Abstract

Severe wildfire seasons in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) raise questions regarding long-term fire dynamics and their drivers. However, data on long-term fire history remains scarce across eastern Siberia. Here we present a composite of reconstructed wildfire dynamics in Yakutia throughout the Holocene, based on eight newly contributed records of macroscopic charcoal in lake sediments in combination with published data. Increased biomass burning occurred in the Early Holocene, c. 10,000 years BP, before shifting to lower levels at c. 6000 years BP. Independent simulations of climate-driven burned area in an individual-based forest model reproduce this reconstructed Holocene trend, but the correlation on multi-centennial timescales turns negative in the Late Holocene. This mismatch suggests that climate alone cannot explain Late Holocene wildfire dynamics. We propose that a human dimension needs to be considered. By example of the settlement of the pastoralist Sakha people c. 800 years BP, we show that implementing reduced fuel availability from Indigenous land management in the forest model leads to increased multi-centennial-scale correlations. This study highlights the need for a better understanding of the poorly reported human dimension of past fire dynamics in eastern Siberia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wildfires in boreal forests are becoming more extreme1, with eastern Siberia as one of the most affected regions2. The fire regime intensification here occurs in a unique and climate-sensitive ecosystem of deciduous larch forests and continuous permafrost3. Annual burned area and fire intensity in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), referred to as the coldest permanently inhabited region on Earth4, have seen pronounced increases over recent decades for which satellite observations are available5. Fire brigades and voluntary firefighters across Yakutia, challenged by a lack of funding and restrictive policies6,7, were confronted with unusually intense crown fires. As a consequence, several settlements were endangered, infrastructure was blocked or destroyed, and exposure to hazardous smoke was widespread8,9. It is predicted that fire regimes will continue to intensify under a steadily warming climate2,10, with unknown implications for ecosystem stability11,12. In other boreal regions, understanding past Indigenous land use and fire management practices contributed valuable insights for improving modern approaches to wildfire mitigation13,14,15. However, the extent to which humans and climate influenced past fire regimes remains difficult to assess, especially in data-scarce regions such as Siberia16. Systematic satellite-based fire observations over the last few decades are a valuable source of data; however, they do not permit a direct evaluation of centennial to millennial-scale trends. An evaluation of past natural and human drivers behind changing wildfire dynamics requires information for more than the last few decades.

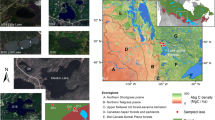

The long-term fire history is unknown across most regions of the vast larch forests of eastern Siberia, covering c. 2.6 million km² and representing almost 40% of the forested area of Russia17. This is because of a lack of paleoecological data on past wildfire dynamics16. Only a few studies have investigated centennial- to millennial-scale fire dynamics in boreal Yakutia18. Macroscopic charcoal particles (>100 µm) in lake sediments can be leveraged as a paleoecological proxy to reconstruct trends of biomass burning in the vicinity of a lake19. Katamura et al. contributed charcoal records near Yakutsk, spanning the Holocene (Lake Sugun, Lake Chai-ku, Maralay Alaas; Fig. 1)20,21. Based on their data, they suggest a stable surface fire regime throughout the Holocene. In contrast, Glückler et al. found variable Holocene fire activity and the establishment of the modern surface fire regime c. 4500 years BP (Before Present; i.e., before calendar year 1950) from a charcoal record in western Central Yakutia (Lake Satagay; Fig. 1)22. Besides the scarce data availability limiting the understanding of Holocene fire history, underlying drivers have not, so far, been systematically investigated.

Blue lines mark major river centerlines from Natural Earth. Boreal forest extent from ESA Land Cover CCI. Coordinate systems used: WGS 1984 EPSG Russia Polar Stereographic (left), UTM 54 N (upper right), UTM 52 N (lower right). “World imagery” basemap sources: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, i-cubed, USDA FSA, USGS, AEX, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community.

Climate constitutes an important natural driver of long-term fire regime changes. Temperature and relative humidity are key factors influencing fire weather23. Climatic variables can therefore affect the number of ignitions, fire extent, and fire severity24. However, the impact of fire weather on fire regimes varies depending on other factors, such as fuel availability and characteristics (e.g., species composition, structure, flammability), and can therefore be heterogeneous in space and time. At Lake Satagay, reconstructed periods with high amounts of biomass burning were suggested to correspond to known climatic phases, such as the Holocene Climatic Optimum22. In this study, a closer analysis of climate as a driver of Holocene wildfire dynamics was hampered by the low availability of paleoclimatological data from the region. Stieg et al. contributed an oxygen isotope record from lacustrine diatoms in south-western Yakutia, showing periods with a warmer and/or drier climate coinciding with increased wildfire activity during the most recent centuries25. However, as a result of the scarcity of vegetation-independent long-term climate reconstructions, the influence of past climatic changes on Holocene fire dynamics in Yakutia is poorly understood.

Humans were found to act as drivers of fire regimes for many millennia in various regions of the world26,27. However, the extent to which people in boreal Yakutia influenced past wildfire dynamics is unknown. Hominins lived across southern Siberia at least c. 800,000 years ago28, and humans from nomadic hunter-gatherer cultures roamed eastern Siberia since more than 40,000 years ago29,30. An increased frequency of occupation periods across eastern Siberia has been recorded since the Mid-Holocene, and Central Yakutia may have been a prominent station along south-to-north migration routes31. It is not known whether these activities influenced fire regimes. The arrival of the pastoralist Sakha people in Central Yakutia around 1200 CE (Common Era) resulted in a cultural shift towards dispersed semi-nomadic and sedentary livelihoods based on horse and cattle breeding32. Many traditional land management practices, such as haymaking, shrub removal, and cultural burning33,34, likely had complex impacts on the environment. For example, whether the probable consequence of reduced fuel loads may have affected fire regimes has not yet been tested. In a high-resolution charcoal record, covering the last two millennia in southwest Yakutia (Lake Khamra; Fig. 1), Glückler et al. found high wildfire activity around 900 CE and low activity until c. 1850 CE35. With pollen data suggesting stable vegetation composition, it was speculated that changes in fire regime were initially driven by climatic changes and increasingly influenced by human land management only during the most recent centuries. However, these speculations were limited by the evidence being based on a single site and the lack of a specific method to test for changing natural or human drivers.

Regional trends of biomass burning during wildfires can be derived from the more locally-influenced macroscopic charcoal records by synthesizing a composite curve out of multiple sites36,37. This approach, necessitating a higher availability of charcoal records, enables an analysis of past wildfire dynamics beyond the local scale of each individual record. While composited charcoal records provide data on past wildfire dynamics, global climate simulations in Earth system models can be used to infer causal relationships with climate data and assess potential climatic drivers38,39. Such climate data can also be used to directly simulate wildfires in forest models for eastern Siberia. Modeling frameworks can therefore provide a novel opportunity to test for potential impacts of past climate and human land management practices on wildfire dynamics. Of the few forest models localized specifically to capture fine-scale larch forest dynamics (e.g., SEIB-DGVM40, UVAFME41), only the individual-based, spatially explicit LAVESI-FIRE was previously used to validate multi-millennial trends of larch forest development and wildfire disturbance in an initial comparison with paleoecological data from a charcoal record42.

In this study, we aim to elucidate multi-centennial to millennial-scale Holocene wildfire history in Yakutia and evaluate the hypothesis that humans contributed to shaping past wildfire regimes, as opposed to an alternative hypothesis of predominantly climate-driven wildfire dynamics. We contribute eight new Holocene records of macroscopic charcoal in lake sediments and simulate climate-driven changes of wildfire activity in a forest model. By creating a composite curve of Holocene charcoal accumulation, we analyze long-term wildfire dynamics. We then simulate climate-driven burned area to estimate the role of climate as a driver behind reconstructed fire dynamics, and to test our hypothesis of human-driven reductions in fuel availability impacting fire regimes in the Late Holocene. Results reveal that high amounts of biomass burning reconstructed during the Early to Mid-Holocene correspond well to the expected impact of past climatic trends. While climate-driven simulations may be able to explain longer multi-millennial trends of reconstructed biomass burning, shorter multi-centennial trends since the Mid-Holocene may rather result from human activity. By example of the Sakha people, we discuss how traditional land management practices may have influenced fire regimes long before industrialization.

Results

Reconstructed Holocene wildfire dynamics

Eight newly contributed records of the accumulation of macroscopic charcoal particles in lake sediments from the Lena-Amga interfluve in the Central Yakutian Lowland, the southern Verkhoyansk Mountains, and the Oymyakon Highlands increase Holocene paleofire data availability in Yakutia (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The new records cover the last 7200 years or parts of this period. The average charcoal accumulation rate for all newly contributed charcoal records is 0.33 ± 0.41 particles cm−2 yr−1 (mean ± standard deviation), ranging for individual records from a minimum of 0.04 ± 0.04 particles cm−2 yr−1 (Lake 402, Lake 408) to a maximum of 1.27 ± 1.08 particles cm−2 yr−1 (Lake 421).

We obtained the regional trend of charcoal accumulation throughout most of the Holocene (10,930 to −70 years BP) by compositing the eight new records in combination with four existing records from the region in the Global Paleofire Database (formerly known as Global Charcoal Database16,43; Fig. 2). With an average temporal resolution of 82 ± 56 years per sample across all sediment cores, the composite curve highlights both millennial and multi-centennial trends.

A Composite curve of Yakutian charcoal records, standardized, using a base period from −70 to 11,000 years BP. Shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. Star symbols indicate peaks of individual records that extend beyond the plotting area. B Temporal coverage of individual records included in the composite curve. Black dots indicate age control points for each record, including radiocarbon ages, surface ages as year of core extraction, and lead-210, cesium-137 ages (Lake Khamra only). Star symbol marks charcoal record extending beyond the analyzed time frame (Lake Sugun only).

Charcoal accumulation during the Early Holocene and early Mid-Holocene was high, with two maxima at c. 10,000 and c. 8000 to 7000 years BP. In the Mid-Holocene, our results indicate a shift to a lower level after 6000 years BP. Charcoal accumulation continues to vary at this lower level throughout the Late Holocene, with record-wide minima at 4000 and 2500 years BP. The last two millennia are characterized by increasing values after 2500 years BP, followed by a pronounced decrease around 1200 CE. The most recent centuries see an increase in charcoal accumulation again, although remaining below levels recorded both in the Early Holocene and before 1200 CE. Confidence intervals of the composite curve suggest highest agreements between the different contributing charcoal records for the Early Holocene maximum (10,000 years BP) and the subsequent Mid-Holocene decrease (6000 years BP). Notably, high agreement is also suggested for the most recent decrease of charcoal accumulation (800 years BP or 1200 CE), where 11 out of 12 charcoal records are represented.

Simulated climate-driven changes of wildfire activity

We used the individual-based, spatially explicit forest model LAVESI-FIRE42 to simulate climate-driven changes of burned area in Central Yakutia throughout the Holocene (simulation location is indicated in Fig. 1). Trends of simulated burned area compare well to the charcoal-based, reconstructed composite curve on a multi-millennial scale throughout the Holocene when filtered to equidistant temporal resolution (Fig. 3B; Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.90; p < 0.05).

On a longer multi-millennial scale both time series are highly correlated, but on a shorter multi-centennial scale their correlation turns negative in the Mid-Holocene. A Climate forcing data for LAVESI-FIRE simulations from MPI-ESM-CR116,117 (smoothed annual June, July, and August mean temperature and precipitation sum) and the derived annual fire probability rating (FPRann)42. B Comparison between filtered annually simulated burned area and the charcoal composite curve. The green line represents the median of ten smoothed simulation repeats, while the transparent band marks the interquartile range. Note that both time series are slightly truncated due to edge-effects of the filtering procedure. C Rolling window correlation coefficient (r) between simulated burned area (median) and the charcoal composite curve (mean) for window widths ranging from 110 to 10,010 years. Isolines and colors mark correlation coefficient ranges (red = positive correlation; blue = negative correlation). White shading marks non-significant correlation coefficients (p > 0.05, two-sided Monte Carlo-based significance test accounting for autocorrelation).

A comparative analysis of rolling correlations ranging from centennial to multi-millennial scales (Fig. 3C) indicates that also on shorter multi-centennial scales simulated burned area reproduces the high-agreement maximum of reconstructed charcoal accumulation at c. 10,000 years BP and the subsequent decrease before 6000 years BP. However, during the Mid-Holocene there is a shift from positive correlations (c. 11,000 to 5000 years BP) towards significant negative correlations (c. 5000 years BP to present). In the Late Holocene, reconstructed trends of biomass burning are not reproduced by our climate-driven simulated burned area on these shorter timescales, including the last millennium (Fig. 4; r = −0.97; p < 0.05). An additional reduction of fuel availability in the model after 1200 CE, as a suggested major net effect of human pastoralist activity, leads to an increased fit of simulated burned area to reconstructed trends of charcoal accumulation during this last millennium (Fig. 4; r = 0.95; p < 0.05).

Reducing the model’s fuel availability to 20%, as one suggested consequence of the settlement of the pastoralist Sakha people, increases the correlation between simulated and reconstructed data. Colored lines represent the filtered median of ten simulation repeats per scenario, while the transparent bands mark the interquartile range. The vertical line at 1200 CE marks the beginning of the additional fuel reduction.

Discussion

Our composite curve in Yakutia indicates high regional wildfire activity in the Early to Mid-Holocene (c. 11,000 to 7000 years BP). This is followed by a shift to a lower level until present. This finding represents a deviation from reconstructed global and northern hemispheric biomass burning trends, where a long-term increase of biomass burning was reported since the beginning of the Holocene16. When assessed regionally, charcoal record composites reveal contrasting Holocene trends37. Our new data on long-term wildfire activity in Yakutia, to our knowledge the first regional composite in eastern Siberia, differs from a regional-scale composite of charcoal records from interior Alaska, where gradually increasing biomass burning throughout the past 10,000 years was reported44. Power et al., on the other hand, found a maximum of biomass burning in the Early Holocene in eastern North America36. Our regional composite from eastern Siberia fills an important data gap in the distribution of boreal paleofire studies16 and demonstrates that global or hemispheric composites are not necessarily representative of regional wildfire history in Yakutia, an especially fire-prone region45 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The Holocene-scale trend of biomass burning is overlain by variation on a multi-centennial scale (Fig. 3B). Few charcoal records currently cover the Early to Mid-Holocene in Yakutia (Fig. 2B) and eastern Siberia as a whole. During this time, we find maxima of biomass burning at 10,000 and 8000 years BP, which is in agreement with maxima reported from macro- and microscopic charcoal records near Lake Baikal46,47. These studies furthermore indicate rapid shifts to lower levels of biomass burning in the Mid-Holocene, although timing differs between lakes and is recorded about one millennium after the pronounced decrease around 6000 years BP we find in Yakutia. In the Mid- to Late Holocene, where more charcoal records are available, we record short-term minima of biomass burning at c. 4000 and 2500 years BP, followed by a pronounced decrease around 1200 CE. Similar trends have been found in other composites from the Northern Hemisphere, albeit at differing times16. Marlon et al. reported a decrease in burning from 1400 to 1750 CE, especially in extratropical western North America and Asia48. In south-central Canada, a marked decrease of biomass burning to low levels occurred around 2000 years BP26. However, reconstructed trends of wildfire activity in boreal forests of North America may not be directly transferable to eastern Siberia, considering the dependence of wildfire dynamics on the regionally differing relationships with forest composition (e.g., abundance of fire-embracing Picea mariana or Pinus banksiana, which do not naturally occur in eastern Siberia)49,50,51.

We use a comparison between reconstructed and simulated wildfire activity to estimate the extent to which climate acted as a driver of past wildfire dynamics. Our model specifically represents climate-driven changes of the simulated burned area, since climate (expressed by monthly temperature and precipitation) is the main driver of fire occurrence, which is then only mediated by factors such as fuel availability and topography-derived surface moisture availability42. The simulation outcome tends to react more sensitively to temperature than precipitation, fitting to the largely temperature-limited environment42. This results in the simulated burned area being highly correlated to the climate-derived fire probability (Fig. 3A, B). The ability of the simulated climatic forcing data to capture ecologically informed past climate variability is an important factor to consider for comparisons of simulations and reconstructions, and represents another reason, besides the temporal resolution of our charcoal records, to limit our evaluation to multi-centennial and broader scales52.

Climatic changes can explain our reconstructed wildfire dynamics on a longer multi-millennial scale throughout the Holocene. This is indicated by a high positive correlation between our reconstructed wildfire activity and simulated burned area, which is mainly driven by the climate (Fig. 3B; r = 0.90; p < 0.05). This finding reinforces a previous assertion that long-term wildfire activity is strongly driven by climatic changes53, and we now show this to be the case in eastern Siberia as well. Following the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, a strongly warming climate resulted in the Holocene Climate Optimum54, which has been suggested to facilitate high amounts of biomass burning in previous local studies22,55. These climatic controls likely explain the high correlation between simulated and reconstructed data of this study on a longer, multi-millennial scale, characterized by wildfire activity shifting from high to low levels over the course of the Holocene.

Trends of reconstructed Holocene wildfire activity in Yakutia correspond to known climatic changes from independent climate reconstructions. Temperature estimates derived from regional pollen records in Central Yakutia confirm the multi-millennial trend of an Early Holocene increase shifting to a decrease in the Mid-Holocene, with a Holocene maximum around 8000 to 9000 years BP39. Lakes in Central Yakutia and the Yana Highlands recorded high productivity from increased organic carbon accumulation between c. 11,500 to 9000 years BP, likely facilitated by warm climatic conditions following peak summer insolation at the beginning of the Holocene56,57. A cooling trend towards the Late Holocene is also reflected by oxygen isotopes in diatom silica of lakes across northern Eurasia58, as well as in ice wedges in Central Yakutia59.

On a shorter multi-centennial scale, however, trends of reconstructed and simulated wildfire activity are positively correlated only in the Early to Mid-Holocene (until c. 5000 years BP; Fig. 3B). During this time, our results show a period of reduced biomass burning around 8200 years BP. This coincides with a well-known global event following freshwater outbursts from the melting Laurentide ice shield, leading to a wide-spread decrease in temperature60,61. The return to higher wildfire activity from c. 8000 to 7000 years BP corresponds to a warm period during the late stages of the Holocene Climate Optimum, which has been linked to widespread thermokarst initiation62. A paleohydrological record from southern Siberia indicates unstable climatic conditions during the Early Holocene63, which may explain the highly variable charcoal accumulation rates during that time (Fig. 2A). During the Late Holocene, climatic shifts of a lower amplitude, such as the Medieval Warm Period (c. 950 to 1250 CE) or the Little Ice Age (c. 1400 to 1750 CE)64, may have impacted wildfire activity. However, our climate-driven simulations are negatively correlated to reconstructed wildfire activity on the shorter multi-centennial scale (Fig. 3C), indicating that climate may not be mainly responsible for the reconstructed pattern of biomass burning during this time.

Vegetation composition, a key control of fire regimes by affecting fuel type and availability24, did not change strongly throughout the Holocene and is thus unlikely to be a key driver of multi-centennial fire regime variability in the Late Holocene22 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Previous paleoecological reconstructions from North America suggested shifts in vegetation composition as a key driver of Holocene fire regime changes65. However, reconstructions based on palynological data and sedimentary ancient DNA analyses show how Early Holocene open woodlands of Yakutia, populated mainly by larch (Larix) and birch (Betula), became gradually denser and mixed with only a few other species during the Holocene66,67,68,69. Larch remained the main forest-forming tree ever since forest establishment began in tundra-steppe environments following the Last Glacial Maximum70. Vegetation composition may, instead, have reacted to variability in the fire regime. This is demonstrated by an increased abundance of birch, which commonly establishes on post-fire disturbed areas, during the fire-prone Early Holocene22,71. Reduced wildfire activity in the Mid- to Late Holocene, on the other hand, may have enabled evergreen trees such as the fire-avoiding spruce (Picea) to establish, albeit only in the southwest of Yakutia35,49. Pine (Pinus) invaded Central Yakutia only in the Mid-Holocene, and remained limited to patches of sandy terrain such as along the Lena River banks3,72.

Neither vegetation composition nor climate appear to be the main driver behind the multi-centennial variability of reconstructed wildfire activity during the Late Holocene. Our results indicate a potential change in drivers around 5000 years BP, when the correlation of reconstructed biomass burning and simulated burned area first decreases to zero and then turns negative for the remaining period of the Late Holocene (Fig. 3C). This timing coincides with an increase in human activities in eastern Siberia.

Impacts of nomadic hunter-gatherers, who lived in eastern Siberia since before the Holocene29, may have been limited in spatial scale and non-persistent during Mesolithic to Neolithic times (c. 12,000 to 5000 years BP; Fig. 5). Lightning-fire-prone environments (which include boreal eastern Siberia) have been found to predict the use of fire by hunter-gatherer communities73. In such environments, anthropogenic burning by small communities has the potential to decrease the severity of naturally occurring wildfires73. It remains unclear to what degree this may apply to hunter-gatherers in eastern Siberia. Our results do not provide evidence for impacts of nomadic communities focused on hunting small mammals, fishing, and gathering plants28 on wildfire dynamics during this time. Therefore, we assume that any imprint in multi-centennial to millennial-scale trends of wildfire activity beyond natural trends may have been limited74,75.

Human activity intensified at the onset of the Bronze Age (c. 5000 years BP; Fig. 5), coinciding with a shift in the fire-climate relationship (Fig. 3C). The number of people following south-to-north migration towards the Siberian Arctic increased strongly30,31. Increased mobility may have been facilitated by the proliferation of horse riding28. Central Yakutia, connecting the Baikal region to the Arctic via the Lena River, was an important region for major migrations31. In addition, animal husbandry and agriculture began spreading from Central and East Asia towards southern Siberia and the Far East around that time28, mixing with or displacing hunter-gatherer communities76. Nomadic pastoralism with sheep, goats, cattle, and horses has been recorded in the Cis-Baikal region, south of Yakutia, since at least 3000 years BP76. How early these developments spread northwards into Yakutia remains difficult to assess, but based on our results, we suggest that there may have already been impacts on wildfire dynamics during the Bronze Age. Low population density does not exclude the possibility of human impacts on fire regimes by itself77,78. Among other environmental impacts, the spread of pastoralist livelihoods in the Late Holocene may have sufficiently reduced fuel loads to alter regional fire regimes79, especially along the main migration routes. This human impact on regional fire regimes may have weakened the coupling of fire regimes to climatic variability, thus resulting in weak or lacking correlations in our study. Similar impacts of Indigenous land management, reducing fuel loads and weakening the fire-climate relationship, were found at varying spatial and temporal scales in North America80,81. However, considering increased population growth (and thus impacts also on fuel availability) during warmer, i.e., more fire-prone climatic periods82, this could also explain the negative correlation we find between reconstructed biomass burning and the climate-driven simulations during the Late Holocene.

The fit between our simulated and reconstructed wildfire activity improves when accounting for human-caused fuel reduction in the forest model (Fig. 4). In addition to wildfire dynamics that are not explained by climatic or vegetation changes alone, these factors present first evidence for the potential of land management impacts of early cultures on fire regimes in eastern Siberia during the Late Holocene. As an example, we focus on a known cultural shift around 1200 CE (1100–1300 CE), a warm climatic period64, when the pastoralist Sakha people settled in Central Yakutia32,33,83,84 (Fig. 5). Coming from southern steppe environments, the Sakha likely initially settled along the Lena River33. The region between the Lena, Aldan, and Amga rivers later recorded the highest population in the 17th century, and most of our studied lakes are located there85,86 (Fig. 1). The Sakha followed semi-nomadic to sedentary pastoralist livelihoods with horse and cattle breeding85,86. Haymaking was an important practice to feed the animals during Yakutia’s long winters. Surrounded by dense forest, they used meadows in non-forested permafrost drained lake basins (i.e., alaas landscapes)87,88,89 during the summers and kept them suitable for haymaking by removing shrubs or encroaching trees34. They also cleared space in the forests to create open areas for haymaking, and later for growing wheat90, which included the managed use of fire9,34,91. Horses were grazing freely in forests and pastures. Pine and larch wood served as preferred construction material for houses, sheds, and other structures33. Sakha families did not reside permanently in consolidated settlements, but also lived by their dispersed alaases and managed their surrounding environment during the warm season34. These combined practices may have succeeded in keeping severe wildfires at a distance by reducing fuel loads in the surroundings of the settlements9,26, presumably on the scale of a few kilometers, but likely amplified regionally by the dispersed settlement pattern. Macroscopic charcoal as a proxy of local to regional biomass burning emphasizes impacts of human activity in the vicinity of lake systems19. Although the precise timing of the onset, the duration, and the intensity of human alterations of the fuel loads are poorly constrained and other ways of fire regime alteration may have occurred as well, testing this proposed aspect of human impact by including an additional reduction of fuel availability after 1200 CE increases the correlation of simulated burned area to reconstructed biomass burning (Fig. 4).

Our results display an increase of biomass burning over the most recent centuries (Fig. 2A), which may reflect another cultural shift after the colonization of Yakutia by the Tsardom of Russia in the 17th century33,35,84 (Fig. 5). A rapidly growing population and expanded land development across Yakutia may have increased the rate of unintentional anthropogenic ignitions92,93. By the 20th century professional fire suppression was established, while slash-and-burn agriculture was restrained94. During the collectivization period, settlements were consolidated, and kolkhozes worked to increase agricultural output34. Cultural burning practices were completely prohibited in Yakutia in 2015, despite opposition from Sakha locals9,91. Previously managed fields further away from the newly formed towns were abandoned after the end of Soviet era collectivization95, which may further contribute to a build-up of fuel. However, fire reconstructions with a higher temporal resolution would be needed to assess centennial to sub-centennial impacts of past human activity on fire regimes, as opposed to our multi-centennial to millennial-scale analysis. Still, these recent developments highlight the potential value of understanding how Indigenous communities may have reduced levels of biomass burning around their settlements throughout the past millennia.

Conclusions

We explored imprints of climate, vegetation, and humans on reconstructed wildfire dynamics by applying a combination of paleoecological and modeling approaches. Our results strengthen the understanding of Holocene wildfire activity in the unique ecosystem of eastern Siberia, which was previously underrepresented in global paleofire compositions. We find that climate was likely the main driver of longer, millennial-scale trends of wildfire activity, which implies a continuing sensitivity of wildfire regimes to climate change. A negative correlation between our simulated climate-driven burned area and reconstructed biomass burning, together with a stable vegetation composition, points towards human activity as a potential driver of shorter, multi-centennial-scale variability of wildfire activity since c. 5000 years BP. Increasing human mobility and the spread of pastoralist livelihoods may have reduced fuel availability along major migration routes, whereas the pastoralist Sakha people later used cultural burning to shape the surrounding forest to their needs. A corresponding additional fuel reduction in our forest model results in an increased fit of simulated to reconstructed wildfire activity during the last millennium, which further demonstrates that wildfire dynamics may have been influenced by humans earlier than expected. This finding may indicate that historical low-severity fire regimes may, to some extent, be a result of human landscape modification. Considering the lack of systematic assessments of past human influence on fire regimes in boreal eastern Siberia, we recommend including the evaluation of a human dimension in future paleoecological studies and to take into account traditional ecological knowledge and potential effects of past land management practices.

Methods

Location

The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), located in eastern Siberia, is Russia’s largest administrative subdivision. The region is characterized by vast boreal forest dominated by Larix on deep, continuous permafrost96. Degradation of ice-rich permafrost can lead to the development of thermokarst lakes and, over longer timescales, non-forested basins with residual lakes (alaas)89. The extremely continental climate can reach an annual temperature amplitude of more than 100 °C between the warmest and coldest day22. However, despite the extremely cold winters, warm summers, and relatively low annual precipitation of c. 200–400 mm create optimal conditions for frequent, but generally low-intensity surface fires3, although recent years have seen increases in both fire extent and severity97.

The studied lakes are located on a c. 700 km long transect between the republic’s capital Yakutsk in the west and Oymyakon in the east, with the westernmost site being Lake 437 (N 62.34470; E 130.37543) near the Lena River, and the easternmost site being Lake 410 (N 63.23035; E 142.95733) in the Oymyakon Highlands, and share a strongly continental climate and a similar vegetation composition. Since it was not possible to find out the given names of all visited lakes, they will be here referred to instead by their fieldwork ID (i.e., Lake 402 to Lake 455). Known lake names, as well as a compilation of general attributes of each site, are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Fieldwork and sediment core subsampling

Fieldwork took place in August and September 202198. A total of 66 lakes of various settings were visited, from 58 of which sediment cores were obtained. With the help of point measurements using Hondex PS-7 ultrasonic depth sounders the deepest parts of the lakes were estimated. A UWITEC gravity corer (UWITEC GmbH, Austria) was used for sediment coring from rubber boats, occasionally equipped with a hammer module. Most sediment cores were obtained in PVC tubes of 9 cm in diameter, although for a few lakes an alternative setup with 6 cm diameter was used. Sediment cores were tightly sealed at the campsites. Of all the sediment cores presented in this study, only the one from Lake 408 (sediment core EN21408-2) was subsampled in the field in consecutive 1 cm intervals and stored in Whirl-Pak® bags. After the expedition, all sediment cores were collected at the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk before being shipped to Potsdam, Germany, in cooled thermoboxes, where they were stored at 4 °C.

In April 2022, one sediment core from each lake was selected based on length and visual quality, and opened lengthwise with an electric saw in a clean climate chamber. The sediment core inside the opened tube was split into two halves using long metal sheets. One half of each sediment core was designated for subsampling, with the other half being archived. From all 58 available sediment cores, 14 were selected for subsampling based on lake location, ensuring coverage along the whole expedition route, as well as length, diameter, and a visual confirmation of undisturbed sedimentation. Between July and November 2022, these 14 sediment cores were subsampled in contiguous 1 cm segments in a clean climate chamber under sterile conditions. To avoid contamination the topmost sediment surface and all sides touching the PVC tube were carefully removed using sterile scalpels. From each segment we obtained samples for charcoal and palynological analysis (1 cm³) and for total organic carbon measurement (TOC; 1–2 cm³), with excess sediment material being stored for potential other analyses. Every 10 cm, we extracted a bulk sediment sample for radiocarbon (14C) dating (2 cm³). For the sediment core from Lake 408, subsampled in the field, the same amounts of sediment were taken out of the individual Whirl-Pak® bags for charcoal and palynological analysis, and 14C dating, respectively.

14C dating

Bulk sediment 14C samples were freeze-dried and homogenized in a planetary mill. TOC was measured with a soliTOC cube analyzer. Accelerator mass spectrometry 14C dates were obtained at the MICADAS (Mini Carbon Dating System) laboratory at AWI Bremerhaven, Germany, following standard protocols99 (Supplementary Table 2). 14C ages were calibrated using the IntCal20 calibration curve100 during age-depth-modeling with the package “rbacon”101 in R (v. 4.3.2)102. Based on the resulting sediment core chronologies (Supplementary Fig. 1), another selection was made to include only those with valid age-depth relationships, resulting in the eight cores included in this study. Following Walker et al., the periods of Early, Mid-, and Late Holocene refer to subdivisions at 8200 and 4200 years BP, respectively103.

Macroscopic charcoal analysis

Preparation of macroscopic charcoal samples was done by the well-established wet sieving approach, following previously published protocols22,35. Sediment samples of 1 cm³ were soaked in a solution of sodium pyrophosphate (Na4P2O7) for 1–3 days to ease disaggregation of the sediment matrix. To enable the determination of pollen concentrations, one tablet of Lycopodium clavatum marker spores (Lund University, Department of Geology) per sample was dissolved in 10% hydrochloric acid (HCl) and added. Then, the samples were poured into a sieve at 150 µm mesh width, a standard size to separate macroscopic charcoal from the smaller sediment and pollen fractions. After thorough sieving, the macroscopic fraction in the sieve was transferred into 50 mL Falcon tubes. After letting the samples rest, they were carefully decanted. Next, c. 20 mL of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) bleach was added, and samples left to soak overnight. This bleaching step improves charcoal identification by increasing the contrast between the black, non-reactive charcoal particles against other bleached organic matter104. In a final step, samples were briefly rinsed in a 63 µm mesh sieve to improve clarity after bleaching.

Charcoal quantification was done in a gridded petri dish under a Zeiss Stemi SV 11 stereomicroscope. All charcoal particles per sample were counted and grouped according to size classes and morphology. Size classes (“small”: 150–300 µm, “medium”: >300–500 µm, “large”: >500 µm) were estimated by measuring a particle’s longest axis with needles of a known tip diameter22. For charcoal morphology we applied the classification of morphotypes by Enache and Cumming105, and further grouped these into “irregular”, “angular”, and “elongated” morphologies22. For four of the sediment cores, the length to width (L:W) ratios of all counted particles were recorded, determined with the help of an ocular micrometer (Supplementary Table 3).

Charcoal concentrations with age information were interpolated to the median temporal resolution of each sediment core, before calculating charcoal accumulation rates (CHAR), using the “pretreatment” function of the R package “paleofire”106 (v. 1.2.4; Supplementary Fig. 2). CHAR represents wildfire activity as the amount of biomass burned, integrating individual fire regime attributes of extent, intensity, or severity107,108. We therefore use CHAR to interpret reconstructed levels of biomass burning through time as changing wildfire activity, and, when viewed in context of the environment and the drivers behind reconstructed changes, as wildfire dynamics. Using the same R package, following Blarquez et al., a charcoal composite curve was created106. A total of 12 charcoal records was used, including the eight new charcoal records presented in this study, as well as four records previously published and available in the Global Paleofire Database43 (GPD; available at www.paleofire.org; data obtained in April 2024): Lake Sugun20, Maralay Alaas21, Lake Khamra35, and Lake Satagay22. Other charcoal records in Yakutia registered in the GPD were excluded, either because they only recorded microscopic charcoal on non-contiguous pollen slide samples, and/or because they lacked a contiguous sampling scheme for macroscopic charcoal. All charcoal records were manually added to the “paleofire” R package routine in the standard “CharAnalysis” file format65 (function “pfAddData”). Following common recommendations36,106, charcoal records were transformed using a MinMax re-scaling, a Box-Cox transformation for homogenizing variance across records109, and a z-score standardization, all for the base period of −70 to 11,000 years BP (function “pfTransform”). We chose this base period in order to standardize the data relative to an internally consistent, Holocene-scale baseline, to preserve long-term trends, and to derive z-scores that clearly show deviations above or below this Holocene baseline. A comparison of the effects of different base period choices is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The composite curve was created following an established method43,48,110, binning individual records into non-overlapping 100-year bins and applying a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) at a window width of 1000 years (function “pfCompositeLF”). Confidence intervals were generated using the distribution of 1000 bootstrapped replicates from the binned records106.

Simulations in LAVESI-FIRE

We applied the individual-based, spatially explicit forest model LAVESI (Larix Vegetation Simulator), which has been described in detail and applied in previous publications111,112,113. Specifically, we used the fire-enabled version LAVESI-FIRE42. In short, a simulation in LAVESI-FIRE consists of trees and seeds and a litter layer on top of a permafrost active layer, all within a gridded simulation area (0.2 × 0.2 m). LAVESI-FIRE is individual-based in that it features individual trees and seeds, and their interactions with each other and the environment114. The model simulates annual cycles of individual tree establishment, growth, competition, and mortality, driven by climatic forcing data of monthly temperature and precipitation, as well as underlying environmental data (elevation, slope, topographic wetness index). It is capable of representing climate-driven changes of wildfire activity, where, based on a monthly determined fire probability, fires can stochastically occur within the simulation area and impact tree and seed mortality and the litter layer height, depending on local fire intensity. Fires can occur as long as fuel material (trees, litter layer) is available and the topographic wetness index is not saturated, resulting in the possibility of re-burns in the following simulation year. To represent gradual fuel-fire relationships, we here additionally implemented the possibility of changing the fuel availability to mediate each affected grid cell’s fire intensity (Supplementary Note 1). Fuel availability is here represented by a unitless fuel factor, derived from local tree density and the litter layer height, mediating the primarily climate-driven fire intensity in each grid cell. The fuel factor can be manually adjusted to test for the impact of different fuel availability scenarios (e.g., a fuel factor reduced by 50% correspondingly represents the litter layer height and tree density reduced by 50%).

We localized the model’s environmental inputs for an exemplary simulation area of 1980 × 1980 m, located in a representative alaas landscape between our study sites in Central Yakutia, using the TanDEM-X 30 m digital elevation model product115. For climatic forcing we used modeled data from transient simulations with MPI-ESM-CR spanning 25,000 years BP116,117, localized at the simulation area location by monthly mean-fitting to the corresponding overlapping period with the interpolated observational data from CRU-TS v4.07118. The MPI-ESM-CR simulations were forced by orbital parameters/insolation, greenhouse gas emissions, and subject to a land-sea mask, ice sheets, and meltwater discharge via river routing according to the PMIP4 deglaciation protocol119. The simulations were recently found to be among the best for representing multi-centennial-scale surface climate variability since the Last Glacial Maximum52, and MPI-ESM simulations were used before in various studies comparing simulated to reconstructed environmental data38,42,120. The fire module was localized following Glückler et al., establishing a linear model between monthly burned area, represented by burned pixels from satellite observations between 2001 to 2022 CE in a 200 km buffer around Yakutsk (MCD64A1 product)121, and temperature and precipitation from CRU-TS v4.0742. Thresholds between mild, severe, and extreme monthly fire probability were set as the third quantile and the maximum non-outlier value (upper whisker) of the boxplot distribution of all fire probability values generated with the MPI-ESM-CR climate input.

We ran ten simulations for each of two scenarios, respectively. To represent the alternative hypothesis, the impact of solely climatic forcing on fire regime changes, in the “normal fuel”-scenario no changes were made regarding the model’s fuel availability. In the “reduced fuel”-scenario, however, we introduced a constant limit to fuel availability of 20% from 1200 CE (the timing of a known cultural shift to pastoralism) to present. This was done to test the hypothesis that such an additional fuel limitation, as one suggested net impact of human activities in the region, improves the fit between simulated and reconstructed trends of biomass burning. LAVESI-FIRE simulation output of annual burned area, corresponding to the number of burned grid cells of the simulation area, was pre-smoothed with locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS; span of 0.1) to highlight multi-centennial variability comparable to the charcoal composite curve. All simulated burned area time series were then filtered to an equidistant temporal resolution as the charcoal composite, using a custom version of the function “CorrIrregTimeser” of the R package “corit”39,122. Then, the median and interquartile range of all smoothed time series of the ten simulation repeats per scenario were calculated. In order to not only compare the two time series on a broad millennial scale throughout the Holocene, but test for shorter, multi-centennial correlations, we apply a rolling window correlation approach via the R package “RolWinMulCor”123. This approach displays the correlation results for a full range of different window widths in a heatmap, thereby not relying on an individual, fixed window width, and also enabling significance testing corrected for multiple testing with the Benjamini and Hochberg method124,125. We calculated the rolling window correlation heatmap for window widths between 110 and 10,010 years (function “rolwincor_heatmap”). We accounted for the strong autocorrelation expected in smoothed paleoecological and simulated time series by using a Monte Carlo approach. One of the time series was phase-randomized 1000 times following Ebisuzaki to generate surrogate data that preserve the original autocorrelation structure126. These randomized time series were used to create a null distribution of correlation coefficients, both for the correlation of full time series and across all window widths of the rolling window correlation analysis. Observed correlations were then compared against this surrogate distribution using two-sided empirical significance testing, thereby accounting for serial dependence. Finally, we tested for potential impacts of internal model dynamics on the variability of simulated burned area by comparing the simulated burned area of all 20 simulations to the purely climate-derived fire probability rating. Internal model dynamics and stochastic elements mediate, but do not conceal the climate-derived variability in simulated burned area (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The charcoal and radiocarbon age data generated during the current study are available via PANGAEA under https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.974511 (127) and https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.974676 (128). LAVESI-FIRE simulation output data are available via Zenodo under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14626968 (129).

Code availability

The LAVESI-FIRE model code used during the current study is available via Zenodo under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17477084 (130).

References

Cunningham, C. X., Williamson, G. J. & Bowman, D. M. J. S. Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1420–1425 (2024).

Jones, M. W. et al. Global and regional trends and drivers of fire under climate change. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2020RG000726 (2022).

Kharuk, V. I. et al. Wildfires in the Siberian taiga. Ambio 50, 1953–1974 (2021).

Li, N. G. Strong tolerance to freezing is a major survival strategy in insects inhabiting central Yakutia (Sakha Republic, Russia), the coldest region on earth. Cryobiology 73, 221–225 (2016).

Li, Y., Janssen, T. A. J., Chen, R., He, B. & Veraverbeke, S. Trends and drivers of Arctic-boreal fire intensity between 2003 and 2022. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 172020 (2024).

Narita, D., Gavrilyeva, T. & Isaev, A. Impacts and management of forest fires in the Republic of Sakha, Russia: a local perspective for a global problem. Polar Sci 27, 100573 (2021).

Canosa, I. V. et al. Wildfire adaptation in the Russian Arctic: a systematic policy review. Clim. Risk Manag. 39, 100481 (2023).

Tomshin, O. & Solovyev, V. Features of the extreme fire season of 2021 in Yakutia (Eastern Siberia) and heavy air pollution caused by biomass burning. Remote Sens. 14, 4980 (2022).

Vinokurova, L., Solovyeva, V. & Filippova, V. When ice turns to water: forest fires and indigenous settlements in the republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Sustainability 14, 4759 (2022).

Burton, C. et al. Global burned area increasingly explained by climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 1186–1192 (2024).

Furyaev, V. V., Vaganov, E. A., Tchebakova, N. M. & Valendik, E. N. Effects of fire and climate on successions and structural changes in the Siberian boreal forest. Eurasian J. For. Res. 2, 1–15 (2001).

Shestakova, T. A. et al. Tracking ecosystem stability across boreal Siberia. Ecol. Indic. 169, 112841 (2024).

Christianson, A. C. et al. Centering indigenous voices: the role of fire in the boreal forest of North America. Curr. For. Rep. 8, 257–276 (2022).

Mulverhill et al. Wildfires are spreading fast in Canada –we must strengthen forests for the future. Nature 633, 282–285 (2024).

Kimmerer, R. W. & Lake, F. K. The role of indigenous burning in land management. J. For. 99, 36–41 (2001).

Marlon, J. R. et al. Reconstructions of biomass burning from sediment-charcoal records to improve data–model comparisons. Biogeosciences 13, 3225–3244 (2016).

Abaimov, A. P. Geographical distribution and genetics of siberian larch species. In Permafrost Ecosystems: Siberian Larch Forests 41–58 (Springer, 2010).

Pupysheva, M. A. & Blyakharchuk, T. A. Fires and their significance in the Earth’s post-glacial period: a review of methods, achievements, groundwork. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 16, 303–315 (2023).

Whitlock, C. & Larsen, C. Charcoal as a fire proxy. In Tracking Environmental Change Using Lake Sediments, Vol. 3: Terrestrial, Algal, and Siliceous Indicators, (eds. Smol, J. P. Birks, H. J. B. & Last W. M.) 75–97 (Springer, 2003).

Katamura, F., Fukuda, M., Bosikov, N. P. & Desyatkin, R. V. Charcoal records from thermokarst deposits in central Yakutia, eastern Siberia: implications for forest fire history and thermokarst development. Quat. Res. 71, 36–40 (2009a).

Katamura, F., Fukuda, M., Bosikov, N. P. & Desyatkin, R. V. Forest fires and vegetation during the Holocene in central Yakutia, eastern Siberia. J. For. Res. 14, 30–36 (2009b).

Glückler, R. et al. Holocene wildfire and vegetation dynamics in Central Yakutia, Siberia, reconstructed from lake-sediment proxies. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 962906 (2022).

Jain, P., Castellanos-Acuna, D., Coogan, S. C. P., Abatzoglou, J. T. & Flannigan, M. D. Observed increases in extreme fire weather driven by atmospheric humidity and temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 63–70 (2022).

Sayedi, S. S. et al. Assessing changes in global fire regimes. Fire Ecol. 20, 18 (2024).

Stieg, A. et al. Hydroclimatic anomalies detected by a sub-decadal diatom oxygen isotope record of the last 220 years from Lake Khamra, Siberia. Clim. Past 20, 909–933 (2024).

Girardin, M. P. et al. Boreal forest cover was reduced in the mid-Holocene with warming and recurring wildfires. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–12 (2024).

Bird, M. I. et al. Late Pleistocene emergence of an anthropogenic fire regime in Australia’s tropical savannahs. Nat. Geosci. 17, 233–240 (2024).

Kuzmin, Y. V., Bykov, N. I., & Krupochkin, E. P. Humans and nature in Siberia: from the Palaeolithic to the Middle Ages. In Humans in the Siberian Landscapes: Ethnocultural Dynamics and Interaction with Nature and Space, (eds. Bocharnikov, V. N. & Steblyanskaya A. N.) 59–87 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Pitulko, V. V. et al. Early human presence in the Arctic: evidence from 45,000-year-old mammoth remains. Science 351, 260–263 (2016).

Sikora, M. et al. The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene. Nature 570, 182–188 (2019).

Kuzmin, Y. V. Reconstructing human−environmental relationship in the Siberian Arctic and sub-arctic: a Holocene overview. Radiocarbon 65, 431–442 (2023).

Fedorova, S. A. et al. Autosomal and uniparental portraits of the native populations of Sakha (Yakutia): implications for the peopling of Northeast Eurasia. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 127 (2013).

Okladnikov, A. P. Yakutia Before its Incorporation into the Russian State. In Anthropology of the North: Translations from Russian Sources (ed. Michael H. N.) (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1970).

Crate, S. A. Once Upon the Permafrost: Knowing Culture and Climate Change in Siberia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2022).

Glückler, R. et al. Wildfire history of the boreal forest of south-western Yakutia (Siberia) over the last two millennia documented by a lake-sediment charcoal record. Biogeosciences 18, 4185–4209 (2021).

Power, M. J. et al. Changes in fire regimes since the Last Glacial Maximum: an assessment based on a global synthesis and analysis of charcoal data. Clim. Dyn. 30, 887–907 (2008).

Marlon, J. R. et al. Global biomass burning: a synthesis and review of Holocene paleofire records and their controls. Quat. Sci. Rev. 65, 5–25 (2013).

Dallmeyer, A. et al. The deglacial forest conundrum. Nat. Commun. 13, 6035 (2022).

Herzschuh, U. et al. Regional pollen-based Holocene temperature and precipitation patterns depart from the Northern Hemisphere mean trends. Clim. Past 19, 1481–1506 (2023).

Sato, H., Kobayashi, H. & Delbart, N. Simulation study of the vegetation structure and function in eastern Siberian larch forests using the individual-based vegetation model SEIB-DGVM. For. Ecol. Manag. 259, 301–311 (2010).

Shuman et al. Fire disturbance and climate change: implications for Russian forests. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 035003 (2017).

Glückler, R., Gloy, J., Dietze, E., Herzschuh, U. & Kruse, S. Simulating long-term wildfire impacts on boreal forest structure in Central Yakutia, Siberia, since the Last Glacial Maximum. Fire Ecol. 20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00238-8 (2024).

Power, M. J., Marlon, J. R., Bartlein, P. J. & Harrison, S. P. Fire history and the Global Charcoal Database: a new tool for hypothesis testing and data exploration. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 291, 52–59 (2010).

Kelly, R. et al. Recent burning of boreal forests exceeds fire regime limits of the past 10,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13055–13060 (2013).

Kirillina, K., Shvetsov, E. G., Protopopova, V. V., Thiesmeyer, L. & Yan, W. Consideration of anthropogenic factors in boreal forest fire regime changes during rapid socio-economic development: case study of forestry districts with increasing burnt area in the Sakha Republic, Russia. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 035009 (2020).

Barhoumi, C. et al. Holocene fire regime changes in the southern Lake Baikal region influenced by climate-vegetation-anthropogenic activity interactions. Forests 12, 978 (2021).

Krikunova, A. I. et al. Vegetation and fire history of the Lake Baikal Region since 32 ka BP reconstructed through microcharcoal and pollen analysis of lake sediment from Cis- and Trans-Baikal. Quat. Sci. Rev. 340, 108867 (2024).

Marlon, J. R. et al. Climate and human influences on global biomass burning over the past two millennia. Nat. Geosci. 1, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo313 (2008).

Wirth, C. Fire regime and tree diversity in boreal forests: implications for the carbon cycle. In Forest Diversity and Function: Temperate and Boreal Systems (eds. Scherer-Lorenzen, M. Körner, C. & Schulze E.-D.) (Springer, 2005), 309–344.

De Groot, W. J. et al. A comparison of Canadian and Russian boreal forest fire regimes. For. Ecol. Manag. 294, 23–34 (2013).

Rogers, B. M., Soja, A. J., Goulden, M. L. & Randerson, J. T. Influence of tree species on continental differences in boreal fires and climate feedbacks. Nat. Geosci. 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2352 (2015).

Ziegler, E. et al. Patterns of changing surface climate variability from the Last Glacial Maximum to present in transient model simulations. Clim. Past 21, 627–659 (2025).

Marlon, J. R. et al. Wildfire responses to abrupt climate change in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2519–2524 (2009).

Tarasov, P. et al. Vegetation and climate dynamics during the Holocene and Eemian interglacials derived from Lake Baikal pollen records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 252, 440–457 (2007).

Bezrukova, E. V., Belov, A. V. & Orlova, L. A. Holocene vegetation and climate variability in North Pre-Baikal region, East Siberia, Russia. Quat. Int. 237, 74–82 (2011).

Baumer, M. M. et al. Climatic and environmental changes in the Yana Highlands of north-eastern Siberia over the last c. 57000 years, derived from a sediment core from Lake Emanda. Boreas 50, 114–133 (2021).

Hughes-Allen, L. et al. 14,000-year carbon accumulation dynamics in a Siberian lake reveal catchment and lake productivity changes. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 710257 (2021).

Meister, P. et al. A global compilation of diatom silica oxygen isotope records from lake sediment–trends and implications for climate reconstruction. Clim. Past 20, 363–392 (2024).

Popp, S. et al. Palaeoclimate signals as inferred from stable-isotope composition of ground ice in the Verkhoyansk foreland, Central Yakutia. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 17, 119–132 (2006).

Thomas, E. R. et al. The 8.2ka event from Greenland ice cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 70–81 (2007).

Parker, S. E. & Harrison, S. P. The timing, duration and magnitude of the 8.2 ka event in global speleothem records. Sci. Rep. 12, 10542 (2022).

Ulrich, M. et al. Rapid thermokarst evolution during the mid-Holocene in Central Yakutia, Russia. Holocene 27, 1899–1913 (2017).

Harding, P. et al. Hydrological (in)stability in Southern Siberia during the Younger Dryas and early Holocene. Glob. Planet. Change 195, 103333 (2020).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Higuera, P. E., Brubaker, L. B., Anderson, P. M., Hu, F. S. & Brown, T. A. Vegetation mediated the impacts of postglacial climate change on fire regimes in the south-central Brooks Range, Alaska. Ecol. Monogr. 79, 201–219 (2009).

Velichko, A. A., Andreev, A. A. & Klimanov, V. A. Climate and vegetation dynamics in the tundra and forest zone during the Late Glacial and Holocene. Quat. Int. 71–96 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(96)00039-0 (1997).

Müller, S., Tarasov, P. E., Andreev, A. A. & Diekmann, B. Late Glacial to Holocene environments in the present-day coldest region of the Northern Hemisphere inferred from a pollen record of Lake Billyakh, Verkhoyansk Mts, NE Siberia. Clim. Past 5, 73–84 (2009).

Andreev, A. A. et al. Late Quaternary paleoenvironmental reconstructions from sediments of Lake Emanda (Verkhoyansk Mountains, East Siberia). J. Quat. Sci. 37, 884–899 (2022).

Baisheva, I. et al. Late Glacial and Holocene vegetation and lake changes in SW Yakutia, Siberia, inferred from sedaDNA, pollen, and XRF data. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1354284 (2024).

Schulte, L. et al. Larix species range dynamics in Siberia since the Last Glacial captured from sedimentary ancient DNA. Commun. Biol. 5, 1–11 (2022).

Abaimov, A. P. & Sofronov, M. A. The main trends of post-fire succession in near-tundra forests of central Siberia. In Fire in Ecosystems of Boreal Eurasia. Forestry Sciences (eds. Goldammer, J. G. & Furyaev V. V.) 372–386 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996).

Andreev, A. A. & Tarasov, P. E. Northern Asia, in The Encyclopedia of Quaternary Science (ed. Elias, S. A.) 164–172 (Elsevier, 2013).

Coughlan, M. R., Magi, B. I. & Derr, K. M. A global analysis of hunter-gatherers, broadcast fire use, and lightning-fire-prone landscapes. Fire 1, 41 (2018).

Roos, C. I., Williamson, G. J. & Bowman, D. M. J. S. Is anthropogenic pyrodiversity invisible in paleofire records? Fire 2, 42 (2019).

Ryabogina, N. E., Nesterova, M. I., Utaygulova, R. R. & Trubitsyna, E. D. Forest fires in southwest Western Siberia: the impact of climate and economic transitions over 9000 years. J. Quat. Sci. 39, 432–442 (2024).

Nomokonova, T., Losey, R. J., Weber, A., Goriunova, O. I. & Novikov, A. G. Late Holocene subsistence practices among cis-baikal pastoralists, Siberia: zooarchaeological insights from Sagan-Zaba II. Asian Perspect 49, 157–179 (2010).

Dietze, E. et al. Holocene fire activity during low-natural flammability periods reveals scale-dependent cultural human-fire relationships in Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 201, 44–56 (2018).

Roos, C. I., Zedeño, M. N., Hollenback, K. L. & Erlick, M. M. H. Indigenous impacts on North American Great Plains fire regimes of the past millennium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8143–8148 (2018).

Rouet-Leduc, J. et al. Effects of large herbivores on fire regimes and wildfire mitigation. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 2690–2702 (2021).

Roos, C. I. et al. Native American fire management at an ancient wildland–urban interface in the Southwest United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018733118 (2021).

Roos, C. I. et al. Indigenous fire management and cross-scale fire-climate relationships in the Southwest United States from 1500 to 1900 CE. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq3221 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. Climatic factors and human population changes in Eurasia between the Last Glacial Maximum and the early Holocene. Global Planet. Change 221, 104054 (2023).

Zlojutro, M. et al. Coalescent simulations of Yakut mtDNA variation suggest small founding population. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 139, 474–482 (2009).

Keyser, C. et al. The ancient Yakuts: a population genetic enigma. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20130385 (2015).

Dolgikh, B. O. Tribal Composition of Siberian Peoples (Academy of Sciences, 1960).

Pakendorf, B. et al. Investigating the effects of prehistoric migrations in Siberia: genetic variation and the origins of Yakuts. Hum. Genet. 120, 334–53 (2006).

Soloviev, P. A. The Cryolithozone of the Northern Part of the Lena-Amga Interfluve (Moscow: Academy of Sciences, 1959).

Crate, S. et al. Permafrost livelihoods: a transdisciplinary review and analysis of thermokarst-based systems of indigenous land use. Anthropocene 18, 89–104 (2017).

Baisheva, I. et al. Permafrost-thaw lake development in Central Yakutia: sedimentary ancient DNA and element analyses from a Holocene sediment record. J. Paleolimnol. 70, 95–112 (2023).

Naumov, A., Akimova, V., Sidorova, D. & Topnikov, M. Agriculture and land use in the North of Russia: case study of Karelia and Yakutia. Open Geosci 12, 1497–1511 (2020).

Solovyeva, V., Vinokurova, L. & Filippova, V. Fire and water: indigenous ecological knowledge and climate challenges in the republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Anthropol. Archeol. Eurasia 59, 242–266 (2022).

Achard, F., Eva, H. D., Mollicone, D. & Beuchle, R. The effect of climate anomalies and human ignition factor on wildfires in Russian boreal forests. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 2329–2337 (2007).

Shvetsov, E. G., Kukavskaya, E. A., Shestakova, T. A., Laflamme, J. & Rogers, B. M. Increasing fire and logging disturbances in Siberian boreal forests: a case study of the Angara region. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 115007 (2021).

Pyne, S. J. Wild hearth a prolegomenon to the cultural fire history of Northern Eurasia. In Fire in Ecosystems of Boreal Eurasia (eds Goldammer, J. G. & Furyaev, V. V.) 21–44 (Springer Netherlands, 1996).

Takakura, H. et al. Permafrost and Culture: Global Warming and the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), Russian Federation (in English). Center for Northeast Asian Studies Report 26. (2021).

Fedorov, A. N. et al. Permafrost-landscape map of the republic of sakha (Yakutia) on a Scale 1:1,500,000. Geosciences 8, 465 (2018).

Köster, K. et al. Impacts of wildfire on soil microbiome in Boreal environments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 22, 100258 (2021).

Glückler, R. et al. Setting up a baseline for the Yakutian-Chukotkan Monitoring transect: lake inventories including water chemistry, lake sediment coring and UAV-surveys. In Reports on Polar and Marine Research: Russian-German Expeditions to Siberia in 2021 (eds. Morgenstern, A. et al.) (Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, 2023).

Mollenhauer, G., Grotheer, H., Gentz, T., Bonk, E. & Hefter, J. Standard operation procedures and performance of the MICADAS radiocarbon laboratory at Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Germany. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 496, 45–51 (2021).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 Northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Blaauw, M. & Christen, J. A. Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process. Bayesian Anal 6, 457–474 (2011).

R Core Team R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023).

Walker, M. J. C. et al. Formal subdivision of the Holocene series/epoch: a discussion paper by a working group of INTIMATE (Integration of ice-core, marine and terrestrial records) and the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (International Commission on Stratigraphy). J. Quat. Sci. 27, 649–659 (2012).

Hawthorne, D. et al. Global Modern Charcoal Dataset (GMCD): a tool for exploring proxy-fire linkages and spatial patterns of biomass burning. Quat. Int. 488, 3–17 (2018).

Enache, M. D. & Cumming, B. F. Charcoal morphotypes in lake sediments from British Columbia (Canada): an assessment of their utility for the reconstruction of past fire and precipitation. J. Paleolimnol. 38, 347–363 (2007).

Blarquez, O. et al. paleofire: an R package to analyse sedimentary charcoal records from the Global Charcoal Database to reconstruct past biomass burning. Comput. Geosci. 72, 255–261 (2014).

Adolf, C. et al. The sedimentary and remote-sensing reflection of biomass burning in Europe. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 199–212 (2018).

Hennebelle, A. et al. The reconstruction of burned area and fire severity using charcoal from boreal lake sediments. Holocene 30, 1400–1409 (2020).

Box, G. E. P. & Cox, D. R. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 26, 211–252 (1964).

Daniau, A.-L. et al. Predictability of biomass burning in response to climate changes. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB4007 (2012).

Kruse, S., Wieczorek, M., Jeltsch, F. & Herzschuh, U. Treeline dynamics in Siberia under changing climates as inferred from an individual-based model for Larix. Ecol. Model. 338, 101–121 (2016).

Kruse, S., Gerdes, A., Kath, N. J. & Herzschuh, U. Implementing spatially explicit wind-driven seed and pollen dispersal in the individual-based larch simulation model: LAVESI-WIND 1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 4451–4467 (2018).

Kruse, S. et al. Novel coupled permafrost–forest model (LAVESI–CryoGrid v1.0) revealing the interplay between permafrost, vegetation, and climate across eastern Siberia. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 2395–2422 (2022).

Grimm, V. & Railsback, S. F. Individual-based modeling and ecology. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400850624 (Princeton University Press, 2005).

Rizzoli, P. et al. Generation and performance assessment of the global TanDEM-X digital elevation model. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 132, 119–139 (2017).

Kapsch, M.-L., Mikolajewicz, U., Ziemen, F. A., Rodehacke, C. B. & Schannwell, C. Analysis of the surface mass balance for deglacial climate simulations. Cryosphere 15, 1131–1156 (2021).

Kapsch, M.-L., Mikolajewicz, U., Ziemen, F. & Schannwell, C. Ocean response in transient simulations of the last deglaciation dominated by underlying ice-sheet reconstruction and method of meltwater distribution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096767 (2022).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

Ivanovic, R. F. et al. Transient climate simulations of the deglaciation 21–9 thousand years before present (version 1) – PMIP4 core experiment design and boundary conditions. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2563–2587 (2016).

Li, C. et al. Global biome changes over the last 21,000 years inferred from model–data comparisons. Clim. Past 21, 1001–1024 (2025).

Giglio, L., Boschetti, L., Roy, D. P., Humber, M. L. & Justice, C. O. The collection 6 MODIS burned area mapping algorithm and product. Remote Sens. Environ. 217, 72–85 (2018).

Reschke, M., Kunz, T. & Laepple, T. Comparing methods for analysing time scale dependent correlations in irregularly sampled time series data. Comput. Geosci. 123, 65–72 (2019).

Polanco-Martínez, J. M. RolWinMulCor: an R package for estimating rolling window multiple correlation in ecological time series. Ecol. Inform. 60, 101163 (2020).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57, 289–300 (1995).

Polanco-Martínez, J. M. Dynamic relationship analysis between NAFTA stock markets using nonlinear, nonparametric, non-stationary methods. Nonlinear Dyn 97, 369–389 (2019).

Ebisuzaki, W. A method to estimate the statistical significance of a correlation when the data are serially correlated. J. Clim. 10, 2147–2153 (1997).

Glückler, R. & Herzschuh, U. Macroscopic charcoal records from eight sediment cores in central and eastern Yakutia, Siberia. PANGAEA. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.974511 (2025a).

Glückler, R. & Herzschuh, U. Radiocarbon ages of eight sediment cores in central and eastern Yakutia, Siberia. PANGAEA. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.974676 (2025b).

Glückler, R. & Kruse, S. LAVESI-FIRE simulation output near Maya, Central Yakutia, Siberia (v1.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14626969 (2025).

Stefan Kruse, Glückler, R. & Gloy, J. StefanKruse/LAVESI: LAVESI-FIRE v1.1 (FIRE_v1.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17477084 (2025).

Acknowledgements

R.G. was funded by AWI INSPIRES (International Science Program for Integrative Research) and JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) as an International Research Fellow. L.P., E.Z., and I.B. were supported by the framework of science project FSRG-2023-0027. Research was supported by funding from the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize (DFG; German Research Foundation) to U.H. We thank the team of the German-Russian “Yakutia 2021” expedition. W. Finsinger kindly provided support with R. Thanks to P. Uchanov for help in the laboratory and to everyone supporting sediment core subsampling: J. Courtin, V. Döpper, A. Eichner, L. Enguehard, L. Grimm, S. Haupt, P. Hauter, A. Korup, H.S. Malik, P. Meister, C. Messner, R. Paasch, A. Prasannakumar, K. Schildt, E. Topp-Johnson, and J. Wagner. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.H., S.K., and L.P. designed and led the fieldwork, supported by R.G. R.G., U.H., E.Z., I.B., and A.S. conducted fieldwork at the lake sites. R.G. designed the charcoal analysis study, supervised by U.H. and E.D. R.G. subsampled the sediment cores. R.G. prepared the age dating process and created the chronologies. R.G. conducted the charcoal-related laboratory work and data analysis, supported by S.T. and E.D. R.G. wrote the initial version of the manuscript, supervised by U.H and supported by A.A. All authors reviewed the initial manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Philip Higuera and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jiaoyang Ruan and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glückler, R., Dietze, E., Andreev, A.A. et al. Human activity may have influenced Holocene wildfire dynamics in boreal eastern Siberia. Commun Earth Environ 7, 147 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03169-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03169-1