Abstract

Hydroclimatic variations are among the factors shaping the rise and fall of the Indus Valley Civilization. Yet, constraining the role of water availability across this vast region has remained challenging owing to the scarcity of site-specific paleoclimate records. By integrating high-resolution paleoclimate archives with palaeohydrological reconstructions from transient climate simulations, we identify the likelihood of severe and persistent river droughts, lasting from decades to centuries, that affected the Indus basin between ~4400 and 3400 years before present. Basin-scale streamflow anomalies further indicate that protracted river drought coincided with regional rainfall deficits, together reducing freshwater availability. We contend that reduced water availability, accompanied by substantially drier conditions, may have led to population dispersal from major Harappan centers, while acknowledging that societal transformation was shaped by a complex interplay of climatic, social, and economic pressures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Indus River was central1,2 to the development of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), providing a stable water source for agriculture1,3,4,5,6, trade, and communication3,7. The civilization flourished around the Indus River and its tributaries around ~5000 years before present (BP; relative to 1950 CE) and evolved over time8. During the Mature Harappan stage (4500-3900 years BP), the IVC featured well-planned cities, advanced water management systems, and a sophisticated writing system1,8. After ~3900 years BP, however, the Harappan civilization began to decline and eventually collapsed3,8,9,10,11. The causes of this decline remain debated3,12. Proposed factors include climate change, seawater retreat, droughts, floods, and shifting river dynamics, interacting with social and political changes3,6,10,13,14,15,16,17,18. Understanding ancient hydroclimatic events and their societal impacts provides critical insight into the vulnerability of complex societies to environmental stress10,19,20,21.

Hydroclimatic variability across the Harappan domains was influenced by both the Indian summer monsoon (ISM) and Indian winter monsoon (IWM). These systems are thought to have been coupled during the early-to-mid Holocene, but diverged during the mid-to-late Holocene, likely due to low-latitude insolation changes22. Instrumental and paleoclimate evidence demonstrates that diverse regional forcings shaped hydroclimatic variability during different periods12,20,23,24. Whereas instrumental records help to investigate the hydroclimatic variations of the last 100–150 years, reliable, long-term records are rare beyond 185023,25. Accordingly, paleoclimate proxies may be used to investigate past perturbations to the hydrological cycle.

Notable efforts have been made to capture the hydroclimatic variability and past drought events associated with the ISM using lacustrine20,26,27,28,29,30, speleothem9,31,32,33, paleo-botanical4,34, marine11,35, and other geological archives21,36,37. For instance, Dutt et al.3,38 used 4500-year-old lacustrine sediments from Tso Moriri Lake, northwest Himalaya, and found regional variations in the ISM during the initiation of the Meghalayan period9,14,31. They3 also suggested a prolonged dry phase between 4350- and 3450-years BP, which likely contributed to the water scarcity in the IVC region. Kathayat et al.31,39 used high-resolution speleothem proxies from the Sahiya and Mawmluh cave to assess the putative 4200-year global aridification event, which bounds the prolonged drought over the IVC region between 4200- to 3900-years BP. Giosan et al.11 used fluvial evidence to determine past environmental conditions and their impacts on habitats in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, identifying centuries-long weak monsoon events during the Late Harappan period. Similarly, Staubwasser et al.13 used oxygen isotope data from the Indus Delta to invoke drought initiation, which bounds the putative aridification event within 4400- and 3400-years BP. Dixit20 attempted to reconstruct the variability of the ISM using lacustrine records of Rajasthan. Lakes on the margin of the Thar Desert and the eastern region of Rajasthan showed distinct patterns of evolution over time, highlighting the influence of regional climate trends20,26,29,40,41,42.

Paleoclimate proxies provide indirect and geographically restricted estimates of past climate change and variability. Accordingly, output from climate model simulations in tandem with proxies can help contextualize spatial variability and help explain mechanisms of hydrological shifts25,43,44. Recent paleoclimate modeling suggests substantial spatiotemporal variability of ISM intensity from the mid-Holocene to the present25,45,46,47. Hydroclimatic changes during the mid–late Holocene, particularly the abrupt ~4200 BP event, have drawn extensive attention and debate3,9,13,31,37,40,48,49,50,51. Yet, reconstructions remain hampered by limitations, including site-specific biases, low resolution, chronological uncertainties, and non-unique interpretations23,52,53. Catchment-scale processes further complicate relationships between proxy signals and hydrological variables such as precipitation and discharge54, making quantitative assessments of climate–society linkages difficult.

To address these challenges, we combine climate model simulations with paleoclimate proxy records to evaluate the paleohydrological variability of the IVC region during the late Holocene (5000–3000 years BP). We use meteorological forcings from three transient climate simulations (TraCE-21ka; 22000 years BP to present, MPI; 7950 years BP to 100 years BP, and TR6AV; 6000 years BP to present; See Table S1) as input parameters to the Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) hydrological model. This approach enables simulations of river discharge variability near major Harappan settlements. By integrating past climate simulations with hydrological modeling, we aim to contextualize existing proxy reconstructions and assess how hydroclimatic trends helped shape historical trajectories of human settlements in the IVC55.

Results

Identification of past drought events

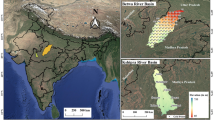

We focused on a designated IVC region (Fig. 1) to examine past hydroclimatic variations using transient climate simulations (Table S1) and paleoclimate records (Table S2). The Harappan period (5000–3000 years BP) was divided into three phases10,31: (1) Pre-Harappan (5000–4500 years BP; PreH), (2) Mature Harappan (4500–3900 years BP; MatH), and (3) Late Harappan (3900–3000 years BP; LatH) based on archaeological evidence of settlement evolution and socio-environmental changes2,11,39,56. These divisions enable evaluation of hydroclimatic trends alongside cultural transitions, with particular focus on settlement patterns and potential climate-driven changes at the close of each phase.

a Inset tile showing location of the study area (shaded in blue) with the major river basins of Indian subcontinent. b Study Area indicating discharge stations considered in this study near Major Harappan sites (Yellow circles) with major river basins of Indian subcontinent. Red triangles indicate location of lake proxies, while yellow start denotes the location of Sahiya Cave. Shaded background shows elevation data (in m) from USGS GTOPO30. c Simulated ensemble rainfall with associated uncertainty, calculated as ± 1 standard deviation derived from three transient climate simulations (TraCE-21ka, MPI, and TR6AV) spanning from 6000 years BP to present (1850 CE). d Similar to (c) but for Standardized precipitation Index (SPI) computed with respect to the Pre Harappan period. e Simulated ensemble rainfall over the grid encompassing Sahiya cave, alongside its validation (R2 = 0.46) with speleothem data. Three bands from 5000 to 3000 years BP show the distinct periods of the Indus Valley Civilization: Pre-Harappan (PreH), Mature Harappan (MatH), and Late Harappan (LatH).

The ensemble mean of all three transient climate simulations (TraCE-21ka; hereafter TraCE, MPI, and TR6AV) indicates a persistent drying trend in the 100-year moving rainfall averages over the past 6000 years (Fig. 1c), with a reduction of ~120 mm and an inter-model (1σ) uncertainty of 20 to 40 mm. All three models show this drying trend (Fig. S1). TraCE and TR6AV simulate gradual declines in rainfall, with TraCE producing consistently higher rainfall than TR6AV. Conversely, MPI simulates a sharper decline and greater variability across the three models (Fig. S1). The abrupt reduction in MPI is linked to anomalous warming in the West African and Indian monsoon zones57, which triggered a positive feedback reducing rainfall through diminished evaporative cooling and cloud cover57. The 12-month Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) also shows a long-term decline, with a marked reduction after the PreH interval (Fig. 1d).

To test model fidelity, we compared ensemble-mean rainfall with speleothem δ¹⁸O data from Sahiya cave, where more negative values are interpreted as higher rainfall or more intense convection39. Ensemble-mean rainfall anomalies from 4500 to 2500 BP indicate a moderate correlation with the δ¹⁸O record (r = 0.46; Fig. 1e), supporting the modeled drying trend. Comparisons with other cave archives (e.g., Bitto, r = 0.50; Wahshikhar, r = 0.39) also show broad consistency (Fig. S2). While discrepancies exist across sites, these results suggest the transient simulations capture key large-scale processes. We also note the existence of discrepancies between simulations and existing records as well (Fig. S2), and stress that our intent to utilize transient simulations is to explore plausible large-scale processes and feedbacks44,57,58. Grid-to-grid comparisons with proxy records may not be appropriate due to the limited resolution of simulations and inadequate representation of local topography, land-atmosphere interactions, and isotope meteorology59. Nevertheless, broad agreement with speleothem evidence (Figs. 1e and S2) provides confidence in using the simulations to explore drought extent and severity.

The transient climate simulations also reveal a ~0.5 °C rise in IVC’s annual mean temperature from the PreH to the LatH, with a significant warming trend of 0.024 °C per century (p < 0.01; Fig. S3a). Furthermore, we found warming trends with more than 95% confidence level within both latter periods as well—with trends of 0.02 °C and 0.016 °C per century for the MatH and LatH periods, respectively. Spatially, significant (99% confidence level) warming over the central IVC region and particularly over the foothill of the Himalayas was observed during the transition from the PreH to LatH period (Figs. S3b and S3c). In addition, century-scale rainfall averages (a 100-year moving average of rainfall) decreased significantly (~51 mm reduction in this metric from the PreH to LatH; Fig. 2b), which is notable considering the long period (100 years) for which the average rainfall was estimated. Furthermore, the simulations indicate declines of ~13–15% in annual, summer, and winter rainfall with a significant decreasing trend of ~0.7 % per century at 99% confidence level (Fig. S3d, S3g, and S3j, respectively). Annual rainfall showed a noteworthy reduction of over 20% in the central region of the IVC and a decline ranging from 15 to 20% in peripheral areas during the LatH period (Fig. S3f). In contrast, a more modest reduction of approximately 10% was observed across the entire IVC during the MatH period (Fig. S3e). All transient simulations indicated moderate annual rainfall amounts during the PreH compared to deteriorating conditions across the PreH to LatH transition (Fig. S1 and S4). We further note that the TraCE simulation showed a major reduction in annual rainfall over western IVC areas compared to the central region, whereas MPI showed a major reduction over the central IVC area in contrast (Fig. S4). Spatial patterns similar to those observed in annual rainfall changes were also evident in summer rainfall anomalies, with a strong reduction of over 20% during the LatH (Fig. S3i). We found minimal changes in winter rainfall across the IVC during the MatH period (Fig. S3k), which agrees with paleoclimate records showing steady winter rainfall during the MatH period56. Conversely, a reduction of 10–15% in winter rainfall was found during the Late Holocene (coinciding with the LatH period) (Fig. S3l). The warming trend propagated from east to west, whereas the rainfall deficit propagated from west to east from the PreH to the LatH period, in agreement with earlier hypotheses20.

a Annual air temperature over IVC derived from the TraCE-21ka simulations; b Simulated ensemble rainfall from three transient climate simulations (TraCE-21ka, MPI, and TR6AV) with associated uncertainty, calculated as ± 1 standard deviation; c Similar to b but for Standardized precipitation Index (SPI) computed with respect to the Pre Harappan period; d Detrended SPI and identification of major flood and drought events using the threshold of 0.5 and −0.5, respectively; e Variation in detrended DJF mean SST anomalies over the Niño 3.4 and AMO region. All the variables in (a–e) are 100 year moving mean estimates. Light orange stripes show major drought events. f Spatial variability in SPI derived from the precipitation datasets of all transient climate simulations and presented for the identified major drought events. Black dots indicate Harappan sites during the period of drought, and blue polygon shows extent of Harappan Civilization. g Event-wise spatial variability in DJF mean SST anomalies with highlighted Niño 3.4 and AMO regions.

We identify four severe droughts (>85 years each) between MatH and LatH, based on the detrended 100-year moving mean SPI (Fig. 2d and Table S3). These major droughts occurred at 4445–4358 (D1), 4122–4021 (D2), 3826–3663 (D3), and 3531–3418 (D4) years BP (Fig. 2d). Three of these droughts affected more than 85% of the IVC region (range 65–91%). Peak intensities reached SPI values of –1.5, –2.1, –1.65, and –1.72, respectively. Using a drought severity score60, which incorporates the intensity, duration, and areal extent, D3, peaking at 3757 years BP, ranks as the most severe— lasting ~164 years, reducing annual rainfall by ~13%, and affecting more than 91% of the region (Figs. 2f and 3g). Unlike the other events, D3 featured consistent declines in summer and winter rainfall, disproportionately impacting the central IVC region, whereas Saurashtra remained relatively unaffected.

The first drought event, D1 (Fig. 2f), occurred at the beginning of the MatH period (~4.4–4.3 ka), with 65% of the IVC region under drought with ~5% reduction in annual rainfall compared to PreH (Fig. 3a). This event lasted about 88 years and was two to three times less severe compared to the later droughts. D2 coincided with the global 4200-year event, with substantially lower severity than D3. The central Indus Basin experienced more substantial impacts than the Lower and Upper Indus Basins during D2, whereas the Ganweriwala and Kalibangan regions were less severely affected (Figs. 2f and 3f). The D4 event (Fig. 2f) began ~3531 years BP, lasting ~114 years with moderate intensity and ~13% reduction in annual rainfall. MPI and TraCE captured all the major drought events, whereas TR6AV showed a lagged response (Fig. S1), highlighting the role of internal variability47. MPI consistently simulated the most severe droughts, while the models differ in regional rainfall declines (Fig. S5). All models showed drier conditions during the D3 and D4 events, with model-based differences in spatial patterns. Whereas TraCE indicates more of a decline in the central region during these events, MPI and TR6AV show a stronger decline in the north-east part of the IVC region (Fig. S5).

a–d Annual Temperature anomalies (°C) and ensemble-mean rainfall anomalies of e–h annual rainfall i–l summer rainfall (JJASON) and m–p winter (DJFMAM) rainfall derived from three transient climate simulations (TraCE-21ka, MPI, and TR6AV). Anomalies (%) are relative to the long-term mean of 5000–4500 years BP (PreH). Black dots show the location of Harappan sites during the given period, whereas the red line bounds the IVC region.

We observed a gradual reduction in annual and summer rainfall from event D1 to D4 (Fig. 3), whereas winter rainfall decreases till the D3 event only and then revives during D4 (Fig. 3). Further, we also observed the increase in annual mean temperature from D1 to D4 (Fig. 3a–d), which might have increased the atmospheric water demand and thus evapotranspiration, which makes these droughts more severe60. Similarly identified droughts are also evident in speleothem records from Sahiya cave, whereas they are either absent or show a large, lagged response in the Mawmluh cave record. This may result from the hydroclimate signal at Mawmluh Cave having lowered sensitivity to rainfall in the IVC region24,52. The drying over the IVC area from 4000 to 3000 years BP was more dominant61, and mainly expressed in the central IVC region for the last three droughts (Fig. S5), which may additionally explain the shift in settlements toward the Ganga plains and Saurashtra region during this period12,39,56.

Finally, we examined simulated variability in sea surface temperatures (SST) in the Pacific and North Atlantic—regions with well-established teleconnections to ISM variability62,63. Typically, El Niño-like conditions in the tropical Pacific, with a warmer central and eastern equatorial Pacific, and relatively cooler SSTs in the northern Atlantic Ocean (Fig. S6), have been shown to induce drought conditions during the ISM season in observations62 and last millennium simulations64. Detrended SST anomalies (Fig. 2) in the Niño3.4 box—a region used to monitor ENSO activity—were higher during D1 than the previous ~400 years, signifying strong El Niño conditions across this drought. The drought at 4.1–4.0 ka BP (D2) occurred under high SSTs in the tropical Pacific and cooler SSTs in the northern Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 2). Accordingly, we suggest that D1 and D2 were associated with warmer central and eastern equatorial Pacific SSTs and cooler North Atlantic SSTs—an inference consistent with reconstructions from reduced space and Bayesian methods65,66. In contrast, drought events D3 and D4 occurred with the warming SST in the eastern Pacific relative to background conditions and neutral SST anomalies in the Northern Atlantic.

Paleohydrological reconstruction

We found that the higher settlement density in the western region of the IVC and upper Ganga plains during the PreH period (Fig. S4) coincided with enhanced water availability indicated by the simulated riverflow (Fig. S7). Most sites were situated away from the river complex during the PreH period, suggesting higher rainfall conditions and access to freshwater across the IVC region10,37, with reduced dependence on river resources (Fig. S4). Wetter conditions over northwest India during PreH and subsequent drying during LatH were also observed in the reconstructions of Gill et al.67. In this work, they67 reconstructed changes in rainfall over India with respect to the present day and found a 40–60% increase in rainfall relative to the present, which sustained lakes, including Lake Sambhar68. Subsequently, we simulated river discharge using the VIC hydrological model at sites proximal to major Harappan cities (referred to as stations hereafter), with nine stations situated within the Indus basin, three stations within the Ganga basin, and five stations within the Sabarmati basin (Fig. 1). We estimated the discharge anomalies with respect to the PreH period (Fig. S7). During the MatH period, compared to the PreH period, urban settlements shifted towards the Indus River from various parts of the IVC region. Relatively low discharge anomalies were found in stations STI01, STI03, STI05, and STI09 compared to the other stations in the upper Indus, Ganga basin, and Saurashtra region during D1 (Fig. 4a1, 4a2). Moreover, towards the end of MatH period, the central IVC region was affected by the drought event D2 (Fig. 2f), exacerbating fluvial drying at STI01, STI03, STI05, and STI09. However, stations in Saurashtra (STS01-STS05) indicated strengthening riverflow conditions, whereas those in the upper Indus (STI06-STI08) and Ganga basins (STG01-STG03) remained relatively stable, thus attracting urban settlements at the end of the MatH period (Fig. 4b1, 4b2). Subsequently, riverflow deteriorated during D3 and D4, with some of the sites experiencing discharge anomalies of more than 12%. According to our hydrological simulations, lower and upper Indus regions showed a maximum reduction (more than 9%) in riverflow during the D4 (Fig. 4d1). Sites such as Kot Diji (STI02) and Ganweriwala (STI04) experienced a ~12% reduction in riverflow, suggesting water scarcity in the Indus River during the LatH period. Additionally, we observed a downstream decrease in discharge anomalies, signifying the dominance of westerly-driven winter rainfall and snowmelt in the upper Indus as potential drivers. Conversely, sites in Saurashtra exhibited a smaller reduction in discharge compared to other stations, indicating favorable conditions for settlements in that region during MatH to LatH transition (Fig. S7).

Spatial variation in discharge anomalies (with respect to the long-term mean of the Pre-Harappan period) across the IVC region for (a1) D1, (b1) D2, (c1) D3, and (d1) D4 drought events. The panel on the right (a2, b2, c2, and d2) displays station-wise discharge anomalies with associated uncertainty during the respective drought event. Red, orange, and yellow bars show stations in Indus, Ganga, and Sabarmati, respectively.

We compared our analysis with reconstructed lake levels from IVC-proximal lacustrine records. Reconstructed lake levels of Nal Sarovar Lake show declines from the PreH to MatH, specifically during D1 (Fig. S8a). In contrast, other lakes exhibit increasing or minor fluctuations in water levels during D1 (Fig. S8), which may be explained by regional differences in precipitation patterns20, evaporation/precipitation (E/P) ratios, and variable runoff resulting from a smaller catchment area30,69. Nevertheless, we find a notable disparity between paleolake levels and drought events during the MatH, specifically during the 4200-year BP D2 event. All other lake records, except Pariyaj (Fig. S8), experienced an initial drying phase corresponding to D3 and D4 events (Fig. S8). The Sahiya cave record showed drying rainfall trends across D1 to D3 (Fig. S8), but diverges from the simulations during D4 (Fig. S8).

We identified four distinct spatial clusters based on the simulated riverflow patterns during major drought events (Figs. 4 and S7). These include the Upper Indus (Harappa-STI05), Middle Indus (Kot Diji-STI02, Ganweriwala-STI04, Kalibangan-STI06 and Banawali-STI07), Lower Indus (Mohenjo-Daro-STI01 and Chanhudaro-STI03), and Saurashtra (Dholavira-STS01, Surkotada-STS02 and Lothal-STS03) regions. Clustering based on discharge anomalies coincides with the region of homogeneous agricultural patterns identified by Petrie and Bates4, demonstrating the potential of hydrological simulations to provide perspectives on early farming practices using simulated paleodischarge data. Petrie and Bates4 showed the prevalence of multi-cropping for summer crops and mono-cropping for winter cereals over the upper Indus region, which may be linked to the large and notable shifting phase of discharge in this region during the PreH. Archaeobotanical records from the foothill of the Himalayas showed positive rainfall anomalies during both summer and winter, allowing for the continuous availability of soil moisture in this region during the mature phase70. Such precipitation anomalies may have helped spur innovation in crop strategies and selections. For example, Rabi and Kharif crops were grown, and wheat and barley were shifted to millet during the MatH4,5,34.

Discussion

The onset, evolution, and decline of the Harappan civilization, which developed along alluvial plains supported by natural drainage and floodwater irrigation, has been a major focus of research24. Based on our climate simulations and paleoclimate evidence, we suggest that drought initiation in the IVC region began around 4440 years BP, coinciding with shifts in settlement patterns and cultural reorganization. Transient climate simulations and hydrological modeling reveal a sequence of severe droughts exceeding 85 years in duration during this interval, with progressively intensifying conditions (Fig. 2f). Giesche et al.33 proposed recurring summer and winter droughts between 4200–3970 BP from Dharamjali Cave speleothem records, including multi-decadal events around 4190, 4110, and 4020 BP separated by ~20–30 year recovery phases. These align closely with our second drought event. Similarly, our findings are consistent with the “double drought” hypothesis of Scroxton et al.51, which suggests that aridification began around 4260 years BP and persisted for 300 years. The extended summer monsoon drought that we identified during 3531–3418 BP coincides with widespread deurbanization and cultural abandonment of major Harappan centers12,39,56.

The study of Giosan et al.56 shows coherence between our drought events and their reconstruction of weakened summer monsoon strength and enhanced winter monsoon rainfall from ~4500 to 3000 BP, followed by a winter monsoon decline after 3300 BP. This reconstruction56 of winter monsoon variability, based on marine sediment core and ancient DNA analysis, does not directly resolve individual drought events of the summer monsoon at high temporal resolution. Nevertheless, we find coherence between the simulated drought events and trends uncovered in their work (Fig. S9). In particular, the first two droughts we identify were partially relieved by stronger winter monsoon rainfall, especially across the Ghaggar–Hakra interfluve. However, once winter monsoon precipitation also declined after ~3300 BP, Harappan settlements fragmented into smaller units (Fig. S9).

To investigate drivers of the multidecadal droughts, we analyzed SST variability in all three transient simulations. Prior work has implicated Northern Hemisphere (NH) insolation, North Atlantic SSTs44,56, ENSO variability in the Pacific71, and Indian Ocean conditions56 as potential contributors. The physical mechanisms underlying these teleconnections involve large-scale atmospheric circulation shifts44,56,71. Mechanistically, warm tropical Pacific SSTs during El Niño events enhance upper-tropospheric divergence and shift the ascending branch of the Walker Circulation eastward72,73 (Fig. S6), inducing subsidence over the western Pacific and Indian Ocean. This suppresses convection and rainfall over South Asia by weakening the monsoon Hadley cell72. The warmer SSTs over the tropical Pacific during El Niño events enhance upper-tropospheric divergence and shift the ascending branch of the Walker Circulation eastward72. Simultaneously, El Niño–driven warming of the Indian Ocean74,75 (Fig. 2) reduces the land–sea thermal gradient and weakens the cross-equatorial pressure gradient, limiting moisture transport into the subcontinent76,77,78. The weakened thermal gradient diminishes the low-level wind inflow from the ocean to the continent, reducing the moisture transport and ultimately leading to a decline in monsoon rainfall78. Conversely, cooler North Atlantic SSTs (negative AMO phase; Fig. S6) reduce the inter-hemispheric temperature gradient44, which is associated with weakened subtropical high-pressure systems and results in a southward displacement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). This further reduces moisture influx over South Asia79. Moreover, negative AMO-like phases may have weakened the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation state, which could have shifted teleconnections and weakened the Indian monsoon80. Additionally, TraCE-derived Sea level pressure and SST patterns suggest positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) like conditions during 4200 years BP, which led to cooling over the NH73. Overall, Synchronous El Niño-driven warming in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, along with the negative AMO-driven cooling in the North Atlantic, weakens the Walker circulation, reduces the land–sea thermal gradient, and displaces the ITCZ southward, respectively, collectively suppressing ISM moisture transport and rainfall over the IVC region.

Single-forcing experiments of TraCE simulations44 performed using meltwater forcing, ice-sheet dynamics, and greenhouse gases neither show the signature of a global 4200 years BP event nor the reduction in rainfall during the LatH, which points towards internal variability or additional forcings as a major contributor to the drying81. Giosan et al.56 reported that changes in tropical albedo and regional dust emissions during aridification events may have caused land-use and land-cover changes, which might have caused a southward shift of the ITCZ. Furthermore, transient climate simulations have their own limitations due to initial conditions, parameterization, forcing assumptions, and local-scale feedback processes58. While they are useful for analyzing broad-scale and long-term trends45,47, their limitations in resolution and forcing representation pose challenges for assessing decadal and sub-centennial variability and warrant extensive validation with geological proxies. Thus, high-resolution paleoclimate proxies are required to further examine the role of regional forcings and internal climate variability on ITCZ shifts in the Indian Ocean, and its subsequent impact on the Indian monsoons. Additionally, increasing model resolution can help to better capture regional processes. For instance, the improved horizontal resolution in TR6AV over TR5AS allows more realistic monsoon penetration along the Himalayan foothills47.

Our results suggest that climate shifts coincided with the eastward and southward migration of Harappan populations into the Ganga Plains and Saurashtra (Fig. 1b). Stronger discharge anomalies near Kot Diji, Ganweriwala, and Dholavira likely played a major role, while declining Indus River discharge may have encouraged relocation. This supports a “push–pull” migration framework as outlined by Giosan et al.56. Enhanced orographic precipitation with dense river networks in the foothills of the Himalayas likely facilitated a more persistent moisture regime throughout the year, providing a more stable agricultural system in the Ganga Plains11. Adaptation strategies, including a transition from wheat and barley to drought-tolerant millets4,5,34, likely sustained agricultural production in Saurashtra. Maritime trade with Mesopotamia82 likely provided another buffer, allowing coastal and Indus societies to supplement local shortfalls through imported staples. The decline of the IVC was therefore not the product of a single abrupt collapse, but rather a protracted transformation shaped by both climatic and non-climatic processes2,5,6,14,16,70,82. Whereas prolonged aridity contributed, additional factors such as the selection of drought-tolerant plants4,5,34, long-distance agricultural trade82, and shifts in regional artifacts2 suggest that the decline was not a sudden collapse but a complex process of fragmentation and cultural transformation, indicating a societal adaptation rather than a complete disappearance83. Discrepancies between model simulations and proxy reconstructions highlight uncertainties in both model–data comparison and transient climate modeling84,85. Nevertheless, our findings of simulated and reconstructed river drought over the IVC reign enhance our understanding of the history of the Harappan civilization and its intricate relationship with climate change.

Methods

The study region encompasses parts of India and Pakistan and is primarily characterized by summer monsoonal rainfall (~400 mm/year), which accounts for 75–80% of the annual rainfall20,36. Importantly, the upper Indus area also receives winter rainfall from western disturbances38. We selected seven terrestrial proxy records covering Harappan period (Table S2) from the surrounding area of IVC to investigate regional climate variability. Amongst these, five are records of lacustrine deposits (Fig. 1b) from Gujarat28,30 and Rajasthan26,29,86, and two records derived from speleothems of Sahiya39 and Mawmluh caves9. The selected lakes are strongly influenced by the ISM; in contrast, the speleothem records offer high-resolution, continuous records of past climate variability, providing valuable insights into regional climate, but are affected by notable rainfall variations outside ISM variability. Rainfall over Sahiya cave39, which is in Uttarakhand, is influenced by the southwestern summer monsoon as well as the winter monsoon, driven by westerlies. Thus, we hypothesize that Sahiya Cave likely provides insights into winter precipitation over the region. Conversely, Mawmluh cave9 in Meghalaya experiences rainfall variability associated with the northeast monsoon winds (during October-December) as well as the ISM. Further, we have also used other three speleothem data from Bitto cave87, Wah Shikar cave63, and Jhumar-Dandak cave63 to validate rainfall trend obtained from the transient climate simulations.

We considered three transient climate simulations (Table S1) obtained using General Circulation Models (GCMs). Two simulations (MPI and TR6AV) were conducted using mid-Holocene boundary conditions as the initial conditions for the transient experiment45,57,58, while the third one (TraCE) was conducted using the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) boundary conditions81. We selected TraCE, MPI, and TR6AV over other transient simulations such as EC-Earth388,89 and iTraCE90, as they offer continuous transient output of precipitation and sea surface temperatures for the entire Harappan period (5000-3000 years BP), and their data are publicly available. Additionally, we obtained the instrumental long-term (1813–2006) monthly rainfall datasets91 from the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) (https://www.tropmet.res.in/, Accessed on January 2022). We used these datasets to evaluate the performance of the three transient climate simulations over different seasons (Fig. S10a) and annual rainfall time series (Fig. S10b). TraCE transient climate simulations performed relatively well by showing less percentage bias (~−19%) for annual average rainfall compared to other simulations. Moreover, all the models underestimated annual average rainfall, with underestimation of rainfall during March-May (MAM) and June-September (JJAS), and overestimation in January-February and October-December (OND). We used rainfall from all the transient simulations and then validated the ensemble rainfall with speleothem data of five different caves (Table S2). Geological validation shows ability of transient climate simulations in capturing rainfall trend and major rainfall patterns observed in the past 5000 years (Fig. S2). While, minimum and maximum temperature were taken from the TraCE-21ka as these variables were not available publicly in other climate simulation. However, we noted that the major droughts in the monsoonal climate are largely driven by rainfall variability instead of temperature92. He81 generated the TraCE-21ka simulation using the CCSM3 climate model, which is available from 22000 years BP to present. We obtained TraCE-21ka data from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) data portal (https://ncar.ucar.edu/, Accessed on January 2022). CCSM3 is a coupled model of the land, atmosphere, ocean, and sea-ice components without flux adjustment81. The land module of CCSM3 contains a dynamic vegetation layer that represents mixed land units for each grid cell81. Additionally, the CCSM3 model includes a layer to create dynamic sea-ice topography and integrates the extent and thickness of ice sheets every 500 years using paleoclimate data to constrain the model evolution81. MPI simulations were generated using MPI-ESM1.2 with dynamic vegetation component and no variation in ice sheets topography57. Similarly, TR6AV simulations were generated using IPSLCM5A-MR with key attributes like predictive snow cover, soil hydrology with 11 layers, and dynamic vegetation component in its land surface component45. Furthermore, we used these transient climate simulations as the input forcing for running Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) model.

The Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) model

The VIC model is a semi-distributed model that solves water and energy balance at each grid93. We used 0.25° grid resolution with a daily temporal resolution to conduct hydrological simulations using the VIC model. As the observed discharge data is unavailable for the paleoclimate period for the model calibration, we used soil, vegetation, and other calibrated model parameters from Shah to Mishra94 and Kushwaha et al.95. They94,95 calibrated soil parameters (depths of second and third soil layers, binf, Ws, Ds, and Dsmax) of the VIC model using observed streamflow data from 18 stations in major river basins of India for the current climate. We specifically focused on the Indus, Ganga, Mahi, and Narmada River basins, as they fall within the IVC region and have good availability of observed streamflow data. The VIC model was calibrated against the observed monthly streamflow at Baramula station for Indus, Farakka station for Ganga, Chakaliya station for Mahi, and Sandia station for Narmada. The VIC model was calibrated and validated at a monthly scale in each basin with different time periods due to the limited availability of the discharge data. Moreover, details about the station location, calibration, and evaluation period can be found in Supplementary Table S4. All basins showed a monthly NSE of more than 0.6 during the calibration and more than 0.7 during the evaluation period (Fig. S11). Subsequently, we provided daily 0.25° gridded rainfall with maximum and minimum temperatures bootstrapped from monthly transient climate simulations as input to the VIC model to simulate paleohydrology. While applying modern calibrated parameters to simulate past hydrological conditions, we considered static vegetation cover, soil properties, and land use with no change in the basin morphology, which might introduce uncertainties in the analysis, as paleoclimate conditions likely differed from the present. Moreover, we considered the first 200 years for the model spin-up to reduce the influence of the model’s initial conditions and to stabilize state variables. We then used the VIC model-generated runoff to reconstruct past hydrology. We employed a standalone routing model developed by Lohmann et al.96 for routing runoff from the VIC model by assuming the horizontal routing processes within the rivers as linear and time invariant.

Experimental design

We obtained monthly rainfall datasets of the last 6000 years from the all-transient climate simulations, while temperature dataset from TraCE-21 ka simulation (Table S1). Next, we used bilinear interpolation to convert the spatial resolution of different transient climate simulations to 0.25° spatial resolution. Subsequently, we generated annual average rainfall time series for India, focusing on the period that coincided with the IITM observed rainfall datasets91. We examined the spatial variability of rainfall (%) and temperature (°C) anomalies with respect to the Pre-Harappan period over three time spans (Pre-Harappan-PreH, Mature Harappan-MatH, and Late Harappan-LatH). We estimated percentage anomalies for annual and seasonal rainfall over the IVC area. Furthermore, we converted monthly climatological data of 0.25° grid resolution into daily time steps using bootstrapping algorithm97. Initially, we collected daily climate data from the MPI-ESM and subsequently resampled it for each month. To ensure the fidelity of the generated data, we performed random sampling from MPI-ESM data based on the number of days in each month. We then applied a bias correction method to maintain the monthly statistics as per the transient climate simulation. Specifically, we adjusted the daily rainfall data to preserve the sum and the daily temperature data to preserve the mean, matching the respective monthly values for rainfall and temperature. By employing bootstrapping algorithm, we successfully generated synthetic daily data that closely resemble the patterns and variability observed in the monthly data of climate simulations.

The 4200-year event is believed to have marked the onset of the collapse of the IVC40. To substantiate this claim, we identified major drought events using a standardized precipitation index (SPI)98. We selected SPI over other drought indices, such as the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), due to the constrained availability of climate data. We generated the 12-month detrended SPI time series from the 100-year moving rainfall data to avoid interdecadal variability, a continuously drying trend, and other high-frequency variations after following44. McKee et al.98 used an SPI threshold of −1 to identify drought events. In contrast, we used a threshold of −0.5 SPI to identify drought periods. The reduction in drought threshold accounts for the reduced overall SPI variabilities and intensities resulting from the application of a 100-year moving mean filter to the rainfall datasets (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, recent studies99,100,101 over the ISM region also used a threshold of −0.5 for the creation of a drought atlas and operational drought monitoring. We estimated drought characteristics (Table S3) such as duration (the period during which the SPI value remained below -0.5), mean intensity (the mean SPI value within the drought period), percentage area under drought (the area with SPI value below −0.5), and severity (a combined measure of duration, intensity, and percentage area under drought), for each major drought event. Drought characteristics allowed us to identify the periods during which potential meteorological droughts occurred due to prolonged rainfall deficiency.

We conducted hydrological simulations using the VIC model, aiming to examine the impacts of identified droughts on river discharge. VIC model enabled us to trace the progression of drought conditions from their meteorological origins to their impact on the hydrological system. For that, we calculated discharge anomalies at 17 major Harappan stations (Fig. 1) for the major drought events, including nine stations from the Indus basin (three from Upper Indus, three from Middle Indus, and three from Lower Indus), three stations from the Ganga basin, and five stations from the Sabarmati basin.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

TraCE -21ka data were collected from National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) portal (https://gdex.ucar.edu/datasets/d651050/). Jürgen Bader provided data for MPI simulations upon request57, whereas IPSL-TR6AV (CM5A-LR) simulations were collected from the Center for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA) (https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/e43fc6e5bc754cd0aa8cfa70ab51f727/). Long-term instrumental data of rainfall91 is downloaded from (https://tropmet.res.in/static_pages.php?page_id=52). Speleothem data is downloaded from National Center for Environmental Information (NCEI) portal (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/paleoclimatology). Lake data is collected from the already published articles as mentioned in Table S2. The other datasets and shapefiles used in this study are available from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17231686.

Code availability

We have utilized publicly available source codes and manuals. The setup for the VIC model can be downloaded from https://vic.readthedocs.io/en/master/Overview/ModelOverview/. Data processing and plotting were performed using MATLAB 2023a, whereas QGIS 3.16.9 version was utilized for geospatial analysis.

References

Wright, R. P., Bryson, R. A. & Schuldenrein, J. Water supply and history: Harappa and the Beas regional survey. Antiquity 82, 37–48 (2008).

Madella, M. & Fuller, D. Q. Palaeoecology and the Harappan Civilisation of South Asia: a reconsideration. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 1283–1301 (2006).

Dutt, S., Gupta, A. K., Wünnemann, B. & Yan, D. A long arid interlude in the Indian summer monsoon during ∼4,350 to 3,450cal.yr BP contemporaneous to displacement of the Indus valley civilization. Quat. Int. 482, 83–92 (2018).

Petrie, C. A. & Bates, J. ‘Multi-cropping’, intercropping and adaptation to variable environments in Indus South Asia. J. World Prehist. 30, 81–130 (2017).

Pokharia, A. K. et al. Altered cropping pattern and cultural continuation with declined prosperity following abrupt and extreme arid event at ~4200 yrs BP: evidence from an Indus archaeological site, Khirsara, Gujarat, western India. PLoS ONE 12, e0185684 (2017).

Rawat, V. et al. Middle Holocene Indian summer monsoon variability and its impact on cultural changes in the Indian subcontinent. Quat. Sci. Rev. 255, 106825 (2021).

Kenoyer, J. M. Trade and technology of the Indus Valley: new insights from Harappa. Pakistan 29, 262–280 (2010).

Possehl, G. L. Climate and the Eclipse of the Ancient Cities of the Indus. Third Millennium BC Climate Change and Old World Collapse 193–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-60616-8_8 (1997).

Berkelhammer, M. et al. An abrupt shift in the Indian monsoon 4000 years ago. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 198, 75–87 (2012).

Dixit, Y. et al. Intensified summer monsoon and the urbanization of Indus Civilization in northwest India. Sci. Rep. 8, 4225 (2018).

Giosan, L. et al. Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109 (2012).

Laskar, A. H. & Bohra, A. Impact of Indian Summer monsoon change on ancient indian civilizations during the holocene. Front Earth Sci. 9, 1–14 (2021).

Staubwasser, M., Sirocko, F., Grootes, P. M. & Segl, M. Climate change at the 4.2 ka BP termination of the Indus valley civilization and Holocene south Asian monsoon variability. Geophys Res Lett 30, 8 (2003).

Das, A. et al. Evidence for seawater retreat with advent of Meghalayan era (∼4200 a BP) in a coastal Harappan settlement. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 23, e2021GC010264 (2022).

Singh, A., Ray, J. S., Jain, V. & Mahala, M. K. Evaluating the connectivity of the Yamuna and the Sarasvati during the Holocene: evidence from geochemical provenance of sediment in the Markanda River valley, India. Geomorphology 402, 108124 (2022).

Singh, A. et al. Larger floods of Himalayan foothill rivers sustained flows in the Ghaggar–Hakra channel during Harappan age. J. Quat. Sci. 36, 611–627 (2021).

Singh, A. et al. Counter-intuitive influence of Himalayan river morphodynamics on Indus Civilisation urban settlements. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–14 (2017).

Chatterjee, A., Ray, J. S., Shukla, A. D. & Pande, K. On the existence of a perennial river in the Harappan heartland. Sci. Rep. 2019 9, 1–7 (2019).

Bhushan, R. et al. High-resolution millennial and centennial scale Holocene monsoon variability in the Higher Central Himalayas. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 489, 95–104 (2018).

Dixit, Y. Regional character of the “global monsoon”: paleoclimate insights from Northwest Indian lacustrine sediments. Oceanography 33, 56–64 (2020).

Durcan, J. A. et al. Holocene landscape dynamics in the Ghaggar-Hakra palaeochannel region at the northern edge of the Thar Desert, northwest India. Quat. Int. 501, 317–327 (2019).

Kaboth-Bahr, S. et al. A tale of shifting relations: East Asian summer and winter monsoon variability during the Holocene. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021).

McClelland, H. L. O., Halevy, I., Wolf-Gladrow, D. A., Evans, D. & Bradley, A. S. Statistical Uncertainty in Paleoclimate Proxy Reconstructions. Geophys Res Lett. 48, e2021GL092773 (2021).

Sarkar, A. et al. Oxygen isotope in archaeological bioapatites from India: Implications to climate change and decline of Bronze Age Harappan civilization. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–9 (2016).

Tejavath, C. T., Upadhyay, P. & Ashok, K. The past climate of the Indian region as seen from the modelling world. Curr. Sci. 119, 316–327 (2020).

Enzel, Y. et al. High-resolution Holocene environmental changes in the Thar Desert, northwestern India. Science 284, 125–128 (1999).

Misra, P., Tandon, S. K. & Sinha, R. Holocene climate records from lake sediments in India: assessment of coherence across climate zones. Earth Sci. Rev. 190, 370–397 (2019).

Raj, R. et al. Holocene climatic fluctuations in the Gujarat Alluvial Plains based on a multiproxy study of the Pariyaj Lake archive, western India. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 421, 60–74 (2015).

Wasson, R. J., Smith, G. I. & Agrawal, D. P. Late quaternary sediments, minerals, and inferred geochemical history of Didwana Lake, Thar Desert, India. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 46, 345–372 (1984).

Prasad, S., Kusumgar, S. & Gupta, S. K. A mid to late Holocene record of palaeoclimatic changes from Nal Sarovar: a palaeodesert margin lake in western India. J. Quat. Sci. 12, 153–159 (1997).

Kathayat, G. et al. Evaluating the timing and structure of the 4.2 ka event in the Indian summer monsoon domain from an annually resolved speleothem record from Northeast India. Climate 14, 1869–1879 (2018).

Reddy, A. P., Gandhi, N. & Krishnan, R. Review of speleothem records of the late Holocene: Indian summer monsoon variability & interplay between the solar and oceanic forcing. Quat. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.QUAINT.2021.06.018 (2021).

Giesche, A. et al. Recurring summer and winter droughts from 4.2 to 3.97 thousand years ago in north India. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–10 (2023).

Petrie, C. A. et al. Adaptation to variable environments, resilience to climate change: investigating land, water and settlement in Indus northwest India. Curr. Anthropol. 58, 1–30 (2017).

Thirumalai, K. et al. Extreme Indian summer monsoon states stifled Bay of Bengal productivity across the last deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 18, 443–449 (2025).

Banerji, U. S., Arulbalaji, P. & Padmalal, D. Holocene variation in the Indian Summer Monsoon modulated by the tropical Indian Ocean sea-surface temperature mode. CATENA 30, 744–773 (2020).

Giesche, A., Staubwasser, M., Petrie, C. A. & Hodell, D. A. Indian winter and summer monsoon strength over the 4.2 ka BP event in foraminifer isotope records from the Indus River delta in the Arabian Sea. Climate 15, 73–90 (2019).

Dutt, S., Gupta, A. K., Devrani, R., Yadav, R. R. & Singh, R. K. Regional disparity in summer monsoon precipitation in the Indian subcontinent during Northgrippian to Meghalayan transition. Curr. Sci. 120 (2021).

Kathayat, G. et al. The Indian monsoon variability and civilization changes in the Indian subcontinent. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701296 (2017).

Dixit, Y., Hodell, D. A. & Petrie, C. A. Abrupt weakening of the summer monsoon in northwest India ~4100 yr ago. Geology 42, 339–342 (2014).

Deotare, B. C. et al. Palaeoenvironmental history of Bap-Malar and Kanod playas of western Rajasthan, Thar desert. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. Earth Planet. Sci. 113, 403–425 (2004).

Sinha, R. et al. Late Quaternary palaeoclimatic reconstruction from the lacustrine sediments of the Sambhar playa core, Thar Desert margin, India. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 233, 252–270 (2006).

Sengupta, T. et al. Did the Harappan settlement of Dholavira (India) collapse during the onset of Meghalayan stage drought?. J. Quat. Sci. 35, 382–395 (2020).

Mudra, L. et al. Unravelling the roles of orbital forcing and oceanic conditions on the mid-Holocene boreal summer monsoons. Clim. Dyn. 1, 1–20 (2022).

Yan, M. & Liu, J. Physical processes of cooling and mega-drought during the 4.2 ka BP event: results from TraCE-21ka simulations. Climate 15, 265–277 (2019).

Braconnot, P. et al. Impact of multiscale variability on last 6,000 years Indian and West African Monsoon Rain. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 14021–14029 (2019).

Tharammal, T. et al. Orbitally driven evolution of Asian monsoon and stable water isotope ratios during the Holocene: isotope-enabled climate model simulations and proxy data comparisons. Quat. Sci. Rev. 252, 106743 (2021).

Crétat, J., Braconnot, P., Terray, P., Marti, O. & Falasca, F. Mid-Holocene to present-day evolution of the Indian monsoon in transient global simulations. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2761–2784 (2020).

Bora Ön, Z. A Bayesian change point analysis re-examines the 4.2 ka BP event in southeast Europe and southwest Asia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 312, 108163 (2023).

Weiss, H. The East Asian summer monsoon, the Indian summer monsoon, and the midlatitude westerlies at 4.2 ka BP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200796119 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Reply to Weiss: Tree-ring stable oxygen isotopes suggest an increase in Asian monsoon rainfall at 4.2 ka BP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2204067119 (2022).

Scroxton, N. et al. Tropical Indian Ocean basin hydroclimate at the Mid- to Late-Holocene transition and the double drying hypothesis. Quat. Sci. Rev. 300, 107837 (2023).

Evans, M. N., Tolwinski-Ward, S. E., Thompson, D. M. & Anchukaitis, K. J. Applications of proxy system modeling in high resolution paleoclimatology. Quat. Sci. Rev. 76, 16–28 (2013).

Jiang, D., Tian, Z. & Lang, X. Mid-Holocene net precipitation changes over China: model–data comparison. Quat. Sci. Rev. 82, 104–120 (2013).

Morrill, C., Meador, E., Livneh, B., Liefert, D. T. & Shuman, B. N. Quantitative model-data comparison of mid-Holocene lake-level change in the central Rocky Mountains. Clim. Dyn. 53, 1077–1094 (2019).

Giosan, L. et al. Neoglacial climate anomalies and the Harappan metamorphosis. Climate 14, 1669–1686 (2018).

Bader, J. et al. Global temperature modes shed light on the Holocene temperature conundrum. Nat. Commun. 11, 4726 (2020).

Braconnot, P., Zhu, D., Marti, O. & Servonnat, J. Strengths and challenges for transient Mid- to Late Holocene simulations with dynamical vegetation. Climate 15, 997–1024 (2019).

Maupin, C. R. et al. Abrupt Southern Great Plains thunderstorm shifts linked to glacial climate variability. Nat. Geosci. 14, 396–401 (2021).

Mishra, V. & Aadhar, S. Famines and likelihood of consecutive megadroughts in India. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 1–12 (2021).

Niederman, E. A., Porinchu, D. F. & Kotlia, B. S. Hydroclimate change in the Garhwal Himalaya, India at 4200 yr BP coincident with the contraction of the Indus civilization. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–14 (2021).

Borah, P. J., Venugopal, V., Sukhatme, J., Muddebihal, P. & Goswami, B. N. Indian monsoon derailed by a North Atlantic wavetrain. Science 370, 1335–1338 (2020).

Sinha, A. et al. The leading mode of Indian Summer Monsoon precipitation variability during the last millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 15 (2011).

Hu, J., Dee, S., Parajuli, G. & Thirumalai, K. Tropical pacific modulation of the asian summer monsoon over the last millennium in paleoclimate data assimilation reconstructions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD039207 (2023).

Ossandón, Á, Gual, J., Rajagopalan, B., Kleiber, W. & Marchitto, T. Spatial and temporal bayesian hierarchical model over large domains with application to Holocene sea surface temperature reconstruction in the equatorial Pacific. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 39, e2024PA004844 (2024).

Gill, E. C., Rajagopalan, B., Molnar, P. & Marchitto, T. M. Reduced-dimension reconstruction of the equatorial Pacific SST and zonal wind fields over the past 10,000 years using Mg/Ca and alkenone records. Paleoceanography 31, 928–952 (2016).

Gill, E. C., Rajagopalan, B., Molnar, P. H., Kushnir, Y. & Marchitto, T. M. Reconstruction of Indian summer monsoon winds and precipitation over the past 10,000 years using equatorial Pacific SST proxy records. Paleoceanography 32, 195–216 (2017).

Gill, E. C., Rajagopalan, B. & Molnar, P. H. An assessment of the mean annual precipitation needed to sustain Lake Sambhar in Rajasthan, India, during mid-Holocene time. Holocene 25, 1923–1934 (2015).

Prasad, S. & Enzel, Y. Holocene paleoclimates of India. Quat. Res. 66, 442–453 (2006).

Pokharia, A. K., Kharakwal, J. S. & Srivastava, A. Archaeobotanical evidence of millets in the Indian subcontinent with some observations on their role in the Indus civilization. J. Archaeol. Sci. 42, 442–455 (2014).

MacDonald, G. Potential influence of the Pacific Ocean on the Indian summer monsoon and Harappan decline. Quat. Int. 229, 140–148 (2011).

Krishnamurthy, V. & Goswami, B. N. Indian monsoon–ENSO relationship on interdecadal timescale. J. Clim. 13, 579–595 (2000).

Zhao, C., Geng, X., Zhang, W. & Qi, L. Atlantic multidecadal oscillation modulates ENSO atmospheric anomaly amplitude in the tropical pacific. J. Clim. 35, 3891–3903 (2022).

Chowdary, J. S. & Gnanaseelan, C. Basin-wide warming of the Indian Ocean during El Niño and Indian Ocean dipole years. Int. J. Climatol. 27, 1421–1438 (2007).

Mishra, V., Smoliak, B. V., Lettenmaier, D. P. & Wallace, J. M. A prominent pattern of year-to-year variability in Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7213–7217 (2012).

Li, C. & Yanai, M. The onset and interannual variability of the asian summer monsoon in relation to land–sea thermal contrast. J. Clim. 9, 358–375 (1996).

Ramanathan, V. et al. Atmospheric brown clouds: impacts on South Asian climate and hydrological cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5326–5333 (2005).

Roxy, M. K. et al. Drying of Indian subcontinent by rapid Indian ocean warming and a weakening land-sea thermal gradient. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–10 (2015).

Moreno-Chamarro, E., Marshall, J. & Delworth, T. L. Linking ITCZ migrations to the AMOC and North Atlantic/Pacific SST decadal variability. J. Clim. 33, 893–905 (2019).

Ding, Q. & Wang, B. Circumglobal teleconnection in the northern hemisphere summer. J. Clim. 18, 3483–3505 (2005).

He, F. Simulating Transient Climate Evolution of the Last Deglaciation with CCSM3 (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011).

Schneider, A. W., Gill, E. C., Rajagopalan, B. & Algaze, G. A trade-friendly environment?: Newly reconstructed indian summer monsoon wind stress curl data for the third millennium BCE and their potential implications concerning the development of early Bronze Age trans-Arabian sea maritime trade. J. Marit. Archaeol. 16, 395–411 (2021).

Degroot, D. et al. Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change. Nature 591, 539–550 (2021).

Askjær, T. G. et al. Multi-centennial Holocene climate variability in proxy records and transient model simulations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 296, 107801 (2022).

Jiang, Z. et al. No consistent simulated trends in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation for the past 6,000 years. Geophys Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103078 (2023).

Prasad, V. et al. Mid-late Holocene monsoonal variations from mainland Gujarat, India: a multi-proxy study for evaluating climate culture relationship. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 397, 38–51 (2014).

Kathayat, G. et al. Indian monsoon variability on millennial-orbital timescales. Sci. Rep. 6, 24374 (2016).

Chen, J., Zhang, Q., Kjellström, E., Lu, Z. & Chen, F. The contribution of vegetation-climate feedback and resultant sea ice loss to amplified arctic warming during the mid-Holocene. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098816 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Simulating the mid-Holocene, last interglacial and mid-Pliocene climate with EC-Earth3-LR. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 1147–1169 (2021).

He, C. et al. Hydroclimate footprint of pan-Asian monsoon water isotope during the last deglaciation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe2611 (2021).

Sontakke, N. A., Singh, N. & Singh, H. N. Instrumental period rainfall series of the Indian region (AD 1813—2005): revised reconstruction, update and analysis. Holocene 18, 1055–1066 (2008).

Mishra, V. et al. Drought and Famine in India, 1870–2016. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 2075–2083 (2019).

Liang, X., Lettenmaier, D. P., Wood, E. F. & Burges, S. J. A simple hydrologically based model of land surface water and energy fluxes for general circulation models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 99, 14415–14428 (1994).

Shah, H. L. & Mishra, V. Hydrologic changes in indian subcontinental river basins (1901–2012). J. Hydrometeorol. 17, 2667–2687 (2016).

Kushwaha, A. P. et al. Multimodel assessment of water budget in Indian sub-continental river basins. J. Hydrol. 603, 126977 (2021).

Lohmann, D., Nolte-Holube, R. & Raschke, E. A large-scale horizontal routing model to be coupled to land surface parametrization schemes. Tellus A 48, 708–721 (1996).

Davison, A. C. & Hinkley, D. V. Bootstrap methods and their application. Bootstrap Methods and their Application https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511802843 (1997).

McKee, T. B., McKee, T. B., Doesken, N. J. & Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 7, 17–22 (1993).

Chuphal, D. S., Kushwaha, A. P., Aadhar, S. & Mishra, V. Drought Atlas of India, 1901–2020. Sci. Data 11, 1–12 (2024).

Aadhar, S. & Mishra, V. High-resolution near real-time drought monitoring in South Asia. Sci. Data 4, 1–14 (2017).

Wang, Q. et al. An improved daily standardized precipitation index dataset for mainland China from 1961 to 2018. Sci. Data 9, 1–12 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the data provided by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (MPIMET), and Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace (IPSL). The work was primarily supported by the funding from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. K.T. acknowledges support from NSF P2C2 Award 2103077. All datasets are freely accessible, with the exception of MPI datasets, which were graciously provided by Jürgen Bader upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. and V.M. conceived and designed the study, formulated the research questions, and developed the methodology. H.S. conducted the analysis and compiled the results. H.S., V.M., and K.T. interpreted the results. Furthermore, H.S., V.M., K.T., V.J., and B.R. provided critical insights during the manuscript drafting process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors of this manuscript declare no competing interests in relation to the research, authorship, or publication of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Feng Shi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Patricia Spellman and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Solanki, H., Jain, V., Thirumalai, K. et al. River drought forcing of the Harappan metamorphosis. Commun Earth Environ 6, 926 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02901-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02901-1

This article is cited by

-

Centuries of repeated droughts linked to the Indus Valley Civilisation’s decline

Nature India (2025)