Abstract

Glaciers that flow into the ocean lose mass at different rates, even under the same climate, because their response depends on local conditions such as bedrock shape, floating ice, and sea ice. Here we analyze two neighboring glaciers on the western Antarctic Peninsula, Rusalka and Hoek, between 1990 and 2025, using satellite observations of grounding line and calving front positions, sea ice, velocity, and surface elevation. Rusalka Glacier retreated and accelerated rapidly after 2017, when warm deep ocean water reached a downward-sloping bed. In contrast, Hoek Glacier remained stable, grounded on an upward-sloping bed and abutting a small floating ice shelf. At Hoek, summers with more sea ice coincided with less forward movement of the glacier front, underscoring the stabilizing effect of sea ice. Our results highlight how ocean heat, bed topography, and sea ice interact to control glacier change and Antarctic ice loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Antarctic Peninsula (AP) is currently one of the most rapidly warming regions on Earth1,2,3. As a narrow extension of the Antarctic continent projecting into the Southern Ocean, the AP is highly sensitive to climate change, which has exerted direct and substantial impacts on its cryosphere and surrounding environment4,5,6. From the 1950s to 2008, the AP ice shelves lost a total area of more than 28,000 km², accounting for 18% of the earliest recorded floating ice area7. Ice shelves can buttress glaciers feeding into them, which help control the flow of glacial ice into the ocean8,9,10. The IMBIE team found that ice-shelf collapse has increased the rate of ice loss from the AP from 7 ± 13 Gt to 33 ± 16 Gt per year from 1992 to 201711.

The different effects of oceanic and atmospheric drivers promote the dynamic changes of the AP glaciers and largely contribute to the different characteristics of changes on the east and west sides of the AP. On the east coast of the AP, a series of ice shelves, extending from the Prince Gustav Channel to the Larsen B Ice Shelf, have disintegrated over recent decades. The loss of these ice shelves has led to substantial flow acceleration and thinning of the upstream glaciers that formerly drained into them, contributing to increased ice discharge into the Weddell Sea10,12,13,14,15,16. On the northern AP, ice shelf disintegration events have been primarily attributed to enhanced regional climate warming17,18, leading to increased wide-scale surface melt19, crevasse enlargement by hydrofracture20,21,22 and reduced sea ice23.

On the west coast of the AP, glacier dynamics are primarily influenced by oceanic forcing. Warm and saline Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) is prevalent along the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Sea sectors, where its intrusion onto the continental shelf drives high basal melt rates beneath ice shelves, leading to their thinning and enhanced discharge of tributary glaciers24,25,26,27,28,29. While most studies of ocean-driven ice shelf thinning in the western AP have concentrated on the southern sectors of Palmer Land30,31,32, glaciers farther north in Graham Land are typically unbuttressed and terminate directly in the ocean. Davison et al.33 reported a widespread increase in ice discharge from glaciers north of the Arrowsmith Peninsula in the western AP since 2018 and the acceleration in discharge was concentrated at glaciers connected to deep, cross-shelf troughs hosting warm-ocean waters. Moreover, Boxall et al.34 reported a ~ 15% increase in ice velocity near the grounding line of glaciers feeding the George VI Ice Shelf during austral summer, linked to surface meltwater and ocean temperature anomalies35. Similarly, Wallis et al.36 observed summer speed-ups in 105 western AP glaciers, averaging 12.4 ± 4.2% with localized peaks over 22%.

These spatial contrasts between the east and west coasts of the AP underscore the diverse mechanisms through which atmospheric and oceanic forcing impact marine-terminating glaciers. However, regional climatic and oceanic forcing alone cannot fully account for the dynamic responses observed in individual outlet glaciers. Increasing evidence from Greenland highlights the importance of local boundary conditions in modulating glacier sensitivity to external drivers37,38. Factors such as bed topography, the presence of ice shelves or ice mélange, and the extent and persistence of seasonal sea ice have been shown to exert pronounced influence on glacier behavior39,40. A prominent example is provided by two major and neighboring outlet glaciers in northeast Greenland, Zachariæ Isstrøm and Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden Glaciers, whose contrasting evolution underscores the role of these local controls. Zachariæ Isstrøm retreated rapidly and thinned dynamically in recent decades, whereas Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden Glacier remained relatively stable. This disparity has been attributed to differences in bed geometry, the degree of ocean access, and the presence of sustained frontal buttressing provided by a persistent ice shelf and mélange41.

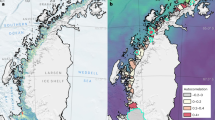

Such compound controls have been extensively studied in Greenland37 but remain less well documented in the AP, where outlet glacier catchments are typically smaller and topographically complex. Improved understanding of these coupled mechanisms is essential for assessing the spatial variability of glacier retreat and for refining projections of regional mass loss and its contribution to sea-level rise under future climate scenarios. Here, we investigate a parallel case to the contrast between the Zachariæ Isstrøm and Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden Glaciers of northeast Greenland by comparing the recent evolution of two adjacent marine-terminating glaciers, Rusalka and Hoek, on the western Antarctic Peninsula (Fig. 1). Despite their close proximity and exposure to similar climatic forcing, the two glaciers exhibit divergent frontal behaviors between 1990 and 2025. To explore the mechanisms behind these contrasting responses, we conduct a comprehensive analysis using multi-source satellite observations, including surface elevation changes (2012, 2014, 2017), calving front positions (1990–2025), grounding line locations (2012, 2014, 2017), sea ice extent (1990–2025), and surface velocity fields (2007–2009, 2016–2024). We also incorporate modelled oceanic and in-situ atmospheric temperature records near the glacier termini to assess environmental drivers. This integrated approach enables us to evaluate the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of glacier dynamics and to examine how bed geometry, ocean access, sea ice variability, and the presence or absence of a floating ice shelf interact to shape glacier-specific responses to climate forcing. Our findings provide insights into the coupled mechanisms driving outlet glacier change in the AP and highlight their relevance for projecting regional ice loss under future climate scenarios.

a Seafloor bathymetry of the Bellingshausen Sea from IBCSO v276 merged with subglacial topography from Huss and Farinotti43. Study sites for oceanographic analysis (blue and orange dashed boxes) and ocean data validation (grey dashed box, after Wallis et al.36) are marked. The red rectangle indicates Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers, and the Faraday/Vernadsky Station (purple triangle) provides surface air temperature data. b, c show close-up views of the Hoek and Rusalka glaciers, illustrating bed topography (from Huss and Farinotti43) and surface elevation (from TanDEM-X DEM, austral winter 2014), respectively. a–c Share the same colorbar for surface elevation and bed topography, as displayed in (a).

Results

Grounding line and calving front change

We estimated the grounding line (GL) using TerraSAR-X add-on for Digital Elevation Measurement (TanDEM-X)42 digital elevation models (DEMs) and subglacial topography, based on the principle of hydrostatic equilibrium. Specifically, we compared the observed above-sea-level surface height from TanDEM-X DEMs with the theoretical height expected under flotation conditions (see Methods 4.2). Assuming that the difference between observed and theoretical heights follows a normal distribution, we computed the probability of flotation, that is, the likelihood that ice at a given location is floating (i.e., the height difference is less than zero). Supplementary Fig. S1 shows flotation probability contours of 0.4 (predominantly grounded, black), 0.5 (marginally floating, magenta), and 0.6 (floating, blue) for the years 2012, 2014, and 2017. We define the region between the 0.4 and 0.6 contours as the grounding zone, where the ice transitions from grounded to floating. In our analysis, the 0.5 contour is used as the representative GL position.

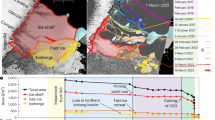

For Rusalka Glacier, the GL remained relatively stable between 2012 and 2014 (Fig. 2a). However, a retreat was observed between 2014 and 2017, with a maximum displacement of approximately 600 m. This retreat exceeds the 95% confidence interval of the estimated GL position [–215 m to +255 m], indicating that the migration is statistically significant and not attributable to measurement uncertainty. In contrast, Hoek Glacier was fronted by a small ice shelf ( ~ 9 km² in 2014), and its GL position varied by less than 200 m over the same period, which falls within the estimated uncertainty range. We therefore consider the GL of Hoek Glacier to have remained unchanged from 2012 to 2017.

a Grounding line (GL) positions in 2012, 2014, and 2017, derived from TanDEM-X DEMs. White solid-line rectangles indicate the boxes used to estimate the area enclosed between the calving front (CF) and the box boundaries for Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers. The white line shows a representative calving front, and the highlighted light blue region denotes the CF box area. The light pink dashed boxes indicate the regions used to measure sea ice extent in front of the two glaciers. The background image is a Landsat 8 optical image acquired on February 2, 2015. b, c Bed topography and corresponding CF and GL positions along the central flowline profiles indicated by the two black lines in (a). d, e Time series of CF box areas and adjacent sea ice extent.

To address the limited availability of GL observations, which are only available for three specific years, we manually delineated calving front positions and sea ice extent near the termini of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers from 1990 to 2025. This delineation was primarily performed during the melt seasons, using Landsat 5/7/8 panchromatic imagery and Sentinel-2 multispectral data. For Rusalka Glacier, the calving front is consistently located near the grounding line across all three TanDEM-X DEM observation dates. The higher temporal resolution of the calving front record offers valuable insights into calving front dynamics over multi-decadal timescales. Figure 2b, c show the calving front (CF) and grounding line (GL) positions superimposed on subglacial topography along the central flowline profiles of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers (Fig. 2a), respectively. For Rusalka Glacier (Fig. 2b), we included only a portion of the time-series calving fronts in the main figure to improve visual clarity; however, it remains challenging to discern the detailed calving front retreat patterns. To address this issue, we present a more comprehensive visualization in Supplementary Fig. S2. All extracted calving front positions are grouped into different time periods and displayed in panels (a)–(c) of Supplementary Fig. S2, while panel (d) highlights several key time points of notable calving front retreat. Along the direction of the black profile line, two distinct phases of rapid calving front retreat can be identified. The first phase extends from the earliest available observation in February 1990 to approximately November 2006, followed by a relatively stable period that lasts until 2016. The second retreat phase begins in 2017 and continues until March 2021, when the calving front stabilizes again. This final position corresponds well with the lowest point of the retrograde slope shown in the bed topography of Fig. 2b. For Hoek Glacier, we show GL positions only for the years 2012, 2014, and 2017. An ice shelf is inferred to exist in front of the glacier, but the corresponding calving fronts are not shown due to the limited coverage of subglacial topography data43. These GLs are located on a prograde (upward-sloping) bed, which likely contributes to their observed stability. The time series of calving front positions for Hoek Glacier is presented in Supplementary Fig. S3.

To quantitatively assess calving front migration, we applied the box method44 by placing two boxes at the termini of the glaciers and calculating the area enclosed between the calving front and the back of each box (Fig. 2a). Additionally, to compare sea ice conditions at the termini of the two glaciers, we defined two equal-sized rectangular regions in front of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers and quantified sea ice coverage within these areas (dashed rectangles in Fig. 2a). This approach allows for a consistent evaluation of the relationship between calving front dynamics and sea ice conditions. Figure 2d, e show the time series of calving front box areas and melt-season sea ice coverage for Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers, respectively, covering 2001–2025. Data from 1990 are omitted in the figures to improve visual clarity. The complete time series, including 1990, are provided in Supplementary Table S1. We observe that the sea ice area in front of Rusalka Glacier more frequently approaches zero compared to that in front of Hoek Glacier. For Hoek Glacier, there are only a few instances when no sea ice remains in front of the glacier, occurring only in February of 1990, 2001, and 2007 before 2020. The most recent occurrences of complete sea ice disappearance in front of both Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers took place during the austral summers of 2023 and 2024, which also coincide with the lowest Antarctic sea ice extents on record45,46. We performed a linear regression between the sea ice areas and calving front box areas after removing the extreme no sea ice events. We excluded rare summers with complete absence of sea ice, because these events may represent exceptional oceanic–climatic anomalies that correspond to distinct dynamical regimes rather than the gradual modulation dominating most of the record. Even when these extreme no–sea-ice events are included, a statistically significant but weaker negative correlation between sea-ice area and the calving-front position of Hoek Glacier remains (r = –0.4, p < 0.05). However, the relationship becomes stronger (r = –0.7, p < 0.05) when these statistical outliers are excluded, suggesting that the presence of sea ice in front of the glacier exerts a stabilizing buttressing effect that suppresses calving-front retreat. The extreme zero–sea-ice cases are, however, also critical for understanding calving-front changes. In particular, during the 2023 and 2024 melt seasons, summer sea ice decreased to zero throughout the season. This complete absence of sea ice, combined with a heavily crevassed and extended ice front, likely led to the pronounced retreat observed after 2023. In contrast, for Rusalka Glacier, the correlation was negligible (r ≈ 0), suggesting that sea ice does not play a major role in controlling terminus position at this glacier.

To further analyze the influence of atmospheric temperature on sea ice extent, we utilized monthly mean surface air temperature data from the Ukrainian Faraday/Vernadsky Station, located on Galindez Island, Argentine Islands Archipelago, extending up to the year 2025. We extracted air temperature data corresponding to the same year and month as the sea ice observations. Additionally, to assess the impact of cumulative air temperature variations on sea ice formation and persistence, we calculated the average temperature over the current month and the preceding N-month period, where N ranges from 0 to 8 (Supplementary Table S2). Our analysis reveals a weak correlation between sea ice extent and monthly mean air temperature in both datasets whether including all samples or excluding zero sea ice cases. However, a stronger negative correlation emerges when using the mean air temperature over the preceding two months (including the current month), with a Pearson correlation coefficient of –0.6 (p < 0.05) in both cases. The strongest correlation (r = –0.7, p < 0.05) is observed when regressing sea ice extent against the mean temperature over the previous four to five months for the dataset excluding zero sea ice cases. These results suggest that sea ice variability in the study region is significantly influenced by multi-month atmospheric temperature trends, highlighting the critical role of cumulative warming in governing sea ice formation and persistence.

In addition to air temperature, this study also attempts to consider the influence of ocean currents on sea ice. Figure 3 presents optical remote sensing images from Landsat 5/7/8 and Sentinel-2 on six randomly selected dates across the observation period, illustrating the calving front positions and sea ice extent of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers at different times. The images reveal that during the melt season, more sea ice is consistently present in front of Hoek Glacier’s ice shelf compared to Rusalka Glacier. To investigate the differences in sea ice formation and persistence between these two neighboring glaciers, we consider two key factors: ocean currents and geographic features. The Antarctic Coastal Current (AACC) is a nearshore circulation system driven by buoyant freshwater input from basal melt and ice sheet runoff47. The AACC flows westward from the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) toward the Amundsen Sea47. The residual sea ice in front of Rusalka Glacier often exhibits a rough arch-like structure, with its concave shape indirectly reflecting the westward flow direction of the AACC. In contrast, Hoek Glacier benefits from natural protection provided by Pripek Point and Camacúa Island, which create a sheltered environment for the Dimitrov Cove, where the glacier terminates. These geographic features help stabilize sea ice, reducing its advection by ocean currents and contributing to its longer persistence. Based on these observations, we infer that the interaction between the AACC and the unique geographic setting of Dimitrov Cove plays a key role in shaping the perennial sea ice distribution in front of these glaciers.

The dotted regions indicate manually delineated sea ice areas in front of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers, within the sample region outlined by the white dashed line. Background images are from (a–d) Landsat 7/8 panchromatic band imagery and (e, f) Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Acquisition dates are shown in each panel (YYYY-MM-DD).

Velocity changes

In this study, our velocity time series spans the periods 2007–2009 and 2016–2024. We selected two flowline-oriented profiles for Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers, respectively (black lines in Fig. 2a), and calculated average velocities within a 300 m-wide buffer centered on each profile. For austral summer velocities after 2016, we computed the mean velocity along each profile using data from December, January, and February. Similarly, austral winter velocities were calculated using data from June, July, and August. For Rusalka Glacier, the profile extends from the interior towards the calving front, covering its frontal grounded ice region. For Hoek Glacier, the velocity profile was placed starting from the upstream of the grounding zone and extending approximately 1.5 km downstream into the ice shelf. We avoided the very front of the ice shelf, as this region is characterized by an irregular geometry and widespread crevassing, indicating a structurally unstable and weakly consolidated ice surface. Moreover, velocity estimates near the calving front are often less reliable because offset-tracking windows may include mélange or open water, iceberg calving between acquisitions can produce spurious signals, and tidal corrections remain imperfect48. By focusing on the inner portion of the ice shelf, we aim to capture more stable and representative velocity signals that reflect glacier dynamics rather than short-term surface disturbances.

We extracted velocity profiles along the central flowlines (black lines shown in Fig. 2a) of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers for both austral summer and winter (Fig. 4). For Rusalka Glacier, panels (a) and (b) show summer and winter profiles, respectively, while panel (c) presents the mean velocity profiles across different years. For Hoek Glacier, panels (d) and (e) show summer and winter profiles, respectively, and panel (f) displays the annual mean of summer/winter velocity profiles. For Rusalka Glacier, we see two acceleration phases in Fig. 4c: one beginning in 2016 and another from 2021 onward. Winter and summer velocities generally followed similar trajectories with seasonal differences in magnitude. For Hoek Glacier, only one acceleration phase starting around 2020 is observed, during which both summer and winter velocities show similar trends but weaker seasonal contrasts than those observed at Rusalka (Fig. 4d). The first acceleration phase of Rusalka coincides with grounding-line and calving-front retreat along a retrograde slope (Fig. 2b). By March 2021, the calving front had reached the bottom of the retrograde slope and remained relatively stable thereafter (Fig. 2b). The continued summer acceleration since 2021 may reflect enhanced sensitivity to atmospheric forcing. Notably, Antarctic sea-ice extent declined sharply from December 2022, reaching record-low conditions throughout 2023 and 202449,50, which, together with shifts in atmospheric circulation, may have contributed to the observed variability. However, further investigation is required to disentangle the mechanisms linking regional climate anomalies to outlet glacier dynamics.

Profiles correspond to the black lines in Fig. 2a, with distance measured from the ocean side. For Rusalka Glacier, each profile starts at the calving front (CF) position of that year, while for Hoek Glacier, profiles start from a fixed oceanward point. a, b Rusalka Glacier: austral summer and winter velocity profiles. c Mean summer (red) and winter (blue) velocities; magenta line denotes the 2007–2009 annual mean. d, e Hoek Glacier: austral summer and winter velocity profiles. f Mean summer (red) and winter (blue) velocities; magenta line denotes the 2007–2009 annual mean.

Surface elevation change rate

Maps of surface elevation change (Fig. 5a, b) were derived from TanDEM-X DEMs acquired during the austral winter (June–July) of 2012, 2014, and 2017. The corresponding hypsometric surface elevation change rates, calculated at 50 m elevation intervals over the periods 2012–2014 and 2014–2017, are presented in Fig. 5c, d, respectively. A quantitative summary of these changes is listed in Table 1. From 2012 to 2014, Rusalka Glacier remained in a state of relative equilibrium, exhibiting minimal variations in both terminus position and surface elevation (Table 1). However, a distinct thinning trend emerged between 2014 and 2017, with mean elevation change decreasing from slightly positive (0.22 m/yr) to –2.12 m/yr (Table 1). The most surface lowering occurred below 250 m in elevation, concentrated towards the glacier front (Fig. 5b, c). A similar pattern was observed for Hoek Glacier, where the grounded frontal section (below 200 m in elevation) showed a more pronounced surface elevation decrease between 2014 and 2017 compared to 2012–2014 (Fig. 5a, b, d). However, despite their geographical proximity, the average thinning rate of Hoek Glacier ( − 0.86 m/yr) during 2014–2017 was much lower than that of Rusalka Glacier ( − 2.12 m/yr) and remained relatively stable compared with the preceding period ( − 0.45 m/yr during 2012–2014).

a SECR map (dh/dt, m/yr) for Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers from July 24, 2012, to July 4, 2014. b SECR map from July 4, 2014, to June 21, 2017. The dotted black lines in (a, b) indicate the estimated GL positions for 2014 and 2017, respectively. c, d Hypsometric SECR profiles binned at 50 m elevation intervals for grounded ice on Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers, along with their respective hypsometric distributions for the two periods. Background: Landsat-8 optical image acquired on February 2, 2015.

The contrasting surface elevation change rates between Hoek and Rusalka Glaciers (Fig. 5) can be partly attributed to the presence of a small ice shelf at Hoek, which is absent at Rusalka. For Rusalka Glacier, the retreat of the grounding line between 2014 and 2017 likely enhanced dynamic thinning, leading to accelerated surface elevation loss compared with the relatively stable period of 2012–2014 (Fig. 5 and Table 1). This first acceleration phase coincided with simultaneous retreat of the grounding line and calving front along a retrograde slope (Fig. 2b), as well as pronounced surface thinning between 2014 and 2017 (Fig. 5b), suggesting a strong coupling between flow acceleration and dynamic mass loss during this period.

Ocean forcing

Given the scarcity of in-situ ocean observations, which do not fully capture the conditions at the glacier front, we utilize the GLORYS12V1 product from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS). This global ocean eddy-resolving reanalysis dataset provides high-resolution (1/12° horizontal resolution, 50 vertical levels) oceanographic variables, including temperature, salinity, currents, sea level, mixed layer depth, and sea ice parameters from the surface to the ocean floor51. The dataset offers both daily and monthly mean fields, covering the 1993 to 2020. The ocean reanalysis data used in this study have been validated against CTD observations from the Palmer LTER campaign52, and additional validation for our study area is provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Based on remote sensing observations, particularly TanDEM-X DEM-derived elevation changes, we divide the study period into two distinct phases: before and after 2014. Accordingly, we process the seawater data for the time intervals: 2009–2014 and 2015–2020, to analyze the potential impact of oceanic variations on glacier dynamics. We mapped the seawater temperature and salinity distribution in a 75 km × 85 km region located at the fronts of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers (outlined by the dashed blue rectangle in Fig. 1a). For each period, we computed the average seawater temperature and salinity by aggregating data across multiple years at different depths while aligning with the corresponding months. The resulting values were then visualized using temperature-salinity (T-S) diagrams (Fig. 6a,b). Our analysis shows that within the upper 100 m, seawater temperature and salinity fluctuate seasonally. However, below approximately 200 meters, the seasonal cycle disappears, indicating more stable oceanographic conditions at greater depths. Notably, during the period 2015–2020, we observe an increase in deep-water temperatures (below ~150 meters), where temperatures rose from below 0 °C to between 0 °C and 1 °C. This warming trend suggests increased oceanic heat availability, which could have implications for basal melting and glacier dynamics in the region.

a Average seawater temperature and salinity maps for the period 2009–2014, corresponding to the region outlined by the blue dashed rectangle in Fig. 1a. b Average seawater temperature and salinity maps for the period 2015–2020, corresponding to the same study area. c Time-series of annual seawater temperature at different depths, derived from the blue dashed rectangle in Fig. 1a, along with the annual mean surface air temperature recorded at Faraday/Vernadsky Station. d Time-series of estimated CDW core water mass depth for January, July, and the annual mean, corresponding to the orange dashed rectangle in Fig. 1a.

To further investigate the rise in seawater temperature below 150 m in front of Hoek and Rusalka Glaciers, we analyzed the annual average seawater temperature anomaly over time, stratified by seawater depth (Fig. 6c). We first evaluated the impact of air temperature on seawater temperature by performing a regression analysis between the annual average air temperature anomaly from Faraday/Vernadsky Station and the annual average seawater temperature anomaly at different depths from 1993 to 2020. The results show a moderate correlation between surface seawater temperature (within ~50 m depth) and air temperature, with the Pearson coefficient decreasing from ~0.6 at 5 m to ~0.4 at 50 m (p < 0.05).

Since the deep seawater ( >100 m) in the Bellingshausen Sea, located on the western coast of the AP, is influenced by the warm CDW53, we extracted the time-series depth variations of the CDW core layer to assess its impact on the seawater in our study area. To analyze the CDW influence, we selected the region marked by the orange dashed rectangle in Fig. 1a, which contains multiple troughs deeper than 700 m and potential CDW inflow channels leading to the ocean in front of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers. The CDW water masses were identified based on the criteria defined by Cook et al. (2016): Temperature (T ≥ 1 °C), salinity (34.5 psu ≤ S ≤ 34.7 psu) and density (27.6 kg·m⁻³ ≤ ρ ≤ 27.9 kg·m⁻³). For the extracted CDW water mass, we calculated the annual mean depth of its core layer and plotted its depth variations over time (Fig. 6d), displaying values for January, July, and the annual mean from 1993 to 2020.

Figure 6d shows shoaling of the CDW core water mass in 1995, 2002, 2010–2011, and 2016–2017, with the most pronounced rise in 2016–2017, when it reached its shallowest depth ( ~ 200 m). After the shoaling of the CDW core in 2016–2017, a subsequent decline is observed, but the core remains at a relatively shallow depth compared to other periods of shoaling. This trend is also reflected in Fig. 6c, where the water temperature at various depths remains relatively high after 2017. The shoaling of the CDW core water mass, which resulted in elevated seawater temperatures and interacted with local bed topography, may have acted as a key trigger for the surface elevation loss observed in glaciers between 2014 and 2017. Notably, the timing of the 2016–2017 shoaling event accompanied by a concurrent increase in ocean temperatures, coincides with a period of accelerated glacier flow. This temporal alignment suggests a potential causal link between subsurface oceanic changes and dynamic glacier response.

Discussion

The dynamic changes of marine-terminating glaciers are widely acknowledged to be sensitive to oceanic forcing, particularly the intrusion of warm CDW onto the continental shelf52,53. Our comparative analysis of Rusalka and Hoek glaciers on west AP highlights how the interaction between warm ocean water and bed topography exerts a differential control on grounding line and frontal retreat. Rusalka Glacier showed a marked retreat of both the grounding line and calving front in 2017, coinciding with the period of increased CDW presence on the continental shelf. This retreat is spatially correlated with a retrograde bed slope, which promotes dynamic instability once the grounding line retreats inland. In contrast, Hoek Glacier, despite being exposed to the same ocean conditions, has maintained a relatively stable grounding line position during the same period. Its stability is largely due to its grounding line being located on a prograde slope, where the upward-sloping bed provides mechanical resistance against retreat. These observations are consistent with previous studies indicating that ocean forcing alone is insufficient to predict dynamic glacier response (e.g., refs. 54,55). Instead, our results highlight the critical role of bed topography, which acts as a gatekeeper modulating glacier sensitivity to external perturbations (e.g., ref. 56). This interpretation is in line with findings from both Greenland and Antarctica (e.g., refs. 37,57), where marine-terminating glaciers were shown to retreat irreversibly only when unfavorable bed geometry promoted instability. Collectively, these results underscore the necessity of incorporating high-resolution bed topography into predictive models of glacier dynamics.

In addition to oceanic and topographic controls, our results reveal that seasonal sea ice plays an important local buffering role in stabilizing glacier calving fronts, particularly for Hoek Glacier. Through manual delineation of the ice front and the surrounding sea ice area in austral summers from 1990 to 2025, we identified a strong negative correlation (R ≈ –0.7, p < 0.05) between sea ice extent and the location of the ice shelf calving front at Hoek Glacier. This suggests that sea ice may suppress calving processes by acting as a mechanical barrier against ice mélange removal, consistent with previous studies that highlighted the stabilizing influence of mélange and seasonal sea ice in fjords (e.g., refs. 58,59,60). Interestingly, this persistent buffering effect is absent at Rusalka Glacier, where summer sea ice often completely vanishes in this region (Fig. 2d). In contrast, Hoek Glacier frequently retains sea ice during the melt season, which appears to contribute to the stability of its calving front. Two key factors are likely responsible for this difference. First, regression analysis reveals a strong negative correlation between sea ice area and the average surface air temperatures of the preceding 4–5 months, suggesting that warmer atmospheric conditions suppress summer sea ice coverage. Second, the asymmetric sea ice distribution may be partially influenced by regional ocean currents. The shape and orientation of residual sea ice suggest that ocean flow may actively displace sea ice away from the Rusalka front. Additionally, local geographic features play an important role. The entrance of Dimitrov Cove, where Hoek Glacier terminates, is partially sheltered by Pripek Point and Camacúa Island, forming a natural barrier that likely inhibits the export of sea ice during summer months. Together, these physical conditions create a micro-environment conducive to persistent sea ice retention in front of Hoek Glacier, providing a seasonal buttressing effect that may delay or limit calving front retreat.

Our study provides a comprehensive analysis of the oceanic and atmospheric forcing mechanisms driving the contrasting dynamic responses of the Rusalka and Hoek glaciers. Overall, our study demonstrates that the dynamics of small marine-terminating glaciers are governed by a combination of regional-scale ocean-atmosphere forcing and local-scale modulators, including bed topography and sea ice. While warm ocean water acts as a widespread external driver, the actual response of individual glaciers is contingent on local conditions. This explains the observed asynchronous behavior of Rusalka and Hoek glaciers, despite their geographic proximity and shared climatic setting.

This localized perspective offers valuable insights into the broader mechanisms controlling the behavior of outlet glaciers draining into the Bellingshausen Sea sector of western Graham Land, Antarctic Peninsula. As Catania et al. (2020)37 argue for Greenland, the future evolution of marine-terminating glaciers depends on the interplay between large-scale climate forcing and local stabilizing mechanisms, with fjord geometry, basal topography, and ice mélange or sea-ice conditions modulating the glacier’s sensitivity to oceanic and atmospheric drivers. Our results underscore that the atmosphere–ocean–glacier system is a complex and interconnected system, where both oceanic and atmospheric forcing must be jointly considered when analyzing glacier dynamics and mass-balance changes, consistent with previous findings that highlighted the coupled influence of atmospheric and oceanic drivers on outlet glacier variability (e.g., ref. 61). A holistic approach is therefore essential for improving models of glacier evolution and for producing more accurate projections of their contributions to future sea-level rise.

Methods

Surface elevation

The TanDEM-X bistatic interferometric data were used for calculating surface elevation change of Rusalka and Hoek Glaciers between two periods: 2012 to 2014 and 2014 to 2017. The parameters of the SAR acquisitions are given in Table 2. We used glacier drainage basins provided by the Glaciology Group at the University of Swansea through the GLIMS database62,63, combined with updated calving front positions extracted from the amplitude images of TanDEM-X data. We used the operational Integrated TanDEM-X Processor (ITP) from the German Aerospace Center (DLR) to process the bistatic SAR data from the individual tracks into so called raw DEMs which are the intermediate time-stamped products generated before DEM mosaicking for the global DEM product64. A recent version of ITP which includes high-resolution reference DEM65 was adopted in our processing by using the 12 m improved TanDEM-X DEM of the AP with corrected phase unwrapping errors as the reference DEM data66. All the TanDEM-X raw DEMs were calibrated to the reference TanDEM-X DEM data based on the elevation offsets on the flat plateau regions. Glacier surface elevation change was computed by differencing TanDEM-X raw DEMs acquired in the same season (austral winter) to reduce the errors that may be induced by the seasonal melt.

To verify the elevation accuracy of the generated TanDEM-X raw DEM data used for calculating surface elevation change, we used the TanDEM-X raw DEMs acquired at neighbouring paths with close acquisition time in 2014 and 2017 for cross validation (Table 2). The data coverage of all the TanDEM-X data and the selected validation regions are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. The statistics of the elevation difference in the overlapping region at the selected stable and flat regions for validation are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

The total volume change and the rate of surface elevation change at 50 m intervals were derived from the DEM differencing and using the glacier basin boundaries and estimated grounding lines. The outliers of elevation difference were removed by specified threshold (mean elevation difference ±3 × standard deviation of elevation difference in each elevation interval) and filled with mean of elevation difference in the same height interval.

Grounding line location and uncertainty estimation

Mapping the grounding line is crucial for assessing ice sheet and glacier stability, but it is a challenging task due to its transient nature as a subglacial feature between grounded and floating ice in marine ice sheets and tidewater glaciers. The most accurate method for measuring the grounding zone is the double differential InSAR (Double-DInSAR) technique67. The ESA Antarctic Ice Sheet Climate Change Initiative (AIS_cci) grounding line product integrates data from multiple satellite missions and employs the Double-DInSAR technique, providing a comprehensive, multi-temporal dataset with high spatial resolution and accuracy. This makes it a valuable tool for monitoring grounding line dynamics across Antarctica. However, when the Double-DInSAR technique is applied to small outlet glaciers on the AP, it faces two major limitations. First, for some fast-flowing glaciers, temporal decorrelation impedes accurate phase retrieval. Second, for glaciers with small drainage basins, the tidal information provided by global tidal models may not accurately represent local variations, affecting the precision of grounding line mapping.

Therefore, we determined the GL based on the principle of buoyancy, utilizing TanDEM-X DEM data and 100-m resolution bedrock topography for the AP north of 70°S43. According to the buoyancy criterion, the GL is identified where the ice is in hydrostatic equilibrium with the underlying ocean. Under the assumption of static equilibrium, the following equations are established:

Here, T represents the ice thickness, hs is the ice shelf freeboard height, Hbed denotes the bed topography, and HHE is the above-sea-level height when the ice is in hydrostatic equilibrium. \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{w}}}}}\) and \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) are the densities of seawater and ice, respectively. We adopted a standard ice density of 917 kg m−3 68. However, impurities within the ice can introduce variations of approximately ±5 kg m−3 69, which we take as the uncertainty in \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\). The global mean density of seawater is 1027 kg m−3, though this value can vary regionally. Following Griggs and Bamber (2011), we assumed an uncertainty of ±5 kg m-3 for \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{w}}}}}\). We extracted the above-sea surface elevation hs from TanDEM-X DEM data, as defined in Eq. (3):

Here, HDEM represents the ellipsoidal height derived from the TanDEM-X DEM, \({H}_{{{{\rm{sea}}}}\_{{{\rm{level}}}}}\) denotes the sea level height, and \({H}_{{{{\rm{firn}}}}}\) is the firn correction value applied to account for the impact of firn air content on surface elevation measurements.

The glacier surface elevation was obtained from TanDEM-X DEM data. At the study site, no laser altimetry data were available for the same acquisition time as the DEM data. Therefore, we performed cross-validation using TanDEM-X DEM data from neighboring orbital paths with similar acquisition times (Supplementary Fig. S4). The mean elevation differences in the overlapping regions between different DEM tiles are less than 0.5 m (Supplementary Table S3). Based on this assessment, we assume an uncertainty of ±1 m for TanDEM-X -derived elevation measurements.

Given that the study area is a relatively small coastal region ( ~15 km in extent), the accuracy of global tidal models is limited in nearshore environments70. Additionally, we find that TanDEM-X DEM provides relatively stable elevation measurements over sea ice in open water. To improve the reliability of our measurements, we estimated the local sea level height directly from a stable open-ocean region within the DEM scene, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. To account for potential uncertainties, particularly due to sea ice interference, we assume an uncertainty of ±2 m in the sea level height estimation. The firn correction value for the study area is approximately 10 ± 5 m, based on the firn correction layer from BedMachine V371.

To assess whether the ice shelf is floating, we compare the observed freeboard height hs with the hydrostatic equilibrium freeboard height HHE, and compute the height anomaly through Eq. (4).

If Δe > 0, the ice shelf is considered grounded; if Δe < 0, it is considered floating. To account for observational and parameter uncertainties, we further estimate the probability of flotation within a probabilistic framework. At each grid point, Δe is influenced by uncertainties in surface elevation, bed topography, density, firn correction, and sea level height. Consequently, Δe is not a fixed value but subject to uncertainty. We assume that this pointwise uncertainty follows a normal distribution with mean \({\mu }_{\varDelta e}\) and variance \({{\sigma }^{2}}_{\varDelta e}\), which is justified because the underlying error sources are commonly regarded as independent random errors. Under this assumption, the probability that the ice shelf is floating can be expressed as in Eq. (5). Importantly, this assumption refers to the uncertainty at each individual grid point rather than to the spatial distribution of Δe across the entire ice shelf.

Here, Φ represents the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. This probabilistic framework enables a more robust classification of grounded versus floating ice by incorporating measurement uncertainties. We define the grounding zone by extracting the contours corresponding to flotation probabilities of 0.4 and 0.6, while the 0.5 contour is used to delineate the GL.

The uncertainty of the GL extracted using the hydrostatic equilibrium method is estimated through Δe / tan β, where β represents the average slope of the grounding zone. The average surface elevation and slope calculated from the TanDEM-X DEM, and bedrock elevation in the vicinity of the grounding zone are about 58 m, 5.8°, and −215 m, respectively. The primary source of uncertainty in GL estimation using the hydrostatic equilibrium method stems from inaccuracies in bed topography data at the grounding zone. Direct measurements of bed topography in grounding zones are challenging, and existing bed datasets are typically constructed by integrating sparse point measurements with interpolation and modeling techniques. We use the bedrock product at 100 m spatial resolution created by Huss and Farinotti43 and assume ±100 m deviation for the bedrock elevation data following the work of Huss and Farinotti43 and Friedl, et al.72. We run a Monte Carlo simulation based on Eqs. (1)–(4), which yielded a mean height anomaly (∆e) of ~2 m with a standard deviation of ~12 m. Therefore, the 95% confidence interval for the estimated GL is about [−215 m, 255 m].

Surface velocity

The quality and availability of remote sensing imagery directly influence the accuracy and reliability of velocity estimations. For the earlier years (2007–2009) in our study, high-quality optical and radar images suitable for velocity extraction were limited. Annually averaged velocity fields for this period were derived from repeat-pass Envisat Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar (ASAR) data provided by the European Space Agency (ESA) using feature tracking73. The launch of Copernicus Sentinel-1A in 2014, followed by Sentinel-1B in 2016, greatly improved the temporal and spatial coverage of satellite observations in polar regions. Owing to their dedicated acquisition strategy, short revisit intervals, and all-weather, year-round radar imaging capability, we were able to derive continuous velocity time series at 6- to 12-day intervals. As a result, monthly averaged velocity fields are available from 2015 onwards. The velocity was retrieved by applying feature tracking techniques using Sentinel-1 synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data acquired in the Interferometric Wide (IW) swath mode74,75.

The accuracy assessment was estimated from the residual velocity in stable regions selected on ice free rock outcrops (Supplementary Figs. S6S7). Here, the resulting mean velocities are 0.05 m/d with the RMSE of 0.04 m/d for all the velocity data used in this work (Supplementary Table S4), which shows a good consistence between all the velocity results.

Calving front location and sea ice area

To analyse the time-series movement of the calving fronts, we manually delineated the terminus positions of the two glaciers using Landsat 5/7/8 panchromatic band images and Sentinel-2 multispectral bands acquired from year 1990 to year 2025. All the images were coregistered to the Landsat 8 panchromatic band image acquired in November 29, 2013 at sub-pixel accuracy. We used the box method to quantitatively evaluate the movement of the calving fronts44 that we put two boxes comprising the fronts of the two glaciers (Fig. 2a).

For a specified time stamp, the area between the calving front and the land-ward border of rectangle is calculated for further analysis. In addition to the calving front positions, the boundaries of the sea ice areas in the sea in front of these two glaciers (inside the light pink dashed box in Fig. 2a) were also manually delineated according to visual interpretation of the optical remote sensing images with glacial expert knowledge. In order to facilitate our comparison of the sea ice area at the front of the two glaciers, we divide this light pink dashed rectangle into two equal parts, each part belonging to one glacier, and estimated the sea ice area within these two parts. We performed regression analysis on calving front area and sea ice area for Rusalka and Hoek glaciers, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). We also performed regression analysis on sea ice extent and mean surface air temperature obtained at the Faraday/Vernadsky station (Supplementary Table S2).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

TanDEM-X bistatic InSAR data were acquired under TanDEM-X science proposal XTI_GLAC7408 and are available upon request from the German Aerospace Center (DLR; dana.floricioiu@dlr.de). The surface velocity time series used in this study were provided by ENVEO IT GmbH and are based on Sentinel-1 SAR data, covering January 2016 to December 2024. Velocity data until December 2021 are publicly available via the ENVEO CryoPortal (https://cryoportal.enveo.at/), while more recent data (post-2022) are available upon request from ENVEO (jan.wuite@enveo.at). Annually averaged surface velocity fields for 2007–2009 were derived from Envisat Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar (ASAR) data provided by the European Space Agency (ESA) and are available upon request from ENVEO. Bedrock topography of the Antarctic Peninsula at 100 m resolution is available at https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-8-1261-2014. Oceanographic variables (temperature, salinity) from 1993 to 2020 are obtained from the GLORYS12V1 global ocean reanalysis product, distributed by the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (https://marine.copernicus.eu/). Monthly mean surface air temperature records for the Faraday/Vernadsky (Akademik Vernadsky) Station (Galindez Island) were obtained from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) station archive: https://www.nerc-bas.ac.uk/icd/gjma/faraday.temps.html. Optical imagery used for glacier front position mapping and sea ice area delineation was acquired from Sentinel-2 and Landsat data, accessed via the Copernicus Open Access Hub (https://scihub.copernicus.eu/) and USGS EarthExplorer, respectively. Calving front positions and sea-ice extent from 1990 to 2025, as well as surface elevation change rate data (2012–2014 and 2014–2017), are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17345769.

References

Jones, M. E. et al. Sixty years of widespread warming in the southern middle and high latitudes (1957–2016). J. Clim. 32, 6875–6898 (2019).

Turner, J. et al. Antarctic temperature variability and change from station data. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 2986–3007 (2020).

Gorodetskaya, I. V. et al. Record-high Antarctic Peninsula temperatures and surface melt in February 2022: a compound event with an intense atmospheric river. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 202 (2023).

Vaughan, D. G. et al. Recent rapid regional climate warming on the Antarctic Peninsula. Clim. Change 60, 243–274 (2003).

Cook, A. J., Fox, A. J., Vaughan, D. G. & Ferrigno, J. G. Retreating glacier fronts on the Antarctic Peninsula over the past half-century. Science 308, 541–544 (2005).

González-Herrero, S., Barriopedro, D., Trigo, R. M., López-Bustins, J. A. & Oliva, M. Climate warming amplified the 2020 record-breaking heatwave in the Antarctic Peninsula. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 122 (2022).

Cook, A. J. & Vaughan, D. G. Overview of areal changes of the ice shelves on the Antarctic Peninsula over the past 50 years. cryosphere 4, 77–98 (2010).

Scambos, T., Hulbe, C. & Fahnestock, M. in Antarctic Peninsula Climate Variability: Historical and Paleoenvironmental Perspectives 79-92 (American Geophysical Union, 2003).

Dupont, T. & Alley, R. Assessment of the importance of ice-shelf buttressing to ice-sheet flow. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L04503 (2005).

Rott, H., Müller, F., Nagler, T. & Floricioiu, D. The imbalance of glaciers after disintegration of Larsen-B ice shelf, Antarctic Peninsula. Cryosphere 5, 125–134 (2011).

The IMBIE team T. I. Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature 558, 219–222 (2018).

Rott, H. et al. Changing pattern of ice flow and mass balance for glaciers discharging into the Larsen A and B embayments, Antarctic Peninsula, 2011 to 2016. Cryosphere 12, 1273–1291 (2018).

Scambos, T. A., Bohlander, J., Shuman, C. A. & Skvarca, P. Glacier acceleration and thinning after ice shelf collapse in the Larsen B embayment, Antarctica. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L18402 (2004).

Rignot, E. et al. Accelerated ice discharge from the Antarctic Peninsula following the collapse of Larsen B ice shelf. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L18401 (2004).

Seehaus, T., Marinsek, S., Helm, V., Skvarca, P. & Braun, M. Changes in ice dynamics, elevation and mass discharge of Dinsmoor–Bombardier–Edgeworth glacier system, Antarctic Peninsula. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 427, 125–135 (2015).

Rott, H. et al. Mass changes of outlet glaciers along the Nordensjköld Coast, northern Antarctic Peninsula, based on TanDEM-X satellite measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8123–8129 (2014).

Scambos, T. A., Hulbe, C., Fahnestock, M. & Bohlander, J. The link between climate warming and break-up of ice shelves in the Antarctic Peninsula. J. Glaciol. 46, 516–530 (2000).

Mulvaney, R. et al. Recent Antarctic Peninsula warming relative to Holocene climate and ice-shelf history. Nature 489, 141–144 (2012).

van den Broeke, M. Strong surface melting preceded collapse of Antarctic Peninsula ice shelf. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L12815 (2005).

Domack, E. et al. Antarctic Peninsula climate variability: historical and paleoenvironmental perspectives. Vol. 79 115-127 (American Geophysical Union, 2003).

Banwell, A. F., MacAyeal, D. R. & Sergienko, O. V. Breakup of the Larsen B Ice Shelf triggered by chain reaction drainage of supraglacial lakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5872–5876 (2013).

Bell, R. E., Banwell, A. F., Trusel, L. D. & Kingslake, J. Antarctic surface hydrology and impacts on ice-sheet mass balance. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1044–1052 (2018).

Massom, R. A. et al. Antarctic ice shelf disintegration triggered by sea ice loss and ocean swell. Nature 558, 383–389 (2018).

Shepherd, A., Wingham, D. & Rignot, E. Warm ocean is eroding West Antarctic ice sheet. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L23402 (2004).

Dutrieux, P. et al. Strong sensitivity of Pine Island ice-shelf melting to climatic variability. Science 343, 174–178 (2014).

Pritchard, H. et al. Antarctic ice-sheet loss driven by basal melting of ice shelves. Nature 484, 502–505 (2012).

Walker, C. & Gardner, A. S. Rapid drawdown of Antarctica’s Wordie Ice Shelf glaciers in response to ENSO/Southern Annular Mode-driven warming in the Southern Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 476, 100–110 (2017).

Jenkins, A. et al. Observations beneath Pine Island Glacier in West Antarctica and implications for its retreat. Nat. Geosci. 3, 468–472 (2010).

Naughten, K. A. et al. Simulated twentieth-century ocean warming in the Amundsen Sea, West Antarctica. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL094566 (2022).

Rignot, E. et al. Recent ice loss from the Fleming and other glaciers, Wordie Bay, West Antarctic Peninsula. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L07502 (2005).

Paolo, F. S., Fricker, H. A. & Padman, L. Volume loss from Antarctic ice shelves is accelerating. Science 348, 327–331 (2015).

Wouters, B. et al. Dynamic thinning of glaciers on the Southern Antarctic Peninsula. Science 348, 899–903 (2015).

Davison, B. J., Hogg, A. E., Moffat, C., Meredith, M. P. & Wallis, B. J. Widespread increase in discharge from west Antarctic Peninsula glaciers since 2018. Cryosphere 18, 3237–3251 (2024).

Boxall, K., Christie, F. D., Willis, I. C., Wuite, J. & Nagler, T. Seasonal land-ice-flow variability in the Antarctic Peninsula. Cryosphere 16, 3907–3932 (2022).

Boxall, K. et al. Drivers of seasonal land-ice-flow variability in the Antarctic Peninsula. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 129, e2023JF007378 (2024).

Wallis, B. J., Hogg, A. E., van Wessem, J. M., Davison, B. J. & van den Broeke, M. R. Widespread seasonal speed-up of west Antarctic Peninsula glaciers from 2014 to 2021. Nat. Geosci. 16, 231–237 (2023).

Catania, G. A., Stearns, L. A., Moon, T. A., Enderlin, E. M. & Jackson, R. H. Future evolution of Greenland’s Marine-terminating outlet glaciers. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 125, e2018JF004873 (2020).

Hanna, E. et al. Short- and long-term variability of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 193–210 (2024).

Cassotto, R., Fahnestock, M., Amundson, J. M., Truffer, M. & Joughin, I. Seasonal and interannual variations in ice melange and its impact on terminus stability, Jakobshavn Isbræ, Greenland. J. Glaciol. 61, 76–88 (2015).

Morlighem, M. et al. BedMachine v3: complete bed topography and ocean bathymetry mapping of Greenland from multibeam echo sounding combined with mass conservation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 11,051–011,061 (2017).

Hill, E. A., Carr, J. R., Stokes, C. R. & Gudmundsson, G. H. Dynamic changes in outlet glaciers in northern Greenland from 1948 to 2015. Cryosphere 12, 3243–3263 (2018).

Krieger, G. et al. TanDEM-X: A satellite formation for high-resolution SAR interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 45, 3317–3341 (2007).

Huss, M. & Farinotti, D. A high-resolution bedrock map for the Antarctic Peninsula. Cryosphere 8, 1261–1273 (2014).

Moon, T. & Joughin, I. Changes in ice front position on Greenland’s outlet glaciers from 1992 to 2007. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surface 113, F02022 (2008).

Gilbert, E. & Holmes, C. 2023’s Antarctic sea ice extent is the lowest on record. Weather 79, 46–51 (2024).

Scott, M. Antarctic sea ice summer minimum ties for second-lowest on record in 2024. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/antarctic-sea-ice-summer-minimum-ties-second-lowest-record-2024 (2024).

Schubert, R., Thompson, A. F., Speer, K., Schulze Chretien, L. & Bebieva, Y. The Antarctic Coastal Current in the Bellingshausen Sea. Cryosphere 15, 4179–4199 (2021).

Rohner, C. et al. Multisensor validation of tidewater glacier flow fields derived from synthetic aperture radar (SAR) intensity tracking. Cryosphere 13, 2953–2975 (2019).

Espinosa, Z. I., Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. & Bitz, C. M. Understanding the drivers and predictability of record low Antarctic sea ice in austral winter 2023. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 723 (2024).

Raphael, M. N., Maierhofer, T. J., Fogt, R. L., Hobbs, W. R. & Handcock, M. S. A twenty-first century structural change in Antarctica’s sea ice system. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 131 (2025).

Jean-Michel, L. et al. The Copernicus global 1/12 oceanic and sea ice GLORYS12 reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 698876 (2021).

Wallis, B. J. et al. Ocean warming drives rapid dynamic activation of marine-terminating glacier on the west Antarctic Peninsula. Nat. Commun. 14, 7535 (2023).

Cook, A. J. et al. Ocean forcing of glacier retreat in the western Antarctic Peninsula. Science 353, 283–286 (2016).

Schoof, C. Ice sheet grounding line dynamics: Steady states, stability, and hysteresis. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 112, F03S28 (2007).

Seroussi, H. et al. Continued retreat of Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica, controlled by bed topography and ocean circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6191–6199 (2017).

Morlighem, M. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilizing ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nat. Geosci. 13, 132–137 (2020).

Frank, T., Åkesson, H., de Fleurian, B., Morlighem, M. & Nisancioglu, K. H. Geometric controls of tidewater glacier dynamics. Cryosphere 16, 581–601 (2022).

Amundson, J. M. et al. Ice mélange dynamics and implications for terminus stability, Jakobshavn Isbræ, Greenland. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 115, F01005 (2010).

Robel, A. A. Thinning sea ice weakens buttressing force of iceberg mélange and promotes calving. Nat. Commun. 8, 14596 (2017).

Burton, J. C., Amundson, J. M., Cassotto, R., Kuo, C.-C. & Dennin, M. Quantifying flow and stress in ice mélange, the world’s largest granular material. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5105–5110 (2018).

Cowton, T. R., Sole, A. J., Nienow, P. W., Slater, D. A. & Christoffersen, P. Linear response of east Greenland’s tidewater glaciers to ocean/atmosphere warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7907–7912 (2018).

Raup, B. et al. The GLIMS geospatial glacier database: a new tool for studying glacier change. 56, 101-110 (2007).

NSIDC, G. a. Global Land Ice Measurements from Space glacier database, http://www.glims.org (2005, updated 2018).

Rossi, C., Gonzalez, F. R., Fritz, T., Yague-Martinez, N. & Eineder, M. TanDEM-X calibrated raw DEM generation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 73, 12–20 (2012).

Lachaise, M., Schweißhelm, B. & Fritz, T. in 2020 IEEE Latin American GRSS & ISPRS Remote Sensing Conference (LAGIRS). 646-651 (IEEE).

Dong, Y. et al. High-resolution topography of the Antarctic Peninsula combining the TanDEM-X DEM and Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA) mosaic. Cryosphere 15, 4421–4443 (2021).

Friedl, P., Weiser, F., Fluhrer, A. & Braun, M. H. Remote sensing of glacier and ice sheet grounding lines: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 201, 102948 (2020).

Benn, D. & Evans, D. J. Glaciers and glaciation. 2nd edition edn, (Routledge, 2014).

Griggs, J. A. & Bamber, J. Antarctic ice-shelf thickness from satellite radar altimetry. J. Glaciol. 57, 485–498 (2011).

Stammer, D. et al. Accuracy assessment of global barotropic ocean tide models. Rev. Geophys. 52, 243–282 (2014).

Morlighem, M. MEaSUREs BedMachine Antarctica, Version 3. In: NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (2022).

Friedl, P., Seehaus, T. C., Wendt, A., Braun, M. H. & Höppner, K. Recent dynamic changes on Fleming Glacier after the disintegration of Wordie Ice Shelf, Antarctic Peninsula. Cryosphere 12, 1347–1365 (2018).

Joughin, I. Ice-sheet velocity mapping: a combined interferometric and speckle-tracking approach. Ann. Glaciol. 34, 195–201 (2002).

Nagler, T., Rott, H., Hetzenecker, M., Wuite, J. & Potin, P. The Sentinel-1 Mission: new opportunities for ice sheet observations. Remote Sens. 7, 9371–9389 (2015).

Wuite, J., Nagler, T., Hetzenecker, M. & Rott, H. Ten years of polar ice velocity mapping using Copernicus Sentinel-1. Remote Sens. Environ. 332, 115092 (2025).

Dorschel, B. et al. The International Bathymetric Chart of the Southern Ocean Version 2. Sci. Data 9, 275 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Y.D. gratefully acknowledges support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42471416, 42474047, and 42171384). L.K. and D.F. acknowledge funding from the Earth Observation Center, German Aerospace Center (DLR) through the Polar Monitor II project, as well as from the ESA Antarctic Ice Sheet Climate Change Initiative (CCI; Contract No. 4000143397/23/I-NB). J.W. acknowledges support from the European Space Agency (ESA) via the Antarctic Ice Sheet Climate Change Initiative (CCI and CCI + ) programs (Contract Nos. 4000112227/15/I-NB and 4000126813/19/I-NB). M.W. acknowledges support from AWI INSPIRES grant and by the DFG project number 542009872.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. designed the study, processed and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. D.F. supervised the project, provided and processed TanDEM-X bistatic InSAR data. L.K. processed and validated surface elevation data. J.Z. processed data and created figures. J.W. processed glacier velocity datasets and contributed to data interpretation. Z.Z. provided expertise on oceanographic data. M.W. provided expertise on bed topography data. All authors contributed to glacier dynamics interpretation and to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Y., Floricioiu, D., Krieger, L. et al. Atmosphere-ocean driven glacial changes in West Graham Land, Antarctic Peninsula. Commun Earth Environ 6, 979 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02939-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02939-1