Abstract

Background

The necessity of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for ending the global AIDS epidemic by 2030 remains controversial. In Taiwan, the HIV epidemic predominantly affects young, sexually active men who have sex with men (MSM). This study aimed to model the impact and cost-effectiveness of a high-coverage oral emtricitabine/tenofovir PrEP program in Taiwan from an HIV elimination perspective.

Methods

We applied stochastic and risk/age-structured deterministic modeling to assess the impact of PrEP scale-up on the basic reproduction number (R0) and the trajectory of the HIV epidemic in Taiwan, respectively. Both models were parameterized using the national HIV registry and cascade data. Cost-effectiveness was evaluated from a societal perspective.

Results

Here we show that an intensive HIV test-and-treat strategy targeting HIV-positive individuals alone would substantially decrease HIV transmission but is not sufficient to eliminate the HIV epidemic among MSM at the estimated mixing level. In contrast, a PrEP program covering 50% of young, sexually active, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM would suppress HIV’s R0 below 1, facilitating its elimination. It would also reduce HIV incidence to levels below the World Health Organization’s HIV elimination threshold (1/1000 person-years) by 2030 and is highly cost-saving, yielding a benefit-cost ratio of 7.16. The program’s effectiveness and cost-effectiveness remain robust even under conditions of risk compensation (i.e., no condom use among PrEP users), imperfect adherence (75%), or low-level emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance (1%).

Conclusion

Our findings strongly support scaling up PrEP for young, sexually active, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM as a critical strategy to end the HIV epidemic in Taiwan and globally.

Plain language summary

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) involves taking antiviral medication before potential exposure to HIV during unsafe sex to prevent passing on the disease. The high cost of PrEP and concerns about encouraging risk-taking have limited its use. To assess the impact of broadly providing PrEP to help end the global AIDS epidemic, we utilized advanced mathematical models to simulate the HIV epidemic in Taiwan. We found that relying solely on early diagnosis and treatment is insufficient to halt the epidemic. However, offering PrEP to half of the high-risk youth could eliminate HIV by 2030 and would be highly cost-saving for society. Our findings underscore the importance and feasibility of making PrEP accessible to those at high risk to end the HIV epidemic in Taiwan and globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two randomized trials, the PROUD study and the IPERGAY study, have demonstrated that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with oral emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada™) is highly effective when taken either daily or on demand, preventing up to 86% of HIV acquisitions among high-risk, HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM)1,2. An open-label extension of the IPERGAY study indicates that, with optimal adherence, the efficacy of on-demand PrEP can reach 97%3. Rapid, targeted, high-coverage rollout of PrEP was associated with a rapid decline in new HIV diagnoses in New South Wales, Australia4. Modeling studies have suggested that HIV elimination might be possible in the Netherlands and the Paris region when PrEP coverage rates increase to 82% and 55%, respectively5,6.

Despite these promising study findings, PrEP remains expensive and underutilized globally7,8. Financial constraints represent an important barrier7,8,9, along with additional concerns: risk compensation—defined as increased risk-taking behaviors due to perceived reductions in HIV risk from PrEP usage10,11,12—non-adherence13,14, and drug resistance15,16. These barriers have impeded the PrEP rollout17,18. To date, the necessity of PrEP for achieving the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) goal of ending the global AIDS epidemic by 203019,20,21 remains controversial22,23,24,25,26,27, and the cost-effectiveness of implementing a high-coverage PrEP program for HIV elimination has not yet been evaluated.

In Taiwan, despite universal access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) since 1997, which led to a 53% decrease in HIV transmission28, the rise in recreational drug use during the 2000s fueled a new wave of the HIV epidemic, predominantly affecting young, sexually active MSM, with more than 2000 new HIV diagnoses annually from 2012 to 201729,30. The Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has implemented the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on initiating ART immediately after an HIV diagnosis since 201531 and has expanded HIV testing services32, aiming to achieve the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal33 of reducing HIV transmission through early HIV diagnosis and early initiation of ART22,34. The proportion of diagnosed patients on ART in Taiwan improved from 67% in 2014 to 88% in 201835,36. The number of new HIV diagnoses decreased to 1991 in 2018 and 1755 in 2019, respectively30. In 2020, Taiwan achieved the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets, with 90% of people living with HIV knowing their status, 93% of diagnosed patients receiving ART, and 95% of treated patients achieving an undetectable viral load37. Nevertheless, a persistent high (30%–40%) proportion of new HIV patients were not diagnosed until the late stage from 2018 onward36. Furthermore, during the period from 2020 through 2022, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to a sudden drop of 30% to 40% in HIV testing in Taiwan. Additional strategies that are less affected by the persistently high rate of late HIV diagnosis and more resilient to pandemic disruptions are needed.

Cost has been a major barrier to accessing PrEP in Taiwan since the 2016–2017 PrEP pilot project, particularly for young MSM who are at the highest risk for HIV38. The 2018–2019 PrEP demonstration project, which included ~1000 MSM participants, was supported by a donation from Gilead Sciences Inc (Foster City, CA, USA). To date, public funding for PrEP in Taiwan remains very limited, covering only 20 tablets of Truvada™ per person every 3 months for MSM39.

In this study, we model the impact and cost-effectiveness of a high-coverage PrEP program serving young, high-risk MSM in Taiwan from an HIV elimination perspective. We employ both stochastic and risk/age-structured deterministic models, precisely parameterized using the national HIV registry, HIV cascade, mortality, and vital statistics data in Taiwan, to assess the effect of scaling up PrEP on the basic reproduction number (R0) of HIV and the trajectory of the HIV epidemic in Taiwan, respectively. We find that an intensive HIV test-and-treat strategy targeting HIV-positive individuals alone would substantially decrease HIV transmission but is not sufficient to eliminate the HIV epidemic among MSM at the estimated mixing level. In contrast, a PrEP program serving young, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM with 50% coverage would suppress the R0 of HIV to below 1, facilitating its elimination. This program would also reduce the incidence of HIV infection to levels below the WHO’s HIV elimination threshold (1/1000 person-years) by 2030 and is highly cost saving for society, yielding a benefit-cost ratio of 7.16. The PrEP program’s effectiveness and cost-effectiveness remain robust even under conditions of risk compensation (i.e., no condom use among PrEP users), imperfect adherence (75%), or low-level emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance (1%). Our findings strongly support the importance and feasibility of making PrEP accessible to young, sexually active, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM as a critical strategy to end the HIV epidemic in Taiwan and globally.

Methods

Study design

We employed both deterministic and stochastic models to evaluate the impact of a high-coverage oral emtricitabine/tenofovir PrEP program on the HIV epidemic among MSM. In Taiwan, sexually transmitted HIV infection and hepatitis A among MSM occur as a single, synchronous epidemic29,40, rather than as multiple micro-epidemics across cities. This phenomenon is likely attributable to the intense mixing between MSM communities from different cities, facilitated by high-speed transportation networks that interconnect metropolitan areas into a unified megalopolis. We first constructed a deterministic model based on the natural history and transmissibility of HIV infection, as well as the effectiveness of ART. We fitted the model to the national HIV registry data30,41 from 1990 to 2019 and to HIV cascade data for MSM cases35, provided by the Taiwan CDC (Taipei, Taiwan). We then projected the impact of PrEP on the trajectory of HIV incidence from 2020 to 2050 in Taiwan, as well as its cost-effectiveness, assuming that the COVID-19 pandemic had not occurred. Additionally, we applied a corresponding stochastic model to assess the impact of PrEP on the R0 of HIV. The WHO emphasizes that to reduce HIV incidence and eventually eliminate the HIV epidemic, the R0—the number of secondary infections resulting from one primary infection in an entirely susceptible population—must be reduced to and maintained below 122.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan) (#201501029RIND, #201601067RINA, and #201703099RINA). The committee granted a waiver of informed consent from patients, as this modeling study did not involve the use of identifiable personal information.

Structure of deterministic model

We constructed a risk-structured (high-risk and low-risk group), age-structured (15–44 years, 45–64 years, and ≥65 years) compartmental model with assortative mixing (Supplementary Fig. 1). The high-risk groups consist of MSM at risk of acquiring HIV from unsafe sexual practices with multiple, random sexual partners. Each risk/age stratum was subdivided into 37 mutually exclusive compartments, based on the stage of natural history, HIV test-and-treat status, and PrEP status (Fig. 1). The model considers the natural history of HIV infection across age strata42,43 (Supplementary Fig. 2) and the substantially higher infectiousness observed during the acute HIV infection and the AIDS stage44 (Supplementary Fig. 3). It also considers the impact of ART in reducing HIV transmission and HIV-related mortality34,45. Furthermore, we assume that behavioral changes following HIV diagnosis and linkage to care are associated with a reduction in HIV transmissions22,46.

This model stratifies the population based on risk (high-risk and low-risk groups), and age (15–44 years, 45–64 years, and >65 years), with assortative mixing (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Each risk and age stratum is further divided into 37 compartments, as illustrated, comprising: Susceptible (S); Infectious, undiagnosed (I1–I7); Tested and diagnosed (not linked to care) (T1–T7); linked to Care (awaiting antiretroviral treatment) (C1–C7); receiving Antiretroviral therapy (A1–A7); and Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (uninfected: P0; infectious but undiagnosed: P1–P7). The subscripts indicate the stages of HIV infection: 1, acute HIV infection in the window period; 2, acute HIV infection, detectable; 3–5, chronic HIV infection with CD4 cell counts >500 cells/mm3, 350–500 cells/mm3, and 200–350 cells/mm3, respectively; 6, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), CD4 cell count <200 cells/mm3 but without any opportunistic infections; 7, AIDS, CD4 cell count <200 cells/mm3, opportunistic infections have occurred. Parameters for the natural history of HIV infection, \({\rho }_{\kappa },\) represent the rates of HIV disease progression from stage κ to stage κ + 1 in HIV-positive individuals not receiving antiretroviral therapy. Parameters for HIV test-and-treat include \({\tau }_{\kappa },\) the rate of HIV testing, \({\sigma }_{\kappa },\) the rate of linkage to care following diagnosis, and \({\gamma }_{\kappa },\) the rate of initiating antiretroviral therapy after linkage to care, for individuals at HIV stage κ. The parameter \({{\Phi }}\) represents the PrEP coverage proportion among high-risk men who have sex with men (MSM) aged 15–44 years. The parameter \(\omega\) represents the relative risk of HIV acquisition for HIV-negative MSM receiving PrEP compared to those not receiving PrEP. MSM receiving PrEP are subjected to regular HIV testing every 3 months (\({\tau }_{{{{\rm{P}}}}2-{{{\rm{P}}}}6}\)), denoted by dashed lines. The model also considers mortality rates for individuals without HIV (μ) and mortality rates for those living with HIV (η) in corresponding compartments, as indicated by arrows. Model parameters, their values, and data reference are listed in Supplementary Data 1 and detailed in Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Parameterization: deterministic model

Model parameters, their values, and data references are listed in Supplementary Data 1 and detailed in Supplementary Tables 1–8. We estimated the effectiveness of ART in decreasing HIV transmission and HIV-related mortality based on the HPTN 052 study34, the START study45, and large treatment cohort studies47,48,49,50,51 (refer to Supplementary Data 1 for details). We estimated the efficacy of PrEP in preventing HIV transmission based on the IPERGAY study and the PROUD study1,2. We estimated the total at-risk MSM population using Taiwan population statistics52 and the assumption that 3% of the male population in Taiwan are MSM53,54,55. Annual numbers of new MSM HIV diagnoses are based on the national HIV registry data30,41. We estimated the transmission coefficients, the effective population size of the high-risk group among MSM, and the theoretical initial year when the first HIV infection occurred in Taiwan, by fitting the model to the actual MSM HIV epidemic curve in Taiwan from 1990 to 2019 by age strata using the least squares method (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The ratios between transmission coefficients within and between high- and low-risk groups in the risk-structured model were set based on data from the EXPLORE study56. We estimated the rates of HIV testing among MSM by fitting the model to the percentages of late HIV diagnoses (≤30 days before AIDS diagnosis)41 among new MSM cases by age strata in the Taiwan HIV registry30,41 (Supplementary Fig. 5). We estimated the rates of linkage to care and initiation of ART for MSM living with HIV based on the mean duration from diagnosis to the first medical visit and on the proportions of patients starting ART, both provided by the Taiwan CDC.

The numbers of notified MSM HIV diagnoses (presented as bars) are based on data from the Taiwan national HIV registry (see Statistics and Reproducibility section). We fitted the deterministic model to the actual Taiwan HIV epidemic curve from 1990 to 2019 by age strata, using the least square method (presented as lines). To account for the trend of changing sexual behaviors over time, the model fitting was separately conducted for each era during which parameters may have increased or decreased linearly: 1990–1997 (before ART), 1997–2001 (introduction of ART), 2001–2005 (impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in Taiwan), 2005–2009 (rise of internet chat room for sexual partner-seeking), 2009–2013 (rise of mobile phone apps for sexual partner-seeking), 2013–2017 (chemsex-associated increase in HIV transmission), and 2017–2019 (status quo), respectively. Refer to “Methods”, Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Tables 1–8, and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 for details on model fitting and parameterization.

Structure of stochastic model

We constructed a stochastic model that simulates the life course of a young MSM with high-risk sexual behavior, who acquires HIV on his 20th birthday, up to the age of 45. The natural history of HIV, the substantially higher infectiousness during the acute HIV infection and AIDS stages, the HIV test-and-treat process, the effect of ART on transmission and mortality, and the effect of PrEP in preventing HIV infection mirror those aspects in the deterministic model. Each day, the index patient may engage in oral or anal sex with other high-risk, HIV-negative MSM (on PrEP or not), undergo HIV testing (which is followed by linkage to care and the subsequent initiation of ART), or die (Supplementary Fig. 6). We further consider 35 different scenarios in which HIV testing, linkage to care, and initiation of ART either occur or do not occur at various HIV stages (Supplementary Fig. 7). We estimated R0 as the mean number of HIV transmissions that would occur over the life course in an entirely susceptible high-risk MSM population in 1000 simulations.

Model parameterization: stochastic model

Model parameters, their values, and data references are listed in Supplementary Data 2. The natural history of disease progression from HIV infection to AIDS (CD4 < 200 cells/mm3) was stochastically simulated starting from an initial CD4 count value of 1000 cells/mm3 (with a standard error [SE] of 20 cells/mm3, assuming a normal distribution), based on Granich et al. 22, with a monthly stochastic decrease based on the rate of CD4 decline and their SE as reported by Longini et al. (refer to Table 3 in ref. 42). We assigned fixed durations of 30 days for the window period (I1), 60 days for the detectable acute HIV infection stage (I2), 1.6 years for AIDS without opportunistic infections (OIs) (I6), and 1 year before death for AIDS with OIs (I7), based on Longini et al. 42 (Supplementary Fig. 2). We assume that the initiation of ART halts the progression of HIV disease. We set the level of sexual mixing among high-risk MSM aged 15–44 years at 50 sexual partners per year, an estimate based on the fitting results of the deterministic model (see Supplementary Data 2, footnote a). The probabilities of oral versus anal sex per encounter are based on Chen et al. 46 and Chiu et al. 57 The per-act probability of HIV transmission for anal sex (assuming an equal probability of insertive and receptive anal intercourse) and for oral sex is based on Patel et al. 58 and Vittinghoff et al. 59, respectively.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

We modeled the effect of a high-coverage oral emtricitabine/tenofovir PrEP program serving young, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM (aged 15–44 years, at risk of acquiring HIV from unsafe sexual practices with multiple random partners). The PrEP program requires initial HIV testing upon entry and subsequent HIV testing every 3 months60. To model the coverage rate, individual users continue to enter or re-enter the PrEP program, stay for a period, and then drop out, maintaining the coverage rate at the specified level in both the stochastic model and the deterministic model. To model risk compensation, we reduce the condom use rate among PrEP users from the baseline (30%)46,57 to 0% in the stochastic model. This reduction corresponds to an increase in the transmission coefficients involving PrEP users by a factor of (100%\(-\)0%)/(100%\(-\)30%) in the deterministic model. To model PrEP compliance, the model assumes that 100% adherence corresponds to a 97%3 efficacy in both models, with 75% adherence translating to an efficacy of 97% \(\times \,\)75%. To model 1% emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance, the population-level efficacy of PrEP in the deterministic model decreases to 86% \(\times\) (100%\(-\)1%); while in the stochastic model, the individual-level efficacy of PrEP decreases from 86% to 0% in 1% (100 out of 10,000) of the simulations.

HIV test-and-treat

The WHO recommends annual testing for key populations, including MSM60. We modeled the effect of the WHO’s annual HIV testing and immediate initiation of ART strategy22,31 among young, high-risk MSM. We consider individuals taking ART and achieving viral load suppression as non-transmissible (undetectable equals untransmittable, U = U)61. Under the Taiwan CDC’s HIV case management system, 95% of treated patients achieve an undetectable viral load37. Both the deterministic model and the stochastic model assume that, while individual patients may experience fluctuations in viral load suppression, the population of people on ART in Taiwan as a whole achieves and maintains viral load suppression at levels similar to those of participants receiving ART in the HPTN 052 study, with a 96% decrease in transmissibility34.

Main outcomes

The main outcomes are HIV elimination and its cost-effectiveness. The threshold for HIV elimination is set as an R0 of HIV less than 1 in the stochastic model or an annual incidence of HIV infection of less than 1 per 1000 susceptible person-years in the deterministic model, as defined by the WHO22. The economic analysis compares scenarios with or without a PrEP program, projected into the future using the deterministic model.

Cost structure for PrEP and HIV medical care

The cost structure of the PrEP program includes costs for PrEP drugs, counseling, regular testing for HIV, syphilis, and other sexually transmitted infections, as well as biochemical monitoring for adverse effects (Supplementary Fig. 8)62,63,64,65,66,67. On-demand use of PrEP requires 15 tablets of TruvadaTM per month2. The cost for each item was based on the reimbursement guidelines for medical services of the Taiwan National Health Insurance (Supplementary Table 9). The cost structure of HIV-associated medical care encompasses cost for ART, regular testing for CD4 count and HIV viral load, biochemical follow-ups, case management, and treatment for OIs, stratified by the presence of AIDS at diagnosis (Supplementary Fig. 9). The cost for each item was based on real-world data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance database, with costs for ART and OIs treatment representing the average cost per patient (Supplementary Table 10).

Projected lifetime survival curve and loss of quality-adjusted life expectancy (QALE) for Taiwanese MSM living with HIV

The projected lifetime survival curves—mean survival time: 41.3 years after HIV diagnosis without AIDS and 29.7 years after HIV diagnosis with AIDS (illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 10)—for Taiwanese MSM living with HIV were based on our pioneering work41,68. Additionally, the loss of QALE for each Taiwanese MSM with a new HIV diagnosis (5.44 quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs] for each new diagnosis without AIDS and 13.95 QALYs for each new diagnosis with AIDS) is also based on our pioneering work41,68, in which we empirically measured the quality of life among Taiwanese MSM living with HIV using the EuroQol-5D health utility instrument, and integrated this with projected lifetime survival to estimate QALE after HIV diagnosis and loss-of-QALE relative to the general population (illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 11).

Economic analysis

We adopt a societal perspective over a 20-year time horizon (2021–2040). All future costs, including those related to PrEP and HIV treatment, are adjusted by a 3% annual discount rate to their 2021 value. We estimated the lifetime HIV-associated medical costs under Taiwan’s National Health Insurance by integrating projected lifetime survival curves (Supplementary Fig. 10) with the mean HIV treatment cost per patient (Supplementary Table 10)69. We calculate the societal human capital saved by averting new HIV diagnoses by multiplying the total number of QALYs gained, under the intervention scenario, by Taiwan’s per capita gross domestic product of USD 25,157 in 2018 (at 30 NTD to 1 USD)70, in line with the WHO’s recommended threshold for cost-effectiveness of interventions71. For cost-saving interventions, we further calculate the benefit-cost ratio by dividing the sum of the saved HIV-associated medical costs and averted human capital loss by the cost of the intervention.

Statistics and reproducibility

Numbers of notified MSM HIV cases

In the national HIV registry, all registered HIV cases were categorized into eight mutually exclusive risk groups of HIV transmission: “homosexual behavior”, “bisexual behavior”, “(exclusively) heterosexual behavior”, “injecting drug use”, “mother-to-child transmission”, “hemophilia”, “blood transfusion”, and “undisclosed”41. The categorization of sexual behavior was based on self-reporting from patients. MSM who chose not to disclose their same-sex encounters were registered as “undisclosed” or “(exclusively) heterosexual”. To account for the under-disclosure of MSM in the HIV registry, we estimated the number of new MSM HIV cases by summing the number of male HIV cases whose risk groups of HIV transmission were categorized as “homosexual”, “bisexual”, “undisclosed”, and “heterosexual” and then subtracting the number of heterosexual female cases. This approach assumes that the true number of exclusively heterosexual male cases equals the number of heterosexual female cases.

Least squares method

We used the mean square error (MSE) between real-world and model-predicted new MSM HIV diagnosis in each year across all three age strata (j = 1 for 15–44 years, j = 2 for 45–64 years, and j = 3 for ≥65 years) as the goodness-of-fit statistic to determine the best-fit model: MSE = \(\frac{1}{n}{\sum}_{j=1}^{3}{\sum}_{i=1}^{n}{({Y}_{{ij}}-{\hat{{{{\rm{Y}}}}}}_{{ij}})}^{2}\), where n is the number of years used in model fitting; \({Y}_{{ij}}\) and \({\hat{{{{\rm{Y}}}}}}_{{ij}}\) represent the number of real-world and model-predicted HIV cases for the ith year in the age stratum j, respectively.

Model documentation

The development, testing, and analysis of the deterministic model, stochastic model, and economic analysis are fully documented in TRACE checklists72 in Supplementary Notes 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The differential equations for deterministic modeling and the R scripts for stochastic modeling are provided in Supplementary Notes 4 and 5, respectively.

Replication

We estimated R0 as the mean number of HIV transmissions that would occur over the life course in an entirely susceptible high-risk MSM population, based on either 1000 simulations or 10,000 simulations when modeling the effect of emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted one-way sensitivity analyses for HIV elimination in both the stochastic and deterministic models, as well as for the benefit-cost ratio in the economic analysis, by varying parameters with uncertainty. These parameters include the targeted PrEP coverage rate, risk compensation, PrEP adherence, and emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance. Additional parameters examined in the sensitivity analysis include the level of sexual mixing, relative infectiousness between acute and chronic stages in the stochastic model; the year of PrEP rollout, entry HIV testing during PrEP rollout, and an increase in the proportion of young MSM entering the high-risk group upon reaching 15 years of age in the deterministic model; and costs for PrEP drugs (brand-name TruvadaTM vs. generic drugs) and ART drugs (the cheapest first-line regimens vs. the most expensive second-line regimens), the year of PrEP rollout, and the time horizon in the economic analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Necessity of a high-coverage PrEP program for HIV elimination

Our stochastic modeling shows that, under the estimated mixing level (50 partners/year, see Supplementary Data 2, footnote a), in the absence of PrEP, an intensive HIV test-and-treat campaign with annual HIV testing followed by immediate ART would substantially decrease the R0 of HIV but would not suffice to suppress it to below 1 (Table 1; Supplementary Data 3A). In contrast, a 50% coverage-rate PrEP program serving young, high-risk MSM would suppress the R0 of HIV to below 1, even if the HIV test-and-treat status remains unchanged. Table 1 further reveals that the HIV test-and-treat strategy has only a minimal impact on the number of HIV transmissions that occur during the acute HIV infection stage (highlighted with parentheses). Conversely, a 50% coverage PrEP program reduces the HIV transmissions during the acute infection stage by half. Thus, PrEP could be instrumental in eliminating HIV among MSM in Taiwan.

Effect of risk compensation on the impact of a PrEP program

We modeled the effect of risk compensation, defined as a decrease in the condom use rate from the status quo (30%) to 0% among all high-risk MSM who take PrEP in the program. Supplementary Data 3B shows that, contrary to popular concern, risk compensation does not have a noticeable effect on the impact of a PrEP program, as evidenced by the comparison between Supplementary Data 3A and 3B.

Effect of emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance on the impact of a PrEP program

We modeled the effect of 1% emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance, where the efficacy of PrEP drops to zero during an encounter with an individual with an emtricitabine/tenofovir-resistant HIV strain. Supplementary Data 3C shows that an emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance level of 1% does not have a noticeable effect on the impact of a PrEP program, as evidenced by the comparison between Supplementary Data 3A and 3C.

Effect of non-adherence on the impact of a PrEP program

We then modeled the effect of non-adherence to taking PrEP, assuming that 100% adherence corresponds to an efficacy of 97%. Supplementary Data 3D shows that, under the estimated mixing level of 50 sexual partners per year and the status quo for HIV test-and-treat, at least 75% adherence is required for a PrEP program with a 50% coverage rate to suppress the R0 of HIV to less than 1. Figure 3 further illustrates the isolines for R0, demonstrating the trade-off between adherence and coverage rate in the high-risk MSM population.

Sensitivity analyses on HIV elimination under stochastic modeling

We further investigated the influence of parameters with uncertainty on HIV elimination. Table 2 and Supplementary Data 3E show that without PrEP, annual HIV testing and immediate ART could eliminate HIV only in favorable scenarios with a mixing level as low as 25 sexual partners per year or acute-stage infectiousness of only 3 to 10-fold over the chronic stage. In contrast, under the status quo HIV test-and-treat, a 50% coverage PrEP program serving young, high-risk MSM would decrease the R0 of HIV to below 1, even under unfavorable scenarios with a mixing level of up to 75 sexual partners per year, acute-stage infectiousness up to 30 times higher than that in the chronic stage, or an emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance rate of up to 10% (Table 2 and Supplementary Data 3F).

Under the status quo, HIV is projected to become endemic in Taiwan after 2030

We constructed a deterministic model and fitted it to the HIV registry data among MSM from 1990 to 2019 in Taiwan (Fig. 2). We then projected the model under the status quo scenario—maintaining HIV test-and-treat rates as in 2019, without introducing new active PrEP programs following the 2018–2019 demonstration project—from 2020 to 2050. Figure 4A illustrates that under the status quo scenario, HIV incidence among MSM would initially decline rapidly from 2020 to 2026 before transitioning to an endemic stage. The number of new HIV infections would reach its lowest point at 406 in the years 2036–2037; subsequently, HIV incidence would begin to rise again.

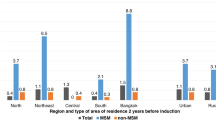

a Effect of a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) program serving young, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM aged 15–44 years at different PrEP coverage rate. b Effect of annual HIV testing among young, high-risk MSM aged 15–44 years, followed by the immediate initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in 90% of new HIV diagnoses. c Synergism between PrEP and HIV test-and-treat. The World Health Organization defines the threshold for HIV elimination as an annual HIV incidence of less than 1 per 1000 person-years.

High-coverage PrEP would eliminate HIV by 2030

In keeping with stochastic modeling results, Fig. 4A demonstrates that, in the absence of disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, initiating a PrEP program scaled up over a one-year period (2021) and achieving 50% coverage from 2022 onwards among young, high-risk MSM would effectively reduce HIV incidence to levels below the WHO HIV elimination threshold (HIV incidence: 1/1000 person-years) by 2030. This strategy could prevent up to 5615 (57.7%) new HIV infections by 2040. Should the PrEP coverage rate increase to 75% from 2022 onwards, the timeframe for achieving HIV elimination could be brought forward to the year 2027.

Intensive HIV test-and-treat strategy alone insufficient for HIV elimination

In accordance with the stochastic modeling results, Fig. 4B indicates that an intensive HIV test-and-treat campaign among young, high-risk MSM, scaled up over a 3-year period (2019–2021) with annual HIV testing followed by the immediate initiation of ART in 90% of new HIV cases, would substantially decrease HIV incidence, but it would not be sufficient to reduce it to levels below the WHO HIV elimination threshold. However, it would prevent 3863 (39.7%) new HIV infections by 2040.

Synergism between PrEP and HIV test-and-treat

Both stochastic and deterministic modeling demonstrate the synergistic effect between PrEP and HIV test-and-treat strategies. Neither a 25% coverage rate in the PrEP program alone nor an annual HIV testing with immediate ART strategy alone would eliminate HIV (Table 1, Fig. 4A, B). However, the combination of both interventions reduces the R0 of HIV to below 1 (Table 1) and decreases the trajectory of HIV incidence to levels below the WHO elimination threshold by 2029 (Fig. 4C).

Sensitivity analyses on HIV elimination under deterministic modeling

Table 3 demonstrates the impact of key parameters on the feasibility of HIV elimination via PrEP and, where applicable, the timing to achieve the WHO HIV elimination threshold, as determined by deterministic modeling. The coverage rate of PrEP among young high-risk MSM emerges as the single most critical factor. If the coverage rate decreases to 25%, HIV elimination becomes unattainable. Conversely, concerns often voiced—including a reduction in condom use among PrEP users (from the current 30% to 0%), suboptimal (75%) adherence to PrEP, an increase in the rate (to 10%) of emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance, an escalation (to 25%) in the proportion of young MSM engaging in high-risk behaviors, or the lack of initial HIV testing upon entry during the PrEP scale-up—may delay the timing to reach the WHO HIV elimination threshold but would not affect the ultimate feasibility of HIV elimination via scaling up PrEP program. These findings also underscore the importance of continuous education to ensure initial HIV testing upon entry and subsequent testing every 3 months among PrEP users, promote good adherence to minimize the emergence of drug resistance, and reduce high-risk behaviors to successfully eliminate HIV by 2030.

Cost and cost-effectiveness of a 50% coverage PrEP program in Taiwan

A PrEP program, including PrEP drugs (TruvadaTM, on-demand use), HIV testing, renal function testing, tests for sexually transmitted infections at follow-up, and PrEP case management services, would cost USD 2807.2 per person in the first year (Supplementary Table 9). Subsequently, the cost would be USD 2585.9 per person in each following year. For comparison, each new HIV diagnosis is associated with a lifetime medical cost of USD 177,165.5 for patients initially without AIDS, and USD 163,243.7 for those initially with AIDS (Supplementary Table 10). Implementing a PrEP program with a 50% coverage rate for young, high-risk MSM over a 20-year period (2021–2040) would amount to a cost of USD 227.2 million. However, this would prevent 4458 new HIV diagnoses (3329 non-late diagnoses and 1129 late diagnoses) and result in a gain of 33,864.6 QALYs, including 18,109.3 QALYs from preventing 3329 non-late HIV diagnoses and 15,755.3 QALYs from preventing 1129 late HIV diagnoses (Table 4). This prevention would save USD 774.1 million in HIV-associated medical costs and USD 851.9 million in human capital losses due to HIV. From a societal perspective, a PrEP program with a 50% coverage rate among young, high-risk MSM is highly cost saving, offering a benefit-cost ratio of 7.16 (for every 1 dollar spent on the PrEP program, 7.16 dollars in total societal costs, including medical costs and losses in human capital, would be saved).

Sensitivity analyses on cost saving from a high-coverage PrEP program in Taiwan

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of nine key parameters on the benefit-cost ratio estimate of a PrEP program. These parameters include the cost of PrEP (generic versus brand-name drugs), the timing of PrEP rollout (2019 versus 2023), the mode of PrEP use (on-demand versus daily use), the time horizon (10 years versus 30 years), the cost of ART (the cheapest first-line ART versus the most expensive second-line ART), the coverage rate of PrEP (25% versus 75%), adherence to PrEP (75% versus 100%), resistance to emtricitabine/tenofovir (0% versus 10%), and condom use (0% versus 30%). The adoption of a generic drug, costing one-third the price of brand-name drugs, and switching from an on-demand mode of PrEP use (the base scenario) to daily use (associated with a two-fold increase in drug consumption and cost) exert the largest impacts on the benefit-cost ratio estimate. Nonetheless, even under the scenario of daily use of brand-name TruvadaTM, a 50% coverage PrEP program remains cost saving, exhibiting a benefit-cost ratio of 3.80. The influence of other parameters on the benefit-cost ratio of a PrEP program is even more marginal.

The base scenario involves an on-demand PrEP program serving young, high-risk, HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) aged 15–44 years in Taiwan with adherence levels observed in the IPERGAY randomized trial (86% efficacy), scaled up over 1 year (2021), achieving 50% coverage from 2022 onwards, analyzed over a 20-year time horizon (2021–2040), assuming no risk compensation or emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance. The drug cost per person-year for on-demand PrEP use ranges from USD 2301 for TruvadaTM (the base scenario) and USD 767 for generic emtricitabine/tenofovir. For antiretroviral therapy (ART), the drug cost per patient-year ranges from USD 2026 for the cheapest first-line regimen to USD 8400 for the most expensive second-line regimen, with the real-world average cost in Taiwan (USD 6768) serving as the base scenario. Refer to the Methods section on pre-exposure prophylaxis for settings regarding risk compensation (0% condom use rate among PrEP users), drug resistance to emtricitabine/tenofovir (10%), and adherence to PrEP (75% vs. 100%).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to establish the necessity of high-coverage PrEP for the elimination of HIV in Taiwan, while also demonstrating its cost-saving benefits from an elimination perspective. Our stochastic modeling results show that an intense HIV test-and-treat strategy alone would substantially decrease HIV transmission but would not eliminate HIV under the estimated mixing level. In contrast, a PrEP program achieving 50% coverage among young, high-risk MSM would decrease the R0 of HIV to below 1, thereby facilitating the path toward HIV elimination. Our analyses indicate that factors such as risk compensation (leading to a 0% condom use rate among PrEP users), imperfect adherence at a rate of 75%, and sporadic emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance at a rate of 1% do not undermine the effectiveness of such a PrEP program. Deterministic modeling further predicted that the implementation of this program among young, high-risk MSM would drive the trajectory of HIV incidence in Taiwan below the WHO’s HIV elimination threshold (1 per 1000 person-years) by the year 2030. The cumulative cost of implementing such a PrEP program over a 20-year period would amount to USD 227.2 million; however, it would yield savings of USD 774.1 million in HIV-related medical expenses and an additional USD 851.9 million by averting losses in human capital. Consequently, the benefit-cost ratio stands at 7.16. The cost-savings of this PrEP intervention remain robust when subjected to variations in key parameters.

Rozhnova et al. indicated that an 82% PrEP coverage rate, in the context of existing ART coverage, could theoretically eliminate HIV among MSM in the Netherlands5. Jijón et al. subsequently showed that a minimum PrEP coverage of 55%, which has yet to be achieved, could eliminate the HIV epidemic among high-risk MSM in the Paris region6. Our preliminary deterministic modeling results were initially presented at the 21st International AIDS Conference in 2016, demonstrating that achieving a 50% coverage rate could eliminate the HIV epidemic among MSM in Taiwan73,74. In the current study, which builds upon those preliminary findings, we employed both deterministic modeling and stochastic modeling to demonstrate that, without a high-coverage PrEP program, the elimination of HIV in Taiwan remains unattainable. Given that successful HIV elimination hinges on attaining a high PrEP coverage among young, high-risk MSM—a demographic group particularly vulnerable due to financial constraints in accessing PrEP—policy interventions such as comprehensive public funding or health insurance reimbursements are imperative to broaden access to ensure the successful elimination of HIV in Taiwan by 2030.

The HPTN 052 randomized trial demonstrated that early initiation of ART prevents 96% of sexual HIV transmission34. The PARTNER study further showed that successful treatment with HIV viral load suppression eliminates sexual HIV transmission among MSM61. To maximize the population-level impact of HIV treatment as prevention on the HIV epidemic, Granich et al. proposed in 2009 that a strategy of universal annual HIV testing and immediate initiation of ART could effectively eliminate the generalized, heterosexual HIV epidemic in South Africa within a decade22. However, Powers et al. raised concern about this prediction, particularly questioning the assumed relative infectiousness during the acute stage—3.2-fold as used by Granich et al., compared to the 30.3-fold used by Powers et al.23,75,76. Similarly, Palk et al. proposed that the Danish HIV epidemic among MSM could be eliminated by the HIV test-and-treat strategy alone, even without the introduction of PrEP24,25. However, their modeling was based on an assumed relative infectiousness in the acute stage of only 3.4-fold25, similar to that assumed by Granich et al. 22. In our study, we employed a relative infectiousness during the acute phase of 26-fold, based on the empirical data from Hollingworth et al. 44. We found that while annual HIV testing followed by immediate ART would substantially decrease HIV transmission, it would not be sufficient to eliminate the HIV epidemic among MSM (Table 1, and Fig. 4B). These results underscore the essential role of PrEP in achieving HIV elimination within this population. The limitation of the HIV test-and-treat strategy is elucidated in Table 1, which indicates its minimal impact on reducing HIV transmissions during the acute infection stage—a short window period lasting 1–3 months. This brief period, characterized by heightened infectiousness compared to the chronic stage of the infection, is unlikely to be effectively captured by an annual testing schedule. Powers et al. estimated that, in Malawi, 38% of HIV transmissions occur in the acute stage23. Our results also showed that, in Taiwan, approximately one-third of all HIV transmissions occur during the acute stage, and further demonstrated that these transmissions can only be effectively mitigated through the implementation of a high-coverage PrEP program (Table 1). Our results regarding the limitations of an HIV test-and-treat approach for the eradication of HIV among MSM echo the conclusions drawn by Powers et al. and Akullian et al. concerning the strategy’s inadequacy for eliminating HIV among heterosexual populations in Africa23,26. Additionally, achieving the objective of annual HIV testing for young, high-risk MSM in Taiwan presents a formidable challenge due to factors such as stigma, discrimination, and the legal complexities surrounding an HIV diagnosis, particularly during and after the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It needs to be highlighted that a PrEP program, in fact, would enforce the HIV test-and-treat intervention since the prescription of PrEP requires a recent negative HIV test at entry to the program and every 3 months thereafter. With HIV testing as the same entry point for PrEP (for HIV-negative individuals) and ART (for HIV-positive individuals), both programs may act synergistically to achieve HIV elimination. The modeling study by Lima et al. shows that the HIV epidemic among MSM in British Columbia, which was less responsive to the HIV test-and-treat strategy than the HIV epidemic among other key populations, might be eliminated with the provision of PrEP77. Similarly, our stochastic and deterministic modeling demonstrates the synergism between PrEP and HIV test-and-treat strategies. Neither a 25%-coverage-rate PrEP program alone nor an annual HIV testing with immediate ART strategy alone would eliminate HIV. However, the combination of both interventions would reduce the R0 of HIV to below 1 (Table 1) and decrease the HIV epidemic to levels below the elimination threshold by 2030 (Fig. 4C).

In comparison to an intensive HIV test-and-treat strategy, high-coverage PrEP demonstrates greater resilience to disruptions caused by pandemics due to the potential for over-the-counter distribution of PrEP78,79, whereas the former approach relies on an operational medical care system. However, our modeling data highlights that suboptimal adherence could negate the benefits of high PrEP coverage, as demonstrated by the isoline of the R0 under different adherence and coverage rates (Fig. 3). Consequently, while pharmacist-led distribution or over-the-counter availability may expedite reaching the target coverage rate among young, high-risk MSM78 and may be particularly useful during pandemic disruptions79, educational interventions aimed at the client population are crucial for ensuring optimal adherence.

One of the major concerns for PrEP is risk compensation10,11,12. While randomized controlled trials did not support that PrEP is associated with a decrease in condom use1,2,80, most observational studies suggested that PrEP users are more likely to have new sexually transmitted infections than non-users11,81 although this could be a result of the higher baseline risk behaviors in PrEP users. Even if risk compensation is 100% (all users stop using condoms), our modeling results showed that such a decrease in condom use among those who use PrEP (which acts like a molecular condom) would have a negligible effect on the feasibility of achieving HIV elimination (see Table 2 for stochastic modeling and Table 3 for deterministic modeling). Jijón et al. also reported similar results, indicating that risk compensation with none of the PrEP users using condoms only minimally increases the PrEP coverage rate required for elimination6. Likewise, our study further revealed that the other two often-raised concerns for PrEP, imperfect (75%) adherence, and occasional (1%) drug resistance, do not have a meaningful impact on the effect of a high-coverage PrEP program in eliminating the HIV epidemic among MSM.

Cost and cost-effectiveness are critical considerations in policymaking. Previous studies on the cost-effectiveness of PrEP generally show that, under a persistent HIV epidemic, PrEP is cost-effective but not cost saving unless over a very long (80 years) time horizon or with massive price reduction16,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91. In contrast, we found that PrEP using the brand-name TruvadaTM is highly cost saving over a 20-year time horizon when implemented to eliminate the HIV epidemic by averting a substantial amount of HIV-associated lifetime medical costs and HIV-associated losses in human capital. Although the cost required to provide high-coverage PrEP could be a constraint for implementation, our results actually show that, using the brand-name TruvadaTM, funding for 50% of young, high-risk MSM in Taiwan requires a total of USD 227.2 million over a 20-year period from 2021 to 2040, or an annual budget of approximately USD 14.8 million, after adjustment for 3% annual discount rate. This amount is only one-third of the current annual budget for publicly funded annual seasonal influenza vaccination in Taiwan (approximately USD 50 million for 6 million doses). Similar to previous studies83,84, a massive reduction in the cost of PrEP drugs after the expiration of patents would make the case for high-coverage PrEP even more compelling.

On the contrary, if comprehensive publicly funded or health insurance-reimbursed PrEP is not provided for young high-risk MSM, there will be danger ahead. First, the unmet need will force potential users to purchase cheap generic PrEP drugs, often of questionable quality, from overseas sources (although some studies support the equivalence in bioavailability between generic and brand-name drugs92). Second, without a public program that mandates regular HIV testing at entry and at 3-month intervals thereafter, generic PrEP drug users are at high risk of unknowingly taking PrEP after they already acquired HIV. Third, in the absence of case management services or professional counseling by physicians or pharmacists, there will be no way to ensure good adherence among users. The end result could be the disastrous emergence of resistance to PrEP drugs. Furthermore, since emtricitabine/tenofovir are also important components of ART, an emergence of drug resistance to emtricitabine/tenofovir could compromise not only the efficacy of PrEP but also the efficacy of ART.

The strength of the present study is the precise model parameterization based on high-quality Taiwan national data, including HIV registry, HIV cascade, and mortality data (provided by Taiwan CDC), vital statistics (from Ministry of Interior), and HIV-associated medical cost (based on Taiwan National Health Insurance database). Additional advantages include the use of a comprehensive model structure that considers both the natural history of HIV and the HIV care continuum, the use of a risk/age-structured model to account for population trends, the application of both stochastic and deterministic modeling to yield robust conclusions, and the use of the best available estimates for key parameters, including the relative infectiousness during the acute stage and the rate of HIV disease progression.

Our study is subject to several notable limitations. First, our modeling analysis does not account for the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in 2019. Due to the absence of reliable HIV surveillance data spanning the years 2020–2023, our deterministic model was calibrated using data collected from 1990 through 2019. Consequently, projections in our counterfactual scenario relied on the epidemiological landscape of 2019, and the high-coverage PrEP program was assumed to be initiated in 2021, although a sensitivity analysis of the scenario to initiate the high-coverage PrEP program in 2023 does not alter the outcome. Second, while our study emphasized cost as a primary barrier to the PrEP adoption in Taiwan, we did not scrutinize other non-financial determinants that could influence PrEP acceptability among Taiwan’s MSM population. Factors such as distrust of public health authorities and stigmatization associated with PrEP usage may pose substantial obstacles to PrEP program implementation. Third, our argument for PrEP funding was framed strictly within an economic context, drawing conclusions from cost-effectiveness analyses. However, societal dimensions cannot be ignored. Public support for scaling up the PrEP program is pivotal.

An important caveat is that with optimal adherence, PrEP with oral emtricitabine/tenofovir can be substantially more effective (97–99%) in preventing HIV acquisition than the 86% efficacy observed in the IPERGAY and PROUD randomized trials1,2,3,93, which was used in the main analysis of our modeling. Long-acting injectable cabotegravir has demonstrated superior efficacy in preventing HIV acquisition compared to oral emtricitabine/tenofovir among MSM and women in the HPTN083 and HPTN084 randomized trials94,95, though its higher cost remains a major barrier to wider access, and integrase strand transfer inhibitor resistance may emerge in cases of PrEP failure96. Recently, Gilead’s twice-yearly long-acting injectable lenacapavir demonstrated 96% efficacy in preventing HIV acquisition and superiority to oral emtricitabine/tenofovir in men and gender-diverse persons in the phase 3 PURPOSE-2 trial97. The higher effectiveness of PrEP with optimal adherence or long-acting injectable drugs may help reduce the required coverage of PrEP programs to achieve the goal of HIV elimination.

It should be emphasized that universal access to ART and viral load suppression for people living with HIV is a prerequisite for a high-coverage PrEP program to achieve the goal of HIV elimination. In our modeling, the status quo HIV test-and-treat scenario is based on the Taiwan CDC’s HIV case management system, which ensures that 93% of diagnosed patients receive ART and 95% of treated patients achieve viral load suppression37. Without the effect of ART in preventing HIV transmission from HIV-positive individuals, it would not be feasible for a 50% coverage PrEP program among HIV-negative individuals alone to reduce the R0 of HIV to less than 1 (Table 1). Therefore, our conclusion may not be generalized to countries or regions where ART is not universally available to all people living with HIV, or where viral load suppression is not achieved in the majority of treated patients.

In conclusion, a high-coverage PrEP program aiming for a 50% coverage rate among young, high-risk MSM is necessary, effective, and highly cost saving for eliminating HIV in Taiwan by 2030. Our findings strongly support scaling up PrEP for young, sexually active, high-risk, HIV-negative MSM, in synergism with ART for all people living with HIV, to end the HIV epidemic in Taiwan and globally.

Data availability

To protect privacy, the Taiwan National HIV Registry dataset is accessible through the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei, Taiwan, upon approval of a research proposal. All data supporting this study’s findings are available within the paper, Supplementary Data 1–4, and Supplementary Information. The deterministic and stochastic model structures, parameters, values, and data references are detailed in Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Data 2, and Supplementary Information. Data on the effects of risk compensation, low-level (1%) emtricitabine/tenofovir resistance, and non-adherence on the impact of a PrEP program are provided in Supplementary Data 3. The numerical results underlying the graphs and charts in the main figures are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

Code availability

We conducted the deterministic modeling using STELLA® version 10.0.6 (ISEE Systems, Lebanon, NH 03766, USA). Stochastic modeling was conducted using R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The differential equations for deterministic modeling and the R scripts for stochastic modeling are provided in Supplementary Notes 4 and 5, respectively. The version of the code for both models has been deposited in Zenodo and is available at: https://zenodo.org/records/1468884098.

References

McCormack, S. et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 387, 53–60 (2016).

Molina, J. M. et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2237–2246 (2015).

Molina, J. M. et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 4, e402–e410 (2017).

Grulich, A. E. et al. Population-level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high-coverage roll-out of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: the EPIC-NSW prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV 5, e629–e637 (2018).

Rozhnova, G. et al. Elimination prospects of the Dutch HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in the era of preexposure prophylaxis. AIDS 32, 2615–2623 (2018).

Jijón, S. et al. Can HIV epidemics among MSM be eliminated through participation in preexposure prophylaxis rollouts?. AIDS 35, 2347–2354 (2021).

Killelea, A. et al. Financing and delivering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to end the HIV epidemic. J. Law Med. Ethics 50, 8–23 (2022).

Marcus, J. L., Killelea, A. & Krakower, D. S. Perverse Incentives—HIV Prevention and the 340B Drug Pricing Program. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2064–2066 (2022).

Johnson, J., Killelea, A. & Farrow, K. Investing in National HIV PrEP Preparedness. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 769–771 (2023).

Quaife, M. et al. Risk compensation and STI incidence in PrEP programmes. Lancet HIV 7, e222–e223 (2020).

Hoornenborg, E. et al. Sexual behaviour and incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men using daily and event-driven pre-exposure prophylaxis in AMPrEP: 2 year results from a demonstration study. Lancet HIV 6, e447–e455 (2019).

Baltes, V. et al. Sexual behaviour and STIs among MSM living with HIV in the PrEP era: the French ANRS PRIMO cohort study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 27, e26226 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Discontinuation, suboptimal adherence, and reinitiation of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 9, e254–e268 (2022).

Laurent, C. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among men who have sex with men who use event-driven or daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (CohMSM-PrEP): a multi-country demonstration study from West Africa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 606–614 (2023).

Hurt, C. B., Eron, J. J. Jr. & Cohen, M. S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and antiretroviral resistance: HIV prevention at a cost?. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53, 1265–1270 (2011).

Shen, M., Xiao, Y., Rong, L., Meyers, L. A. & Bellan, S. E. The cost-effectiveness of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and early antiretroviral therapy in the presence of drug resistance among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. BMC Med. 16, 58 (2018).

Nosyk, B. et al. Ending the HIV epidemic in the USA: an economic modelling study in six cities. Lancet HIV 7, e491–e503 (2020).

Grulich, A. E. & Bavinton, B. R. Scaling up preexposure prophylaxis to maximize HIV prevention impact. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 17, 173–178 (2022).

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Fast track: ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. Available at: https://www.aidsdatahub.org/resource/unaids-fast-track-ending-aids-epidemic-2030-report (accessed 4 January 2025) (2014).

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global AIDS Strategy 2021-2026—End inequalities. End AIDS. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-strategy-2021-2026_en.pdf (accessed 4 January 2025) (2021).

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2024 global AIDS report —The urgency of now: AIDS at a crossroads. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/global-aids-update-2024 (accessed 4 January 2025) (2024).

Granich, R. M., Gilks, C. F., Dye, C., De Cock, K. M. & Williams, B. G. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet 373, 48–57 (2009).

Powers, K. A. et al. The role of acute and early HIV infection in the spread of HIV and implications for transmission prevention strategies in Lilongwe, Malawi: a modelling study. Lancet 378, 256–268 (2011).

Okano, J. T. et al. Testing the hypothesis that treatment can eliminate HIV: a nationwide, population-based study of the Danish HIV epidemic in men who have sex with men. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 789–796 (2016).

Palk, L., Gerstoft, J., Obel, N. & Blower, S. A modeling study of the Danish HIV epidemic in men who have sex with men: travel, pre-exposure prophylaxis and elimination. Sci. Rep. 8, 16003 (2018).

Akullian, A. et al. The effect of 90-90-90 on HIV-1 incidence and mortality in eSwatini: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV 7, e348–e358 (2020).

Brizzi, F. et al. Tracking elimination of HIV transmission in men who have sex with men in England: a modelling study. Lancet HIV 8, e440–e448 (2021).

Fang, C. T. et al. Decreased HIV transmission after a policy of providing free access to highly active antiretroviral therapy in Taiwan. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 879–885 (2004).

Lee, Y. C. et al. Non-opioid recreational drug use and a prolonged HIV outbreak among men who have sex with men in Taiwan: an incident case-control study, 2006-2015. J. Formos. Med. Assoc.121, 237–246 (2022).

Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Statistics of HIV/AIDS. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Category/MPage/kt6yIoEGURtMQubQ3nQ7pA (accessed 24 August 2023) (2023).

World Health Organization. Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV (WHO, 2015).

Chen, Y. H. et al. Routine HIV testing and outcomes: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am. J. Prev. Med. 62, 234–242 (2022).

UNAIDS. 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf (accessed 24 August 2023) (2014).

Cohen, M. S. et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 493–505 (2011).

Chen, C. H. Current HIV situation and control policy in Taiwan. In Taiwan Public Health Association 2014 Annual Meeting, Taipei, Taiwan (October 26, 2014) (2014).

Tsai, Y. C. on behalf of Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. HIV epidemiology in Taiwan. In Taiwan Public Health Association 2019 Annual Meeting, Taipei, Taiwan (September 27, 2019) (2019).

Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Taiwan achieved the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets https://www.mohwpaper.tw/adv3/maz31/utx02.asp (December 1, 2021) (accessed 24 August 2023) (2021).

Lee, Y. C. et al. Awareness and willingness towards pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection among individuals seeking voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in Taiwan: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open 7, e015142 (2017).

Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) program. https://www.cdc.gov.tw/Category/MPage/tXBKgpeVZ9l9929TEdZGJw (accessed 17 August 2024) (2024).

Lin, K. Y. et al. Effect of a hepatitis A vaccination campaign during a hepatitis A outbreak in Taiwan, 2015-2017: a modeling study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 70, 1742–1749 (2020).

Lo, T. et al. Early HIV diagnosis enhances quality-adjusted life expectancy of men who have sex with men living with HIV: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 57, 85–96 (2024).

Longini, I. M. Jr., Clark, W. S., Gardner, L. I. & Brundage, J. F. The dynamics of CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline in HIV-infected individuals: a Markov modeling approach. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 4, 1141–1147 (1991).

Veugelers, P. J. et al. Determinants of HIV disease progression among homosexual men registered in the Tricontinental Seroconverter Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 140, 747–758 (1994).

Hollingsworth, T. D., Anderson, R. M. & Fraser, C. HIV-1 transmission, by stage of infection. J. Infect. Dis. 198, 687–693 (2008).

The Insight START Study Group Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 795–807 (2015).

Chen, C. J., Ting, C. Y., Tsai, Y. F. & Hsiung, P. C. Intimacy of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Chin. J. Psychol. Health 17, 97–126 (2004).

Ray, M. et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 24, 123–137 (2010).

May, M. T. et al. Mortality according to CD4 count at start of combination antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients followed for up to 15 years after start of treatment: collaborative cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, 1571–1577 (2016).

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 4, e349–e356 (2017).

Kitahata, M. M. et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1815–1826 (2009).

Lundgren, J. D. et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 795–807 (2015).

Taiwan Minister of Interior. Population statistics and vital statistics. https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346 (accessed 1 August 2018) (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men: a modified Laska, Meisner and Siegel procedure taking into account internet populations. Sex. Transm. Infect. 89, 142–147 (2013).

Ezoe, S., Morooka, T., Noda, T., Sabin, M. L. & Koike, S. Population size estimation of men who have sex with men through the network scale-up method in Japan. PLoS ONE 7, e31184 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. Application of network scale up method in the estimation of population size for men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. PLoS ONE 10, e0143118 (2015).

Koblin, B. A. et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS 20, 731–739 (2006).

Chiu, C. M. & Ting, C. I. Impact of HIV case management on patients’ behaviors and health. Taiwan J. Public Health 29, 299–310 (2010).

Patel, P. et al. Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review. AIDS 28, 1509–1519 (2014).

Vittinghoff, E. et al. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am. J. Epidemiol. 150, 306–311 (1999).

World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service, Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach (WHO, 2021).

Rodger, A. J. et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet 393, 2428–2438 (2019).

Chu, Y. H. et al. Taiwan guideline on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention—2018 update. J. Microbiol Immunol. Infect. 53, 1–10 (2020).

Hoagland, B. et al. High pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early adherence among men who have sex with men and transgender women at risk for HIV Infection: the PrEP Brasil demonstration project. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 20, 21472 (2017).

Hoornenborg, E. et al. Men who have sex with men more often chose daily than event-driven use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: baseline analysis of a demonstration study in Amsterdam. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 21, e25105 (2018).

Reyniers, T. et al. Choosing between daily and event-driven pre-exposure prophylaxis: results of a Belgian PrEP demonstration project. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 79, 186–194 (2018).

Zablotska, I. B. et al. High adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and no HIV seroconversions despite high levels of risk behaviour and STIs: the Australian demonstration study PrELUDE. AIDS Behav. 23, 1780–1789 (2019).

Ryan, K. E. et al. Protocol for an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) population level intervention study in Victoria Australia: the PrEPX study. Front. Public Health 6, 151 (2018).

Lo, T. Impact of early HIV diagnosis on quality-adjusted life expectancy in HIV-infected men who having sex with men (MSM). Master thesis (Advisor: Chi-Tai Fang), National Taiwan University (2015).

Hwang, J. S., Hu, T. H., Lee, L. J. & Wang, J. D. Estimating lifetime medical costs from censored claims data. Health Econ. 26, e332–e344 (2017).

Taiwan Director-General of Budget and Accounting and Statistics. Per capita gross domestic product. https://eng.dgbas.gov.tw/public/data/dgbas03/bs2/yearbook_eng/Yearbook2018.pdf (accessed 1 October 2019) (2018).

Marseille, E., Larson, B., Kazi, D. S., Kahn, J. G. & Rosen, S. Thresholds for the cost-effectiveness of interventions: alternative approaches. Bull. World Health Organ. 93, 118–124 (2015).

Grimm, V. et al. Towards better modelling and decision support: Documenting model development, testing, and analysis using. Trace. Ecol. Model. 280, 129–139 (2014).

Wu, H. J., Chang, C. C. & Fang, C. T. Scaling-up pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as a strategy to eliminate HIV transmission among men who have sex with men (MSM): a modeling study [Poster exhibition]. In The 21th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2016); Durban, South Africa (July 20, 2016) (2016).

Fang, C. T. Scaling-up pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as a strategy to eliminate HIV transmission among men who have sex with men (MSM): a modeling study [Oral presentation]. In The 21th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2016). The Global Forum on MSM and HIV (MSMGF) Preconference: Action+Access: The Rights and Demands of Gay and Bisexual Men in the HIV Response, July 16, 2016, Durban, South Africa (2016).

Williams, B. G., Granich, R. & Dye, C. Role of acute infection in HIV transmission. Lancet 378, 1913 (2011).

Hayes, R. J. & White, R. G. Role of acute infection in HIV transmission. Lancet 378, 1913–1914 (2011).

Lima, V. D. et al. Can the combination of TasP and PrEP eliminate HIV among MSM in British Columbia, Canada. Epidemics 35, 100461 (2021).

Kazi, D. S., Katz, I. T. & Jha, A. K. PrEParing to end the HIV epidemic—California’s route as a road map for the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2489–2491 (2019).

Krakower, D. & Marcus, J. L. Free the PrEP—over-the-counter access to HIV preexposure prophylaxis. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 481–483 (2023).

Grant, R. M. et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2587–2599 (2010).

Traeger, M. W. et al. Association of HIV preexposure prophylaxis with incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals at high risk of HIV infection. JAMA 321, 1380–1390 (2019).

Drabo, E. F., Hay, J. W., Vardavas, R., Wagner, Z. R. & Sood, N. A Cost-effectiveness analysis of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV among Los Angeles County men who have sex with men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, 1495–1504 (2016).

Nichols, B. E., Boucher, C. A. B., van der Valk, M., Rijnders, B. J. A. & van de Vijver, D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention in the Netherlands: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 1423–1429 (2016).

Cambiano, V. et al. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men in the UK: a modelling study and health economic evaluation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 85–94 (2018).

Suraratdecha, C. et al. Cost and cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in two hospitals in Thailand. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 21, e25129 (2018).

van de Vijver, D. et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget effect of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention in Germany from 2018 to 2058. Eur. Surveill.24, 1800398 (2019).

Choi, H. et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV in men who have sex with men in South Korea: a mathematical modelling study. Sci. Rep. 10, 14609 (2020).

Kazemian, P. et al. The cost-effectiveness of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) preexposure prophylaxis and hiv testing strategies in high-risk groups in India. Clin. Infect. Dis. 70, 633–642 (2020).

Wong, N. S. et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for MSM in low HIV incidence places: should high risk individuals be targeted?. Sci. Rep. 8, 11641 (2018).

Schneider, K., Gray, R. T. & Wilson, D. P. A cost-effectiveness analysis of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in Australia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 1027–1034 (2014).

Juusola, J. L., Brandeau, M. L., Owens, D. K. & Bendavid, E. The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Ann. Intern. Med. 156, 541–550 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. InterPrEP: internet-based pre-exposure prophylaxis with generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtrictabine in London - analysis of pharmacokinetics, safety and outcomes. HIV Med. 19, 1–6 (2018).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). PrEP. https://www.cdc.gov/stophivtogether/hiv-prevention/prep.html (accessed 19 August 2024) (2024).

Landovitz, R. J. et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 595–608 (2021).

Delany-Moretlwe, S. et al. Cabotegravir for the prevention of HIV-1 in women: results from HPTN 084, a phase 3, randomised clinical trial. Lancet 399, 1779–1789 (2022).

Marzinke, M. A. et al. Extended analysis of HIV infection in cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men receiving injectable cabotegravir for HIV prevention: HPTN 083. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e0005323 (2023).

Kelley, C. F. et al. Twice-yearly lenacapavir for HIV prevention in men and gender-diverse persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 1261–1276 (2025).

Wu, H. J. et al. Supplementary replication material of articles published in Communications Medicine: A modeling study of pre-exposure prophylaxis to eliminate HIV in Taiwan by 2030. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14688840 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study received financial support from the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology under grant numbers MOST-104-2314-B-002-035-MY2 and MOST-106-2314-B-002-115-MY3, awarded to C.-T.F. Additional funding was provided by the Population Health Research Center from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Taiwan Ministry of Education (grant number NTU-112L9004). The study also received support from the Infectious Diseases Research and Education Center, a collaboration between the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare and the National Taiwan University. The funding agencies played no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of data, the modeling work, the preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors express their gratitude to the Taiwan CDC and Dr. Chang-Hsun Chen for providing the Taiwan national HIV registry dataset, HIV case management statistics, and HIV cascade data for MSM cases for this study. The authors also thank Prof. Tzu-Pin Lu for his invaluable assistance with R programming for stochastic modeling. A preliminary version of the deterministic modeling, which evaluated the impact of expanding HIV test-and-treat strategy on the HIV epidemic among MSM in Taiwan based on data available up to the end of 2014, served as the Master Thesis of the co-first author C.-C.C. (National Taiwan University, 2015, advisor: C.-T.F.). The projected lifetime survival curves and loss of quality-adjusted life expectancy for MSM living with HIV in Taiwan (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11) were part of the Master Thesis of the co-first author T.L. (National Taiwan University, 2015, advisor: C.-T.F.). A preliminary version of the deterministic modeling and cost-effectiveness analysis assessing the impact of scaling up PrEP for MSM in Taiwan, based on data up to the end of 2015, was selected for oral presentation and poster exhibition at the 21st International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2016), July 16–22, 2016, in Durban, South Africa. This work also constituted the Master Thesis of the first author Huei-Juan Wu (National Taiwan University, 2016, advisor: C.-T.F.). A preliminary version of the stochastic modeling evaluating the impact of PrEP on the R0 of HIV among MSM in Taiwan was the Master Thesis of the co-first author Y.-P.C. (National Taiwan University, 2018, advisor: C.-T.F.). An estimation of the mortality rate of MSM living with HIV in Taiwan by age, period, disease stage, HIV care cascade, and antiretroviral therapy status, conducted by the co-first author Y.-H.C., was selected for poster exhibition at the 10th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2019), July 21-24, 2019, in Mexico City, Mexico.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J.W. and C.T.F. conceived and designed the study, conducted deterministic modeling, and performed economic analyses. Y.P.C. and C.T.F. were responsible for stochastic modeling. C.C.C. and C.T.F. initially developed the deterministic model. Y.H.C. and C.T.F. reviewed the literature for model parameterization on the natural history of HIV infection across age strata, as well as the substantially higher infectiousness during the acute HIV infection stage and the AIDS stage. Y.H.C., H.J.W., and C.T.F. estimated the mortality rate of MSM living with HIV in Taiwan by age, period, disease stage, care cascade, and antiretroviral therapy status. T.L. and C.T.F. projected the lifetime survival curve and loss of quality-adjusted life expectancy for MSM living with HIV and analyzed data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance database to estimate the costs of antiretroviral therapy and medical care for HIV patients in Taiwan. C.T.F. secured funding and provided overall supervision for the study. C.T.F., H.J.W., Y.P.C., and C.C.C. drafted the manuscript. Y.H.C. plotted Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3. T.L. plotted Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11. C.T.F. revised and finalized the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version. H.J.W., Y.P.C., Y.H.C., C.C.C., L.T., and C.T.F. contributed equally to this work as the first author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [Peer reviewer reports are available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions