Abstract

Global shipping fuel sulphur content regulations introduced in 2020 reduced the radiative cooling effects of sulfate aerosol over the ocean. Here we use the WRF-Chem model to estimate the effect these regulations have had on aerosols, clouds and solar radiation at the Great Barrier Reef, where climate change is increasing the frequency of mass coral bleaching events. During February 2022, the build-up to a La Niña mass coral bleaching event, we find 11 Wm−2 extra daytime downwards shortwave radiation reaches the reef post-sulfate regulation, compared to the control pre-regulation scenario. The enhancement is dominated by clear-sky-only forcing changes and less severe in cloudier and windier periods. Persistent incoming shortwave radiation enhancements on the order of 5-11 Wm−2 likely lead to sea-surface temperature increases of 0.05-0.15 °C, implying that during bleaching-conducive conditions, 5-10% additional thermal stress is felt by GBR corals now than before the regulation of ship sulfate emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is under severe threat from climate change1,2,3. As ocean temperatures increase, coral bleaching events are becoming increasingly frequent, with mass bleaching events occurring in 1998, 2002, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2022 and 20244. Coral bleaching occurs as the symbiotic relationship between corals and their algal symbiont organisms breaks down under thermal stress, leaving the coral exposed and at high mortality risk2. While rising ocean temperatures are understood to be the primary cause of mass coral bleaching, enhanced solar radiation has also been associated with GBR bleaching events5,6,7 and research suggests the severity of bleaching events can be mitigated by natural or artificial shade8,9,10. The opportunity of shading reefs has led scientists to propose marine cloud brightening (MCB) on the GBR, which utilises aerosols and aerosol–cloud interactions to reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching the ocean surface11,12,13,14.

Simultaneously, an unintentional geoengineering effect has occurred over the world’s oceans, including the GBR, with ship aerosol and gaseous emissions perturbing the local radiation balance. Primary and secondary sulfate aerosol from ships interacts with radiation directly, as well as indirectly by acting as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN)15. Extra CCN alters cloud properties by dividing the available cloud water among more droplets, decreasing the size of the cloud droplets and thereby enhancing cloud albedo, cloud lifetime, and optical depth16,17. Ship-polluted clouds can also exhibit liquid water path increases, which also enhances cloud albedo18. This effect has been observed in satellite images of ship tracks, with marine cloud cover and albedo enhanced above regions of high ship traffic16,19. Recent research also shows a substantial radiative forcing effect due to liquid water path enhancements within marine clouds, even when ship tracks are not visible in satellite images18.

Australia relies on the maritime industry for more than 99% of its imports and exports by volume, and shipping is expected to constitute a large portion of the country’s transport sector into the future20. Ships in the GBR region cause a deterioration in air quality in and around Queensland port cities and coastal regions21,22 as well as other parts of Australia23, Europe24,25,26, Asia27,28,29, and the Americas30,31,32. Primary emissions from the shipping industry include sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO) as well as sulfate (\({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\)), black (BC) and organic carbon (OC) aerosol as depicted in Fig. 1. Ships also emit greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O)33 as well as perturbing tropospheric ozone (O3) and CH4 by emission of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx ≡ NO + NO2)34,35. The overall radiative impact has been modelled on global15,36 and regional37,38 scales, with Partanen et al. (2013) determining that the effective radiative forcing from shipping aerosol emissions in 2010 was −0.39 W m−2 39.

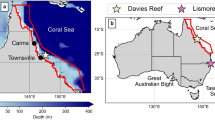

a Map of the WRF-Chem simulation domain over north-eastern Australia and the Coral Sea, showing total NOx emissions from shipping, post-FSC05 regulation, during the 18–28 February 2022 simulation period. Yellow markers show major Queensland cities: Cairns (pentagon), Townsville (triangle), Gladstone (diamond), and Brisbane (circle). The extent of the GBR World Heritage Area is indicated by the shaded red region. b The proportion, by mass, of all pollutants emitted by ships during the simulation period, in the pre-FSC05 scenario. c Same as b but for the post-FSC05 scenario.

With the strengthening of global ship fuel-sulfur content (FSC) regulations in 2020, some of the flow-on effects of ship-emitted aerosols on the short-wave radiation term of the ocean heat budget have been reduced. These regulations, welcomed for their health benefits in reducing local air pollution40, reduced allowable sulfur content from 3.5% to 0.5% (FSC05)41. Recent research has suggested that the ensuing reduction in \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol load over the oceans has resulted in a net increase in radiative forcing relative to pre-2020 conditions42,43,44. Some studies suggest that this may explain a major proportion of recent global warming acceleration trends45,46, while other recent work found that surface temperature changes due to ship emission regulations may only be significant in some small oceanic regions47. Findings regarding enhanced warming due to ship emission changes align with recent research focusing on aerosol ‘demasking’ of Greenhouse gas warming over land and the risks posed to vulnerable communities44,48 and highlight the importance of balancing air pollution mitigation and energy transition policies with rapid reductions in greenhouse gases.

Here, we quantify for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, the role of shipping emissions in reducing incoming solar radiation to the GBR and examine the impact of the 2020 FSC05 regulations on coral bleaching potential.

Results and discussion

Ship emissions

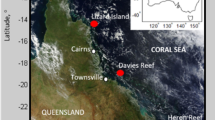

We examine ship-mediated aerosol–cloud-radiation interactions over the GBR by implementing a state-of-the-science ship emissions inventory (STEAM, the Ship Traffic Emissions Assessment Model version 249,50,51) in the Weather Research and Forecasting model coupled to chemistry (WRF–Chem,52), see the “Methods” section). Figure 1a shows how the ship emissions are distributed spatially in the simulation domain. The spatial pattern of emissions seen for NOx holds for all emitted species: emissions are concentrated in the southern part of the domain, emanating from the major port of Brisbane. A major shipping lane is evident roughly following the 153° longitude line northwards from the coast, outside the GBR, taking considerable import and export traffic to and from Australia’s largest cities on the east coast. Smaller emission hotspots are evident in and around the GBR, especially near the ports of Cairns, Townsville and Gladstone.

Figure 1b shows the proportions, by mass, of pollutants in the pre-FSC05 inventory. This is the sum of all emissions from 18 to 28 February 2022, the initial simulation period, with NOx and sulfur dioxide (SO2) being the dominant pollutants. The mass of emitted NOx, VOCs, CH4 and carbon monoxide (CO) is unchanged post-FSC05 (Fig. 1c), with reductions of −79% for SO2, −76% for \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol, −45% for organic carbon (OC) aerosol and −57% for black carbon (BC) aerosol. This comparison highlights the dramatic reduction in \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) and the relative increase of NOx dominance, post-FSC05 regulation. STEAM assumes that the change in fuel grade to low fuel sulfur content is accompanied by reductions in BC and OC emissions following the emission factors in Grigoriadis et al. (2021)53. We chose three simulation periods with varying prevailing meteorology, as discussed below, and for each simulated three ship emission scenarios. (A) “post-FSC05”, which is the contemporary ship emission scenario after sulfate content regulation; (B) “pre-FSC05”, which is a counterfactual scenario with ship emissions as they would have been prior to the fuel sulfate regulation; and (C) “NoShips”, which is a second retrospective scenario with ship emissions removed from the emission fields, allowing us to diagnose the absolute impact of ship pollutants on atmospheric chemistry and radiation at the GBR.

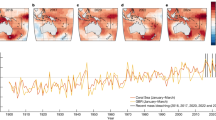

Meteorology during the simulation periods

We explored three simulation periods with contrasting weather conditions and coral bleaching outcomes. We first simulate the period 18–28 February 2022 because this was in the lead-up to the 2022 mass coral bleaching event. Surface meteorological conditions are shown for Davies Reef in the central GBR in Fig. 2, with <7% normalised mean bias (NMB) for the model compared to observations. Figure 2a shows that 18–28 February 2022 was characterised by moderate south-easterly trade winds between 18 and 24 February, before winds slackened and turned northerly on 25 February. During the period of light northerly winds, doldrum-like conditions were set up, and air temperatures increased to over 29 °C at Davies Reef. This was associated with strong downwards shortwave solar radiation flux, well above the 1997–2022 mean for this time of year, contributing to enhanced sea surface temperatures and conditions conducive to the mass bleaching event54. This event was notable for being the mass coral bleaching event to occur at the GBR during La Niña conditions54,55 with 91% of coral reefs surveyed by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) suffering damage56. Additional model evaluation is shown in Figs. S2 and S3 in the Supplementary Information.

The periods are: a 18–28 February 2022, b 3–14 February 2023, c 18–28 February 2023. Each panel shows (top to bottom) air pressure, air temperature, wind direction and wind speed. Surface observations from the Australian Institute of Marine Science weather station are in blue, WRF-Chem surface modelled values are in red.

The second simulation period is a year later, 3–14 February 2023. We choose this period as meteorological conditions are similar to 18–28 February 2022, with periods of south-easterly trade winds and periods at the start and end of the simulation with light, northerly winds, as shown in Fig. 2b. However, the northerly periods in early February 2023 did not result in air temperature enhancements and incoming solar radiation was lower. This is also shown by top-of-atmosphere outgoing shortwave radiation flux being higher than in February 2022, indicating that there was more cloud cover (see model and satellite observation comparison in Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information). Crucially, there was no mass coral bleaching event in 2023. The third simulation period is the end of February 2023, providing a contrasting meteorological scenario. Between 18 and 28 February 2023, winds remained south-easterly and air temperatures below 28 °C (Fig. 2c).

Sulfate aerosol changes due to ship emissions

Figure 3 shows changes in \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol amounts over the model domain in different simulation scenarios. During 18–28 February 2022, the mean calculated enhancement in \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol due to pre-FSC05 regulation ship emissions alone is 0.14 μg kg−1, or around 24% (Fig. 3a). There is a strong enhancement of \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol within the shipping corridors to the east of the GBR, but also signficant \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol increase close to the Queensland coast. Implementation of FSC05 regulations halves the enhancement in \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol compared to the NoShips emission scenario (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c shows that the post-FSC05 scenario reduces the amount of \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol by 10% compared to the pre-FSC05 change in February 2022, with the spatial impact of the pollutant change again accumulated over the GBR/coastal corridor and further out to sea in the trans-continental shipping lanes.

a Difference between pre-FSC05 regulation and the NoShips scenario during February 2022, b difference between post-FSC05 regulation and the NoShips scenario during February 2022, c difference between post- and pre-FSC05 regulation conditions during February 2022 and d difference between post- and pre-FSC05 regulation conditions during 18–28 February 2023. Panels a–c highlight the accumulation of pollutant effects during the pre-bleaching period in 2022, while panel d highlights that if strong south-easterly trade winds dominate, pollutant effects are dissipated. Maps are annotated above with the mean absolute and percentage changes over the GBR and ocean regions. Location markers are the same as in Figure 1a.

Figure 3d shows that if we compare post-FSC05 and pre-FSC05 emission conditions in the 18–28 February 2023 period, however, when south-easterly trade winds were persistent, then the magnitude of the accumulated pollutant impact is greatly reduced. When trade winds are persistent, the \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol change due to emission regulation drops to 0.03 from 0.07 μg kg−1 when a period of light northerly winds is included in the simulation. We saw a similar result in terms of the magnitude and spatial variation for cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and amount and aerosol optical depth (AOD), with the emissions regulation simulated during 18-28 February 2023 producing much smaller changes than the 3–14 February 2023 and 18–28 February 2022 periods (see Supplementary Information Fig. S10). For example, the post-FSC05 regulation means changes in CCN at 0.2% supersaturation over the GBR for the two periods with a light north wind scenario were –8.7 and −8.8 cm−3, respectively, compared to only −2.6 cm−3 for the persistent trade wind period. \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol, CCN and AOD changes in all simulations exceeded the mean model internal variability (IMV) as shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S8 (see the “Methods” section for details on IMV calculation).

The accumulation of pollutant effects during the 18–28 February 2022 period was also observed for several key gas-phase oxidative chemistry species. Figure S11 in the Supplementary Information shows that compared to the NoShips simulation, post-FSC05 conditions in the lead-up to the bleaching event result in a 34% increase in surface level SO2 over the GBR, along with increases of 97% for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), 36% for formaldehyde, 47% for ozone (O3) and 90% for hydroxyl radicals (OH).

Shortwave radiation changes due to ship emissions

During the pre-bleaching period in 2022, we see that changes in ship emissions would likely have resulted in changes to aerosol concentrations over the GBR. Next, we see whether this would have led to changes in the amount of downwards shortwave radiation at the bottom of the atmosphere (SWDNB). Figure 4a shows that in the 18–28 February 2022 period, the pre-FSC05 emission scenario effectively masked a mean of 13 W m−2 SWDNB reaching the GBR during the daytime (results averaged over 9:00–18:00 local time). Post-FSC05 regulation, this influence of ship emissions on SWDNB is reduced to −4.1 W m−2, with the pre-FSC05–post-FSC05 SWDNB de-masking equating to 11 W m−2. The 24-h mean of SWDNB change for the same simulation is slightly more than half the 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. mean, at 6.6 W m−2. There is a large root mean squared deviation (RMSD) associated with the total SWDNB changes due to the highly variable nature of cloud fields in WRF-Chem simulations. However, the mean IMV for SWDNB is only 1.6 W m−2, meaning that the SWDNB changes described here are larger than can be described by model noise alone. We found that net radiative forcing at the top of the atmosphere was similarly impacted by ship emission changes during the 18–28 February 2022 period (see Supplementary Information Fig. S7b).

Each violin captures the spatiotemporal variability and mean (blue dashed line) of SWDNB change. a Shows all-sky SWDNB changes, b shows clear-sky only SWDNB changes. In each of a and b, the left three violins show changes for 18–28 February 2022 with varying ship emission scenarios. The right three violins (yellow) show changes for the post-FSC05–pre-FSC05 scenario in the three different simulation periods.

Figure 4a also shows, however, that the SWDNB de-masking associated with the FSC05 emission regulation was less pronounced in the two other simulation periods. In the persistent trade wind period of 18–28 February 2023, the RMSD was larger than for 18–28 February 2022, but the mean SWDNB change was reduced from 11 to 2.2 W m−2. This indicates that strong trade winds rapidly advecting the ship pollution away from the GBR greatly dilute the influence of ship emissions on incoming shortwave radiation. The mean SWDNB change for 18–28 February 2023 is only slightly larger than the SWDNB IMV.

The SWDNB change due to FSC05 regulation is also much reduced in the 3–14 February 2023 period too, from 11 to 5.0 W m−2. This is despite northerly wind, doldrum-like conditions being present, allowing the accumulation of CCN, AOD and \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\) aerosol changes. The mean 5.0 W m−2 change for FSC05 regulation compared to pre-FSC05 conditions, for 3–14 February 2023, is still distinct from the 1.6 W m−2 SWDNB IMV. The doubly-strong solar radiation flux impact seen for February 2022 compared to 3–24 February 2023 occurs when the actual incoming solar radiation was much higher, as shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information Fig. S1. So a stronger influence of the ship emissions change is observed when the sky was clearer and when air temperatures were hotter. This strongly suggests that the bulk of the SWDNB impact predicted by WRF-Chem for ship emission changes is due to direct, rather than indirect aerosol-radiative effects.

This is supported by examining the mean clear-sky only SWDNB change for post-FSC05–pre-FSC05 emission reduction (Fig. 4b). In the 18–28 February 2022 scenario, the regulation-induced change is 8.5 W m−2, or 77% of the total SWDNB change. In the 3–14 February 2023 period, when it is less sunny on average, the regulation-induced clear-sky SWDNB change is only 2.4 W m−2, or half the total SWDNB change. It is worth noting that the much smaller RMSD associated with the clear-sky only SWDNB changes in Fig. 4b emphasises that the bulk of the radiative flux change uncertainty is due to cloud–radiation interactions. The clear-sky only SWDNB results also give confidence in the overall SWDNB results, as the range of changes for post-FSC05–pre-FSC05, and pre-FSC05–NoShips scenarios do not overlap with zero.

Supporting the primary importance of aerosol–radiation interactions in our results, we also find minimal changes in cloud liquid water path (CWP) or cloud optical thickness as a result of the FSC05 emission change (see IMV results in Supplementary Information Fig. S7). The mean CWP change over the period due to FSC05 regulation in the 18–28 February 2022 period is −0.67 g m−2, only one third higher than the IMV and <10% of the RMSD. The change in COT is −0.10, a quarter of the RMSD and less than the IMV for that variable.

Implications for marine heat waves and coral bleaching

Our WRF-Chem results quantify the extent to which ship aerosol emissions have likely reduced incoming solar radiation to the GBR ocean surface in the past, prior to FSC05 regulations and under the most severe pre-bleaching conditions: 14 W m−2 overall and almost 9 W m−2 from clear-sky conditions alone. To derive an equivalent global mean shortwave forcing comparable with other studies, we use the change in shortwave upwelling radiation at the top of the atmosphere (SWUPT, mean magnitude of the radiative effect −1.3 W m−2 over the ocean pre-FSC05 in February 2022) and the calculation method outlined in Marelle et al. (2016)37. Multiplying −1.3 W m2 by the area of the simulation domain, we obtain the forcing in Watts, which is then divided by the surface area of the earth to give −15.1 mW m−2. In the post-FSC05 emissions, February 2022 scenario, the whole-ocean SWUPT radiative effect is −1.1 W m−2, giving an equivalent global mean TOA forcing of −12.8 mW m−2. These are 1.7 and 1.4 times larger, respectively, than the value calculated in Marelle et al. (2016)37, who simulated the impact of pre-FSC05 ship emissions around Norway. However, in the 3–14 February 2023 scenario with lower clear sky radiative effect from the emissions regulation, the mean SWUPT change is −0.68 W m−2, giving an equivalent global mean TOA forcing of −7.9 mW m−2, more comparable with the results of Marelle et al. (2016)37. However, equivalent global mean radiative forcing estimates due to ship emissions in this paper and Marelle et al. (2016) are much lower than in global modelling studies39,46 because they do not consider the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Large impacts on SWDNB from ship emissions have been shown in Schreier et al. (2006)16, with up to 43 W m2 less shortwave radiation penetrating ship-track pixels than non-ship-track pixels in satellite data taken over the North Atlantic. Considering all low cloud pixels compared to ship track pixels, the shortwave decrease was around 2 W m−2 in their scene, but this does not include direct aerosol effects, which our WRF-Chem clear-sky SWDNB results show to be substantial.

Masiri et al. (2008)5 found a 1% decade−1 increasing trend in surface incoming solar radiation over the GBR and postulated that this may be influencing the increasing trend in coral bleaching events. Our results suggest that this trend may have been occurring despite the decrease in SWDNB due to pre-FSC05 ship emissions, especially during clear-sky conditions. Zhao et al. (2021) determined that during severe coral bleaching events, negative total cloud cover anomalies and associated positive shortwave downwards radiation (SWDNB) anomalies at the surface were strongly correlated with regions of high sea surface temperature6. Our results indicate that with the implementation of FSC05 regulations, a substantial part of the surface dimming effect of shipping emissions over the GBR during exactly these periods has been removed. Enhancements in SWDNB during the events studied by Zhao et al. (2021) were in the range of 10–30 W m−2 6, while the surface shortwave flux anomaly over the GBR during the 2022 mass bleaching event was estimated to be 43 W m−254. The 24-h mean SWDNB changes attributable to the post-regulation change in SWDNB in February 2022, therefore, represent 15% of the SWDNB anomaly reported by Richards et al. (2024)54.

Karnauskas et al. (2020) showed that in the lead up to the 2016 GBR bleaching event, surface heating rate anomalies of between 0.4 and 0.8 °C month−1 explained the bulk of the GBR mixed layer energy budget changes7. Here, we use the surface net radiative forcing NETRFsurf to estimate the likely marine heating rate in °C month−1 associated with the ship sulfate emission regulation. The attributable heating rate is calculated by dividing the 24-h mean NETRFsurf change by the product of the ocean mixed layer depth (taken to be 50 m following Huang et al., 202457), a mean value for the specific heat capacity of sea water (3850 J kg−1 K−1) and a mean value for sea water density (1025 kg m−3). Note that this gives the air–sea flux heating rate only, neglecting advection terms. This result is a heating rate resulting from the FSC05 changes in late February 2022 of 0.06 °C month−1, or ≈10% of pre-2016 bleaching surface energy budget anomalies. The value is half this for the more cloudy 3–14 February 2023 period. These results suggest that periods of summertime northerly winds at the GBR, the cleaner atmosphere created by FSC05 regulations, may exacerbate positive radiative flux anomalies by 5–10%. Even so, this localised effect may be swamped by global post-FSC05 global radiative forcing increases, estimated to be between 12042 and 200 mW m−2 44 (≈10 times more than our estimated equivalent ship-derived global radiative forcing).

We also contextualise our results in terms of coral bleaching stress using relationships derived from response rates in Harrison et al. (2019)11. That work used the eReefs hydrodynamic model with atmospheric inputs from the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator (ACCESS) to simulate the impact of changes in downwards shortwave radiation on GBR sea surface temperature (SST). Simulations were run for a range of forcings, over different parts of the GBR, and for two summers, 2016 and 2017, showing that when a forcing was applied continuously over a period of 3 months, the SST change was primarily driven by the net downwards shortwave radiation change. Neither the summer period simulated, nor whether the forcing was applied intermittently or evenly, significantly impacted the relationship between SST and SWDNB. The linear relationship of 0.225 °C per 10 W m−2 forcing (SWDNB forcing from all hours of the day, not just daylight hours) described the magnitude of the expected cooling due to SWDNB change. Applying the results in Harrison et al. (2019) to simulated periods with northerly wind conditions, we find a range of SST variations attributable to the FSC05 regulation of 0.05 °C (3–14 February 2023 period) to 0.15 °C (18–28 February 2022 period).

The latter represents an additional coral stress, for the extreme pre-mass bleaching event post-FSC05 regulation scenario, of 1.8 °C heating weeks (DHW) in the case of ambient temperature being at or above the maximum monthly mean for 12 weeks58. The threshold for severe widespread coral bleaching and associated mortality is 8 DHW59 and during the 2022 mass bleaching event, large portions of the GBR regions peaked at ≈8, 10–12 DHW55. In DHW terms, our results therefore suggest that the aerosol de-masking due to ship sulfate regulations may have made bleaching conducive conditions more likely by around 10% in the hot and sunny lead-up to the 2022 mass bleaching event. This is on par with the 10% demasking influence calculated using the radiative flux approach above.

It is important to note that this local radiative effect will be acting in addition to the warming of the surrounding Eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures due to reductions in global shipping sulfate emissions45. Widespread SST increases will flow on to the GBR in a way not represented by our modelling scenario, meaning that our estimate of increased coral bleaching risk due to reduced ship sulfate is likely conservative.

The strong shortwave radiation response to the ship emission change during the hot, sunny lead-up to 2022’s mass coral bleaching event may also provide insight into the usefulness of solar radiation management at the Great Barrier Reef. The strength of this response compared to the late-February 2023 period, with persistent trade winds, indicates that, according to WRF-Chem, surface-level emissions of CCN along the major shipping routes east of Australia are likely to be advected away from the GBR during such conditions and provide minimal benefit in shading the GBR. Our results show that a marine cloud brightening scenario in which ships of opportunity in the major shipping lanes were used as the dispersion mechanism would most likely be beneficial when light northerly winds are present to aid the accumulation of aerosol effects. During particularly hot sunny periods, the direct effect of artificially enhanced CCN levels may contribute strongly to decreased incoming shortwave radiation, suggesting that marine sky brightening to target the aerosol direct effect might be most beneficial during these conditions. However, further studies over longer time periods are required to further constrain the influence of enhanced CCN on both indirect aerosol-cloud-radiation and direct aerosol-radiation effects over the GBR, and thus the efficacy of marine cloud or sky brightening in this region.

Methods

WRF-Chem configuration

The Weather Research and Forecasting Model coupled to chemistry (WRF-Chem v3.9.152) has previously been used to study the influence of shipping emissions on air quality and radiative forcing in refs. 60,37. We simulate meteorology and chemistry using WRF-Chem over three separate periods: 18–28 February 2022, 18–28 February 2023 and 3–14 February 2023. In each case, the previous 2 days were used as a model spin-up. We chose the 2022 period to capture a range of conditions at the GBR in the lead-up to the 2022 mass bleaching event, and the 2023 period to provide counterpoints with a range of meteorological conditions in a year that did not see a mass bleaching event (as summarised in Fig. 2).

The spatial resolution was 9 × 9 km, with grid dimensions of 255 (east–west) and 270 (north–south) giving a total area of 4725 km2. We used 40 vertical levels up to 20 km altitude. The extent of the simulation domain is shown in Fig 1a. Boundary and initial conditions were derived from ERA5 reanalysis61. Key WRF physics namelist settings, informed by the sensitivity analysis for WRF simulations at the GBR by Zhao et al.62, included the Yonsei University boundary layer scheme63, the Kain–Fritsch cumulus paramaterization scheme64, the RRTMG radiative transfer scheme for both short- and long-wave radiation65, the Noah Land Surface model66 and the Morrison double-moment microphysics scheme67. WRF-Chem chemistry namelist settings were informed by the optimal configuration in previous MCB simulations at the GBR11. These included the Fast-J photolysis scheme68, CBMZ gas phase chemical mechanism69 and the MOSAIC 8-bin aerosol scheme70. The chemistry namelist options are also the same as used in the study of STEAM ship emissions on air quality and radiative forcing over Norway and the Arctic by Marelle et al. 37. Analysis nudging was used to ERA5, for u- and v-winds in the boundary layer, but not temperature or water vapour.

We assessed the significance of our results relative to the internal model variability (IMV) by conducting four additional ensemble simulations in WRF-Chem. Our ensemble method involves analysing the same period, 18–28 February 2022, with different start times (15 February 00:00, 15 February 12:00, 16 February 12:00 and 17 February 00:00) to create different meteorological initial conditions, following the example in Singh et al. (2021)75. All ensemble simulations use post-FSC05 regulation ship emissions. The IMV for a given variable is calculated as the difference between the standard post-FSC05 simulation (starting on 16 February, 00:00) and the mean of the four ensemble members, as this difference would be zero in an ideal scenario where the result was not impacted by the initial conditions. A significant result for a given variable due to ship emission changes is where that result is greater in magnitude than the absolute value of the IMV for that variable. The IMV values for all variables discussed in this paper are shown in the Supplementary Information (Figs. S7–S9).

Ship emissions inventory

We used a shipping emissions inventory derived from the Ship Traffic Emissions Assessment Model version 2 (STEAM)49,50,51. Automatic Identification System (AIS) information from individual ships is used to geolocate vessels in STEAM. Detailed technical specifications for each vessel are obtained from its Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) or International Maritime Organization (IMO) numbers. The positioning, speed and vessel specifications are then used to calculate fuel consumption, whether the ship is in port or in transit. Note that STEAM is not able to model emissions from small boats without AIS transponders. Emitted species in the STEAM inventory are sulfur dioxide (SO2), sulfate aerosol (\({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\)), black carbon (BC) and organic carbon (OC) aerosol, nitrogen oxides (NOx, 94% as nitric oxide NO, 6% as nitrogen dioxide NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4) and lumped volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

STEAM was run for February 2022 over the Coral and Tasman Seas, east of Australia and incorporating the GBR region, producing emission files at 1 hourly temporal resolution and 1 × 1 km spatial resolution. These were later re-gridded to match the WRF-Chem resolution and domain. As the WRF-Chem simulations were conducted using the EDGAR inventory for other anthropogenic emissions, we incorporated STEAM emissions in WRF-Chem by replacing the EDGAR ship emissions with the STEAM ship emissions in the EDGAR input files. \({{{{\rm{SO}}}}}_{4}^{2-}\), BC and OC emissions were divided 20% into the Aitken mode EDGAR particulate emission category (<0.1 μm) and 80% into the accumulation mode category (>0.1 μm), consistent with the mass-fraction size distribution measurements in Chu et al. (2018)71 and Lyranen et al. (1999)72. A source of uncertainty we do not consider here is potential changes to the ship emission aerosol size distribution following FSC regulation73. Bulk VOC emissions in STEAM were speciated to the CBMZ and EDGAR VOC species following the methodology in Xiao et al. (2018)74. That is (EDGAR names in brackets, percentages all by mass), 1.29% small alcohols and alkanes (‘HC3’), 3.35% medium chain alcohols and hydrocarbons (‘HC5’), 3.62% xylene and other large aromatics (‘XYL’), 6.65% ketones (‘KET’), 9.53% medium chain alkenes (‘OLI’), 14.85% toluene and benzene (‘TOL’) and 52.36% long-chain hydrocarbons (‘HC8’).

For consistency of emissions between simulation periods, we used the same ship emissions input for the February 2023 simulations as for February 2022. We conducted model evaluation using the post-FSC05 emissions scenario results, as they represent our best understanding of current emissions for this region. Model evaluation was conducted using in-situ meteorological and air pollution datasets collected in Queensland, and also using satellite air pollution and cloud datasets. An overview of the model evaluation is given in the Supplementary Information (Figs. S2–S6).

Data availability

WRF-Chem output files and emission files for this work are available in the following publicly accessible repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15115134.

Code availability

WRF-Chem code is publicly available at https://github.com/wrf-model/WRF. Details of the Ship Track Emissions Assessment Model are in Johansson et al. (2017)51. Namelist settings files for this work are available in the following publicly accessible repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15115134.

References

Ainsworth, T. D. et al. Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 352, 338–342 (2016).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377 (2017).

Bindoff, N. et al. Changing ocean, marine ecosystems, and dependent communities. In Portner, H.-O. et al. (eds.) IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate 447–587 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

AIMS. Coral Bleaching Events https://www.aims.gov.au/research-topics/environmental-issues/coral-bleaching/coral-bleaching-events (2024).

Masiri, I., Nunez, M. & Weller, E. A 10-year climatology of solar radiation for the Great Barrier Reef: implications for recent mass coral bleaching events. Int. J. Remote Sens. 29, 4443–4462 (2008).

Zhao, W., Huang, Y., Siems, S. & Manton, M. The role of clouds in coral bleaching events over the Great Barrier Reef. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093936 (2021).

Karnauskas, K. B. Physical diagnosis of the 2016 Great Barrier Reef bleaching event. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086177 (2020).

Tagliafico, A., Baker, P., Kelaher, B., Ellis, S. & Harrison, D. The effects of shade and light on corals in the context of coral bleaching and shading technologies. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 919382 (2022).

Butcherine, P. et al. Intermittent shading can moderate coral bleaching on shallow reefs. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1162896 (2023).

Ellis, S. L. et al. Shading responses are species-specific in thermally stressed corals. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1333806 (2024).

Harrison, D. et al. T14: Environmental Modelling of Large-scale Solar Radiation Management. A report provided to the Australian Government by the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program. Technical Report (EGUsphere Preprint Repository, 2014).

Condie, S. A. et al. Large-scale interventions may delay decline of the Great Barrier Reef. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 201296 (2021).

Tollefson, J. Can artificially altered clouds save the Great Barrier Reef?. Nature 596, 476–478 (2021).

Harrison, D. P. An overview of environmental engineering methods for reducing coral bleaching stress. In Oceanographic Processes Coral Reefs: Physical and Biological Links in the Great Barrier Reef (eds Wolanski, E. & Kingsford, M. J.) 403–418 (Taylor and Francis, CRC Press, 2024).

Capaldo, K., Corbett, J. J., Kasibhatla, P., Fischbeck, P. & Pandis, S. N. Effects of ship emissions on sulphur cycling and radiative climate forcing over the ocean. Nature 400, 743–746 (1999).

Schreier, M. et al. Impact of ship emissions on the microphysical, optical and radiative properties of marine stratus: a case study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 4925–4942 (2006).

Twomey, S. The influence of pollution on the shortwave albedo of clouds. J. Atmos. Sci. 34, 1149–1152 (1977).

Manshausen, P., Watson-Parris, D., Christensen, M. W., Jalkanen, J.-P. & Stier, P. Invisible ship tracks show large cloud sensitivity to aerosol. Nature 610, 101–106 (2022).

Schreier, M., Mannstein, H., Eyring, V. & Bovensmann, H. Global ship track distribution and radiative forcing from 1 year of AATSR data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, (2007).

Parliament of Australia. Policy, Regulatory, Taxation, Administrative and Funding Priorities for Australian Shipping (Parliament of Australia, 2020).

Van, T. C. et al. On-board measurements of particle and gaseous emissions from a large cargo vessel at different operating conditions. Environ. Pollut. 237, 1–10 (2017).

Jahangiri, S., Nikolova, N. & Tenekedjiev, K. Health risk assessment of engine exhaust emissions within Australian ports: a case study of Port of Brisbane. Environ. Pract. 21, 20–35 (2019).

Broome, R. A. et al. The mortality effect of ship-related fine particulate matter in the Sydney greater metropolitan region of NSW, Australia. Environ. Int. 87, 85–93 (2016).

Toscano, D., Murena, F., Quaranta, F. & Mocerino, L. Assessment of the impact of ship emissions on air quality based on a complete annual emission inventory using AIS data for the port of Naples. Ocean Eng. 232, 109166 (2021).

Karl, M. et al. Effects of ship emissions on air quality in the Baltic Sea region simulated with three different chemistry transport models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 7019–7053 (2019).

Viana, M. et al. Impact of maritime transport emissions on coastal air quality in Europe. Atmos. Environ. 90, 96–105 (2014).

Liu, Z. et al. Influence of ship emissions on urban air quality: a comprehensive study using highly time-resolved online measurements and numerical simulation in Shanghai. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 202–211 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Shipping emissions and their impacts on air quality in China. Sci. Total Environ. 581, 186–198 (2017).

Chen, C., Saikawa, E., Comer, B., Mao, X. & Rutherford, D. Ship emission impacts on air quality and human health in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region, China, in 2015, with projections to 2030. GeoHealth 3, 284–306 (2019).

Campbell, P., Zhang, Y., Yan, F., Lu, Z. & Streets, D. Impacts of transportation sector emissions on future US air quality in a changing climate. Part I: Projected emissions, simulation design, and model evaluation. Environ. Pollut. 238, 903–917 (2018).

Williams, E., Lerner, B., Murphy, P., Herndon, S. & Zahniser, M. Emissions of NOx, SO2, CO, and HCHO from commercial marine shipping during Texas Air Quality Study (TexAQS) 2006. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 114, D21306 (2009).

Vutukuru, S. & Dabdub, D. Modeling the effects of ship emissions on coastal air quality: a case study of southern California. Atmos. Environ. 42, 3751–3764 (2008).

Dong, J., Zeng, J., Yang, Y. & Wang, H. A review of law and policy on decarbonization of shipping. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, (2022). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.1076352.

Holmes, C., Prather, M. & Vinken, G. The climate impact of ship NOx emissions: an improved estimate accounting for plume chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 6801–6812 (2014).

Myhre, G. et al. Radiative forcing due to changes in ozone and methane caused by the transport sector. Atmos. Environ. 45, 387–394 (2011).

Lauer, A., Eyring, V., Hendricks, J., Jöckel, P. & Lohmann, U. Global model simulations of the impact of ocean-going ships on aerosols, clouds, and the radiation budget. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 5061–5079 (2007).

Marelle, L. et al. Air quality and radiative impacts of Arctic shipping emissions in the summertime in northern Norway: from the local to the regional scale. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 2359–2379 (2016).

Marmer, E. & Langmann, B. Impact of ship emissions on the Mediterranean summertime pollution and climate: a regional model study. Atmos. Environ. 39, 4659–4669 (2005).

Partanen, A.-I. et al. Climate and air quality trade-offs in altering ship fuel sulfur content. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 12059–12071 (2013).

Sofiev, M. et al. Cleaner fuels for ships provide public health benefits with climate tradeoffs. Nat. Commun. 9, 406 (2018).

Gray, N., McDonagh, S., O’Shea, R., Smyth, B. & Murphy, J. D. Decarbonising ships, planes and trucks: An analysis of suitable low-carbon fuels for the maritime, aviation and haulage sectors. Adv. Appl. Energy 1, 100008 (2021).

Gettelman, A. et al. Has reducing ship emissions brought forward global warming?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109077 (2024).

Skeie, R. B., Byrom, R., Hodnebrog, Ø, Jouan, C. & Myhre, G. Multi-model effective radiative forcing of the 2020 sulfur cap for shipping. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 13361–13370 (2024).

Yuan, T. et al. Abrupt reduction in shipping emission as an inadvertent geoengineering termination shock produces substantial radiative warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 281 (2024).

Yoshioka, M., Grosvenor, D. P., Booth, B. B. B., Morice, C. P. & Carslaw, K. S. Warming effects of reduced sulfur emissions from shipping. EGUsphere 2024, 1–19 (2024).

Quaglia, I. & Visioni, D. Modeling 2020 regulatory changes in international shipping emissions helps explain anomalous 2023 warming. Earth Syst. Dyn. 15, 1527–1541 (2024).

Watson-Parris, D. et al. Surface temperature effects of recent reductions in shipping SO2 emissions are within internal variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 25, 4443–4454 (2025).

Sengupta, A., King, A. D. & Ryan, R. G. Inequity in population exposure to accelerated warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110644 (2024).

Jalkanen, J.-P. et al. A modelling system for the exhaust emissions of marine traffic and its application in the Baltic Sea area. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 9209–9223 (2009).

Jalkanen, J.-P. et al. Extension of an assessment model of ship traffic exhaust emissions for particulate matter and carbon monoxide. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 2641–2659 (2012).

Johansson, L., Jalkanen, J.-P. & Kukkonen, J. Global assessment of shipping emissions in 2015 on a high spatial and temporal resolution. Atmos. Environ. 167, 403–415 (2017).

Grell, G. A. et al. Fully coupled “online” chemistry within the WRF model. Atmos. Environ. 39, 6957–6975 (2005).

Grigoriadis, A. et al. Development of exhaust emission factors for vessels: a review and meta-analysis of available data. Atmos. Environ.: X 12, 100142 (2021).

Richards, L. S. et al. The meteorological drivers of mass coral bleaching on the central Great Barrier Reef during the 2022 La Niña. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–17 (2024).

McGowan, H. & Theobald, A. Atypical weather patterns cause coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia during the 2021–2022 La Niña. Sci. Rep. 13, 6397 (2023).

GBRMPA. Reef Snapshot: Summer 2021–22. Technical Report (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), 2022).

Huang, Z., Feng, M., Dalton, S. J. & Carroll, A. G. Marine heatwaves in the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea: their mechanisms and impacts on shallow and mesophotic coral ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168063 (2024).

Liu, G., Strong, A. E. & Skirving, W. Remote sensing of sea surface temperatures during 2002 Barrier Reef coral bleaching. EOS Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 84, 137–141 (2003).

GBRMPA. Annual Summary Report Of The Great Barrier Reef Coral Reef Condition 2022/2023: A Pause in Recent Coral Recovery Across Most of the Great Barrier Reef. Technical Report (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), 2023).

Mölders, N., Porter, S. E., Cahill, C. F. & Grell, G. A. Influence of ship emissions on air quality and input of contaminants in southern Alaska National Parks and Wilderness Areas during the 2006 tourist season. Atmos. Environ. 44, 1400–1413 (2010).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Zhao, W., Huang, Y., Siems, S. T., Manton, M. J. & Harrison, D. P. Interactions between trade-wind clouds and local forcings over the Great Barrier Reef: a case study using convection-permitting simulations. EGUsphere 2023, 1–30 (2023).

Hong, S.-Y., Noh, Y. & Dudhia, J. A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Mon. Weather Rev. 134, 2318–2341 (2006).

Janjić, Z. I. Comments on “Development and evaluation of a convection scheme for use in climate models”. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 3686–3686 (2000).

Mlawer, E. J., Taubman, S. J., Brown, P. D., Iacono, M. J. & Clough, S. A. Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 102, 16663–16682 (1997).

Chen, F. & Dudhia, J. Coupling an advanced land surface–hydrology model with the Penn State–NCAR MM5 modeling system. Part I: Model implementation and sensitivity. Mon. Weather Rev. 129, 569–585 (2001).

Morrison, H. & Milbrandt, J. Comparison of two-moment bulk microphysics schemes in idealized supercell thunderstorm simulations. Mon. Weather Rev. 139, 1103–1130 (2011).

Wild, O., Zhu, X. & Prather, M. J. Fast-J: accurate simulation of in-and below-cloud photolysis in tropospheric chemical models. J. Atmos. Chem. 37, 245–282 (2000).

Zaveri, R. A. & Peters, L. K. A new lumped structure photochemical mechanism for large-scale applications. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 104, 30387–30415 (1999).

Zaveri, R. A., Easter, R. C., Fast, J. D. & Peters, L. K. Model for simulating aerosol interactions and chemistry (MOSAIC). J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 113, (2008).

Chu-Van, T. et al. On-board measurements of particle and gaseous emissions from a large cargo vessel at different operating conditions. Environ. Pollut. 237, 832–841 (2018).

Lyyränen, J., Jokiniemi, J., Kauppinen, E. I. & Joutsensaari, J. Aerosol characterisation in medium-speed diesel engines operating with heavy fuel oils. J. Aerosol Sci. 30, 771–784 (1999).

Seppälä, S. D. et al. Effects of marine fuel sulfur restrictions on particle number concentrations and size distributions in ship plumes in the Baltic Sea. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 3215–3234 (2021).

Xiao, Q. et al. Characteristics of marine shipping emissions at berth: profiles for particulate matter and volatile organic compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 9527–9545 (2018).

Singh, C., Singh, S. K., Chauhan, P. & Budakoti, S. Simulation of an extreme dust episode using WRF-Chem based on optimal ensemble approach. Atmos. Res. 249, 105296 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The Reef Restoration and Adaptation Programme is funded by the partnership between the Australian Government's Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. The authors would like to acknowledge the multiple Traditional Owner groups of the sea- and land-country in and around the Great Barrier Reef region. The authors also acknowledge the computational resources used for this modelling study, made available through the q90 project on Australia’s National Computational Infrastructure. R.R. also wishes to acknowledge Bethan White and Steven Utembe for their scientific guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.R. and R.S. conceived the study, R.R. conducted the WRF-Chem simulations and results analysis and wrote the original manuscript. L.J. prepared the STEAM ship emission inputs. D.H. provided coral-stress impact calculations. All authors contributed to the editing and redrafting of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Pallav Purohit and Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryan, R.G., Harrison, D.P., Johansson, L. et al. Ship fuel sulfur content regulations may exacerbate mass coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef. Commun Earth Environ 7, 46 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03088-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03088-1