Abstract

The conversion of natural forests to agricultural land threatens soil biodiversity and ecosystem stability, but its integrated impacts on soil multitrophic communities remain poorly understood. Here, we examined the relationships between forest-to-agriculture conversion, soil multitrophic community diversity, and temporal stability along a 3000 km transect in the Yangtze River Basin. Forest conversion increased the α-diversity of copiotrophic bacteria, but decreased the α-diversity of mycorrhizal fungi, parasitic protists, and most nematode functional groups. Crucially, it consistently decreased β-diversity across all functional groups, homogenizing soil communities. This homogenization destabilized ecosystem productivity by impairing soil nitrogen cycling and weakening plant–soil feedbacks. While the loss of α-diversity was observed in certain groups, it was the decline in β-diversity, or spatial variation, that emerged as the primary driver of reduced ecosystem stability. Our findings challenge conventional conservation paradigms by demonstrating that preserving ecosystem stability requires prioritizing β-diversity through sustainable agriculture and habitat protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil biota, which account for 59% of terrestrial biodiversity, encompass bacteria, fungi, protists, and nematodes, forming the foundation of ecosystem processes through nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and plant-soil interactions1,2,3. These soil organisms are critical for maintaining ecosystem stability4,5, particularly under anthropogenic pressures such as forest conversion. Forest conversion is a major global change factor that poses significant threats to soil biodiversity, creating a fragmented and inhospitable environment for many species or taxa6,7,8. This process, which replaces natural forest ecosystems with human-dominated land uses (such as agricultural systems), disrupts soil habitats, alters resource availability, and shifts microbial community composition, often leading to declines in soil organic carbon and total nitrogen9,10. Agricultural expansion homogenizes soil conditions, reducing niche diversity and favoring disturbance-tolerant taxa11,12. For instance, a global survey revealed that anthropogenic land use significantly decreased the diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi but increased the diversity of both bacterial and fungal pathogens10. A European study demonstrated higher α-diversity of soil protists in agricultural land compared to forest land13. Furthermore, research in northeastern China found that land-use change significantly altered the soil nematode community, specifically reducing the relative abundance of plant parasites and predators14. These divergent responses across trophic levels to forest conversion underscore the critical need to elucidate how such conversion affects biodiversity at multiple trophic levels and their ecological linkages, especially in ecosystems experiencing intense anthropogenic pressure. However, most studies have focused predominantly on soil biota at a single trophic level10,13,14,15, largely neglecting the interactions across multi-trophic levels. Therefore, the extent to which pressures from forest conversion differentially impact functional groups (FGs) within soil multitrophic communities, and the implications of these impacts for ecosystem stability, remain critical knowledge gaps.

Previous research has revealed that biodiversity plays a key role in promoting stability in ecosystems16,17,18,19. The relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem stability is underpinned by complementary mechanisms operating across spatial and trophic scales16,20,21. At the local scale (α-diversity), species richness enhances temporal stability through functional redundancy and compensatory dynamics, where diverse communities buffer against environmental fluctuations17,18,19. Generally, higher α-diversity is linked to increased temporal stability, possibly because diverse communities contain more stable species22,23,24. For example, oligotrophic microbes like Actinobacteria persist under resource scarcity, while copiotrophic Proteobacteria rapidly exploit nutrient pulses, collectively stabilizing biogeochemical cycles25,26. At regional scales (β-diversity), spatial asynchrony in community composition ensures that ecosystem functions are maintained even if local communities fluctuate, a phenomenon termed “spatial insurance”16,18,20. Cross-trophic interactions further stabilize ecosystems; fungal-bacterial networks, for instance, enhance stress resistance through metabolic cooperation27,28. However, these mechanisms are sensitive to anthropogenic disturbances19,29. Forest conversion simplifies soil food webs by reducing keystone taxa (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi) and disrupting trophic cascades28,30,31. Despite advances, most studies focus on single trophic levels, neglecting how multi-trophic α- and β-diversity jointly mediate ecosystem responses to anthropogenic stressors.

Ecosystem temporal stability is an important concept that quantifies the long-term invariability of ecosystem properties in both plant and soil microbial systems. Temporal stability reflects the long-term buffering capacity, driven by asynchronous species responses and spatial heterogeneity32,33. First, higher species diversity tends to increase temporal stability, and inter-species differences lead to different responses that exhibit inter-species asynchrony22,23,24,34. Second, the composition of the community is closely linked to temporal stability, species differences among local communities can promote the spatial asynchrony of community dynamics, leading to functional complementarity and producing a spatial insurance effect, thus stabilizing ecosystem function19,24,35,36. Soil FGs exhibit distinct roles in stabilizing ecosystems: saprotrophic fungi enhance temporal stability by sustaining decomposition under fluctuating conditions, whereas bacterial nutrient cyclers improve drought resistance via metabolic plasticity37,38. Fungal diversity positively correlates with temporal stability, while plant pathogens show negative associations37. Nematode α-diversity strengthens ecosystem temporal stability, but β-diversity effects are substrate-dependent21,39. Interactions within soil food webs, mediated by bottom-up/top-down effects40, highlight disproportionate anthropogenic impacts on higher trophic levels29,31. However, the role of β-diversity in stabilizing ecosystems at regional scales via spatial asynchrony or functional redundancy is rarely linked to multi-trophic soil organisms18,20. Current frameworks often isolate bacteria, fungi, protists, and nematodes, obscuring their synergies and hindering predictions of how soil biodiversity loss under the conversion of natural forest to agricultural land impacts ecosystem temporal stability.

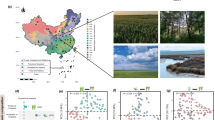

The Yangtze River, the longest river in China and the third longest in the world, is home to a basin that covers nearly 20% of mainland China and supports 584 million people. The Yangtze River is renowned for its biodiversity, grain production, water conservation, and carbon sequestration41,42. Additionally, the Yangtze River spans 6380 km in distance, resulting in a wide range of climate and soil environmental gradients41,42. However, accelerating anthropogenic pressures now threaten the ecosystem stability of the Yangtze River. Forest conversion, driven by human activities, is a common land-use change along the Yangtze River banks, leading to the replacement of natural forests with croplands or orchards to meet the increasing demand for food and wood products43,44. Agricultural expansion also has driven rapid forest fragmentation, degrading habitat connectivity45, leading to large-scale habitat homogenization46,47. Therefore, the Yangtze River provides a unique opportunity to study soil biodiversity and an ideal experimental platform to fill previous knowledge gaps. Our research focused on 20 paired sites along the Yangtze River, representing different types of ecosystems (natural forests and agricultural land) (Fig. 1a). By examining soil bacteria, fungi, protists, and nematode FGs across a 3000 km transect along the Yangtze River, we aimed to understand how their diversity influences ecosystem temporal stability. Two questions guide this work: (1) How does forest conversion exert effects on soil biodiversity and ecosystem temporal stability? (2) Which mechanisms, α-diversity-driven complementarity or β-diversity-driven asynchrony, dominate ecosystem temporal stability at regional scales? We hypothesize that forest conversion increases α-diversity but decreases β-diversity, causing fluctuations in ecosystem temporal stability (Fig. 1b). This study integrates a mechanistic understanding of the role of multi-trophic soil biodiversity in ecosystem temporal stability under human-modified environmental stressors at a regional scale.

a Locations of the 20 paired study sites along the east-west transect across the Yangtze River. The insect illustrates the sampling design at each site. b Conceptual framework outlining the hypothesized pathways through which forest conversion affects ecosystem temporal stability via the α- and β-diversity of soil biota functional groups (FGs). “+” and “-” denote positive and negative effects, respectively. Blue arrows represent the direct effects of forest conversion on soil biota FGs. Purple arrows represent the effects of α-diversity, and green arrows represent the effects of β-diversity on ecosystem stability. Arrow thickness indicates the relative strength of the hypothesized effect.

Results

Responses of soil abiotic attributes and diversity of soil biota

Forest conversion had a greater impact on soil abiotic attributes and diversity of soil biota along the Yangtze River (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Forest conversion decreased soil moisture, soil organic carbon (SOC), and total soil nitrogen (TSN), but increased soil pH and total soil phosphorus (TSP). Forest conversion had varying effects on α-diversity across different soil biota FGs (Fig. 2). Overall, soil bacterial α-diversity increased due to increases in α-diversity of soil C- and N-cycle bacteria. Overall, soil fungal α-diversity decreased due to declines in α-diversity of mycorrhizal fungi and soil saprotrophic fungi, despite increases in plant pathogenic fungi and litter-wood saprotrophic fungi (Fig. 2). Forest conversion also decreased α-diversity of parasitic protists but increased α-diversity of phototrophic protists and plant pathogenic protists (Fig. 2). Overall nematode α-diversity decreased due to declines in α-diversity of fungal-feeding nematodes, bacterial-feeding nematodes, and omnivores + carnivores, despite faint increases in the α-diversity of plant-feeding nematodes (Fig. 2).

Bubble maps show the distribution of biodiversity metrics across natural forests (red) and agricultural lands (blue). Bubble size is proportional to the value of the diversity metric. Significance of forest conversion effects was assessed by linear mixed-effects models (ns, #, *, **, and *** indicate P > 0.1, ≤ 0.1, ≤ 0.05, ≤ 0.01, and ≤ 0.001, respectively). “+”, “−”, and “ns” denote a significant positive, significant negative, or non-significant effect of forest conversion, respectively.

The linear mixed effects model (LMM) further revealed that forest conversion significantly reduced the β-diversity across multiple soil biota groups, including overall bacteria, C-cycle bacteria, N-cycle bacteria, overall fungi (all fungal FGs except mycorrhizal fungi), overall protists, phototrophic protists, plant pathogenic protists, predatory protists, overall nematodes, bacterial-feeding nematodes, and plant-feeding nematodes (Fig. 2). Moreover, forest conversion simplified the associations among soil biota FGs, resulting in co-occurrence networks with fewer nodes, fewer edges, and lower connectivity density in agricultural lands compared to natural forests (Fig. 3). Consequently, these structural changes contributed to a significant decrease in overall network stability (Fig. 3).

Co-occurrence networks of soil biota functional groups in (a) natural forests and (b) agricultural lands. Connections represent strong (Spearman’s |r| > 0.5) and significant (P ≤ 0.05) correlations. Node size is proportional to the number of connections (degree). c Network robustness, measured as the proportion of taxa remaining after random node removal. (d–f) Effects of forest conversion (FC) on network stability, positive cohesion, and negative cohesion. Significance is indicated by asterisks (linear mixed-effects models; ***P ≤ 0.001). Red and blue violin plots show the data distribution for natural forests and agricultural lands, respectively; horizontal lines and dots within plots represent the median and mean values.

Determinations for diversity of soil biota FGs

Forest conversion led to increases in α-diversity of bacterial FGs, plant pathogenic fungi, and litter + wood saprotrophic fungi, which were mainly associated with higher soil pH (Fig. 4). On the other hand, decreases in α-diversity of mycorrhizal fungi and soil saprotrophic fungi were linked to increases in TSP (Fig. 4). The increases in α-diversity of phototrophic protists and plant pathogenic protists were related to increases in TSP and pH, as well as decreases in TSN (Fig. 4). Conversely, decreases in α-diversity of parasitic protists were associated with reductions in TSN (Fig. 4). Decreases in β-diversity of bacterial and protist FGs were mainly driven by increases in TSP (Fig. 4). Additionally, forest conversion resulted in reduced β-diversity of fungal FGs, which was primarily linked to higher TSP and pH (Fig. 4).

Responses and determination pathways for ecosystem temporal stability

LMM analysis revealed that forest conversion significantly reduced soil C mineralization rate (Soil Cmin), soil N mineralization rate (Soil Nmin), β−1,4-N-acetyl-glucosaminidase (S-NAG), and acid phosphatase (S-ACP) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Partial correlation analysis revealed that α-diversity of phototrophic protists and β-diversity of phototrophic protists and plant pathogenic protists were positively correlated with four soil functions (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The LMM clearly showed that forest conversion decreased ecosystem temporal stability (due to the decline in mean NDVI and the increase in SD of NDVI) (Fig. 5). Linear regression analysis found that the four soil functions were all positively correlated with ecosystem temporal stability and mean NDVI, and negatively correlated with SD of NDVI (Fig. 5). The regression analysis showed that the relationships between α-diversity or β-diversity of soil FGs and ecosystem temporal stability were significantly different between natural forests and agricultural lands (Supplementary Figs. 6–8). The regression analysis also showed that forest conversion strongly altered the relationships between α-diversity or β-diversity of soil FGs and temporal stability, mean, or SD of NDVI (Supplementary Figs. 6–8).

a Effects of forest conversion (FC) on the temporal stability, mean, and interannual variability (SD) of the NDVI. Significance is indicated by asterisks (linear mixed-effects models; ***P ≤ 0.001). Red and blue violin plots show the data distribution for natural forests and agricultural lands, respectively; horizontal lines and dots represent the median and mean. b Relationships between key soil ecosystem functions (Cmin soil C mineralization rate, Nmin soil N mineralization rate, S-NAG β−1,4-N-acetyl-glucosaminidase, S-ACP acid phosphatase) and NDVI-based stability metrics. Solid lines indicate significant relationships (P ≤ 0.05).

PiecewiseSEM revealed that the decrease in ecosystem temporal stability due to forest conversion was positively associated with the α-diversity of protistan FGs, β-diversity of fungal and nematode FGs, soil fertility, and soil functions (Fig. 6a). Variance decomposition analysis showed that, at the regional scale, soil biota FG β-diversity contributed more to ecosystem temporal stability than did α-diversity (Supplementary Figs. 9–10). In addition, we found that the β-diversity of fungal, protist, and nematode FGs indirectly affects ecosystem temporal stability by influencing soil Nmin and S-NAG (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 11). Partial correlation analysis revealed that ecosystem temporal stability was positively related to the α-diversity of soil saprotrophic fungi and parasitic protists, as well as the β-diversity of mycorrhizal fungi, phototrophic protists, and fungal-feeding nematodes (Fig. 6b). Additionally, both ecosystem temporal stability and mean NDVI were positively correlated with TIN and TSN, while negatively correlated with SOC and TSP (Supplementary Fig. 12).

a Piecewise structural equation model (SEM) illustrating the direct and indirect effects of climate and forest conversion (FC) on ecosystem temporal stability, mediated by soil biota attributes, plant α-diversity, soil environment, and soil fertility. BaF bacterial FGs, FuF fungal FGs, PrF protist FGs, NeF nematode FGs, α α−diversity β β−diversity. Numbers adjacent to arrows are standardized path coefficients (P ≤ 0.05). R² values represent the proportion of variance explained for endogenous variables. For graphical clarity, correlations among the α-diversity and β-diversity of different soil biota groups are represented within grouped boxes. b Partial correlation between the α-diversity and β-diversity of soil biota functional groups and ecosystem temporal stability. Significance levels are indicated (*, **, *** for P ≤ 0.05, ≤ 0.01, and ≤ 0.001, respectively).

Discussion

The conversion of natural forests to agricultural lands in the Yangtze River Basin elicited divergent responses in the α-diversity of soil biota FGs, reflecting their distinct ecological strategies and environmental sensitivities. For bacteria, increased α-diversity in agricultural lands aligns with their copiotrophic lifestyles, which thrive under elevated soil pH and TSP from fertilizer inputs (Figs. 2 and 4). Enhanced resource availability likely favored fast-growing taxa such as soil C- and N-cycle bacteria, consistent with agricultural homogenization of soil conditions10,48,49. In contrast, soil fungal FGs exhibited pronounced declines in α-diversity, particularly mycorrhizal and soil saprotrophic fungi (Fig. 2). These losses were tightly linked to reduced plant diversity and organic inputs (SOC and TSN) post-conversion, underscoring their dependence on complex plant-derived substrates4,50,51. Conversely, ruderal fungal groups (such as plant pathogens and litter-wood saprotrophs) proliferated in agricultural soils (Fig. 2), likely due to crop residue accumulation and simplified plant communities48,50. Soil protist responses were nuanced: phototrophic and pathogenic protists increased with monoculture vulnerability, while parasitic protists declined due to host community simplification13,31,49. Forest conversion significantly reduced the nematode FGs α-diversity through dual pathways: tillage physically disrupts soil pores essential for nematode habitats52, while declining FGs α-diversity strongly correlates with elevated TSP. This correlation arises because C/P imbalance drives convergent organic matter decomposition pathways, thereby compressing ecological niches of nematode FGs and accelerating diversity loss53. Collectively, forest conversion amplified soil bacterial dominance while destabilizing soil fungal and nematode networks, highlighting trophic-level asymmetries in disturbance responses.

Forest conversion significantly reduced β-diversity (species turnover) across nearly all soil biota FGs, indicating pronounced biotic homogenization at regional scales (Fig. 2). This decline in β-diversity is critical, as it erodes spatial asynchrony across space that destabilizes ecosystem functions at landscape scales. Agricultural practices erased niche heterogeneity by standardizing soil pH, TSP, and plant communities, filtering for generalist taxa, and eroding spatial variability in community composition54,55,56. This homogenization was most pronounced in soil bacteria and fungi, whose β-diversity declines correlated with TSP enrichment (Fig. 4), reflecting agricultural prioritization of nutrient-rich, disturbance-adapted taxa21,37,57. Concomitant losses in functional redundancy likely increase vulnerability to perturbations, as fewer taxa remain capable of performing key processes if dominant groups fail17. Soil protist and nematode β-diversity losses further underscored the collapse of trophic complexity, as simplified food webs favored omnivorous or pathogenic groups over specialized predators or parasites39,58,59, reducing the portfolio of responses across space (spatial asynchrony) and diminishing buffering capacity via functional redundancy within trophic levels. Network analyses revealed weakened associations among soil FGs in agricultural soils (Fig. 3), likely due to competitive exclusion under resource scarcity60,61. In contrast, natural forests exhibited high niche dimensionality supporting synergistic interactions (e.g., fungal-bacterial mutualisms), fostering both strong spatial asynchrony and high functional redundancy that stabilized communities27,28,60,61. Agricultural intensification disrupted these networks, favoring antagonistic or neutral relationships that undermine both asynchronous dynamics and redundant functions. These findings emphasize that β-diversity loss extends beyond taxonomic simplification to disrupt functional connectivity, with cascading implications for ecosystem resilience.

Forest conversion degraded temporal stability, mainly due to the reduction in β-diversity of soil biota FGs along with changes in soil abiotic variables. Agriculturally driven declines in SOC and TSN disrupted energy channels critical for saprotrophic fungi and bacterial-feeding nematodes, destabilizing decomposition and nutrient cycling21,37,62. The loss of litter-wood saprotrophic fungi, phototrophic protists, and plant pathogenic protists further impaired plant-soil feedback (Supplementary Fig. 9), reducing mean NDVI and amplifying productivity fluctuations28,30. This phenomenon primarily stems from reduced functional redundancy impairing soil nitrogen cycling. Our study demonstrates positive correlations of soil Nmin and S-NAG activity with temporal stability (Supplementary Fig. 11). Specifically, homogenization of litter-wood saprotrophic fungal communities compromises their capacity to decompose complex organic matter, thereby limiting substrate availability and suppressing soil Nmin4,63. Concurrently, diminished abundance of phototrophic protists reduces labile carbon inputs, constraining microbial metabolic activity4. Homogenization of plant pathogenic protists may further alter plant-soil feedback, indirectly inhibiting microbial function through decreased root exudation4. In addition, the decrease in fungal diversity directly inhibited the production and activity of S-NAG, because this enzyme is mainly synthesized by fungi to degrade chitin, while the functional redundancy caused by the homogenization of fungal FGs was lost, and the remaining groups could not compensate for chitin decomposition function63,64. Notably, soil pH increases under agriculture disrupted cross-trophic interactions, favoring stress-tolerant but functionally inflexible taxa21,57. While natural forests leveraged spatial asynchrony (high β-diversity) to stabilize regional NDVI20,22, agricultural homogenization synchronized ecosystem responses, elevating vulnerability to droughts or nutrient pulses34. These findings align with theory predicting that biodiversity loss erodes both local (α-driven) and regional (β-driven) stability mechanisms17,18,19. Forest conversion disrupts ecosystem temporal stability by eroding both local compensatory mechanisms (via α-diversity loss) and regional insurance effects (via β-diversity homogenization), underscoring the necessity of conserving landscape-scale biodiversity to buffer anthropogenic and climatic perturbations.

Recent studies find that across medium-to-large spatial scales, β-diversity appears to be a better predictor of ecosystem stability than α-diversity65. Our results in the Yangtze River underscore that the β-diversity of soil biota FGs, rather than α-diversity, is the cornerstone of ecosystem temporal stability at regional scales. Previous studies have found that α-diversity can enhance ecosystem functions, thereby promoting the coexistence of local species21. However, α-diversity mainly functions at the local scale and has a weak impact on stability at the regional scale65. Spatial turnover in soil fungal, protistan, and nematode FGs stabilized NDVI by decoupling local productivity fluctuations, namely through a spatial insurance effect16,18,20. High β-diversity in soil functional groups (indicative of community heterogeneity) can stabilize ecosystem productivity via the spatial insurance effect by enhancing spatial heterogeneity66. For example, from saprotrophic fungi that decompose organic matter to phototrophic protists that influence nutrients via plant-soil feedbacks, these groups perform unique functions in maintaining various ecosystem processes, thereby buffering productivity fluctuations caused by forest conversion. Conversely, agricultural homogenization collapsed β-diversity of soil biota FGs, synchronizing functional responses and amplifying systemic risk67,68. For instance, the loss of spatially segregated soil saprotrophic fungi reduced soil organic matter breakdown efficiency under variable moisture, while diminished soil protistan β-diversity limited predation-driven nutrient pulses27,28,37. Crucially, network disassembly in agricultural soils disrupted cross-FG synergies (e.g., fungal-bacterial co-metabolism), eroding resistance despite stable α-diversity31,69. Overall, our study revealed that the reduction of soil biota β-diversity due to forest conversion led to a decline in ecosystem temporal stability at the regional level. This suggests that conservation efforts should prioritize landscape-scale heterogeneity to maintain β-diversity and its stabilizing effects, rather than focusing solely on local species richness. Despite its effectiveness in monitoring surface vegetation dynamics and its role as our primary metric for ecosystem temporal stability, NDVI does not account for critical below-ground processes like soil nutrient cycling and microbial activity. Consequently, our interpretation of stability may be limited. Future investigations should seek a more holistic understanding by integrating metrics such as soil nutrient status and functional redundancy.

Conclusion

Our research highlights the critical role of soil biodiversity in sustaining ecosystem temporal stability across the Yangtze River Basin, where the conversion of forests to agricultural land disrupts plant diversity, soil conditions, and fertility, triggering cascading effects on soil biota FGs. While agricultural practices increase the α-diversity of certain resource-acquisitive microbial FGs, they simultaneously drive biotic homogenization by eroding β-diversity across multiple trophic levels, an effect particularly pronounced in fungi and protists. Crucially, the loss of soil biotic β-diversity, rather than changes in α-diversity, emerged as the primary predictor of reduced ecosystem temporal stability, emphasizing the need to prioritize landscape-scale heterogeneity over local richness (α-diversity) in conservation strategies. To mitigate these impacts, it is imperative to preserve natural forests and adopt sustainable agroecological practices to enhance cross-trophic interactions and spatial insurance mechanisms. These measures include diversifying cropping systems, integrating habitat corridors, and minimizing soil tillage to enhance cross-trophic interactions and spatial insurance mechanisms. Land-use policies must prioritize landscape connectivity and functional β-diversity to buffer ecosystems against global change stressors and ensure the provision of resilient ecosystem services. Consequently, policies must aim to safeguard landscape-scale soil biotic β-diversity through the conservation of natural forests and the promotion of sustainable agroecological practices to counteract biotic homogenization and thereby secure cross-trophic ecosystem functionality. Furthermore, while our findings underscore the importance of β-diversity, the scope of our stability assessment is still limited.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

We conducted a regional transect study along the Yangtze River, spanning from 103°66’E to 119°68’E and 28°25’N to 32°23’N, covering eight provinces (Yunnan, Sichuan, Chongqing, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, and Jiangsu). The area has a subtropical monsoon climate with hot summers and warm winters, with an average temperature of 14–20 °C and annual precipitation ranging from 800 to 1600 mm. The second half of the year typically receives 70% of the total precipitation. The main soil types in the Yangtze River Basin are Ultisols, Inceptisols, and Alfisols. For our study, we selected paired forest conversion sites: undisturbed natural forest and anthropogenically disturbed agricultural land (including croplands and orchards) along the south and north banks of the Yangtze River. We established a total of 20 paired locations (south and north banks), each location included one paired forest conversion site (natural forest and agricultural land), and a total of 80 sampling sites (100 m × 100 m) along the middle and lower Yangtze River (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). More information can be found in ref. 43.

Sampling of plants and soils

In each sampling site, three replicated sampling plots (10 m × 10 m) were randomly selected for aboveground vegetation surveys and soil samplings. The vegetation survey was conducted to assess forest types, tree abundance, and tree and shrub diversity. The number and types of trees were recorded during field surveys. Soil cores (2 cm in diameter, 0–10 cm deep) were collected using a five-point sampling method in November and December 202070. The cores were combined to create a single sample, and visible plant roots and stones were removed using a 2 mm mesh sieve. The soil samples were transported to the laboratory in a cooler with ice packs and divided into two portions. One portion was air-dried for analysis of soil pH (measured by potentiometry), soil organic carbon (SOC, measured by potassium dichromate oxidation method), total soil nitrogen (TSN, measured by micro-Kjeldahl digestion method), and total soil phosphorus (TSP, measured by strong acid fusion method). The other portion was kept fresh at room temperature for assessment of soil moisture (SM, measured by gravimetric method), soil inorganic nitrogen (TIN: NH₄⁺-N and NO₃⁻-N, measured by continuous flow analysis method), and communities of soil bacteria, fungi, protists, and nematodes.

Measuring of FGs of soil biota

Soil bacterial and fungal community composition was assessed using 16S and ITS amplicon sequencing, and soil nematode and protist community composition were assessed using 18S amplicon sequencing. DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of soil using the FastDNA® Spin Kit from MP Biomedicals. The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 338 F (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG) and 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT)71. The fungal ITS1 region was amplified using the primers ITS1F (CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA) and ITS2R (GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC)71. The 18S region of the protists was amplified using primers 616F (TTAAARVGYTCGTAGTYG) and 1132R (CCGTCAATTHCTTYAART)72. The 18S region of nematodes was amplified using primers NF1F (GGTGGTGCATGGCCGTTCTTAGTT) and 18Sr2bR (TACAAAGGGCAGGGACGTAAT)73. The PCR products were visualized using a 2% agarose gel and then purified using a DNA Gel Extraction Kit. The purified amplicons were sequenced using a 2 × 300 bp paired-end Illumina MiSeq platform. The Fastq files of sequencing were analyzed using Qiime2 for clustering and identification. Zero-radius operational taxonomic units (ZOTUs) were clustered with a 100% similarity threshold71. The taxonomy of each sequence was assigned using the RDP Classifier algorithm. The primers 338F-806R, ITS1-ITS2, 616F-1132R, and NF1F-18Sr2bR were aligned against the Silva 138, Unite 8.2, and PR2 4.14.0 databases, respectively. Subsequently, taxonomic assignment of representative sequences for bacteria, fungi, protists, and nematodes was performed using a Naïve Bayesian classifier against the calibrated databases.

The soil bacterial ZOTUs were classified into two FGs based on their role in nutrient cycling: C-cycle bacteria and N-cycle bacteria using the FAPROTAX database74. The soil fungal ZOTUs were classified into four FGs: mycorrhizal fungi, plant pathogenic fungi, soil saprotrophic fungi, and litter-wood saprotrophic fungi, using the FungalTraits database75. The soil protist ZOTUs were classified into four FGs based on their putative nutrient-uptake mode76,77: parasitic protists, predatory protists, phototrophic protists, and plant pathogenic protists. For protist FGs, their genus names were used to compare with relevant literature to determine their feeding habits31. The soil nematode ZOTUs were classified into four FGs based on their feeding habits: plant-feeding, bacterial-feeding, fungal-feeding, and omnivorous + carnivorous nematodes78. All pictures of soil biotic FGs in the figure were obtained using two websites (https://www.vecteezy.com and https://ian.umces.edu/media-library). Species richness of each FG was measured as α-diversity in each 10 m × 10 m sample plot. Total species richness across three replicated plots was defined as γ-diversity. β-diversity was calculated as the species turnover among the three plots within each sample site, with the formula β = γ/αmean-121,79, where αmean is the average α-diversity value across three replicated plots.

Ecosystem functions

We quantified soil C mineralization rate (Soil Cmin), soil N mineralization rate (Soil Nmin), β−1,4-N-acetyl-glucosaminidase (S-NAG), and acid phosphatase (S-ACP) enzymes, which are essential ecosystem functions involving soil C, N, and P cycling processes30,63. Soil Cmin and Nmin were determined by the aerobic incubation method80. Twenty gram of fresh soil samples were placed in 250 ml brown glass bottles and incubated for 21 days under dark conditions with a constant temperature of 25 °C and a constant humidity of 60%. The carbon dioxide released from the soil was measured using a gas chromatograph (Agilent GC7890B) on days1,2,3,7,10,14, and20 of incubation, respectively. The average carbon dioxide release during the entire incubation period was taken as the soil Cmin. 20 g of fresh soil before and after incubation were weighed separately for extracting soil inorganic nitrogen (NH₄⁺-N and NO₃⁻-N). The extraction was performed using 100 ml of 2 mol L⁻¹ KCl solution, and the determination was carried out with a Kjeltec analyzer. The difference in soil inorganic nitrogen content before and after incubation was regarded as the soil Nmin. To assess the potential activities of S-NAG and S-ACP enzymes, a 0.1 g sample of air-dried soil was homogenized in 90 ml of 50 mmol/L sodium acetate buffer. Two hundred microliters aliquots of the supernatant were added to a 96-well black microplate, and the absorbance was measured with an enzyme-labeled instrument (from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

The ecosystem temporal stability was determined by the mean-to-SD ratio of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) during 2001 to 2020. The NDVI from the MOD13Q1 product with a spatial resolution of 30 × 30 m for the years 2001–2020 was used as an indicator of ecosystem function. NDVI data extraction was conducted using precise latitude and longitude coordinates to ensure accuracy, with the 30 × 30 m resolution being sufficient to encompass sampling plots (10 × 10 m). NDVI data for the annual growth period from 2001 to 2020 were analyzed to assess long-term ecosystem stability at a regional or global scale21.

Soil biological network stability analysis

To understand how forest conversion affects the soil biological FGs stability, we used the robustness and positive and negative cohesion of microbial networks to characterize the stability of soil microbial networks81,82. Robustness refers to randomly removing a certain proportion of nodes (species) to examine the impact on the remaining species82. Positive cohesion refers to the mutually beneficial relationships among microorganisms, whereas negative cohesion denotes competitive or inhibitory interactions among microbial populations81. We calculated positive and negative cohesion as:

Where \({C}_{j}^{{pos}}\) and \({C}_{j}^{{neg}}\) denote positive and negative cohesion, respectively. \({a}_{i}\) represents the abundance of species \(i\) in sample \(j\). The positive connectivity (\({\bar{r}}_{i,r > 0}\)) and negative connectivity \({\bar{r}}_{i,r < 0}\)) of species \(i\) are calculated as the mean of all its significant positive or negative correlations with all other species in the network. The ranges of negative cohesion and positive cohesion are [-1, 0] and [0, 1], respectively, where a larger magnitude indicates stronger correlations. The stability of microbial networks can be calculated through positive and negative cohesion81:

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). First, a linear mixed effects model (LMM) with plots as random effects was used to investigate the effects of forest conversion on soil abiotic properties, α- and β-diversity of soil biota FGs, and ecosystem temporal stability. The LMM was performed using the “lme4” package. Second, we used linear regression to explore the relationship between the diversity of soil biota FGs and ecosystem temporal stability in natural forests and agricultural lands. Third, partial correlation analysis was used to determine the relationships between the diversity of soil biota FGs, ecosystem temporal stability, variables related to climate, soil fertility, and soil environment. The partial correlation analysis was performed using the “ppcor” package. Fourth, a co-occurrence network was constructed to assess the impact of forest conversion on the diversity of soil biota FGs using the “igraph” package and visualized with the Gephi platform. Then, variance decomposition was used to assess the importance of soil biota FG α- and β-diversity for ecosystem temporal stability, utilizing the “relaimpo” packages. Finally, we examined the effects of forest conversion and climate on the diversity of soil biota FGs, and ecosystem stability via soil environment, soil fertility, and plant α-diversity through piecewise structural equation modeling utilizing the “piecewiseSEM”, “nlme”, and “lme4” packages. The initial model was simplified by removing pathways with non-significant regressions (P > 0.05).

Data availability

All data generated in this study, including raw sequencing Fastq files, have been deposited in the Zenodo repository83 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16938748).

Code availability

All analysis R code used to create the tables and figures have been deposited in the Zenodo repository83 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16938748).

References

Anthony, M. A., Bender, S. F. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Enumerating soil biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2304663120 (2023).

Orgiazzi, A., Bardgett, R. D. & Barrios, E. Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas (European Commission, Publications Office of the European Union, 2016).

Wall, D. H., Nielsen, U. N. & Six, J. Soil biodiversity and human health. Nature 528, 69–76 (2015).

Bardgett, R. D. & van der Putten, W. H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 515, 505–511 (2014).

Chen, D. et al. Effects of plant functional group loss on soil biota and net ecosystem exchange: a plant removal experiment in the Mongolian grassland. J. Ecol. 104, 734–743 (2016).

Barnes, A. D. et al. Consequences of tropical land use for multitrophic biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 5, 5351 (2014).

Cohen, M. J. et al. Do geographically isolated wetlands influence landscape functions?. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1978–1986 (2016).

Kadmon, R. & Pulliam, H. R. Island biogeography: effect of geographical isolation on species composition. Ecology 74, 977–981 (1993).

Fierer, N. & Jackson, R. B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 626–631 (2006).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Global homogenization of the structure and function in the soil microbiome of urban greenspaces. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg5809 (2021).

Liu, T. et al. Carbon-rich organic fertilizers to increase soil biodiversity: Evidence from a meta-analysis of nematode communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 232, 199–207 (2016).

Barberán, A. et al. Relating belowground microbial composition to the taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional trait distributions of trees in a tropical forest. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1397–1405 (2015).

Aslani, F. et al. Land use intensification homogenizes soil protist communities and alters their diversity across Europe. Soil Biol. Biochem. 195, 5351 (2024).

Pan, F. et al. Land use and temperature shape the beta diversity of soil nematodes across the Mollisol zone in northeast China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 373, 109132 (2024).

Wagg, C. et al. Diversity and asynchrony in soil microbial communities stabilizes ecosystem functioning. Elife 10, e62813 (2021).

Loreau, M. & de Mazancourt, C. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: a synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 16, 106–115 (2013).

Valencia, E. et al. Synchrony matters more than species richness in plant community stability at a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24345–24351 (2020).

Loreau, M. et al. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning: Current Knowledge and Future Challenges. Science 294, 804–808 (2001).

Craven, D. et al. Multiple facets of biodiversity drive the diversity–stability relationship. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1579–1587 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Biotic homogenization destabilizes ecosystem functioning by decreasing spatial asynchrony. Ecology 102, e03332 (2021).

Wu, L. et al. Soil biota diversity and plant diversity both contributed to ecosystem stability in grasslands. Ecol. Lett. 26, 858–868 (2023).

Sasaki, T., Lu, X., Hirota, M. & Bai, Y. Species asynchrony and response diversity determine multifunctional stability of natural grasslands. J. Ecol. 107, 1862–1875 (2019).

Yan, Y., Connolly, J., Liang, M. W., Jiang, L. & Wang, S. P. Mechanistic links between biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and stability in a multi-site grassland experiment. J. Ecol. 109, 3370–3378 (2020).

Loreau, M. & Hector, A. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412, 72–76 (2001).

Schimel, J. P. Life in dry soils: effects of drought on soil microbial communities and processes. In: Futuyma D. J. (ed). Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Systematics vol. 49, 409–432 (2018).

Bardgett, R. D. & Caruso, T. Soil microbial community responses to climate extremes: resistance, resilience and transitions to alternative states. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 375, 1794 (2020).

De Vries, F. T., Griffiths, R. I., Knight, C. G., Nicolitch, O. & Williams, A. Harnessing rhizosphere microbiomes for drought-resilient crop production. Science 368, 270 (2020).

Banerjee, S. et al. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. Isme J. 13, 1722–1736 (2019).

Wang, B. et al. Temporal asynchrony of plant and soil biota determines ecosystem multifunctional stability. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17483 (2024).

Wagg, C., Bender, S. F., Widmer, F. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5266–5270 (2014).

Xiong, W. et al. A global overview of the trophic structure within microbiomes across ecosystems. Environ. Int. 151, 106438 (2021).

Orwin, K. H. & Wardle, D. A. New indices for quantifying the resistance and resilience of soil biota to exogenous disturbances. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 1907–1912 (2004).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Soil microbial communities drive the resistance of ecosystem multifunctionality to global change in drylands across the globe. Ecol. Lett. 20, 1295–1305 (2017).

Xu, Q. et al. Consistently positive effect of species diversity on ecosystem, but not population, temporal stability. Ecol. Lett. 24, 2256–2266 (2021).

De Mazancourt, C. et al. Predicting ecosystem stability from community composition and biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 16, 617–625 (2013).

Xu, Q. N. et al. Nitrogen enrichment alters multiple dimensions of grassland functional stability via changing compositional stability. Ecol. Lett. 25, 2713–2725 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Phylotype diversity within soil fungal functional groups drives ecosystem stability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 900 (2022).

De Vries, F. T. et al. Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat. Commun. 9, 3033 (2018).

Gong, X. et al. Urbanization simplifies soil nematode communities and coincides with decreased ecosystem stability. Soil Biol. Biochem. 190, 109297 (2024).

Gessner, M. O. et al. Diversity meets decomposition. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 372–380 (2010).

Xu, X., Yang, G., Tan, Y., Liu, J. & Hu, H. Ecosystem services trade-offs and determinants in China’s Yangtze River Economic Belt from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 634, 1601–1614 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Gao, J., Fan, X., Lan, Y. & Zhao, M. Response of ecosystem services to socioeconomic development in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 72, 481–493 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Climate regulates the effect of land-use change on the diversity of soil microbial functional groups and soil multifunctionality. J. Appl. Ecol. 61, 2087–2099 (2024).

Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45 (2015).

Zhu, H., Wang, A., Wang, P., Hu, C. & Zhang, M. Spatiotemporal dynamics and response of land surface temperature and kernel normalized difference vegetation index in Yangtze River Economic Belt, China: multi-method analysis. Land 14, 598 (2025).

Shang, J., Zhang, W., Gao, Y., Li, Y. & Wu, H. Dam-induced flow alternations drive the regime shift towards a cyanobacteria-dominated microbiota state in the Yangtze River. Water Res. 244, 120527 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. Changes in forest net primary productivity in the Yangtze River basin and its relationship with climate change and human activities. Remote Sens. 11, 1451 (2019).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. The proportion of soil-borne pathogens increases with warming at the global scale. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 550–554 (2020).

Li, Z.-P. et al. Colonization ability and uniformity of resources and environmental factors determine biological homogenization of soil protists in human land-use systems. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17411 (2024).

Tiemann, L. K., Grandy, A. S., Atkinson, E. E., Marin-Spiotta, E. & McDaniel, M. D. Crop rotational diversity enhances belowground communities and functions in an agroecosystem. Ecol. Lett. 18, 761–771 (2015).

Peng, Z. et al. Land conversion to agriculture induces taxonomic homogenization of soil microbial communities globally. Nat. Commun. 15, 3624 (2024).

Jiang, Y., Jin, C. & Sun, B. Soil aggregate stratification of nematodes and ammonia oxidizers affects nitrification in an acid soil. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 3083–3094 (2014).

Yang, B., Zhang, T., Huang, J., Bhusal, D. R. & Pang, X. Response of soil nematode community to phosphorous amendment in a Subalpine Spruce Plantation. CLEAN Soil Air Water 47, 1800202 (2019).

Catano C. P., Fristoe T. S., LaManna J. A., Myers J. A. Local species diversity, β-diversity and climate influence the regional stability of bird biomass across North America. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 287, 20192520 (2020).

Dornelas, M. et al. Assemblage time series reveal biodiversity change but not systematic loss. Science 344, 296–299 (2014).

Magurran, A. E., Dornelas, M., Moyes, F., Gotelli, N. J. & McGill, B. Rapid biotic homogenization of marine fish assemblages. Nat. Commun. 6, 8405 (2015).

Rousk, J. et al. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. Isme J. 4, 1340–1351 (2010).

Tsiafouli, M. A. et al. Intensive agriculture reduces soil biodiversity across Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 973–985 (2015).

Archidona-Yuste, A. et al. Agriculture causes homogenization of plant-feeding nematode communities at the regional scale. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 2881–2891 (2021).

Becker, J., Eisenhauer, N., Scheu, S. & Jousset, A. Increasing antagonistic interactions cause bacterial communities to collapse at high diversity. Ecol. Lett. 15, 468–474 (2012).

Yu, X., Polz, M. F. & Alm, E. J. Interactions in self-assembled microbial communities saturate with diversity. Isme J. 13, 1602–1617 (2019).

Andriuzzi, W. S. & Wall, D. H. Grazing and resource availability control soil nematode body size and abundance–mass relationship in semi-arid grassland. J. Anim. Ecol. 87, 1407–1417 (2018).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 7, 10541 (2016).

Allison, S. D. et al. Microbial abundance and composition influence litter decomposition response to environmental change. Ecology 94, 714–725 (2013).

Reu, J. C., Catano, C. P., Spasojevic, M. J. & Myers, J. A. Beta diversity as a driver of forest biomass across spatial scales. Ecology 103, e3774 (2022).

Wisnoski, N. I. et al. Diversity–stability relationships across organism groups and ecosystem types become decoupled across spatial scales. Ecology 104, e4136 (2023).

Sankaran, M. & McNaughton, S. J. Determinants of biodiversity regulate compositional stability of communities. Nature 401, 691–693 (1999).

Olden, J. D. et al. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of biotic homogenization. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 18–24 (2004).

Gossner, M. M. et al. Land-use intensification causes multitrophic homogenization of grassland communities. Nature 540, 266 (2016).

Rong, S. et al. Soil sampling methods for microbial study in montane regions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 47, e02679 (2023).

Wu, L. et al. Environmental preferences of soil microbial attributes for long-term nitrogen and acid addition: from phylotype to community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 197, 109541 (2024).

Oliverio, A. M. et al. The global-scale distributions of soil protists and their contributions to belowground systems. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax8787 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Database and primer selections affect nematode community composition under different vegetations of Changbai Mountain. Soil Ecol. Lett. 5, 142–150 (2023).

Louca, S., Parfrey, L. W. & Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 353, 1272–1277 (2016).

Põlme, S. et al. FungalTraits: a user-friendly traits database of fungi and fungus-like stramenopiles. Fungal Divers. 105, 1–16 (2020).

Xiong, W. et al. Rhizosphere protists are key determinants of plant health. Microbiome 8, 27 (2020).

Bjorbækmo, M. F. M., Evenstad, A., Røsæg, L. L., Krabberød, A. K. & Logares, R. The planktonic protist interactome: where do we stand after a century of research?. ISME J. 14, 544–559 (2019).

Yeates, G. W., Bongers, T., De Goede, R. G., Freckman, D. W. & Georgieva, S. S. Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera-an outline for soil ecologists. J. Nematol. 25, 315–331 (1993).

Kraft, N. J. B. et al. Disentangling the drivers of β diversity along latitudinal and elevational gradients. Science 333, 1755–1758 (2011).

Wang, B. et al. Grazing simplifies soil micro-food webs and decouples their relationships with ecosystem functions in grasslands. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 960–970 (2020).

Herren, C. M. & McMahon, K. D. Cohesion: a method for quantifying the connectivity of microbial communities. ISME J. 11, 2426–2438 (2017).

Yuan, M. M. et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 343–348 (2021).

Chen, D. Forest conversion-induced soil biota homogenization destabilizes ecosystem functions. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16938748 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42177272, 32571913, 42107269, and 32201314) and the Junma Program of Inner Mongolia University (10000-23112101/159).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C., S.L., and X.Z. conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; X.Z., S.L., B.W., H.Z., L.W., and Y.W. collected the data and analysed it; X. Z., B.W., and D.C. led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave their final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Jing Wang, Chong Li and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Guopeng Liang and Mengjie Wang. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Liu, S., Wang, B. et al. Forest conversion-induced soil biota homogenization destabilizes ecosystem functions. Commun Earth Environ 6, 882 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02909-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02909-7