Abstract

Paleoenvironmental reconstructions in southern Africa have often relied on isolated or fragmentary records, limiting our understanding of ecosystem dynamics during the Middle Stone Age (c. 300–40 ka). Here, we reassess vegetation and climate change between Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 5 and 3 using high-resolution pollen records from two deep-sea cores—MD96-2048 (eastern margin) and MD96-2098 (western margin)—and contextualize these data with other marine (MD20-3592; 3CD154-17-17K) and terrestrial records. The pollen sequences reveal coherent, regionally synchronous trends: glacial periods were cooler and wetter, reflected in the expansion of Fynbos and Afromontane Forest, while interglacials were drier, marked by forest retreat and Nama-Karoo spread. In contrast to terrestrial records, which often reflect localized and inconsistent patterns due to taphonomic and ecological factors, these offshore archives provide a robust sub-continental signal. Comparisons with archaeological data suggest that the Still Bay (SB) technocomplex emerged near the MIS 5a/4 transition, during a humid phase of elevated environmental productivity. The Howiesons Poort (HP) technocomplex appeared slightly later ( ~ 68–64 ka), under conditions of climatic instability and ecological fragmentation. These contrasting ecological backdrops imply that cultural change was not driven by climate alone, but by complex interactions between environmental variability, technological innovation, and population connectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent research has increasingly emphasized the importance of refugia dynamics and population structure in shaping the evolutionary trajectory of Homo sapiens in Africa. Rather than evolving in a single, continuous population, growing evidence suggests that early modern humans emerged within a network of spatially and temporally subdivided populations, often isolated in environmentally stable regions, or refugia, during periods of climatic instability1,2,3. These refugia likely facilitated regional continuity, allowing populations to persist and adapt locally while periodically exchanging genes and cultural traits through pulses of connectivity. This scenario challenges both the classic “Out-of-Africa” model and simple multiregional frameworks, pointing instead to a “metapopulation” structure within Africa that produced deep lineages and complex admixture histories2,3,4.

In parallel, palaeoanthropological evidence now supports the idea that the distinctive anatomical features of Homo sapiens did not emerge all at once in a single region, but rather accumulated over time in different populations across the continent. Fossil specimens such as those from Jebel Irhoud (Morocco), Omo Kibish (Ethiopia), Florisbad (South Africa), and Herto (Ethiopia) reveal a patchwork of derived and ancestral traits, consistent with a model of morphological accretion within a geographically structured species2,5,6,7. This further undermines the idea of a single speciation event occurring in East or South Africa and instead aligns with a pan-African perspective on our origins.

The implications of this new paradigm are profound for understanding patterns of technological and cultural evolution. Distinct regional trajectories of innovation may result from variable ecological conditions, social networks, and demographic configurations, leading to ecocultural niche expansions or contractions8,9 argue. Periods of isolation may have fostered cultural drift or independent innovation, while episodes of increased mobility and intergroup contact—both possibly triggered by environmental change—could lead to cultural convergence, diffusion, or rapid transmission of innovations. This picture undermines the notion of a sudden “behavioural revolution” and instead supports a view of gradual, mosaic-like development of behavioural complexity, shaped by long-term ecological pressures and the evolutionary consequences of population fragmentation, bottlenecks, and reconnection9. In this framework, refugia function not merely as passive shelters, but as active engines of evolutionary and cultural change, enabling resilience, experimentation, and innovation under shifting climatic regimes.

Southern Africa, the focus of this synthesis, has long been considered as a region where climatic variability may have played a crucial role in the emergence of early modern humans along with associated behavioural innovations, demographic expansion and dispersal events 10.

Key archaeological discoveries have highlighted the region’s pivotal role in shaping our understanding of cultural transformations during the Late Pleistocene (Supplementary Information 1). Between MIS 5 and MIS 3, Middle Stone Age (MSA) populations in southern Africa developed a broad range of complex behaviours that reflect advanced cognitive, social, and technological capacities. A wide range of models have been proposed to explain how climate dynamics shaped the trajectory of cultural evolution in this region (Supplementary Information 1).

Despite the diversity of models proposed, a fundamental challenge remains: the construction of regionally coherent palaeoclimate records for southern Africa. Since the early days of Quaternary climate research in southern Africa, scholars have questioned the feasibility of constructing regionally coherent precipitation trends, given the continent climatic heterogeneity11,12. While some reconstructions suggest northward expansion of the Winter Rainfall Area during glacial periods13,14,15, others maintain dominance of the Summer Rainfall Area across the subcontinent16,17. Recent works have emphasized the pronounced spatial and temporal heterogeneity in rainfall regimes18,19,20,21,22. Terrestrial archives often yield divergent local signals due to taphonomic processes, and site-specific ecological conditions—particularly in faunal datasets23. Continuous vegetation-based reconstructions remain scarce, due to poor fossil preservation and limited chronological control in many sequences 23,24,25,26.

Marine pollen records offer an alternative. Offshore sediments from the margins of southern Africa preserve continuous, well-dated archives of continental vegetation dynamics and climate variability24,27,28,29,30. These records are especially valuable for reconstructing long-term trends during MIS 5 to 3—periods poorly captured in most terrestrial sequences.

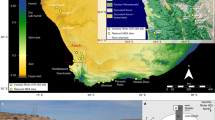

This study re-evaluates climatic and ecological dynamics between MIS 5 to MIS 3 by integrating high-resolution pollen data from two strategically located deep-sea sediment cores: MD96-2048 (eastern margin; 24) and MD96-2098 (western margin; 31). These records are compared with additional marine palaeoclimatic proxies31,32,33,34 and contextualized with terrestrial evidence from vegetal macroremains, and faunal assemblages (large and small mammals) commonly used in palaeoenvironmental reconstructions (Fig. 1). By combining multiple datasets and perspectives, this study aims to:

A Biomes and archaeological sites discussed in the text. The red dashed line marks the boundary between fine-leaved and broad-leaved savannas, corresponding to a shift in precipitation regime shown in (B). B Mean Annual Precipitation across southern Africa, and the Limpopo and Orange river basins (grey dashed line). Biome classification follows58. Mean Annual Precipitation is derived from the WorldClim dataset143. Rivers and river basins are from HydroSHEDS144. Red asterisks indicate the locations of the deep-sea cores analyzed in this study; other deep-sea cores are labelled according to the climate proxy data discussed in the text. 1: Apollo 11; 2: Spitzkloof; 3: Boegoeberg 1; 4: Varsche Rivier 003; 5: Hollow Rock Shelter; 6: Klein Kliphuis; 7: Klipfonteinrand 1; 8: Diepkloof; 9: Ysterfontein; 10: Die Kelders; 11: Klipdrift; 12: Blombos; 13: Pinnacle Point; 14: Klasies River Mouth; 15: Florisbad; 16: Rose Cottage; 17: Bushman’s Rock Shelter; 18: Border Cave; 19: Sibudu; 20: Umlahtuzana; 21: Tswaing Crater; 22: Wonderkrater; 23: Brandberg; 24: Mirabib; 25: Rietvlei; 26: Vankersvevlei.

(i) clarify the relative influence of regional climatic forcing versus local ecological responses; and

(ii) evaluate how these dynamics may have shaped the development of MSA cultural innovations across southern Africa.

Our results reveal regionally coherent vegetation and climate trends, with glacial phases generally wetter and interglacials drier. These robust signals, distinct from localized terrestrial records, provide a sub-continental framework for contextualizing cultural developments and suggest that cultural change was shaped by the interplay of climate, technological innovation, and population connectivity.

Results and discussion

Vegetation changes from MIS 5 to 3 in the eastern and western part of Southern Africa

Orbital- and millennial-scale climate variability drove major ecological changes across southern Africa during the MSA. In particular, Northern Hemisphere ice-sheet dynamics caused latitudinal shifts in the ITCZ, weakening northern monsoons and enhancing southern precipitation during cold events35,36,37,38. As a result, glacial periods in southern Africa were generally wetter, while interglacials were warmer and drier—in opposition to the Northern Hemisphere 39,40,41,42,43,44.

High-resolution pollen records from MD96-2048 (east) and MD96-2098 (west) reveal distinct biome responses, dominated by Poaceae, Cyperaceae, Asteraceae, and either Podocarpaceae (east) or Restionaceae (west). Although these two records cannot capture the full evolution of southern Africa vegetation, their strategic locations integrate signals from two major drainage basins—the Limpopo in the east and the Orange in the west (Fig. 1B). Together, they provide complementary perspectives for comparing eastern Afromontane Forest/savanna and western Nama-Karoo/Fynbos biome responses to climatic forcing. Moreover, the biomes and seasonal climate of the southern Orange River basin extend into the southwestern Cape region, suggesting that inferences on vegetation and climate from this record are also relevant further south. Likewise, the biomes and overall humid climate of the eastern Limpopo basin extend into adjacent regions to the east and south, providing a broader regional framework for interpreting the pollen records.

The most pronounced changes occurred during MIS 5, subdivided into warm 5e,5c,5a and cool (5 d, 5b) substages. In MD96-2048, Podocarpaceae dominates though it may be overrepresented in marine sequences due to its high dispersal capacity24,45. Peaks during the cooler substages, suggest this moisture-dependent taxon was limited by warm, possibly drier interglacials (Fig. 2A)24. Nonetheless, compared to MIS 6 and MIS 4 glacial stages, Podocarpaceae representation was lower, indicating that glacial conditions constrained its expansion24,46. Present-day ecology of Podocarpus henkelii supports this pattern, preferring high rainfall and moderate temperatures47. At IODP Site U1479, Podocarpaceae displays similar trends, despite the lower resolution of the site 33.

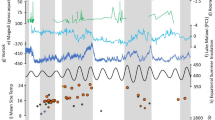

A MD96-2048 (eastern Southern Africa); B MD96-2098 (western Southern Africa). Both panels also display precession (red curve) and δ¹⁸O values (blue line) as climatic context proxies. Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) and substages are indicated at the top. Taxa are grouped by ecological preference: Podocarpaceae and Cyperaceae are associated with more humid, forested or high-altitude environments; Poaceae with open, grassy, and drier habitats; Asteraceae and Restionaceae with Fynbos and transitional shrubland environments. Arrows indicate moisture preference inferred for each taxon. These sequences illustrate vegetation responses to orbital-scale climatic shifts, highlighting contrasts and synchronies between the eastern and western parts of South Africa (see Supplementary Data 1).

Although the cooler conditions of MIS 4 did not generally support major expansions of Podocarpaceae, a peak in this taxon is observed towards the end of this period (Fig. 2A). This expansion corresponds to Heinrich Stadial (HS) 6 (63.2–60.1 ka)48, suggesting increasing humid conditions. These results are consistent with the findings of Ziegler et al. (2013)31 (XRF analyses from CD154-17-17K deep-sea core) which argued that episodes of northern hemisphere dry/cool conditions related to Dansgaard-Oeschger and Heinrich events were linked to increased humidity in southern Africa.

During MIS 3—a period of intermediate ice volume—several rapid transitions from cold to mild conditions known as Dansgaard-Oeschger (DO) warming events occurred49. The MD96-2048 pollen record does not permit detection of such rapid changes, showing only two increases in Podocarpaceae pollen percentages at the beginning and end of MIS 3 (Fig. 2A).

In MD96-2098 (west), Poaceae dominates, reflecting dry Nama-Karoo/Fine-Leaved savanna biomes (Fig. 2B, see Methods). High Poaceae percentages occur during MIS 5 warm substages. Previous analyses of this deep-sea core also indicated that cold substages were relatively humid, associated with Fynbos expansion and increased biomass burning 50,51.

Poaceae values drop during full glacials (MIS 6, MIS 4), consistent with a moister Southern Hemisphere glacial climate38. A similar decline during HS 6 also indicates increased humidity (Fig. 2B). MIS 3 Poaceae levels are lower than during MIS 5 but comparable to MIS 4, suggesting slightly wetter conditions. This interpretation aligns with evidence for increased moisture in the Cape region during this interval52,53, which likely limited the expansion of Poaceae into Fynbos-dominated landscapes. However, climatic instability and the absence of clear Dansgaard-Oeschger signals limit interpretation.

Poaceae and Podocarpaceae show an inverse relationship, with alternating peaks at ~127, 115, 105, 100, 90, and 84 ka. MIS 5e (127 ka) shows high Poaceae and low Podocarpaceae, while MIS 5 d (115 ka) shows the opposite (Fig. 3). However, during MIS 5c (~105 ka), Podocarpaceae declines but Poaceae shows only a minor increase. Instead, Cyperaceae increases modestly in both cores relative to MIS 5 d (Fig. 2), suggesting slightly wetter conditions, but not enough to trigger extensive Fynbos or Afromontane Forest growth. Both taxa rise thereafter with Podocarpaceae peaking around 90 ka (MIS 5b) and Poaceae peaking at 84 ka (MIS 5a).

Temporal trends in dominant taxa and their responses to glacial–interglacial variability between 180 and ~25 ka are illustrated. A Interpolated Poaceae pollen percentages from MD96-2098 (grey line and yellow dashed trend line), with binned values superimposed (yellow markers); B Interpolated Podocarpaceae pollen percentages from MD96-2048 (pink line and blue dashed trend line), with binned values superimposed (blue markers); C Comparison of interpolated sequences for Poaceae from MD96-2098 (black) and Podocarpaceae from MD96-2048 (red), highlighting inverse trends between the western and eastern records. Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) and substages are indicated in background shading; D Binned Poaceae (green dashed) and Cyperaceae (blue dashed) sequences from MD96-2098, with inferred relative humidity trends (pale blue shading for wetter phases and pale yellow for drier intervals). These panels demonstrate regionally distinct vegetation dynamics and shifting precipitation regimes across southern Africa from MIS 6 to MIS 3.

Between MIS 5b and MIS 5a, both records show parallel environmental shifts: humid conditions peak in MIS 5b, followed by a progressive drying trend toward MIS 5a (Fig. 3). Pollen data suggests that MIS 5b was generally more humid than MIS 5a (Fig. 2). Cyperaceae, an indicator of moist, high-altitude environments54,55, support a transition from warmer/drier conditions in MIS 5a to colder/wetter conditions approaching the MIS 5a/4 boundary (Fig. 2).

While Podocarpaceae (MD96-2048) and Poaceae (MD96-2098) are key indicators of biome change, other taxa also show important trends. In MD96-2048, Cyperaceae expansion is linked to Fynbos-like open vegetation during full glacial periods, while Asteraceae and Poaceae reflect drier shrubland components56. Although less abundant, peaks in Asteraceae and Poaceae during MIS 5e and MIS 3 correspond to low Cyperaceae values, suggesting drier conditions (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the expansion and contraction of Afromontane forests (e.g., Podocarpaceae) may have influenced the distribution of grasses and sedges, as increased forest cover could have limited light availability, thereby suppressing these open vegetation elements 57.

In MD96-2098, Cyperaceae remains consistently low. Both Cyperaceae and Restionaceae decline during MIS 5e and 5a, while Poaceae increases, indicating drier conditions (Fig. 2B). Asteraceae patterns differ between cores: in MD96-2048, they broadly follow Poaceae trends, but in MD96-2098, they are inversely related. Asteraceae peaks during glacials, suggesting an affinity with winter rainfall and Fynbos vegetation50. This supports its role as a Fynbos indicator in the west, becoming more dominant towards the southern and western Nama-Karoo, near the Fynbos boundary, where winter rainfall is more prevalent58. The inverse relationship between Asteraceae and Poaceae in MD96-2098 likely reflects rainfall seasonality—Poaceae linked to summer rainfall, Asteraceae to winter precipitation 59.

Spatio-temporal evolution of southern African ecosystems

Palaeoenvironmental reconstructions in southern Africa have traditionally relied on pollen, macro- and microfauna23,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68. Yet comparative syntheses remain scarce, especially for small mammals, with most of their assemblages approximately covering the last 20,000 years and often restricted to the Cape Floristic Region60,61,63,69,70. For large mammals, few biome-scale shifts across the Pleistocene are found23, while small mammals exhibit no major taxonomic changes since the Early Pleistocene71,72. This apparent stasis may reflect limitations in the resolution of fossil assemblages, time-averaging effects, or ecological adaptability and plasticity of species

Faunal responses—especially amongst small mammals with limited dispersal capabilities—are more frequently detected in ecotonal areas, where biomes transitions occur. In contrast, fossil sites situated deep into biome interiors are less likely to register subtle or even major environmental shifts 73,74,75.

Accumulation processes also play a significant role in shaping faunal assemblages. Most fossil accumulations of both macro- and micromammals are predator-derived72,76,77,78,79,80, reflecting local hunting ranges, and, consequently, localized environmental conditions rather than broader regional trends72,76,81. Despite these constraints, faunal and botanical data can still be compared with regional climate signals from the marine pollen data, particularly for MIS 5-3 interval (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 2), though differences in chronological resolution and data quality make such correlations tentative.

A Relative abundance of key pollen taxa (Podocarpaceae and Cyperaceae) from marine core MD96-2048 (eastern margin), serving as indicators of forest expansion and wetland development, respectively; B Pollen records from sites near MD96-2048 interpreted as reflecting dominance of wet or dry conditions during the periods of the pollen zones identified; C Large mammal trends from archaeological sites near MD96-2048, interpreted as reflecting dominance of browsing versus grazing taxa; D Small mammal-based habitat reconstructions from Border Cave using the Habitat Weighting Method, indicating proportions of grassland, woodland/shrubland, and wetland environments; E Pollen records from sites near MD96-2098 interpreted as reflecting dominance of wet or dry conditions during the periods of the pollen zones identified. F Poaceae pollen percentages from marine core MD96-2098 (western margin), interpreted as a proxy for the extent of open, grassy vegetation; G Large mammal trends from sites near MD96-2098, reflecting relative proportions of grazers and browsers; H Small mammal habitat trends from Klasies River and Blombos, indicating vegetation openness, substrate conditions, and proportions of moist vs. dry grasses. Yellow arrows indicate increasing trends; red arrows indicate declining trends. Chronological subdivisions follow Marine Isotope Stages (MIS). Together, these data highlight spatial and temporal variation in vegetation structure and rainfall regimes across South Africa during the late Middle and early Late Pleistocene (data used is presented in Supplementary Data 2).

MIS 5

In eastern South Africa, Bushman’s Rock Shelter and Florisbad offer contrasting signals. Bushman’s Rock Shelter (MIS 5e) contains a high proportion of browsers, suggesting forested refugia; Florisbad shows more grazers, consistent with Nama-Karoo and Fine-Leaved savanna expansion82,83, aligning with high Poaceae in MD96-209850 (Fig. 4A, B). Sclerocarya birrea at Bushman’s Rock supports warm, Savanna-like conditions with local tree cover 83.

At Border Cave (MIS 5b/a), large and small mammal data indicate grassland expansion and increased grazing taxa84,85, but charcoal records suggest a mixed Savanna/Bushveld-Grassland mosaic86. Terrestrial pollen sequence from Tswaing Crater point to warm, arid Savanna conditions around 75–72 ka87, opposing to faunal proxies.

In the Cape Floristic Region, Diepkloof and Ysterfontein show a shift from grazers (MIS 5d–c) to browsers (MIS 5b–a)88, whereas Pinnacle Point shows the opposite trend. Klasies River mirrors the Diepkloof and Ysterfontein sequences, with an early browser increase during MIS 5c. Browsers dominate Blombos during MIS 5c and MIS 5a/4 transition67,89. This pattern of increasing browsing fauna towards MIS 5a does not correspond to expansion of grasses observed in the MD96-2098 sequence for this substage.

Small mammal data from Blombos Cave and Klasies River indicate increasingly open landscapes with moist/dry grass cover. Klasies River shows a gradual trend, while Blombos suggest sandy substrates and subtle shifts in moist/dry grass cover during MIS 5c–5b (Fig. 4F). These more open environments inferred from small mammals contrast with large mammal signal, possibly reflecting localized microhabitats or taphonomic processes81. At Blombos, evidence for sandy substrate reduction near 70 ka may indicates increased moisture81, consistent with declining Poaceae in MD96-2098 and inferred regional humidity50 (Fig. 4D). In contrast, leaf wax records from Blombos indicate increasing aridity over a broadly comparable interval33. The terrestrial pollen sequence from Vankervelsvlei also spans the period from MIS 5 d to MIS 5a, but wet conditions appear to have prevailed throughout the period. The main difference is that before 95 ka, higher Podocarpus pollen indicates reduced rainfall seasonality, whereas after 95 ka a sharp increase in Ericaceae suggests a shift toward greater winter rainfall 90.

MIS 4 to 3

Marine pollen cores show consistent signals of glacial humidity during MIS 4. In MD96-2048, Cyperaceae increases and Podocarpaceae declines, suggesting high-altitude wetland expansion and forest reduction. In MD96-2098, Poaceae declines while Fynbos indicators (Asteraceae, Restionaceae) increase24,50. At Wonderkrater, wet conditions around 70 ± 10 ka are recorded91; Tswaing Crater documents increased humidity from ~72–68 ka, followed by aridity around 63–60 ka87. However, a ~ 5,000-year hiatus affects direct correlation. The higher-resolution MD96-2098 core suggests increasing aridity after 64 ka, interrupted by a humid phase during HS 6 (~60 ka).

Sites near MD96-2048, such as Border Cave and Sibudu, show browser-dominated faunas indicative of wooded habitats82,92,93,94,95. Charcoal confirms forest taxa at Border Cave between 72 and 56 ka86. In contrast, Bushman’s Rock Shelter remains grazer-dominated, likely reflecting its ecotonal setting 83.

Small mammal assemblages at Border Cave suggest an increase in woodland/shrubland cover from MIS 5b/a to MIS 4. During MIS 3, a decline in freshwater indicators is observed (Fig. 4C), coinciding with reduced Cyperaceae pollen percentages in core MD96-2048 at ~60 ka (Fig. 4A). Cyperaceae, however, recovers rapidly around 57 ka in both MD96-2048 and terrestrial pollen sequences from Tswaing Crater and Wonderkrater (Fig. 4A, B)87, while small-mammal freshwater indicators continue to decline. At Tswaing, Scott (2016)87 identified a wet interval between 60 and 45 ka, whereas at Wonderkrater, alternating wet and dry phases were recorded87. By contrast, Puech et al. (2017)91 reported evidence for drier conditions at Wonderkrater dated to >45 ka. The differing chronological frameworks, however, complicate direct comparison of these records for this period.

A subsequent warm, possibly dry phase is recorded between 46–41 ka, marked by Savanna grassland expansion in both terrestrial pollen sequences and a decrease in Cyperaceae pollen in MD96-2048. These conditions are followed by a humid phase around 40.5 ka, indicated by the recovery of the Fynbos component at Tswaing Crater87, which is also reflected in MD96-2048 (Fig. 4A).

In the Cape Floristic Region, large mammals during MIS 4 also indicate browsers, matching marine pollen evidence for dense Fynbos and Afromontane vegetation21,24,50. At Vankervelsvlei, increased Fynbos pollen is recorded between 70–60 ka90, while Apollo 11 and Diepkloof show evidence of woody vegetation expansion and forest development21,96. The Vankervelsvlei pollen record also suggests a brief arid pulse around 67 ka; nonetheless, MIS 4 is generally regarded as a humid period, with Ericaceae, Canthium and Morella serving as key indicators of cool,moist conditions 90.

The Agulhas Plain supported productive herbivore communities with mixed C₃/C₄ vegetation97,98,99,100, explaining grazer dominance at Klipdrift and Klasies23. Northward, Boegoeberg 1 is grazer-dominated, while Apollo 11 shows more browsers, possibly reflecting local habitat differences. Faunal data are sparse, but in the Cape region, four sites preserve MIS 3 mammal assemblages—three are grazer-dominated, while Spitzkloof (52–51 ka) is browser-rich. However, Spitzkloof provides insufficient evidence to assess whether its unique faunal pattern reflects taphonomic effects, localized conditions or a short climatic episode.

Terrestrial pollen records from MIS 3 vary substantially by site, possibly due to geographic differences or dating uncertainty (Fig. 4F). This variability makes direct correlation with the higher-resolution marine records difficult, but overall trends suggest local environmental variability due to differing geographic settings.

Ecosystem dynamics and cultural innovation

The combined marine and terrestrial datasets presented here offered a picture of palaeoenvironmental variability across southern Africa during the MSA, particularly between MIS 5 and MIS 4 (Fig. 5). However, terrestrial datasets often displayed different environmental signals, which sometimes were limited due to chronological uncertainties.

The panels illustrate major palaeoenvironmental and cultural trends associated with shifts in precipitation and biome dynamics across southern Africa during MIS 5–4. A, B Maps of Africa showing latitudinal shifts in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the corresponding influence of austral summer and winter rainfall patterns during warm (A) and cold (B) stages. Spatio-temporal distribution of vegetation types, large and small mammal habitat preferences, and archaeological technocomplexes across southern Africa during: (C) MIS 5e; (D) MIS 5 d; (E) MIS 5c; (F) MIS 5b; (G) MIS 5a; (H) MIS 4. Yellow and blue background shadings represent the inferred extent of arid and humid zones, respectively. Arrows indicate expansions (upward) or contractions (downward) of key biomes, including Nama-Karoo (red), Afromontane forests (dark green), Fynbos (purple), and sedge-rich wetlands (blue). Symbols indicate faunal and archaeological indicators: Large mammals: grazers (green squares) and browsers (brown squares); Small mammals: grassy habitats (light green rosettes), wooded/shrubby habitats (dark green rosettes); Technocomplexes: Still Bay (orange circles) and Howiesons Poort (blue triangles).

Between MIS 5e and MIS 5a (~130–80 ka), the archaeological record shows marked technological diversity. Industries like MSA I and II, the Pietersburg, and early coastal variants reflect fragmented cultural trajectories across biomes101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117. This regional diversification likely arose from population fragmentation in heterogeneous environments, with limited cultural transmission between groups5,116,118,119. In sites like Sibudu, the 74–67 ka levels yield a stratigraphic sequence with technological features suggesting the existence of another, yet unnamed, technocomplex. Similar patterns may be present at Umhlatuzana and Melikane, reinforcing the idea that MIS 5 witnessed a proliferation of regionally distinct cultural entities 119,120,121.

Towards the MIS 5a/4 transition, this fragmented landscape gives way to the first widely recognizable cultural convergence: the SB. Temporal ranges obtained through Chronomodel122 for the SB, place this technocomplex between 76–67 ka (Fig. 6A). SB sites—e.g., Blombos, Sibudu, Diepkloof—are characterized by pressure-flaked bifacial points and, depending on the site, additional innovations such as engraved ochres, bone tools, and personal ornaments123. Its appearance coincides with a humid, cool phase marked by increased Fynbos (west) and Afromontane Forest persistence (east) (Fig. 6C), and partial exposure of the Agulhas coastal plain during marine regression97,98. These conditions likely supported high biomass and expanded habitable zones, facilitating social contact and symbolic innovation.

A Chronomodel estimations of the high probability density intervals (95%) for the group of dates in each technocomplex. B Orbital precession curve (30°S latitude), illustrating the precessional forcing potentially linked to climatic and cultural shifts. C Selected palaeoclimatic proxies from marine cores MD96-2098 (right column)50 and MD96-2048 (left column)24: First row: Poaceae (representing Nama-Karoo and Fine-leaved Savanna) and Podocarpaceae (Afromontane forests). Second row: Asteraceae (Fynbos-like component, MD96-2098) and Cyperaceae (Fynbos-like component, MD96-2048). Third row: Microcharcoal (fire activity, MD96-2098)51 and Fe/Ca ratio (XRF-based precipitation proxy, MD96-2048)55. Fourth row: Fe/Ca ratio (XRF-based precipitation proxy from MD20-3592 and CD154-17-17K)32,34. Coloured vertical bands mark the high probability density intervals of the Still Bay (yellow) and Howiesons Poort (blue) technocomplexes. Arrows indicate ecological preferences for each proxy (dry/wet or temperate/cold). Pollen taxa are grouped into major biomes based on ecological affinities. See Supplementary Data 1 for proxy data sources and details.

In contrast, the HP follows a short hiatus ( ~ 3 ka). As emphasized by Lombard et al. (2022)124, the apparent gap may in part reflect a complex interplay of factors, including dating approaches, assemblage categorisation, and site-specific taphonomic processes. In addition, regional variability in site occupation and sampling intensity may also contribute to the impression of a discontinuity. These considerations suggest that the “hiatus” should not be seen as a uniform cultural or behavioural break, but rather as a pattern that may differ across regions and datasets. Nonetheless, a detailed discussion of the precise start and ends of these technocomplexes, as well as the nature of the hiatus, lies beyond the scope of this paper (see refs. 124,125,126,127,128).

Chronomodel results indicate that the HP spans ~64–60 ka. The HP arose and end during peaks of aridity (as best observed in the MD96-2098 record), with a wetter interval occurring midway through it, likely corresponding with HS 6 (Figs. 2 and 6C). This indicates that the HP coincided with a period of climatic instability, marked by repeated shifts between Fynbos and Nama-Karoo vegetation in the west50, and cycles of sedges expansion and contraction in the east. These conditions of higher ecological risk likely promoted mobility and interregional connections, possibly explaining the HP’s broader coherence. For both techno-complexes, regional proxy records in Fig. 6 appear to consistently reflect similar climatic conditions in both the western and eastern regions of southern Africa.

Despite these apparent correlations, several unresolved questions remain, for which environmental data alone do not yet offer clear answers: What explains the persistence of highly variable technological traditions throughout MIS 5? This pattern suggests limited cultural transmission between groups, despite occasional climatic opportunities for connectivity (Supplementary Information 1). Why did the Still Bay emerge when it did, and why in such a geographically limited coastal region? Its apparent association with expanding resource-rich coastal plains suggests ecological facilitation, but the specific social or cognitive mechanisms behind its innovations remain unclear. What mechanisms drove the dramatic technological and symbolic shift between SB and HP? Is a chronological hiatus between them real or the result of taphonomic and sampling gaps? Although some sequences suggest temporal overlap or continuity (e.g., at Sibudu), others point to a gap in occupation or production. While the HP retains some symbolic practices, the disappearance of bifacial points and shift to microlithic technology suggests a major cultural reorganization. This shift is difficult to attribute solely to climatic change and may reflect social reconfiguration or cultural loss. The question remains whether this reflects real population fragmentation, sampling bias, or issues with chronometric resolution. Why do post-HP assemblages show reduced symbolic expression? Environmental changes may have played a role, but the uneven geographic distribution and persistence of certain behaviours point to more complex cultural dynamics. These open questions underscore the need to move beyond deterministic models that attribute cultural shifts solely to climatic forcing. Instead, our findings support a model in which environmental change acts as both a constraint and an enabler—shaping resource availability, influencing patterns of connectivity, and interacting with demographic and social structures in complex ways. Periods of ecological stability and resource abundance, such as during the expansion of the Agulhas coastal plain in MIS 5a/4, may have promoted aggregation, strengthened social networks, and facilitated the circulation of symbolic practices and technological know-how. Conversely, phases of climatic instability, such as those characterizing the HP, likely heightened ecological risk, encouraging greater mobility and interregional contacts as groups sought to buffer uncertainty. These dynamics may have created conditions favourable to innovation, by both concentrating populations in resource-rich refugia and stimulating the exchange of ideas across wider territories. While these scenarios remain hypothetical, they illustrate how environmental variability could have influenced not only subsistence strategies but also the tempo and scale of cultural transmission. Multi-scalar approaches, integrating high-resolution palaeoecological data with detailed archaeological and chronological analyses, remain essential for disentangling the drivers of innovation and behavioural evolution in the deep human past. Yet, climatic trends alone cannot fully account for the emergence, disappearance, or transformation of technocomplexes such as Still Bay and Howiesons Poort. A multi-scalar perspective—integrating demography, landscape use, and cultural transmission—is essential for addressing the remaining uncertainties in the MSA record of southern Africa.

Methods

Southern Africa modern environmental setting

Climate

This region is presently characterized by a highly diverse array of landscapes and climatic regimes, shaped by its broad geographical extent, complex geological history, and varied topography58. Modern southern Africa exhibits pronounced interannual rainfall variability and hosts a range of climatic zones, from the Mediterranean climate of the Western Cape, to the (semi-) desert conditions of the North and West Coast, to the subtropical climate of the eastern regions. Three principal rainfall zones are commonly recognized: (A) the Winter Rainfall Zone (WRZ), dominated by frontal systems associated with the westerly storm track that migrates northward during the austral winter; (B) the Summer Rainfall Zone (SRZ), influenced by tropical easterly moisture originating over the Indian Ocean during the summer months; and (C) the Azonal Rainfall Zone (ARZ), which receives precipitation year-round from both sources 44,59,60,61.

Vegetation

Precipitation is the primary climatic factor controlling vegetation in southern Africa. The austral summer rainfall regime is largely governed by the position of tropical low-pressure systems, particularly the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)61. During the austral winter, as these systems migrate northward, subtropical high-pressure cells expand over southern Africa, reducing precipitation. As a result, the region’s vegetation has been broadly classified into seven major biomes: the succulent Karoo, Nama-Karoo, desert, savanna, fynbos, grassland, and forests58 (Fig. 1A).

The western part of southern Africa is dominated by desert, Nama-Karoo, and fine-leaved savannah biomes (Fig. 1A), all of which are shaped by arid to semi-arid conditions (Fig. 1B). Low precipitation in this region is largely influenced by the cold Benguela Current and wind-driven upwelling, which contribute to dryness on the adjacent continent62. The desert biome receives as little as 20 mm of mean annual precipitation63. Moving south-eastward, this biome transitions into the Nama-Karoo, which is primarily influenced by austral summer rainfall and receives between 60 and 400 mm annually64. Vegetation in this biome consists of dwarf open shrubland, with high abundances of Poaceae, Asteraceae, Aizoaceae, Mesembryanthemaceae, Liliaceae, and Scrophulariaceae 58.

The savanna biome, characterized by high rainfall seasonality, receives most of its precipitation during the austral summer. It comprises a mosaic of shrublands, dry forests, lightly wooded grasslands, and deciduous woodlands58,124. Based on moisture availability and soil type, savannas are often classified into fine-leaved or broad-leaved types129. The fine-leaved savanna—typical of the region close to core MD96-2098—occurs under drier conditions (400–800 mm/year) and is dominated by C4 grasses (Poaceae) and succulent species, with sparse tree cover52. In contrast, broad-leaved savannas, found in more humid zones with up to 1,500 mm/year of rainfall (131; Fig. 1A and B), are populated by woody species in the Caesalpiniaceae and Combretaceae families, with an understory dominated by grasses (66; Fig. 1A and B).

The eastern part of South Africa is characterized by closed forests, broad-leaved savannas, and grasslands. The warm Agulhas Current delivers humid air masses inland, particularly across lowlands and upland slopes contributing to summer-dominant rainfall regimes. Late summer precipitation is further enhanced by rising sea surface temperatures in the Agulhas system130,131. Closed forests, including cloud forests dominated by Podocarpus, are present in this region132. Broad-leaved savannas in the east typically support tree species of Caesalpiniaceae and Combretaceae, with a grass dominated understory124. Modern pollen spectra show the highest Poaceae percentages (up to 90%) in these broad-leaved savanna regions of eastern and northeastern southern Africa50. The grassland biome, which receives between 750 and 1,200 mm of rainfall annually, is dominated by C4 grasses alongside non-grassy forbs, such as Anthospermum sp., Lycium sp., Solanum sp., and Pentzia sp133. At higher elevations, C3 replace C4 taxa, reflecting cooler and wetter microclimates.

These biome-specific differences in vegetation and precipitation regimes (Fig. 1A and B) provide an ideal framework for comparing fluctuations between humid and arid phases. In particular, they allow for the examination of how moist and dry pulses impacted ecological distinct regions across southern Africa.

Pollen samples

We reanalysed the pollen records from deep-sea cores MD96-2098 (25°36’S, 12°38’E) and MD96-2048 (26°10’S, 34°01’E) to assess potential differences in vegetation responses to climate change across South Africa (Supplementary Data 1). These deep-sea cores are from two opposite regions of South Africa. Core MD96-2098 was retrieved at a depth of 2910 m from the Lüderitz slope in the Walvis Basin, approximately 500 km northwest of the Orange River mouth (Fig. 1). In contrast, core MD96-2048 was collected at a depth of 660 m on the upper continental slope east of Maputo, south of the Limpopo River mouth (Fig. 1).

Pollen sums from MD96-2098 ranged from 100 to 240 grains per sample (n = 141), with concentrations of 300–16,000 grains ml⁻¹ during most of MIS 6, 5, and 3, and peaks of up to 48,000 grains ml⁻¹ during MIS 4. Pollen grains are well preserved at this site, where the Benguela Upwelling System favours the preservation of organic microfossils50. The core lies close to the coast and thus near the primary vegetation source of the Orange River basin. Most of the pollen is likely of fluvial origin, transported northward by the Benguela Current plume, which entrains fine particles discharged from the Orange River mouth. Pollen grains are well preserved at this site, as the Benguela Upwelling System promotes the preservation of pollen and other organic microfossils.

For MD96-2048, pollen sums ranged between 100 and 390 grains (including spores) per sample, with a few samples yielding fewer than 100 grains. Concentrations are generally lower (<2000 grains ml⁻¹), particularly in the older part of the sequence (340–120 ka), which largely falls outside the scope of this study. Maxima exceeding 4000 grains ml⁻¹ occur at levels dated to ca. 115, 90, 70, and 60–40 ka, before declining again after 40 ka24. The state of preservation is less well documented for this core, but concentrations are consistent with the short distance to the coast (<120 km) and the influence of the Limpopo River. Low terrestrial input indicated by organic geochemistry (Dupont et al., 2011) further explains the generally low pollen concentrations.

The observed differences in pollen preservation and concentration between the two records thus primarily reflect depositional context, vegetation source proximity, and local ecological conditions, rather than analytical biases. Both cores span MIS 6 to MIS 3, and comparisons between them were conducted at the family level, considering only taxa that together account for at least 80% of each sample.

Pollen diagrams were constructed to provide a detailed graphical representation of pollen fluctuations over time. To capture overall trends in both marine sequences, the BINCOR package from R was used134. Originally designed for analysing unevenly spaced time series with non-zero persistence and time intervals not significantly exceeding persistence times, BINCOR avoids the need to interpolate data to an equidistant and uniform time series. However, when data do not fully meet these assumptions, the package’s binning functionality remains valuable for segmenting data into intervals (bins). This process helps reveal underlying trends while reducing noise without relying entirely on interpolation. Therefore, pollen sequences were interpolated at 10 ka intervals between 25 and 183 ka for comparison and posteriorly binned.

Faunal database for MIS 5 and MIS 3 stages

Information derived from pollen, macrofauna, and microfauna from terrestrial sequences was compiled for comparative analysis. Sites with dated sequences falling within the time span of interest (MIS 5 to MIS 3) were selected and summarized in Supplementary Data 2.

Pollen sequences were re-analysed based on indicators of humid or arid conditions as defined within the pollen zones and their corresponding chronologies as established by the original authors. This approach was preferred due to difficulties in making direct comparisons arising from chronological gaps and uncertainties in the dating of these sequences. The inferred wet/dry conditions were then compared with the corresponding climatic indicators derived from the deep-sea cores analysed in this study.

For macrofauna, environmental inferences were based on the presence of grazers and browsers. The grazer/browser ratio is a well-established proxy for evaluating changes in vegetation structure, particularly in distinguishing between more open and closed habitats 23,62,67,68,82,95.

For small mammals, the dataset includes both the presence or absence of environmental indicator species and habitat reconstructions based on the Habitat Weighting Method. This quantitative approach assigns taxa a value between 0 and 1 based on their habitat preferences. The main habitats defined for South Africa135,136,137 include forest, woodland, bushland, grassland, semi-arid environments, rocky areas and wetlands. This classification works well for the interior and eastern areas, characterized by the presence of Afromontane forests, savanna and grasslands. For the sites located in the Cape Floristic Region, the classification adapted by Nel and Henshilwood65 was applied. This classification considers seven different habitats: moist grass, dry grass, bush, shrubland, coastal scrub, rocky and sandy substrates. Chronological information for each site was compiled from the original publications. Where radiometric control was available, we used the minimum and maximum ages reported by the original authors to align sequences with the MIS framework adopted in this study. For sites with limited chronological resolution, we relied on the broader age ranges proposed in the literature and correlated them with the onset and end of the relevant MIS intervals. Given that the quality of these age constraints varies considerably, our comparisons focus on broad MIS-level patterns rather than fine-scale correlations, and alignments between marine and terrestrial archives should be regarded as tentative.

Technocomplexes and chronological contexts

Towards the end of MIS 5a and into MIS 4, two major lithic technocomplexes emerge that have been extensively studied: the Still Bay (SB) and the Howiesons Poort (HP). The SB is primarily associated with archaeological sites located along the southern African coast. It is characterized by the production of bifacial foliate points, often crafted from fine-grained, non-local lithic materials138,139. Most SB sites have yielded optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dates ranging from approximately 76 to 71 ka. However, the accuracy of this range is debated, as older OSL and thermoluminescence (TL) dates have been reported from Diepkloof Rock Shelter.

In contrast, the HP technocomplex is found in both coastal and inland contexts across southwestern and northeastern South Africa. HP assemblages are marked by a high frequency of backed tools, including segments, triangles, and trapezes, typically manufactured from fine-grained raw materials139,140. Chronometric data, primarily derived from OSL and TL techniques, suggest that the HP lasted slightly longer than the SB, with most dates falling between approximately 66 and 59 ka. As with SB, some OSL dates from Diepkloof are considerably older than the main body of available dates.

Supplementary Data 1 lists all sites with their corresponding chronometric data and technocomplex attributions. To estimate the most probable age ranges for these technocomplexes, Chronomodel (v3.2; 124) was used. Ages associated with the Still Bay and Howiesons Poort technocomplexes were compiled from the dataset reviewed by Hallett et al.141. Diepkloof Rock Shelter was not included among the sites considered due to ongoing debate surrounding its older optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) and thermoluminescence (TL) dates for both technocomplexes, which remain unique and have yet to be confirmed127,142. As the primary aim was to determine the most probable temporal ranges for the occurrence of both technocomplexes, dates were entered into the model as “Events,” each assigned to the relevant technocomplex. The dating method for each entry was specified accordingly. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation was run using the program’s default settings (Number of chains: 3; Burn-in iterations: 1,000; Batches: 200; Acquisition iterations: 100,000). The output provided the most probable distributions, represented by the 95% High Probability Density (HPD) intervals, delineated by the most probable minimum and maximum ages.

Data availability

Supplementary data cited in this work are freely available at the following link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30436759. Data on the Howiesons Poort and Still Bay chronologies provided in Supplementary Data 1 can also be accessed directly from the original publication: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09154-0.

References

Blinkhorn, J. et al. Evaluating refugia in recent human evolution in Africa. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 377, 20200485 (2022).

Scerri, E. M. et al. Did our species evolve in subdivided populations across Africa, and why does it matter?. Trends Ecol Evol 33, 582–594 (2018).

Scerri, E. M., Chikhi, L. & Thomas, M. G. Beyond multiregional and simple out-of-Africa models of human evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1370–1372 (2019).

Bergström, A., Stringer, C., Hajdinjak, M., Scerri, E. M. & Skoglund, P. Origins of modern human ancestry. Nature 590, 229–237 (2021).

Hublin, J. J. et al. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 546, 289–292 (2017).

Stringer, C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 371, 20150237 (2016).

Groucutt, H. S. et al. Rethinking the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa. Evol. Anthropol. Issues. News. Rev 24, 149–164 (2015).

d’Errico, F. & Banks, W. E. Identifying mechanisms behind middle paleolithic and middle stone age cultural trajectories. Curr. Anthropol. 54, S371–S387 (2013).

Scerri, E. M. & Will, M. The revolution that still isn’t: The origins of behavioral complexity in Homo sapiens. JHE 179, 103358 (2023).

Vrba, E. S., Denton, G. H., Partridge, T. C. & Burckle, L. H. (Eds.). Paleoclimate and evolution, with emphasis on human origins. (Yale University Press, 1995).

Gasse, F., Chalié, F., Vincens, A., Williams, M. A. & Williamson, D. Climatic patterns in equatorial and southern Africa from 30,000 to 10,000 years ago reconstructed from terrestrial and near-shore proxy data. Quat. Sci. Revs 27, 2316–2340 (2008).

Burrough, S. L. & Thomas, D. S. Central southern Africa at the time of the African Humid Period: a new analysis of Holocene palaeoenvironmental and palaeoclimate data. Quat. Sci. Revs 80, 29–46 (2013).

Stuut, J. B. W., Crosta, X., Van der Borg, K. & Schneider, R. Relationship between Antarctic sea ice and southwest African climate during the late Quaternary. Geology 32, 909–912 (2004).

Shi, N., Schneider, R., Beug, H. J. & Dupont, L. M. Southeast trade wind variations during the last 135 kyr: evidence from pollen spectra in eastern South Atlantic sediments. EPSL 187, 311–321 (2001).

Chase, B. M. South African palaeoenvironments during marine oxygen isotope stage 4: a context for the Howiesons Poort and Still Bay industries. J. Archaeol. Sci 37, 1359–1366 (2010).

Lee-Thorp, J. A. & Beaumont, P. B. Vegetation and seasonality shifts during the late Quaternary deduced from 13C/12C ratios of grazers at Equus Cave, South Africa. Quat. Res. 43, 426–432 (1995).

Partridge, T. C., Demenocal, P. B., Lorentz, S. A., Paiker, M. J. & Vogel, J. C. (1997). Orbital forcing of climate over South Africa: a 200,000-year rainfall record from the Pretoria Saltpan. Quat. Sci. Revs. 16, 1125–1133 (1997).

Scott, L. et al. Terrestrial fossil-pollen evidence of climate change during the last 26 thousand years in Southern Africa. Quat. Sci. Revs. 32, 100–118 (2012).

Norström, E. et al. Late Quaternary vegetation dynamics and hydro-climate in the Drakensberg, South Africa. Quat. Sci. Revs. 105, 48–65 (2014).

Stone, A. E. Last Glacial Maximum conditions in southern Africa: Are we any closer to understanding the climate of this time period?. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 38, 519–542 (2014).

Chase, B. M. & Meadows, M. E. Late Quaternary dynamics of southern Africa’s winter rainfall zone. Earth-Sci. Rev. 84, 103–138 (2007).

Chevalier, M. & Chase, B. M. Southeast African records reveal a coherent shift from high-to low-latitude forcing mechanisms along the east African margin across last glacial–interglacial transition. Quat. Sci. Revs 125, 117–130 (2015).

Reynard, J. P. Paradise lost: large mammal remains as a proxy for environmental change from MIS 6 to the Holocene in southern Africa. SAJG 124, 1055–1072 (2021).

Dupont, L. M. et al. Glacial-interglacial vegetation dynamics in South Eastern Africa coupled to sea surface temperature variations in the Western Indian Ocean. Clim. Past. 7, 1209–1224 (2011).

Scott, L. & Neumann, F. H. Pollen-interpreted palaeoenvironments associated with the Middle and Late Pleistocene peopling of Southern Africa. Quat. Int 495, 169–184 (2018).

Meadows, M. E., Chase, B. M. & Seliane, M. Holocene palaeoenvironments of the Cederberg and Swartruggens mountains, Western Cape, South Africa: pollen and stable isotope evidence from hyrax dung middens. J. Arid Environ. 74, 786–793 (2010).

Dupont, L. & Behling, H. Land–sea linkages during deglaciation: High-resolution records from the eastern Atlantic off the coast of Namibia and Angola (ODP site 1078). Quat. Int 148, 19–28 (2006).

Hooghiemstra, H., Stalling, H., Agwu, C. O. & Dupont, L. M. Vegetational and climatic changes at the northern fringe of the Sahara 250,000–5000 years BP: evidence from 4 marine pollen records located between Portugal and the Canary Islands. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol 74, 1–53 (1992).

Leroy, S. & Dupont, L. Development of vegetation and continental aridity in northwestern Africa during the Late Pliocene: the pollen record of ODP Site 658. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 109, 295–316 (1994).

Lézine, A. M. & Hooghiemstra, H. Land-sea comparisons during the last glacial-interglacial transition: pollen records from West Tropical Africa. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 79, 313–331 (1990).

Ziegler, M. et al. Development of Middle Stone Age innovation linked to rapid climate change. Nat. Commun. 4, 1905 (2013).

Göktürk, O. M. et al. Behaviourally modern humans in coastal southern Africa experienced an increasingly continental climate during the transition from Marine Isotope Stage 5 to 4. Front. Earth. Sci. 11, 1198068 (2023).

Dupont, L. M., Zhao, X., Charles, C., Faith, J. T. & Braun, D. Continuous vegetation record of the Greater Cape Floristic Region (South Africa) covering the past 300 000 years (IODP U1479). Clim. Past. 18, 1–21 (2022).

Purcell, K. et al. Climate variability off Africa’s southern Cape over the past 260, 000 years. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-2499 (2024).

Castañeda, I. S. et al. Wet phases in the Sahara/Sahel region and human migration patterns in North Africa. PNAS 106, 20159–20163 (2009).

Johnson, T. C. et al. A high-resolution paleoclimate record spanning the past 25,000 years in southern East Africa. Science 296, 113–132 (2002).

Schefuß, E., Kuhlmann, H., Mollenhauer, G., Prange, M. & Pätzold, J. Forcing of wet phases in southeast Africa over the past 17,000 years. Nature 480, 509–512 (2011).

Weij, R. et al. Elevated Southern Hemisphere moisture availability during glacial periods. Nature 626, 319–326 (2024).

Helmens, K. F. The Last Interglacial–Glacial cycle (MIS 5–2) re-examined based on long proxy records from central and northern Europe. Quat. Sci. Revs. 86, 115–143 (2014).

Oliveira, D. et al. The complexity of millennial-scale variability in southwestern Europe during MIS 11. Quat. Res. 86, 373–387 (2017).

Oliveira, D. et al. Unravelling the forcings controlling the vegetation and climate of the best orbital analogues for the present interglacial in SW Europe. Clim. Dyn. 51, 667–686 (2018).

Sánchez-Goñi, M. F. et al. Pollen from the deep-sea: A breakthrough in the mystery of the Ice Ages. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 38 (2018).

Sánchez-Goñi, M. F. Regional impacts of climate change and its relevance to human evolution. Evol. Hum. Sci. 2, e55 (2020).

Wagner, B. et al. Mediterranean winter rainfall in phase with African monsoons during the past 1.36 million years. Nature. 573, 256–260.

Coetzee, J. A. Pollen analytical studies in east and southern Africa. Palaeoeco. A. 3, 1–146 (1967).

Shin, S. I. et al. A simulation of the Last Glacial Maximum climate using the NCAR-CCSM. Clim. Dynam. 20, 127–151 (2003).

Twala, T. C., Fisher, J. T. & Glennon, K. L. Projecting Podocarpaceae response to climate change: we are not out of the woods yet. AoB Plants 15, plad034 (2023).

Sánchez-Goñi, M. F. & Harrison, S. P. Millennial-scale climate variability and vegetation changes during the Last Glacial: Concepts and terminology. Quat. Sci. Revs. 29, 2823–2827 (2010).

Svensson, A. et al. A 60 000 year Greenland stratigraphic ice core chronology. Clim. Past. 4, 47–57 (2008).

Urrego, D. H., Sánchez Goñi, M. F., Daniau, A. L., Lechevrel, S. & Hanquiez, V. Increased aridity in southwestern Africa during the warmest periods of the last interglacial. Clim. Past. 11, 1417–1431 (2015).

Daniau, A. L. et al. Precession and obliquity forcing of the South African monsoon revealed by sub-tropical fires. Quat. Sci. Rev. 310, 108128 (2023).

Cowling, R. M., Esler, K. J., Midgley, G. F. & Honig, M. A. Plant functional diversity, species diversity and climate in arid and semi-arid southern Africa. J. Arid Environ. 27, 141–158 (1994).

Parkington, J., Cartwright, C., Cowling, R. M., Baxter, A. & Meadows, M. Palaeovegetation at the last glacial maximum in the western Cape, South Africa: wood charcoal and pollen evidence from Elands Bay Cave. S. Afr. J. Sci. 96, 543–546 (2000).

Cordova, C. E. & Scott, L. The potential of Poaceae, Cyperaceae, and Restionaceae phytoliths to reflect past environmental conditions in South Africa. APGLE. 107-134 (2010).

Caley, T. et al. A two-million-year-long hydroclimatic context for hominin evolution in southeastern Africa. Nature 560, 76–79 (2018).

Dupont, L. M., Caley, T. & Castañeda, I. S. Effects of atmospheric CO 2 variability of the past 800 kyr on the biomes of southeast Africa. Clim. Past. 15, 1083–1097 (2019).

Moncrieff, G. R., Scheiter, S., Slingsby, J. A. & Higgins, S. I. Understanding global change impacts on South African biomes using Dynamic Vegetation Models. S. Afr. J. Bot. 101, 16–23 (2015).

Mucina, L., Rutherford, M. C. & Powrie, L. W. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. (South African National Biodiversity Institute, 2006).

Fitchett, J. M. & Bamford, M. K. The validity of the Asteraceae: Poaceae fossil pollen ratio in discrimination of the southern African summer-and winter-rainfall zones. Quat. Sci. Revs. 160, 85–95 (2017).

Avery, D. M. Micromammals as palaeoenvironmental indicators and an interpretation of the late Quaternary in the southern Cape Province, South Africa. Ann. S. Afr. Mus. 85, 183–374 (1981).

Avery, D. M. Micromammals and the environment of early pastoralists at Spoeg River, western Cape Province, South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 47, 116–121 (1992).

Badenhorst, S., Van Niekerk, K. L. & Henshilwood, C. S. Large mammal remains from the 100 ka middle stone age layers of Blombos cave, South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 46-52 (2016).

Faith, J. T., Chase, B. M. & Avery, D. M. Late Quaternary micromammals and the precipitation history of the southern Cape, South Africa. Quat. Res. 91, 848–860 (2019).

Hare, V. & Sealy, J. Middle Pleistocene dynamics of southern Africa’s winter rainfall zone from δ13C and δ18O values of Hoedjiespunt faunal enamel. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 374, 72–80 (2013).

Nel, T. H. & Henshilwood, C. S. The small mammal sequence from the c. 76–72 ka Still Bay levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa–Taphonomic and palaeoecological implications for human behaviour. PONE 11, e0159817 (2016).

Nel, T. H., Wurz, S. & Henshilwood, C. S. Small mammals from marine isotope stage 5 at Klasies River, South Africa–reconstructing the local palaeoenvironment. Quat. Int. 471, 6–20 (2018).

Reynard, J. P. & Henshilwood, C. S. Environment versus behaviour: zooarchaeological and taphonomic analyses of fauna from the Still Bay layers at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Quat. Int. 500, 159–171 (2019).

Reynard, J. P. & Wurz, S. The palaeoecology of Klasies River, South Africa: An analysis of the large mammal remains from the 1984–1995 excavations of Cave 1 and 1A. Quat. Sci. Revs. 237, 106301 (2020).

Avery, D. M. Late Pleistocene coastal environment of the southern Cape province of South Africa: micromammals from Klasies River mouth. J. Archaeol. Sci. 14, 405–421 (1987).

Matthews, T., Denys, C. & Parkington, J. E. The palaeoecology of the micromammals from the late middle Pleistocene site of Hoedjiespunt 1 (Cape Province, South Africa). JHE 49, 432–451 (2005).

Avery, D. M. Rodents and other micromammals from the Pleistocene strata in Excavation 1 at Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa: A work in progress. Quat. Int. 614, 23–36 (2022).

Linchamps, P. et al. Fossil micromammals and the palaeoenvironments of the Paranthropus robustus site of Cooper’s Cave. Hist. Biol. 36, 905–920 (2024).

García-Morato, S. Tafonomía de micromamíferos, paleoecología y variabilidad de fenómenos climáticos. en el hemisferio norte y sur durante el Holoceno (Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, (2023).

García-Morato, S., Domínguez-García, ÁC., Sevilla, P., Laplana, C. & Fernández-Jalvo, Y. The last 20,000 years of climate change in the Iberian Peninsula characterized by the small-mammal assemblages. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 655, 112545 (2024).

García-Morato, S. et al. New palaeoecological approaches to interpret climatic fluctuations in Holocenic sites of the Pampean Region of Argentina. Quat. Sci. Revs. 255, 106816 (2021).

Linchamps, P. New modern and Pleistocene fossil micromammal assemblages from Swartkrans, South Africa: Paleobiodiversity, taphonomic, and environmental context. JHE 200, 103636 (2025).

Andrews, P. Owls, caves and fossils (University of Chicago Press, 1990).

Badenhorst, S., Ezeimo, J., van Niekerk, K. L. & Henshilwood, C. S. Differential accumulation of large mammal remains by carnivores and humans during the Middle Stone Age in the Eastern and Western Cape, South Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 35, 102752 (2021).

Faith, J. T. Ungulate diversity and precipitation history since the Last Glacial Maximum in the Western Cape, South Africa. Quat. Sci. Revs. 68, 191–199 (2013).

Thompson, J. C. & Henshilwood, C. S. Taphonomic analysis of the Middle Stone Age larger mammal faunal assemblage from Blombos Cave, southern Cape, South Africa. JHE 60, 746–767 (2011).

Nel, T. H. & Henshilwood, C. S. The 100,000–77,000-year old Middle Stone Age micromammal sequence from Blombos Cave, South Africa: Local climatic stability or a tale of predator bias?. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 38, 443–476 (2021).

Brink, J. S. The taphonomy and palaeoecology of the Florisbad spring fauna. PoA 19, 169–179 (1988).

Badenhorst, S. & Plug, I. The faunal remains from the Middle Stone Age levels of Bushman Rock Shelter in South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 67, 16–31 (2012).

Tribolo, C. et al. Luminescence dating at Border Cave: attempts, questions, and new results. Quat. Sci. Revs. 296, 107787 (2022).

Avery, D. M. The environment of early modern humans at Border Cave, South Africa: micromammalian evidence. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 91, 71–87 (1992). b.

Lennox, S., Backwell, L., d’Errico, F. & Wadley, L. A vegetation record based on charcoal analysis from Border Cave, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa,∼ 227 000 to∼ 44 000 years ago. Quat. Sci. Revs. 293, 107676 (2022).

Scott, L. Fluctuations of vegetation and climate over the last 75 000 years in the Savanna Biome, South Africa: Tswaing Crater and Wonderkrater pollen sequences reviewed. Quat. Sci. Revs. 145, 117–133 (2016).

Klein, R. G. et al. The Ysterfontein 1 Middle Stone Age site, South Africa, and early human exploitation of coastal resources. PNAS 101, 5708–5715 (2004).

Discamps, E. & Henshilwood, C. S. Intra-site variability in the Still Bay fauna at Blombos Cave: implications for explanatory models of the Middle Stone Age cultural and technological evolution. PONE 10, e0144866 (2015).

Quick, L. J. et al. Vegetation and climate dynamics during the last glacial period in the fynbos-afrotemperate forest ecotone, southern Cape, South Africa. Quat. Int. 404, 136–149 (2016).

Puech, E., Urrego, D. H., Sánchez-Goñi, M. F., Backwell, L. & d’Erricoc, F. Vegetation and environmental changes at the middle stone age site of Wonderkrater, Limpopo, South Africa. Quat. Res. 88, 313–326 (2017).

Backwell, L. et al. The antiquity of bow-and-arrow technology: evidence from Middle Stone Age layers at Sibudu Cave. Antiq 92, 289–303 (2018).

Allott, L. F. Archaeological charcoal as a window on palaeovegetation and wood-use during the Middle Stone Age at Sibudu Cave. South. Afr. Humanit. 18, 173–201 (2006).

Hall, G. & Woodborne, S. M. Ecosystem change during MIS4 and early MIS 3: Evidence from Middle Stone Age sites in South Africa. (CRC Press, 2010).

Klein, R. G. The mammalian fauna from the middle and later stone age (later Pleistocene) levels of Border Cave, Natal Province, South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 32, 14–27 (1977).

Vogelsang, R. et al. New excavations of Middle Stone Age deposits at Apollo 11 Rockshelter, Namibia: stratigraphy, archaeology, chronology and past environments. J. Afr. Archaeol. 8, 185–218 (2010).

Cowling, R. M. et al. Describing a drowned Pleistocene ecosystem: last Glacial Maximum vegetation reconstruction of the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain. Quat. Sci. Revs. 235, 105866 (2020).

Marean, C. W. et al. in Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region (eds. Allsopp, N., Colville, J. F. & Verboom, T.) 164-199 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Helm, C. W. et al. Pleistocene vertebrate tracksites on the Cape south coast of South Africa and their potential palaeoecological implications. Quat. Sci. Revs. 235, 105857 (2020).

Venter, J. A., Brooke, C. F., Marean, C. W., Fritz, H. & Helm, C. W. Large mammals of the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain showed resilience to extreme climate change but vulnerability to modern human impacts. Quat. Sci. Revs. 235, 106050 (2020).

Wadley, L. Those marvellous millennia: the Middle Stone Age of southern Africa. Azania 50, 155–226 (2015).

Singer, R. & Wymer, J. The middle stone age at Klasies River mouth in South Africa (University of Chicago Press, 1982).

Wurz, S. The middle stone age at Klasies river, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, 2000).

Wurz, S. Variability in the middle stone age lithic sequence, 115,000–60,000 years ago at Klasies river, South Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. 29, 1001–1015 (2002).

Porraz, G. et al. The MSA sequence of Diepkloof and the history of southern African Late Pleistocene populations. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 3542–3552 (2013).

Douze, K., Wurz, S. & Henshilwood, C. S. Techno-cultural characterization of the MIS 5 (c. 105–90 Ka) lithic industries at Blombos Cave, Southern Cape, South Africa. PONE 10, e0142151 (2015).

Thompson, E., Williams, H. M. & Minichillo, T. Middle and late Pleistocene middle stone age lithic technology from Pinnacle point 13B (Mossel Bay, western Cape province, South Africa). JHE 59, 358–377 (2010).

Wurz, S. The significance of MIS 5 shell middens on the Cape coast: A lithic perspective from Klasies River and Ysterfontein 1. Quat. Int. 270, 61–69 (2012).

Will, M., Parkington, J. E., Kandel, A. W. & Conard, N. J. Coastal adaptations and the Middle Stone Age lithic assemblages from Hoedjiespunt 1 in the western Cape, South Africa. JHE 64, 518–537 (2013).

Volman, T. P. Early archeological evidence for shellfish collecting. Science 201, 911–913 (1978).

Volman, T. P. The middle stone age in the Southern Cape (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Chicago, 1981).

Backwell, L. R. et al. New excavations at border cave, KwaZulu-natal, South Africa. J. Field Archaeol. 43, 417–436 (2018).

de la Peña, P. et al. Revisiting Mwulu’s Cave: new insights into the Middle Stone Age in the southern African savanna biome. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 11, 3239–3266 (2019).

Feathers, J. K., Evans, M., Stratford, D. J. & de la Peña, P. Exploring complexity in luminescence dating of quartz and feldspars at the Middle Stone Age site of Mwulu’s Cave (Limpopo, South Africa). Quat. Geochronol. 59, 101092 (2020).

Porraz, G. et al. Bushman Rock Shelter (Limpopo, South Africa): a perspective from the edge of the Highveld. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 70, 166–179 (2015).

Porraz, G. et al. The MIS5 Pietersburg at ‘28’Bushman Rock Shelter, Limpopo Province, South Africa. PONE 13, e0202853 (2018).

Val, A. et al. The place beyond the trees: renewed excavations of the Middle Stone Age deposits at Olieboomspoort in the Waterberg Mountains of the South African Savanna Biome. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 116 (2021).

Mackay, A., Jacobs, Z. & Steele, T. E. Pleistocene archaeology and chronology of Putslaagte 8 (PL8) rockshelter, Western Cape, South Africa. J. Afr. Archaeol. 13, 71–98 (2015).

Pazan, K. R., Dewar, G. & Stewart, B. A. The MIS 5a (~ 80 ka) Middle Stone Age lithic assemblages from Melikane Rockshelter, Lesotho: highland adaptation and social fragmentation. Quat. Int. 611, 115–133 (2022).

Rots, V., Lentfer, C., Schmid, V. C., Porraz, G. & Conard, N. J. Pressure flaking to serrate bifacial points for the hunt during the MIS5 at Sibudu Cave (South Africa). PONE 12, e0175151 (2017).

Schmid, V. C., Porraz, G., Zeidi, M. & Conard, N. J. Blade technology characterizing the MIS 5 DA layers of Sibudu Cave, South Africa. Lithic Technol 44, 199–236 (2019).

Lanos. Ph. & Dufresne, Ph. ‘ChronoModel version 3.0: Software for Chronological Modelling of Archaeological Data using Bayesian Statistics’. Available at https://chronomodel.com/ (2024).

d’Errico, F. et al. Identifying early modern human ecological niche expansions and associated cultural dynamics in the South African Middle Stone Age. PNAS 114, 7869–7876 (2017).

Lombard, M. et al. The Southern African stone age sequence updated (II). Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 77, 172–212 (2022).

Jacobs, Z. et al. Ages for the Middle Stone Age of southern Africa: implications for human behavior and dispersal. Science 322, 733–735 (2008).

Guérin, G. et al. How confident are we in the chronology of the transition between Howieson’s Poort and Still Bay?. J. Hum. Evol. 64, 314–317 (2013).

Tribolo, C. et al. OSL and TL dating of the Middle Stone Age sequence at Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): A clarification. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 3401–3411 (2013).

Jacobs, Z. & Roberts, R. G. Single-grain OSL chronologies for the Still Bay and Howieson’s Poort industries and the transition between them: Further analyses and statistical modelling. J. Hum. Evol. 107, 1–13 (2017).

Scholes, R. J. in Vegetation of Southern Africa, (ed. Cowling, R. M., Richardson, D. M. & Pierce, S. M.) 258–277 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997).

Jury, M. R., Valentine, H. R. & Lutjeharms, J. R. Influence of the Agulhas Current on summer rainfall along the southeast coast of South Africa. JAMC 32, 1282–1287 (1993).

Reason, C. J. C. & Mulenga, H. Relationships between South African rainfall and SST anomalies in the southwest Indian Ocean. Int. J. Climatol. 19, 1651–1673 (1999).

Rutherford, M. C., Powrie, L. W. & Schulze, R. E. Climate change in conservation areas of South Africa and its potential impact on floristic composition: a first assessment. Divers. Distrib. 5, 253–262 (1999).

O’Connor, T. G. & Bredenkamp, G. J. in Vegetation of Southern Africa (ed. Cowling, R. M., Richardson, D. M. & Pierce, S. M.) 215–257 (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Polanco-Martínez, J. M., Medina-Elizalde, M., Sánchez-Goñi, M. F. & Mudelsee, M. BINCOR: An R package for Estimating the Correlation between Two Unevenly Spaced Time Series. The R Journal 11, 1–14 (2019).

Evans, E. N., Van Couvering, J. A. & Andrews, P. Palaeoecology of Miocene sites in western Kenya. JHE 10, 99–116 (1981).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. et al. Taphonomy and palaeoecology of Olduvai bed-I (Pleistocene, Tanzania). JHE 34, 137–172 (1998).

Andrews, P. Taphonomic effects of faunal impoverishment and faunal mixing. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 241, 572–589 (2006).

Porraz, G. et al. Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 3376–3400 (2013).

Wurz, S. Technological trends in the Middle Stone Age of South Africa between MIS 7 and MIS 3. Curr. Anthropol. 54, 305–319 (2013).

Bader, G. D., Schmid, V. C. & Kandel, A. W. in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology, (2022).

Hallett, E. Y. et al. Major expansion in the human niche preceded out of Africa dispersal. Nature, (2025).

Tribolon, C. et al. Thermoluminescence dating of a Stillbay–Howiesons Poort sequence at Diepkloof Rock Shelter (Western Cape, South Africa). J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 730–739 (2009).

Hijmans, R. J. et al. Very high-resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978 (2005).

Lehner, B. & Grill, G. Global River hydrography and network routing: baseline data and new approaches to study the world’s large river systems. Hydrol. Process. 27, 2171–2186 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Fyssen Foundation 2024 Postdoctoral Program, which supported SGM through a one-year contract at the University of Bordeaux for the project Unravelling climate and ecosystem dynamics and their influence on human societies: Palaeoecological insights across hemispheres. Additional financial support was provided by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades and Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Projects PID2021-126933NB-I00 and i-COOP 2024_COOPB24012, respectively). Research by MFSG and FD is supported by the Grand Programme de Recherche ‘Human Past’ of the Initiative d’Excellence (IdEx) at the University of Bordeaux. FD’s research is also supported by the University of Bordeaux Talents Programme (grant number: 191022_001) and the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, SFF Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour (SapienCE), project number 262618.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sara García-Morato: developed the study design, sourced and collected the data, analysed the data and created the figures, led the writing of the manuscript, discussed results, contributed to the manuscript prior to submission. María Fernanda Sánchez-Goñi: supervisor, developed the study design, discussed results, contributed to the manuscript prior to submission. Dunia H. Urrego: discussed results, contributed to the manuscript prior to submission. Francesco d’Errico: developed the study design, discussed results, contributed to the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Jessica Zappa and Peng Lu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yama Dixit, Joe Aslin and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Morato, S., Sánchez-Goñi, M.F., Urrego, D.H. et al. Climatic variability, vegetation dynamics, and cultural innovation in Southern Africa during the Middle Stone Age. Commun Earth Environ 7, 75 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03051-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03051-0