Abstract

As societies age, policy makers need tools to understand how demographic aging will affect population health and to develop programs to increase healthspan. The current metrics used for policy do not distinguish differences caused by early-life factors, like prenatal care and nutrition, from those caused by ongoing changes in people’s bodies that are due to aging and that may be modifiable. Here we introduce an adapted Pace of Aging method designed to quantify differences between individuals and populations in the speed of aging-related health declines. The adapted Pace of Aging method, implemented in parallel in data from the US Health and Retirement Study and in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (combined n = 19,045), integrates longitudinal data on blood biomarkers, physical measurements and functional tests. It reveals stark differences in rates of aging between population subgroups and demonstrates strong and consistent prospective associations with incident morbidity, disability and mortality. This adapted and generalizable method to measure Pace of Aging can advance the population science of healthy longevity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data for the US HRS were obtained from the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan (https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products). Access to blood biomarker and genomic data require investigators to commit not to attempt to identify participants.

Data for the ELSA were obtained from the UK Data Service (accession GN 33368; https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-Series-200011).

Code availability

All analysis code available at https://github.com/Columbia-Aging-Center-GeroScience-Core/Balachandran_et_al_Nature_Aging_2025.

References

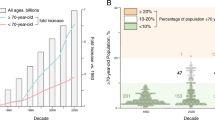

Lutz, W., Sanderson, W. & Scherbov, S. The coming acceleration of population ageing. Nature 451, 716–716 (2008).

Balachandran, A., de Beer, J., James, K. S., van Wissen, L. & Janssen, F. Comparison of population aging in Europe and Asia using a time-consistent and comparative aging measure. J. Aging Health 32, 340–351 (2020).

Crimmins, E. M. Lifespan and healthspan: past, present, and promise. Gerontologist 55, 901–911 (2015).

Partridge, L., Deelen, J. & Slagboom, P. E. Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature 561, 45–56 (2018).

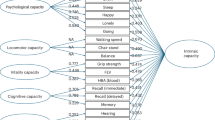

Beard, J. R., Si, Y., Liu, Z., Chenoweth, L. & Hanewald, K. Intrinsic capacity: validation of a new WHO concept for healthy aging in a longitudinal Chinese study. J. Gerontol. A. 77, 94–100 (2022).

Crimmins, E. M. & Saito, Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970-1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Soc. Sci. Med. 52, 1629–1641 (2001).

Ailshire, J. A., Beltran-Sanchez, H. & Crimmins, E. M. Social characteristics and health status of exceptionally long-lived Americans in the Health and Retirement Study. J. Am. Geriatrics Soc. 59, 2241–2248 (2011).

Seaman, R. et al. Rethinking morbidity compression. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 381–388 (2020).

Payne, C. F. Expansion, compression, neither, both? Divergent patterns in healthy, disability-free, and morbidity-free life expectancy across US birth cohorts, 1998–2016. Demography 59, 949–973 (2022).

Balachandran, A. Population Ageing in Europe and Asia: Beyond Traditional Perspectives. Thesis, Univ. Groningen (2020).

Skirbekk, V. et al. The health-adjusted dependency ratio as a new global measure of the burden of ageing: a population-based study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 3, e332–e338 (2022).

Skirbekk, V. F., Staudinger, U. M. & Cohen, J. E. How to measure population aging? The answer is less than obvious: a review. Gerontology 65, 136–144 (2019).

Ferrucci, L., Levine, M. E., Kuo, P.-L. & Simonsick, E. M. Time and the metrics of aging. Circ. Res. 123, 740–744 (2018).

Beard, J. R. et al. The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 387, 2145–2154 (2016).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E4104–E4110 (2015).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Quantification of the pace of biological aging in humans through a blood test, the DunedinPoAm DNA methylation algorithm. eLife 9, e54870–e54870 (2020).

Lee, J., Phillips, D., Wilkens, J. & Team G to GAD. Gateway to Global aging data: resources for cross-national comparisons of family, social environment, and healthy aging. J. Gerontol. B 76, S5–S16 (2021).

Cohen, A. A. et al. A novel statistical approach shows evidence for multi-system physiological dysregulation during aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 134, 110–117 (2013).

Klemera, P. & Doubal, S. A new approach to the concept and computation of biological age. Mech. Ageing Dev. 127, 240–248 (2006).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 10, 573 (2018).

Graf, G. H. J. et al. Social mobility and biological aging among older adults in the United States. PNAS Nexus 1, pgac029 (2022).

Graf, G. H. et al. Testing black-white disparities in biological aging among older adults in the United States: analysis of DNA-methylation and blood-chemistry methods. Am. J. Epidemiol. 191, 613–625 (2022).

Belsky, D. W. et al. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. eLife 11, e73420–e73420 (2022).

Higgins-Chen, A. T. et al. A computational solution for bolstering reliability of epigenetic clocks: Implications for clinical trials and longitudinal tracking. Nat. Aging. 2, 644–661 (2022).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 11, 303–303 (2019).

Faul, J. D. et al. Epigenetic-based age acceleration in a representative sample of older Americans: associations with aging-related morbidity and mortality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2215840120 (2023).

Poulton, R., Guiney, H., Ramrakha, S. & Moffitt, T. E. The Dunedin Study after half a century: reflections on the past, and course for the future. J. R. Soc. N.Z. 53, 446–465 (2023).

Finch, C. E. & Crimmins, E. M. Constant molecular aging rates vs. the exponential acceleration of mortality. PNAS 113, 1121–1123 (2016).

Kuo, P. L. et al. Longitudinal phenotypic aging metrics in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Nat. Aging 2, 635–643 (2022).

Newman, A. B. et al. Trajectories of function and biomarkers with age: the CHS All Stars Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1135–1145 (2016).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Impact of early personal-history characteristics on the Pace of Aging: implications for clinical trials of therapies to slow aging and extend healthspan. Aging Cell 16, 644–651 (2017).

Schrempft, S. et al. Associations between life-course socioeconomic conditions and the Pace of Aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 77, 2257–2264 (2022).

Newman, A. B., Odden, M. C. & Cauley, J. A. in Handbook of Epidemiology 1–37 (Springer, 2023).

Schmitz, L. L. & Duque, V. In utero exposure to the Great Depression is reflected in late-life epigenetic aging signatures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2208530119–e2208530119 (2022).

Ye, P. et al. A scoping review of national policies for healthy ageing in mainland China from 2016 to 2020. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 12, 100168 (2021).

Pan American Health Organization. Healthy aging - PAHO/WHO. https://www.paho.org/en/healthy-aging (2024).

AARP International. Innovation and leadership in healthy aging. https://www.aarpinternational.org/resources/healthy-aging (2024).

Elliott, M. L. et al. Disparities in the pace of biological aging among midlife adults of the same chronological age have implications for future frailty risk and policy. Nat. Aging 1, 295–308 (2021).

Sanders, J. L. et al. Do changes in circulating biomarkers track with each other and with functional changes in older adults? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69A, 174–181 (2014).

Cohen, A. A. et al. A complex systems approach to aging biology. Nat. Aging 2, 580–591 (2022).

Bugliari, D. et al. RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2020 (V1) Documentation (RAND, 2023); https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/portfolios/aging-longevity/dataprod/hrs-data.html

Kim, J. K., Faul, J., Weir, D. R. & Crimmins, E. M. Dried blood spot based biomarkers in the Health and Retirement Study: 2006 to 2016. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 36, e23997 (2024).

Phillips, D., Lin, Y. C., Wight, J., Chien, S. & Lee, J. Harmonized ELSA documentation. Version C. https://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/5050/mrdoc/pdf/5050_harmonized_elsa_g3_2002-2019.pdf (2014).

Langa, K. M. et al. A comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 51–58 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01AG061378, Russel Sage Foundation BioSS grant 1810-08987 and the Robert N Butler Columbia Aging Center. A.F. is supported by T32AI114398. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. D.W.B. is a fellow of the CIFAR CBD Network. The HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant no. U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W.B. conceived the study; A.B., M.K., H.P., Y.S. and D.W.B. designed the study and analyzed the data. A.B., M.K. and D.W.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. A.B., H.P. and D.W.B. had complete access to the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.W.B., A.C. and T.E.M. are inventors of DunedinPACE, a Duke University and University of Otago invention licensed to TruDiagnostic. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Aging thanks Joris Deelen, David Rehkopf, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Biomarker Adjustment.

The figure shows original and period-effect-adjusted levels of biomarkers included in Pace of Aging analysis. Panel A shows data for the US Health and Retirement Study. Panel B shows data for the English Longitudinal Study of Aging. We conducted analysis to adjust for period effects as follows: We fitted regression models to each biomarker including covariates for participant age (3rd-degree b-spline), sex, race/ethnicity, their interactions, and a series of indicator variables encoding year of data collection. Models included random intercepts to account for repeated observations of individuals. We used coefficient estimates for year-of-data-collection indicator variables to adjust biomarker values for period differences in biomarker distributions relative to the baseline reference year. Year-to-year variation in biomarker distributions was modest, but statistically different from zero in nearly all cases. Following adjustment, conditional distributions did not differ in their means. The figure graphs distributions of the original biomarker data in green and distributions of the period-effect-adjusted biomarker data in pink. Where distributions overlap, they appear as gray.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Changes in biomarker values over follow-up time.

Panel A in shows changes in biomarker values across baseline and four-and eight-year follow-up assessments among participants in the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS, N = 13,358). The HRS collected biomarker data from participants beginning either in 2006 or 2008. The figure combines data from these groups of participants; for example, the baseline (time-0) data include observations made in 2006 of one group and in 2008 of the other group. Y axis values are z-scores (M = 0, SD = 1) based on sex-specific distributions of values in participants aged <65. For gait speed, which was measured only in participants aged 65 and older, distributions were formed from participants aged 65–75. Biomarkers known to decline with aging were reverse coded so that higher values on the Y axis corresponds to ‘older’ levels of the biomarkers. Therefore, positive values for slopes of change indicate aging-related change in the direction expected. Panel B shows the parallel data for ELSA. Panel C shows comparison of biomarker slopes of change in HRS and ELSA. For this plot, biomarker slopes have not been reverse coded; biomarkers that decline with aging are shown as having negative slopes. The figure plots HRS slopes on the X axis and ELSA slopes on the Y axis. Slopes are highly correlated between datasets with the exception that Cystatin-C and hemoglobin have opposite directions of change with aging.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Correlations among slopes of biomarker change over time.

The figure shows correlations among slopes of biomarker change estimated from mixed-effects growth models in the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS) (Panel A) and the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA) (Panel B).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Correlations among baseline chronological age and biomarker slopes of change averaged within biomarker groups.

Panel A shows data for the US Health and Retirement Study. Panel B shows data for the English Longitudinal Study of Aging. The figure shows matrices of correlations and association plots among Pace of Aging and slopes of change averaged across blood biomarkers, physical assessments, and functional tests. The diagonal cells of the matrix list the measures. The half of the matrix below the diagonal shows scatter plots of associations. For each scatter-plot cell, the y axis corresponds to the variable named along the matrix diagonal to the right of the plot and the x axis corresponds to the variable named along the matrix diagonal above the plot. The half of the matrix above the diagonal lists Pearson correlations. For each correlation cell, the value reflects the correlation of the variables named along the matrix diagonal to the left of the cell and below the cell.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Differences in Pace of Aging among US Older Adults by Race and Ethnicity.

Figure shows data from non-Hispanic White (N = 9,150), Black (N = 2,204), and Hispanic (N = 1,630) -identifying older adults in the US Health and Retirement Study. Panel A shows the differences in distribution of Pace of Aging between White, Black, and Hispanic participants. Densities reflect distributions of Pace of Aging after adjustment for chronological age. White lines show group means. Panel B shows effect-size estimates for the differences in Pace of Aging relative to White participants. The figure illustrates overall faster pace of aging in Hispanic- and Black-identifying older adults as compared with White-identifying older adults.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Associations of Pace of Aging with mortality and incident chronic disease, disability, and cognitive impairment within demographic subgroups of HRS participants.

The figure graphs associations of Pace of Aging with mortality and incident chronic disease and disability estimated within demographic subgroups of HRS participants. Y axes show predicted mortality scores, counts of incident chronic diseases and ADL and IADL disabilities, and cognitive test scores. The X axis shows Pace of Aging. Slopes of predicted values are graphed separately for men and women (Panel A), White, Black, and Hispanic participants (Panel B), and older (aged >=65) and younger (aged <65) participants (Panel C).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Leave-one-out analysis comparing versions of the Pace of Aging measure excluding each biomarker in turn.

The figure shows comparisons of versions of the Pace of Aging measurement composed of different subsets of the biomarkers. Panel A shows correlations among different versions of the measure. Comparisons to the version of the measure including all biomarkers are shown in the first column/first row of the matrix. Panel B shows effect sizes for different versions of the measure. The red bars show the effect sizes for the original Pace of Aging (9 biomarkers). The other bars show the effect sizes for versions of the Pace of Aging composed of all possible subsets of 8 biomarkers. Panels C and D report parallel information for ELSA.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve analysis.

Panel A shows data for the sample with data on Pace of Aging and blood-chemistry measures of biological age (n = 7,537). Panel B shows data for the sample with data on Pace of Aging and epigenetic clocks (n = 2,848). ROC curves are generated by graphing sensitivity against 1-specificity for each value of a prediction metric. A predictor that generates no improvement in classification relative to random chance generates a diagonal line (sensitivity=1-specificty). ROC curves for predictors can be summarized by the area between the ROC curve and the diagonal, referred to as area under the curve (AUC). ROC Curves are drawn for model-based predictions of the outcomes including the aging measure indicated in the legend and a set of covariates (age, sex, race, education level, and smoking history). For reference, predictions from a model including only the covariates is also shown (‘base model’).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Balachandran, A., Pei, H., Shi, Y. et al. Pace of Aging analysis of healthspan and lifespan in older adults in the US and UK. Nat Aging 5, 1132–1142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00866-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00866-6

This article is cited by

-

Vitamin D and the aging skin: insights into oxidative stress, inflammation, and barrier function

Immunity & Ageing (2025)

-

A sex-adjusted 7-biomarker clinical aging clock for translational preventative medicine

Scientific Reports (2025)