Abstract

Upwelling systems are critical drivers of regional climate variability, through their influence on ocean–atmosphere interactions and biogeochemical cycles. The Benguela Upwelling System, closely tied to Southern Ocean fronts and Indian-Atlantic water exchange, offers key insights into regional to global climatic shifts. This study analyses evolution of the Benguela Upwelling System during ~11.7 Ma–Holocene, using planktic foraminiferal relative abundance and oxygen and carbon stable isotope analysis from Ocean Drilling Program Site 1087. The data reveal unimpeded flow of Indian Ocean waters into the Southeast Atlantic before the onset of upwelling at ~10 Ma. The upwelling system was fully developed at ~9.8 Ma, which intensified between ~8.0 and 4.8 Ma, aided by strong southeast trade winds. The intense upwelling in Late Miocene Cooling interval triggered and intensified aridification in southern Africa. Upwelling and aridification became decoupled between ~4.8 and 3.7 Ma, coinciding with enhanced interoceanic exchange and the intrusion of warm Angola Current (Benguela Niño-like conditions). The reintensification of upwelling in the Plio-Pleistocene terminated Benguela Niño-like conditions and overshadowed signals of Indian Ocean inflow. Our findings underscore the pivotal role of the Benguela Upwelling System in regulating southern African climate and its linkages with the polar fronts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the climatic and oceanographic changes since the Miocene is crucial to unravelling the drivers of Earth’s climate system. One key event of the Miocene was the expansion of Antarctic ice sheets after ~13.9 Ma1, which reorganised atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns and intensified the equator-to-pole temperature gradient2. This thermal gradient strengthened the trade winds over southwest (SW) Africa, drove coastal upwelling, and triggered the Benguela Upwelling System (BUS) between ~12and10 Ma3,4,5. Several factors, including the position of Southern Ocean fronts, extent of the subantarctic gyre, strength of the Hadley cell, and trade winds control the intensity of the BUS6,7,8,9,10,11. The Hadley cell, with equatorial convection and descent near 30° latitudes, sustains the subtropical high-pressure belt and triggers the southeast (SE) trade winds that drive coastal upwelling in the BUS12 (Fig. 1a). The BUS, among the most productive Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems, extends from 19°S to 34°S along the southwestern margin of southern Africa13,14. South of the BUS, warm Indian Ocean waters penetrate the Southeast Atlantic through the Agulhas Leakage6,15,16, bringing heat and salt and affecting the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)6,9,17,18.

a Schematic presentation of the Hadley cell circulation driving trade winds and coastal upwelling along southwestern Africa, base map created using Google Earth (Map data ©2021 Google). b Location of Ocean Drilling Programme (ODP) Site 1087 C and major surface currents. Base map from Ocean Data View (ODV). Surface currents patterns are based on97. The locations of sediment cores discussed in the text (ODP 108151, ODP Site 108437, ODP Site 108521, ODP Site 108830) are marked. Blue arrows indicate cold surface currents and black arrows indicate warm surface currents. AgC Agulhas Current and AgR: Agulhas Retroflection, AgL Agulhas Leakage, SAC South Atlantic Current, STC Subtropical Convergence, SAZ Sub-Antarctic Zone, BC Benguela Current, AC Angola current, ABF Angola-Benguela Front.

A significant global cooling between ~7.8 and 5.5 Ma, known as the Late Miocene Cooling (LMC), marked a major transition from globally warm to cold climate conditions2,19. During the LMC, widespread aridification and ecological transformations are observed20,21,22,23. Although a decline in atmospheric pCO2 is frequently invoked as a primary driver of the Late Miocene aridification24, regional differences in the timing of aridification suggest that pCO2 alone cannot explain these patterns25. Nevertheless, lower pCO2 levels likely contributed to Antarctic ice sheet expansion and steeper meridional temperature gradients, thereby strengthening atmospheric circulation and wind-driven upwelling2,19,26. These conditions promoted progressive regional aridification, which was, however asynchronous due to local climatic and geographic factors27. Meanwhile, the specific role of upwelling intensification in driving Late Miocene aridification remains poorly constrained. In southern Africa, although initiation of the aridification has been linked to BUS onset3,5, the temporal evolution of the BUS during the Late Miocene and its mechanistic role in shaping southern African climate and ecosystems remain insufficiently understood.

During the early Pliocene warming, the global temperature was ~3 °C above present day, and atmospheric pCO2 was ~400 ppm2,19,28. Extensive ice sheet reduction occurred in both the Northern Hemisphere and Antarctica, accompanied by weaker meridional and zonal temperature gradients1,29. These changes drove poleward migration of Southern Ocean fronts and weakened the SE trade winds11,30. In the Southeast Atlantic, similar ocean-atmosphere configurations are associated with enhanced Agulhas Leakage6,16,17 and Benguela Niño events31. Analogous to Pacific El Niños, Benguela Niños are short-lived, interannual-scale warm events in the Southeast Atlantic, defined by the episodic southward flow of the warm Angola Current, which occasionally extends to 25°S, marked by weakened trade winds and reduced upwelling31. However, this study emphasizes long-term Benguela Niño-like oceanographic patterns (which has previously been put forward as a climate mode by Rosell-Melé et al.32) in the early Pliocene, rather than short-term modern variability. Despite their importance, few studies have investigated potential signals of the Agulhas Leakage and Benguela Niño-like conditions during the early Pliocene warming. Additionally, climate reconstructions for southern Africa during this interval present conflicting arguments. While climate model33 suggests a more humid environment, pollen-based records21 indicate persistent aridity. This discrepancy underscores the need for detailed reconstruction of the BUS to better understand the regional climatic responses to early Pliocene global warmth.

Our study, based on planktic foraminiferal assemblages and stable isotope ratios (δ18O and δ13C), addresses key gaps in understanding the relationship between the evolution of the BUS and regional climate dynamics since the Late Miocene. Planktic foraminifera, which are marine protists with calcareous shells, are highly sensitive to surface water conditions, making them reliable proxies for reconstructing upwelling dynamics. Increased upwelling brings cold, nutrient-rich waters to the surface, causing shift in the foraminiferal assemblages toward cold-water, upwelling-adapted species and resulting in higher oxygen isotope values in their shells. The carbon isotope values provide information about surface productivity linked to nutrient availability. Together, these proxies are valuable for reconstructing past upwelling intensity and paleoceanographic changes, particularly in dynamic systems like the BUS. Despite the advantages, no studies have yet employed these proxies to investigate the BUS evolution since the Late Miocene.

To address this gap, we utilize sediment core samples from ODP Site 1087 C (31°27.9137′S, 15°18.6541′E; 1374 m water depth) (Fig. 1b). This study aims to: (1) reconstruct the temporal evolution of the BUS since the Late Miocene using planktic foraminiferal assemblages and stable isotope values; (2) investigate the links between BUS intensification and southern African aridification; and (3) identify the presence and timing of Benguela Niño-like conditions and Agulhas Leakage signals during warm intervals of the Miocene and Pliocene. Our results reveal that intensified BUS upwelling during the Late Miocene amplified southern African aridification, whereas early Pliocene Benguela Niño–like conditions and Agulhas Leakage intervals modulated regional climate and influenced AMOC variability.

Results

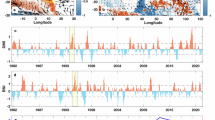

Stable oxygen and carbon isotope records

Figures 2a,b illustrate the δ18O values of Globoconella miotumida (δ18OG. miotumida) and Globigerina bulloides (δ18OG. bulloides); two planktic foraminiferal species with deep dwelling and shallow dwelling habitats, respectively, and provide valuable insights into past variations in seawater temperature. Between ~11.3 and 10 Ma, δ18OG. bulloides averages ~0.36‰, with standard deviation (SD) ± 0.16‰, which during ~10–8.6 Ma increases to 0.52‰, SD ± 0.23‰. Like δ18OG. bulloides, δ18OG. miotumida also exhibits lower values between ~11.7 and 10 Ma. However, in contrast to δ18OG. bulloides, from ~10–9 Ma, the δ18OG. miotumida shows a decreasing trend, from 1.25–0.82‰. The δ18OG. bulloides decreases from ~8.6 to 8 Ma (averaging ~0.18‰, SD ± 0.15‰), which is muted in δ18OG. miotumida. Between ~8 and 5.5 Ma, δ18OG. bulloides exhibits a long-term increasing trend from ~0.12–1.15‰. The δ18OG. miotumida is coupled with δ18OG. bulloides between ~8 and 6.3 Ma showing a long-term increasing trend from ~0.93–1.49‰. However, unlike δ18OG. bulloides, the δ18OG. miotumida exhibits a decreasing trend from ~6.2 Ma. The Miocene-Pliocene transition is marked by a significant decrease in δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OGloborotalia crassaformis, with values remaining low until ~3.7 Ma11. The period between ~3.7 and 2.5 Ma is characterised by a long-term increase in δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OGloboconella inflata. Afterwards, during 2.5–0.9 Ma, no marked correlation is seen in the δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OG. inflata. Finally, from ~0.9 Ma to the Holocene, a pronounced long-term decrease in both δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OG. inflata is evident11. Detailed statistical results supporting these observations are provided in the Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3. Figure 2c, d display the δ13C values of G. miotumida (δ13CG. miotumida) and G. bulloides (δ13CG. bulloides), respectively. Between ~7.7 and 6.5 Ma, both records show a gradual decrease. The δ13CG. bulloides decreases from ~1.03 to ~−0.68‰ and δ13CG. miotumida decreases from ~1.7 to ~0.84‰.

a the δ18O (‰) values of deep-dwelling planktic foraminifera (G. miotumida between 11.7 and 5.6 in brown, G. crassaformis between 5.6 and 3.9 Ma in purple and G. inflata between 3.9 and Holocene in red), (b) the δ18O (‰) values of shallow-dwelling planktic foraminifera (G. bulloides in black), (c) the δ13C (‰) values of deep-dwelling planktic foraminifera (G. miotumida between 11.7 and 5.6 in brown, G. crassaformis between 5.6 and 3.9 Ma in purple and G. inflata between 3.9 and the Holocene in red), (d) the δ13C (‰) values of shallow-dwelling planktic foraminifera (G. bulloides in black), (e) Stacked Sea Surface Temperature (SST) anomalies2 for southern hemisphere mid-latitudes (green), northern hemisphere high latitudes (light blue), northern hemisphere mid latitudes (navy blue), and tropics (red). Isotope (δ18O and δ13C) records between 6.1 Ma and the Holocene are obtained from Mohanty et al.11. Five-point running average plots are superimposed on a–d. Dotted bar indicates the timing of initiation of the BUS, Blue bars indicate intervals of cooling and yellow bar represents warm interval.

Trends in cooler- and warmer-water species

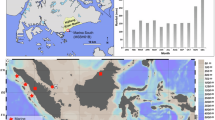

According to habitat preferences, the planktic foraminiferal species are grouped into cooler-water and warmer-water species (see Methods, Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Table 1). The major cooler-water species contributors are Neogloboquadrina acostaensis, Neogloboquadrina pachyderma, Neogloboquadrina incompta, G. bulloides, and Globoturborotalita woodi, while the major warmer-water species contributors include Globorotalia menardii, Trilobatus sacculifer, G. miotumida, Globoconella puncticulata, G. inflata, G. crassaformis, Globigerina falconensis, and Globigerinoides ruber. Minor contributors are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Figure 3a displays the relative abundances of the cooler- and warmer- water species. Between ~11.7 and 10 Ma, warmer-water species dominate, averaging ~75%, while cooler-water species remain scarce. Afterwards, during ~10−8.6 Ma, warmer-water species show a decreasing trend from ~56.6−19.3% and cooler-water species increase from ~16.2−65.5%. The warmer-water species again increase from ~19.3−60.6% between ~8.6 and ~8 Ma, simultaneously cooler-water species decrease from ~65.7−29.2%. During ~8 to 4.8 Ma, the warmer-water species decrease significantly from ~60−17%. Simultaneously, the relative abundance of cooler-water species shows a prominent long-term increasing trend from ~30−75%. With an abrupt drop at ~4.8 Ma, the cooler-water species show lower relative abundance between ~4.8 and 3.7 Ma11, averaging ~34%, while warmer-water species increase in abundance, averaging ~58%. From ~3.7 to 3 Ma, the relative abundance of warmer-water species shows a prominent decreasing trend from ~64–17%, while the cooler-water species increase from ~27−77%. Between ~3 and 2 Ma, cooler-water species remain dominant over warmer-water species11. Statistical tests confirming these patterns are given in the Supplementary Note 1 and illustrated in Supplementary Figures 4–6. The ecological preferences and trends of major planktic foraminiferal species are described and illustrated in Supplementary Note 1 and 3 and in Supplementary Fig. 7.

a Relative abundance of warmer-water (orange) and cooler-water species (blue), (b) Grass-pollen (%) considering the total pollen and spore sum from ODP Site 1081 (blue)51 and ODP Site 1085 (green)21 and (c) UK’37-derived SST (°C) record from ODP Site 1085 (magenta)5 and ODP Site 1087 (purple)69, (d) pCO2 proxy data compilation obtained from variety of different methodologies (https://paleo-co2.org) (references cited in Methods). Relative abundance (warmer and cooler water species) records between 6.1 Ma and the Holocene are obtained from Mohanty et al.11. Five-point running average plots are superimposed on (a, b) and thirty-point running average plots are superimposed on (d) (SST 1087) with dark lines. Dotted bar indicates the timing of initiation of the BUS, grey bar represents the LMC and blue bar represents the Late Miocene intensification of the BUS.

Discussion

Warmer Southeast Atlantic Ocean and enhanced Agulhas Leakage from ~11.7–10 Ma

The lower δ18OG. miotumida and δ18OG. bulloides, along with higher relative abundance of warmer-water species in the early Late Miocene (~11.7–10 Ma), suggest a warmer Southeast Atlantic Ocean relative to the subsequent interval (~10-8.6 Ma) (Figs. 2a, b and 3a). This is further substantiated by the SST data from ODP Site 10855 (Fig. 3c). We attribute this to a poleward shift of Southern Ocean fronts and an expanded South Atlantic gyre, which suppressed trade winds and prevented upwelling (Fig. 4a). Such changes likely facilitated vigorous influx of Indian Ocean waters into the Southeast Atlantic. Higher relative abundances of G. menardii and T. sacculifer, both key indicators of Agulhas Leakage16, also support our proposition (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). Moreover, these warm conditions may have favoured the proliferation of G. falconensis within the BUS, consistent with lower δ18O values (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b, d). While the enhanced Agulhas Leakage amplifies the AMOC by transporting both heat and salt to the North Atlantic6,9,17,18, the open or partly restricted Central American Seaway (CAS) in the early Late Miocene allowed Pacific-Atlantic water exchange34. This exchange would have lowered Atlantic salinity and, in turn, weakened the AMOC. Therefore, we speculate that although the Agulhas Leakage contributed to higher Atlantic water density through salt transport, the open CAS likely counteracted this effect.

a ~11.7-10 Ma, (b) ~10-4.8 Ma, (c) ~4.8-3.7 Ma, (d) ~3.7-2 Ma, and (e) ~2 Ma to the Holocene. Yellow star represents our study site ODP 1087, fire symbols indicate fire activities51 and large mountain symbols in (a−e) indicate high elevation of Drakensberg Escarpment54. The boldness of the black arrows indicates the strength of the trade winds, whereas the boldness of the blue arrows illustrates the strength of the Benguela Current (BC). AgC Agulhas Current, AgR Agulhas Retroflection, AgL Agulhas Leakage, BC Benguela Current, AC Angola Current, SAF Subantarctic Front. Base map created using Google Earth (Map data ©2021 Google).

Initiation of the Benguela upwelling system at ~10 Ma

A pronounced increase in the δ18OG. bulloides, coupled with increased relative abundances of cooler-water species, dominantly N. acostaensis and N. pachyderma (Figs. 2b and 3a; Supplementary Fig. 7f, g), mark the onset of the BUS at ~10 Ma, which was fully developed by ~9.8 Ma. Concurrently, warmer-water species, including G. miotumida and G. falconensis, decline sharply (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). We attribute the onset of upwelling to a northward shift of Southern Ocean fronts, a strengthening of the South Atlantic high-pressure system and strong SE trade winds (Fig. 4b). Our proposed timing of initiation of the BUS aligns well with previous studies3,4,5. The onset of upwelling likely reduced the moisture supply to the adjacent landmass, triggering the establishment of the Namib Desert and aridification in southern Africa35.

Between ~10 and 8 Ma, the δ18OG. miotumida and δ18OG. bulloides differ markedly (Fig. 2a, b), reflecting distinct changes in surface and subsurface waters. Between ~10 and 8.6 Ma, the δ18OG. bulloides increases sharply, indicating surface cooling and stronger upwelling in the BUS, consistent with the SST records from ODP Site 1085 (Figs. 2b and 3c). In contrast, δ18OG. miotumida shows an unexpected decrease. This decrease cannot be attributed to subsurface warming, as subsurface temperature records from ODP 1085 indicate cooling5, which would have increased δ18OG. miotumida. Since the δ18O in foraminiferal calcite is influenced by temperature and salinity, a reduction in salinity driven by increased freshwater input may lower the δ18O signature. We suggest that this might reflect an enhanced contribution of Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) to the BUS subsurface waters36,37. Formed at the Antarctic Convergence under high precipitation and sea-ice melt, AAIW is relatively fresh and isotopically light26,38,39, and its greater influence would therefore lower δ18OG. miotumida. This interpretation is consistent with Rommerskirchen et al.5, who documented enhanced AAIW inflow to the Cape Basin during this interval.

Planktic foraminiferal data suggest that the upwelling-driven cooling persisted between ~10 and ~8.6 Ma, before a warming event disrupted it during ~8.6–8 Ma. The surface warmth is marked by a sudden decrease in the δ18OG. bulloides, coupled with sharp increase in the relative abundance of warmer-water species, which is dominated by G. falconensis and T. sacculifer (Figs. 2b and 3a; Supplementary Fig. 7d). A similar increase in T. sacculifer is seen in the Subantarctic zone (ODP 1088)30. This could be due to the expansion of oligotrophic waters in the Southeast Atlantic, driven by expanded South Atlantic gyre, diminished trade winds, and poleward shift of Southern Ocean fronts. These conditions may have allowed enhanced Agulhas Leakage, as evidenced by the higher relative abundance of T. sacculifer and G. falconensis (Supplementary Fig. 7d). However, the δ18OG. miotumida shows a modest decrease between ~8.6 and 8 Ma (Fig. 2a), implying that subsurface warming was likely less intense than surface warming. Reduced wind stress and weakened upwelling may have enhanced stratification and suppressed vertical mixing, restricting downward penetration of warm surface waters. This vertical decoupling likely resulted from distinct surface and subsurface processes during this interval.

Intensification of upwelling and aridification in southern Africa during the Late Miocene Cooling (~8–5.5 Ma)

After ~8 Ma, the relative abundance of warmer-water species, notably G. miotumida and G. falconensis, decreases significantly (n = 158, p < 0.001), while cooler-water species, dominated by N. pachyderma and N. acostaensis, increase, a trend that persisted until ~4.8 Ma (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Figs. 7c–g). Meanwhile, the δ18OG. bulloides gradually increases from ~8 to 5.5 Ma (Fig. 2b). Together, faunal and isotope records suggest that unlike the warmer conditions of the early Late Miocene, the ~8-5.5 Ma interval was marked by progressive cooling and increased productivity, reflecting intensification of the BUS. In addition, the increasing δ18OG. bulloides may also indicate early Northern Hemisphere ice buildup. Notably, prominent δ18OG. bulloides maxima between ~6.0 and 5.5 Ma coincide with the ephemeral Northern Hemisphere glaciation2,19,26 (Fig. 2b), indicating a broader global influence on the BUS. The δ18OG. miotumida also follows a similar increasing trend like δ18OG. bulloides, but starts to decline after ~6.2 Ma (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). A decoupling between the δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OG. miotumida during ~6.2 to 5.5 Ma reveals simultaneous surface cooling and subsurface warming in the BUS. Similar subsurface warming in the Benguela region was also observed by Rommerskirchen et al.5, who attributed it to weakened NADW formation during the Messinian Salinity Crisis due to reduced salt transport into the Atlantic.

The decrease of global SST between ~8 and 5.5 Ma, referred to in existing publications as the LMC2,23, is clearly evident in our isotope records (Fig. 2a–e). This cooling phase strengthened the Hadley cell, steepened the equator-to-pole temperature gradient, and shifted Southern Ocean fronts northward2,19,26. Such atmospheric changes likely intensified trade winds over the Southeast Atlantic, enhancing upwelling in the BUS. Wu et al.40 noted that enhanced ocean overturning increased nutrient delivery to upwelling regions during this interval. Such nutrient supply to the intensified BUS potentially increased productivity, as indicated by the increasing relative abundance of N. acostaensis and N. pachyderma (Supplementary Fig. 7f, g). This elevated regional productivity coincided with the Late Miocene Biogenic Bloom (LMBB), a global increase in marine productivity associated with higher nutrient levels, driven by factors such as altered oceanic and atmospheric circulation41, gradual shoaling of the Isthmus of Panama42, initiation of the Indian Monsoon System43, and enhanced riverine input from mountain uplift44,45. Diester-Haass et al.4 linked the enhanced productivity in the BUS during the LMBB exclusively to elevated global nutrient levels, ruling out regional upwelling as factor. In contrast, we argue that the intensified regional upwelling was likely a critical driver of increased productivity in the BUS. Our interpretations align with previous studies40,46, who suggested that during the LMBB, intensified upwelling itself significantly increased productivity in upwelling regions.

The widespread cooling during the LMC across ocean basins indicates a global driver, perhaps linked to the declining atmospheric pCO2 to a critical threshold (below ~280 ppm)2,19,23,26,47 (Fig. 3d). This decline, driven by intensified rock weathering and reorganisations in ocean circulation41,48, not only contributed to global cooling but also triggered profound terrestrial responses. Across Asia, Africa, and Australia, the LMC was associated with extensive aridification and vegetation shifts20,22,23,24,49. During this time, grasslands expanded globally, and C4 plants, which are better adapted to low pCO2 and arid conditions, gradually replaced C3 plants22,24. This underlines the crucial role of atmospheric pCO2 in driving the Late Miocene vegetation shift. However, contrasting evidence from other studies suggests no link between Late Miocene C4 plants expansion and pCO2. Instead, they have attributed this vegetation shift to factors like tectonic and oceanographic changes, gradual aridification, seasonal precipitation shifts, altered hydrological conditions, and increased fire activity20,50,51. Regardless of its primary driver, the expansion of C4 plants likely contributed a global transfer of 13C from the marine to the terrestrial carbon pool20,24. This coincided with a major decline in global benthic and planktic δ13C, known as the Late Miocene Carbon Isotope Shift (LMCIS)19,41,44,52. Consistent with this, our record shows a marked decline in δ13CG. miotumida and δ13CG. bulloides between ~7.7 and 6.5 Ma (Fig. 2c, d), which we interpret as a regional response to this global event. The vegetation shifts and increased wind strength caused intensified erosion, mobilising organic-rich, 13C-depleted soils into rivers and ultimately the oceans. This contributed to the LMCIS and supplied nutrients that further fuelled the LMBB53. Dupont et al.21 proposed that around 8 Ma, a shift in the primary moisture source from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, along with changes in summer rainfall patterns, triggered increased aridification in southwest Africa, which was further reinforced by fire activity51 (Figs. 3b and 4b). Meanwhile, in southern Africa, the expansion of C4 plants at ~8 Ma21,51 (Fig. 3b), closely coincides with our proposed timing of BUS intensification. Between ~8 and 5.5 Ma, the enhanced cold water upwelling along the west coast of southern Africa is marked by the higher δ18O values and increased abundance of cooler-water species including N. pachyderma, N. acostaensis and G. bulloides (Figs. 2a, b and 3a; Supplementary Fig. 7e–g) This upwelling probably diminished the moisture-holding capacity of the adjacent air masses, thereby altering regional precipitation pattern. Concurrently, stronger SE trade winds further limited the inland flow of Atlantic moisture transported by westerlies, which shifted the main moisture source from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean21. The westward transport of Indian Ocean moisture was also hindered by major topographic barriers (Fig. 4a), particularly the Drakensberg Escarpment (a high-elevation terrain in southeastern Africa that divides the high interior plateau from the lower coastal plains) and the high relief of eastern Africa, both of which exacerbated regional moisture deficit54,55. We propose that while global pCO2 decline contributed to overall climate cooling during the LMC, the intensified BUS exerted a more direct influence on southern African climate. Regionally, upwelling led to pronounced cooling and increased moisture deficit, acting as the primary driver of widespread aridification and the expansion of C4 vegetation in southern Africa, whereas declining pCO2 likely played a marginal role.

Reversal of the Late Miocene Cooling during the early Pliocene warming (~5.5–3.7 Ma)

While the Late Miocene conditions may have temporarily supported the Northern Hemisphere ice sheets, the lack of sustained higher δ18O values and lower global SST anomaly2 (Fig. 2a–e) suggest that the LMC did not lead to permanent Northern Hemisphere glaciation. Instead, much of the cooling probably reversed during the early Pliocene warming2. After ~5.5 Ma, the marked decrease in the δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OG. crassaformi, along with increased global SST anomaly, imply that the LMC halted near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. Despite this global warming trend after ~5.5 Ma, productivity in the BUS remained high until ~4.8 Ma, as evidenced by the higher relative abundance of N. acostaensis and N. pachyderma (Supplementary Fig. 7f, g). These findings suggest that although the LMBB in the BUS was initially contemporaneous with lower SSTs during the LMC, it probably was not solely dependent on cooler temperatures. At ~4.8 Ma, a sharp decrease in the relative abundance of N. acostaensis and N. pachyderma (Supplementary Fig. 7f, g) signals reduced productivity and termination of the LMBB in the BUS.

Between ~4.8 and 3.7 Ma, warm climatic conditions prevailed in the BUS. This is evidenced by the lower δ18OG. bulloides and δ18OG. crassaformis, elevated global SST anomalies2, and higher relative abundance of warmer-water species (Figs. 2a–e and 3a). Across the Miocene-Pliocene boundary, G. miotumida became extinct and was replaced by another warmer-water species, Globoconella puncticulata, which dominates between ~4.8 and 3.7 Ma (Supplementary Fig. 7c). The relative abundance of G. falconensis, which constantly decreases throughout the LMC, shows significant increase in this interval (n = 58, p < 0.001, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 7d). Conversely, cooler-water species, primarily Neogloboquadrina incompta and N. pachyderma, show lower relative abundances (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7f, g). Collectively, this evidence points to a transition from long-term cooling in the LMC to significant warming and reduced upwelling during the early Pliocene in the BUS.

Higher abundance of warm-water diatoms in the central Benguela in the early Pliocene37 further support the interpretation of warmer conditions. Similar reduced upwelling in other Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems56 implies a global forcing mechanism. The reduced meridional SST gradient expanded the Hadley cell, which weakened the subtropical high-pressure systems and trade winds57. Simultaneously, an expanded Pacific warm pool limited the heat release at high latitudes, deepening the global thermocline and enhancing global warming58,59. Additionally, the elevated pCO2 levels (~400 ppmv) during the warm Pliocene28 likely amplified global warming through atmospheric heat retention60.

Rosell-Melé et al.32 suggested the presence of Benguela Niño-like conditions during the early Pliocene warming. Our data from ODP Site 1087 C show an anomalously high relative abundance of G. crassaformis during this interval (Supplementary Fig. 11c). As G. crassaformis serves as an indicator of warm Angola Current in the BUS10, its increased relative abundance suggests a southward shift of the Angola-Benguela Front, extending the Angola Current further south. Previous studies31,61 on modern Benguela Niños similarly report southward intrusions of the warm, nutrient-poor Angola Current. Thus, our data reveals that oceanographic conditions in the BUS during the early Pliocene warming were analogous to a persistent Benguela Niño-like state. Furthermore, Mohanty et al.11 reported that during this interval, the BUS experienced both surface and subsurface warming, linked to weakened trade winds and sustained deep thermocline, features consistent with modern Benguela Niños.

During the early Pliocene warming, the Antarctic ice sheets retreated29, Southern Ocean fronts shifted poleward30, and the Agulhas Current warmed extensively62. Simultaneously, Site 1087 C records show a significant increase in the relative abundance of warmer-water species G. falconensis (n = 58, p < 0.001, Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Fig. 7d), coinciding with the potentially enhanced Agulhas Leakage into the BUS11. We propose that the intrusion of warm Indian Ocean waters may have created favourable ecological conditions for G. falconensis to flourish in the BUS. Meanwhile, the closure of the CAS reached a critical threshold, supporting a strong AMOC and North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) formation63. Since the increased Agulhas Leakage also enhances these processes6,9,15, we hypothesise that amplified Agulhas Leakage may have acted in support of CAS closure to reinforce AMOC and NADW formation during the early Pliocene warming. This interpretation agrees with studies that associate increased Agulhas Leakage with AMOC intensification during the Late Pliocene9,18, and is further corroborated by Pleistocene records6,17.

Climate models predict wetter conditions in southern Africa during the early Pliocene33. However, palynological evidence instead indicates that aridity increased in the region21. This apparent discrepancy may be explained by a poleward shift of the westerlies64,65, reducing the transport of Atlantic-derived moisture into southern Africa12. Furthermore, with the main moisture source having already shifted from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean21, moisture delivery to southern Africa was likely further reduced. This moisture deficit was likely further amplified by the Drakensberg Escarpment54 and the elevated relief of eastern Africa55. Concurrently, the tectonic constriction of the Indonesian Gateways cooled the Indian Ocean, diminishing moisture transport to East Africa66 (Fig. 4c). Although weaker upwelling in the BUS would typically promote more humid conditions, the combined effects of altered wind patterns, shifting moisture sources, and topographic factors overpowered this influence, resulting in sustained aridification. Thus, we propose a decoupling between upwelling in the BUS and aridification in southern Africa during the early Pliocene warming.

Termination of early Pliocene warming and re-establishment of upwelling during Plio-Pleistocene cooling (~3.7–2.0 Ma)

The early Pliocene warming may have ended due to the significant effect of Ocean gateway closure and the emergence of cold waters in the upwelling regions56,58. In the BUS, this is marked at ~3.7 Ma by significant increase in the δ18OG. inflata (n = 69, p < 0.001) and δ18OG. bulloides (n = 67, p < 0.001), coupled with a decrease in warmer-water species (Figs. 2a, b and 3a; Supplementary Note 1). The simultaneous increase in cooler-water species underscores the re-establishment of upwelling (Fig. 3a). The decrease in the relative abundance of G. crassaformis after ~3.5 Ma (Supplementary Fig. 11c) suggests a northward shift of the Angola Current. We hypothesise that the increasing meridional temperature gradient, intensified trade winds, and subsequent cold water upwelling in the BUS likely terminated widespread Benguela Niño-like conditions.

At ~3.3 Ma, extensive Antarctic glaciation triggered a northward shift of Southern Ocean fronts9, likely increased the influx of cold, nutrient-rich AAIW into the BUS. This is indicated in our data by the increased δ18OG. inflata and δ18OG. bulloides, along with the significantly higher relative abundance of cold-water species (n = 40, p < 0.001, mostly N. incompta and N. pachyderma) (Figs. 2a, b and 3a; Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Figs. 7f, g). Moreover, the northward migration of Southern Ocean fronts may have effectively reduced Agulhas Leakage, which is reflected in the lower relative abundance of G. falconensis. Furthermore, the restriction of the Indonesian Throughflow (ITF) between ~4 and 3 Ma diminished the heat transport via the Agulhas Current to the South Atlantic66 (Fig. 4c). The combined effects of reduced Agulhas Leakage and diminished heat transport might have weakened the AMOC9,63, possibly setting the stage for the impending Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

Mohanty et al.11 proposed that following the early Pliocene warming, the BUS evolved into a stronger upwelling regime between ~3.7 and 3.0 Ma. The emergence of strong upwelling in the BUS and in other Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems appears to have occurred before the establishment of permanent Northern Hemisphere glaciation11,56. Between ~3 and 2 Ma, the BUS experienced prolonged upwelling activity11, coinciding with significant deposits of Southern Ocean diatom in the BUS, referred to as the Matuyama Diatom Maximum37. During this interval, contrasting findings have been reported regarding the strength of the BUS7,11. Our benthic foraminiferal abundance data show a notably higher relative abundance of Uvigernia spp. during this time (Supplementary Fig. 12c), suggesting enhanced productivity in the BUS, consistent with Mohanty et al.11. Peak upwelling occurred between ~2.2 and 2.0 Ma, indicated by a higher relative abundance of N. pachyderma (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Meanwhile, the upwelling expanded into the central and northern Benguela regions between ~ 2.4 and 2 Ma7,37, implying both intensification and spatial expansion of the BUS. The associated cooling of climate induced by this upwelling likely further amplified the aridification in southern Africa67,68.

Modern upwelling condition in the BUS since ~2 Ma

Since ~2 Ma, N. incompta has been the dominant Neogloboquadrina species while N. pachyderma has remained low (Supplementary Fig. 7f, g). Alternating high abundance of N. incompta and low abundance of G. inflata, and vice versa (Supplementary Fig. 7c, f), indicate unstable upwelling strength at Site 1087 C, marking the initiation of long-term marginal upwelling11. After ~1.5 Ma, northern BUS sites (ODP 1084 and ODP 1081) exhibit higher alkenone concentrations and lower SSTs than the southern site (ODP 1087)7,69. This marked the development of two quasi-independent upwelling systems: the southern BUS (SBUS) and the northern BUS (NBUS)11,69. Increased relative abundance of N. incompta from ~1.5 to 0.8 Ma (Supplementary Fig. 7f) suggests higher productivity. However, the lower relative abundance of N. pachyderma implies the supply of nutrients from distant upwelling regions.

Between ~0.9 Ma and the Holocene, warmer SST and lower relative abundance of N. pachyderma (Fig. 3c: Supplementary Fig. 7g) suggest weakened upwelling at Site 1087 C, indicating growing separation from the primary upwelling cell11,69. The northward migration of upwelling cells and fluctuations in the position of Southern Ocean fronts might have modulated the winter rainfall in the southernmost South Africa, shaping unique flora and fauna compared to drier northern and northeastern regions70.

Conclusions

Our findings support that the evolution of the BUS since the Late Miocene was closely linked to large-scale ocean-atmosphere reorganisation and Southern Hemisphere cryospheric changes. Between ~11.7 and 10 Ma, before the development of the BUS, the Southeast Atlantic experienced warmer conditions, an expanded South Atlantic gyre, and a dramatically northward-extended Agulhas Leakage. We infer that stronger SE trade winds and a northward shift of Southern Ocean fronts, associated with Antarctic ice sheet expansion, triggered the onset of the BUS at ~10 Ma. This mechanism strengthened during the LMC, contributing to the intensification of the BUS and enhanced regional productivity between ~8 and 4.8 Ma. Unlike other regions where the role of atmospheric pCO2 in driving Late Miocene aridification remains debatable, our findings point to a stronger link between BUS intensification and southern African aridification. Between ~4.8 and 3.7 Ma, cooling and upwelling were halted and perhaps reversed. We speculate that the southward shift of Southern Ocean fronts during the early Pliocene warming led to enhanced Agulhas Leakage and a prominent Benguela Niño-like conditions. Aridification, however, continued suggesting a temporary decoupling between upwelling strength and regional climate. Between ~3.7 and 3 Ma, the Antarctic ice expansion strengthened atmospheric circulation and re-intensified the BUS, effectively terminating Benguela Niño-like conditions. This reduced the influence of Indian Ocean inflow and contributed to regional aridification. The upwelling persisted until ~2 Ma before declining as the main upwelling cells shifted northward. This study presents the continuous reconstruction of the BUS since the Late Miocene and demonstrates its dominant role in driving southern African aridification, resolving key gaps about the timing and mechanisms linking BUS evolution, global climate changes, and vegetation shifts.

Methods

Age model

The age model between 1.5 Ma and the Holocene is based on foraminiferal oxygen isotope stratigraphy71. The age model between 5.96 and 1.5 Ma, is based on nannofossil datums72, updated to new timescale73. The Late Miocene age model for ODP Site 1087, as used in previous studies4,74, is based on astronomically calibrated age model75. This model was developed by tuning a high resolution composite XRF-Fe intensity record of ODP 1085 and ODP 1087, using shipboard nannofossil datums72. However, a recent study76 introduced a revised age model for ODP 1085 which show large discrepancies with the shipboard age model and highlighting the need for caution when relying on the shipboard stratigraphy. In this study, we have constructed the age model for Late Miocene section (~11.7–6.6 Ma) of ODP 1087 by employing the tie-points between Sites ODP 1085 and ODP 1087, as identified in previous study75 (Supplementary Table 2). Based on the revised age model for ODP 108576, we determined the ages corresponding to the tie-point depths at ODP 1085 (Supplementary Table 2). These, in turn, provide the age constraints for the corresponding depths at ODP 1087 (Supplementary Table 2). Linear sedimentation rates were assumed between all age control points, and the depth–age relationship is presented in Supplementary Fig. 13.

Stable isotope analysis

For the stable oxygen and carbon isotope analyses, we used shallow-dwelling planktic foraminifer Globigerina bulloides (250–350 μm, about 10–15 individuals) between ~11.3 Ma and 6.1 Ma. Additionally, we analysed deep-dwelling planktic foraminiferal species Globoconella miotumida (about 10–15 individuals from 250−350 μm) between ~11.7 and 6.1 Ma. Published isotope data (δ18O and δ13C) from Site 1087 C were used for the interval younger than 6.1 Ma11. Stable isotopes were analysed using a Thermo MAT 253 Plus dual inlet isotope ratio mass spectrometer attached to Kiel IV Carbonate device at Brown University, U.S.A. Replicate analysis of in-house standards Brown Yule Marble (BYM) and Carrara Marble (CM) was carried out throughout these analyses to evaluate precision. The average value for BYM and CM standards of carbon isotopes are −2.25 ± 0.02 ‰ and 2.05 ± 0.02 ‰ (1σ; n = 15, n = 27), respectively and for oxygen isotopes −6.50 ± 0.08‰ and −1.89 ± 0.05 ‰ (1σ; n = 15, n = 27), respectively. Removal of one outlier BYM oxygen standard yields −6.52 ± 0.06 (1σ; n = 14). The results are reported relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB). Long-term calibration of these two in-house marble standards relative to NBS-19 has been conducted in the course of calibrating fourteen 5 L cylinders of reference CO2 gas produced in the laboratory between 2001 and 2020. These calibrations yield values of −2.26‰ and −6.50‰ for BYM carbon and oxygen and 2.05‰ and −1.89‰ for Carrara carbon and oxygen, respectively (1σ, n = 223 for BYM and n = 257 for Carrara).

Counting of planktic foraminifera

Ocean sediment samples were obtained from ODP Site 1087 (31°27.9137′S, 15°18.6541′E; 1374 m water depth) on the continental slope off southwestern Africa. Samples were provided by the International Ocean Drilling Programme (IODP) repository. Census counts of planktic foraminifera were made from 500 sediment core samples from ODP Site 1087 C, at an average temporal resolution of ~23,000 years per sample. A total of 68 planktic foraminiferal species were identified following the established taxonomic criteria77,78,79. Planktic foraminiferal abundance analyses followed the methodology from Gupta and Thomas80, involving the counting of ~300 specimens from the size fraction >149 μm for each sample. The ecological preferences of planktic foraminiferal species were determined based on earlier studies77,81,82. According to these habitat preferences, the species were grouped into cooler-water and warmer-water species (Supplementary Note 3; Supplementary Table 1). The cooler- and warmer water species grouping is specific to the Benguela upwelling region, where the cooler-water species are associated with cooler, productive waters of Benguela upwelling region, while the warmer-water species thrive in warmer, less-productive waters away from the main upwelling cells. Key members of the cooler-water species include N. pachyderma, N. incompta, N. acostaensis, G. bulloides and Globoturborotalita woodi. Major representatives of the warmer-water species consist of G. menardii, Globigerinoides ruber, T. sacculifer, G. inflata, G. puncticulata, G. miotumida, G. falconensis, and G. crassaformis. Further details are provided in Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 8–10. Additional minor contributors to both cooler- and warmer-water species groups are listed in the Supplementary Table 1 (also see Supplementary Note 3). For the interval younger than 6.1 Ma, we used published data on the relative abundance of planktic foraminifera from Site 1087C11.

Completion of palaeo-CO2 data

In Fig. 3d. paleo-CO2 data derived from alkenone and boron isotope methods is represented from ~11.7 Ma to the Holocene. We use latest available datasets for each method, obtained from https://paleo-co2.org. Alkenone-based palaeo-CO2 estimates are depicted as blue triangles25,83,84,85,86,87,88,89 while for the boron isotope-based estimates are represented by orange diamonds90,91,92,93,94,95.

Statistical analysis

We employed a combination of statistical approaches to evaluate the temporal trends and differences in our proxy records. Welch’s t-tests were conducted in Microsoft excel to compare mean values between key intervals, given their robustness against unequal variances and sample sizes (see Supplementary Note 1). Long-term trends were assessed using piecewise linear regression, performed using the Statsmodels package in Python 3.13, and Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) implemented in Acycle96 (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5). Together, these statistical approaches increased the robustness of our interpretations by providing consistent insights across multiple methods.

Data availability

All the data generated from ODP Site 1087 C and presented in this paper are available via the Zenodo database (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15393113).

References

Zachos, J. et al. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–693 (2001).

Herbert, T. D. et al. Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems. Nat. Geosci. 9, 843–847 (2016).

Siesser, W. G. Late Miocene origin of the Benguela upwelling system of northern Namibia. Science 208, 283–285 (1980).

Diester-Haass, L., Meyers, P. A. & Bickert, T. Carbonate crash and biogenic bloom in the late Miocene: evidence from ODP Sites 1085, 1086, and 1087 in the Cape Basin, southeast Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 19, PA1007 (2004).

Rommerskirchen, F., Condon, T., Mollenhauer, G., Dupont, L. M. & Schefuss, E. Miocene to Pliocene development of surface and subsurface temperatures in the Benguela current system. Paleoceanography 26, PA3216 (2011).

Bard, E. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Migration of the subtropical front as a modulator of glacial climate. Nature 460, 380–383 (2009).

Etourneau, J., Martinez, P., Blanz, T. & Schneider, R. Pliocene-Pleistocene variability of upwelling activity, productivity, and nutrient cycling in the Benguela region. Geology 37, 871–874 (2009).

Etourneau, J., Schneider, R., Blanz, T. & Martinez, P. Intensification of the Walker and Hadley atmospheric circulations during the Pliocene-Pleistocene climate transition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 297, 103–110 (2010).

McKay, R. et al. Antarctic and Southern Ocean influences on late Pliocene global cooling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6423–6428 (2012).

Ufkes, E. L. S. & Kroon, D. Sensitivity of south-east Atlantic planktonic foraminifera to mid-Pleistocene climate change. Palaeontology 55, 183–204 (2012).

Mohanty, R. N., Clemens, S. C. & Gupta, A. K. Dynamic shifts in the southern Benguela upwelling system since the latest Miocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 637, 118729 (2024).

Tyson, P. D. & Preston-Whyte, R. A. The Weather and Climate of Southern Africa, Vol. 396 (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Shannon, L. & Nelson, G. The Benguela: large scale features and processes and system variability. In The South Atlantic, 163–210 (Springer, 1996).

Carr, M. E. Estimation of potential productivity in eastern boundary currents using remote sensing. Deep Sea Res. II 49, 9–80 (2002).

Gordon, A. L. Interocean exchange of thermocline water. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 5037–5046 (1986).

Peeters, F. J. C. et al. Vigorous exchange between the Indian and Atlantic oceans at the end of the past five glacial periods. Nature 430, 661–665 (2004).

Caley, T., Giraudeau, J., Malaizé, B., Rossignol, L. & Pierre, C. Agulhas Leakage as a key process in the modes of Quaternary climate changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6835–6839 (2012).

Patel, N. The Role of Agulhas Leakage in Pliocene Climate Change. http://scholarworks.umass.edu (2019).

Holbourn, A. E. et al. Late Miocene climate cooling and intensification of southeast Asian winter monsoon. Nat. Commun. 9, 1584 (2018).

Huang, Y., Clemens, S. C., Liu, W., Wang, Y. & Prell, W. L. Large-scale hydrological change drove the late Miocene C4 plant expansion in the Himalayan foreland and Arabian Peninsula. Geology 35, 531–534 (2007).

Dupont, L. M., Rommerskirchen, F., Mollenhauer, G. & Schefuß, E. Miocene to Pliocene changes in South African hydrology and vegetation in relation to the expansion of C4 plants. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 375, 408–417 (2013).

Polissar, P. J., Rose, C., Uno, K. T., Phelps, S. R. & deMenocal, P. Synchronous rise of African C4 ecosystems 10 million years ago in the absence of aridifcation. Nat. Geosci. 12, 657–660 (2019).

Wen, Y. et al. CO2-forced Late Miocene cooling and ecosystem reorganizations in East Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2214655120 (2023).

Cerling, T. E. et al. Global vegetation change through the Miocene/Pliocene boundary. Nature 389, 153–158 (1997).

Tipple, B. & Pagani, M. The early origins of terrestrial C4 photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 35, 435–461 (2007).

Tanner, T. et al. Decreasing atmospheric CO2 during the late Miocene cooling. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 35, e2020PA003925 (2020).

Schefuß, E. & Dupont, L. M. Multiple drivers of Miocene C4 ecosystem expansions. Nat. Geosci. 13, 463–464 (2020).

Seki, O. et al. Alkenone and boron-based Pliocene pCO2 records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 201–211 (2010).

Cook, C. P. et al. Dynamic behaviour of the East Antarctic ice sheet during Pliocene warmth. Nat. Geosci. 6, 765–769 (2013).

Nirmal, B. & Mohan, K. The late Neogene to Quaternary surface water changes as responses from planktonic foraminifera at the transitional subantarctic zone. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 603, 111183 (2022).

Shannon, L. V., Boyd, A. J., Brundrit, G. B. & Taunton-Clark, J. On the existence of an El Niño-type phenomenon in the Benguela System. J. Mar. Res. 44, 495–520 (1986).

Rosell-Melé, A., Martínez-Garcia, A. & McClymont, E. L. Persistent warmth across the Benguela upwelling system during the Pliocene epoch. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 386, 10–20 (2014).

Rubbelke, C. B. et al. Plio-Pleistocene Southwest African hydroclimate modulated by Benguela and Indian Ocean temperatures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103003 (2023).

Duque-Caro, H. Neogene stratigraphy, paleoceanography and paleobiology in northwest South America and the evolution of the Panama Seaway. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 77, 203–234 (1990).

Siesser, W. G. Aridification of the Namib Desert: evidence from oceanic cores. In Antarctic Glacial History and World Palaeoenvironments (eds. van Zinderen Bakker, E. M.) 105–113 (CRC Press, 1978).

Shannon, L. V. The Benguela ecosystem I: evolution of the Benguela, physical features and processes. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 23, 105–182 (1985).

Marlow, J. R., Lange, C. B., Wefer, G. & Rosell-Melé, A. Upwelling intensification as part of the Pliocene-Pleistocene climate transition. Science 290, 2288–2294 (2000).

Tomczak, M. & Godfrey, J. S. Regional Oceanography: an Introduction (Pergamon, 1994).

Belem, A. L. et al. Salinity and stable oxygen isotope relationship in the Southwestern Atlantic: constraints to paleoclimate reconstructions. Acad. Bras Ciências 91, e20180226 (2019).

Wu, X., Hu, Y., Nan, J. & Yao, W. A marine barite perspective of the late Miocene biogenic bloom in the equatorial Indian Ocean and equatorial western Atlantic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111748 (2024).

Hodell, D. A., & Venz-Curtis, K. A. Late Neogene history of deepwater ventilation in the Southern Ocean. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GC001211 (2006).

Farrell, J. W. et al. Late Neogene sedimentation patterns in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. in Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results 138 (eds Pisias, N. G., Mayer, L. A., Janecek, T. R., PalmerJulson, A. & van Andel, T. H.) 717–756 (Ocean Drilling Program, 1995).

Gupta, A. K., Singh, R. K., Joseph, S. & Thomas, E. Indian Ocean high-productivity event (10–8 Ma): linked to global cooling or to the initiation of the Indian monsoons?. Geology 32, 753–756 (2004).

Bickert, T., Haug, G. H. & Tiedemann, R. Late Neogene benthic stable isotope record of Ocean Drilling program Site 999: implications for Caribbean paleoceanography, organic carbon burial, and the Messinian salinity crisis. Paleoceanography 19, PA1023 (2004).

Filippelli, G. M. Intensification of the Asian monsoon and a chemical weathering event in the late Miocene–early Pliocene: Implications for late Neogene climate change. Geology 25, 27–30 (1997).

Pillot, Q., Such´eras-Marx, B., Sarr, A. C., Bolton, C. T. & Donnadieu, Y. A global reassessment of the spatial and temporal expression of the late Miocene biogenic bloom. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 38, e2022PA004564 (2023).

DeConto, R. M. et al. Thresholds for Cenozoic bipolar glaciation. Nature 455, 652–656 (2008).

Zhong, Y. et al. Enhanced phosphorus weathering contributed to late Miocene cooling. Nat. Commun. 16, 1124 (2025).

Martin, H. A. Cenozoic climatic change and the development of the arid vegetation in Australia. J. Arid Environ. 66, 533–563 (2006).

Pagani, M., Freeman, K. H. & Arthur, M. A. Late Miocene atmospheric CO2 concentrations and the expansion of C4 grasses. Science 285, 876–879 (1999).

Hoetzel, S., Dupont, L., Schefuß, E., Rommerskirchen, F. & Wefer, G. The role of fire in Miocene to Pliocene C4 grassland and ecosystem evolution. Nat. Geosci. 6, 1027–1030 (2013).

Billups, K. Late Miocene through early Pliocene deep water circulation and climate change viewed from the sub-Antarctic South Atlantic. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 185, 287–307 (2002).

Diester-Haass, L., Billiups, K. & Emeis, K. C. Late Miocene carbon isotope records and marine biological productivity: Was there a (dusty) link?. Paleoceanography 21, 1–18 (2006).

Koseki, S. & Demissie, T. Does the Drakensberg dehydrate southwestern Africa?. J. Arid Environ. 158, 35–42 (2018).

Sepulchre, P. et al. Tectonic uplift and eastern Africa aridification. Science 313, 1419–1423 (2006).

Dekens, P. S., Ravelo, A. C. & McCarthy, M. D. Warm upwelling regions in the Pliocene warm period. Paleoceanography 22, PA3211 22 (2007).

Brierley, C. M. et al. Greatly expanded tropical warm pool and weakened Hadley circulation in the early Pliocene. Science 323, 1714–1718 (2009).

Philander, S. G., & Fedorov, A. V. Role of tropics in changing the response to Milankovich forcing some three million years ago. Paleoceanography. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002PA000837 (2003).

Wara, M. W., Ravelo, A. C. & Delaney, M. L. Permanent El niño-like conditions during the pliocene warm period. Science 309, 758–761 (2005).

Fedorov, A. V. et al. Patterns and mechanisms of early Pliocene warmth. Nature 496, 43–49 (2013).

Mohrholz, V. et al. Cross shelf hydrographic and hydrochemical conditions and their short term variability at the northern Benguela during a normal upwelling season. J. Mar. Syst. 140, 92–110 (2014).

Taylor, A. K. et al. Plio-Pleistocene continental hydroclimate and Indian ocean sea surface temperatures at the southeast African margin. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004186 (2021).

Karas, C. et al. Pliocene oceanic seaways and global climate. Sci. Rep. 7, 39842 (2017).

Sniderman, J. M. K. et al. Pliocene reversal of late Neogene aridification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1999–2004 (2016).

Abell, J. T., Winckler, G., Anderson, R. F. & Herbert, T. D. Poleward and weakened westerlies during Pliocene warmth. Nature 589, 70–74 (2021).

Cane, M. A. & Molnar, P. Closing of the Indonesian seaway as a precursor to east African aridification around 3–4 million years ago. Nature 411, 157–162 (2001).

Maslin, M. A., Pancost, R. D., Wilson, K. E., Lewis, J. & Trauth, M. H. Three and half million year history of moisture availability of South West Africa: evidence from ODP site 1085 biomarker records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 317, 41–47 (2012).

Dupont, L. M., Donner, B., Vidal, L., Pérez, E. M. & Wefer, G. Linking desert evolution and coastal upwelling: Pliocene climate change in Namibia. Geology 33, 461–464 (2005).

Petrick, B. et al. Oceanographic and climatic evolution of the southeastern subtropical Atlantic over the last 3.5 Ma. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 492, 12–21 (2018).

Rubbelke, C. B. et al. Southern Hemisphere subtropical front impacts on Southern African hydroclimate across the mid-pleistocene transition. Nat. Commun. 16, 3501 (2025).

McClymont, E. L., Rosell-Melé, A., Giraudeau, J., Pierre, C. & Lloyd, J. M. Alkenone and coccolith records of the mid-pleistocene in the south-east Atlantic: implications for the UK′37 index and South African climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1559–1572 (2005).

Shipboard Scientific Party. Introduction: background, scientific objectives, and principal results for Leg 175 (Benguela Current and Angola-Benguela upwelling systems). in Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program Initial Reports (eds Wefer Berger, W.H., Richter, C. et al.) 457–484 (Ocean Drilling Program, 1998).

Raffi, I. et al. The Neogene period. in Geologic Time Scale 2020 (eds. Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, G. J. & Ogg, G. M.) 1141–1215 (Elsevier, 2020).

Udeze, C. U. & Oboh-Ikuenobe, F. E. Neogene palaeoceanographic and palaeoclimatic events inferred from palynological data: Cape Basin off South Africa, ODP Leg 175. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 219, 199–223 (2005).

Westerhold, T., Bickert, T. & Röhl, U. Middle to late Miocene oxygen isotope stratigraphy of ODP site 1085 (SE Atlantic): new constrains on Miocene climate variability and sea-level fluctuations. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 217, 205–222 (2005).

Gastaldello, M. E., Agnini, C., Westerhold, T., Drury, A. J. & Alegret, L. A benthic foraminifera perspective of the late miocene-early pliocene biogenic bloom at ODP Site 1085 (Southeast Atlantic Ocean). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 638, 112040 (2024).

Kennett, J. P. & Srinivasan, M. S. Neogene Planktonic Foraminifera, Vol. 265 (Hutchinson and Ross, 1983).

Hemleben, C., Spindler, M. & Anderson, O. R. Modern Planktonic Foraminifera 1st edn, Vol. 363 (Springer, 1989).

Lam, A. R. & Leckie, R. M. Late neogene and quaternary diversity and taxonomy of subtropical to temperate planktic foraminifera across the kuroshio current extension, northwest Pacific Ocean. Micropaleontology 66, 177–268 (2020).

Gupta, A. K. & Thomas, E. Initiation of Northern Hemisphere glaciation and strengthening of the northeast Indian monsoon: Ocean drilling program site 758, eastern equatorial Indian Ocean. Geology 31, 47–50 (2003).

Bé, A. W. H. & Tolderlund, D. S. In Micropaleontology of Oceans (eds Funnell, B. M. & Riedel, W. R.) 105–149 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1971).

Giraudeau, J., Monteiro, P. M. & Nikodemus, K. Distribution and malformation of living coccolithophores in the northern Benguela upwelling system off Namibia. Mar. Micropaleontol. 22, 93–110 (1993).

Jasper, J. P. & Hayes, J. M. A carbon isotope record of CO2 levels during the late quaternary. Nature 347, 462–464 (1990).

Andersen, N., Müller, P. J., Kirst, G. & Schneider, R. Alkenone δ¹³C as a proxy for past pCO₂ in surface waters: results from the late quaternary Angola current. Proxies Paleoceanogr. 469, 488 (1999).

Bolton, C. T. et al. Decrease in coccolithophore calcification and CO2 since the middle Miocene. Nat. Commun. 7, 10284 (2016).

Badger, M. P. et al. Insensitivity of alkenone carbon isotopes to atmospheric CO2 at low to moderate CO2 levels. Clim. Past 15, 539–554 (2019).

Zhang, Y. G. et al. Refining the alkenone-pCO2 method I: lessons from the quaternary glacial cycles. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 260, 177–191 (2019).

González-Lanchas, A. et al. Carbon isotopic fractionation of alkenones and gephyrocapsa coccoliths over the late quaternary (marine isotope stages 12–9) glacial-interglacial cycles at the western tropical Atlantic. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol 36, e2020PA004175 (2021).

Rae, J. W. B. et al. Atmospheric CO2 over the past 66 million years from marine archives. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 49, 609–641 (2021).

Henehan, M. J. et al. Calibration of the boron isotope proxy in the planktonic foraminifera Globigerinoides ruber for use in palaeoCO2 reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 364, 111–122 (2013).

Martínez-Botí, M. et al. Plio-Pleistocene climate sensitivity evaluated using high-resolution CO2 records. Nature 518, 49 (2015).

Dyez, K. A., Hönisch, B. & Schmidt, G. A. Early Pleistocene obliquity-scale pCO2 variability at ~ 1.5 million years ago. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 1270–1291 (2018).

Sosdian, S. M. et al. Constraining the evolution of Neogene ocean carbonate chemistry using the boron isotope pH proxy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 248, 362–376 (2018).

Vega, E. D. L., Chalk, T. B., Wilson, P. A., Bysani, R. P. & Foster, G. L. Atmospheric CO2 during the mid-Piacenzian warm period and the M2 glaciation. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–8 (2020).

Brown, R. M., Chalk, T. B., Crocker, A. J., Wilson, P. A. & Foster, G. L. Late Miocene cooling coupled to carbon dioxide with Pleistocenelike climate sensitivity. Nat. Geosci. 15, 664–670 (2022).

Li, M., Hinnov, L. & Kump, L. Acycle: Time-series analysis software for paleoclimate research and education. Comput. Geosci. 127, 12–22 (2019a).

Peterson, R. G. & Stramma, L. Upper-level circulation in the South Atlantic Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 26, 1–73 (1991).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the Ocean Drilling Program for providing samples for the present study (IODP request no. 073425IODP). This study was supported by Sir J.C. Bose Fellowship of Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), now Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF), Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (Grant no. JBR/2021/000019). RNM expresses his gratitude to Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, for providing fellowship (SPM-06/081(0314)/2019-EMR-I). Authors thank the editors and three reviewers who offered critical comments that greatly improved the quality of the manuscript. Thanks are also to P. Gupta (IIT Kharagpur) for assistance in statistical analyses. RNM thanks A.D. Singh, Banaras Hindu University, for help in the identification of planktic foraminifera.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rudra Narayan Mohanty: Writing—original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Anil K. Gupta: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing—original draft. Steven C. Clemens: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Robyn Granger, Dinesh K. Naik and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jennifer Veitch and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

43247_2025_2948_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information: Benguela upwelling system triggered and intensified southern African aridification in the Late Miocene

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohanty, R.N., Gupta, A.K. & Clemens, S. Benguela upwelling system triggered and intensified southern African aridification in the Late Miocene. Commun Earth Environ 6, 989 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02948-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02948-0