Abstract

Multiple climate extremes can coincide in time or happen sequentially and become a compound hazard. Recently, frequent occurrences of successive hot-pluvial extremes (SHPEs) have been presented, yet the risk of SHPEs on crop yield has not been investigated. Here we reveal peril of recurrent occurrences of SHPEs during intra-growing season and their connection with subsequent yield loss over breadbasket regions. Our results show an increasing trend in evolution of recurrent SHPEs during intra-growing seasons from 1979 to 2024. A significant risk of synchronized low crop yields is found in breadbasket regions, as shown by negative yield percentage changes and linear regression analysis. XGBoost classifier model predicts a negative likelihood of 49%, 50%, 49%, and 50% for maize, rice, soybean, and wheat yield responses to the emergence of frequent SHPE events, respectively. Alternatively, XGBoost regression surpasses and explains 36% of yield variability caused by recurrent occurrences of SHPEs globally for the studied crops, although it exhibits heterogeneities across different regions. The insights provide a foundation for considering the actual risk, which ultimately contributes to improving crop yield.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global production of primary crops experienced an increase of 52% between 2000 and 20201 as a result of advancements in technology and improved agricultural practices. However, climate change poses challenges to global food production2,3,4,5, particularly in marginalized communities6,7. It is imperative to understand the impact of weather conditions on the yield variations of staple cereals to adapt agricultural production to climate change. Numerous studies have primarily focused on the impact of concurrent hot-dry events8,9,10,11 and revealed that compound extremely dry and hot events have a greater impact on crop yields than a single extreme event. The spatial extent of concurrent drought-heatwaves, surpassing the sum of their individual impacts10,12, which substantially leads to crop damage. Although to a lesser extent and with more uncertainty and inconsistency, freezing and wet conditions have also been observed to reduce crop yields globally13.

In addition to univariate and concurrent extreme hydrometeorological events, a combination of sequential extreme events, such as successive hot-pluvial hydrometeorological extremes, has started to attract scientists and policymakers due to their devastating consequences. Nowadays, successive hot-pluvial extremes have been reported globally13,14,15 and across different regions of the world, such as growing threats across China16,17, South America18; and US19,20. Zhang and Villarini19 showed that hot and humid preconditioned weather can set the stage for mudslides and flooding events in the Central United States, leading to overwhelming infrastructure. The sequences of heatwaves and sub-daily extreme rainfall events in various regions of Australia21, which they described as “temporally compounding heatwave–heavy rainfall events”, noting that more frequent and more extreme wet days immediately following a heatwave pattern have been identified. South Korea’s hot-wet event in July 202022 and the UK thunderstorms and flash floods after scorching heatwave in August 2020 (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-53760283) were both typical cases. The observation of increased flood intensity in various regions has been triggered by a preceding heatwave, for instance, in China16.

One of the sectors that has been most profoundly devastated by the destruction of successive extreme events is agriculture. Sequential drying-wetting extremes have been observed in diverse and occasionally contradictory signaling pathways that either enhance crop phytohormonal and nutritional responses23,24 or reduce rice yields25. According to the 2017 special report by Food and Agriculture Organization and World Food Program26, a severe drought situation was exacerbated by subsequent heavy rainfalls in Sri Lanka that led to floods, landslides, and widespread crop failures in the country’s staple grains. As evidenced by the Langgewens Research Farm, heat stress cuts crop production efficiency by 1.75% per hot day, while rainfall boosts it by 1.45% per rainy day, and the combined heat and moisture stress reduces crop productivity overall27. Between 1982 and 2016, global crop production losses due to flooding were $5.5 billion28, which is expected to account for the exacerbation likely attributable to preceding heatwaves.

Although studies13,15,16,21,29,30,31 examine the annual and extended seasonal occurrences of global and country-level successive hot-pluvial extremes, their impacts on crop yields are globally unknown. Here, we investigate the risk of synchronized low crop yield associated with successive hot-pluvial extremes (hereafter SHPE), aiming at quantifying the yield sensitivity to SHPE abrupt alternation and modeling yield responses to the emergence of frequent SHPE signals. We hypothesize that the adverse interactions between SHPE events and crop-physiology responses, from the sowing of cereals to essential phenological phases in event-based agriculture, are significant and can have a synergistic impact on staple food yield. Unlike concurrent dry-hot extremes, the intertwined (hot to pluvial) climate extremes (as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1) can have cascading effects during critical phenological stages of crop development and at early stages of crop growth due to the crop’s limited capacity to recover from the intensity of events and the intertwined impact, which might pose significant cop physiological challenges, physical damage, and hinder the crop’s ability to carry out photosynthesis and nutrient transportation.

Hence, this study presents crucial insights into the impacts of frequent and intense SHPE events on the yield of the four main staple crops (maize, rice, soybeans, and wheat). We follow crop calendars to identify hotspot breadbasket regions that are likely to experience SHPE events, providing information for designing more effective, tailored policies for cropland protection to increase crop yields. When multiple extremes occur in rapid sequence, their impacts cascade to cause disproportionate damage and slow recovery. Therefore, a better understanding of successive hot-pluvial stresses needs to be carefully examined to develop adaptation strategies that mitigate the decline in agricultural productivity due to these underrated climate extremes. Such insights into crop yields are beneficial for future sustainable crop production and help to monitor the progress and resilience towards Sustainable Development Goal 2, which aims to promote sustainable food production.

Results

Historical evolution of the SHPEs occurrence during intra-growing seasons

We first identify the historical occurrences of SHPE events for the four selected croplands, following their crop calendars for the historical period (1979–2024). Our analysis quantifies the normalized SHPE occurrence rates, duration, and intensities across each cropland, allowing for comparisons across locations with different growing durations and providing a general overview of long-term variations. The frequency of SHPE occurrences per 100 days of crop growing season, revealing spatial pattern (Fig. 1) across the four croplands.

To account for varying growing seasons, we follow the combined crop calendar over a maize, b rice, and d wheat cropland, and follow a single season crop calendar over c soybean cropland. The occurrence rate of SHPE events is expressed by fixed scale days of the crop calendar. Units are per 100 days.

The low-latitude maize lands, including those in Africa (low-maize-yield area (Supplementary Fig. 2a)), Southeast Asia, and South America, are experiencing a high frequency of SHPEs (Fig. 1a), which exacerbate the challenges in these regions. These events over where maize yield variabilities are already higher (Supplementary Fig. 3a) show more prevalence occurrences than those in North America, Europe, and the Middle East regions (Fig. 1a). Similar incidences at the rice fields having dominant yields (Supplementary Fig. 2b) in South Asia, Central Africa and Madagascar, and South America broadly occurred (Fig. 1b). The incidences of SHPE events are also observed in the extensive soybean croplands in South America (e.g., Colombia, Bolivia, and Brazil), in Asia (e.g., India, and China), and Africa (Nigeria) during the local growing season (Supplementary Fig. 2c, Fig. 1c). The wheat lands in eastern United States, Ethiopia, India, Myanmar, and North China (Supplementary Fig. 2d) are relatively the vulnerable fields to these extreme events in the two growing seasons (Fig. 1d). These events during the wheat growing season are less pronounced compared to other crops, primarily due to the double and longer duration of wheat’s growing season, which extended from the main rainy seasons.

To enable a deeper understanding of cumulative stress on crops, we examine the historical duration of SHPEs that have evolved across the four croplands during the intra-growing seasons. Figure 2, represents the normalized durations of SHPE event occurrence, expressed as a percentage per length of the crop calendar. From a global perspective, SHPE experiences longer duration in the Southern Hemisphere than in the Northern Hemisphere, with strongly regional differences displayed in the Southern Hemisphere. For instance, maize and rice land experience spatially similar and pronounced longer durations of SHPEs (about 0.45% and above) (Fig. 2a, b) than soybean and wheat croplands (0.3% and above) (Fig. 2c, d) over the Southern Hemisphere from their length of crop calendars.

From the historical trend in SHPE events, we find a global tendency of a notable increase, although the rates of change in distribution vary spatially (Fig. 3). The increasing trends are significant in the maize fields of Colombia and Venezuela in South America, Central Africa and Southeast Asia, most of which exceed a magnitude of 0.5 events per combined calendars in a year (Fig. 3a). Significant increasing trends are also found in rice fields across South America, Central Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia regions, where exhibits a pronounced higher positive trend than in other regions (Fig. 3b). Soybean cultivation areas (Fig. 3c) in southern Brazil, Ecuador, India, and parts of Southwestern China, exhibit statistically significant upward trends. The wheat fields in South America, East Africa (Ethiopia), and Asia (South Asia and North China) also experience a significant increasing trend (Fig. 3d).

Changes in the normalized frequency of SHPE events per year during growing seasons of maize (a), rice (b), soybean (c), and wheat (d) for the periods 1979–2024 (events per crop calendar). Blank land regions denote areas that did not produce the specified crops. The significant trends at the 0.05 level are represented by black dots, estimated using the event/crop calendar.

Alongside the examination of spatial trend, we also examine the temporal evolution of annual SHPE event reoccurrences (Supplementary Fig. 4) and confirm a gradual increasing tendency in anomaly averaged over the croplands. The applied quadratic trend model captures gradual and potential nonlinear increasing temporal evolution. The concave-upward curvature in the fitted quadratic trend suggests that, not only are SHPE events becoming more frequent, but the rate of increase itself is accelerating, especially in the most recent decades. The monotonic increasing trends are statistically significant at Mann-Kendall test (p < 0.01). The goodness-of-fit for each crop is evaluated using adjusted R-squared (\({{{{\rm{R}}}}}_{{{{\rm{adj}}}}}^{2}\)) values, which ranged from 0.66 to 0.81, indicating that the quadratic model explained a substantial proportion of the variability (Supplementary Fig. 4).

We apply composite analysis32 to reveal the intensity of pluvial events with and without preceding hot events (Fig. 4). An increase in pluvial intensity following hot events is observed, particularly in maize land across Central and Southern Africa and western Europe (Fig. 4a), parts of South America and Central Africa rice land (Fig. 4b), South America soybean land (Fig. 4c), and European wheat land (Fig. 4d). Conversely, areas in China exhibit a lower pluvial intensity post-hot event for wheat land (Fig. 4d). Overall, 63, 62, 57, and 54% of maize, rice, soybean, and wheat lands are experiencing intensified pluvials following hot events on average, respectively. In the same fashion, we perform a composite analysis between the intensity of hot events that precede pluvial and hot without subsequent pluvial events (Supplementary Fig. 5) and find that the intensity of heatwaves preceding pluvial events is intensified compared to heatwaves occurring without subsequent pluvial events. This is particularly noticeable in US maize, soybean, and wheat fields, in Central and East African maize and rice fields, in Eastern European maize and wheat fields, in southern China’s rice and soybean fields, and in Iranian maize, rice, and wheat fields (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Each figure shows the change in pluvial intensity following hot events and pluvial intensity without preceding hot events for a specific crop: a Maize, b Rice, c Soybean, and d Wheat. Pink colors denote a negative change in pluvial intensity following a hot event minus pluvial intensity without preceding hot events, while blue colors indicate a positive change. Each subplot includes a pie chart showing the percentage of grid cells with positive (blue) and negative (pink) differences in pluvial intensity. Regions marked with yellow crosses represent the differences are statistically significant at the 0.05 level, estimated based on 1000 bootstrap iterations.

Risk of synchronized low crop yield associated with SHPEs

Having empirically investigated a plausible recurrence, duration, and evolution of SHPE events during the crop growing season, we employ a yield percentage change and sensitivity analysis to reveal the risks they pose to crop yield. Through the identification of the occurrences of SHPE events, the impact of SHPEs on crop yield for a given grid cell is quantified by comparing the crop yield under SHPE events with the yield expected from the long-term locally weighted regression smoothing model (LOWESS) non-linearity of the trend (5-year window) spanning the period limit to the years 1981–2016 (Data and Methods). Here, the yield percentage change reflects the yield departure from its long-term trend and is assumed to be induced mainly due to recurrent SHPE disruptions.

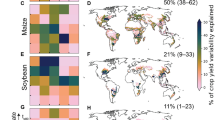

Our analysis of crop yield data shows that, while spatial patterns vary across crops, a substantial portion of each crop’s land area experiences yield reductions under these conditions. The event can lead to a decrease in crop yield of up to -4% across major agricultural regions compared to the expected yield based on long-term trends (Fig. 5). The analysis reveals that approximately 51–63% of maize, rice, and wheat lands show a negative yield percentage change globally (Fig. 5a, b, d), indicating that these crops are highly vulnerable to the SHPEs. Soybeans appear slightly more resilient, with about 48% of their land areas experiencing yield declines (Fig. 5c).

The crops are a maize, b rice, c soybean, and d wheat. The pie charts accompanying each map quantify the proportion of cropland experiencing positive (blue) versus negative (pink) crop yield percentage changes during SHPE events. The numerical values represent the yield percentage change under SHPE conditions. The yellow crosses denote statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

From the sensitivity analysis, a regression coefficient quantifies the variation in crop yield (tons per hectare) resulting from a recurrent occurrence of SHPE events. Figure 6 shows that majority of the maize, rice, and wheat croplands (52.7%, 62.4%, and 51.4%, respectively) and 47.4% of soybean land reflect a negative degree of sensitivity between recurrent occurrences of SHPE events and yields (Fig. 6a–d). Significant negative responses to SHPEs were found across Brazil rice and Central African maize and rice land (Fig. 6a, b), whereas in other parts, the sensitivities are sparse (Fig. 6a, d). The higher values of slope coefficients in both negative and positive directions indicate that signals of SHPEs are stronger (Fig. 6) than the yield response to the pluvial event without the preceding hot event (Supplementary Fig. 6), likely because of yield loss exacerbated by the compound stress of extreme hot and pluvial events. The regional k-means clustering of negative regression grid cells for each Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) region (Supplementary Fig. 7a–d) also exhibits yield sensitivity with higher percentage of grid cells in South American rice and wheat land, in Central African maize and rice land, in Southeast Asian maize and rice land, in South Asian rice, soybean, and wheat land, indicating widespread yield sensitivity to SHPEs in these individual climatic zones. This widespread prevalence of negative associations across these staple crop lands emphasizes the considerable threat posed by frequent occurrences of SHPE in association with yield loss.

The crops are maize (a), rice (b), soybean (c), and wheat (d). The maps show spatial patterns of yield sensitivity to SHPEs, highlighting regions where crop productivity is most affected by these compound events. Pie charts depict the proportion of croplands exhibiting positive (blue) and negative (pink) yield responses to each SHPE event. Yellow crosses indicate statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Modeling yield responses to emergence of frequent SHPE events

eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and random forest (RF) classifier algorithms allow us to estimate the likelihood of the coexistence of crop yield loss and SHPE events. Thus, we assess classifier models’ competence and robustness by conducting 10-fold stratified cross-validation and evaluating using metrics: F1-score, precision, and recall33,34,35 (presented in Supplementary Fig. 8a-c, Data and Methods), which examines the model performance in revealing the likelihood of crop yield loss under recurrent SHPE occurrences. XGBoost classifier, marginally a versatile machine-learning method36, suggests that occurrences of SHPE events globally have a likelihood of 49.0% for maize, 49.8% for rice, 49.3% for soybean, and 50.1% for wheat yield loss. Above 81.8, 80.0, 83.0, and 82.7% of measures of maize, rice, soybean, and wheat yield loss events are predicted correctly (Supplementary Fig. 8a) under 84.1, 85.6, 84.2, and 82.3% of a harmonic mean of precision and recall (Supplementary Fig. 8b), respectively. Consistently, this classifier model captures 84–88% of the four-crop actual yield loss cases and detects correctly (Supplementary Fig. 8c). The presence of skewed outliers in the model metrics indicates that the variability and potential instability in predictions of yield loss are large.

From this robust analysis technique, we reveal that considerable vulnerability, with notably high likelihood of maize yield loss in the Colombia and Venezuela (South America), Bantu regions (Africa) corn belt, in scattered eastern China and parts of Southeast Asian regions (Fig. 7a). The impact on rice yield is also prominent in South America, parts of Central Africa, Southeast Asia and East Asia (Fig. 7b). Southern Brazil, India, and the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River in China experience soybean yield loss compared with other soybean regions due to SHPE events (Fig. 7c). The widespread distribution of SHPEs in the wheat land region of the US, South America, South and East Africa, Europe, and Northeast and North China also results in yield losses with a chance of 60% and exceeds (Fig. 7d). Thus, XGBoost classifier identifies key regions where SHPE event-related yield losses are likely to be the most prominent. For example, in South America (notably Brazil), and across South and East Asia (Fig. 7c)—regions of global important soybean production (Supplementary Fig. 2)— and in Bantu region of Africa (Fig. 7a, b)—where is important maize and rice producing region, there is a high likelihood of yield loss due to SHPE events. However, developed countries experience less loss likelihood (Fig. 7). For instance, the vulnerability in US and eastern European maize lands (Fig. 7a), and in eastern US soybean land (Fig. 7c), underscores a lesser likelihood of SHPE-related yield losses. Similarly, RF classifier-meta estimator model demonstrates similar spatial patterns in detecting SHPE events that will have profound impacts on yield across different regions of croplands (Supplementary Fig. 9a–d). In addition, it performs slightly better than XGBoost in detecting SHPE events (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c).

The coincidences are quantified with values representing the maize (a), rice (b), soybean (c), and wheat (d) yield loss percentage predicted by an XGBoost classifier (in %) for the historical data from 1981 to 2016. The rest of the croplands (gray masks are similar to non-cropland) have insufficient data to validate a classifier model or no significant dependency corresponding to the effects of frequent SHPE events.

Crop yield reduction explained by recurrent SHPE event

XGBoost regression is implemented here based on gradient descent learning37 to explain the loss of crop yield under occurrences of SHPE events. The spatial distribution of coefficient of determination values shows where SHPEs are most predictive of yield variations (Fig. 8). This non-linear regression model likely reflects the fact that the tolerance levels of SHPE events for these crops may have lower thresholds for the successive extreme event stress across multiple regions. Among the common evaluation parameters used in regression, root mean square error (RMSE), R-squared (R²), and mean absolute error (MAE) are selected as reviewed38. XGBoost regression model coherently demonstrates a higher R² compared to RF across all crop lands (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating a better model fit and a stronger ability to explain variation in crop yield loss based on recurrent occurrences of SHPE features. This model explains the non-linear relationship between crop yield sensitivity and recurrence of SHPEs, accounting for global variance of approximately 36.2% in maize, 40.9% in rice, 42.1% in soybean, and 37.4% in wheat yield. RMSE is 0.57 t ha-1, 0.56 t ha-1, 0.26 t ha-1, 0.57 t ha-1,and average magnitude of the errors between predicted and actual values is 0.43 t ha-1, 0.42 t ha-1, 0.20 t ha-1, 0.44 t ha-1 for maize, rice, soybean and wheat, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8d-f). Presence of the outliers indicates that the model underperforms in the number of grid cells.

Croplands exhibiting statistically significant (p < 0.05), in which XGBoost regression model explained the frequencies of SHPE events causing maize (a), rice (b), soybean (c), and wheat (d) crop yield loss in each grid cell are shown in colors. Non-cropland or cropland grids with insufficient values, and grids estimated by XGBoost algorithms with no significant dependency, correspond to the effects of frequent SHPE events (p > 0.05) for the historical period 1981 to 2016, and are presented by the gray masks.

Yield loss attributed to growing season reoccurrences of SHPE event is explained remarkably across four croplands in South America (Fig. 8a–d). In addition, maize and rice fields in Central and Southeastern African countries (Fig. 8a, b), rice fields in Southeast Asia (Fig. 8b), and soybean fields in India (Fig. 8c) also exhibits a broad distribution of high yield loss. Likewise, wheat yield variability in the eastern US, South Asia, and North China (Fig. 8d) is also markedly influenced by SHPE events. The result in Fig. 8d demonstrates widespread high wheat yield sensitivity to the recurrent SHPE events, particularly evident in South America (wheat belts of Argentina). Maize yield losses in the US, Europe, and northern regions of East Asia (Fig. 8a), rice and soybean yield losses in East Asia (eastern China) (Fig. 8b, c), and wheat yield losses in Europe and North Asia (particularly in northern Central Asia and northeastern China) (Fig. 8d) are explained to a lesser extent. This model anticipates a global average yield variance of 36.2, 40.7, 42.1, and 37.4% attributed to recurrent SHPE events, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Meanwhile, the RF regression model result is shown in Supplementary Fig. 10 to compare the explanatory power of yield loss due to SHPE event. It shows a spatial consistency with the result of XGBoost regression.

Discussion

This study reveals the impact of SHPE events on crop yield loss using empirical and parametric to non-parametric statistical methods, following the presentation of the historical pattern of recurrent occurrences, durations, and trend of SHPE events during the intra-crop growing seasons of the four crops. In hotspot breadbasket regions, the notable increase in the historical evolution of recurrent occurrences of SHPE events, along with an increasing trend of tendency and prolonged percentage of crop calendar under SHPE events, taken together, underscore the need for climate-smart agricultural practices and targeted adaptation strategies to mitigate the impact of such a sequential event in both low-yielding cropland and in critical crop-producing regions. Regions with low-yield (Supplementary Fig. 2), have the greatest increasing trend in SHPE events (Fig. 3) and a prolonged percentage duration of SHPEs relative to the length of the crop calendar (Fig. 2), particularly in South America, the Sahel, and Southeastern Africa, and South Asia. This phenomenon can pose considerable challenges by increasing yield loss for farmers already struggling with the effects of climate change in these regions. Again, key rice-producing regions with a high level of internal consumption39 exhibit a pronouncedly significant increasing SHPE trend. In general, in the living conditions of marginal communities and non-developed countries that experience food insecurity40, SHPE events emerge frequently (Fig. 1) and for a prolonged duration of production periods (Fig. 2). This kind of phenomenon in regions of staple crop production heightens the risk of crop failures and yield reductions, posing a significant threat to global food security.

Moreover, majority of breadbasket regions also receive a higher intensity of pluvial following hot events than that of pluvial events without a preceding hot event. This result is consistent with the findings in the case studies in China, which presented an average of 26% of heatwaves being succeeded by heavy rainfall16, with shorter and more intense heatwaves being particularly prone to intensified rainfall phenomena in China41. It is also consistent with a global study that presented an amplification of extreme precipitation to the preceding heat-stress13. Besides the observed trend of intense SHPE events, these events inflict significant stress on crops, although the subsequent rainfall might initially seem beneficial for them. This is like other univariate variables, for instance, excessive rain in US can reduce maize yield up to -34% relative to the expected yield from the long-term trend, comparable to up to -37% losses by extreme drought found in Li et al.34; the French wheat yields were reduced by 30% in 2016 after the combination of a successive late autumn heatwave and spring pluvial42. Thus, we can understand that the effect of SHPEs’ combined factors on crops is not always additive, but can exert both detrimental and beneficial impacts on crop yield, and its sign varies regionally.

In our results, the yield percentage change and yield sensitivity to events are described by linear regression. This highlights the synchronized threat of SHPE events to crop yield loss, indicating that yields tend to decline when these events increase. The pluvial events alone span a negative sensitivity on a broader extent of cropland, but are smaller in magnitude compared to the sensitivity of yield to SHPEs, suggesting a broader yet less impact from pluvial events alone. Conversely, the integration of SHPE events versus crop yield exhibits higher values in both negative and positive directions, demonstrating a more substantial and more variable influence on crop yield—likely the synergistic impacts amplify yield losses beyond those induced by pluvial events alone. The intensification of pluvial events triggered by hot events13,41,43 and their intertwined (hot to pluvial) extremes transitions can reflect intertwined crop physiological responses (stomata close-open-close), which might pose considerable challenges from crop physiological to physical damage beyond the normal natural cycle (Supplementary Fig. 1, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus, the synergistic impacts are probably due to the lower physiological tolerance to hot and pluvial conditions intertwined in crops as well. For instance, a hot event during the early vegetative stage, followed by excessive rainfall during the sowing period, can dry the soil, hindering growth due to waterlogging and nutrient leaching. And during flowering, it can also severely limit grain filling, increase post-flowering mortalities and then impair pollination, cause stress and disrupt critical growth stages, which has the potential to lead to yield failures. The risks and opportunities for crop yields will largely depend on how the crop’s physical and physiological responses adapt to these SHPE events. Morphological and physiological susceptibility and tolerance of maize44, rice45, and wheat46 plants may be exacerbated by these intertwined phenomena and may go beyond the impact of separate hot or (and) pluvial extremes, similar to the mathematical concept of “1 + 1 > 2”, where the total impact is not just two but surpasses it. The observed patterns emphasize the need for tailored and crop-specific adaptation strategies that take into account SHPE events in areas where these crops are cultivated. However, in developed countries, such as in maize lands of the US and Eastern Europe, and in soybean land of the eastern US, they underscore a lesser likelihood of SHPEs-related yield losses (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Fig. 10), likely due to enhanced resilience and adaptive strategies that mitigate the impacts of such sequential extreme events. Moreover, previous findings also reveal the expected exacerbation of future SHPE events in different climate scenarios13,14,15,43 and indicate an increased risk to crop yields.

While the underlying drivers of these intertwined extreme events remain less understood, it is imperative to examine them. The detailed mechanism behind the interconnection needs to be further studied, besides the diagnosis of large-scale atmospheric conditions by Zhou et al13., particularly the role of large-scale climate phenomena, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). According to Heino et al. (2018), two-thirds of the global cropland areas are impacted by climate oscillations47. From these studies, the impact of ENSO oscillation on crop productivity leads to food insecurity in many parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Synchronization of different ENSO phases and SHPE events may lead to increased yield loss across various cropland regions, warranting further investigation to elucidate the impacts of SHPE events induced by ENSO phases. Meanwhile, the impact of SHPE events on rainfed and irrigated croplands may have distinctions and respond differently in each type of cropland. For instance, Mishra et al. (2020) highlight that intensive irrigation in South Asia (India, among top countries in irrigation systems, Pakistan, and parts of Afghanistan) reduces land surface temperatures but increases humid heat-stress, as measured by wet-bulb temperature48. This elevated moist-heat stress can also exacerbate yield losses in irrigated croplands by creating unfavorable conditions for crop physiology. Similarly, Haqiqi et al. (2021) demonstrated that wet-heat extremes are more damaging than dry-heat for corn crops across the US49.

The field of machine learning provides a variety of advanced statistical models that are increasingly used for more accurate estimations of relationships between yield and climate extremes12,50,51. This study employs XGBoost and RF regression models to reveal the power of explaining crop yield variability due to SHPE events; XGBoost outperforms the RF regressor. The model indicates the region’s need crop-specific adaptation strategies to reduce the vulnerabilities to these successive extreme conditions. It explains that a global average of 36% recurrent occurrences of SHPE events can lead to yield losses in four major crops, while exhibiting a wide range of heterogeneity and non-linear relationships across different regions. The anticipated tolerance levels of major crops are expected to be low during the growing season in regions frequently affected by SHPE events. Specifically, maize and rice in South America and parts of Central Africa; soybean in South America, India, and China; and wheat in the eastern US, South America, in scattered areas across Asia, and eastern China, are expected to exhibit low resilience to the growing season reoccurrences of SHPE events. The explanatory power of XGBoost algorithm has previously been employed and a more effective model on the concept of boosting has been used to detect the spatial variation in crop yield under different climate variables12,37,52,53. Alternatively, the RF regression has been used to obtain the crop response to drought timescale51, in regional crop yield predictions36. Owing to such distinctive explaining power, the XGBoost regression model underscores the considerable risk of yield variabilities for all four main crops due to frequent occurrences of SHPE events.

Notwithstanding the valuable insights this study provides, it is essential to consider the following limitations. (1) The SHPE analysis for crop-growing seasons during the period 1979–2024 uses crop-specific calendar dates to identify SHPEs, focusing on the 90th percentile thresholds tailored to local climate during active agricultural periods. One drawback of this threshold is the tendency to overestimate the occurrence of extreme events in areas where no disasters occur. Secondly, in areas where more than 10% of disasters are recorded, only the top 10% of events are considered, while the remaining events are underestimated. Although quantile-based thresholds have inherent limitations in capturing heterogeneity, here we robustly quantify extreme conditions by tailoring thresholds in evaluating relative to the local climate of each cropland grid cell, on a given date of crop growing day of years, which is abnormal from the climatology that the crop is adapted to on that particular crop growing day of year. This approach excludes non-growing seasons and colder periods, which are distinguished from year-round conditions. It provides a more meaningful assessment of agriculturally non-relevant extreme events relative to the local climatology to which crops are adapted during the growing season. (2) The temporal scope of gridded crop yield data is confined to the years 1981 to 2016, and has no extensions after 2016. This constrained sample size may limit the generalizability of our findings and increase the variability of model performance estimates, particularly for the minority class (“yield loss”) in our imbalanced dataset. However, within our capabilities, we address the class imbalance issue using stratified sampling, where “no yield loss” is significantly more frequent than “yield loss”. We also employ bootstrapping to increase the sample size by generating diverse combinations of the original 36 years of data points. Detailed descriptions of reducing fitting noise in the training set and increasing ensemble diversity and enhancement of robustness are presented in Data and Methods Section (3) Despite the usefulness of using fixed cropland and crop calendar over the 36-year study period in ensuring consistency in spatial and temporal analyses of capturing long-term yield responses to SHPEs, it failed to account for the potential shifting of planting to harvesting dates and in considering new cropland. The same drawbacks were also encountered in prior studies54,55. Studies10,54,56 have used this crop-specific fractional harvested area dataset57 to analyze the impact of different climate changes on crops. Again, the crop calendar data that we obtained from58 has been used in previous studies10,12,54,59,60,61. However, we recommend future regional or country-level studies to consider the twenty-first-century soybean land expansion across South America62-recent expanded cropland and a flexible crop calendar following seasonal rainfall onset around planting dates55. (4) Our study didn’t treat rainfed and irrigated croplands separately. We acknowledge that rainfed and irrigated croplands respond differently to climate extremes. Unfortunately, datasets do not incorporate crop growing seasons with crop yield data, as rainfed and irrigated croplands are consistently compared at global scales. As a result, our study spanned two crop-growing seasons for maize, rice, and wheat, and one season for soybeans, with the crop yields obtained from these cultivation seasons. The findings of Mishra et al. (2020)48 and Haqiqi et al. (2021)49 suggest that the impact of SHPE events may differ across croplands in rainfed and irrigated systems. Based on our findings, further research is needed to understand the details of SHPE and crop physiology interactions, incorporating non-climatic conditions, such as soil type and fertility, topography, climate zone, irrigation, and rainfed agricultural practices, and crop growth stages into the model, which ultimately contributes to the improvements of crop yield. Additionally, we advise integrating diverse machine learning models into dynamic decision support systems to enhance mechanistic crop models, thereby helping capture more complex non-linear relationships between such kind of sequential climate variables and crop yield loss.

Conclusion

This study reveals the risk of recurrent SHPE events, which can lead to significant yield losses in major breadbaskets. The occurrences of SHPEs during the intra-crop growing seasons of the four crops show heterogeneity in their frequencies and durations, with this being more pronounced in the global South. Our empirical results suggest that the historical hot event favors more occurrences of intensified pluvial events in the crop growing periods. Yields are more responsive to SHPE events in both negative and positive directions compared to univariate pluvial events that do not have preceding hot events.

The model indicates that hotspot regions are more prevalent in marginal communities and non-developed countries experiencing food insecurity, particularly in the Bantu region of Africa, South America, and South and Southeast Asia. These areas are characterized by frequent and prolonged incidences of SHPE events, highlighting the need for climate-resilient agricultural practices and tailored adaptation strategies to mitigate the risk of synchronized low crop yields resulting from such sequential events. Conversely, developed countries experience the loss to a lesser extent; maybe, developed countries mitigate the impact with latest technologies and a mechanized production approach.

Data and Methods

Meteorological Data

The temperature and precipitation data are obtained from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) fifth-generation atmospheric reanalysis (ERA5) at a resolution of 1˚ × 1˚. The daily maximum temperature (Tmax) is calculated using the maximum of the 24-hour data, and hourly precipitation data are aggregated to total precipitation at a daily time step. We limit our analysis to post-1979 (1979–2024) with the base period of 1981–2010 to minimize known biases in ERA5 for the pre-satellite period in climate datasets.

Crop yield Data

The crop yield data is retrieved from Global Dataset of Historical Yield (GDHY) aligned version v1.2 + v1.3 data from T. Iizumi63. The GDHY is a hybrid of agricultural census statistics and satellite remote sensing crop yield data from the United Nations FAO national statistics. It is gridded to a 0.5° resolution for ~20,000 subnational political units over 1981–2016, and the sparse GDHY dataset in the pre-1990s is addressed using backward linear interpolation. Studies in the past28,61,63,64,65,66 have been used this data source. The focus of this study is on the globally dominant staple crops, including maize, rice, soybeans, and wheat, which yield high calories and are distributed worldwide. The extent of maize, rice, soybean, and wheat cropland area fraction is provided by the cropland and pasture area in the 2000 Dataset57. These crop-specific fractional harvested area data represent the average fractional proportion of a grid cell that is harvested in a crop during the 1997–2003 era. These data are derived by combining agricultural inventory data and satellite-derived land cover data at a 5 min resolution. This dataset has been used in previous studies10,54,56 to analyze the impacts of different climate change scenarios on crops. We coarsen the grid of each cropland area into 10 resolutions to match the resolution of meteorological variables. We obtain crop calendar data from58, which is used in previous studies10,12,54,59,60,61. To represent the growing season, the SHPE climate extremes are extracted from the average crop sowing periods through the end of harvesting periods based on a global crop calendar.

Definitions of successive hot-pluvial extreme (SHPE) events

A heatwave event is defined as when the daily Tmax exceeds the 90th percentile of that day, estimated from the base period, for at least three consecutive days23,36. The 90th percentile will capture more events of bivariate extremes than the 95th percentile. The threshold for Tmax is calculated for each grid cell using a 5-day running window, based on the 90th percentile for each day, as recommended by the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices67. The calculation of percentiles is done empirically on the pooled data from the base period, covering 30 years and ±2 days, resulting in 30 × 5 = 150 values. The 5-day surrounding running window helps to consider only the specific days of the crop calendar rather than the whole months or the seasonal moving average. A pluvial event is determined when daily precipitation exceeds the 90th percentile of the daily precipitation13,21 from Pt ≥ 1 mm for one or more consecutive days of each crop calendar, which helps to filter out persistently dry regions to focus on agriculturally relevant wet extremes within the local crop growing period.

SHPE events refer to the phenomenon of hot events being followed by pluvial within a seven-day temporal interval13,15,16,30. We adopt the explanation of Sun et al.15 and You et al.30 regarding the selection time interval of up to 7 days to balance the trade-off between potential impact and the duration of hot extremes, which is longer than three consecutive days and a daily duration of pluvial events. As the 7-day window length shrinks, it would limit crop recovery from the preceding hot hazard, and when selecting SHPEs that last more than the 7-day window, the crop can gain time to recover, which results in situations similar to univariate hot or pluvial extremes. The regimes of the SHPEs capture primarily more events during warmer seasons. To avoid redundancy, we determine the start and end times of each SHPE event from the start of hot to the end of pluvial event in the crops calendar.

Analyzing the characteristics of SHPEs

We calculate SHPE by considering the combined (except soybean) growing period from the beginning of sowing to the end of the harvesting period. One SHPE event can occur during both overlapped crop seasons of a harvested area, but here we consider only one phase of the crop seasons. The trend in the frequencies of SHPE events are assessed using Sen’s slope for the trend and the Mann–Kendall test for the statistical significance, both of which are calculated through an iterative method to take into account the autocorrelation that was proposed by Zhang et al. (2000)68, modified and refined by Wang & Swail (2001)69 and Qian et al.(2019)70. To account for varying crop growing season durations across different regions, we normalize the crop calendars to a common scale and compute them as follows, and expressed in percentage.

Where \({{{SHPE}}_{{duration}}}_{i,j}\) is the average duration of SHPE occurrences per crop calendar. \({H}_{i,j}\) is day of hot event onset at grid cell \((i,j)\); \({P}_{i,j}\) is day of cessation of pluvial event following the hot event at grid cell \((i,j)\); \({{SHPD}}_{i,j}\) is the duration of SHPE events at grid cell \((i,j)\) in percent; \({D}_{i,j}={P}_{i,j}-{H}_{i,j}\) is the duration of a single SHPE event at a grid cell \(\left(i,j\right)\); \({{{CC}}_{l}}_{i,j}\) is the length of crop calendar; \({{{CS}}_{n}}_{i,j}\) is number of crop-growing seasons for the entire 46 years; \({n}_{i,j}\) is number of SHPE events at \(\left(i,j\right)\); \({H}_{i,j}^{(e)},{P}_{i,j}^{(e)}\) is start and end day of the \({e}^{{\mbox{th}}\,}\) event, respectively. For instance, if a grid cell has 250 days of crop calendar length and 36 days of them (\({\sum }_{e=1}^{{n}_{i,j}}\left({P}_{i,j}^{(e)}-{H}_{i,j}^{(e)}\right)\)) are under SHPE, then \(\frac{1}{46}\times\frac{36}{250}\times100 \%\) = 0.31% of the durations are under SHPE per crop growing season. This allows comparison across locations with different crop durations.

Composite analysis

At broader spatial scales, composite analysis can be used to reveal the linkage between extremes and yield impact32. We employ a composite of a pluvial (hot) intensity to understand the detailed intensity of pluvial (hot) events with preceding hot (following pluvial) events and pluvial (hot) without preceding hot (following pluvial) events over the four croplands as presented in Fig. 4, and Supplementary Fig. 5, respectively. To estimate informative confidence intervals and test the statistical significance non-parametrically, a 1000-iteration bootstrap efficient approach has been used.

Crop yield percentage change (η)

To quantify the impacts of SHPE on crop yield, first, the crop yield changes relative to a 5-year window temporal trend are removed using a LOWESS71. The LOWESS method applied in this study can account for the possible non-linearity of the trend spanning the period from 1981 to 2016 in the double-filter adopted method. This approach begins with conducting the LOWESS regression model using a 5-year (t − 2 to t + 2) window and a smoothing span (f) of 0.14 over 36 years and has been used before by Kim et al. (2023)28. To test the arbitrariness of our selections, we conduct sensitivity analyses using alternative 3, 4, 6, and 7-year windows, each with a corresponding span f = 0.08, 0.11, 0.17, and 0.20 (Supplementary Fig. 11). The results show minor differences. Thus, our choice of span and moving average does not unduly influence the conclusions, and the identified yield anomalies are structurally robust under reasonable detrending assumptions (Supplementary Fig. 12). In terms of the two RMSE and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) combined metrics, the f = 0.14% of fraction under 5-year window parametrization has overtaken the third rank next to f = 0.08%, 3-year window, and f = 0.20% under 7-year window. For instance, the parameter set has been selected with moderate RMSE (0.55) and LOOCV score (0.33). Supplementary Fig. 13 also confirms that the general patterns remains stable, demonstrating that our conclusions are not overly sensitive to these smoothing parameters. Thus, the yield in t (5-yr) window choices allows us to exclude long-term yield trends associated with long-term climate change, and other non-climatic factors like technological advancement, land use and soil management changes, genetic improvements, policy and economic shifts, and infrastructure development, while retaining short-term variability (e.g., weather fluctuations). This 5-yr window is long enough to account for typical climate cycles, such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation phenomenon. LOWESS is recognized as a highly effective detrending technique for analyzing crop yield data66, which allows us to explain how crop yield losses are related to the occurrences of SHPE events. Through the identification of the recurrent occurrences of SHPE years, the impact of SHPE event on crop yield for a given grid cell can be quantified by comparing the crop yield under SHPE year with the yield expected from the long-term LOWESS trend. The calculation of yield percentage change(η) is modified from Gimeno & Miralles66 and by Li et al.34 as \({\eta }_{i,t}=\frac{1}{n}{\sum }_{k=1}^{n}\left(\frac{{Y}_{i,t}-{\mu }_{i,t}}{{\mu }_{i,t}}\right)\times 100 \%\), where \({Y}_{i,t}\) is crop yield (t ha−1) and \({\mu }_{i,t}\) is the long-term trend obtained by 5-year moving average LOWESS (t ha−1). This yield percentage change reflects the yield departure from its long-term trend.

Linear regression

This regression model is prescribed based on the historical linear relationship between the occurrences of SHPE events and crop yield. We estimate the historical yield sensitivity to the events as the slope coefficient. The slope coefficients and associated p-values for each grid cell where detrended yields are regressed against the detrended frequencies of SHPE. To assess regional vulnerability, we calculate the percentage of grid cells within each IPCC region72 that exhibit negative regression slopes. We then apply k-means clustering to group grid cells with similar slope characteristics for each IPCC region. Focusing on identifying clusters with negative slopes (indicating yield losses associated with SHPEs), we compute the percentage of grid cells exhibiting negative slope coefficients for each IPCC region, relative to the total number of cropland grid cells in that region. This indicates the association of increased SHPE frequency with declining crop yields in an individual climatic zone.

eXtreme gradient boost (XGBoost) classifier

This study evaluates the efficacy of machine learning models in explaining the four major staple crops’ yield loss due to SHPEs. Statistical models often encounter various challenges, such as overfitting, hyperparameter tuning, insufficient data, and data quality issues, which are commonly observed in crop modeling. To overcome these challenges, we implement cross-validation (CV), hyperparameter tuning, and bootstrapping approaches. These techniques help to evaluate the performance of the models, fine-tune hyperparameters, and enhance model generalization. The XGBoost classifier method is a new member of the ensemble learning family that exhibits robust performance, and it is an improved version of the gradient boosting decision tree33. This study involves a comparative analysis of the XGBoost classifier with RF classifier methods, in order to produce more robust and reliable results on the potential occurrence of recurrent SHPE events that lead to crop yield reduction. The SHPE reoccurrence indices (SHPI) and standardized crop yield indices (SCI) are labeled as SHPI > 0 and SCI < -σ, where a crop yield reduction is defined as the case when detrended crop yield, transformed into its standardized form, falls below -σ. Here, σ represents one standard deviation of the detrended crop yield anomalies.

The stratified sampling model configuration accounts for class imbalance, where “no yield loss” is significantly more frequent than “yield loss”. Specifically, we use the ‘stratify=labels’ parameter in the train-test-split function (with test-size = 0.2 and random-state = 42) to prevent skewed class distributions in the training and testing subsets, thereby mitigating potential biases in model performance. The ‘test-size = 0.2’ ensures approximately 7 test samples and 29 training samples from our 36 annual grid-wise data points, which is a reasonable split given the small dataset size, with random-state = 42 ensuring reproducibility. To enhance robustness, we implement 10-fold stratified CV. The ‘scale_pos_weight’ in XGBoost and class-weight = ‘balanced’ in RF handles crop yield data imbalance (to emphasize the minority class) during training based on the negative to positive sample ratio. Additionally, we employ the probability calibrations via Calibrated-Classifier-CV to improve the reliability of predicted probability estimation with Platt scaling (“method = ‘sigmoid’”). This is to align the predicted probabilities of crop yields with observed SHPE events, which is essential for conditional probability outputs in our yield loss prediction task. The probability curve + F1 max threshold tuning are used for a better decision boundary for rare crop yield loss classes. We use a 10-fold Stratified-K-Fold CV to preserve class proportions (imbalance) across folds for a reliable estimate of regression model performance. In the gradient boosting ensemble, 500 bootstrap samples are utilized to reduce fitting noise during training, increase ensemble diversity, and reduce correlation between trees.

The classifier model’s competence and robustness are evaluated using precision, which measures the accuracy of predicted “yield loss” events; recall, which captures the effectiveness of detecting actual “yield loss” cases; and the F1-Score, a harmonic mean of precision and recall evaluation indicators. Instead of a fixed 0.5 threshold, we use precision-recall curve threshold optimization to find the threshold that maximizes the F1-score for each grid, for better detection of rare “yield loss” events. The XGBoost classifier approach is a cornerstone tool for assessing the likelihood of recurrent SHPE occurrences and crop yield losses due to its robustness and versatility. Confidence intervals for predicted probabilities are calculated using bootstrapping iterations.

We employ an RF classifier machine learning model, a meta estimator that trains multiple decision tree classifiers on various subsets of the dataset to evaluate the likelihood of crop yield reduction in the presence of frequent SHPE events. Within each node of the trees constructed using bootstrapping, a specific number of randomly selected parameters —such as 500 trees, two minimum leaf sizes, and 10 folds for CV —are set with the same labeling of SHPI and SCI, following the splitting approach of the XGBoost classifier. Subsequently, k-fold CV is carried out for model evaluation. This classifier is used to estimate probabilities of yield reduction on the test set based on SHPE indicators by leveraging the trained scikit-learn ensemble classifier algorithms73.

eXtreme gradient boost (XGBoost) regression

We use XGBoost- a scalable machine learning algorithm proposed by Chen and Guestrin74 to explain the variability of crop yield under the occurrences of SHPE events. In earlier studies, the crop response to climate extremes has been detected with interpretive XGBoost machine learning12,37,52,53,75,76. The basic principle of this approach is to consider a multiple of “weak” learners that are combined to produce a single “strong” learner more effectively on the concept of boosting37, through the iterative expansion of individual decision trees52,77. Owing to such distinctive advantages, XGBoost is an advanced method of interpreting results from tree-based models. The coefficient of determination (R²) reveals the degree of non-linear relationship between the detrended occurrences of SHPE and crop yield variabilities. We choose the XGBoost regression hyperparameter grid (n_estimators=500, learning_rate=0.01, max_depth=10, subsample=0.8, colsample_bytree=0.8, gamma=0.2) as a conservative, regularized setup to balance learning stability and generalization, suitable for imbalanced data with 1000 bootstrapping samples.

For tuning purposes, we split the number of SHPE events (features) and crop yield (labels) datasets as 80%/20% for training and validation subsets, respectively. The hyperparameters, the number of (1000) gradient boosted trees with a maximum depth of ten decision trees, are trained iteratively with 10-fold stratified CV. The CV tests approach within each of the ten CV folds is used to calculate the mean of the observed R2 in the occurrences of SHPE as the feature that explains the loss in crop yield. A bootstrapping approach is implemented to estimate the loss of R² values and to analyze the statistical significance of the observed R² compared to what would be expected by chance using P-value at a level of 0.05. The performance of the regression models is assessed using adjusted R² to measure goodness-of-fit while accounting for the number of predictors, alongside RMSE and MAE33,34,35.

Data availability

The crop yield data and the growing season calendar data are both publicly available at GDHY and Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (https://sage.nelson.wisc.edu/), respectively. Both the hourly temperature and precipitation data are available at ERA-5 Land hourly datasets https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-land?tab=download.

Code availability

The codes necessary to conduct the analysis and create the figures presented here are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

FAO. Agricultural production statistics. FAOSTAT Anal. Br. 41 (FAO, 2020).

Ray, D. K., Gerber, J. S., Macdonald, G. K. & West, P. C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 6, 5989 (2015).

Tigchelaar, M. et al. Compound climate risks threaten aquatic food system benefits. Nat. Food 2, 673–682 (2021).

Kitole, F. A., Mbukwa, J. N., Tibamanya, F. Y. & Sesabo, J. K. Climate change, food security, and diarrhoea prevalence nexus in Tanzania. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 394 (2024).

Mehrabi, Z. et al. Research priorities for global food security under extreme events. One Earth 5, 756–766 (2022).

Bedasa, Y. & Bedemo, A. The effect of climate change on food insecurity in the Horn of Africa. GeoJournal 88, 1829–1839 (2023).

Karki, S. Impacts of climate change on food security among smallholder farmers in three agro-ecological zones of Nepal. South African J. Agricult. Ext. 52, 16282 (2020).

Bevacqua, E., Zappa, G., Lehner, F. & Zscheischler, J. Precipitation trends determine future occurrences of compound hot–dry events. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 350–355 (2022).

Wu, X. & Jiang, D. Probabilistic impacts of compound dry and hot events on global gross primary production. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034049 (2022).

He, Y., Hu, X., Xu, W., Fang, J. & Shi, P. Increased probability and severity of compound dry and hot growing seasons over world’s major croplands. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153885 (2022).

Lu, Y., Hu, H., Li, C. & Tian, F. Increasing compound events of extreme hot and dry days during growing seasons of wheat and maize in China. Sci. Rep. 8, 16700 (2018).

Heino, M. et al. Increased probability of hot and dry weather extremes during the growing season threatens global crop yields. Sci. Rep. 13, 3583 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Amplified temperature sensitivity of extreme precipitation events following heat stress. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 243 (2024).

Zhou, Z. et al. Global increase in future compound heat stress-heavy precipitation hazards and associated socio-ecosystem risks. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 33 (2024).

Sun, P. et al. Compound and successive events of extreme precipitation and extreme runoff under heatwaves based on CMIP6 models. Sci. Total Environ. 878, 162980 (2023).

You, J. & Wang, S. Higher Probability of Occurrence of Hotter and Shorter Heat Waves Followed by Heavy Rainfall Geophysical Research Letters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094831 (2021).

Chen, Y., Liao, Z., Shi, Y., Li, P. & Zhai, P. Greater flash flood risks from hourly precipitation extremes preconditioned by heatwaves in the Yangtze River Valley. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099485 (2022).

Iacovone, M. F. Consecutive dry and wet days over South America and their association with ENSO events, in CMIP5 simulations. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 142, 791–804 (2020).

Zhang, W. & Villarini, G. Deadly Compound Heat Stress-Flooding Hazard Across the Central United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089185 (2020).

Spangler, K. R., Liang, S. & Wellenius, G. A. Wet-Bulb globe temperature, universal thermal climate index, and other heat metrics for US Counties, 2000–2020. Sci. Data 9, 326 (2022).

Sauter, C., White, C. J., Fowler, H. J. & Westra, S. Temporally compounding heatwave–heavy rainfall events in Australia. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 1050–1061 (2022).

Min, S. et al. Human Contribution to the 2020 Summer Successive Hot-Wet Extremes in South Korea. Bull. Am. Meterol. Soc. 103, 90–97 (2021).

Dodd, I. C. et al. The importance of soil drying and re-wetting in crop phytohormonal and nutritional responses to deficit irrigation. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2239–2252 (2015).

Linquist, B. A. et al. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and grain arsenic levels in rice systems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 407–417 (2015).

Gao, Y., Hu, T., Wang, Q., Yuan, H. & Yang, J. Effect of drought–Flood abrupt alternation on rice yield and yield components. Crop Sci 59, 280–292 (2019).

FAO & WFP. Special Report: FAO/WFP Crop And Food Security Assessment Mission To Sri Lanka. (FAO, 2017).

Conradie, B., Piesse, J. & Strauss, J. Impact of heat and moisture stress on crop productivity: evidence from the Langgewens Research Farm. S. Afr. J. Sci. 117, 8898 (2021).

Kim, W., Iizumi, T., Hosokawa, N., Tanoue, M. & Hirabayashi, Y. Flood impacts on global crop production: advances and limitations. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 054007 (2023).

Sauter, C. et al. Compound extreme hourly rainfall preconditioned by heatwaves most likely in the mid-latitudes. Weather Clim. Extrem. 40, 100563 (2023).

You, J., Wang, S., Zhang, B., Raymond, C. & Matthews, T. Growing Threats From Swings Between Hot and Wet Extremes in a Warmer World. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104075 (2023).

Sauter, C., Catto, J. L., Fowler, H. J., Westra, S. & White, C. J. Compounding heatwave-extreme rainfall events driven by fronts, high moisture, and atmospheric instability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD038761 (2023).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Tao, H. et al. Integration of extreme gradient boosting feature selection approach with machine learning models: application of weather relative humidity prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 34, 515–533 (2022).

Li, Y., Guan, K., Schnitkey, G. D., DeLucia, E. & Peng, B. Excessive rainfall leads to maize yield loss of a comparable magnitude to extreme drought in the United States. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 2325–2337 (2019).

Kavzoglu, T. & Teke, A. Predictive Performances of Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms in Landslide Susceptibility mapping using random forest, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) and Natural Gradient Boosting (NGBoost). Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47, 7367–7385 (2022).

Jeong, J. H., Resop, J. P., Mueller, N. D. & Fleisher, D. H. Random forests for global and regional crop yield predictions. PLoS One 11, e0156571 (2016).

Bouras, E. et al. Cereal yield forecasting with satellite drought-based indices, weather data and regional climate indices using machine learning in Morocco. Remote Sens. 13, 3101 (2021).

van Klompenburg, T., Kassahun, A. & Catal, C. Crop yield prediction using machine learning: a systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 177, 105709 (2020).

Yuan, S. et al. Southeast Asia must narrow down the yield gap to continue to be a major rice bowl. Nat. Food 3, 217–226 (2022).

Fujimori, S. et al. A multi-model assessment of food security implications of climate change mitigation. Nat. Sustain. 2, 386–396 (2019).

Li, J., Wang, S., Zhu, J., Wang, D. & Zhao, T. Accelerated shifts from heatwaves to heavy rainfall in a changing climate Check for updates. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 214 (2025).

Ben-Ari, T. et al. Causes and implications of the unforeseen 2016 extreme yield loss in the breadbasket of France. Nat. Commun. 9, 1627 (2018).

Zachariah, M. et al. Consecutive extreme heat and flooding events in Argentina highlight the risk of managing increasingly frequent and intense hazards in a warming climate. (Imperial, 2025).

Kaur, G. et al. Impacts and management strategies for crop production in waterlogged or flooded soils: a review. Agron. J. 112, 1475–1501 (2020).

Jackson, M. B. & Ram, P. C. Physiological and molecular basis of susceptibility and tolerance of rice plants to complete submergence. Ann. Bot. 91, 227–241 (2003).

Huang, B., Johnson, J. W., Nesmith, S. & Bridges, D. C. Growth, physiological and anatomical responses of two wheat genotypes to waterlogging and nutrient supply. J. Exp. Bot. 45, 193–202 (1994).

Heino, M. et al. Two-thirds of global cropland area impacted by climate oscillations. Nat. Commun. 9, 1257 (2018).

Mishra, V. et al. Moist heat stress extremes in India enhanced by irrigation. Nat. Geosci. 13, 722–728 (2020).

Haqiqi, I., Grogan, D. S., Hertel, T. W. & Schlenker, W. Quantifying the Impacts of Compound Extremes on Agriculture and Irrigation Water Demand. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 551–564 (2021).

Beillouin, D., Schauberger, B., Bastos, A., Ciais, P. & Makowski, D. Impact of extreme weather conditions on European crop production in 2018: random forest - Yield anomalies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 375, 0510 (2020).

Ahvo, A. et al. Agricultural input shocks affect crop yields more in the high-yielding areas of the world. Nat. Food 4, 1037–1046 (2023).

Hendrawan, V. S. A., Kim, W. & Komori, D. Crop response pattern to several drought timescales and its possible determinants: a global-scale analysis during the last decades. Anthropocene 43, 100389 (2023).

Jones, E. J. et al. Identifying causes of crop yield variability with interpretive machine learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 192, 106632 (2022).

Lesk, C. et al. Stronger temperature–moisture couplings exacerbate the impact of climate warming on global crop yields. Nat. Food 2, 683–691 (2021).

Marcos-Garcia, P., Carmona-Moreno, C. & Pastori, M. Intra-growing season dry-wet spell pattern is a pivotal driver of maize yield variability in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Food 5, 775–786 (2024).

Fritz, S. et al. Mapping global cropland and field size. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 1980–1992 (2015).

Monfreda, C., Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Farming the planet: 2. Geographic distribution of crop areas, yields, physiological types, and net primary production in the year 2000. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22, GB1022 (2008).

Sacks, W. J., Deryng, D., Foley, J. A. & Ramankutty, N. Crop planting dates: An analysis of global patterns. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 19, 607–620 (2010).

Lesk, C. & Anderson, W. Decadal variability modulates trends in concurrent heat and drought over global croplands. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 0550245 (2021).

Chevuru, S., de Wit, A., Supit, I. & Hutjes, R. Copernicus global crop productivity indicators: An evaluation based on regionally reported yields. Clim. Serv. 30, 100374 (2023).

Chen, H. & Wang, S. Compound Dry and Wet Extremes Lead to an Increased Risk of Rice Yield Loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105817 (2023).

Song, X. P. et al. Massive soybean expansion in South America since 2000 and implications for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 4, 784–792 (2021).

Iizumi, T. & Sakai, T. The global dataset of historical yields for major crops 1981–2016. Sci. Data 7, 97 (2020).

Hendrawan, V. S. A. et al. A global-scale relationship between crop yield anomaly and multiscalar drought index based on multiple precipitation data. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 014037 (2022).

Grogan, D., Frolking, S., Wisser, D., Prusevich, A. & Glidden, S. Global gridded crop harvested area, production, yield, and monthly physical area data circa 2015. Sci. Data 9, 15 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Land – atmosphere feedbacks contribute to crop failure in global rainfed breadbaskets. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 51 (2023).

Zhang, X., Hegerl, G., Zwiers, F. W. & Kenyon, J. Avoiding inhomogeneity in percentile-based indices of temperature extremes. J. Clim. 18, 1641–1651 (2005).

Zhang, X., Vincent, L. A., Hogg, W. D. & Niitsoo, A. Temperature and precipitation trends in Canada during the 20th century. Atmos. - Ocean 38, 395–429 (2000).

Wang, X. L. & Swail, V. R. Changes of extreme wave heights in northern hemisphere oceans and related atmospheric circulation regimes. J. Clim. 14, 2204–2221 (2001).

Qian, C., Zhang, X. & Li, Z. Linear trends in temperature extremes in China, with an emphasis on non-Gaussian and serially dependent characteristics. Clim. Dyn. 53, 533–550 (2019).

Cleveland, W. S. & Devlin, S. J. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 596–610 (1988).

Iturbide, M. et al. An update of IPCC climate reference regions for subcontinental analysis of climate model data: definition and aggregated datasets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2959–2970 (2020).

Baranwal, A., Bagwe, B. R. & M, V. Scikit-learn: machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res.12, 128–154 (2019).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. 785–794 (2016) https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785.

Chen, F., Feng, P., Harrison, M. T. & Wang, B. Cropland carbon stocks driven by soil characteristics, rainfall and elevation. Sci. Total Environ. 862, 160602 (2022).

Elavarasan, D. & Vincent, P. M. D. R. A reinforced random forest model for enhanced crop yield prediction by integrating agrarian parameters. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 12, 10009–10022 (2021).

Gibson, P. B. et al. Training machine learning models on climate model output yields skillful interpretable seasonal precipitation forecasts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 159 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant No. 2023YFF0805504), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42175175), and the Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Climate Change. We acknowledge the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (SAGE), UW-Madison, and DIAS Operator for producing and making available crop calendars and yield datasets, respectively. In addition to that, the authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. designed, conducted the study and wrote the initial draft. C.Q. supervised the study, reviewed, edited the paper and acquired funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Thong Nguyen-Huy and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Gilbert Siame and Mengjie Wang. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabtih, A.K., Qian, C. Risk of successive hot-pluvial extremes on crop yield loss over global breadbasket regions. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1040 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02989-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02989-5