Abstract

Background

Understanding the role of space weather, specifically Geomagnetic Disturbances (GMDs) caused by solar activity, on health outcomes is unclear. One emerging link includes the impact of space weather on myocardial infarctions (MI). In this study we examined the correlation between MI and GMDs in Brazil.

Methods

We used a database from the public health in Brazil, focusing on the city of São José dos Campos (23° 10′ 44″ S, 45° 53′ 13″ W), located in the state of São Paulo, during the period of 1998–2005. We focused on admissions for MIs, which included a total of 871 men and 469 women. We categorized the MI data into three age groups: age 30 and younger, age 31–60, and age over 60. Additionally, we incorporated Planetary Index (Kp) data as an indicator of variations in the Earth’s geomagnetic field resulting from solar disturbances, categorized as quiet, moderate, or disturbed days. In our analysis, we employed two methods: statistical counting and the unsupervised clustering known as K-Means, considering the attributes of age, sex, and geomagnetic condition.

Results

Here we show that geomagnetic conditions have an impact on MI cases, particularly for women. The rate of relative frequency of MI cases during disturbed geomagnetic conditions is almost three times greater compared to quiet geomagnetic conditions. Using the unsupervised K-Means algorithm, the results indicate that the group associated with disturbed geomagnetic conditions has a higher incidence of MIs in women.

Conclusions

Overall, our results provide evidence that women may exhibit a higher susceptibility to the effects of geomagnetic disturbances caused by solar activity on MI.

Plain Language Summary

Whether geomagnetic disturbances that occur due to the impact of the solar wind on the magnetosphere (outermost region of the atmosphere where the solar wind meets Earth’s magnetic field), can affect human health, or not, is unclear. In this study, we used a public health database from São Paulo, Brazil, containing cases of hospitalizations due to heart attacks during the period 1998-2005. Using data from the Earth’s magnetic field, we classified days as either quiet, moderate, or disturbed and examined their influence on heart attack rates. We found that the proportion of heart attacks was higher in women compared to men on the disturbed days. Our results suggest that women have a greater susceptibility to these geomagnetic conditions and should be monitored for potential heart attacks on days when geomagnetic conditions are disturbed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Sun is essential to life on Earth, and solar radiation stands as one of the most impactful physical climate forces on the planet. Moreover, solar radiation plays a central role in photosynthesis - a process responsible for converting light energy into chemical energy and inorganic carbon into organic compounds, which then is introduced into the food chain. This mechanism sustains, virtually, all life on Earth. Photosynthesis also serves as a sink for anthropogenic carbon. The transferring of carbon dioxide from to organic tissues in plants helps to mitigate its accumulation in the atmosphere. This action plays a vital role in reducing the intensification of the greenhouse effect and the subsequent planetary warming. Furthermore, in organisms, the solar radiation spectrum, particularly the ultraviolet radiation (UV) within the range of 280–400 nm, can lead to detrimental effects and serious illnesses such as cancer due to excessive exposure1. On the other hand, an optimal level of UV exposure is beneficial as it contributes to the synthesis of vitamin D within the human body1. In addition, solar radiation serves as an alternative and sustainable source for electricity generation.

The Sun also influences other domains, notably space weather, which impacts the geomagnetic field (GMF) within the Earth’s magnetosphere. This phenomenon is referred to as a geomagnetic disturbance (GMD). GMDs occur during or following intense solar events like coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which expel substantial amounts of electromagnetic particles into space from the Sun’s surface. A majority of these particles traverse space and collide with the magnetosphere’s sheath, potentially causing compression of the magnetosphere up to a distance of five Earth radii from the planet’s center2,3,4. These GMDs occur more frequently at the peak of the 11-year solar cycle, characterized by elevated energy emissions due to increased sunspot activity in regions near the Sun’s equatorial plane5. The magnitude of solar cycles (or Schwabe cycle) is also discernible in natural phenomena, such as tree rings in vegetation. A notable correlation exists between the number of sunspots and the thickness of tree rings6,7,8.

The impacts of GMDs on satellites and radio communication systems have sparked numerous studies. These events notably influence the performance of technologies reliant on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), resulting in reduced positioning accuracy and temporary communication loss, also known as ‘loss of lock’9,10,11,12.

The quest for a correlation between GMDs and several biological indicators has previously been undertaken by the Russian scientists Chizhevskii13,14 and Vernadsky15,16. Apart from emphasizing the significance of latitudinal location, they also identified additional evidence, including the connections between sunspots and occurrences of epidemics, epizootics, bacterial reproduction, and animal migrations. Heliogeophysical factors have a complex nature and, consequently, influence all biological functional systems which can manifest themselves in various pathologies17.

Presently, numerous studies have identified a possible cause-effect relationship between GMDs and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), as well as myocardial infarction (MI)18,19,20,21,22,23,24.

More specific studies have been conducted on the influence of GMDs on human health24,25,26,27,28. Another proposal argues that GMF acts as a secondary synchronizer of circadian rhythms, in addition to the primary synchronizer of the day-night-light cycle. This secondary synchronization could operate through signals from Schumann resonances (SR), which are a set of spectral peaks in the extremely low frequency (ELF) portion of the Earth’s electromagnetic field spectrum27,28. The SR signal is generated within the cavity formed between the Earth’s surface and the D region of the ionosphere, with a fundamental frequency around 7.8 Hz during the day and can vary depending on heliogeophysical conditions by up to 20%. Moreover, the resonance can also vary according to the height of the D layer and tropical storm activities, leading to peaks around 14, 20, 26, 33, 39, 45, and 51 Hz24,25,26,28,29.

Comparing the SR signal with biological signals, it is observed that the first SR range (0–35 Hz) coincides with the first electroencephalography (EEG) range (0.5–30 Hz)30. Humans, primates, birds, and fishes have been shown to detect and react to low ultra-low frequency (ULF) and extremely low frequency (ELF) signals. It is also acknowledged that these low frequencies are used for biological telecommunication, vital in brain-cell and cell-cell communication, which is necessary to maintain homeostatic relationships. These processes ensure the organism’s internal conditions remain constant, which is essential for sustaining life31,32,33.

There is an interdependence between the SR signal and the height of the D layer, which in turn is affected by changes in solar and geomagnetic activity. This relationship can be observed through the strong correlation between GMSs, GMDs (as observed by the Kp index, for example), and sunspot activity with the SR signal30. Consequently, when GMDs contribute to raising the intensity and frequency of the SR signal to extreme levels, it is postulated that this could impact brain waves and disrupt the balance between melatonin and serotonin. Such disruptions can in turn influence the functions of organs and systems crucial for circadian-driven homeostasis, including blood pressure, respiration, immunity, cardiac functions, neurological processes, and reproductive systems. Thus, in this interpretation, GMDs and GMSs are categorized as natural hazards for living beings31.

In our study, we do not disregard, of course, other well-established factors from the medical literature that strongly contribute to or provoke these diseases, such as genetic issues, sedentary lifestyles, and habits. We are solely investigating the probability of an additional component that might impact biological systems, potentially contributing to the triggering of biological events through geomagnetic disturbances (GMDs)28,34,35. Furthermore, it is worth noting that most studies employing this approach have been conducted at high latitudes, and research into the influence of the Sun, GMFs, and GMDs on living beings in medium and low latitudes remains relatively scarce23.

The results reveal evidence of women’s susceptibility, who despite having fewer cases of MIs, in disturbed geomagnetic conditions reach higher proportions than in men.

Methods

This research uses retrospective data of age, sex, clinical outcome and cause of death. The project was approved by the Municipal Secretary of Health of São José dos Campos, São Paulo state, according to their specific ethical and administrative regulations and Brazilian data protection law (DPL). As the data were retrospective, collected under protection of DPL and provided without any identification, as always treated as groups in the analysis, the Municipal Secretary of Health waived the need of specific individual informed consent. All data were provided to the researchers by the Municipal Secretary of Health without any other personal identification information to ensure the anonymization.

The data for this study were obtained through a request made directly to the Municipal Secretary of Health of São José dos Campos, São Paulo state, in 2005.

In our analyses, we employed the following methodology following the categorization into geomagnetically quiet, moderate, and disturbed days. We examined the occurrences while considering the patients’ age (segmented into ranges) and sex, along with the geomagnetic conditions (Fig. 1).

Participants

The data (admissions and deaths) for myocardial infarctions (MI) were obtained from the Unified Health System (SUS) database in Brazil. These cases pertained to residents within São José dos Campos municipality (23° 10′ 44″ S, 45° 53′ 13″ W) in the state of São Paulo (population: currently around 737,000 inhabitants and 87 km far from the state capital: São Paulo). The SUS is a public healthcare system, and the coverage rate of the public health network in most municipalities in Brazil is around 70%, with the remaining 30% being served by the complementary healthcare network.

The data comprise the period from January 1, 1998 to May 31, 2005 which almost entirely comprised solar cycle 23 (1996–2006)36. The selection of heart attack cases was based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), specifically version 2019 (Table 1)37.

For the status of hospitalized patients there are five definitions: 1 Discharge; 2 Death, 3 Transfer, 4 Permanent, and 5 Evasion.

Data from 1340 patients hospitalized for myocardial infarction were analyzed, of which 469 were women and 871 were men and divided into three groups: age ≤30; age >30 and age ≤60; and age >60 years.

Statistics and reproducibility

We used the Kp-index to quantify or categorize the intensity and fluctuations of the geomagnetic field (GMF) or Geomagnetic Disturbances (GMDs). The Kp-index is the global geomagnetic activity index that is based on 3-h measurements from ground-based magnetometers around the world. Each station is calibrated according to its latitude and yields a specific K-index, reflecting the geomagnetic activity recorded at the magnetometer’s location. The Kp-index ranges from 0 to 9, with 0 indicating minimal geomagnetic activity and 9 denoting severe geomagnetic activity. The data are public and they were obtained from the Kyoto38. Kyoto data is transferred to Helmholtz Centre Potsdam39.

The data were converted from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) to local time (−3 hours), and we have presented the classification of the Kp index into quiet, moderate, and strongly disturbed days based on the daily summation of Kp values (Table 1).

In our statistical classification, we consider the five definitions of status as admissions.

We combined the data of myocardial infarctions and Kp index following the rules in Table 2, and generated a dataset (Supplementary Data 1).

Since our data sampling is not very robust and refers to a single municipality, instead of a Gaussian approach, we adopted in this work the relative frequency, in which this frequency was calculated through the equation:

Where Freq is relative frequency, AdmisMI are relative to cases of admissions due to myocardial infarctions (MI) and magCondition are magnetic condition days (quiet, moderate, or disturbed).

We used free software GNU Octave 8.2.0.

We use K-Means, an unsupervised clustering method using Weka 3.8.6 that is an open-source machine learning software issued under the GNU General Public License40,41. We chose to adopt 4 clusterings and 4 attributes: geomagnetic condition (discrete: quiet, moderate, or disturbed), Kp sum (numeric), sex(discrete: female or male) and age (numeric) and the centroids of the attributes were calculated using Euclidean distance.

Results

In our analyses, we divided the results into two subsections: the first examined admissions in relation to geomagnetically quiet, moderate, and disturbed days, as well as sex. In the second subsection, we included the analysis by age groups.

Admissions and occurrences in relation to quiet, moderate, disturbed days and sex

In this section, we analyze the daily geomagnetic conditions classified by Kp as quiet, moderate, and disturbed days. Additionally, we examine the occurrences of myocardial infarctions (Table 1) in relation to the patients’ sex and age.

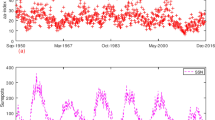

Analyzing the occurrence numbers of MI by sex, there were 871 admissions of males and 469 admissions of females. Among these admissions, 96 men and 79 women died, while 663 men and 342 women were discharged (refer to Fig. 2). What is particularly noteworthy in these numbers is the significantly higher proportion of female deaths in comparison to the number of admissions. This proportion is almost equal to the number of male deaths, even though were far more male admissions (871 against 469).

During the period of our study (Jan, 1 1998–May, 31 2005), occurred according to the criteria outlined in our Method (Supplementary Table S1): there were 2012 geomagnetically quiet days with 1000 admissions, 449 geomagnetically moderate days with 220 admissions, and 213 geomagnetically disturbed days with 120 admissions (Supplementary Table S1).

There were nearly twice as many admissions for men (871) compared to women (469), which corresponds to 1.857 times higher (Fig. 2). Under quiet conditions, this proportion is somewhat sustained (665 men and 335 women, 1.98 times higher) (Fig. 3a). However, this proportion diminishes during moderate conditions (140 men and 80 women, 1.75 times higher). In disturbed conditions, this proportionality decreases more sharply (66 men and 54 women, 1.22 times higher) (Supplementary Table S1) (Fig. 3a).

Regarding fatalities, during quiet conditions, there were 73 deaths among men and 58 deaths among women. In moderate conditions, the numbers were 14 deaths among men and 7 deaths among women. In disturbed conditions, the mortality rate increased, resulting in 9 deaths among men and 14 deaths among women (Supplementary Table S2) (Fig. 3b).

Classification of admissions for myocardial infarction (MI) by geomagnetic condition and by sex

In the age group (≤30), the admissions numbered 14 for males and 6 for females during quiet geomagnetic conditions, 4 for males and 3 for females during moderate conditions, and 3 for males and 1 for females during disturbed conditions (Fig. 4a).In the age group (>30 & ≤60), there were 364 admissions for males and 145 admissions for females during quiet geomagnetic conditions, 77 admissions for males and 38 admissions for females during moderate geomagnetic conditions, and 36 for males and 24 for females during strongly disturbed geomagnetic conditions. In the final age group (>60), there were 287 admissions for males and 184 admissions for females during quiet geomagnetic conditions, 59 admissions for males and 39 admissions for females during moderate geomagnetic conditions, and 27 admissions for males and 29 admissions for females during strongly disturbed geomagnetic conditions (see Supplementary Table S1) (refer to Fig. 4a).

Absolute count (a) and relative frequency (b) of hospital admissions for myocardial infarction (MI) on days classified as geomagnetically quiet, moderate, and disturbed, stratified by sex (male and female) and age group (≤30 years, >30 and ≤60 years, >60 years). Blue bars indicate geomagnetically quiet days, green bars moderate geomagnetic activity days, and red bars geomagnetically disturbed days. Panel (a) refers to the total admission count (n = 1340), while panel (b) displays the daily admission proportion (%).

In Fig. 4b, we present the calculations of MI occurrences based on quiet, moderate, or disturbed days (expressed as relative frequency) (Table 11). We observed that within the age range <30, males exhibited a higher occurrence rate during disturbed geomagnetic conditions. In the other age group (>30 & ≤60), for females, the occurrence rate (11.2%) was markedly higher under disturbed conditions compared to the rate (7.1%) under quiet conditions. In the age group >60, females also displayed a higher rate (13.5%) under disturbed conditions than the rate (9%) under quiet conditions. These results suggest a heightened susceptibility of women to increased geomagnetic activity (Supplementary Table S3).

When analyzing deaths resulting from myocardial infarction, within the age group (age ≤30), only one death was recorded among males under disturbed geomagnetic conditions (Supplementary Table S4) (Fig. 5a). In the age group (>30 & ≤60), there were 21 male and 12 female deaths under quiet conditions; 6 male and 2 female deaths under moderate conditions; and 3 male and 5 female deaths under disturbed conditions. In the last age group (>60), there were 52 male and 46 female under quiet conditions; 8 male and 5 female deaths under moderate conditions; and 5 male and 9 female deaths under disturbed conditions. Notably, the lower numbers align with the proportion of disturbed days (fewer than quiet and moderate days). However, for females, it remains higher than those for males. In Fig. 5b, we show the calculations of death occurrences based on the number of quiet, moderate, or disturbed days (expressed as relative frequency). We observed that within the age group (≤30), the male sex had a higher rate compared to females under disturbed geomagnetic conditions, attributable to the single recorded death. In the intermediate age group (>30 & ≤60), for females, the rate was significantly elevated under disturbed conditions compared to the rate for quiet days. This contrast was not observed for the male sex. Within the last age group (>60), females also displayed a higher rate under disturbed condition in relation to the rate during quiet condition (Supplementary Table S4).

Absolute count (a) and daily relative frequency (b) of myocardial infarction (MI) deaths, stratified by sex (male and female) and age group (≤30 years, >30 and ≤60 years, >60 years), according to geomagnetic activity. Blue bars indicate geomagnetically quiet days, green bars represent moderate geomagnetic activity days, and red bars denote geomagnetically disturbed days. Panel (a) refers to the total death count (n = 175), while panel (b) displays the daily death proportion (%) for each geomagnetic condition.

K-means classification

In the use of K-Means, when we suggested 4 groups, the algorithm classified two groups as quiet geomagnetic conditions, one group as moderate conditions and one group as disturbed geomagnetic condition (Table 3). The highlight was Cluster 3 in which in the disturbed magnetic condition the algorithm classified the predominance of the female sex, with the centroid for age being 65.4, the centroid of the sum of the Kp index was 38 and there were 114 occurrences of myocardial infarctions (MI). The other groups were: cluster 1, quiet geomagnetic condition, with a predominance of females, age centroids were 61.5, centroids of the sum of Kp were 14.0, and there were 335 cases of MI; cluster 2, the centroid age was 55.5, the sum of Kp was 28.7, the predominance of the male sex, and the geomagnetic condition was moderate; and cluster 4, with an age centroid of 58.3, the sum of Kp was 14.2, the predominant sex condition was male and the geomagnetic condition was quiet, and there were 226 cases of MI.

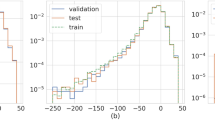

Thus, in Fig. 6, in the x Kp sum plot cluster, we can see that cluster 3 shows the values of the sums of the Kp index in a higher range and there is a predominance of cases of women (x in red), there are some points in red in which we could assume to be classified in cluster 1 because the Kp values are below 28.5, However, for these cases, the age attribute also influenced this classification. In cluster 1, the classification was only sex female (x in red) under quiet conditions and the sum of Kp did not exceed the value of 28.6; in cluster 2 there are the two sexes male and female (blue and red), although the predominance is male (in blue) and the geomagnetic conditions are of the moderate type because the Kp is in a range between 20 and 38 (above clusters 1 and 4, and below cluster 3). And in cluster 4, there is a classification only for male in magnetic conditions of the quiet type, and the Kp does not exceed the value of 28.5.

Each point represents a myocardial infarction (MI) hospitalization case, marked in red for females and blue for males. Cluster 1: Exclusively composed of females under quiet geomagnetic conditions. Cluster 2: Male predominance under moderate geomagnetic activity, with both sexes present. Cluster 3: Higher geomagnetic activity intensity (disturbed) with female predominance. Cluster 4: Exclusively composed of males under quiet geomagnetic conditions. The overlapping Kp ranges between some clusters demonstrate the influence of additional variables (such as age) in cluster formation.

Discussion

In relation to what we observed, in which the number of admissions of men is almost double that of women, and yet, the numbers of mortalities are nearly equal between men and women (Fig. 2), this finding presented in our manuscript is not novel and has been previously documented in other studies42,43,44,45. Some of the attributed causes include an increase in women’s risks associated with comorbidities with advancing age, a decrease in antioxidant metabolites, and a more pronounced worsening of women’s cardiac autonomic function compared to men42,43,44,45. It is also observed that women experience more atypical symptoms preceding MI events than men42,43,44,45. What our study added to these findings was that under geomagnetically disturbed conditions, there was an increase in admissions and deaths (both) due to myocardial infarction (MI). This increase was clearly observed in correlation with the number of geomagnetically disturbed days, as calculated through relative frequency rates. Additionally, the results suggest a marked influence of geomagnetic activities on the female sex within the age groups (>30 & ≤60). The influence was even more pronounced in relation to fatalities, where the occurrence rates linked to the number of disturbed days were significantly higher. The influence of GMDs on the female sex in the other age group (>60) was also readily apparent. Our studies indicated that magnetic activity might act as a trigger for the deflagration of myocardial infarction in women.

Since the admissions of men for MI are much higher than those of women, almost double, as mentioned in Section “Participants” (Fig. 2) (871 men and 469 women), and this ratio is approximately maintained for quiet days (665 men and 335 women) (Fig. 3a), this result suggests that since there is no change in the geomagnetic field from quiet to disturbed conditions, this proportionality does not change, which may be evidence of women’s susceptibility to geomagnetic conditions (Fig. 3a, b).

It is noteworthy to highlight that the results presented in this study are not conclusive and, therefore, the intention is not to incite alarm within the population, particularly among females. Rather, these findings represent an empirical result of hypothetical significance that should not be disregarded within any technical-scientific context. There are some noteworthy limitations to consider. Firstly, this study is an environmental observational investigation carried out in a single city, using a relatively modest sample size. Moreover, the hypothesis raised in this study requires a more extensive collection of data and corresponding statistical and phenomenological evidence. Secondly, the analysis of the dynamics of electrochemical waves in cardiac tissue continues to rely on more advanced37,46,47 instruments and models for accurate assessment. It is important to emphasize that this current study, upon bolstering with new systematically acquired data samples and enhanced analyses and models, holds the potential to yield fresh insights into its foundational hypotheses. It also stands to contribute directly to novel therapeutic strategies aimed at the prevention, alleviation, and management of the cause-and-effect relationships that might instigate induced cardiac pathological phenomena.

In any case, we found evidence of women’s susceptibility in disturbed geomagnetic conditions. The data show that although the number of MI cases in women is lower, in geomagnetic conditions they occur in greater proportion or even in absolute numbers.

Data availability

The raw numbers for the Kp index daily calculation (Kyoto data/Helmholtz dataset) are in the Supplementary Data 238. The raw numbers for the calculations from combining data on myocardial infarctions and the Kp index (Weka format dataset) are in the Supplementary Data 1,2,3, and 437. The source data for Fig. 2 is in Supplementary Data 1; the source data for Figs. 3a, b, 4a, b are in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2; and the source data for Fig. 5 is in Supplementary Data 3. Health data in Brazil has been made available to Brazilian citizens on the website of the Ministry of Health-Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System (DATASUS)48.

Code availability

Octave 10.1.0 software for data classification available49.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ultraviolet-radiation (2023). Acessed May, 16 2023.

Gonzalez, W. D. et al. Magnetic cloud field intensities and solar wind velocities. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 963–966 (1998).

Rezende, L. F. C., Paula, E. R., Batista, I. S., Kantor, I. J. & Muella, M. T. A. H. Study of ionospheric irregularities during intense magnetic storms. Revista Brasileira de Geofísica, 25, 151–158 (2007).

Lakhina, G. S. & Tsurutani, B. T. Geomagnetic storms: historical perspective to modern view. Geosci. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40562-016-0037-4 (2016).

Baker, D. N. & Kanekal, S. G. Solar cycle changes, geomagnetic variations, and energetic particle properties in the inner magnetosphere. J. Atmos. Sol. Terrestrial Phys. 70, 195–206 (2008).

Rigozo, N. R., Nordemann, D. J. R., Ether, E., Zanandrea, A. & Gonzalez, W. D. Solar Variability Effects Studied By Tree-Ring Data Wavelet Analysis. Adv. Space Res. 29, 1985–1988 (2002).

Uusitalo, J. et al. Solar superstorm of AD 774 recorded subannually by Arctic tree rings. Nat. Commun. 9, 3495 (2018).

Brehm, N. et al. Eleven-year solar cycles over the last millennium revealed by radiocarbon in tree rings. Nat. Geosci. 14, 10–15 (2021). 2021.

Basu, S., Groves, K. M., Basu, S. & Sultan, P. J. Specification and forecasting of scintillations in communication/navigation links: Current status and future plans, J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 64, 1745–1754 (2002).

De Paula, E. R. et al Characteristics of the ionospheric irregularities over Brazilian longitudinal sector. Indian J. Radio Space Phys. 36, 268–277, (2007).

Muella, M. T. A. H., de Paula, E. R., Kantor, I. J., Rezende, L. F. C. & Smorigo, P. F. Occurrence and zonal drifts of small-scale ionospheric irregularities over an equatorial station during solar maximum - Magnetic quiet and disturbed conditions. Adv. Space Res. 43, 1957–1973 (2009).

Rezende, L. F. C., de Paula, E. R., Kantor, I. J. & Kintner, P. M. Mapping and Survey of Plasma Bubbles over Brazilian Territory. J. Navigation 60, 69–81 (2007).

Chizhevskii, A. L. The factor facilitating occurrence and spreading psychosis. Rus. NemetskijZhurnal 9, 479–518 (1928).

Chizhevskii, A. L. The Earthly Echo of Solar Storms (Mysl’, Moscow, 1973).

Vernadsky, V. I. Biosphere (Leningrad: Nauchno-TekhnicheskoeIzdatel’stvo, 1926).

Vernadsky, V. I. Selected works. Izdatel’stvoAcademiiNauk SSSR, vol. 5 (Moscow, 1960).

Borodin, A. S., Tuzhilkin, D. A., Gudina, M. V. & Vladimirsky, B. M. Phenomenological features of mortality and morbidity dynamics in Tomsk versus heliogeophysical activity //. Izvestiya, Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 51, 792–805 (2015).

Novikova, K. F. The effect of solar activity on the development of myocardial infarction and mortality resulting therefrom. Kardiologıa 4, 109 (1968).

Kolodchencko, V. P. The number of myocardial infarctions in Kiev and geomagnetic perturbations (Solnechni Danni, 1969).

Malin, S. R. C. & Srivastava, B. J. Correlation between heart attacks and magnetic activity. Nature 277, 22 (1979).

Knox, E. G., Armstrong, E., Lancashire, R., Wall, M. & Hayne, R. Heart attacks and geomagnetic activity. Nature 281, 564–565 (1979).

Dimitrova, S. et al. Possible influence of solar extreme events and related geomagnetic disturbances on human cardio-vascular state: Results of collaborative Bulgarian–Azerbaijani studies. Adv. Space Res. 43, 641–648 (2009).

Mendoza, B. & de La Peña, S. S. Solar activity and human health at middle and low geomagnetic latitudes in Central America. Adv. Space Res. 46, 449–459 (2010).

Zilli Vieira, C. L. et al. Geomagnetic disturbances driven by solar activity enhance total and cardiovascular mortality risk in 263 U.S. cities. Environ. Health 18, 83 (2019).

Kolesnik, S. A. Mathematical modeling of Schumann resonances//Collection of reports of the XXVIII All-Russian Open Scientific Conference. In: Electronic data (eds, Lukin, D. S., Ivanov, D. V., Ryabova, N. V.) 309–312 (Yoshkar-Ola, Volga State Technological University, 2023). https://science.volgatech.net/upload/documents/science/RRW2023.pdf.

Kirkby, J. Cosmic rays and climate. Surv. Geophys. 28, 333–375 (2007).

Breus, T. K., Ozheredova, V. A., Syutkinab, E. V., & Rogozac, A. N. Some aspects of the biological effects of space weather. J. Atmos. Sol. Terrestrial Phys. 70, 436–441 (2008).

Close, J. 2012. Are stress responses to geomagnetic storms mediated by the cryptochrome compass system? Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 2081–2090 (2012).

Polk, C. Schumann Resonances. CRC Handb. Atmos. 1, 111–177 (1982).

Malmivuo, J. & Plonsey, R. Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and applications of bioelectric and biomagnetic fields (Oxford University Press, 1995).

Cherry, N. Schumann Resonances, a plausible biophysical mechanism for the human health effects of Solar. Nat. Hazards 26, 279–331 (2002).

Adey, W. R. Frequency and energy windows under the influence of weak electromagnetic fields on living tissue //. TIIER 68, 140–147 (1980).

Adey, W. R. Biological Effects of Electromagnetic Fields. J. Cell. Biochem. 51, 410–416 (1993).

Carrubba, S., Frilot, C. II, Chesson, A. L. Jr. & Marino, A. A. Evidence of a nonlinear human magnetic sense. Neuroscience 144, 356–367 (2007).

Henshaw, I., Fransson, T., Jakobsson, S., Jenni-Eiermann, S. & Kullberg, C. Information from the geomagnetic field triggers a reduced adrenocortical response in a migratory bird. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 2902–2907 (2009).

Lara, A. et al. Short-period fluctuations in coronal mass ejection activity during solar cycle 23. Sol. Phys. 248, 155–166 (2008).

Datasus data. Available at Zenodo provider, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14675326 (2025).

Kyoto Kp index. Available: https://wdc.kugi.kyoto-u.ac.jp/kp/index.html (2023).

GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences - Helmholtz Centre Potsdam. Available: https://www.gfz-potsdam.de/en/kp-index/ (2023).

D. Arthur, S. Vassilvitskii: k-means++: the advantages of carefull seeding. In: Proceedings of the eighteenth annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete algorithms, 1027–1035 (2007).

Frank, E., Hall, M. A. & Witten, I. H. The WEKA Workbench. Online appendix for “data mining: practical machine learning tools and techniques”, 4rth ed, 2016. (Morgan Kaufmann, 2016).

Schulte, K. J. & Mayrovitz, H. N. Myocardial Infarction Signs and Symptoms: Females vs. Males. Cureus 15, e37522 (2023).

Crea, F., Battipaglia, I. & Andreotti, F. Sex differences in mechanisms, presentation and management of ischaemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis 241, 157–168 (2015).

van Oosterhout, R. E. M. et al. Sex Differences in Symptom Presentation in Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e014733 (2020).

Millett, E. R. C., Peters, S. A. E. & Woodward, M. Sex differences in risk factors for myocardial infarction: cohortstudy of UK Biobank participants. BMJ 363, k4247 (2018).

Winfree, A. T. When time breaks down: the three-dimensional dynamics of electrochemical waves and cardiac arrhythmias. Paperback – International Edition. https://www.amazon.com/When-Time-Breaks-Down-Three-Dimensional/dp/0691024022 (1987).

Jæger, K. H., Edwards, A. G., Giles, W. R. & Tveito, A. From millimeters to micrometers; re-introducing myocytes in models of cardiac electrophysiology. Front. Physiol. 12, 763584 (2021).

Ministry of Health-Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System (DATASUS). https://datasus.saude.gov.br/ (2025).

Software for data treatment. Available in https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14675306.

Acknowledgements

City Hall of São José dos Campos, Secretary of Health for preparation and data supply. We thank the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation and the Brazilian Space Agency. L.F.C.R. and J.P.H.B.O thank the financial support received by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) – Project: 400077/2022-1 and process number 314209/2025-5. M.T.H.A.M. and E.R.P. thank the financial support received by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) under processes numbers 314261/2020-6 and 302531/2019-0.Luiz Fernando Ferraz da Silva (University of São Paulo) for his help in formatting the documents in the final review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F.C.R. conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing, edition. E.R.P. conceptualization, methodology, writing, revision, funding acquisition. M.T.A.H.M. data curation, methodology, writing, revision. S.G.D. methodology, validation, writing. R.R.R. writing, revision, validation. P.H.N.S. writing, revision. J.P.H.B.O. revision, validation, writing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Alexander Borodin, Carolina L Zilli Vieira for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezende, L.F.C., De Paula, E.R., Muella, M.T.A.H. et al. Influence of geomagnetic disturbances on myocardial infarctions in women and men from Brazil. Commun Med 5, 247 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00887-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00887-7