Abstract

Decarbonizing global shipping is crucial to achieving international climate goals. However, efforts in this field may be inhibited by geopolitical risks that profoundly affect global shipping. Here, we use natural language processing on an over 500-million-word corpus to quantify the shipping decarbonization attitudes of 52 countries. Using a causal inference approach, we provide evidence that geopolitical risks exert a substantial and statistically significant negative impact on national decarbonization willingness. This dampening effect threatens to delay the International Maritime Organization’s timeline for zero-carbon shipping. Causal evidence also reveals that countries facing geopolitical tend to prioritize economic efficiency over environmental concerns, particularly those with high levels of maritime trade, economic development, and carbon intensity. We further validated these shifts by analyzing carbon dioxide emissions of global vessel navigation. This study highlights the urgent need to bridge geopolitical divides to achieve the ambitious target of zero-carbon emissions in global shipping by mid-century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global shipping, accounting for ~3% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions1, poses an urgent climate challenge in a world striving for deep decarbonization2. As the world intensifies its efforts to combat climate change, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), responsible for regulating global maritime transport, has continuously updated its objectives. The current goal is to achieve zero-carbon emissions by 2050, thereby deepening shipping’s contribution to climate mitigation3. However, decarbonizing global shipping faces significant challenges4. Some challenges have been widely discussed. For example, long-term projections under different scenarios for global trade reveal a 1–5-fold increase in future seaborne trade5,6. This growth implies that the shipping sector will require amounts of alternative energy, low-emission technologies, more efficient design, and upgraded port infrastructures to offset the effects of trade growth and meet the IMO 2050 goals7,8. However, the development of these alternatives remains nascent, requiring substantial investments of time and financial resources from nations to bridge the current implementation and ambition gaps9,10,11,12.

Geopolitical risks are emerging as another critical challenge to decarbonization efforts in global shipping. Geopolitical risk denotes systemic disruptions arising from interstate conflict, territorial disputes, economic sanctions, regional instability, or armed confrontation, and is commonly classified into action risks (e.g., military interventions, sanctions) and threat risks (e.g., terrorism, regional instability, and rising nationalism)13. These risks disrupt global trade flows, alter shipping routes, and affect fuel supply chains14,15,16, all of which contribute to fluctuations in maritime carbon emissions. For instance, recent geopolitical events, such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the tensions in the South China Sea, and the Palestine-Israel conflict, have forced vessels to take longer, less efficient routes, thereby increasing carbon emissions17,18. Additionally, geopolitical crises force countries to focus on domestic and regional issues, particularly basic security concerns like energy and food. This shift in focus could lead to a slowdown in global technological development, casting doubt on future progress and investment in decarbonization technologies9. Beyond physical disruptions, more critically, geopolitical risks could influence nations’ willingness to collaborate on decarbonization initiatives, undermining collective efforts to achieve climate targets19.

Recent work examines the localized impact of geopolitical events on maritime operations and concerns about the decarbonization process20,21. Studies by Lyu et al.22, and Xu et al.23 quantified CO₂ increases from rerouted shipping lanes during the Russia–Ukraine conflict and Red Sea crisis, while Shapovalova et al.24 and Hoffart et al.25 demonstrated how sanctions, disrupted fuel corridors, and geopolitical uncertainty alter fuel procurement patterns and delay emissions reduction strategies. However, systematic analyses remain scarce regarding how geopolitical risks reshape national decarbonization commitments across diverse contexts, which is a critical gap given that policy ambition drives sectoral transitions26,27.

However, quantitatively assessing the impacts of geopolitical risks on shipping decarbonization efforts is constrained by two main obstacles: First, establishing a robust causal link requires moving beyond traditional spatial emission attribution to actor-level time-series data, which is essential for causal verification. Existing studies have primarily examined localized shipping emission shifts around major geopolitical events28,29. Although extensive Automatic Identification System (AIS)-based ship emission datasets can capture immediate changes30, they fail to establish causality and remain largely observational. Second, the delayed effects of geopolitical risks are difficult to capture, resulting in a notable gap in longitudinal and cross-national comparative studies. Geopolitical risks exert a long-term impact through structural shifts in global trade and energy markets, reshaping national decarbonization strategies such as maritime operations, fuel procurement strategies, green technology investments, and international climate cooperation31. Nations’ decarbonization efforts vary due to differing geopolitical pressures and environmental priorities, further underscoring the need for research on their evolving and heterogeneous impacts.

This study addresses these gaps by answering a research question, to what extent do geopolitical risk influence the willingness of countries to reduce emissions in the maritime sector? We constructed a dataset of 518,190,352 words from 52 countries and ten major shipping media outlets between January 2010 to April 2024. Using natural language processing (NLP), we assessed attitude shifts towards decarbonization at both general and national levels. We then employed quasi-experimental causal inference to evaluate the effects of geopolitical risks including benchmark, multi-period and heterogeneity analyses. We validated the effects by analyzing actual CO2 emissions of global vessel navigation based on the updated Ship Traffic Emission Assessment Model (STEAM) model. The algorithmic framework and model evaluation are described in the Methods.

Our findings indicate that geopolitical risks can reduce national willingness to decarbonize, with heightened geopolitical risks contributing to the further deterioration of decarbonization attitudes. To validate this causal relationship, we analyzed global shipping carbon emissions and found that geopolitical risks escalate emissions and reshape long-term emission patterns. Moreover, the effects of geopolitical risks vary across countries. Nations with substantial maritime trade, advanced economies, and high carbon intensity are more likely to prioritize economic stability and security over environmental goals. When combined with existing research32, our results suggest that this decline in decarbonization ambition could potentially delay the IMO’s zero-carbon target by up to 50 years. In so doing, this research provides critical insights for policymakers seeking to navigate the complex intersection of climate action and international relations.

Results

Temporal trends in attitudes towards shipping decarbonization

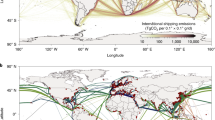

To examine the spatiotemporal evolution of the shipping decarbonization attitudes under varying geopolitical risks exposure, we utilized nation-level decarbonization attitude scores derived from NLP-based sentiment analysis of news text big data alongside the Geopolitical Risk Index developed by Caldara and Iacoviello13. The national decarbonization attitude score ranges from −1 to 1 and is proxied as the ratio of the total sentiment score of all text documents in that country for the year to the total sentiment score of all countries worldwide. It reflects the overall attitude of stakeholders or practitioners in the country’s shipping industry toward decarbonization goals, ranging from positive to negative or neutral, which affects the efficiency of their subsequent decarbonization actions. Figure 1a reveals a strong correlation between major geopolitical events and shifts in decarbonization attitudes. Before 2019, attitudes exhibited moderate fluctuations, reflecting a gradual alignment with climate goals. However, post-2019, geopolitical tensions increasingly overshadowed environmental priorities, underscoring the challenge of sustaining momentum amid crises. The 2022 Russia–Ukraine conflict marked a turning point, triggering a pronounced and sustained decline in attitude scores across many nations from an average of 0.707 to 0.556. Subsequent events, including the Nord Stream pipeline explosion and the Palestine–Israel conflict, further exacerbated negative trends.

a It reveals the time-series evolution of the shipping sector’s decarbonization attitude and geopolitical risk. The timeline above the graph highlights major global geopolitical events. Geopolitical risk (global) is represented by a dark blue line. The red line represents the global sentiment score, indicating the decarbonization attitudes of the shipping sector. A lower score indicates a less positive attitude towards decarbonization within the shipping sector. b Presents the changes in national decarbonization attitudes and geopolitical risk index. Subregions I–III present the assessed countries from selected parts of Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia. Specifically, Subregion I comprises the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Oman; Subregion II comprises the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Belgium, France, Spain, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, Switzerland, and Greece; and Subregion III comprises Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia. Blue dots represent each country’s attitude score for the respective year. Map colors correspond to changes in each country’s geopolitical risk. The changes in the geopolitical index at the national level from 2010 to 2023 can be examined in Supplementary Fig. 11. We use 2021 as a pivotal year for the calculations, averaging the three years before and after this point. The mutation year is detected using Mann-Kendall trend examining (Supplementary Methods 4).

Figure 1b illustrates the geographical variations of geopolitical risk and annual decarbonization attitude across selected countries. The geopolitical risk index exhibits a general increase, with a more pronounced rise in the Global North compared to the Global South. Specifically, regions such as Europe, East Asia, and North America display increases in geopolitical risk, with countries like Russia, and the United States exhibiting particularly high levels of risk escalation. This disparity underscores differing geopolitical pressures between the Global North and Global South.

The line graphs for each country reveal the temporal dynamics of national decarbonization attitudes. Key observations indicate greater volatility and frequent changes in decarbonization attitudes until 2018, likely reflecting evolving policy responses and strategic adjustments as nations established frameworks for shipping sector decarbonization. However, the shipping industry’s attitude toward decarbonization has improved since 2018. This is mainly due to two factors: the greenhouse gas emission reduction strategy adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has catalyzed relevant international green shipping policies, and green shipping investment has undergone a structural transformation. Specific instances include: the launch of the global ship financing initiative known as the “Poseidon Principles” and the active response from financial institutions; the signing of the “Clyde Bank Declaration” by 22 countries to jointly build a “green shipping corridor”; and the rapid development of green shipping finance—the issuance of the industry’s first green bond by Japanese shipowner NYK Line is a clear testament to this. Nevertheless, a discernible deceleration in decarbonization momentum is observed post-2020. This slowdown is particularly evident in several Global North countries, such as European nations and Middle Eastern states, where heightened geopolitical risks appear to coincide with a diminished commitment to decarbonization. In Europe, for instance, countries like the United Kingdom, Germany, and France exhibit a decline in the growth rate of decarbonization attitudes after 2021. Similarly, Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates display a notable decline. Conversely, countries in Southeast Asia (such as Thailand, Singapore, and Indonesia) display more consistent and less volatile decarbonization attitudes, with comparatively subdued changes.

Detecting the impact of geopolitical risks on national decarbonization attitudes

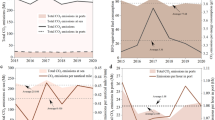

We quantify the causal relationship between geopolitical risk and national decarbonization attitudes using a difference-in-differences analysis with staggered treatment (staggered DID) analysis (see “Methods”). Figure 2 presents the empirical regression results and parallel trends test results. Figure 2a reports the main estimates, incorporating nation-level control variables. The coefficient of Geo_risk×Intensity is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. Specifically, the result indicates a decrease of 14.38 percentage points in decarbonization attitudes following the treatment.

a Reports the benchmark regression results. The length of the line represents the 95% confidence interval. The dots indicate the median values, where the coefficient of the benchmark regression is taken. The thickness of the lines corresponds to significance levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively. b Presents the parallel trends test results (detailed in Supplementary Results 1). The length of the line represents the 95% confidence interval. The dots indicate the median values, from which the regression coefficients are derived. c Provides the detailed regression results, with all regressions controlled for country and time fixed effects.

Figure 2b provides support for parallel trends, the main causal assumption of DID designs, which requires that treatment and control groups follow similar outcome trends before the intervention, thereby allowing post-treatment divergence to be attributed to the causal effect. Prior to the occurrence of geopolitical risk (−1 Period), the coefficient estimates are insignificantly different from 0, indicating no significant difference between the treatment and control groups before the shocks. Following the onset of geopolitical risk, the decarbonization attitudes decrease significantly in the sample experiencing geopolitical risk, consistent with the benchmark regression results. Figure 2b further illustrates a persistent negative shift in decarbonization attitudes following major geopolitical disruption.

Figure 2c provides the detailed benchmark regression results, with all regressions controlled for country and time fixed effects. The estimates remain consistent across different controls, underscoring the detrimental effect of geopolitical risks on national decarbonization attitudes. Columns (1) to (2) show the effect of non-intensity geopolitical risk, measured as the average risk level for each country over the study period. Columns (3) to (4) examine the impact of intensity geopolitical risk, measured by multiplying the mean value by the corresponding annual geopolitical risk level. The coefficients of intensity geopolitical risk (columns 3 and 4) amplify both the significance and scale of the observed impacts, emphasizing the instantaneous impact of geopolitical risks on national decarbonization attitudes. Columns (2) and (4) include nation-level control variables to account for additional factors that may simultaneously affect a country’s decarbonization attitude. All coefficients are negative and statistically significant at the 5% level or better. Specially, the coefficients of Port development and Carbon peak are negative and significant at the 1% level, indicating that countries with higher port throughput and peak carbon dioxide emissions are more susceptible to geopolitical risks, causing them to waver their decarbonization stance. This finding provides empirical evidence for the Tragedy of the Commons in the current climate actions of the shipping sector.

Comprehensive robustness tests reinforce the reliability and validity of our findings (see Supplementary Results 2).

We also observe pronounced temporal volatility in national maritime decarbonization attitudes in Fig. 1b, which may reflect the sensitivity of sustainability commitments to evolving geopolitical dynamics. To further explore this relationship, we performed a staged regression analysis to examine how the causal relationship between geopolitical risk and national decarbonization attitudes evolves over time. We divided the time period into three distinct time spans: 2010–2013, 2014–2017, and 2018–2021. As shown in Fig. 3, geopolitical risks had no significant impact on national decarbonization attitudes in the first stage (Column 1). However, in the second and third stages (Columns 2 and 3), the coefficients of Geo_risk×Intensity are all negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, with geopolitical risks in the third stage exerting increasingly detrimental effects. This suggests that geopolitical risk has a significant impact on national decarbonization attitudes, and this impact deepened over time.

We conducted another two-stage regression analysis, excluding the initial period of 2010–2013. The remaining time period was divided into two equal spans: 2013–2018 and 2018–2023. The coefficients of Geo_risk×Intensity are consistently negative and statistically significant (Columns 4 and 5), indicating a causal relationship between geopolitical risk and diminishing national decarbonization attitudes. We observe a statistically significant relationship at the 1% level in the later stages, reflecting a stronger causal link between geopolitical risks and declining decarbonization attitudes over time. It suggests that heightened geopolitical risks substantially contribute to the deterioration of decarbonization attitudes. This can be attributed to the marked increase in geopolitical risks post-2021, driven by a higher frequency of global geopolitical events (see Fig. 1a). However, this effect diminishes in the second period, comparing −0.1591 and −0.1285. As discussed in reference to Fig. 1b, IMO has adopted a more comprehensive and frequent set of climate-responsive measures since 2018. This suggests that climate policies need to be continuously strengthened and monitored to effectively counteract external risks.

The heterogeneity in national decarbonization attitudes

Building on the benchmark and multi-period regression analyses, we proceed to examine how national decarbonization attitudes vary across countries when confronted with geopolitical risks, thereby providing a deeper understanding of heterogeneous responses. To examine these differences, we classified countries into two groups: the top 50% and the bottom 50%, which enables us to highlight the variations between nations with differing economic scales, military strengths, and cultural backgrounds in their responses to geopolitical challenges. Detailed indicator settings and regression results are provided in Supplementary Results 2.

Figure 4 illustrates the heterogeneity analysis of national decarbonization attitudes in response to geopolitical risks, highlighting how different countries are variably affected by national characteristic factors. The coefficients for almost all groups are significantly negative, revealing that increased geopolitical risk correlates with a decline in decarbonization willingness. However, the degree of this effect varies significantly across nations.

The green dots represent macroeconomic and institutional factors, the orange dots represent military and social stability, and the purple dots represent religious and cultural factors. The length of the line represents the 95% confidence interval. The dots indicate the median values, from which the regression coefficients are derived. The thickness of the lines corresponds to significance levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively. The detailed regression results can be found in Supplementary Results 3.

First, we examined the level of economic development, degree of openness, and carbon emission intensity to analyze the heterogeneity of national decarbonization attitudes influenced by national macroeconomic and institutional factors. The coefficients for all groups are significantly negative, with the high groups being significant at the 1% level and lower than those of the low groups. This indicates that countries with higher levels of economic development, greater openness, and higher carbon emission intensity are more likely to scale back their decarbonization ambitions in response to geopolitical risks. This trend underscores the complex relationship between economic structures, energy intensity, and climate policy willingness, especially in the context of global geopolitical volatility.

Second, we explored the heterogeneity of national decarbonization attitudes influenced by national military capabilities and social stability by examining three indicators: military expenditure (MEP), quantity of weapons purchased (QWP), and the origin of refugees (ROI). The coefficients for all groups are significantly negative. Notably, the coefficients for Low_MEP and Low_QWP show greater reductions, with average decreases of ~20.21% and 17.73%, respectively. The coefficient of High_ROI is lower than that Low_ROI, with an average decrease of ~17.17%. This indicates that countries with certain military and social stability characteristics are less prone to reduce their decarbonization ambitions in response to geopolitical risks. It suggests that countries facing greater social and political pressures prioritize maintaining social stability, potentially limiting the impact of geopolitical risks on their decarbonization commitments.

Finally, we investigated the impact of religious and cultural factors, including religious populations (RPO), power distance (PDI), and uncertainty avoidance (UAI). The findings highlight the importance of religious and cultural factors in shaping national responses to geopolitical crises, revealing that such factors can influence policy decisions in diverse and complex ways. The coefficients for RPO groups are all significantly negative, with a decrease of 18.91% for Low_RPO compared to a 14.74% decrease for High_RPO. The coefficients of Low_PDI and Low_UAI are negative and significant at the 1% level, while no significant causal effects were found in the high groups. The results indicate that cultures with more evenly distributed power and higher risk tolerance may be more adaptable in adjusting their decarbonization policies in response to external geopolitical factors. In contrast, no significant causal effects were found in the high groups of PDI and UAI, suggesting that countries with higher PDI (more hierarchical societies) and higher UAI (greater resistance to change) may be less responsive to geopolitical risks when altering their decarbonization objectives.

Verifying the association between carbon emissions and geopolitical risks

Building on our earlier findings on the evolving attitudes toward shipping decarbonization and the disruptive role of geopolitical risks, we provide empirical evidence linking these risks to actual shifts in global shipping emissions. Drawing from a comprehensive dataset of over 100,000 vessels, we quantified the impact of geopolitical crises on maritime CO₂ emissions and carbon intensity (DIST). This analysis demonstrates how geopolitical instability reshapes shipping CO2 emission patterns (see “Methods”).

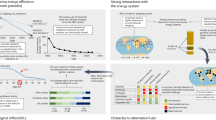

Figure 5 highlights that geopolitical risks have led to an overall increase in carbon emissions, reinforcing the observed decline in decarbonization ambition. While regional conflicts, such as the Russia–Ukraine conflict (Fig. 5a) and the Nord Stream pipeline explosion (Fig. 5b), resulted in moderate emission increases, disruptions within major shipping corridors induced far greater surges in both total CO₂ emissions and carbon intensity across vessel types worldwide (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Figs. 12–17). This pattern reinforces our earlier findings that nations with high trade dependence tend to deprioritize decarbonization efforts amid geopolitical uncertainty. This is evidenced by increased emissions along key shipping corridors and a heightened reliance on carbon-intensive trade routes following geopolitical disruptions.

a–c Represents the spatial changes in the six months before and after three major geopolitical events. a Russia–Ukraine conflict. b Nord Stream pipeline blast. c Palestine–Israel conflict. The enclosed numeric represents thirteen major maritime chokepoints. Subplot magnify the spatial coverage of each maritime chokepoints to display their shipping CO2 emissions explicitly. The thirteen maritime chokepoints are 1-Panama Canal, 2-Strait of Gibraltar, 3-Turkish Straits, 4-Suez Canal, 5-Strait of Bal-el-Mandeb, 6-Strait of Hormuz, 7-Strait of Malacca, 8-Danish Straits, 9-East China Sea, 10-South China Sea, 11-Cape of Good Hope, 12-Cape Horn.

Specifically, the escalation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, compounded by the Nord Stream pipeline blast, triggered a 1.5% increase in global shipping CO2 emissions (Fig. 5a, b). This pattern was reflected across most major shipping chokepoints, where emissions rose by 1.4% to 15.3%, with energy transport vessels being particularly affected (detailed in Supplementary Figs. 12–17). The outbreak of the Palestine–Israel conflict led to a substantial increase in carbon emissions from vessels compelled to navigate alternative routes around the Cape of Good Hope on Pacific and Indian Ocean routes (Fig. 5c). Carbon emissions from vessels transiting the Cape of Good Hope (chokepoint 12 in Fig. 5c) increased by 61.3% over a six-month period. Notably, shipping emissions between October 2023 and April 2024 rose by 1.36 million tonnes compared to the same period in the previous year.

Concurrently, the carbon intensity indicators DIST and TIME experienced increases of 9.40% and 35.96%, respectively, reaching 28.71 tonnes CO₂ per nautical mile and 0.51 tonnes CO₂ per hour. Simultaneously, ship carbon emissions exhibit a distinct north-south divergence. Carbon emissions from vessels originating in Europe declined, whereas emissions from vessels from West Africa saw a increase. These findings reinforce our earlier analysis, which highlighted the heterogeneous nature of national decarbonization responses to geopolitical risks. While some nations intensified their reliance on carbon-intensive trade routes, evidenced by rising emissions along major shipping corridors and increased energy transport disruptions.

Discussion

Identifying factors that hinder climate goals is crucial for guiding policymakers toward effective interventions. Our quantitative analysis reveals two critical findings: geopolitical risks substantially reduce national willingness to decarbonize the shipping sector, whilst current geopolitical events are causing continuous increases in shipping carbon emissions. This aligns with predictions that countries’ self-determined contributions might be insufficient to limit global warming to below 2 °C2,33.

Our research establishes geopolitical risks as primary drivers of divergent national decarbonization attitudes, shifting focus from purely economic or technological explanations to international relations and power dynamics. We estimate that a unit increase in geopolitical risk corresponds to a 14.38% reduction in national decarbonization willingness. Combined with existing studies11,32,34,35, this suggests the IMO 2050 goals may be delayed by up to 50 years, rendering them nearly unattainable. This alarming decline in ambition, despite continued commitments to IMO2050 goals, underscores the need for policies that can withstand geopolitical pressures.

These impacts stem from the temporal misalignment between policy priorities36. Geopolitical risks necessitate short-term strategic responses, whereas maritime decarbonization requires sustained, long-term, and transnational efforts. This compels nations to prioritize immediate security needs over environmental objectives during instability, consistent with emergency response theory37,38. Realist international relations theory views states as the primary actors in global affairs, prioritizing national interests, production, and commerce39. The divergence between the urgent nature of geopolitical crises and the long-term focus of decarbonization goals introduces a systemic vulnerability in global environmental policy40. Each government prioritizes gains and losses differently, and these differences have been neglected in previous research and policy-making. The current global geopolitical environment prioritizes external security, making international climate action more economically and strategically driven. This reveals an inherent contradiction in the global governance framework. Furthermore, this challenge is exacerbated by the uneven distribution of geopolitical risks across different regions, leading to varying levels of commitment and progress in achieving decarbonization goals.

Meanwhile, we found that the impacts are not uniformly distributed. Several Asia–Pacific and American countries maintained relatively stable decarbonization responses, likely due to geographical and political insulation from direct geopolitical shocks. And, countries with stable social environments, high-quality governance, strong environmental regulation, robust military capabilities, and high cultural levels demonstrate better resilience to geopolitical disruptions. This regional heterogeneity underscores the complex influence of geopolitical risks on the global decarbonization agenda. However, our analysis also reveals shifts in emissions towards the Global South, potentially reconfiguring the global shipping landscape. Traditional maritime hubs are losing strategic relevance while new routes and nodes emerge11,41. This transition poses crucial challenges, as investments in low-carbon technologies in these regions remain insufficient34,35,42. This further complicates global coordination efforts.

The IMO’s more robust climate-responsive actions after 2018 appear to partially shield national decarbonization attitudes from geopolitical risks, as evidenced by the reduced magnitude of impact (−0.1285) after 2018. However, these policies require continuous strengthening to effectively counteract external risks. Addressing geopolitical challenges necessitates a fundamental transformation of global governance, promoting collective incentives through binding agreements, equitable carbon pricing, and transparent accountability mechanisms43.

However, countries with high trade volumes and emissions may prioritize addressing trade uncertainties during geopolitical crises, undermining decarbonization ambitions, as supported by the observed heterogeneity and the robust statistical significance of several control variables. This exemplifies the “Tragedy of the Commons” on a global scale, highlighting challenges posed by ambiguous liability frameworks and delayed implementation of carbon pricing44. Additionally, the shift in emissions towards Global South raises concerns about equity and accountability, as these developing economies face the dual challenge of expanding global trade participation while meeting decarbonization demands5,45,46.

We demonstrably observe that geopolitics has led to noticeable decline in national ambition. Furthermore, the shift in emissions towards Global South raises pressing concerns around equity and accountability. Current decarbonization framework risks placing disproportionate burdens on these nations without offering sufficient support47. To address this imbalance, international alliances must prioritize equitable access to green technologies and financing mechanisms. Without such interventions, global shipping decarbonization may become yet another reflection of global inequality48. Specifically, geopolitical risks may escalate shipping emissions, threaten marine fuel supply chain security, and undermine global decarbonization momentum, necessitating multi-tiered policy interventions: Short-term mandates include enforced speed reduction/optimization with fiscal subsidies or partial EU ETS allowance exemptions for diverted vessels, coupled with establishing clean fuel zones on critical diversion routes granting priority passage or port fee reductions for green ammonia/methanol-powered ships; Long-term reforms involve accelerating green bunkering infrastructure at high-risk chokepoints under Green Corridor initiatives, harmonizing IMO’s net-zero framework with EU carbon pricing while channeling allowance revenues into decarbonization tech cooperation for developing nations, and enhancing supply chain resilience through scaled domestic LNG production and supplier diversification—ultimately transforming geopolitical crises into catalysts for accelerated decarbonization. We underscore that the scale and complexity required to achieve decarbonization goals are underestimated, highlighting the necessity of bridge geopolitical divides to meet the ambitious target of zero carbon emissions by mid-century.

Conclusions

This study offers empirical evidence that geopolitical risks impede national efforts to decarbonize the maritime sector. By integrating large-scale NLP with quasi-experimental causal inference, we quantify a 14.38% reduction in national decarbonization willingness following a one-unit increase in geopolitical risk—potentially delaying the achievement of the IMO 2050 target by up to five decades. We further demonstrate that these risks are associated with a measurable rise in global shipping emissions, underscoring the need to account for geopolitical uncertainty in climate governance. Methodologically, this research moves beyond conventional event-based approaches, providing a novel framework to systematically capture attitudinal shifts and estimate causal effects at scale.

Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. While our design ensures rigorous identification of causal relationships, it does not capture the institutional or stakeholder-level dynamics that shape decarbonization responses in practice. Additional factors influencing attitudes toward shipping decarbonization, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, were omitted from the model as they lie outside this study’s primary focus. Moreover, given the inherently multidimensional nature of geopolitical risk, data limitations regarding event scale, economic impact, and geographical coverage prevented comprehensive characterization of its full scope. Qualitative studies, such as interviews with policymakers and industry actors and case study, could enrich understanding of how geopolitical concerns are interpreted and navigated. In addition, the scope of our analysis is limited to the 2010–2024 period due to data availability; the rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape beyond this window warrants continued monitoring.

Future research could extend this framework to dynamically track emerging geopolitical shocks in near real time, and to assess their influence on other hard-to-abate sectors such as aviation and heavy industry. Such efforts would help evaluate the broader resilience of global decarbonization pathways amid persistent geopolitical uncertainty.

This work seeks to advance the growing recognition that geopolitical dynamics are not ancillary, but rather integral to shaping the pace and trajectory of global climate action. By highlighting the structural vulnerabilities of the maritime decarbonization agenda, we hope to inform more adaptive, risk-aware policy strategies and catalyze deeper engagement across disciplines at the intersection of climate, security, and global governance.

Methods

Natural language processing to analyze decarbonization attitudes

Assessing and quantifying the decarbonization attitudes of the global shipping sector and countries relied on seaborne trade is essential for evaluating the feasibility of current climate targets, beyond mere economic and technical assessments. To achieve this, we compiled a comprehensive dataset from the top 10 global shipping industry news websites, as well as national data from Google News and government policies from 52 countries, spanning the period from 2010 to 2024. This extensive dataset comprises 518,190,352 words. The national-level data was analyzed by categorizing publishers such as corporations, industries, and government agencies, within their respective countries. Further details on data sources, collection methods, and processing steps can be found in Supplementary Methods 1 and 2.

This study explores attitudes toward shipping decarbonization on two levels. First, by assessing the industry’s perceptions and responses to decarbonization efforts, it captures the industry’s general attitude, defined as the perceived feasibility of meeting decarbonization targets, ranging from highly negative to highly positive. Second, national attitudes and their evolution are analyzed using NLP on news data, reflecting policies, strategies, and official positions adopted by governments to address climate change and promote sustainability in shipping. National-level data is analyzed by categorizing publishers from corporations, industries, and government agencies as nested entities within their respective countries, with sentiment scores ranging from extremely negative to extremely positive.

Sentiment analysis, a widely used tool in NLP, is particularly valuable in the context of increasingly accessible online text data. It enables the examination of emotional responses to specific events and the evolution of attitudes over time. To conduct the sentiment analysis, we evaluated four NLP methods for model selection, including Lexicon-based models, machine learning, BERT-based open-source models, and transfer learning-based closed-source models. Given the complexity and emotional nuances of our text data, we ultimately chose a closed-source large language model (LLM) based on transfer learning. By designing prompts, building application programming interfaces, and leveraging the Zero-Shot task processing capability of the LLM, we enabled the model to interpret and complete specified tasks, producing the required information. Due to the complexity of the language and the subtlety of sentiment expression, we applied a transfer learning-based model for sentiment classification. This method was selected for its enhanced capacity to capture domain-specific semantic variation and to identify attitudes within nuanced discourse. Benchmarking against annotated data demonstrated an average 9.897% improvement over alternative approaches. A detailed account of model selection and comparative analysis can be found in Supplementary Methods 2.

Accordingly, our modeling scheme is designed as shown in Supplementary Methods 2. First, we preprocessed all texts and transformed them into a format readable by the LLM. We designed customized prompts for both global and national text data, enabling the LLM to assess their relevance to the decarbonization topic. The LLM then evaluated the decarbonization attitude of each text, categorizing them as positive (1), neutral (0), or negative (−1), and provided supporting reasons for these assessments. Finally, we generated normalized output; a sample of the output can be found in Supplementary Methods 2.

Next, we grouped the national text data outputs by year and country. By calculating the mean sentiment scores for each group, we captured the comprehensive decarbonization attitudes of each country in a specific year. This process yielded in a 15\(\times\)52 dataset (encompassing 15 years from 2010 to 2024 and 52 countries) along with corresponding mean scores. A detailed sample of our processing results can be found in Supplementary Methods 2.

Impact evaluation using staggered difference-in-differences analysis

(1) Model specification

To evaluate the impact of geopolitical risk on national attitudes towards emission reduction, we employed a staggered difference-in-differences model to analyze changes in national attitudes towards decarbonization before and after geopolitical risks. Details on the method selection are presented in Supplementary Methods 5. The following benchmark regression model was constructed.

Where \({Attitud}{e}_{{it}}\) represents the attitude of country i towards decarbonization in year t; \({Geo\_ris}{k}_{{it}}\) represents whether country i is exposed to geopolitical risks in year t; \(Intensit{y}_{it}\) represents the geopolitical risk intensity of country i in year t; \({Contro}{l}_{{it}}\) are a set of country-level control variables to control for country characteristics. \({\mu }_{i}\) indicates individual fixed effects, \({\upsilon }_{t}\) represents time fixed effects, and \({\lambda }_{{it}}\) is a randomized perturbation term. Considering the strong correlation between decarbonization attitudes of a country in different years, we also performed country-level robust clustering standard errors. We focus on the coefficient \({\alpha }_{1}\). If \({\alpha }_{1}\) is significantly smaller than 0, it indicates that geopolitical risk substantially reduces a country’s incentives to decarbonize, potentially leading to delays in achieving decarbonization targets.

(2) Measurement of key variables and data description

The explained variable is the country’s decarbonization attitude, derived from sentiment analysis results.

The core explanatory variable in our study is geopolitical risk. When conducting the DID analysis, it is essential to divide the sample into treatment and control groups based on their exposure to policy shocks. However, geopolitical risks invariably affect all countries, making it impractical to create strictly separate treatment and control groups. To address this challenge, we constructed a policy-like experimental DID model that incorporates risk intensity. To determine whether a country is affected by geopolitical conflict (\({Geo\_ris}{k}_{{it}}\)), we calculated the mean value of the geopolitical risk index for each country during the study period. Countries with an index above the mean were assigned to the treatment group, while those below the mean were placed in the control group. Furthermore, we set the treatment intensity indicator \({Intensit}{y}_{{it}}\) as the corresponding geopolitical risk level for each year. Thus, the interaction term \({Geo\_ris}{k}_{{it}}\times {Intensit}{y}_{{it}}\) serves as the treatment effect variable.

The fundamental premise of a staggered DID model is the parallel trend assumption, which requires the treatment group (subject to geopolitical risk) and the control group (not subject to geopolitical risk) exhibit parallel trends in their changes over time prior to the onset of geopolitical risks. This study employed an event study approach for parallel trend testing, detailed in Supplementary Results 1.

We employed seven control variables to account for potential confounding factors that could influence the relationship between geopolitical risks and national attitudes toward decarbonization. Each variable was selected based on its potential impact on decarbonization efforts and its relevance to the specific context of our study. Descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in Supplementary Methods 5.

(3) Causality tests

In addition to verifying the parallel trend assumption, we conducted multiple robustness tests to ensure the validity of our results. Details of these tests can be found in Supplementary Results 2.

Test 1: placebo tests

To eliminate the possibility that the observed differences between treatment and control groups were due to time changes, we advanced the impact times of geopolitical risk by 1–8 periods and re-ran the regressions. The result showed that the coefficients of all assumed cross-terms were insignificant, indicating no systematic time trend differences between the treatment the control groups. This confirms the robustness of our benchmark regression.

Test 2: heterogeneity treatment effect test

Although our benchmark regression accounted for national-level characteristic variables, unobserved variables might still introduce estimation bias. To address this, we performed a constrained mixed placebo test using a randomized trial approach with fake treatment units and fake treatment times. The results demonstrated that all coefficients were near zero and followed a normal distribution, indicating that most regression results were not statistically significant. Furthermore, the average treatment effect was insignificant at the 1% level, confirming that our benchmark regression is robust against estimation bias due to omitted variables.

Test 3: propensity score matching (PSM) estimation

The robustness of a staggered DID also relies on the homogeneity assumption of treatment effects. If these effects vary over time or across countries, the regression results may be biased. We addressed this by testing the weights of our benchmark regression estimators. Furthermore, considering the complex entry and exit processes in our model, we adopted the counterfactual estimation method for causal inference to construct imputation estimators for regression. Both tests reported insignificant coefficients, confirming that heterogeneity bias in the treatment effects does not compromise our main conclusions.

To mitigate potential biases arising from significant differences in observable characteristic variables between the treatment and control groups before the occurrence of geopolitical risks, we employed a propensity score matching (PSM) method. This approach enabled us to identify and match control samples with observable characteristics most similar to each treatment group sample. The results showed that all coefficients remained significantly negative, demonstrating that our benchmark regression results are robust even after accounting for potential selection bias.

Test 4: variable transformations

We conducted four additional robustness tests on variable transformations. These included reconstructing the core explanatory variable, standardizing the geopolitical risk index to a range of 0 to 1, and excluding samples from periods 1 to 2 before and after the occurrence of geopolitical risks. The results showed that the core explanatory variables remained significant at the 1% level, further confirming the robustness of our benchmark results.

Bottom-up estimation of the shipping CO2 emissions

The CO2 emission inventory of shipping here is estimated using the updated STEAM. The inventory contains CO2 emissions from the main engine, auxiliary engine, and boiler of ships. We applied AIS data from January 2021 to April 2024 and updated ship technical specification data to the emission calculations. The AIS data underwent noise reduction treatment, including the removal of duplicate signal points, eliminating drifted points, etc. We corrected and interpolated missing and erroneous data in the specification information of ships using regression analysis. For more details, please refer to the Supplementary Methods 6. A global day-by-day shipping CO2 emission inventory (0.05° × 0.05°) was constructed primarily based on the following formula.

Where \(E\) represents the total emissions of the ships; \({E}_{{ME}}\), \({E}_{{AE}}\) and \({E}_{B}\) represent the emissions (g) of the main engine, the auxiliary engine, and the boiler, respectively; \({V}_{{actual}}\) is the ship’s real-time speed (knot h-1); \({V}_{{design}}\) represent the ship’s design speed (knot h-1); \(\frac{{V}_{{actual}}}{{V}_{{design}}}\) represents the load factor of the main engine of the ship according to the propeller law; \({T}_{v}\) represents the duration (h) of the ship’s voyage at the speed \({V}_{{actual}}\); \(i\) represents the four operational modes of the ship (berthing, anchoring, maneuvering, or cruising); \(E{F}_{{ME}}\), \(E{F}_{{AE}}\) and \(E{F}_{B}\) represent the emission factors (g kW-1 h-1) of the main engine, auxiliary engine, and boiler, respectively, and their reference values are given in IMO (2021).

Data availability

The data used in the analysis is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196856. The full numeric results of the modelling can be made available upon request to T.M. The automatic identification system data and ship technical specification data are restricted to the third party (http://www.shipxy.com/) and used under license for the current study. The data of boundary lines for countries were downloaded from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Code availability

Code used in this analysis is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196856.

References

Lindstad, E., Lagemann, B., Rialland, A., Gamlem, G. M. & Valland, A. Reduction of maritime GHG emissions and the potential role of E-fuels. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 101, 103075 (2021).

Müller-Casseres, E. et al. International shipping in a world below 2 °C. Nat. Climate Change 14, 600–607 (2024).

IMO. 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships (The International Maritime Organization, 2023). https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/2023-imo-strategy-on-reduction-of-ghg-emissions-from-ships.aspx.

Paltsev, S., Morris, J., Kheshgi, H. & Herzog, H. Hard-to-Abate Sectors: the role of industrial carbon capture and storage (CCS) in emission mitigation. Appl. Energy 300, 117322 (2021).

Müller-Casseres, E., Edelenbosch, O. Y., Szklo, A., Schaeffer, R. & van Vuuren, D. P. Global futures of trade impacting the challenge to decarbonize the international shipping sector. Energy 237, 121547 (2021).

Wang, X. T. et al. Trade-linked shipping CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 945–951 (2021).

Lu, B., Ming, X., Lu, H., Chen, D. & Duan, H. Challenges of decarbonizing global maritime container shipping toward net-zero emissions. npj Ocean Sustain. 2, 11 (2023).

Rony, Z. I. et al. Alternative fuels to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from marine transport and promote UN sustainable development goals. Fuel 338, 127220 (2023).

Kramel, D. et al. Advancing SSP-aligned scenarios of shipping toward 2050. Sci. Rep. 14, 8965 (2024).

Chua, J. Y., Wang, X. & Yuen, K. F. Sustainable shipping management: definitions, critical success factors, drivers and performance. Transp. Policy 141, 72–82 (2023).

Lagouvardou, S., Lagemann, B., Psaraftis, H. N., Lindstad, E. & Erikstad, S. O. Marginal abatement cost of alternative marine fuels and the role of market-based measures. Nat. Energy 8, 1209–1220 (2023).

Roelfsema, M. et al. Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 11, 2096 (2020).

Caldara, D. & Iacoviello, M. Measuring geopolitical risk[J]. Am. Econ. Rev. 112, 1194–1225 (2022).

Gupta, R., Gozgor, G., Kaya, H. & Demir, E. Effects of geopolitical risks on trade flows: evidence from the gravity model. Eurasia. Econ. Rev. 9, 515–530 (2019).

Yap, W. Y. & Yang, D. Geopolitical tension and shipping network disruption: analysis of the Red Sea crisis on container port calls. J. Transp. Geogr. 121, 104004 (2024).

Khan, K. How do supply chain and geopolitical risks threaten energy security? A time and frequency analysis. Energy 361, 134501 (2025).

Erol, S. The early impact of the Russia-Ukraine war on seaborne trade and transportation in the Black Sea. Int. J. Ship. Transp. Logist. 18, 305–323 (2024).

Notteboom, T., Haralambides, H. & Cullinane, K. The Red Sea Crisis: ramifications for vessel operations, shipping networks, and maritime supply chains. Marit. Econ. Logist. 26, 1–20 (2024).

Walker, B. et al. Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science 325, 1345–1346 (2009).

Yue, Z., Mustakim, A., Mangan, J. & Yalcin, E. Carbon footprint impacts arising from disruptions to container shipping networks. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 134, 104335 (2024).

Fiorini, M. & Middleton, A. Geopolitics of Arctic shipping — focus on the Northern Sea Route. In 2024 11th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace. 195–200 (IEEE, Lublin, Poland, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/MetroAeroSpace61015.2024.10591553.

Lyu, D. et al. Impact of Russia–Ukraine conflict on global crude oil shipping carbon emissions. J. Transp. Geogr. 128, 104311 (2025).

Xu, Y., Zhao, P., Kang, T. & Qin, K. Russia-Ukraine war has altered the pattern of carbon dioxide emissions from shipping in the black sea region. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 558 (2025).

Shapovalova, D., Galimullin, E. & Grushevenko, E. Russian Arctic offshore petroleum governance: the effects of western sanctions and outlook for northern development. Energy Policy 146, 111753 (2020).

Hoffart, F. M., D’Orazio, P., Holz, F. & Kemfert, C. Exploring the interdependence of climate, finance, energy, and geopolitics: a conceptual framework for systemic risks amidst multiple crises. Appl. Energy 361, 122885 (2024).

Wilby, C. & Huomo, L. Gas Transit Development in Europe: In an Era of Geopolitical Influence and Climate Change Pressures (European Energy and Environmental Law Review, 2021).

Zhao, P. & Zhao, T. The relationships between geopolitics and global critical minerals shipping: a literature review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 262, 107559 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. Emissions and health impacts from global shipping embodied in US–China bilateral trade. Nat. Sustain. 2, 1027–1033 (2019).

Zhang, C., Hu, Q., Su, W., Xing, C. & Liu, C. Satellite spectroscopy reveals the atmospheric consequences of the 2022 Russia-Ukraine war. Sci. Total Environ. 869, 161759 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. A novel method for ship carbon emissions prediction under the influence of emergency events. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 165, 104749 (2024).

Gokdthau, A. et al. How the energy transition will reshape geopolitics[J]. Nature 569, 29–31 (2019).

Speizer, S. et al. Integrated assessment modeling of a zero-emissions global transportation sector. Nat. Commun. 15, 4439 (2024).

Rogelj, J. et al. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2°C. Nature 534, 631–639 (2016).

Bows-Larkin, A. All adrift: aviation, shipping, and climate change policy. Clim. Policy 15, 681–702 (2015).

Martin, J., Dimanchev, E. & Neumann, A. Carbon Abatement Costs for Hydrogen Fuels in Hard-to-Abate Transport Sectors and Potential Climate Policy Mixes (MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research, 2022).

Howlett, M. Procedural policy tools and the temporal dimensions of policy design. Resilience, robustness and the sequencing of policy mixes. Int. Rev. Public Policy 1, 27–45 (2019).

McEntire, D. A. Emergency management theory: issues, barriers, and recommendations for improvement. J. Emerg. Manag. 3, 44–54 (2005).

Bavel, J. J. V. et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 460–471 (2020).

Jackson, J. C. & Medvedev, D. Worldwide divergence of values. Nat. Commun. 15, 2650 (2024).

Simionescu, M. & Bilan, Y. Environmental regulation, innovation and sustainable development: the moderating role of governance quality in the EU. J. Clean. Prod. 293, 126133 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Ge, R., Zhou, J. & Notteboom, T. Decarbonization pathways for bulk vessels: integrating power systems, fuels, and control measures. Ocean Eng. 300, 117488 (2024).

Grzelakowski, A. S., Herdzik, J. & Skiba, S. Maritime shipping decarbonization: roadmap to meet zero-emission target in shipping as a link in the global supply chains. Energies 15, 6150 (2022).

Xu, Y., Yang, S. & Zhang, Y. Carbon neutrality: targeted strategies and regional gaps. Nat. Commun. 13, 4576 (2022).

Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econ. 225, 254–277 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Global evidence of expressed sentiment alterations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 349–358 (2022).

Traut, M. et al. CO2 abatement goals for international shipping. Clim. Policy 18, 1066–1075 (2018).

De Chaisemartin, C. & d’Haultfoeuille, X. Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 110, 2964–2996 (2020).

Liu, L., Wang, Y. & Xu, Y. A practical guide to counterfactual estimators for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 68, 160–176 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42525101 and 42130402) and Shenzhen Technology Development Program (JCYJ20220818100810024 and KQTD20221101093604016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z. designed the research, provided funding and supervision. P.Z. and T.M. contributed analytic tools. T.M., T.Z., R.X., and T.K. analyzed the data. P.Z. and T.M. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Peter J. Stavroulakis, Enna Hirata and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Miranda Böttcher and Yann Benetreau. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, P., Ma, T., Zhao, T. et al. Geopolitical risks impede global shipping decarbonization progress. Commun Earth Environ 6, 835 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02852-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02852-7