Abstract

Background

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) provides an effective infertility treatment. However, the success of IVF heavily depends on manual morphological assessment of embryos, a process that is both time-consuming and labor-intensive. While artificial intelligence (AI) enables automated assessment, its reliance on centralized large-scale data training raises privacy concerns.

Methods

Here, we develop a distributed AI system, termed ‘FedEmbryo’, tailored for personalized embryo selection while preserving data privacy. Within FedEmbryo, we introduce a federated task-adaptive learning (FTAL) approach with a hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation (HDWA) mechanism. The FTAL integrates multitask learning (MTL) with federated learning (FL) by proposing a unified multitask architecture that consists of shared layers and task-specific layers to accommodate the single- and multi-task learning within each client. The HDWA mechanism considers the learning feedback (loss ratios) from the tasks and clients, facilitating a dynamic balance between task attention and client aggregation.

Results

We conduct extensive experiments in different scenarios of the IVF cycle to evaluate the effectiveness of FedEmbryo for personalized embryo selection. The observer study validates that FedEmbryo achieves superior performance in both morphological valuation and prediction of live-birth outcomes compared to the locally trained model, as well as state-of-the-art FL methods.

Conclusions

We present FedEmbryo, an AI-powered system designed to improve IVF outcomes through privacy-preserving, decentralized training across multiple clinical sites. FedEmbryo demonstrates superior performance in capturing stage-specific morphological features of embryos and achieves accurate predictions for key IVF-related tasks. We hope that FedEmbryo will serve as a practical tool for enhancing clinical decision-making in IVF.

Plain language summary

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) is one of the most widely used methods in assisted reproductive technology (ART). However, IVF success remains highly dependent on manual embryo assessment, a process that is time-consuming and labor-intensive. In this study, we introduce FedEmbryo, an AI system designed to improve IVF outcomes. Our experiments show that FedEmbryo provides more accurate evaluations of embryo quality, including morphological evaluation and live-birth outcomes prediction.This work highlights the potential of FedEmbryo to assist in reproductive healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is a global health concern, affecting ~8–12% of couples in their reproductive age worldwide1. In-vitro fertilization (IVF) has emerged as a transformative tool for infertility2, where the fertilized embryos are cultured and developed within laboratory conditions3,4. During the process, embryologists meticulously select high-quality fertilized embryos for subsequent transfer into the uterus5.

Notably, the selection of transferred embryos to achieve an ultimately live birth is still challenging6. In clinical practice, embryologists conduct morphological assessment of embryos through a series of visual examinations. This evaluation is inherently a multitask process, requiring the simultaneous evaluation of multiple aspects, including cell symmetry, blastomere count, degree of cellular fragmentation, and blastocyst formation7,8,9,10,11. Each of these assessment dimensions is essential for determining high-quality embryos for transfer. However, the process is heavily dependent on specialized expertise and remains both time-consuming and labor-intensive. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a standardized and automatic assessment approach that improves the prediction of live-birth outcomes while also offering a clear illustration of decision-making. Artificial intelligence (AI) has recently garnered increased attention in IVF12, demonstrating clinician-level performance on tasks, such as embryo morphological rating13,14,15 and implantation prediction16. However, many deep learning (DL)-based methods are centralized training and are highly dependent on the availability of training data17,18, thus facing challenges due to the limitations of privacy regulations19,20,21,22. To address the issues, federated learning (FL)23,24 has emerged as a promising technique that enables privacy-preserving distributed training25. In FL, each participating client (‘nodes’) trains a local model using its own data, and the central (‘federated’) server aggregates these models to update a global model incorporating knowledge from all candidates26. This application of FL highlights its suitability for tasks requiring careful handling of sensitive data, especially the human IVF-derived embryos.

Although FL methods have demonstrated potential in healthcare applications27,28,29,30, they still face substantial challenges in real-world clinical scenarios. The previous approach primarily focuses on scenarios where clients own a single task, overlooking the complexities of medicine that each client is often required to process multiple FL tasks simultaneously. Recent studies have started exploring FL settings by integrating multitask learning (MTL)31, designed to enable clients to train different task types via FL32 concurrently. For embryo selection, covering the in-vitro fertilization cycle, it involves a series of tasks from multitasking embryo morphology assessment to single-task live-birth occurrence prediction. Therefore, developing a task-adaptive FL framework for various clinical tasks remains an unresolved challenge. Furthermore, applying such setups within the FL framework introduces challenges of task conflicts, leading to the degradation of FL in non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) scenarios across various centers33,34,35. Although recent studies have proposed to mitigate this issue36,37,38, such as integrating a proximal term into the optimization objective36, they may struggle to adapt to the complex multi-task learning paradigms. Therefore, it is crucial to design a federated task-adaptive learning capable of processing various tasks simultaneously while mitigating heterogeneity in real-world, non-IID clinical scenarios.

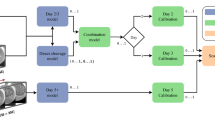

To address the issues above, we build a distributed DL system called FedEmbryo, which enables decentralized collaboration of embryo data to build personalized embryo selection while preserving data privacy (Fig. 1a). In FedEmbryo, we introduce a federated task-adaptive learning (FTAL) approach with a hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation (HDWA) mechanism, which facilitates simultaneous learning of diverse tasks and dynamically balances contributions from each task during client training and weight allocation during server aggregation. Specifically, we propose a client architecture featuring both shared and task-specific layers, which supports both single- and multi-task learning within each client. By applying HDWA, we can dynamically adjust weight coefficients based on feedback (loss ratios) at both inter- and intra-clients, thus enabling adaptable collaboration among clients with different task setups.

a Schematic of the FedEmbryo. FedEmbryo is a federated task-adaptive learning (FTAL), which focuses on the client processing multiple tasks simultaneously. We incorporate four private clients collaboratively training the model without any data sharing. For each communication round, every client transmits their local model and the corresponding loss ratio to the server. The server then aggregates these local models and redistributes the updated model to clients. b In FedEmbryo, we introduce the hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation (HDWA) mechanism to dynamically balance the weight coefficient at both client and task levels. The server (Upper) assigns the aggregated weight based on the loss ratio λt, derived from previous \(t-1\) to \(t-2\) communication rounds. Unlike traditional approaches, where client weight remains fixed, the HDWA mechanism dynamically balances the weight based on client performance in each training round. At the client level (Bottom), the framework manages complex clinical practices, such as morphology assessment (Bottom Left) and prediction of live-birth outcomes (Bottom Right). We utilize the HDWA mechanism to balance the weights to various tasks—such as pronuclear features, symmetry, cell count, fragmentation rate, and blastocyst formation—based on the loss ratios from the two previous local epochs. We integrate images and clinical factors as multimodal input to improve the prediction of live-birth outcomes. c Datasets description (N is the number of patients).

Here, we adopt FedEmbryo to develop a personalized AI model to address key clinical scenarios in the IVF process, including morphology assessment and live-birth outcomes. Each client, representing an individual clinic or hospital, contributes its locally held embryo datasets for model training. Through collaborative training, FedEmbryo aggregates local models from multiple clients to update the global model. Specifically, for multitask morphology assessments that involve evaluations at pronuclear, cleavage, and blastocyst stages, we consider each morphology metric as a separate task within a client’s model to perform multi-task learning. The HDWA mechanism is implemented to effectively balance various tasks within clients and aggregate learning between clients. Furthermore, predicting live-birth outcomes presents another challenge, which involves various clinical factors such as maternal age, endometrium, infertility duration, and abortion history. FedEmbryo processes this as a single-task problem, utilizing both embryo images and clinical factors as multimodal features to enhance prediction accuracy.

We have conducted extensive experiments in different scenarios of the IVF cycle to evaluate the effectiveness of FedEmbryo for personalized embryo selection. The results demonstrate that FedEmbryo achieves superior performance in both morphological valuation and prediction of live-birth outcomes compared to the locally trained model, as well as several SOTA FL methods. Our approach demonstrates the potential to tackle FL’s data heterogeneity challenge and effectively manage varying data domains and task complexities, accommodating both single-task and multi-task scenarios.

Methods

Dataset characteristics

Data collection and ethics statement

In this study, we systematically collected a large multimodal embryo dataset consisting of embryo images, maternal metadata, and clinical outcomes. The data were collected from the China Consortium of Assisted Reproductive Technology Investigation (CC-ARTI), which consisted of hospitals/cohorts from Beijing, Hubei Province, Hunan Province, and Guangdong Province between March 2010 and December 31, 202139.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee approvals were obtained in all locations (approval Nos. LL-SC-SG-2013-007 and 2020-30401). This study was conducted strictly with the mandates of the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and the Chinese Health and Quarantine Law. All data used in this study were anonymized. All participants provided written informed consent prior to data anonymization. No personally identifiable information was included in the dataset.

Image acquisition and quality control

Embryo images were captured under optimal lighting conditions to facilitate clear and comprehensive visualization of the entire embryo, including the zona pellucida. The embryo was centrally positioned within the image frame, with no descriptive text or symbols obstructing its visibility. Imaging was performed using the inverted microscope (ECLIPSE Ti2-U, Nikon) at ×200 magnification of observation, whose presentations were gray prospects. Furthermore, there were no instances of hardware-related issues with the imaging equipment employed across all clinics. All images were labeled by qualified embryologists. Embryologists followed the Istanbul consensus guidelines (Supplementary Table 13) for the evaluation of oocytes and fertilized embryos. Any annotations that were considered ambiguous or unclear were removed from our dataset.

Federated training and validation data

To train the machine learning model within the federated network, we incorporated four clients, denoted as Client A through Client D. Each client was responsible for distinct tasks related to embryo morphological assessment and live-birth prediction. The dataset from each client was divided into training, validation, and testing, following a distribution ratio of 70%, 20%, and 10%, respectively, based on the number of patients (Fig. 1c). For the morphological assessment task, Client A had 255 patients and 354 images for training, 94 patients and 126 images for validation, and 82 patients and 121 images for testing. Client B had 413 patients and 2191 images for training, 169 patients and 826 images for validation, and 166 patients and 921 images for testing. Client C had 1263 patients and 6813 images for training, 485 patients and 2477 images for validation, and 455 patients and 2447 images for testing. Client D had 915 patients and 2282 images for training, 335 patients and 813 images for validation, and 295 patients and 756 images for testing. For the live-birth prediction task, Client A had 243 patients and 428 images for training, 37 patients and 113 images for validation, and 76 patients and 266 images for testing. Client B had 187 patients and 622 images for training, 26 patients and 88 images for validation, and 55 patients and 194 images for testing. Client C had 547 patients and 1828 images for training, 78 patients and 253 images for validation, and 157 patients and 525 images for testing. Client D had 457 patients and 1492 images for training, 65 patients and 205 images for validation, and 131 patients and 420 images for testing. More details were reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 6.

To assess the performance of the trained model, we utilized both internal and external test sets. The internal tests were derived from subsets of each client's data. Specifically, each client (Client A through Client D) retained 10% of their data as a testing set during the data partitioning process. These internal test sets were used to evaluate the model’s performance within each respective client, ensuring that the model achieved superior performance on data from the same source. To further assess the model’s robustness in the FL, we incorporated two external test sets: Cohorts E and F. Cohort E consisted of 992 patients and 6090 images for the morphological assessment task, as well as 376 patients and 1297 images for the live-birth prediction task. Cohort F included 497 patients and 2689 images for the morphological assessment task, and 190 patients and 533 images for the live-birth prediction task. More details were reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 6. The external test sets were employed to evaluate the model’s effectiveness on unseen data. This comprehensive validation strategy allowed us to assess the model’s robustness in real-world clinical settings.

The framework of FedEmbryo

Overview

In this study, we present FedEmbryo, a distributed DL system designed to facilitate collaborative model training for embryo evaluation in ART among clients while preserving data privacy (Fig. 1a). FedEmbryo introduces a task-adaptive FL approach to handle the complex embryo selection scenarios involving both multi-task and single-task learning settings. To address the inherent intra-client (task level) and inter-client (client level) data heterogeneity challenges across multiple centers, we propose a novel algorithm called the hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation (HDWA) mechanism (Fig. 1b). Specifically, the HDWA evaluates losses from preceding communication rounds (epochs) and computes a customized ratio to reweight the weight coefficients within the client’s multi-task learning and during the server’s aggregation process. By considering the individual learning feedback, the HDWA mechanism comprehensively enhances collaborative efforts among clients with various tasks.

Additionally, we implement FedEmbryo in clinical scenarios of embryo clinical assessments, including morphological evaluations and predictions of live-birth outcomes (Fig. 1c). In morphology assessment, our multi-task client architecture facilitates the measurement of key morphological features at different stages of embryo development, such as pronucleus symmetry during the pronuclear stage, the number of blastomeres, asymmetry, and fragmentation of blastomeres during the cleavage stage, as well as the formation of blastocysts in the blastocyst stage. For live-birth outcomes, FedEmbryo applies to single-task FL, specifically employing a multimodal approach that integrates embryo images and relevant clinical factors into the ML models. Finally, we also adopt an interpretable approach within the FL framework to investigate key factors influencing decision-making, thus enhancing adaptability and effectiveness in real-world clinical settings.

Problem setup and objective formulation

FedEmbryo follows the standard workflow of FL to collaboratively train a global model that allows each client in the federation to achieve high-quality embryo selection and accurate prediction of live-birth outcomes. Specifically, we consider a set of K clients, where jth client \({C}_{j}\) has their own local dataset \({D}_{j}=\{{X}_{j},{Y}_{j}\}\) consisting of \({N}_{j}\) embryo images. The overall objective of FedEmbryo is to minimize the following:

where \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j}({\omega }_{j})\) denotes the loss for client \({C}_{j}\). Due to the continuous nature of embryonic development and distinct evaluation metrics at each stage, a client is required to handle single or multiple tasks simultaneously. Given m learning tasks owned by client \({C}_{j}\), \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j}\) is defined to \({\sum }_{i=1}^{m}{\alpha }_{j,i}{\sum }_{{x}_{j,i}}^{{N}_{j,i}}{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j,i}({\omega }_{j};{x}_{j,i},\,{y}_{j,i})\), where \({\alpha }_{j,i}\) is ith task’s weight coefficient for client \({C}_{j}\). It is clear that the performance of FedEmbryo is influenced by hyperparameters of βand α. In this work, we propose the hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation (HDWA) to balance these two factors.

Hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation

Normally, the value of β relies primarily on the total quantity of client data and typically serves as a constant factor during the server aggregation. However, data heterogeneity (e.g., imbalanced quantity) inter client, introduce bias into the learned model, with clients possessing larger datasets potentially dominating the learning process. Moreover, variations between clients, such as differences in task labels or data size, also influence the learning process. To mitigate this issue, we present the hierarchical dynamic weighting adaptation module (HDWA), which dynamically balances the weight coefficient of inter-clients and intra-clients, thus preventing the model from being disproportionately influenced by certain participants. The HDWA mechanism establishes a hierarchical relationship between clients and tasks. It utilizes the cumulative loss to dynamically determine the weight coefficient allocation for each task and client. Specifically, the losses observed in the previous two communication rounds (epochs) are used to calculate the loss ratio. Based on this loss ratio, weight coefficients are assigned to each client (task) for the current communication round (epoch). By dynamically adjusting the weight coefficients, we can effectively capture the unique features contributed by each client (task). The hierarchical DWA involves two phases: local update and server aggregation.

Local update

Assume rth communication round, the local model \({\omega }_{j}\) of client \({C}_{j}\) receives the global model \({\omega }_{g}\) from the server. Client \({C}_{j}\) updates the local model \({\omega }_{j}\) through the process of forward propagation followed by backpropagation. Given eth local epoch, the loss ratio \({r}_{j,i}(e)\) for ith task of the client \({C}_{j}\) is defined by \({r}_{j,i}(e)=\frac{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j,i}(e-1)}{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j,i}(e-2)}\), where \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j,i}\) is the loss for ith task. Then, the weight coefficient \({\alpha }_{j,i}\) for ith task is defined by

where τ is the hyperparameter. Over several local epochs, we compute the total loss ratio \({\lambda }_{j}\left(r\right)\) of client \({C}_{j}\) by \({\lambda }_{j}(r)=\frac{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j}(r-1)}{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j}(r-2)}\), where \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j}\) is the sum of \({ \{ {{{\mathcal{L}}}_{j,i}} \}}_{i=1}^{m}\). Finally, client \({C}_{j}\) sends loss rate \({\lambda }_{j}\left(r\right)\) and model \({\omega }_{j}\) to the server.

Server aggregation

Given rth communication round, server receives models \({\{{\omega }_{j}\}}_{j\in K}\) and loss ratios \({\{{\lambda }_{j}(r)\}}_{j\in {{\rm{K}}}}\) from clients. The weighting coefficients \({\beta }_{j}(r)\) for client \({C}_{j}\) is defined by

where τ is the hyperparameter. For the first and second round (epoch), we initialize \({\beta }_{j}\) and \({\alpha }_{j,i}\) to 1.

Assessment of embryo morphology

To effectively showcase the capabilities of FedEmbryo, we conduct assessments focused on embryo morphology at both Day 1 and Day 3, as well as blastocyst formation on Day 5. The evaluation tasks for embryo morphology include predicting abnormal pronuclear (single nucleolus or more than double nucleoli) during the pronuclear stage, predicting the number of cells, and assessing the degree of cell symmetry and blastomere fragmentation during the cleavage stage. During the blastocyst stage, the assessment of blastocyst formation is conducted using embryo images from Day 1 and Day 3 to predict the probability of blastocyst development. The regression tasks involve formulating the fragmentation rate and number of cells. The classification tasks involve the identification of abnormal nucleoli, blastomere asymmetry, and blastocyst formation.

Multitask learning

We design a unified multi-task model to perform multiple related tasks simultaneously on each client, which facilitates the learning of correlations between tasks. We build upon the ResNet-50 architecture40 and adapt it to support multi-task training. The model is divided into two main components: shared layers and task-specific layers. The shared layers consist of the original convolutional blocks from ResNet-50, which are responsible for extracting common features. In addition to the shared layers, we introduce task-specific layers designed to capture features unique to each individual task. For regression tasks, a fully connected layer is employed with a single scalar output. The output is then rounded to an integer for ordinal regression purposes. For classification tasks, an additional SoftMax layer is appended to the fully connected layer, enabling the model to output probabilities for each class. The separation of task-specific and shared layers ensures that while the model benefits from common representations, it also learns specialized features for each task independently. Each task is associated with its own objective function. Regression tasks utilize the mean squared error (MSE) loss function. Classification tasks are optimized using the cross-entropy loss function. To effectively handle multiple tasks, it is essential to balance their respective contributions to the overall loss during the training process. To achieve this, we implement a task weighting strategy, which is an integral component of the HDWA mechanism. This strategy dynamically adjusts the weight assigned to each task throughout the local training process. By allocating higher weights to more challenging tasks and lower weights to simpler ones, the task weighting strategy mitigates the risk of overfitting on easier tasks. The integration of the multi-task model with the task weighting strategy facilitates the joint training of multiple tasks, effectively leveraging both shared and task-specific representations.

Prediction of live-birth outcomes

The live-birth outcomes are closely associated with the three developmental stages, which is a crucial indicator for measuring the success of IVF technology. The term ‘live birth’ is defined as the successful delivery of an infant after a gestational period of 24 weeks or more, followed by the infant’s survival for at least one month after birth.

We developed the live-birth outcomes prediction to demonstrate the effectiveness of FedEmbryo. An accurate prediction can help embryologists make an appropriate selection for embryo transfer. We first take the images annotated outcomes label as model input. Each client trains a local model based on the ResNet-50 model, pre-trained with the ImageNet dataset41. To collaboratively learn a robust model, we use hierarchical DWA for model aggregation.

Multimodal fusion

To improve the overall performance of live-birth outcomes, we integrate clinical factors and images as multimodal input into our model. For this, we design a revised ResNet-50 model to accommodate multimodal. Specifically, this model consists of two branches: the standard five-stage convolutional layers of ResNet-50 for image feature extraction, and a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to extract clinical features. A concatenation layer is then used to combine both image and clinical features. Lastly, the decision layer is added to the model to generate the multimodal prediction. For the clinical modality, we select maternal and paternal age, endometrial thickness, FSH level, paternal age, BMI, AMH level, the number of oocytes, infertility duration, endometrium (triple-line, weak triple-line, and hyperechoic line), and abortion (spontaneous, medical, and artificial). For the image modality, we use the static embryo image with the outcome labels. The architecture of the MLP is composed of three sequential layers. It starts with a linear layer mapping input size 16 to output size 64, followed by two more linear layers mapping from 64 to 128, and then from 128 to 256. A ReLU activation function is implemented between layers.

Implementation details

For the task of embryo morphology assessment, we conducted the following settings: embryo images were resized to a uniform dimension of pixels (400 × 400). Within the FL framework, the model was trained by 30 communication rounds, with each client performing four local epochs. We employed the ADAM optimizer42, a learning rate of 10−3, a weight decay of \({10}^{-6}\), and a batch size of 32. For the task related to live-birth outcomes, we performed the following scheme: embryo images were resized to 400 × 400 pixels. Within the FL framework, the model was trained for 35 rounds, with each client executing one local epoch. We utilized an ADAM optimizer, a learning rate of \({10}^{-3}\), a weight decay of \({10}^{-6}\), and a batch size of 32. For both tasks, our client selection criterion involved selecting all clients in every global iteration. We report the hyperparameter grid in Supplementary Table 11. Throughout the training process, transformations were added to these two tasks as data augmentation to increase the diversity and size of the training set. By random horizontal flip, vertical flip, rotation, and brightness, the model improved its generalization ability across variations in input data. In our study, we considered three baseline methods: FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA. FedAvg represented the standard FL algorithm, while FedProx and FedDWA were two of the personalized FL algorithms. All experiments were implemented using with PyTorch framework. The primary software/package versions included Python 3.9.7, Torch 1.10.2, Torchaudio 0.10.2, and Torchvision 0.11.3. The complete list of software/package versions was provided in our open-source code repository. We utilized four NVIDIA Tesla A100 GPUs for our experiments, with each GPU consuming 5111 MiB of memory. The model training required a total of 6.3 h, with detailed information on time consumption per epoch and round provided in Supplementary Table 10.

Embryo culture and assessment

Embryo culture protocols

For the clinical parameters, the endometrial parameters were captured via vaginal ultrasound (Voluson E10, GE). Transvaginal sonographic oocyte retrieval was performed 34–36 h post-trigger, followed by conventional ICSI 3–6 h later. Fertilization was checked 16−18 h post-insemination, and successfully fertilized zygotes (2PN) were individually cultured in G1™ medium (Vitrolife, Sweden) under mineral oil until Day 3. On Day 3, embryos were transferred to G2™ medium (Vitrolife, Sweden) and cultured under controlled conditions (37 °C, 6% CO₂, 5% O₂, 89% N₂) in a humidified incubator until Day 5 or Day 6. Before transfer, thawed embryos underwent brief culture to stabilize. Pregnancy confirmation involved serum HCG testing 12 Days post-transfer and ultrasound detection of a gestational sac with fetal heartbeat at 7 weeks.

Pronuclear stage

At this stage, the zygote is formed, comprising two pronuclei, one derived from the oocyte and one from the sperm. To measure the quality of fertilized zygotes, embryologists typically examine the pronuclear morphology from four key aspects, including size, number, clarity, as well as position. The classification system43 (Supplementary Table 13) categorizes zygotes into four distinct groups, denoted as Z1–Z4, based on the size of the nucleus, the arrangement of the nucleus, the arrangement and distribution of nucleoli, and the position of the nucleus.

Cleavage-stage

By Day 2 or Day 3 following fertilization, the zygote undergoes a cascade of rapid and sequential cell divisions, culminating in the formation of a compacted morula composed of 8–16 cells (Supplementary Table 12). Accurate assessment of embryo morphology during this stage is necessary for embryologists to predict subsequent implantation and pregnancy rates. One widely accepted observation of embryo morphology is based on the Istanbul consensus44. This consensus defines the criteria based on cell numbers, degree of fragmentation, and blastomere symmetry (Supplementary Table 13). Specifically, embryos with equal-sized blastomeres and minimal fragmentation are considered high-quality embryos.

Blastocyst stage

The blastocyst stage represents a more advanced phase of embryonic development, occurring approximately Day 5–Day 6 after fertilization (Supplementary Table 12). Ideally, embryo transfer is typically performed after the embryos have developed into blastocysts. However, the achievement of the blastocyst stage cannot be guaranteed for all embryos, particularly when they exhibit a limited tolerance to artificial culture systems. As a result, high-quality embryos are preferentially transferred on Day 3 of development. Consequently, the ability to identify embryos with the potential for future blastocyst development is crucial for improving the success rates.

Interpretability of AI predictions

AI models often operate as black boxes, making it challenging for clinicians to understand the reasoning behind their predictions. A visualization tool is needed that allows clinicians to gain valuable insights into the decision-making process of AI systems. In this paper, we apply the integrated gradient (IG)45 approach to generate visual explanations for our model and the baseline methods. The IG method is a widely recognized technique that employs gradients to measure the significance of each pixel in the image. By computing the gradient of the output with respect to the input data, IG generates a resulting score that reflects the contribution of each pixel to the final prediction. The derived importance scores enable the generation of heatmap visualizations, where pixel intensity corresponds to predictive relevance, thereby offering an interpretation of the model’s decision-making process. Furthermore, we leverage the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)46 method to illustrate the influence of relevant risk factors on prediction for live-birth outcomes. The SHAP generates visual explanations that highlight the importance of these risk factors.

Statistical analysis

To assess the performance for regression tasks, we applied the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC). For classification tasks, the performance was measured by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of sensitivity versus 1–specificity. The area under the curve (AUC) of ROC curves was reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The estimation of AUC’s 95% CIs was conducted using the non-parametric bootstrap method. This method involved generating multiple resampled datasets from the original data by sampling with replacement, each having the same size as the original dataset. We calculated the AUC for each resampled dataset and repeated this process for 100 iterations to establish a distribution of AUC values. We ordered the bootstrapped AUC scores and determined the lower and upper confidence limits at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, thereby establishing yielding a 95% confidence interval.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Embryo morphology assessment

High-quality embryos are essential for a higher potential of implantation and subsequent development into healthy fetuses. To this end, we applied FedEmbryo to collaboratively train on embryo images across four centers (Client A–Client D), learning morphological features crucial for embryo quality assessment. This assessment originated from the multi-task architecture, including analyzing the pronucleus type during the pronuclear stage, blastomere characteristics (size, symmetry, and fragmentation) during the cleavage stage, and blastocyst formation during the blastocyst stage. To evaluate the performance of FedEmbryo, we adopted morphological assessment indicators that were widely recognized as consensus criteria44. For example, at the pronuclear stage, we utilized the Z-score system47 to evaluate the pronuclear morphology and symmetry grading of pronuclei. As morphological assessment indicators involved regression tasks, the model needed to learn the characteristics of embryos under two different task modes (classification and regression) in multitask learning.

We compared locally trained models with the global FL model on each client’s test data. Table 1 reported that the proposed FedEmbryo exhibited greater assessment accuracy than the Local model when applied to the internal test sets data from all four clients (Client A–D). The AUC scores for three classification tasks (abnormal pronuclear detection47, extreme asymmetry8, and blastocyst formation prediction) demonstrated average improvements of 18.75%, 16.00% and 26.47%. Furthermore, the FedEmbryo successfully increased the PCC score by 38.33% and 95.12% on two regression tasks (blastomere fragmentation and the number of blastomeres prediction). The robustness of our results was validated by repeating the local and FL training on two external datasets of Cohorts E and F. FedEmbryo also demonstrated consistently superior performance, due to its dynamic adjustment of weight coefficients among intra-client (task level) and inter-client (client level), effectively addressing data heterogeneity in multitask scenarios.

To further assess FedEmbryo performance, we compared three state-of-the-art FL methods, FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA. The results demonstrated that FedEmbryo outperformed all baselines across the four clients. For example, the average AUC score of the extreme asymmetry detection indicated that the FedEmbryo outperformed the FedAvg, FedProx and FedDWA by 8.00%, 7.00% and 5.00% on the internal test sets (Table 1). It was noted that although FedProx was a promising solution for addressing data heterogeneity compared with FedAvg, it remained ineffective for handling the multiple sub-objectives involved in the embryo morphology assessment task. Even on two unseen external test sets, FedEmbryo exhibited robustness with the average AUC value improved by 9.00%, 11.00% and 6.00% over FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA, respectively, on the blastocyst formation prediction. In conclusion, compared to other methods, our FedEmbryo ensured that the local features of each client were learned and preserved during the model aggregation, thereby achieving superior performance on embryo morphology assessment.

Effectiveness of the HDWA mechanism across clients

We further investigated the effectiveness of the proposed unified client architecture in addressing the complexities of clinical practices. Variations in label distributions across different tasks and clients introduced biases during local training and server aggregation, adversely impacting the distributed DL system performance. Therefore, we have designed the HDWA mechanism to accommodate this architecture and further demonstrated how the HDWA mechanism effectively optimizes data heterogeneity in both inter-client and intra-client morphological assessment tasks (Fig. 2).

Illustration of the label distribution across four clients and the comparative performance metrics for two models: Local (multitask) and FedEmbryo. a The distribution of labels by client, highlighting the variance in dataset sizes among Client A–D. Each client possesses five types of labels, including Day 1 pronuclear, Day 3 symmetry, fragmentation rate, number of cells, and Day 5 blastocyst formation. b–e Performance metrics for the Local and FedEmbryo models. b Day 1 pronuclear: Client A (n = 290), Client B (n = 1877), Client C (n = 5744), Client D (n = 1910). c Day 3 symmetry: Client A (n = 311), Client B (n = 2061), Client C (n = 5993), and Client D (n = 1941). d Day3 fragmentation rate: Client A (n = 311), Client B (n = 2061), Client C (n = 5993), and Client D (n = 1941). e Day 3 number of cells: Client A (n = 311), Client B (n = 2061), Client C (n = 5993), and Client D (n = 1941). f Day 5 blastocyst formation: Client A (n = 181), Client B (n = 1167), Client C (n = 1930), and Client D (n = 1139). Error bar indicates 95% confidence intervals.

As illustrated in Fig. 2a, the imbalanced distribution of labels across tasks within a client contributed to suboptimal outcomes for multi-task learning of local models. This issue was particularly pronounced in tasks related to the prediction of fragmentation rates and cell numbers (Fig. 2d and e). In contrast, the HDWA mechanism implemented in the FedEmbryo model effectively captured the unique characteristics of each task within a client. This approach resulted in a remarkable improvement, averaging enhancing performance by 65% in fragmentation rate predictions (Fig. 2d) and 57% in cell number predictions (Fig. 2e). It was essential to emphasize that the performance of the FedEmbryo remained consistent across all tasks within a client, as evidenced in Fig. 2b–f. This could be attributed to the HDWA mechanism’s capacity to focus more adeptly on tasks that posed greater learning challenges, thus promoting full learning and ensuring balanced performance across all tasks. Furthermore, data heterogeneity between different clients posed another challenge in server aggregation (Fig. 2a). The traditional aggregation approach, such as FedAvg, tended to be dominated by clients with larger datasets simultaneously at the expense of those with smaller data volumes. To address this, the FedEmbryo incorporated the HDWA mechanism, facilitating the global model to learn features from less data-rich clients. For example, despite Client A having the smallest dataset, the performance of the FedEmbryo was comparable to that of Client C, which had the largest dataset. This demonstrated the effectiveness of the HDWA mechanism in ensuring the aggregation of features across clients.

Live-birth outcomes

We applied FedEmbryo to predict live birth outcomes, which were crucial in the IVF cycle. Following the multi-task embryo morphology assessment, we first conducted image-based experiments to predict the single-task live-birth outcome. Figure 3a showed that local clients achieved AUC scores of 0.73 (0.67, 0.79) and 0.70 (0.66, 0.74) on the internal and the external test sets, respectively. In contrast, FedEmbryo substantially enhanced the performance, achieving AUC scores of 0.80 (0.73, 0.84) and 0.76 (0.73, 0.79), with 9.59% and 8.57% improvements over local models, respectively. These results demonstrated that the local models faced challenges in generating accurate predictions on embryo outcomes due to limited data access, resulting in lower accuracy for live-birth predictions. FedEmbryo, however, overcame this challenge by aggregating embryo features extracted from all clients, consistently achieving AUC scores above 0.75. Moreover, FedEmbryo exhibited the superior performance compared to the SOTA approaches, with improvements of 2.56% over FedAvg and 1.27% over FedProx and FedDWA. Crucially, FedEmbryo demonstrated the strong robustness across all methods, showing enhancements of 2.70% over FedAvg, and 1.33% over FedProx and FedDWA on the external test sets.

a AUC score shows performance on live-birth outcomes with the image-only models. The columns list the cohort and different approaches. Cohort includes internal and external test sets. Approaches are: Local scenario (a model trained solely on a single client, representing lower-bound performance), federated baselines (FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA), our approach (FedEmbryo), and centralized scenarios (a model trained centrally on all clients, representing upper-bound performance). b and c ROC curve shows the performance of live-birth outcomes on multimodality, including FedAvg (image), FedProx (image), FedDWA (image), FedEmbryo (image), FedEmbryo (metadata), and FedEmbryo (combined): b External test set (Cohort E); c External test set (Cohort F).

Previous studies indicated that, in addition to the selection of high-quality embryos, live-birth outcomes were also related to clinical indicators, such as maternal age48, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)49, body mass index (BMI)50, infertility duration51, infertility etiology52, endometrium53, among others. To investigate the significance of embryo images and clinical metadata, we incorporated clinical factors to learn the multimodal features of embryos in prediction. Here, we conducted experiments with three model types based on FedEmbryo: the metadata model incorporating only clinical factors, the image model comprising solely embryo images, and the combined model integrating both image and metadata. It was evident that the metadata model was limited in predicting the live-birth outcomes (Fig. 3b and c), with only a 0.65 (0.62, 0.68) AUC score on Cohort E and 0.69 (0.63, 0.74) AUC score on Cohort F. Despite these limitations, FedEmbryo (metadata) still achieved the best average performance compared to federated approaches (FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA) with the metadata models on both external tests (Supplementary Fig. 1). Compared to metadata models, image models demonstrated improved performance, highlighting the critical role of visual data in capturing subtle embryological features. More importantly, the combined models improved the performance, providing a more accurate assessment of embryos’ live-birth potential. For example, the combined models consistently outperformed single-modality models (metadata and image models). Moreover, the FedEmbryo (combined) exhibited the most notable improvement over its metadata counterparts, with enhancements of 16.00% on Cohort E and 11.00% in Cohort F (Fig. 3b, c), which indicated the importance of clinical factors to embryo images. FedEmbryo (combined) also demonstrated superior performance compared to other methods, such as FedAvg (combined), FedProx (combined), and FedDWA (combined) on both internal and external test sets (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Visualization and interpretability

Finally, we have implemented the visualization and interpretability approach to demonstrate the effectiveness of FedEmbryo. For visualization, we compared FedEmbryo with different local clients according to the task of embryonic morphological evaluation. We employed the integrated gradient (IG)45 method to generate saliency maps for various stages of the embryo image, allowing us to identify the most influential pixels. This approach aided in gaining a deeper understanding of the decision-making process underlying FedEmbryo predictions and validating whether these predictions were grounded in clinical reasoning.

Figure 4a presented representative images of embryos on Day 1 and Day 3 from external test sets and their corresponding significance maps generated by four local models and FedEmbryo. On Day 1 images, it was worth noting that the saliency maps from the four clients showed markedly different important areas of attention while making morphological predictions. This divergence was mainly caused by the heterogeneous distribution of local data for each client, leading each client’s model to concentrate solely on the specific embryo features learned from local data. For example, the local models of Clients A through D paid less attention to the nuclei regions of the embryo images on Day 1. This observation reflected real-world scenarios where data heterogeneity was commonly encountered across different clients. When FedEmbryo was deployed for joint training across all clients, it effectively aggregated diverse features from each participant. For instance, the regions highlighted by FedEmbryo on Day 1 images, as shown in Fig. 4a, accurately encompassed the nuclei areas. On Day 3 images, some clients (e.g., Clients A and B) selectively focused on specific cells, which influenced the final prediction of cell quantity and symmetry. However, FedEmbryo still demonstrated superior performance by identifying important pixels across all relevant regions involved in the assessment tasks. Thus, FedEmbryo not only aggregated distinct embryo features between clients but also balanced the models’ attention to different embryo tasks within clients. This observation underscored FedEmbryo in handling data heterogeneity across various scenarios.

a Visual explanations highlight the areas of an image that are most important for a model’s prediction. The row lists the representative embryo images of Day 1 and Day 3 during embryo development. The first column on the left is the original embryo images. The rest of the columns represent the heatmap overlaying the original image generated by Client A; Client B; Client C; Client D; FedEmbryo. b and c Illustration of the contribution of each factor to the model’s prediction of live-birth outcomes by SHAP visualization analysis on: b mean absolute SHAP value of each factor; c detailed SHAP value of each factor.

In the interpretability analysis, we applied the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)46 method to identify the key factors that influenced live-birth predictions within the model (Fig. 4b and c). Our analysis involved image-based predicted scores generated by FedEmbryo, as well as various clinical factors such as maternal age, endometrial thickness, FSH level, paternal age, BMI, AMH level, the number of oocytes, infertility duration, endometrium (triple-line, weak triple-line, hyperechoic line), and abortion (spontaneous, medical, artificial). Figure 4b reported the average absolute values of the effects of each feature contributed to the model’s output. The image-based scores were identified as the most influential factor in predicting live-birth outcomes, demonstrating substantial clinical importance. This result indicated that the use of AI-driven tools, such as FedEmbryo, consequently facilitated superior prediction capabilities. The analysis revealed that maternal age was the second most influential factor substantially affecting model predictions. Additionally, endometrial thickness, FSH levels, paternal age, BMI, AMH levels, and the number of oocytes were also closely related to live birth outcomes. From these rankings (Fig. 4b and c), embryologists could provide more personalized treatments for patients. This observation also indicated that relying solely on images to learn about embryo features was insufficient. The combination of images and clinical factors was essential to achieve a comprehensive understanding and accurate prediction. These results assisted clinical doctors in better assessing patients’ IVF success rates and selecting the best intervention measures to improve the success rate of pregnancy.

Ablation study

In our study, we have conducted a comprehensive ablation study to demonstrate the individual contributions of federated learning, multi-modal integration, and multi-task learning. To evaluate the contributions of federated learning and multi-task integration, we compared the performance of the full FedEmbryo model and its ablation variants on the morphology multitask assessment across both internal and external test sets (Supplementary Table 3). We observed that removing the federated learning module led to a substantial performance degradation across all tasks. For example, in the external test set (Cohort E), the AUC for Day 1 pronuclear assessment dropped from 0.71 (0.68, 0.83) to 0.61 (0.58, 0.64). Similarly, removing the multi-task learning module—i.e., training only one task at a time within the FedEmbryo framework—also resulted in reduced performance. For instance, the AUC for Day 3 symmetry in the external test set (Cohort E) dropped from 0.83 (0.81, 0.95) to 0.75 (0.72, 0.77). Although single-task learning within a federated framework enhanced performance by extracting task-relevant features from globally distributed data, its performance remained inferior to that of the full FedEmbryo model. The result highlighted that the integration of multi-task learning into FedEmbryo enabled the model to effectively capture shared representations across tasks.

To further investigate the contributions of federated learning and multi-modal integration, we presented the results of live-birth outcomes using the full FedEmbryo model and its ablation variants across internal and external test sets (Supplementary Table 7). We observed that removing the federated learning module resulted in a substantial decrease in performance across all test sets. These results demonstrated the role of federated learning in effectively leveraging distributed data to achieve superior performance. Furthermore, when the multi-modal integration module was removed and the model used only metadata, the AUC decreased compared to the full FedEmbryo model. Similar results were also observed when the model used only images. These findings indicated that the combination of metadata and images in the full FedEmbryo model led to superior performance by capturing complementary information from both modalities. In summary, the ablation results highlighted the contributions of federated learning and multi-modal integration (metadata and image modalities) in enhancing the model’s overall performance.

Discussion

Infertility is a globally sensitive issue. According to recent studies, an estimated 48 million couples and 186 million individuals worldwide struggle with infertility54. IVF has revolutionized fertility treatment, being one of the most widely recognized methods in ART2. Successful implementation of IVF can potentially accelerate the time to conception while minimizing the risk of clinical complications. In light of the growing adoption of AI-powered healthcare services27,55,56,57, researchers are exploring the potential of AI to improve IVF outcomes12,13,14,15,16. In this study, we develop an AI-automatic system, FedEmbryo, to improve IVF outcomes (Fig. 1a).

Owing to the sensitive nature of medical data, centralized training is limited in most cases17,22. The emergence of FL has recently enabled the shift from centralized to decentralized training modalities23,24. This approach allows researchers across various regions and hospitals to leverage FL to develop AI-automatic systems for assessing morphology and predicting live-birth outcomes of human embryos30. FL involves local updating and server aggregation. In this study, we follow the standard workflow of FL to develop the FedEmbryo. FedEmbryo enables multiple clients to participate in the training. To validate our assumption, we incorporated four distinct clients for training purposes, along with two external test sets for comprehensive validation (Fig. 1c). We have addressed two clinical scenarios that played a crucial role in IVF treatment: morphology assessment and live-birth outcomes (Fig. 1b).

In real-world clinical practice, data heterogeneity across clients represents a major challenge of FL, often resulting in performance degradation of collaborative learning33,34. Multi-task learning (MTL) aims to solve multiple learning tasks simultaneously while exploiting similarities/differences across tasks31. Early research predominantly adopted MTL’s optimization strategy for personalized federated learning (PFL) contexts58,59,60,61. In non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) scenarios, each client’s personalized optimization objective function was treated as an individual task, with MTL optimization methods managing task heterogeneity arising from diverse client data59,60,61. Classic machine learning tasks like image classification were commonly employed. A handful of studies32,62 have started probing more complex scenarios, aiming to allow clients to train different task types via FL concurrently. In this paper, we introduce a federated task-adaptive learning (FTAL) approach by incorporating a unified client architecture with the HDWA mechanism to facilitate learning of various tasks, such as embryo selection. Specifically, the client architecture is designed with shared layers and task-specific layers to support both single-task and multitask learning within each client. The HDWA mechanism enables the model to fully learn the characteristics of all participating clients by dynamically adjusting weight coefficients based on feedback (loss ratio) at both the client and task levels (Fig. 1b). Table 1 and Fig. 3a have demonstrated that local clients benefit from FedEmbryo, achieving improved performance in various tasks compared to training locally. FedEmbryo also exhibited superior performance compared to other federated approaches (FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA), as shown in Supplementary Table 2. Although our approach requires the transmission of the client-specific loss ratios for adaptive weight calculations, which may incur additional communication overhead, these loss ratios remain lightweight compared to the size of the transmission model parameters. In our experiments, the global model parameters were 169.99 MB, whereas the size of the constant of loss ratios was only 0.00000763 MB. We believe this minimal overhead is a worthwhile trade-off considering the substantial improvements in model performance achieved through HDWA. Moreover, our method has demonstrated faster convergence compared to baseline approaches (Supplementary Fig. 5), effectively minimizing the required communication rounds to reduce communication overhead. Future work could incorporate optimization techniques such as sparse communication mechanisms63 to enhance the method’s scalability and applicability in diverse clinical scenarios. To further validate the effectiveness of FedEmbryo, we have compared its performance with state-of-the-art (SOTA) time-lapse imaging models. Specifically, we integrated two SOTA time-lapse models, the modified ABN model (denoted as ABN*)64 and the modified ResNet model (denoted as ResNet*)65, into our framework on local clients and assessed their performance. Supplementary Tables 5 and 9 reported that the FedEmbryo consistently outperformed both SOTA models, achieving the highest AUC and PCC values across all tasks.

Traditional embryo selection techniques based on morphological assessment can substantially impact IVF success rates. Embryos with better morphological features are more likely to result in a live birth than those with poorer morphology. Examining morphological features involves cell number, size, symmetry, fragmentation, and the formation of blastocysts8,9,10,11. However, embryo selection heavily relies on experience-dependent embryologists, which is both costly and time-consuming7. In this paper, we apply FedEmbryo to achieve an automatic assessment of embryos. While some studies have studied AI-powered morphological assessment and blastocyst prediction13,14,15, we show two key differences. Firstly, the evaluation of the embryo development stage is different. Previous works commonly selected one of the specific development stages, such as Day 113,15, Day 366,67 and Day 514,16, to train the model and make predictions. In our work, the model learns all the features of embryo development from Day 1 to Day 3 and generates prediction. Furthermore, we also predict the blastocyst formation (Day 5) based on this model. Secondly, the evaluation metrics are different. In previous works, models were trained to learn whether an embryo is of high quality based on labels provided by embryologists. In our approach, however, we attempt to train the model to learn multiple indicators, such as cell symmetry, number of blastomeres, cellular fragmentation, and blastocyst formation. To achieve this, we apply the unified multi-task architecture, which allows the model to simultaneously learn multiple morphological features. We incorporate the HDWA mechanism to balance the contributions of each task during the training. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 4, the loss curves for each client showed a consistent decrease across the training rounds, indicating the HDWA mechanism was progressively optimizing for each task. We also have conducted a task-specific performance analysis across key developmental stages (Day 1, Day 3, and Day 5), as presented in Table 1. On Day 1, embryos were in the early pronuclear phase, during which morphological features were relatively subtle and less distinct. This made feature extraction more challenging and resulted in lower AUC and PCC scores. On Day 3, embryos exhibited more distinguishable morphological features, such as symmetry, cell count, and fragmentation degree. These clearer features enabled the model to extract more informative representations, which led to improved performance across all models. On Day 5, the embryos reached the blastocyst formation stage, where morphological patterns were even more well-defined, further enhancing model discriminability. Our proposed approach (FedEmbryo) consistently outperformed the baseline methods across different stages of embryo development, with its robustness and adaptability in capturing stage-specific morphological features and supporting more accurate task-specific predictions.

In clinical practice, visual explanations enhance diagnostic decision-making. For example, in our study involving embryo selection, saliency maps highlight important morphological or structural features that the model considers predictive of successful outcomes. This allows clinicians to compare the model’s focus with their own expertise, potentially identifying overlooked areas or validating their assessments. Therefore, saliency maps offer clear and understandable explanations of specific decisions, enabling clinicians to gain the rationale behind medical recommendations. Figure 4a strongly indicated that FedEmbryo achieved superior performance in generating important pixels covering all the relevant regions involved in the tasks. We have also conducted a case study to illustrate the error classification associated with the baseline model. Supplementary Fig. 3 illustrates the saliency maps generated by three baseline algorithms (FedAvg, FedProx, and FedDWA) and our proposed method (FedEmbryo), highlighting the regions of interest that informed each model’s predictions. The baseline methods exhibited classification errors, whereas our method (FedEmbryo) achieved correct classification performance. In the Day 1 embryo assessment case, FedAvg misclassified the embryo due to its focus on irrelevant noise in the upper-right region, neglecting the pronuclei. Similarly, FedProx failed to detect the pronucleus, and FedDWA was also misclassified by primarily attending to areas surrounding the embryo rather than the central pronuclei. In contrast, FedEmbryo accurately captured both pronuclei within the embryo, demonstrating precise and clinically meaningful attention to these critical regions, resulting in correct classification. On Day 3, all baseline algorithms exhibited limited interpretability by focusing on only a subset of the blastomere cells. This insufficient focus prevented accurate evaluation of key morphological characteristics such as the total cell count, degree of fragmentation, and blastomere symmetry. In contrast, our FedEmbryo method not only achieved accurate classifications but also demonstrated a holistic attention mechanism. This enabled a comprehensive assessment of relevant morphological features, including those often missed by the baselines. These findings highlighted the superior interpretability and accuracy of our proposed method compared to the baseline algorithms.

The primary goal of the IVF procedure is to achieve successful live-birth outcomes. While early studies have incorporated AI to predict these outcomes, such approaches remain limited in clinical practice. Firstly, many of the existing studies have focused on predicting clinical pregnancy outcomes rather than live births. While a clinical pregnancy is an important milestone, it does not guarantee a successful live birth. Secondly, many clinical factors are associated with outcomes, such as maternal age48, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)49, body mass index (BMI)50, infertility duration51, infertility etiology52, and endometrium53, among others. More importantly, the contribution of these factors to live-birth outcomes is not fully understood. In this paper, we first apply FedEmbryo to achieve multi-center live-birth outcomes (Fig. 3a). Secondly, we integrate clinical factors and embryo data as multimodal inputs to predict live-birth outcomes, as illustrated in Fig. 3b, c. Lastly, we implement the SHAP to demonstrate the contribution of each factor to the final outcomes (Fig. 4b, c).

Our study has two limitations. First, all data were derived from the Chinese population. Although we have performed multiple validation runs to evaluate the robustness of our approach (Supplementary Tables 4 and 8) and included confusion matrix to give a detailed view of the classification performance for each task (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), further validation is required to assess the generalizability of our findings across diverse racial groups. Second, we currently adopt a synchronous training approach, which may introduce latency-related challenges, particularly in heterogeneous or resource-constrained settings. In future work, we plan to explore asynchronous methods68 or incorporate client selection strategies69 to mitigate this concern. Additionally, we aim to evaluate the performance of FedEmbryo in more diverse and distributed environments, encompassing varying latency conditions, to better understand its robustness and adaptability in real-world applications.

Data availability

The source data used for validation on the internal test set and two external test sets are available in Supplementary Data 1–4, respectively. The remaining training data, comprising real-world clinical records from hospitals, is not publicly available due to privacy regulations. Access can be requested by contacting the corresponding authors; all requests will be reviewed and approved by the Data Access Committee in accordance with institutional and ethical guidelines.

Code availability

All code necessary to reproduce the results presented here is available at https://github.com/TianrunGaoBupt/FedEmbryo70.

References

Vander Borght, M. & Wyns, C. Fertility and infertility: definition and epidemiology. Clin. Biochem. 62, 2–10 (2018).

Pinborg, A., Henningsen, A.-K. A., Malchau, S. S. & Loft, A. Congenital anomalies after assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 99, 327–332 (2013).

Castillo, C. M. et al. The impact of selected embryo culture conditions on ART treatment cycle outcomes: a UK national study. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, hoz031 (2020).

Wang, J. & Sauer, M. V. In vitro fertilization (IVF): a review of 3 decades of clinical innovation and technological advancement. Ther. Clin. Risk Manage. 2, 355–364 (2006).

Laverge, H., De Sutter, P., Van der Elst, J. & Dhont, M. A prospective, randomized study comparing day 2 and day 3 embryo transfer in human IVF. Hum. Reprod. 16, 476–480 (2001).

Spitzer, D. et al. Effects of embryo transfer quality on pregnancy and live birth delivery rates. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 29, 131–135 (2012).

Machtinger, R. & Racowsky, C. Morphological systems of human embryo assessment and clinical evidence. Reprod. Biomed. Online 26, 210–221 (2013).

Prados, F. J., Debrock, S., Lemmen, J. G. & Agerholm, I. The cleavage stage embryo. Hum. Reprod. 27, i50–i71 (2012).

Ziebe, S. et al. Embryo morphology or cleavage stage: how to select the best embryos for transfer after in-vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod. (Oxford, Engl.) 12, 1545–1549 (1997).

Stylianou, C., Critchlow, D., Brison, D. R. & Roberts, S. A. Embryo morphology as a predictor of IVF success: an evaluation of the proposed UK ACE grading scheme for cleavage stage embryos. Hum. Fertil. 15, 11–17 (2012).

Jones, G. M. et al. Embryo culture, assessment, selection and transfer. In Current Practices and Controversies in Assisted Reproduction, (Eds. Vayena, E., Rowe, P. J. & Griffin, P. D.), 177–209 (World Health Organization, 2002).

Kragh, M. F. & Karstoft, H. Embryo selection with artificial intelligence: how to evaluate and compare methods?. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 1675–1689 (2021).

Manna, C., Nanni, L., Lumini, A. & Pappalardo, S. Artificial intelligence techniques for embryo and oocyte classification. Reprod. Biomed. Online 26, 42–49 (2013).

Septiandri, A. A., Jamal, A., Iffanolida, P. A., Riayati, O. & Wiweko, B. Human blastocyst classification after in vitro fertilization using deep learning. In IEEE International Conference on Advanced Informatics: Concepts, Theory and Applications (ICAICTA), 1–4 (2020).

Ferrand, T. et al. Predicting the number of oocytes retrieved from controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with machine learning. Hum. Reprod. 38, 1918–1926 (2023).

Fitz, V. et al. Should there be an “AI” in TEAM? Embryologists selection of high implantation potential embryos improves with the aid of an artificial intelligence algorithm. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 2663–2670 (2021).

Chilimbi, T., Suzue, Y., Apacible, J. & Kalyanaraman, K. 11th USENIX symposium on operating systems design and implementation. OSDI 14, 571–582 (2014).

Gu, J. et al. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 77, 354–377 (2018).

Vayena, E., Blasimme, A. & Cohen, I. G. Machine learning in medicine: addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Med. 15, e1002689 (2018).

Chen, I. Y. et al. Ethical machine learning in healthcare. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 4, 123–144 (2021).

Horvitz, E. & Mulligan, D. Data, privacy, and the greater good. Science 349, 253–255 (2015).

Heinis, T. & Ailamaki, A. Data Infrastructure for Medical Research (Now Publishers, 2017).

McMahan, B., Moore, E., Ramage, D., Hampson, S., & Arcas, B. A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, (Eds. Singh, A. & Zhu, J.), 1273–1282 (PMLR, 2017).

Yang, Q., Liu, Y., Chen, T. & Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 10, 1–19 (2019).

Gu, R. et al. From server-based to client-based machine learning: a comprehensive survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–36 (2021).

Antunes, R. S., André da Costa, C., Küderle, A., Yari, I. A. & Eskofier, B. Federated learning for healthcare: systematic review and architecture proposal. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 13, 1–23 (2022).

Holmes, J., Sacchi, L. & Bellazzi, R. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 86, 334–338 (2004).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. Federated learning for smart healthcare: a survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–37 (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Federated learning for healthcare informatics. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 5, 1–19 (2021).

Nguyen, T. et al. A novel decentralized federated learning approach to train on globally distributed, poor quality, and protected private medical data. Sci. Rep. 12, 8888 (2022).

Liu, S., Johns, E. & Davison, A. J. End-to-end multi-task learning with attention. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 1871–1880 (2019).

Zhuang, W., Wen, Y., Lyu, L. & Zhang, S. Mas: Towards resource-efficient federated multiple-task learning. In IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 23414–23424 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Federated learning with non-iid data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.00582 (2018).

Zhu, H., Xu, J., Liu, S. & Jin, Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: a survey. Neurocomputing 465, 371–390 (2021).

Kairouz, P. et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 14, 1–210 (2021).

Li, T. et al. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2, 429–450 (2020).

Wang, J., Liu, Q., Liang, H., Joshi, G. & Poor, H. V. Tackling the objective inconsistency problem in heterogeneous federated optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 7611–7623 (2020).

Karimireddy, S. P. et al. SCAFFOLD: Stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), (Eds. Daumé III, H. & Singh, A.), 5132–5143 (PMLR, 2020).

Wang, G. et al. A generalized AI system for human embryo selection covering the entire IVF cycle via multi-modal contrastive learning. Patterns 5, 100985 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778 (2016).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 248–255 (2009).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (ICLR, 2015).

Scott, L., Alvero, R., Leondires, M. & Miller, B. The morphology of human pronuclear embryos is positively related to blastocyst development and implantation. Hum. Reprod. 15, 2394–2403 (2000).

The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1270–1283 (2011).

Sundararajan, M., Taly, A. & Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), (Eds. Precup, D. & Teh, Y.W.), 3319–3328 (PMLR, 2017).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4765–4774 (2017).

Scott, L. Pronuclear scoring as a predictor of embryo development. Reprod. Biomed. Online 6, 201–214 (2003).

Cil, A. P., Bang, H. & Oktay, K. Age-specific probability of live birth with oocyte cryopreservation: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 100, 492–499. e493 (2013).

de Marcillac, F. D. et al. What are the likely IVF/ICSI outcomes if there is a discrepancy between serum AMH and FSH levels? A multicenter retrospective study. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 46, 629–635 (2017).

Amsiejiene, A. et al. The influence of age, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio and anti-Mullerian hormone level on clinical pregnancy rates in ART. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 33, 41–43 (2017).

Pan, Y. et al. Major factors affecting the live birth rate after frozen embryo transfer among young women. Front. Med. 7, 94 (2020).

Eftekhar, M., Rahmani, E. & Pourmasumi, S. Evaluation of clinical factors influencing pregnancy rate in frozen embryo transfer. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 12, 513 (2014).

Kasius, A. et al. Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. update 20, 530–541 (2014).

Ombelet, W. WHO fact sheet on infertility gives hope to millions of infertile couples worldwide. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 12, 249 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Deep-learning-enabled protein–protein interaction analysis for prediction of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and variant evolution. Nat. Med. 29, 2007–2018 (2023).

Wang, G. et al. Optimized glycemic control of type 2 diabetes with reinforcement learning: a proof-of-concept trial. Nat. Med. 29, 2633–2642 (2023).

Lu, Y., Liu, X., Du, Z., Gao, Y. & Wang, G. Medkpl: a heterogeneous knowledge enhanced prompt learning framework for transferable diagnosis. J. Biomed. Inform. 143, 104417 (2023).

Shen, C. et al. Multi-task Federated Learning for Heterogeneous Pancreas Segmentation. In MICCAI Workshop on Distributed and Collaborative Learning (DCL), (Eds. Oyarzun Laura, C. et al), 101–110 (Springer, 2021).

Smith, V., Chiang, C.-K., Sanjabi, M. & Talwalkar, A. S. Federated multi-task learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4424–4434 (2017).

Vanhaesebrouck, P., Bellet, A. & Tommasi, M. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. (Eds. Singh, A. & Zhu, J.), 509–517 (PMLR, 2017).

Zantedeschi, V., Bellet, A. & Tommasi, M. Fully decentralized joint learning of personalized models and collaboration graphs. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, (Eds. Chiappa, S. & Calandra, R.), 864–874 (PMLR, 2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Federated multi-task learning on non-iid data silos: An experimental study. In International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval (ICMR), 684–693 (ACM, 2024).

Zhu, X., Wang, J., Liu, Z. & Zheng, Z. Sparse Communication Mechanism for Federated Learning in IoT Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 12, 15261–15273 (2025).

Sawada, Y. et al. Evaluation of artificial intelligence using time-lapse images of IVF embryos to predict live birth. Reprod. Biomed. Online 43, 843–852 (2021).

Huang, B. et al. Using deep learning to predict the outcome of live birth from more than 10,000 embryo data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 36 (2022).

Kanakasabapathy, M. K. et al. Deep learning mediated single time-point image-based prediction of embryo developmental outcome at the cleavage stage. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.08346 (2020).

Zeman, A. et al. Deep learning for human embryo classification at the cleavage stage (Day 3). In Pattern Recognition. ICPR International Workshops and Challenges: Virtual Event, January 10–15, 2021, Part I 278−292 (Springer, 2021).

Singh, N. & Adhikari, M. A hybrid semi-asynchronous federated learning and split learning strategy in edge networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 12, 1429–1439 (2025).

Pan, Z. et al. RFCSC: Communication efficient reinforcement federated learning with dynamic client selection and adaptive gradient compression. Neurocomputing 612, 128672 (2025).

TianrunGaoBupt. TianrunGaoBupt/FedEmbryo: v1.0.1 (v1.0.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16516520 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants T2522008, 82522048, 62501406, and 62272055), New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GY.W., XH.L., TR.G., YN.Y., K.W., YX.G., LS.M., L.C., GD.L. and P.Z. collected and analyzed the data. TR.G., GY.W. and P.Z. conceived and supervised the project. TR.G., GY.W., XH.L. and YN.Y. wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Abraham Pouliakis, Prudhvi Thirumalaraju and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, T., Yang, Y., Wang, K. et al. Federated task-adaptive learning for personalized selection of human IVF-derived embryos. Commun Med 5, 477 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01182-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01182-1