Abstract

Tropical Indian Ocean warming has intensified under greenhouse forcing, yet its influence on North American terrestrial and agricultural productivity remains poorly understood. Here we show that summer tropical Indian Ocean warming is linked to widespread drying and reduced gross primary productivity across North America. Observations and model simulations reveal that tropical Indian Ocean-induced atmospheric heating excites stationary Rossby wave trains, which establish a high-pressure ridge over western North America and suppresses moisture transport into the continent. This leads to reduced precipitation and soil moisture, leading to 10-20% reductions in terrestrial productivity and crop yields. The relationship persists after excluding El Niño–Southern Oscillation years and is reproduced in multiple climate models, showing robust teleconnection processes. These results highlight a previously underappreciated pathway through which tropical Indian Ocean warming can weaken the North American land carbon sink under future climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Terrestrial gross primary productivity (GPP) plays a critical role in modulating the global carbon cycle and climate, yet it is highly sensitive to hydroclimatic variability1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, particularly under anthropogenic warming8,9,13. In North America, interannual variability in terrestrial3,5,12,15,21,22 and agricultural productivity21,22,23,24,25,26,27 is strongly regulated by temperature2,8,13,21, precipitation15,16,18, and soil moisture14,21,24 variability, which directly affects photosynthesis, soil respiration, and water availability during the growing season. These changes affect not only the continental carbon sink but also agricultural yields23, food security, and ecosystem stability.

Several large-scale climate modes are known to modulate North American hydroclimate and terrestrial productivity through atmospheric teleconnections2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO)7,9,10,11,28,29,30,31 is a dominant driver, shaping precipitation and temperature anomalies across the continent. El Niño events typically generate warm and dry conditions in the southern United States, whereas La Niña tends to produce cooler and wetter anomalies, leading to contrasting ecosystem responses. The North Atlantic Oscillation7,32,33,34 also influences storm tracks and atmospheric circulation, especially during winter and spring. In addition, Arctic amplification and associated sea-ice loss weaken the pole–midlatitude temperature gradient8, increasing the persistence of jet stream meanders and the risk of heatwaves and droughts in mid-latitude North America. These processes have been linked to significant reductions in both GPP and crop yields. Rapid Arctic sea-ice loss and Arctic amplification have been shown to modify mid-latitude atmospheric circulation by weakening the meridional temperature gradient, altering jet-stream pathways, and increasing the persistence of planetary-wave anomalies35,36. These mechanisms can contribute to more frequent or prolonged winter cold outbreaks and summer circulation anomalies in the Northern Hemisphere. Moreover, compounding interactions between temperature and moisture extremes further amplify agricultural loss14,21,22,24.

Hydroclimate extremes such as warming and drought have already led to significant yield reductions across the United States21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Maize is particularly sensitive to simultaneous warming and drought during the growing season, whereas soybean and wheat are more strongly affected by severe drought than by temperature increases alone21,24,25,26,27. Moreover, interactions between temperature and moisture extremes often amplify yield losses. The extreme heat reduces yield potential while intensifying water stress, and drought conditions further elevate air temperatures, compounding reductions in crop productivity21,26,27.

While the influence of ENSO, North Atlantic Oscillation, and Arctic amplification on North American productivity is well established, the role of the tropical Indian Ocean (TIO) has received little attention. The TIO has experienced pronounced and sustained warming over recent decades, largely driven by greenhouse forcing28,29,30,31,32,33,34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. This warming alters tropical convection and generates stationary Rossby wave trains that can propagate into the extratropics, thereby modulating remote hydroclimatic conditions. Although the TIO has been recognized as a driver of global teleconnections—including its impacts on Pacific variability and the monsoon system30,31,43,44,45,46,47. However, its role in modulating North American productivity remains poorly understood. Anomalous diabatic heating over the TIO can generate stationary Rossby waves that propagate into the extratropics, modulating circulation and hydroclimate in remote regions. For example, ENSO strongly influences North America through teleconnection patterns such as the Pacific–North America mode, which is associated with warmer winter conditions in the western United States44,45,46. Likewise, the Arctic Oscillation and sea-ice loss modulate large-scale atmospheric circulation, enhancing warm-air advection and contributing to elevated temperatures across the continent47. However, the potential influence of TIO warming on North American terrestrial carbon uptake and agricultural productivity remains poorly understood.

Addressing this gap is critical because hydroclimate extremes such as heatwaves and droughts are projected to intensify under greenhouse warming, posing growing risks to the North American land carbon sink and food production systems. Here, we investigate how summer TIO warming affects North American terrestrial and agricultural productivity through large-scale atmospheric teleconnections. Using observational datasets, reanalysis products, and climate model experiments, we demonstrate that TIO-induced warming excites Rossby wave responses that lead to summer drying, suppressed soil moisture, and reduced GPP and crop yields across North America. Our findings reveal a previously underappreciated pathway linking tropical ocean warming to terrestrial productivity decline under climate change.

Results

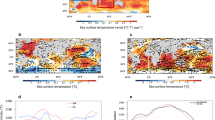

In this study, the tropical Indian Ocean (TIO) index is uniformly defined as the July–August mean sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly averaged over 20°S–20°N and 40°E–100°E (outlined in the red box in Fig. 1). We conducted correlation analyses between TIO and GPP, temperature, precipitation, and soil moisture during 1982–2018 to ensure the robustness of their relationship. The relationship between the TIO index and North American GPP anomalies is strong and statistically significant (r = 0.53–0.66, p < 0.001). Similar results are obtained for precipitation and soil moisture, supporting the physical robustness of the findings. The correlations also remain relatively stable with increasing lead time (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

a Partial correlations between the TIO index and climate variables (2-m temperature, precipitation, and soil moisture), as well as GPP with and without Niño 3.4 index over North America (100°–70° W, 30°–55° N) during July–August mean data for 1982–2018. Red markers represent partial correlations without Niño 3.4 and green markers Niño 3.4 index. b Observed linear trends (1950–2020) in annual-mean sea surface temperature (SST; °C per 71 years). The red box indicates the region where the TIO index is defined. c Climatological monthly TIO index (brown bars) and monthly TIO anomalies in 2015 (gray bars) from observations. d Same as (c), but for NIR-based GPP. In (c, d), the black line denotes ±1 standard deviation of monthly TIO.

To statistically isolate the influence of the TIO from ENSO variability, we further performed partial correlation analyses controlling for the Niño 3.4 index (Fig. 1a). The partial correlation between TIO SST and North American GPP remains robust (partial r = –0.56, p < 0.001), indicating that the TIO–GPP linkage is largely independent of ENSO influences. Similar relationships were found for precipitation, temperature, and soil moisture.

To assess whether the TIO–North American climate correlation exceeds the range of unforced internal variability, we performed a bootstrap resampling test using 200-year CESM1.2 control simulations (10,000 resamples). The resulting correlation distribution (mean r = –0.59 ± 0.22) falls well outside the range of internal variability, confirming the statistical robustness of the TIO–North America teleconnection (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e).

Seasonal analysis shows a link between TIO and North American productivity. In 2015, both the TIO warming and the reduction in GPP exceeded one standard deviation (Fig. 1c, d). To evaluate the role of hydrological changes, we examined soil moisture anomalies (Fig. 1a). During TIO warming years, soil moisture indicates persistent dryness, with a correlation coefficient of 0.54 (p < 0.001) against the TIO index. This association persists even after excluding ENSO years. Together, these results suggest that reduced precipitation during TIO warming contributed to drought conditions, thereby lowering terrestrial and agricultural productivity across North America. Overall, our analysis suggests that variability in the Indian Ocean has a remarkable impact on North American climate and land carbon dynamics.

Reduction in terrestrial primary productivity due to tropical Indian Ocean forcing

To quantify the influence of the tropical Indian Ocean on terrestrial GPP across North America, we have conducted regression analyses using multiple datasets. Our data sources include satellite-based near infrared reflectance (NIR) data as a proxy for GPP, and GPP data derived from an improved light use efficiency model (LUEM). The results of our regression analysis provide compelling evidence for a potential link between terrestrial GPP over North America and the tropical Indian Ocean. In the NIR dataset, we observe strong negative vegetation anomalies in the central and eastern US, as well as south of Canada. Conversely, we identify moderately positive terrestrial GPP in northeastern Canada and Alaska (Fig. 2a). The regions with the most negative regression coefficients are found in the central and northern United States and eastern Canada, while western Canada shows weakly positive GPP anomalies. The LUEM model confirms these patterns related to the Indian Ocean, showing relatively stronger regression coefficients ranging from 40 to 50 gC m−2 month−1 in the eastern part of the US. However, it notably exhibits an eastward and southward extension of the negative coefficients over the United States (Supplementary Fig. 2) compared with those in NIR. In Alaska, LUEM shows an increase in GPP associated with TIO warming, a pattern inconsistent with the NIR-based GPP response, suggesting substantial uncertainty in GPP responses in this region.

a Composite difference in observed July–August GPP from NIR (gC m−2 month−1) between TIO warming years (>+0.5 s.d.) and cooling years (<−0.5 s.d.), after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 variability, for 1982–2018. Dotted areas indicate regions significant at the 95% confidence level based on a Student’s t-test. b Composite difference in July–August GPP between TIO + 0.5 °C and TIO − 0.5 °C model experiments, after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 index. c Statistics of simulated North American GPP anomalies during TIO warming and cooling experiments. Bars indicate ensemble mean GPP, and open circles show values from individual ensemble members.

To investigate causality, we have employed “the Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology Earth System Model, version 3.0 (NESM3.0, see “Methods”) in our study. To assess the impact of the TIO SST on terrestrial productivity across North America, we conducted an idealized simulation using the NESM3.0 model. In this simulation, we have performed a pre-industrial control run (TIO + 0 °C) as a reference. We also introduce a nearly uniform increase of +0.5 °C to the climatological SST in the tropical Indian Ocean region, denoted TIO + 0.5 °C. Conversely, we implement a decrease in SST of −0.5 °C, denoted TIO − 0.5 °C. Figure 2b illustrates the differences in the GPP between TIO − 0.5 °C and TIO + 0.5 °C. The model results effectively reproduce the observed reduction in terrestrial productivity over North America due to TIO warming. Note that the model differs slightly in simulating the magnitude of reduced GPP, with a slightly smaller reduction compared to the observations.

To further confirm the robustness of the suppressive effect of TIO warming on North American terrestrial productivity, we have conducted three additional sensitivity model experiments with a doubling (TIO + 1 °C) and stronger TIO warming (TIO + 1.5 °C) using ensemble simulations (see “Methods” and Supplementary Table 1). The results of the ensemble simulations have an overall accuracy of more than 95%. They show a significant negative correlation between TIO and the response in GPP (Fig. 2c), which is consistent with the observations made in the comparison between the TIO − 0.5 °C and TIO + 0.5 °C experiments. The difference in GPP for a 1 °C increase in TIO warming is 30–50 gC m−2 month−1, which corresponds to approximately 10–24% of the mean summer GPP over the last three decades. This decrease is particularly pronounced in regions experiencing substantial soil moisture deficits. In summary, the warming of the tropical Indian Ocean leads to a decrease in land productivity and carbon sequestration, primarily due to its influence on North American climate conditions.

Mechanisms linking tropical Indian Ocean forcings to the North American climate

The reduction in North American GPP during TIO warming can be explained by large-scale atmospheric teleconnections initiated in the tropics. Basin-wide TIO warming enhances deep convection and diabatic heating in the equatorial Indian Ocean (Supplementary Fig. 3). This localized heating anomaly acts as a Rossby wave source that excites a stationary wave train that propagates into the extratropics along great-circle routes. Composite analyses of sea level pressure and upper-tropospheric geopotential height anomalies confirm this mechanism: during TIO warm years, a barotropic high-pressure ridge forms over northwestern Canada and the western United States, while a corresponding low develops over the southeastern United States (Fig. 3a, b). This dipole structure is consistent with theoretical expectations of Rossby wave propagation and has been linked to surface drying in previous studies.

a, b Composite differences in observed July–August geopotential height (a, m) and sea level pressure (b, Pa) between TIO warming years (> +0.5 s.d.) and cooling years (<−0.5 s.d.), after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 variability. c, d Same as (a, b), but for differences between TIO + 0.5 °C and TIO − 0.5 °C model experiments, after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 index. Dotted areas indicate regions significant at the 95% confidence level based on a Student’s t test.

Climate model experiments further confirm these adjustments in circulation. Simulations comparing warm (TIO + 0.5 °C) and cold (TIO − 0.5 °C) conditions reproduce the observed wave train extending from the tropical Indian Ocean across the North Pacific and into North America (Fig. 3c, d). The modeled teleconnection exhibits a coherent three-dimensional structure, with high geopotential height anomalies in the mid-to-upper troposphere, and produces associated surface pressure anomalies. Although the simulated response shows a modest eastward displacement and stronger anomalies over the Arctic, the overall pattern aligns closely with reanalysis data. Long-term CESM1.2 experiments support that this Rossby wave response is primarily driven by Indian Ocean forcing, rather than internal atmospheric variability (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The circulation anomalies have pronounced impacts on North American moisture transport. During warm TIO events, the anomalous ridge over western North America strengthens northerly winds across the Great Plains and Midwest. This configuration reduces northward moisture transport from the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, while promoting advection of dry continental air from Canada (Fig. 4a). At the same time, the anomalous low over the southeastern U.S. enhances cyclonic circulation and moisture convergence locally, but this does not compensate for the widespread drying in the continental interior. The net result is a reduction in precipitation across central North America (Fig. 4b) and significant root-zone soil moisture deficits (Fig. 4c).

a Composite differences in observed moisture advection (g kg⁻¹ s⁻¹, shading), geopotential height (m, contours), and winds (m s⁻¹, vectors) at 850 hPa during July–August between TIO warming years (>+0.5 s.d.) and cooling years (<−0.5 s.d.) for 1982–2018, after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 variability. b Same as (a), but for precipitation (mm day−1, shading). c Same as (b), but for root-zone soil moisture (m³ m−³, shading). d–f Same as (a–c), but for differences between TIO + 0.5 °C and TIO − 0.5 °C model experiments, after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 index.

Model experiments with imposed TIO SST anomalies show consistent hydroclimate responses. Increased TIO warming induces high-pressure anomalies over the western and central United States, suppressing moisture inflow from the Gulf and reducing precipitation (Fig. 4d, e). This leads to persistent soil moisture decline (Fig. 4f), closely matching observational estimates. While the simulated anomalies are somewhat weaker and displaced eastward relative to observations, the key physical processes are well reproduced, confirming the causal link between TIO warming and continental drying. Land–atmosphere feedback further amplifies these anomalies. Reduced rainfall limits soil moisture recharge, lowering evapotranspiration rates and suppressing boundary-layer convection. This feedback leads to reduced cloud formation and enhanced surface heating, which in turn reinforces drought conditions. Persistent deficits from spring (Supplementary Fig. 5) exacerbate summer drought severity, while lower evaporation rates during TIO warming years (Supplementary Fig. 6) contribute to prolonged soil moisture depletion. These coupled processes explain why even modest SST anomalies in the TIO can trigger substantial reductions in terrestrial productivity across North America.

Impact of greenhouse warming on tropical Indian Ocean – North America terrestrial activities

Greenhouse warming is widely recognized to enhance terrestrial productivity in North America, as indicated by observational and climate model studies6,8,9,13. This suggests that the suppressive effects of TIO warming on North American productivity may be mitigated under greenhouse warming conditions. To test this hypothesis, we have conducted two additional model simulations. In the first simulation, we have abruptly quadrupled carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations (referred to as 4XCO2). In the second simulation, we also quadruple CO2 concentrations but maintain pre-industrial climatological SST over the TIO region (4XCO2+TIOclim). Under 4×CO2 forcing, GPP increases by approximately 30–40 gC m⁻² month⁻¹. When the TIO warming component is suppressed (4×CO2 + TIOclim), the increase becomes larger (55–70 gC m⁻² month⁻¹), indicating that TIO warming exerts a suppressing effect on North American GPP even under greenhouse-warming conditions. Analysis of these simulations shows that TIO warming reduced anomalies in the region and enhanced surface northeasterly winds over North America, resulting in a precipitation deficit (see Supplementary Fig. 5). These processes are similar to those in models with pre-industrial CO2 forcing (TIO + 0.5 °C and TIO − 0.5 °C), suggesting that the inhibitory effect of TIO warming on North American GPP persists under greenhouse warming conditions, although the underlying mechanisms are different in a warmer background climate.

To further compare the reduction in GPP due to TIO warming under different climate conditions, specifically greenhouse warming and the present climate, we have conducted two additional experiments. In the first experiment, we use current CO2 concentrations (PD). In the second experiment, we use current CO2 concentrations while imposing pre-industrial climatological SST in the tropical Indian Ocean (referred to as PD + TIOclim). We then calculate the GPP reduction due to TIO warming under present CO2 conditions (defined as “TIO + OBS” minus TIO + clim). Our results show that the GPP reduction due to TIO warming under current CO2 conditions is significantly smaller than under greenhouse warming scenarios, with a GPP difference of about 5–8 gC m−2 month−1 (Fig. 5). These results suggest the critical importance of accurately representing and modeling future TIO warming in Earth system models. Ensuring the accuracy of these models is essential to reducing uncertainties in the prediction of North American GPP in the context of a dynamically changing climate.

The evolution of North American GPP (gC m−2 month−1) in the model experiments includes several scenarios: quadrupling of CO2 (4×CO2), quadrupling of CO2 with preindustrial mean TIO SST (4×CO2+TIOclim), present-day CO2 levels (PD), and present-day CO2 with preindustrial mean TIO SST (PD+TIOclim). Perturbations are introduced at time zero and maintained throughout the experiments. A 5-year running mean is applied to all the curves. The thick line indicates average values, while shading represents the ensemble spread over 50 years.

Role of Pacific on tropical Indian Ocean–North America terrestrial activities

The Indian Ocean has experienced sustained warming in recent decades, and its interactions with other ocean basins suggest potential impacts on SST patterns in the Pacific and North Atlantic. To assess whether Pacific SST changes can offset the reduction in North American GPP caused by Indian Ocean warming, we conducted two model simulations: (1) TIO + OBS, and (2) TIO + OBS + PA. In the first simulation (TIO + OBS), observed SST data were prescribed only over the Indian Ocean. In the second simulation (TIO + OBS + PA), observed SST data were applied to the Indian Ocean, while climatological SSTs were imposed over the Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 7). Our results show that when both tropical Indian and Pacific SST anomalies are included, the reduction in North American GPP is weaker than in the simulation forced by Indian Ocean anomalies alone (TIO + OBS). The absence of observed Pacific SST anomalies tends to induce anomalous low-pressure systems and associated cyclonic surface winds over the United States, thereby enhancing moisture transport from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea into central and eastern regions. Notably, other Pacific SST patterns show no statistically significant relationship with North American GPP (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results suggest that the negative impact of Indian Ocean warming on North American GPP can be partially mitigated through interbasin interactions with the Pacific. This highlights the importance of accounting for coupled oceanic dynamics when evaluating future terrestrial productivity and regional climate responses.

Impact of tropical Indian Ocean on US crop yield

The tropical Indian Ocean may affect crop yields because it significantly modifies air temperature, atmospheric circulation, and precipitation over the US region during the vegetative growing season. We investigate whether the TIO affects total US crop yields, as assessed using the bootstrap method (see “Methods”). We select representative crops, wheat and corn, that are strongly influenced by climatic conditions, although they are also affected by human activities, including crop management practices. The results show that wheat yields decrease during TIO warming periods but increase during TIO cooling periods, especially over the U.S. Great Plains. During TIO warming periods, crop yield anomalies decline by about 33.2 Mt (megatons), whereas during cooling periods they rise by about 14.1 Mt. This difference is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level according to a bootstrap method (Fig. 6a). The decrease in crop yields with TIO warming is partly consistent with the decline in terrestrial GPP over the USA. For corn, significant negative changes are observed in Nebraska, Kansas, Ohio, New York, and Kentucky. Although wheat yield changes associated with anomalous TIO warming are generally negative across most regions, North Dakota shows positive changes, which may be explained by human activities and other local factors.

Distribution of yield anomalies for wheat (a) and corn (b) during periods of tropical Indian Ocean (TIO) warming (blue, > +0.5 s.d.) and cooling (orange, < −0.5 s.d.) from 1982 to 2018, after removing the effect of Niño 3.4 variability. The analysis is based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples, which provides a robust statistical assessment of the TIO-US yield relationship. Box-and-whisker plots indicate the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum values for each condition.

We also assessed changes in corn yields at the US state level in response to TIO warming. For this analysis, we compiled annual corn yield data for major US states, focusing on years with relatively strong positive TIO SST anomalies. The results show substantial variations in crop yields associated with TIO warming (Fig. 6b). The maximum reductions in corn yields reach about −70 Mt (≈20–35% of the mean yield levels; Supplementary Fig. 9). The median reduction falls within the range of −5 to −13 Mt over the past three decades.

Furthermore, we examined the composite difference in corn yields between TIO warm and cold years (Supplementary Fig. 9). This analysis was restricted to years when TIO anomalies exceeded one standard deviation of the TIO index. The resulting changes in wheat and corn yields amount to about 8–30% of the climatological annual yields for US states. These results suggest that the TIO index may be a useful predictor for estimating near-future crop yields, a topic that warrants further investigation.

Discussion

This study reveals a significant negative relationship between tropical Indian Ocean (TIO) warming and vegetation activity, including agricultural productivity, in North America. Both observations and model experiments consistently show that TIO warming can reduce the U.S. land carbon sink by 15–20% and reduce state-level crop yields by 5–20%. These findings provide robust evidence that the TIO is an important but previously underappreciated driver of North American hydroclimate and ecosystem variability.

To test model dependence, we compared our results with GPP simulations from the Multi-scale Synthesis and Terrestrial Model Intercomparison Project. Across 36 models with different forcings, most simulations reproduce negative GPP anomalies during TIO warming, with more than 85% of models showing statistically significant coefficients comparable in magnitude to the observations (Supplementary Fig. 10). This multi-model agreement highlights the robustness of the TIO–North America teleconnection.

Our results underscore the critical need to incorporate TIO conditions into Earth system models and seasonal-to-decadal prediction frameworks when assessing terrestrial productivity and crop yields. The Indian Ocean has warmed faster than the global mean over the past half-century, and continued warming increases the likelihood of widespread vegetation and agricultural losses. Under greenhouse forcing, North American GPP trends are strongly influenced by local temperature; however, uncertainties in future productivity can partly be attributed to projected TIO warming. Accurate representation of TIO variability and long-term warming in Earth system models is therefore critical for reliable prediction of regional carbon cycle dynamics and agricultural risks. In summary, this study reveals a robust pathway through which TIO warming weakens the North American land carbon sink and agricultural productivity. These findings not only improve our understanding of tropical–extratropical climate interactions but also provide actionable insights for improving food security assessments under climate change.

Although our analyses identify a robust TIO–North America teleconnection, a comprehensive cross-basin comparison involving coordinated pacemaker experiments across the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans is still lacking. Future studies should explicitly address interbasin coupling mechanisms using such targeted experiments19,48.

Methods

Diagnosis of the observed data

We used the period 1982–2018, which corresponds to the availability of near-infrared reflectance (NIR)–based GPP data and ensures maximum overlap with other high-quality datasets such as ERA-Interim reanalysis, GLEAM soil moisture, and USDA crop yield data. Although some datasets extend beyond this range, we restricted the analysis to this common period to guarantee consistency across variables. For regression and correlation analyses, we focused on July–August, which corresponds to the peak of TIO SST anomalies during the growing season. We used the 1982–2018 period, representing the longest interval with reliable and overlapping coverage of ERA-Interim and USDA crop yield statistics. Data prior to 1982 exhibit inhomogeneities, while post-2018 coverage is not uniformly available across all variables. This choice provides a balance between data length and consistency.

To obtain the monthly mean SST, we used the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Extended Reconstructed SST version 5 (ERSST)49. Near-surface temperature, wind, sea-level pressure, and geopotential height are obtained from the ERA-Interim50,51 (http://apps.ecmwf.int/datasets/data/interim-full-moda). For near-surface temperature and precipitation, we used Climatic Research Unit (CRU) TS3.2349 (http://www.cru.uea.ac.uk). The tropical Indian Ocean (TIO) index is defined as the averaged SST anomaly over 20°S–20°N, 40°–100°E, during July–August, following the region showing the strongest SST warming trend over the past seven decades (see Fig. 1b). For evaporation and soil moisture, we used the GLEAMv3.7 data (https://www.gleam.eu). We used the LUEM data- GPP modeled at 8 km spatial resolution for each of the 35 years, which are available from 1982 to 201652. For the GPP over land, we used near-infrared reflectance (NIR) (gC m−2 month−1), which is based on vegetation absorbing blue- and red-light energy to fuel photosynthesis53,54. Additionally, the GPP is based on the well-known Monteith light use efficiency (LUE) equation but was improved with optimized spatially and temporally explicit LUE values derived from selected FLUXNET tower site data55. We used United States crop-yield national and state-level data from “Quick Stats 2.0” website, which is provided by the National Agricultural Statistics Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (http://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats).

Earth system model

We used the third version of the Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology Earth System Model (NESM3.0)48,56,57,58,59, which includes fully coupled atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and land components through an explicit coupler. The atmospheric model has a horizontal resolution of ~1.9° × 1.9° with 47 vertical levels extending into the stratosphere. The ocean model has a grid resolution of 1°, with a meridional resolution refined to 1/3° over the equatorial region. The model uses 46 vertical layers, with the upper 15 layers being in the top 100 m. NESM3.0 simulated a reasonable climatology with the key characteristics of climate variabilities. The NESM includes the JSBACH3 land surface scheme. This represents energy, water, and carbon exchanges between the land surface and the atmosphere. It incorporates multi-layer soil hydrology, snow dynamics, and vegetation processes based on plant functional types, allowing for realistic simulation of photosynthesis, transpiration, and carbon storage. Sub-grid tiling accounts for land-surface heterogeneity, and all components are fully coupled to the atmospheric model, ensuring physically consistent interactions within the Earth system framework. This could simulate the interannual variability of the GPP and ecosystem60,61,62.

For the long-term simulations, we employed the Community Earth System Model version 1.2 (CESM1.2)61,62,63,64 large ensemble to investigate climate responses under a CO₂ overshoot pathway. CESM1.2 is a state-of-the-art Earth system model developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The model configuration consists of the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5), the Community Land Model (CLM4.5), the Parallel Ocean Program (POP2), and the Los Alamos Sea Ice Model (CICE4). All simulations were performed with a horizontal resolution of approximately 1° and 30 vertical atmospheric levels. The model was integrated with pre-industrial forcing for 800 years, and the last 200 years of output were used for analysis.

Sensitivity of the TIO over North America on climate and terrestrial productivity

To investigate the response of North American GPP to changes in tropical Indian Ocean SST, we conducted idealized simulations using pre-industrial forcings. Only the ocean model of NESM3.0 was integrated for 4000 years with atmospheric forcings to elucidate the stable initial conditions of the upper and deep oceans. Second, NESM3.0 was integrated for 500 years, with an initial condition that 4000 years of ocean simulation would be performed with preindustrial forcings based on the CMIP6 protocol, to obtain an initial condition with a stable equilibrium state between the atmosphere and ocean, and the last 50 years of data are used for reference (“TIO + 0 °C”). In TIO + 0.5 °C, the model was simulated with the tropical Indian Ocean SST climatology warmer than in the pre-industrial control run by 0.5 °C. Similarly, sensitivity simulations “TIO + 1 °C”, “TIO + 1.5 °C”, and “TIO − 0.5 °C” represent a TIO warming of 1 °C, 1.5 °C, and cooling of 0.5 °C, respectively.

To estimate the effect of greenhouse warming on North America’s GPP-TIO interaction, we conducted four additional experiments. In PD, we used the present CO2 concentration. PD+TIOclim is the same as PD, but TIO SST employed the pre-industrial climatology. In 4×CO2, we abruptly quadrupled CO2 concentrations from TIO + 0 °C (preindustrial CO2 concentration). 4×CO2 + TIOclim is the same as 4×CO2, but TIO SST employed the pre-industrial climatology.

To further assess the influence of the Pacific SST anomalies on the North American GPP–TIO interaction, we conducted two additional simulations. In TIO + OBS, the models were forced with observed SST anomalies in the tropical Indian Ocean. In TIO + OBS + PA, observed SST anomalies were prescribed over the Indian Ocean, while climatological SSTs were imposed over the Pacific. The significance of differences between the TIO + 0.5 °C and TIO–0.5 °C conditions was evaluated using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov two-sample test. All simulations were integrated for 50 years, and the experimental designs are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Bootstrap methods

A bootstrap resampling approach was employed to assess the robustness of the composite crop yield anomalies associated with TIO warming and cooling events. Years with TIO indices exceeding +1 standard deviation (s.d.) were classified as warming years, and those below –1 s.d. as cooling years. The crop yield anomalies during these years were randomly resampled, with replacement, to generate 10,000 realizations of the mean response. This procedure was repeated for both the corn and wheat crop yields. The standard deviation of the 10,000 bootstrap realizations was then used to estimate the uncertainty of the composite mean response. Similarly, we performed a bootstrap resampling test using a 200-year pre-industrial control simulation from CESM1.2 (10,000 resamples) to evaluate whether the simulated correlation between TIO and North American climate exceeds the range of unforced internal variability. For each resampling, monthly anomalies were randomly drawn with replacement to compute the partial correlation between the TIO index and North American hydroclimate variables, both with and without controlling for ENSO. The resulting distribution of partial correlation coefficients provides a quantitative measure of the statistical significance and robustness of the modeled TIO–North America linkage.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All observed data used in this study are publicly available (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/ data.20thC_ReanV3.html; https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html). The data can be downloaded from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30813968.

Code availability

The codes used in this study can be downloaded here: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30813968.

References

Wang, J. et al. Modulation of land photosynthesis by the Indian Ocean Dipole: satellite-based observations and CMIP6 future projections. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001942 (2021).

Madani, N. et al. Recent amplified global gross primary productivity due to temperature increase is offset by reduced productivity due to water constraints. AGU Adv. 1, 180 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Regional contribution to variability and trends of global gross primary productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 105005 (2017).

Bi, W. et al. A global 0.05° dataset for gross primary production of sunlit and shaded vegetation canopies from 1992 to 2020. Sci. Data. 9, 213 (2022).

Baker, I., Denning, S. & Stöckli, R. North American gross primary productivity: regional characterization and interannual variability. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 62, 533–549 (2010).

Campbell, J. et al. Large historical growth in global terrestrial gross primary production. Nature 544, 84–87 (2017).

Parazoo, N. C. et al. Influence of ENSO and the NAO on terrestrial carbon uptake in the Texas-northern Mexico region. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 1247–1265 (2015).

Kim, J. S. et al. Reduced North American terrestrial primary productivity linked to anomalous Arctic warming. Nat. Geosci. 10, 572–576 (2017).

Kim, J. S., Kug, J. S. & Jeong, S. J. Intensification of terrestrial carbon cycle related to El Niño–Southern Oscillation under greenhouse warming. Nat. Commun. 8, 1674 (2017).

Kim, J. S., Kug, J. S., Yoon, J. H. & Jeong, S. J. Increased atmospheric CO2 growth rate during El Niño driven by reduced terrestrial productivity in the CMIP5 ESMs. J. Clim. 29, 8783–8805 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Contrasting carbon cycle responses of the tropical continents to the 2015 El Niño. Science 358, eaam5690 (2017).

Zhou, S. et al. Dominant role of plant physiology in trend and variability of gross primary productivity in North America. Sci Rep 7, 41366 (2017).

Mekonnen, Z. A., Grant, R. F. & Schwalm, C. Contrasting changes in gross primary productivity of different regions of North America as affected by warming in recent decades. Agric. For. Meteorol. 218–219, 50–64 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Detecting drought impact on terrestrial biosphere carbon fluxes over the contiguous United States with satellite observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 095003 (2018).

Ritter, F., Berkelhammer, M. & Garcia-Eidell, C. Distinct response of gross primary productivity in five terrestrial biomes to precipitation variability. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 34 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Increasing sensitivity of dryland vegetation greenness to precipitation due to rising atmospheric CO. Nat. Commun. 13, 4875 (2022).

Jiao, W. et al. Observed increasing water constraint on vegetation growth over the last three decades. Nat. Commun. 12, 3777 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Precipitation thresholds regulate net carbon exchange at the continental scale. Nat. Commun. 9, 3596 (2018).

Hu, S. & Fedorov, A. V. Indian Ocean warming can strengthen the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 747–751 (2019).

Hufkens, K. et al. Productivity of North American grasslands is increased under future climate scenarios despite rising aridity. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 710–714 (2016).

Matiu, M., Ankerst, D. P. & Menzel, A. Interactions between temperature and drought in global and regional crop yield variability during 1961–2014. PLoS ONE 12, e0178339 (2017).

Lesk, C. et al. Compound heat and moisture extremes impact global crop yields under climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 872–889 (2022).

Zhang, H., Li, Y. & Zhu, J.-K. Developing naturally stress-resistant crops for sustainable agriculture. Nat. Plants 4, 989–996 (2018).

Santini, M. et al. Complex drought patterns robustly explain global yield loss for major crops. Sci. Rep. 12, 5792 (2022).

Leung, F. et al. CO₂ fertilization of crops offsets yield losses due to future surface ozone damage and climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 074007 (2022).

Schmidt, M. & Felsche, E. The effect of climate change on crop yield anomaly in Europe. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 3, e61 (2024).

Rezaei, E. E. et al. Climate change impacts on crop yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 831–846 (2023).

McPhaden, M., Lee, T. & McClurg, D. El Niño and its relationship to changing background conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15709 (2011).

Chiang, J. C. & Sobel, A. H. Tropical tropospheric temperature variations caused by ENSO and their influence on remote tropical climate. J. Clim. 15, 2616–2631 (2002).

Held, I. M., Lyons, S. W. & Nigam, S. Transients and the extratropical response to El Niño. J. Atmos. Sci. 46, 163–174 (1989).

Klein, S. A., Soden, B. J. & Lau, N.-C. Remote sea surface temperature variations during ENSO: evidence for a tropical atmospheric bridge. J. Clim. 12, 917–932 (1999).

Hu, S. & Fedorov, A. V. Indian Ocean warming as a driver of the North Atlantic warming hole. Nat. Commun. 11, 4785 (2020).

Delworth, T. L. et al. The North Atlantic Oscillation as a driver of rapid climate change in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Geosci. 9, 509–512 (2016).

Hoerling, M. P., Hurrell, J. W. & Xu, T. Tropical origins for recent North Atlantic climate change. Science 292, 90–92 (2001).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Screen, J. A., Bracegirdle, T. J. & Simmonds, I. Polar climate change as manifest in atmospheric circulation. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 383–395 (2018).

Hansen, J., Ruedy, R., Sato, M. & Lo, K. Global surface temperature change. Rev. Geophys. 48, RG4004 (2010).

Du, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Role of atmospheric adjustments in the tropical Indian Ocean warming during the 20th century in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L08712 (2008).

Roxy, M. K., Ritika, K., Terray, P. & Masson, S. The curious case of Indian Ocean warming. J. Clim. 27, 8501–8509 (2014).

Dong, L. & Zhou, T. The Indian Ocean sea surface temperature warming simulated by CMIP5 models during the twentieth century: competing forcing roles of GHGs and anthropogenic aerosols. J. Clim. 27, 3348–3362 (2014).

Han, W. et al. Indian Ocean decadal variability: a review. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 95, 1679–1703 (2014).

Trenberth, K. E. et al. Progress during TOGA in understanding and modeling global teleconnections associated with tropical sea surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 14291–14324 (1998).

Sigmond, M. & Fyfe, J. C. Tropical Pacific impacts on cooling North American winters. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 970–974 (2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Recent contrasting winter temperature changes over North America linked to enhanced positive Pacific–North American pattern. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7750–7757 (2015).

Kushnir, Y., Seager, R., Ting, M., Naik, N. & Nakamura, J. Mechanisms of tropical Atlantic SST influence on North American precipitation variability. J. Clim. 23, 5610–5628 (2010).

Ning, L. & Bradley, R. S. Winter climate extremes over the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada and teleconnections with large-scale modes of climate variability. J. Clim. 28, 2475–2493 (2015).

Hou, Y. et al. A surface temperature dipole pattern between Eurasia and North America triggered by Barents–Kara sea-ice retreat in boreal winter. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 114047 (2022).

Yang, Y.-M. et al. Increased Indian Ocean–North Atlantic Ocean warming chain under greenhouse warming. Nat. Commun. 13, 3978 (2022).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J. & Lister, D. H. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations: the CRU TS3.10 dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 623–642 (2014).

Madani, N., Kimball, J. S. & Running, S. W. Improving global gross primary productivity estimates by computing optimum light-use efficiencies using flux tower data. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 122, 2939–2951 (2017).

Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Ju, W., Qiu, B. & Zhang, Z. Tracking the seasonal and interannual variations of global gross primary production using satellite near-infrared reflectance data. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142569 (2021).

Jung, M. et al. Global patterns of land–atmosphere fluxes of carbon dioxide, latent heat and sensible heat derived from eddy covariance, satellite, and meteorological observations. J. Geophys. Res. 116, G00J07 (2011).

Wang, S. & Zhang, Y. Long-term (1982–2018) global gross primary production dataset based on NIRv. National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (2020).

Huntzinger, D. N. et al. The North American Carbon Program Multi-scale synthesis and Terrestrial Model Intercomparison Project: Part 1. Overview and experimental design. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 2121–2133 (2013).

Yang, Y.-M., An, S.-I., Wang, B. & Park, J.-H. A global-scale multidecadal variability driven by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 1190–1197 (2020).

Yang, Y.-M. et al. Improved historical simulation by enhancing moist physical parameterizations in the climate system model NESM3.0. Clim. Dyn. 54, 3819–3840 (2020).

Yang, Y.-M. et al. Mean sea surface temperature changes influence ENSO-related precipitation changes in the mid-latitudes. Nat. Commun. 12, 1495 (2021).

Thum, T. et al. Soil carbon model alternatives for ECHAM5/JSBACH: evaluation and impacts on global carbon cycle estimates. J. Geophys. Res. 116, G02028 (2011).

Mäkelä, J. et al. Sensitivity of 21st-century simulated ecosystem indicators to model parameters, climate drivers, RCP scenarios, and forest management actions. Biogeosciences 17, 2681–2700 (2020).

Thum, T. et al. Evaluating two soil carbon models within JSBACH using surface and spaceborne CO₂ observations. Biogeosciences 17, 5721–5743 (2020).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5.0). NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-486+STR (2012).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The Community Earth System Model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Y.-M.Y. is supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2025-23524302 and RS-2024-00416848).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-M.Y., S.-I.A., and B.W. conceived the idea. Y.-M.Y. performed the model experiments and analyses. S.-I.A., Y.-M.Y., S.-W.Y., B.W., J.-H.P., and J.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Jinfeng Chang, Somaparna Ghosh, and Aliénor Lavergne [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, YM., Park, JH., Kim, J. et al. Tropical Indian Ocean forcing on North American terrestrial and agricultural productivity decline under greenhouse warming. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1045 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03126-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03126-y