of a planet more easily than heavier isotopes. In the upper atmosphere, where gas particles have higher kinetic energy, lighter isotopes are more likely to achieve the velocity needed to escape the planet’s gravitational pull. Over time, this selective escape process leads to the fractionation of isotopes, with a higher proportion of lighter isotopes being lost to space. Non-thermal escape mechanisms refer to processes for which charged particles are involved, like photochemical reactions, solar wind interactions, and polar outflow51, which can also cause isotope fractionation. During periods of intense solar radiation, hydrogen escape can create a drag effect, pulling along heavier isotopes in a process known as hydrodynamic escape. However, lighter isotopes still tend to escape more efficiently due to their lower mass. All these mechanisms cause the remaining atmosphere to become rich in heavier isotopes, while lighter isotopes become relatively depleted, resulting in isotopic fractionation. Thus, explaining the Xe isotope fractionation in the ancient atmosphere, while not observing isotopic fractionation in lighter noble gases through conventional atmospheric escape processes, presents a significant and complex challenge.

Unlike lighter Ar and Kr, Xe is easily ionized by solar UV or charge exchange with H+ ions, so Xe+ can be dragged out to space by escaping H+ ions without significantly affecting atmospheric Kr. Unlike Xe, Kr ions are neutralized by reaction with H252, therefore explaining the lack of Kr isotope fractionation in the ancient atmosphere. As such, the scenario of atmospheric Xe escape to space provides a straightforward explanation for the longstanding missing Xe paradox42. Recently, noble gas data from 3.0 Gyr-old Barberton (South Africa) quartz fluid inclusions suggested that the Xe/Kr ratio was higher in the Archean than it is today43, consistent with the selective and prolonged escape of atmospheric Xe. More data is needed to establish how the Xe/Kr ratio in the atmosphere evolved over time until reaching its present-day 10- to 20-fold Xe depletion.

Tracking mantle degassing using mono-isotopic noble gas excesses

Radiogenic 40Ar has been produced within Earth’s silicate reservoirs through the radioactive decay of lithophile 40K (T1/2 = 1.25 Ga; Box 3). Earlier studies modeled the evolution of atmospheric argon’s isotopic composition (specifically the 40Ar/36Ar ratio) due to long-term degassing of radiogenic argon into the atmosphere53,54. The discovery in the late 1970s that the 400-million-year-old atmosphere had a slightly lower 40Ar/36Ar ratio than the modern atmosphere paved the way for paleo-atmospheric studies related to Earth’s mantle and geodynamics55,56. Initial data from the Archean atmosphere seemed to confirm that Earth’s crust, through potassium storage, played a significant role in modulating the atmospheric 40Ar/36Ar ratio54,57 (Fig. 2). Recently, a model coupling He, Ne, and Ar isotope systematics suggested that mantle outgassing plays a prominent role in controlling the outgassing of radiogenic 40Ar into the atmosphere, while the role of the continental crust remains minor58.

The progressive increase of the atmospheric 40Ar/36Ar ratio is attributed to the outgassing of radiogenic 40Ar from both the Earth’s mantle and crust15. The dashed line represents a recent model published by Zhang et al.58 for the evolution of atmospheric argon. Error bars (1 sigma) are contained within the symbols19,21,109,110,111,112,113. For Pujol et al.57, a possible range of values is indicated in orange. The starting composition (40Ar/36Ar~0) is hypothetical and reflects the original contribution of primordial argon (primarily 36Ar) from chondritic bodies. This inference is also supported by the chondritic-like 38Ar/36Ar ratio of the Earth’s atmosphere.

Similar to 40Ar, the mantle is enriched in 129Xe compared to the atmosphere, due to the radioactive decay of 129I during the first ~100 million years of Earth’s evolution59. Over time, volcanic gas was continuously outgassed from Earth’s interior, leading to a progressive buildup of 129Xe in Earth’s atmosphere relative to other Xe isotopes (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, a deficit relative to the modern atmospheric composition has been observed in several paleo-atmospheric samples21,23,60. The fact that this deficit appears to vanish around the time of the GOE has been tentatively attributed to an episode of extensive outgassing related to mantle evolution in the late Archean60. More data are needed to assess the magnitude and timing of the disappearance of this 129Xe deficit43.

Major element composition of the ancient atmosphere

Fluid inclusion analyses provide a unique opportunity to probe the major volatile element composition of the ancient atmosphere. However, constraining the partial pressure of ancient atmosphere gases from elemental ratio measurements in fluid inclusions is not trivial due to multi-component mixing (Box 1) and phase chemistry.

Fluid inclusion phase chemistry

While it has often been assumed that gas compositions measured from fluid inclusions can be directly interpreted as reflecting the atmospheric conditions at the time of mineral precipitation, there is growing evidence that solubility effects associated with the partitioning of volatiles between gas and aqueous phases present at the time of inclusion formation must be considered to avoid misinterpretation61. Because each gas has a different solubility in water, the composition of gaseous inclusions (e.g., trapped air bubbles) can differ markedly from that of the dissolved gases in entrapped fluids. For instance, while the modern atmosphere is composed of about 78.1% N2, 20.9% O2, 0.9% Ar, and ~420 ppm CO2, these proportions shift significantly upon dissolution in freshwater at 20 °C, yielding a composition of about 63.0% N2, 33.4% O2, 1.6% Ar, and 1.9% CO2 (Fig. 3). These proportions depend on the salinity of the fluid phase and temperature of the system, yielding about 70.3% N2, 25.7% O2, 1.8% Ar, and 2.3% CO2 for seawater-like fluids at 90 °C (Fig. 3). As a result, elemental ratios such as N2/Ar may vary from ~38 in fresh air-equilibrated water at 20°C, up to ~84 in pure air bubbles. Park & Schaller61 emphasized the importance of these considerations and proposed a robust approach using the N2/Ar as a proxy for calculating the gas volume fractions (φg; Fig. 3) at the time of entrapment, therefore allowing the observed gas ratios to be corrected to accurately reflect the composition of the atmosphere under which the fluid inclusions formed. Recent studies have also shown that estimates of the paleo-atmospheric elemental ratio can be obtained from crushing experiments on ancient hydrothermal quartz and baryte43,62, although the true Kr/Xe of the Archean atmosphere remains elusive, given the number of processes able to impart elemental fractionation62.

The resulting composition depends on the relative contribution of each endmember, governed by the gas volume fraction (φg). When φg = 1, the inclusion reflects the atmospheric composition, when φg = 0, it reflects the composition of dissolved gases in water. Theoretical trapped mole fractions of N2, O2, Ar, and CO2 are shown on (a), with the wide range of possible CO2 mole fractions shown altogether with Ar on a logarithmic y-axis. Ranges of selected elemental ratios are shown on (b). All calculations using solid lines assume 20 °C freshwater, whereas dotted lines show calculations for 90 °C seawater, for comparison.

Documenting the volatile element composition of the ancient atmosphere is key to understanding the environmental, geological, and climate events that accompanied early life evolution. One of the strongest constraints on Archean atmospheric composition is that the ground-level mixing ratio of O2 was <10−6 PAL (present atmospheric level; Fig. 1), and that the release of O2 by early cyanobacteria as a byproduct of oxygenic photosynthesis dramatically changed Earth’s atmosphere, transforming Earth’s weakly reducing, anoxic atmosphere into an oxygenated one during the GOE, ~2.5 Gyr ago. Estimates of other Archean atmospheric gas concentrations are subject to significant uncertainty, with for example CO2 and CH4 levels ranging ~10 to 2500 and 102 to 104 times modern amounts, respectively29. Interestingly, there exists an apparent contradiction between astrophysical models, which suggest that the Sun’s luminosity was about 25–30% weaker during the Archean eon and so the Archean Earth should have been frozen, and geological evidence indicating that Earth’s surface temperatures were warm enough to support liquid water and early life63. This so-called faint young sun paradox is thought to be resolved by higher concentrations of greenhouse gases (such as CO2, CH4, H2) in the early atmosphere64.

Fluid inclusions trapped in evaporites (e.g., halite) also provide an opportunity to probe the gas composition of the ancient atmosphere, up to the Neoproterozoic period65. Over the past decades, great strides have been achieved in advancing techniques of gas extraction from halite fluid inclusions (e.g., heat or cold extraction followed by mass spectrometry analyses), making it possible to increase resolution while reducing sample size requirements66. Critically, however, conservative tracers of gas-fluid partitioning (e.g., 40Ar/N261, Fig. 3) are invariably required to provide robust insights into the ancient atmosphere’s composition.

Evolution of atmospheric N2 through time

Today, N₂ is the most abundant gas in the atmosphere, reflecting the long-term evolution of Earth’s surface as a result of biological and geological processes, including mantle degassing (e.g., volcanism) and ingassing (e.g., via subduction)13. A key question is whether the partial pressure of atmospheric N2 has evolved over billion-year timescales due to the complex interplay between processes contributing to the geological nitrogen cycle. Nitrogen primarily accumulates either as atmospheric N2 or within rocks in the form of ammonium, amide, nitride, or organic nitrogen. Under typical mantle temperatures and redox conditions, volcanic gases release N2, which is chemically inert and therefore eventually enters the atmosphere. However, the current debate centers on whether the terrestrial nitrogen cycle is in a net ingassing or degassing regime, primarily because of significant uncertainties regarding the efficiency of nitrogen recycling into the mantle via subduction13,67,68.

Throughout the Phanerozoic, sedimentary C/N data suggest that the release of N₂ into the atmosphere was largely offset by nitrogen burial in organic matter, leading to minimal fluctuations in the partial pressure of nitrogen, pN269. Most models of pN2 evolution in the deeper past70,71,72,73,74,75 predict significant changes ( ± 50% of the modern value) over the 4.5 billion years of Earth’s history (Fig. 4). For the GOE and the Proterozoic, some models even suggest a near collapse of pN274, with a potential late recovery around 0.6 billion years ago75. However, only a few reliable estimates of the paleo-pN2 are available in the literature (Fig. 4). The nitrogen isotope composition of fluid inclusions in ancient rocks indicates that the 15N/14N ratio of atmospheric nitrogen at 3.3 Ga was already modern-like22,76, attesting to the inefficient escape of nitrogen via fractionating escape mechanisms since that time. Note that potential isotopic effects related to phase chemistry (i.e., difference in solubility between 15N and 14N) are minor, lower than the part per thousand (permil) level61.

For the Archean, available data suggest that the pN2 was on the same order of magnitude as or lower than the modern value. However, all models predict fluctuations of more than 50% over Earth’s history. Dramatic changes in the pN2 could have occurred after the Great Oxidation Event75, but the lack of data does not allow one to reliably test this hypothesis22,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,77,114,115.

As of today, analyses of nitrogen and argon (i.e., N2/36Ar) in fluid inclusions from Archean hydrothermal minerals suggest that the paleo-pN2 in the ancient atmosphere was similar to or lower than that of the present atmosphere at 3.3 Ga, and <1.1 bar at 3.5 to 3.0 Ga22,76,77; Fig. 5). In detail, Marty et al.76 proposed that the pN2 during the Archean was similar to the modern value. In a subsequent study, using new samples that exhibited well-defined correlations in the 40Ar/36Ar vs. N2/36Ar space, Avice et al.22 confirmed that Archean pN₂ was arguably not higher than the modern value and further suggested it may have been lower. These data do not put any stringent constraint on how low the pN₂ could have been during the Archean eon. There exist lingering uncertainties about whether a direct link can be established between the measured N2/36Ar ratio of the gas released from fluid inclusions and the “true” atmospheric N2/36Ar ratio22,76, and additional work is therefore needed to better constrain the exact pN2 of the Archean atmosphere. Due to the ubiquitous presence of a hydrothermal component rich in crustal N2 (high N2/36Ar) and radiogenic 40Ar* (high 40Ar/36Ar77), existing measurements often face difficulties in clearly determining the composition of the paleo-atmospheric endmember and the value of paleo-atmospheric pN2 (Fig. 5). For the Marty et al.76 dataset, for example, the analyzed fluid inclusions arguably represent hydrothermal fluids derived from seawate78,79. While the occurrence of air bubbles can be discarded based on the intra-ocean origin of the host minerals, a contribution from magmatic CO2 cannot be eliminated. Based on mass balance calculation, however, the N2/Ar ratio measured from fluid inclusion would still represent that of air-equilibrated water rather than a magmatic component. Future measurements on samples with a higher relative proportion of the paleo-atmospheric component19 might help determine the pN2 of the ancient atmosphere with greater precision. Analysis of clumped N280 from ancient fluid inclusions represents an analytical challenge that would offer a promising avenue for distinguishing atmospheric-derived and hydrothermal nitrogen.

Note the logarithmic scale on the y-axis. The atmospheric endmember has an estimated 40Ar/36Ar ratio of 140 ± 3057 (Fig. 2). Uncertainties are shown at 1 sigma. Two points from Marty et al.76 plot outside of the displayed abscise range and are therefore given in parenthesis. These data suggest that the partial pressure of nitrogen (pN2) in the ancient (including Archean) atmosphere was arguably not 2–3 times greater than present-day.

While N2 and Ar arguably have similar solubilities in basaltic melts (implying no significant fractionation of the N2/36Ar during mantle degassing, at least at the current mantle oxidation state81), the atmospheric N2/36Ar could have evolved through time due to the distinct recycling efficiencies of these elements during subduction. The recycling efficiencies of both elements during early subduction processes associated with Hadean and Paleoarchean plate tectonics82,83 would arguably have been low due to the high mantle temperatures (Fig. 1b). The emergence of colder, modern-style subduction (whereby a significant vertical volatile flux of surface materials to mantle depths) would have marked a pivotal shift in surface-mantle interactions84, transitioning from a purely degassing state to a balance between global degassing and ingassing (i.e., recycling13). While recycled Ar is primarily hosted in hydrated phases like serpentinites (and thus potentially lost to the mantle wedge during dehydration85), N can be retained in metasediments and peridotites due to NH4 substitution for K in phengite or N3− substitution for oxygen86,87, implying no significant loss of N by dehydration68,88. The recycling efficiencies of Ar and N into the mantle via subduction may thus differ significantly due to their distinct retention behaviors in subducted materials13. While heavy noble gas (Ar, Kr, Xe) systematics clearly suggest that substantial recycling of surface volatiles into the mantle has occurred over the past ~2–3 billion years89,90, the global recycling efficiency of nitrogen remains open to debate, and the potential for past atmospheric N2/36Ar variations remains uncertain.

Evolution of the oceans’ salinity

Determining the salinity of ancient oceans is a key objective in geosciences, as salinity significantly influences Earth’s climate91 and provides insights into the conditions under which life first emerged92 (Box 4). Kasting93 proposed that ancient ocean salinity might have been approximately 1.2 times higher than present levels, assuming that all evaporites currently located on continents were once dissolved in the oceans. However, the full extent of Precambrian evaporites remains uncertain due to poor preservation. Building on this idea, Knauth92 considered the role of brines in stratified oceans and those potentially preserved on continents, suggesting that Archean Ocean salinity may have ranged from 1.2 to 2 times that of today. Knauth92 identified evaporite formation and its isolation on continental platforms as the primary processes for decreasing ocean salinity, positing that most halogens likely remained dissolved in the oceans until major episodes of continental growth. Yet, a further mechanism for halogen removal is subduction and recycling into the mantle, as recent studies on halogen budgets in continental arc environments suggest (ref. 94 and references therein). The fluxes of halogens between the mantle, oceans, and oceanic crust are still not well understood95, making it difficult to estimate ancient ocean salinity based solely on geochemical mass balance.

Available data from fluid inclusions in Archean minerals96,97 suggest that the salinity of Archean oceans was comparable to that of modern oceans within a plausible temperature range of 0–75 °C (Fig. 6). Many geochemical proxies have been used to document the salinity and temperature of the Archean Oceans. Oxygen and silicon isotope variations in ancient cherts and organic matter suggest that Archean seawater temperatures were likely greater than modern oceans, with estimates ranging from around 55 °C to 85 °C98,99,100. Other studies have argued for more moderate ocean temperatures around 40 °C, suggesting that early life may have thrived in cooler, more temperate conditions101. In any case, fluid inclusion data appear most compatible with a modern-like salinity of the Archean oceans, compatible with conclusions from mass balance of hydrothermal activity and weathering rates10. Specifically, although the similar Br/Cl and I/Cl ratios suggest no significant changes in the ocean’s halide system between 2.5 and 3.5 billion years ago compared to modern seawater, Burgess et al.97 suggested that the ancient ocean had higher levels of bromine (Br) and iodine (I) relative to chlorine (Cl). Because iodine exhibits a strong affinity for organic matter, higher iodine concentrations in the Archean Ocean compared to today could potentially reflect reduced biological sequestration, assuming the total organic reservoir was smaller than at present. This scenario may be consistent with the elevated Br/Cl ratios observed in Archean seawater102, although the variable influence of mantle-derived hydrothermal vent inputs cannot be ruled out97.

Mixing correlations between a paleo-ocean and a crustal/hydrothermal endmember in fluid inclusions of a 3.49-Gyr-old Dresser formation, Warrawoona Group, Pilbara Craton at North Pole (Western Australia96), and b 2.5 Gyr-old chert samples from Hamersley Group (Western Australia97). a The strong linear correlation indicates two-component mixing. The red, blue, and green thick lines represent salinities of 0.5, 1, and 2 times the modern seawater composition, as expressed by Cl and K, for temperatures of 0 °C, 25 °C, 50 °C, and 75 °C. These ranges represent possible endmembers between present-day ocean bottom temperatures of 2 °C and those proposed for Archean oceans of up to 70 °C99. The correlation is not consistent with salinities twice the modern value116 or higher55,56,117. For a modern-like salinity, a temperature in the range of 20–40 °C is compatible with the data. b Only the main release steps (at 1400 or 1600 °C) from each sample are displayed here. They show Cl/36Ar values comparable to modern seawater salinity in the temperatures range 0–25 °C, but K/36Ar about two orders of magnitude higher than modern seawater, which the authors attribute to the presence of a K-rich phase97. Based on the low 40Ar/36Ar, seawater-like Cl/36Ar, and the ~2.4 Ga 40Ar–39Ar ages, the fluids are likely to be paleo-seawater containing dissolved atmospheric noble gases.

Conclusions and perspectives

-

Fluid inclusions represent invaluable time capsules that preserve geochemical information about the environmental conditions during hydrothermal mineral precipitation.

-

The original geochemical signatures of fluid inclusions may be overprinted by later events (e.g., hydrothermal circulation associated with regional metamorphism), thus calling for caution when reconstructing paleoenvironmental conditions from fluid inclusion analyses103.

-

Noble gas isotopes provide a complex yet comprehensive toolset to track both the evolution of the mantle (e.g., 129Xe deficit, evolution of atmospheric 40Ar/36Ar) and the atmosphere (e.g., time evolution of Xe isotopes via mass-dependent fractionation) through time.

-

Coupling Xe isotope analyses of ancient geological materials with models of atmospheric Xe photochemistry shall help resolve the missing Xe paradox, provided that a physical process capable of transporting Xe through the atmosphere is identified.

-

Xenon isotopes are key to tracking the evolution of hydrogen escape, with key implications for our understanding of solar activity, terrestrial magnetic field, and evolution of redox conditions at Earth’s surface (including ocean pH). The possibility that this evolution was discontinuous24 presents an intriguing opportunity to potentially reconstruct the evolution of solar activity and/or the terrestrial magnetic field over time.

-

The evolution of pN2 provides indirect constraints on past pCO2, which has significant implications for understanding major scientific questions such as the faint young sun paradox104 and the evolution of the biosphere through geological time.

-

The evolution (or lack of evolution) of ocean salinity through time has implications for the emergence of continents, the flourishing of life, and the global balance (ingassing vs. degassing) of volatile elements via subduction/volcanism.

-

Based on fluid inclusion data, the salinity and partial pressure of N₂ in the atmosphere were comparable to present-day levels during the Archean eon. These findings imply that the relative fluxes of H2O, Cl, and N2 to and from Earth’s surface reservoirs (i.e., oceans and atmosphere) have remained relatively constant since the Archean.

-

Geochemical constraints from fluid inclusion data can be considered alongside other geochemical proxies of past environmental conditions (e.g., Si isotopes in cherts99) to provide a holistic representation of early Earth. Additionally, these geochemical data must be compared with model outputs (e.g., regarding the evolution of pN2) to improve our understanding of the mechanisms controlling the evolution of Earth’s surface environments.

-

The exact composition (abundance and isotope signature) of nitrogen in the ancient atmosphere remains uncertain. Additional, high precision analyses are required. One promising avenue of investigation may be to explore the nitrogen clumped isotope composition80 of ancient atmospheric samples trapped in FIs.

-

Novel crushing techniques for fluid inclusion extraction105,106, combined with ongoing analytical developments in nitrogen and noble gas mass spectrometry107—including the emerging possibility of measuring all noble gases, and potentially nitrogen, in the same gas fractions19,76,77,108 — hold great promise for advancing the use of fluid inclusions as tiny windows into Earth’s past environments.

-

Parallel studies of the origin and evolution of atmospheres of other terrestrial planets (Venus and Mars) and remote analyses of exoplanetary atmospheres offer insights into the emergence and development of habitable conditions on other worlds.

Data availability

No new datasets were generated in this study. All data used are available in the cited literature.

References

Fyfe, W. S. Fluids in the Earth’s crust: Their Significance In Metamorphic, Tectonic and Chemical Transport Process (Vol. 1). (Elsevier, 2012)

Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4399–4981 (2015).

Kluge, T. et al. A new tool for palaeoclimate reconstruction: Noble gas temperatures from fluid inclusions in speleothems. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 269, 408–415 (2008).

Ghadiri, E. et al. Noble gas-based temperature reconstruction on a Swiss stalagmite from the last glacial–interglacial transition and its comparison with other climate records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 495, 192–201 (2018).

Roedder, E. Volume 12: fluid inclusions. Rev. Mineral. 12, 644 (1984).

Seltzer, A. M., Shackleton, S. A. & Bourg, I. C. Solubility equilibrium isotope effects of noble gases in water: theory and observations. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 9802–9812 (2023).

Ballentine, C. J. & Burnard, P. G. Production, release and transport of noble gases in the continental crust. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 481–538 (2002).

Turner, G. Hydrothermal fluids and argon isotopes in quartz veins and cherts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 52, 1443–1448 (1988).

Kopp, R. E., Kirschvink, J. L., Hilburn, I. A. & Nash, C. Z. The Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth: a climate disaster triggered by the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11131–11136 (2005).

Holland, H. D. The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 361, 903–915 (2006).

Ostrander, C. M. et al. Onset of coupled atmosphere–ocean oxygenation 2.3 billion years ago. Nature 631, 335–339 (2024).

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

Bekaert, D. V. et al. Subduction-driven volatile recycling: a global mass balance. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 49, 37–70 (2021).

Gibson, S. A. & McKenzie, D. On the role of Earth’s lithospheric mantle in global volatile cycles. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 602, 117946 (2023).

Bender, M. L., Barnett, B., Dreyfus, G., Jouzel, J. & Porcelli, D. The contemporary degassing rate of 40Ar from the solid Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8232–8237 (2008).

Grochala, W. Atypical compounds of gases, which have been called ‘noble’. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 1632–1655 (2007).

Grandinetti, F. Noble Gas Chemistry: Structure, Bonding, And Gas-phase Chemistry (John Wiley & Sons, 2018)

Ballentine, C. J., & Burnard, P. G. Production, release and transport of noble gases in the continental crust. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 481–538 (2002).

Avice, G., Kendrick, M. A., Richard, A. & Ferrière, L. Ancient atmospheric noble gases preserved in post-impact hydrothermal minerals of the 200 Ma-old Rochechouart impact structure, France. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 620, 118351 (2023).

Pujol, M., Marty, B. & Burgess, R. Chondritic-like xenon trapped in Archean rocks: a possible signature of the ancient atmosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 308, 298–306 (2011).

Avice, G., Marty, B. & Burgess, R. The origin and degassing history of the Earth’s atmosphere revealed by Archean xenon. Nat. Commun. 8, 15455 (2017).

Avice, G. et al. Evolution of atmospheric xenon and other noble gases inferred from Archean to Paleoproterozoic rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 232, 82–100 (2018).

Bekaert, D. V. et al. Archean kerogen as a new tracer of atmospheric evolution: Implications for dating the widespread nature of early life. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar2091 (2018).

Almayrac, M. G., Broadley, M. W., Bekaert, D. V., Hofmann, A. & Marty, B. Possible discontinuous evolution of atmospheric xenon suggested by Archean barites. Chem. Geol. 581, 120405 (2021).

Ardoin, L. et al. The end of the isotopic evolution of atmospheric xenon. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 20, 43–47 (2022).

Zahnle, K. J., Gacesa, M. & Catling, D. C. Strange messenger: a new history of hydrogen on Earth, as told by Xenon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 244, 56–85 (2019).

Hébrard, E. & Marty, B. Coupled noble gas–hydrocarbon evolution of the early Earth atmosphere upon solar UV irradiation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 385, 40–48 (2014).

Rzeplinski, I., Sanloup, C., Gilabert, E. & Horlait, D. Hadean isotopic fractionation of xenon retained in deep silicates. Nature 606, 713–717 (2022).

Catling, D. C. & Zahnle, K. J. The Archean atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax1420 (2020).

Catling, D. C., Zahnle, K. J. & McKay, C. P. Biogenic methane, hydrogen escape, and the irreversible oxidation of early Earth. Science 293, 839–843 (2001).

Kadoya, S. & Catling, D. C. Constraints on hydrogen levels in the Archean atmosphere based on detrital magnetite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 262, 207–219 (2019).

Tarduno, J. A., Zhou, T., Huang, W. & Jodder, J. Earth’s magnetic field and its relationship to the origin of life, evolution and planetary habitability. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf082 (2025).

Lammer, H. et al. Variability of solar/stellar activity and magnetic field and its influence on planetary atmosphere evolution. Earth Planets Space 64, 179–199 (2012).

Güdel, M. The Sun through time. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 143 (2020).

Conrad, P. G. et al. In situ measurement of atmospheric krypton and xenon on Mars with Mars Science Laboratory. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 454, 1–9 (2016).

Pepin, R. O. On the isotopic composition of primordial xenon in terrestrial planet atmospheres. Space Sci. Rev. 92, 371–395 (2000).

Cassata, W. S. A refined isotopic composition of cometary xenon and implications for the accretion of comets and carbonaceous chondrites on Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 660, 119307 (2025).

Dauphas, N. & Morbidelli, A. Geochemical and planetary dynamical views on the origin of Earth’s atmosphere and oceans. Treatise Geochem. 2nd Edition https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.01301-2 (2014).

Cassata, W. S., Zahnle, K. J., Samperton, K. M., Stephenson, P. C. & Wimpenny, J. Xenon isotope constraints on ancient Martian atmospheric escape. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 580, 117349 (2022).

Shorttle, O. et al. Impact sculpting of the early Martian atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 10, eadm9921 (2024).

Pepin, R. O. Atmospheres on the terrestrial planets: clues to origin and evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 252, 1–14 (2006).

Bekaert, D. V., Broadley, M. W. & Marty, B. The origin and fate of volatile elements on Earth revisited in light of noble gas data obtained from comet 67 P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Sci. Rep. 10, 5796 (2020).

Broadley, M. W. et al. High precision noble gas measurements of hydrothermal quartz reveal variable loss rate of Xe from the Archean atmosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 588, 117577 (2022).

Bernatowicz, T. J., Podosek, F. A., Honda, M. & Kramer, F. E. The atmospheric inventory of xenon and noble gases in shales: the plastic bag experiment. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 89, 4597–4611 (1984).

Wacker, J. F. & Anders, E. Trapping of xenon in ice: implications for the origin of the Earth’s noble gases. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 2373–2380 (1984).

Sanloup, C. et al. Retention of xenon in quartz and Earth’s missing xenon. Science 310, 1174–1177 (2005).

Jephcoat, A. P. Rare-gas solids in the Earth’s deep interior. Nature 393, 355–358 (1998).

Zhu, L., Liu, H., Pickard, C. J., Zou, G. & Ma, Y. Reactions of xenon with iron and nickel are predicted in the Earth’s inner core. Nat. Chem. 6, 644–648 (2014).

Ozima, M. & Podosek, F. A. Formation age of Earth from 129I/127I and 244Pu/238U systematics and the missing Xe. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 104, 25493–25499 (1999).

Hunten, D. M., Pepin, R. O. & Walker, J. C. Mass fractionation in hydrodynamic escape. Icarus 69, 532–549 (1987).

Gronoff, G. et al. Atmospheric escape processes and planetary atmospheric evolution. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2019JA027639 (2020).

Anicich, V. G. A survey of bimolecular ion-molecule reactions for use in modeling the chemistry of planetary atmospheres, cometary comae, and interstellar clouds-1993 supplement. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 84, 215–315 (1993).

Turekian, K. K. The terrestrial economy of helium and argon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 17, 37–43 (1959).

Hamano, Y. & Ozima, M. Earth-atmosphere evolution model based on Ar isotopic data. Adv. Earth Planet. Sci. 3, 155–171 (1978).

Cadogan, P. H. Palaeoatmospheric argon in Rhynie chert. Nature 268, 38–41 (1977).

Stuart, F. M., Mark, D. F., Gandanger, P. & McConville, P. Earth-atmosphere evolution based on new determination of Devonian atmosphere Ar isotopic composition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 446, 21–26 (2016).

Pujol, M., Marty, B., Burgess, R., Turner, G. & Philippot, P. Argon isotopic composition of Archaean atmosphere probes early Earth geodynamics. Nature 498, 87–90 (2013).

Zhang, X. J., Avice, G. & Parai, R. Noble gas insights into early impact delivery and volcanic outgassing to Earth’s atmosphere: a limited role for the continental crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 609, 118083 (2023).

Caffee, M. W. et al. Primordial noble gases from Earth’s mantle: identification of a primitive volatile component. Science 285, 2115–2118 (1999).

Marty, B., Bekaert, D. V., Broadley, M. W. & Jaupart, C. Geochemical evidence for high volatile fluxes from the mantle at the end of the Archaean. Nature 575, 485–488 (2019).

Park, J. G. & Schaller, M. F. Constraints on Earth’s atmospheric evolution from a gas-aqueous partition of fluid inclusion volatiles. Gondwana Res. 139, 204–215 (2025).

Avice, G., Mißbach-Karmrodt, H., Vayrac, F., & Reitner, J. Noble gases in archean barites: precise determination of the isotopic fractionation of atmospheric xenon 3.48 Ga Ago. ACS Earth Space Chem. 6, 1367–1376 (2025).

Feulner, G. The faint young Sun problem. Rev. Geophys. 50, RG2006 (2012).

Goldblatt, C. & Zahnle, K. J. Faint young Sun paradox remains. Nature 474, E1–E1 (2011).

Blamey, N. J. et al. Paradigm shift in determining Neoproterozoic atmospheric oxygen. Geology 44, 651–654 (2016).

Blamey, N. J. Composition and evolution of crustal, geothermal and hydrothermal fluids interpreted using quantitative fluid inclusion gas analysis. J. Geochem. Explor. 116, 17–27 (2012).

Labidi, J. et al. Hydrothermal 15N15N abundances constrain the origins of mantle nitrogen. Nature 580, 367–371 (2020).

Busigny, V., Cartigny, P. & Philippot, P. Nitrogen isotopes in ophiolitic metagabbros: A re-evaluation of modern nitrogen fluxes in subduction zones and implication for the early Earth atmosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 7502–7521 (2011).

Berner, R. A. Geological nitrogen cycle and atmospheric N2 over Phanerozoic time. Geology 34, 413–415 (2006).

Johnson, B. W. & Goldblatt, C. EarthN: a new Earth system nitrogen model. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 2516–2542 (2018).

Mallik, A., Li, Y. & Wiedenbeck, M. Nitrogen evolution within the Earth’s atmosphere–mantle system assessed by recycling in subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 556–566 (2018).

Förster, M. W., Foley, S. F., Alard, O. & Buhre, S. Partitioning of nitrogen during melting and recycling in subduction zones and the evolution of atmospheric nitrogen. Chem. Geol. 525, 334–342 (2019).

Stüeken, E. E., Kipp, M. A., Koehler, M. C. & Buick, R. The evolution of Earth’s biogeochemical nitrogen cycle. Earth Sci. Rev. 160, 220–239 (2016).

Kurokawa, H., Kurosawa, K. & Usui, T. A lower limit of atmospheric pressure on early Mars inferred from nitrogen and argon isotopic compositions. Icarus 299, 443–459 (2018).

Zerkle, A. L. Biogeodynamics: bridging the gap between surface and deep Earth processes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20170401 (2018).

Marty, B., Zimmermann, L., Pujol, M., Burgess, R. & Philippot, P. Nitrogen isotopic composition and density of the Archean atmosphere. Science 342, 101–104 (2013).

Nishizawa, M., Sano, Y., Ueno, Y. & Maruyama, S. Speciation and isotope ratios of nitrogen in fluid inclusions from seafloor hydrothermal deposits at∼ 3.5 Ga. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 254, 332–344 (2007).

Foriel, J. et al. Biological control of Cl/Br and low sulfate concentration in a 3.5-Gyr-old seawater from North Pole, Western Australia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 228, 451–463 (2004).

Thébaud, N., Philippot, P., Rey, P. & Cauzid, J. Composition and origin of fluids associated with lode gold deposits in a Mesoarchean greenstone belt (Warrawoona Syncline, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia) using synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence. Contribut. Mineral. Petrol. 152, 485–503 (2006).

Yeung, L. Y. et al. Extreme enrichment in atmospheric 15N15N. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao6741 (2017).

Marty, B. Nitrogen content of the mantle inferred from N2–Ar correlation in oceanic basalts. Nature 377, 326–329 (1995).

Shirey, S. B. & Richardson, S. H. Start of the Wilson cycle at 3 Ga shown by diamonds from subcontinental mantle. Science 333, 434–436 (2011).

Keller, B. & Schoene, B. Plate tectonics and continental basaltic geochemistry throughout Earth history. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 481, 290–304 (2018).

Holder, R. M., Viete, D. R., Brown, M. & Johnson, T. E. Metamorphism and the evolution of plate tectonics. Nature 572, 378–381 (2019).

Kendrick, M. A. et al. Seawater cycled throughout Earth’s mantle in partially serpentinized lithosphere. Nat. Geosci. 10, 222–228 (2017).

Watenphul, A., Wunder, B. & Heinrich, W. High-pressure ammonium-bearing silicates: Implications for nitrogen and hydrogen storage in the Earth’s mantle. Am. Mineral. 94, 283–292 (2009).

Cartigny, P. & Marty, B. Nitrogen isotopes and mantle geodynamics: the emergence of life and the atmosphere–crust–mantle connection. Elements 9, 359–366 (2013).

Halama, R., Bebout, G. E., John, T. & Scambelluri, M. Nitrogen recycling in subducted mantle rocks and implications for the global nitrogen cycle. Int. J. Earth Sci. 103, 2081–2099 (2014).

Holland, G. & Ballentine, C. J. Seawater subduction controls the heavy noble gas composition of the mantle. Nature 441, 186–191 (2006).

Parai, R. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Xenon isotopic constraints on the history of volatile recycling into the mantle. Nature 560, 223–227 (2018).

Olson, S., Jansen, M. F., Abbot, D. S., Halevy, I. & Goldblatt, C. The effect of ocean salinity on climate and its implications for Earth’s habitability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL095748 (2022).

Knauth, L. P. Temperature and salinity history of the Precambrian ocean: implications for the course of microbial evolution. In Geobiology Objectives Concepts Perspectives 53–69 (Elsevier, 2005).

Kasting, J. F. The chemical evolution of the atmosphere and oceans. Science 226, 332–334 (1984).

Kendrick, M. A. Halogen cycling in the solid earth. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 52, 195–220 (2024).

Berner, E. K., & Berner, R. A. Global Environment: Water, Air, And Geochemical Cycles (Princeton University Press, 2012).

Marty, B., Avice, G., Bekaert, D. V. & Broadley, M. W. Salinity of the Archaean oceans from analysis of fluid inclusions in quartz. Comptes Rendus Géosci. 350, 154–163 (2018).

Burgess, R. et al. Archean to Paleoproterozoic seawater halogen ratios recorded by fluid inclusions in chert and hydrothermal quartz. Am. Mineral. 105, 1317–1325 (2020).

Knauth, L. P. & Lowe, D. R. High Archean climatic temperature inferred from oxygen isotope geochemistry of cherts in the 3.5 Ga Swaziland Supergroup, South Africa. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 115, 566–580 (2003).

Robert, F. & Chaussidon, M. A palaeotemperature curve for the Precambrian oceans based on silicon isotopes in cherts. Nature 443, 969–972 (2006).

Tartèse, R., Chaussidon, M., Gurenko, A., Delarue, F. & Robert, F. Warm Archaean oceans reconstructed from oxygen isotope composition of early-life remnants. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 3, 55–65 (2016).

Harrison, T. M. The Hadean crust: evidence from> 4 Ga zircons. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 37, 479–505 (2009).

Gutzmer, J. et al. Ancient sub-seafloor alteration of basaltic andesites of the Ongeluk Formation, South Africa: implications for the chemistry of Paleoproterozoic seawater. Chem. Geol. 201, 37–53 (2003).

Farber, K. et al. Fluid inclusion analysis of silicified Palaeoarchaean oceanic crust–A record of Archaean seawater?. Precambrian Res. 266, 150–164 (2015).

Charnay, B., Wolf, E. T., Marty, B. & Forget, F. Is the faint young Sun problem for Earth solved?. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 1–29 (2020).

Vogel, N. et al. A combined vacuum crushing and sieving (CVCS) system designed to determine noble gas paleotemperatures from stalagmite samples. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 2432–2444 (2013).

Wilske, C. et al. Mineral crushing methods for noble gas analyses of fluid inclusions. Geofluids 2023, 8040253 (2023).

Broadley, M. W., Bekaert, D. V. Noble gas mass spectrometry. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. (Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-99762-1.00097-8 2024).

Cattani, F., Avice, G., Ferrière, L. & Alwmark, S. Noble gases in shocked igneous rocks from the 380 Ma-old Siljan impact structure (Sweden): a search for paleo-atmospheric signatures. Chem. Geol. 670, 122440 (2024).

López-Martínez, M., York, D. & Hanes, J. A. A 40Ar39Ar geochronological study of komatiites and komatiitic basalts from the Lower Onverwacht Volcanics: Barberton Mountain Land, South Africa. Precambrian Res. 57, 91–119 (1992).

Hanes, J. A., York, D. & Hall, C. M. An 40Ar/39Ar geochronological and electron microprobe investigation of an Archean pyroxenite and its bearing on ancient atmospheric compositions. Can. J. Earth Sci. 22, 947–958 (1985).

Rice, C. M. et al. The geology of an early hot spring system near Rhynie, Scotland. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 152, 225–250 (1995).

Som, S. M. et al. Earth’s air pressure 2.7 billion years ago constrained to less than half of modern levels. Nat. Geosci. 9, 448–451 (2016).

Horne, J. E. & Goldblatt, C. EONS: a new biogeochemical model of Earth’s oxygen, carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen systems from the Archean to the present. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 25, e2023GC011252 (2024).

Shcheka, S. S. & Keppler, H. The origin of the terrestrial noble-gas signature. Nature 490, 531–534 (2012).

Drescher, J., Kirsten, T. & Schäfer, K. The rare gas inventory of the continental crust, recovered by the KTB Continental Deep Drilling Project. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 154, 247–263 (1998).

De Ronde, C. E., Channer, D. M. D., Faure, K., Bray, C. J. & Spooner, E. T. Fluid chemistry of Archean seafloor hydrothermal vents: Implications for the composition of circa 3.2 Ga seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 61, 4025–4042 (1997).

Weiershäuser, L. & Spooner, E. T. C. Seafloor hydrothermal fluids, Ben Nevis area, Abitibi greenstone belt: implications for Archean (∼ 2.7 Ga) seawater properties. Precambrian Res. 138, 89–123 (2005).

Marty, B. The origins and concentrations of water, carbon, nitrogen and noble gases on Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 313, 56–66 (2012).

Péron, S. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Pre-subduction mantle noble gas elemental pattern reveals larger missing xenon in the deep interior compared to the atmosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 593, 117655 (2022).

Porcelli, D. & Ballentine, C. J. Models for distribution of terrestrial noble gases and evolution of the atmosphere. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 411–480 (2002).

Knauth, L. P. Salinity history of the Earth’s early ocean. Nature 395, 554–555 (1998).

Hay, W. W. et al. Evaporites and the salinity of the ocean during the Phanerozoic: Implications for climate, ocean circulation and life. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 240, 3–46 (2006).

Weiss, R. F. The solubility of nitrogen, oxygen and argon in water and seawater. In Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 17 (Elsevier, 1970).

Park, R. K. The preservation potential of some recent stromatolites. Sedimentology 24, 485–506 (1977).

Acknowledgements

D.V.B. acknowledges funding from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grant ANR-22-CPJ2-0005-01). G.A. has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (Project ATTRACTE, grant agreement no. 101041122). B.M. also acknowledges funding from the European Union (ERC: PHOTONIS, grant 695618).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.V.B. wrote the original draft of this manuscript, which was then edited by G.A. and B.M. before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Morgan F. Schaller, Huiming Bao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alireza Bahadori and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekaert, D.V., Avice, G. & Marty, B. Fluid inclusions: tiny windows into global paleo-environments. Commun Earth Environ 6, 820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02799-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02799-9