Abstract

Worldwide, women and girls continue to face unfair barriers to equal access to education, jobs, and healthcare. These barriers profoundly affect their health and well-being. One of the most overlooked injustices is the gender health gap, which corresponds to the unfair differences in health outcomes between women and men. This gap exists because most medical research on women’s unique health needs is under-researched, underfunded, and ignored due to wider global political and social forces. To change this, we need a coordinated effort across society, not just reforming healthcare. Here we discuss key methods to achieve this: putting more women in leadership roles, especially in politics and healthcare, to help shape fair health policies; supporting women’s education and economic independence to establish equal positions in their society so they can advocate for their right to equitable healthcare; raising public awareness to build collective action and tailor research to women’s health needs that can help close the long-standing gender health gap; and building healthcare systems that work for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Women and girls have historically faced unique barriers to their fundamental human rights, including sex discrimination, lack of education and employment opportunities, and domestic violence. This has resulted in inequities across most areas of healthcare, including drug discovery and development, as well as disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Worldwide, advancing the health of women and girls relies on progress across multiple United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), due to the interconnected nature of inequalities beyond health. However, global efforts to achieve gender equity and empower all women and girls by 2030 (SDG #51) are substantially off track. Based on current estimates, it will take 300 years to end child marriage, 286 years to close gaps in legal protection and eliminate discriminatory laws, 140 years for women to be represented equally in positions of authority and leadership in the workplace, and 47 years to achieve equal footing in national parliaments1. These issues differ across political, sociocultural, and healthcare ecosystems, putting women and girls at varying levels of risk for maternal mortality (e.g., worldwide, 800 maternal deaths occur daily due to childbirth complications and child pregnancy2), unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), delays in diagnosis and appropriate care across several diseases (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular, and Alzheimer’s), mental health issues, and violence rooted in gender inequality3,4.

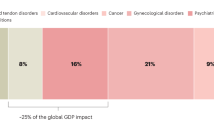

Health issues affecting women have been persistently neglected due to data biases, critical underfunding of female-related research, and a lack of policies to document and address the extent of the gender health gap. Recent studies reported a lag time of up to two years for women to be diagnosed with the same conditions as men, plus women are at significantly higher risk of experiencing an adverse drug reaction3. The severe disconnect between the burden of disease for women and funding for female-related research underscores a critical shortfall in healthcare investment and innovation5. Only 5% of funding for global research and development was allocated to female-related research in 2020, with 4% being allocated to women’s cancers and 1% to women-specific health conditions such as gynecological infections/conditions, contraception, fertility, maternal health, and menopause6. This continuing lack of investment in medical research for women and girls hinders the ability to accurately understand how sex influences the development of diseases and to evaluate the performance of new health technologies, including digital tools.

Furthermore, in today’s complex geopolitical environment, healthcare systems face increased financial pressures, especially after the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and cuts to funding for international aid programs leave women and girls increasingly vulnerable to worsening health due to geopolitical conflicts, climate change, food insecurity, and disease outbreaks7. Advancing the health of women and girls and closing the gender health gap requires a holistic, multistakeholder action plan that extends beyond the healthcare sector and confronts the root causes of inequities. A holistic approach to gender equity has been widely endorsed by international organizations (World Health Organization [WHO]8, Healthy People 20309), and other efforts promote gender-transformative policies in healthcare and decision-making by actively challenging gender norms and addressing power inequities between genders to achieve health equity10.

This Perspective was inspired by a discussion during an issue panel presentation at the 2023 European edition of The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) conference11. Each panelist (a co-author in this commentary) presented a unique perspective (pharmaceutical industry, research, global health, women’s health advocacy) on why healthcare ecosystems worldwide have fallen behind in considering strategies to overturn the historical marginalization of women and girls in pharmaceutical development, access to healthcare interventions, and health policy. The discussion sparked the need to advocate for an action plan to close the gender health gap, enhancing the need for female empowerment, advocacy, leadership, and sex-driven evidence generation strategies, particularly given recent global geopolitical developments.

We emphasize that the topic of gender equity crosses both the concept of sex as a biological variable (e.g., at the cellular level, related to anatomy, physiology, genetics, and hormones) and gender as a social variable (e.g., related to identity, roles/norms, relationships, and power).

We propose in this Perspective that, to bridge the gender health divide for women and girls, a coordinated effort and society-wide commitment that extends beyond the healthcare sector is required to mobilize a multisector action plan through the following main actions:

-

Elevating women to leadership positions in politics and healthcare organizations to shape inclusive health policies.

-

Empowering women to advocate for equal rights to access healthcare and enjoy a healthy life.

-

Raising societal awareness, building public support and demanding accountability for promoting health equity for women and girls.

-

Investing in gender-sensitive and transformative health research that produces an evidence base to understand differences and address access disparities.

Elevating women to leadership positions in politics and healthcare organizations to shape inclusive health policies

The need for diverse, female representation in political and healthcare leadership roles worldwide remains paramount. Although women comprise 70% of healthcare workers, men hold 80% of the positions that shape the agendas and drive health outcomes policy strategies, despite robust evidence of the positive impact of women as health leaders12. Evidence shows that female leaders are more likely to prioritize inclusive public health agendas, address gender-specific issues such as domestic violence, education of women and reproductive health, and lead with transparency and scientific rigor13. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, countries led by women experienced better health outcomes, with fewer absolute numbers of COVID-19 cases and related deaths14,15,16,17. Also, a lack of female representation in public policy-making when lockdowns and mobility restrictions were introduced overlooked the unique needs of women and girls experiencing domestic violence18,19. Specific examples in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) revealed that an increase in women occupying political seats was associated with a reduction in sex selection (the practice where female fetuses are selectively aborted in favor of male fetuses)20 and significantly improved access to contraceptives and reduced gender-based disparities21. The positive impact of female leadership is also influencing research outputs as projects led by female principal investigators were found to be associated with greater diversity and scientific reporting accuracy22. Increasing female representation in leadership is not only a matter of fairness, but a strategic imperative for better governance and health equity.

Action items: National governments should prioritize leadership programs for women and implement legal frameworks that ensure gender balance and transparent recruitment for parliamentary and executive public health committees and local governance activities. Political parties should actively support female candidates across all levels of leadership and adopt inclusive policy platforms that reflect gender equity. International non-governmental organizations, such as the UN and WHO have a critical role to play in promoting inclusive governance by offering technical assistance for women’s leadership initiatives, collaborating with higher education institutions to provide leadership training opportunities for women, supporting mentorship networks and systematically monitoring progress toward gender parity in decision-making positions. Female leaders can become ambassadors by promoting women for leadership roles in these positions.

Empowering women to advocate for equal rights to access healthcare and enjoy a healthy life

Equality for women remains an achievable but unfulfilled aspiration in many parts of the world23. Women continue to face systemic exclusion from politics, the labor market, and broader aspects of social participation. Fostering gender equity entails greater female participation in the social and political life of communities and an active role in decision-making. When women and girls are empowered to express their views through formal and informal means (e.g., voting, donating, or lobbying), the perspectives of marginalized groups gain legitimacy, and policymakers are more likely to respond. Evidence shows that when women hold positions of power, the whole society benefits through accelerated economic development for all, improved child health conditions and more inclusive governance24,25.

Consequently, the persistent exclusion of women from political life has serious consequences for female health and well-being. While policymakers are increasingly acknowledging the structural and deep-rooted barriers to women’s empowerment, progress on this issue remains slow. Environmental, economic, political, and social challenges continue to threaten hard-earned progress, underscoring the need for stronger national efforts to reform laws and demolish biases26. Alarmingly, the World Economic Forum estimated in 2023 that it will take 131 years to close the global gender gap, a large increase from the pre-COVID-19 projection of 99.5 years. This widening gap highlights the urgency of sustained, coordinated action to advance gender equality worldwide23.

Action items: National governments and non-governmental organizations including philanthropists should invest to ensure all girls have access to primary, secondary and tertiary education, especially those from underserved and marginalized communities. School systems should incorporate comprehensive health literacy programs into the curricula and, likewise ensure that health issues unique to women (e.g., menstruation) are not a barrier to a girl’s education (e.g., preventing attendance at school due to lack of sanitary products). Health policies should also address female-specific needs (e.g., pregnancy, menopause) in the workplace, promoting an environment in which women can thrive without choosing between their careers and personal health. Both the public and private sectors should financially invest in women-led innovation and entrepreneurships by increasing access to financial resources, equal pay, workplace protection for enabling work-life balance (e.g., childcare, parental leave) and supporting vocational and training programs to build confidence and skills.

Raising societal awareness, building public support and demanding accountability for promoting health equity for women and girls

At its core, advocacy seeks to shape policies, mobilize resources, and influence public discourse, all while confronting the persistent cultural, religious, and political barriers that limit women’s and girls’ access to comprehensive healthcare. Priority areas for advocacy include access to contraception, safe abortion services, and disease prevention strategies such as human papillomavirus vaccination27, all interventions that directly impact a girl’s and woman’s ability to pursue higher education and employment opportunities.

The violation of women’s rights and the resulting inequities between women and men are strongly related to differences in individual health-related risk behaviors, lifestyle options, access barriers, and systemic gender biases within health systems28. A longitudinal ecological study across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries (1990 to 2017) illustrated that population-level gender inequality significantly affects health outcomes including years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years29. When countries achieve greater gender equality, the whole population, both women and men, gain in health29. Therefore, advocacy for the health rights of girls and women enables the gender health gap to close at a population level, through elevating women’s health on the global agenda (e.g., initiatives led by the Global Alliance for Women’s health), mobilizing funding for female research and driving policy and legislative change (such as efforts led by the Society for Women’s Health Research).

Action items: Advocacy, healthcare and civil right groups can spearhead awareness campaigns to highlight the gender health gap and amplify the voice of all women, challenge harmful norms and address unconscious biases against women and girls. These campaigns can mobilize communities and decision-makers to advocate for women-inclusive health policies but also encourage male allies in these initiatives. Non-governmental organizations can establish transparent monitoring systems to assess progress in closing the women health gap and hold governments and other institutions accountable for commitments made towards women’s health progress. Communications and social media sectors can promote positive narratives around women’s leadership, health rights and highlight historical access barriers through storytelling, digital platforms to debunk myths and by promoting evidence-based guidance on health topics.

Investing in gender-sensitive and transformative health research that produces an evidence base to understand differences and address access disparities

Despite the call for rigorous scientific evidence in the research sector, the critical importance of gender-sensitive data and sex-disaggregated data in shaping health outcomes remains persistently neglected, deepening existing health inequities for girls and women30,31. For example, the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use still lacks dedicated guidelines for the inclusion of women in clinical research, continuing to refer to them as a “special subgroup” to be considered only when appropriate. Scientific journals inconsistently publish sex-disaggregated data on drug effectiveness and safety, and industry often fails to report sex or gender differences on product labels. Moreover, the health risks and patient experiences of ethnic minority women and those in marginalized or crisis-affected situations (e.g., war, natural disaster, pandemic, refugee, migrant) are routinely excluded from research32,33,34,35.

While some studies have highlighted sex-based differences in health outcomes, much of the earlier research, such as that on coronary heart disease, focused on men, despite the disease being the leading cause of death for women. Notably, 80% of women between 40 and 60 years of age have one or more risk factors for cardiovascular disease36. There are sex differences in adverse drug reactions with more women experiencing these adverse events than men, yet treatment clinical guidelines and medical protocols often rely on data derived from male-dominated clinical trials. For example, aspirin for coronary heart disease prevention was commonly prescribed to women based on dosages from clinical trials predominantly conducted in men37. Additionally, women frequently present with different, sometimes life-threatening, symptoms of heart attacks contributing to diagnostic delays and disparities in care37.

Although women live longer than men, they experience fewer healthy life years, a phenomenon called the health survival paradox38. When sex-specific data are collected, researchers rarely pay attention to the biological and social mechanisms and reasons behind these differences across the lifespan. For example, little is known about why women generally outlive men (with smaller gaps in low-income countries) or why women with specific conditions (such as diabetes) face a higher risk of death than men with the same condition39. The 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study revealed that disability-adjusted life year rates for females were significantly higher than for males for mental, neurological, and musculoskeletal disorders, with early years onset disparities particularly evident in conditions such as depression, anxiety, and headaches40,41. Beyond clinical outcomes, research and policies have largely failed to address the wider social determinants of health inequalities. Women’s disproportionate responsibility for unpaid domestic labor, for example, has been linked to their higher rates of depression and anxiety than men41.

Beyond research, there is no mandatory requirement to include sex disaggregated data in submissions for health technology products42. Current guidelines recommend proportional representation of girls and women in clinical studies based on disease prevalence43,44. Yet this often does not occur for serious diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and non-sex-specific cancers45. Moreover, focusing exclusively on prevalence overlooks sex-based inequities in diagnosis impacting disease progression, mortality, and its consequences (disabilities of disease, health impact, quality of life), issues rooted in historical biases in data collection. In addition, the underreporting of women-specific conditions such as cervical cancer46,47,48, anemia49, and postpartum hemorrhage50, has led to de-prioritization of investment and research funding.

Finally, with the growing adaptation of data-driven health technologies and digital tools in healthcare, a lack of robust female health data will perpetuate sex inequities in care and health outcomes51,52. For LMICs, in particular, mobile health interventions and artificial intelligence (AI) applications may resolve some of the geographical inequities, but unique challenges such as mobile phone ownership, gaps in digital literacy, and internet access may place women and girls at a disadvantage46,47,48. Research should consider socio-demographic characteristics, cumulative risks, and access barriers. International organizations, such as the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology [ISPE], are actively working to develop standards to address data biases and improve gender representation in health databases.

Action items: All stakeholders involved in healthcare (public health institutes, regulatory bodies, and policy-making agencies) must formalize the requirements for the standardized, systematic collection of sex-disaggregated data in public repositories, AI models, and development and testing of new treatments. Public health funding organizations and private investors should reform funding structures to prioritize women’s health research. Decision-makers should request sex-disaggregated data in submissions of new health technologies before reimbursement decisions are made. Public grants should prioritize academic and research institutions that invest in gender-sensitive health research including data biases and access barriers and enforce, medical training for sex-specific biology. Global health agencies need to fund data infrastructure and capacity-building to produce comprehensive knowledge centers for sex and gender statistics.

Summary

Closing the health gap for women and girls is not exclusively a health sector challenge. It requires a whole-of-society response and transformation. Key actions should start by collecting sex-disaggregated data throughout the health journeys of women, elevating their voices in political arenas and decision-making, and redesigning data systems to assess sex-related impact in regulation and reimbursement of health technologies.

Cross-sector partnerships, including policy-makers, advocacy groups, and trusted organizations, are essential to embed health equity into clinical development and care. National strategies and global alliances, such as the Global Alliance for Women’s Health and the Innovation Equity Forum, must connect public and private sectors to fund research and promote inclusive leadership.

Multistakeholder international organizations such as ISPE and ISPOR also have a unique role in healthcare advocacy, while regulatory bodies should adopt gender-inclusive guidelines (e.g., Sex and Gender Equity in Research [SAGER], Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting [GATHER])53 and follow the United States Food and Drug Administration’s lead in recognizing sex differences in clinical trials54.

The authors challenge all stakeholders to not only recognize the gender health gap but to lead with action by investing in advocacy calls, empowering women for leadership roles, applying intersectional lenses to data collection and policymaking, and ensuring health services are delivered with quality, equity, and dignity for all.

References

United Nations. Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Accessed July, 2024. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/.

World Economic Forum. Health equity for women and girls: Here’s how to get there. Accessed June 16, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/03/how-to-pave-the-way-towards-health-equity-for-women-and-girls/.

Westergaard, D., Moseley, P., Sørup, F. K. H., Baldi, P. & Brunak S. Population-wide analysis of differences in disease progression patterns in men and women. Nat. Commun. 10, 666 (2019).

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2025. Accessed October 17, 2025. https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/c992fbdc-11ef-43db-a478-7e7a195403ae/content.

Nature. Women’s health research lacks funding – these charts show how. Accessed June 16, 2025, https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-023-01475-2/index.html.

Funding research on women’s health. Nat Rev Bioeng. 2, 797–798 (2024)

UN Women. At a Breaking Point: The Impact of Foreign Aid Cuts on Women’s Organizations in Humanitarian Crises Worldwide. Accessed June 16, 2025, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/at-a-breaking-point-the-impact-of-foreign-aid-cuts-on-womens-organizations-in-humanitarian-crises-worldwide-en.pdf.

World Health Organization. Gender and health. Accessed December, 2025. https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1.

US Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. Accessed October 17, 2025, https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople.

Pederson, A., Greaves, L. & Poole, N. Gender-transformative health promotion for women: a framework for action. Health Promot. Int. 30, 140–150 (2015).

Sarri, G., Cheng R., F., Gabarro, M. S. & Jhutti-Johal, J. Gender and Health Equity in Health Care Decision-Making: How Women's Issues Continue to Be Neglected. ISPOR Europe. https://www.ispor.org/heor-resources/presentationsdatabase/presentation/euro2023-3741/17034 (2023).

Clark, J. The case for women’s leadership in global health. BMJ 388, r190 (2025).

Clark, J. & Hawkes, S. Overcoming gender gaps in health leadership. BMJ 387, q2768 (2024).

Triana, MdC. et al. Leader responses to a pandemic: the interaction of leader gender and country collectivism predicting pandemic deaths. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An Int. J. (2024);ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print) https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-08-2023-0266.

Dimitrova-Grajzl, V., Gornick, J. & Obasanjo, I. Leader gender, country culture, and the management of COVID-19. World Med. Health Policy 14, 773–797 (2022).

Garikipati, S. & Kambhampati, U. Leading the Fight Against the Pandemic: Does Gender Really Matter? Feminist Econ. 27, 401–418 (2021).

Chang, D., Chang, X., He, Y. & Tan, K. J. K. The determinants of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality across countries. Sci. Rep. 12, 5888 (2022).

Wenham, C., Smith, J., Morgan, R. & Gender, Group C.-W. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 395, 846–848 (2020).

UK House of Commons: Women and Equalities Committee. Unequal impact? Coronavirus and the gendered economic impact. Accessed May 2024, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/4597/documents/46478/default/.

Kalsi, P. Seeing is believing- can increasing the number of female leaders reduce sex selection in rural India? J. Dev. Econ. 126, 1–18 (2017).

Karimi, A. & Roy, D. Procurement for Empowerment: The Impact of Female Decision-Makers in Reproductive Health Supply Chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 34, 777–793 (2025).

Nielsen, M. W., Bloch, C. W. & Schiebinger, L. Making gender diversity work for scientific discovery and innovation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 726–734 (2018).

World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2023. Accessed June, 2024. https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2023/digest/.

Chattopadhyay, R. & Duflo, E. Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India. Econometrica 72, 1409–1443 (2004).

World Health Organization. Participation as a driver of health equity. Technical document. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289054126 (2019).

European Parliament. Gender aspects of the rising cost of living and the impact of the energy crisis Accessed June 16, (2025), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2024/754488/IPOL_STU(2024)754488_EN.pdf.

Slaymaker, E. et al. Trends in sexual activity and demand for and use of modern contraceptive methods in 74 countries: a retrospective analysis of nationally representative surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e567–e579 (2020).

Heise, L. et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet 393, 2440–2454 (2019).

Veas, C., Crispi, F., & Cuadrado, C. Association between gender inequality and population-level health outcomes: Panel data analysis of organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. eClin. Med. 39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101051 (2021).

Tannenbaum, C. & Day, D. Age and sex in drug development and testing for adults. Pharmacol. Res. 121, 83–93 (2017).

Shannon, G. et al. Gender equality in science, medicine, and global health: where are we at and why does it matter? Lancet 393, 560–569 (2019).

Elnakib, S., Fair, M., Mayrhofer, E., Afifi, M. & Jamaluddine, Z. Pregnant women in Gaza require urgent protection. Lancet 403, 244 (2024).

Kismödi, E. & Pitchforth, E. Sexual and reproductive health, rights and justice in the war against Ukraine 2022. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 30, 2052459 (2022).

Sosinsky, A. Z. et al. Enrollment of female participants in United States drug and device phase 1-3 clinical trials between 2016 and 2019. Contemp. Clin. Trials 115, 106718 (2022).

Liu, K. A. & Mager, N. A. Women’s involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications. Pharm. Pr. (Granada) 14, 708 (2016).

Manrique-Acevedo, C., Chinnakotla, B., Padilla, J., Martinez-Lemus, L. A. & Gozal, D. Obesity and cardiovascular disease in women. Int J. Obes. (Lond.) 44, 1210–1226 (2020).

Rothwell, P. M. et al. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 392, 387–399 (2018).

Van Oyen, H. et al. Gender differences in healthy life years within the EU: an exploration of the “health-survival” paradox. Int. J. Public Health 58, 143–155 (2013).

Clemens, K. K., Woodward, M., Neal, B. & Zinman, B. Sex Disparities in Cardiovascular Outcome Trials of Populations With Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diab. Care 43, 1157–1163 (2020).

Patwardhan, V., Flor, L. & Gakidou, E. Gender differences in global Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs): a descriptive Analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Popul. Med. 5, 2023 (2023).

Seedat, S. & Rondon, M. Women’s wellbeing and the burden of unpaid work. BMJ 374, n1972 (2021).

Ravindran, T. S., Teerawattananon, Y., Tannenbaum, C. & Vijayasingham, L. Making pharmaceutical research and regulation work for women. BMJ 371, m3808 (2020).

Scott, P. E. et al. Participation of Women in Clinical Trials Supporting FDA Approval of Cardiovascular Drugs. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 1960–1969 (2018).

International Conference on Harmonisation. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: Sex-Related Considerations in the Conduct of Trials. Accessed May (2024), https://admin.ich.org/sites/default/files/2019-04/ICH_Women_Revised_2009.pdf.

Yakerson, A. Women in clinical trials: a review of policy development and health equity in the Canadian context. Int J. Equity Health 18, 56 (2019).

GSMA JN. The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2024. Accessed May 6, 2025, https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/blog/the-mobile-gender-gap-report-2024/.

Kirkwood, E. K. et al. The Role of mHealth Interventions in Changing Gender Relations: Systematic Review of Qualitative Findings. JMIR Hum. Factors 9, e32330 (2022).

Jennings, L. & Gagliardi, L. Influence of mhealth interventions on gender relations in developing countries: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Equity Health 12, 85 (2013).

Merid, M. W. et al. An unacceptably high burden of anaemia and it’s predictors among young women (15–24 years) in low and middle income countries; set back to SDG progress. BMC Public Health 23, 1292 (2023).

Henriquez, D. D. C. A. et al. Clinical characteristics of women captured by extending the definition of severe postpartum haemorrhage with ‘refractoriness to treatment’: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 361 (2019).

Ibrahim, H., Liu, X., Zariffa, N., Morris, A. D. & Denniston, A. K. Health data poverty: an assailable barrier to equitable digital health care. Lancet Digital Health 3, e260–e265 (2021).

Ibrahim, S. A. & Pronovost, P. J. Diagnostic Errors, Health Disparities, and Artificial Intelligence: A Combination for Health or Harm? JAMA Health Forum 2, e212430–e212430 (2021).

Heidari, S. et al. WHO’s adoption of SAGER guidelines and GATHER: setting standards for better science with sex and gender in mind. Lancet 403, 226–228 (2024).

US Food and Drug Administration. Evaluation of Sex Differences in Clinical Investigations: Guidance for Industry. Accessed, (2025), https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/evaluation-sex-differences-clinical-investigations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Colleen Dumont for providing medical writing and editorial support in this manuscript and Lilia Leisle for literature review support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors equally contributed to the preparation of this manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.S. is employed and holds Cytel shares and non-paid Board positions at the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology and to a European-funded AI trial in breast cancer (https://cinderellaproject.eu/). M.S.G. has Bayer AG and GSK shares. R.F.C. owns stock in Pfizer and J&J.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Elizabeth Kirkwood and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarri, G., Soriano Gabarró, M.S., Cheng, R.F. et al. Intersectoral action to transform health equity for women and girls globally. Commun Med 6, 40 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01290-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01290-y