Abstract

Background

Influenza virus and pneumococcal infections are associated with serious health risks resulting from complications. Vaccinations are an effective method of preventing them. Pharmacists can play an essential role in promoting and administering vaccines. High vaccination rates among pharmacists could increase their credibility as vaccination advocates. The review aims to discuss the influenza and pneumococcal vaccination coverage among pharmacists and factors influencing the willingness to vaccinate.

Methods

The systematic review was performed according to PRISMA guidelines across three medical databases: Medline (via PubMed), Embase (via OVID), and Cochrane Library. The quality assessment of the study was carried out using The Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. A meta-analysis was also conducted to estimate pharmacists’ overall influenza vaccination coverage, incorporating an analysis of vaccination trends before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

The meta-analysis of 6194 observations and 3585 events reveals an overall influenza vaccination coverage among pharmacists of 50.78% under a random effects model, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 36.20% to 65.22%. Only one retrieved study analyzes pharmacists’ vaccination coverage against pneumococci. According to the findings, 20.8% of the participants in the study were vaccinated against pneumococci.

Conclusions

The current influenza vaccination rate among pharmacists is moderate, and concerted efforts are needed to increase it. This involves implementing continuous education, beginning at the pharmacy degree stage.

Plain language summary

Immunization is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases. We used uptake of immunization against influenza and pneumococcal among pharmacists to estimate the coverage within the profession and as a surrogate measure of their influence on the general public. We evaluated 18 studies, only one of which was on pneumococcus immunization. They find that influenza vaccination rates among pharmacists varied widely, from 7% to 95%, with an average of about 50.78%. They note that pharmacists often choose to vaccinate to protect their patients and families. However, some pharmacists are hesitant due to doubts about vaccine effectiveness and safety. The study suggests that increasing education about vaccines could improve vaccination rates among pharmacists. This research highlights the need for better strategies to encourage pharmacists to get vaccinated, which could help increase overall vaccination rates in the community. Future efforts could focus on addressing misconceptions and improving access to vaccines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza and diseases caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (e.g., pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease) can result in serious health complications, particularly among older people, children, and individuals with weakened immune systems1,2,3. Epidemiological data suggests that the flu virus could be the cause of hundreds of millions of illnesses and around 100,000 deaths annually worldwide (with some sources suggesting the number could be even higher, exceeding 300,000 deaths)4,5,6. Streptococcus pneumoniae causes even more dangerous infections, resulting in the highest morbidity and mortality rates among lower respiratory tract infections. Based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, the estimated number of deaths caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced diseases in 2021 was approximately 550,0007.

Vaccination is the most effective strategy for preventing influenza virus and pneumococcal infections. In the case of influenza, it is recommended for all people over 6 months of age who have no contraindications to vaccination8,9,10. The pneumococcal vaccine is recommended for children (until the age of 5), individuals over 65, and those at risk of experiencing a more severe infection, such as those with chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus11,12,13. The guidelines we have cited were based on literature reviews and have been published by internationally recognized institutions from the USA, Canada, and Australia, including the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It should be emphasized that pneumococcal vaccination strategies can vary between countries, and this can be influenced by aspects such as the availability and price of vaccines, local conditions (prevalence of vaccine serotypes), and antimicrobial resistance patterns. In the case of implementing a vaccination program for older adults, local disease burden and cost-effectiveness considerations should also be taken into account. Also, it is worth quoting the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), indicating the need to implement vaccination programs for children first (covering as many people in this group as possible) and then consider implementing a vaccination program for older adults14.

Pharmacists can play an essential role in promoting and administering vaccines, including educating patients, particularly those who may not have access to other healthcare professionals. In several nations, pharmacists are authorized to administer vaccines, thus providing them with the necessary tools to combat contagious diseases15,16,17. Study results show that pharmacists’ involvement in education and vaccination results in higher patient immunization rates18,19. Furthermore, guidelines for increasing vaccine coverage emphasize the importance of permitting patients to be vaccinated in community pharmacies20,21.

High vaccination rates among pharmacists could increase their credibility as vaccination advocates. The vaccination rate indicates the professional group’s stance towards this preventive measure. Understanding the factors facilitating pharmacists’ uptake of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines could prove essential in increasing their involvement in vaccination programs and augmenting vaccination rates across the broader population.

The review aims to discuss the influenza and pneumococcal vaccination coverage among pharmacists and factors influencing the willingness to vaccinate. As part of our meta-analysis, we also considered the potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the willingness to be vaccinated against influenza.

The analysis of the two types of vaccinations we have indicated in one article is due to the conduct of a larger research project on knowledge, pharmacists’ attitudes toward influenza/pneumococcal vaccinations, and their willingness to offer these vaccinations to their patients. We have already published one review regarding pharmacists’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of the discussed types of vaccinations22. We are also conducting a study in this area among Polish pharmacists. In order to maintain thematic consistency throughout the series, we decided to include pneumococcal vaccination in this article in addition to influenza vaccination. At the same time, it should be pointed out that pneumococcal vaccinations are not routinely recommended to medical personnel, including pharmacists23. Therefore, it was anticipated that few studies would address the issue of the percentage of pharmacists vaccinated against pneumococci.

A total of 18 studies met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review (17 were included in the meta-analysis on the influenza vaccination rate among pharmacists). Only one study concerned the vaccination rate against pneumococci. According to the results of the meta-analysis, influenza vaccination coverage among pharmacists is 50.78% [95% CI: 36.20%; 65.22%]. Factors contributing to the lack of vaccination include, among others, beliefs about the lack of risk of influenza exposure, not belonging to a high-risk group for influenza complications, and misconceptions about the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine. Considering these results, it should be stated that the influenza vaccination rate among pharmacists is moderate, and efforts should be made to increase it.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search was performed based on the PRISMA guidelines24. The search was based on a pre-developed protocol registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024566982)25. On 17 February 2024, the following databases were searched: Medline (via PubMed), Embase (via Ovid), and The Cochrane Library. Search strategies are available in the Supplementary Data 1. The bibliography of the studies included in the analysis was also searched. Articles published at any time and in any country were considered.

Our study is entirely based on results from previously published research. Therefore, it does not include any data that would require approval by an ethics committee.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Publications in English were included in the analysis to present the results of research from around the world regarding the uptake of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines among pharmacists. The focus was on peer-reviewed publications from scientific journals where quantitative data were available so that objective research conclusions could be drawn about vaccination rates and factors that influence vaccination uptake by pharmacists.

Publications that contained only qualitative data (e.g., studies conducted using only focus groups) were excluded. Conference abstracts (due to the lack of comprehensive scientific verification of these data), letters to editors, review papers, and publications not published in scientific journals (including, for example, data from local registers) were also excluded. Publications that did not include any pharmacists were not considered.

Study selection

Two authors working independently selected the study (J.Ś. and K.W.). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, with input from the third author (M.W.). The first stage involved deleting any duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the publications were then analyzed, leading to the extraction of publications for in-depth text analysis.

Data extraction and statistical analysis

The following elements were extracted for each of the studies found: the first author of the study, the year of publication, the time interval covered, the population studied, the methods used to conduct the study (including a description of the questionnaire used and distribution methods), the number of people who participated in the study in relation to the number of people vaccinated, and factors influencing the willingness to be vaccinated for influenza and pneumococci.

In terms of the primary analyses, we only included pharmacists. Some publications also analyzed results for other health professionals, including pharmacy technicians. Data on these individuals were isolated, limited to crucial information on vaccine uptake (Supplementary Data 2). We decided to present this data to enable a quick and direct comparison of pharmacists’ results with those of other medical professions.

A meta-analysis was also conducted to estimate pharmacists’ overall influenza vaccination coverage, incorporating an analysis of vaccination trends before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the present meta-analysis, the threshold for statistical significance was set at an alpha level of α = 0.05. A Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) was employed to synthesize proportion data from selected studies, following the methodologies outlined by Harrer 202126 and Stijnen 201027. This statistical approach utilized the logit transformation to calculate pooled proportions28,29. The results were back-transformed to proportions before presentation to facilitate the interpretation of findings in their natural units.

In our analysis, confidence intervals for the outcomes of individual studies were derived using the normal approximation technique based on the summary measure described in Agresti’s 1998 study30. Variance and standard deviation of the actual effect sizes across the studies were quantified through the computation of Tau-squared (τ²) and tau (τ), respectively, employing the maximum likelihood estimator method31. To assess the extent of genuine heterogeneity as opposed to mere chance, the I-squared (I²) statistic was utilized, following the approach of Higgins 200232. This analysis was complemented by the H statistic, which measures the degree of heterogeneity among the studies, with values exceeding one indicating significant variability.

Analytical methods, including the Wald test and the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT), were used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the collected data.

A test for subgroup differences was performed using a Q-test to determine if there were statistically significant differences in vaccination rates between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods33.

The results were visualized using a forest plot, which aggregates the outcomes of individual studies.

Several methodologies were employed to evaluate the potential publication bias within the meta-analysis. A funnel plot served as the initial tool for visual examination, facilitating the detection of asymmetries indicative of bias. This graphical approach is instrumental for the preliminary identification of any uneven distribution of study data that may suggest publication bias.

Egger’s test was used to conduct a further quantitative assessment of funnel plot asymmetry. This test involves a regression analysis of the standardized effect estimates against their precision, defined as the inverse of the standard error34. In addition, Peters’ test was applied to investigate the association between effect estimates and their variance, providing an additional layer of analysis for detecting publication bias35.

Analyses were conducted using the R Statistical language (version 4.3.1) on Windows 10 pro 64 bit (build 19045), using the packages meta (version 6.5.0), report (version 0.5.7), and dplyr (version 1.1.3)36,37,38,39.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies40 was used to assess the quality and risk of bias (RoB) of included studies (Supplementary Table 1). The tool was developed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). It comprises 14 questions relating, among other things, to the detail and validity of the description in terms of population and outcomes. Each question could be answered in one of the following ways: yes, no, cannot be determined, not applicable, not reported. After each study, assessors can provide an overall quality rating. The study could be rated as good, fair, or poor. A rating of “good” indicates a low RoB and confirms the validity of the results. If the rating is “fair,” there are some shortcomings which, however, do not significantly affect the results obtained. Conversely, if the rating is “poor”, it indicates the presence of a significant RoB, which may affect the result’s credibility.

Two authors working independently performed the assessment (M.W. and K.W.). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, with the involvement of a third independent author (J.S.).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Search results

Only 18 of the 1209 studies identified through a systematic search met the criteria for inclusion in the analysis. The stages of study selection are shown in Fig. 1. The list of publications included and excluded from the review based on full-text analysis is provided in the Supplementary Data 3.

All the studies identified were cross-sectional studies. In Supplementary Data 4, the general characteristics of the identified studies are presented.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

In the quality assessment and RoB, a rating of “good” was assigned to 5 studies: Morgel 202341, Costantino 202242, Sallam 202243, Black 201544, and MacDougall 201545. A “fair” rating was given to 10 studies: Chau 202446, Lang 202347, Langer 202348, Ozdemir 202249, Cuschieri 202150, López-Sánchez 202151, Awadalla 202052, Gianfredi 201853, Toledo 201754, Ruiz 201055. A rating of “poor” was assigned to 3 studies: Bartolo 202256, Pullagura 202057, and Ziegler 201658.

Since all the publications included in our study were cross-sectional, specific questions in the utilized tool were pre-answered (questions 6 and 7 with a “no” response, and questions 8, 12, and 13 with a ‘not applicable’ response). These questions were not considered when determining the actual risk of error. If we adopt highly rigorous assessment criteria, including the questions mentioned above, the evaluation of all studies would yield a “poor” rating. However, given the characteristics of the intervention (vaccination uptake), we felt that the other questions would be critical to the evaluation.

When analyzing the detailed findings, it is essential to highlight that all studies had a well-defined research objective (item 1) and employed appropriate statistical techniques (item 14). A similar situation occurred with item 9, which pertained to the methods used for collecting data. Given that most countries do not have universal vaccination registers for specific professional groups, a questionnaire survey is the most efficient means of gathering data. All studies included employed this particular methodology, clearly presenting the question pertaining to the respondent’s vaccination status. At the same time, a few studies raised minor concerns about the tool utilized, the absence of information regarding its creation, and the reliability verification process (item 11). For this reason, we could not explicitly assess the validity of the survey instrument in the following studies: Lang 202347, Bartolo 202256, López-Sánchez 202151, Ruiz 201055, which may translate into the reliability of the obtained results.

The vast majority of studies accurately described the population included in the analysis (item 2), including demographics, location, and time of the conducted study. However, two studies raised significant concerns in this regard. The article by Bartolo in 202256 lacks details on participant recruitment and raises concerns about the questionnaire’s distribution method through social media. In contrast, the Pullagura 2020 publication57 did not present the study’s time frame.

The surveys exhibited notable disparities in item 3, which measured the participation rate of eligible individuals, and item 5, which justified the sample size. Regarding item 3, only a few studies have reached the 50% threshold of the indicator value (Costantino 202242, Sallam 202243, Awadalla 202052, Black 201544). In several studies, the identification of this issue was hindered by the absence of response rate calculation or information regarding the total size of the eligible population (Chau 202446, Morgel 202341, MacDougall 201545). The remaining publications did not achieve the projected indicator value. In contrast, for item 5, most studies did not provide sufficient sample size justification (Langer 202348, Morgel 202341, Bartolo 202256, Cuschieri 202150, Awadalla 202052, Pullagura 202057, Gianfredi 201853, Toledo 201754, Ziegler 201658, Black 201544, Ruiz 201055).

Several studies conducted two measurements or compared data to those acquired in previous epidemic seasons (Morgel 202341, Costantino 202242, Black 201544).

After considering all comments and limitations, it was determined that all studies meeting the review’s inclusion criteria would be included in the analysis. Publications that were given a “poor” rating based on our evaluation despite a notable risk of error may be considered for analysis, as no crucial factors invalidate the obtained results.

Detailed quality assessment results are presented in the Supplementary Table 2.

Vaccine uptake

The meta-analysis encompassed the results of 17 studies aimed at estimating the influenza vaccination coverage among pharmacists, predominantly in European countries (n = 9) but also in North America (n = 4) and Asia (n = 4) (Table 1).

The average sample size of the studies was 364 participants, ranging from 30 to 1450. The vaccination rates among pharmacists varied widely, ranging from 7% to 95%. The studies included in the meta-analysis were conducted over a period extending from 2008 to 2022. Considering this extensive temporal range, an additional analysis was performed to evaluate vaccination rates within distinct temporal subgroups: the pre-COVID-19 pandemic (2008–2019) and the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022). This stratified analysis was designed to provide insights into temporal shifts in vaccination behaviors potentially influenced by the pandemic. Where an analysis was conducted in a publication during two different epidemic seasons, only data from the most recent season were considered to avoid publication bias. An analysis was also conducted, comparing the vaccination levels based on continents (Europe, Asia, North America), work location (rural, urban), and gender.

The meta-analysis revealed an overall vaccination coverage among pharmacists of 50.78% under a random effects model, with a 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) ranging from 36.20% to 65.22% (Fig. 2). The considerable heterogeneity observed across studies is quantified by a high I² value of 98.0% and a tau² of τ² = 1.53, indicating substantial variability in vaccination rates that is not attributable to sampling error alone. The heterogeneity is further underscored by high values of H = 7.03 and significant p-values in tests for heterogeneity via the Wald (789.81, p < 0.001) and LRT (989.73, p < 0.001).

The results of the studies included in the meta-analysis, considering the number of individuals vaccinated against influenza (Events; n = 3585) and the total number of participants (Total; N = 6194). For each study, the proportion of vaccinated individuals is calculated, and the overall result is provided. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval (CI).

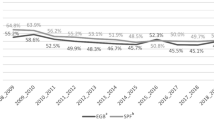

In the subgroup analysis, studies conducted pre-COVID-19 pandemic (2008–2019) showed a slightly higher vaccination uptake (52.73%) compared to those during the pandemic (2020–2022), which reported a rate of 48.59%. However, both subgroups continued to exhibit high heterogeneity with I² values of 98.7% for pre-pandemic and 94.1% for pandemic periods. The tau² values were notably higher in the pre-pandemic subgroup (τ² = 2.32) than during the pandemic (τ² = 0.47), suggesting that the variability among study results was more significant before the pandemic. The test for differences between the two subgroups (pre-pandemic vs. during the pandemic) yielded a Q-value = 0.09 with a p = 0.767, indicating no statistically significant difference in vaccination rates between these periods. Figure 3 presents a graphical data visualization featuring the pooled proportions and the proportions within subgroups, as depicted through a forest plot.

a Influenza vaccination coverage before the Covid-19 pandemic (up to 2019; N = 3382; n = 2002). b Influenza vaccination coverage during the Covid-19 pandemic (from 2020; N = 2812; n = 1583). For each study, the proportion of vaccinated individuals is calculated, and the overall result is provided. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval (CI).

In another subgroup analysis, it was examined whether there are differences in vaccination rates between continents (Supplementary Fig. 1). In Europe, the pooled proportion was 0.39 [95% CI: 0.25; 0.56] with considerable heterogeneity (τ² = 0.97, τ = 0.99, I² = 97.1%). Similarly, studies from Asia reported a proportion of 0.38 [95%CI: 0.27; 0.50] with even lower heterogeneity (τ² = 0.19, τ = 0.44, I² = 88.7%). In contrast, North American studies demonstrated a significantly higher vaccination rate, with a pooled proportion of 0.83 [95% CI: 0.74; 0.89) and moderate heterogeneity (τ² = 0.21, τ = 0.46, I² = 77.5%). The test for subgroup differences was highly significant (Q = 39.18, df = 2, p < 0.001), underscoring the variability in vaccination rates across continents (specifically between Asia, Europe vs. North America).

Considering the studies that distinguished the place of employment (n = 2), the pooled proportion in rural settings was slightly higher at 37.6% [95% CI: 22.6%; 55.4%; I² = 91.2%], whereas urban areas exhibited a similar vaccination rate of 35.1% [95% CI: 20.6%; 52.9%; I² = 97.7%]. Despite these numerical differences, statistical analysis did not reveal significant variation between rural and urban settings (Q = 0.04, df = 1, p = 0.836). The differences in vaccination rates based on gender were analyzed in 3 studies. Subgroup analysis revealed a pooled vaccination proportion of 32.97% [95% CI: 20.7%; 48.1%] among female pharmacists, with substantial heterogeneity (τ² = 0.2997, τ = 0.55, I² = 97.3%). Among male pharmacists, the pooled proportion was slightly higher at 38.56% [95%CI: 33.9%; 43.5%], with minimal heterogeneity (τ² = 0, τ = 0, I² = 7.9%). However, the test for subgroup differences did not indicate statistical significance (Q = 0.51, df = 1, p = 0.47). The detailed results are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2–3.

The funnel plot in Fig. 4 shows a concentration of study results at the apex of the funnel, primarily within a standard error (SE) range of 0 to 0.25. This clustering at lower SE values indicates a higher precision in most studies. The data points are symmetrically distributed, with minor discrepancies observed as the standard error increases, particularly beyond an SE of 0.3. These discrepancies, while noticeable, do not significantly deviate from the expected funnel shape, suggesting a relatively symmetric distribution across the analyzed studies.

The logit-transformed proportion estimates are within a range of −1.5 to 1.5, underscoring a balanced spread of effect sizes across the studies, regardless of their variance. This distribution pattern is typical in funnel plots where no substantial publication bias is present, as studies with high and low precision symmetrically scatter around the average effect size, diminishing concerns about selective reporting.

The linear regression analysis of funnel plot asymmetry, informed by the test results (t = −0.74, df = 15, p = 0.469), indicates no statistically significant evidence of publication bias in the study sample as per Egger’s test. A relatively high p value suggests that the intercept does not significantly deviate from zero, which typically points to the absence of bias in the meta-analysis.

Further examining the sample estimates, the calculated bias of −2.53, SE = 3.41 implies variability without a significant skew in the funnel plot. The intercept value of β0 = 0.55, SE = 0.39, reinforces the finding of no notable bias, as the confidence interval likely includes zero. In conclusion, there is no conclusive evidence of asymmetry in the funnel plot, suggesting an unbiased distribution of the included studies regarding their effect sizes and variances. This outcome, however, is interpreted within the context of significant heterogeneity, which necessitates careful consideration of underlying study characteristics and contexts.

The linear regression test of funnel plot asymmetry, conducted using Peters’ method, presents a t-statistic of t = −1.09 with degrees of freedom df = 15, resulting in a p-value of p = 0.291. Similar to the Eggers test, this outcome also suggests that no statistically significant asymmetry is detected in the funnel plot, which implies an absence of publication bias within the analyzed studies. The intercept of β0 = 0.45 with a standard error of 0.2407 further supports this interpretation, as the confidence interval likely encompasses zero, indicating no significant deviation from symmetry.

Only one retrieved study analyzed pharmacists’ vaccination uptake rates against pneumococci. According to the results, 20.8% of the study population (83/400 pharmacists) were vaccinated. This was the lowest vaccination rate among the remaining health professions analyzed, with 26.7% of doctors (151 out of 565) and 30.2% of nurses (61 out of 202) being vaccinated45.

Factors influencing willingness to vaccinate

The retrieved studies analyzed factors associated with willingness to be vaccinated for influenza (Supplementary Data 5). The most common determinant of pharmacists’ willingness to be vaccinated was to protect patients, relatives, and family members from infection42,48,54,57. Also, the willingness to get vaccinated was influenced by having a good understanding of the vaccine, possessing a vaccination certificate, and acknowledging COVID-19 vaccination as the most effective way to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection42,49,58. In contrast, individuals’ reluctance to receive the influenza vaccine stemmed mainly from the belief that they were not susceptible to influenza infection or did not belong to a group prone to influenza-related complications42,48,53,55. The studies also revealed that pharmacists expressed concerns regarding the efficacy and safety of vaccination42,55,57. In one study, no obligation to receive vaccination was cited as the main reason for not receiving it42.

Discussion

Influenza has substantial consequences for those who contract it and for the healthcare system, causing absenteeism and presenteeism among healthcare personnel59,60,61. According to the results of some studies, the proportion of vaccinated people may reduce the disease burden among health professionals and patients62,63,64,65. However, most importantly, vaccination of medical personnel against influenza is primarily intended to protect their patients59,66.

Our study results indicate that the influenza vaccination rate among pharmacists is moderate. A remarkable difference in influenza vaccination rates was evident between the various studies, ranging from 7% to 95%. Based on the meta-analysis findings, the overall vaccination coverage among pharmacists was 50.78% [95% CI: 36.20; 65.22]. The absence of meta-analyses that include professionals from diverse health disciplines impeded the explicit comparison of results. Simultaneously, several studies we included in the analysis involved individuals from professions other than pharmacists. Several studies have consistently shown a marked difference in vaccination rates, with pharmacists lagging behind doctors41,43,45,46,47,52. Although there were additional slight variations between pharmacists and nurses, multiple studies demonstrated a disadvantage for pharmacists43,45,52.

At the same time, the results of the subgroup analysis indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic did not have a discernible impact on the influenza vaccination rates among pharmacists. The persistent high heterogeneity across studies suggests that factors other than the period (pre- or during COVID-19) may influence vaccination rates. These factors may include regional policies, individual perspectives on vaccine efficacy or safety, and the accessibility of vaccination services. Another factor could be the perception of the individual risk of acquiring an infection or vaccine recommendations of various countries, which in part differentiate between staff with and without close patient contact67. The lack of a significant difference in vaccination rates before and during the pandemic implies that the heightened awareness of infectious diseases brought about by COVID-19 did not translate into increased influenza vaccination rates among pharmacists. Nevertheless, it is crucial to exercise utmost caution when interpreting our findings, as regional flu epidemics, a common occurrence that can boost vaccination intentions, may have influenced flu vaccination rates. Additionally, it is important to consider local vaccination regulations, which may vary depending on the country.

Although no differences were found between gender, the location of the pharmacy (rural or urban area), and the level of vaccination per group, we cannot rule out the actual existence of such differences. The analysis was based on an extremely small number of studies (three for gender and two for workplace), with very few observations. This may lead to bias, so our results in this regard should be treated with caution. It is necessary to conduct further, more detailed research in the population of pharmacists.

It is essential to continue monitoring influenza vaccination trends among pharmacists and compare data from additional studies analyzing the pandemic period, which are still expected to be published regularly. This is particularly relevant given that studies examining vaccination rates among various health professions increased during the Covid-19 pandemic68,69. However, initial studies are also emerging that indicate the surge in flu vaccination may have been a temporary phenomenon. A study conducted in Spain demonstrated, as envisaged, a notable increase in vaccination rates (epidemic seasons 2020/21–67.9% of people vaccinated and 2021/22–65.5% of people vaccinated). Nonetheless, the vaccination rate decreased during the 2022/2023 epidemic season, with only 42.7% vaccinated individuals. This decline was even more pronounced compared to the pre-pandemic season of 2019/2020, when 51.9% of people were vaccinated70.

Insufficient knowledge and misconceptions about influenza vaccination are well-documented in the literature on barriers to healthcare personnel’s vaccine uptake. Common misconceptions often involve a perception of a low risk of disease contraction, an unsupported fear of influenza resulting from vaccine administration, doubts regarding product efficacy and safety, and concerns about potential side effects71. These aspects were additionally validated after examining the studies included in our analysis42,53,55,57.

Education seems to be an effective way to increase influenza vaccination rates among pharmacists. It is also very important to recommend vaccination to this group through national health management bodies. Reimbursement of the cost of the vaccine also seems important for increasing vaccination rates. Another far more radical solution would be to introduce mandatory vaccination for medical personnel, including pharmacists. This solution has been investigated in various countries (specifically in single healthcare facilities) for health professionals and has shown noteworthy effectiveness71. Simultaneously, it would probably cause a lot of anxiety and resentment among pharmacists. Therefore, the introduction of mandatory influenza vaccination should be considered only as a theoretical possibility. Hence, the foremost and indispensable step entails elevating vaccination knowledge amongst those presently engaged in the profession. A comprehensive education for pharmacy students is imperative to instill confidence in vaccination and its proper implementation once they commence their professional careers.

Only one study investigated the immunization of pharmacists against pneumococci. This is likely because medical professionals are not typically advised to get vaccinated, and other factors, such as being part of a high-risk group, play a crucial role in determining the recommendation for vaccination. Regarding adults, the key factors determining eligibility are age (typically 65 and above) and specific risk factors like cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus11,12,13. Unsurprisingly, researchers do not prioritize conducting studies on pneumococcal vaccination among pharmacists, given the likelihood of unreliable results and low vaccination rates. The analysis would be more understandable if limited to pharmacists susceptible to pneumococcal infections. Such a study would provide valuable insights into pharmacists’ attitudes towards vaccine uptake.

Our review is constrained by the minimal number of studies (17) that directly and accurately investigated influenza vaccination rates among pharmacists. A study was omitted from the meta-analysis due to the lack of information on the investigated timeframe57. Consequently, it was deemed inappropriate for inclusion in the subgroup analysis, and we have opted to exclude it exclusively from this section of the analysis. Our study exclusively considered published papers found in scientific journals. At the search stage, we encountered a few papers discussing vaccination among pharmacists without accurately depicting influenza vaccination rates. Therefore, we opted to exclude this type of study from the analysis as a precaution against the potential misinterpretation of the results. Our investigation excluded non-peer-reviewed papers, such as conference abstracts, national reports, and data from local registers. This could have potentially influenced the results obtained. However, this would not have considerable altered pharmacists’ perceptions of influenza vaccine uptake. One constraint we face when analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on influenza vaccination rates is the potential publication of further research on flu seasons during the same period as the pandemic. Subsequent results could influence the comparison between the pre-pandemic and during/post-pandemic periods. This is one reason we must be prudent about the results obtained in the subgroups. An important limitation of our study is the lack of a detailed analysis of the reasons for a given level of vaccination. In addition to pharmacists’ attitudes towards vaccinations, there may be many potential factors (including organizational ones) influencing the uptake of vaccines. Each country may have different legal regulations, as well as different approaches to financing vaccinations for pharmacists. Most of the publications we found only included information on the level of vaccination. Other analyzes were often conducted on a population that also included other medical professions. Therefore, on the basis of the research found, it was not possible to present more data and perform in-depth analyses. However, it is worth conducting research in this area to be able to assess, for example, the impact of local policies on vaccination levels.

To conclude, the influenza vaccination rate among pharmacists is moderate. Measures must be implemented to enhance it, with continuous education playing a pivotal role. The primary factors that exert the greatest influence on the reluctance to vaccinate include the belief that one is at no risk of exposure to the influenza virus infection or belonging to a risk group for post-influenza complications. Furthermore, misconceptions surrounding the effectiveness and safety of vaccination have contributed to pharmacists’ reluctance to vaccinate. Simultaneously, a higher level of knowledge greatly enhanced the inclination to receive the influenza vaccine.

Data availability

This review is based on data extracted from publicly available studies. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The characteristics of all included studies can be found in Supplementary Data 4. All statistical analyses have been performed based on data from Table 1.

References

Uyeki, T. M. High-risk groups for influenza complications. JAMA 324, 2334 (2020).

Buchy, P. & Badur, S. Who and when to vaccinate against influenza. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 93, 375–387 (2020).

Campling, J. et al. A review of evidence for pneumococcal vaccination in adults at increased risk of pneumococcal disease: risk group definitions and optimization of vaccination coverage in the United Kingdom. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 22, 785–800 (2023).

Uyeki, T. M. et al. Influenza. Lancet 400, 693–706 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Global burden of respiratory infections associated with seasonal influenza in children under 5 years in 2018: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e497–e510 (2020).

Iuliano, A. D. et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 391, 1285–1300 (2018).

Global Burden of Disease [Internet]. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (2024).

Grohskopf, L. A. et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2024-25 influenza season. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 73, 1–25 (2024).

Australian Immunisation Handbook – Influenza (flu) [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine-preventable-diseases/influenza-flu.

Influenza vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide [Internet]. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-10-influenza-vaccine.html.

Pneumococcal Vaccine Recommendations [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/hcp/vaccine-recommendations/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fvaccines%2Fvpd%2Fpneumo%2Fhcp%2Frecommendations.html.

Pneumococcal vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide [Internet]. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-16-pneumococcal-vaccine.html.

El-Beyrouty, C. et al. Pneumococcal vaccination-A literature review and practice guideline update. Pharmacotherapy 42, 724–740 (2022).

Summary of WHO Position Papers – Recommendations for Routine Immunization (updated: January 2025) [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/table1-summary-of-who-position-papers-recommendations-for-routine-immunization.

Ayenew, W. et al. Readiness of and barriers for community pharmacy professionals in providing and implementing vaccination services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24, 867 (2024).

Parracha, E. R. et al. Pharmacist’s role in influenza immunisation: a scoping review. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 54, 273–286 (2024).

Aldajani, F. N. & Aldosari, M. Pharmacist-led vaccination services in the Middle East. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 16, 171 (2023).

Le, L. M. et al. The impact of pharmacist involvement on immunization uptake and other outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 62, 1499–1513.e16 (2022).

Isenor, J. E. et al. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on vaccination rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 34, 5708–5723 (2016).

Vaccine uptake in the general population [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng218.

Flu vaccination: increasing uptake [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2018 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng103.

Waszkiewicz, M. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of pharmacists regarding vaccinations against influenza and pneumococci - a systematic review. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 21, 2489889 (2025).

Summary of WHO Position Papers – Immunization of Health Care Workers (updated: December 2024) [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/table-4-summary-of-who-position-papers-immunization-of-health-care-worker.

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Waszkiewicz, M. et al. Predictors of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines uptake among pharmacists [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=566982.

Harrer, M. et al. Doing Meta-Analysis With R: A Hands-On Guide. 1st ed. (Chapman & Hall,2021).

Stijnen, T., Hamza, T. H. & Ozdemir, P. Random effects meta-analysis of event outcome in the framework of the generalized linear mixed model with applications in sparse data. Stat. Med. 29, 3046–3067 (2010).

Warton, D. I. & Hui, F. K. The arcsine is asinine: the analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology 92, 3–10 (2011).

Schwarzer, G. et al. Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res. Synth. Methods 10, 476–483 (2019).

Agresti, A. & Coull, B. A. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am. Stat. 52, 119–126 (1998).

Viechtbauer, W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 30, 261–293 (2005).

Higgins, J. P. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558 (2002).

Borenstein, M. et al. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. (Wiley, 2021).

Egger, M. et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Peters, J. L. et al. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA 295, 676–680 (2006).

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G. & Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 22, 153–160 (2019).

Makowski, D. et al. Automated Results Reporting as a Practical Tool to Improve Reproducibility and Methodological Best Practices Adoption [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://easystats.github.io/report/.

Wickham, H. et al. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.3. [Internet] 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr.

The R Project for Statistical Computing [Internet] Vienna: R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org.

Study Quality Assessment Tools [Internet]. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

Morgel, O., Czock, A. & Lang, P. Peri-pandemic acceptance of influenza and COVID-19 vaccination by swiss healthcare workers in primary care 2020/21: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Public Health 68, 1605832 (2023).

Costantino, C. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and vaccination acceptance/hesitancy among the community pharmacists of Palermo’s province, Italy: from influenza to COVID-19. Vaccines 10, 475 (2022).

Sallam, M. et al. The role of psychological factors and vaccine conspiracy beliefs in influenza vaccine hesitancy and uptake among Jordanian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines 10, 1355 (2022).

Black, C. L. et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel- United States, 2014-15 influenza season. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 64, 993–999 (2015).

MacDougall, D. M. et al. The challenge of vaccinating adults: attitudes and beliefs of the Canadian public and healthcare providers. BMJ Open. 5, e009062 (2015).

Chau, N. M. et al. Association between influenza vaccine uptake and health awareness: a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study among medical students and healthcare workers in Northern Vietnam. Med. Sci. Monit. 30, e941406 (2024).

Lang, P. et al. Influenza vaccination behaviour of healthcare workers in Switzerland: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Public Health 68, 1605175 (2023).

Langer, R. & Thanner, M. Pharmacists’ attitudes toward influenza vaccination: does the COVID-19 pandemic make a difference?. Explor Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 9, 100235 (2023).

Ozdemir, N. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding vaccination among community pharmacists. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 23, e38 (2022).

Cuschieri, S. & Grech, V. A comparative assessment of attitudes and hesitancy for influenza vis-à-vis COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare students and professionals in Malta. Z. Gesund. Wiss. 30, 2441–2448 (2022).

López-Sánchez, I. & Domínguez, A. The perception and attitudes of pharmacists and their users towards vaccination and vaccine hesitancy. A cross sectional study. Vacunas 22, 138–149 (2021).

Awadalla, N. J. et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination among primary health care workers in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 16, 321–326 (2020).

Gianfredi, V. et al. PErCEIVE in Umbria”: evaluation of anti-influenza vaccination’s perception among Umbrian pharmacists. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 59, E14–E19 (2018).

Toledo, D. et al. Knowledge of and attitudes to influenza vaccination among community pharmacists in Catalonia (Spain). 2013-2014 season: a cross sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 756 (2017).

Ruiz, A. D. et al. Influenza vaccination rates among pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 50, 517–522 (2010).

Bartolo, N. S. et al. Influenza and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in pharmacists and pharmacy students. Malta Med. J. 34, 58–68 (2022).

Pullagura, G. R. et al. Exploring influenza vaccine hesitancy in community pharmacies: knowledge, attitudes and practices of community pharmacists in Ontario, Canada. Can. Pharm. J.153, 361–370 (2020).

Ziegler, B. et al. Protecting our patients by protecting ourselves: an analysis of the personal influenza immunization rate of Ontario community pharmacists. Can. Pharm. J. 149, 246–255 (2016).

Jędrzejek, M. J. & Mastalerz-Migas, A. Seasonal influenza vaccination of healthcare workers: a narrative review. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 35, 127–139 (2022).

Kuster, S. P. et al. Absenteeism and presenteeism in healthcare workers due to respiratory illness. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 42, 268–273 (2021).

Challener, D. W. et al. Healthcare personnel absenteeism, presenteeism, and staffing challenges during epidemics. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 42, 388–391 (2021).

Medina-Piñón, I. et al. Enhanced influenza vaccination among healthcare personnel prevents cases despite community burden. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 13, 165–168 (2019).

Gianino, M. M. et al. Estimation of sickness absenteeism among Italian healthcare workers during seasonal influenza epidemics. PLoS ONE 12, e0182510 (2017).

Zaffina, S. et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination and absenteeism in health-care workers in two subsequent influenza seasons (2016/17 and 2017/18) in an Italian pediatric hospital. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 18, 411–418 (2019).

Gianino, M. M. et al. Severe and moderate seasonal influenza epidemics among Italian healthcare workers: a comparison of the excess of absenteeism. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 15, 81–90 (2021).

Ahmed, F. et al. Effect of influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel on morbidity and mortality among patients: systematic review and grading of evidence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 50–57 (2014).

Survey report on national seasonal influenza vaccination recommendations and coverage rates in EU/EEA countries. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/survey-report-national-seasonal-influenza-vaccination-recommendations

Bianchi, F. P. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on flu vaccine uptake in healthcare workers in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 22, 777–784 (2023).

Schumacher, S. et al. Increasing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: analysis of an intensified on-site vaccination campaign during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infection 51, 1417–1429 (2023).

Guerrero-Soler, M. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza vaccination coverage of healthcare personnel in Alicante, Spain. Vaccines 12, 370 (2024).

Ledda, C. et al. Influenza immunization of healthcare personnel in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era: still a lot to do!. Vaccin. X. 15, 100402 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.W., K.W., J.Ś., and A.A.; Methodology: M.W., K.W., and J.Ś.; Formal Analysis: M.W. and A.A.; Investigation: J.Ś. and K.W.; Writing–Original Draft Preparation: M.W., K.W., J.Ś., and A.A.; Writing–Review & Editing: M.W., K.W., J.Ś., and A.A.; Supervision: A.A.; Project administration: M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Selim Badur and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waszkiewicz, M., Wnuk, K., Świtalski, J. et al. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines uptake among pharmacists: systematic review and meta-analysis. Commun Med 5, 258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00976-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00976-7