Abstract

Warming can alter the temporal stability of aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) in grasslands. However, it remains unclear how ANPP stability responds to long-term warming. Through a 10-year in-situ manipulative warming experiment conducted in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, we found warming initially enhanced ANPP stability and the positive effects of warming on ANPP stability tended to decline as the duration of the experiment was extended. Increased community height primarily enhanced ANPP and its stability under warming. However, declining sedge cover and reduced ecosystem carbon and water use efficiency under prolonged warming increased annual ANPP fluctuations, thereby negating the positive effects of warming on ANPP stability. Our findings provide the evidence that carbon and water use efficiency crucially maintain ANPP stability under long-term warming. These results highlight the necessity of a continuous long-term monitoring of ecosystem responses to warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Grasslands cover approximately 40% of the world’s land area and provide essential ecosystem services including forage production and climate mitigation1,2. The temporal stability of aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) is crucial for maintaining a stable forage supply and carbon sequestration in grassland ecosystems3. Global warming is an important driver of ANPP and its stability in grasslands4,5. However, it still remains unclear how ANPP temporal stability (ANPP stability) responds to warming over time.

The response of ANPP stability to warming was determined by alteration in ANPP and its fluctuation over a period of time6. The resistance-resilience theory has emphasized that ecosystems will demonstrate a range of responses that correspond to the duration of environmental change7. Hence, long-term investigations of ANPP and its fluctuation are essential to comprehensively understand warming effects on ecosystem stability. Previous studies have reported the positive effects of warming on ANPP may exist for a short term8,9. For example, a nine-year experiment in a semi-arid grassland revealed that warming enhanced ANPP during the first four years but began to decrease ANPP in the fifth year10. Additionally, many studies demonstrated important factors affecting ANPP fluctuation under long-term warming, such as plant diversity11,12, dominant species13, species asynchrony14 and nutrient availability15,16. Generally, empirical studies have demonstrated the importance of insurance effect driven by species asynchrony or dominant species on sustaining ANPP17,18,19. Differential species-specific responses to environmental variables20,21 enable compensatory growth dynamics wherein dominant species offset biomass losses in others22,23. Such compensatory mechanisms reflect how ecosystem component (e.g., plant community and soil nutrients) maintains ANPP. However, given the divergent responses of these components to long-term warming24, the mechanisms sustaining ANPP stability require elucidation over extended temporal scales. Crucially, ecosystem-level diagnostic indicators capable of predicting sustained ANPP under prolonged warming remain unidentified.

Ecosystem carbon use efficiency (CUE) and water use efficiency (WUE) serve as sensitive ecosystem-level indicators for climate change impacts. These metrics are intrinsically linked to ANPP dynamics, serving as robust proxies for carbon, water and energy flux processes25. Consequently, CUE and WUE may have a crucial linkage with ANPP stability under long-term warming. Ecosystem CUE is defined as the ratio of net ecosystem productivity (NEE) to gross ecosystem productivity (GEP)26,27,28. CUE reflects ecosystem-level carbon budget and exhibits strong coupling with ANPP dynamics29. Elevated CUE signifies optimized plant production, stable carbon sequestration, and sustained soil nutrient availability, which all critical for maintaining ANPP stability30,31. At the ecosystem scale, WUE is widely defined as the ratio of GEP to evapotranspiration (ET), where ET integrates transpiration, canopy, and soil evaporation32,33. High WUE indicates superior plant hydraulic regulation that buffers ANPP variability under water limitation34, especially in arid and semi-arid regions. Taken together, increased CUE and WUE demonstrate ecosystem adaptive capacity to environmental change, thereby promoting ANPP stability35,36. However, long-term warming typically exacerbates water constraints in arid and semi-arid regions, suppressing both CUE and WUE30,37. This impairment likely drives temporal ANPP instability under long-term warming. Crucially, the mechanistic roles of CUE and WUE in maintaining ANPP stability during prolonged warming remain unquantified and require further investigation.

The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau is often referred to as the ‘third pole’ on the world and is predominantly covered by alpine grasslands that provide multiple functions and services38. This region has been experiencing a notable warming trend39 that has significantly altered both plant productivity and stability40,41. To investigate the mechanisms underlying the maintenance of ANPP stability in response to prolonged warming, we conducted an in situ manipulative warming experiment in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 2011 to 2021. Our study aimed to address two questions: (1) How ANPP stability responds to warming over time; (2) What mechanisms govern the response of ANPP stability to long-term warming, especially considering the alteration in CUE and WUE? We hypothesized that long-term warming would decrease ANPP stability by altering plant community structure and reducing CUE and WUE.

Results

Changes in temporal production stability

Warming significantly increased ANPP (p < 0.05) in the alpine meadow after the duration of 1, 3, and 6 years (Fig. 1a). We quantified ANPP stability using three distinct metrics: cumulative, sliding-window, and non-overlapping period methods (see details in “Methods” section). Warming, experimental duration and their interactions significantly affected ANPP stability derived from cumulative and sliding window analysis (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Warming significantly increased ANPP stability (p < 0.05) during early stage (the first seven years for cumulative ANPP stability, the first four years for sliding-window ANPP stability, and the first three years with non-overlapping period ANPP stability) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2a, 2b). Linear regression analysis indicated the declining positive effects of warming on both cumulative and sliding-window ANPP stability over time (Supplementary Fig. 3). This trend was also corroborated by piecewise regression, which indicated a pronounced reduction in positive warming effects after the fourth year (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 2c).

a Line chart (Average ± SD, n = 4 under each treatment in each duration) for mean ANPP under ambient and warming conditions with the results of t-test and two-way ANOVA (W: warming; D: duration; W × D: interactions of warming and duration). Duration indicates the past years after warming from 2011. b Line chart (Average ± SD, n = 4 under each treatment in each duration or period) for the cumulative ANPP stability under ambient and warming conditions with the results of t-test and two-way ANOVA (W: warming; D: duration; W × D: interactions of warming and duration). c Piecewise linear regression (n = 32) for the relationship between the effect of warming on cumulative ANPP stability (∆ANPP stability after warming) and duration with R2 value and estimated break point (BP). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Changes in CUE, WUE and soil properties

Both warming treatment and experimental duration significantly affected CUE and WUE. As the experiment progressed, warming significantly reduced both CUE and WUE (Fig. 2d, e, p < 0.001). Warming did not significantly altered ER (p = 0.561), while significantly decreased NEE in 2016 and 2018–2021 (p < 0.05) and increased ET in 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2020 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2a–c). In addition, warming significantly reduced soil NH4+-N content in 2019 and 2021 (Fig. 2c), while increased soil NO3--N content in 2018 and 2019 (Fig. 2d).

a–e Line chart (Average ± SD, n = 4 under each treatment in each year) for NEE, ER, ET, CUE, and WUE under ambient and warming conditions with the results of t-test and two-way ANOVA (W: warming; Y: year; W × Y: interactions of warming and year). f, g Bar plots (Average + SD, n = 4 for each bar) with the result of t-test for the changes in soil NH4+-N and NO3--N contents under ambient and warming conditions. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Changes in plant community structure

Species asynchrony fluctuated throughout the experimental duration under both ambient and warming conditions (Fig. 3a). Warming did not significantly affect species asynchrony (p = 0.163, Fig. 3c). However, the interaction between warming and experimental duration had a significant impact on species asynchrony (p < 0.001). Warming significantly reduced species richness across the experimental period (p = 0.012, Fig. 3d). There were no significant interactive effects of warming and experimental duration on species richness (Fig. 3b).

a, b Line chart (Average ± SD, n = 4 under each treatment in each duration) for species asynchrony and richness under ambient and warming conditions with the results of two-way ANOVA (W: warming; D: duration; W × D: interactions of warming and duration). c, d Box plots (n = 32 for each box from duration 3 to duration 10) with the result of t-test for the changes in species asynchrony and species richness under ambient and warming conditions. *p < 0.05.

Warming significantly decreased sedge coverage across the experimental period (p < 0.001). Experimental duration significantly affected the coverage of all three functional groups (Fig. 4a–c). Warming significantly increased the dominance of forbs (p < 0.001) while decreasing the dominance of sedges (p = 0.002) across the experimental period (Supplementary Fig. 4). Soil NH4+-N content was positively correlated (p < 0.050) with sedge coverage while soil NO3--N content was negatively correlated (p < 0.050) with forb coverage (Fig. 4d, f). Overall, the reduction in soil moisture and soil NH4+-N content contributed to the decline in sedge coverage and this subsequently led to a decrease in community coverage (Figs. 4d and 5).

a–c Line chart (Average ± SD, n = 4 under each treatment in year) for each functional group coverage under ambient and warming conditions with the results of two-way ANOVA (W: warming; Y: year; W × Y: interactions of warming and year). d–f Linear correlation between each functional group coverage and soil NH4+-N as well as NO3--N contents under ambient and warming in 2018, 2019, and 2021 (n = 24 for each regression). Lines in figures indicated significant linear correlation (p < 0.05).

Correlation heat map between average of ANPP, SD of ANPP, plant, soil and ecosystem properties under ambient and warming (n = 64). Pie plot with color in figures indicated significant linear correlation. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. T: soil temperature; M: soil moisture; SR: species richness; SA: species asynchrony; CH: community height; CC: community coverage; SC: sedge coverage; GC: grass coverage; FC: forb coverage; RUE: ecosystem resource (carbon-water) use efficiency; AV: average of ANPP; SD: SD of ANPP. Average of ANPP, SD of ANPP, and species asynchrony were collected in the duration of 3–10 years from 2011 under ambient and warming using cumulative method (n = 64). Soil temperature, soil moisture, species richness, community height, community coverage, sedge coverage, grass coverage, forb coverage, ecosystem resource (carbon-water) use efficiency were collected from 2014 to 2021 under ambient and warming (n = 64).

Factors affecting ANPP stability

Correlation analysis indicated that the ANPP average was negatively correlated with soil moisture, ecosystem resource use efficiency, sedge coverage and community coverage and was positively correlated with soil temperature and community height. The SD of ANPP exhibited a positive correlation with community height and forb coverage. Both soil moisture and RUE (ecosystem carbon-water use efficiency, PC1 of CUE and WUE, see details in “Methods” section) were negatively correlated with the SD of ANPP. Species richness showed a positive correlation with soil moisture and community coverage. RUE was positively correlated with soil moisture, species richness, sedge coverage and community coverage. Neither the average nor SD of ANPP was significantly correlated with species asynchrony (p > 0.05).

SEM indicated that soil temperature alterations directly affected the ANPP SD (−0.26) while indirectly affecting both the ANPP average (0.35) and SD (0.45) by altering community height (0.25). Soil moisture positively affected sedge coverage (0.38) and community coverage (0.16) while negatively impacting community height and ANPP. Community coverage was positively correlated with RUE (0.35), whereas community height was positively correlated with the ANPP SD (0.42). Warming exhibited dual effects on ANPP stability via different pathways. On one hand, warming directly decreased the ANPP SD and indirectly increased the ANPP average by promoting community height, thereby enhancing ANPP stability. In contrast, reductions in soil moisture due to warming decreased sedge coverage, community coverage and RUE that subsequently increased the ANPP SD and led to a decrease in ANPP stability. Collectively, soil temperature had a total positive effect on average of ANPP (0.22) and a negative effect on SD of ANPP (−0.21), while soil moisture negatively affected both ANPP average (−0.53) and SD (−0.36) (Supplementary Fig. 5). The ANPP SD exhibited an increasing trend throughout the experimental period and was more sensitive to warming than to ambient conditions (Fig. 6b, c). Consequently, the positive effect of warming on ANPP stability diminished over time.

a The results of SEM showing the pathways that soil temperature, moisture, sedge coverage, community height and coverage affected ecosystem resource use efficiency (RUE), average ANPP and SD of ANPP. Numbers on the arrows indicated the significant standardized path coefficients (n = 64). The result of R square was showed nearby the factor box. In this figure, red path indicated significantly negative path, blue path indicated significantly positive path, and gray path indicated insignificant path. b, c The correlation between both ANPPaverage and ANPPSD and experimental duration in each treatment. Only significant linear regression was showed in the figures (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Ecosystem stability has garnered significant interest among scientists in the context of climate change and previous experimental studies have primarily focused on the responses of ANPP stability to environmental changes over specific time periods42,43,44. However, the impact of warming on ANPP stability across long-term experimental period has not been thoroughly investigated. Our results provide strong evidence that the positive effect of warming ANPP stability diminished over time in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau.

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of species richness on ANPP stability, as greater species richness ensures higher species asynchrony to maintain ANPP16. In cold regions, warming can enhance heat resource availability45 but may also increase water limitations for plant growth46. Consequently, the responses of different plant species to these environmental changes determined the direction of community succession under warming. The process of capturing the changes in species richness and asynchrony under simulated warming may require an extended period47. The combined stress of heat and drought caused by warming could also decrease species richness48. We found the effect of warming on species asynchrony was determined by experimental duration (Fig. 3). Consistent with previous studies3,49, species asynchrony was influenced by biotic and abiotic conditions across different years. This variation also affected the differences in interannual ANPP, thereby altering the correlation between species asynchrony and ANPP stability50. However, we found no significant correlation between species asynchrony and richness with ANPP stability.

Dominant functional groups generally regulate the fluctuation in community ANPP in response to warming51. We found that sedge coverage contributed to changes in community coverage that in turn drove ecosystem carbon and water resource use efficiency and thereby indirectly altered ANPP stability. Sedge coverage was particularly vulnerable to water stress under warming conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4). This observation may be attributed to specific plant functional traits. Compared to the taproots of forbs and grasses, the fibrous roots of sedges exhibited weaker resistance to drought induced by warming52,53. However, warming could increase community height and this would elevate ANPP (Fig. 6). Therefore, the response of ANPP stability to warming was determined by the combined effects of increased community height and decreased sedge coverage.

Soil nutrient content and especially available nitrogen can adjust functional group dominance and regulate community ANPP stability54. We found that warming decreased soil NH4+-N and this was positively correlated with sedge coverage. Therefore, the reduction in soil NH4+-N may indirectly decrease affect ANPP stability. A previous study indicated that the nitrogen absorption of dominant species tended to favor NH4+-N over NO3--N as competition among species intensified in a dry alpine meadow55. Additionally, a 15N tracer experiment also suggested dominant alpine plants preferred to use NH4+-N rather than NO3--N56. In alpine grasslands, sedge roots are composed of a dense network that makes full use of soil NH4+-N whereas grasses and forbs tend to absorb NO3--N57. Warming could accelerate soil nitrogen cycling and improved nitrification and thus promote NH4+-N to NO3--N transformations58. Therefore, under prolonged warming conditions, the transformation of available nitrogen may decrease sedge coverage and ultimately reduce ANPP stability.

Carbon and water use efficiency in terrestrial ecosystems are correlated not only with energy balance59 but also with disturbance resistance60. From a long-term perspective, higher resource use efficiency can enhance the ability of plant communities to adapt to environmental changes, serving as an essential driver of sustainable ecosystem productivity61. Our results emphasized the importance of ecosystem carbon and water use efficiency on decreasing ANPP fluctuations (Fig. 6). Despite the alleviation of low-temperature restrictions on plant growth, warming can exacerbate water stress46. These changes can alter ecosystem carbon and water use efficiency62. Warming also reduced CUE and WUE by decreasing plant species richness (Fig. 5). The reason for this is that multiple species can enhance ecosystem resource use efficiency through a complementary effect63,64.

Our results indicated warming caused a decoupling of carbon absorption and evapotranspiration at ecosystem level (Fig. 2). This decoupling may originate at the leaf level photosynthesis and transpiration32,65,66. Warming can reduce photosynthetic rates through inhibiting ribulose-1.5-bisphosphate resynthesis and decreasing Rubisco activity67. Furthermore, warming affects stomatal regulation of carbon-water exchange68. Stomatal closure under water limitation typically reduces both net photosynthesis and transpiration to conserve water and carbon69,70. However, some studies reported a decoupling under warming, where stomata remained open despite reduced photosynthetic rates71,72, due to defending leaf from thermal damage under warming73. The decreased NEE and increased ET observed in our study suggest such leaf-level decoupling may occur, though further investigation is needed to confirm this mechanism. Additionally, despite reduced surface soil moisture under warming, ET increased (Fig. 3). This could arise from vegetation adaptations enhancing resource acquisition capacity during warming-induced drought74. For example, warming can improve root length, leaf carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus use efficiency, likely enable plants to access deeper soil water and nutrients, sustaining growth and ET37,75. Moreover, reduced vegetation cover under warming is another potential factor. Declining cover can increase bare soil areas, diminish the shading76 and water retention77 effects of vegetation. This can enhance soil evaporation, thereby increasing ecosystem ET78.

Our study contributes to the deepening of our understanding of ANPP stability responses to long-term warming. Warming had dual effects on ANPP stability. It enhanced stability by increasing community height and ANPP; however, under prolonged warming, stability was constrained by reduced community coverage and decreased ecosystem resource use efficiency. As water limitations intensified, the increase in annual ANPP fluctuation, driven by a decline in sedge coverage and a reduction in ecosystem resource use efficiency, diminished the positive effect of warming on ANPP stability (Fig. 6). These observations indicate that in response to climatic warming, there are periodic fluctuations in the productivity and temporal stability of alpine meadow ecosystems. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct long-term research to understand the response of ecosystems to warming. Furthermore, sensitive indicators of environmental perturbations (ecosystem carbon and water use efficiency) have not been thoroughly integrated into the analysis of temporal ANPP stability. Our results emphasize the interplay between ecosystem resource use efficiency and ANPP fluctuation, particularly in a water-limited ecosystem. This highlights the intrinsic link between ecosystem resource use efficiency and temporal productivity stability.

While our study has identified that the positive effects of warming on ANPP stability tended to decline over time, several unresolved questions persist regarding the underlying processes: (1) Although our study has established a correlation between nitrogen content and the coverage of plant functional group, the precise mechanisms through which soil nutrients influence ANPP stability are yet to be elucidated, (2) The impact of plant-soil-microbial interactions on ANPP stability warrants further exploration and (3) The response of belowground net primary productivity (BNPP) stability to long-term warming has not been adequately examined. Therefore, it is essential to conduct more comprehensive, long-term studies on the dynamics of soil nutrients, microbial properties and resource use efficiency under warming conditions. These types of studies will shed light on the regulatory role of plant-soil-microbe interactions in modulating both ANPP and BNPP stability across different timescales.

Conclusions

We conducted a 10-year in situ manipulative warming experiment that revealed a dual impact of warming on temporal ANPP stability. While warming initially enhanced stability through increased community height, long-term warming reduced sedge cover and ecosystem resource use efficiency (CUE and WUE), thereby diminishing ANPP stability. Our results provide strong evidence that the positive effect of warming on ANPP stability diminishes over time. These findings emphasize that ecosystem resource use efficiency and plant coverage and height play pivotal roles in regulating ANPP stability across different warming durations.

Methods

Study site

The study site was located in the Nagqu National Observation and Experimental Station for Agricultural Environment, Tibet Autonomous Region, China (31.441°N, 92.017°E; 4460 m above sea level). According to the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System, the mean annual temperature in this region from 1980 to 2011 was −0.6 °C, with a mean annual precipitation of 457.6 mm. The predominant grassland type in this area is alpine meadow, characterized by the dominant alpine plant, Kobresia pygmaea (sedge) that exhibited a relative coverage >60%.

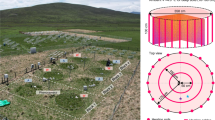

Experiment design

A randomized block design was employed commencing on 2011 that consisted of eight plots and two treatments, each with four replications: ambient and warming. A buffer zone of 1.5 m was maintained between each plot. To simulate warming, open-top chambers (OTC) made by solar radiation-transmitting plastic were utilized that were 0.45 m high, 1.20 m diameter at ground level and 0.65 m in diameter at maximum height. Each OTC was equipped with an electric fan to prevent extreme high temperatures. Throughout the duration of the experiment, no disturbances such as grazing, fertilization or mowing occurred. Following the long-term warming treatment, significant alterations in soil temperature, moisture and plant spatial configuration did occur. Warming resulted in a notable increase in soil temperature accompanied by a decrease in soil moisture. Under warming conditions, plants exhibited an increase in height while simultaneously showing a reduction in coverage (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Date collection

Soil temperature and moisture

MC3 Data Collection System (Tanghua Technology, Beijing, China) was employed to collect data on soil temperature and soil moisture at a depth of 5 cm during growing season (from May to September).

Plant community composition and ANPP

Plant community surveys were conducted at ten-day intervals from May to September in each plot in each year. Coverage of each plant species was assessed using a visual estimation method. The height of each individual plant was measured directly with a ruler. For each species, the heights of five individuals were recorded and the average height was calculated to represent the height of that species. Community coverage was determined through visual estimation. The average height of all species was calculated to represent the overall community height.

To avoid the disturbance of the harvest method on grassland plant communities, a non-destructive method generally used in grasslands was utilized to calculate ANPP as previously described53. We used ANPP in the middle of August in every year to represent annual ANPP.

Temporal stability of ANPP

Temporal stability of ANPP (ANPP stability) was represented by the ratio of temporal mean ANPP (\(\mu\)) to the temporal standard deviation of ANPP (\({{\mathrm{SD}}}\)) for a given period.

As previously reported6, we used the following formula to calculate the temporal standard deviation of ANPP (\({{\mathrm{SD}}}\)) to eliminate effects of sample size on the temporal standard deviation of ANPP as much as possible.

where n is the sample size (the count of ANPP monitored year), xi is the ANPP in year i and \(\bar{x}\) is the arithmetic mean of ANPP over a certain duration. After the calculation, we log-transformed the data to represent the value of ANPP stability in this study. Hence, the ANPP stability was defined as following formula:

We used the formulas above to calculate three types of ANPP stability: (1) cumulative stability (progressively extended periods from initial year, e.g., year 2012–2014, 2012–2015, 2012–2016); (2) sliding-window stability (fixed-length moving intervals, e.g., year 2012–2014, 2013–2015, 2014–2016); and (3) non-overlapping periods stability (discrete consecutive blocks, e.g., 2012–2014, 2015–2017). We employed cumulative ANPP stability in subsequent analyses due to its consistent treatment response and temporal pattern with other stability metrics (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Species asynchrony

Species asynchrony was calculated by following formula:

Where σ represented for standard deviation of total community coverage for a given period and σi represented SD of coverage of species i in a plot during the same given period. Total community coverage was the sum of each species coverage. Notably, this total community coverage (sum of each species coverage) was used in the calculation of species asynchrony. The community coverage (visual estimation) utilized statistical analyses as above. Referring to the calculation of cumulative ANPP stability, we computed species asynchrony over the periods 2012–2014, 2012–2015, 2012–2016…2012–2021, with durations ranging from 3 to 10 years.

Plant group dominance

The plant functional groups were divided into three categories: sedge, grasses and forbs. The dominance of functional group was represented by the importance value (IV) that was calculated by the following formula:

where hi and ci represented the relative height and coverage of each functional group, respectively. We used mean height of species belonged to one functional group to calculate functional group height. The total of coverage of species belonged to one species was calculated to represent functional group coverage.

Species richness

The number of plant species in each plot represented for the species richness of this plot.

Ecosystem carbon and water use efficiency

We measured NEE, ecosystem respiration (ER, the amount of carbon dioxide releasing from plants and soils back to the atmosphere per unit of time)79 and ET to calculate CUE and WUE. NEE, ER, and ET were measured over a period of 90 s every 15 days in a month at 10:00 to 12:00 during each growing season with an Li-6400 portable photosynthesis device (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) in a static chamber (transparent polyethylene chamber, 30 cm × 30 cm × 40 cm). The chamber was uncovered when NEE was measured. The chamber was covered with shade cloth when ER was measured. Detailed methodology of NEE, ER, and ET measurements were reported in our previous study62.

We use the following formula to evaluate the CUE at ecosystem level:

Considering ET integrates transpiration, canopy evaporation, and soil evaporation and reflecting ecosystem water status across plant and soil systems, we quantified ecosystem-level WUE using the established formula33,80:

We calculated June–August averages of NEE, ER, ET, CUE, and WUE to represent growing-season mean values for each year.

Soil sampling and measurements

Soil NH4+-N and NO3--N contents were measured in 2018, 2019, and 2021. Soil sampling was conducted in mid-August with a bucket auger (5 cm diameter) at 0–15 cm depth. Following 2 M KCl extraction of soil samples, NH4+-N and NO3--N were measured using a flow injection auto analyzer (Auto Analyzer 3, Bran Luebbe, Norderstedt, Germany) as previously described81.

Data analysis

Prior to analysis, we tested the normality and homogeneity of data and log-transformed the unsatisfactory data to guarantee their normality and homogeneity. Two-way factor analysis of variances (two-way ANOVA) were used to examine the separate and interactive effects of warming (W) and its duration (D) on ANPP, ANPP stability, species asynchrony and species richness. T-tests were used to compare ANPP, ANPP stability, species asynchrony and species richness under ambient and warming conditions. To assess temporal shifts in warming effects on ANPP stability, we performed two regression analyses: (1) linear regression between warming-induced ∆ANPP stability (warming minus ambient stability) and duration using cumulative and sliding-window metrics; and (2) piecewise linear regression analysis (using segmented package in R software) to detect potential transition points in warming effects over time.

Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the separate and interactive effects of warming (W) and year (Y) on NEE, ER, ET, CUE, WUE, community height, community coverage, sedge coverage, grass coverage and forb coverage. T-tests were used to compare NEE, ER, ET, CUE, WUE, soil NH4+-N, and NO3--N content under ambient and warming conditions. Two-way ANOVA was utilized to analyze the separate and interactive effects of warming (W) and year (Y) on IV of each functional group. To reflect the changes in the steric configuration of each functional group from 2012 to 2021, a linear regression analysis was conducted to describe the correlation between changes in height (∆height), changes in coverage (∆coverage) and changes in the ratio of height to coverage (∆ height/coverage) with respect to the year. The ∆value was calculated as the difference between the values under warming and ambient conditions. Furthermore, linear regression analysis was also employed to examine the relationship between functional group coverage and soil nitrogen contents (NH4+-N and NO3--N).

Given the strong coupling between ecosystem carbon and water fluxes82, we used the first component of the principal component analysis (PCA) results that accounted for 63.3% of the variance in CUE and WUE to represent ecosystem resource (carbon-water) use efficiency (RUE). Pearson correlation analysis was employed to explore the relationship between soil temperature, soil moisture, species richness, species asynchrony, community height, community coverage, sedge coverage, grass coverage, forb coverage, RUE and the average and standard deviation (SD) of ANPP. The trends in the average and SD of ANPP over time were analyzed using a simple linear regression method. A structural equation model (SEM) was developed using Amos 25 (SPSS, Amos Development Corporation, IBM, Chicago, Ill, USA). The model goodness of fit was evaluated based on the P-value (p > 0.05), the Root Mean Square Error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.05), and the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Above variance analysis and PCA analysis were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. Correlation heatmap was made in R software (v4.2.1; http://www.rproject.org/, corrplot package). Figures were made in GraphPad Prism 9.0.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data are available from Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30227257.

Code availability

Code text is available from Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30227257.

References

Bardgett, R. D. et al. Combatting global grassland degradation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 720–735 (2021).

Buisson, E., Archibald, S., Fidelis, A. & Suding, K. N. Ancient grasslands guide ambitious goals in grassland restoration. Science 377, 594–598 (2022).

Valencia, E. et al. Synchrony matters more than species richness in plant community stability at a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24345–24351 (2020).

Zwicke, M. et al. Lasting effects of climate disturbance on perennial grassland above-ground biomass production under two cutting frequencies. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 3435–3448 (2013).

Ma, F. et al. Opposing effects of warming on the stability of above- and belowground productivity in facing an extreme drought event. Ecology 105, e4193 (2024).

Liu, P. et al. Ambient climate determines the directional trend of community stability under warming and grazing. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5198–5210 (2021).

Garnier, A., Pennekamp, F., Lemoine, M. & Petchey, O. L. Temporal scale dependent interactions between multiple environmental disturbances in microcosm ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 5237–5248 (2017).

Wang, N. et al. Effects of climate warming on carbon fluxes in grasslands—a global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1839–1851 (2019).

Walker, T. W. N. et al. A systemic overreaction to years versus decades of warming in a subarctic grassland ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 101–108 (2020).

Wan, Z. et al. Changes in plant species dominance maintain community biomass production under warming and precipitation addition in temperate steppe in Inner Mongolia, China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 341, 109671 (2023).

Liang, M., Liang, C., Hautier, Y., Wilcox, K. R. & Wang, S. Grazing-induced biodiversity loss impairs grassland ecosystem stability at multiple scales. Ecol. Lett. 24, 2054–2064 (2021).

Sasaki, T. et al. Aridity-dependent shifts in biodiversity–stability relationships but not in underlying mechanisms. Glob. Chang Biol. 30, e17365 (2024).

Wan, Z. et al. The stability of aboveground productivity in a semiarid steppe in China is influenced by the plant community structure. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 523 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Temporal asynchrony of plant and soil biota determines ecosystem multifunctional stability. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17483 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Nutrients and herbivores impact grassland stability across spatial scales through different pathways. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 2678–2688 (2022).

Xu, Z., Jiang, L., Ren, H. & Han, X. Opposing responses of temporal stability of aboveground and belowground net primary productivity to water and nitrogen enrichment in a temperate grassland. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17071 (2024).

de Mazancourt, C. et al. Predicting ecosystem stability from community composition and biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 16, 617–625 (2013).

Polley, H. W., Isbell, F. I. & Wilsey, B. J. Plant functional traits improve diversity-based predictions of temporal stability of grassland productivity. Oikos 122, 1275–1282 (2013).

Isbell, F. et al. Biodiversity increases the resistance of ecosystem productivity to climate extremes. Nature 526, 574–577 (2015).

Xi, N., Zhu, B.-R. & Zhang, D.-Y. Contrasting grass nitrogen strategies reflect interspecific trade-offs between nitrogen acquisition and use in a semi-arid temperate grassland. Plant Soil 418, 267–276 (2017).

Liu, Z., Zhang, S., Lock, T. R., Kallenbach, R. L. & Yuan, Z. Aridity determines the effects of warming on community stability in Inner Mongolian grassland. Agric. For. Meteorol. 329, 109274 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Dominant plant functional group determine the response of the temporal stability of plant community biomass to 9-year warming on the Qinghai–Tibetan plateau. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.704138 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Biodiversity stabilizes plant communities through statistical-averaging effects rather than compensatory dynamics. Nat. Commun. 13, 7804 (2022).

Yin, R. et al. Experimental warming causes mismatches in alpine plant-microbe-fauna phenology. Nat. Commun. 14, 2159 (2023).

Migliavacca, M. et al. The three major axes of terrestrial ecosystem function. Nature 598, 468–472 (2021).

Campbell, J. E. et al. Large historical growth in global terrestrial gross primary production. Nature 544, 84–87 (2017).

Manzoni, S. et al. Reviews and syntheses: carbon use efficiency from organisms to ecosystems—definitions, theories, and empirical evidence. Biogeosciences 15, 5929–5949 (2018).

Yang, Z. et al. Decreased precipitation in the late growing season weakens an ecosystem carbon sink in a semi-arid grassland. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 2101–2112 (2021).

Chen, N. et al. Multiple-scale negative impacts of warming on ecosystem carbon use efficiency across the Tibetan Plateau grasslands. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 398–413 (2021).

Sinsabaugh, R. L., Moorhead, D. L., Xu, X. & Litvak, M. E. Plant, microbial and ecosystem carbon use efficiencies interact to stabilize microbial growth as a fraction of gross primary production. N. Phytol. 214, 1518–1526 (2017).

Feng, Z. et al. Variation in and regulation of carbon use efficiency of grassland ecosystem in Northern China. Atmosphere. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15060678 (2024).

Huang, M. et al. Change in terrestrial ecosystem water-use efficiency over the last three decades. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2366–2378 (2015).

Huang, M. et al. Seasonal responses of terrestrial ecosystem water-use efficiency to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 2165–2177 (2016).

Li, P. et al. Deepened snow promotes temporal stability of semi-arid grasslands via improving water acquisition-and-use strategies. Ecology 106, e70105 (2025).

Zeng, N., Niu, Z., Li, P., Zhu, X. & Ren, X. Resistance of grassland productivity to hydroclimatic changes in the Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 143, 109351 (2022).

Shao, W., Guan, Q., Liu, H., Sun, W. & Sun, Y. Temporal and spatial dynamics of carbon and water use efficiency on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau and their ecosystem responses. J. Clean. Prod. 475, 143581 (2024).

Querejeta, J. I., Ren, W. & Prieto, I. Vertical decoupling of soil nutrients and water under climate warming reduces plant cumulative nutrient uptake, water-use efficiency and productivity. N. Phytol. 230, 1378–1393 (2021).

Mao, C. et al. Permafrost nitrogen status and its determinants on the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5290–5302 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. The impacts of climate change and human activities on biogeochemical cycles on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 2940–2955 (2013).

Suonan, J., Classen, A. T., Zhang, Z. & He, J.-S. Asymmetric winter warming advanced plant phenology to a greater extent than symmetric warming in an alpine meadow. Funct. Ecol. 31, 2147–2156 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Shifting plant species composition in response to climate change stabilizes grassland primary production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4051–4056 (2018).

Song, M.-H. & Yu, F.-H. Reduced compensatory effects explain the nitrogen-mediated reduction in stability of an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. N. Phytol. 207, 70–77 (2015).

Huang, M., Liu, X. & Zhou, S. Asynchrony among species and functional groups and temporal stability under perturbations: patterns and consequences. J. Ecol. 108, 2038–2046 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Rotational grazing promotes grassland aboveground plant biomass and its temporal stability under changing weather conditions on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 31, 2662–2671 (2020).

Hudson, J. M. G., Henry, G. H. R. & Cornwell, W. K. Taller and larger: shifts in Arctic tundra leaf traits after 16 years of experimental warming. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 1013–1021 (2011).

Reich, P. B. et al. Effects of climate warming on photosynthesis in boreal tree species depend on soil moisture. Nature 562, 263–267 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. Recovery of plant species diversity during long-term experimental warming of a species-rich alpine meadow community on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Biol. Conserv. 213, 218–224 (2017).

Ma, L. et al. Mowing mitigates the negative impacts of long-term warming on community composition and niche characteristics of alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 55, e03240 (2024).

Lepš, J., Májeková, M., Vítová, A., Doležal, J. & de Bello, F. Stabilizing effects in temporal fluctuations: management, traits, and species richness in high-diversity communities. Ecology 99, 360–371 (2018).

Loreau, M. & de Mazancourt, C. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: a synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 16, 106–115 (2013).

Shi, Z. et al. Dual mechanisms regulate ecosystem stability under decade-long warming and hay harvest. Nat. Commun. 7, 11973 (2016).

Zhu, J., Zhang, Y. & Wang, W. Interactions between warming and soil moisture increase overlap in reproductive phenology among species in an alpine meadow. Biol. Lett. 12, 20150749 (2016).

Ganjurjav, H. et al. Phenological changes offset the warming effects on biomass production in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. J. Ecol. 109, 1014–1025 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Nitrogen addition reduced ecosystem stability regardless of its impacts on plant diversity. J. Ecol. 107, 2427–2435 (2019).

Ashton, I. W., Miller, A. E., Bowman, W. D. & Suding, K. N. Niche complementarity due to plasticity in resource use: plant partitioning of chemical N forms. Ecology 91, 3252–3260 (2010).

Xiang, X. et al. Different fates and retention of deposited NH4+ and NO3− in the alpine grasslands of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111415 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. Nitrogen availability in soil controls uptake of different nitrogen forms by plants. N. Phytol. 245, 1450–1467 (2024).

Elrys, A. S. et al. Global gross nitrification rates are dominantly driven by soil carbon-to-nitrogen stoichiometry and total nitrogen. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 6512–6524 (2021).

Yan, P. et al. The essential role of biodiversity in the key axes of ecosystem function. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4569–4585 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Drought-induced resource use efficiency responses in an alpine meadow ecosystem of northern Tibet. Agric. For. Meteorol. 342, 109745 (2023).

Gang, C. et al. Drought-induced dynamics of carbon and water use efficiency of global grasslands from 2000 to 2011. Ecol. Indic. 67, 788–797 (2016).

Ganjurjav, H. et al. Warming tends to decrease ecosystem carbon and water use efficiency in dissimilar ways in an alpine meadow and a cultivated grassland in the Tibetan Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 323, 109079 (2022).

Milcu, A. et al. Functional diversity of leaf nitrogen concentrations drives grassland carbon fluxes. Ecol. Lett. 17, 435–444 (2014).

Barry, K. E. et al. The future of complementarity: disentangling causes from consequences. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 167–180 (2019).

Jackson, R. B., Sperry, J. S. & Dawson, T. E. Root water uptake and transport: using physiological processes in global predictions. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 482–488 (2000).

Kergoat, L. et al. Impact of doubled CO2 on global-scale leaf area index and evapotranspiration: conflicting stomatal conductance and LAI responses. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 107, ACL 30-31–ACL 30-16 (2002).

León-Sánchez, L., Nicolás, E., Nortes, P. A., Maestre, F. T. & Querejeta, J. I. Photosynthesis and growth reduction with warming are driven by nonstomatal limitations in a Mediterranean semi-arid shrub. Ecol. Evol. 6, 2725–2738 (2016).

Marchin, R. M. et al. Extreme heat increases stomatal conductance and drought-induced mortality risk in vulnerable plant species. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1133–1146 (2022).

Duursma, R. A. et al. The peaked response of transpiration rate to vapour pressure deficit in field conditions can be explained by the temperature optimum of photosynthesis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 189–190, 2–10 (2014).

Grossiord, C. et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. N. Phytol. 226, 1550–1566 (2020).

Urban, J., Ingwers, M. W., McGuire, M. A. & Teskey, R. O. Increase in leaf temperature opens stomata and decouples net photosynthesis from stomatal conductance in Pinus taeda and Populus deltoides x nigra. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 1757–1767 (2017).

Prieto, I., León-Sánchez, L., Nicolás, E., Nortes, P. & Querejeta, J. I. Warming reduces both photosynthetic nutrient use efficiency and water use efficiency in Mediterranean shrubsWarming reduces nutrient use efficiency. Environ. Exp. Bot. 210, 105331 (2023).

Marchin, R. M., Medlyn, B. E., Tjoelker, M. G. & Ellsworth, D. S. Decoupling between stomatal conductance and photosynthesis occurs under extreme heat in broadleaf tree species regardless of water access. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 6319–6335 (2023).

Aparecido, L. M. T., Woo, S., Suazo, C., Hultine, K. R. & Blonder, B. High water use in desert plants exposed to extreme heat. Ecol. Lett. 23, 1189–1200 (2020).

Wei, B. et al. Experimental warming altered plant functional traits and their coordination in a permafrost ecosystem. N. Phytol. 240, 1802–1816 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. Enhanced observations from an optimized soil-canopy-photosynthesis and energy flux model revealed evapotranspiration-shading cooling dynamics of urban vegetation during extreme heat. Remote Sens. Environ. 305, 114098 (2024).

Dai, L. et al. Alpine shrub had a stronger soil water retention capacity than the alpine meadow on the northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 133, 108362 (2021).

Zhang, W. & Zhang, J. Fragmented patch patterns accelerate evapotranspiration: implications for alpine meadow restoration. Ecol. Indic. 177, 113809 (2025).

Liu, Z., Chen, J., Chen, B. & Wang, S. Temperature constraints of terrestrial ecosystem respiration in global biomes. Funct. Ecol. 39, 2135–2148 (2025).

Beer, C. et al. Temporal and among-site variability of inherent water use efficiency at the ecosystem level. Global Biogeochem. Cycles. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GB003233 (2009).

Wei, D., Xu, R., Liu, Y., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Three-year study of CO2 efflux and CH4/N2O fluxes at an alpine steppe site on the central Tibetan Plateau and their responses to simulated N deposition. Geoderma 232–234, 88–96 (2014).

Huang, M.-T. & Zhai, P.-M. Impact of extreme seasonal drought on ecosystem carbon‒water coupling across China. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 15, 914–923 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the Science and Technology Bureau and Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Bureau in Nagqu. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Youth Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Y2023QC08), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171590), the Central Public Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (BSRF202316, Y2025JC12), and the Nagqu Science and Technology Project (NQKJ‒2023‒02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G. and Q.G. designed the research; Z.L., Y.S., and H.L. performed the experiments; Z.L. and H.G. analyzed the data and wrote the draft; G.H., F.Z., M.L., and Q.G. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks José Ignacio Querejeta and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Guiyao Zhou and Mengjie Wang. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Sha, Y., Liu, H. et al. Diminished positive effects of warming on stability of plant productivity over time in an alpine meadow. Commun Earth Environ 6, 972 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02934-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02934-6