Abstract

Microbial communities are central to the functioning and resilience of biological water treatment systems, yet their structural and functional determinants remain poorly understood. Here, an interpretable machine-learned framework is developed to decode ecological drivers of treatment performance across 648 globally distributed biofilters. Keystone taxa, such as Nitrospira, Hyphomicrobium, Flavobacterium, are identified via deep ecological modeling. Models that include microbial ecological indicators, particularly the presence ratios of structural and functional keystone taxa, improve pollutant removal prediction (R² = 0.742) by 36.9% compared with models based only on process parameters. Generalized additive models with structured interactions further reveal volume, temperature, media size, and hydraulic retention time as ecological levers shaping microbial structure and function. Lab-scale biofilter experiments demonstrate consistent microbial shifts and improved treatment performance aligned with model predictions. These findings enable targeted microbiome control in biofilters and provide a foundation for adaptive operation of biological water systems under environmental variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global water systems face escalating challenges of resource scarcity, climate variability, and emerging contaminants, the demand for energy-efficient and ecologically robust treatment technologies has intensified1,2. Biofiltration systems, including rapid sand filters, granular activated carbon filters, and denitrification filters, have gained prominence across drinking water, stormwater, and wastewater treatment due to their low energy requirements and intrinsic microbial self-regulation3. However, their performance often suffers from instability, which is largely attributable to complex and poorly understood microbially mediated processes4.

Microbial communities underpin the core functions of biological water treatment systems, especially in biological filtration processes where microbial assemblages mediate contaminant transformation, redox cycling, and resilience to environmental perturbations across diverse water types5,6. High-throughput sequencing and functional annotation pipelines, such as 16S rRNA gene inference, metagenomics, have enabled comprehensive profiling of microbial consortia in bioreactors. However, most studies still rely on bulk-level descriptors that lack mechanistic depth7. Therefore, despite decades of operational optimization, the ability to harness and control microbial community dynamics for reliable and resilient treatment performance remains limited8. A central challenge lies in the dynamic nature of microbial composition, the nonlinear relationships between structure and function, and the difficulty of generalizing ecological responses to environmental shifts across systems9. Previous microbiome modeling efforts have sought to link community profiles with treatment performance, but most rely on correlation analyses, co-occurrence networks, and black-box machine learning10,11. These approaches often achieve limited transferability across operating conditions, and their opaque feature attributions hinder practical application12. There remains a critical need for approaches that couple predictive capacity with mechanistic transparency, enabling ecological insights to be translated into actionable levers for process stability13,14.

Recent advances in ecological theory and computational modeling suggest that microbial ecosystems may be governed by a small set of keystone taxa that disproportionately influence community stability and functionality, even when present at moderate or low abundance15. These keystone members may serve as sentinels or even control nodes for bioprocess performance, particularly under stress or transitional regimes16. Nevertheless, a central knowledge gap remains in translating ecological insights into actionable engineering strategies, specifically whether and how keystone taxa configurations can be predictably tuned through controllable levers to ensure stable and efficient treatment outcomes17.

The rise of interpretable machine learning offers valuable opportunities to resolve these ecological complexities. Unlike black-box predictors, models such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) enabled ensembles, generalized additive models with interactions (GAMI), and neural additive models can attribute output variation to specific input features in ways that are both statistically transparent and biologically interpretable18,19,20. Integrating these approaches into microbial ecology could enable data-driven frameworks that explain and control bioprocess performance across heterogeneous treatment environments.

In this study, we address these gaps by developing an interpretable, machine learning-based ecological framework that systematically decodes the relationships between microbial composition, ecological function, and pollutant removal across a global collection of biofilters (Fig. 1). We (i) identify structural and functional driver taxa using deep learning-based keystone inference; (ii) establish ecological indicators that reliably predict treatment outcomes based solely on microbial community properties; and (iii) apply a transparent and modular machine learning architecture to disentangle how environmental and operational parameters act as ecological levers that shape these key microbial features. Finally, we validate model-predicted ecological pathways with lab-scale biofilter experiments, providing proof-of-concept that microbiome-responsive engineering can move from abstraction to actionable control.

a Microbial and operational data were compiled from 648 biofilters treating various influent types. b Structural and functional keystone taxa were identified using deep learning-based modeling approaches. c Microbial indicators were used as inputs to train and interpret machine learning models for predicting pollutant removal rates. d Interpretable modeling revealed key environmental and operational levers (e.g., temperature, HRT, filter media) influencing keystone taxa expression, which were further validated through lab-scale biofilter experiments.

Results

Microbial diversity and metabolic function profiles in global biofilters

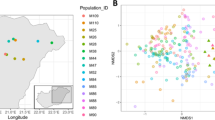

Biofiltration host diverse and dynamic microbial communities that play central roles in pollutant transformation, nutrient cycling, and system resilience21. To comprehensively elucidate the global patterns of bacterial communities in biofiltration processes, accessible and high-quality 16S rRNA gene sequencing data were extracted from 1165 relevant research articles published between 1988 and 2024 on the Web of Science Core Collection database. A dataset comprising 648 biofilter samples was constructed, encompassing a broad range of geographical locations (across 3 continents, 10 countries, and 40 cities), water types (drinking water, groundwater, stormwater, and wastewater), and operational conditions (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1). A comparative analysis of microbial communities in biofilters worldwide in terms of species richness, diversity, and evenness reveals a generally high degree of geographic heterogeneity, yet several discernible patterns can still be identified (Supplementary Fig. 1). For instance, microbial communities in North America typically exhibit lower species richness and evenness compared to those in Europe and Asia, but display higher overall diversity (Fig. 2b–d). This pattern may reflect region-specific selective pressures. North American drinking water systems often employ more intensive disinfection practices and exhibit lower natural organic matter loads, which constrain species richness but allow niche partitioning among a smaller set of functionally diverse taxa22,23. Microbial communities in Asian biofilters show more dispersed distributions across richness, diversity, and evenness, indicating pronounced regional variability, as exemplified by the community structures observed in cities such as Chengdu and Guangzhou, China. It is likely driven by heterogeneous source waters, broader climatic gradients, and varied operational strategies, which together contribute to the observed variability in community structure5.

a Geographic distribution of biofilter samples for drinking water (green), groundwater (purple), stormwater (yellow), wastewater (pink) treatment. A total of 648 biofilter samples were collected from 1165 published articles that included environmental and operational parameters. Raw 16S rRNA gene sequencing data were strictly screened from National Center for Biotechnology Information. Community richness (observed species) (b), diversity (Shannon’s index) (c), and evenness (Simpson’s index) (d) across biofilters from different continents. The horizontal line within each box indicates the median; the box indicates the first (lower) and third (upper) quartiles; and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values aside from potential outliers. Differences of community richness (observed species) (e), diversity (Shannon’s index) (f), and evenness (Simpson’s index) (g) of communities among drinking water, groundwater, stormwater, and wastewater biofilters (determined by Wilcoxon test). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. DW drinking water, GW groundwater, SW stormwater, WW wastewater. h Venn diagram illustrating the specific or shared metabolic functions among the four biofilter types. i Top 10 differential microbial metabolic pathways among the four biofilter types (determined by Kruskal–Wallis test). Bar plots show the relative proportion of KEGG level-3 metabolic pathways.

The wastewater biofilter and drinking water biofilter did not exhibit significant differences in community structure (Wilcoxon test) (Fig. 2e–g). However, the species richness (2082 ± 854) and community diversity (6.55 ± 0.77) of the stormwater biofilter were significantly higher than those of other filter types (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.001). These differences likely arise from the episodic and heterogeneous characteristics of stormwater inputs, which introduce diverse microbial communities and substrates, thereby promoting higher community diversity24. Based on Spearman correlation analysis, the relationship between external factors and genus-level microbial abundance indicates that, in addition to water quality factors, environmental conditions (e.g. temperature) and operational parameters (filter media, flow rate, etc.) jointly shape community composition (Supplementary Figs. 2–3). In parallel, PICRUSt2 functional gene predictions based on 16S rRNA uncovered system-specific enrichment of key metabolic pathways, with over 83% of the metabolic pathways present in all four filter types, including ABC transporters, nitrogen metabolism, and TCA cycle (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Table 2). Significant differences in microbial metabolic pathways (such as synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies, and fatty acid biosynthesis) were observed among drinking water, groundwater, stormwater, and wastewater filters (Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2i, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3). These differences resulted in varying activity of microbial metabolic pathways across different water types25,26. Notably, while community composition varied substantially across systems, several functional modules, particularly those associated with nitrogen and carbon metabolism, were recurrently maintained, indicating a degree of functional redundancy (Supplementary Fig. 5). Such redundancy ensures the stability of biofiltration processes against environmental perturbations and stochastic community shifts, and underpins the robustness of pollutant removal and nutrient cycling27. Collectively, these results present a global dataset of microbial diversity and metabolic capacity in biofiltration ecosystems, setting the stage for mechanistic exploration of structure and function linkages and controllable drivers.

Identifying microbial keystone taxa in biofilter by deep learning model

To disentangle microbial determinants underlying community assembly and ecosystem robustness in global biofilters, a deep learning approach based on Neural Ordinary Differential Equations, enhanced with automated hyperparameter tuning via Optuna and L1 regularization, was employed to identify keystone taxa28 (Fig. 1b). Each microbiome sample is encoded by a binary genus assemblage vector z ∈ {0,1}ⁿ, indicating the presence or absence of each genus, and an associated abundance profile p ∈ Δⁿ, representing relative genus-level composition. The Neural Ordinary Differential Equations model learns a continuous mapping φ: z → p, such that φ(z) approximates the observed abundance given the taxonomic assemblage, thereby enabling simulation of community responses to perturbations. To evaluate the ecological importance of each genus, in silico genus removal was performed by modifying z to z̃ = z \ i, predicting the resulting composition φ(z̃), and comparing it with a null composition p̄ that assumes no ecological effect. The structural keystoneness score (Ks) of genus i was then defined as the dissimilarity between φ(z̃) and p̄, scaled by a biomass adjustment factor (1−pᵢ), capturing both impact and disproportionality. The approach was validated using synthetic data generated from a generalized Lotka–Volterra (GLV) model with 100 genera, showing strong agreement between predicted and true Ks values (Spearman ρ = 0.98, p < 0.001), thereby demonstrating high accuracy in capturing ecological relevance under controlled conditions (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, by incorporating a functional gene network, the approach was extended to compute the functional keystoneness score (Kf), which quantifies the impact of genus removal on the predicted functional profile of the community (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Ks for each genus detected in the samples was calculated, and genera present in at least 25% of the samples were ranked based on their median Ks values (Supplementary Fig. 8). Genera with higher median Ks, such as Gemmobacter, exhibited greater inter-sample variability in Ks, indicating stronger community specificity in their structural roles (Fig. 3a). In contrast, genera with lower median Ks, such as Clostridium sensu stricto 13, displayed lower variability, suggesting more consistent structural contributions across communities (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, median Ks and median absolute deviation of Ks (MAD Ks) were highly correlated (Spearman’s ρ = 0.97, p < 0.001), implying that genera with low median Ks are unlikely to be structural keystone taxa in any community, whereas those with high median Ks may serve as keystone taxa in some communities but not others (Fig. 3e). Similarly, Kf showed a strong positive correlation between its median value and MAD Kf (Spearman’s ρ = 0.97, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3f). Genera with high median Kf, such as Nitrospira, showed substantial inter-sample variability, indicative of stronger community specificity in their functional roles (Fig. 3c). Conversely, genera with low median Kf, such as the Burkholderia-complex, exhibited limited variation, suggesting more consistent functional keystoneness across communities (Fig. 3d). The relative abundance analysis reveals that most keystone taxa exhibit low abundance, which is consistent with the theoretical definition of keystone taxa as rare but critical members within microbial communities16,29 (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Distributions of structural keystoneness scores (Ks) for the top 20 (a) and bottom 20 (b) genera, ranked by median Ks across all samples. Only genera present in at least 25% of the samples and ranked among the top 300 in relative abundance are shown. Distributions of functional contribution scores (Kf) for the top 20 (c) and bottom 20 (d) genera, ranked by median Kf across all samples. e Spearman correlation between median Ks and median absolute deviation (MAD) of Ks across samples for structural keystone taxa. f Spearman correlation between median Kf and MAD Kf across samples for functional keystone taxa. Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) and corresponding p-values are shown. Violin plots show the distribution of the data, with the width representing the density of observations.

Among the top 20 genera ranked by Ks and Kf, several taxa were shared, including Nitrospira, Hyphomicrobium, Flavobacterium, Bradyrhizobium, and Reyranella, highlighting their dual importance in sustaining both community architecture and ecosystem function. Nitrospira has been widely recognized as a dominant nitrite oxidizer in diverse water treatment systems, and its high Ks and Kf values here suggest not only its essential role in nitrification but also its network centrality5,30. Hyphomicrobium is often reported in denitrifying biofilms and MBRs due to its ability to utilize methanol and other C1 compounds, linking it to carbon–nitrogen coupling31,32. Flavobacterium is frequently associated with organic matter degradation and biofilm formation, thereby influencing both nutrient turnover and microbial interactions33,34. The fact that these taxa exhibit high Ks and Kf presence ratios indicates that keystone indicators capture both ecological indispensability in community structure and functional significance in metabolic potential, which together underpin their reliability as critical markers of system performance. Interestingly, certain genera, such as Pseudomonas and Sphingomonas ranked highly in Ks but not in Kf. This suggests that they may play a central role in community structure, possibly through biofilm formation or interspecies interactions, without directly driving key biogeochemical functions35. Massilia and Mycobacterium were identified among the top Kf but not within Ks, reflecting specialized metabolic capacities (e.g., pollutant degradation or stress tolerance) that enhance biofilter function without making them central to community structure. Generally, a genus exhibits a lower Kf than Ks, likely reflecting functional redundancy, where phylogenetically distinct genera possess similar genes and fulfill comparable functions. This redundancy is believed to contribute to the stability and resilience of microbial communities36.

Predicting biofilter performance from microbial ecological indicators

The divergence between structural and functional keystone taxa reflects ecological redundancy that enhances microbiome stability under disturbance, while also presenting an engineering opportunity: the potential to translate keystone-derived signals into quantitative predictors of treatment performance. This requires a framework that integrates keystone metrics with community-level traits to forecast pollutant removal under variable conditions. Accordingly, machine learning was applied to integrated microbial ecological indicators to predict biofilter performance and pinpoint the features most strongly associated with removal efficiency. Three feature categories were considered: (A) keystone-based indicators, (B) structural community metrics, and (C) functional gene profiles. These were combined into four input groups (ABC, AB, AC, BC) and evaluated using 15 machine learning algorithms, encompassing tree ensembles, kernel regressors, linear models, and non-parametric or neural network methods37 (Supplementary Table 4). Model hyperparameters were tuned to optimize their performance, and the corresponding ranges of hyperparameters are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

To mitigate the impact of multicollinearity, redundant features with an absolute Pearson correlation coefficient |r| > 0.85 were removed, ensuring the reliability and interpretability of the model’s predictions (Supplementary Fig. 10). Among all feature combinations, the ABC feature group that integrates keystone taxa indicators with structural and functional descriptors showed generally higher prediction performance (Fig. 4a). In particular, the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) model trained on this complete set achieved the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.742), along with the lowest observed errors (MAE = 13.25, MAPE = 0.133, MSE = 415, and RMSE = 20.37), outperforming other top-performing models including support vector regression (SVR), extra trees (ET), and CatBoost (R2 ranging from 0.625 to 0.669). These results underscore the model’s superior ability to capture nonlinear mappings between microbial features and process performance (Fig. 4b). In contrast, linear models such as Lasso exhibited markedly poorer performance, with R2 values below 0.1. Importantly, compared to the model based solely on process parameters, the microbiome-informed KNN model reduced average prediction errors by over 25.0% and improved R2 by 36.9%, demonstrating the substantial value of incorporating microbial indicators into predictive frameworks for biofilter system performance (Supplementary Table 6).

a Comparative model performance of 15 machine learning algorithms across 4 microbial feature groups (AB, AC, BC, ABC), evaluated using mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean squared error (MSE), root mean squared error (RMSE), and R-squared (R2). Color intensity represents the magnitude of each evaluation indicators. b Performance of machine learning algorithms using ABC input for predicting pollutant removal rates. Blue points represent training samples, and orange points represent test samples. RF random forest, ET extra trees, LightGBM light gradient boosting machine, AdaBoost adaptive boosting, XGBoost extreme gradient boosting, CatBoost categorical boosting, GBR gradient boosting regression, SVR support vector regression, Lasso least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, Bay bayesian ridge, ARD automatic relevance determination, KNN K-nearest neighbor, ELM extreme learning machine, KAN kolmogorov-arnold network, DT decision trees.

The internal logic of the best-performing KNN model was examined using SHAP to identify important microbial predictors of pollutant removal. Remarkably, the presence ratios of Ks and Kf, representing structural and functional keystone taxa respectively, ranked as the most influential positive predictors of pollutant removal, highlighting the critical role these keystone taxa play in driving treatment efficacy (Supplementary Fig. 11). The presence of keystone taxa, even at low abundance, provided greater predictive power than traditional diversity indices or functional genes abundances. This observation aligns with emerging ecology theory, which emphasize the disproportionate regulatory influence of low-abundance taxa in preserving system resilience and functional redundancy38,39. Crucially, the model was constructed without environmental or operational parameters, thereby isolating microbial indicators as the sole input. This design minimizes potential confounding from exogenous drivers and reinforces the intrinsic predictive value of microbiome-informed variables40.

Inferring tunable ecological levers of microbial structure and function

Following the identification of Ks and Kf presence ratios as reliable microbial indicators of pollutant removal, their responsiveness to controllable operational and environmental factors was evaluated. This enables translation of microbiome-based diagnostics into design-relevant control strategies. An explainable neural network based on generalized additive models with structured interactions (GAMI-Net) was trained on a global biofilter dataset to model the effects of 11 tunable variables, including water type, target pollutant, pH, temperature, hydraulic retention time (HRT), flow rate, working volume, media type, filter media size, nutritional condition, and oxygen condition. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 12a, b and 13a, b, the GAMI-Net model undergoes three training stages: main effect learning, pairwise interaction modeling, and fine-tuning with sparsity constraints. Transitions between stages are marked by shifts in training and validation loss curves, with the incorporation of pairwise interactions leading to notable performance gains. Supplementary Figs. 12c, d and 13c, d illustrate how GAMI-Net adaptively selects significant main and pairwise effects through structured pruning during training, balancing model complexity and interpretability while mitigating overfitting.

The model demonstrated strong explanatory power, with R2 of 0.854 for Ks presence ratio and 0.845 for Kf presence ratio, and corresponding MAEs of 0.083 and 0.077, respectively. The Ks presence ratio was primarily modulated by working volume (IR = 32.8%), temperature (27.5%), filter media size (10.5%), and HRT (6.3%) (Supplementary Fig. 14). Systems with reduced working volumes and shorter HRTs exhibited elevated Ks presence ratios, suggesting that more compact and hydraulically dynamic environments promote the dominance or resilience of structurally influential taxa (Fig. 5). These conditions likely create steeper substrate gradients and stronger biofilm selection pressures, favoring keystone taxa such as Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, Nitrospira, and Hyphomicrobium, known for their biofilm formation, metabolic versatility5,41,42. Filter media with particle sizes <10 mm increased surface area and enhanced microbial attachment, fostering tighter community networks and more stable structural cores, consistent with established knowledge of filter media performance43,44. By contrast, larger media limit attachment density and weaken network cohesion. Interestingly, Ks presence ratio exhibited a non-monotonic response to temperature, with local maxima observed at 12 °C and 25 °C, possibly reflecting context-specific microbial interactions or niche shifts along the thermal gradient45. This behavior may result from shifts in microbial interaction structure, with intermediate temperatures favoring transitions from competition to facilitation that enhance metabolic or functional diversity46. Theory also indicates that variation in the temperature dependence of growth rates and interaction strengths can generate richness–temperature curves, with peaks at specific points along the gradient47. In addition, latent functional diversity and species sorting processes may enable communities to achieve distinct functional optima at different temperatures48. However, these interpretations remain tentative, and multiple mechanisms could contribute to the observed pattern. Similarly, the Kf presence ratio was governed by the same environmental drivers, with temperature (38.9%) exerting the strongest influence, followed by working volume (29.9%), filter media size (9.4%), and HRT (5.9%) (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 15). Importantly, filter media size, expressed as particle diameter, and filter media type, defined by material composition, are complementary attributes of biofilm carriers. Size influences available surface area and mass transfer, whereas type shapes physicochemical interactions and microbial colonization. Among different filter media types, carbon-based materials (CarBM) had the strongest positive impact on microbial structure and function, followed by synthetic polymeric materials (SynPM), modified composite materials (ModCM), and mineral substrate materials (MinSM), with ceramic-based materials (CerBM) performing the worst. These ecological levers regulate microbial structure and function by shaping substrate availability, attachment niches, and interaction dynamics.

GAMI-Net model identifies the significant main effects and pairwise interactions in predicting the Ks presence ratio. The one-dimensional plots illustrate the marginal effects of individual features, while the two-dimensional plots depict pairwise feature interactions. In the one-dimensional plots, the horizontal axis represents the values of the feature, and the vertical axis indicates its corresponding contribution to the prediction. In the two-dimensional plots, the horizontal and vertical axes represent the values of the two interacting features, respectively. Lighter colors indicate stronger interaction effects on the prediction. Subplot titles indicate the feature names and their importance ratios (IR). Histograms alongside each axis show the data distribution of the corresponding feature. CarBM carbon-based materials, CerBM ceramic-based materials, MinSM mineral substrate materials, ModCM modified composite materials, SynPM synthetic polymeric materials.

GAMI-Net model identifies the significant main effects and pairwise interactions in predicting the Kf presence ratio. The one-dimensional plots illustrate the marginal effects of individual features, while the two-dimensional plots depict pairwise feature interactions. In the one-dimensional plots, the horizontal axis represents the values of the feature, and the vertical axis indicates its corresponding contribution to the prediction. In the two-dimensional plots, the horizontal and vertical axes represent the values of the two interacting features, respectively. Lighter colors indicate stronger interaction effects on the prediction. Subplot titles indicate the feature names and their IR. Histograms alongside each axis show the data distribution of the corresponding feature. CarBM carbon-based materials, CerBM ceramic-based materials, MinSM mineral substrate materials, ModCM modified composite materials, SynPM synthetic polymeric materials, HET heterotrophic, AUT autotrophic, HET/AUT heterotrophic/autotrophic.

Additionally, the model revealed nonlinear threshold effects and synergistic interactions. For instance, influent pollutant concentrations exceeding 200 mg L−1 clearly increased Ks presence ratio, but only under anaerobic conditions. This suggests a substrate-induced activation of fermentative pathways, likely triggered when carbon availability exceeds a functional threshold under redox-constrained conditions49. In contrast, the Kf presence ratio exhibited a more bimodal ecological response, increasing under both substrate-limiting (<50 mg L−1 or HRT < 4 h) and substrate-excess conditions (>600 mg L−1 or HRT > 8 h). Stress-resilient oligotrophs such as Hyphomicrobium dominate under substrate limitation through high-affinity uptake and slow-growth survival strategies50,51. Under substrate-excess conditions, copiotrophic or EPS-producing taxa like Massilia, Romboutsia, and Flavobacterium proliferate, leveraging resource surplus and extended retention for biofilm maturation52. Recognizing these tipping points can help optimize biofilter operation to promote beneficial microbial configurations.

Experimental validation of model-predicted ecological mechanisms

To verify the predictive capacity and ecological plausibility of the interpretable keystone modeling framework, a controlled lab-scale validation experiment was conducted using four parallel biofilter systems (H1–H4). These systems were designed to emulate distinct combinations of operational levers identified as key regulators of microbial keystoneness indicators, including temperature, HRT, and filter media characteristics. As inferred by GAMI-Net, temperature and HRT were highly influential variables modulating Ks and Kf presence ratios, showing nonlinear threshold effects and ecological tipping points, while media type governed surface microhabitat availability and shaped microbial structure and function. Therefore, these levers were selected as representative test conditions to validate the model’s predictions in controlled experiments.

In H1 and H2, the effect of temperature and HRT was systematically examined by operating H1 at 25 °C and H2 at 15 °C, with both units subjected to short (2 h) and long (8 h) HRT (Fig. 7a). Consistent with model predictions, the Ks and Kf presence ratios were higher in the warmer (25 °C) and shorter HRT (2 h) conditions, with corresponding increases in biofilter performance (Fig. 7b–d). Conversely, an HRT of 8 h under low temperature (15 °C) led to sharp reductions in both keystoneness indices and treatment performance, empirically supporting the predicted ecological tipping points.

a Schematic diagram of experimental setup for H1 and H2 reactors operated under different temperature and HRT conditions. b Ks presence ratio under varying temperature and HRT in H1 (25 °C, HRT = 2 h or 8 h) and H2 (15°C, HRT = 2 h or 8 h). c, Kf presence ratio under the same conditions in H1 and H2. d Pollutant removal efficiency in H1 and H2. e Schematic diagram of experimental setup for H3 and H4 reactors operated with different filter media (CerBM and SynPM). f Ks presence ratio under different filter media in H3 (ceramic-based media, CerBM) and H4 (synthetic polymeric media, SynPM). g Kf presence ratio under different filter media in H3 and H4. h Pollutant removal efficiency in H3 and H4. Error bars represent standard deviation of three replicates.

In H3 and H4, the impact of filter media type was evaluated by packing with CerBM (H3) or SynPM (H4) (Fig. 7e). H4 demonstrated higher Ks and Kf presence ratios and superior biofilter performance, confirming that surface microhabitat properties act as a lever for functional potential realization (Fig. 7f–h). Across all units, microbial community profiling, gene functional inference, and pollutant removal performance confirmed that observed shifts in keystoneness metrics were tightly coupled to changes in environmental parameters, as anticipated by the ecological response models.

Discussion

This study establishes a comprehensive global dataset of biofilter systems reported since 1988 and introduces an interpretable, microbially grounded modeling framework that integrates microbial community structure, ecological function, and water treatment performance. Specifically, sequencing and operational metadata were compiled from 1165 publications, and 648 biofilter samples were rigorously curated, covering diverse regions, water types, and operational conditions. This broad coverage enhances the robustness of model training and inference. By identifying structural keystone taxa and functional contributor taxa, the framework provides mechanistic insight into how microbial indicators reflect and respond to environmental and operational conditions. The integration of deep learning, ecological theory, and interpretable machine learning approaches (e.g., GAMI-Net, SHAP) facilitates mechanistic understanding and transparent inference across microbial, process, and system scales.

A key contribution of this study is the identification of specific operational variables as tunable ecological levers for two keystoneness indicators, the presence ratios of structural and functional taxa. These variables, including temperature, working volume, HRT, and filter media, exert distinct effects on microbial structural cohesion and metabolic capacity within biofilter communities. Experimental validation confirms that adjusting these parameters can steer microbial community states toward ecologically favorable regimes, thereby enhancing pollutant removal performance. The Ks presence ratio was found to be particularly sensitive to changes in working volume, while the Kf presence ratio showed a stronger association with temperature. This ecological differentiation provides a foundation for targeted control of microbial ecosystems within biofilters and is essential for balancing community stability and functional efficiency, which are often in trade-off in complex microbial systems.

Despite its mechanistic insights and predictive power, this study has limitations that warrant consideration. The current analysis is based primarily on cross-sectional data, which constrains the ability to capture temporal dynamics such as resilience and succession under perturbations. Metadata quality and reporting heterogeneity across studies introduce uncertainty into model calibration. These limitations suggest that while the framework is robust across a large study dataset, its generalizability to full-scale, long-term operations requires further validation. In addition, although key microbial indicators were identified, causal mechanisms at finer taxonomic and functional resolutions remain to be elucidated, particularly under fluctuating environmental conditions. Future work may extend this framework to full-scale, dynamic operations and continuous monitoring, and incorporate longitudinal datasets to capture resilience under perturbation. Coupling the framework with adaptive control strategies could enable real-time regulation of microbiomes, where community states are not only observed but actively guided toward optimized ecosystem function.

Methods

Data collection of global biofilters

A comprehensive dataset of global biofilter processes has been compiled. Biofilter-related studies were retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection database using the keywords “water”, “biofilter”, and “microbial community”. The advanced search strategy was: TS = (water OR *water) AND TS = (biofiltration OR biological filtration OR biofilter OR bio-filter OR biological filter) AND TS = (microbial community) AND DT = (Article), yielding 1165 publications from 1988 to 2024. Raw 16S rRNA gene sequencing data for 648 biofilter samples were rigorously screened and obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. SRA accession numbers and associated metadata for the retrieved sequencing data are provided in Supplementary Table 1. For each sample, metadata on geographic locations (spanning Asia, Europe, North America), water types (e.g., drinking water, groundwater, stormwater, wastewater), water quality (e.g., pH, targeted pollutant concentration), operational parameters (e.g., temperature, HRT, filter media characteristics, oxygen and nutrient conditions), and contaminant removal efficiencies were extracted and curated (Fig. 1a).

16S rRNA gene sequencing data processing

Raw sequencing reads were retrieved using SRA Toolkit (v2.10.8)53. All 16S rRNA gene sequences were processed and analyzed using USEARCH (v10.0.240)54. Reads with low quality, PCR duplicates, and adapter contamination were removed. After standardized quality control, operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering was performed at a 97% sequence similarity threshold55. Taxonomic classification of representative OTU sequences was performed using the SINTAX classifier against the SILVA database, with a confidence threshold of 0.856. Each sample was processed and analyzed individually, and the resulting taxonomic assignments at the genus level were then merged for statistical analysis and visualization. Microbial community composition was determined via 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and functional profiles were predicted based on KEGG pathway inference using PICRUSt256.

Identification of structural and functional keystone taxa

A deep learning framework for keystone taxon identification was developed based on the approach of Wang, et al.28, using a Neural Ordinary Differential Equations model to learn the complex mapping φ: z → p that captures microbial co-occurrence patterns (Fig. 1b). It was trained on the top 300 genera across 648 biofilter samples, with 20% held out for validation, and parameters from the best-performing epoch were retained. The trained model was used to conduct in silico perturbation experiments. For each microbiome sample s = (z, p), the removal of individual genus i was simulated by transforming z to z \ i.

The Ks for genus i in community s was calculated as:

where d(p̃, p̄) represents the structural impact quantified by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, and (1 - pi) accounts for biomass component.

Similarly, the Kf was calculated as:

where d(f̃, f̄) represents the functional impact based on dissimilarity in predicted functional profiles. Functional profiles were predicted using PICRUSt2 based on 16S rRNA gene data. The KEGG Ortholog (KO) content of each genus was computed by averaging the KO profiles of all OTUs assigned to that genus. The top 20 taxa ranked by Ks and Kf, respectively, were retained as structural and functional keystone taxa.

Predictive modeling of pollutant removal efficiency

Multiple regression models were constructed to predict pollutant removal efficiency based on microbially derived indicators (Fig. 1c). Three types of feature sets were evaluated in various combinations:

-

(A)

Keystone-based indicators: Ks20 median, Kf20 median, Ks weighted sum, Kf weighted sum, Ks presence ratio, Kf presence ratio, functional efficiency ratio (median Kf/median Ks), and keystone functionality product (median Kf × median Ks);

-

(B)

Structural community metrics: Shannon’ index, Simpson’ index, and richness;

-

(C)

Functional gene profiles: Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, carbon fixation pathways in prokaryotes, TCA cycle, nitrogen metabolism, phosphonate and phosphinate metabolism, sulfur metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, two-component system, and ABC transporters.

Models were constructed using four different combinations of these input features: ABC, AB, AC, and BC. All datasets were normalized using Z-score standardization to reduce the influence of outliers and scale differences. The dataset was randomly split into 90% for training and 10% for testing. A total of 15 machine learning algorithms were evaluated, and the description and advantages of these algorithms are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. All models were trained using rigorous data cleaning, feature engineering, 5-fold cross-validation, and grid search for hyperparameter tuning57 (Supplementary Table 5). Model performance was evaluated on the test set using five metrics: R2, MAE, MAPE, MSE, and RMSE58. The best-performing model was interpreted using SHAP to identify the most influential microbiome-derived features59.

The evaluation metrics were calculated as follows:

Ecological responsiveness modeling via interpretable GAMI-Net model

To quantify the influence of environmental and operational variables on microbial keystone indicators (i.e., Ks presence ratio and Kf presence ratio), an explainable neural network based on GAMI-Net was employed. This model balances predictive accuracy with interpretability and uses major water quality, environmental, media, nutrient, and oxygen variables as inputs (Fig. 1d). Specifically, categorical variables (e.g., water type, filter media, nutritional condition, oxygen condition) were label-encoded before modeling, while all continuous variables and the target variable were normalized. The dataset was randomly split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets, with an internal validation set (20% of the training data) automatically assigned during GAMI-Net training. Early stopping was employed to prevent overfitting.

The mathematical formulation of the model is given by:

where μ is the intercept, X denotes the input features, Y is the response variable, and S₁ and S₂ represent the sets of main effects and pairwise interactions, respectively.

The IR for each main effect was calculated as:

Similarly, the IR for each pairwise interactions was calculated as:

Experimental validation

Four lab-scale biofilters (H1–H4) were constructed to validate model-predicted ecological levers. All reactors were inoculated with the same microbial community and fed with synthetic influent. Temperature (25 °C vs 15 °C) and HRT (2 h vs 8 h) were varied in H1 and H2, while filter media types (CerBM vs SynPM) were tested in H3 and H4. Over a 30-day period, samples were collected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing and pollutant removal analysis. Detailed procedures for reactor setup, sample collection, and sequencing are provided in Supplementary Notes 1 and 2. Experimental changes in Ks indices, Kf indices, and pollutant removal rates were compared with model-predicted values.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All sample information is provided in the Supplementary Information. All data can be accessed at https://github.com/Jinlili-jennie/Identifying_Ecological_Levers.

Code availability

All code used in this study is available at https://github.com/Jinlili-jennie/Identifying_Ecological_Levers/tree/main/Code.

References

Liu, W. et al. Global overlooked multidimensional water scarcity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2413541122 (2025).

Garrido-Baserba, M. et al. Using water and wastewater decentralization to enhance the resilience and sustainability of cities. Nat. Water 2, 953–974 (2024).

Jin, L., Sun, X., Ren, H. & Huang, H. Biological filtration for wastewater treatment in the 21st century: a data-driven analysis of hotspots, challenges and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 855, 158951 (2023).

Shi, X. et al. Microbial stratification and DOM removal in drinking water biofilters: implications for enhanced performance. Water Res. 262, 122053 (2024).

Wu, L. et al. Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1183–1195 (2019).

Ju, F. & Zhang, T. Bacterial assembly and temporal dynamics in activated sludge of a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. ISME J. 9, 683–695 (2015).

Regueira-Iglesias, A., Balsa-Castro, C., Blanco-Pintos, T. & Tomas, I. Critical review of 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow in microbiome studies: from primer selection to advanced data analysis. Mol. Oral. Microbiol. 38, 347–399 (2023).

Konopka, A., Lindemann, S. & Fredrickson, J. Dynamics in microbial communities: unraveling mechanisms to identify principles. ISME J. 9, 1488–1495 (2015).

Widder, S. et al. Challenges in microbial ecology: Building predictive understanding of community function and dynamics. ISME J. 10, 2557–2568 (2016).

Faust, K. & Raes, J. Microbial interactions: from networks to models. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 538–550 (2012).

Topcuoglu, B. D., Lesniak, N. A., Ruffin, M. T., Wiens, J. & Schlossa, P. D. A framework for effective application of machine learning to microbiome-based classification problems. Mbio 11, 434 (2020).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215 (2019).

Huttenhower, C., Finn, R. D. & McHardy, A. C. Challenges and opportunities in sharing microbiome data and analyses. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 1960–1970 (2023).

Knight, R. et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 410–422 (2018).

Banerjee, S., Schlaeppi, K. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 567–576 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Keystone taxa mediate the trade-off between microbial community stability and performance in activated sludges. Nat. Water 3, 723–733 (2025).

Herren, C. M. & McMahon, K. D. Keystone taxa predict compositional change in microbial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2207–2217 (2018).

Jordan, M. I. & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 349, 255–260 (2015).

Yang, Z., Zhang, A. & Sudjianto, A. Net: an explainable neural network based on generalized additive models with structured interactions. Pattern Recognit. 120, 108192 (2021).

Agarwal, R. et al. Neural additive models: interpretable machine learning with neural nets. In Proc. 35th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). (NIPS Paper, 2021).

Bai, X., Dinkla, I. J. T. & Muyzer, G. Microbial ecology of biofiltration used for producing safe drinking water. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 4813–4829 (2022).

Pinto, A. J., Xi, C. & Raskin, L. Bacterial community structure in the drinking water microbiome is governed by filtration processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 8851–8859 (2012).

Pinto, A. J., Schroeder, J., Lunn, M., Sloan, W. & Raskin, L. Spatial-temporal survey and occupancy-abundance modeling to predict bacterial community dynamics in the drinking water microbiome. Mbio 5, 1135 (2014).

Levy, R. & Borenstein, E. Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12804–12809 (2013).

Montano Lopez, J., Duran, L. & Avalos, J. L. Physiological limitations and opportunities in microbial metabolic engineering. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 35–48 (2022).

Yang, X. et al. Unveiling the deterministic dynamics of microbial meta-metabolism: a multi-omics investigation of anaerobic biodegradation. Microbiome 12, 166 (2024).

Galand, P. E., Pereira, O., Hochart, C., Auguet, J. C. & Debroas, D. A strong link between marine microbial community composition and function challenges the idea of functional redundancy. ISME J. 12, 2470–2478 (2018).

Wang, X. W. et al. Identifying keystone species in microbial communities using deep learning. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 22–31 (2024).

Jousset, A. et al. Where less may be more: how the rare biosphere pulls ecosystems strings. ISME J. 11, 853–862 (2017).

Zhu, C. et al. Global diversity and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in human wastewater treatment systems. Nat. Commun. 16, 4006 (2025).

Rissanen, A. J., Ojala, A., Fred, T., Toivonen, J. & Tiirola, M. Methylophilaceae and Hyphomicrobium as target taxonomic groups in monitoring the function of methanol-fed denitrification biofilters in municipal wastewater treatment plants. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44, 35–47 (2017).

Martineau, C., Villeneuve, C., Mauffrey, F. & Villemur, R. Complete genome sequence of Hyphomicrobium nitrativorans strain NL23, a denitrifying bacterium isolated from biofilm of a methanol-fed denitrification system treating seawater at the montreal biodome. Genome Announc. 2, e01165–01113 (2014).

Sack, E. L. W., van der Wielen, P. W. J. J. & van der Kooij, D. Flavobacterium johnsoniae as a model organism for characterizing biopolymer utilization in oligotrophic freshwater environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6931–6938 (2011).

Basson, A., Flemming, L. A. & Chenia, H. Y. Evaluation of adherence, hydrophobicity, aggregation, and biofilm development of Flavobacterium johnsoniae-like isolates. Microb. Ecol. 55, 1–14 (2008).

Li, Y. et al. The critical roles of biofilm property and community structure in adaptability of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms to the toxicity of coking wastewater. Desalination 603, 118653 (2025).

Louca, S. et al. Function and functional redundancy in microbial systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 936–943 (2018).

Rahmani, A. M. et al. Machine learning (ML) in medicine: Review, applications, and challenges. Mathematics 9, 2970 (2021).

Allison, S. D. & Martiny, J. B. H. Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11512–11519 (2008).

Ramond, P., Galand, P. E. & Logares, R. Microbial functional diversity and redundancy: moving forward. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 49, fuae031 (2025).

Wyss, R. et al. Machine learning for improving high-dimensional proxy confounder adjustment in healthcare database studies: an overview of the current literature. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 31, 932–943 (2022).

Ling, F., Hwang, C., LeChevallier, M. W., Andersen, G. L. & Liu, W. T. Core-satellite populations and seasonality of water meter biofilms in a metropolitan drinking water distribution system. ISME J. 10, 582–595 (2016).

Shade, A. et al. Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 3, 417 (2012).

Miao, L. et al. Distinct community structure and microbial functions of biofilms colonizing microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 2395–2402 (2019).

Miao, L. et al. Low concentrations of copper oxide nanoparticles alter microbial community structure and function of sediment biofilms. Sci. Total Environ. 653, 705–713 (2019).

Liao, R. et al. Temperature dependence of denitrification microbial communities and functional genes in an expanded granular sludge bed reactor treating nitrate-rich wastewater. RSC Adv. 8, 42087–42094 (2018).

Garcia, F. C. et al. The temperature dependence of microbial community respiration is amplified by changes in species interactions. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 272–283 (2023).

Clegg, T. & Pawar, S. Variation in thermal physiology can drive the temperature-dependence of microbial community richness. Elife 13, 84662 (2024).

Smith, T. P. et al. Latent functional diversity may accelerate microbial community responses to temperature fluctuations. Elife 11, 80867 (2022).

Butler, O. M., Manzoni, S. & Warren, C. R. Community composition and physiological plasticity control microbial carbon storage across natural and experimental soil fertility gradients. ISME J. 17, 2259–2269 (2023).

Dai, T. et al. Nutrient supply controls the linkage between species abundance and ecological interactions in marine bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 13, 175 (2022).

Cao, Q. et al. Compartmentation of microbial communities in structure and function for methane oxidation coupled to nitrification-denitrification. Bioresour. Technol. 341, 125761 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Soil biofilm formation enhances microbial community diversity and metabolic activity. Environ. Int. 132, 105116 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Global marine microbial diversity and its potential in bioprospecting. Nature 633, 371–379 (2024).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 590–596 (2013).

Santos, M. S., Soares, J. P., Abreu, P. H., Araujo, H. & Santos, J. Cross-validation for imbalanced datasets: avoiding overoptimistic and overfitting approaches. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 13, 59–76 (2018).

Ayyubi, R. A. W. et al. Machine learning-assisted high-throughput prediction and experimental validation of high-responsivity extreme ultraviolet detectors. Nat. Commun. 16, 6265 (2025).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Pioneering Projects for Disciplinary Breakthroughs of the Ministry of Education of China, National Center for Basic Sciences of China (52388101), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (China) (KYCX24_0322).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J. Investigation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft. J.Z. Formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft. H.Z. Investigation. R.M. Investigation. H.H. Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. H.R. Conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Haihan Zhang and Somaparna Ghosh A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, L., Zhang, J., Zhao, H. et al. Ecological levers for microbially driven water treatment enhance pollutant removal prediction. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1036 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02996-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02996-6