Abstract

Weak layers have been identified as lithological contrasts on continental slopes to precondition giant submarine landslides. Although sea-level variations are well known to generate weak layers on glaciated continental margins at high latitudes, their role on non-glaciated continental slopes, mostly at low latitudes, remains poorly constrained. Here, we combine seismic and well-log data, showing that the glide plane beneath the giant Baiyun Slide Complex in the South China Sea is located at a lithological interface, within a relatively coarse-grained unit that was deposited during the late Pliocene sea-level drop. Fluid migration pathways are further identified in the underlying fine-grained unit, which was deposited during the early Pliocene sea-level rise. Sea-level variations are therefore proposed to form unstable sedimentary sequences by the deposition of interbedded fine- and coarse-grained sediments. Considering the global records of sea-level variations and consequent lithological contrasts on non-glaciated slopes, our results shed light on the development of slope instability in low-latitude oceans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Submarine landslides are ubiquitous features on continental slopes worldwide, raising major concerns regarding their underlying controls and geohazards potential1. The spatial correlation between submarine landslides and layer-parallel glide planes suggests that specific stratigraphic layers can strongly influence slope stability2,3. These layers are further related to lower strength to focus the development of the glide plane during landslides and are defined as the ‘weak layers’2. On glaciated continental margins, mainly in middle- to high-latitude oceans, changes of sediment types during glacial-interglacial cycles can result in distinct lithological contrasts and ‘inherited’ weak layers, of which the shear strength is inherently lower than adjacent units4,5,6,7. In parallel, the strength of layers can be reduced by external processes, such as overpressure from rapid sedimentation as glacial sediments arrive in large quantities by ice streams8 or gas hydrate dissociation by warming bottom waters9, leading to the formation of ‘induced’ weak layers10.

Although specific biological productivity and tectonics, such as diatom oozes and constricted ocean gateways, are known to result in distinct lithological contrasts10,11, the influence of climate changes on weak layer formation on non-glaciated margins, mostly located in low-latitude oceans, remains poorly documented. Although the external factors for ‘induced’ weak layers might still exist, the lack of glacigenic sediments input on non-glaciated margins results in the relatively subtle or absent lithological contrasts12. The presence of numerous giant submarine landslides, coupled with millions of people living in proximity, highlights the critical need to improve our understanding of the formation mechanisms of weak layers in low-latitude oceans13,14,15.

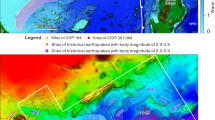

The non-glaciated South China Sea (SCS), located at low latitudes (approximately 15° N and 114° E), is one of the largest marginal seas in the western Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1a). On its northern continental slope, the boundaries between Mesozoic crustal segments have provided a strike-slip faults domain during diachronous rifting and opening of the SCS, further acting as conduits of magma and thermogenic gas to present16,17,18. Since the cessation of SCS spreading in the early Miocene, a combination of tectonic events, sediment supply, and global sea-level fluctuations has controlled the migration of the shelf break and coastal onlaps in the northern SCS (Fig. 1b)19,20,21,22,23. The deposition of coarse-grained turbidites (P1-P7 in Fig. 1a) and fine-grained contourites (Site 18, 29, 69, 138 and 145 in Fig. 1a) records the influence of turbidity and contour currents. Coarser-grained deposits reflect periods of sea-level drop and lowstand, whereas finer-grained sediments were deposited during sea-level rise and highstand24,25.

a Location of study area in the South China Sea. Black polygons and lines represent the coverage of seismic data and profiles used in this research, respectively. The locations of the shelf break are adapted from Zhuo et al. (2019). Grain-size distribution on the modern seafloor is based on data from Zhong et al. (2017) (marked by blue dots) and Wang et al. (2018, 2020) (marked by red dots). Multibeam data are from CNOOC. b Seismic-well integration at BY7-1-1, with correlation to coastal onlap and global sea-level changes21,31. Porosity, permeability, and grain size were estimated from well-log data by CNOOC. Biostratigraphic correlation was processed by CNOOC20. SWC Surface Water Currents, IWC Intermediate Water Currents, DWC-Deep Water Currents, SCS South China Sea, TW Taiwan, HI Hainan Island, VN-Vietnam, PH Philippines, LCGU Lower coarse-grained unit, UCGU Upper coarse-grained unit, FGU Fine-grained unit, CGL Coarse-grained layer, FGL Fine-grained layer.

A wide variety of slope instabilities has been identified on the northern South China Sea margin, such as the giant creep zone, exceeding 800 km2 with high hazard potential26, and the Baiyun Slide Complex, affecting an area of ~10,000 km² and displacing ~1000 km³ of sediments27,28,29. Although layer-parallel glide planes suggest the involvement of weak layers below the Baiyun Slide Complex29,30, their physical properties and depositional processes remain inadequately understood. To elucidate the development of these weak layers, we analyzed geophysical and chronological data from an industry well on the intact upper slope (Fig. 1a). By tracing the seismic reflection to the logged sequence, we can identify the distinct geophysical properties of the weak layer and the depositional systems that contain them. Combined with the correlation between sea-level changes and the depositional systems, we aim to develop a widely applicable model for the formation mechanism of weak layer, enhancing our understanding of the influence of sea-level variations, which reflect climatic changes, on slope instability in non-glaciated low-latitude oceans.

Results

Sedimentology and physical properties of sediments on the unfailed slope

The headwall region of the Baiyun Slide Complex was evacuated at ~0.54 Ma (Fig. 2a,f). The bedding-parallel glide plane, H1, is identified as the top of the uppermost seismic reflections that are continuous across headwall, at the bottom of MTDs with chaotic seismic facies (Fig. 2f). The headwall of Baiyun Slide is identified at the boundary between the intact upper slope and disrupted lower slope with continuous and chaotic seismic facies, respectively (Fig. 2f). Blocky structures within the MTDs manifest as triangle shapes on the seismic profile and can still be recognized on the modern seafloor as local positive relief (marked in Fig. 2f). Exploration well BY7-1-1 is located at the intact upper slope 40 km away from the headwall of giant Baiyun Slide Complex, covered by both 2D and 3D seismic surveys (Figs. 1a and 2a). Core-log-seismic integration shows few distinct units, including a lower coarse-grained unit (LCGU) between H4 and H3, a fine-grained unit (FGU) between H3 and H2, and an upper coarse-grained unit (UCGU) above H2.

The LCGU was deposited during 6.3 to 5.0 Ma with interbedded fine- and relatively coarse-grained layers and variable porosity and permeability (Fig. 1b). Global sea-level was relatively stable at the same time, whereas coastal onlaps have shifted landward and oceanward on a scale of ~50 km (Fig. 1b).

Since 5.0 Ma, global sea-level has been rising, reaching a peak of ~20 m higher than the present sea level by 3.8 Ma (Fig. 1b). Coastal onlap records a landward shift of more than 100 km starting at 5.0 Ma, followed by a relatively constant position afterwards (Fig. 1b)31. The FGU was deposited in this period with constant porosity and low permeability.

From 3.8 Ma to 2.4 Ma, a drop in global sea level was accompanied by multiple shifts in coastal onlap in the northern SCS (Fig. 1b). The UCGU was deposited during this period, consisting of interbedded fine- and coarse-grained layers, such as a permeable coarse-grained layer (CGL in Fig. 1b) and the overlying low-permeability fine-grained layer (FGL in Fig. 1b).

Records of turbidity and contour currents

Cut-and-fill structures, including large-scale canyons and relatively small-scale gullies, are recorded in seismic data, illustrating the development and activity of turbidity currents since the Late Miocene (Fig. 2). The bottom of LCGU (H4) separates extensive canyons below and subparallel seismic reflections above, where isolated canyons were developed, indicating the existence of turbidity currents since 6.3 Ma (Fig. 2a). Below the top of LCGU (H3), a group of slightly curved linear features oriented toward lower slope (Fig. 3a) corresponds to small-scale gullies reflecting the turbidity current activity before 5.0 Ma. Cut-and-fill structures were not observed within the FGU but reappeared in the UCGU as gullies and canyons above H2 (Fig. 2c), revealing the suspension of turbidity current activity from 5.0 to 3.8 Ma and a rejuvenation of canyons and gullies afterwards.

Seismic profiles and seafloor relief reveal the moats of contour currents on the modern seafloor (Figs. 1a and 2). In the study area, moats are recognized as erosional depressions within both the LCGU and UCGU (Fig. 2c). Mounded and wavy drifts are observed adjacent to the moats (Fig. 2d,e). These drifts exhibit asymmetric concave structures with internal reflections that are truncated by the moats on their upper slope (see the truncated dotted black lines within the wavy drifts in Fig. 2d,e).

Indicators of focused fluid flow

Seismic data show High-Amplitude Anomalies (HAAs) with polarity reversal indicating the presence of fluid and, in particular, free gas32,33. In our study area, HAAs are widely distributed across multiple stratigraphic levels (Fig. 2b). Strike-slip faults with flower structures and en-echelon patterns, acting as the conduits of magma and thermogenic gas in the northern SCS18, lie adjacent to these HAAs, forming gas migration features such as ‘gas flag’ structures (Fig. 2b). In parallel, pipes, as conduits for focused fluid flow, are identified within the FGU, characterized by sub-circular discontinuities on the structure maps and vertical structures with absence of reflections on the seismic profiles (Figs. 2d,f, 3b,c).

The roots of these pipes, where they terminate downwards, are observed just below the FGU at a depth deeper than ~1500 ms (Fig. 3b,e). The heights of these pipes are a few tens of meters, with a vertically consistent diameter of a few hundred of meters (Fig. 2g,h). Most of the pipes become absent at the top of FGU, where their tops are preserved as sub-circular structures and overlying wavy seismic reflections (Figs. 2d and 3c). These pipes thus record the accumulation of fluids below the FGU and their upward migration through this unit.

Discussion and Conclusion

Mixed contourite-turbidite system formed during sea-level changes

Due to the slow post-rift subsidence since the Late Miocene, relative sea level in the northern SCS follows the global eustatic variations by astronomical forcing, producing repeated shifts of coastal onlaps on continental slopes21,34,35. Migration of the paleo-shelf break indicates that our study area has resided on the continental slope at the same time (Fig. 1a)22,23. The modern water circulation patterns in SCS were established at the same time, with the closure of Indonesian Gateway and the narrowing and shallowing of Luzon Strait36,37,38. Due to the oceanward progradation of the shelf break since the Late Miocene, turbidity gullies from the shelf break have developed on the modern seafloor of the study area at present (Figs. 1a and 3d)23,39. Evidence of turbidity and contour currents, as well as the heterogeneous lithologies within the logged sequence, further indicate that the depositional system in our study area was dominated by distinct processes at different stages.

On the northern continental slope of the SCS, turbidity currents are more active during periods of sea-level lowstands or drops, when the distance between the shoreline and shelf edge decreases24,40,41,42. In the study area, the evidence of turbidity currents, such as the gullies before 5.0 Ma and the canyons after 3.8 Ma, demonstrates the increase of turbidity current activity during sea-level lowstands and drops (Figs. 2c and 3a). Although the turbidity gullies from shelf break are observed on the modern seafloor of study area (Figs. 1a and 3d), the northward location of shelf break before present, as well as the initiation of these turbidity currents since LGM23,39, suggest these gullies should be inactive during the deposition of logged sequence (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, the coarse-grained (sandy and silty) turbidites (Sites P1-P7 in Fig. 1a) from these gullies can indicate the CGLs in FCGU and UCGU as the records of turbidity currents on the paleo-seafloor (Fig. 1b). In parallel, fine-grained (silty and clayey) sediments are acquired around the study area and identified as the deposition of contourite drifts on the modern seafloor (Sites 18, 69 and 138 in in Fig. 1a)43. Considering the establishment of modern water circulation patterns since the Late Miocene and the development of moats and drifts in the study area at the same time (Fig. 2d,e), the FGLs in LCGU and UCGU are the deposition of contour currents.

Although both the features of turbidity and contour currents were absent in the study area between 5.0 and 3.8 Ma, the continuously generated contourite drifts in the northern and southern SCS reveal a long-term existence of contour currents since the late Miocene36. Contour currents with low velocity or weak activity can form fine-grained contourites without prominent erosional features, such as plastered drifts that dip oceanward and gradually thicken downslope, characterized by continuous, sub-parallel internal reflections44. The oceanward-dipping FGU with continuous, subparallel reflections and gradually downslope thickening structures (Fig. 2e,f) is therefore interpreted as a relatively contourite-dominated interval formed under weak contour current activity and absence of turbidity currents. The interbedded fine- and coarse-grained LCGU and UCGU, on the other hand, represent a relatively turbidite-dominated mixed depositional system with active turbidity and contour currents.

Formation mechanism of the weak layer

Features indicative of focused fluid flow are identified within the FGU. The pipes terminate at the top of FGU or just below. The constant diameter of the pipes suggests that there is no lateral fluid escape45,46,47. The roots of the pipes are located at the top of the LCGU. Based on these observations and permeability contrasts, we infer that the LCGU was sufficiently overpressured for pipes to form in the overlying FGU. The positive correlation between the density of pipe occurrence below 1500 ms TWT and the thickness of FGU on the lower slope shows that the continuous deposition of low-permeability sediment between 5.0 and 3.8 Ma, when a contourite-dominated depositional system developed, likely was a key contributor to generating overpressure in the LCGU, driving focused fluid flow (Figs. 3f and 4b). The pipes enabled the fluids to bypass the FGU and migrate into the upper coarse-grained layer, in which fluids migrated laterally and upwards in the pore space. The overlying low-permeability contourites (FGL) acted as a seal to further upward migration, preventing dissipation of excess fluids and leading to excess pore pressure buildup within this CGL (in particular in its upper part near the interface to the sealing FGL). Overpressure at the interface (H1 in this study) ultimately promoted the development of the glide plane during submarine landslides (Fig. 4c,d).

a Sea-level lowstand: turbidite-dominated lower coarse-grained unit (LCGU) with interbedded turbidites (CGL) and contourites (FGL); b Sea-level rise: contourite-dominated fine-grained unit (FGU) forming thick drifts without input of turbidites. Focused fluid flow and pipes develop within this low-permeability unit; c Sea-level drop: upper coarse-grained unit (UCGU) with a permeable CGL overlain by an FGL as a seal, accommodating fluid overpressure in long term. d During submarine landslides, the permeability contrast at the CGL–FGL interface localizes the glide plane. Perm. – permeability.

Due to the limits in vertical seismic resolution, we cannot pinpoint the exact location of the glide plan,e and we cannot exclude that an external trigger was necessary. Failure could have taken place (i) along the upper part of the fluid-charged coarse-grained layer, which may be prone to earthquake-induced liquefaction, (ii) at the interface to the overlying low permeable layer, which may also represent a zone of contrast in shearing resistances, which act as preferential shearing planes, or (iii) in the lowermost part of the overlying low permeable layer, given that cohesive clay-rich sediments behave mechanically weak when fluids are provided10,48,49.

Implications for weak layer in low-latitude oceans

Climatic changes have controlled the depositional processes on several continental slopes and resulted in lithological contrasts50. Our study reveals that the weak layer of the giant Baiyun Slide Complex in the South China Sea was controlled by the alternating deposition of coarse (turbidite) and fine (contourite) grained units during sea-level variations. Focused fluid flow and overpressure likely reduced the resistive forces at lithological contrasts, promoting the development of the glide plane during submarine landslides.

On glaciated continental margins, mostly in mid- to high-latitude oceans, sedimentation shows pronounced alternations between coarse, stiff glacial deposits (e.g., diamictic debris and basal tills) and fine, soft interglacial sediments (e.g., hemipelagic, contourites and biogenic ooze)4,5,6,51. These distinct lithological contrasts, coupled with overpressure from gas hydrate dissociation, rapid loading, or diagenesis, promote the development of both ‘inherited’ and ‘induced’ weak layer4,10,47.

Climate changes also influence the depositional processes on non-glaciated (low latitude) continental margins through the effects of sea-level variations that change shorelines and river-shelf connections, resulting in the alternation of coarse-grained turbidites/debris and fine-grained hemipelagites/contourites. In the failed southeastern Brazilian margin, for example, coarse-grained turbidites were transported through the continental shelf and deposited on the slope during sea-level lowstand, resulting in fine-grained contourites deposited during sea-level rise52,53. In the northern Gulf of Mexico, large amounts of coarse-grained turbidites and sandy debris were delivered across shelf and deposited on the continental slope and in the deep ocean during glacial periods, whereas fine-grained deposition is more prominent in the inter-glacial periods54. A similar process has also been recorded in Western Sahara and SCS, where turbidites frequently passed through the shelf and canyons during sea-level lowstand but became absent during sea-level highstand42,55.

Compared with the glacigenic sediments on high-latitude margins, the turbidite deposits during sea-level lowstand result in more gradational lithology changes on non-glaciated low-latitude margins12. Nevertheless, recurrent giant submarine landslides, such as the Cap Blanc Slide and Mauritania Slide Complex offshore northwest Africa, and the Baiyun Slide Complex in this study, reveal fluid overpressure as an ‘universal’ factor to reduce the strength of specific intervals and generate the ‘induced’ weak layers on non-glaciated margins as well28,55,56 (Fig. 4). Considering the wide distribution of (non-glaciated) low-latitude continental margins, the formation mechanism of weak layer proposed in this study can serve as an analog for preconditioning factors responsible for the occurrence of submarine landslides in low-latitude oceans. Moreover, a similar mechanism could also be valid on non-glaciated continental margins in mid- or high-latitude oceans, where sea-level variations can alternate the sediment input and depositional systems, along with the existence of overpressure.

Data and Methods

Seismic and bathymetric data

This study utilized ~1600 km2 of high-resolution 3D seismic data and a 2D seismic profile, complemented by multi-beam and GEBCO bathymetric data covering the northern SCS (Fig. 1a). Multi-beam bathymetric data were collected using differential GPS positioning and processed using the software CARIS HIPS®. Horizontal and vertical resolutions for the bathymetric data are 100 m and 3–6 m, respectively. Seismic data were acquired and processed by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), with bin spacing ranging from 12.5 to 25 m. The seismic data have a frequency bandwidth of 30–45 Hz, providing an average vertical resolution of 8–10 m at the depth of the studied strata. Seismic interpretation was conducted using Schlumberger Petrel®, including the identification and auto-tracking of key seismic reflections, as well as the computation of thickness and attribute maps. Variance maps of key horizons were generated to highlight areas where seismic facies exhibit discontinuities, often correlating with the presence of faults, pipes, MTDs and canyons.

Well-logs of Well BY7-1-1

Located on the upper slope of the Baiyun Slide Complex, Well BY7-1-1 was drilled in 1987, from the modern seafloor at a water depth of 500 m, penetrating sediments from Late Miocene at 600 meters below the seafloor (mbsf) (Fig. 1). Porosity, permeability, and grain size were estimated by CNOOC from well-log data, which can be found in the Supplementary Data 1. Biostratigraphic correlation was performed by CNOOC, providing dates to key seismic horizons through core-log-seismic integration20. The top of the logged sequence is situated at a depth of ~300 mbsf, corresponding to a two-way travel time (TWT) of ~1000 ms, and is dated to ~2.4 Ma (Fig. 1b)20. Other key seismic reflections have been tied to dated cores as well, including Horizons H1, H2, H3, and H4, to 3.4 Ma, 3.8 Ma, 5.0 Ma, and 6.3 Ma, respectively (Fig. 1b)17,20. Surface samples from sites P1-P7 were acquired by the Guangzhou Marine Geology Survey57, while other surface samples plotted in Fig. 1a, including sites 18, 29, 69, 138, and 145, were obtained by the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences43.

Data availability

The seismic and well-log data used in this study were acquired from China National Offshore Oil Corporation. The seismic dataset is proprietary and not publicly available due to commercial sensitivity in hydrocarbon exploration and confidential data protection regulations. The original seismic profiles, uninterpreted maps and well-log data used in this study can be accessed via: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17420935.

References

Talling, P. et al. Large Submarine Landslides on Continental Slopes: Geohazards, Methane Release, and Climate Change. Oceanography 27, 32–45 (2014).

Locat, J., Leroueil, S., Locat, A. & Lee, H. Weak Layers: Their Definition and Classification from a Geotechnical Perspective. In Submarine Mass Movements and Their Consequences, 6th International Symposium 3–12 (Springer, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00972-8_1.

L’Heureux, J.-S. et al. Identification of Weak Layers and Their Role for the Stability of Slopes at Finneidfjord, Northern Norway. In Submarine Mass Movements and Their Consequences 321–330 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2162-3_29.

Gales, J. A. et al. Climate-controlled submarine landslides on the Antarctic continental margin. Nat. Commun. 14, 2714 (2023).

Montelli, A., Dowdeswell, J. A., Ottesen, D. & Johansen, S. E. Three-dimensional architecture and evolution of Quaternary contourite drifts on the Vøring Plateau, Norwegian Sea. Mar. Geol. 453, 106882 (2022).

Batchelor, C. L., Ottesen, D. & Dowdeswell, J. A. Quaternary evolution of the northern North Sea margin through glacigenic debris-flow and contourite deposition. J. Quat. Sci. 32, 416–426 (2017).

Rebesco, M. & Camerlenghi, A. Late Pliocene margin development and mega debris flow deposits on the Antarctic continental margins: Evidence of the onset of the modern Antarctic Ice Sheet?. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 260, 149–167 (2008).

Bellwald, B. et al. NE Atlantic continental slope stability from a numerical modeling perspective. Quat. Sci. Rev. 203, 248–265 (2019).

Berndt, C. et al. Temporal Constraints on Hydrate-Controlled Methane Seepage off Svalbard. Science. 343, 284–287 (2014).

Gatter, R., Clare, M. A., Kuhlmann, J. & Huhn, K. Characterisation of weak layers, physical controls on their global distribution and their role in submarine landslide formation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 223, 103845 (2021).

Urlaub, M., Geersen, J., Krastel, S. & Schwenk, T. Diatom ooze: Crucial for the generation of submarine mega-slides?. Geology 46, 331–334 (2018).

Miramontes, E., Garziglia, S., Sultan, N., Jouet, G. & Cattaneo, A. Morphological control of slope instability in contourites: a geotechnical approach. Landslides 15, 1085–1095 (2018).

Gatter, R. et al. A multi-disciplinary investigation of the AFEN slide: The relationship between contourites and submarine landslides. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 500, 173–193 (2020).

Wu, N. et al. Diagenetic priming of submarine landslides in ooze-rich substrates. Geology 51, 85–90 (2023).

Maselli, V. et al. Large-scale mass wasting in the western Indian Ocean constrains onset of East African rifting. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Zhao, F. et al. Along-strike segmentation of the South China Sea margin imposed by inherited pre-rift basement structures. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 530, 115862 (2020).

Sun, Q., Alves, T. M., Wu, S., Zhao, M. & Xie, X. Early Miocene magmatism in the Baiyun Sag (South China Sea): A view to the origin of intense post-rift magmatism. Gondwana Res 120, 127–144 (2023).

Sun, Q., Jackson, C. A. L., Magee, C. & Xie, X. Deeply buried ancient volcanoes control hydrocarbon migration in the South China Sea. Basin Res 32, 146–162 (2020).

Sibuet, J. C., Yeh, Y. C. & Lee, C. S. Geodynamics of the South China Sea. Tectonophysics 692, 98–119 (2016).

Qin, G. Application of micropaleontology to the sequence stratigraphic studies of Late Cenozoic in the Zhujiang River Mouth Basin. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 16, 17–23 (1996).

Miller, K. G. et al. Cenozoic sea-level and cryospheric evolution from deep-sea geochemical and continental margin records. Sci. Adv. 6, (2020).

Han, J., Xu, G., Li, Y. & Zhuo, H. Evolutionary history and controlling factors of the shelf breaks in the Pearl River Mouth Basin, northern South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 77, 179–189 (2016).

Zhuo, H. et al. Along-strike variability in shelf-margin morphology and accretion pattern: An example from the northern margin of the South China Sea. Basin Res. 31, 431–460 (2019).

Qi, K., Gong, C., Fauquembergue, K. & Zhou, Y. Did eustatic sea-level control deep-water systems at Milankovitch and timescales?: An answer from Quaternary Pearl River margin. Sediment. Geol. 439, 106217 (2022).

Gong, C., Wang, Y., Zhu, W., Li, W. & Xu, Q. Upper Miocene to Quaternary unidirectionally migrating deep-water channels in the Pearl River Mouth Basin, northern South China Sea. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 97, 285–308 (2013).

Li, W. et al. A giant, submarine creep zone as a precursor of large-scale slope instability offshore the Dongsha Islands (South China Sea). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 451, 272–284 (2016).

Sun, Q., Alves, T. M., Lu, X., Chen, C. & Xie, X. True volumes of slope failure estimated from a quaternary mass-transport deposit in the Northern South China Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 2642–2651 (2018).

Sun, Q. et al. Reconstruction of repeated Quaternary slope failures in the northern South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 401, 17–35 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Morphology, seismic characterization and sediment dynamics of the Baiyun Slide Complex on the northern South China Sea margin. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 171, 865–877 (2014).

Li, W. et al. The Baiyun Slide Complex, South China Sea: A modern example of slope instability controlling submarine-channel incision on continental slopes. Mar. Pet. Geol. 114, 104231 (2020).

Qin, G. Q. Late Cenozoic sequence stratigraphy and sea-level changes in Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea. China Offshore Oil Gas. 16, 1–10 (2002).

Alves, T. M., Omosanya, K. & Gowling, P. Volume rendering of enigmatic high-amplitude anomalies in southeast Brazil: A workflow to distinguish lithologic features from fluid accumulations. Interpretation 3, A1–A14 (2015).

Berndt, C. et al. Repeated slope failure linked to fluid migration: The Ana submarine landslide complex, Eivissa Channel, Western Mediterranean Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 319–320, 65–74 (2012).

Haq, B. U., Hardenbol, J. & Vail, P. R. Chronology of fluctuating sea levels since the Triassic.Science235,1156–1167 (1987).

Xie, H. et al. Cenozoic tectonic subsidence in deepwater sags in the Pearl River Mouth Basin, northern South China Sea. Tectonophysics 615–616, 182–198 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. South China Sea records Late Miocene reorganization of western Pacific deep circulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–11 (2024).

Yin, S. et al. Plate convergence controls long-term full-depth circulation of the South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 459, 107050 (2023).

Yin, S. et al. Isolation of the South China Sea from the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre since the latest Miocene due to formation of the Luzon Strait. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–9 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Controls of contour currents on intra-canyon mixed sedimentary processes: Insights from the Pearl River Canyon, northern South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 406, 193–213 (2018).

Lin, C. et al. Changes in inner- to outer-shelf delta architecture, Oligocene to Quaternary Pearl River shelf-margin prism, northern South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 404, 187–204 (2018).

Jiang, J. et al. Sequence architecture and depositional evolution of the Late Miocene to quaternary northeastern shelf margin of the South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 81, 79–97 (2017).

Qi, K. et al. Sea-level controls on terrigenous sediment input to deep water of the Pearl River margin since the last glacial maximum. Sediment. Geol. 486, 106939 (2025).

Zhong, Y. et al. Bottom water hydrodynamic provinces and transport patterns of the northern South China Sea: Evidence from grain size of the terrigenous sediments. Cont. Shelf Res. 140, 11–26 (2017).

Rebesco, M., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Van Rooij, D. & Wåhlin, A. Contourites and associated sediments controlled by deep-water circulation processes: State-of-the-art and future considerations. Mar. Geol. 352, 111–154 (2014).

Gay, A. et al. Anatomy of a fluid pipe in the Norway Basin: Initiation, propagation and 3D shape. Mar. Geol. 332–334, 75–88 (2012).

Cartwright, J. & Santamarina, C. Seismic characteristics of fluid escape pipes in sedimentary basins: Implications for pipe genesis. Mar. Pet. Geol. 65, 126–140 (2015).

Elger, J. et al. Submarine slope failures due to pipe structure formation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–6 (2018).

Horozal, S. et al. Factors for pre-conditioning and post-failure behaviour of submarine landslides in the margins of Ulleung Basin, East Sea (Japan Sea). Mar. Geol. 455, 106956 (2023).

Schöpfer, M. P. J., Childs, C. & Walsh, J. J. Two-dimensional distinct element modeling of the structure and growth of normal faults in multilayer sequences: 1. Model calibration, boundary conditions, and selected results. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 112, 1–15 (2007).

Catuneanu, O. Sequence Stratigraphy of Deepwater Systems. Deepwater Sedimentary Systems: Science, Discovery, and Applications (Elsevier Inc., 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91918-0.00010-4.

Rebesco, M. et al. Interaction of processes and importance of contourites: Insights from the detailed morphology of sediment Drift 7, Antarctica. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 276, 95–110 (2007).

Pandolpho, B. T. et al. Seismic record of a cyclic turbidite-contourite system in the Northern Campos Basin, SE Brazil. Mar. Geol. 434, 106422 (2021).

Alves, T. M. & Cartwright, J. A. Volume balance of a submarine landslide in the Espírito Santo Basin, offshore Brazil: Quantifying seafloor erosion, sediment accumulation and depletion. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 288, 572–580 (2009).

Damuth, J. E. & Olson, H. C. Latest Quaternary sedimentation in the northern Gulf of Mexico Intraslope Basin Province: I. Sediment facies and depositional processes. Geosphere 11, 1689–1718 (2015).

Henrich, R., Cherubini, Y. & Meggers, H. Climate and sea level induced turbidite activity in a canyon system offshore the hyperarid Western Sahara (Mauritania): The Timiris Canyon. Mar. Geol. 275, 178–198 (2010).

Förster, A., Ellis, R. G., Henrich, R., Krastel, S. & Kopf, A. J. Geotechnical characterization and strain analyses of sediment in the Mauritania Slide Complex, NW-Africa. Mar. Pet. Geol. 27, 1175–1189 (2010).

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Tan, M. & Cai, F. Deep-water deposition in response to sea-level fluctuations in the past 30 kyr on the northern margin of the South China Sea. Deep. Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 163, 103317 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the China National Offshore Oil Corporation for their permission to use the seismic and well data. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42306070), the Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Program (No. 2024A04J3812), and the development fund of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (SCSIO202206). Funding was provided to MU by the Helmholtz Association’s Initiative and Networking Fund (Young Investigator Group Grant no. VH636 NG-1617). The contribution of Michele Rebesco involving comparison with glaciated margins was supported by the PNRA IOPPIERS project (PNRA0000082). We are grateful to Shaoru Yin, the anonymous reviewer(s), and the editors, Shan Liu and Alice Drinkwater, for constructive comments that improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Li: Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition. Writing - Review & editing. Song Jing: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Review & editing. Morelia Urlaub and Michele Rebesco: equally contributed to the design of the work and participated in drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Shaoru Yin and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Shan Liu and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Jing, S., Urlaub, M. et al. Sea-level variations influence weak layer formation and submarine landslides on a low-latitude continental margin. Commun Earth Environ 6, 950 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02949-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02949-z