Abstract

Here, we combine scenario analysis with machine learning to assess the impact of China’s carbon neutrality policy on the reduction of toxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), as quantified by their toxic equivalency emissions (EBaPeq). Using long-term (2000–2023) energy consumption data and provincial projections to 2060, we show that national EBaPeq is expected to peak around 2027 due to policy impacts, and then fall by 45% by 2060. This peak timing proves robust to data uncertainties. However, a pronounced north-south divide persists: northern regions, constrained by coal-dependent energy systems and aluminum-smelting industries, will peak later, whereas central and southern China achieved their peaks before 2012. This regional imbalance in emission intensity per GDP may widen under certain growth pathways. We propose targeted policies—such as cross-regional technology transfer, differentiated transition roadmaps, and improved ecological compensation—to support more equitable and synergistic abatement of carbon and toxic pollutants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global expansion of population and fossil fuel consumption presents a profound challenge on reconciling economic development with the imperative to reduce pollutant emissions1,2,3. This challenge is exemplified by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), toxic by-products of incomplete combustion from both fossil fuels and biomass, which pose significant threats to ecosystems and human health4,5. Historically, environmental risk assessments have relied on total PAH emissions (EΣPAHs) as a primary metric6,7. However, this mass-based approach can be profoundly misleading for risk assessment. Due to the vast differences in toxic equivalency factor (TEF) among individual PAHs (Supplementary Table 1), EΣPAHs often correlate poorly with actual health impacts. A stark illustration from China’s 2007 inventory shows that while phenanthrene emissions were 30 times greater than those of benzo[a]pyrene, the latter’s toxic equivalency emissions (EBaPeq) were 85 times higher due to its vastly greater TEF8. This critical disconnect between mass and toxicity is not merely theoretical9. A recent global study reported a 2.8% decline in EΣPAHs from 2012 to 2015, yet a concurrent 40.3% surge in projected lifetime lung cancer deaths10. Notably, China, despite achieving the world’s most significant EΣPAHs reductions, experienced the highest rise in such deaths10. This global evidence underscores an urgent imperative to shift the paradigm of PAH assessment from mass-based inventories to toxicity-weighted emissions (EBaPeq).

This paradigm shift finds a crucial and timely application in China. To address acute resource and environmental constraints, the Chinese government launched the ambitious “Dual Carbon” strategy in 2021, targeting a carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 206011. Given the shared sources of PAHs and carbon dioxide, this unprecedented energy system transformation is destined to reshape the future of PAH emissions12. It presents a unique policy laboratory to investigate not just whether toxicity emissions will decline, but how this transition will unfold across the nation’s diverse landscape.

However, critical research gaps persist at this pivotal intersection of toxicity assessment and carbon neutrality. First, while the “Dual Carbon” strategy may drive a national decline in EBaPeq, its impact on regional inequality remains entirely unexplored. China’s vast territory encompasses regions with starkly different industrial structures and energy dependencies (e.g., coal-intensive north vs. more diversified south)13,14,15,16. A national-level analysis could mask significant and unfair disparities, potentially leaving some provinces to shoulder a disproportionate burden of toxicity reduction amidst economic development pressures—a direct contradiction to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)17. Second, existing studies lack a forward-looking, high-resolution framework capable of projecting the complex, non-linear dynamics of EBaPeq under the “Dual Carbon” pathway.

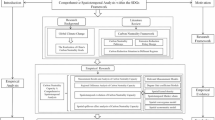

Therefore, this study is designed to project the spatiotemporal trajectory of China’s PAH toxicity emissions under the “Dual Carbon” strategy, with a specific focus on uncovering and diagnosing regional inequalities. Leveraging long-term provincial energy data (2000–2023) and machine learning techniques, we project provincial EBaPeq from 2024 to 2060. We then employ inequality decomposition analysis to scrutinize the EBaPeq intensity (EIBaPeq, defined as EBaPeq per unit GDP) across regions. Our research is guided by three specific questions: (1) When will China’s EBaPeq peak under the “Dual Carbon” strategy, and how will this peak manifest spatiotemporally? (2) What are the primary drivers of inequality in EIBaPeq across China? (3) Can the realization of the “Dual Carbon” goals mitigate, or does it risk exacerbating, these regional inequities? By answering these questions, we aim to provide a scientific basis for crafting collaborative, effective, and equitable governance strategies for carbon and toxic pollutants.

Results and discussions

Trends and composition of EBaPeq from 2000 to 2060

Monte Carlo simulation results showed that the uncertainty of the emission inventory exhibited an increasing trend from 2000 to 2007, after which it plateaued (Supplementary Fig. 1). The calculated EBaPeq for China increased significantly from 1371 t-TEQ (95% CI: 1036 ~ 1694 t-TEQ) in 2000 to 2143 t-TEQ (95% CI: 1583 ~ 2905 t-TEQ) in 2007 (Fig. 1a, Kruskal–Wallis H test, p < 0.05), and then plateaued (Fig. 1a, Kruskal–Wallis H test, p > 0.05). For comparison, the PKU-PAH-2007 inventory8, which was derived from EΣPAHs from 69 sources, reported a national EBaPeq of 2401 t-TEQ for China in 2007, with individual values ranging from 4.7 to 1100 t-TEQ (Supplementary Table 2). This study, focusing on 33 major sources for the same year, yielded a comparable estimate of 2143 t-TEQ (95% CI: 1583–2905 t-TEQ), with individual sources ranging from 4.5 to 933 t-TEQ (Supplementary Table 2). The deviation between these estimates was less than 5%, indicating the credibility of our EBaPeq inventory. Provincial-level comparisons further demonstrated close alignment, with relative standard deviations ranging from −29.2% to 7.3% across China’s 30 provinces (Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, a previous study applying comparable methods reported a national EBaPeq of 2111 t-TEQ for China in 2012, with provincial values ranging from 3.4 to 937 t-TEQ18 (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, this study derived a national EBaPeq of 2079 t-TEQ (individual range: 3.7 to 929 t-TEQ; Supplementary Table 2) for the same year. The divergence between these estimates remained within 5%, reinforcing the reliability of the current methodology. A recent study revealed that global EΣPAHs exhibited a modest decline from about 3.67 × 105 t in 2012 to 3.57 × 105 t in 201510. EΣPAHs in developing regions (e.g., China, India and other parts of Asia) exceed those in developed regions, such as the USA, Western Europe, and East Asia, suggesting a higher risk of PAH-related pollution in developing economies10. For example, China had the largest values of emissions with its EΣPAHs decreased from 8.2 × 104 t in 2012 to 7.8 × 104 t in 2015, while experiencing the largest increase (1.7 × 104 deaths) in lung cancer deaths10. Our results show a consistent decline in EΣPAHs from 9.0 × 104 t in 2012 to 8.1 × 104 t in 2015 (Supplementary Table 4); however, the corresponding EBaPeq did not change significantly (Fig. 1a, Kruskal–Wallis H test, p > 0.05). This discrepancy underscores that mass-based emissions alone may not fully reflect toxicological risks. From a global trade perspective, global EΣPAHs were estimated at 2.9 × 105 t in 2014, with the top five emitting regions being China (8.4 × 104 t), India (3.5 × 104 t), Latin America (3.1 × 104 t), Middle East and North Africa (2.7 × 104 t) and Western Europe (1.3 × 104 t)19. Our estimate for China in 2014 (8.5 × 104 t) is consistent with this reported value. Furthermore, an analysis of reported 16 PAH concentrations in surface water and bottom sediments across China from 2000 to 2020 revealed that the temporal trends of total high molecular weight PAH (HPAH) concentrations were consistent with total HPAH emissions, which increased until 2014 and then plateaued20. Given that HPAH emissions account for 91.2% of EBaPeq21, the consistency between ambient HPAH measurements and our EBaPeq trends highlights the importance of prioritizing toxicity-driven assessments alongside traditional emission metrics in international policy-making. A comprehensive comparison of our study’s scope, methodology, key metrics, and findings with previous national and global studies is provided in Supplementary Table 5, underscoring the contributions of our work.

a National EBaPeq from 2000 to 2023 (calculated via emission factor method) and projected under the Business-As-Usual (BAU) scenario (2024–2060). b National EBaPeq projected under the Dual Carbon (DC) scenario (2024–2060). Both projections from 2024 onwards were generated using the established XGBoost method.

A quantitative model for EBaPeq across 30 provinces in China from 2000 to 2023 was established using the XGBoost algorithm, incorporating twelve predictor variables. The R2 of EBaPeq with their predictors were 0.96 (Fig. 2a) and 0.98 (Fig. 2b) in training and testing dataset, respectively. Moreover, the RMSE between calculated EBaPeq (EBaPeq(cal)) with their observed values (EBaPeq(obs)) in training and testing dataset were 7.8 t-TEQ (Fig. 2a) and 5.2 t-TEQ (Fig. 2b), respectively. The high values of R2, as well as the low RMSE values indicate the excellent performance of the model in predicting EBaPeq. Using this model, yearly EBaPeq from 2024 to 2060 of China were projected. Under the BAU scenario, national EBaPeq is estimated to increase from 2107 t-TEQ in 2024 to 2584 t-TEQ in 2060 (Fig. 1a), driven by growing fossil fuel consumption without significant structural changes in the energy sector (Fig. 1a). This aligns with the International Energy Agency’s 2018 forecast, which suggested that fossil fuels would remain the primary energy source even under a sustainable development scenario by 204022. In contrast, EBaPeq from coal consumption in industry is projected to decrease (Fig. 1a), reflecting the national “Zero-growth Action Plan” for the modern coal chemical industry and improved emission control measures16. Similarly, EBaPeq from residential coal consumption also declined (Fig. 1a), owing to the implementation of clean heating reform in rural areas23. The primary driver of the overall increase in EBaPeq is the rising coal consumption for energy production (Fig. 1a), necessary to meet the growing total and per capita electricity demand24.

Point-to-point comparison of calculated (EBaPeq(cal)) and reference (EBaPeq(obs)) values for the a training dataset (N = 504) and b testing dataset (N = 216). The dashed line in each panel represents the reference line (y = x). The coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE) are provided for each dataset.

In contrast, the DC scenario, which assumes an optimized energy consumption structure with a greater proportion of non-fossil fuels to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, projects that EBaPeq will peak in 2027 at 2433 t-TEQ (Fig. 1b) and then decline by 45.2% to 1334 t-TEQ by 2060 (Fig. 1b). Compared to the BAU scenario, EBaPeq related to coal and oil consumption in the DC scenario is projected to increase by 7.7 ± 0.6% and 9.6 ± 2.2% in 2030, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2), while EBaPeq from biomass burning decreases by 47.1 ± 9.8% (Supplementary Fig. 2). Coal consumption for energy production, coke production, and aluminum (Al) production are the three major contributors to EBaPeq (Fig. 1b), even though their combined emissions are projected to decrease by 42.6 ± 9.8% under this scenario (Supplementary Fig. 2). China is the world’s largest producer of Al, accounting for about 60% of global output in 202325,26. Furthermore, with global Al consumption predicted to rise by approximately 80% by 205027, managing emissions from this sector is crucial. The process of Al production is highly electricity-intensive, requiring between 13,000 and 18,000 kilowatt-hours per ton of aluminum produced28. Therefore, achieving deep emission reductions of BaPeq from coal consumed in energy production, coke production, and Al production represents a major future challenge. A feature importance analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3) confirmed that coal consumption, coke production, and Al production are the strongest predictors of historical EBaPeq trends. This finding quantitatively supports the subsequent analysis of regional drivers, particularly the pronounced impact of energy- and industry-intensive activities in Northern China.

Temporal and spatial variation in EBaPeq

Climatic conditions, economic development levels, and population sizes vary greatly across China’s regions. Based on the comprehensive regionalization of China29, the country is divided into seven geographical regions (Supplementary Fig. 4). EBaPeq in South China and Southwest China peaked in 2005 and 2006 at 261 t-TEQ and 353 t-TEQ, respectively (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5a), while East China and Central China peaked later, in 2011, with highest values of 544 t-TEQ and 266 t-TEQ, respectively (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5a). In contrast, EBaPeq in the three northern regions (Northeast, Northwest, and North China) is projected to peak around 2027 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5a), which can be attributed to their heavy reliance on coal for energy production. The relationship between per capita emissions and per capita GDP from 2000 to 2023 in the four southern regions (South China, Southwest China, East China, and Central China) follows the traditional shape of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6), confirming that their EBaPeq has already peaked. For the three northern regions, however, per capita emissions remained positively correlated with per capita GDP (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting they are still in the industrialization stage30. As shown in Table 2, the peak values of per capita emissions and the years in which these peaks occurred differ significantly across the seven regions. The EKC-fitted peak per capita EBaPeq for North China, Northeast China, and Northwest China are 3.85, 2.47, and 4.58 g ca−1, respectively, with peak years projected to occur between 2025 and 2030 (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6). These projections are consistent with the results from the DC scenario based on energy consumption and its structure.

A comparison with the limited number of studies forecasting the peaking of atmospheric pollutants (e.g., PAHs and CO2) in China provides context. For instance, a recent study using multiple linear ridge regression predicted that PAH emissions, if driven solely by energy transition, would peak in 2035 under shared socioeconomic pathways31. Another study by Xu et al., using a decomposition model, indicated that China’s CO₂ emissions would not peak under a business-as-usual scenario but would peak around 2030 under a planned energy structure scenario32. Our model’s prediction of an earlier peak year (around 2027) underscores the accelerated emission reduction effect of the “Dual Carbon” strategy and demonstrates our model’s capability to capture the non-linear impacts of policy interventions. To estimate the potential cancer cases avoided by 2060 due to the EBaPeq reduction (approximately 1250 t-TEQ) driven by the “Dual Carbon” policy, we applied a significant positive relationship between EBaPeq and lung cancer deaths per 100,000 people (ED100000) derived from published research33. Our projections indicate that by 2060, EBaPeq under the DC scenario will be 48.4% lower than under the BAU scenario. This substantial emission reduction corresponds to a 40.0% decrease in ED100000, highlighting significant public health co-benefits. This finding effectively demonstrates that the “Dual Carbon” policy is not merely a climate mitigation action but also a crucial public health intervention.

Before 2011, East China, North China, and Southwest China were the top three contributors to national EBaPeq (Supplementary Fig. 5a), accounting for 26%, 18%, and 15% of the national total, respectively. Subsequently, EBaPeq from Southwest China decreased due to a sharp decline in biomass burning and the rapid adoption of clean energy (e.g., wind, hydro, and solar)34, while emissions from Northwest China increased, making it the third-largest contributor (Supplementary Fig. 5a). From 2000 to 2060, Northwest China, North China, and Northeast China ranked as the top three regions for emission intensity of EBaPeq (EIBaPeq), with geometric means of 41.3, 28.5, and 25.9 t-TEQ per trillion CNY, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Northwest and North China are rich in coal reserves but have relatively lower economic development levels35. For example, Northwest China is an important energy base along the “Silk Road Economic Belt,” with its economy dominated by heavy industries and a consequently high demand for coal consumption36. Furthermore, guided by the “12th Five-Year Plan (FYP) for Coal Industry Development,” China’s coal industry has gradually shifted from the eastern to the western regions37, leading to a decline in EBaPeq in East China but an increase in the Northwest (Fig. 4a–f). Within North China, the provinces of Shanxi (SX) and Inner Mongolia (NM) account for approximately 70% of the region’s total emissions. NM is the second-largest coal-consuming province in China, accounting for 26.2% of the national total in 2024, second only to SX (29.2%)38. As one of the first provinces to participate in the “West-East Power Transmission Project” starting in 2000, NM built numerous coal-fired power facilities during the 10th FYP39. Additionally, the industrial sector in NM is highly dependent on coal-intensive industries such as coal mining, petroleum processing, coking, and heat production and supply, which together account for 92% of its total energy consumption, with coal alone constituting 83%40. Switching from coal-fired to cleaner electricity generation is therefore critical for mitigating emissions, especially in northern regions where wind and solar potentials are abundant but underutilized. East China presents the highest total EBaPeq but the lowest EIBaPeq (Supplementary Fig. 5). This region has a high level of economic development and substantial energy demand, but it possesses relatively few energy reserves, making it heavily reliant on imported energy34. EIBaPeq across all seven regions has shown a general declining trend (Supplementary Fig. 5b), indicating that the rate of economic growth has surpassed the rate of EBaPeq increase. However, this downward trend slowed around 2012 (Supplementary Fig. 5b), coinciding with China’s entry into a new phase of economic development41. In conclusion, the stark north-south divergence in EBaPeq peaking timelines is not coincidental but is fundamentally rooted in the powerful path dependency of regional development models. The northern regions are locked into a socio-technical regime characterized by historically formed, energy-intensive industrial structures and coal-dominated energy systems, creating a formidable structural inertia that impedes a rapid transition.

Spatial distribution of annual BaPeq emissions (t-TEQ) across Chinese provinces for the years a 2005, b 2010, c 2015, d 2020, e 2030, and f 2060. Emissions from 31 sources are aggregated. Data for 2005–2020 are based on the historical inventory, while data for 2030 and 2060 are model projections under the DC scenario.

Inequality decomposition of EIBaPeq

Although the national average EIBaPeq decreased from 2000 to 2020 (Supplementary Fig. 7a–d), its inequality (as measured by the Theil index) increased from 0.09 to 0.23, with the contribution of inter-regional inequality gradually expanding over this period (Fig. 5). Under the BAU scenario, the inequality of EIBaPeq is projected to increase from 2024 to 2060 under low (BAU-L), middle (BAU-M), and high (BAU-H) economic growth rates (Supplementary Table 6), rising by 104%, 84.1%, and 64.0% respectively, compared to the 2023 level (Fig. 5). Under the DC scenario, the trajectory of inequality varies with economic growth. Under the low growth rate (DC-L), EIBaPeq inequality is projected to increase to 0.286 by 2060, though this value is 40% lower than that under the BAU-H scenario (Fig. 5). Under the middle growth rate (DC-M), inequality increases until 2035 (peaking at 0.253) and then plateaus (Fig. 5). Notably, under the high growth rate (DC-H), inequality peaks earlier, at 0.24 in 2030, and then slightly decreases to 0.22 by 2060 (Fig. 5). These results indicate that the DC scenario can suppress the rise in EIBaPeq inequality compared to BAU, but does not lead to a significant decline within the study period.

Temporal trend of the total inequality index (T) for EIBaPeq from 2000 to 2023 (historical period) and projected from 2024 to 2060 under both BAU and DC scenarios across high, middle, and low GDP growth pathways, as well as the contributions of intra-regional inequality (Tw) and inter-regional inequality (Tb) to the inequality in the EIBaPeq.

Decomposing the national EIBaPeq inequality for the seven regions under the DC scenario reveals that Northwest China and North China are the primary contributors (Supplementary Figs. 7e, f and 8a). The inequality stemming from North China is mainly driven by intra-regional disparities (Supplementary Fig. 8b), whereas that from Northwest China is primarily due to inter-regional disparities (Supplementary Fig. 8c). The intra-regional inequality of EIBaPeq in North China originates predominantly from several key sectors: coke production, coal consumption, primary aluminum production (Supplementary Fig. 9). For instance, within North China, Shanxi (SX) contributed the largest share (approximately 60%) of regional EIBaPeq from coking, followed by Inner Mongolia (NM) and Hebei (HE) at 21% and 16%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10a). In contrast, the contributions from Beijing (BJ) and Tianjin (TJ) were minimal, representing only 0.3% and 1.2% of the regional EIBaPeq from coking, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10a). A similar spatial pattern was observed for EIBaPeq from industrial coal use, with NM contributing 53% of the regional total, followed by HE (24%) and SX (17%) (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Again, BJ and TJ showed negligible contributions, accounting for only 0.8% and 5.1%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The inter-regional inequality in EIBaPeq associated with the Northwestern region was primarily attributable to its higher emissions from coking, coal-consuming energy production, and industrial coal use compared to other regions (Supplementary Fig. 11). Furthermore, in Northeast China, the intra-regional disparity in EIBaPeq showed an increasing trend (Supplementary Fig. 8d), largely driven by differences in oil-consuming energy production (Supplementary Fig. 9). Specifically, Heilongjiang contributed 74% of the regional EIBaPeq from this sector, substantially higher than the contributions from Liaoning (15%) and Jilin (11%) (Supplementary Fig. 10c), leading to a widening intra-regional gap over time (Supplementary Fig. 9).

A provincial-level analysis visually synthesizes the core finding of the North-South divide (Supplementary Fig. 12a), clearly highlighting the provinces in Northwest and North China as the primary contributors to national EIBaPeq inequality (Supplementary Fig. 12b). The industrial structure in these regions is dominated by energy-intensive and high-emission heavy industries42,43. For example, aluminum smelting, a representative industry, heavily relies on coal-fired captive power plants for its substantial electricity and heat demands28, making it a significant source of PAH emissions from both coal combustion and industrial processes. Moreover, the energy profile in these regions—being major coal producers and consumers in China—is severely constrained by this resource31,32. Intensive industrial use, coupled with a heavy reliance on coal for winter heating, has deeply entrenched coal in the regional energy structure, creating formidable barriers to emission reduction. In contrast, the southern and central regions (early peakers) have industrial structures more oriented towards light and high-tech industries, as well as services, which inherently have lower energy consumption and emission intensity per unit of output value44. Their energy structure is also more diversified, with a relatively higher penetration of natural gas and hydropower45, allowing them to benefit more readily from the energy transition and achieve an early emissions peak.

Although the national “Dual Carbon” policy is unified, its implementation effectiveness varies locally due to regional disparities. Northern regions face disproportionately high structural transition costs and socio-political barriers. These include the immense economic costs and technical difficulties of retrofitting or phasing out capital-intensive, coal-dependent industrial assets46, as well as major challenges related to employment security and social stability in areas where local economies and fiscal revenues heavily depend on these traditional industries47. Consequently, these factors generate greater political and social resistance to a rapid energy transition, leading to delayed policy effectiveness compared to the structurally more diversified and flexible southern regions47. This analysis provides an important political economy explanation for the delayed peak in the North.

Policy implications

Building upon the core findings of this study—particularly the pronounced North–South divide in EBaPeq peaking timelines and the path-dependent challenges rooted in the industrial and energy structures of Northern China—we propose an integrated policy framework. This framework is designed to address the dual challenges of reducing aggregate emissions and mitigating regional inequality in EIBaPeq, thereby fostering collaborative and equitable carbon-toxic pollutant governance.

Fostering cross-regional synergy through multi-dimensional platforms: to overcome the technological and economic lock-in effects in Northern regions, we recommend upgrading the existing “West-to-East Power Transmission” model into a comprehensive “technology-capital-pollutant emission rights” trading platform. This initiative would establish a cross-regional technology compensation mechanism to incentivize the westward transfer of green technologies (e.g., supercritical water coal gasification for cleaner coal utilization in Northwest energy bases and plasma cracking technology in the coking industry to decompose PAH precursors). Concurrently, implementing stricter toxicity-weighted emission limits for PAHs in traditional industrial-intensive areas and integrating PAH reduction achievements into regional pollutant emission trading pilots would allow high-performing companies to gain tangible benefits, thereby accelerating technological upgrades and emission reductions.

Accelerating regional green transformation via structural optimization: Addressing the structural inertia in the North requires a deep optimization of industrial and energy systems. We advocate for promoting industrial symbiosis and energy substitution tailored to regional characteristics. This includes constructing steel-chemical coupled industrial parks in North China to utilize coke oven gas for hydrogen production, thereby replacing scattered coal burning and reducing carcinogenic PAH generation at the source. In the Northeast, deploying biomass heating and carbon material co-production technology can substitute coal-fired heating with agricultural residue utilization. Furthermore, the Northwest, rich in wind and solar resources, should advance a circular industrial chain for green electricity-based hydrogen production, facilitating a transition away from coal dependence.

Refining market-based incentive mechanisms for multi-pollutant control: To internalize the environmental costs of PAH emissions and create sustained economic incentives, we propose enhancing the ecological compensation accounting system. This involves incorporating toxicity-weighted PAH metrics into the existing carbon emission trading scheme to establish a multi-pollutant collaborative control market. Specific measures include conducting “carbon-PAHs” dual quota pressure tests in Northern steel clusters, where failure to meet PAH reduction targets would trigger carbon quota deductions. To ensure the integrity of this system, we recommend developing isotope fingerprint-machine learning models for accurate PAH source apportionment and deploying online PAH mass spectrometers in key industrial parks for real-time monitoring, with data directly linked to the national trading platform.

Ultimately, a place-based policy differentiation—considering local economic development, industrial structure, and resource endowment—is essential to realize the most cost-effective and equitable low-carbon transition for each region, directly countering the path dependencies identified in our analysis.

Limitations and future research

Regional differences in fuel types, combustion technologies, stove age, and operational practices could cause systematic spatial biases in emission factors. For example, the south of China might use more improved stoves of a certain type, while the North might rely more on traditional stoves23, which could lead our currently used national average emission factors to slightly overestimate or underestimate a particular region. However, such potential regional biases are more likely to strengthen rather than weaken our main conclusion, because the energy-saving equipment transition in the south of China not only reduced fossil fuel consumption but also directly promoted upgrades in combustion technology. Therefore, if more precise region-specific emission factors were available, the actual observed toxic emission reduction effect in the South might be even better than our current estimates, and the inequality gap might be larger. This suggests that our current conclusion might be conservative. In addition, although the absolute values of annual EBaPeq have an uncertainty range (Supplementary Fig. 1), the core spatiotemporal patterns we revealed are highly robust. The inequality of EIBaPeq remained consistently distant from 0 (e.g., the median ratio was 0.23 in 2020 with 95% CI of [0.20, 0.26]). This indicates that the North-South difference is statistically significant and is not altered by reasonable fluctuations in emission factors. Moreover, the observed EBaPeq calculated of China first increased significantly from 2000 to 2007, and then plateaued remained consistent across all simulations.

We acknowledge that, like all predictive models, our approach cannot foresee completely disruptive technological revolutions (e.g., the sudden emergence of a completely zero-PAH-emission process) or extremely drastic policy shifts. However, the primary objective and core conclusions of this study lie in revealing the relative performance and inequality patterns of different regions under a given policy pathway. Our sensitivity analysis and scenario comparison show that the conclusions regarding the North-South divide (i.e., delayed peak in the North, early peak in the South) and emission intensity inequality are highly robust under various assumptions. This is because this regional disparity is determined by deep-seated factors such as industrial structure and resource endowment, which are less sensitive to model uncertainties.

While this study provides an initial estimation of the health co-benefits associated with EBaPeq reduction, it underscores the need for more sophisticated health impact assessments in future work. A promising research direction involves the development of a dynamic, integrated assessment framework that explicitly couples our emission projections with regionalized intake fraction models, time-variant population data (accounting for aging and migration), and disease-specific exposure-response functions. Such a model could quantify the avoided incidence of PAH-related diseases (e.g., lung cancer) under different policy scenarios, dynamically track the evolution of health benefits over time, and monetize the economic value of averted mortality and morbidity. This would provide a more granular, powerful, and policy-relevant evidence base for evaluating the full societal return on investment in carbon-neutrality and clean air policies.

Conclusions

Quantitative assessment of the reduction effect of EBaPeq by implementing the dual carbon strategy of China should be a key focus of scientists and policy-makers, as such reduction is both crucial for achieving the goal of synergistic pollution reduction and carbon mitigation, as well as an inherent requirement for advancing the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Future provincial energy consumption amounts are essential for predicting EBaPeq, which have never been explored. Therefore, in this study, energy consumption amounts from 2024 to 2060 under both baseline and dual carbon scenarios were explored using trend extrapolation and balance equation methods on long-term time series (2000–2023) datasets. Subsequently, a quantitative prediction method between multiple variables and EBaPeq was constructed using machine learning method. It was revealed that the implementation of “dual carbon” strategy will lead to EBaPeq of China peaking around 2027, at approximately 2433 t-TEQ, and then it had significantly declined by 45.2% to 1334 t-TEQ in 2060, while inequality of EIBaPeq will not significantly decrease under high and middle economic growth scenarios in the future, but instead will increased by 14.5% under low economic growth scenario. The national inequality of EIBaPeq mainly originates from the Northwest and North China, where have large amounts of Al production and coal consumed in energy production, resulting in EBaPeq in these regions will peak around 2027. However, for South and Central of China, EBaPeq have peaked before 2012 fitted using the EKC modeling. Therefore, recommendations including establishing cross-regional technology compensation mechanisms, designing differentiated emission reduction pathways, and improving ecological compensation accounting systems were proposed to promote regional collaboration for equitable pollution reduction and carbon mitigation.

Materials and methods

Data sources and processing

Calculation of provincial EBaPeq: sixteen USEPA PAHs (Supplementary Table 1) from thirty-three emission sources (Supplementary Table 7) related four energy sections (i.e., coal consumption, oil consumption, iron-steel industry, and biomass burning), which accounting for more than 95% of all source contributions, were considered7,8. Natural sources were not considered in this study because of their extremely low proportion in China23,48. Provincial EBaPeq were calculated using Eq. 1 shown below. Due to the lack of activity data, EBaPeq in Xizang, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan of China were not calculated.

where the parameter EF (g t−1) is the emission factor of PAHs congener i (Supplementary Table 8). j is the PAH emission sources showed in Supplementary Table 7. k is the PAH sub-sources presented in Supplementary Table 9. X is the fraction of the activity rate contributed by a given source j, which was calculated using the technology split method (Supplementary Note 1). Activity data (A, 104 t a−1), i.e., the amount of energy consumption and iron-steel production in source j, from China, were obtained directly from China Energy Statistical Yearbook (2000–2023)38 and China Industry Statistical Yearbook (2000–2023)40, edited by National Bureau of Statistics. The amount of combusted biomass is not available in statistical yearbooks after 2007 and thus was estimated in Supplementary Note 2. FL and CF in Eq. 1 represent biomass fuel loading and combustion efficiency. Biomass fuel loading in province p were obtained from references49,50,51. The combustion efficiency of outdoor wheat, rice, and corn straw is 0.95, 0.95, and 0.85, respectively, while the combustion efficiency of needle-leaf forest, broad-leaf forest, and other forest is 0.2549.

Quality control of emission factor data sources: EFs of PAH congener in Table S3 were obtained from the database of PKU-PAH. According to PKU-PAH, a total of 5822 reported EFs, which were all based on actual measurements, were compiled from a large number of published literature4,52, and databases (e.g., EDGAR, PKU-FUEL). During data screening, studies explicitly described experimental conditions (e.g., stove type, combustion efficiency, sampling methods) were involved to ensure data representativeness and reliability. For cases where multiple measured values existed for the same fuel-technology combination, weighted averaging method was used to obtain more representative EF values. Geometric standard deviations of EFs for various sources were presented in Supplementary Table 10.

Scenario definition and projection

“Business As Usual (BAU)” scenario: a baseline (i.e., “Business As Usual (BAU)”) scenario was established, which hypothesize the absence of strong “Dual Carbon” policy interventions. It assumed that the provincial fossil fuel production and consumption amounts (Supplementary Data 1), as well as its structural changes from 2024 to 2060 will follow the trend from 2013 to 2020, as China has entered a new normal stage of economic development since 2012 and the Chinese government issued the dual carbon strategy implementation plan in 202111,53. Under the BAU scenario, the predicted total fossil fuel consumption amounts of 30 provinces will continue to grow (Supplementary Fig. 13a), which will reach 5.6 billion and 6.5 billion tons (in terms of standard coal) in 2030 and 2060, respectively. According to the “Energy production and consumption revolution strategy (2016–2030)” issued in 2016, energy consumption amount in 2030 of China is not to exceed 6 billion tons (in terms of standard coal), and up to 2050, it is expected to remain stable54. The simulation of energy consumption amount under the BAU scenario closely aligns with the set targets in the “Energy production and consumption revolution strategy (2016–2030)”54, supporting the credibility of the simulation results.

“Dual Carbon (DC)” scenario: Its construction was anchored in provincial targets for the non-fossil energy consumption share by 2030 (Table 1). For projections beyond 2030 and up to 2060—a year for which specific provincial targets are absent—we applied the national-level goal of ≥80% non-fossil energy share to all provinces. Historical energy consumption data for 31 sources across 30 provinces (2018–2023) from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook38 served as the basis for projecting future energy demand under a DC trajectory (Supplementary Fig. 13b).

To align the DC projection with the BAU pathway, we implemented a calculation framework that reallocates future energy consumption from fossil fuels to meet the non-fossil targets12. The projected consumption of coal and petroleum under the DC scenario was adjusted downwards (Supplementary Data 2). The energy consumption attributable to coal-combustion sources (sources (1)–(14) and (20)–(24) in Supplementary Table 7) for a province p under the DC scenario, denoted as Ap, j1(DC), was derived using Eq. 2. This calculation ensures the aggregated energy mix complies with the mandated non-fossil ratio (Rp, non-fossil).

An analogous calculation (Eq. 3) was performed to adjust the energy consumption from petroleum-related sources (sources (15)–(19) in Supplementary Table 7), yielding Ap, j2(DC). Full names and short interpretations of abbreviations involved in Eq. 2 and Eq. 3 were presented in Supplementary Table 11.

Furthermore, consistent with policies promoting clean energy transition, we projected that the use of straw and firewood for energy would be phased out, reaching zero consumption after 203052.

XGBoost model configuration and validation

A non-parametric supervised learning technique known as XGBoost55,56,57 was employed to establish quantitative relationships of EBaPeq in 30 provinces of China from 2000 to 2023 with twelve predictor variables (i.e., coal consumption, coke production, crude oil consumption, gasoline consumption, diesel consumption, fuel oil consumption, iron production, crude steel production, Al production, straw, firewood, and population). These variables are not static indicators. Their changes inherently directly reflect the transitions in energy structure, industrial activity, and changes in technological efficiency. For example, a decline in coal consumption directly manifests the transition of the energy structure from coal to cleaner energy sources. Changes in gasoline/diesel consumption reflect the electrification process and technological advancements in the transportation sector. The slowing growth or even decline in steel/iron production reflects industrial structure upgrading and energy efficiency improvements driven by policies in the industrial sector. The XGBoost model, trained on historical data from 2000 to 2023, has learned the complex, non-linear relationships between these driving variables and EBaPeq. This historical period encompasses China’s “Energy Conservation and Emissions Reduction” efforts58, the “Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan”59, and the incubation and progression of the “Dual Carbon” strategy60. Consequently, the patterns learned by the model inherently incorporate the cumulative effects of policy interventions and technological progress over the past two decades. Future predictions are based on the presumed future pathways of these driving variables under the “Dual Carbon” agenda, which essentially extends the historically driven patterns into the future.

Feature importance analysis was performed using the native xgb.importance function within the XGBoost framework (Supplementary Note 3). This analysis, based on the “gain” metric (i.e., the average training accuracy improvement brought by a feature when it is used in trees), quantitatively ranks the contribution of each predictor variable to the model’s predictions. To evaluate the generalization performance and robustness of the XGBoost model on historical data (2000–2023) and to guard against over-fitting, we employed k-fold cross-validation (with k = 10)61. Model performance was quantified using Coefficient of determination (R2) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). The model was trained to optimal performance with the following key parameters: a learning rate of 0.05, a maximum tree depth of 5, and L2 regularization (lambda = 0)56. A complete list of all hyper-parameters and their justification is provided in Supplementary Table 12. XGBoost was run in the Caret packages in R software56. Finally, provincial EBaPeq under BAU and DC scenario were predicted using the developed model.

Environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) model

Based on the theory of Kuznets curve, the long-term trends between the observed EBaPeq and GDP trajectories for seven regions through 2000–2023 were estimated by fitting a EKC model (Eq. 4), which assumes that per capita EBaPeq should increase with per capita GDP to reach the peaks and then decline30,62.

where Ep and Gp represent the observed annual per capita EBaPeq and per capita GDP, respectively. Parameter a relates to the height of the function, corresponding to the measure of peak per capita EBaPeq. Parameter b controls the position of the function along the horizontal axis, which is the per capita GDP corresponding to the peak per capita EBaPeq. Parameter c governs the shape of the function. Ep and Gp were fitted to Eq. 4 for the seven regions using the function of “nlsLM()” from the package “minpack.lm” in R (version 3.5.3)30. The “nlsLM()” is developed to modify the original nonlinear least-squares regression with the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm30. As shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6, per capita EBaPeq are significantly correlated with and follow a bell shaped relationship with per capita GDP for each region.

The inequality of EIBaPeq

The Theil index and its decomposition method can measure the contribution of inter-regional differences and intra-regional differences to the changes in overall regional disparity, which is widely used to calculate inequality63,64. The Theil index (T) ranges from 0 to 1, with smaller values indicating smaller regional differences and larger values indicating larger regional differences. The formula for the T (Eq. 5), as well as the intra-regional inequality (Tw, Eq. 6) and the inter-regional inequality (Tb, Eq. 7) can be expressed as follows:

where EnBaPeq and EmBaPeq is EBaPeq in n province and m region, respectively. EmnBaPeq and Gmn refers to EBaPeq and GDP of n province within m region. Gm denotes GDP of m region. GDP in year t was adjusted as the constant price in 2000. Provincial and national GDP derived from China Statistical Yearbook (2000–2024)65. According to the “China Energy Outlook 2018”66, three scenarios of low, middle, and high growth rates of future GDP in China were set (Supplementary Table 6). The inequality in the EBaPeq among provinces within each region from 2000 to 2060 was calculated.

Uncertainty analysis of EBaPeq

The overall uncertainty of the provincial PAH emission inventory was quantified using a Monte Carlo simulation framework, a well-established approach for propagating uncertainties in emission inventories8,48,67. This probabilistic method repeatedly calculates the inventory output by randomly sampling input parameters from their predefined probability distributions, thereby constructing a probability distribution of the results68,69. Key uncertainty sources include activity data and emission factors. Activity data uncertainties for coal consumption, oil consumption, and the iron-steel industry—sectors with highly reliable statistical data—were assigned a uniform distribution with a variation of ±5%4,6. In contrast, a larger uncertainty range of ±15% was applied to biomass burning sectors due to their more variable data sources49. Emission factors were modeled following a lognormal distribution6,70, characterized by the probability density function:

where x denotes the emission factor value, μ its logarithmic mean, σ the logarithmic standard deviation (provided in Supplementary Table 10), and f the probability of x. The uncertainty of EBaPeq in each sector from 2000 to 2023 was evaluated by performing 10,000 simulation runs, during which EF values were randomly sampled from their distributions to recalculate the national EBaPeq. This study uses the number of values falling outside the 95% confidence interval (CI) to represent the uncertainty.

Data availability

The sources of data are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2. Supporting information (including PAH emission inventory, the proportions of long-term coal/petroleum consumption tables, future GDP growth scenario of China, and XGBoost hyperparameter configuration and description) is available at https://zenodo.org/records/17519430.

Code availability

The XGBoost model source code used in this study is available at: https://zenodo.org/records/17519430.

References

Khanna, N. et al. An assessment of China’s methane mitigation potential and costs and uncertainties through 2060. Nat. Commun. 15, 9694 (2024).

Li, R. et al. Synergistic reduction in air pollutants and health benefits under China’s dual-carbon policy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 9467–9470 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Substantial differences in source contributions to carbon emissions and health damage necessitate balanced synergistic control plans in China. Nat. Commun. 15, 5880 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Tao, S., Cao, J. & Coveney, R. M. Emission of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in China by county. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 683–687 (2007).

Zhang, Y., Tao, S., Shen, H. & Ma, J. Inhalation exposure to ambient polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lung cancer risk of Chinese population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21063–21067 (2009).

Li, B. et al. New method for improving spatial allocation accuracy of industrial energy consumption and implications for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4326–4334 (2019).

Li, B. et al. An improved gridded polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emission inventory for the lower reaches of the Yangtze River Delta region from 2001 to 2015 using satellite data. J. Hazard. Mater. 360, 329–339 (2018).

Shen, H. et al. Global atmospheric emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from 1960 to 2008 and future predictions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6415–6424 (2013).

Onjia, A. Concentration unit mistakes in health risk assessment of PAHs in soil, sediment, and indoor/road dust. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1370397 (2024).

Li, R. F., Zhang, J. & Krebs, P. Global trade drives transboundary transfer of the health impacts of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 170 (2022).

State Council of China (SCC). Opinions on completely, accurately and comprehensively implementing the new development concept and doing a good job of carbon peak and carbon neutralization. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/24/content_5644613.htm (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Effects of Chinese “dual carbon strategy” on soil polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons pollution. Environ. Int. 188, 108741 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Exploring the relationship between urbanization, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in different provinces of China. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 54, 1563–1579 (2016).

Peters, G. P. et al. China’s growing CO2 emissions: a race between increasing consumption and efficiency gains. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 5939–5944 (2007).

Zhao, H. et al. Heterogeneities in regional air pollutant emission mitigation across China during 2012–2020. Earth’s. Future 12, e2023EF004139 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Health effects of banning beehive coke ovens and implementation of the ban in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2693–2698 (2018).

Xu, X. et al. Inequality in agricultural greenhouse gas emissions intensity has risen in rural China from 1993 to 2020. Nat. Food 5, 916–928 (2024).

Mu, X. L. An emission inventory of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in China. Ph.D. Dissertation. (China University of Petroleum, Beijing, China, 2016).

Guo, L. et al. Global trade-driven transfer of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions and associated human inhalation exposure risk. J. Environ. Manag. 355, 120438 (2024).

Wang, W. W. et al. Current and future trends of low and high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface water and sediments of China: insights from their long-term relationships between concentrations and emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3397–3406 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Comparison of PAH mass emissions and their toxicity-weighted trends in China, 2000-2022. Sci. Total Environ. 981, 179562 (2025).

IEA. World Energy Outlook 2018 (International Energy Agency, 2018).

Tao, S. et al. Quantifying the rural residential energy transition in China from 1992 to 2012 through a representative national survey. Nat. Energy 3, 567–573 (2018).

Su, B. & Ang, B. W. Structural decomposition analysis applied to energy and emissions: Frameworks for monthly data. Energy Econ. 126, 106977 (2023).

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBSC). Aluminum Yearbook (2023) (Fangzhi Publishing Press, 2024).

International Aluminium Institute. Primary aluminium production in https://international-aluminium.org/ (2023).

Wang, J., Li, J. & Zhang, J. Analysis of aluminum resource supply and demand situation in China from a global perspective. China Min. Mag. 33, 54–62 (2024).

Wang, X. & Xu, L. Current situation and trend analysis of carbon emission in the electrolytic aluminum industry. Energy Sav. Nonferrous Metall. 38, 1–6 (2022).

Wang, M., Wang, W. & Wu, L. Application of a new grey multivariate forecasting model in the forecasting of energy consumption in 7 regions of China. Energy 243, 123024 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. China’s CO2 peak before 2030 implied from characteristics and growth of cities. Nat. Sustain. 2, 748–754 (2019).

Cao, X. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in China: will decoupling of their emissions and socioeconomic growth emerge? Earth’s. Future 10, e2021EF002360 (2022).

Xu, G., Schwarz, P. & Yang, H. Adjusting energy consumption structure to achieve China’s CO2 emissions peak. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 122, 109737 (2020).

Motorykin, O. et al. Association of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions and smoking with lung cancer mortality rates on a global scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 3410–3416 (2013).

Li, M., Liu, X. & Yang, M. Analyzing the regional inequality of renewable energy consumption and its driving factors: evidence from China. Renew. Energy 223, 120043 (2024).

Wu, H., Hao, Y. & Weng, J. How does energy consumption affect China’s urbanization? New evidence from dynamic threshold panel models. Energy Policy 127, 24–38 (2019).

Guan, D. et al. Structural decline in China’s CO2 emissions through transitions in industry and energy systems. Nat. Geosci. 11, 551–555 (2018).

Chai, J., Wu, H. & Hao, Y. Planned economic growth and controlled energy demand: How do regional growth targets affect energy consumption in China? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 185, 122068 (2022).

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBSC). China Energy Statistical Yearbook (2000–2023) (China Statistics Press, 2024).

Oberschelp, C., Pfister, S., Raptis, C. E. & Hellweg, S. Global emission hotspots of coal power generation. Nat. Sustain. 2, 113–121 (2019).

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBSC). China Industry Statistical Yearbook (2000–2023) (China Statistics Press, 2024).

Wang, J., Zhang, S. & Zhang, Q. The relationship of renewable energy consumption to financial development and economic growth in China. Renew. Energy 170, 897–904 (2021).

Huang, H. The future of carbon-neutrality science and technology from an industrial transformation perspective: an interview with Hou-Liang Dai. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwac295 (2023).

Yang, W. et al. Prediction and scenario simulation of carbon emissions peak of resource-based urban agglomeration with industrial clusters—Case of Hubaoe urban agglomeration Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Energies 17, 5521 (2024).

Wang, J., Xia, L. & Wang, R. Provincial emission inventory of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in China. Atmos. Environ. 334, 120729 (2024).

Carter, E. et al. Household transitions to clean energy in a multiprovincial cohort study in China. Nat. Sustain. 3, 42–50 (2020).

Zhang, W., Chen, C. & Li, M. Impacts of electricity market reforms: from the perspective of economic-energy-environment system synergies. J. Clean. Prod. 509, 145603 (2025).

Su, R. et al. Scaling up green hydrogen in China: economic opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 131, 60–69 (2025).

Wang, W. et al. Current and future trends of low and high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface water and sediments of China: insights from their long-term relationships between concentrations and emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3397–3406 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. A comprehensive biomass burning emission inventory with high spatial and temporal resolution in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 2839 (2017).

Peng, L., Zhang, Q. & He, K. Emission inventory of atmospheric pollutants from open burning of crop residues in China based on a national questionnaire. Res. Environ. Sci. 29, 1109–1118 (2016).

Fang, J. Y., Liu, G. H. & Xu, S. L. Biomass and net production of Forest vegetation in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 16, 497–508 (1996).

Zhang, Y. X. & Tao, S. Global atmospheric emission inventory of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) for 2004. Atmos. Environ. 43, 812–819 (2009).

State Council of China (SCC). Action Plan for Carbon Peak by 2030. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-10/26/content_5644984.htm (2021).

The National Development and Reform Commission and the National Energy Administration. Energy Production and Consumption Revolution Strategy (2016-2030). https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-04/25/content_5230568.htm.

Liu, Z. et al. Interaction patterns between climate action and air cleaning in China: a two-way evaluation based on an ensemble learning approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9291–9301 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Drivers distinguishing of PAHs heterogeneity in surface soil of China using deep learning coupled with geo-statistical approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 468, 133840 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Global Distribution of mercury in foliage predicted by machine learning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 15629–15637 (2024).

The People’s Republic of China. The Eleventh Five-Year Plan. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2006/content_268766.htm (2006).

State Council of China (SCC). Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2013/content_2496394.htm (2013).

The People’s Republic of China. Implement the Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality Goals and Build a Beautiful China. https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202404/content_6948005.htm (2020).

Teng, H. F. et al. Drivers of water erosion-induced lateral soil carbon loss on the Tibetan Plateau. CATENA 211, 105970 (2022).

Li, T., Wang, Y. & Zhao, D. Environmental Kuznets curve in China: new evidence from dynamic panel analysis. Energy Policy 91, 138–147 (2016).

Luo, G., Baležentis, T. & Zeng, S. Per capita CO2 emission inequality of China’s urban and rural residential energy consumption: a Kaya-Theil decomposition. J. Environ. Manag. 331, 117265 (2023).

Yang, T., Zhou, K. & Zhang, C. Spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors of green development efficiency in China’s urban agglomerations. Sust. Cities Soc. 85, 104069 (2022).

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBSC). China Statistical Yearbook (2000−2023) (China Statistics Press, 2024).

Wei, Y. et al. China Energy Report (2018): research on green transformation of energy-intensive sectors (Science Press, 2018).

Inomata, Y. et al. Emission and atmospheric transport of particulate PAHs in Northeast Asia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 4941–4949 (2012).

van Donkelaar, A. et al. Monthly global estimates of fine particulate matter and their uncertainty. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15287–15300 (2021).

Uz, M. et al. High-resolution temporal gravity field data products: Monthly mass grids and spherical harmonics from 1994 to 2021. Sci. Data 11, 71 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions during 2013−2017 in mainland China. Sci. Total Environ. 789, 148003 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42307002); the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M771274); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFC3712004) and the Major Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22494680, 22494681).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weiwei Wang: Writing-original draft, Methodology, Data analysis, Software, Conceptualization. Lu Chen: Writing-original draft, Data collection. Zhen Song: Data collection and analysis, Software. Mengti Wang: Data collection and analysis. Xiaozeng Miao: Writing original draft, Software. Wenhao Wu: Software, Methodology. Zhou Shi: Writing -review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Daohui Lin: Writing-review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Kun Yang: Writing review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Pallav Purohit and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Chen, L., Song, Z. et al. China’s carbon neutrality agenda unmasks a persistent north-south divide in toxic pollutant reduction. Commun Earth Environ 7, 66 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03084-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03084-5