Abstract

Tropical North Atlantic sea surface temperatures and low-latitude rainfall covary, but prehistoric subtropical rainfall records are often misaligned. Here, a submarine groundwater discharge record from the northern Bahamas archives regional water balance in the northeastern Atlantic Warm Pool. We compare the reconstruction to the tropical North Atlantic seasonal temperature gradient, which can help inform how northeastern Caribbean rainy seasons are influenced by the Atlantic Warm Pool. A positive water balance in the northern Bahamas aligned with a ~0.9 °C seasonal temperature gradient from 0 to 950 CE, with both covarying on multi-decadal timescales. Aridity began at ~950 CE when a ~2.2 °C seasonal temperature gradient increase likely shortened the wet season. From 1450 to 1850 CE, frequent hurricanes offset aridity in the northeastern Caribbean by elevating rainfall. This record archives time-transgressive changes in hydroclimate forcing, and suggests that projected changes to rainfall seasonality must be considered when assessing tropical water security risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitigating future water scarcity and economic risk requires establishing the natural drivers of hydro-meteorological disasters (drought, floods, and hurricanes). However, there is spatiotemporal complexity1 in hydroclimate records from the lower latitudes in the Atlantic Ocean, where seasonal changes to the North Atlantic Subtropical High (NASH), Intertropical Convergence Zone, and the Atlantic Warm Pool (AWP) drive distinct wet and dry seasons2,3. Whereas hydroclimate events like the 800–1050 Common Era (CE) drought are regionally documented4, many subtropical North Atlantic paleo hydroclimate records during the CE exhibit divergent variability. At ~1000 CE, for example, the Gulf of Mexico (GoM) and tropical North Atlantic (TNA) started a ~1 °C cooling trend5,6 that culminated in ~3 °C boreal winter cooling during the Little Ice Age (LIA: 1450–1850 CE) 7. While observed sea surface temperature (SST)-hydroclimate relationships suggest that the subtropical North Atlantic should have become more arid, as was recorded by Cuban lagoon sediment8, a Cuban speleothem9 and Bahamian organic geochemical proxies10 document wetter conditions starting at 1000 CE. The subtropical Atlantic is a key locality to understand prehistoric NASH-AWP dynamics, which is critical because future NASH expansion11 is projected to increase regional evaporative demand.

Hurricanes also augment regional moisture supply, with distinct forcing mechanisms as compared to other regional hydroclimate variability. While hurricanes catastrophically impact local socioeconomics12, they may mitigate future Caribbean water scarcity problems13,14 through their contributions to local rainfall15,16. Only rare paleo-hydroclimate records can distinguish between synoptic and hurricane-mediated rainfall signals. On paleo timescales, this is further complicated by recent findings that historically unprecedented hurricane activity has been spatially asynchronous in the Atlantic during the CE17,18,19. Thus, large uncertainty persists in disentangling the imprints of hurricane activity on paleo hydroclimate records from this water-sensitive region.

Here, Bahamian water balance is inferred from a high-resolution record of benthic foraminiferal paleoecology from a coastal blue hole. On carbonate landscapes, underground meteoric lenses form when a positive water balance favors aquifer recharge (i.e., precipitation > evapotranspiration) as rain infiltrates into the landscape. Aquifers subsequently discharge at coastal zones as submarine groundwater discharge (SGD) 20,21, which can promote hydrographic stratification in oceanic blue holes acting as springs. SGD is a key part of the hydrologic cycle that influences coastal biogeochemistry22,23,24 and ecosystems25,26,27. This work demonstrates that SGD has been an overlooked opportunity to explore landscape-integrated signals of excess moisture. In The Bahamas, time-transgressive changes in hydroclimate forcing means that meteorological data from the instrumental record alone is insufficient to inform on hydroclimate conditions during intervals unlike the last ~150 years.

Hydroclimate in The Bahamas

The northeastern Caribbean hydroclimate zone including Abaco Island (Fig. 1A, see supplementary information) experienced ~1297 mm/yr mean annual precipitation (MAP) from 1855 to 2017 CE (range: 603–2521 mm/yr), in near balance with 1198 mm/yr14 potential evapotranspiration [PET, 1950–2016 CE]. This highly sensitive water balance leaves little difference between when meteoric lenses are recharged by precipitation (P) or depleted by evapotranspiration (ET) 28. Whitaker and Smart20 estimate that 25% of MAP is available for effective aquifer recharge because most Bahamian islands have some meteoric lenses21. In contrast, diminished P and aquifer recharge can shrink meteoric lenses within months29. MAP at Abaco Island is partly driven by hurricane-mediated rainfall, for example, Hurricane Dorian in 2019 (a category 5 event) delivered 580 mm (45% of MAP) in just 3 days30.

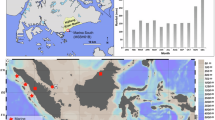

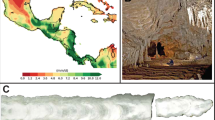

A Correlation between mean annual precipitation (MAP) from the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC) Full Data Reanalysis66 and the areal extent of the summer (ASO) Atlantic Warm Pool (AWP, area >28.5 °C isotherm) extracted from NOAA Extended Reconstructed SSTv567 between 1891 and 1970 CE to avoid bias from recent anthropogenic effects68. Stippling indicates regions where the correlations passed the Student’s t-test at the 99th percentile (p < 0.01). A 30-year running mean was applied to both MAP and AWP extents to highlight decadal-scale variability. The blue region illustrates mean ASO AWP extent over the historical period (1891–1970 CE). The black box encompasses the Cariaco region (9° to 12° N, –70° to –60° W) as defined for this study. Black contours (upper right) indicate historical mean NASH extent as defined by the 1018, 1020, and 1022 hPa SLP isobars extracted from NOAA-CIRES-DOE 20th Century Reanalysis v3. Red star: Abaco Island, The Bahamas. B Box and whisker plots showing standardized positive and negative MAP anomalies (measured directly from the Nassau rain gauge) when the Cariaco regional seasonal temperature gradient (MJJASO average minus NDJFMA average) from the NOAA Extended Reconstructed SSTv5 exceeds (falls below) the 75th (25th) percentile between 1891–1970 CE. A 30-year moving average was applied to all data. All relationships are statistically significant at p < 0.01. C Time series showing MAP (grey) and mean annual temperature (MAT: blue) recorded at Nassau in The Bahamas between 1855 and 2015 CE (accessed via NOAA’s Global Historical Climatology Network; GHCN), and the adjusted potential evapotranspiration (PET: purple) for the Northern Bahamas14. D Aerial photograph of Freshwater River Blue Hole. E Conceptual model depicting how SGD develops from excess moisture supply when rainfall exceeds evaporative demand.

In this hydroclimate zone, 75% of MAP is delivered during boreal summer and mediated by AWP-NASH dynamics (Figs. S1–S3). Winter rainfall is partially linked to the El Niño/Southern Oscillation and Pacific influences3,31 (mean: 315 mm/yr, range: 206–420 mm/yr), but as this is the dry season, Atlantic processes primarily control MAP in The Bahamas (see supplemental text). As the AWP expands in the early summer and reaches the Bahamian archipelago, both NASH western boundary convergence and the wet season begin2,32,33. In the late summer, the Caribbean wet season ends first in The Bahamas as cooler SSTs arrive from AWP retreat and the NASH contracts eastward2. The Bahamas is an ideal location to observe this phenomenon, as its geography and wet season sensitivity to the NASH and AWP allow it to record spatial variability in prehistoric AWPs. MAP over The Bahamas is increased by larger AWP size and the timing of its arrival. For the latter, a weaker seasonal temperature gradient may indicate a longer wet season, as warmer winter and spring temperatures promote earlier AWP expansion toward The Bahamas and thus increased persistence. Indeed, from 1891 to 1970 CE, increased MAP in The Bahamas is associated with a weaker seasonal temperature gradient in the tropical Atlantic Cariaco region (Fig. 1B).

Freshwater River Blue Hole

Freshwater River Blue Hole (FRSH, Fig. 1, 26.426°N, –77.175°W) is on the leeward carbonate tidal flats of Abaco (~700 km2), which have experienced 1.4 ± 0.5 m of sea-level rise during the CE34. The sediment-water interface in the blue hole center is 5 m below sea level (mbsl), but caves around the periphery deepen to 50 mbsl. Seasonal water column salinity (18.2 to 36.2 psu), pH (6.7 to 8.1), and dissolved oxygen (<0.3 to 6.2 mg/l) reveal a transient meteoric cap whose vertical extent allows a local pycnocline to persist near the sediment-water interface in the blue hole middle (Fig. S4). P and SGD form the meteoric cap, and it decays by E, seawater tidal exchange, and SGD cessation35. Hydrographic monitoring indicates that a meteoric cap can develop in FRSH during any season from increased P or decreased ET, and it may decay in less than a year (Figs. S4, S5). Benthic foraminifera adapted to brackish, organic-rich, and oxygen-depleted conditions dominate the modern blue hole population (e.g., Ammonia, Cribroelphidium), and not the larger miliolids commonly found on the tidal flats (e.g., Peneroplis)35.

Blue hole sediment cores (FRSH-C2, FRSH-C3) reveal a strikingly laminated and bedded ~230 cm carbonate mud unit preserved by benthic hypoxia during the CE. A robust radiocarbon age model developed with mangrove leaves indicates high sedimentation rates: 0.5 to 1.0 mm/yr from 0 to ~1020 CE gradually increased to 2 mm/yr from ~1020 to 2016 CE (Figs. S5–S7, Table S1). Thicker organic-rich horizons from 0 to 850 CE in FRSH-C3 (mean 35% bulk organic matter) transition to millimeter-scale laminations during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA: 950 to 1450 CE), and thicker organic-rich beds reappear from 1450 CE to present. The organic-rich horizons are dominated by fine-grained organic particles, likely degraded products of aquatic primary productivity36,37,38. Hurricane Dorian (category 5, Saffir-Simpson Scale) had negligible impact on regional carbonate flat geomorphology (Figs. S8, S9), which is like observations elsewhere39,40.

The water balance index (WBI)

Subfossil benthic foraminifera can be organized into a WBI, which is the arithmetic sum of the proportion of 6 foraminifera taxa with a similar ecological behavior. Their changes in relative abundance and diversity reflects a well-established ecological response to environmental conditions at the sediment-water interface, and these conditions are regulated by SGD (Fig. 2B). First, cluster analysis grouped benthic foraminiferal samples into communities with abundant smaller miliolids (groups 1-2). The WBI includes samples with an increasing proportion of 6 taxonomic units (groups 3–8): Ammonia beccarii, Cribroelphidium poeyanum, Cribroelphidium gunteri, Pseudoeponides anderseni, Psuedoeponides davescottensis, and Trichohyalus aguayoi (Figs. S10, S11). These 6 taxa tolerate lower dissolved oxygen, lower salinity, and high organic matter (see supplementary text). For example, A. beccarii dominates group 8 (mean 79.4%) relative to miliolids (mean 16.7%), whereas groups 1-2 contain mostly small Quinqueloculina and Triloculina (mean 81.6%). Miliolid taxa would favor a more negative water balance (reduced P or greater ET) from reduced stratification, increased benthic ventilation, and microbial organic matter remineralization. Winter cooling and convection during more negative water balance conditions would further favor benthic ventilation and miliolid populations. Since ET is highly correlated to atmospheric temperature41,42, regional warming would make FRSH more favorable to miliolids by increasing evaporative demand.

A A 1500-year compilation of near-annually resolved paleo hurricane reconstructions from the Bahamian Archipelago (Grand Bahama, Abaco, Long Island, Andros Island, Caicos Island), smoothed with a 100-yr moving window18. Shaded confidence intervals are calculated from the ages produced in Monte Carlo age-simulations. B Benthic foraminiferal WBI (this study), where color-coded bars correspond with 8 groups of samples that reflect a similar community structure (see also Fig. S10): wetter (dryer) intervals are shaded with increasingly darker blue (red) colors. C Compiled (Z-score) of annual SST records from the Great Bahama Bank (sclerosponge at 130 mbsl69, surface coral70). D Seasonal temperature gradient from the Cariaco Basin. Note the inverted y-axis. E Mg/Ca-based SSTs from Globigerinoides ruber as a proxy for summer/fall SSTs7. F Mg/Ca-based SSTs from G. bulloides as a proxy for winter/spring SSTs7. Dark lines are 30-year moving average. Pink (red) vertical bars highlight intervals of water balance conditions like (or more arid than) present. TNA: tropical North Atlantic.

Ordination and isotopic analysis introduce further confidence that the WBI is reflecting SGD and water column stratification. Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA, Fig. S10) Axis 1 explained 46.8% of the data variance, and samples have a higher DCA Axis 1 value if they have higher proportions of the 6 taxa grouped into the WBI (r = 0.95, p < 0.001). Bulk organic matter was also correlated to DCA Axis 1 (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), and the WBI was independently correlated to bulk organic matter (r = 0.56, p < 0.001). An increasing (decreasing) WBI, increasing (decreasing) organic matter preservation, and decreasing (increasing) miliolids are significantly linked. An alternate hypothesis would state that during periods of less SGD, more evaporation and local aridity would vertically contract the meteoric lens, and in turn increase benthic hypoxia, organic matter preservation, and bathing of the sediment-water interface with more saline groundwater. However, species-specific stable oxygen (δ18Oc) and carbon (δ13Cc) isotopic analysis indicates the opposite: WBI taxa secreted their tests in seawater more diluted by meteoric water from SGD (Fig. S12, see supplementary text). In a last millennium time series analysis, the difference in δ18Oc values on miliolids vs. WBI taxa (Δ18Om−WBI) indicates more frequent SGD of meteoric water during the LIA than MCA. In short, higher (lower) WBI values indicate when a more (less) positive water balance on the Abaco landscape enhanced (depressed) SGD and promoted (hampered) hydrographic stratification in FRSH.

The WBI is limited by not having a direct calibration to SGD, but only indirectly through an assessment of local changes in rainfall and temperature during the instrumental and historical period. These comparisons indicate that the WBI is not a simple proxy for precipitation, temperature, or evaporation alone, but the WBI is most likely reflecting the SGD of meteoric water in response to a positive water balance on the landscape. For example, a notable WBI decrease from ~0.7 to 0.2 at ~1960 CE (Fig. 2B) is within radiocarbon uncertainty of when Bahamian MAT increased from 24.3 ± 0.4 °C (1855 to 1970 CE) to 25.4 ± 0.4 °C (1971 to 2014 CE, Fig. 1C), while MAP stayed relatively stable. Increasing air temperatures (both summer and winter, Fig. S1) and local ET14,41,42 (Fig. 1C) thus likely suppressed SGD to create conditions more favorable to miliolids and resulted in a lower WBI value in years younger than ~1960 CE. In contrast, precipitation alone does not drive foraminiferal diversity. NASH expansion from 1910 to 1940 CE suppressed the wet season43 and caused a MAP decrease to ~800 mm/yr (Figs. 1C, and S1). While sedimentation rates and radiocarbon uncertainties are sufficient to resolve this event, the WBI does not respond to this multi-decadal MAP change. This could be because of compensating impacts from relatively low MAT during this period helped limit ET and maintain the water balance. A direct calibration of the water balance index is further limited because local hurricane activity during the last 150 years is not representative of the full potential of hurricane-mediated rainfall on the landscape based on multi-centennial reconstructions. Direct monitoring of SGD through FRSH is an important opportunity for creating more quantified relationships between local water balance, SGD and benthic biodiversity and geochemical changes. Nevertheless, benthic foraminifera are highly sensitive environmental indicators that would respond to environmental changes at the sediment-water interface 5 msbl, which is most likely caused by changes in the local water balance altering SGD.

Each WBI datapoint reflects a multi-year average (5–20 years) of environmental conditions at each core site. This is because (i) each foraminiferal sample averages multiple years (0 to 1020 CE: 10–20 years/sample, 1020 CE to present: ~5 years/sample), (ii) the vertical water column structure in FRSH is seasonally unstable, and (iii) benthic foraminifera can exhibit boom-bust population changes in <1 year44. A single environmental parameter cannot explain foraminiferal population changes because WBI taxa all tolerate low salinity, hypoxia, and abundant organic matter45,46,47. When conservatively used the WBI provides a detailed perspective of excess moisture supply and SGD (Fig. 2B, see supplementary text).

Time-transgressive hydroclimate forcing

Instrumental data, paleo studies, and models routinely link circum-Caribbean precipitation variability to tropical Atlantic SSTs1,32,48, but nowhere is moisture supply more sensitive to the AWP than The Bahamian archipelago in the northeastern Caribbean2. During the instrumental record, the TNA seasonal temperature gradient is associated with MAP in the northeastern Caribbean, mostly likely through the timing of AWP arrival, its persistence, and the associated AWP impact on wet season length (Fig. 1B). The only available record to derive a tropical seasonal temperature gradient proxy is the seasonally-resolved SST record from the Cariaco Basin7 (Fig. 2D). Whereas the Cariaco Basin is ~2100 km southeast of The Bahamas, its SST is highly correlated to broader TNA (6° to 22° N, –75° to –15° W) SST anomalies (r = 0.94, p < 0.001) and to AWP extent (r = 0.89, p < 0.001)32. Like others7, we also infer Mg/Ca ratios in the planktic Globigerina bulloides as a proxy for winter/spring SSTs versus G. ruber to infer summer/fall SSTs (Fig. 2E, F). Indeed, G. bulloides can re-bloom in the late summer and it has a slightly deeper habitat (~30 m depth). However, differencing these signals provides the only annually resolved proxy for the tropical Atlantic seasonal temperature gradient (Fig. 2D). A higher (lower) seasonal temperature gradient in the Cariaco Basin suggests a shorter (longer) wet season in the northern Bahamas.

During the first millennium of the CE, the seasonal temperature gradient averages 0.9 ± 0.5 °C, and the WBI is qualitatively more positive than during the second millennium. However, there is evidence for less SGD at 125 CE, 425 CE, 625, and 800 CE synchronous with multi-decadal increases (>1 °C) in the seasonal temperature gradient (Fig. 2D). Within radiocarbon uncertainty, colder conditions were also detected in lower-resolution SST reconstructions at 450, 600, and 850 CE in the southeastern Caribbean1 and northern GoM5 (Fig. S14). In contrast, periods with the most positive water balances (centered at 50 CE, 275 CE, 525 CE, and 725 CE) coincide with reduced (–1 to 1 °C) seasonal temperature gradients, which suggests longer wet seasons in the northeastern Caribbean. The close visual covariance between Abaco hydroclimate and the Cariaco Basin seasonal temperature gradient introduces further confidence in the Cariaco Basin as a robust reconstruction of seasonal SSTs (Fig. 2E, F).

From ~950–1450 CE, lower WBI values indicate less SGD and water column stratification. Sedimentation rate and adult-size miliolid foraminifera increased (e.g., Quinqueloculina tenagos), which is consistent with aridity decreasing SGD and promoting abiotic carbonate deposition. Evidence for AWP changes at ~1000 CE was previously documented in the northern GoM based on (i) decreasing Globigerinoides sacculifer abundance, a planktic foraminiferal proxy for Loop Current penetration49, and (ii) cooler SSTs based on Mg/Ca-δ18Oc measurements of planktic foraminifera5. This suggests that a change in ocean circulation also occurred at 1000 CE, which may have contributed to seasonal temperature gradient changes. Nearby Cuban lagoons document a synchronous aridity trend8 that deepens through the LIA, along with Caribbean-wide droughts from 800 to 1200 CE4. The MCA experienced ~1 °C atmospheric warming in the TNA50,51, which would have amplified local evaporative demand similar to the period from 1960 CE to present (Fig. 1C). While summer/fall SSTs are greatest during the MCA (~28.75 °C, Fig. 2E), the sharp winter/spring SSTs cooling at ~1000 CE markedly increased the seasonal temperature gradient to 2.2 ± 0.4 °C during the second millennium of the CE (Fig. 2D). If correct, this should have caused a concomitant change in the AWP, as supported by lower WBI values.

Counterintuitively, WBI values indicate greater moisture supply from 1425 to 1625 CE (Fig. 2B) when the southeastern Caribbean1 and northern GoM5 are colder, and there is a greater seasonal temperature gradient (Figs. 2D, and S14). We hypothesize that the greatest increase in hurricane activity observed over the last 1500 years in the northern Bahamas compensated local water balance (Fig. 2A). Specifically, Abaco Island transitioned from ~6 to ~13 hurricanes per century by 1500 CE as observed elsewhere at Thatchpoint Blue Hole (Fig. S11). On the other hand, the WBI decreased from ~1650 to 1725 CE along with local hurricane activity18,52,53. From 1750 to 1850 CE, the seasonal temperature gradient exhibits a largely secular decreasing trend (Fig. 2D), and Bahamian hurricane activity increased (Fig. 2A, C), which together likely favored increased local moisture supply (Fig. 2B). While there were fewer local hurricanes during the 1960s–1980s CE18, the onset of modern Caribbean warming54,55 and aridity56 (Fig. 1C) likely caused the recent WBI decrease at ~1960 CE, which is strikingly like the WBI observed during the MCA.

Assessing future hydroclimate in the context of CE paleoclimate

Coarsely resolved state-of-the-art climate models cannot realistically simulate highly regional hydroclimate processes, so projections of current and future northern Caribbean hydroclimate are highly uncertain. Nevertheless, current and future seasonal temperature gradient changes are important to quantify given (i) long-term linkages between the Cariaco region seasonal temperature gradient and northern Caribbean hydroclimate demonstrated herein, and (ii) the large variability in the seasonal temperature gradient over the CE (Fig. 2D). Curiously, the only two simulations spanning the CE do not exhibit large seasonal temperature gradient variability like the Cariaco record (Fig. 3A). Nevertheless, both observations (–0.53) and historical simulations (ensemble mean of –0.25) from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6 (CMIP6) suggest that the seasonal temperature gradient has already increased from anthropogenic forcing (88% of simulations show an increase: Fig. 3B). The seasonal temperature gradient is projected to further increase under both a lower (SSP2-4.5) and higher (SSP5-8.5) emissions scenario, with an ensemble mean change of –0.39 (66% of simulations show an increase) and –0.46 (63% of simulations show an increase) by the end of the 21st century, respectively (Fig. 3B). In two of the SSP5-8.5 simulations the projected seasonal temperature gradient change is larger than the difference between the first and second millennium of the CE (Fig. 3A—fifteen simulations exceed the 25th percentile of the differences between all 30-year periods in the first and second millennium of the CE). While considerable winter SST cooling increased the seasonal temperature gradient in the second millennium of the CE, summer SSTs are warming faster than their winter counterparts (not shown) in both model simulations and recent observations. Despite these differences, the large projected changes to the seasonal temperature gradient suggest the potential for even starker drying in the northern Caribbean by the end of the 21st century, perhaps exceeding the reconstructed aridity observed (i) during the MCA and (ii) since 1960 CE by the WBI Index (Fig. 2B). A future research priority should contextualize projected changes to the seasonal temperature gradient in terms of wet season duration and AWP-NASH dynamics11,57. It remains a challenge to quantify first to second millennium climate changes because most CE simulations begin in 850 CE. Understanding the MCA onset and using it as a target for climate model validation may require past2k simulations like those used herein.

A (black) 30-year running mean seasonal temperature gradient standardized relative to 1901–2004 from W2013, (red) same but for the Cariaco region in the past2k simulation from MPI-ESM (SSTs averaged for 9° to 12° N, –70° to –60° W), (blue) same as red but from CESM1. The dotted and dashed lines are the mean standardized seasonal temperature gradient from W2013 for 950–2008 CE and 0–950 CE, respectively. B (left) Differences in the Cariaco region standardized seasonal temperature gradient between 1985–2014 CE relative to 1901–1930 CE for observations67 (black dot) and historical simulations (n = 401, Table S2), (center) same but for 2071–2100 CE relative to 1901–1930 CE using SSP2-4.5 (n = 121, Table S2), (right) same as center but for SSP5-8.5 (n = 133, Table S2). The dashed-dotted line is the difference in the standardized seasonal temperature gradient between 950–2008 CE relative to 0–950 CE in W2013 (see dotted and dashed line in A) and the gray shading is the 25th–75th percentile of the differences between all 30-year periods in 950–2008 CE relative to those in 0–950 CE. The box plot whiskers show the full data range, the light shading is the 5th–95th percentile, the dark shading is the 25th–75th percentile, and the dark line is the median. Standardized seasonal temperature gradients are used throughout for comparability between the proxy record (from a single location) and the regularly gridded observations and simulations.

Conclusions

Evaluating paleo water balance using SGD is a powerful and global opportunity. In the northern Bahamas, it was previously observed that the water column characteristics in a coastal blue hole respond to SGD of meteoric water from a positive water balance on the local landscape35. Assuming benthic foraminiferal diversity and test isotopic variability are reliable indicators of hydrographic conditions at the sediment-water interface, a reconstruction of SGD indicates local water balance changes during the last 2000 years. While challenges remain with providing a direct validation between the WBI and local SGD with meteorological variables, improvements to hydrographic monitoring in blue holes and meteorological monitoring on remote landscapes could greatly improve the potential for future quantitative paleo reconstructions.

While only using the WBI proxy as a qualitative indicator of local water balance change, SGD oscillations during the last 2000 years most likely reflect time-transgressive hydroclimate forcing. These reconstructed water balance changes in the first millennium CE appear linked to oscillating seasonal temperature gradients in the Atlantic that influenced wet season duration through AWP-NASH dynamics. During the MCA, a larger 2–3 °C seasonal temperature gradient likely shortened the wet season, reduced synoptic moisture delivery, increased evaporative demand, and depressed water balance. During the LIA, increased regional hurricane activity offset drying by supplementing local rainfall, illustrating the critical need to independently assess local hurricane contributions in paleo-hydroclimate reconstructions. Specifically, comparing Caribbean hydroclimate records may produce misleading conclusions if prehistoric unprecedented hurricane activity is not considered. Climate models project greater seasonal temperature gradients in the 21st century—some exceeding those observed during the CE—suggesting the subtropical Atlantic may face future aridity worse than the MCA. Small island developing states must therefore consider both shifting hurricane climatology and changes in synoptic moisture delivery to ensure future water security.

Methods

Historical regional rainfall

Monthly rainfall data from the Nassau Rain Gauge (200 km away from Abaco, https://climexp.knmi.nl/start.cgi) from 1855 to 2014 CE can provide a surrogate for the long-term hydroclimate zone that includes Abaco2,3. Missing temperature and rainfall observations were backfilled with the climatological mean for the respective month3. For rainfall, 7% of monthly observations are missing, with the longest multi-year gap occurring from 1892 to 1895 CE. There were 13.5% of missing observations for temperature, with the longest multi-year gaps from 1867 to 1873 CE, 1892 to 1895 CE, and 1921 to 1923 CE. The resulting infilled data was used to generate summary statistics and plots.

Lithology, chronology and age models

The two cores FRSH-C3 and FRSH-C2 preserve a carbonate mud unit that was continuously deposited in the blue hole during the CE58. Age control was established by first developing a detailed radiocarbon-based age model for FRSH-C3 using Bayesian statistical approaches59, and then transferring the ages on 22 stratigraphic surfaces (i.e., tie-points) from FRSH-C3 to FRSH-C2 (Table S1). FRSH-C3 has the most expanded stratigraphy, and time-synchronous stratigraphic horizons can be correlated between FRSH-C3 and FRSH-C2. This approach means that the two cores are not true replicates of a resultant signal, but it ensures that the same stratigraphic layering in each core has an identical age. More importantly, it amplifies the signal-to-noise ratio of any resultant environmental signal, and it tests the reliability of an environmental signal versus any artefact from the natural patchiness of benthic foraminiferal populations. In total, 35 samples of terrestrial plant pieces (i.e., seeds, leaves, etc.) were dated from the bedded carbonate unit in FRSH-C3 by accelerator mass spectrometry at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (Table S1). Age models were constructed by setting the core-top (depth of 0 cm) to the collection year of 2016 CE (–66 Cal yrs BP), calibrating conventional age results to calendar years using IntCal2060, and calculating ages for stratigraphic levels using a Bayesian statistical approach (rbacon package version 3.0.0)59. In the upper part of FRSH-C3, the transition from F14C > 1.0000 (0–13.5 cm in FRSH-C3) to F14C < 1.0000 (14.5 cm) indicates that the 1950 CE chronohorizon occurs at 14.0 ± 0.5 cm (Fig. S6). Sensitivity tests were conducted for the age model settings in the package rbacon, and this exercise determined that an accumulation strength of 4 and memory of 0.7 caused the 1950 CE chronohorizon to occur between 11.5 cm and 14.5 cm in FRSH-C3 as per the F14C results (Fig. S7). The final age model for FRSH-C3 was calculated using these software settings and the date of 1950 CE applied to 14.0 cm depth. To apply the age model from FRSH-C3 to FRSH-C2, twenty-three separate chronohorizons (or tie-points: Table S1) were first isolated in both cores by correlating prominent bedding planes. Then, the output from the FRSH-C3 at that time horizon was applied to the synchronous stratigraphic depth in FRSH-C2. Ages between each tie-point in FRSH-C2 were then interpolated in rbacon. The bulk organic matter content and coarse sediment content described elsewhere are reused here58, and plotted against age model results (Fig. S9).

Benthic foraminifera and charophytes

FRSH-C2 and FRSH-C3 were subsampled downcore to investigate foraminiferal paleoecology. A total of 145 stratigraphic levels were investigated in both cores. FRSH-C3 was subsampled from 2 to 233 cm core depth with 0.63 cm3 of sediment, every 2 cm, with each subsample spanning 1 cm (n = 116). A 1.25 cm3 sediment subsample was obtained from FRSH-C2 every 5 cm from the core top to 139 cm, with each sediment sample spanning 1 cm (n = 29 samples). From 0 to 1020 CE, 1-cm homogenized sediment sub-sample averages 10–20 years, versus just 5 years from 1020 CE to present. Subsamples were first wet sieved over a 63-µm mesh sieve to concentrate foraminifera, and the wet residues were immediately visually inspected under a stereomicroscope to first pick-out any agglutinated taxa (e.g., Trochammina). The remaining sediment residues were desiccated in a low temperature drying oven, and foraminifera picked onto micropaleontological slides. A final census of >250 individuals per sample was sought to minimize standard error on the dominant taxa61, which was achieved in 81.3% of the stratigraphic levels. A total of 51,043 and 18,980 foraminifera were picked and counted in all sediment residues processed from FRSH-C3 and FRSH-C2, respectively.

Benthic foraminiferal taxonomy started with Loeblich and Tappan62, at the specific and generic level, where possible, and confirmed via the World Register of Marine Species63. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging was used to confirm identification of the dominant taxa using a Hitatchi TM3000 TableTop SEM on representative specimens. When possible, foraminifera were identified to the species level in the original database that contained 40 taxonomic units (i.e., observations) identified in 138 samples or stratigraphic levels (i.e., 7 levels did not contain foraminifera). However, a final database was compiled by grouping some species together at the generic level to reduce bias caused by misidentification of juveniles or small-sized individuals. This was especially apparent with smaller, elongated miliolids in the ~63–90 μm diameter range, which some would argue present as a gradational phenotype from Quinqueloculina seminulum to Triloculina oblonga, or some consider juveniles of larger miliolids. In wild populations, Kaushik et al.64 observed that juvenile Quinqueloculina commonly have a triloculine chamber arrangement like the genus Triloculina. As such, researcher bias in classifying smaller miliolid foraminifera based on morphology alone is possible. However, these smaller miliolids most likely reflect a shared response to environmental forcing, so grouping these taxa (i.e., taxonomic units) should both (i) preserve environmental information and (ii) boost the signal-to-noise ratio for any environmental changes. The final combined database has 31 taxonomic units (observations) represented across 138 stratigraphic levels (samples). Charophyte remains were counted in FRSH-C3 at 1 cm intervals spanning the entire core length. First, separate sediment subsamples of 2.5 cm3 were washed over a >125 µm mesh sieve. The resultant residue was transferred to aluminum drying trays that were desiccated at 80 °C for 12 h prior to counting.

Numerical analysis and WBI calculation

Foraminiferal raw counts in the final data matrix (FRSH-C3 + FRSH-C2: 31 observations × 138 samples) were first Hellinger-transformed for cluster, multivariate, and correlation analysis (vegan package version 2.6-465: decostand function). Stratigraphically-unconstrained Q-mode cluster analysis was completed to identify groups of samples that reflect similar foraminiferal community structure, and therefore similar environmental conditions, regardless of time. Q-mode cluster analysis was completed using Bray–Curtis Dissimilarity [vegan package: vegdist function] and plotted into a dendrogram using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic Mean [UPGMA, base R package: hclust function]. Next, a DCA was performed on the Hellinger-transformed final data matrix [vegan package: decorana function] to further investigate the species response to an ecological gradient. DCA Axis 1 explained 46.8% of the variance in the data matrix, with DCA Axis 2 explaining a further 27.2% of the variance. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and associated p values were calculated [ggplot package, stat_cor function] to evaluate the strength of the relationship between the WBI vs. DCA 1, bulk organic matter vs. DCA 1, and the WBI vs. bulk organic matter (Fig. S8).

Samples generally scored a higher DCA 1 value if they had higher proportions (i.e., relative abundance) of the following 6 species: A. beccarii, C. gunteri, C. poeyanum, P. anderseni, P. davescottensis, and T. aguayoi. To calculate the WBI, the relative abundance (Fi) of these 6 stress-tolerant taxonomic units in each sample was first calculated by Fi = Ci/Ni, where Ci is the count for an individual taxonomic unit and Ni is the total census in each sample. The WBI was calculated for each sample by WBIi = Fi (A. beccarii) + Fi (C. gunteri) + Fi (C. poeyanum) + Fi (P. anderseni) + Fi (P. davescottensis) + Fi (T. aguayoi).

Stable isotopic analysis

Stable isotopic analysis of foraminiferal carbonate (on miliolid tests and WBI spp. Ammonia beccarii and C. poeyanum tests) was performed using a Kiel IV Carbonate Device coupled to a Thermo MAT253+ Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer housed at the University of Arizona’s Paleo² Lab. The data are reported in delta notation relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite scale (‰, VPDB), where the stable isotopic composition of oxygen is δ18O = [(18O/16Osample) / (18O/16O standard)] −1 and multiplied by 1000 to give units in permille scaled to a reference (Fig. S12); the same equation is used for δ13C but with 13C/12C. IAEA-603 was analyzed (n = 16) as an external standard, and the 1σ precision was 0.03‰ for δ¹³C and 0.05‰ for δ18O, which is consistent with the long-term precision of this setup (1σ δ¹³C = ± 0.05 ‰; 1σ δ¹⁸O = ± 0.07; n > 2500). We used 4 to 5 individual tests for each stable isotopic measurement within the sampled intervals for Ammonia, whereas >10 tests were used for the miliolid and Cribroelphidium species.

Data availability

All data is available online at the National Centers for Environmental Information World Data Service for Paleoclimatology (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/study/39723).

References

Zhuravleva, A., Bauch, H. A., Mohtadi, M., Fahl, K. & Kienast, M. Caribbean salinity anomalies contributed to variable North Atlantic circulation and climate during the Common Era. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg2639 (2023).

Martinez, C. J., Goddard, L., Kushnir, Y. & Ting, M. Seasonal climatology and dynamical mechanisms of rainfall in the Caribbean. Clim. Dyn. 53, 825–846 (2019).

Jury, M., Malmgren, B. A. & Winter, A. Subregional precipitation climate of the Caribbean and relationships with ENSO and NAO. J. Geophys. Res. 112, 11 (2007).

Bhattacharya, T., Chiang, J. C. H. & Cheng, W. Ocean-atmosphere dynamics linked to 800–1050 CE drying in mesoamerica. Quat. Sci. Rev. 169, 263–277 (2017).

Thirumalai, K. et al. Pronounced centennial-scale Atlantic Ocean climate variability correlated with Western Hemisphere hydroclimate. Nat. Commun. 9, 392 (2018).

Richey, J. N., Poore, R. Z., Flower, B. P., Quinn, T. M. & Hollander, D. J. Regionally coherent Little Ice Age cooling in the Atlantic Warm Pool. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L21703 (2009).

Wurtzel, J. B. et al. Mechanisms of southern Caribbean SST variability over the last two millenia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5954–5958 (2013).

Gregory, B. R. B., Peros, M., Reinhardt, E. G. & Donnelly, J. P. Middle-late Holocene Caribbean aridity inferred from foraminifera and elemental data in sediment cores from two Cuban lagoons. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 426, 229–241 (2015).

Fensterer, C. et al. Millennial-scale climate variability during the last 12.5 ka recorded in a Caribbean speleothem. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 361, 143–151 (2013).

Tamalavage, A. E. et al. Plant wax evidence for precipitation and vegetation change from a coastal sinkhole lake in the Bahamas spanning the last 3000 years. Org. Geochem. 150, 104120 (2020).

Li, W., Li, L., Ting, M. & Liu, Y. Intensification of Northern Hemisphere subtropical highs in a warming climate. Nat. Geosci. 5, 830–834 (2012).

Weinkle, J. et al. Normalized hurricane damage in the continental United States 1900–2017. Nat. Sustain. 1, 808–813 (2018).

Cook, B. I., Smerdon, J. E., Seager, R. & Coats, S. Global warming and 21st century drying. Clim. Dyn. 43, 2607–2627 (2014).

Herrera, D. & Ault, T. Insights from a new high-resolution drought atlas for the Caribbean spanning 1950 to 2016. J. Clim. 35, 1569–1578 (2017).

Zhang, M., Chen, X., Kumar, M., Marani, M. & Goralczyk, M. Hurricanes and tropical storms: a necessary evil to ensure water supply?. Hydrol. Process. 31, 4414–4428 (2017).

Vosper, E. L., Mitchell, D. M. & Emanuel, K. Extreme hurricane rainfall affecting the Caribbean mitigated by the paris agreement goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104053 (2020).

Rodysill, J. R. et al. Historically unprecedented Northern Gulf of Mexico hurricane activity from 650 to 1250 CE. Sci. Rep. 10, 19092 (2020).

Winkler, T. S., et al. More frequent hurricane passage across the Bahamian Archipelago during the Little Ice Age. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 38, e2023PA004623 (2023).

Donnelly, J. P. et al. Climate forcing of unprecedented intense-hurricane activity in the last 2,000 years. Earth’s. Future 3, 49–65 (2015).

Whitaker, F. F. & Smart, P. L. Hydrogeology of the Bahamian archipelago. in Geology and Hydrogeology of Carbonate Islands. (eds Vacher H. L., Quinn T. M.) 183–216 (Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1997).

Cant, R. V. & Weech, P. S. A review of the factors affecting the development of Ghyben-Hertzberg lenses in the Bahamas. J. Hydrol. 84, 333–343 (1986).

Moosdorf, N., Stieglitz, T., Waska, H., Dürr, H. H. & Hartmann, J. Submarine groundwater discharge from tropical islands: a review. Groundwater 20, 53–67 (2015).

Moore, W. S. The subterranean estuary: a reaction zone of ground water and sea water. Mar. Chem. 65, 111–125 (1999).

Oehler, T. et al. Seasonal variability of land-ocean groundwater nutrient fluxes from a tropical karstic region (southern Java, Indonesia). J. Hydrol. 565, 662–671 (2018).

Miller, D. C. & Ullman, W. J. Ecological consequences of ground water discharge to Delaware Bay, United States. Groundwater 42, 959–970 (2006).

Dale, R. K. & Miller, D. C. Spatial and temporal patterns of salinity and temperature at an intertidal groundwater seep. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 72, 283–298 (2007).

Encarnação, J. et al. The influence of submarine groundwater discharges on subtidal meiofauna assemblages in south Portugal (Algarve). Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 130, 202–208 (2013).

Whitaker, F. F. & Smart, P. L. Geochemistry of meteoric diagenesis in carbonate islands of the northern Bahamas: 1. Evidence from field studies. Hydrol. Process. 21, 949–966 (2007).

Holding, S. & Allen, D. M. From days to decades: numerical modeling of freshwater response to climate change stressor on small low-lying islands. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 933–949 (2015).

Avila, L. A., Stewart, S. R., Berg, R. & Hagen, A. B. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report, Tropical Cyclone Report (Hurricane Dorian AL052019: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2020).

Gamble, D. W. Local-scale analysis of the Caribbean mid-summer dry spell on San Salvador, Bahamas. In: Proc. 14th symposium on the geology of the Bhamas and other carbonate regions (eds. Siewers F. D., Martin J. B.) 67–74.2010 (Gerace Research Centre, San Salvador, 2010).

Wang, C., Enfield, D. B., Lee, S.-K. & Landsea, C. W. Influences of the Atlantic Warm Pool on Western Hemisphere Summer Rainfall and Atlantic Hurricanes. J. Clim. 19, 3011–3028 (2006).

Wang, C. & Lee, S.-K. Atlantic warm pool, Caribbean low-level jet, and their potential impact on Atlantic hurricanes. Geophsy. Res. Lett. 34, L02703 (2007).

Khan, N. S. et al. Drivers of Holocene sea-level change in the Caribbean. Quat. Sci. Rev. 155, 13–36 (2017).

Little, S. et al. Unique habitat for Benthic Foraminifera in subtidal Blue Holes on carbonate platforms. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 794728 (2021).

Björnerås, C. et al. Inland blue holes of The Bahamas – chemistry and biology in a unique aquatic environment. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 194, 95–106 (2020).

Tamalavage, A. E. Developing Geochemical Evidence for Holocene Hydroclimate Variability in the Subtropical Western North Atlantic. PhD thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas (2021).

Torres-Talamante, O., Alcocer, J., Beddows, P. A., Escobar-Briones, E. & Lugo, A. The key role of the chemolimnion in meromictic cenotes of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Hydrobiologia 677, 107–127 (2011).

Reeder, S. L. & Rankey, E. C. A tale of two storms: an integrated field, remote sensing and modeling study examining the impact of hurricans Frances and Jeanne on carbonate systems, Bahamas. in Perspectives in Carboante Geology: A tribute to the career of Robert Nathan Ginsberg (eds Swart P. K., Eberly G. P., McKenzie J. A.) 75–90 (Wiley Blackwell, 2012).

Perkins, R. D. & Enos, P. Hurricane Betsy in the Florida-Bahama Area: geologic effects and comparison with hurricane Donna. J. Geol. 76, 710–717 (1968).

Quej, V. H., Almorox, J., Arnaldo, J. A. & Moratiel, R. Evaluation of temperature-based methods for the estimation of reference evapotranspiration in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. J. Hydrol. Eng. 24, 0501029 (2019).

Linacre, E. T. A simple formula for estimating evaporation rates in various climates, using temperature data alone. Agr. Meteorol. 18, 409–424 (1977).

Sullivan, R. et al. Hydroclimate dipole drives multi-centennial variability in the Western Tropical North Atlantic Margin during the middle and late Holocene. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004184 (2021).

Diz, P., Francés, G. & Rosón, G. Effects of contrasting upwelling–downwelling on benthic foraminiferal distribution in the Ría de Vigo (NW Spain). J. Mar. Syst. 60, 1–18 (2006).

van Hengstum, P. J., Reinhardt, E. G., Beddows, P. A., Huang, R. J. & Gabriel, J. J. Thecamoebians (testate amoebae) and foraminifera from three anchialine cenotes in Mexico: low salinity (1.5 - 4.5 psu) faunal transitions. J. Foram Res. 38, 305–317 (2008).

Verlaak, Z. R. F. & Collins, L. S. Environmental controls on the distribution of modern Benthic Foraminifera in the Florida Everglades and their use as paleoenvironmental indicators. J. Foram Res. 51, 182–209 (2021).

Sen Gupta, B. K., Turner, R. E. & Rabalais, N. N. Seasonal oxygen depletion in continental-shelf waters of Louisiana: historical record of benthic foraminifers. Geology 24, 227–230 (1996).

Vieten, R. et al. Northeastern Caribbean rainfall variability linked to solar and volcanic forcing. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 39, e2023PA004720 (2024).

Richey, J. N., Poore, R. Z., Flower, B. P. & Quinn, T. M. 1400 yr multiproxy record of climate varibility from the northern Gulf of Mexico. Geology 35, 423–426 (2007).

Moberg, A., Sonechkin, D. M., Holmgren, K., Datsenko, N. M. & Karlén, W. Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low- and high-resolution proxy data. Nature 433, 613–617 (2005).

Christiansen, B. & Ljungqvist, F. C. The extra-tropical Northern Hemisphere temperature in the last two millennia: reconstructions of low-frequency variability. Climate 8, 765–786 (2012).

Winkler, T. S. et al. Oceanic passage of hurricanes across Cay Sal Bank in The Bahamas over the last 530 years. Mar. Geol. 443, 106653 (2022).

Trouet, V., Harley, G. L. & Domínguez-Delmás, M. Shipwreck rates reveal Caribbean tropical cyclone response to past radiative forcing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3169–3174 (2016).

Campbell, J. D. et al. Generating projections for the Caribbean at 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 °C from a high-resolution ensemble. Atmosphere 12, 328 (2021).

Stephenson, T. S., Goodess, C. M., Haylock, M. R., Chen, A. A. & Taylor, M. A. Detecting inhomogeneities in Caribbean and adjacent Caribbean temperature data using sea-surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD009127 (2008).

Taylor, M. A., Enfield, D. B. & Chen, A. A. Influence of the tropical Atlantic versus the tropical Pacific on Caribbean rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JC001097 (2002).

Balaguru, K. et al. Increased U.S. coastal hurricane risk under climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf0259 (2023).

van Hengstum, P. J. et al. Holocene sedimentation in a blue hole surrounded by carbonate tidal flats in The Bahamas: autogenic versus allogenic processes. Mar. Geol. 419, 106051 (2020).

Blaauw, M. & Christen, A. Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process. Bay Anal. 6, 457–474 (2011).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Patterson, R. T. & Fishbein, E. Re-examination of the statistical methods used to determine the number of point counts needed for micropaleontological quantitative research. J. Paleontol. 63, 245–248 (1989).

Loeblich, A. R., Jr. & Tappan, H. Foraminiferal Genera and their Classification, Vol. 2 (Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, 1987).

Ahyong et al. World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS). (WoRMS Editorial Board, 2024).

Kaushik, T., Murugan, T. & Dagar, S. S. Morphological variation in the porcelaneous benthic foraminifer Quinqueloculina seminula (Linnaeus, 1758): Genotypes or Morphotypes? A detailed morphotaxonomic, molecular and ecological investigation. Mar. Micropaleontol. 150, 101748 (2019).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. (R package Version 3, 2013).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC Full Data Reanalysis Version 6.0 at 0.5°: Monthly Land-Surface Precipitation from Rain-Gauges built on GTS-based and Historic Data. NOAA; 2011.

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Lin, C.-Y., Ho, C.-R., Zheng, Q., Kuo, N.-J. & Chang, P. Warm pool variability and heat flux change in the global oceans. Glob. Planet Change 77, 26–33 (2011).

Waite, A. J., et al. Observational and model evidence for an important role for volcanic forcing driving atlantic multidecadal variability over the last 600 years. Geophsy. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089428 (2020).

Saenger, C., Cohen, A. L., Oppo, D. W., Halley, R. B. & Carilli, J. E. Surface-temperature trends and variability in the low-latitude North Atlantic since 1552. Nat. Geosci. 2, 492–495 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (EAR-1703087, EAR-1702946), conducted with permits issued to the PJvH from Bahamas Environment and Science and Technology Commission, technical support by A. Posey, and local support provided by Friends of the Environment, the Albury Family, and many Abaconians.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J.v.H. and J.P.D.: study design and secured funding; primary fieldwork: P.J.v.H., J.P.D., R.M.S., T.S.W., A.E.T., P.A.B., N.A.; P.J.v.H. and S.N.L.: micropaleontology and graphics design; P.J.v.H., T.S.W., A.E.T., S.N.L., R.M.S., P.A.B.: hydrography; N.A.: co-ordination of field work and local broader impacts; R.M.S., S.C., J.D., P.J.v.H.: processing re-analysis datasets and drafting Fig. 1; K.T.: isotopic analysis; P.F., N.A., A.E.T., and T.S.W.: regional paleoclimate and paleoecologic analysis, S.C.: climate model analysis, regional climate dynamics and Fig. 3; P.J.v.H.: final manuscript development and drafting, with editing provided by all.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Hengstum, P.J., Little, S.N., Sullivan, R.M. et al. Common Era time-transgressive forcing of Caribbean water balance. Commun Earth Environ 6, 954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02905-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02905-x