Abstract

Understanding the coupled evolution of fault friction and permeability is essential for assessing seismic risk, reservoir stability, and caprock integrity. Fault slip alters permeability by opening or sealing fluid pathways, linking frictional behavior to subsurface fluid transport. This review synthesizes findings from theoretical models, experiments, and numerical simulations to elucidate the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of faults. Key factors influencing this coupling include fault mineralogy, roughness, and temperature, as well as geological settings and fluid injection strategies. Fault gouge plays a dominant role in controlling seismicity-permeability interactions in mature faults, while rough surfaces govern these behaviors in incipient faults. Scaling relationships derived from laboratory studies link frictional weakening to permeability changes, offering predictive tools for subsurface fault behavior. Understanding these processes provides critical insights into fault stability, seismic potential, and fluid transport and offers valuable guidance for managing induced seismicity and optimizing subsurface activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the rapid growth of hydraulic stimulation and fluid injection for energy extraction and underground storage has renewed interest in how these activities affect the physical state of the subsurface—especially the development of connected porosity and permeability. Understanding how fluids move through faults—that is, understanding fault permeability—is essential for predicting how faults respond to injection and to crustal stress changes that occur during the seismic cycle1,2,3,4,5,6. These insights provide understanding for natural earthquakes and support energy extraction and subsurface storage applications, including CO2 sequestration, wastewater disposal, and hydrogen storage7,8,9,10. Fault slip across different scales may be manifest as seismic or aseismic11,12 depending on the morphology of the fracture and fault surface13, mineralogical composition14,15,16,17, temperature18,19, and the stiffness of the host rock surrounding the fault20. Fault slip—whether seismic or aseismic—is closely coupled to poromechanical processes such as dilation and compaction within the fault zone21,22,23. These changes in pore structure dynamically affect pore-fluid pressure, which can either stabilize the fault or promote slip instability and dynamic rupture. Recent modeling efforts show that fault weakening can be driven by rapid self-pressurization of fluids during shear, while subsequent rupture propagation is sustained by pressure waves within a fluid-saturated, deforming fault zone24. In this interaction, static features of fault systems evolve over time, and various seismicity-permeability coupling responses emerge. This review synthesizes experimental and numerical studies of the coupled evolution of friction and permeability in individual fault zones. We aim to (1) evaluate how fault slip enhances or reduces permeability, (2) assess fluid leakage and sealing behaviors of faults, and (3) improve understanding of seismicity linked to fault-fluid interactions. These insights stem from both natural and induced earthquakes, with the latter forming the primary focus. The two types of earthquakes exhibit significant differences in temporal scale and causation, but share a common theoretical framework. To structure our review, we consider four key aspects that govern the coupling between fault friction and permeability evolution.

We begin by examining the geological and mechanical characteristics of fault zones, which play a central role in regulating both slip behavior and fluid transport. Fault attributes such as mineralogy, surface roughness, and structural maturity evolve over time and are fundamental in determining whether deformation leads to dilation and permeability enhancement or to compaction and sealing. These properties are especially relevant for understanding the different responses of incipient versus mature faults.

Next, we explore the scaling relationships that link fault slip stability to permeability evolution. Theoretical models and laboratory data suggest that measurable frictional parameters—such as those derived from rate-and-state friction (RSF) laws—correlate with fault dilation or compaction and thus can be used to predict permeability changes. From a laboratory perspective, the scaling relationships do not account for the permeability changes resulting from varying effective normal stress. We assess their applicability in laboratory simulations and potential extensions to field-scale observations.

We then focus on the key physical controls that modulate the seismicity-permeability coupling, including mineral composition, temperature, and fault surface roughness. These factors influence both fault strength and the evolution of the pore network during shear. Their effects are systematically investigated in laboratory experiments and numerical simulations. Understanding how these variables interact is essential for interpreting the contrasting behaviors observed across fault types and geological settings.

Finally, we consider how fault slip and permeability evolve throughout the seismic cycle. Particular attention is given to the dynamics of fault reactivation, transient permeability enhancement, and fault valving processes. A review of the two-way coupling between faults and fluids during seismic cycles provides complementary insights beyond those offered by scaling relationships. These behaviors have potential implications for induced seismicity and for the long-term hydraulic integrity of caprock systems. By synthesizing recent observations and models, we highlight how the coupling between shear deformation and fluid flow shapes fault evolution across a wide range of timescales.

In this review, we use RSF as a practical proxy for seismicity, reflecting the tendency of a fault to either accelerate (unstable slip) or stabilize (creep) under shear loading. While fault slip stability can also be governed by more complex physical processes, rate-and-state parameters provide a consistent and experimentally validated framework for interpreting fault behavior in laboratory and numerical studies25,26,27. In this context, RSF laws offer a practical and physically grounded way to characterize fault stability under shear and to distinguish between stable and unstable fault slip. In contrast, permeability is an explicitly measurable property that evolves with deformation and is commonly assessed using experimental or numerical methods described in the literature. In this review, we focus on individual fault systems bounded by low-permeability host rocks. This simplified fault geometry—a single fault flanked by low-permeability host rocks—reflects the dominant setup used in laboratory experiments and numerical models. It allows for controlled investigation of friction-permeability coupling without the added complexity of interacting fault networks or high-permeability damage zones. This simplified configuration can represent either incipient faults with bare interfaces or mature faults with gouge-filled cores but limited damage zones28,29,30,31,32.

To avoid ambiguity in terminology, we distinguish between faults and fractures as follows: faults are discontinuities that accommodate shear displacement, while fractures refer more broadly to cracks or voids in the rock mass, regardless of whether they slip. In particular, we use the term cracks to describe tensile-mode fractures where failure occurs through normal opening rather than shear—a process often associated with microseismicity in response to elevated pore pressure. These distinctions are essential for interpreting permeability evolution in existing faults, as shear-induced dilation along faults differs markedly from permeability changes due to tensile fracturing.

Finally, we emphasize the importance of fault maturity in shaping both mechanical behavior and fluid flow. Incipient faults – often characterized by rough, bare rock interfaces—exhibit different deformation and permeability responses compared to mature faults with well-developed gouge zones. The degree of maturity influences whether strain localizes along discrete surfaces or is distributed across a granular layer, which in turn controls the efficiency of compaction, dilation, and fluid pressurization. Recognizing these maturity-dependent behaviors is key to understanding how fault permeability evolves during both seismic and aseismic slip.

Geological settings of faults

Mineralogy

The Earth’s crust exhibits mineralogical heterogeneity across spatial scales and contains a diverse array of mineral constituents, with approximately twenty primary components constituting its predominant composition. For natural strata, the diversity of minerals in rocks is manifested through three geological dimensions: lateral continuity, vertical stratification, and burial depth. For example, phyllosilicates, tectosilicates, and carbonates are common in shale gas reservoirs17. Taking the Longmaxi Shale in the Sichuan Basin as an example, all 27 outcrop samples collected on a fault ramp are mainly composed of the three types of minerals mentioned above, and the mineral contents vary widely with sample ID (Fig. 1)33. Enhanced geothermal systems are mainly composed of granite, skarn, marble, tuff, and granodiorite34,35,36. Carbonate rocks are excluded from these systems because these rocks may undergo hydrothermal reactivation, potentially sealing fluid networks through mineral precipitation37,38. The characteristics of rocks determine the function of reservoirs. Shale rocks store organic matter deposited in anoxic environments, which is later converted to hydrocarbons through burial and thermal maturation, while geothermal reservoirs rely on permeable rocks (e.g., cracked granite) to enable fluid circulation, transferring heat from deep sources (e.g., magma or radiogenic heating) to the surface39,40. Other reservoirs for gas storage include salt caverns, underground aquifers, abandoned oil and gas fields, and mining pits. In addition to reservoir rocks, caprocks with low permeability and their ability to withstand displacement pressure, which is necessary to force hydrocarbons into the pore space of rocks, are indispensable for a complete reservoir41. These functional requirements constrain the type of rocks in the caprocks and reservoirs. The permeability of a rock under unconfined conditions is directly determined by its existing pore structure. The minerals influence the pore structure of a rock during its diagenesis, e.g., rocks enriched in clay minerals are more prone to form smears, whereas those with a lower clay content are prone to form sandstones and form foliations only under extremely high stresses and temperatures42.

Schematic geological section of the Longmaxi Formation and shale outcrop sampling locations, with a heat map of mineral components below to demonstrate mineral heterogeneity of a specific fault33.

In addition to the influence on permeability, numerous experimental studies have confirmed that the mechanical response exhibited by minerals also determines the discrepancy in the frictional properties of faults43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Owing to the structural diversity of mineral lattices, relatively “weak” minerals would be easily activated and then deform more drastically compared to ‘strong’ minerals under the same stress conditions in which weak minerals may form a barrier reducing the fluid conductivity of faults14,53,54. Frictional stability also provides essential insights into seismicity-permeability coupling as it relates to fault dilation and compaction55. Experimental observations reveal that identical materials can exhibit different velocity-dependent behaviors when conditions, such as temperature and velocity, change. The velocity-strengthening behavior in phyllosilicate-rich gouges could switch into a velocity-weakening state when slip velocity increases to ~1 m/s56. Recent studies indicate that this pattern is inconsistent with some dry material showing relatively high frictional strength57,58. The compositional heterogeneity may also influence the seismicity-permeability responses of faults, as heterogeneous faults show different friction properties and microstructures than homogenous faults59,60,61.

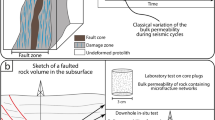

Structure

Faults are the product of crustal movements and, as weak and broken parts of the intact crust, fault zones play an essential role in storing fossil fuels and greenhouse gases as well as being important conduits for subsurface fluids31,62,63,64. The development of fault systems allows for the release of stress concentrations in the Earth’s crust, and the developed systems may alter the mechanical and hydrogeological properties of the crust65. Fault cores are typically low-permeability, low-strength components of fault systems, whereas damage zones exhibit larger permeability and transitional strength values between those of protolith and fault core. In individual fault systems, the three main structures, the fault core, the damage zone, and the protolith, may show different pore structures and mineral compositions, resulting in differences in their hydraulic responses66. Multi-fault systems are more structurally complex, where there are multiple high-strain deformation bands and potentially interconnected damage zones67. Despite the presence of discrete fractures and deformation bands, two key factors, fractures as channels and gouges as barriers, control the mechanics and hydrology of the fault zones, and their spatial distribution will influence the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior68.

Most studies of seismicity-permeability coupling focus on individual fault systems, and these studies simplify the realistic fault structure as a shear interface and focus attention on the roughness of this interface69,70,71. This simplification is validated by the successful reproduction of seismic patterns regardless of whether the faults are simulated by using bare surfaces or fault gouges72,73. Shear experiments have shown that abrasive materials fill faults and potentially block the fluid migration apertures74. Firm particles can transiently open the laboratory faults, whereas sustained shear causes the abrasive material to thin out and form gouges that continuously reduce the fault’s conductivity41. Thus, the hydraulic properties of the two fault types (mature faults and incipient faults) are quite different, which requires additional assumptions and hydraulic parameters to characterize them. A common example of this is the flat panel model mentioned in this paper. Multi-fault systems are common in nature, and the diversity of structures complicates the coupling behavior of seismicity and permeability. Studies of multiple faults have focused on fault interactions, which are based on geologic observations and data analyses that do not allow for the simultaneous acquisition of friction and permeability evolution data75,76,77,78. Therefore, our main focus is on the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of individual fault systems. Rock-bridge experiments provide a viable method for simulating fault interactions by subjecting pre-cracked rock specimens to controlled mechanical loading, where the progressive failure of intact rock segments between artificial cracks mimics natural fault linkage processes79,80.

Size

Fault dimensions—including fault plane length, width, core thickness, and damage zone thickness—play a fundamental role in controlling the mechanical interaction between faults and their surrounding host rocks. Accurate characterization of these dimensions is crucial for constructing realistic numerical models, especially in contrast to earlier approaches that relied heavily on stochastic or idealized geometries81,82,83. Much effort has been invested in studying fault outcrops and establishing underground tunnels to observe fault characteristics84,85,86. The dimensions of faults are spatially and temporally variable. It is clear from the compiled data that the maximum dimension, which is the maximum length of the fault plane perpendicular to the slip direction, increases in an approximately linear relationship with displacement while discrepancies emerge between the datasets for faults at different scales87. Geological factors that may result in a departure from linearity include the structural development of the faults. It is worth noting that the slipped surfaces are not ideally regular shapes, and the intersection of faults or the subjective nature of sampling makes it challenging to accurately define the fault dimensions, as does distinguishing the boundaries between the fault core and the damage zone.

Calculation of seismic moments based on dislocation theory is related to the fault size88. The fault is usually treated as an approximate rectangular or circular fault, and the stress drop is assumed to be constant. The seismic moment \({M}_{0}\) at mean displacement \(\Delta u\) (or dislocation) is then calculated as Eq. 2.1 (Fig. 2):

Where \(A\) presents the reactivated fault plane area, and \(G\) is the shear modulus. \(\Delta u\) denotes the mean displacement, and \(V\) marks the affected volume of the fault zone. \(\varDelta \tau\) is the constant stress drop, and \(\gamma\) is the shear strain.

In general, the size of the slipped fault zone is typically calculated based on the measured moment and Eq. 2.1. Although fault dimensions are often difficult to constrain in field settings, the volume of injected fluid is typically well known. Under the assumption of a saturated medium with limited pore pressure diffusion, McGarr established a direct link between fluid injection volume and induced seismicity89. Specifically, his model relates cumulative seismic moment to changes in pore pressure, providing a way to estimate the total seismic energy release over time based on the injected volume90. Building on this framework, McGarr also proposed a relationship between maximum earthquake magnitude and injected volume derived from the Gutenberg-Richter distribution89. By assuming that only one event corresponds to the maximum magnitude, this framework predicts that the maximum possible magnitude scales with injected volume, irrespective of fault size.

In parallel, Shapiro and colleagues proposed a seismogenic index to assess seismic hazards from injection operations91. Unlike McGarr’s mechanistic model, this is a statistical approach based on observed seismicity rates and Gutenberg-Richter parameters, making it less sensitive to geological uncertainties such as fault geometry or rock properties92. More recent studies that incorporate fault rupture physics93,94 have shown that both the total seismic moment and the maximum magnitude scale with injected volume following a power-law relationship with an exponent of ~1.5—in contrast to the linear (exponent = 1) scaling proposed by McGarr89. The similarity lies in the fact that the model, integrating the full poromechanical effects, reflects the dependence of the maximum magnitude event on the fault size, while McGarr’s model, only considering skeletal deformation, reflects this dependence indirectly through the volumetric upper limit of the injected fluid regarding a given stress state and total volume89,94. The differences between the models highlight how different assumptions about pore pressure diffusion, fault activation, and rupture dynamics can significantly alter the inferred relationships between fluid injection and induced seismicity.

Pressure and temperature conditions

Crustal stress and temperature history are major factors influencing the transformation of crustal minerals; e.g., montmorillonite undergoes a smectite-to-illite transformation in the 100–120 °C range95. The effect of temperature-stress conditions on the seismicity and permeability of faults, respectively, has been extensively studied18,19,96,97,98,99,100,101. The critical stiffness equation, described in detail in the next section, suggests that an increase in effective normal stress favors seismicity, while temperature effects have been shown to alter the thermal activation process and healing mechanism of fault friction97,102. Similarly, at higher effective normal stresses, the transition from brittle deformation to plastic deformation is favored, which promotes the sealing process of the fault and reduces the fault permeability faster103,104. The corresponding healing mechanisms at different temperatures change fault microstructures and alter their permeability, and in addition, high temperatures will induce thermal cracking to promote increased permeability97,105. Although the independent effects of stress-temperature conditions on seismicity and permeability are well established, the coupling may not be a linear superposition of the two. We review the stress and temperature effects on the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of individual faults in later sections.

The scaling relationship between seismicity and permeability

Rate-and-state friction

RSF laws were first proposed by Dieterich et al.106,107,108,109. In order to model velocity-dependent friction and static healing, RSF laws were proposed to describe the dependence of frictional resistance \(\mu\) on slip velocity \((V)\) and an evolving state variable \((\theta )\). The most widely used form is107,108,

Where \({\mu }_{0}\) is a constant appropriate for a steady-state slip at velocity \({V}_{0}\), \(V\) is the slip rate after any perturbation. \({D}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) is the shear distance required for friction to re-stabilize and is known as the critical slip distance; \(\theta\) characterizes the frictional state of the fault107. Parameters \(a\) and \(b\) are empirical constants.

Differential equations for the state variable proposed based on various theoretical approaches make important differences between these RSF laws. Dieterich proposed the aging effect of contact, where the state variable increases when the slip velocity is zero13,108,

Ruina proposed a different evolution law in which velocity and slip were of primary importance107,

For steady-state sliding, each of the laws gives

Where \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{\rm{ss}}}}\) represents the difference between two steady-state frictional coefficients, and \(\Delta {{\mathrm{ln}}}V\) represents the logarithmic difference in two corresponding velocities. From the above equations, \((a-b)\) values could be determined in order to evaluate the frictional stability of faults (Fig. 3a). Positive values of \((a-b)\) indicate that fault slip tends to self-stabilize. Negative values of \((a-b)\) indicate that the fault slip tends to accelerate, and instability occurs if the critical stiffness is greater than the system stiffness. Based on the one-dimensional spring-block theory, if the frictional resistance decreases faster than the spring unloads, the block accelerates due to unbalanced forces, and friction instability occurs. In slow velocity (~μm/s) friction experiments, stick-slip behavior arises when the system stiffness \(K\) is less than the critical stiffness \({K}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\), which is given by the following equation107:

Where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) is the effective normal stress, \(b-a\), and \({D}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) are the same parameters in Eq. 3.1. The above equations suggest that high stresses, short critical slip distances, and pronounced velocity-weakening behaviors are more conducive to the generation of large unbalanced forces as well as violent earthquakes.

The debate continues over the correctness of the aging law and the slip law, and these laws exhibit quite different patterns in describing the process of earthquake nucleation110,111,112. For the time being, the aging law and slip law are still widely used since they fit the friction data of laboratory experiments well113,114,115,116. In order to get a proper understanding of the friction response of natural faults, researchers analyzed the frictional responses for a wider range of materials and parameters and tried to optimize the original RSF laws97,117,118,119. In a subsequent development, the Chen-Niemeijer-Spiers (CNS) model was proposed to describe the microphysical behavior of granular friction, and this model is capable of explaining the evolution of the RSF law variables120,121,122. The temperature dependence of the frictional strength can be integrated into the RSF laws and the CNS model by introducing activation energies and stress power exponents to describe the inter-competing healing mechanisms97,123.

Another avenue of research on RSF laws is to characterize fault friction behavior during the inter-seismic period, which has important implications for fault reactivation and earthquake recurrence124,125,126,127. The evaluation of the fault healing rate is important in understanding the entire seismic cycle128. The frictional healing degree \((\varDelta \mu )\) (Fig. 3b) is defined as the difference between the peak friction coefficient subsequent to the hold and the steady-state friction coefficient prior to the hold16. In contrast, the frictional relaxation \((\varDelta {\mu }_{{{\rm{c}}}})\) is typically determined from the steady-state friction coefficient by subtracting the minimum friction coefficient during the hold (Fig. 3b). The frictional healing rate \((\beta )\) and frictional relaxation rate \(({\beta }_{{{\rm{c}}}})\) are both logarithmic functions of the hold time46. A larger healing rate implies that the fault will be reactivated with a larger stress drop and result in faster rupture propagation in the same time interval126. The healing process of faults can also be fitted by two different evolution laws. Once shear loading has ceased, fault healing due to processes such as compaction is defined as the evolution of the state variable,

In the above equation, \({\theta }_{0}\) is a reference state variable in the steady state slip before shear ceases, while \(\varDelta \theta\) is the change in the state variable during the healing process and is determined by one of Eqs. 3.2 or 3.3. The fitting equation from the laboratory results is in agreement with the friction law128,

In this equation, \({t}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) represents the cut-off time for the healing effect, \(\Delta {t}_{{{\rm{h}}}}\) is the healing duration, and \({\beta }_{0}\) denotes the healing rate and is of the same order of magnitude as the \(b\) value. At steady state, the value of the state variable depends on both the critical slip distance \({D}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) and the prior slip velocity \({V}_{0}\). As a result, the healing behavior of a fault during the inter-seismic period may be influenced by the fault’s previous slip history128. While the aging law provides a great match to velocity-step data in laboratory experiments, its predictions for frictional healing during slide-hold-slide experiments are less accurate. Specifically, the theoretical healing curves derived from the aging law fail to reproduce key features of experimental data, such as the frictional evolution during the hold phase and the re-strengthening that occurs just after sliding129. These discrepancies suggest that the theoretical models do not fully capture the physical processes active during healing. Further examination of this mismatch found that the slip law, rather than the aging law, provides a better fit to experimental observations129. In particular, the slip law more effectively captures the behavior associated with large velocity steps and the recovery of frictional strength during healing, offering improved agreement with laboratory data across a range of loading conditions.

Traditional RSF laws describe how friction evolves with slip velocity and a state variable that reflects the maturity of contact surfaces, but they typically assume constant normal stress. Fault responses to varying normal stresses have been investigated by introducing a step or pulse variation of normal stress. This response is purely mechanical in nature, as no fluids are involved, and the change in shear stress results from two ways: (1) elastic coupling between normal stress and shear stress; (2) state variable variations caused by normal stress changes130. However, in fluid-saturated fault zones, deformation also modifies porosity, which in turn alters pore fluid pressure and therefore effective normal stress. Recognizing this limitation, Segall and Rice proposed a constitutive framework that couples RSF with porosity evolution and pore pressure dynamics, providing a more realistic description of fault behavior during shear21.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the model introduces a feedback loop between shear slip, porosity changes, and pore pressure evolution. When shear begins, the fault zone may undergo dilatancy, increasing pore space and thereby reducing pore fluid pressure under the undrained condition131,132,133. This pressure drop raises the effective normal stress and temporarily stabilizes the fault, suppressing acceleration132,133. Conversely, if the fault compacts during shear—such as when granular material collapses or pore space closes—the reduced porosity leads to fluid pressurization, which lowers effective normal stress and promotes further slip22,134,135. This feedback can lead to rapid weakening and even dynamic rupture, depending on the rate of slip and the hydraulic diffusivity of the medium.

a The one-dimensional spring-slider diagram modeling fault-fluid interaction. b The transition from dilatation to compaction at high slip rate \(V\) leads to a decrease in porosity \(\varphi\) and a rise in pore pressure \(p\), which in turn weakens the fault strength \(\mu (\sigma -p)\) (Compaction weakening); c the reverse transition leads to an increase in porosity and a decrease in pore pressure, which in turn stabilizes the fault (Dilatancy strengthening). The pore pressure evolution depends on a combination of porosity evolution and fluid diffusion.

Assuming that there exists a steady state porosity \({\phi }_{0}\) at which the slip velocity of the fault is \({V}_{0}\), the porosity evolves as a function of velocity:

Where epsilon \(\varepsilon\) is the dilatancy coefficient (distinct from the scaling coefficient \(\epsilon\) introduced later). Here,\(\,\phi\) and \({\phi }_{0}\) represent the porosity at velocities \(V\) and \({V}_{0}\), respectively, and \({D}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) is the critical slip distance.

Pore pressure evolution during Darcy flow is calculated based on conservation of fluid mass. By neglecting full poroelastic coupling—that is, disregarding the influence of fluid pressure variations on rock deformation and focusing on the fluid diffusion, the pore pressure evolution equation is21:

Where \({p}_{{{\rm{f}}}}\) denotes the pore pressure within the fault zone, \({p}_{0}\) is the pore pressure in the surroundings, and \(\beta\) is the pore compressibility. The fluid diffusion time scale \({t}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\) is given by:

Where \(D\) is the diffusion coefficient, and \(L\) is the characteristic diffusion length scale (fault gouge thickness).

A key insight from this model is that fluid pressurization can emerge spontaneously, even in the absence of external injection. The resulting pore pressure evolution is governed not only by deformation but also by fluid flow: fast shear in undrained conditions enhances pressure transients, while more permeable systems allow for drainage and pressure dissipation. The coupled equations governing this system include: (1) A RSF law where friction depends on both velocity, state variable, and effective normal stress108; (2) A porosity evolution law as a function of shear strain or slip21; (3) A diffusion equation linking porosity change to pore pressure under fluid mass conservation21.

This framework links micromechanical deformation to macroscopic slip stability, unifying processes of healing, slip initiation, and permeability evolution21,136. It also explains how slow slip, valving behavior, and even runaway dynamic rupture can emerge from internal feedback within the fault zone, especially under low permeability or high strain-rate conditions137. Recent experimental studies reveal that the dilation of intact rock during rupture is significantly greater than that of gouge observed during the reactivation or acceleration phase138. The dilatancy strengthening effect with a decline in pore pressure allows for stabilizing the rupture process and sustaining afterslip during subsequent pore pressure recharge139. However, when the dilation effect causes fluid vaporization, dynamic fracturing may still occur23. As such, this model provides the physical basis for understanding seismicity-permeability coupling—including spontaneous fluid overpressure generation, transient fault weakening, and permeability enhancement—across both natural earthquakes and injection-induced seismicity.

Permeability

Permeability implies whether the fault can effectively conduct fluids to facilitate the fluid injection, migration, and extraction. In addition, the tightness of cracks can help assess the effectiveness of geologic storage for fluids and waste products such as wastewater and carbon dioxide. The tortuosity and roughness of the interface, in conjunction with the inertial effects of the fluid, cause the fluid velocity to deviate from the parabolic velocity profile \({u}_{{{\rm{x}}}}(z)\) assumed by Darcy flow, thereby complicating the calculation of permeability (Fig. 5). As a result, most of the existing research efforts have investigated the permeability of individual faults. The early proposed method for calculating fault permeability is the cubic law, which describes the ability of an incompressible laminar fluid to pass between two parallel flat panels (Fig. 5). Although the Navier-Stokes equations (NSE) provide a more rigorous basis for calculating hydraulic apertures at that time and were considered to be the most accurate, the computational effort required for this method is cumbersome140,141,142. Once the effects of nonlinearities and inertial effects on the flow are neglected, the NSE can be reduced to the cubic law, which has been employed in numerous applications143. In numerical modeling, the cubic law can simplify the calculation process to maintain high efficiency. For laboratory experiments and natural faults, the cubic law reduces a complex flow network to a flat panel model with an opening that is comparable to the hydraulic aperture (Fig. 5). This simplification costs the accuracy of permeability measurements, but it dramatically improves their efficiency and usefulness140.

The fault hydraulic aperture (\(e\)) can be computed using the following equation in the field experiment rather than the real aperture \({e}_{{{\rm{r}}}}\)144:

Where \(T\) (m2 s−1) is the hydraulic transmissivity, \({\mu }_{{{\rm{vis}}}}\) (Pa s) is the fluid viscosity, \(\rho\) (kg m-3) is the fluid density, and \(g\) (m s-2) is the acceleration due to gravity. In the case of the fluid-flow-through experiment in the laboratory, fault permeability is evaluated according to the cubic law. The measured fault permeability \({k}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\) (m2) can be expressed by the measured hydraulic aperture \({e}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\) (m)145:

Where \({\mu }_{{{\rm{vis}}}}\) (Pa s) is the fluid viscosity; \(L\) (m) is the length of the fault surface; \(Q\) (m3 s-1) is the measured flow rate; \(W\) (m) is the fault width; and \(\Delta {P}_{{{\rm{f}}}}\) (Pa) is the fluid pressure difference between the downstream \({P}_{{{\rm{out}}}}\) and upstream \({P}_{{{\rm{in}}}}\) of the fault (Fig. 5). The porosity corresponding to the hydraulic aperture based on the cubic law is defined as the effective porosity. The two formulas above use the same methodology but different parameters.

Scaling relationship between \({{\boldsymbol{a}}}-{{\boldsymbol{b}}}\) values and permeability

A laboratory study proposes a method for coupling fault dilation with velocity variation. For any velocity step, the change in pore space is related to slip velocity variation146:

In this equation, \(\varepsilon\) is the dilatancy coefficient for the magnitude of dilation in response to slip velocity variation, and its negative value represents the compaction magnitude. Assuming that the ratio of the hydraulic aperture variation \(\Delta e\) to the initial hydraulic aperture \({e}_{0}\) evolves in a similar pattern based on the cubic law, the hydraulic aperture variation is calculated by:

Here, we use another scaling coefficient \(\epsilon\) to replace the dilatancy coefficient \(\varepsilon\). Because the dilatancy coefficient describes the variation in fault volume, it does not necessarily describe the real response of the hydraulic aperture. The ratio of the fault permeability after the velocity variation and the initial fault permeability (\(k/{k}_{0}\)) is related to the ratio of hydraulic aperture variation (\(\varDelta e/{e}_{0}\)), as54,147,148,149:

By combining Eqs. 3.4, 3.14, and 3.15, the permeability ratio can be expressed as a function of the \(a-b\) value. This equation explains the inverse permeability change between the data of velocity increase steps and velocity decrease steps:

Similar to the \(a\) and \(b\) values in the RSF law, the scaling coefficient \(\epsilon\) is also an empirical coefficient obtained by fitting experimental friction and permeability data. This implies that, through field observations with adequate data and well-constrained parameters \(a\), \(b\), and \(\epsilon\) values, it is possible for one to quantitatively characterize the friction variations associated with fault acceleration/deceleration and the resultant dilation behavior (Fig. 6). The Eq. 3.13 reflects the same physical basis as the porosity evolution law proposed by Segall and Rice21, i.e., shear exhibits dilation or compaction effects at higher slip rates. However, the actual change in permeability is less pronounced than the change in porosity. When porosity increases due to dilatancy, a significant increase in permeability may not occur because of the lack of well-connected hydraulic pathways. Therefore, we distinguish the scaling coefficient mentioned in this paper from the dilatancy coefficient proposed by Segall and Rice21. The theoretical framework coupling RSF friction—porosity—pore pressure can reproduce the whole process of fluid-fault interaction (Fig. 4). This extended framework can describe the combined effects of porosity evolution and fluid diffusion leading to fault overpressure or depressurization, enabling fluid-controlled fault behavior24. In contrast, the scaling coefficient reflects how the geologic setting affects the frictional response of the fault and how the subsequent frictional response affects the hydraulic response, i.e., the process by which friction controls permeability. Although most of the experiments were conducted under constant stress conditions, their results reproduce the enhanced permeability observed in unstable faults in nature (Fig. 6). For field data, especially for faults occurring in reservoirs and caprocks, permeability measurements and the quantification of the scaling coefficients are greater priorities144. Integrating the permeability – pore pressure relationship into the RSF framework may offer a way to bridge the gap between modeling and practice150. At the same time, comparing the evolution patterns of the two parameters facilitates assessing the hydraulic characteristics of the fault zone system. When a fault zone contains few unconnected pores and approximates a flat panel model, the permeability evolution may be consistent with the porosity evolution. In this case, the scaling coefficient may be equivalent to the dilatancy coefficient.

All data are derived from velocity increase steps, except for the translucent inverted triangles, which are derived from velocity decrease steps. Relative permeability change is approximately negatively correlated with frictional stability when shear velocity is increasing, with outlier points related to factors such as roughness and fluid pressurization due to fluid injection. Data sources17,55,145,151,152.

The compiled data suggest two features: (1) in the case of fluid injection-driven fault slip, permeability enhancement does not depend on frictional stability, and (2) the relative permeability change of loading-driven fault slip in the laboratory is negatively correlated with frictional stability (Fig. 6)17,55,145,151,152. This prevailing negative correlation is not linear. At constant values of \(a-b\), a larger change in friction coefficient \(\Delta \mu\) indicates a more drastic dilation or compaction behavior. In addition, if the scaling coefficient \(\epsilon\) is negative in the velocity increase step, it is positive in the velocity decrease step152. Although the aforementioned experimental data and theoretical framework are consistent, the applicability of the cubic law warrants further discussion. In characterizing the porosity—hydraulic aperture—permeability relationship, the cubic law has been validated to apply for fractures, equivalent to young faults153. For faults filled with gouge, methods characterizing the porosity-permeability relationship include (1) the cubic law mentioned in this manuscript, (2) the Kozeny-Carman model154, and (3) empirical power laws153. The choice of method should be based on the fault structure and slip mode of the fault. It is worth noting that field friction-permeability experiments on faults have also adopted the cubic law in addition to laboratory experiments55,145,151,155,156. Here, we prioritize the cubic law in the seismicity-permeability coupling for several reasons: (1) The seismicity-permeability coupling is investigated from velocity steps. Repeated particle rearrangement and dilation promote fluid pathways146, which favor fracture-type flow and weaken the applicability of the Kozeny-Carman model. The Kozeny–Carman model is suitable for the permeability–porosity relationship in the case of packed uniform spheres157. (2) Even when gouge develops within the faults, most faults remain fractures partially occupied by particles. The permeability evolution of faults still complies with the cubic law, explaining why the cubic law is used in laboratory and field experiments shown in Fig. 6 at relatively smaller time scales. (3) Only when gouge forms a continuous, low-permeability smear that fully blankets the interface, matrix-type flow may dominate the hydraulic response of the fault. Otherwise, any connected pore space becomes a preferential conduit with a permeability several orders of magnitude higher than that of the continuous smear, thus determining the overall permeability of the fault. However, for observed repetitively reactivated and mature faults, it is still necessary to validate the applicability of the cubic law.

Controls on seismicity-permeability coupling

In this section, we review the effects of three key factors—mineral composition, temperature, and interface roughness—on the seismicity-permeability coupling. Since almost all experimental studies are conducted under constant effective stress conditions, the results reflect the actual response of faults where pore pressures equilibrate after hydraulic stimulation and tectonic stresses slowly adjust. At this point, the effect of pore pressure variation can be neglected. Analyses of stress gradient dependencies are systematically addressed in the temperature effects subsection. The seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of faults under varying normal stresses is reviewed in the next section.

Mineralogical effects

Mineralogical effects are usually reflected in differences in the crystal structure of minerals. The strength of the chemical bonds between atoms controls the resistance to asperity deformation, and parts of the crystal structure can form hydrogen bonds with intruding water molecules. The dissolution and precipitation of minerals may not be apparent in the short term and are highly dependent on the mineral composition of the fault and the fluid within it (Fig. 7). These phenomena described above alter the fault friction and the degree of fault opening. Friction-permeability experiments on Opalinus Shale (OPS) and Green River Shale (GRS) show that shear-generated wear particles with higher shear strength can insert into faults and exert a negative effect on continuous permeability reduction by shear. In contrast, weak faults show a faster permeability reduction due to their ease of deformation, which leads to a rapid decrease in fluid pathways41. Microscopic results also show that some particles swell in contact with water, blocking the fluid channels and exacerbating the decrease in permeability41. Mineralogical analyses and friction-permeability experiments suggest that the content of three mineral types may control the frictional stability and permeability of the rock samples. Phyllosilicate-rich faults show weaker strength and decreasing permeability with increasing slip rate, while tectosilicate-rich faults show higher strength and increasing permeability. These two group minerals show the inverse trend in frictional stability. The carbonate content does not show a distinct pattern in influencing the friction and permeability parameters, which may be due to the influence of the other two mineral groups or related to the dissolution and precipitation of the carbonates themselves17.

The strength of asperities or gouges directly controls dilation and compaction, wear product generation, and affects both frictional stability and permeability evolution. Dissolution, precipitation, swelling, and metamorphism of mineral particles also indirectly change the above behaviors of faults.

Experimental friction results for binary mixtures of minerals show that the minerals have a large influence on the frictional properties of faults158,159,160. The frictional stability of similar minerals is essentially the same despite the different frictional strengths shown161. It is a convenient but imprecise method to roughly infer the frictional properties of faults from their mineral composition. Even among minerals of the same type, there are still differences in parameters, and for an individual mineral, changes in elements (e.g., metal cations) can change the friction response. For example, kaolinite has a friction coefficient of about 0.3, whereas calcium montmorillonite has a friction coefficient of about 0.246. The stronger minerals result in greater shear dilation of faults during shear reactivation, implying that there is a positive effect of shear strength on permeability increase. Shear experiments on montmorillonite with four different cations showed that the higher the hydration energy of the cation, the larger the distance to the anion49. Larger voids between cations and anions can be more easily occupied by water molecules and thus reduce the shear strength of the mineral. Permeability does not increase as a result of an increase in these voids, while it is positively related to the frictional strength. For minerals with small interlayer voids (e.g., K-montmorillonite), fluid flows mainly in the external pores of the mineral; for minerals with large interlayer voids, fluid may flow in these voids, where electroosmosis can affect the permeability of the mineral49.

The spatial distribution of minerals also controls frictional stability and permeability, and this factor is considered an important difference between natural and laboratory faults59,60,162,163. A representative mechanism is the formation of fabrics: shear experiments on talc and quartz show that although the quantity of the low-strength mineral talc is relatively low, talc particles can also form fabrics dominating the strength of faults. A prerequisite for the fabric dominating the strength of the fault is that, despite the low content of weak minerals, sufficient thickness is required to ensure that the weak minerals are able to form a penetrating layer (A smear-like structure within the interface of faults) in the fault during shear63. Numerical modeling results indicate that sufficient thickness of weak minerals forms a deformation band for preferential sliding in faults and that the fabric formed by weak minerals dominates not only the frictional strength but also the frictional stability15.

In addition to heterogeneity along the perpendicular direction of the shear plane, heterogeneity parallel to the shear direction, such as patches of different minerals aligned along the fault orientation, also affects the mechanical response of the fault through another mechanism. Distinct from the strain concentration in weak minerals due to laminated textures (penetrating layers), several mineral patches differ in their normal deformation when simultaneously sharing shear strain, leading to stress localization that promotes faults to decline in strength and become unstable59,163. Numerical modeling restores a mechanism for the stability-depth inversion relationship, and the mechanism implies that a plastic matrix wrapped around brittle rock can lead to the generation of slow earthquakes164. Mineral composition variation implies that natural faults may exhibit more complex behaviors than laboratory ones. Thus, mineral effects should be divided into two scales: (1) microstructures composed of atoms, ions, and chemical bonds control minerals’ Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical-Chemical (THMC) responses; (2) spatial heterogeneity controls the interactions between mineral patches and then affects the responses of faults. Existing studies have explored the frictional stability and permeability of many common minerals and representative rocks. Using methods such as machine learning to predict stratigraphic details from limited geological data can facilitate the application of laboratory understanding to fault zones165,166.

Thermal effects

The thermal effects on an individual fault could be explored separately from each component: the first is the thermal degradation of host rocks due to high-temperature conditions, which will change the stiffness of fault systems, the P-wave velocity, and even the permeability of the host rocks. The second point is the temperature difference between fluids and host rocks, where the heat exchange may change the responses of host rocks and faults until temperature equilibrium is reached. Besides, repeated heating-cooling cycles have resulted in a large number of intercrystalline and intracrystalline cracks, which have the effect of reducing the frictional stability of granite faults and making faults exhibit generally larger permeability167.

The deterioration of the mechanical properties of host rocks can be attributed to two main causes: dehydration and expansion. Scanning electron microscopy observations of cracks indicate that the anisotropy of thermal expansion in individual mineral aggregates and the mismatch of thermal expansion in multi-mineral aggregates lead to the thermal stress concentration105. The thermal stresses, together with the particle type and the geometry of the particles, control the various boundary cracks and intracrystalline cracks in the aggregates presenting at discrete temperature intervals105. Thermal cracking may allow the rock matrix to become a major conduit for fluids due to the creation of numerous conductive microcracks168,169,170,171. Cracks within host rocks do not restore after they are created, so it is necessary to consider the effect of thermal history on rock properties172. The deteriorating effect of high temperature on host rocks will change the system stiffness of faults. When the ratio of the system stiffness \(K\) to the critical stiffness \({K}_{c}\) of the shear changes, the frictional behavior of the fault changes, which then triggers the change of permeability.

As anthropogenic fluid injection or natural fluid migration (e.g., fluid migration within a subduction zone) induces the shear sliding of faults, there would be a temperature difference between the host rocks and the abruptly intruding fluid. In addition, flow-through experimental results indicated that low water temperatures diminished the efficacy of pressure solution on minerals, resulting in incomplete healing of the cracks173. The introduction of a cooling fluid into a hot fault may result in the development of pore pressure anisotropy caused by the temperature differential. This phenomenon may lead to fault reactivation or even unstable sliding, and the subsequent shear heating allows the system to reach equilibrium. In another experiment regarding water injection-induced shear, it was confirmed that the discrepancy in rock and water temperatures resulted in greater shear displacement and permeability changes in the simulated fault, with permeability variations suggesting the presence of greater dilation of the simulated fault174.

The third key point is the examination of the coupled thermo-sensitive responses of friction and fluid properties within the context of the seismicity-permeability coupling. The brittle-plastic transition of the asperity contact is an important mechanism by which the elevated temperature affects the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior. At relatively lower temperatures and stresses, faults show asperity breakages and cataclastic flow during shear. As the temperature and stress continue to increase, plastic deformation, possibly caused by dislocation creep or diffusion creep, may become the dominant form of deformation in the asperity contact and change the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior175. The above mechanism explains the effect of temperature on the frictional response and the permeability evolution of rock interfaces and fault gouges. The friction data of rock interfaces and fault gouges under varying Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical (THM) conditions are compiled in Table 118,19,61,99,100,101,176,177,178,179,180,181,182, and the \(a-b\) values can be used in the scaling relationship to assess permeability evolution.

Fault roughness

The morphology of emerging faults reflects the process of rupture tip propagation. Extensive experimental and modeling work based on fracture mechanics has explored the possible morphology of emerging cracks, which we do not discuss further here. The fault surface is characterized by asperities ranging in height from micro-scale to meter-scale. Quantifying the morphological features of fault surfaces is challenging because the mapping between roughness indices (e.g., RMS) and different surface geometries is not unique. Characterizing the roughness of faults using fewer parameters that reflect both the height differences between asperities and the spatial distribution of asperities is another key to understanding the coupling of friction and permeability during fault shear. Several parameters have been used to measure the roughness of the rock cracks, namely the linear-average (LA) and root-mean-square (RMS) values of the height of the rough interface183, the parameters Z2, Z3, Z4 extrapolated from RMS184, and the structure-function (SF)185. In addition to being difficult to characterize, a second feature of roughness is that it changes with increasing shear displacement155. Therefore, it is essential to consider the displacement-dependent feature of this parameter in order to quantitatively analyze the influence of the roughness on the coupling behavior and even to predict its evolution.

The roughness gives rise to stress heterogeneity along the strike of the crack, and stress may even be localized to zero when the local interface separates186. Although the introduction of roughness parameters allows for predicting the peak strength of rock joints187, the stress heterogeneity induced by the crushing and interlacing of asperities in rough laboratory-simulated faults may lead to fluctuations in measured resistance and permeability145. The additional drag stress caused by rough walls may outweigh the friction when the slip magnitude is smaller than the wavelength of self-similar fractal roughness, while the fault resistance may still be dominated by friction when the slip is much larger than this wavelength70. In contrast, mature faults may show relatively constant friction and permeability evolution. The results of experiments and numerical simulations demonstrate that an increase in roughness leads to enhanced fault stability, and faults have similar residual friction that may be related to the fact that the fault gouge dominates the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior at the final stage145,188 (Fig. 8b–d). A numerical model shows that seismic nucleation on rough surfaces requires larger slip distances and that seismic rupture will not occur when the roughness resistance is larger than the static stress drop, showing a similar pattern to the experimental results189. Although a rougher sample shows higher frictional stability, the increased roughness cannot prevent rupture once stress exceeds the static friction threshold (Fig. 8b, c).

a Surface profiles for tests rss1-rss6, defining an increase in fault roughness with test ID. b Friction evolution of simulated faults for tests rss1-rss6. c Permeability evolution (\(k/{k}_{0}\)) of simulated faults for tests rss1-rss6. d Velocity dependence of simulated faults with different RMS heights188.

When the asperities are oriented perpendicular to the shear direction, the shear strength and permeability may show significant fluctuations due to the rearrangement of the upper and lower contacts. However, when the asperity orientation is parallel to the shear direction, the increase of the fractal roughness wavelength and the RMS height may increase the permeability due to the presence of larger hydraulic apertures and a connected fluid network within the fault. Although intensive shear may orient asperities in the direction of shear, given the heterogeneity of the minerals and the stresses, it is necessary to consider varying angles between the asperity alignment and the shear direction. Furthermore, the distribution of asperities within the faults leads to different specific stiffnesses, which results in diverse deformations of faults under the same stress condition and consequently produces permeability discrepancy190. In the case of natural faults, the effect of roughness on the coupled behavior of friction and permeability is negated by the gradual growth of the fault core through shear. Because the thickness of the fault gouge, which is positively correlated with shear distance, would govern the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of faults when the shear distance is sufficiently large63. The fault gouge can control the mechanical response of the fault and act as a barrier to the surrounding highly permeable damage zone if the fault gouge is coherent on the fault plane. In the case of an individual fault, shear force alters the roughness of the fault surface and the fluid network inside the fault, causing a variation in fluid conductivity. In summary, as one of the important features of natural faults, the influence brought by roughness cannot be neglected. The characterization of microstructure evolution on the rough surface with shear displacement may prove beneficial for a more precise delineation of the coupling behavior.

Implications for fault zones

The seismicity-permeability behavior is modulated by the coupled Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical-Chemical (THMC) impacts. The review of the above studies provides a potential method for assessing the fluid conductivity of fault zones based on the dilation and compaction during fault friction and elucidates several potential controlling mechanisms. Based on the flat panel model, the evolution of fault friction and permeability is simplified to interfacial friction and the opening or closing of a flat panel. Permeability evolution can thus be predicted from the velocity dependence of fault friction. Such laboratory-based laws and equations have the potential to be generalized to in situ observations and model calculations. By extrapolating the \(a-b\) values and openness of faults from inversion observations and combining them with permeability data, one can roughly obtain the scaling coefficients for seismicity-permeability coupling behaviors of faults191,192. The compilation of more data on friction properties and permeability evolution, i.e., supplementing Fig. 6 with additional field data, helps to constrain the range of scaling coefficients and to discover general patterns in the seismicity-permeability coupling of natural faults. It is worth noting that this scaling law does not apply to fault activities or seismic events directly induced by fluid injection. This means that the coupled friction-permeability data may help to distinguish whether the seismic events are directly caused by fluid injection. In contrast, this scaling relationship is particularly applicable to newly generated faults in reservoirs after hydraulic stimulation because hydraulic stimulation produces active faults similar to laboratory faults. In this case, the main factor driving the evolution of fault friction and permeability remains the coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical (THM) impact. Chemo-mechanical weakening can exacerbate the risk of caprock leakage; for example, supercritical CO2 can weaken fault friction, triggering its activation and shear dilation (Table 1)99. Understanding the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of fault zones and developing the aforementioned methodology facilitate comprehending the physical processes of natural earthquakes, assessing leakage from unforeseen capping faults, and evaluating variations of the hydraulic conductivity within the reservoir.

Seismicity-permeability coupling responses to earthquake cycles

Any complete earthquake cycle can be divided into three distinct phases: the inter-seismic period, the co-seismic period, and the post-seismic period, and these earthquake cycles could be irregular. The significant difference between the three phases lies in the slip pattern of the fault zone, with inter-seismic slip slowly accumulating strain on the fault and co-seismic slip rapidly releasing strain energy193. Thus, during the inter-seismic period, the fault plane is almost stationary due to the interlocking of asperities, whereas during the co-seismic period, the fault plane has a significant shear slip rate, and during the post-seismic period, the fault plane undergoes minor slip to adapt to the sudden change in the stress field resulting from the earthquake. This section will focus on the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of different phases during earthquake cycles.

Response to far-field earthquakes

Fault systems in the Earth’s crust interact with each other through stress transfer and fluid migration194. Stress oscillations are commonly used in laboratory experiments to model the response of fault systems to far-field earthquakes. This sub-section presents a discussion of both laboratory and field observations of the fault’s responses to far-field earthquakes. It is hypothesized that dynamic strain propagation from seismic waves is thought to be one of the mechanisms that trigger far-field earthquakes195. The observations of the Landers earthquake and far-field triggered earthquakes indicate that the generated dynamic stress is comparable to that inferred from empirical formulas based on the ground motion velocity and that this stress is insufficient to satisfy the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion alone196,197. Considering that the stress level of the fault may be approaching the critical state of failure, the dynamic stress may act as a trigger for, or in competition with other mechanisms, the unstable sliding of the fault. In subsequent studies, the concept of triggering thresholds has been proposed to distinguish between far-field faults that do and do not generate earthquakes and to emphasize the importance of the classical RSF law since some faults do not generate earthquakes after reactivation198,199,200. The triggering threshold of a fault system is related to a number of factors, including the frictional properties, the structural characteristics of the fault, the frequency of dynamic strain, and the velocity of dynamic strain198,199. It is important to note that the dynamic stresses inferred from field recordings are not completely accurate and that the use of stresses alone to predict the occurrence of earthquakes is inadequate. Laboratory experiments have shown that the fault elastic modulus decreases abruptly with perturbations of high-frequency dynamic stresses, which may be a potential mechanism for fault failure triggered by far-field earthquakes201.

The observation of the fault permeability in response to far-field earthquakes is difficult because there are still technical limitations in directly observing changes in flow through faults. The response of the crustal hydrological system to far-field earthquakes may be roughly observed through changes in water levels in wells, thereby suggesting insights into the responses of faults1. After quantifying the effects of rainfall and tides on water levels in wells, water level monitoring records show that far-field earthquakes result in an increase in water levels of wells, indicating an increased permeability in this geologic region1. Another study showed that natural faults continued experiencing stress relaxation and tremors for several years after the Parkfield and San Simeon earthquakes202. Responses similar to those of natural faults have been observed in pore pressure oscillation experiments conducted on cracked rocks203. The reduction in p-wave velocity that occurs during co-seismic slip suggests that the fault undergoes elastic softening, which is consistent with an increase in permeability of the natural hydrological system followed by a gradual decrease1,204 (Fig. 9). Understanding fault responses to far-field seismicity improves the leakage monitoring in confined reservoirs, the artificial stimulation reservoir production, and the interpretation of seismic triggering by fluid migration or stress perturbations.

a Phase offsets of earth tide water well responses show a sharp change (locations at the dashed line) concurrent with the timing of far-field earthquakes, indicating increased permeability of the hydrologic system1. Dashed line a shows the 1991 Sierra Madre earthquake, and line b shows the 1995 Joshua Tree earthquake1. b Reactivation of laboratory faults and measured increase in permeability showing larger increase in post-reactivation permeability for extended hold times of 104s (circle 8) versus short hold times of 101s (circle 1)205. c Reductions in seismic velocity concurrent with the seismic cycle indicate potential elastic softening effects on the San Andreas fault following two earthquakes and subsequent tremor rates caused by seismic perturbations. These remain for 3 years but decline over time202. d Changes in wave speed measured on laboratory faults in transiting the seismic cycle204.

Role of fault healing and reactivation

The investigation of the friction and permeability evolution of faults has been conducted through slide-hold-slide (SHS) experiments205. During these experiments, the normal displacement has been identified as a potential index for hydraulic aperture, although it may not be sufficiently precise. The inter-seismic behavior of faults demonstrates its dependence on stress, temperature, and some other factors. There is no significant correlation between the rate of fault healing and the magnitude of constant stress, but stress oscillations have been observed to enhance the healing effect of faults, with the amplitude positively correlated with the healing rate206,207,208. The enhancement of healing is linked to oscillation-induced mechanical consolidation, and a reduction in fault gouge porosity is observed during oscillation206. Humidity is another key factor that enhances friction healing, as evidenced by the comparison of saturation experiments with drying and stress-oscillation experiments209. It has been demonstrated that temperature does not significantly affect the frictional healing effect of dry powders, but it can enhance the healing effect by boosting the chemical reactivity of water, and the hydrothermal effect has been found to affect the static frictional strength and stability of faults125,210. A direct approach to analyzing the effect of chemical reactions is to analyze the effect of mineralogy on frictional healing. In general, minerals with higher frictional strength show higher healing rates46.

Although the flow-through experiments can provide some insights into coupling behavior, the limited method of monitoring friction and permeability evolution may result in a confined understanding of the behavior of natural faults. Frictional healing induces permeability to decrease during the quiescent phase by factors such as compaction, stress solution, and stress corrosion120,211,212,213,214,215. A distinctive feature of the inter-seismic period, as learned from laboratory faults, is that the processes of fault healing and permeability reduction are time-dependent214,216. The friction and permeability of the faults not only evolve over time but are closely associated with the reactivation of the faults. The enhancement of permeability during shear reactivation is matched to the frictional healing of faults during the inter-seismic period. Friction-permeability experiments show that the frictional healing, which occurs due to significant sealing, is followed by apparent breaching when the laboratory-simulated faults are reactivated (Fig. 9)205. The opening-up generated by reactivation is not always observed due to the prevalence of shear-induced comminution41,205. Similarly, there is a cutoff time for friction healing, under which no significant healing effect can be observed. The cutoff time for friction healing was identified during the process of exploring the effect of variables (e.g., humidity, temperature) on healing, and it was found to be correlated with the previous rate variable209,217,218. An increase in critical slip distance \({D}_{c}\) and a decrease in stable slip velocity \({V}_{{ss}}\) would correspond to a large cutoff time value, which is consistent with the recurrence time observed in periodic stick-slip motion simulations128. The recurrence and magnitude widely observed in natural seismic events219,220 correspond to the general characteristics of stick-slip observed in the laboratory, which is based on a one-dimensional block-slider model.

Role of fault valving

In addition to the impact of seismicity on permeability, permeability may also exert a feedback effect on seismicity. Fault valving is a phenomenon whereby alternating overpressures are released within a fault by rupture221. It is a common occurrence in hydraulically stimulated reservoirs as well as subduction zones. In addition to triggering fault instability, fault valving affects the degree of fault locking, which is reflected by the acoustic wave velocity ratio and affects the slip distribution during large earthquakes222,223. Seismic sequence models considering fault valving demonstrate that overpressure pulses in inter-seismic periods can subsequently trigger aseismic slips, seismicity swarms, and slow slip events that are more likely to occur under high-temperature conditions150. Furthermore, the propagation of stress fronts from overpressured zones may trigger earthquakes outside them224. A study of the opposite mechanism suggests that the slip behavior of faults may also be controlled by the permeability and porosity of the faults, which in turn influences the fluid overpressure and release processes on the faults24. This emphasizes the role of fluid in controlling the response of fault friction and the bidirectional coupling of seismicity and permeability150,224,225.

It is worth noting that these studies are primarily focused on subduction zone faults, but the conclusions may remain applicable to faults in reservoirs and caprocks. The impacts of fault valving caused by fluid migration or dehydration reactions can also be found in reservoirs undergoing fluid stimulation226. The majority of human-induced earthquakes are thought to be triggered by injection operations interacting with critically stressed faults, such as the Mw 5.5 Pohang earthquake in 2017227,228. Thus, these insights are also applicable to understanding the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of faults in reservoirs and caprocks. However, these insights cannot be directly extrapolated to the scaling relationship between \(a-b\) and permeability, as the fluid pressurization/depressurization during the seismic triggering phase is not directly related to permeability. There are multiple seismic mechanisms that can explain fault instability, and these mechanisms may have significantly different effects on permeability evolution25,229.

Implications for fault zones

The above subsections have identified a multitude of mechanisms for seismic recurrence, as well as competing effects between continuous sealing and intermittent breaching on permeability. Some fault instability mechanisms can no longer be explained by the friction-permeability experiments under constant normal stresses, rendering the scaling formula inapplicable25,26,225. A stress-, temperature-, rate-, and state-dependent friction law and a more complex scaling relationship may hold potential for describing a broader spectrum of seismicity-permeability coupling behaviors. Field observations and laboratory studies show a distinct feature of faults in the cyclic activation and healing processes. During the inter-seismic period, the closure of the fault has a power rate relationship with time during the inter-seismic period, while post-activation permeability transiently increases and then rapidly decreases205. This implies that faults could leak substantial fluids during activation due to permeability increases of several orders of magnitude. Conversely, cyclic pore pressure perturbations will induce elastic softening of the fault, triggering fault slip and playing an important role in stimulating the reservoir to maintain great fluid conductivity. These insights are consistent with a number of reservoir stimulation strategies, such as stepwise pulse pressurization and cyclic pulse pressurization230, which can avoid caprock failure by limiting overpressure whilst sustaining conductivity. The following points may further revolutionize the existing understanding: (1) The quantitative analysis of frictional strength and permeability evolution of natural faults still needs to be further developed. (2) The potential effects of friction healing on large-scale faults still need to be further investigated and validated using field data.

Summary

This article reviews the basic theories, experiments, and numerical simulations pertaining to the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of faults. A common perception is that seismic events may be accompanied by increased permeability. We suggest that the factors that significantly influence the coupled seismicity and permeability evolution of faults in breaching and sealing are minerals, roughness, and temperature, respectively. These factors, in conjunction with geological settings and fluid injection strategies, serve to determine the seismic potentials and hydraulic responses of fault zones. The specific conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The seismicity-permeability coupling response of faults is influenced by coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical (THMC) effects. Mechanical responses and healing mechanisms of diverse mineral phases under different temperature-stress conditions influence fault friction and permeability responses.

-

(2)

Roughness is another important parameter linked to the maturity of the fault. Incipient faults with friction dominated by bare interfaces show significantly different seismicity-permeability coupling behavior than mature faults with friction dominated by fault gouge. This difference should be used as a basis for classifying faults when discussing their seismicity-permeability coupling behavior.

-

(3)

The seismicity-permeability scaling relationship derived from experimental studies is applicable to faults where the effect of effective normal stress changes is negligible, but not to faults where pore pressure changes directly trigger reactivation and instability.

-

(4)

The breaching and sealing responses of the faults reveal the evolution of fault permeability during the seismic cycle, i.e., faults show significant permeability enhancement after activation, followed by a gradual decrease during the stationary period. In addition, pore pressure perturbations enhance and maintain fault permeability.

Future work should also focus on the following points:

-

(1)

The application of laboratory-obtained seismicity-permeability scaling relationships to fault zones still requires the compilation of additional friction and permeability data. These data can come from the analysis of geological observations or from field experiments.

-

(2)

The scaling relationship discussed in this paper only considers shear-induced dilations and compactions of faults, and the relationship is derived from studies conducted under constant normal stresses. In fact, there are current studies that analyze the seismicity-permeability coupling behavior of faults under non-constant effective normal stress (e.g., pore pressure perturbations). Proposing a stress-dependent seismicity-permeability scaling relationship can extend the application value of the currently discussed scaling relationship.

-

(3)

The damage zone has an important effect on the variability of permeability and pore pressure137, which is not captured in the main studies we reviewed. The influence of damage zones on the coupled seismicity-permeability behavior of faults remains a worthwhile area for future exploration.

Data availability

This article presents no additional data except for data cited from published articles.

References

Elkhoury, J. E., Brodsky, E. E. & Agnew, D. C. Seismic waves increase permeability. Nature 441, 1135–1138 (2006).

Manga, M. et al. Changes in permeability caused by transient stresses: field observations, experiments, and mechanisms. Rev. Geophys. 50, RG2004 (2012).

McClure, M. W. & Horne, R. N. Investigation of injection-induced seismicity using a coupled fluid flow and rate/state friction model. Geophysics 76, WC181–WC198 (2011).

Scuderi, M. M. & Collettini, C. The role of fluid pressure in induced vs. triggered seismicity: insights from rock deformation experiments on carbonates. Sci. Rep. 6, 24852 (2016).

Yu, P. et al. Crustal permeability generated through microearthquakes is constrained by seismic moment. Nat. Commun. 15, 2057 (2024).

Brodsky, E. E. A mechanism for sustained groundwater pressure changes induced by distant earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2390 (2003).