Abstract

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence models is expanding the frontiers of weather forecasting, underscoring the need for comprehensive evaluations in specific applications to ensure their effective use and guide future development. Here we benchmark five state-of-the-art artificial intelligence models for forecasting atmospheric rivers, assessing both meteorological fields and atmospheric river-related metrics across global and regional scales. Results show that FuXi achieves the best performance at a 10-day lead time for meteorological fields and atmospheric river forecasts globally. However, regional assessments reveal that the model incorporating numerical components—NeuralGCM—performs better in predicting atmospheric river intensity. Two case studies along the North and South American coasts further highlight NeuralGCM’s superior ability to predict atmospheric river shapes and intensities at 10-day lead times. Nonetheless, accurately predicting atmospheric river landfall locations beyond one week remains a challenge, emphasizing the need for refinement of these models for region-specific forecasts in future applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Weather forecasting has long been a central focus of atmospheric science1,2,3, serving as one of its most impactful contributions to society4. It originated from the fundamental idea that the physical laws of fluid dynamics and thermodynamics could be applied to predict the future state of the atmosphere1,2. With the rapid advancement of supercomputing and improved understanding of meteorology, the initial idea has already evolved into the powerful and dominant approach known as numerical weather prediction (NWP)5. Classical NWP methods primarily combine dynamical equations to represent physical laws with semi-empirical parameterizations to account for unresolved physical processes, such as cloud formation, radiation, and precipitation6,7. Despite continuous improvements, NWP systems still face two persistent challenges: the computationally intensive process of solving partial differential equations and inherent parameterization uncertainties, both requiring substantial human and material resources to address8.

Recently, the rapid advancement of deep learning (DL) methods has positioned it as a promising alternative approach for short-term weather forecasting4,8,9,10,11. By leveraging their inherent strengths in parallel computation and self-learning capabilities, DL models can effectively address the computational and uncertainty challenges inherent in NWP systems. Once trained, these models produce forecasts with substantially reduced computational overhead. Furthermore, through backpropagation, they autonomously learn statistical representations of nonlinear relationships in unresolved physical processes, enabling more accurate modeling of complex atmospheric dynamics12. These advantages have driven a rapid succession of breakthrough models in recent years. Since 2018, European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) has pioneered the use of a toy neural network model to output the one-hour tendency of geopotential height at 500 hPa for the prediction13. The subsequent development of transformer architectures further enabled DL models to effectively capture complex meteorological patterns, yielding many famous models with high forecast accuracy4,10,11,14,15. Among them, FourCastNet, developed by NVIDIA, was the first purely data-driven global forecasting model, combining a Fourier neural operator with a vision transformer architecture to outperform the ECMWF Integrated Forecasting System (IFS)—one of the most widely used and skillful global numerical weather prediction products4,16—in key metrics11. Subsequently, various models—including PanGu from Huawei4, GraphCast from Google DeepMind9,10, and FuXi from Fudan University10, each with distinct designs—have emerged, firmly establishing artificial intelligence (AI) as a key tool for weather forecasting in human recognition. Beyond purely statistical approaches, AI methods can be integrated into numerical models to enhance physical constraints while simultaneously improving accuracy. A notable example is NeuralGCM, which employs neural networks to parameterize unresolved processes—including cloud formation, radiative transfer, precipitation, and subgrid-scale dynamics8. These achievements demonstrate that the DL methods are not only compatible with tasks traditionally performed by general circulation models but also enhance their capabilities8,17.

With AI forecast models evolving at such an unprecedented pace, systematic evaluation of them across diverse applications is essential for promoting the real-world operation3,18,19,20. ECMWF validated the AI model’s promising results against operational IFS analyses and weather observations, leading to its integration and the development of a new system, the Artificial Intelligence/Integrated Forecasting System3. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that AI models achieve superior performance in weather forecasting over the East Asia region, despite its complex local geographic profile18. Beyond standard meteorological variables, assessing forecasting accuracy for high-impact extreme weather events is particularly critical for operational weather prediction. Tropical cyclones represent one of the most widely studied and critically important weather phenomena. While tropical cyclone track, intensity, and precipitation forecasts from the AI models demonstrate promising performance compared to IFS results, notable potential for improvement remains, particularly in intensity prediction18. Moreover, these AI models are skillful in generating detailed synoptic-scale representations of cyclone structures— including cloud head positioning, warm sector morphology, and warm conveyor belt jet location—while also capturing large-scale dynamical drivers essential for rapid cyclogenesis19. Sensitivity testing of the AI model’s forecasts further demonstrates its ability to learn physically meaningful spatiotemporal relationships within the atmospheric system20.

Similar to tropical cyclones, atmospheric rivers (ARs) are weather systems strongly linked to heavy precipitation12,21. They play a key role in the global water cycle via intense moisture and energy fluxes22,23. AR corridors are estimated to account for up to 90% of the poleward moisture transport22,24, with landfall events often delivering substantial and beneficial freshwater supplies25. However, ARs are also associated with up to half of the top 2% of extreme precipitation and wind across most mid-latitude regions globally26. These high-impact events frequently trigger severe flooding and landslides, resulting in extensive property damage, casualties, and fatalities27,28,29. Given the importance of ARs, both NWP and AI-based methods have been explored for their forecasting potential. NWP models participating in the Subseasonal to Seasonal International Project have demonstrated skill in forecasting ARs with lead times of up to 14 days30,31,32,33. However, challenges remain, such as a low bias in integrated vapor transport (IVT) along coastal regions in the ECMWF model, which leads to non-negligible underestimation of AR landfall forecasts30. Efforts to gather observational data, such as the AR Reconnaissance Project, are enhancing model performance by providing detailed atmospheric structure information for assimilation34,35. In addition, AI techniques are being widely explored. A series of machine learning methods have been applied to post-process IVT output from NWP models, achieving improved forecasts36,37. More recently, purely AI-driven approaches, such as convolutional neural network-based autoencoders using AR maps as input, have demonstrated considerable skill in forecasting subsequent AR structures at the global scale38,39. Building on this, a Generative Adversarial Network–UNet model has been developed to forecast IVT, using previous IVT and horizontal wind fields at 850 hPa as inputs40. The model achieved an F1 score exceeding 0.25 for AR forecasts across lead times of 1 to 15 days, outperforming the compared NWP models. Galea and Ma41 further explored multiple DL architectures for AR forecasting and found that Vision Transformers outperformed other models across most evaluation metrics. Despite these advances, a comprehensive assessment of state-of-the-art global AI models—such as Pangu—in forecasting ARs remains critically needed but is currently lacking. In this study, we systematically evaluate the AR forecasting performance of five state-of-the-art AI models— Pangu, FourCastNet V2 (FCN2), FuXi, GraphCast, and NeuralGCM. To provide a comparative baseline from the perspective of numerical weather prediction, the Flexible Global Ocean–Atmosphere–Land System (FGOALS) model—developed by the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences—is also included in our evaluation. FGOALS is selected in part because its relatively wetter estimates may offer a useful contrast to the common underestimation of landfall IVT seen in other forecast models30,42. Our assessment examines both global and regional predictive skill, offering valuable insights into these models’ applicability for AR forecasting while highlighting current limitations to guide future improvements.

Results

Prediction of global variables

We first evaluate model performance in forecasting key variables related to moisture transport: specific humidity (\(q\)), zonal wind (\(u\)), and meridional wind (\(v\)) at 850 hPa, along with IVT. These variables at 850 hPa provide a representative measure of moisture transport, as this elevation typically coincides with the core of low-level jets43,44. All five AI models use ERA5 variables as input to generate 10-day global forecasts initialized at 00:00 UTC for each day in 2023 (see Section 4.1 in Methods). We assess forecast performance through three latitude-weighted metrics: the anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC), root mean square error (RMSE), and Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of temporal differences (see Section 4.2 in Methods).

All three metrics show that the FuXi performs best across four variables (Fig. 1). The ACC of this model gradually declines from 1 to ~0.4–0.5 over the 10-day forecast period (Fig. 1a–d), while RMSE follows a similar trend, with FuXi matching other models initially but demonstrating significant advantages beyond 5 days (Fig. 1e–h). This advantage is particularly pronounced for the horizontal wind field, where FuXi’s RMSE values are more than 1 m s−1 lower than other models at 10-day lead times (Fig. 1f, g). FuXi’s enhanced performance stems from its unique-phases architecture: FuXi-short (0–5 days) and FuXi-medium (5–10 days)10. This temporal specialization effectively mitigates the accumulating errors that typically occur during iterative AI model prediction. Following FuXi, Pangu, FCN2, and NeuralGCM constitute a secondary performance tier, all demonstrating competent forecast skills. Notably, the hybrid NeuralGCM model shows particular strength in temporal difference PCC while maintaining comparable performance to Pangu and FCN2 on the other two metrics. In contrast, GraphCast displays the most rapid forecast skill decay among all models, with q850 ACC values declining to near-zero by day 10 (Fig. 1a). The numerical model FGOALS exhibits relatively lower performance at short lead times, most notably for q850 (Fig. 1a). This underperformance is likely attributable to differences in the initial conditions—a situation that also applies to the ECMWF IFS, which relies on real-time operational analyses rather than ERA5 reanalysis data for initialization18. Discrepancies in the initial conditions may further influence the model’s subsequent evolution, as reflected by the relatively low similarity in the temporal differences between FGOALS and ERA5 (Fig. 1i–k). As a result, the performance gap between AI models and FGOALS becomes more pronounced over time, especially for horizontal wind components (Fig. 1b, c, f, g).

a–d ACC for a specific humidity at 850 hPa (q850), b Zonal wind at 850 hPa (u850), c Meridional wind at 850 hPa (v850), and d Integrated vapor transport (IVT). e–h Root mean square error (RMSE) for the same variables. i–l PCC of temporal differences for the same variables. Results from different models are denoted by different colors, as shown in the legend. Solid lines represent the mean values across all days in 2023, and shaded areas indicate the interquartile range from the 25th to 75th percentiles.

Spatial differences further reveal regions where the models exhibit obvious forecast biases. The most prominent IVT forecast errors occur over the subtropical oceans (Fig. 2), particularly in GraphCast and FGOALS (Fig. 2p, x). The biases in GraphCast are largely attributed to its underestimation of atmospheric moisture content in tropical and subtropical regions (Fig. 2m and Supplementary Fig. 1m), which in turn leads to lower IVT predictions (Supplementary Fig. 1p). In comparison, FGOALS has a wetter atmosphere background, leading to higher forecasts of q850 and IVT (Supplementary Fig. 1u, x)42. The q850 forecast errors of the FCN2 and FuXi models are mainly concentrated over high-altitude regions, such as the Tibetan Plateau and the west coast of South America, and persist from day 1 to day 10 of the forecast (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). For the other models, IVT forecast errors are primarily driven by biases in horizontal winds at 850 hPa over the mid-to-high latitudes, rather than inaccuracies in specific humidity. Temporal evaluation using mutual information (MI; see Methods 4.2)—which quantifies how much information the forecast contains about the observations45,46—further confirms the strong performance of FuXi and NeuralGCM in forecasting these variables (Fig. 3). Their superior IVT forecasts are reflected in consistently higher MI values (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), indicating that the 2023 forecast time series align more closely with observations. In contrast to RMSE evaluations, MI reveals that errors in horizontal wind forecasts are more pronounced over land than over oceans, suggesting reduced model skill in capturing the temporal variability of winds over land. This underscores a limitation of using RMSE as the loss function in DL models, as it tends to emphasize regions with large magnitudes while potentially overlooking areas of lower magnitude that may also exhibit high sensitivity and importance47. Overall, these results suggest that FuXi and NeuralGCM exhibit greater skill in forecasting meteorological variables associated with moisture transport processes.

Atmospheric river forecast skill

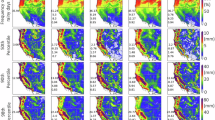

Building on the evaluation of meteorological forecasts, we further examine the models’ ability to predict ARs, which are the streams of strong moisture transport48. ARs are detected globally using the PanLu algorithm, applied to IVT fields exceeding calculated thresholds and meeting criteria for elongated geometry (see Section 4.3 in Methods). For AR frequency in 2023, errors are concentrated in hotspots over the midlatitude oceans for the models, while large relative errors arise in regions where ARs are rare, including the tropics and continental areas (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Notably, two contrasting biases emerge: GraphCast underestimates, whereas FGOALS overestimates AR frequency at forecast lead times of 5 and 10 days. A quantitative evaluation of the forecast of all ARs is then performed using a confusion matrix to assess missed events and false alarms (see Section 4.4 in Methods). Figure 4a–c separately present the precision (P), recall (R), and F1 score, which represent the probability that a forecasted AR actually occurs, the proportion of correctly forecasted ARs among all observed events, and the harmonic mean of P and R, respectively. These metrics are computed over the global grid for evaluation. Overall, the forecast performance for ARs mirrors the results for the meteorological variables discussed above: NeuralGCM and FuXi achieve the highest F1 scores, while GraphCast and FGOALS perform the worst, with the other models falling in between (Fig. 4c). FGOALS exhibits the lowest performance on the P metric (Fig. 4a), suggesting a higher likelihood of false alarms for ARs. Meanwhile, GraphCast shows the lowest performance on the R metric (Fig. 4b), indicating a greater chance of missing actual AR events. We then examine AR events where the model’s forecasts yield F1 scores below 0.5, calculated against the corresponding ERA5 events, to identify where ARs are typically misforecast (Fig. 4d–i). At a 5‑day lead time, these events account for 24.57% and 27.37% of cases for GraphCast and FGOALS, respectively, compared with 11.46% and 11.72% for FuXi and NeuralGCM. The spatial patterns are broadly similar across models, with most low-skill forecasts concentrated over the mid-latitude ocean basins, where ARs are predominantly located.

Model skill scores for AR detection: a P, b R, and c F1 score. Solid lines represent the mean values across all days in 2023, and shaded areas denote the interquartile range from the 25th to 75th percentiles. d–i Spatial distribution of ARs in forecasts with an F1 score below 0.5, calculated against corresponding events in ERA5 (indicating unsatisfactory performance), at a 5-day lead time. d Results from Pangu; the top value indicates the ratio of detected ARs to all events detected in ERA5. e–i Corresponding results for FCN2, FuXi, NeuralGCM, GraphCast, and FGOALS.

Recognizing the threat of severe precipitation and disastrous flooding from coastal ARs, we then concentrate on regions closely tied to human activities for AR forecasting49. Six regions—North America (NAM), South America (SAM), Europe (EU), South Africa (SAF), East Asia (EA), and New Zealand (NZ)—are selected for detailed regional analysis, each experiencing AR landfalls on more than 10% of days in 2023. We first calculate the AR frequency from model forecasts at different lead times for these regions. Across these models, FGOALS consistently overestimates AR frequency at 1-, 5-, and 10-day lead times across six regions (Fig. 5b). In contrast, the other AI models provide relatively accurate frequency estimates for lead times shorter than 5 days (Supplementary Fig. 8). Although the FuXi model performs well in the global AR metrics discussed earlier, it underestimates AR frequency at 6–10-day lead times across all six regions, a situation also observed in forecasts from GraphCast (Supplementary Fig. 8). At a 10-day lead, NeuralGCM does not exhibit a consistent high or low bias but maintains a relatively modest estimate, offering a comparative advantage over the other tested models. To further explore the practical application of AI models for AR forecasting, we examine their ability to accurately predict AR landfalls at various lead times. The success probabilities for all models gradually decline as lead time increases (Figs. 6a, d, g and 7a, d, g). Remarkably, FGOALS maintains the highest landfall forecast accuracy in most cases, likely due to its tendency to output higher IVT values, leading to more landfall events being detected in the forecast. Therefore, its high accuracy in landfall forecasts is also accompanied by high false alarm rates (Supplementary Fig. 9). GraphCast and FCN2 exhibit relatively low landfall forecast accuracies across the three Northern Hemisphere regions (Fig. 6a, d, g). Unexpectedly, FuXi exhibits a pronounced decline at lead times beyond 5 days, becoming one of the least accurate models, with success probabilities falling to ~20% in the NAM and EU regions and around 40% in EA.

a AR frequency along coastlines in ERA5 for 2023. Black boxes denote the location of six select regions: North America (NAM), South America (SAM), Europe (EU), South Africa (SAF), East Asia (EA), and New Zealand (NZ). b Annual AR frequency forecasts from six models at 1-, 5-, and 10-day lead times for the six regions. Gray lines indicate the AR frequency in ERA5.

a Success rates of AR landfall forecasts in NAM at 1–10 days lead time. The sector shows each model’s performance, with equally divided sectors indicating identical performance. b IVT difference between model forecasts (1-, 5-, and 10-day lead times) and ERA5 reanalysis for AR landfall events in NAM. For each model, the left half-box shows the distribution of the values, and the right half-scatter plot displays individual values. The central line in each box represents the median of the values, the box edges denote the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles), and the whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. c Intersection over union (IOU) between model forecasts and ERA5 reanalysis for AR landfall events in NAM. d–f Same as (a–c), but for EU. g–i Same as (a–c), but for EA.

a Success rates of AR landfall forecasts in NZ at 1–10 days lead time. The sector shows each model’s performance, with equally divided sectors indicating identical performance. b IVT difference between model forecasts (1-, 5-, and 10-day lead times) and ERA5 reanalysis for AR landfall events in NZ. For each model, the left half-box shows the distribution of the values, and the right half-scatter plot displays individual values. The central line in each box represents the median of the values, the box edges denote the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles), and the whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. c Intersection over union (IOU) between model forecasts and ERA5 reanalysis for AR landfall events in NZ. d–f Same as (a–c), but for SAM. g–i Same as (a–c), but for SAF.

For landfalling AR cases, we then evaluate whether their intensity and location are correctly forecast. The four purely statistical models generally underestimate AR intensity at a 10-day lead time across all six regions (Figs. 6b, e, h and 7b, e, h), with FuXi and GraphCast showing this bias most prominently. This limitation likely stems from a tendency to produce increasingly smoothed forecasts with lead time, a well-known limitation in extreme event prediction of AI methods50. Models incorporating physical processes perform better on this issue: NeuralGCM provides the most accurate estimates of AR intensity, while FGOALS tends to slightly overestimate intensity, particularly in the East Asia region (Fig. 6h). The spatial accuracy of the forecasts, measured by intersection over union (IOU), declines from ~0.8 at a 1-day lead time to 0.4 at 5 days and 0.2 at 10 days (Figs. 6c, f, i and 7c, f, i). This result highlights the limited capability of current models to accurately identify AR impact regions at longer forecast lead times. Further evaluation reveals that the P score for AR landfalls is generally higher than the recall R score across the five tested models (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11), indicating a greater likelihood of missed impact regions rather than false alarm regions in AR forecasting.

Atmospheric river forecast cases

To more intuitively demonstrate the forecasting results of the models and link statistical performance to real situations, we present two representative AR cases. Figure 8 illustrates a powerful AR event that impacted the northern Pacific coast of North America, making landfall over western Washington and Oregon in December 2023. The event was characterized by IVT values exceeding 100 kg m−1 s−1 and daily precipitation surpassing 80 mm (Supplementary Fig. 12a–c), leading to widespread flooding of homes and roadway failures51. The development of this AR was driven by a cyclone over Alaska, which generated strong westerly winds carrying substantial moisture from the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 8a). In the forecasts, all models capture this AR event reasonably well at a 1-day lead time. However, by 5 days ahead, the cyclone’s structure is poorly reproduced, particularly in the purely statistical models, where the wind direction shifts from the observed southwesterly transport to a more zonal pattern. In contrast, the hybrid and numerical models simulate the large-scale circulation pattern more accurately, likely due to their incorporation of physical constraints for the mechanisms. At a 10-day lead time, the AR appears narrower and weaker across five tested models, and in the case of GraphCast, it fails to be forecast entirely. The other three AI models—Pangu, FCN2, and FuXi—predict a landfall that is narrower and displaced southward. Their associated moisture distribution is also lower than observed in ERA5 along the coastal region. NeuralGCM demonstrates relatively better performance, more closely matching the observed location and structure of the AR.

a ERA5 reanalysis at 00:00 UTC on 5 December 2023, showing AR intensity (shading), 850-hPa horizontal winds (arrows), 850-hPa specific humidity (grids), and 850-hPa geopotential height (contours). b Pangu model forecasts at 1-, 5-, and 10-day lead times. c–g Forecasts from FCN2, FuXi, GraphCast, NeuralGCM, and FGOALS, respectively.

A second case, shown in Fig. 9, captures a zonally oriented AR event that made landfall along the Chilean coast on 23 June 2023, associated with a surface cyclone and an upper-level jet streak52. This AR event resulted in daily precipitation exceeding 100 mm in central Chile (Supplementary Fig. 12d–f), causing widespread damage and displacement. At both 1-day and 5-day lead times, all models successfully forecast the AR landfall. By 10 days, however, forecast accuracy deteriorates: the first four AI models fail to predict the AR landfall, while NeuralGCM and FGOALS perform slightly better, capturing the landfall but displacing the trajectory too far south along the South American coast. These two case studies are consistent with the statistical findings that AR forecast spatial accuracy—as measured by IOU—is still unsatisfactory at 10-day lead times. Analysis of all AR cases in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres further indicates limited model forecast skill at this lead time (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). Although the success rate of AR landfall forecasts in the Southern Hemisphere is slightly higher (Supplementary Fig. 14a), the models show no significant difference between hemispheres in predicting AR landfall intensity or area (Supplementary Fig. 14b, c). Therefore, it remains infeasible to rely solely on current AI models for accurate forecasts of precise AR landfall locations. At this stage, both intensity and spatial location are often biased, posing a non-negligible challenge for disaster prevention and early preparedness with sufficient lead time.

a ERA5 reanalysis at 00:00 UTC on 22 June 2023, showing AR intensity (shading), 850-hPa horizontal winds (arrows), 850-hPa specific humidity (grids), and 850-hPa geopotential height (contours). b Pangu model forecasts at 1-, 5-, and 10-day lead times. c–g Forecasts from FCN2, FuXi, GraphCast, NeuralGCM, and FGOALS, respectively.

Discussion

The rapid and continuous advancement of AI models is helping to redefine the upper limits of weather forecasting. Trained on massive datasets, these models typically require substantial computational resources during development—often hundreds of graphics processing units (GPUs) over several weeks, as in the case of Pangu, which used nearly 200 GPUs for half a month. Once trained, however, they could run about 10,000 times faster than NWP methods53. To fully harness the potential of these models, comprehensive evaluations across diverse systems are essential to provide researchers and practitioners with clearer and more targeted insights into their applications54. In this study, we evaluate AR forecasts generated by five state-of-the-art AI models: Pangu, FCN2, FuXi, GraphCast, and NeuralGCM. Using ERA5 reanalysis fields as input, these models generate forecasts of future atmospheric states, from which horizontal wind and specific humidity are extracted to compute IVT, and their performance is compared with that of the numerical model FGOALS. The models perform reasonably well in forecasting global meteorological variables, with the best-performing model, FuXi, achieving an ACC exceeding 0.5 within the 10-day forecast horizon. Besides, FGOALS tends to overestimate IVT, while GraphCast systematically underestimates it—a tendency also observed in other AI models, though to a lesser extent. As a result, FGOALS shows a higher rate of false alarms, whereas GraphCast exhibits a lower probability of detecting future AR events. When focusing on key AR hotspot land regions with high societal impacts, model performance deteriorates compared to the global averages. Forecasts from the purely statistical AI models exhibit lower AR landfall probabilities and consistently underestimate the intensity of landfalling AR events—a common limitation of AI models stemming from their tendency to produce overly smoothed forecasts. Although FGOALS shows a higher success rate in forecasting AR landfalls, it is also accompanied by a higher false alarm rate due to overestimation of IVT. In contrast, NeuralGCM performs much better in the intensity forecast across all six selected regions. The two case studies along the North and South American coasts further illustrate the reasonable skill of NeuralGCM in forecasting AR shapes at a 10-day lead time. This highlights the advantage of the hybrid approach, which combines statistical learning with physical laws to more effectively capture both large-scale atmospheric motions and subgrid-scale processes at longer lead times. Insights from such strategies may inform improvements in physical parameterizations in numerical models like FGOALS, helping to mitigate issues such as excessive wetting in simulations. However, even in the best-performing models—as evidenced by both case-specific and statistical evaluations—accurately predicting the precise location of AR landfalls at extended lead times remains a major challenge for current AI models.

Given the existing limitations of the models, post-processing methods can offer further optimization when applying their outputs across different regions by accounting for region-specific model characteristics. A similar strategy is commonly applied to general circulation models, where systematic biases between observed and simulated variables are identified and corrected using statistical or dynamical techniques, such as quantile mapping, nonstationary probabilistic matching, or numerical simulation55,56,57. In addition, downscaling approaches—such as regional climate models or AI techniques like generative diffusion models—can further refine large-scale fields by reducing biases and generating high-resolution results, down to the 10-km scale58. In the same vein, global AI forecasting models can also be calibrated to provide more accurate, region-specific weather predictions. For instance, the Pangu model can be used to drive the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model, enabling more reliable and accurate predictions of typhoon intensity59. It has also been shown that combining GraphCast forecasts with WRF-based downscaling produces results comparable to those guided by operational products in capturing the windstorm extremes associated with the Marshall Fire60. In addition, post-processing methods for correcting weather forecasts can be designed to incorporate seasonal and interannual variability for regions16,61, which are not accounted for by current AI models. The omission of these factors may contribute to variations in forecast accuracy across certain timescales. This again highlights the effectiveness of combining statistical and dynamical approaches, as demonstrated by NeuralGCM, in improving weather forecasts. The burgeoning emergence and advancement of AI methods, together with the robust foundations of numerical models, could pave the way toward increasingly accurate AR predictions.

Methods

Overview of the models

We generate 10-day forecasts initialized daily throughout 2023, employing four purely statistical AI models and one hybrid model, NeuralGCM. This year is selected because it is excluded from the training datasets of all models. Moreover, the number of days and AR events within one year is sufficient to support robust evaluation while maintaining a balance with the required computational resources. All models are used as released by their developers, with forecasts driven by customized input variables from ERA5 reanalysis data at 00:00 UTC each day, at a spatial resolution of 0.25°. For comparison, forecasts from the numerical model FGOALS (Flexible Global Ocean–Atmosphere–Land System), specifically version FGOALS-f2-V1.462, are also included. All four purely statistical AI models take both pressure-level (13 levels) and surface-level variables as input and produce forecasts at 6-hour intervals for the subsequent 10 days4,9,10,11. NeuralGCM adopts a hybrid architecture, integrating a differentiable atmospheric dynamics solver with machine-learning parameterizations of physical processes8. The numerical model FGOALS generates daily forecasts initialized with China Meteorological Administration’s 40-year reanalysis data63. The atmospheric component of FGOALS involves version 2 of the Finite-Volume Atmospheric Model at a C96 resolution64, approximately equivalent to 1°. It is coupled to the ocean, land, and sea ice components through version 7 of the Community Earth System Model coupler65. A more detailed description of the FGOALS model can be found in previous studies42,66. A summary of all models used in this study is provided in Table 1, and the abbreviations of atmospheric variables are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Evaluation metrics

To assess the accuracy of forecasts for global variables such as specific humidity, we use two widely recognized metrics: anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC) and root mean square error (RMSE)4. The ACC is calculated as the area-weighted correlation between the forecast anomalies and the corresponding ERA5 anomalies, relative to the climatology from 1980 to 2020, calculated within the ERA5 datasets. The RMSE represents the area-weighted difference between the forecast values and ERA5 reanalysis. To further assess the temporal consistency of the forecasts, we compute the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of daily differences in the forecast variables, providing a measure of how well the models capture the temporal evolution of atmospheric fields. The formulas for the evaluation metrics are as follows:

Here, \({{\mbox{A}}}_{i,j}\) is a scalar representing the ERA5 variable at latitude grid \(i\) and longitude grid \(j\). The weighting function \(L\left(i\right)={N}_{{\mbox{lat}}}\frac{\cos {\phi }_{i}}{{\sum }_{i=1}^{{N}_{{\mbox{lat}}}}\cos {\phi }_{i}}\) is applied at latitude \({\phi }_{i}\), where \({N}_{{\mbox{lat}}}\) is the total number of latitude grid points. \(\hat{{\mbox{A}}}\) denotes the forecast variable from the models. The anomaly \({{\mbox{A}}}^{{\prime} }\) represents the deviation of \({\mbox{A}}\) from the climatological mean, defined as the long-term average from 1980 to 2020. Both ACC and RMSE are computed based on the output frequency of the forecast models. Temporal PCCs are calculated at 24‑h intervals, which are suitable for all models, with \({{\mbox{A}}}^{* }\) denoting the temporal change in the variable over that interval.

In addition to the spatial metrics discussed above, we also employ mutual information (MI) to evaluate the temporal correspondence between forecasts and observations. MI quantifies the dependence between two variables, similar to correlation, but without assuming linearity46. The definition of MI is given as follows:

The variables X and Y represent the forecast and observed time series at each grid point for the year 2023. The joint probability distribution \(p(x,y)\) and marginal distributions \(p\left(x\right)\) and \(p\left(y\right)\) are estimated using k-nearest neighbors based on the 365 paired samples67,68. MI quantifies the reduction in uncertainty about the observations given the forecast, representing the amount of information the forecast contains about the observations.

Atmospheric river detection

To detect ARs, \(q\) is required to compute the IVT. Since FourCastNet and FuXi do not directly output specific humidity, we derive it from \(p\), \(t\), and \(r\) using the following equations:

where \(w\) is the mixing ratio, \(p\) is the pressure, \({e}_{s}\) is saturation vapor pressure, \(r\) is the relative humidity, and \(t\) is the temperature. Using the forecasted \(q\), \(u\), \(v\), the IVT is calculated with the following formula:

where \(g\) is standard gravity, \({p}_{t}\) and \({p}_{s}\) represent the upper atmospheric pressure and surface pressure. We choose 200 hPa as \({p}_{t}\) here. Because most of the AI models do not forecast the surface pressure, we set the \({p}_{s}\) as 1000 hPa at a global scale to calculate the IVT.

Among the algorithms participating in the Atmospheric River Tracking Method Intercomparison Project, the PanLu2.0 algorithm (hereafter PanLu) exhibits strong skill in capturing both the spatial structure and lifecycle of ARs69. A global intercomparison further confirms the robustness of AR features identified by PanLu relative to other algorithms23, like GuanWaliser_v270,71, and Mundhenk_v372. Therefore, we adopt the PanLu algorithm to detect ARs in this study73,74, using IVT thresholds derived from the 1980 to 2020 period. The thresholds combine both regional and global components. The regional threshold is determined using a Gaussian kernel density smoothing technique applied to the 85th percentile of IVT, allowing spatial smoothing and reducing bias caused by limited samples in individual grid cells. Additionally, the minimum value of the 85th percentile IVT across all grid cells is used as a global absolute threshold to exclude weak moisture transport events. Detected AR pathways are further filtered based on widely accepted geometric constraints in the AR research community69: a minimum length of 2000 km and a maximum width of 1000 km. The PanLu algorithm also applies a turning angle constraint—defined as the sum of directional changes along the entire trajectory—ensuring that the angle remains below 360°, thereby excluding cyclone-like moisture structures. Furthermore, AR pathways overlapping with the tropics (15°S–15°N) for more than 95% of their length are removed to avoid misclassification of tropical filaments. After identifying AR pathways, most algorithms typically filter out events exceeding a certain duration using a Lagrangian approach75,76,77. However, this step may omit some ARs and introduce additional uncertainty in practical AR forecasting applications40. To avoid this, we do not apply a duration-based filter to AR pathways in this study.

Atmospheric rivers evaluation metrics

To evaluate the forecasting skill of ARs, we use a confusion matrix to quantify the agreement between model forecasts and the ERA5 reference data. This classification yields four possible situations: a hit, when the model correctly forecasts an AR event; a false alarm, when the model forecasts an AR event that does not occur; a miss, when the model fails to predict an AR event present in the ERA5; and a correct rejection, when the model correctly forecasts the absence of an AR event. Evaluation metrics related to AR forecasting, derived from the four confusion matrix situations, are defined as follows:

In addition, differences in IVT and intersection over union (IOU) between the predicted events and the ERA5 reference are used to evaluate the consistency of AR forecast intensity and spatial extent across varying lead times78.

Data availability

The AI models used in this study are publicly available at the following repositories: Pangu-Weather (https://github.com/198808xc/Pangu-Weather), FourCastNet v2 (https://github.com/ecmwf-lab/ai-models-fourcastnetv2), GraphCast (https://github.com/google-deepmind/graphcast), FuXi (https://github.com/tpys/ai-models-fuxi), and NeuralGCM (https://github.com/neuralgcm/neuralgcm). ERA5 reanalysis data are available from the Copernicus Climate Change Service via the Climate Data Store (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47). FGOALS data are accessible through the ECMWF Sub-seasonal to Seasonal Prediction Project (https://www.ecmwf.int/en/research/projects/s2s). The code used in this study is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17076069.

References

Bjerknes, V. Das Problem der Wettervorhersage, betrachtet vom Standpunkte der Mechanik und der Physik. Meteorologische Z 21, 1–7 (1904).

Abbe, C. The physical basis of long-range weather forecasts. Mon Weather Rev 29, 551–561 (1901).

Bouallègue, Z. B. et al. The rise of data-driven weather forecasting: a first statistical assessment of machine learning–based weather forecasts in an operational-like context. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 105, E864–E883 (2024).

Bi, K. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533–538 (2023).

Bauer, P., Thorpe, A. & Brunet, G. The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction. Nature 525, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14956 (2015).

Lynch, P. The origins of computer weather prediction and climate modeling. J. Comput. Phys. 227, 3431–3444 (2008).

Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations. Mon. Weather. Rev. 91, 99–164 (1963).

Kochkov, D. et al. Neural general circulation models for weather and climate. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07744-y (2024).

Lam, R. et al. Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Science 382, 1416–1421 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. FuXi: a cascade machine learning forecasting system for 15-day global weather forecast. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 190 (2023).

Pathak, J. et al. Fourcastnet: A global data-driven high-resolution weather model using adaptive fourier neural operators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.11214 (2022).

Zhang, L., Zhao, Y., Cen, Y. & Lu, M. Deep learning-based precipitation simulation for tropical cyclones, mesoscale convective systems, and atmospheric rivers in East Asia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2024JD041914 (2024).

Dueben, P. D. & Bauer, P. Challenges and design choices for global weather and climate models based on machine learning. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 3999–4009 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. Foundation models as assistive tools in hydrometeorology: opportunities, challenges, and perspectives. Water Resources Res. 61, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024WR039553 (2025).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems. 30 (2017).

Bougeault, P. et al. The THORPEX interactive grand global ensemble. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 1059–1072 (2010).

Allen, A. et al. End-to-end data-driven weather prediction. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08897-0 (2025).

Liu, C. C. et al. Evaluation of five global AI models for predicting weather in Eastern Asia and Western Pacific. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 221 (2024).

Charlton-Perez, A. J. et al. Do AI models produce better weather forecasts than physics-based models? A quantitative evaluation case study of Storm Ciarán. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 93 (2024).

Baño-Medina, J. et al. Are AI weather models learning atmospheric physics? A sensitivity analysis of cyclone Xynthia. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 92 (2025).

Zhao, M. A study of AR-, TS-, and MCS-associated precipitation and extreme precipitation in present and warmer climates. J. Clim. 35, 479–497 (2022).

Zhu, Y. & Newell, R. E. A proposed algorithm for moisture fluxes from atmospheric rivers. Mon Weather Rev 126, 725–735 (1998).

Zhang, L., Zhao, Y., Cheng, T. F. & Lu, M. Future changes in global atmospheric rivers projected by CMIP6 models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD039359 (2024).

Zhu, Y. & Newell, R. E. Atmospheric rivers and bombs. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 1999–2002 (1994).

Payne, A. E. et al. Responses and impacts of atmospheric rivers to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 143–157 (2020).

Waliser, D. & Guan, B. Extreme winds and precipitation during landfall of atmospheric rivers. Nat Geosci 10, 179–183 (2017).

Lavers, D. A. et al. Future changes in atmospheric rivers and their implications for winter flooding in Britain. Environ Res Lett 8, 034010 (2013).

Whan, K., Sillmann, J., Schaller, N. & Haarsma, R. Future changes in atmospheric rivers and extreme precipitation in Norway. Clim Dyn 54, 2071–2084 (2020).

Paltan, H. et al. Global Floods and Water Availability Driven by Atmospheric Rivers. Geophys Res Lett 44, 10,387–10,395 (2017).

Nardi, K. M., Barnes, E. A. & Ralph, F. M. Assessment of numerical weather prediction model reforecasts of the occurrence, intensity, and location of atmospheric rivers along the west coast of North America. Mon Weather Rev 146, (2018).

Lavers, D. A., Pappenberger, F., Richardson, D. S. & Zsoter, E. ECMWF Extreme Forecast Index for water vapor transport: A forecast tool for atmospheric rivers and extreme precipitation. Geophys Res Lett 43, (2016).

Deflorio, M. J. et al. Global assessment of atmospheric river prediction skill. J. Hydrometeorol. 19, 409–426 (2018).

Vitart, F. et al. The subseasonal to seasonal (S2S) prediction project database. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 163–173 (2017).

Cobb, A. et al. Atmospheric river reconnaissance 2021: a review. Weather Forecast, https://doi.org/10.1175/waf-d-21-0164.1 (2022).

Zheng, M. et al. Improved forecast skill through the assimilation of dropsonde observations from the atmospheric river reconnaissance program. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2021JD034967 (2021).

Chapman, W. E., Subramanian, A. C., Delle Monache, L., Xie, S. P. & Ralph, F. M. Improving atmospheric river forecasts with machine learning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10627–10635 (2019).

Chapman, W. E. et al. Probabilistic predictions from deterministic atmospheric river forecasts with deep learning. Mon. Weather Rev. 150, 215–234 (2022).

Meghani, S., Singh, S., Kumar, N. & Goyal, M. K. Predicting the spatiotemporal characteristics of atmospheric rivers: a novel data-driven approach. Glob Planet Change 231, 104295 (2023).

Singh, S. & Goyal, M. K. An innovative approach to predict atmospheric rivers: Exploring convolutional autoencoder. Atmos. Res. 289, 106754 (2023).

Tian, Y. et al. East Asia atmospheric river forecast with a deep learning method: GAN-UNet. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD039311 (2024).

Galea, D. & Ma, H.-Y. Intercomparison of deep learning model architectures for Atmospheric River prediction. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. https://doi.org/10.1175/aies-d-24-0057.1 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Dynamical Madden–Julian Oscillation forecasts using an ensemble subseasonal-to-seasonal forecast system of the IAP-CAS model. Geosci Model Dev. 17, 6249–6275 (2024).

Cordeira, J. M., Ralph, M. F. & Moore, B. J. The development and evolution of two atmospheric rivers in proximity to western north pacific tropical cyclones in october 2010. Mon. Weather Rev. 141, 4234–4255 (2013).

Zhou, Y. et al. Characteristics and variability of Winter Northern Pacific Atmospheric River Flavors. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD037105 (2022).

Ning, Y. et al. A mutual information theory-based approach for assessing uncertainties in deterministic multi-category precipitation forecasts. Water Resour Res 58, e2022WR032631 (2022).

Shin, C. S., Dirmeyer, P. A. & Huang, B. A Joint approach combining correlation and mutual information to study land and ocean drivers of U.S. droughts: methodology. J. Clim. 36, 2795–2814 (2023).

Hodson, T. O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): when to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-5481-2022 (2022).

Rea, D. et al. The contribution of subtropical moisture within an atmospheric river on moisture flux, cloud structure, and precipitation over the Salmon River Mountains of Idaho using moisture tracers. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD037727 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Extreme atmospheric rivers in a warming climate. Nat. Commun. 14, 3219 (2023).

Rasp, S. et al. WeatherBench 2: a benchmark for the next generation of data-driven global weather models. J Adv Model Earth Syst 16, e2023MS004019 (2024).

Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E). CW3E Event Summary: 30 November – 6 December 2023 (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, 2023). Available at: https://cw3e.ucsd.edu/cw3e-event-summary-30-november-6-december-2023/.

Mudiar, D., Rondanelli, R., Valenzuela, R. A. & Garreaud, R. D. Unraveling the dynamics of moisture transport during atmospheric rivers producing rainfall in the Southern Andes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108664 (2024).

Ebert-Uphoff, I. & Hilburn, K. The outlook for AI weather prediction. Nature 619, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02084-9 (2023).

Camps-Valls, G. et al. Artificial intelligence for modeling and understanding extreme weather and climate events. Nat. Commun. 16, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56573-8 (2025).

Xu, Z., Han, Y. & Yang, Z. Dynamical downscaling of regional climate: A review of methods and limitations. Sci. China Earth Sci. 62, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-018-9261-5 (2019).

Miao, C., Su, L., Sun, Q. & Duan, Q. A nonstationary bias-correction technique to remove bias in GCM simulations. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 5718–5735 (2016).

Chen, J., Brissette, F. P. & Lucas-Picher, P. Assessing the limits of bias-correcting climate model outputs for climate change impact studies. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 1123–1136 (2015).

Ignacio, L.-G. et al. Dynamical-generative downscaling of climate model ensembles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2420288122 (2025).

Xu, H., Zhao, Y., Dajun, Z., Duan, Y. & Xu, X. Exploring the typhoon intensity forecasting through integrating AI weather forecasting with regional numerical weather model. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 38 (2025).

Brewer, M. J., Fovell, R. G. & Capps, S. B. Hybrid numerical weather prediction: downscaling GraphCast AI forecasts for downslope windstorms. Weather Forecast, https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-24 (2025).

Yang, Z. et al. Seasonality and climate modes influence the temporal clustering of unique atmospheric rivers in the Western U.S. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 734 (2024).

Bao, Q. et al. Outlook for El Niño and the Indian Ocean Dipole in autumn-winter 2018-2019. Kexue Tongbao Chin. Sci. Bullet. 64, 73–78 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. CRA-40/atmosphere—the first-generation Chinese atmospheric reanalysis (1979–2018): system description and performance evaluation. J. Meteorological Res. 37, 1–19 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Evaluation of FAMIL2 in simulating the climatology and seasonal-to-interannual variability of tropical cyclone characteristics. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 11, 1117–1136 (2019).

Craig, A. P., Vertenstein, M. & Jacob, R. A new flexible coupler for earth system modeling developed for CCSM4 and CESM1. Int. J. High Performance Comput. Appl. 26, 31–42 (2012).

Zeng, L. et al. Impacts of humidity initialization on MJO prediction: a study in an operational sub-seasonal to seasonal system. Atmos. Res. 294, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2023.106946 (2023).

Ross, B. C. Mutual information between discrete and continuous data sets. PLoS One 9, e87357 (2014).

Kraskov, A., Stögbauer, H. & Grassberger, P. Estimating mutual information. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics 69, 066138 (2004).

Zhou, Y. et al. Uncertainties in atmospheric river lifecycles by detection algorithms: climatology and variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033711 (2021).

Guan, B. & Waliser, D. E. Atmospheric rivers in 20 year weather and climate simulations: a multimodel, global evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 5556–5581 (2017).

Guan, B. & Waliser, D. E. Detection of atmospheric rivers: evaluation and application of an algorithm for global studies. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 12,514–12,535 (2015).

Mundhenk, B. D., Barnes, E. A. & Maloney, E. D. All-season climatology and variability of atmospheric river frequencies over the North Pacific. J. Clim. 29, 4885–4903 (2016).

Pan, M. & Lu, M. East Asia Atmospheric River catalog: annual cycle, transition mechanism, and precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089477 (2020).

Pan, M. & Lu, M. A novel atmospheric river identification algorithm. Water Resour. Res. 55, 6069–6087 (2019).

Lora, J. M., Shields, C. A. & Rutz, J. J. Consensus and disagreement in atmospheric river detection: ARTMIP global catalogues. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089302 (2020).

Collow, A. B. M. et al. An overview of ARTMIP’s tier 2 reanalysis intercomparison: uncertainty in the detection of atmospheric rivers and their associated precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD036155 (2022).

O’Brien, T. A. et al. Increases in future AR count and size: overview of the ARTMIP tier 2 CMIP5/6 experiment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD036013 (2022).

Tian, Y. et al. A Deep-learning ensemble method to detect atmospheric rivers and its application to projected changes in precipitation regime. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD037041 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council’s collaborative research funds (project nos. C5004-23G, C6032-21G), general research fund (project no. 16300424), theme-based research scheme (project no. T22-501/23R, T22-607/24-N) and NSFC/RGC Collaborative Fund (project no. CRS_PolyU503/23). This work is part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) endorsed program “Seamless Prediction and Services for Sustainable Natural and Built Environments (SEPRESS) 2025-2032” under their International Decade of Science for Sustainable Development. This work is also supported by the Otto Poon Centre for Climate Resilience and Sustainability at HKUST. We would like to express our gratitude for the Centre’s support for our research. Finally, we thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and detailed suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. Zhang contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, original draft, and revision of the manuscript. M. Lu contributed to the conceptualization, supervision of the project, and revision of the manuscript. Q. Bao contributed to the investigation and revision of the manuscript. Y. Zhao contributed to the methodology and revision of the manuscript. J. Yang contributed to the investigation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks SHIVAM SINGH, Sara Vallejo-Bernal and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joseph Aslin, Nicola Colombo, and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Lu, M., Bao, Q. et al. Global performance benchmarking of artificial intelligence models in atmospheric river forecasting. Commun Earth Environ 6, 894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02823-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02823-y