Abstract

Compound floods resulting from the concurrence of river overflow and elevated sea levels are becoming increasingly unpredictable as climate extremes intensify. However, most flood risk assessments still fail to account for the uncertainty in their co-occurrence. Here, we quantify potential coastal compound flood risk at 0.1∘ resolution by integrating flood hazard, population exposure, and empirical vulnerability. Specifically, we introduce a compound flood metric, which aggregates riverine and oceanic flood volumes across multiple return periods under a physically plausible co-occurrence assumption. We further derive an empirical vulnerability function based on the ratio between observed and maximum potential flood hazard. The results show that Asia exhibites the highest 35.22% internal high-risk grids, followed by Africa (20.21%), Europe (17.02%), South America (9.89%), and North America (2.31%), with river deltas and low-lying coasts emerging as global riskhotspots. Our study offers a conservative compound flood risk assessment under deep uncertainty, supporting more robust investment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the face of accelerating sea-level rise and intensifying extreme weather, floods have become the most frequent and destructive natural hazard worldwide1,2,3. Anthropogenic climate change, coupled with widespread land-use modifications, has amplified both the magnitude and recurrence of extreme flood events, resulting in escalating losses of lives and assets4—particularly across Southeast Asia5, where the greatest exposure is observed6,7,8,9. This vulnerability is further exacerbated by rapid urban expansion and unsustainable groundwater extraction in low-lying coastal zones, which accelerate land subsidence and compound the impacts of sea-level rise and storm surges5,10,11. Simultaneously, the degradation of coastal wetlands, a critical buffer against storm impacts, has diminished the natural capacity to trap sediments and dissipate wave energy12,13,14. Together, these intertwined processes have substantially eroded flood resilience worldwide and underscore the critical need for high-resolution risk assessments at a global scale.

Global evidence indicates a high likelihood of concurrent riverine and oceanic flooding in coastal regions, arising from anomalous river discharge and elevated sea levels15,16,17. Such interdependent flood mechanisms give rise to compound flood events that can substantially intensify overall impacts by deepening inundation, prolonging flood duration, and widening the spatial extent of floods18,19,20,21,22. Joint-probability-based approaches have been widely used to quantify the dependence between riverine and oceanic floods globally15,17,18. However, these methods require event selection based on specific flood sources (e.g., storm surges or river overflows), whereas extreme water levels can result from events that are not extreme themselves23,24, which may introduce bias in compound flood estimates. Recent studies have incorporated conditional simulation frameworks into compound flood modeling25,26, without requiring strict event pre-classification. This methodological shift has facilitated the global-delta-scale assessments of compound flood risk27, offering insights into the spatial patterns of compound floods. However, these approaches may underestimate hazard levels in future-oriented decision-making, as emerging extremes are unlikely to be captured by past statistics. From a mechanistic perspective28,29,30, the riverine and oceanic floods under multiple probabilities can plausibly co-occur. This highlights the need for a combined metric that captures the potential volume of compound flooding that coastal communities would need to manage.

In economic terms, flood risk is often expressed as expected annual damage, defined as the integration of socio-economic losses over the full spectrum of flood return periods31,32. As urbanization increasingly expands into flood-prone regions5,33,34, population exposure rises, flood risk assessments that focus solely on economic losses tend to bias estimates toward high-income regions33. In contrast, low-income countries are disproportionately exposed to floods and face greater vulnerability35,36. Accordingly, the hazard-exposure-vulnerability (HEV) framework is commonly employed to assess flood risk37,38,39,40. However, existing global flood risk assessments based on the HEV framework that incorporate population exposure often rely on a single return period, typically the 1-in-100-year event, and a narrow set of indicators (e.g., flood depth or inundation extent)33,41. These approaches can introduce systematic biases in risk estimation: focusing on a single return period neglects both low-frequency and high-frequency catastrophic floods42, while considering inundation extent or depth in isolation may misrepresent the flood volume relevant for flood management43. These limitations underscore the need for a more integrated metric that systematically characterizes the full spectrum of flood hazards.

Exposure and vulnerability are equally critical components of flood risk, given the inherently impact-driven nature of risk assessments. Prior studies have frequently used population as a proxy for flood exposure5,33,40, and in the absence of high-resolution geospatial vulnerability data, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is often adopted as a surrogate for economic vulnerability41,44. This assumption rests on the premise that flood-related economic losses scale with the level of economic development. However, this simplification tends to skew flood risk concentration toward economically developed regions, potentially obscuring vulnerabilities in lower-income areas. Empirical evidence suggests that areas with higher GDP are more likely to invest in flood protection, resulting in more advanced flood defense systems and consequently lower flood-related mortality and economic losses45,46,47. To account for the mitigating effects of economic development on flood risk, some studies have used inverted GDP as a vulnerability indicator41,45. Moreover, recent research also emphasizes that income inequality within high-GDP areas can erode the benefits of economic development, leading to disproportionately high flood impacts even in wealthy nations48,49. These findings highlight the complex and multidimensional nature of vulnerability and underscore the need for data-driven approaches that account for hazard-society interactions to improve the robustness of vulnerability.

Here, we introduce a probability-adjusted compound flood volume (Vpc) metric to represent potential coastal compound flood hazard, which integrates riverine and oceanic flood volumes across multiple return periods under a physically plausible co-occurrence assumption. Secondly, we propose a data-driven vulnerability metric derived from the Vpc-GDP relationship, expressed as the ratio between observed and maximum potential hazard for a given GDP level. Finally, we integrate compound flood hazard, population exposure, and empirical vulnerability to derive the global Potential Coastal Compound Flood Risk (PCCFR) at a 0.1 degree resolution (~10 km at the equator) and then aggregated the results to the subnational scale. To examine how different vulnerability assumptions influence risk estimates, and to validate the performance of our empirical approach, we compare three scenarios: (i) raw GDP (risk-taking), (ii) inverted GDP (risk-averse), and (iii) empirical vulnerability (data-driven risk-neutral). The global mapping of PCCFR serves as an initial screening tool to identify potential compound flood risk hotspots, helping to prioritize regions where more detailed local assessments and adaptive restoration efforts are most urgently required.

Results and discussion

Global mapping of potential coastal compound flood hazard

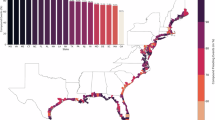

Coastal regions are increasingly susceptible to the simultaneous occurrence of river overflows and storm surges15. Figure 1A–E illustrates the spatial distribution of compound flood hazards across high-risk river deltas, including the Ganges, Pearl, Niger, Mississippi, and Rhine. Figure 1b reveals pronounced spatial heterogeneity in Vpc within deltas. To further disentangle the sources of Vpc, we analyze the probability-adjusted riverine (Vpr) and oceanic (Vpo) flood volumes, alongside their relative contributions (Vpo / Vpr) across these deltas (Fig. 1c–e). As shown in Fig. 1b–d, compound flood exhibits spatial patterns that diverge from those associated with riverine-only or oceanic-only flood events in deltaic hotspots. These spatial discrepancies highlight a key limitation of assessing riverine and oceanic hazards separately, which misrepresents the true extent and dynamics of coastal flood hazards. Neglecting these interactions can substantially underestimate compound flood hazard, especially in low-lying coastal systems. A robust characterization of potential compound flooding for future-oriented decision-making requires an integrated framework that explicitly accounts for the co-occurrence of riverine and oceanic floods.

a The global locations of major deltaic hotspots. A–E Close-up views of five key deltas: the Ganges River Delta, Pearl River Delta, Niger River Delta, Mississippi River Delta, and Rhine River Delta. b–e The deltaic hotspots of probability-adjusted compound flood volume Vpc, probability-adjusted oceanic flood volume (Vpo), probability-adjusted riverine flood volume (Vpr), and their ratio (Vpo/Vpr).

As illustrated in Fig. 1c, d, oceanic floods attenuate gradually inland due to progressive energy dissipation mechanisms compounded by increasing topographic resistance with distance from the shoreline50. Conversely, riverine flood intensity tends to diminish downstream toward the coast, driven by a combination of reduced channel slope and expanding channel width, which collectively lower peak flood magnitudes51. Figure 1e illustrates a spatial gradient in Vpo / Vpr, with an increasing trend from inland to coast. This gradient underscores a fundamental transition in the prevailing flood hazard regime: riverine-driven flooding dominates inland regions, while oceanic influences become increasingly significant closer to the coast. The spatial gradient in flood dominance provides essential guidance for designing targeted and adaptive compound flood management strategies, enabling more effective risk mitigation in vulnerable coastal systems.

Socio-economic exposure to potential coastal compound flood hazard

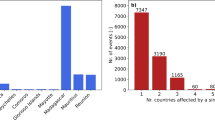

Globally, around 117.19 million people and USD 1.63 trillion in assets are exposed to potential coastal compound flood hazards. To further compare socio-economic exposure to compound and single-source floods, we analyze the conditional distribution of population and assets exposure given five quantiles of riverine (Vpr), oceanic (Vpo), and compound floods (Vpc) (Fig. 2a, b). The results reveal that considering exposure based solely on oceanic floods distorts spatial patterns, overestimating exposure in low-hazard areas (the first quintile, Q1) and underestimating it in high-hazard zones (the fifth quintile, Q5) relative to compound flood scenarios. Similarly, focusing only on riverine floods substantially underestimates socio-economic exposure. These findings underscore the need to integrate multiple flood sources for more accurate, risk-informed decision-making.

a Conditional distribution of population exposure given different quintiles of compound (Vpc), riverine (Vpr), and oceanic (Vpo) flood. b Conditional distribution of economic exposure given different quintiles of compound (Vpc), riverine (Vpr), and oceanic (Vpo) floods. c Country rankings based on the share of high (Vpc) grids. d Country rankings based on the share of population exposed to high (Vpc). e Country rankings based on the share of assets exposed to high (Vpc).

Analysis of the continental distribution of grid cells within Q5-Vpc and their socio-economic exposure reveals that Asia carries the heaviest burden, comprising 54.83% of grid cells within Q5-Vpc and accounting for the largest shares of population (87.29%) and GDP-based asset exposure (49.85%) (Supplementary Fig. 1). At the national level, Fig. 2c–e illustrate that Bangladesh accounts for the largest share of grid cells within Q5-Vpc (14.85%) and the highest population exposure to Q5-Vpc (25.71%), while the Netherlands exhibits the highest share of asset exposure to Q5-Vpc (37.40%). Importantly, several countries exhibit disproportionate exposure relative to their share of grid cells within Q5-Vpc. For example, while the Netherlands holds only 7.31% of grid cells within Q5-Vpc, it accounts for 37.40% of asset exposure. Similarly, Bangladesh hosts 14.85% of grid cells within Q5-Vpc, but contributes 3.92% of asset exposure. These imbalances highlight a key limitation of flood risk assessments based solely on the spatial extent of hazard, which may obscure the underlying socio-economic asymmetries in exposure. We further evaluate the distribution of Q5-hazard grids and associated exposure derived from single-source floods (either riverine or oceanic) at both continental and national levels, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Linking V pc and GDP: a data-driven vulnerability function

Understanding the relationship between Vpc and GDP is essential for accurately quantifying the influence of economic development on hazard, as well as assessing the potential return of flood management. Figure 3 illustrates a scale-dependent relationship between Vpc and GDP: at the subnational level, a power-law trend emerges, with exponents generally decreasing for high- to lower-income regions. In contrast, the relationship exhibits an inverted-U pattern at the grid scale. This divergence likely stems from intra-regional income inequality, previously shown to amplify disaster impacts48,49, which tends to be obscured in aggregated subnational analyses. These differences in the Vpc-GDP relationship across spatial scales underscore the importance of deriving vulnerability functions at the appropriate resolution for engineering design and policy evaluation, ensuring that investment returns are assessed with greater precision and contextual relevance.

a The global subcountry-level relationship. b–e The subcountry-level relationship stratified by income groups: high income (b), upper middle income (c), lower middle income (d), and low income countries (e). f The global 0.1 degree grid-level relationship. g–j The grid-level relationship stratified by income groups: high income (g), upper middle income (h), lower middle income (i), and low income countries (j). Colors of the points represent elevation; the red lines in penal (a–e) is the powerlaw fitting lines; the red line in panel (f) is upper envelope curve represented by 99.9% quantile regression.

The relationship between Vpc and GDP at the grid scale echoes the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), which posits a similar inverted-U shaped relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation52,53. While previous studies often attribute flood hazard initially increases with GDP as exposure intensifies, then declines as flood defenses and planning catch up with development46, it should be noted that the hazard maps used here do not account for existing protection infrastructure. Therefore, other factors, such as land-use patterns and socio-economic distribution, may also contribute to the observed trend3. For example, in practice, urban planning often prioritizes locating high-income production and densely populated communities in relatively low-flood-risk zones. Supplementary Fig. 3 illustrates that both the turning points and peak Vpc values of the inverted-U pattern differ across countries, with low-income regions tending toward lower peaks. These results potentially reflect differences in climate, topography, economic capacity, and infrastructure investment across countries53,54,55.

While GDP and its inverse are commonly employed as proxies for economic or social vulnerability5,33,41,45, such approaches typically assume a uniform relationship between wealth and flood resilience, potentially masking spatial heterogeneity of vulnerability. Here, we introduce a data-driven vulnerability grounded in the empirical Vpc-GDP dynamics at the grid level. Specifically, we fit an upper-envelope function to capture the maximum observed hazard at each GDP level worldwide (Fig. 3f). This upper envelope serves as a benchmark for potential hazard, against which actual hazard can be compared. We define the systemic vulnerability as the ratio between observed Vpc and its fitted upper bound, capturing how close a region comes to its maximum expected hazard given its economic conditions. This metric reflects how economic development modulates potential flood hazard and provides a scalable, data-driven measure of flood vulnerability.

Global mapping of potential coastal compound flood risk

To evaluate how different vulnerability functions influence PCCFR estimates, we compare three scenarios: (i) raw GDP (risk-taking), (ii) inverted GDP (risk-averse), and (iii) empirical vulnerability (data-driven risk-neutral). The GDP-based vulnerability function reflects a risk-taking scenario, assuming that rapid economic growth proceeds with negative flood defenses investment. In contrast, the inverted GDP formulation embodies a risk-averse perspective, assuming that economic development aligns with positive flood defenses investment. Our empirical approach grounds vulnerability in the observed relationship between Vpc and GDP, capturing actual trade-offs between economic development and flood defense investment.

Under the empirical vulnerability scenario, Asia exhibites the highest 35.22% internal high-risk grid cells (the fifth quintile, Q5), followed by Africa (20.21%), Europe (17.02%), South America (9.89%), and North America (2.31%) (Table 1, Fig. 4a). Subnational analyses reveal that Vietnam contributes six of the top fifteen highest-risk administrative units—namely Nam Dinh, Thai Binh, Hai Phong, Hung Yen, Binh Dinh, and Quang Nam—while Bangladesh contributes four: Barisal, Chittagong, Sylhet, and Dhaka. Other high-risk units include Rayong (Thailand), Macao (China), West Bengal (India), Gifu (Japan), and Pyongyang (North Korea) (Fig. 5a). These areas are typically characterized by low-lying coastal geography, high population density, and relatively limited flood resilience, as indicated by the proximity of observed flood hazards to their maximum potential intensity. Such conditions render these regions acutely vulnerable to coastal compound flood.

a Risk-neutral empirical vulnerability. b Risk-taking scenario. c Risk-averse scenario. Grid-scale PCCFR values were categorized into five quintiles (Q1–Q5) to indicate relative risk, with Q5 representing the highest risk. Pie charts show the proportion of grid cells in each risk quintile within each continent.

Under the risk-taking scenario, the internal proportion of high-risk grid cells is 36.96% in Asia, 28.76% in Europe, 7.55% in Africa, 5.26% in South America, and 2.78% in North America (Table 1, Fig. 4b). At the subnational level, high-income coastal regions dominate the top ranks in flood risk, driven by their low-lying topograph and high asset exposure (Fig. 5b). This scenario offers insights into flood risk under growth-oriented pathways with minimal adaptation. Under the risk-averse scenario, the internal proportion of high-risk grid cells is 35.22% in Asia, 20.21% in Africa, 17.02% in Europe, 9.89% in South America, and 2.31% in North America (Table 1, Fig. 4a). Subnationally, high-risk units are concentrated in low-income, high-hazard regions, particularly across South and Southeast Asia (Fig. 5c). These areas combine high hazard exposure with limited economic capacity, underscoring the urgent need to prioritize flood mitigation in lower-income regions.

Comparative results show that using GDP as a proxy for economic vulnerability tends to concentrate high PCCFR estimates in high-income regions. Conversely, using the inverse of GDP shifts perceived risk toward low-income regions by presuming that poverty uniformly increases social vulnerability. These two vulnerability functions rely on a priori assumptions and fail to capture the non-linear, context-specific dynamics that shape flood impacts. The contrasting results from different vulnerability functions show that assumptions about vulnerability can strongly alter where flood risk is perceived to be highest, with implications for transnational, national, and regional policy decisions. By comparison, the empirical vulnerability metric provides a data-driven, risk-neutral assessment that accounts for integrating the ratio between observed and potential hazard, providing a more balanced basis for identifying priority areas in coastal flood risk management.

Conclusion

Our scenario-based PCCFR model combines compound flood hazard, population exposure, and empirical vulnerability. Global maps show that high-risk areas are largely concentrated in major low-lying, densely populated river deltas, including the Ganges, Pearl, Niger, Mississippi, and Rhine. Asia accounts for the largest internal share of high-risk grid cells (35.22%), followed by Africa (20.21%), Europe (17.02%), South America (9.89%), and North America (2.31%) under the empirical vulnerability scenario. At the subnational level, high-risk administrative units are clustered in Southeast Asia, including Bangladesh, Vietnam, Thailand, China, India, Japan, and North Korea. This global PCCFR mapping provides a screening tool for identifying hotspots and prioritizing regions for detailed assessment and targeted adaptation.

The potential coastal compound flood hazard metric, Vpc, linearly sums riverine and oceanic flood volumes under a physically plausible co-occurrence scenario rather than explicitly calculating joint probability. Given that flood protection infrastructure is typically designed under conservative assumptions56,57, this approach provides an estimate of the conservative potential compound flood volume at each grid cell, supporting design-oriented risk assessment under deep uncertainty in hazard co-occurrence. Moreover, Vpc is derived from multiple return periods based on long-term flood simulations, providing a robust representation of flood variability and large-scale hazard patterns beyond individual short-term events. Therefore, incorporating this metric into planning efforts allows decision-makers to enhance resilience. Although compound flooding may amplify inundation depth and spatial extent beyond a simple linear sum of riverine and oceanic floods21,22, such interactions are expected to have a limited effect on total flood volume due to the conservation of flood volume43,58,59. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that compound floods can intensify impacts beyond the sum of their individual sources, and future work should evaluate these nonlinear compounding mechanisms to improve the precision of compound flood hazard estimates.

While GDP-based approaches have been widely used as simplified proxies for vulnerability41,44,45, they often obscure the complex relationship between economic development and adaptive capacity. Our approach derives vulnerability from the empirically observed relationship between Vpc and GDP, thereby reflecting real-world adaptive responses and offering a more robust basis for prioritizing flood resilience investments. This data-driven framework is both flexible and context-sensitive, allowing for its application across diverse socio-economic and geographic settings.

In all, the developed PCCFR model is flexible and context-sensitive, enabling its application across diverse socio-economic settings. However, the current results do not explicitly account for detailed local-scale analyses that account for site-specific hydrology, ecology, and socio-economic conditions; the PCCFR model should be regarded as a strategic tool for value-based prioritization rather than precise prescriptions for adaptive restoration. Building on our earlier work that established the ecohydrological fitness of Blue Carbon Ecotones (BCEs) worldwide60, the present study further focuses on site-specific flood risk due to future compounding events. Although methodologically independent, their integration bridges ecosystem health with disaster risk information, enabling a cross-scale framework that supports a value-based prioritization of adaptation actions. Future development of flood risk assessments should incorporate additional eco-environmental drivers (e.g., hydrological, ecological, and socio-economic information) together with high-resolution representations of gray infrastructure, to better capture the localized dynamics and to inform adaptation planning.

Methods

Global flood hazard dataset

Flood inundation data at 30 arc-seconds (~1 km at the equator) were obtained from the World Resources Institute’s Aqueduct Floods Hazard Dataset (2020 version). The dataset provides riverine and oceanic flood inundation (depth and extent) for multiple return periods (5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 years), separately. In this dataset, riverine and oceanic flooding are treated independently, and interactions between the two flood types are not accounted for. To illustrate the data structure used in this study, Supplementary Figs. 4, 5 present a regional example of flood inundation depths across multiple return periods for each source. These return periods represent the average interarrival time of flood events of varying magnitudes. A higher return period corresponds to a flood event of greater magnitude. Specifically, Aqueduct Floods generated present-day (2010) flood datasets for multiple return periods through the following steps61:

-

Riverine flooding refers to inundation caused by river overflow, driven by accumulated rainfall and surface runoff. The dataset covers river basins with an upstream area greater than 10,000 km2. The present-day riverine flood hazard for multiple return periods was derived by fitting extreme value distributions to inundation outputs simulated by the PCR-GLOBWB hydrological model for the period 1960–199955.

-

The oceanic flood represents flooding from storm surges and occurs along coastlines around the world. The present-day oceanic flood inundation for multiple return periods was derived by fitting Gumbel distributions to annual maximum sea levels extracted from the Global Tide and Surge Reanalysis (GTSR) dataset for the period 1979–201462.

To evaluate the potential misalignment between riverine and oceanic flood datasets, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using time series daily precipitation data, as consistent flood time series are not available and precipitation is the primary driver of flood simulation models61. Moreover, precipitation also captures the decadal variability of large-scale climate modes (e.g., North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO))63,64, thereby serving as a suitable proxy for evaluating temporal sensitivity between the two hazard sources. Specifically, we compared extreme daily precipitation (95th and 99th percentiles, P95/P99) across three time windows: 1960-1999 (riverine flood period), 1979–1999 (the overlapping period), and 1979–2014 (oceanic flood period) for five representative river deltas considering their flooding criticality (the Ganges, Pearl, Niger, Mississippi, and Rhine river deltas). The results show that, although different time windows are subject to decadal climate variability (e.g., NAO and ENSO), the long-term (~40-year) datasets capture relatively stable regional precipitation characteristics (Supplementary Table 2), indicating that different time windows of riverine and oceanic floods have a limited effect on our conclusions.

Potential coastal compound flood hazard

We calculate the Probability-adjusted Compound Flood Volume (Vpc) at 30 arc-seconds to represent potential coastal compound flood hazard. Vpc integrates riverine and oceanic flood volumes across multiple return periods under a physically plausible co-occurrence assumption (assuming a co-occurrence probability of 1), without relying on explicit joint-probability calculations (Eq. (4.1)). Specifically, Vpc comprises two components: Probability-adjusted Oceanic (Vpo) and Riverine (Vpr) flood volumes, which were calculated as in Eqs. (4.3) and (4.4), respectively. Moreover, the hazard layers used in this study do not account for existing flood protection measures (such as ecohydrological factors and anthropogenic infrastructures), and thus, Vpc represents potential flood hazards under unmitigated conditions.

where, Vpc: Probability-adjusted Compounding Flood Volume. Vpo: Probability-adjusted Oceanic Flood Volume; Vpr: Probability-adjusted Riverine Flood Volume.

To compare our approach with the joint-probability based compound flood, we computed the joint exceedance probability of riverine and coastal floods (Pjoint) using the Gumbel Copula in a pixel-by-pixel manner. Due to the lack of continuous historical observations of flood volume, synthetic time series for both riverine and coastal flood volumes were generated from their cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) to capture their statistical dependence. In calculating Pjoint, flood occurrence for both sources was defined using the moderate-event threshold corresponding to a 5-year return period. We then derived a joint-probability-weighted compound flood volume (Vpc_joint) as Eq. (4.2). Supplementary Fig. 6 compares the spatial patterns of Vpc and Vpc_joint in the Ganges River Delta, a well-recognized hotspot of compound flooding. While both metrics exhibit broadly similar spatial distributions, Vpc_joint is consistently lower than Vpc, reflecting the adjustment for the likelihood of simultaneous riverine and coastal flooding. This result indicates that our Vpc provides a more conservative representation of grid-scale compound flood hazard.

Given the distinct spatial patterns of oceanic and riverine floods, we introduce the Vpo/Vpr to distinguish their dominant contributions. A ratio greater than 1 suggests that oceanic flooding dominates, whereas a ratio less than 1 indicates that riverine flooding is the primary flood hazard.

where, j: return period of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 years; Vpo: Probability-adjusted Oceanic Flood Volume; Aoj: Oceanic Flood Area for the j-th return period; Doj: Oceanic Flood Depth for the j-th return period; and Pj: annual exceedance probability for j-th return period.

where, Vpr: Probability-adjusted Riverine Flood Volume; Arj: Riverine Flood Area for the j-th return period; Drj: Riverine Flood Depth for the j-th return period.

Socio-economic exposure

We considered population and assets as indicators of socio-economic exposure. Gridded population data at 30 arc-seconds were obtained from WorldPop65, while GDP data at 1 km resolution were derived from calibrated nighttime light observations66. Both datasets, for the year 2010, were resampled to the resolution of the compound flood hazard maps (30 arc-seconds) for analysis.

To compare population and asset exposure to coastal compound floods versus single-source floods, we divided affected areas into five quintiles (Q1–Q5, from lowest to highest) based on the Vpc values of each grid cell. Using these thresholds, we then quantified the exposure of population and assets considering only oceanic flooding or only riverine flooding. To further investigate the spatial patterns of socio-economic exposure in high-hazard zones, we focused on high-Vpc grids (Q5) and calculated their distribution at both continental and national scales.

Empirical vulnerability

We introduce a data-driven vulnerability (Ne) grounded in the empirical Vpc-GDP dynamics at the grid level. Specifically, we fit an upper-envelope function to capture the maximum observed hazard at each GDP level worldwide (Fig. 3f). This upper envelope serves as a benchmark for potential hazard, against which actual hazard can be compared. We define the systemic vulnerability as the ratio between observed Vpc and its fitted upper bound, capturing how close a region comes to its maximum expected hazard given its economic conditions. For each grid i, Ne is calculated as Eq. (4.5). Ne closer to 1 indicates regions approaching their maximum potential hazard. When computing vulnerability at the 30 arc-seconds resolution, we found that GDP exhibits limited spatial heterogeneity, resulting in histograms with GDP values concentrated within a narrow range (Supplementary Fig. 7b, d). This lack of variability makes it difficult to robustly capture the empirical relationship between GDP and Vpc. To address this issue, we compute vulnerability on a coarser 0.1 degree grid, which more effectively captures the spatial variability of both GDP and flood hazard (Supplementary Fig. 8b, d). All subsequent risk calculations involving vulnerability are therefore conducted on the 0.1 degree resolution.

where, fenvolope(GDP) represents the quadratic quantile regression at the 99.9th percentile between Vpc and GDP.

Potential coastal compound flood risk for different risk-perception’s vulnerability

We calculate global coastal compound flood risk based on the HEV framework (Eq. (4.6)). The GDP-based vulnerability (Nt) reflects a risk-taking scenario, assuming that rapid economic growth proceeds with negative flood defenses investment. As evidence shows that regions with higher GDP are more likely to invest in flood protection45, and thus possess more advanced flood defenses46, resulting in fewer flood-related fatalities and economic losses47, In contrast, the inverted GDP formulation (Na) embodies a risk-averse perspective, assuming that economic development aligns with positive flood defenses investment. Our empirical approach grounds vulnerability (Ne) in the observed relationship between flood hazard and GDP, capturing actual trade-offs between economic development and flood defense investment.

Where, Vpc: Potential coastal compound flood hazard; Ep: population exposure. Each components used in the PCCFR calculation were divided into 10 quantiles, with each assigned values from 0.1 to 1.0. This quantile-based normalization allows for consistent comparison across variables with different units and magnitudes, reduces the influence of outliers, and enables integration into a unified systemic risk, where higher values correspond to higher risk. Then we apply the cubic root because, given normalized inputs, the product of the HEV components always lies between 0 and 1. Their raw product can become disproportionately small. The cubic root restores scale through the geometric mean, yielding a more balanced integration of the three factors, consistent with the approach of Fox et al.41.

Data availability

World Resources Institute’s Aqueduct Floods Hazard Data (2020 version) are available at http://wri-projects.s3.amazonaws.com/AqueductFloodTool/download/v2/index.html. Population data from Worldpop with a high-precision spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds are available at https://hub.worldpop.org/geodata/listing?id=64. Grided Gross Domestic Product data with a high-precision spatial resolution of 1 km are available at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Global_1_km_1_km_gridded_revised_real_gross_domestic_product_and_electricity_consumption_during_1992-2019_based_on_calibrated_nighttime_light_data/17004523/1. The country’s current classification by income from the World Bank is available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. HydroSHED DEM dataset at 30 arc-seconds is available at https://www.hydrosheds.org/hydrosheds-core-downloads. The 0.1 degree grid-scale source data used for generating the figures, maps, and statistical analyses is available at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30782060).

Code availability

Codes to replicate the calculation of PCCFR are deposited in https://github.com/zhangjiaqi1996/Coastal-Compound-Flood-Risk.git.

References

Pörtner, H.-O. et al. The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate 1155, 10–1017 (IPCC, 2019).

EM-DATreport. The emergency events database report: disaster in numbers,the international disaster database https://www.emdat.be (2023).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Nearing, G. et al. Global prediction of extreme floods in ungauged watersheds. Nature 627, 559–563 (2024).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021).

Estrada, F., Perron, P. & Yamamoto, Y. Anthropogenic influence on extremes and risk hotspots. Sci. Rep. 13, 35 (2023).

Zhang, C., Xu, T., Wang, T. & Zhao, Y. Spatial-temporal evolution of influencing mechanism of urban flooding in the guangdong hong kong macao greater bay area, China. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1113997 (2023).

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. Anthropogenic climate change has changed frequency of past flood during 2010-2013. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 8, 1–9 (2021).

Manfreda, S., Iacobellis, V., Gioia, A., Fiorentino, M. & Kochanek, K. The impact of climate on hydrological extremes. Water 10, 802 (2018).

Schmidt, C. W. Delta subsidence: an imminent threat to coastal populations. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, A204 (2015).

Giao, P. H., Saowiang, K. & Anh, N. T. H. The role of groundwater and land subsidence analysis for sustainable development of infrastructure in some se asian cities. In International Conference on Critical Thinking in Sustainable Rehabilitation and Risk Management of the Built Environment, 90–100 (Springer, 2019).

Jiang, T. -t, Pan, J. -f, Pu, X.-M., Wang, B. & Pan, J.-J. Current status of coastal wetlands in China: degradation, restoration, and future management. Estuar., Coast. Shelf Sci. 164, 265–275 (2015).

Li, X., Bellerby, R., Craft, C. & Widney, S. E. Coastal wetland loss, consequences, and challenges for restoration. Anthropocene Coasts 1, 1–15 (2018).

Xu, X. et al. Global distribution and decline of mangrove coastal protection extends far beyond area loss. Nat. Commun. 15, 10267 (2024).

Couasnon, A. et al. Measuring compound flood potential from river discharge and storm surge extremes at the global scale. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 489–504 (2020).

Ghanbari, M., Arabi, M., Kao, S.-C., Obeysekera, J. & Sweet, W. Climate change and changes in compound coastal-riverine flooding hazard along the us coasts. Earths Fut. 9, e2021EF002055 (2021).

Ganguli, P. & Merz, B. Trends in compound flooding in northwestern Europe during 1901–2014. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10810–10820 (2019).

Wahl, T., Jain, S., Bender, J., Meyers, S. D. & Luther, M. E. Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major us cities. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1093–1097 (2015).

Zheng, F., Westra, S. & Sisson, S. A. Quantifying the dependence between extreme rainfall and storm surge in the coastal zone. J. Hydrol. 505, 172–187 (2013).

Ganguli, P. & Merz, B. Extreme coastal water levels exacerbate fluvial flood hazards in northwestern Europe. Sci. Rep. 9, 13165 (2019).

Zhu, Z., Zhang, W. & Zhu, W. Compound impact of storm surge and flood characteristics in coastal area based on copula. Water 16, 270 (2024).

Tang, B., Nederhoff, K. & Gallien, T. Quantifying compound coastal flooding effects in urban regions using a tightly coupled 1d–2d model explicitly resolving flood defense infrastructure. Coast. Eng. 199, 104728 (2025).

Serafin, K. A., Ruggiero, P., Parker, K. & Hill, D. F. What’s streamflow got to do with it? a probabilistic simulation of the competing oceanographic and fluvial processes driving extreme along-river water levels. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 1415–1431 (2019).

van den Hurk, B., van Meijgaard, E., de Valk, P., van Heeringen, K.-J. & Gooijer, J. Analysis of a compounding surge and precipitation event in the Netherlands. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 035001 (2015).

Eilander, D. et al. A globally applicable framework for compound flood hazard modeling. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 823–846 (2023).

Eilander, D. et al. The effect of surge on riverine flood hazard and impact in deltas globally. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104007 (2020).

Eilander, D. et al. Modeling compound flood risk and risk reduction using a globally applicable framework: a pilot in the sofala province of mozambique. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 2251–2272 (2023).

Shepherd, T. G. et al. Storylines: an alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change. Clim. Change 151, 555–571 (2018).

Shepherd, T. G. Storyline approach to the construction of regional climate change information. Proc. R. Soc. A 475, 20190013 (2019).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Meyer, V., Haase, D. & Scheuer, S. Flood risk assessment in european river basins-concept, methods, and challenges exemplified at the mulde river. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 5, 17–26 (2009).

Merz, B., Kreibich, H., Schwarze, R. & Thieken, A. Review article” assessment of economic flood damage”. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 1697–1724 (2010).

Rentschler, J., Salhab, M. & Jafino, B. A. Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nat. Commun. 13, 3527 (2022).

Cosby, A. et al. Accelerating growth of human coastal populations at the global and continent levels: 2000–2018. Sci. Rep. 14, 22489 (2024).

Green, J. et al. A comprehensive review of compound flooding literature with a focus on coastal and estuarine regions. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 747–816 (2025).

Vestby, J., Schutte, S., Tollefsen, A. F. & Buhaug, H. Societal determinants of flood-induced displacement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2206188120 (2024).

Ali, K., Bajracharya, R. M. & Koirala, H. L. A review of flood risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 1, 238636 (2016).

UNISDR. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction: Revealing Risk, Redefining Development (UNISDR, 2011).

Bin, L., Xu, K., Pan, H., Zhuang, Y. & Shen, R. Urban flood risk assessment characterizing the relationship among hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 86463–86477 (2023).

Ikram, Q. D., Jamalzi, A. R., Hamidi, A. R., Ullah, I. & Shahab, M. Flood risk assessment of the population in afghanistan: A spatial analysis of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. Nat. Hazards Res. 4, 46–55 (2024).

Fox, S., Agyemang, F., Hawker, L. & Neal, J. Integrating social vulnerability into high-resolution global flood risk mapping. Nat. Commun. 15, 3155 (2024).

Ward, P. J., De Moel, H. & Aerts, J. How are flood risk estimates affected by the choice of return-periods?. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 3181–3195 (2011).

Mudashiru, R. B., Sabtu, N., Abustan, I. & Balogun, W. Flood hazard mapping methods: A review. J. Hydrol. 603, 126846 (2021).

Tiggeloven, T. et al. Global-scale benefit–cost analysis of coastal flood adaptation to different flood risk drivers using structural measures. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 1025–1044 (2020).

Imamura, Y. Development of a method for assessing country-based flood risk at the global scale. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 13, 87–99 (2022).

Rudari, R. et al. Improvement of the Global Flood Model for the GAR 2015, 69. (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), Centro Internazionale in Monitoraggio Ambientale (CIMA), UNEP GRID-Arendal (GRID-Arendal): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015).

Jongman, B. et al. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, E2271–E2280 (2015).

Lindersson, S. et al. The wider the gap between rich and poor the higher the flood mortality. Nat. Sustain. 6, 995–1005 (2023).

Tselios, V. & Tompkins, E. L. What causes nations to recover from disasters? an inquiry into the role of wealth, income inequality, and social welfare provisioning. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 33, 162–180 (2019).

Pethick, J. S. An Introduction to Coastal Geomorphology. Technical Report (Department of Geography, Univ. of Hull, 1984).

Knighton, D. Fluvial Forms and Processes: A New Perspective (Routledge, 2014).

Stern, D. I. The rise and fall of the environmental kuznets curve. World Dev. 32, 1419–1439 (2004).

Huang, G. Does a kuznets curve apply to flood fatality? a holistic study for china and japan. Nat. Hazards 71, 2029–2042 (2014).

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 816–821 (2013).

Winsemius, H. C. et al. Global drivers of future river flood risk. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 381–385 (2016).

Le, P. D., Leonard, M. & Westra, S. Spatially dependent flood probabilities to support the design of civil infrastructure systems. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 4851–4867 (2019).

Xiong, B. et al. Robustness of design flood estimates under nonstationary conditions: parameter sensitivity perspective. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 38, 2297–2314 (2024).

Fernández-Pato, J. & García-Navarro, P. Development of a new simulation tool coupling a 2d finite volume overland flow model and a drainage network model. Geosciences 8, 288 (2018).

Aslam, M. H. et al. Flood volume allocation method for flood hazard mapping using river model with levee scheme. EGUsphere 2025, 1–22 (2025).

Zhang, J. & Convertino, M. Blueprinting the ecosystem health index for blue carbon ecotones. iScience 27, 111426 (2024).

Ward, P. J. et al. Aqueduct floods methodology (World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C., 2020).

Muis, S., Verlaan, M., Winsemius, H. C., Aerts, J. C. & Ward, P. J. A global reanalysis of storm surges and extreme sea levels. Nat. Commun. 7, 11969 (2016).

Hurrell, J. W. Decadal trends in the north atlantic oscillation: regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269, 676–679 (1995).

Yeh, S.-W. et al. Enso atmospheric teleconnections and their response to greenhouse gas forcing. Rev. Geophys. 56, 185–206 (2018).

Liu, L., Cao, X., Li, S. & Jie, N. A 31-year (1990–2020) global gridded population dataset generated by cluster analysis and statistical learning. Sci. Data 11, 124 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Global 1 km × 1 km gridded revised real gross domestic product and electricity consumption during 1992–2019 based on calibrated nighttime light data. Sci. Data 9, 202 (2022).

Acknowledgements

M.C. acknowledges the Shenzhen Pengcheng Peacock Pengcheng Talents funding (B class, 0020210320), “ECOgeomorphic and Hydroclimatic ImpactS on Biodiversity and Ecosystem FuNction: Mapping Critical Shifts and ConnEctions” (ECOSENSE); and the Shenzhen Stability Support Grant (WDZC20231128160214001), ”Optimizing Deltas’ Natural Engineers: Systemic Restoration to Counter EcoHydroClimate Extremes”; and funding from the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (ZDSYS20220606100806014) for the Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Ecological Remediation and Carbon Sequestration at Tsinghua SIGS; and funding from the Tsinghua SIGS Cross-disciplinary Research and Innovation Fund Research Plan “The Fibers of Nature: Ecohydrological Flows Assessment via Distributed Fiber-optic Sensing Networks” (JC2024011). M.C. acknowledges the conversations with the Future Earth CYBER-COAST group (https://www.futureearthcoasts.org/cyber-coast/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Convertino designed and guided the study and finalized the manuscript. J. Zhang designed and performed the calculations and created the figures and draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Mariano Balbi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Giada Varra and Nandita Basu. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Convertino, M. Global mapping of potential coastal compound flood risk at 0.1∘ resolution. Commun Earth Environ 7, 83 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03155-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03155-7