Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease is a growing global health concern, requiring kidney replacement therapy for survival. In Brunei, kidney failure incidence and prevalence are among the highest globally. Despite a peritoneal dialysis preference policy, uptake remains low, straining financial and human resources. With dialysis costs and demand for skilled healthcare workers projected to rise significantly, this study evaluates the cost effectiveness, budget impact, and human resource requirements of alternative dialysis policies to inform sustainable policy decisions.

Methods

A Markov model was developed to compare the costs and health outcomes of three policy options under the government and societal perspective: (i) Current Practice, (ii) Automated Peritoneal Dialysis (APD)-first policy, and (iii) Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD)-first policy, in which new patients start dialysis with either APD or CAPD respectively unless contraindicated. Budgetary and human resource impacts of each policy were estimated over a five-year period.

Results

Although both CAPD-first and APD-first policies show improved health and cost savings relative to the current policy, the APD-first policy is dominant (most cost effective) from the societal and government perspectives. Under the current policy, meeting the demand for Hemodialysis (HD) will require an additional 7 nephrologists and 230 HD nurses, whereas the APD and CAPD-first policies will significantly reduce workforce needs over the next 5-year period.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that Brunei’s current policy is not the most cost-effective or sustainable option. A peritoneal dialysis-first approach could generate significant cost savings and reduce additional demand for scarce nephrologists and dialysis nurses. Our results highlight the need to integrate workforce planning into economic evaluation to inform sustainable dialysis policies.

Plain language summary

Chronic kidney disease is a major global health issue, and patients with kidney failure need dialysis or a kidney transplant to survive. In Brunei, most patients receive in-center hemodialysis, in which a machine is used to filter waste and excess fluid from the blood. This is more expensive and requires more healthcare personnel than peritoneal dialysis, in which a special dialysis fluid is infused into the abdomen to absorb waste, and then drained out. This study compares different dialysis policies, to determine the most cost-effective and sustainable option. We found that where patients start with peritoneal dialysis (unless they have health issues requiring hemodialysis), healthcare costs are lower and there are improved patient health outcomes. This also reduces the demand for nephrologists and dialysis nurses, who are in limited supply in Brunei. The results highlight the importance of including workforce planning alongside cost effectiveness considerations for sustainable dialysis policies, especially in countries facing financial and human resource challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is a growing global health concern, ranking as the third fastest-growing cause of death worldwide and the only non-communicable disease with a persistent rise in age-adjusted mortality1. Its prevalence is steadily increasing due to factors such as aging populations, lifestyle changes, and the rising burden of diabetes and hypertension2. With kidney failure (KF), more than 85% of kidney function is lost. Although there is no definitive cure for KF, kidney replacement therapy (KRT), comprising dialysis and kidney transplantation, enables patients to live longer and more productive lives3.

There are key policy challenges associated with government reimbursement and provision of KRT, due to its high cost, the necessity for long-term investment, human resource requirements, and ethical considerations related to the high budget allocation for a relatively small patient population4. Decision makers must carefully evaluate the justification for public funding of KRT, as these resources could be allocated to other pressing healthcare needs. The prioritization of KRT services involves a complex decision-making process that must balance equity, feasibility, and cost-effectiveness. Economic evaluation can play an important role in this process, by providing insights into the trade-offs between costs and benefits of various policy options5. Several countries, including India6, Indonesia7, the Philippines8, and Thailand9, have conducted cost-effectiveness evaluations to support government decisions on renal dialysis policies. While these analyses help assess effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and budgetary impact, they often overlook the human resource requirements necessary for sustainable implementation, which may be particularly acute in low-income and middle-income settings, as well as in states with small populations.

This research was conducted at the request of the Brunei Ministry of Health to address concerns around the financial and operational sustainability of the dialysis programme. Similar to many countries, Brunei is facing a concerning rise in patients requiring KRT10. By 2022, the incidence and prevalence of KF reached 424 and 2,054 per million population, respectively, placing Brunei among the top three countries globally for KF incidence10, with the world’s highest proportion of incident KF cases caused by diabetes, accounting for nearly three-quarters of all new diagnoses10. Currently, the Brunei government offers in-center hemodialysis (HD), automated peritoneal dialysis (APD), continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), and kidney transplantation. While around 5% of kidney failure patients have received transplants, the majority rely on dialysis11. To address rising costs and high personnel requirements for HD, the government introduced a peritoneal dialysis (PD) preference policy in 201412, under which priority is given to PD counseling ahead of HD and trainings are provided to nephrologists to insert a PD catheter to reduce waiting time13. Despite the policy, PD uptake has remained suboptimal over the past 10 years, with over 85% of patients initiating dialysis on HD12.

Dialysis services currently account for 5–10% of Brunei’s healthcare budget even though less than 0.01% of the populations require dialysis in 2023, and the budget is projected to exceed 20% by 203512. Additionally, workforce shortages—including only six nephrologists nationwide and a limited supply of dialysis nurse—further strain the system, especially given the absence of a local nephrology training program12. Although the government fully funds dialysis treatments and allows patients to choose their preferred dialysis modality, the rising incidence of kidney failure, coupled with limited healthcare professionals and infrastructure, raises concerns about the long-term financial and operational sustainability of the current policy.

In this context, we aim to evaluate the cost-effectiveness, budget impact, and human resource requirements of alternative dialysis policies in Brunei. Beyond informing the national dialysis policy in Brunei, our study underscores the benefit of integrating workforce availability into KRT policy discussions, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Our findings suggest that the current policy is not the most cost-effective or sustainable option, and that a peritoneal dialysis-first approach could generate significant cost savings and reduce additional demand for scarce nephrologists and dialysis nurses.

Methods

Methods overview

This study employed a cost-utility analysis to evaluate the lifetime costs and health outcomes of three KRT policy options selected by key government officials and healthcare professionals. The analysis was conducted from both government and societal perspectives, with outcomes measured in life years (LYs) and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Costs included direct medical expenses as well as direct non-medical and opportunity costs incurred by patients and caregivers. Budget impact analysis and human resource requirements were conducted to estimate the financial and workforce implications of each policy option, based on the main economic evaluation. This study follows the Nature Reviews Nephrology evidence-based guideline on using economic evidence to inform kidney failure policies14 and reporting followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS)15.

Policy interventions and comparator

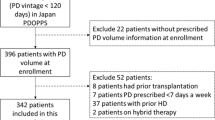

The two policy interventions considered in this study are an APD-first policy, in which eligible KF patients initiate dialysis with APD, and a CAPD-first policy, in which they start with CAPD. The assumption for both policy interventions is that 70% of eligible patients would initiate dialysis on PD while the rest of the patients still start with HD. This assumption is based on data from Thailand’s PD-First policy, which required all eligible

KF patients to begin dialysis with PD unless a medical condition prevented them from doing so, achieving a peak PD incidence of 70%16. Although both policies would likely involve a mix of APD and CAPD in practice, this study examines whether significant differences between the two warrant a preference for one modality over the other.

The comparator is the current policy, in which 87.5% of incident dialysis patients receive HD, 12.1% APD, and 0.4 % CAPD based on the Brunei Dialysis and Transplant Registry (BDTR) 202317. In Brunei, HD is provided in dialysis centers, with patients undergoing thrice-weekly sessions managed by nephrologists and nursing staff. APD and CAPD are home-based PD options, with APD using a machine for automated overnight exchanges and CAPD requiring manual exchanges multiple times daily.

Model structure

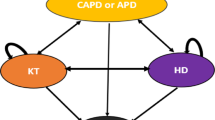

A Markov model was developed in Microsoft Excel simulating a hypothetical cohort of adult KF patients with an average age of 55 years, in accordance with local registry data11. The model structure was adapted from a previous study by Teerawattananon Y et al9. (Fig. 1). The model captured transitions between mutually exclusive health states (HD, APD, CAPD) and death, to assess cost and outcomes over a patient’s lifetime5. Each health state has a substate for complications except death.

In the model, the proportion of patients starting treatment with either APD, CAPD, or HD depends on the policy being modelled (i.e. current practice, CAPD-first, or APD-first). The model has a one-year cycle length. At the end of each cycle, patients either stay in the current state, transition to a different type of dialysis, or move to the death state. Complications in each health state are modeled based on the annual rate of complications specific to that state. We applied a lifetime horizon, meaning that the costs and health outcomes are accrued by patients in the model until death. Future costs and health outcomes were discounted at a rate of 3.5% in accordance with local stakeholder consultation.

Parameters

Parameters were taken from national databases, primary data collection, and international literature review. All parameters are shown in Supplementary Data.

Rate of complications

The rate of complications for each type of dialysis was obtained from the 2023 BDTR data11. Complications included significant dialysis-related infections such as peritonitis for APD and CAPD; catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI), blocked arteriovenous fistulas (AVF) and blocked tunneled dialysis catheters for HD; as well as hospitalizations, cardiovascular issues, and other complications for all HD, APD, and CAPD patients11.

Transitional probabilities

Annual transitional probabilities for switching between different types of dialysis and for death were obtained from the BDTR 2023 data11. Due to a very small number of patients transitioning from HD or APD to CAPD, transitions to CAPD were assumed to have a probability of 0.01 based on consultations with 2 nephrologists from Brunei. In the absence of patient-level longitudinal data (time-to-event-specific data) for survival estimates in the BDTR, annual probability of death for HD, APD and CAPD was calculated using aggregated local data with a weighted average, assuming a constant rate across all dialysis and time periods.

Cost

All cost data were adjusted to 2023 Brunei dollar (BND) by applying purchasing power parity and local consumer price index, as recommended by Turner et al18.

Direct medical costs

To estimate annual maintenance costs for APD and CAPD under the APD-first and CAPD-first policies, we circulated a request for prices to three suppliers, two of whom responded with volume-based price offers. Our analysis applied the price in the lowest offer received for APD and CAPD respectively for the PD-first policies. For the comparator, the current price paid by the Brunei government was used. Costs associated with treating complications were taken from a study in Singapore by Yang et al as both countries are high-income in the region with the same currency exchange rate19. A detailed list of resource items for direct medical cost is provided in Table S1.

Direct non-medical costs

Direct non-medical costs included electricity cost associated with APD and travel cost to the dialysis center for HD patients, as based on local expert opinion. Direct non-medical costs for CAPD were not included, as this modality does not require electricity or patient travel to a dialysis center.

Opportunity costs

The opportunity costs included potential income loss for patients and their caregivers for HD, as well as for caregivers providing care to patients at home for APD/CAPD. Opportunity costs were collected through an online, self-administered patient survey with informed consent obtained from all participants(N = 31). The survey was adapted from a Taiwanese study by Tang et al20, as it utilized a similar study design and setting (multicenter, cross-sectional survey of adult dialysis patients receiving HD or PD for more than three months). The survey was provided in both English and Malay. The opportunity costs were valued using average hourly wages from the 2023 Brunei Labour Force Survey21. It was assumed that 50% of HD patients were employed when estimating opportunity costs. For HD caregivers, we assumed that half were present for the full dialysis journey, including dialysis time with the patients, while the other half only assisted during travel to the HD center. For APD caregivers, based on consultation with a nephrologist in Brunei, it was estimated that they provided 30 minutes of assistance per day, whereas CAPD caregivers spent approximately 2 hours per day. Methods to estimate opportunity costs are provided in Supplementary data.

Health utilities

Utility scores were derived from a cross-sectional EQ-5D-5L survey by Koh et al22., conducted among dialysis patients in Brunei who participated in the abovementioned patient survey, with informed consent obtained. The Malay version of the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire and its value set were used23. While the Malay version of EQ-5D-5L has not specifically been tested for use among dialysis patients in the Brunei population, it is assumed to be acceptable given the geographical proximity and because the majority of kidney failure patients in Malaysia also have diabetes12. Due to the small sample size of CAPD patients in the study (because very few patients utilize CAPD in Brunei), the utility values of APD and CAPD were averaged. We explored different utility values in sensitivity analysis.

Model analysis

Base case analysis

The comparative cost-effectiveness analysis was assessed in terms of incremental cost per LY gained and incremental cost per QALY gained. However, as there was no difference in survival between HD or PD from the renal registry data, QALY was the main measure for the analysis. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the ratio of the difference in costs to the difference in QALYs through pairwise comparison24.

Sensitivity analysis

One-way deterministic sensitivity analysis was carried out by varying one parameter at a time while holding all others constant to identify which parameters significantly impacted the Net Monetary Benefit (NMB). Probabilistic sensitivity analysis using a Monte Carlo simulation with 9,604iterations (calculated to achieve 95% confidence that the median would fall within the 49th–51st percentile) was conducted to evaluate the impact of parameter uncertainty. For cost parameters without information on standard errors, we used 20% of the mean value. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) was generated to show the probability that an intervention policy is the most cost-effective option across different willingness to pay (WTP) thresholds25(Figure S1).

Value of information analysis

The objective of the Expected Value of Partial Perfect Information (EVPPI) analysis was to identify which model parameters contribute most to decision uncertainty and to inform priorities for future evidence generation. EVPPI was estimated using the Sheffield Accelerated Value of Information (SAVI) website tool26, using a 10-year decision-relevant time horizon and a WTP of 45,102 BND per QALY. Two parameters-probability of patients choosing CAPD under the current practice, and proportion of HD patients attending dialysis center (from opportunity costs of HD calculation) - were excluded due to insufficient variation (<5 distinct values) in the PSA simulations.

Resource use

Budget impact analysis

Budget impact analysis was undertaken to estimate the financial implications of adopting each policy option, calculated over a 5-year period. In line with renal registry data from BDTR 2023, we assumed a new cohort of 273 dialysis patients per year11, which accounts for incidence and death rate. We used the Ministry of Health perspective with 0% discounting.

Human resource requirements

We conducted demand-side analysis using a provider-to-population model to estimate the number of additional nephrologists and renal nurses to manage new dialysis patients over the next five years27. Since Brunei has a small geographical area with two-thirds of the population concentrated in and around the capital city, the provider population model was considered an appropriate approach, as absolute number (and not distribution) of healthcare personnel was important for policy and epidemiology of kidney failure in Brunei was not expected to change substantially over the next 5 years. In brief, we assumed the current ratio of nurses and nephrologists to be the ideal ratio of healthcare workers per dialysis patient. For each policy option, we estimated additional healthcare worker time required to accommodate an additional 273 patients per year, adjusting for the annual death rate based on 2023 incidence and mortality data. The model does not account for staff turnover and assumes no excess capacity within the system to accommodate additional patients.

Model validation

Face validity of the model structure and data sources was evaluated through three consultations with patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals (including nephrologists, and dialysis nurses), and representatives from pharmaceutical companies, at the study proposal stage. Parameter values and assumptions were reviewed and validated through a series of discussions with senior nephrologists and health economists in Brunei, throughout the 6-month course of the project, and all contributors involved in this study are co-investigators of the study. Technical verification was also carried out using TreeAge Pro software, applying the same data and assumptions for the analysis.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol, including ethics submission for primary data collection (opportunity costs, EQ-5D-5L surveys) as well as for accessing the BDTR data, was approved by Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (MHREC) in Brunei Darussalam (MHREC/MOH/2024/10(1). The approval covers both access to the BDTR data, and patient data collection through the surveys, with informed consent obtained from all survey participants. BDTR data are collected as part of the routine data collection process conducted by the Ministry of Health in Brunei Darussalam. The BDTR dataset used in this study is fully anonymized and publicly accessible. No identifiable personal information is included in the dataset, and all analyses were conducted using de-identified records. Because the data are anonymized at the source and released for secondary research purposes, individual patient consent was not required under local ethical guidelines.

Results

Cost effectiveness analysis

Both the APD-first and CAPD-first policies incurred lower costs with more health benefit than the current policy (Table 1). The benefit in terms of cost reduction was most pronounced from the societal perspective, due to reduced travel costs, as well as saved caregiver time and opportunity cost. From the government perspective, the ICER for APD-first policy was BND −582,300 per QALY gained and from the societal perspective, the ICER was BND −837,200. From both perspectives, the APD-first policy had the same health benefit as a CAPD-first policy but with greater cost savings due to lower maintenance cost and opportunity costs.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using the actual utility values for APD and CAPD from the survey (i.e. not average), which yielded results consistent with the base-case analysis (Table S5). Similar analysis was conducted using the annual maintenance costs of APD and CAPD based on the prices paid by the government for direct medical cost estimations to ensure that the base case analysis was not biased toward supplier-offered prices, which are primarily driven by volume-based price offers. The results were consistent with the base case analysis (Table S6).

The results of one–way sensitivity analysis indicate that utility, annual maintenance costs for HD/APD, annual probability of dying, and the probability of patients choosing HD under the current policy had the greatest influence on cost effectiveness (Figs. S2 and S3). However, under all deterministic sensitivity analyses, the APD-first policy was most cost-effective.

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis highlighted a high level of uncertainty in the results (Fig. 2 with corresponding raw data included in the supplementary data file, Sheet “PSAscatterplot”). There was a 56% probability for APD-first and 51% probability for CAPD-first that the intervention had more QALYs gained and lower costs than the current policy. PD first policies did not always provide additional health benefits when accounting for all parameter uncertainty, with 37% and 36% of simulations showing lower health outcomes for the APD-first and CAPD-first policies respectively compared to the current policy. However, the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve showed that an APD-first policy had the highest likelihood of being cost-effective across a wide range of willingness to pay thresholds (Fig. S1). Although the cost-effectiveness plane shows a spread, the CEAC remains relatively flat because the differences in this analysis are driven mainly by cost parameters. The survival data were identical across all three dialysis modalities, and the utility values were the same for APD and CAPD, with minor differences for HD. These results are consistent with the analysis re-run by TreeAge Pro software (Table S8 and S9, Fig. S4).

A non-zero EVPPI indicates that collecting additional data may change the optimal result. In this analysis, parameters with non-zero EVPPI included the annual maintenance cost for CAPD/ APD with new price, annual cost of treating APD complications, utility for APD, annual rate of having complications among APD patients, annual maintenance cost for HD, annual probability of dying among APD patients, and annual probability of switching from APD to HD (Table S7). Notably, some of the most influential parameters such as the maintenance cost set by the manufacturer are unlikely to be improved through further data collection, highlighting the need for price negotiation to mitigate decision uncertainty. As most non-zero EVPPI parameters relate to APD, these findings support prioritizing additional data collection on APD-related utility, costs, complication rates, and mortality to reduce future decision uncertainty.

Resource use

In the budget impact analysis, both APD-first and CAPD-first policies provide significant budget savings over a five-year period, with the APD-first policy saving approximately BND 29 million and the CAPD-first saving BND 18 million compared to the current policy (Fig. 3). This amounts to budget savings of 20% for the APD-first policy and 12% for the CAPD-first policy relative to the current policy, with budget savings increasing each year.

Under the current policy, we estimated that 7 additional nephrologists and 230 additional HD nurses would be required to meet the demand for HD (Tables S2–S4). In contrast, the APD and CAPD-first policies would require 5 additional nephrologists and around 100 additional nurses for HD service provision, alongside 2 additional nurses for APD/CAPD.

Discussion

In this study we considered the cost-effectiveness, budget impact, and human resource requirements of policies aiming to improve the financial and operational sustainability of the dialysis programme in a country with severe human resource constraints. The study results suggest that transitioning to a PD-first policy, in which nearly all patients, except those with contraindications, begin with either APD or CAPD, could yield significant cost savings for both the government and households. These findings align with the results from other countries such as Indonesia7, the Philippines8, and Thailand9, where a PD-first policy resulted in lower direct medical cost compared to the HD-first policy. Furthermore, this study supports previous research highlighting the significant out-of-pocket costs for households of HD patients. Despite Brunei’s small size, good travel infrastructure, and subsidized petrol, the indirect costs such as travel time, caregiving, and opportunity cost create a significant financial burden.

To our knowledge, this study is the first economic evaluation of KRT policies to incorporate human resource requirements. In the Brunei context, this added a critical dimension to understanding the feasibility and sustainability of different dialysis policies. This issue is particularly relevant for a small healthcare systems and low-income settings, which often face significant constraints in training and retaining local healthcare professionals28. Given the limited workforce, any policy that improves resource allocation from the perspective of available budget and healthcare personnel can have substantial benefits. Both the APD-first and CAPD-first policies contribute to this goal by decreasing the need for frequent patient visits to dialysis centers. As a result, fewer specialized healthcare workers are required for in-center dialysis management, allowing the healthcare system to allocate its workforce more efficiently while maintaining or even improving patient care. However, it should be noted that the human resource estimation approach we applied may not be applicable to other contexts, particularly those with heterogeneous distribution of healthcare workers or with mixed public-private service provision27.

Our study has several limitations. First, due to the lack of time-to-event survival estimates in the BDTR, we applied the same death rate across all dialysis modalities, emphasizing the need for routine data collection on survival estimates to enhance future accuracy. Moreover, while our study focused on dialysis, it did not assess policy for initiating comprehensive conservative care (CCC), which could improve survival, quality of life, and costs for patients who are not good candidates for dialysis, such as patients near end of life29. Future research should explore the potential benefit of policies to promote CCC for suitable patients in the Brunei context. Second, measuring opportunity costs comprehensively was challenging. We estimated the opportunity cost for patients’ time lost when visiting the hospital only for HD, while informal caregiver costs were included for all modalities. However, variations in time required based on disease severity and patient demographics could exist. Cost of complications were also not available for Brunei context and had to be used from other country despite poor transferability of costs across jurisdictions.

Third, for utility values, we used an averaged value for APD and CAPD due to the small sample size of PD patient. Larger sample sizes from policy implementation and evaluation would provide more precise estimates of opportunity cost and utility values and help validate our findings. These parameters align with the non-zero EVPPI results reported above and could benefit from further data collection in future research. Fourth, we assumed 70% compliance of KF patients with the APD- or CAPD-first policy based on Thailand data which achieved similar compliance during its PD-First policy implementation. Fifth, regarding expert opinion, there are very few nephrologists in Brunei, and the study included a relatively high proportion (40%) of local experts (two out of five nephrologists in 2024), and the current guidelines for structured elicitation of expert opinion are still impractical to implement within the tight timelines of a policy process. Lastly, due to the lack of local methodological guidelines for health economic evaluations, this study relied on international guidelines. For consistency with other policy decisions in Brunei, we recommend the development of country-specific guidelines for economic evaluation, following global good practice30.

Our results suggest that the Brunei government should adopt a PD-first policy for newly diagnosed kidney failure patients. Nevertheless, there remains uncertainty regarding whether the new PD-first policy would lead to improved health outcomes in Brunei especially for APD, as suggested by the value of information analysis. While the policy offers potential cost savings and logistical benefits, its impact on health outcomes, particularly survival rates, is not yet clear. Globally, there is no evidence of different survival between HD and PD, although the evidence base is weak31. We therefore recommend that the government continue to monitor differences in survival between HD and PD patients and to undertake measures to improve quality of services where necessary.

The success of a PD-first policy will not only depend on its cost-effectiveness but also on how well it addresses the needs of the dialysis patient population in Brunei. To support this transition, we recommend that the government implement educational interventions to enhance patients, family, and providers’ awareness of dialysis options and promote informed decision-making. Evidence shows that service improvements, such as assisted PD programs and patient education, may further increase PD acceptance and retention32. Financial incentives, such as subsidies for home setups and electricity costs, could also encourage acceptance of the policy, to increase the proportion of dialysis patients on PD and, ultimately, to improve sustainability of the KRT program in a country challenged by human resource constraints.

Data availability

The patient data that support the findings of this study is available on request from the corresponding authors. The Brunei Dialysis and transplant registry report is available on the Brunei Ministry of Health website11. The source data for Fig. 2 is in Supplementary Data, Sheet ‘PSA_scatterplot’. Modelled data and analyses are also available on request; interested individuals may contact the corresponding authors via email at nandar.m@hitap.net or chiaoyuen.lim@moh.gov.bn. A reasonable request refers to applications where data access is necessary for scientific, policy, or health-services research, is supported by a clear study protocol, and complies with local ethical and data-protection requirements. Apart from the BDTR report, all other data and analyses are provided in Excel format.

References

Mortality, G. B. D. Causes of Death, C. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388, 1459–1544 (2016).

Kidney disease a global health priority. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20, 421–423 (2024).

Francis, A. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20, 473–485 (2024).

Teerawattananon, Y., Dabak, S. V., Khoe, L. C., Bayani, D. B. S. & Isaranuwatchai, W. To include or not include: renal dialysis policy in the era of universal health coverage. BMJ 368, m82 (2020).

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Claxton, K., Stoddart, G. L. & Torrance, G. W. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Gupta, D. et al. Peritoneal dialysis-first initiative in India: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin. Kidney J. 15, 128–135 (2022).

Afiatin et al. Economic evaluation of policy options for dialysis in end-stage renal disease patients under the universal health coverage in Indonesia. PLoS One 12, e0177436 (2017).

Bayani, D. B. S. et al. Filtering for the best policy: An economic evaluation of policy options for kidney replacement coverage in the Philippines. Nephrol. (Carlton) 26, 170–177 (2021).

Yot Teerawattananon, M. M. Viroj tangcharoensathien. economic evaluation of palliative management versus peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease: evidence for coverage decisions in Thailand. Value Health 10, 61 (2007).

United States Renal Data System: USRDS annual data report.. Chapter 11: International Comparisons, :https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2024/end-stage-renal-disease/11-international-comparisons 2024.

Brunei Dialysis and Transplant Registry 13th Edition. https://moh.gov.bn/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/13th-ED-2023.pdf (2023).

Lim, C. Y. & Tan, J. Global dialysis perspective: Brunei Darussalam. Kidney360 2, 1027–1030 (2021).

Tan, J., Liew, Y. P., & Liew, A. Vol. 13 (eds ASIA-PACIFIC CHAPTER NEWSLETTER & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR PERITONEAL DIALYSIS (ISPD)) (2015).

Botwright, S. et al. Guidelines for the use of economic evaluation to inform policies around access to treatment for kidney failure. Nat Rev Nephrol, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-025-01000-w (2025).

Husereau, D. et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) Statement: Updated Reporting Guidance for Health Economic Evaluations. Value Health 25, 3–9 (2022).

Thailand Renal Replacement Therapy: Year 2016-2019. The Nephrology Society of Thailand (2021).

Johan, N. H. et al. End-stage kidney disease in Brunei Darussalam (2011-2020). Med J. Malays. 78, 54–60 (2023).

Turner, H. C., Lauer, J. A., Tran, B. X., Teerawattananon, Y. & Jit, M. Adjusting for Inflation and Currency Changes Within Health Economic Studies. Value Health 22, 1026–1032 (2019).

Yang, F., Lau, T. & Luo, N. Cost-effectiveness of haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease in Singapore. Nephrol. (Carlton) 21, 669–677 (2016).

Tang, C. H. et al. Out-of-pocket costs and productivity losses in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis from a patient interview survey in Taiwan. BMJ Open 9, e023062 (2019).

Labour Force Survey Department of Statistics, Department of Economic Planning and Statistics, Ministry of Finance and Econom, Brunei Darussalam Final Report (2023).

Koh, D., Abdullah, A. M., Wang, P., Lin, N. & Luo, N. Validation of Brunei’s Malay EQ-5D Questionnaire in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS One 11, e0165555 (2016).

Shafie, A. A. et al. EQ-5D-5L Valuation for the Malaysian Population. Pharmacoeconomics 37, 715–725 (2019).

Bilcke, J. & Beutels, P. Generating, Presenting, and Interpreting Cost-Effectiveness Results in the Context of Uncertainty: A Tutorial for Deeper Knowledge and Better Practice. Med Decis. Mak. 42, 421–435 (2022).

Fenwick, E., Marshall, D. A., Levy, A. R. & Nichol, G. Using and interpreting cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of management strategies for atrial fibrillation. BMC Health Serv. Res 6, 52 (2006).

Strong M., O. J., Brennan A. Estimating multi-parameter partial Expected Value of Perfect Information from a probabilistic sensitivity analysis sample: a non-parametric regression approach. Medical Decision Making. 34, (2014).

Lee, J. T. et al. Methods for health workforce projection model: systematic review and recommended good practice reporting guideline. Hum. Resour. Health 22, 25 (2024).

Devi, S. Brain drain laws spark debate over health worker retention. Lancet 401, 1838 (2023).

Verberne, W. R. et al. Health-related quality of life and symptoms of conservative care versus dialysis in patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 36, 1418–1433 (2021).

Botwright, S. Good Practices for Health Technology Assessment Guideline Development: A Report of the Health Technology Assessment International, HTAsiaLink, and ISPOR Special Task Force. Value Health 28, 1–15 (2025).

Ethier, I. et al. Peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis for people commencing dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD013800 (2024).

Yongphiphatwong N. The Way Home: A Scoping Review of Public Health Strategies to Increase the Utilization of Home Dialysis in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.29.24319745 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program Foundation (HITAP) is a research unit in Thailand and supports evidence-informed priority-setting and decision making for health. HITAP is funded by national and international public funding agencies. HITAP is supported by the Access and Delivery Partnership (ADP), which is hosted by the United Nations Development Programme and funded by the Government of Japan; the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) Fundamental Fund and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation [B41G670025], among others. We sincerely acknowledge all stakeholder groups for their contributions to this study. We especially thank to the Minister of Health in Brunei Darussalam- Dato Seri Setia Dr. Mohd Isham Jaafar, Dr. Valerie Luyckx- Scientific Officer and Senior Nephrologist from the University of Zurich, and our colleagues from the Ministry of Health in Brunei for their valuable insights and active participation in the stakeholder meeting for results presentation. We also extend our gratitude to Ms. Saudamini Dabak from HITAP for her exceptional efforts in coordinating and initiating this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CY, ANM, SR, YT, SB and LAR conceptualized the study. SR developed the study protocol. Data curation was performed by CY, ANM, and YT, while LAR and EO coordinated primary data collection. Formal analysis was conducted by ANM, YT, and WS, with model technical verification performed by SR. ANM drafted the manuscript, and all coauthors contributed to the review and editing of the final version. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Ricardo Silvarino Di Rago, Samuel Ajayi and Giovanni Tramonti for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Myint, A.N., Lim, C.Y., Rahim, S. et al. A cost- effectiveness and resource requirement comparison to optimize renal dialysis policies in Brunei Darussalam. Commun Med 5, 539 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01307-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01307-6