Abstract

During the last glacial period, Heinrich Stadials disrupted North Atlantic circulation and induced major continental climate shifts. However, their spatial variability and latitudinal intensity remain poorly constrained. Here we investigate Heinrich Stadial signals across the West Mediterranean, West Africa and West-Central Africa by integrating pollen-based quantitative precipitation reconstructions, paleohydrological records and HadCM3B climate simulations. Results reveal pronounced aridity in the West Mediterranean, driven by reduced evaporation and weakened westerlies. West Africa also experienced aridity, primarily linked to intensified wind systems, including the northeast trade winds and African easterly jet. Notably, Heinrich Stadial 3 is absent in this region. By contrast, Heinrich Stadials are undetected in West-Central Africa, likely due to its transitional position between arid northern and humid southern air masses, positive evaporation-precipitation anomalies, and the influence of southeast trade winds that sustained humidity. These findings highlight strong regional contrasts in the Heinrich Stadial impacts over the last 70 kyr.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Heinrich Stadials (HSs) are characterized as the coldest and most arid stadials of the Northern Hemisphere glacial periods, lasting for a few thousand years (Supplementary Table 1)1,2,3,4. These stadials precede the Heinrich Events (HEs), which are characterized by massive iceberg discharges, mainly from the Laurentide and Fennoscandian ice sheets, and deposition of ice-rafted debris (IRD) in North Atlantic marine sediments5,6. The HSs are associated with a reduction in the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation (AMOC) due to large freshwater inputs in the North Atlantic, which had a profound impact on paleohydrology and vegetation across the Mediterranean and northern Africa7,8. In addition, the changes in the interhemispheric oceanic temperature gradient and heat distribution during these stadials caused a global southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the tropical rain belt, leading to latitudinal paleohydrological changes9. Since the HSs represent some of the most drastic environmental changes during the glacial periods in the North Atlantic, understanding their inland effects at different latitudes is of especial interest to the paleoclimatological, paleontological and archeological communities.

The impact of the HSs in Europe and some African areas has been extensively studied, in part because these cold and arid periods are most clearly recorded in the eastern Atlantic region4,10,11. However, regional gradients in the intensity of the HSs from the western Mediterranean to western equatorial Africa, and the associated atmospheric circulation patterns remain largely unexplored.

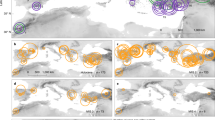

In this study, we focus on three regions representing different latitudinal zones: mid-latitude (West Mediterranean), mid-to-low latitude (West Africa) and low-equatorial latitude (West-Central Africa) (Fig. 1). To investigate past climate changes, we use pollen-based transfer functions, which is one of the most widely used and reliable methods to reconstruct quantitative continental precipitation and temperature in the past12, together with the SnSiZer tool to assess the statistical significance of trends in time series data13,14. However, this comparison is constrained by the limited availability of pollen records from low-latitude African regions and the general scarcity of pollen data from the last glacial period compared to the Holocene. To address this limitation, we supplement pollen data with dust records and hydrogen isotopes from leaf waxes, which serve as paleohydrological indicators of past precipitation and humidity conditions in western Africa15,16.

The study includes West Mediterranean pollen records (green squares), West-Central African pollen records (orange triangles), dust% and 230Th-normalized dust flux records (red dots), δD leaf wax records (blue diamonds) and the Humidity Index record (black square). The Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5 employ the same color-coding for the records of each proxy. Gray arrows represent the wind directions of the westerlies, northeast trade winds (NETW), African Easterly Jet (AEJ) and southeast trade winds (SETW). The shaded gray line shows the recent average position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

We also incorporate climate model simulations to better understand the atmospheric processes that may have caused the observed regional differences in the occurrence of HSs. In particular, the HadCM3B coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation model provides not only climate data but also quantitative values of past precipitation, temperature and wind activity17. These simulations contribute to a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of the causes and effects of the HSs across the West Mediterranean, West Africa and West-Central Africa.

Results

Stacked paleohydrological proxy results

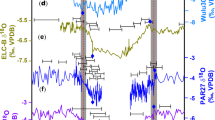

Instead of using individual records to detect the HSs, we combined mean annual precipitation (MAP) reconstructions, dust percentage (dust%), dust flux and δD leaf wax records into composite stacks, which represent the combined humidity records for each region (see Supplementary Methods for details) (Fig. 2). We then applied the SnSiZer analysis to identify the statistically significant HSs. A statistically significant HS is indicated by a statistically significant decrease in precipitation/humidity (blue clouds in Fig. 3) followed by a statistically significant increase in precipitation/humidity a few thousand years later (red clouds in Fig. 3) (see Methods for details).

a West Mediterranean MAP stack (mm/yr, LOESS = 0.015). b–e West African records: b Stack of dust% (normalized, inverted axis, LOESS = 0.01). c Stack of 230Th-normalized dust flux (normalized, inverted axis, LOESS smoothing = 0.02). d Humidity Index record. e Stack of δD leaf waxes (normalized, inverted axis, LOESS = 0.015). (f) West-Central African MAP stack (mm/yr, LOESS = 0.015). Gray shadings show the standard deviation for each record. The yellow vertical shades show the age-range of the Heinrich Stadials (HS6-HS1) and Younger Dryas (YD). In graphs a and f, the yellow stars on the vertical axes and discontinuous gray horizontal lines indicate the recent average annual precipitation in both regions (West Mediterranean = 444 mm/yr; West-Central Africa = 1629 mm/yr. See section Stacked paleohydrological proxy results and Supplementary Fig. 1).

a West Mediterranean MAP stack (mm/yr). b–e West African records: b Stack of dust% (normalized, inverted axis). c Stack of 230Th-normalized dust flux (normalized, inverted axis). d Humidity Index record. e Stack of δD leaf waxes (normalized, inverted axis). f West-Central African MAP stack (mm/yr). The left panels display the raw data, while the right panels show the SnSiZer graphs based on the raw data. In the SnSiZer graphs, blue and red clouds indicate statistically significant decreasing and increasing rainfall, respectively. The vertical axis represents the level of smoothing in logarithmic units. Dark gray areas represent non-significant changes, whereas light gray areas denote low sampling resolution. In both the left and right panels, the pink-blue-yellow lines correspond to different Nadaraya-Watson smoothing levels for each record. Statistically significant changes in the data occur when a given smoothing level (pink, blue or yellow horizontal lines) intersects a statistically significant feature (red or blue clouds). These intersections are marked with blue and red arrows, indicating statistically relevant periods of decreasing and increasing rainfall, respectively. To identify a Heinrich Stadial as statistically significant, the analysis must show a statistically relevant decrease in rainfall followed by a significant increase a few thousand years later. Vertical yellow shades show the age-range of the Heinrich Stadials (HS6-HS1) and Younger Dryas (YD), as defined by various studies (see Supplementary Table 1 for age-ranges).

In the West Mediterranean, our results suggest four periods of statistically significant droughts in the MAP reconstruction, which are related to HS5, HS3, HS2 and HS1 (Fig. 3a). The low MAP values during these HSs, ranging between 230 mm/yr for HS5 and 350 mm/yr for HS1, indicate a precipitation reduction of approximately 20-45% compared to present-day precipitation in the region (444 mm/yr, see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1). The decrease in the average MAP values between the pre-HS and the full HS conditions was around 200 mm/yr for HS5, 150–180 mm/yr for HS3, HS2 and HS1 and 60 mm/yr for HS4 (Fig. 2a).

In West Africa, the combined SnSiZer results for the four paleohydrological stacks show that the strongest HSs with statistically significant changes, identified in two out of the four stacked records (dust% and Humidity Index), are the HS5 and HS1 (Fig. 3b, d). Statistically significant increases in dust flux occur at the onset of these HSs, but no relevant decreases are observed (Fig. 3c). The HS4 is statistically significant only in the dust% record (Fig. 3b). The HS3 is not statistically significant in any of the records. Finally, the HS2 is statistically relevant in the δD leaf wax record, whereas in the dust% record it only significant at the beginning of the stadial (Fig. 3b, e).

Finally, the West-Central African MAP records show slight decreases during some HSs of the last 70 kyr BP, such as during HS5a, HS2 and HS1. However, these decreases are not statistically significant. In contrast, there is a strong and statistically significant dip between 38 and 34 kyr BP (Fig. 3f). The stacked West-Central African MAP record reaches its lowest values of 1100 mm/yr at 36–35 kyr BP (Fig. 2f), which represents about 30% less rainfall than at present (1629 mm/yr, see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1). The results of individual records used to create the stacks are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Results.

Climate model results

The HadCM3B modeling results for the HSs show a decrease in both precipitation and evaporation across the North Atlantic region, including western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, and North and West Africa (Fig. 4b, d). In the Iberian Peninsula, the negative precipitation anomaly is most pronounced for HS2. In the tropics, the precipitation anomaly indicates a southward shift in the position of the tropical rain belt and ITCZ compared to baseline climate (see the latitudinal movement of the wind convergence zone in Africa between Fig. 5a, b). This shift results in decreased precipitation across western and central tropical Africa, likely in response to cooling across the North Atlantic and the consequent increase in the meridional temperature gradient, which pushes the rainbelt southward.

a Baseline average and b anomalies of the precipitation simulations. c Baseline average and d anomalies of the evaporation simulations. The simulation represents the experiment with a freshwater flux of 0.4 Sv and a duration of 300 years. The squares in the map represent the area where the West Mediterranean and West-Central African records are located.

a Wind direction (vectors) and wind speed (contours) for the baseline climate, b wind direction and wind speed for each HS and c the wind anomalies between both baseline climate (a) and the simulations for each HS (b). The simulation represents the experiment with a freshwater flux of 0.4 Sv and a duration of 300 years. The squares in the map represent the area where the West Mediterranean and West-Central African records are located.

The model also shows a decrease in the strength of the westerlies over the mid-latitude North Atlantic. The latitudes of the weaker westerlies vary across different HSs, but they are generally confined approximately from 30°N to 50–60°N, and from 10–20°W to 50°W (Fig. 5c), especially during HS2 and HS3. The weakening of westerly winds is less pronounced during HS1 and HS4, when winds became stronger as they approached the European continent.

For West Africa, our modeling results indicate a strengthening of the North Atlantic trade winds during all the HSs. Similarly, we observe an intensification of the dry northeasterly Harmattan winds across the Sahara and Sahel regions, and a weakening of the moist southwesterlies across tropical Africa. Furthermore, the models show a weakening in the southeasterly trade winds in West-Central Africa. These stronger northeasterlies and weaker southeasterlies during the HSs are indicative of a southward shift in the tropical rainbelt, a pattern consistent across all the stadials (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

West Mediterranean MAP and climate simulations during HSs

Strong HS5, HS3, HS2 and HS1 signals

The statistically significant arid signals associated with HS5, HS3, HS2 and HS1 (Fig. 2a), together with negative rainfall anomalies simulated for all the HSs in the West Mediterranean (Fig. 4b), are primarily driven by the freshwater input into the high-latitudes of the North Atlantic. This input triggered negative mid-latitude North Atlantic wind anomalies ( ~ 30–60°N, ~10–50°W, Fig. 5c) and reduced ocean evaporation, as observed in our HadCM3B evaporation simulations (Fig. 4d). Freshwater inputs weakened the intensity of the AMOC and led to a reduction in North Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs)18,19, which contributed to reduced modeled evaporation rates for the Atlantic (Fig. 4d). These conditions suppressed the entry of moisture-laden storms into western Europe (Fig. 5c), further amplifying the aridity signal across the Mediterranean (Fig. 4b).

Absence of HS6 and HS4 signals

The absence of a statistically significant drought signal in the West Mediterranean MAP during HS6 and HS4 does not necessarily imply that no arid events occurred at ~64–60 and ~42–39 kyr BP. Instead, this may reflect chronological uncertainties in sediment cores specially beyond the radiocarbon-dated interval ( ~ 55 kyr BP)20. For the HS6, the absence of HS6 may result from age mismatches between the MAP decline recorded at 62 kyr BP in the ODP-976 and at 58 kyr BP in Padul (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In the original pollen studies from Padul21,22 and ODP-97623 dated this stadial to ~42–41 kyr BP and ~41.5–40.5 kyr BP, respectively. Accordingly, in our stack HS4 was reconstructed between ~42 and 40.5 kyr BP. In contrast, the MD95-2043 record places the HS4 later, at ~40-38.5 kyr BP7,24, which is ~2000 years younger than in Padul and ODP-976. This chronological offset likely explains why the stacked West Mediterranean MAP reconstruction does not clearly reflect the HS4 (Figs. 2a and 3a). To address this discrepancy, we performed a sensitivity test (see Supplementary Information) in which the MD95-2043 record was adjusted by shifting its chronology 2000 years older from the base of the core (48.1 kyr BP) to 37 kyr BP. This analysis yielded a statistically significant identification of the end of HS4 (Supplementary Fig. 7), thereby corroborating the presence of this stadial in the West Mediterranean. Note that, although this sensitivity test was performed, the main discussion of the article is based on the results derived from the original chronologies of the records.

West African paleohydrology and climate simulations during HSs

Strong HS5, HS5a and HS1 signals

The identification of West African HSs varies depending on the proxy datasets. During HS5a, HS5, and HS1, three out of four proxy stacks show statistically significant increases (dust%, dust flux) and decreases (Humidity Index), pointing to increased dust fluxes from the Sahara to the Atlantic during these drought periods (Figs. 2b–d and 3b–d). Climate simulations suggest that the freshwater forcing caused a southward displacement of the ITCZ by 1–2° (comparison between Fig. 5a, b) and generated a strengthening of both northeast trade winds (NETW) and the African easterly jet (AEJ) across all HSs (Fig. 5c). The intensification of our modeled NETW and AEJ promoted a southward migration of the Sahara/Sahel boundary and the southward expansion of the Sahara, which in turn enhanced dust mobilization and led to greater dust deposition at low-latitudes of the eastern Atlantic15,25. These mechanisms explain the clear identification of the statistically significant HSs in the studied proxy records (Figs. 2b, c and 3b, c).

It is worth noting that the clearest and most abrupt signals during several of the HSs are recorded in the eolian records and in the strong positive wind activity anomalies (Figs. 2b, c and 5c). In contrast, precipitation and humidity proxies (i.e., Humidity Index and δD leaf waxes) do not exhibit such abrupt signals. Moreover, precipitation model outputs do not show extremely negative anomalies, and the evaporation simulations suggests that the region lies at the transitional zone between negative anomalies to the north (above ~20°N) and positive anomalies to the south (below ~20°N) (Figs. 2d, e and 4b, d). These observations lead us to conclude that, although HS in this region are linked to reduced precipitation, the primary climatic factor driving the strongest and most distinct signals is the increased wind activity, specifically with the strengthening of the NETW and AEJ.

Weak HS4 and HS2 signals, and absence of HS3

Most of the West African proxy records do not identify statistically significant signals for HS4, HS3 and HS2 (except for HS4 in dust% and HS2 in δD leaf waxes) (Fig. 3b–e). The unclear and inconsistent signals regarding the aridity conditions of HS4 and HS2 in the West African records suggest that these two periods were not as arid as HS5 and HS1, although it does not exclude the occurrence of drought conditions. In contrast, the absence of HS3 in all the West African proxy stacks indicates a lack of arid conditions in the region (Figs. 2b–e and 3b–e). Similarly, records from the Canary Islands show no increase in the dust deposition during the HS325. The absence of drought in West Africa during HS3 may have been a consequence of a smaller SST decrease in mid- and low-latitude Atlantic compared with other HSs26,27. This could be linked to reduced glacial freshwater discharges from ice sheets, variations in the locations of freshwater inputs, or differences in the duration of the hosing period.

West-Central African MAP and climate simulations during HSs

Weak signals during all HSs

Our results show precipitation declines in the individual MAP reconstructions (Supplementary Fig. 5), but the stack does not show statistically significant HSs (Fig. 3f). According to our HadCM3B precipitation and evaporation simulations, this region lies at the boundary between positive and negative precipitation and evaporation anomalies (Fig. 4b, d) and is influenced by the southeast trade winds (SETW) (Fig. 5b), which may explain the weak HS signals. The negative wind anomalies and weak SETW simulated (Fig. 5c) appear to be related to the low tropical-subtropical SST gradient of the southeastern Atlantic. As also suggested by other modeling studies, the SST warming in both tropical and subtropical areas has been associated with enhanced equatorial African precipitation28,29, consistent with our broadly positive evaporation and precipitation anomalies in the Gulf of Guinea and in the southwestern African coast (Fig. 4b, d). The stronger evaporation and convective precipitation in West-Central Africa, combined with the weak but moisture-bearing SETW (Fig. 5b), could have produced strongly attenuated HS signals in this region (Figs. 2f and 3f).

In eastern Africa, dry conditions during HS1 have been reported at several sites, including Lake Victoria (1°S)30, Lake Challa (3°S)31 and Lake Tanganyika (7°S)32. However, the evidence is generally weaker compared with the West Mediterranean and West Africa, and the statistical significance of these events has not been evaluated. Similarly, Lake Bosumtwi (1500–2000 km west of our West-Central African study region) recorded an arid HS133,34. This may be explained by its more westerly position, stronger Atlantic influence, and consequently, greater climatic similarity to western Africa than to the tropical area of West-Central Africa.

Drought between 38 and 34 kyr BP

The only statistically significant drought identified in West-Central Africa occurred between 38 and 34 kyr BP (Figs. 2f and 3f). This is reflected in the increase in Afro-alpine grassland, lowland steppe and desert biomes, and decrease in Afromontane forest in the Lake Bambili pollen record35. Although this interval could be related to the HS4, it would be out-of-phase by ~2–4 kyr. It is therefore possible that the drought at 38-34 kyr BP was a regional event confined to West-Central Africa. Supporting this interpretation, the KZai-02 pollen record located in the mouth of the Zaire River (9°N-13°S) also shows a decrease in warm-temperate, pioneer and rain forests taxa between ~38 and 33 kyr BP, suggesting enhanced continental aridity and drying up of lowlands driven by rising temperatures, increased evaporation and reduced effective moisture36. Additional, though less likely, explanations for this drought are presented in the Supplementary Discussion.

Conclusions

Statistically significant decreases in the West Mediterranean MAP reconstruction during HS5, HS3, HS2 and HS1 indicate pronounced droughts, with values ranging from 230 to 350 mm/yr, corresponding to 20–45% below present-day annual precipitation. These quantitative reductions, together with modeled negative anomalies in evaporation, precipitation and wind activity, are linked to North Atlantic cooling and weakened westerly winds, which likely inhibited the influx of moist storms and amplified aridity across the western Mediterranean. The HS4 remains less clearly expressed due to chronological uncertainties.

In the West Africa, HS5a, HS5 and HS1 are characterized by statistically significant aridity signals. These droughts coincide with reduced evaporation and precipitation and are associated with a strengthening of the NETW, as shown in our climate simulations. The models also indicate a southward shift of the ITCZ, which combined with enhanced wind activity, led to increased dust mobilization. In contrast, the ambiguous and inconsistent proxy signals for HS4 and HS2 suggest that these stadials were less severe than HS5 and HS1. There is no statistically significant evidence for HS3, which may reflect smaller glacial freshwater discharges and a weaker North Atlantic SST compared to other HSs.

In West-Central Africa, the MAP reconstruction shows no statistically significant droughts during any HS, consistent with simulated anomalies in evaporation and precipitation over the Gulf of Guinea and southwestern African coast. Warming of both tropical and subtropical SSTs likely weakened the SETW in our simulations, contributing to enhanced ocean evaporation and convective precipitation, and thereby mitigating arid HS signals in this region.

When comparing the intensity of the last four HSs (HS4–HS1) between precipitation reconstructions and climate simulations for the West Mediterranean and West Central African regions, the models show similar precipitation patterns to those indicated by the MAP reconstructions. In contrast, in West Africa, although proxy records and simulations suggest a reduction in precipitation, the strongest signals are linked to enhanced wind activity, particularly the strengthening of the NETW and AEJ. These findings indicate that, rather than precipitation anomalies, wind dynamics were the primary factor driving climatic changes in this region during the HSs.

Methods

Paleohydrological records

We prioritized pollen records to quantitatively reconstruct annual rainfall across the three regions. However, due to the lack of long, high-resolution pollen records in West Africa, we supplemented these data with additional paleohydrological proxies to assess past humidity changes and wind strength in this area. These proxies include dust flux (seven records), dust percentages (three records), δD on lipid biomarkers (six records) and the Humidity Index record (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Detailed information, including descriptions of each paleohydrological proxy, record locations, and calibrations curves and references of the original studies, is provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Methods.

Fossil and modern pollen data, and recent annual precipitation

To quantitatively reconstruct MAP, we used selected fossil pollen records in combination with modern pollen training-sets. High-resolution fossil pollen records from southern Iberia (Padul-15-05) and Alboran Sea (MD95-2043, ODP-976), located in close proximity, were used to reconstruct MAP in the West Mediterranean. For the West-Central African region, four pollen records from Cameroon and the Gulf of Guinea (Bambili, Barombi, GIK16856-2, KW31) were employed (Table 1).

The modern pollen training-sets are based on the Eurasian Modern Pollen Database v2 (EMPDv2)37 and the African Modern Pollen Database (AMPD)38,39. MAP values were reconstructed using all available pollen sites from both databases, comprising 8174 sites in EMPDv2 and 1571 sites in AMPD (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

Taxonomic harmonization was conducted to ensure consistency between fossil and modern pollen data, resulting in a final dataset of 389 harmonized pollen taxa for the EMPDv2 and West Mediterranean records, and 534 taxa for the AMPD and West-Central African records. The harmonization was performed using the Plants of the World online database (www.plantsoftheworldonline.org) and the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (www.itis.gov). Pollen types of aquatic plants were excluded from the analysis. In addition, Rhizophora (a mangrove taxon), indicative of local vegetation signals, were removed from the African reconstructions40.

Pollen-based transfer function technique. Weighted averaging-partial least squares (WA-PLS) regression method

The quantitative MAP reconstructions were obtained using the WA-PLS calibrated regression method, which assumes a unimodal relationship between taxon abundance and climate parameters, and is robust to spatial autocorrelation41. To reconstruct the MAP, we used recent MAP values obtained from the WorldClim v2.1 database, which has a 30 s resolution (www.worldclim.org). To reduce the data noise, the square-root species transformation was applied to the modern pollen training-set. Although the WA-PLS regressions were run with five components, the two-component model was selected for the reconstructions. This choice was based on the consideration that increasing the number of components can lead to overfitting, thereby decreasing the model predictive value42. The reconstructions were run using the C2 software (version 1.7.7)43.

The reliability of the WA-PLS transfer function was evaluated through leave-one-out cross-validation, with performance statistics including the coefficient of determination (R2), the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) and the maximum bias44. For the West Mediterranean MAP reconstructions using the EMPDv2, the performance statistics yielded an R2 value of 0.51, an RMSEP of 284.5 mm/yr and a maximum bias of 2318.7 mm/yr. In contrast, the West-Central African MAP reconstructions using the AMPD showed an R2 of 0.72, an RMSEP of 322.5 mm/yr and a maximum bias of 1127 mm/yr (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Data processing

To increase the resolution of each paleoclimatic proxy and to improve our understanding of paleohydrological conditions over the last 70 kyr, particularly during HSs, we compiled the proxy records from the West Mediterranean, West Africa and West-Central Africa, resulting in the following stacks: the West Mediterranean MAP stack, the West African dust%, dust flux and δD leaf wax stacks, and the West-Central African MAP stack (Fig. 2). Given the wide latitudinal range of the West African proxy records (i.e., dust%, dust flux and δD leaf waxes), as well as the differences in the maximum range of absolute values across records, we run Z-score normalization (x – mean / standard deviation) on these proxies. The stacks were then generated by combining the normalized data into individual curves for each paleoclimate indicator, i.e., stacks of MAP, dust%, dust flux and δD leaf waxes (Fig. 2). To assess the robustness of this normalization process, we also applied Min-Max normalization and compared the results. However, since no significant differences were found between the two methods, we chose to proceed with Z-score normalization for consistency across the records.

The combination of paleoenvironmental and paleoclimate records with statistical analyses, such as the original SiZer method (“SIgnificant ZERo crossings of derivatives”)13,45 or the novel SnSiZer technique (“Scale‑Normalized SIgnificant ZERo crossing of derivatives”)14,22, provide valuable insights. These methods are particularly useful for identifying thresholds in the data and determining whether observed anomalies are statistically significant, thus offering an objective interpretation of underlying climate phenomena. This analysis allowed us to identify statistically significant decreasing and increasing precipitation trends recorded by the proxy records during the last glacial period and the Holocene. Particular emphasis was placed on the lowest rainfall periods associated with the HSs, to better understand their impacts across different regions and latitudes. Since the SnSiZer analysis requires high-resolution records to accurately identify statistically significant changes in trends, we collected high-resolution paleohydrological records from the three studied regions (Fig. 1).

In the SnSiZer graph, data changes are considered statistically significant when a given smoothing level (pink, blue or yellow horizontal lines) intersects the statistically significant increasing or decreasing features (Fig. 3). To identify statistically relevant HSs, and reading from past to present (from right to left in the SnSiZer graphs, Fig. 3), the SnSiZer should identify a statistically significant feature indicative of increasing aridity (blue clouds), followed by a significant trend related with increasing humidity a few thousand years later (red clouds). Note that while the dust%, dust flux and δD leaf wax records in Fig. 3 have inverted axes, the MAP reconstructions and the Humidity Index record do not. We applied the same color scheme to these proxies, where blue clouds indicate increasing aridity and red clouds indicate increasing precipitation. In some cases, we observed statistically relevant increases in aridity without a subsequent statistically significant increase in humidity, which, although indicative of an arid period, were not identified as statistically significant HSs. Further details on the SnSiZer analysis are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

HadCM3B climate modeling

To simulate the HSs, we performed an ensemble of experiments using the University of Bristol version of the HadCM3 model (HadCM3B), as described in Valdes et al. (2017)17. The most recent HSs are better studied due to the higher resolution and improved age control provided by paleoclimatic records. As such, modeling the last HSs of the last glaciation allows us to compare climate simulations with these records, providing more accurate results for the paleoclimatic interpretation of these periods compared to older HSs. We therefore carried out a set of experiments for each of the last four HSs, incorporating boundary conditions corresponding to HS1, HS2, HS3 and HS4. These simulations included varying greenhouse gas concentrations (CO2, N2O and CH4) derived from the Vostok Ice core46,47, orbital parameters and reconstructed ice sheet extents and elevation using the ICE-5G model48.

We initially ran a control simulation (orange line in Supplementary Fig. 6) followed by additional simulations involving the input of freshwater into the North Atlantic (referred to as “hosing”) to simulate the HEs (Supplementary Fig. 6). Although the climate models simulate the HEs, during which the freshwater input occurs in the North Atlantic, we simplify the nomenclature by using “HS” terminology in both the model simulations and proxy data analyses. A set of experiments was run for each HS, varying the freshwater input (0.05, 0.1, 0.4 and 1 Sv), for three durations (100, 300 and 500 years) and at four different locations (50-70°N whole Atlantic, 40-60°N whole Atlantic, 40-60°N West Atlantic and 40-60°N East Atlantic). We identify that the location of hosing input had minimal influence on the amplitude of the HS, so we focus specifically on the West Atlantic experiments. Each simulation was run for 1000 years, with North Atlantic hosing initiated after the first 50 years. The full set of experiments is shown in Supplementary Table 2, and the timeseries for simulations with hosing into the western Atlantic is presented in Supplementary Fig. 6.

To determine which model configurations to analyze, we compared the impact of the freshwater hosing on modeled SST across the western Mediterranean and the Iberian Peninsula (35°N – 40°N, 14°W – 4°E) against observed SST records for the same region26,49,50,51,52,53,54. The SST anomalies during HS1 and HS4 are more clearly represented in the proxy data, with anomalies of ~2 °C–4 °C and ~3.5 °C–4 °C, respectively. SST anomalies during HS2 and HS3 are less clearly defined, with cooling of ~2 °C–3 °C and ~3 °C–4 °C, respectively. These anomalies correspond most clearly to the 0.4 Sv freshwater input for 300 years into the western Atlantic for each of the HS boundary conditions. The cooling anomalies for HS1 to HS4, relative to the control simulation, are 3.5 °C, 2 °C, 2.5 °C and 3 °C, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). The baseline average is calculated from the first 50 years of the experiment prior to hosing. The HS anomaly is calculated from a 100-year average, with 50 years on either side of the end of the 300-year hosing period, minus the baseline period (Figs. 4 and 5).

Data availability

The quantitative stacked MAP (mm/yr) reconstructions from the West Mediterranean and West-Central Africa are available in Figshare data repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30731963.

References

McManus, J. F., Francois, R., Gherardl, J. M., Kelgwin, L. & Drown-Leger, S. Collapse and rapid resumption of Atlantic meridional circulation linked to deglacial climate changes. Nature 428, 834–837 (2004).

Clark, P. U. et al. The last glacial maximum. Science 325, 710–714 (2009).

Bout-Roumazeilles, V. et al. Connection between South Mediterranean climate and North African atmospheric circulation during the last 50,000yr BP North Atlantic cold events. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 3197–3215 (2007).

Allard, J. L., Hughes, P. D. & Woodward, J. C. Heinrich Stadial aridity forced Mediterranean-wide glacier retreat in the last cold stage. Nat. Geosci. 14, 197–205 (2021).

Guillevic, M. et al. Evidence for a three-phase sequence during Heinrich Stadial 4 using a multiproxy approach based on Greenland ice core records. Climate10, 2115–2133 (2014).

Reutenauer, C. et al. Quantifying molecular oxygen isotope variations during a Heinrich stadial. Climate 11, 1527–1551 (2015).

Fletcher, W. J. & Sánchez Goñi, M. F. Orbital- and sub-orbital-scale climate impacts on vegetation of the western Mediterranean basin over the last 48,000 yr. Quat. Res. 70, 451–464 (2008).

Bradley, R. S. & Diaz, H. F. Late quaternary abrupt climate change in the tropics and sub-tropics: the continental signal of tropical hydroclimatic events (THEs). Rev. Geophys. 59, e2020RG000732 (2021).

Mohtadi, M., Prange, M. & Steinke, S. Palaeoclimatic insights into forcing and response of monsoon rainfall. Nature 533, 191–199 (2016).

Fersi, W. et al. Imprint of seasonality changes on fluvio-glacial dynamics across Heinrich Stadial 1 (NE Atlantic Ocean). Glob. Planet. Change 204, 103552 (2021).

Ait Brahim, Y. et al. The spatiotemporal extent of the Green Sahara during the last glacial period. iScience 26, 107018 (2023).

Chevalier, M. et al. Pollen-based climate reconstruction techniques for late quaternary studies. Earth-Sci. Rev. 210, 103384 (2020).

Chaudhuri, P. & Marron, J. S. Sizer for exploration of structures in curves. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 807–823 (1999).

Ilvonen, L. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of Holocene precipitation change in the Iberian Peninsula. Boreas 51, 776–792 (2022).

Collins, J. A. et al. Abrupt shifts of the Sahara–Sahel boundary during Heinrich stadials. Climate 9, 1181–1191 (2013).

Tierney, J. E., Pausata, F. S. R. & deMenocal, P. B. Rainfall regimes of the Green Sahara. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601503 (2017).

Valdes, P. J. et al. The BRIDGE HadCM3 family of climate models: hadCM3@Bristol v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 3715–3743 (2017).

Patton, G. M., Martin, P. A., Voelker, A. & Salgueiro, E. Multiproxy comparison of oceanographic temperature during Heinrich Events in the eastern subtropical Atlantic. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 310, 45–58 (2011).

Bohm, E. et al. Strong and deep Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the last glacial cycle. Nature 517, 73–76 (2015).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Camuera, J. et al. Vegetation and climate changes during the last two glacial-interglacial cycles in the western Mediterranean: a new long pollen record from Padul (Southern Iberian Peninsula). Quat. Sci. Rev. 205, 86–105 (2019).

Camuera, J. et al. Past 200 kyr hydroclimate variability in the western Mediterranean and its connection to the African Humid Periods. Sci. Rep. 12, 9050 (2022).

Combourieu Nebout, N. et al. Enhanced aridity and atmospheric high-pressure stability over the western Mediterranean during the North Atlantic cold events of the past 50 k.y. Geology 30, 863 (2002).

Sánchez Goñi, M. et al. Synchroneity between marine and terrestrial responses to millennial scale climatic variability during the last glacial period in the Mediterranean region. Clim. Dyn. 19, 95–105 (2002).

Heinrich, H., Schmidt, C., Ziemen, F., Mikolajewicz, U. & Roettig, C.-B. Massive deposition of Sahelian dust on the Canary Island Lanzarote during North Atlantic Heinrich Events. Quat. Res. 101, 51–66 (2021).

Martrat, B. et al. Four climate cycles of recurring deep and surface water destabilizations on the Iberian margin. Science 317, 502–507 (2007).

Niedermeyer, E. M. et al. Extratropical forcing of Sahel aridity during Heinrich stadials. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L20707 (2009).

Kim, J.-H., Schneider, R. R., Mulitza, S. & Müller, P. J. Reconstruction of SE trade-wind intensity based on sea-surface temperature gradients in the Southeast Atlantic over the last 25kyr. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2144 (2003).

Schefuß, E., Schouten, S. & Schneider, R. R. Climatic controls on central African hydrology during the past 20,000years. Nature 437, 1003–1006 (2005).

Stager, J. C., Ryves, D. B., Chase, B. M. & Pausata, F. S. Catastrophic drought in the Afro-Asian monsoon region during Heinrich event 1. Science 331, 1299–1302 (2011).

Tierney, J. E., Russell, J. M., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Huang, Y. & Verschuren, D. Late Quaternary behavior of the East African monsoon and the importance of the Congo air boundary. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 798–807 (2011).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Northern Hemisphere controls on Tropical Southeast African climate during the past 60,000 years. Science 322, 252 (2008).

Shanahan, T. M. et al. Late Quaternary sedimentological and climate changes at Lake Bosumtwi Ghana: new constraints from laminae analysis and radiocarbon age modeling. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 361-362, 49–60 (2012).

Shanahan, T. M. et al. The time-transgressive termination of the African Humid Period. Nat. Geosci. 8, 140–144 (2015).

Lézine, A. M., Izumi, K., Kageyama, M. & Achoundong, G. A 90,000-year record of Afromontane forest responses to climate change. Science 363, 177–181 (2019).

Dalibard, M. et al. High-resolution vegetation history of West Africa during the last 145 ka. Geobios 47, 183–198 (2014).

Davis, B. A. S. et al. The Eurasian Modern Pollen Database (EMPD), version 2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2423–2445 (2020).

Ivory, S. J., Lézine, A.-M., Grimm, E. & Williams, J. Relaunching the African pollen database: abrupt change in climate and ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Mag. 28, 26 (2020).

Lézine, A.-M., Ivory, S. J., Gosling, W. D. & Scott, L. The African Pollen Database (APD) and tracing environmental change: State of the Art. In Quaternary Vegetation Dynamics (CRC Press, 2021).

Dupont, L. M. & Weinelt, M. Vegetation history of the savanna corridor between the Guinean and the Congolian rain forest during the last 150,000 years. Vegetation Hist. Archaeobotany 5, 273–292 (1996).

Telford, R. J. & Birks, H. J. B. The secret assumption of transfer functions: problems with spatial autocorrelation in evaluating model performance. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 2173–2179 (2005).

Ter Braak, C., Juggins, S., Birks, H. & Van der Voet, H. Weighted averaging partial least squares regression (WA-PLS): definition and comparison with other methods for species-environment calibration. In Multivariate environmental statistics (Elsevier, 1993).

Juggins, S. C2 version 1.7.7: software for ecological and palaeoecological data. (University of Newcastle, 2014).

Ter Braak, C. J. F. & Juggins, S. Weighted averaging partial least squares regression (WA-PLS): an improved method for reconstructing environmental variables from species assemblages. Hydrobiologia 269, 485–502 (1993).

Sonderegger, D. L., Wang, H., Clements, W. H. & Noon, B. R. Using SiZer to detect thresholds in ecological data. Front. Ecol. Environ. 7, 190–195 (2009).

Spahni, R. et al. Atmospheric methane and nitrous oxide of the late pleistocene from Antarctic Ice Cores. Science 310, 1317–1321 (2005).

Loulergue, L. et al. Orbital and millennial-scale features of atmospheric CH4 over the past 800,000years. Nature 453, 383–386 (2008).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: The global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 450–487 (2015).

Martrat, B. et al. Abrupt temperature changes in the Western Mediterranean over the past 250,000 years. Science 306, 1762–1765 (2004).

Martrat, B., Jimenez-Amat, P., Zahn, R. & Grimalt, J. O. Similarities and dissimilarities between the last two deglaciations and interglaciations in the North Atlantic region. Quat. Sci. Rev. 99, 122–134 (2014).

Cacho, I. et al. Dansgaard-Oeschger and Heinrich event imprints in Alboran Sea paleotemperatures. Paleoceanography 14, 698–705 (1999).

Cacho, I., Shackleton, N., Elderfield, H., Sierro, F. J. & Grimalt, J. O. Glacial rapid variability in deep-water temperature and δ18O from the Western Mediterranean Sea. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 3294–3311 (2006).

Rodrigo-Gámiz, M. et al. Sea surface temperature variations in the western Mediterranean Sea over the last 20kyr: a dual-organic proxy (UK′37and LDI) approach. Paleoceanography 29, 87–98 (2014).

Bard, E., Rostek, F., Turon, J.-L. & Gendreau, S. Hydrological impact of Heinrich events in the subtropical northeast Atlantic. Science 289, 1321–1324 (2000).

Camuera, J. et al. Orbital-scale environmental and climatic changes recorded in a new ∼200,000-year-long multiproxy sedimentary record from Padul, southern Iberian Peninsula. Quat. Sci. Rev. 198, 91–114 (2018).

Fletcher, W. J., Sánchez-Goñi, M. F., Peyron, O. & Dormoy, I. Abrupt climate changes of the last deglaciation detected in a Western Mediterranean forest record. Climate 6, 245–264 (2010).

Combourieu Nebout, N. et al. Rapid climatic variability in the west Mediterranean during the last 25,000 years from high resolution pollen data. Climate 5, 503–521 (2009).

Skonieczny, C. et al. Monsoon-driven Saharan dust variability over the past 240,000 years. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav1887 (2019).

McGee, D., deMenocal, P. B., Winckler, G., Stuut, J. B. W. & Bradtmiller, L. I. The magnitude, timing and abruptness of changes in North African dust deposition over the last 20,000yr. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371-372, 163–176 (2013).

Kinsley, C. W. et al. Orbital- and millennial-scale variability in Northwest African dust emissions over the past 67,000 years. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 37, 4137 (2021).

Niedermeyer, E. M. et al. Orbital- and millennial-scale changes in the hydrologic cycle and vegetation in the western African Sahel: insights from individual plant wax δD and δ13C. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 2996–3005 (2010).

Kuechler, R. R., Schefuß, E., Beckmann, B., Dupont, L. & Wefer, G. NW African hydrology and vegetation during the last glacial cycle reflected in plant-wax-specific hydrogen and carbon isotopes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 82, 56–67 (2013).

Küchler, R. R. A Revised Orbital Forcing Concept of West African Climate And Vegetation Variability During the Pliocene and the Last Glacial Cycle, PhD thesis. (University of Bremen, 2015).

Tjallingii, R. et al. Coherent high- and low-latitude control of the northwest African hydrological balance. Nat. Geosci. 1, 670–675 (2008).

Giresse, P., Maley, J. & Brenac, P. Late Quaternary palaeoenvironments in the Lake Barombi Mbo (West Cameroon) deduced from pollen and carbon isotopes of organic matter. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 107, 65–78 (1994).

Giresse, P., Maley, J. & Kelts, K. Sedimentation and palaeoenvironment in crater lake Barombi Mbo, Cameroon, during the last 25,000 years. Sediment. Geol. 71, 151–175 (1991).

Maley, J. et al. Lithostratigraphy, volcanism, paleomagnetism and palynology of Quaternary lacustrine deposits from Barombi Mbo (West Cameroon): preliminary results. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 42, 319–335 (1990).

Lebamba, J., Vincens, A. & Maley, J. Pollen, vegetation change and climate at Lake Barombi Mbo (Cameroon) during the last ca. 33000cal yr BP: a numerical approach. Climate 8, 59–78 (2012).

Maley, J. & Brenac, P. Vegetation dynamics, palaeoenvironments and climatic changes in the forests of western Cameroon during the last 28,000years B.P. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 99, 157–187 (1998).

Lézine, A.-M. & Cazet, J.-P. High-Resolution Pollen record from Core KW31, Gulf of Guinea, Documents the History of the Lowland Forests of West Equatorial Africa since 40,000yr ago. Quaternary Res. 64, 432-443 (2005).

Acknowledgements

J.C. acknowledges the postdoctoral contract from the Junta de Andalucía (DGP_POST_2024_00267). This work has been also supported by the projects PID2021-125619OB-C21 and PID2021-125619OB-C22 funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/Agencia Estatal de Investigación/10.13039/501100011033, and by the research group RNM-190 (Junta de Andalucía). Thanks to the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions to improve the article. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT-3.5 to review grammar and improve the readability of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and H.S. conceptualized the study, developed the quantitative reconstructions, collected other proxy data and performed the initial interpretations and discussions of the manuscript. E.A. and P.V. provided the climate simulation data, and help with the simulation vs proxy data interpretations. L.R. developed the codes for the SnSizer statistical analysis. F.J.-E., G.J.-M., A.G.-A., and M.T. assisted in the interpretation of hydrological proxy records. All authors contributed to the writing, editing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: ChenRui Diao, and Aliénor Lavergne. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Camuera, J., Armstrong, E., Valdes, P. et al. Occurrence of Heinrich stadials in the West Mediterranean and West African regions and their connections to atmospheric circulation changes. Commun Earth Environ 7, 94 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03103-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03103-5