Abstract

The surface chemical composition of the Moon holds key insights into its geological evolution and resource potential. With future missions targeting the lunar south pole, there is a pressing need for high-resolution chemical maps of this region. Here we integrate spectral data with the latest Chang’E-6 samples, which are the first returned from the lunar farside, to refine global estimates of major oxides. A classical equation was applied to produce updated maps of FeO, TiO2, and optical maturity, while a deep learning model was constructed to invert more complex oxides across the lunar surface. The addition of Chang’E-6 samples further corrected the TiO2 content of lunar surface. The machine learning approach captures nonlinear links between reflectance and geochemistry, enabling robust mapping of oxides. These results reveal basaltic signatures in the south polar region, suggesting volcanic activity, and provide a framework for investigating the Moon’s thermal evolution and resource potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The surface chemical composition of the Moon provides critical insights into its regional geological evolution and the spatial distribution of potential resources. High-resolution chemical maps have been widely used for lunar geological mapping and resource assessment1,2,3,4,5. The upcoming Chang’E-7 and Artemis missions are targeting the lunar south pole, at the periphery of the South Pole-Aitken Basin, the largest and oldest known impact basin on the Moon6,7,8. These regions are thought to expose ancient mantle-derived materials9,10,11. Investigating the surface composition in the south polar and adjacent high-latitude regions may thus yield valuable insights into the lunar geological processes, lunar evolution, impact history of the Earth-Moon system, and potential for in-situ resource utilization12,13. Moreover, global chemical composition maps can serve as a reference for assessing the distribution of metallic resources on the Moon, which will be of practical importance for future extraterrestrial construction and lunar base site selection14,15.

The chemical composition of the lunar surface can be quantitatively derived from optical remote sensing data. Certain metal cations produce spectral absorption features at specific wavelengths16,17, and laboratory spectroscopic investigations have demonstrated that variations in chemical composition exert a measurable influence on reflectance spectra18,19,20,21. Lunar samples returned by the Apollo, Luna, and Chang’E missions provide direct geochemical measurements and serve as ground truth calibrations for determining the chemical composition of lunar surface. Of these, the Chang’E-6 mission returned the first samples from the Moon’s farside that can be used as the ground truth22, offering the only direct compositional data from this previously unsampled hemisphere. In addition, remote sensing observations have provided spectral reflectance data at spatial resolutions ranging from tens to hundreds of meters23,24,25,26,27,28. By correlating sample measurements with spectral reflectance, inversion models have been developed to estimate lunar surface composition. These high-resolution chemical maps offer significantly improved spatial detail compared to those derived from Lunar Prospector gamma-ray and neutron spectroscopy (GRNS), which has a spatial resolution of ~60 km/pixel29,30,31. The correlation between the abundance and spectral reflectance of Fe and Ti, as transition elements, was the first to be discovered. Quantitative global estimation of FeO and TiO2 were developed based on Clementine UVVIS data, and represented as mathematical equations23,24,32,33. These models were later applied to the FeO and TiO2 inversion derived from the Kaguya Multiband Imager (MI)25. More recently, machine learning approaches have expanded the suite of elements that can be predicted from spectral data, enabling estimation of SiO2, Al2O3, MgO, and CaO from Clementine, Kaguya, and Chang’E-1 Interference Imaging Spectrometer (IIM) data34,35,36,37,38. Among these, MgO content can be used to indicate magma evolution, and the magnesium number (Mol% of Mg/(Mg+Fe), Mg#) derived from MgO data has been widely used to investigate crustal and mantle processes on the Moon37,38. The accuracy of chemical composition estimates obtained from optical remote sensing inversions is lower than that achieved through controlled ground truth for optical remote-sensing instruments. Nevertheless, remote sensing data remains the primary resource for mapping the chemical composition of the lunar surface19, serving both regional and global studies.

The combined use of lunar sample analyses, spectral reflectance measurements, and inversion models has advanced our understanding of the Moon’s chemical diversity. The 1935.3 g of samples returned by the Chang’E-6 mission from the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin provide a rare and critical ground truth dataset from the farside of the Moon22. These samples are dominated by the younger mare eruption, with typical low-titanium basalts emplaced by volcanism in the SPA at ~2.83 Ga22,39. Geochemical evidence indicates that these magmas were derived from a lunar mantle source depleted in incompatible elements39. The Chang’E-6 collection established a new chemical calibration point for younger mare, complementing the data provided by Chang’E-522,39,40. Moreover, these samples furnish refined chemical composition and regional age calibration for both the lunar south polar and farside regions. To date, high-resolution major oxides and Mg# maps have not extended beyond 65° latitude. Existing Mg# maps derived from Kaguya MI data are limited to the 65°N-65°S range37,38. In this work, we establish a reliable surface ground truth at the Chang’E-6 landing site using returned sample measurements and integrate these with previous mission data to perform surface compositions inversion. Clementine Ultraviolet/Visible (UVVIS) spectral data were utilized to derive global maps of major oxides (FeO, TiO2, Al2O3, MgO, and CaO) and Mg#. The spectral data were carefully matched to the known compositions at each sample return site (see Supplementary Table 1). A mathematical model for FeO and TiO2 inversion was improved, and a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D CNN) model was developed to predict the abundance of major oxides across the lunar surface. Results from both models were compared to evaluate the contribution of the Chang’E-6 samples. Furthermore, the newly generated chemical maps were applied to investigate the composition and geological context of the lunar south polar and its surrounding high-latitude regions.

Results

The Clementine mission acquired global multispectral coverage of the Moon, and its spectral dataset remains the primary resource for mapping lunar surface chemistry at the global scale. In this study, Clementine spectral reflectance and the measured chemical abundances of lunar samples from the Apollo, Luna, and Chang’E missions (Supplementary Table 1), were employed as input for inversion modeling (Method). The measured oxide contents of these lunar samples are used as the ground truth, corresponding to the Clementine spectral reflectance of the sampling sites. The oxide contents determined from these lunar samples serve as ground truth, correlated with the Clementine spectral reflectance from the corresponding sampling sites. Notably, Apollo 16 and Luna 20 represent non-mare regions, whereas the remaining samples were predominantly collected from mare regions. Previous studies have found the band ratios and oxide contents, and these relationships can be expressed through empirical equations2,23,32,33. The equation model2,33,41 was followed and modified to establish the relationship between Clementine reflectance and FeO abundance, TiO2 abundance, and optical maturity (OMAT). Furthermore, the five bands reflectance of Clementine, OMAT, and the measured oxide abundances from lunar samples were used to construct a training dataset for a 1D CNN inversion model. The addition of OMAT introduced optical maturity information, thereby constraining the effects of lunar surface maturity for the inversion model. The prediction accuracies of the inversion models and the verification accuracies obtained through leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) for the CNN models are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. For the equation-based models, the determination coefficients (R2) of FeO and TiO2 abundances are 0.923 and 0.798. Equation models revealed linear relationship between reflectance and oxide abundance in several bands of the spectrum. Moreover, the CNN models achieved R2 values exceeding 0.96 for the prediction of all five major oxides. The LOOCV results further demonstrate robust performance, with validation R2 values of 0.897 for FeO, 0.831 for TiO2, 0.947 for Al2O3, 0.755 for MgO, and 0.918 for CaO. These results indicate the strong performance and high reliability of the CNN models in estimating the abundances of the five major oxides. Moreover, comparison between the CNN predicted oxide maps and the Lunar Prospector (LP) Gamma-Ray Spectrometer (GRS)42,43 measurements (Supplementary Figs. 3–7) shows that the predicted and observed values are similar in range, exhibit strong positive correlations, and that the statistical distribution of their differences approximates a normal distribution. This consistency underscores the reliability of the CNN based compositional inversion. Chemical composition mapping ultimately depends on the correlation models that link lunar samples with remotely sensed spectra. Both the availability of lunar samples and the quality of spectral data directly influence the accuracy of the inversion results. At present, a limitation is the paucity of ground truth samples from high latitude regions, where compositional estimates are largely extrapolated from empirical relationships established at mid to low latitudes. Future missions, such as Chang’E-7 and Artemis to the lunar south pole8, are expected to address this gap by providing critical ground truth constraints for high latitude compositions.

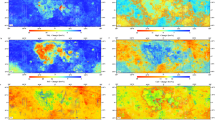

The FeO and MgO abundance maps derived from the CNN model were used to compute the Mg# map. The new oxide, Mg#, and OMAT maps are presented in Fig. 1, the value ranges presented in the maps follow the 95% confidence intervals. An equal-area sampling method (Methods) was applied to generate histograms of these map results (Supplementary Fig. 2). The histograms of five major oxides for CNN models and Mg# are shown in Fig. 2. Equation FeO presents bimodal distribution with lower and higher modes of 4.47 wt.% and 18.82 wt.%, and Equation TiO2 presents unimodal continuous distribution. These patterns are consistent with previous studies based on the Interference Imaging Spectrometer (IIM), KAGUYA Multiband Imager (MI), and Clementine data28,33,38. These three results reported lower modes of FeO abundance of 6.37 wt.%, 4.12 wt.%, and 4.5 wt.% and the higher modes of 15.01 wt.%, 18.23 wt.%, and 17.1 wt.%. In contrast, the CNN FeO and TiO2 both display unimodal continuous distribution, while CNN Al2O3, MgO, and CaO exhibit bimodal distributions (Fig. 2a). CNN FeO presents a unimodal distribution with a mode of 5.28 wt.%, this unimodal characteristic is consistent with the LP GRS measurement of 4.7 wt.%43. CNN TiO2 presents unimodal continuous distribution with a mode of 0.42 wt.%. CNN Al2O3, MgO, and CaO present the lower modes of 11.63 wt.%, 5.11 wt.%, and 10.63 wt.%, respectively, and the higher modes of 27.76 wt.%, 10.31 wt.%, and 16.38 wt.%. Mg# presents unimodal continuous distribution with a mode of 0.634 (Fig. 2b). These modal distribution characteristics are dominated by differences in the distribution of Maria and Non-maria. Notably, CNN FeO map indicates more high FeO abundance regions (>24 wt.%), in agreement with LP observations43, but distinct from previous estimates based on IIM, MI, Clementine, and our Equation FeO model28,33,38.

a, b and i show the maps of FeO, TiO2, and OMAT calculated from equation model. c–h show the maps of FeO, TiO2, Al2O3, MgO, CaO, and Mg# calculated from one-dimensiona convolutional neural network model. Mg # map highlights the approximate boundaries of maria with black lines50.

The average abundances of chemical compositions and OMAT in the maria, non-maria, and global are presented (Table 1). The approximate boundaries of maria are shown in Fig. 1h, and the mean values of each unit were calculated using the equal-area sampling method (Methods). CNN FeO has a higher valuation than Equation FeO, with global, maria, and non-maria units being 0.25 wt.%, 0.86 wt.%, and 0.12 wt.% higher, respectively. CNN TiO2 has a higher valuation than Equation TiO2, with global, maria, and non-maria units being 0.21 wt.%, 1.04 wt.%, and 0.03 wt.% lower, respectively. The abundance of these five oxides differs significantly between maria and non-maria units, and this difference is consistent with their modal distribution characteristics (Fig. 2a). In addition, Mg# in non-maria units is significantly higher than that in maria, with an average value of 0.632, which is close to the Mg# modal value of 0.634 (Fig. 2b).

Discussion

Influence of Chang’E-6 samples

The newly developed equation models were evaluated by comparing the updated Equation FeO and TiO2 maps with previous versions that did not incorporate Chang’E-6 samples44 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). The inclusion of Chang’E-6 data allows assessment of their influence on model outputs. The plot of the Equation FeO model (Supplementary Fig. 1c) shows that the Chang’E-6 sample data point lies close to the fitted regression line, with a deviation of ~0.47 wt.%, which is smaller than the root mean square errors (RMSE) of 1.37 wt.%. The addition of Chang’E-6 samples has increased the average estimated FeO abundance globally by 0.01 wt.%, decreased the average estimated FeO abundance in maria by 0.01 wt.%, and slightly increased the average estimated FeO abundance in non-maria, though these increase is negligible (Table 1 and Fig. 3a). The difference between the new and previous FeO maps generally falls within the range −0.04 and 0.03 wt.%, and the scatter plot of the two maps displays a strong linear correlation with minimal outliers (Fig. 3c–e). These findings indicate that the inclusion of Chang’E-6 samples has little impact on the FeO inversion model and that the FeO abundance measured at the Chang’E-6 site aligns well with the global distribution trends derived from previous lunar samples. Notably, the FeO map derived from Equation model shows a decrease in the valuation of Mare Tranquillitatis, with a large concentration of outliers, indicating a area of FeO abundance variation (Fig. 3a, e).

Difference maps between a Equation FeO and previous FeO, b Equation TiO2 and previous TiO2. The positive values represent higher FeO and TiO2 abundance for Equation FeO and TiO2. c Histogram of FeO difference. d Probability density function scatter plots of Equation FeO map and previous Equation FeO map. e Boxplot of FeO difference. f Histogram of TiO2 difference. g Probability density function scatter plots of Equation TiO2 map and previous Equation TiO2 map (TiO2 > 1 wt.%). h Boxplot of TiO2 difference.

In contrast, the Equation TiO2 shows a more substantial response from the Chang’E-6 data. The plot of the Equation TiO2 model (Supplementary Fig. 1d) shows that the result point of Chang’E-6 samples deviate from the fitted line, with a deviation of ~3.00 wt.%, greater than the RMSE of 1.24 wt.%. This deviation has resulted in differences between the new Equation TiO2 map and previous map. The addition of Chang’E-6 samples has increased the average estimated TiO2 abundance globally by 0.13 wt.%, decreased the average estimated TiO2 abundance in maria by 0.05 wt.%, and increased the average estimated TiO2 abundance in non-maria by 0.16 wt.% (Table 1 and Fig. 3b). The Chang’E-6 samples were sourced from the maria on lunar farside, with TiO2 content of 2.7 wt.%. This samples from maria were significantly lower than the fitted model results, leading to a reduction in the estimated TiO2 abundance of maria. The difference between two TiO2 maps is mainly between −0.4 and 0.3 wt.%. The scatter plots of the two results show a small range of values in the positive difference and a large range of values in the negative difference, and this is also reflected in the boxplot of TiO2 difference (Fig. 3f–h). The positive differences are relatively small and distributed in the non-maria, while the negative differences are large and distributed in the maria. These results of Equation TiO2 model and TiO2 abundance differences both indicate that the Chang’E-6 samples have impact on previous TiO2 model, leading to a reduction in the estimated TiO2 abundance of maria. Furthermore, these findings indicate that current inversion models still suffer from limited sample constraints on the lunar farside. Additional farside samples will be essential for further optimizing inversion models and advancing our understanding of the compositional dichotomy between nearside and farside maria. Similar to the FeO results, the new Equation TiO2 map show a significant decrease in the valuation of Mare Tranquillitatis. And the estimated TiO2 abundance in the eastern part of Oceanus Procellarum has decreased (Fig. 3a). These variations in FeO and TiO2 abundances highlight Mare Tranquillitatis as a region of particular interest that warrants further geochemical and geological investigation. Notably, the new results reveal that the average abundances of FeO, Al2O3, MgO, and CaO in Mare Tranquillitatis are consistent with the measured values of the Chang’E-6 samples (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1), with only TiO2 showing significant difference. This compositional similarity may imply notable reevaluations for Mare Tranquillitatis, as the new estimates bring the chemical abundances closer to the sample measurements. The discrepancy in TiO2 content between the two regions may reflect differences in magmatic evolution history, an issue that requires further investigation.

Insights from machine learning results

Two sets of FeO and TiO2 abundance maps were generated using the equation model and CNN model, respectively. These maps were compared to assess differences in prediction outcomes (Fig. 4). Compared to Equation FeO map, the CNN FeO map estimate FeO abundance that are 0.25 wt.% higher on average globally, 0.88 wt.% higher on average in maria, and 0.12 wt.% higher on average in non-maria (Table 1 and Fig. 4a). Difference between these two FeO maps is mainly between −4.03 and 3.54 wt.%, with outliers outside this range (Fig. 4d, e). The CNN model estimated higher FeO abundance in maria and highland regions, but lower FeO abundances in SPA basin. This phenomenon is characteristic of machine learning models, as demonstrated by comparisons of the results of equation models, random forest models, and CNN models35. The difference in FeO abundance is particularly pronounced in Oceanus Procellarum, which is the region with the highest FeO abundance globally (Figs. 1a, c, and 3a). CNN FeO reveals that the FeO abundance in this region is >24 wt.%, while Equation FeO estimates that the FeO abundance in this region is ~21 wt.%. For this discrepancy, we consider the map from the CNN FeO model to be more reasonable. LP data also confirm that FeO abundance >24 wt.% within Oceanus Procellarum29. Furthermore, Chang’E 5 completed sampling in the Oceanus Procellarum, and the samples revealed highly evolved basaltic clasts (Mg#: 0.29, FeO: 24.7 wt.%, TiO2: 5.75 wt.%)45. These measurements are consistent with the Oceanus Procellarum characteristics inferred by the CNN model (Fig. 1c, d, h).

Difference maps between a Equation FeO and CNN FeO, b Equation TiO2 and CNN TiO2. The positive values represent higher FeO and TiO2 abundance for Equation FeO and TiO2. c Histogram of FeO difference. d Probability density function scatter plots of Equation FeO map and CNN FeO map. e Boxplot of FeO difference. f Histogram of TiO2 difference. g Probability density function scatter plots of Equation TiO2 map and CNN TiO2 map (TiO2 > 1 wt.%). h Boxplot of TiO2 difference.

Compared to Equation TiO2 map, the CNN TiO2 map estimate TiO2 abundance that are 0.21 wt.% lower on average globally, 1.04 wt.% lower on average in maria, and 0.04 wt.% lower on average in non-maria (Table 1 and Fig. 4b). The difference between these two TiO2 maps is mainly between −0.48 and 2.72 wt.%, with outliers outside this range (Fig. 4g, h). The CNN model suggests that TiO2 abundance within maria is lower, and this difference is more pronounced in Oceanus Procellarum and Mare Tranquillitatis, at >3 wt.% (Fig. 4b). For this discrepancy, we consider the map from the CNN TiO2 model to be more reasonable. Equation TiO2 map suggests that high-TiO2 basalts are widely distributed in the eastern part of Oceanus Procellarum and Mare Tranquillitatis, with TiO2 abundance >9 wt.% (Fig. 1b). However, CNN TiO2 map suggests that this high-TiO2 materials are mainly concentrated in the northern and southwestern parts of the Mare Tranquillitatis, and the TiO2 in Oceanus Procellarum is ~4 wt.% (Fig. 1d). CNN TiO2 map is consistent with LP TiO2 measurement results. LP did not detect any signals with high-TiO2 abundance (>9 wt.%) globally, with only one or two pixel areas in Mare Tranquillitatis showing TiO2 abundance of 8.0 and 7.9 wt.%46. Moreover, Apollo 11 collected samples from the southwestern part of Mare Tranquillitatis. The TiO2 abundance of the corresponding sampling points is 7.9 wt.%, and several high-TiO2 basalt were found in these samples, with sample 10022 having the highest TiO2 of 12.2 wt.%47. The Apollo 16 sampling sites are located within the Descartes Highlands, near Mare Tranquillitatis, but high-TiO2 basalt was still found in these samples, with sample 60603 having the highest TiO2 of 14.5 wt.%48,49. Previous studies have suggested that the high-TiO2 basalt sample 60639, 10–16 from Apollo 16 likely derived from Mare Nectaris, as its TiO2 content aligns with this region, though it has a higher FeO content48. Based on our CNN five oxide maps, we suggested that sample 60639 (FeO of 16–19.9 wt.%, TiO2 of 6.3–7.9 wt.%, Al2O3 of 12.4–15.1 wt.%, MgO of 5.2–7.5 wt.%, and CaO of 10.6–11.5 wt.%) is more likely to have derived from the southwestern part of Mare Tranquillitatis, as the chemical composition of the sample is more consistent with that region. The Apollo 17 sampling sites are located at the northern end of Mare Tranquillitatis, southeastern edge of Mare Serenitatis. The samples contain low-TiO2 basalt and high-TiO2 basalt. The Apollo 17 LRV12 sampling site has the highest TiO2 of 10.0 wt.%, and the TiO2 of basalt sample 70017 is as high as 13.75 wt.%. These high-TiO2 basalt samples are all associated with Mare Tranquillitatis. From the perspective of spatial distribution characteristics, CNN TiO2 map is also more consistent, with high-TiO2 basalt distributed in the northern and southwestern parts of Mare Tranquillitatis.

Comparison of remote sensing data and lunar samples indicates that the inversion results of CNN model are reliable. The CNN FeO and TiO2 maps provide a reasonable description of local areas. Most importantly, the CNN model can depict the nonlinear relationship between oxide content and spectral reflectance. This allows the CNN FeO and TiO2 maps to provide a more reasonable description of local areas. This methodology also enables mapping of Al2O3, MgO, and CaO abundances, enriching our understanding of lunar surface geochemistry. In addition, the CNN chemical composition maps show that high-TiO2 basalts are mainly distributed in the northern and southwestern parts of Mare Tranquillitatis. This provides remote sensing data constraints for the provenance of high-TiO2 basalt samples on the Moon and may provide a reference for petrogenetic model for the lunar basalts.

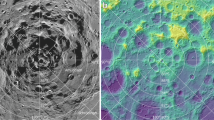

New view of south polar region

New chemical composition and Mg# maps provided essential chemical information for investigating the lunar south polar region (>65°S). Using CNN FeO and Mg# maps, we analyzed the surface chemical composition to identify potential exposures of mare basalt (Fig. 5). Equal-area sampling method extracted 633949 points from the south polar region, corresponding to a surface area of ~1426385.25 km2. Among these, 51421 points (~115697.25 km2, ~8.1% of the lunar south polar region) show chemical compositions broadly similar to mare basalts elsewhere on the Moon50. Sample points (Fig. 5a) with high FeO content are more likely to have been exposures of mare basalt in the lunar south polar region. Therefore, the overlap samples were further screened to extract information with FeO >15 wt.% and Mg# <60. We identified 42,762 points (~96214 km², ~6.7% of the lunar south polar region) as potential high-FeO material exposures (Fig. 5b). These high-FeO materials are primarily distributed on basin floors, crater walls, and central peaks, rather than forming extensive, continuous mare basalt plains. This observation is consistent with previous studies suggesting the absence of large-scale mare basalt units in the lunar south polar region50.

a Comparisons on FeO abundance and Mg#. In the main image, gray dots represent samples from maria units50 around the globe, blue dots represent samples from south polar region (>65°S), and red dots represent the overlap between the two. The upper part of X-axis shows FeO abundance histogram, and the right part of Y-axis shows Mg# histogram. b Potential distribution of mare basalt in south polar region. The base image is the WAC global mosaic map (WAC_GLOBAL_P900S0000_100M). The yellow markers represent sampling points in areas of exposed mare basalt. All of the above results were obtained using equal-area sampling (Methods).

The origin of these high-FeO materials likely involve volcanism or impact-related processes. Mafic magmas produced by volcanic activity may have erupted or overflowed onto the surface, forming localized basaltic flows or pyroclastic deposits51. Ancient cryptomaria, mare basalts later buried by ejecta, have also been identified elsewhere on the Moon52,53,54. However, no confirmed mare basalt units have been found in south polar region50, nor have any dark-halo impact craters been found to prove the existence of cryptomare55,56. This absence argues against widespread volcanic resurfacing in south polar region. Nevertheless, several impact basins in the region exhibit compelling evidence for volcanic contributions. In Schrödinger basin (75°S, 132.5°E), basaltic lava flows and a large pyroclastic vent confirm past volcanism57,58. These high-FeO materials exposures at their floors (Fig. 5b). Bouguer gravity anomalies reveal a central mascon (Supplementary Fig. 8a), while gravity gradients show a linear negative anomaly (Supplementary Fig. 8b), consistent with a mafic dike intrusion59. Similar gravity signatures (Supplementary Fig. 8), coupled with high-FeO exposures (Fig. 5b), are also found on the floors of Antoniadi crater (69.3°S, 173.1°W) and Zeeman crater (75.1°S, 135.1°W), suggesting localized volcanic activity. In contrast, other high-FeO exposures on central peaks and crater walls show no corresponding gravity anomalies. These materials are more plausibly explained as uplifted deep-seated rocks or impact-induced ejecta flows from distant sources56,60,61. In summary, the combined surface geochemistry and gravity analyses indicate that the lunar south polar region hosts both volcanic and impact-related high-FeO materials. The chemical composition maps offer valuable insights for identifying and characterizing volcanic features in this region. These new maps provide opportunities to investigate the volcanic history of the lunar south polar region and to advance our understanding of the thermal and magmatic evolution of the lunar mantle.

Methods

Spectrum and samples

We collected Clementine UVVIS Digital Image Model (DIM) Mosaic and chemical contents of lunar samples to estimate the chemical contents of the lunar surface. The UVVIS DIM Mosaic has 5 spectral bands, with ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy at 415, 750, 900, 950, and 1000 nm, and covers the Moon’s surface from 90°N to 90°S with a spatial resolution of 100 m/pixel. Moreover, the measured chemical contents of lunar samples were sourced from the Apollo missions, Luna missions, and Chang’E missions. There are a total of 49 sample points, and the coordinates of the sampling points are also recorded (Supplementary Table 1). The chemical compositions are (FeO, TiO2, Al2O3, MgO, and CaO, and these data are derived from previously published work22,44. In this work, we have added new information about the Chang’E-6 samples, these has been analyzed and determined to represent the ground truth of the lunar surface22. The reflectance were extracted from the Clementine DIM Mosaic at these ground truth sites, with the reflectance from selected sample points averaged across pixels to reduce noise. The locations, reflectance, pixels averaged, and chemical compositions information of these 49 sampling points are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Equation models

We followed a classic mathematical equation model2,41 to reveal the relationship between Clementine spectral reflectance and the FeO abundance, TiO2 abundance, and OMAT of lunar surface. This model reveals the correlations between band ratios and chemical composition2,41, where the use of band ratio parameters helps to mitigate the influence of reflectance variations caused by illumination at different latitudes on the inversion of chemical abundances. We used 49 sets of reflectance and FeO abundance, TiO2 abundance, and OMAT from lunar samples to improve this equation model (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The key to Equation FeO is the selection of the location of the optimized origin, which serves as the computation of the Fe sensitive parameter, the \({\theta }_{{Fe}}\). In this work, an enumeration method is used to search the origin, where the search range is 0–0.2 at 750 nm, 1–2 at the band ratio (950 nm/750 nm), and the search pitch is (0.001, 0.001). Ultimately, the location (\({x}_{0{Fe}}\) = 0.018, \({y}_{0{Fe}}\) = 1.188) was selected as the Fe optimized origin. The R2 of the linear fitting results of FeO showed a maximum value of 0.923, and Equation FeO is as follows:

where \({R}_{950}\) is the 950 nm reflectance; \({R}_{750}\) is the 750 nm reflectance; \({\theta }_{{Fe}}\) is the Fe sensitive parameter; \({x}_{0{Fe}}\) = 0.018; \({y}_{0{Fe}}\) = 1.188.

We used the enumeration method to determine the best optimized origin for the Ti sensitive parameters, the \({\theta }_{{Ti}}\), as (\({x}_{0{Ti}}\) = 0, \({y}_{0{Ti}}\) = 0.481), where the search range is 0–1 at 750 nm, 0–1 at the band ratio (415 nm/750 nm), and the search pitch is (0.001, 0.001). The R2 of the linear fitting results of TiO2 abundance showed the maximum value of 0.798. Equation TiO2 is as follows:

where \({R}_{415}\) is the 415 nm reflectance; \({R}_{750}\) is the 750 nm reflectance; \({\theta }_{{Ti}}\) is the Ti sensitive parameter; \({x}_{0{Ti}}\) = 0; \({y}_{0{Ti}}\) = 0.481.

The OMAT calculation in this study adopts a classical method41, with an updated origin point for optimization. The origin point has been updated using the optimized parameters from our FeO estimation formula, as (\({x}_{0{omat}}\) = 0.018, \({y}_{0{omat}}\) = 1.188). The equation for OMAT is as follows:

where \({R}_{950}\) is the 950 nm reflectance; \({R}_{750}\) is the 750 nm reflectance; \({x}_{0{omat}}\) = 0.018; \({y}_{0{omat}}\) = 1.188.

Convolutional neural network models

We developed convolutional neural network models to reveal the relationship between Clementine spectral reflectance and the FeO, TiO2, Al2O3, MgO, and CaO abundance of lunar surface. Progress has been made in the inversion of iron and titanium contents, with classical equation models now relatively mature2,44. However, the spectral characteristics of Al2O3, MgO, and CaO are more complex, making it difficult to invert their abundances using traditional equation-based models. The development of machine learning algorithms offers new avenues for their inversion. Since different oxides exhibit unique spectral responses in specific bands, local information within the spectral sequences plays a crucial role in abundance inversion37. We adopted a CNN architecture as it effectively captures inter-band correlations through convolution and pooling operations, thus inheriting and expanding upon the rationale of classic mathematical equation model2,41.

To effectively extract local features embedded in the spectral sequences, the reflectance values from five spectral bands were combined with the OMAT value at each sample point to form a one-dimensional input vector of length six. Prior to model training, both input features and target oxide abundances were standardized using the z-score normalization method. The mean and standard deviation used for normalization were stored for consistent application during subsequent inversion tasks.The model architecture was constructed based on a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D CNN), which offers strong local perceptive capabilities and is particularly suitable for capturing localized spectral response patterns. The network comprises two consecutive Conv1D layers. The first convolutional layer employs 32 filters with a kernel size of 2 and utilizes the ReLU activation function to introduce nonlinearity in feature extraction. The second convolutional layer maintains the same number of filters and is designed to extract deeper and more abstract spectral features. Following the convolutional module, a MaxPooling1D layer with a pool size of 2 is applied to reduce feature dimensionality, lower the number of model parameters, and enhance generalization performance. The pooled feature maps are then flattened into a one-dimensional vector through a Flatten layer and passed into a fully connected Dense layer with 64 neurons, also activated by the ReLU function, to improve the model’s nonlinear representation capability. To prevent overfitting, L2 regularization with a coefficient of 0.001 is applied to all convolutional and dense layers.The output layer consists of a single neuron with a linear activation function, enabling continuous regression prediction of oxide abundance. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.01. The maximum number of training epochs was set to 400, and the batch size was 50. An early stopping strategy was implemented by monitoring the training loss: if the loss did not decrease for 30 consecutive epochs, training was halted early and the best-performing weights were restored. After training, the predicted results were inverse-transformed for performance evaluation against the actual values.

Evaluation and validation

We calculated the root mean square errors (RMSE) and determination coefficients (R2) to evaluate the performance of the inversion model.

where \(n\) is the number of samples; \({y}_{i}\) is the oxide abundances of the \(i\)-th sample; \(\bar{y}\) is the mean oxide abundance across all samples; and \(\hat{{y}_{i}}\) is the predicted oxide abundances of the \(i\)-th sample obtained from the inversion model.

To further validate the performance of the CNN model, we applied leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). The LOOCV is a model validation technique, suitable for small datasets, that assesses whether the trained model can be generalized to independent data62. In this work, 49 samples were available. For each iteration, one sample was set aside as the test sample, while the remaining 48 samples were used to train the model. The trained model then predicted the oxide abundance of the test sample. This process was repeated 49 times, producing inversion results for all samples. RMSE and R2 values were used to quantify model performance. Lower RMSE and higher R2 values indicate better predictive accuracy and stronger generalization capability of the inversion model, while reducing the risk of overfitting.

Equal-area sampling

To ensure uniform spatial representation of chemical composition data across the lunar surface, we employed an equal-area sampling scheme based on spherical geometry. Previous work has focused on counting the number of pixels in images35,37,38. We consider that this method of counting is prone to errors in high-latitude regions, leading to inaccuracies in global analysis. Given the inherent curvature of the Moon, conventional latitude–longitude gridding introduces distortions in areal representation, especially at high latitudes. To address this, we constructed a grid of quasi-equal-area sampling units by fixing the latitudinal step size and adaptively computing the corresponding longitudinal step size for each latitudinal band. The central parameter in the grid design was a target surface area of 2.25 km2 per sampling unit. We adopted a latitudinal step of 0.15°. For each latitudinal band, the central latitude was converted to radians, and the corresponding longitudinal step was calculated using the following expression:

where \(A\) is the target area (2.25 km²), \(R\) is the mean radius of the Moon (1737.4 km), \(\Delta \phi\) is the latitudinal step size in radians, and \(\phi\) is the central latitude of the band. The resulting longitudinal step \(\Delta \lambda\) was then converted to degrees to generate grid cells of approximately equal area.

This formulation ensures area preservation while accounting for latitudinal convergence of meridians. These equal-area sampling units were used for spatially statistical analysis of chemical composition distributions across the lunar surface.

Bouguer gravity and Bouguer gravity gradients

We computed the Bouguer anomaly by removing the gravity effects of terrain in GRGM1200B model63. We filtered the gravity model between degrees 60–600 to roughly constraint the gravity signals from the lunar crust. We chose 2550 kg/m3 as the crustal density64. The gravity anomaly was expanded on DH2 regular grids (Driscoll and Healy, 1994) and we used the stereographic projection to show better details of south pole. We computed the Bouguer horizontal gravity gradients65 from the Bouguer anomaly. Here we filtered the gravity gradients between degrees 50–350 to resist the noise contained in high-order coefficients. All the datasets was processed through SHTOOLS software66, performing spherical harmonic expansions and gradient computations.

Data availability

The Clementine UVVIS Digital Image Model Mosaic is available at the link (https://pdsimage2.wr.usgs.gov/Clementine/PDS4/data/). The Lunar Prospector Gamma-Ray Spectrometer data is available at the link (https://pds.nasa.gov/ds-view/pds/viewProfile.jsp?dsid=LP-L-GRS-5-ELEM-ABUNDANCE-V1.0). The LROC WAC image mosaic is available at the link (http://lroc.sese. asu.edu/). The GRGM1200B model is provided by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (https://pgda.gsfc. nasa.gov/products/75). The OMAT, Mg#, and the abundances of oxides (Equation FeO, Equation TiO2, CNN FeO, CNN TiO2, CNN Al2O3, CNN MgO, CNN CaO) are availablein the repository Zenodo via DOIs: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15739446, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15743333, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15736195, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15739157, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15742746, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15742802, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15742878, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15743164, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15746439.

References

Anand, M. et al. A brief review of chemical and mineralogical resources on the Moon and likely initial in situ resource utilization (ISRU) applications. Planet. Space Sci. 74, 42–48 (2012).

Lucey, P. G., Blewett, D. T. & Jolliff, B. L. Lunar iron and titanium abundance algorithms based on final processing of Clementine ultraviolet-visible images. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 105, 20297–20305 (2000).

Yamamoto, S., Matsuoka, M., Nagaoka, H., Ohtake, M. & Ikeda, A. Global distribution and geological features of ilmenite-rich sites on the lunar surface. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 130, e2024JE008663 (2025).

Yue, Z. et al. Geological context of the Chang’e-6 landing area and implications for sample analysis. Innovation 5, 100663 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Multiphysics simulation and optimization of the in-situ beneficiation process of ilmenite minerals from lunar regolith. Sci. China Earth Sci. 68, 195–207 (2025).

Joy, K. H. et al. Evidence of a 4.33 billion year age for the Moon’s South Pole–Aitken basin. Nat. Astron. 9, 55–65 (2024).

Su, B. et al. South Pole–Aitken massive impact 4.25 billion years ago revealed by Chang’e-6 samples. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf103 (2025).

Wang, C. et al. Scientific objectives and payload configuration of the Chang’E-7 mission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11, nwad329 (2024).

Jones, M. J. et al. A South Pole–Aitken impact origin of the lunar compositional asymmetry. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8475 (2022).

Melosh, H. J. et al. South Pole–Aitken basin ejecta reveal the Moon’s upper mantle. Geology 45, 1063–1066 (2017).

Moriarty, D. P. et al. Evidence for a stratified upper mantle preserved within the South Pole-Aitken Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 126, e2020JE006589 (2021).

Moriarty, D. P. & Petro, N. E. Mineralogical characterization of the lunar south polar region: 1. The Artemis exploration zone. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 129, e2023JE008266 (2024).

Weber, R. et al. The Artemis III science definition team report. In 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 1261 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2021).

Ciazela, J. et al. Lunar ore geology and feasibility of ore mineral detection using a far-IR spectrometer. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1190825 (2023).

Valentini, L., Moore, K. R. & Bediako, M. Sustainable sourcing of raw materials for construction: from the Earth to the Moon and beyond. Elements 18, 327–332 (2022).

Burns, R. G. & Burns, R. G. Mineralogical Applications of Crystal Field Theory (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Hunt, G. R. Spectral signatures of particulate minerals in the visible and near infrared. Geophysics 42, 501–513 (1977).

Noble, S. K., Pieters, C. M., Hiroi, T. & Taylor, L. A. Using the modified Gaussian model to extract quantitative data from lunar soils. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 111, 2006JE002721 (2006).

Isaacson, P. J. et al. The lunar rock and mineral characterization consortium: deconstruction and integrated mineralogical, petrologic, and spectroscopic analyses of mare basalts. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 46, 228–251 (2011).

Moriarty, D. P. & Pieters, C. M. Complexities in pyroxene compositions derived from absorption band centers: examples from Apollo samples, HED meteorites, synthetic pure pyroxenes, and remote sensing data. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 51, 207–234 (2016).

Pieters, C. M., Stankevich, D. G., Shkuratov, Y. G. & Taylor, L. A. Statistical analysis of the links among lunar mare soil mineralogy, chemistry, and reflectance spectra. Icarus 155, 285–298 (2002).

Li, C. et al. Nature of the lunar far-side samples returned by the Chang’E-6 mission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11, nwae328 (2024).

Blewett, D. T., Lucey, P. G., Hawke, B. R. & Jolliff, B. L. Clementine images of the lunar sample-return stations: refinement of FeO and TiO2 mapping techniques. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 102, 16319–16325 (1997).

Elphic, R. C. et al. Lunar rare earth element distribution and ramifications for FeO and TiO2: Lunar Prospector neutron spectrometer observations. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 105, 20333–20345 (2000).

Otake, H., Ohtake, M. & Hirata, N. Lunar iron and titanium abundance algorithms based on SELENE (Kaguya) multiband Imager data. In Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 1905 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2012).

Sato, H. et al. Lunar mare TiO2 abundances estimated from UV/Vis reflectance. Icarus 296, 216–238 (2017).

Surkov, Y., Shkuratov, Y., Kaydash, V., Korokhin, V. & Videen, G. Lunar ilmenite content as assessed by improved Chandrayaan-1 M3 data. Icarus 341, 113661 (2020).

Wu, Y. Major elements and Mg# of the Moon: results from Chang’E-1 Interference Imaging Spectrometer (IIM) data. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 93, 214–234 (2012).

Lawrence, D. J. et al. Iron abundances on the lunar surface as measured by the Lunar Prospector gamma-ray and neutron spectrometers. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 107, 13–1 (2002).

Lawrence, D. J., Maurice, S. & Feldman, W. C. Gamma-ray measurements from Lunar Prospector: time series data reduction for the Gamma-Ray Spectrometer. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 109, 2003JE002206 (2004).

Lawrence, D. J. et al. Global spatial deconvolution of Lunar Prospector Th abundances. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L03201 (2007).

Lucey, P. G., Taylor, G. J. & Malaret, E. Abundance and distribution of iron on the Moon. Science 268, 1150–1153 (1995).

Lucey, P. G., Blewett, D. T. & Hawke, B. R. Mapping the FeO and TiO2 content of the lunar surface with multispectral imagery. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 103, 3679–3699 (1998).

Korokhin, V. V., Kaydash, V. G., Shkuratov, Y. G., Stankevich, D. G. & Mall, U. Prognosis of TiO2 abundance in lunar soil using a non-linear analysis of Clementine and LSCC data. Planet. Space Sci. 56, 1063–1078 (2008).

Qiu, D., Li, F., Yan, J., Gao, W. & Chong, Z. Machine learning for inversing FeO and TiO2 content on the Moon: method and comparison. Icarus 373, 114778 (2022).

Xia, W. et al. New maps of lunar surface chemistry. Icarus 321, 200–215 (2019).

Yang, C. Comprehensive mapping of lunar surface chemistry by adding Chang’e-5 samples with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 7554 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. New maps of major oxides and Mg # of the lunar surface from additional geochemical data of Chang’E-5 samples and KAGUYA multiband imager data. Icarus 115505 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115505 (2023).

Cui, Z. et al. A sample of the Moon’s far side retrieved by Chang’e-6 contains 2.83-billion-year-old basalt. Science 386, 1395–1399 (2024).

Li, Q.-L. et al. Two-billion-year-old volcanism on the Moon from Chang’e-5 basalts. Nature 600, 54–58 (2021).

Lucey, P. G., Blewett, D. T., Taylor, G. J. & Hawke, B. R. Imaging of lunar surface maturity. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 105, 20377–20386 (2000).

Elphic, R. C. et al. Lunar Fe and Ti abundances: comparison of Lunar Prospector and Clementine data. Science 281, 1493–1496 (1998).

Prettyman, T. H. et al. Elemental composition of the lunar surface: analysis of gamma ray spectroscopy data from Lunar Prospector. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 111, (2006).

Qiu, D., Chen, W., Yan, J. & Yi, S. FeO and TiO2 maps of the lunar polar regions derived from the clementine data. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 130, e2024JE008753 (2025).

Jiang, Y. et al. Fe and Mg isotope compositions indicate a hybrid mantle source for Young Chang’E 5 mare basalts. Astrophys. J. Lett. 945, L26 (2023).

Prettyman, T. H. et al. Library least squares analysis of Lunar Prospector gamma-ray spectra. In 33rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2012 (Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), 2002).

Anderson, A. T. Exotic armalcolite and the origin of Apollo 11 ilmenite basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 35, 969–973 (1971).

Fagan, A. L. & Neal, C. R. A new lunar high-Ti basalt type defined from clasts in Apollo 16 breccia 60639. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 173, 352–372 (2016).

Zeigler, R. A., Korotev, R. L., Haskin, L. A., Jollif, B. L. & Gillis, J. J. Petrography and geochemistry of five new Apollo 16 mare basalts and evidence for post-basin deposition of basaltic material at the site. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 41, 263–284 (2006).

Nelson, D. M. et al. Mapping lunar maria extents and lobate scarps using LROC image products. In 45th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2861 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2014).

Head, J. W. et al. Lunar mare basaltic volcanism: volcanic features and emplacement processes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 89, 453–507 (2023).

Antonenko, I., Head, J. W., Mustard, J. F. & Ray Hawke, B. Criteria for the detection of lunar cryptomaria. Earth Moon Planets 69, 141–172 (1995).

Qiu, D. et al. New view of the Balmer-Kapteyn region: cryptomare distribution and formation. Astron. Astrophys. 659, A4 (2022).

Whitten, J. L. & Head, J. W. Lunar cryptomaria: physical characteristics, distribution, and implications for ancient volcanism. Icarus 247, 150–171 (2015).

Izquierdo, K. et al. Global distribution and volume of cryptomare and visible mare on the Moon from gravity and dark halo craters. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 129, e2023JE007867 (2024).

Qiao, L. et al. Geological evidence for extensive basin ejecta as plains terrains in the Moon’s South Polar Region. Nat. Commun. 15, 5783 (2024).

Jozwiak, L. M., Head, J. W. & Wilson, L. Lunar floor-fractured craters as magmatic intrusions: geometry, modes of emplacement, associated tectonic and volcanic features, and implications for gravity anomalies. Icarus 248, 424–447 (2015).

Kring, D. A. et al. Prominent volcanic source of volatiles in the south polar region of the Moon. Adv. Space Res. 68, 4691–4701 (2021).

Andrews-Hanna, J. C. et al. Ring faults and ring dikes around the Orientale basin on the Moon. Icarus 310, 1–20 (2018).

Cai, Y. et al. Fine debris flows formed by the Orientale basin. Earth Planet. Phys. 4, 1–11 (2020).

Petro, N. E. & Pieters, C. M. The lunar-wide effects of basin ejecta distribution on the early megaregolith. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 43, 1517–1529 (2008).

Kohavi, R. & others. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. IJCAI 14, 1137–1145 (1995).

Goossens, S. et al. High-resolution gravity field models from GRAIL data and implications for models of the density structure of the Moon’s crust. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, e2019JE006086 (2020).

Wieczorek, M. A. et al. The crust of the Moon as seen by GRAIL. Science 339, 671–675 (2013).

Andrews-Hanna, J. C. et al. Ancient igneous intrusions and early expansion of the moon revealed by GRAIL gravity gradiometry. Science 339, 675–678 (2013).

Wieczorek, M. A. & Meschede, M. SHTools: tools for working with spherical harmonics. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 2574–2592 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42241116, 42402230). Denggao Qiu is supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M770396, 2025T180106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Denggao Qiu contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology development, resources, software, validation, and original draft writing. Jianguo Yan contributed to project administration, resources, supervision, and revision. Bin Liu contributed to validation and revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Edward Cloutis, Jakub Ciążela and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Claire Nichols and Joe Aslin. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, D., Yan, J. & Liu, B. Global chemical composition maps of oxide distributions on the Lunar surface. Commun Earth Environ 6, 940 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02914-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02914-w