Abstract

Background

RPE65-associated retinal degeneration (RPE65-RD) causes severe visual deficits. Gene therapy with AAV2-hRPE65v2 is a breakthrough but it is currently unknown which visual pathways benefit from treatment and if cortical mechanisms can amplify retinal improvements.

Methods

In this within-subject design, ten patients with biallelic RPE65-RD underwent sub-retinal injection of AAV2-hRPE65v2. Psychophysical full-field stimulus threshold determination and functional magnetic resonance imaging were performed before and 12 months after treatment. Population receptive fields (pRF) were computed in V1 and visual responses assessed using contrast-reversed checkerboards (3 contrast levels).

Results

Here we show significant improvement in light sensitivity at low-luminance and neural response enhancements under low-luminance conditions specifically in the right hemisphere, which is known to show dominance in attentional and visual pooling of spatial information. Changes in pRF size also reflect known hemispheric spatial asymmetries (left/right biased for local/global analysis, respectively).

Conclusions

Our findings show a contribution of known early and high-level cortical dominance mechanisms on improvement, which constrain the effects of therapy and are therefore a target for neurorehabilitation. These findings provide insight into the limits of clinical benefits of gene therapy and suggest that neurorehabilitation approaches may be needed to enhance improvements, similarly to cochlear implants.

Plain Language Summary

Retinal degeneration is caused by the loss of cells in the back of the eye and can lead to severe loss of vision. Here, we investigated the response of the brain to tests of vision in people who had been administered with gene therapy to treat retinal degeneration. Gene therapy is a treatment which aims to replace a gene that is not functioning correctly and thus causing disease. Ten patients were assessed before and a year after treatment using psychophysical tests and neuroimaging, and specific improvements in light sensitivity and neural responses were observed. The results suggest that rehabilitation approaches targeting the brain and vision may improve the results following this gene therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA) spectrum comprises LCA, severe early childhood-onset retinal degeneration (SECORD) and early childhood-onset retinal degeneration (ECORD). All three conditions are rare inherited retinal degenerations (IRD), characterized by genetic heterogeneity and severe visual impairment starting at birth or very early in life1,2,3. A characteristic neurophysiological finding in LCA is the electroretinographic observation of undetectable or significantly reduced retinal electrical responses to light stimuli4.

There is a notable temporal discrepancy in the pattern of degeneration of different photoreceptors. Rods are primarily affected early in the process, while cones degenerate late. This pattern is observed in various regions, including areas with a high density of photoreceptors, such as the macula5.

In recent years, several disease-causing variants in different LCA-associated genes have been identified. These findings enhance our understanding of disease processes and establishment of genotype-phenotype correlations. One of these genes, accounting for 5–10% of LCA cases, is RPE65. The RPE65 gene encodes a protein responsible for isomerohydrolase activity in the retinal pigment epithelium. The absence of this protein prevents the opsins of photoreceptors (cones and rods, responsible for photopic and scotopic vision, respectively) from effectively capturing light and performing the process of converting light into an electrical signal. This deficiency in phototransduction results in a significant deterioration of visual function6,7. Thus, biallelic disease-causing variants in RPE65 gene are usually associated with a severe phenotype, ranging from LCA to SECORD/ECORD2,3,4,8,9,10.

With the evolution of biotechnology, gene therapy (GT) is being increasingly used to enhance visual function in IRDs, both in animal models5,11 and in humans12. Consequently, in 2017, voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat RPE65-associated retinal degeneration (RPE65-RD)13. This treatment, also known as Luxturna®13, involves the subretinal delivery of the RPE65 gene using the serotype 2/2 adeno-associated vector (AAV2). Its aim is to slow down the degeneration of retinal cells and, as a result, restore some level of functional visual capacity in patients with a sufficient number of sufficient viable retinal cells4,14.

It is well documented in the literature that voretigene neparvovec provides substantial improvements in peripheral visual function, primarily by slowing the degeneration of rod cells, as evidenced by enhanced light sensitivity in low-light level conditions15. Voretigene neparvovec introduces a functional copy of the RPE65 gene, enabling the synthesis of a crucial enzyme in the retinal pigment epithelium cells involved in the retinoid visual cycle. Specifically, RPE65 is essential for the regeneration of 11-cis-retinal, which is required to reactivate rhodopsin in the rods after exposure to light16. Although both rods and cones rely on the retinoid cycle, cones possess an alternative pathway to regenerate the chromophore. As a result, the loss of RPE65 primarily affects the rods, as they depend exclusively on this cycle involving RPE65. Consequently, GT has a more direct impact on restoring rod function, specifically improving vision under low-light conditions (scotopic vision)16,17.

The study conducted by Mowat et al. 5 evidenced that in RPE65-deficient crossbred dogs, GT delays the moderate loss of rods and LM cones, simultaneously preventing the severe loss of S cones. However, it is worth highlighting that this intervention is restricted to the treated area and viable retinal cells5. The study by Jacobson et al. 12 in children and adult humans with RPE65-RD demonstrated that GT is safe and effective in the extrafoveal retinal region, albeit without evidence for benefits in the foveal region12.

Cones are essential for visual acuity, that is, the perception of spatial details. Thus, preserving the integrity of these photoreceptors would be an important asset of a therapeutic intervention for LCA5. However, the efficacy and the risk-benefit ratio of GT remains a matter of controversy regarding cone preservation and the consequent improvement of central and acuity vision, given that rods are the main substrate of improvement. Moreover, recovery of photoreceptors would in principal increase the spatial sampling of upstream visual pathways. However, there is a tradeoff between spatial pooling and acuity. The former is preferable under low light vision and the latter is preferable when spatial detail is needed. Such visual functions are subserved by distinct visual pathways (magno and parvocellular, respectively) and the effects of GT on the function of each pathway remain unclear14.

In the present study, functional testing and neuroimaging were used to investigate the cortical response to visual function restoration in 10 patients with RPE65-RD undergoing GT with voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna®). Our objective is to ascertain whether there is evidence for functional benefits in different processing channels in central and/or peripheral vision using both psychophysical and neuroimaging measures. Specifically, we asked the question whether the visual response induced by retinal therapy also relies on higher-level cortical mechanisms. Finally, our approach includes the analysis of retinotopic maps in this clinical group using the population receptive fields (pRFs) mapping technique for the first time.

Both early visual and high-level cortical mechanisms influence improvement, suggesting that neurorehabilitation targeting the latter may also influence the effects of therapy.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this prospective study, ten consecutive patients with RPE65-RD eligible for treatment with voretigene neparvovec were included. Patients were identified using the IRD-PT registry (retina.com.pt)18 and were preoperatively evaluated by a single IRD specialist (J.P.M.) from Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra (CHUC)—the only Portuguese Luxturna® treating center at the time of enrollment. Eligibility to undergo treatment depended on the presence of biallelic RPE65 disease-causing variants (i.e., class IV or class V variants according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics), along with the documentation of viable retinal cells on spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT). Patients were excluded from the study based on several criteria: the presence of monoallelic RPE65 mutations, class III mutations (i.e., variants of uncertain significance), central foveal thickness measured by OCT being less than 100 microns, absence of OCT evidence indicating viable retinal cells, BCVA less than 20/800, and/or inability to undergo functional testing. Before enrollment, every patient provided written informed consent following a comprehensive and detailed explanation of the research procedures. The study complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Coimbra.

Intervention

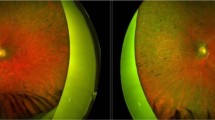

All participants were submitted to bilateral 25G pars plana vitrectomy followed by subretinal injection of 0.3 mL of AAV2-hRPE65v2. Each eye of every subject was operated by one of two senior vitreoretinal surgeons. As previously described by our group, the injection was performed in close proximity to the superior temporal vascular arcade (Fig. 1), at least 2 mm distal to the center of the fovea, according to the main guidelines, and the foveal region was detached in all treated eyes. To standardize the procedure as much as possible, the right eye was treated first, followed by the left eye. Treatment was administered one week apart for each eye. Perioperative oral corticosteroids were given to every patient19. There was foveal detachment in all cases, indicating that the injected therapeutic solution reached the subfoveal region.

a Representative image of subretinal injection in AAV2-hRPE65v2 gene therapy (Luxturna®) in the superotemporal region. b Visualization of the injection site in the macular area (superotemporal retina) in 6 eyes from our cohort (intraoperative, surgeon's view). The therapeutic solution bubble is delimited by the dashed yellow line. The location of this bubble cannot be fully predicted. As reference points, the fovea and the optic disc are depicted. Created with BioRender.

Psychophysical assessments

Full-field stimulus threshold (FST), best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and central visual field testing were performed at baseline (i.e., before treatment) and 12 months after the surgical administration of AAV-hRPE65v2.

For FST, we used the DiagnosysFST® module with the ColorFlash™ stimulator, which emits white light flashes to assess the sensitivity of photoreceptors to light. This examination was conducted by a certified technician under pupil dilation and dark adaptation20.

BCVA measurement was based on the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letter chart. It uses 14 lines of 5 Sloan letter optotypes arranged in a logarithmic progression, and the space between lines and letters is proportionally equal. Visual acuity can be directly determined from the chart. To minimize memory effects during repeated assessments, different letter combinations can be used for each eye. Chart testing distance is 4 m, but can be reduced when vision is severely impaired. The illuminated cabinet ETDRS ESV3000 automatically calibrates to a photopic light level of 85 cd/m².

Foveal sensitivity (FS) was assessed by computerized static perimetry using the 10-2 strategy of the Humphrey device (ZEISS Humphrey Field Analyzer 3, Germany).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) data were acquired at the same time-points (baseline and 12 months) using a 3 T scanner (Magneton Prisma Fit, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) from the Portuguese Brain Imaging Network, at ICNAS, University of Coimbra equipped with a 64-channel birdcage head/neck coil. The acquisition protocol included a high-resolution, 3D, T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition with gradient echo sequence was employed. It consisted of 176 slices with 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxel size, repetition time (TR) of 2.53 s, echo time (TE) of 3.5 ms, inter-slice time (TI) of 1.10 s, flip angle (FA) of 7°, and field of view (FOV) of 256 × 256 mm2. They underwent five fMRI acquisitions: three runs with a block design paradigm (right eye, RE; left eye, LE; and binocular, BIN), and two runs with a simultaneous bar stimulus. Single-shot T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging was utilized. Regarding the first stimulus, the parameters are as follows: 72 slices with 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 voxel size, a 100 × 100 image matrix, TR 1 s, TE 37 ms, FA 68°, and FOV 200 × 200 mm2. A total of 300 functional volumes were acquired in each functional run. However, the first fifteen scans were discarded. The second stimulus had the following parameters: 29 slices with 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 voxel size, a 128 × 128 image matrix, TR 2 s, TE 30 ms, FA 90°, and FOV 256 × 256 mm2. A total of 180 brain volumes of fMRI data were acquired. However, the first six scans were discarded.

Stimuli and experimental design

The visual stimuli were designed in MATLAB software (version R2023a, The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) and shown inside the MRI scanner bore using a 40-in. LCD screen (NNL LCD Monitor, NordicNeuroLab, Bergen, Norway). The display has dimensions 87.8 × 48.5 cm, a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels, a refresh rate of 60 Hz and is located ~179 cm away, creating a visual field of 27.56° × 15.43°. Participants viewed the screen through a mirror mounted above their eyes.

Block design paradigm stimulus

We employed a block design paradigm with a constant light intensity of 5 lux, presenting a 8 × 8 black-and-white checkerboard pattern with white squares flashing eight times per second (8 Hz). The size of the checks of the checkerboard in degrees is 3.54° × 1.94°. The luminance of the white squares varied at three different levels: 246.3 cd/m² (High, H); 87.46 cd/m² (Medium, M); and 22.8 cd/m² (Low, L). The luminance of the black squares was kept constant at 0.13 cd/m². The order of blocks with different luminances appeared randomly and varied between subjects. Based on the study by Ashtari et al. 2, this paradigm consisted of active checkerboard blocks interspersed with 15-s black screens as rest blocks2.

An fMRI run was conducted for each of the three conditions, binocular, RE, and LE. Each run consisted of 19 blocks, with 9 active blocks (3 blocks for each luminance level of the white squares) randomly interleaved with ten rest blocks. Each block had a duration of 15 s, as illustrated in Fig. 2a.

a Illustration of the checkerboard stimuli with three luminance levels in the white squares (high, H; medium, M; low, L). The paradigm consisted of 15 s active blocks of chessboards interspersed with a 15 s rest period (black screen) as control blocks. Each luminance level was presented three times, and the blocks of each luminance were randomly interspersed with ten rest blocks2. b Illustration of simultaneous visual stimuli with orthogonal bars. The arrows in the image indicate the direction of bar movement. For the initial 144 s, the horizontal bars moved downward while the vertical bars moved to the left. Following the isoluminant period, the horizontal and vertical bars traveled in the opposite direction21.

Each subject was instructed to fixate on the central cross, or, if unable to see it, to gaze at the center of the screen.

Simultaneous bar stimuli

The visual stimulus (total of 348 s) consisted of two flickering perpendicular bars continuously sweeping across the visual field. A horizontal bar moved vertically across the screen (18 steps, taking 36 s), while a vertical bar moved horizontally (24 steps, taking 48 seconds). Each bar position was displayed for 2 s. The bars featured a high-contrast colored flickering checkerboard pattern (flicker frequency is 20 hz), with the color of each square randomly flickering between RGB color values. A zero-contrast isoluminant period (167.2 cd/m2) was displayed for 30 s to allow pRF models to determine the baseline fMRI response amplitude. After this blank period, the bars moved in the opposite direction, concluding with a new isoluminant period (Fig. 2b)21.

Each subject was instructed to maintain fixation on the central crosshair on the screen and not to track the motion of the bars. Additionally, each subject completed the task twice in binocular mode.

During all the sessions, eye movement data were monitored using an MRI-compatible eyetracker (EyeLink) equipped with pupillography, albeit only online.

Data processing

The processing of anatomical and functional data, as well as retinotopic mapping, was conducted using BrainVoyager QX software (version 22.2, Brain Innovation B.V., Maastricht, the Netherlands).

To answer the main questions of this study we employed regions of interest (ROIs). The ROIs used in this study were the primary visual area (V1) of the right (RH) and left (LH) hemispheres. To analyze the stimulus with block design paradigm in volumetric space, both ROIs were segmented using a Probabilistic Functional Atlas of the Visual Cortex in MNI space (download.brainvoyager.com/data/visfAtlas.zip)22. Subsequently, we transformed this atlas into Talairach space through spatial conversion.

Anatomical data processing

In the anatomical images, the brain was extracted from extra-cerebral structures, the background was cleaned, and a bias field was estimated within white matter voxels to correct for intensity heterogeneities. Subsequently, the images were normalized to the Talairach reference system. Automatic segmentation was conducted for each cortex, and minor manual adjustments were applied for correction/improvement. 3D inflated mesh representations were created for each hemisphere.

Functional data preprocessing

In the functional images, preprocessing in the BrainVoyager software included correction for mean intensity adjustments, slice timing correction, head motion correction (with intra-session alignment for the pRFs data as there were 2 runs), and temporal filtering (high-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.0086 Hz). An anatomical co-registration to the Talairach space was performed, followed by spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel with a full width at half-maximum of 6 mm.

Retinotopic mapping

Through an analysis of Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) responses to the moving bar stimuli, we were able to characterize pRF associated with the neuronal response for each voxel. We followed a mapping approach first described by Dumoulin and Wandell which employs a Gaussian model to estimate the neural response model of the occipital lobe that best explains the fMRI response of each voxel concerning the positions of the visual stimulus field23.

BrainVoyager 22.2 was used to generate a sequence of 174 binary stimulus images with a resolution of 300 × 300 pixels squared to calculate the overlap proportion of the Gaussian pRF model with the binary stimulus over time, thereby determining the predicted neural response amplitude.

The Predicted Time Courses for the model were calculated using a grid of equally spaced 30x and 30 y points extending from -12 to 12 on the x-axis and from −7 to 7 on the y-axis, creating a visual field of 24° × 14°. A large set of pRF models was designed (each with a unique combination of position values, \(x\) and \(y\), and receptive field size) and each model was used to sample the binary stimulus frames. The predicted neuronal response is therefore determined by superimposing the stimulus with the Gaussian model. Each candidate neuronal response time course was convolved with the canonical BOLD hemodynamic response function to predict the BOLD response time course that the stimulus produces. The response predictions were fitted to the measured response of each voxel, and the pRF model parameters that minimized the residuals were chosen.

The pRF method provided six statistical maps related to the model-fitting procedure: R (square root of the explained variance), size (standard deviation), \(x\)-position, \(y\)-position, eccentricity, and polar angle for each hemisphere of each participant. These resulting maps in volume space were projected on 3D meshes.

In this study, the functional delineation of different visual areas in the 3D surface space from the polar angle map was challenging due to the retinotopic maps displaying considerably weaker signals. Consequently, our solution involved using pre-defined ROIs in the Functional Probabilistic Atlas of the Visual Cortex24.

To evaluate the pRFs size across the V1 region of each participant, the recording location was divided into twelve bins according to its eccentricity from 0° to 12° of visual angle, each spanning 1°. Using MATLAB R2023a script, the mean pRF size for central vision was extracted for each eccentricity (0.5–11.5°), bin for each hemisphere of each participant from the retinotopic maps, following the same methodology described in previous studies, which provides a standardized analysis25.

The explained variance (R²) was used as a quantitative measure of the model’s fit quality to the fMRI data. Therefore, only voxels with R² > 5% were included in the analysis of functional maps.

Participant RPE65-05 (Table S1) did not perform the block-design fMRI stimulus but did undergo retinotopic mapping.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the software packages BrainVoyager, SPSS Statistics 28.0.1.1 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and Prism 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, California).

After preprocessing, a block design analysis was performed using the General Linear Model (GLM) with fixed effects, to assess of differences between both sessions (pre- and post-GT) of active conditions (L, M, and H luminance levels of the white squares) versus the baseline condition. Thus, we conducted a first-level (within-subject) analysis and a second-level (group) analysis, which allowed to automatically calculate the values of cortical activation intensity (β) and the corresponding p-values.

Additionally, we investigated the changes in visual function as measured by FST, FS, and BCVA, by evaluating the difference in mean values of paired measurements before and after gene therapy. We also analyzed the relationship between psychophysical measures and brain activity in the V1 (fMRI) using Spearman’s bivariate correlations.

Our statistical analysis aimed to assess whether there was a significant difference in the changes of the mean pRFs size between the RH and LH after GT. To do this, the mean differences in pRF sizes between sessions (S2 versus S1) were calculated for each eccentricity in both hemispheres, and these means were compared between the RH and LH using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Bonferroni correction was used for post-hoc multiple comparisons testing. All statistical data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean or as the mean with a 95% confidence interval, as appropriate. All statistical tests were conducted as two-tailed tests with a significance threshold of 5%.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Psychophysical measures show improvement in peripheral sensitivity under dim light conditions but not in foveal vision

Ten patients (mean age ± SD = 27.0 ± 9.3 years; age range from 16 to 45 years, and 70% female) were included in the study. Clinical and demographic information is shown in Supplementary Material, Table S1. Visual function was assessed before and after 12 months of treatment using FST, BCVA (ETDRS letters), and FS. A detailed account of the results of these measures obtained during our study is presented as Supplementary Material, Table S1.

We observed significant improvements in participants following treatment with GT regarding their FST in both eyes (RE: \(N=10,{t}=2.884,{p}=0.018\); LE: \(N=10,{t}=2.768,{p}=0.022\)). Mean combined baseline and 12-month FST values were −2.35 ± 0.91 and −3.54 ± 1.09 log-units (Supplementary Material Fig. S1a).

However, we did not find significant improvements in BCVA (RE: \(N=10,{t}=1.842,{p}=0.099\); LE: \(N=10,{t}=1.705,{p}=0.122\)) or FS (RE: \(N=10,{t}=0.511,{p}=0.621\); LE: \(N=10,{t}=0.972,{p}=0.357\)). Both measures showed no significant differences before and after GT (Supplementary Material Fig. S1b and S1c).

Association between visual cortex activation and psychophysical measures

Correlation analysis was conducted between magnitude of activation changes in V1 (as assessed using β coefficients) for each of the three contrast levels and functional changes assessed by psychophysical and clinical evaluation, using patterned stimuli which known to be processed within acuity channels (L: \(N=9,\,\rho =0.833,{p}=0.005\); M: \(N=9,\,\rho =0.983,{p}\, < \,0.001\); H: \(N=9,\,\rho =0.883,{p}=0.02\); see Fig. 3), with no association found among the other variables (see Supplementary Material, Table S2).

The magnitude of the activation variation in the V1 visual cortex in response to a checkerboard pattern stimulus with a low luminance, b medium luminance, and (c) high luminance in the white squares, presented to both eyes, is correlated with the BCVA (N = 9). The neural response is an averaged combination of the left and right hemisphere responses under bilateral eye stimulation. BCVA is a combined measure of both eyes. The variation (Δ) is the percentage difference between measurements taken before and after 12 months of GT treatment.

In the correlation differences test conducted using the Meng’s test, it was observed that only BCVA significantly correlates with cortical activity, indicating that BCVA has a distinct relationship with cortical activity compared to the other variables. The correlation between BCVA and cortical activity is significantly different from the correlations with FST and FS \((p=0.00162)\). The correlations with FS \((p=0.154)\) and FST \((p=0.126)\) do not show significant differences from each other, suggesting that they have similar relationships with cortical activity.

Visual cortex activation

The GLM analysis showed a consistent trend towards improvement in low-luminance visual channels (Level L), as can be seen from the bar graph in Fig. 4. This improvement was specifically evident in the RH. Accordingly, it showed statistical significance when the low-luminance stimulus was exclusively presented to the treated temporal region in the RE corresponding to the RH (\(N=9,{t}=3.749,{p}\, < \,0.0001\)). Conversely, a decline in cortical response in V1 was evident for higher luminance levels, particularly in response to H-level luminance stimuli (shows a decline in brain activity with p < 0.001 for all conditions, with the notable exception of stimuli in the RE falling on the RH: \(N=9,{t}=-0.524,{p}=0.245\)). A similar pattern was observed for M-level luminance, with preservation of monocular functional responses only for stimuli falling on the RH (RE: \(N=9,{t}=-0.277,{p}=0.782\); LE: \(N=9,{t}=-1.061,{p}=0.288\)). In sum, for all luminance levels, we have identified an pattern: when stimulation falls on the RH and corresponds to the treated region (the case of RE), the cortical response in the corresponding RH either improves (for L-level luminance) or demonstrates resistance to decline (higher levels), suggesting that benefits are optimized in the RH, which dominates in spatial vision. The results of this statistical analysis are presented as Supplementary Material, Table S3.

BOLD signal in the V1 region percentage variation across the three luminance conditions of the stimulus: low-luminance (L Level); medium-luminance (M Level); and high-luminance (H Level). The variation in the BOLD signal was derived from the variation in the combined measure of the left hemisphere response during left eye stimulation and the right hemisphere response during right eye stimulation. This bar graph illustrates the mean and standard error between subjects for each luminance level, for N = 9. Additionally, individual data points for each luminance condition are plotted. In the M Level condition, two participants presented outlier values (not shown).

Additionally, we performed an analysis of pRFs within the V1 region in both cerebral hemispheres (Figs. 5, 6). Figure 6 shows that effects are nonlinear across eccentricity, which is consistent with a pattern generated by a focal injection. It is noteworthy that in the LH virtually all points show a decrease in pRFs size post GT, in contrast with the RH.

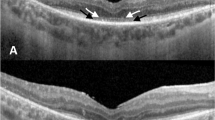

Representative maps obtained using the pRF technique: size, polar angle (PA) and eccentricity (ECC) maps of a participant before (1st visit) and after (2nd visit) gene therapy for both left (LH) and right (RH) hemispheres. The maps are presented in pseudocolor code: size, 0.00 (red) to 10.00 (light blue) degrees of visual angle; ECC, 0.00 (red) to 12.00 (dark blue) degrees of visual angle. The region of interest is the primary visual cortex (V1) and is represented in purple.

The results of the statistical test revealed statistically significant differences in the impact of therapy between hemispheres, with \(Z=-2.23,{p}=0.023\). As illustrated in Fig. 6, it is evident that the size of pRFs decreases in the LH with GT for virtually all eccentricities, in contrast with the RH, consistent with the notion that the latter is more involve in spatial pooling. Thus, voretigene neparvovec therapy demonstrates a distinct impact on the two hemispheres, indicating an asymmetric response in pRF characteristics. The RH has a higher value, suggesting that the PRF sizes in the RH are larger compared to those in the LH.

Discussion

In this study, we employed a combination of psychophysical measures, fMRI with contrast-reversing checkerboard block stimulation, and retinotopic mapping to investigate how GT with voretigene neparvovec influences visual function across distinct contrast channels and the role of visual cortex and hemispheric asymmetries.

As anticipated based on clinical trials10,26,27 and real-world28,29,30 data, light sensitivity under low luminance conditions, evaluated by FST, improved significantly for both treated eyes (Supplementary Table S1). However, this improvement was not observed in other psychophysical measures such as BCVA and FS, as there were no significant differences between the measurements before and after therapy. Our black-and-white checkerboard stimulus is a type of stimulus used for the objective assessment of macular function, as it provides well-defined contrasts31. The strong correlation between BCVA and fMRI data can be explained by the fact that both BCVA (a measure that directly depends on the function of the cones in the macula) and the brain responses are driven by the central visual pathways and the high spatial resolution of the visual system32. On the other hand, FST measures light sensitivity under low luminance conditions (primarily dependent on rod function), and as expected, does not show a strong correlation with fMRI responses to high-contrast stimuli10,33. Regarding FS, it is reasonable not to find a correlation with fMRI responses to high-contrast stimuli. FS measures the light sensitivity of the fovea rather than the perception of fine details34. In this way, the lack of correlation suggests that FS and fMRI high-contrast responses differ in visual processing.

Considering the fMRI data, we found improved sensitivity to low-luminance stimuli (L level), which are predominantly processed in the peripheral visual field. This finding aligns with the significant improvement in FST observed in both eyes. This strongly suggests that GT predominantly enhances visual perception in the perifoveal region rather than in the central pathways responsible for visual acuity.

Importantly, we found that when the visual stimulus falls on the RH and corresponds to the treated retinal region, the cortical response in the corresponding RH either improves (for low-luminance levels) or demonstrates resistance to decline (higher luminance levels) in contrast with the LH. These findings suggest the presence of a cortical amplification mechanism in the RH. The improvement observed in the RH after treatment may be related to functional lateralization, which is well described in the literature35,36. The RH, specialized in spatial vision, such as visual attention and global processing, appears more effective in optimizing the perception of low-luminance stimuli, potentially associated with increased activation of rod cells35,36. This result suggests that enhanced rod function may have amplified the RH’s spatial response. In contrast, the LH is more involved in fine detail discrimination, typical of high-acuity vision36.

When we focus on parameters such as visual acuity and responses to stimuli with medium and high luminance (M and H levels), which are more closely associated with central vision, and which we found to be correlated, the results indicate a notable absence of benefits conferred by GT. This observation is consistent with the existing literature4,12, reinforcing the notion that the impact of voretigene neparvovec is primarily on peripheral visual function and not on pattern vision.

Our investigations did not find equivalent cortical activation in response to fMRI stimuli following subretinal injections in both hemispheres. Manzar et al. 37 conducted a study in individuals with mutations in the RPE65 gene who had previously undergone GT in the eye with the poorest vision and received a second subretinal injection in the contralateral eye. Consistently with the notion that visual-spatial information processing in the two hemispheres of the brain is dependent on the feature characteristics of the stimulus38, we observed that cortical activations were predominantly observed in the RH. After therapeutic intervention, significant improvements were discerned in the RH when low-contrast stimuli were exclusively presented to the temporal region of the RE, which corresponds to that hemisphere.

Within the previous literature, this intriguing asymmetry in activation was previously explained as an artifact to the 2-year interval between injections, given that six out of seven participants initially received injections in the RE. Here we prove that this is not an artifact but instead a real effect. In our study, all patients received AAV2-hRPE65v2 injections in both eyes, in the superotemporal region of the retina, with a one-week interval between surgical procedures. It is pertinent to note that temporal retinal projections extend primarily to the ipsilateral hemisphere, with minimal crossing to the contralateral hemisphere. This suggests that injections in the RE could indeed have a more substantial impact on the RH. Nevertheless, the intriguing question arises: why did we not observe a similar effect in the left LH when the stimulus was solely presented to the LE? We propose a hypothesis rooted in the notion of a hemispheric asymmetry in spatial vision. High-level cognitive processes such as visual attention and spatial processing are known to be asymmetrically processed between hemispheres. Brain regions responsible for visual attention and global features predominantly reside within the RH in contrast with the LH in which local analysis dominates35,36.

In our study, for the first time in individuals with RPE65-RD, we conducted modeling of pRFs across the human visual cortex, specifically within the V1 region. Our findings revealed the above-mentioned differences in pRF size between the pre-and post-GT phases across the two hemispheres.

Under normal conditions, visual processing varies between hemispheres, with the LH being more sensitive to detecting local/specific stimulus features, and the RH to the global aspects of stimuli and spatial perception38. We demonstrate that GT with voretigene neparvovec distinctly influences the mean pRFs size in the two hemispheres. Interestingly, we found a significant decrease in pRFs in the LH. This effect is congruent with the role of this hemisphere in more detailed resolution analysis. Thus, it is plausible to suggest that the mechanism of visuospatial attention may serve as an enhancer of the visual process, rendering the RH more receptive to the effects of GT. This intriguing insight highlights the complex interplay between cognitive and retinal factors in modulating the response to therapeutic interventions, shedding new light on potential avenues for optimizing GT outcomes in the context of visual rehabilitation.

It is important to note that the outcomes we present here are primarily representative of the central visual field, specifically encompassing regions with an ECC of less than 12°. As anticipated, the pRFs properties align with our initial expectations that GT does not confer advantages to near-foveal vision.

Although we monitored eye movements online, we did not record the data. While this approach allowed for some level of control, the inclusion of concrete analysis of eye tracker data in future investigations could provide a more precise and objective assessment of fixation quality during the sessions10,33.Overall, our research provides further evidence for improved cortical function for low-luminance processing pathways, with a surprising hemispheric bias. Therefore, GT with voretigene neparvovec appears to facilitate improvements in scotopic vision, particularly due to the heightened receptivity of extrafoveal photoreceptors to the treatment. Nonetheless, our findings do not provide compelling evidence of any advantageous effects on acuity vision. Accordingly, the therapy does not improve local retinal function to the extent anticipated. In particular, the absence of improvement in BCVA and foveal sensitivity, can be interpreted as reflecting limited retinal restoration rather than cortical constraints.

The effectiveness of GT with voretigene neparvovec appears to be contingent upon various factors, including the site of the subretinal bubble after injection and high-level cortical processes. Notably, the visual cortex exhibits increased receptivity to treatment, particularly through mechanisms attributed to the RH, related to the analysis of low-luminance visual patterns (rod cell preference) and hemispheric asymmetries in visuospatial attention as well as in low-level processing39,40,41,42. The fact that the dominant hemisphere for spatial vision shows larger improvement suggests that GT should be coupled with cortical neurorehabilitation approaches to boost visual recovery.

In sum, we found differential therapeutic benefits for low-luminance visual processing channels, with a differential hemispheric cortical contribution to such improvements. Coupling gene therapy with cortical neurorehabilitation is therefore an important future intervention strategy.

References

Bennett, J. et al. AAV2 gene therapy readministration in three adults with congenital blindness. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 120ra15 (2012).

Ashtari, M. et al. The human visual cortex responds to gene therapy–mediated recovery of retinal function. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 2160 (2011).

den Hollander, A. I., Roepman, R., Koenekoop, R. K. & Cremers, F. P. M. Leber congenital amaurosis: genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 27, 391–419 (2008).

Le Meur, G. et al. Safety and long-term efficacy of AAV4 gene therapy in patients with RPE65 leber congenital amaurosis. Mol. Ther. 26, 256 (2018).

Mowat, F. M. et al. RPE65 gene therapy slows cone loss in Rpe65-deficient dogs. Gene Ther. 20, 545–555 (2012). 2013 20:5.

Sharif, W. & Sharif, Z. Leber’s congenital amaurosis and the role of gene therapy in congenital retinal disorders. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 10, 480 (2017).

Wang X., Yu C., Tzekov R. T., Zhu Y., Li W. The effect of human gene therapy for RPE65-associated Leber’s congenital amaurosis on visual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15,1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13023-020-1304-1/FIGURES/5 (2020).

Han, J. et al. Voretigene neparvovec for the treatment of RPE65-associated retinal dystrophy: consensus and recommendations from the Korea RPE65-IRD Consensus Paper Committee. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 37, 166 (2023).

Hufnagel, R. B., Ahmed, Z. M., Corrêa, Z. M. & Sisk, R. A. Gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis advances and future directions. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 250, 1117 (2012).

Russell, S. et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390, 849 (2017).

Acland, G. M. et al. Gene therapy restores vision in a canine model of childhood blindness. Nat. Genet. 28, 92–95 (2001).

Jacobson, S. G. et al. Gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis caused by RPE65 mutations: safety and efficacy in 15 children and adults followed up to 3 years. Arch. Ophthalmol. 130, 9–24 (2012).

FDA approves novel gene therapy to treat patients with a rare form of inherited vision loss | FDA 2017. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-gene-therapy-treat-patients-rare-form-inherited-vision-loss (accessed 29 Aug 2023).

Kang, C. & Scott, L. J. Voretigene neparvovec: a review in RPE65 mutation-associated inherited retinal dystrophy. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 24, 487–495 (2020).

Gange, W. S. et al. Perifoveal chorioretinal atrophy after subretinal voretigene Neparvovec-rzyl for RPE65-mediated leber congenital amaurosis. Ophthalmol. Retin. 6, 58–64 (2022).

Stingl K. et al. Therapy with voretigene neparvovec. How to measure success? Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101115 (2023).

Cai, X., Conley, S. M. & Naash, M. I. RPE65: role in the visual cycle, human retinal disease, and gene therapy. Ophthalmic Genet. 30, 57–62 (2009).

Marques J. P. et al. Design, development and deployment of a web-based interoperable registry for inherited retinal dystrophies in Portugal: the IRD-PT. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15, https://doi.org/10.1186/S13023-020-01591-6 (2020).

Marques, J. P., Alfaiate, M. & Figueira, J. P. Subretinal Bleb of Voretigene Neparvovec. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 11, 211, https://doi.org/10.1097/APO.0000000000000431 (2022).

DiagnosysFST ® Upgrade Module leading the wave 2021.

Miranda, Â. S. C. et al. Optical properties influence visual cortical functional resolution after cataract surgery and both dissociate from subjectively perceived quality of vision. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 986–994 (2018).

Rosenke, M., Van Hoof, R., Van Den Hurk, J., Grill-Spector, K. & Goebel, R. A probabilistic functional atlas of human occipito-temporal visual cortex. Cereb. Cortex 31, 603–619 (2021).

Silva, M. F. et al. Simultaneous changes in visual acuity, cortical population receptive field size, visual field map size, and retinal thickness in healthy human aging. Brain Struct. Funct. 226, 2839 (2021).

Amano, K., Wandell, B. A. & Dumoulin, S. O. Visual field maps, population receptive field sizes, and visual field coverage in the human MT+ complex. J. Neurophysiol. 102, 2704 (2009).

Pais M. L. et al. Rapid effects of tryptamine psychedelics on perceptual distortions and early visual cortical population receptive fields. Neuroimage 297 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2024.120718 (2024).

Maguire, A. M. et al. Durability of voretigene neparvovec for biallelic RPE65-mediated inherited retinal disease: phase 3 results at 3 and 4 years. Ophthalmology 128, 1460–1468 (2021).

Maguire, A. M. et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of voretigene neparvovec-rzyl in RPE65 mutation-associated inherited retinal dystrophy: results of phase 1 and 3 trials. Ophthalmology 126, 1273–1285 (2019).

Stingl, K. et al. Full-field scotopic threshold improvement after voretigene neparvovec-rzyl treatment correlates with chorioretinal atrophy. Ophthalmology 130, 764–770 (2023).

Gao, J., Hussain, R. M. & Weng, C. Y. Voretigene neparvovec in retinal diseases: a review of the current clinical evidence. Clin. Ophthalmol. 14, 3855–3869 (2020).

Deng, C. et al. Real-world outcomes of voretigene neparvovec treatment in pediatric patients with RPE65-associated Leber congenital amaurosis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 260, 1543–1550 (2022).

Holder, G. E. Pattern electroretinography (PERG) and an integrated approach to visual pathway diagnosis. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 20, 531–561 (2001).

Kwak, J. J., Kim, H. R. & Byeon, S. H. Short-term outcomes of the first in vivo gene therapy for RPE65-mediated retinitis pigmentosa. Yonsei Med. J. 63, 701 (2022).

Shi, L. F., Hall, A. J. & Thompson, D. A. Full-field stimulus threshold testing: a scoping review of current practice. Eye 38, 33–53 (2023).

Chiba, N., Imasawa, M., Goto, T., Imai, M. & Iijima, H. Foveal sensitivity and visual acuity in macular thickening disorders. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 56, 375–379 (2012).

Whitehead, R. Right hemisphere processing superiority during sustained visual attention. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 3, 329–334 (1991).

Hellige, J. B. Hemispheric asymmetry for visual information processing. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 56, 485–497 (1996).

Ashtari, M. et al. The role of the human visual cortex in assessment of the long-term durability of retinal gene therapy in follow-on RPE65 clinical trial patients. Ophthalmology 124, 873 (2017).

Hugdahl, K. Visual-spatial information processing in the two hemispheres of the brain is dependent on the feature characteristics of the stimulus. Front. Neurosci. 7, 40344 (2013).

Silva, M. F., d’Almeida, O. C., Oliveiros, B., Mateus, C. & Castelo-Branco, M. Development and aging of visual hemifield asymmetries in contrast sensitivity. J. Vis. 14, 19 (2014).

Sampaio, J. et al. Specific impairment of visual-spatial covert attention mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia 49, 34–42 (2011).

Silva, M. F. et al. Asymmetry of visual sensory mechanisms: electrophysiological, structural, and psychophysical evidences. J. Vis. 10, 26 (2010).

Silva, M. F. et al. Retinal and cortical patterns of spatial anisotropy in contrast sensitivity tasks. Vis. Res. 48, 127–135 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by FCT/UIDB&P/4950/2020/2025, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04950/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04950/2020 and 2022.02963.PTDC, https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.02963.PTDC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mariana Ferreira: Conceptualization, Data Acquisition, Data Processing and Analysis, Manuscript Draft, Draft Review; João Pedro Marques: Conceptualization, Data Acquisition, Draft Review; Miguel Raimundo: Conceptualization, Data Acquisition, Draft Review; Hugo Quental: Data Acquisition, Draft Review; Miguel Castelo-Branco: Conceptualization, Funding, Supervision, Draft Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, M., Marques, J.P., Raimundo, M. et al. Improvements induced by retinal gene therapy with voretigene neparvovec depend on visual cortical hemispheric dominance mechanisms. Commun Med 5, 107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00820-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00820-y