Abstract

Background

Existing literature on serum cholinesterase (ChE) in cancer prognosis have predominantly evaluated preoperative levels, ignoring serial ChE measurements during postoperative follow-up.

Methods

5925 patients undergoing curative resection for stage I-III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer (CRC), and gastric cancer (GC) were retrospectively included. Patients were divided into persistently normal, normalized, lowered and persistently low perioperative ChE patterns, as well as longitudinal ChE trajectories identified by the latent class growth mixed model (LCGMM). The associations of ChE dynamic changes with overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were evaluated.

Results

Postoperative ChE emerged as an independent prognostic factor, event after accounting for preoperative levels. Perioperative ChE stratification revealed divergent survival outcomes: the persistently normal group (82.5%) demonstrated 8.6% higher 5-year OS rate than the lowered group (73.9%), while the normalized group (73.3%) had 13.9% higher 5-year OS rate than the persistently low group (59.4%). LCGMM identified three distinct longitudinal trajectories: slow-rising (5-year OS rate: 79.7%; reference group), rising-decreasing (5-year OS rate: 64.8%; adjusted HR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.14 to 1.99) and decreasing-rising (5-year OS rate: 58.1%; adjusted HR: 2.33, 95% CI: 1.69 to 3.22). Consistent results were observed for RFS as well. Furthermore, stratified analyses confirmed statistically significant associations of ChE dynamic changes with prognosis across all histological subtypes.

Conclusions

A routine follow-up measurement of postoperative ChE was recommended to improve individualized management of cancer patients.

Plain language summary

Previous studies have revealed associations between levels of cholinesterase (ChE), an important protein in the blood, and prognosis in solid tumors. However, these studies were limited to pre-operative ChE assessments. The ability of blood levels of ChE to predict outcome after cancer surgeries occur remained unclear. Based on retrospective cohorts of non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and gastric cancer patients that were tracked over time, this study identified dynamic changes of ChE and evaluated their associations with cancer prognosis at different time points. Post-operative ChE (after surgery) could further stratify the prognosis of patients with normal and low preoperative ChE, providing additional insight into predicting outcome. Our study supports the idea of adding a routine follow-up measurement of post-operative blood ChE levels to improve individualized management of cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains a major public health problem worldwide1, and its poor prognosis brings substantial medical and economic burden2. Survival heterogeneity exists among cancer patients, and prognostic risk stratification is important in precision medicine3. Serum biomarkers, which are low-cost and available in clinical practice, are considered to be ideal indicators in prognosis monitoring4. So far, some well-established serum tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), have been recommended by the guidelines5,6. However, other serum biomarkers reported to be associated with tumor survival have not been widely applied in clinical cancer prognosis assessment.

Cholinesterase (ChE), a classic serum marker reflecting nutritional and immune status, has long been used in the past few decades as an aid in the diagnosis of a variety of diseases, such as chronic liver injury, inflammation, infection, and malnutrition7,8. In recent years, researchers have gradually begun to focus on the value of ChE in prognosis prediction8,9. Previous studies have revealed an association between serum ChE and survival in solid tumors9,10,11, however, these studies were limited to the preoperative ChE level, and the prognostic value of following-up postoperative ChE in human cancers has not been elucidated.

Different from preoperative status, dynamic changing patterns of serum ChE during postoperative follow-up reflect the evolution of patients’ disease and health status after curative resection, which may have independent prognostic value. For some identified tumor markers, previous studies have reported their dynamic changes during follow-up and found that patients with normalized postoperative markers have a better prognosis12,13,14. However, as a potential tumor marker, ChE dynamic changes have not been characterized in a longitudinal study, whose prognostic significance will provide new insights into the clinical application of ChE.

To clarify the prognostic value of following-up ChE in postoperative surveillance of human cancers, we identified perioperative ChE changing patterns and longitudinal ChE trajectories, and evaluated their associations with survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer (CRC), and gastric cancer (GC) patients.

Methods

Inclusion and ethics

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yunnan Cancer Hospital (KYLX2022055). The requirement for informed consent was formally waived under established guidelines for retrospective analyses. All personally identifiable information was removed from the dataset prior to analysis.

Study design

In this pooled pan-cancer analysis, a total of 5925 I-III stages patients across three cancer types who underwent radical resection without prior neoadjuvant therapy at Yunnan Cancer Hospital were retrospectively identified. The cohort comprised three subpopulations: 2267 NSCLC cases (November 2013–December 2018), 2844 CRC cases (February 2010–February 2019), and 814 GC cases (October 2011–December 2020). The overall study design is shown in Fig. 1. Patients with preoperative and postoperative ChE measurements were included in the perioperative ChE analysis, and patients with four or more measurements within 2 years after surgery were included in the longitudinal ChE trajectory analysis. The detailed study flow chart is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Data sources

Serum ChE was quantified via colorimetric analysis using a Roche cobas8000 c702 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Preoperative values were defined as measurements obtained ≤ 30 days before surgery. Postoperative values reflected the final assessment during the 90-day recovery phase, collected before initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. The normal reference range of serum ChE was 5000–12,000 U/L, and the threshold of low ChE was defined as the lower limit of the normal ChE range (5000 U/L). During follow-up, ChE was repeatedly measured with different intervals and times for participants.

Follow-up strategy

In this study, the follow-up was conducted in adherence to authoritative guidelines15,16,17,18, ending on October 31, 2022 (NSCLC), September 30, 2022 (CRC), and May 31, 2023 (GC). Primary endpoint overall survival (OS) was defined as the time elapsed from the date of surgery to either the date of death or the date of last follow-up—whichever occurred first. Secondary endpoint recurrence-free survival (RFS) was considered from surgery until confirmed recurrence (local or regional). Recurrence was confirmed via histology of a biopsy sample or positive imaging. Patients alive without recurrence at the last follow-up were censored.

Statistics and reproducibility

Nonlinear survival effects of ChE concentrations were assessed via restricted cubic spline (RCS) curves19. As a piecewise cubic polynomial, RCS can be applied to characterize the nonlinear relationship between continuous independent variables and survival outcomes within the framework of the Cox model. In this study, RCS with 3–10 knots were traversed and the optimal knot number was selected based on Akaike information criterion. The knots were located at equally spaced quantiles according to Harrell’s recommendation20.

Patients were categorized into two groups based on their preoperative and postoperative ChE levels: the normal group (ChE ≥ 5000 U/L) and the low group (ChE < 5000 U/L). By integrating both preoperative and postoperative ChE statuses, four distinct perioperative ChE patterns were further defined: the persistently normal group with consistently normal ChE levels across both the preoperative and postoperative periods, the normalized group with low preoperative ChE levels that returned to normal postoperatively, the lowered group with normal preoperative ChE levels that declined to the low range postoperatively, and the persistently low group with consistently low ChE levels.

In the analysis of longitudinal ChE trajectories, the latent class growth mixed model (LCGMM) was fitted using repeated ChE measurements collected during preoperative to 2 years after surgery21, with the longitudinal measurements of ChE expressed as the time functions. Histology type and its interaction with time functions were also included to account for the heterogeneity across cancers. Linear and quadratic models with 1–5 latent classes were traversed22, and the optimal model was determined according to the Bayesian information criterion, population proportion (> 3% for each class) and posterior probability (> 0.65 for each class).

For comparisons of characteristics across different ChE groups, continuous variables (presented as median [quartile]) were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis tests, and categorical variables (presented as number (percentage)) were analyzed using χ2 test. Kaplan–Meier method was applied to generate OS and RFS survival curve for each ChE group, and the log-rank test was performed to determine the overall difference. Cox proportional hazard models were used to investigate the associations between the ChE groups and outcomes, with three hierarchical models constructed: model 1 (unadjusted model); model 2 (basic adjusted model) with adjustment for age and sex; model 3 (fully adjusted model) with further adjustment for histology subtypes (NSCLC vs. CRC vs. GC), pathological T stage, pathological N stage, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Within postoperative ChE modeling frameworks, preoperative ChE was further adjusted in model 2 and model 3.

Subgroup analyses were performed in patients with normal and elevated preoperative CEA (cut off: 5 ng/ml) to show the additional prognostic value of ChE to CEA, as well as in patients with I, II and III stage cancer patients to show the stage-specific associations between ChE groups and OS. Besides, effect modification analyses were conducted across histology subtypes, dichotomized age cohorts (< 60/≥ 60 years), sex, pathological T stage, pathological N stage, and adjuvant chemotherapy, with tests for interaction through inclusion of multiplicative terms in Cox regression model.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

The combined pan-cancer cohort of 5925 patients included 3410 males (57.6%) with a median [interquartile range (IQR)] age of 59 [51–66] years, followed up for a median interval [IQR] of 60.2 [46.6, 80.1] months. The characteristics of pan-cancer patients across histology subtypes are outlined in Table 1. In the NSCLC cohort, the 5-year OS rate was 79.5% (95% Confidence Intervals (CI): 77.8–81.3%), while the 3-year RFS rate was 77.5% (75.8–79.3%). In the CRC cohort, corresponding rates were 82.9% (81.5–84.4%) for 5-year OS and 77.4% (75.8–78.9%) for 3-year RFS. The GC cohort demonstrated comparatively poorer survival outcomes, with 5-year OS rate of 67.8% (64.3–71.4%) and 3-year RFS rate of 67.6% (64.4–70.9%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Elevated preoperative CEA was significantly associated with poor prognosis in each cancer (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Prognostic utility of preoperative and postoperative ChE levels

Of all enrolled patients, 468 individuals were excluded due to unavailable preoperative ChE data. The RCS curve between the continuous preoperative ChE and OS was L-shaped, showing that the risk of death increased with the decline of preoperative ChE levels (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by preoperative ChE status are shown in Supplementary Table 1. In the normal (n = 5118) and low (n = 339) preoperative ChE status group, the 5-year OS rates (95 CIs) were 80.8% (79.7–82.0%) and 65.5% (60.4–71.0%) (Supplementary Fig. 4b). After adjusting for potential confounders, the low preoperative ChE group had a significantly higher hazard ratio (HR) for OS compared with the normal preoperative ChE group (HR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.25 to 1.84, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Among 5457 patients with available preoperative ChE, 40 patients without available postoperative ChE were excluded in the analysis of postoperative ChE. The continuous association between postoperative ChE levels and OS was also L-shaped, with a steeper slope than preoperative ChE (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Descriptive statistics for patients stratified by postoperative ChE status, including the normal group (n = 4227) and low group (n = 1190), are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The 5-year OS rates (95 CIs) for these two groups were 82.2% (81.0–83.4%) and 71.5% (68.9–74.3%), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Multivariable analysis demonstrated that postoperative ChE status was independently associated with survival, yielding an adjusted HRs of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.37 to 1.82, P < 0.001) for the low versus normal ChE group (Table 2).

Prognostic utility of perioperative ChE changing patterns

Postoperative ChE decline demonstrated a dose-dependent association with mortality risk in all patients, and the slope of decrease was significantly steeper in preoperative normal-ChE subjects compared to their low-ChE counterparts (Fig. 2a). Perioperative ChE maintained normal in 4102 (75.7%) patients, normalized in 125 (2.3%) patients, lowered in 990 (18.3%), and maintained low in 200 (3.7%) patients. The persistently normal group demonstrated favorable tumor biology with lower pathological T and N stages (Supplementary Table 3).

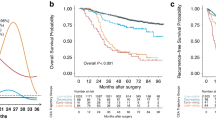

a Association between postoperative ChE and overall survival on a continuous scale in the normal and low preoperative ChE group. b Kaplan–Meier curves of Persistently normal, normalized, lowered, and persistently low perioperative ChE changing groups for overall survival in overall patients. In a, solid lines are unadjusted hazard ratios, with dashed lines showing 95% confidence intervals derived from restricted cubic spline regressions. Reference lines for no association are indicated by the solid gray lines at a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.0. ChE cholinesterase.

Stratification by perioperative ChE changing patterns revealed survival disparities (overall log-rank P < 0.001). The 5-year OS rates progressively declined from 82.5% (95% CI: 81.2–83.7%) in the persistently normal group to 59.4% (95% CI: 52.7–67.0%) in the persistently low group, with intermediate outcomes for normalized (73.3%, 95% CI: 65.8–81.7%) and lowered (73.9%, 95% CI: 71.1–76.9%) patterns (Fig. 2b). Multivariable Cox regression confirmed escalating mortality risks versus the persistently normal reference: normalized (HR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.03, P = 0.030), lowered (HR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.38 to 1.86, P < 0.001), and persistently low (HR: 1.98; 95% CI: 1.55 to 2.54; P < 0.001) (Table 2). This dose-response relationship persisted in patients with normal/elevated preoperative CEA levels (Supplementary Table 4), affirming perioperative ChE patterns as an independent prognostic determinant.

Prognostic utility of longitudinal ChE trajectories

For longitudinal ChE trajectory analysis, 3032 patients with 22379 ChE measurements were included. Postoperative ChE measurements were sparse and irregular, and the distribution of testing time was shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Based on Bayesian information criterion and mean posterior probabilities (Supplementary Table 5), three trajectory groups were identified for longitudinal ChE. In the slow-rising group (n = 2739, 90.30%), ChE levels increased slowly in the first year after surgery and remained stable thereafter. In the rising-decreasing group (n = 188, 6.20%), ChE levels increased within 1 year after surgery and decreased rapidly thereafter. In the decreasing-rising group (n = 105, 3.50%), ChE decreased firstly and then increased during 1–2 years after surgery (Fig. 3a). The shapes of the longitudinal ChE trajectories are basically consistent across cancer types (Supplementary Fig. 6).

There were significant differences in age, preoperative ChE, pathological stage and adjuvant chemotherapy among the three ChE trajectory patterns (Supplementary Table 6). Distinct longitudinal ChE trajectories demonstrated prognostic stratification for overall survival (overall log-rank P < 0.001). The slow-rising trajectory group exhibited superior 5-year OS rate (79.7%; 95% CI: 78.2–81.3%), surpassing both rising-decreasing (5-year OS rate: 64.8%, 95% CI: 58.1–72.4%) and decreasing-rising (5-year OS rate: 58.1%, 95% CI: 49.0–68.9%) groups (Fig. 3b). After multivariable adjustment, both decreasing trajectories showed elevated mortality risks versus the slow-rising pattern, with adjusted HR 1.50 (95%CI: 1.14 to 1.99, P = 0.004) for the rising-decreasing pattern and 2.33 (95%CI: 1.69 to 3.22, P < 0.001) for the decreasing-rising pattern (Table 2). This associations persisted robustly in patients with normal preoperative or postoperative ChE (Supplementary Table 7). CEA-stratified analyses yielded results similar to overall patients (Supplementary Table 8).

Subgroup analyses

The associations of preoperative, postoperative, and perioperative ChE groups with OS were all significant in each cancer type, while the longitudinal ChE groups were significantly associated with OS only in NSCLC and CRC (Supplementary Figs. 7–9). In stage I patients, no significance of preoperative ChE was observed, but low postoperative ChE, lowered perioperative ChE, and decreasing-rising ChE trajectory were significant (Supplementary Table 9). The results in stage II and III patients were basically significant, except for the normalized group in stage III patients and the rising-decreasing group in stage II patients (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11). In the subgroup analysis according to patients’ clinical characteristics, similar results to the overall population were observed (Supplementary Figs. 10–12). In consideration of the RFS, perioperative ChE changing patterns and longitudinal ChE trajectories were also independent prognostic factors (Supplementary Table 12 and Fig. 13).

Discussion

Based on retrospective cohorts of NSCLC, CRC, and GC patients that were tracked over time, this study identified dynamic changes of ChE and evaluated their associations with cancer prognosis at different time points. Beyond the established utility of preoperative ChE, postoperative ChE emerged as an independent prognostic factor in human cancers. Postoperative ChE could further stratify the prognosis of patients with normal and low preoperative ChE, providing additional prognostic value. Longitudinal trajectory patterns of ChE, derived from serial measurements, were associated with prognosis even in patients with normal preoperative and postoperative ChE, demonstrating the importance of following-up ChE in cancer prognosis surveillance. When evaluated in patients with normal and elevated CEA, the prognostic value of ChE dynamic changes was still significant, suggesting an important role of ChE in complementing CEA. To our knowledge, this is the first study on the clinical value of following-up postoperative ChE, which will provide new insights into the practical use of ChE in cancer patients.

Regarding the prognostic value of preoperative ChE in human cancers, our study found results consistent with previous studies23,24,25. However, ChE levels may change after surgery, reflecting the postoperative recovery status of patients. In a study on esophageal cancer, ChE levels were measured at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively and were found to reach their lowest point at 3 months after surgery26. In this study, we defined postoperative ChE as the last ChE measurement within 3 months after surgery, and observed that the proportion of patients presenting with low postoperative ChE was higher than those having low preoperative ChE (21.8% vs. 6.2%), indicating that postoperative ChE may be more sensitive to identify high-risk patients than preoperative ChE. Considering perioperative ChE changing patterns, we found distinguishing risks of patients with persistently normal and lowered perioperative ChE, as well as those with normalized and persistently low perioperative ChE, and this may support combining postoperative ChE in addition to preoperative ChE to stratify cancer patients for graded surveillance. A study on ChE in GC patients treated with first-line chemotherapy paralleled our findings to some extent27.

Based on the sparse and irregular repeated measurements of ChE collected during follow-up, three longitudinal ChE trajectories representing the overall profiles over a 24-month period were visualized. In patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma, multiple cholinesterase (ChE) levels were measured from the preoperative period to 6 months postoperatively, with an increase observed during this period28. Similarly, a study of rectal cancer patients who underwent low anterior resection showed that ChE levels increased rapidly from preoperative to 3 months after surgery, and then became gentle during 3–6 months after surgery29. Despite the limited follow-up time, rising ChE trends in these studies support the slow-rising and rising-decreasing ChE trajectory patterns identified in this study. Previous studies have reported changes in serum ChE levels during the period of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in cancer patients, and an upward trend in ChE levels was confirmed as a sign of a sustained response to postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy30,31.

Acetylcholine is reported to be involved in cell adhesion, differentiation and proliferation, and the upregulated acetylcholine resulting from the low ChE promoted the growth of cancer cells, which explained the effect of ChE on cancer progression from a pathophysiological mechanism32,33. In addition, tumor-related chronic inflammation and malnutrition may explain the association between reduced ChE levels and poor prognosis8. The prognostic value of ChE in CEA subgroups suggested a complementary effect, and a combination of tumor markers reflecting tumor burden and ChE representing nutritional and immune status may contribute to more accurate risk stratification. A previous study reported an association of preoperative ChE with OS only in patients with advanced NSCLC23. Similarly, in our subgroup analysis of stage I patients, no significant association between preoperative ChE and prognosis was observed. However, it must be mentioned that postoperative ChE and its dynamic changes have important prognostic value even in stage I patients, suggesting a potential application of postoperative ChE in early-stage cancer.

Based on a pan-cancer cohort of NSCLC, CRC, and GC patients, our study elucidated the prognostic value of perioperative and longitudinal changes of ChE in human cancers, filling a gap in existing studies. The large sample size, comprehensive analysis and stable results ensured the validity and reliability of this study. Subject to retrospective design, inherent limitations existed in our study, and the conclusions should be verified in a prospective cohort in the future34. Despite covariates were adjusted in our models, the results may be biased by unmeasured confounding factors. Besides, only patients with four or more ChE measurements within 2 years after surgery were included in the trajectory analysis, which may bring selection bias. The longitudinal ChE trajectory identified by LCGMM is data-driven, and the lack of independent validation datasets may limit its clinical application in a broader population. On the other hand, although three types of cancer were considered in this study, all participants were from the Yunnan Cancer Hospital, and a multi-center study is needed to account for the generalizability and extrapolability of our findings. Finally, due to the lack of availability, we did not control for diseases affecting ChE levels, such as chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis35.

Conclusion

In conclusion, considering perioperative and longitudinal dynamic changes of ChE will benefit the identification of high-risk patients with poor prognosis, promoting individualized prognostic surveillance and management. A routine follow-up of postoperative ChE was recommended to improve the prognosis risk stratification of cancer patients.

Data availability

All source data underlying the graphs and charts presented in the main figures was shown in Supplementary Data 1. Other data will be shared on a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

All statistical analyses mentioned above were performed using R software (version 4.1.3). RCS analysis was implemented with the R package “rms” (version 6.5-0). LCGMM was implemented with R package “lcmm” (version 2.0.2).

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48 (2023).

Feng, R. et al. Cancer situation in China: what does the China cancer map indicate from the first national death survey to the latest cancer registration? Cancer Commun. 43, 75–86 (2023).

La Thangue, N. B. & Kerr, D. J. Predictive biomarkers: a paradigm shift towards personalized cancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 8, 587–596 (2011).

Kerr, D. J. & Yang, L. Personalising cancer medicine with prognostic markers. EBioMedicine 72, 103577 (2021).

Duffy, M. J. et al. Tumour markers in colorectal cancer: European Group on Tumour Markers (EGTM) guidelines for clinical use. Eur. J. Cancer 43, 1348–1360 (2007).

Duffy, M. J. et al. Tumor markers in colorectal cancer, gastric cancer and gastrointestinal stromal cancers: European group on tumor markers 2014 guidelines update. Int. J. Cancer 134, 2513–2522 (2014).

Burnett, W. An assessment of the value of serum cholinesterase as a liver function test and in the diagnosis of jaundice. Gut 1, 294–302 (1960).

Santarpia, L., Grandone, I., Contaldo, F. & Pasanisi, F. Butyrylcholinesterase as a prognostic marker: a review of the literature. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 4, 31–39 (2013).

von Deimling, M. et al. Clinical value of cholinesterase in patients treated with radical nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract carcinoma. World J. Urol. 41, 1861–1868 (2023).

Koie, T. et al. Significance of preoperative butyrylcholinesterase as an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence-free survival in patients with prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 379–383 (2016).

Kimura, S. et al. Prognostic value of serum cholinesterase in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 16, e1123–e1132 (2018).

Konishi, T. et al. Association of preoperative and postoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen and colon cancer outcome. JAMA Oncol. 4, 309–315 (2018).

Li, C. et al. Trajectories of perioperative serum tumor markers and colorectal cancer outcomes: a retrospective, multicenter longitudinal cohort study. EBioMedicine 74, 103706 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Perioperative changing patterns and longitudinal trajectories of CA242 with colorectal cancer prognosis: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Sci. Bull. 68, 1875–1879 (2023).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 8.2025. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (2025).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Colon Cancer. Version 4.2025. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf (2025).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Rectal Cancer. Version 3.2025. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf (2025).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Gastric Cancer. Version 3.2025. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf (2025).

Durrleman, S. & Simon, R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat. Med. 8, 551–561 (1989).

Harrell, F. E. General Aspects of Fitting Regression Models. In Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. 11–40 (Springer, 2001).

Li, Z. et al. Trajectories of perioperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen and colorectal cancer outcome: a retrospective, multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Clin. Transl. Med. 11, e293 (2021).

Lennon, H. et al. Framework to construct and interpret latent class trajectory modelling. BMJ Open 8, e020683 (2018).

Ran, H. et al. Serum cholinesterase may independently predict prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 22, 93 (2022).

Takano, Y. et al. The impact of low serum cholinesterase levels on survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 37, 869–877 (2022).

MON-PO534 Clinical impact of preoperative serum cholinesterase in gastric cancer. Clin. Nutr. 38, S256 (2019).

Ishii, K., Tsubosa, Y., Niihara, M., Akai, T. & Soneda, W. Changes in the nutritional status of elderly patients after esophagectomy. Esophagus 16, 408–412 (2019).

Bi, Y. et al. Cholinesterase is associated with prognosis and response to chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 27, 580800 (2021).

Jaiswal, S. G. & Jaiswal, G. R. Butyrylcholinesterase: an economical marker of disease activity in oral squamous cell carcinoma before and after therapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 16, S39–S42 (2020).

Kawahara, H. et al. Anthropometric assessment after proctocolectomy due to ulcerative colitis. Vivo 33, 239–243 (2019).

Chougule, A., Hussain, S. & Agarwal, D. P. Prognostic and diagnostic value of serum pseudocholinesterase, serum aspartate transaminase, and serum alinine transaminase in malignancies treated by radiotherapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 4, 21–25 (2008).

Coulter, D. W. et al. Butyrylcholinesterase as a blood biomarker in neuroblastoma. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 39, 272–281 (2017).

Campoy, F. J. et al. Cholinergic system and cell proliferation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 259, 257–265 (2016).

Song, P. et al. Synthesis of acetylcholine by lung cancer. Life Sci. 72, 2159–2168 (2003).

Wang, X. & Kattan, M. W. Cohort studies: design, analysis, and reporting. Chest 158, S72–S78 (2020).

Kawasaki, H., Hori, T., Nakajima, M. & Takeshita, K. Plasma levels of pipecolic acid in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology 8, 286–289 (1988).

Acknowledgements

This study is a joint effort of many investigators and staff members, and their contribution is gratefully acknowledged. We especially thank all patients who participated in this study. This work was funded by the Expert Workstation Fund [202405AF350074], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [82073569, 82222064, 82360345, and 82001986], the Outstanding Youth Science Foundation of Yunnan Basic Research Project [202401AY070001-316], the Innovative Research Team of Yunnan Province [202505AS350013], the First-Class Discipline Team of Kunming Medical University [2024XKTDTS17], the Medical high-end talents training program of Yunnan Health Commission [L-2024009], the Yunnan Applied Basic Research Projects-Kunming Medical University Union Foundation [202501AY070001-003], the Biomedical Specialization of Yunnan Province [202402AA310012], and the Innovative Research Team of Yunnan Province [202405AS350016].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C., L.Z., Y.D. and Z.T. did the concept and study design. L.C., L.Y., Y.R., L.L., Y.D. and L.Z. participated in the collection and assembly of data. L.C., F.B., L.J. and Z.T. did the statistical analysis and gave interpreted the results. L.C. drafted the manuscript. L.Z., Y.D. and Z.T. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript and approved its final submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Ruth Zarate and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Li, Y., Liu, L. et al. Longitudinal evaluation of serum cholinesterase benefits prognosis surveillance of common types of human cancer. Commun Med 5, 391 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01133-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01133-w