Abstract

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of disability worldwide, yet its diagnosis relies on clinical symptoms alone.

Methods

Using the semi-supervised machine learning algorithm, Heterogeneity through Discriminative Analysis (HYDRA), we had identified two neuroanatomical dimensions in deeply phenotyped (i.e., comprehensively assessed across neuroimaging, clinical, and behavioural domains), medication-free participants with MDD from the COORDINATE-MDD consortium. In the present study, we apply this pre-trained HYDRA model to the UK Biobank (UKB) to validate these dimensions in a large general population and a subsample with current depressive symptoms.

Results

Dimension 2 (D2), compared to Dimension 1 (D1), is characterized by reduced grey and white matter volumes and limited treatment response to antidepressant and placebo medications. Out-of-sample validation in the UKB general population (n = 37,235) confirms these neuroanatomical features and reveals D2 associations with cognitive impairments, adverse life events, self-harm and suicide attempts, a pro-atherogenic lipid profile, and genetic links to neurodegenerative traits. Similar profiles are observed in the UKB subsample with current depressive symptoms (n = 1455).

Conclusions

D1 and D2 represent distinct neurobiological mechanisms underlying MDD. The validation in a general population-based cohort and in a cohort sample with depressive symptoms delineates mechanisms underlying heterogeneity in MDD.

Plain language summary

Major depressive disorder is a common and disabling condition, but people differ greatly in their symptoms and responses to treatment. We used brain scans and machine learning to identify two patterns of brain structure linked to depression. One pattern showed relatively preserved brain volume and was associated with better treatment response. The other showed widespread reductions in brain volume and was related to poorer memory and thinking skills, greater exposure to adverse life events, increased risk of self-harm, and metabolic and genetic changes. These findings were confirmed in a large general population sample as well as in people with current depressive symptoms. The results suggest that depression includes distinct brain-based subtypes, which may help explain differences in treatment response and guide the development of more personalised approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mental health illness that is common, a leading cause of disability worldwide, and the main precursor to suicide1. MDD is currently a clinical diagnosis, characterized by a persistent low mood and/or a diminished ability to experience usual feelings of pleasure, which is associated with a set of self-reported symptoms and clinical presentations, such as disrupted sleep, changes in appetite, low energy, feelings of guilt, and potential thoughts of death or suicide2. MDD is heterogeneous, clinical outcomes are variable, and there are no reliable predictors of treatment response at the individual level3,4.

MDD is currently classified as a disorder, which is defined by a set of symptoms, rather than a disease, which has an established neuropathological mechanism/s. Furthermore, it is unlikely that MDD is a single disease entity. There are multiple, partially overlapping neurobiological mechanisms, including chronic hyperactivation in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis which has been associated with neurobiological effects, namely hippocampal atrophy5, monoaminergic denervation impairing serotonin and noradrenaline innervation in the medial prefrontal cortex6,7, neuroinflammation associated with microglial activation in anterior cingulate and hippocampus8, and glutamatergic-neurotropic deficits that dampen signalling in limbic regions9. These mechanisms interact to produce the heterogeneous clinical and neuroanatomical profiles observed in MDD10.

While numerous neurobiological markers have been reported, none have yet achieved the accuracy and reproducibility required for diagnostic use in clinical practice. By applying advances in artificial intelligence to neuroimaging data, it has been possible to identify MDD from healthy participants at the individual level11,12 and further to delineate clusters within MDD with larger samples consisting of hundreds of participants13. However, regional structure and activity in MDD are altered by treatment, including medications, psychotherapy, and neuromodulation, and regional activity can vary with changes in depressive state, such as from a current depressive episode to a remitted state, in which there are few or no symptoms14. In treatment resistant depression, a clinical term referring to MDD characterized by continued symptoms despite at least two courses of treatment15, the neural correlates almost certainly reflect the effects of multiple treatments in addition to disease-related effects16.

In the COORDINATE-MDD consortium, we are investigating the individual-level neural patterns that characterize first-episode and recurrent MDD in medication-free participants in a current depressive episode17. Based on structural MRI data, we found two dimensions that showed distinct treatment responses to antidepressant medication18. Dimension 1 (D1) was characterized by preserved grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) volumes and showed a positive clinical response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant medication but not to placebo medication. In contrast, Dimension 2 (D2) was characterized by reduced GM and WM volumes and demonstrated limited clinical response to either SSRI or placebo medication.

In the present study, we externally validate the neuroanatomical dimensions in a general population as well as within a subset who were experiencing current depressive symptoms at the time of scanning. Leveraging the UK Biobank (UKB), a large-scale population cohort of over 500,000 adults with neuroimaging, behavioural, and genetic data19,20, we test the dimensions’ generalisability and examined their associations with domains which had previously demonstrated significant associations with depressive symptoms in UKB: cognitive functioning21,22, symptom burden23,24,25, neuroticism-related traits25,26, adverse life events and health-risk behaviours27, metabolic measures21,28, and genome architecture13. We integrate validation of the neuroanatomical dimensions with biopsychosocial measures in an independent, population-based assessment and delineate their multidimensional profiles. Dimension 2 shows widespread structural reductions together with poorer cognitive performance, greater exposure to adverse life events, higher rates of self-harm and suicide attempts, and a pro-atherogenic metabolic profile, alongside genetic signals linked to brain structure and neurodegenerative traits. Dimension 1 shows preserved brain structure and comparatively healthier cognitive, clinical, and metabolic profiles.

Methods

We adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines (see Supplementary Materials).

Participants

In the COORDINATE-MDD consortium, raw MRI data have been shared from international samples (n = 1384): medication-free first episode and recurrent MDD (n = 685), all in a current depressive episode of at least moderate severity, and healthy controls (n = 699). Prospective longitudinal data on treatment response were available for a MDD subset (n = 359). Treatments were either SSRI antidepressant medication (escitalopram, citalopram, sertraline) or placebo (COORDINATE-MDD consortium)17,18.

The UKB cohort represents a general population with recruitment taking place from 2006 to 2010 in 22 assessment centres in England, Wales and Scotland, with an age range of 40–69 years and total sample size of 500,000 participants29. All participants provided informed written consent, and ethical approval for the study was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West–Haydock (reference 11/NW/0382). Participants provided sociodemographic, cognitive, and medical information through questionnaires and physical assessments. A subset of participants completed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), beginning in 2014 (UKB Brain Imaging Documentation; http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). Imaging was conducted on a 3 T Siemens Skyra scanner with a T1-weighted MPRAGE protocol, resolution of 1 ×1 x 1 mm and a time to echo (TE) of 2000 ms20. UKB MRI data in the present study were acquired from 2014 to 2019 (n = 37,235 (19,736 women (53.0%)); mean age 64.14 years (SD = 7.50)).

Within the UKB general population cohort, a subset of individuals with current depressive symptoms indicating a major depressive episode (MDE) was identified using the following two UKB data fields: item 2050 (“frequency of depressed mood over the past two weeks”) and item 2060 (“frequency of unenthusiasm or disinterest over the past two weeks”), with endorsement of “More than half the days” (3) or “Nearly every day” (4) for either criterion, based on Stolicyn et al.30. Exclusion criteria included comorbid psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychotic symptoms), neurological (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy), and medical (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) disorders from ICD-10 diagnostic codes (UKB data field: 41202) (details in Supplementary Materials).

In UKB cohort, MRI scans were conducted during the imaging visit (Instance Index i2, 2014 onwards). Metabolic measures had been acquired during the baseline i0 timepoint (2006–2010) or at the i1 timepoint at the first repeat assessment (2012–2013). Cognitive, neuroticism-related traits, lifestyle and health-risk, and physical measures were acquired at the i2 timepoint. Symptom burden clinical measures, including depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), and adverse life events were acquired in the 2016 Online Mental Health Questionnaire (Supplementary Materials).

Image preprocessing and harmonization

All raw T1-weighted MRI data had been first manually assessed for head motion, image artifacts or restricted field-of-view for quality assurance. Images were corrected for magnetic field inhomogeneity, and a multi-atlas segmentation (MUSE) was applied to obtain brain volumes in 145 anatomical regions of interest (ROI)31,32. ROI volumes were linearly harmonized to correct for sex, and deep learning-based intracranial volume (DLICV), an ICV estimation method that uses deep learning algorithms to harmonize variability in volumetric measurements across MRI scan, and non-linearly harmonized to correct for age-wise differences33. Harmonization was performed independently in the UKB test dataset to prevent information leakage.

Population-based, out-of-sample validation in UK Biobank

We had applied the Heterogeneity through Discriminative Analysis (HYDRA) algorithm to derive brain-based dimensions of MDD from structural MRI data in the COORDINATE-MDD cohort18. HYDRA is a semi-supervised machine learning algorithm that identifies heterogeneity in clinical populations by constructing a convex polytope composed of k support vector machine (SVM) hyperplanes, each separating a distinct dimension of patient variation from the control group, resulting in a “1-to-k” mapping32,34. HYDRA was first trained on COORDINATE-MDD cohort, which included individuals with first-episode or recurrent MDD who were medication-free and experiencing a current depressive episode. A total of 259 structural volumetric features were extracted using the MUSE pipeline, encompassing regional gray and white matter volumes across cortical, subcortical, cerebellar, and brainstem regions. The optimal number of clusters (k = 2) was selected based on the highest Adjusted Rand Index (ARI = 0.569)18.

In a population-based, out-of-sample validation, we applied the pretrained HYDRA model (i.e., SVM weights and intercepts) to an independent sample from the UKB. The same 259 MUSE ROIs were derived for each participant in the UKB sample and used as input features to the trained model to obtain dimension membership scores for each UKB participant. For each UKB participant, expression scores for the two dimensions were computed using the trained linear decision functions:

\({Ei}={wiX}+{bi}\)

where X is the feature matrix (MUSE-derived brain region volumes) of UKB participants, and wi and bi are the weight and bias parameters derived from the trained COORDINATE-MDD model. These scores quantify the degree to which an individual “expresses” the anatomical profile associated with each dimension. No cross-validation was performed within the UKB dataset, as the trained HYDRA model (from the COORDINATE-MDD sample) was applied directly to the UKB data for out-of-sample validation.

Dimension membership (D1, D2) and expression scores (E1, E2) of the k = 2 dimensions for each participant were derived: 1) Dimension 1 (D1) was designated from E1 > = 0.3 and E2 <= −0.3; 2) Dimension 2 (D2) was E2 > = 0.3 and E1 <= −0.3; 3) combined D1 and D2 was E1 > = 0.3 and E2 > = 0.3; and 4) neither D1 or D2 was E1 <= −0.3 and E2 <= −0.3 (Fig. 1).

A Neuroanatomical MUSE features used for training and validation. These features represent brain regions used to classify dimensions in the COORD-MDD cohort and validate findings in the UKB dataset. B Training and validation workflow. (a) The pre-trained HYDRA model was developed using the COORD-MDD cohort, identifying two distinct dimensions: Dimension 1 (D1) and Dimension 2 (D2). (b) External validation was conducted by applying the pre-trained HYDRA model to the UKB dataset. Expression scores (E1 for D1, E2 for D2) were computed based on contributions to the respective dimensions. C Quadrant plots illustrating the application of pre-trained HYDRA model, trained on the MDD population, to the external UKB sample. The x-axis (E2) and y-axis (E1) represent the expression scores for each individual on Dimension 2 and Dimension 1, respectively. Dimension membership was determined based on these scores: individuals were assigned to Dimension 1 if E1 was greater than 0.3 and E2 was less than −0.3, to Dimension 2 if E1 was less than −0.3 and E2 was greater than 0.3, to the Mixed category if both E1 and E2 were greater than 0.3, and to None if both E1 and E2 were less than −0.3. All other individuals not meeting these criteria were classified as Margin. Panel A depicts the general UKB population (n = 37,235), while Panel B displays the subset of currently depressed participants (n = 1454). Source data for Fig. 1C(a) and C(b) are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

The two dimensions derived from HYDRA represent distinct anatomical patterns associated with major depressive disorder, as identified in the COORDINATE-MDD training sample18. The threshold was set a priori, based on Wen et al.13 in late life depression, which represents a modest but reliable departure from the separating hyperplane, in an approach to avoid over-fitting to the independent UKB cohort.

Neuroanatomical group comparisons

To evaluate differences in brain volumetric measures in dimension membership, a post-hoc analysis of MUSE features was conducted using one-way ANOVA for groups: 1) D1; 2) D2; 3) combined D1 and D2; and 4) neither D1 nor D2. The aov() function in base R and the Anova() function from the car package were used. False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was applied using the p.adjust() function in R to account for multiple comparisons with significance set at an FDR-adjusted threshold of p < 0.05. For each MUSE feature, the group means, and proportion of variance explained by the group differences was calculated. Heatmaps depict mean-centered, SD-standardized group differences (details in Supplementary Materials).

Phenotypic measures

Measures of cognitive, depressive and anxiety symptoms, neuroticism-related traits, adverse life events, self-harm and suicide, lifestyle factors, metabolomics and physical factors, were selected from UKB data fields according to established assessment frameworks. Detailed item descriptions, field IDs, and coding procedures are provided in Supplementary Tables 1–9.

Cognitive functioning

Cognitive functioning was assessed in the following seven domains21,35: executive function (trail-making test (TMT) A and B); fluid intelligence (verbal and numerical reasoning); working memory (backward digit span); verbal memory (paired associate learning); complex processing speed (symbol-digit substitution test) and nonverbal reasoning (matrix pattern completion). Poorer cognitive performance is indicated by higher scores in TMT, indicating increased time for completion, and lower scores in all other tests (Full descriptions are presented in Supplementary Materials).

Depressive and anxiety symptoms, neuroticism-related traits

Depressive symptom items were selected based on Howard et al.24 endorsement of at least one core symptom experienced for two weeks or more, namely persistent sadness or loss of interest. Additional six depressive symptoms reflecting functional impairments during the worst period of depression were included: tiredness, changes in sleep patterns, difficulty concentrating, feelings of worthlessness, thoughts of death, and weight changes.

Following Thorp et al.25 depressive symptoms were also selected from endorsement of the following items based on Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)36: recent lack of interest or pleasure in doing things, recent poor appetite or overeating, recent trouble concentrating on things, recent feelings of depression, recent feelings of tiredness or low energy, recent feelings of inadequacy, recent changes in speed or amount of moving or speaking, trouble falling or staying asleep or sleeping too much, and recent thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

Anxiety-related symptoms were selected based on Thorp et al.25 in the seven items: feeling nervous or anxious, feeling of foreboding, easy annoyance or irritability, restlessness, trouble relaxing, worrying too much about different things, inability to stop worrying over the last two weeks. Items are based on Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7)37.

Neuroticism-related traits were based on endorsement of twelve items following Okbay et al.26, which had been assessed from the 12-item Eysenck Personality Inventory framework38: mood swings, miserableness, irritability, sensitivity or hurt feelings, fed-up feelings, nervous feelings, worrier or anxious feelings, tense or highly strung, worrying too long after embarrassment, suffering from nerves, loneliness or isolation, and guilt feelings.

Adverse life events, self-harm and suicide, lifestyle items

Adverse life events were based on data fields assessing five items reflecting experiences of violence related to physical or sexual as an adult and three items related to childhood experiences of physical abuse, sexual molestation and feeling hated by a family member as a child. Self-harm and suicide attempts were assessed in individual items. Lifestyle items which had shown a significant association with suicide attempts in Zhang et al.27 were selected: ever smoked, current smoking, alcohol use, age of first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, and sleep disturbances.

Metabolomics

A total of 68 measures were examined, reflecting respiratory health, cardiovascular health, metabolic processes, lipid profiles, blood cell counts, lipid metabolism, and inflammation, which have been associated with depression28, biological age39 and metabolic syndrome21. Each measure was standardized, allowing beta coefficients to reflect standardized effect sizes. Positive beta coefficients indicate higher scores for D2 relative to D1, while negative coefficients indicate lower scores for D2 relative to D1 (Supplementary Materials).

Physical measures

A total of 14 measures were analysed to evaluate body composition, fat distribution, strength, and trunk mass20. These included body fat percentage, BMI, fat mass in the legs, arms, and trunk, and hand grip strength. Fat distribution was assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis, while grip strength was measured separately for each hand. All measures were standardized to ensure comparability, with beta coefficients representing standardized effect sizes. Positive beta coefficients indicate higher values for D2 compared to D1, whereas negative coefficients indicate lower values for D2 relative to D1 (Supplementary Materials).

Phenotypic associations

Associations with cognitive functioning, depressive and anxiety symptoms, neuroticism-related traits, adverse life events, self-harm and suicide, lifestyle factors, metabolomics, and physical measures were assessed for the two neuroanatomical dimensions (D1, D2). For cognitive measures, structured analyses were conducted using general linear models (lm function in R), adjusting for age, sex, and dimension membership (D1, D2). False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was applied at an adjusted significance threshold of p < 0.05. Outliers were handled by calculating z-scores based on the middle 80% of data values to obtain robust mean and standard deviation estimates; extreme outliers with |z | > 5 were excluded, and z-scores were recalculated. All dependent variables were standardized, and the resulting beta coefficients represented standardized effect sizes, with positive betas indicating higher scores for D2 relative to D1. Partial eta squared (η²) values were calculated using the eta_squared() function from the effectsize package to quantify the variance explained by group differences.

Across cognitive, metabolic, and physical domains, one-way ANOVAs were conducted to assess group differences among the four neuroanatomical groups (D1, D2, Combined D1 and D2, and Neither D1 nor D2). For traits showing significant group effects, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using t-tests with FDR correction. For categorical variables (e.g., symptom or behavioural items), Chi-squared tests (chisq.test()) were used to evaluate between-group differences, with standardized residuals and Cramér’s V computed to identify the strength and direction of effects. A Cramér’s V < 0.2 indicated a weak effect, 0.2–0.6 a moderate effect, and >0.6 a strong effect. Binary variables were coded as 1 = “Yes” and 0 = “No,” and missing responses were excluded from analyses. Detailed variable descriptions, field IDs, and coding are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) analysis and Gene set enrichment test

Imputed genetic data were downloaded from UKB in July 202140. Genotyped and imputed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) were pre-processed following a quality check protocol. We extracted and excluded participants with mismatched genetically identified sex and self-reported sex; chromosome aneuploidy; and related individuals (2nd-degree related individuals) via King software relationship inference41. We removed duplicate variants, variants with minor allele frequency less than 1%, variants with missing rate higher than 3%, variants which failed the Hardy-Weinberg test at threshold \(p < 1\times {10}^{-10}\). Participants with more than 3% missing genotypes were excluded. To adjust for population stratification, the first 40 principal components (PC) were derived using PLINK 2 (v2.0.0)42. Our quality control pipeline resulted in 30,376 samples and 6,288,959 variants for GWAS analysis in UKB participants with European ancestry were filtered. GWAS analyses were adjusted for age at imaging, sex, intracranial volume (ICV), and the first 40 genetic principal components. Genome-wide significance was defined at p ≤ 5×10⁻⁸, with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR used for downstream pathway and enrichment analyses.

We performed linear regression for D1 and D2 dimensional scores respectively on autosome variants. Age at imaging scan, sex, intracranial volume (ICV) and first 40 PC components were included as covariates. After calculating the association analysis via PLINK2, Functional Mapping and Annotation (FUMA) (https://fuma.ctglab.nl/tutorial#snp2gene) identified the significant independent SNPs having genome-wide significant threshold with \(p\le 5\times {10}^{-8}\) and are independent of each other at \({r}^{2} < 0.6\). Each candidate SNP was queried in the GWAS Catalog to check for any published associations with previous GWAS studies.

To evaluate the associations of the two dimensional scores significantly enriched for other phenotypic traits, we performed hypergeometric tests via FUMA GENE2FUNC analysis to test if genes of interest are overrepresented in any of the pre-defined gene sets (obtained from MSigDB, WikiPathways and reported genes from the GWAS-catalog). The input genes are those significant genes identified through FUMA’s SNP2GENE analysis of GWAS summary statistics.

To obtain insights into previously associated disease and drug targets of the genes, we used FUMA to map genes to OMIM ID, UniProt ID and drug ID of DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/) if available43.

Polygenic risk score (PRS) calculation

We calculated PRS for D1 and D2 dimensional scores using a split-sample approach in the UKB, randomly dividing participants into base and target datasets matched for age and sex. The base dataset was used to select SNPs and determine PRS weights, while the target dataset was used for PRS calculation. Quality control steps included: (1) removing duplicated and ambiguous SNPs, (2) excluding individuals with high heterozygosity, and (3) clumping the base dataset. PRS were generated for the target dataset using PLINK with the C + T (clumping-and-thresholding) method.

To identify the optimal PRS, we performed linear regression across a range of p-value thresholds (0.001, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5), adjusting for age at imaging scan, sex, ICV, and the first 40 genetic PCs. For each of the dimensional scores, we selected the PRS with the P value threshold that explains the highest phenotypic variance with the highest R2.

Polygenic risk score association analyses

We tested associations of PRS for D1 (PRS_D1) and D2 (PRS_D2) with cognitive, metabolic, physical, and binary traits (including depressive and anxiety symptoms, neuroticism-related traits, adverse life events, self-harm and suicide, and lifestyle items) in the UKB. PRS associations were tested using linear regression (continuous traits) or logistic regression (binary traits), adjusting for age, sex, ICV, and the first 40 genetic principal components. Multiple testing was controlled using Benjamini–Hochberg FDR within each trait domain (significance set at FDR-adjusted p < 0.05). Results are reported as β coefficients or odds ratios with corresponding p-values and shown in Supplementary Figs. 7–10.

Research domain criteria (RDoC)

In MDD participants from COORDINATE-MDD consortium18, we calculated RDoC scores to compare D1 and D2 across the various RDoC domains. Clinician rated scales with individual item level baseline data were not available in the UKB sample and RDoC analysis was not performed in the UKB sample.

The RDoC framework aims to understand mental illness according to domains which exemplify types of neurobiological functioning based on biological underpinnings44, consisting of six major functional domains: negative valence systems (NVS), positive valence systems (PVS), cognitive systems (CS), arousal / regulatory systems (ARS), sensorimotor systems (SS), and social processes (SP). Citrome et al45. identified HAMD and MADRS items which align with five RDoC domains (NVS, PVS, CS, ARS, SS), and Ahmed et al.46 defined three MDD phenotypes (core depression (CD), anxiety (ANX), and neurovegetative symptoms of melancholia) based on HAMD items to represent RDoC constructs, calculating a threshold for scoring across items to determine if an individual would be classified as positive or negative for each phenotype. We applied these items45,46, to examine RDoC domain phenotype in the present D1 and D2 classification18. For each phenotype, total HAMD and MADRS scores were transformed into a percentage of the total possible score for that phenotype to enable standardised comparison between HAMD and MADRS (Supplementary Materials). Additionally, we identified corresponding items on the MADRS scale to measure the three phenotypes that were measured using HAMD items by Ahmed et al.46 and created comparative thresholds to determine positive or negative phenotype classification (Supplementary Materials). Phenotype scores between D1 and D2 groups were analysed by general linear modelling ANOVA. Proportion of participants who were phenotype positive or negative at baseline was analysed by Chi-square test. P-values were corrected using FDR.

Sensitivity analyses

We repeated the external validation and phenotype associations in UKB subgroups which overlapped with the COORDINATE-MDD sample age range17,18: (1) having a lower age of 56 years and an upper age of 65 years (n = 6523), and (2) having an age range of ten years of the youngest UKB participant (ages 45 to 55 years) (n = 3112) (Supplementary Materials).

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.2). Between-group comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVAs and chi-squared tests for categorical variables, with post hoc pairwise t-tests where applicable. Linear and logistic regression models were used to examine associations with cognitive, metabolic, physical, and binary traits. All tests were two-sided, and significance was set at an FDR-adjusted p < 0.05 using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to account for multiple comparisons. Sample sizes were determined by the availability of participants meeting inclusion criteria in each dataset (COORDINATE-MDD: n = 1,384; UKB: n = 37,235). Replicates refer to independent participants in the respective cohorts. Sensitivity analyses stratified by age confirmed the reproducibility of the findings across subgroups.

Results

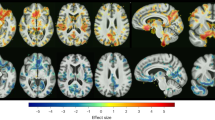

MRI volumetric measures

In UKB general population (n = 37,235), external validation revealed the following classifications: D1 (n = 6931), D2 (n = 10,262), combined D1 and D2 (n = 2931), neither D1 or D2 (n = 12,009), margins of D1 or D2 (n = 7102). The largest structural MRI volumes were observed in D1, followed by combined D1 and D2, neither D1 or D2 classification, and D2 (Fig. 2).

Heatmaps display mean regional brain volumes (mm³) for participants classified into Dimension 1 (left panel) and Dimension 2 (right panel). Each region of interest (ROI) is defined by the MUSE parcellation. Colour intensity corresponds to the mean ROI volume (mm³) within each group. Source data for Fig. 2 is provided in Supplementary Data 2.

In UKB individuals in a current major depressive episode (MDE) (n = 1454), external validation revealed the following classifications: D1 (n = 264), D2 (n = 442), combined D1 and D2 (n = 30), neither D1 or D2 (n = 453), margins of D1 or D2 (n = 265) (Table 1, Fig. 1, Supplementary Materials).

The brain regions that contributed most to D1 were in large cortical and cerebellar regions involved in multimodal and visuospatial association, including frontal lobe white matter, posterior cingulate, precuneus, superior parietal, superior and middle temporal, and cerebellum, while brain regions that contributed most to D2 were in more limbic-subcortical regions, including anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex, insular, amygdala, hippocampus, basal ganglia and thalamus (Supplementary Materials).

Cognitive functioning

In UKB general population, D2 showed significantly impaired performance as compared to D1 in all measures of cognitive functioning: fluid intelligence (β = −0.26, p = 5.73E-45), executive function, taking longer to complete TMT-A numeric path (β = 0.16, p = 2.65E-13) and TMT-B alphanumeric path (β = 0.12, p = 5.01E-08), working memory as measured by backward digit span task (β = −0.18, p = 7.76E-17), processing speed as measured by symbol-digit substitution (β = −0.14, p = 4.26E-11), nonverbal reasoning as measured by matrix pattern completion (β = −0.25, p = 8.33E-33), and verbal memory as measured by paired associate learning (β = −0.058, p = 0.012).

In UKB MDE cohort, D2 similarly showed significantly impaired performance as compared to D1 in: fluid intelligence (β = −0.25, p = 0.004), working memory as measured by backward digit span task (β = −0.23, p = 0.027), processing speed as measured by symbol-digit substitution (β = −0.19, p = 0.049), and nonverbal reasoning measured by matrix pattern completion test (β = −0.23, p = 0.033). There were trends towards significant differences in TMT-A (β = 0.21, p = 0.051) and TMT-B (β = 0.20, p = 0.053) in which D2 showed impaired performance relative to D1. There was no significant difference between groups in paired associate learning task (β = -1.56, p = 0.853).

Depressive symptoms

In UKB general population, in items related to core depressive symptoms, D2 participants reported higher rates of ‘prolonged loss of interest in normal activities’ (D1: 37.04%, D2: 40.07%; χ²(1) = 10.87, p = 0.00098, Cramér’s V = 0.030) and ‘prolonged feelings of sadness or depression’ (D1: 52.98%, D2: 55.53%; χ²(1) = 7.35, p = 0.0067, Cramér’s V = 0.025).

In associated items, D2 individuals were more likely to report ‘thoughts of death during the worst depression’ (D1: 48.44%, D2: 51.56%; χ²(1) = 7.07, p = 0.0078, Cramér’s V = 0.0336) and ‘weight change during the worst episode of depression’ (D1: 56.71%, D2: 60.90%; χ²(1) = 9.55, p = 0.0038, Cramér’s V = 0.025). In the PHQ-9 measures, D2 individuals reported greater prevalence of ‘recent poor appetite or overeating’ (D1: 16.46%, D2: 18.28%; χ²(1) = 6.43, p = 0.011, Cramér’s V = 0.023)

There were no significant differences between dimensions in other symptoms, in ‘feelings of worthlessness’, ‘difficulty concentrating’, ‘did your sleep change’, ‘feelings of tiredness during the worst period of depression’, or in PHQ-9 item symptoms.

In UKB MDE cohort, D2 participants reported higher endorsement of ‘thoughts of death during the worst period of depression’ (D1: 63.2%, D2: 77.2%; χ²(1) = 6.14, p = 0.013, Cramér’s V = 0.145), and within PHQ-9 items, D2 participants more frequently reported ‘recent changes in speed/amount of moving or speaking” (D1: 18.1%, D2: 27.8%; χ²(1) = 3.86, p = 0.049, Cramér’s V = 0.103). There were no significant differences in the remaining depressive symptom items.

Anxiety-related symptoms

In UKB general population, D2 individuals were more likely to report ‘recent inability to stop or control worrying’ (D1: 21.32%, D2: 23.93%; χ²(1) = 4.17, p = 0.041, Cramér’s V = 0.018). There were no significant differences in the remaining anxiety symptoms.

In UKB MDE cohort, there were no significant differences between D1 and D2 in anxiety symptoms.

Neuroticism-related symptoms

In UKB general population, D2 individuals were more likely to report ‘feeling tense/highly strung’ (D1: 11.33%, D2: 12.74%; χ²(1) = 7.34, p = 0.0067, Cramér’s V = 0.021), ‘nervous feelings’ (D1: 16.54%, D2: 19.21%; χ²(1) = 19.00, p = 1.31E-05, Cramér’s V = 0.034), and ‘suffering from nerves’ (D1: 13.83%, D2: 16.06%; χ²(1) = 15.25, p = 9.42E-05, Cramér’s V = 0.030). There were no significant differences in any other items.

In UKB MDE cohort, D2 participants more frequently reported ‘guilty feelings’ (D1: 53.6%, D2: 64.9%; χ²(1) = 6.34, p = 0.012, Cramér’s V = 0.109). There were no significant differences in other items.

Self-harm and suicide attempts

In UKB general population, D2 individuals showed a significantly greater endorsement of a history of suicide attempts (55.20%) compared to D1 (43.23%) (χ²(1) = 7.68, p = 0.006, Cramér’s V = 0.113) as well as a history of self-harm (4.61%) compared to D1 (3.80%) (χ²(1) = 4.41, p = 0.036, Cramér’s V = 0.019) (Fig. 3).

Participants in the D2 group reported significantly higher rates of self-harm, suicide attempts, and adverse life events compared to participants in the D1 group. Only participants who endorsed prior self-harm were asked whether they had harmed themselves with the intention to end their life. The percentages displayed correspond to the following samples: ever self-harmed (D1 n = 4847; D2 n = 6979); ever attempted suicide (D1 n = 229; D2 n = 375); physically abused by a family member as a child (D1 n = 5392; D2 n = 7583); felt hated by a family member as a child (D1 n = 5383; D2 n = 7580); experienced physical violence by a partner or ex-partner as an adult (D1 n = 5383; D2 n = 7579); and stopped from seeing friends or family by a partner or ex-partner as an adult (D1 n = 5025; D2 n = 7576). Between-group differences were assessed using two-sided χ² tests. Exact p-values: self-harm p = 0.036; suicide attempts p = 0.006; physically abused as a child p = 0.004; felt hated by a family member p = 0.0003; physical violence by partner/ex-partner p = 0.0004; stopped from seeing friends or family p = 0.043. Source data for Fig. 3 is provided in Supplementary Data 3.

In UKB MDE cohort, D2 individuals similarly showed a significantly greater endorsement of a history of suicide attempts in (73.8%) as compared to D1 (45.8%) (χ²(1) = 4.03, p = 0.045, Cramér’s V = 0.247), but there were no significant differences in history of self-harm.

Adverse life events, lifestyle and health-risk behaviours

In UKB general population, in items related to adverse life events, there was significantly greater endorsement in D2 compared to D1 in the following items: “experiencing physical violence by a partner or ex-partner” as an adult (D1 9.46%; D2 11.40%, χ²(1) = 12.36, p = 0.0004, Cramér’s V = 0.031), and “being stopped from seeing friends or family by a partner or ex-partner” as an adult (D1 7.38%, D2 8.37%; χ²(1) = 4.11, p = 0.043, Cramér’s V = 0.018); and in childhood events: “being physically abused by a family member” (D1 17.69%, D2 19.73%; χ²(1) = 8.39, p = 0.004, Cramér’s V = 0.025); and “feeling hated by a family member” (D1 15.64%, D2 18.09%; χ²(1) = 13.12, p = 0.0003, Cramér’s V = 0.032) (Fig. 3).

In UKB MDE cohort, there was significantly greater endorsement in D2 as compared to D1 in the following items: “experiencing physical violence by a partner or ex-partner” as an adult (D1 13.4%; D2 25.7%, χ²(1) = 7.84, p = 0.005, Cramér’s V = 0.142), and “being stopped from seeing friends or family by a partner or ex-partner” as an adult (D1 13.6%, D2 23.0%; χ²(1) = 4.78, p = 0.029, Cramér’s V = 0.112), and “sexual intercourse by partner or ex-partner without consent” as an adult (D1 9.0%, D2 16.5%; χ²(1) = 3.92, p = 0.048, Cramér’s V = 0.101); and in childhood events: “being physically abused by a family member” (D1 21.7%, D2 38.5%; χ²(1) = 11.52, p = 0.0007, Cramér’s V = 0.172), and “feeling hated by a family member” (D1 32.1%, D2 44.3%; χ²(1) = 5.32, p = 0.021, Cramér’s V = 0.118) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

In lifestyle and health-risk behaviours, in UKB general population, there was greater endorsement or previous or current “smoking status” in D2 (38.92%) compared to D1 (37.09%; χ²(1) = 5.78, p = 0.016, Cramér’s V = 0.018) and in “salt added to food” in D2 (43.31%) compared to (D1 43.09%; χ²(1) = 12.97, p = 0.0003, Cramér’s V = 0.028), while there was greater endorsement of “alcohol usually taken with meals” in D1 (74.21%) compared to D2 (72.43%) (χ²(1) = 3.97, p = 0.046, Cramér’s V = 0.020). In UKB MDE cohort, there were no significant differences between D1 and D2.

Metabolomics

In UKB general population, 39 (57.4%) out of the 68 metabolites tested showed a significant difference between D1 and D2 (FDR p < 0.05). D1 showed significantly increased levels compared to D2 in 16 metabolites. These included 2 measures of intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL) particles, 9 measures of large to very large high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles, forced expiratory volume and mean cell volume. Among fatty acids there was increased levels three fatty acids in their ratio to total fatty acids, including polyunsaturated fatty acids, omega-6 fatty acids and linoleic acid. D2 showed significantly increased levels compared to D1 in 23 metabolites. These include 13 large to extremely large, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles, systolic blood pressure, glycated haemoglobin, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and pyruvate. Among fatty acids there were significantly higher levels of total monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and its ratio to total fatty acids (Fig. 4).

Forest plot of 68 metabolic measures; with 39 showing significant group differences. The x-axis represents the beta value, where negative values indicate higher levels in D1 and positive values indicate higher levels in D2. Significant results are shown in blue and non-significant results in grey. D1 was associated with higher HDL and polyunsaturated fatty acids, while D2 showed higher VLDL, triglycerides, HbA1c, CRP, and pyruvate. Group differences were determined using two-sided independent-samples ANOVA with age and sex as covariates. Exact p-values (FDR-adjusted) are reported in Supplementary Table 16. Source data for Fig. 4 is provided in Supplementary Data 4.

In UKB MDE cohort, only forced expiratory volume (FEV1) was significantly higher in D1 compared to D2 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Physical measures

In UKB general population, D2 showed significantly higher levels compared to D1 in: leg fat percentage (right) (β = 0.052, p = 6.70E-08, η² = 0.052), leg fat percentage (left) (β = 0.046, p = 3.15E-07, η² = 0.046), body fat percentage (β = 0.050, p = 0.000655, η² = 0.050), arm fat percentage (left) (β = 0.059, p = 7.40E-05, η² = 0.059), and arm fat percentage (right) (β = 0.065, p = 1.19E-05, η² = 0.065). In contrast, D1 showed significantly higher levels compared to D2 in: hand grip strength (right) (β = −0.125, p = 2.01E-24, η² = −0.125), hand grip strength (left) (β = −0.115, p = 3.19E-21, η² = −0.115), trunk fat-free mass (β = −0.207, p < 1E−10, η² = −0.207), and trunk predicted mass (β = −0.204, p < 1E-10, η² = −0.204) (Fig. 5).

Forest plot of body composition and strength measures; several showed significant group differences. The x-axis represents the beta value, where negative values indicate higher levels in D1 and positive values indicate higher levels in D2. Significant results are shown in blue and non-significant results in grey. D1 exhibited greater hand grip strength and higher trunk fat-free and predicted mass, whereas D2 showed higher percentages of leg, arm, and body fat. Group differences were determined using two-sided independent-samples ANOVA with age and sex as covariates. Exact p-values are reported in Supplementary Table 16. Source data for Fig. 5 is provided in Supplementary Data 5.

In UKB MDE cohort, D2 similarly showed significantly higher levels compared to D1 in: arm fat percentage (right) (β = 0.161, p = 0.028, η² = 0.161), and arm fat percentage (left) (β = 0.152, p = 0.037, η² = 0.152), while D1 exhibited significantly higher levels compared to D2 in: trunk fat-free mass (β = −0.121, p = 0.028, η² = −0.121) and trunk predicted mass (β = −0.120, p = 0.028, η² = −0.120) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Genomic architecture

GWAS analysis identified 7 genomic loci significantly associated with D1 and 7 genomic loci significantly associated with D2 (significance level P-value < 5 × 10−8). 3 genomic loci associated with D1 and 3 associated with D2 had not been previously reported in association with any clinical traits in the National Human Genome Research Institute and European Bioinformatics Institute (NHGRI-EBI) GWAS Catalog47. GWAS analysis identified 10 independent significant SNPs associated with D1 and 9 associated with D2 (Fig. 6).

A E1 was significantly associated with 10 independent significant SNPs across 7 genomic loci. B E2 was significantly associated with 9 independent significant SNPs across 7 genomic loci. Independent significant SNPs are SNPs that passed the genome-wide significance threshold (two-sided p ≤ 5 × 10⁻⁸; red line) and are independent from each other with r² < 0.6. C QQ plots for E1 analysis. D QQ plot for E2 analysis. Source data for Fig. 6 is provided in Supplementary Data 6 and 7.

Five independent SNPs associated with D1 had previous reports of positive associations in NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog, indicating that carrying the risk allele has been linked with increased depressed affect48, schizophrenia49, brain volume in dorsolateral prefrontal, posterolateral temporal and superior temporal regions50, right hippocampal subfield CA3 (head) volume51, body fat percentage52, and acne53. Three independent significant SNPs associated with D1 had previous reports of negative associations with brain age (i.e. difference between predicted and chronological age)54, brain volume in orbitofrontal, superior parietal, and superior temporal regions, precuneus, and cortical surface regions50, as well as body mass index55. Four independent significant SNPs associated with D1 showed no previous associations in GWAS Catalog.

Two independent SNPs associated with D2 had shown positive associations in NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog with vertex-wise sulcal depth56, and whole-body fat free mass (UKB data field 23101)57, and non-glioblastoma glioma58. SNP rs9823492 has been associated with paired helical filament tau (PHF-tau), which is a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease59, and SNP rs4843547 has been associated with white matter microstructure measures60. Five independent significant SNPs associated with D2 showed no previous associations GWAS Catalog.

MAGMA-based tissue expression analysis for D1 revealed two significant associations: in cerebellum (p = 0.00031) and cerebellar hemisphere (p = 0.00035).

Polygenic risk score associations

The best-fit PRS for D1 used a p-value threshold of 0.2 (R² = 0.00235), and for D2, a threshold of 0.1 (R² = 0.00339). PRS for D1 showed positive associations with lipid-related traits in large and very large HDL subclasses, and with greater trunk fat-free and predicted mass. PRS for D2 was associated with lipids in small VLDL particles and monounsaturated fatty acids, and with lower trunk fat-free and predicted mass. No significant associations were observed with cognitive measures or other traits (Supplementary Figs. 7–10, Supplementary Materials).

Pathway and drug target enrichment for D1 and D2

Gene set enrichment analysis for D1 and D2 revealed shared associations with brain morphology, Parkinson’s disease, cortical surface area, waist-to-hip ratio (adjusted for BMI), alcohol use disorder, mean arterial pressure, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and blood pressure. D1 also showed enrichment for response to cognitive–behavioural therapy in major depressive disorder, while D2 was linked to diet-related traits (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Both dimensions shared druggable genes including AS3MT (linked to S-adenosylmethionine, used in Europe for depression, liver disorders, fibromyalgia, and osteoarthritis, and available in the US as a mood supplement), CRHR1 (diagnostic agent for ACTH-related disorders), NT5C2 (Hepatitis C treatment), and MAPT (therapies for acid reflux, allergies, and certain cancers). D1-specific druggable genes were linked to nutrient supplements and hormone therapy, while D2-specific genes related to nutritional supplements, varicose vein treatment, acetaminophen overdose, and antiseptic/disinfectant agents (Supplementary Materials).

Research domain criteria (RDoC) associations

In MDD participants from COORDINATE-MDD consortium18, individual item level baseline data were available in 426 participants from MADRS rating scale (CANBIND and Remedi, N = 130 (D1 n = 46, D2 n = 84)) or the HAMD rating scale (Oxford and EMBARC, N = 296 (D1 n = 148, D2 n = 148)). There were no significant differences between D1 and D2 in age or sex (D1: n = 194 (118 female), mean age 36.02 ± 12.87 years; D2: n = 232 (160 female), mean age 35.79 ± 12.57 years).

In RDoC core depression domain, D1 showed significantly greater scores compared to D2 (D1 mean = 0.594, D2 mean = 0.556, p = 0.037), while in sensorimotor systems domain, D2 showed significantly greater scores compared to D1 (D1 mean = 0.233, D2 mean = 0.315, p = 0.005). Negative valance systems showed a trend towards significance with D2 exhibiting greater scores than D1 (D1 mean = 0.395, D2 mean = 0.423, p = 0.052) (Supplementary Materials). There were no significant differences in positive valance systems, cognitive systems, arousal/regulatory systems, anxiety phenotype or neurovegetative symptoms of melancholia phenotype. Clinician-rated scales for depression severity were not available in the UKB cohort and RDoC scores were therefore not calculated.

Sensitivity analyses

Repeating the external validation in two UKB subgroups with overlapping ages from the COORDINATE-MDD sample: (1) having a lower age of 56 years and an upper age of 65 years (n = 6523), and (2) having an age range of ten years of the youngest UKB participant (ages 45 to 55 years) (n = 3112). In both subgroups, D1 and D2 individuals were identified and showed a similar pattern of results in cognitive functioning, self-harm, adverse life events history, as well as metabolomics (Supplementary Materials). In additional analyses adjusting for BMI (Supplementary Materials), the main findings were unchanged, indicating that BMI does not explain the distinct clinical, cognitive, and biological features of D2.

Discussion

Neuroimaging-based dimensions derived from first episode and recurrent MDD in our COORDINATE-MDD consortium17,18 showed a population-based, out-of-sample validation in the UKB general population cohort. We had found that D1 was characterised by relatively preserved grey and white matter volumes, while D2 showed reduced grey and white matter volumes18, which were associated with a pattern of cognitive impairments, increased adverse life events in adulthood and childhood, increased self-harm and suicide attempts, a pro-atherogenic lipid profile, characterised by a pattern of blood lipids linked to higher cardiovascular risk, such as elevated LDL/VLDL cholesterol and triglycerides, higher body fat and systemic inflammation compared to D1 in the out-of-sample validation. These patterns were observed both in a large cohort from the UKB general population and in individuals who had core depressive symptoms at the time of their brain scan.

Widespread cortical and cerebellar regions that support multimodal and visuospatial association contributed more strongly to D1, while limbic-subcortical structures implicated in affective and reward processing contributed more to D2. Similar profiles have been reported in functional connectivity patterns, with a more ventral attention hyper-connectivity with insomnia subtype and a subcortical and dorsal attention hypoconnectivity with anhedonia subtype in first episode depression61, as well as in a morphometric-gene analysis reporting a fronto-parietal cognitive control circuit with diffuse cortical thinning and a limbic–temporal social perception circuit marked by regional thickening62, suggesting a more cortical-dominant association network and a more limbic-subcortical affective processing network.

A pattern of cognitive impairments was evident in D2 relative to D1 in a wide range of domains from executive function, working memory, and processing speed to nonverbal reasoning. Brain volume has been associated with general cognitive functioning in which cognitive decline is linked with reduced grey matter volume63,64. In the present analysis, we observed a similar pattern of cognitive deficits in individuals who had endorsed current depressive symptoms at the time of their scan who were classified as D2 compared to D1. The findings suggest that the widespread subtle deficits in grey and white matter in D2 underlie the wide-ranging cognitive deficits observed in D2 compared to D1, which is observable in the general population, suggesting that dimension assignment is a trait feature as well as a state feature in individuals from the general population who had endorsed experiencing a current depressive episode18.

In the general population, D2 had a significantly greater history of self-harm and suicide attempts than did D1. In addition, trauma-related experiences, such as childhood abuse and exposure to interpersonal violence, were more prevalent among D2 than among D1 individuals. Cumulative grey matter reductions have been consistently observed in trauma-exposed individuals, suggesting a potential contribution to the regional deficits in the development of MDD in D2 individuals65.

With respect to metabolomics, D2 had a pro-atherogenic lipid profile, higher body fat, and impaired glucose metabolism, reflecting poorer metabolic health, whereas D1 had a healthier lipid metabolism. D2 was associated with higher levels of very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), chylomicrons, triglycerides, and cholesterol as compared to D1. D2 also exhibited significantly higher body fat percentages, including leg and arm fat, as well as overall body fat. This was accompanied by reduced muscle mass, as evidenced by lower trunk fat-free mass and trunk predicted mass, and diminished hand grip strength on both sides as compared to D1. This profile is commonly associated with increased cardiovascular risk and metabolic dysregulation, potentially linked to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity66. Importantly, sensitivity analyses adjusting for BMI indicated that these cognitive, metabolic, and physical differences between D2 and D1 largely persisted, suggesting that the distinct clinical and biological features of D2 are not solely attributable to body mass.

High triglycerides have been associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders67. Furthermore, D2’s higher pyruvate levels, a key glycolysis metabolite, suggest disrupted glucose metabolism, consistent with observations that elevated glucose levels are associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders67 and Lv et al.68 identified a relationship between increased body fat and higher risks of depression. Higher body fat percentages correlate with greater hormonal stress vulnerability (e.g., elevated cortisol levels), which in turn impairs cognitive performance under stress69, and is in itself associated with reduced regional brain volumes70,71. In contrast, D1 displayed a healthier lipid metabolism profile, with higher levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL). Elevated HDL levels, particularly in large and very large HDL particles, are indicative of better cardiovascular protection and reduced systemic inflammation, which have been found to be protective against psychiatric disorders67.

Consistent with the metabolic profile observed in D2, Lamers et al.72 had identified an “immuno-metabolic depression” (IMD) profile which is characterized by increased inflammatory markers and metabolic dysregulation, such as dyslipidaemia and higher body fat, and reduced physical fitness. The IMD profile was identified from the epidemiological population-based Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) and has been replicated in treatment-naïve adults with MDD73. Furthermore, longitudinal findings over six years observed a long-term persistence of high symptom burden in the IMD profile72. Our findings suggest that the limited effectiveness of SSRI antidepressant as well as placebo medications might be observed early in the course of illness in D2 dimension individual18. This highlights the need for additional treatment options to mitigate long term morbidity and improve clinical outcomes.

About 3% of the cohort consisted of participants who showed a combined D1 and D2 profile, in which there was generally intermediate cognitive performance relative to D1 and D2, with poorer performance in working memory compared to D1 and higher fluid intelligence that D2; tendency towards healthier body composition as in D1; no difference in metabolite or inflammatory measures as compared to D2 or neither D1/D2; reduced pulmonary function as compared to D1 but no significant difference compared to D1. About 30% of the cohort though was assigned to the neither D1/D2 group, in which cognitive performance, metabolic measures, pulmonary function and trunk fat-free mass was intermediate to D1 and D2, being worse than D1 and better than D2, reflecting an intermediate profile.

GWAS analyses revealed distinct genomic loci and independent significant SNPs that were uniquely associated with either D1 or D2 scores. For D1, a positive association was found with SNP rs6782581, which has a known negative association with BMI55. Grey matter volume is linked to BMI, with increased BMI (indicating being overweight or obesity) associated with reductions in grey matter, while normal BMI is linked with preserved grey matter70,71. However, rs6782581 has also been associated with a slight increase in body fat percentage (0.01%)52, which appears contradictory as this is also associated with reduced grey matter volume. Indicators of general obesity though, such as BMI or body-fat percentage, are less informative at predicting brain volumes than indicators of central obesity, such as increased waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), with increases associated with reduced grey matter volume74,75. Supplementary analysis indicated significantly larger WHR in D2 compared to D1 in the UKB general population. For D2, GWAS identified a positive association with SNP rs1926034 with previous studies linking this SNP to increased whole-body-fat free mass (all mass in the body that is not fat)57. D2 is characterized by reduced grey matter volume compared to D118, and Pflanz et al.75 found an that higher whole-body fat-free mass was associated with lower grey matter volume and total brain volume. The findings suggest that variations in genetic associations and body composition metrics contribute to the distinct profiles of D1 and D2.

D1 score demonstrated a significant negative association with SNP rs199505, which has been linked to an increased likelihood of experiencing a depressed effect48. Within the RDoC framework, D1 was associated with significantly higher core depression scores and lower sensorimotor system scores compared to D2. This pattern highlights the persistence of core symptoms in the D1 profile, potentially linking its neurobiological features to distinct genetic and phenotypic domains.

D2 score showed a negative association with rs12076373, a variant linked to vertex-wide sulcal depth56. Increased sulcal depth reflects enhanced cortical folding, which has been positively associated with cognitive ability and cortical volume76. Conversely, reduced cortical folding has been observed in MDD77. Cortical folding is closely tied with genetic processes56 and is predominantly completed before birth78, with sulcal patterns present at birth serving as predictors of neurobehavioral outcomes79. The negative association with D2 suggests a predisposition to reduced cortical folding, aligning with the reduced cortical volumes observed in D2 individuals.

Beyond single-variant associations, the genome-wide enrichment and PRS analyses provided converging evidence that the phenotypic contrasts between D1 and D2 have a genetic basis. Gene set enrichment for both dimensions highlighted traits related to brain morphology, psychiatric and neurological disorders, and cardiometabolic measures, consistent with the observed neuroanatomical, cognitive, and metabolic differences. Additional enrichment for response to cognitive-behavioural therapy in D1 and diet-related traits in D2 suggest possible treatment- and lifestyle-relevant pathways. PRS results mirrored these profiles: higher PRS of D1 was associated with lipid measures in large and very large HDL particles, greater trunk fat-free mass, and stronger grip strength, consistent with its healthier metabolic and physical profile80; higher PRS of D2 was associated with lipid measures in small VLDL particles, monounsaturated fatty acids, and lower trunk fat-free mass, aligning with its more adverse cardiometabolic profile81. These findings indicate that D1 and D2 differ also in their broader polygenic architecture.

While genes direct brain development, environmental experiences shape the emerging structures and their relationships with each other. The greatest increase in brain weight occurs from birth to 3 years and there is a further fivefold increase from 3 to 18 years82. However, childhood maltreatment has a pronounced impact on brain development, from grey matter deficits and cortical thinning in anterior cingulate/paracingulate and middle frontal regions83 to widespread microstructural white matter reductions, particularly in fornix, corpus callosum and optic radiations as well as altered brain activity in the default mode and central executive network and increased responsivity in the amygdala and anterior cingulate to socioaffective cues84,85. Childhood maltreatment refers to physical, sexual or emotional abuse or neglect and is associated with deleterious effects on cognitive and emotional functioning and increased risk of mental health disorders86. Structural deficits and functional alterations linked with childhood maltreatment are a potential vulnerability which might then interacts with stressful life events in adulthood leading to the development of MDD87. Our findings suggest a potential pathophysiological mechanism for D2 MDD whereby polymorphisms associated with reduced cortical folding reflect a predisposition to reduced cortical volumes that is exacerbated by childhood maltreatment, leading to cognitive impairments and an immuno-metabolic form of MDD in adulthood which is associated with increased rates of self-harm as observed in D2 individuals in UKB general population.

Limitations of the present study include the binary coding of variables and reliance on self-reported experiences that may have introduced potential biases, including recall inaccuracies or social desirability effects. Demographic characteristics of the UKB cohort tend to have relatively high socioeconomic status and limited ethnic diversity, which does not fully reflect the general population88. Several of the associations reached statistical significance because of the large sample size, while their corresponding effect size indicated small effects (<0.03) and thus have limited practical significance. However, large UKB cohorts do routinely yield such effect sizes for behavioural and psychiatric traits because these phenotypes are highly polygenic and multifactorial89, in which our observed magnitudes are in the expected range. As the same direction of effect was found across multiple fields, this suggests a coherent underlying signal which aligns with the larger effects. In UKB cohort, the MRI scans, cognitive, neuroticism-traits and lifestyle measures were acquired at the same timepoint, while metabolic measures were acquired at an earlier timepoint and history of adverse events and symptom severity at a later timepoint. The UKB cohort was an older age group (mean 64 years) than our COORDINATE-MDD cohort (mean 38 years) which may have introduced a domain shift18. However, sensitivity analysis stratified by age within the UKB cohort showed comparable findings in subgroups with overlapping age ranges. Although D1 and D2 dimensions were validated in the UKB cohort, about 30% of UKB participants had not been classified to either dimension, suggesting the possibility of additional dimensions. Due to the cross-sectional nature of both datasets, we were unable to assess their temporal stability of D1 and D2 classifications. Furthermore, while functional connectivity measures have been associated with subtype classifications in MDD16,61, the present analysis was limited to structural neuroimaging, which reduces our ability to fully capture the dynamic and network-level alterations in MDD. Integrating structural and functional measures has the potential to increase the precision in delineation of the biomarkers that comprise MDD.

Conclusions

In summary, two neuroanatomical dimensions were identified in medication-free individuals with first episode and recurrent MDD during a current depressive episode, in which D2 was characterized by widespread subtle deficits and showed limited treatment response to SSRI or placebo medication compared to D1. The present findings demonstrated generalizability in an out-of-sample, independent general population cohort. D2 showed further associations with poorer cognitive functioning, greater exposure to adverse life events, including childhood trauma, an increased history of self-harm and suicide attempts, a pro-atherogenic lipid profile, and genetic links to white matter microstructure and neurodegenerative traits. The findings suggest that D1 and D2 represent biologically meaningful dimensions underlying MDD, associated with distinct neurobiological mechanisms and treatment responses. This highlights the shared and distinct neurobiological mechanisms of these dimensions that are currently categorised under the same clinical diagnosis as well as their potential as biomarkers to aid in predicting treatment response and guiding treatment approaches.

Data availability

UK Biobank data are available to approved researchers through the UK Biobank Research Analysis Platform (UKB-RAP) upon application and approval by the UK Biobank Access Management Committee (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/)29. CAN-BIND data are available through Brain-CODE (https://www.braincode.ca/)90. EMBARC data are available via the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive (NDA; https://nda.nih.gov/edit_collection.html?id=2199)91. Original raw data contributed by consortium sites are available from the individual co-authors, and derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (C.H.Y.F. and C.D.) upon reasonable request. Source data for Fig. 1C(a–b) are available in Supplementary Data 1. Data supporting Fig. 2 are provided in Supplementary Data 2, Fig. 3 in Supplementary Data 3, Fig. 4 in Supplementary Data 4, and Fig. 5 in Supplementary Data 5. Source data for Fig. 6 are available in Supplementary Data 6 and Supplementary Data 7.

Code availability

The MUSE algorithm for image segmentation is available at https://www.nitrc.org/projects/cbica_muse31. The HYDRA algorithm is available at https://github.com/evarol/HYDRA32. The algorithm is available at https://github.com/evarol/MIDAS92. The following R packages were used: WebPower 0.8.6 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/WebPower/WebPower.pdf), effectsize 0.8.2, and ggplot2 3.4.0. (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/ggplot2.pdf).

References

James, S. L. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-5®). (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Fu, C. H. Y., Fan, Y. & Davatzikos, C. Addressing heterogeneity (and homogeneity) in treatment mechanisms in depression and the potential to develop diagnostic and predictive biomarkers. NeuroImage Clin. 24, 101997 (2019).

Fu, C. H. Y. & Costafreda, S. G. Neuroimaging-based biomarkers in psychiatry: Clinical opportunities of a paradigm shift. Can. J. Psychiatry 58, 499–508 (2013).

Sheline, Y. I., Wang, P. W., Gado, M. H., Csernansky, J. G. & Vannier, M. W. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 3908–3913 (1996).

Rajkowska, G. et al. Length of axons expressing the serotonin transporter in orbitofrontal cortex is lower with age in depression. Neuroscience 359, 30–39 (2017).

Radley, J. J., Williams, B. & Sawchenko, P. E. Noradrenergic innervation of the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex modulates hypothalamo-pituitary-ddrenal responses to acute emotional stress. J. Neurosci. 28, 5806–5816 (2008).

Setiawan, E. et al. Increased translocator protein distribution volume, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 268–275 (2015).

Duman, R. S. & Monteggia, L. M. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 1116–1127 (2006).

Fu, C. H. Y., Fan, Y. & Davatzikos, C. Widespread morphometric abnormalities in major depression: neuroplasticity and potential for biomarker development. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 30, 85–95 (2020).

Costafreda, S. G., Chu, C., Ashburner, J. & Fu, C. H. Y. Prognostic and diagnostic potential of the structural neuroanatomy of depression. PLoS One 4, e6353 (2009).

Sankar, A. et al. Diagnostic potential of structural neuroimaging for depression from a multi-ethnic community sample. BJPsych Open 2, 247–254 (2016).

Wen, J. et al. Characterizing heterogeneity in neuroimaging, cognition, clinical symptoms, and genetics among patients with late-life depression. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 464–474 (2022).

Enneking, V., Leehr, E. J., Dannlowski, U. & Redlich, R. Brain structural effects of treatments for depression and biomarkers of response: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Psychol. Med. 50, 187–209 (2020).

Thase, M. E. & Rush, A. J. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 58, 23–29 (1997).

Drysdale, A. T. et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat. Med. 23, 28–38 (2017).

Fu, C. H. Y. et al. AI-based dimensional neuroimaging system for characterizing heterogeneity in brain structure and function in major depressive disorder: COORDINATE-MDD consortium design and rationale. BMC Psychiatry 23, 59 (2023).

Fu, C. H. Y. et al. Neuroanatomical dimensions in medication-free individuals with major depressive disorder and treatment response to SSRI antidepressant medications or placebo. Nat. Ment. Health 2, 164–176 (2024).

Miller, K. L. et al. Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1523–1536 (2016).

Alfaro-Almagro, F. et al. Image processing and Quality Control for the first 10,000 brain imaging datasets from UK Biobank. NeuroImage 166, 400–424 (2018).

Qureshi, D. et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with neuroimaging and cognitive outcomes in the UK Biobank. Diab. Care 47, 1415–1423 (2024).

Colombo, F. et al. Multimodal brain-derived subtypes of Major depressive disorder differentiate patients for anergic symptoms, immune-inflammatory markers, history of childhood trauma and treatment-resistance. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 85, 45–57 (2024).

Davis, K. A. S. et al. Mental health in UK Biobank - development, implementation and results from an online questionnaire completed by 157 366 participants: a reanalysis. BJPsych. Open 6, e18 (2020).

Howard, D. M. et al. Genetic stratification of depression in UK Biobank. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 163 (2020).

Thorp, J. G. et al. Symptom-level modelling unravels the shared genetic architecture of anxiety and depression. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1432–1442 (2021).

Okbay, A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature 533, 539–542 (2016).

Zhang, B. et al. Identifying behaviour-related and physiological risk factors for suicide attempts in the UK Biobank. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1784–1797 (2024).

Amin, N. et al. Interplay of metabolome and gut microbiome in individuals with major depressive disorder vs control individuals. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 597–609 (2023).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLOS Med 12, e1001779 (2015).

Stolicyn, A. et al. Automated classification of depression from structural brain measures across two independent community-based cohorts. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 3922–3937 (2020).

Doshi, J. et al. MUSE: MUlti-atlas region segmentation utilizing ensembles of registration algorithms and parameters, and locally optimal atlas selection. NeuroImage 127, 186–195 (2016).

Varol, E., Sotiras, A. & Davatzikos, C. HYDRA: revealing heterogeneity of imaging and genetic patterns through a multiple max-margin discriminative analysis framework. NeuroImage 145, 346–364 (2017).

Fortin, J.-P. et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. NeuroImage 167, 104–120 (2018).

Hwang, G. et al. Assessment of neuroanatomical endophenotypes of autism spectrum disorder and association with characteristics of individuals with schizophrenia and the general population. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 498–507 (2023).

Fawns-Ritchie, C. & Deary, I. J. Reliability and validity of the UK Biobank cognitive tests. PLoS One 15, e0231627 (2020).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. & Williams, W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–616 (2001).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, S. B. G. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Junior and Adult) (Hodder and Stoughton Educational, 1975).

Mao, R. et al. Association of biological age acceleration with cardiac morphology, function, and incident heart failure: insights from UK Biobank participants. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 25, 1315–1323 (2024).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Manichaikul, A. et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867–2873 (2010).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Wishart, D. S. et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082 (2018).

Insel, T. et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 748–751 (2010).

Citrome, L. et al. Making sense of the matrix: a qualitative assessment and commentary on connecting psychiatric symptom scale items to the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 19, 26–32 (2022).

Ahmed, A. T. et al. Mapping depression rating scale phenotypes onto research domain criteria (RDoC) to inform biological research in mood disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 238, 1–7 (2018).

Sollis, E. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D977–D985 (2023).

Nagel, M. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat. Genet. 50, 920–927 (2018).

Trubetskoy, V. et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 604, 502–508 (2022).

Makowski, C. et al. Larger cerebral cortex is genetically correlated with greater frontal area and dorsal thickness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2214834120 (2023).

Liu, N. et al. Cross-ancestry genome-wide association meta-analyses of hippocampal and subfield volumes. Nat. Genet. 55, 1126–1137 (2023).

Martin, S. et al. Genetic evidence for different adiposity phenotypes and their opposing influences on ectopic fat and risk of cardiometabolic disease. Diabetes 70, 1843–1856 (2021).

Teder-Laving, M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies novel loci conferring risk of acne vulgaris. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 1136–1143 (2024).

Kim, J., Lee, J., Nam, K. & Lee, S. Investigation of genetic variants and causal biomarkers associated with brain aging. Sci. Rep. 13, 1526 (2023).

Huang, J. et al. Genomics and phenomics of body mass index reveals a complex disease network. Nat. Commun. 13, 7973 (2022).

van der Meer, D. et al. The genetic architecture of human cortical folding. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj9446 (2021).

Harris, B. H. L. et al. New role of fat-free mass in cancer risk linked with genetic predisposition. Sci. Rep. 14, 7270 (2024).

Melin, B. S. et al. Genome-wide association study of glioma subtypes identifies specific differences in genetic susceptibility to glioblastoma and non-glioblastoma tumors. Nat. Genet. 49, 789–794 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Genome-wide interaction analysis of pathological hallmarks in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 93, 61–68 (2020).

Zhao, B. et al. Large-scale GWAS reveals genetic architecture of brain white matter microstructure and genetic overlap with cognitive and mental health traits (n = 17,706). Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3943–3955 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Data-driven clustering differentiates subtypes of major depressive disorder with distinct brain connectivity and symptom features. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 219, 606–613 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Transcriptomic similarity informs neuromorphic deviations in depression biotypes. Biol. Psychiatry 95, 414–425 (2024).

Cox, S. R., Ritchie, S. J., Fawns-Ritchie, C., Tucker-Drob, E. M. & Deary, I. J. Structural brain imaging correlates of general intelligence in UK Biobank. Intelligence 76, 101376 (2019).

Lammer, L. et al. Impact of social isolation on grey matter structure and cognitive functions: a population-based longitudinal neuroimaging study. eLife 12, e83660 (2023).

Liu, R. T., Kraines, M. A., Massing-Schaffer, M. & Alloy, L. B. Rejection sensitivity and depression: mediation by stress generation. Psychiatry 77, 86–97 (2014).

Vekic, J., Stefanovic, A. & Zeljkovic, A. Obesity and dyslipidemia: a review of current evidence. Curr. Obes. Rep. 12, 207–222 (2023).

Chourpiliadis, C. et al. Metabolic profile and long-term risk of depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e244525 (2024).

Lv, X. et al. Body composition, lifestyle, and depression: a prospective study in the UK biobank. BMC Public Health 24, 393 (2024).

Mujica-Parodi, L. R., Renelique, R. & Taylor, M. K. Higher body fat percentage is associated with increased cortisol reactivity and impaired cognitive resilience in response to acute emotional stress. Int. J. Obes. 33, 157–165 (2009).

Cole, J. H. et al. Body mass index, but not FTO genotype or major depressive disorder, influences brain structure. Neuroscience 252, 109–117 (2013).