Abstract

Background

Applying large language models to medicine faces critical trust challenges in diagnostic reasoning. Existing approaches often fail to generalize across different models and datasets, particularly those covering a wide range of diseases and diverse patient records. This study aims to develop a universal model-based clinical framework that improves diagnostic performance while providing explainable reasoning.

Methods

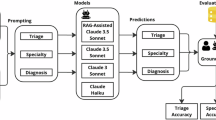

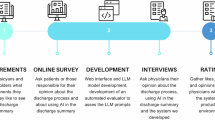

We introduce a structured clinical approach that replicates real-world diagnostic workflows. Patient narratives are first transformed into labeled clinical components. A validation mechanism then checks model-generated diagnoses using a disease knowledge algorithm. Additionally, a stepwise decision-making model simulates consultations progressing from junior to senior clinicians to refine diagnostic reasoning. The framework is evaluated across multiple large language models and clinical reasoning datasets using standard diagnostic accuracy metrics.

Results

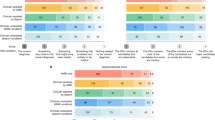

Here we show that our approach outperforms existing prompting methods across six large language models and two clinical datasets. One model achieves the highest diagnostic F1 scores (0.93 on NEJM, 0.95 on MedCaseReasoning) with minimal misclassification (1 false positive and 3 false negatives). It also attains the best text-based reasoning scores on NEJM, demonstrating effective, explainable clinical outputs. When validated on real-time electronic health record data, the method shows high diagnostic accuracy (0.91) and human-like rationales (4.5 out of 5), confirming its applicability in real-world clinical settings.

Conclusions

These findings confirm the robustness and generalizability of our framework, highlighting its potential for reliable, scalable, and explainable clinical decision support across diverse models and datasets.

Plain Language Summary

Medical decisions often rely on understanding complex patient information, and computational tools such as large language models can help analyze this data. However, these models sometimes make errors and their reasoning is not always clear. In this study, we developed a system that mimics how doctors work, breaking down patient notes into understandable pieces and checking model-generated diagnoses for accuracy. We tested this approach across multiple models and datasets. Here we show that it improves diagnostic accuracy, produces understandable explanations, and works well on real patient records. This method could make computer-assisted diagnosis more reliable, helping doctors make better decisions and potentially improving patient care in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

This study utilized two publicly available benchmark datasets and one small internal hospital dataset. 1. Publicly available datasets: The first dataset, https://huggingface.co/datasets/mamachang/medical-reasoningNEJM-MedQA-Diagnostic-Reasoning-Dataset (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01010-1) [25], and the second dataset, https://huggingface.co/datasets/zou-lab/MedCaseReasoningMedCaseReasoning (https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.11733)26, are both freely accessible through the Hugging Face platform. 2. Real hospital dataset: In addition, a small anonymized dataset was retrospectively obtained from The First Affiliated Hospital, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, consisting of 50 previously diagnosed and discharged patient cases. These anonymized clinical data cannot be publicly shared. This restriction ensures full protection of patient privacy while allowing ethical evaluation of the model’s performance in real EHR-derived clinical scenarios. All source data underlying the figures in the main manuscript are provided as Supplementary Data files. The source data for Figure 4 are available in Supplementary Data 1; the source data for Fig. 5 are available in Supplementary Data 2; the source data for Fig. 6 are available in Supplementary Data 3; the source data for Fig. 7 are available in Supplementary Data 4; the source data for Figure 8 are available in Supplementary Data 5; the source data for Figure 9 are available in Supplementary Data 6; the source data for Figure 10 are available in Supplementary Data 7; and the source data for Figure 11 are available in Supplementary Data 8.

Code availability

Most of the foundational code used in this study is based on publicly available resources, and no algorithmic code has been developed specifically for this work. All key components and methodologies are thoroughly described in the manuscript to support full reproducibility. The script used for neural network training is available at https://github.com/ayoubncbae/LLM_Clinical_Reasoning/blob/main/NeuralNetwork_for_classification_each_line.ipynbgithub.com/ayoubncbae/LLM_Clinical_Reasoning/ (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555909)27. The UMLS-based diagnosis matching script is provided at github.com/ayoubncbae/LLM_Clinical_Reasoning/28, and the code for clinical agent simulation-including junior, senior, and head doctor roles-is available at https://github.com/ayoubncbae/LLM_Clinical_Reasoning/blob/main/Agennt_Simulation_Code.pygithub.com/ayoubncbae/LLM_Clinical_Reasoning/(https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555909)29. Detailed prompts and design decisions are documented within the manuscript to facilitate reproducibility.

References

Liu, J., Wang, Y., Du, J., Zhou, J. & Liu, Z. Medcot: medical chain of thought via hierarchical expert. In Proc. 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 17371–17389 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Miami, Florida, USA, 2024).

Maharjan, J. et al. Openmedlm: prompt engineering can out-perform fine-tuning in medical question-answering with open-source large language models. Sci. Rep. 14, 14156 (2024).

Li, S. S. et al. Mediq: Question-asking llms for adaptive and reliable clinical reasoning. CoRR https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.00922 (2024).

Xu, K., Cheng, Y., Hou, W., Tan, Q. & Li, W. Reasoning like a doctor: improving medical dialogue systems via diagnostic reasoning process alignment. In Ku, L.-W., Martins, A. & Srikumar, V. (eds.) Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL, 6796–6814 https://aclanthology.org/2024.findings-acl.406. (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024).

Chang, Y. et al. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 15, 1–45 (2024).

Nachane, S. S. et al. Few shot chain-of-thought driven reasoning to prompt llms for open ended medical question answering. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.04890 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. MDAgents: An adaptive collaboration of LLMs for medical decision-making. In The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems https://openreview.net/forum?id=EKdk4vxKO4 (2024).

Anderson, N. E., Slark, J. & Gott, M. Unlocking intuition and expertise: using interpretative phenomenological analysis to explore clinical decision making. J. Res. Nurs. 24, 88–101 (2019).

Gat, Y. O. et al. Faithful explanations of black-box NLP models using LLM-generated counterfactuals. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/forum?id=UMfcdRIotC (2024).

Hayward, J. et al. Script-theory virtual case: a novel tool for education and research. Med. Teach. 38, 1130–1138 (2016).

Doğan, R. I., Leaman, R. & Lu, Z. Ncbi disease corpus: a resource for disease name recognition and concept normalization. J. Biomed. Inform. 47, 1–10 (2014).

Lindberg, C. The unified medical language system (umls) of the national library of medicine. J. Am. Med. Rec. Assoc. 61, 40–42 (1990).

Nilsson, M. S. & Pilhammar, E. Professional approaches in clinical judgements among senior and junior doctors: implications for medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 9, 1–9 (2009).

Hailey, A. The final diagnosis (Open Road Media, 2015).

Stewart, J. Asking for senior intervention: conceptual insights into the judgement of risk by junior doctors. Ph.D. thesis, Newcastle University (2006).

Savage, T., Nayak, A., Gallo, R., Rangan, E. & Chen, J. H. Diagnostic reasoning prompts reveal the potential for large language model interpretability in medicine. npj Digit. Med. 7, 20 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-024-01010-1 (2024).

Case records of the massachusetts general hospital articles. 2020–2023. https://www.nejm.org/medical-articles/case-records-of-the-massachusetts-general-hospital. Accessed May 2023.

Wu, K. et al. Medcasereasoning: evaluating and learning diagnostic reasoning from clinical case reports. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.11733 (2025).

Wu, Q., Gao, Z., Gou, L. & Dou, Q. Ddxtutor: Clinical reasoning tutoring system with differential diagnosis-based structured reasoning. In Proc. 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 30934–30957 (2025).

Wu, J., Wu, X. & Yang, J. Guiding clinical reasoning with large language models via knowledge seeds. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.06609 (2024).

Xu, K., Cheng, Y., Hou, W., Tan, Q. & Li, W. Reasoning like a doctor: Improving medical dialogue systems via diagnostic reasoning process alignment. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.13934 (2024).

Kwon, T. et al. Large language models are clinical reasoners: Reasoning-aware diagnosis framework with prompt-generated rationales. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 38, 18417–18425 (2024).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Guevara, M. et al. Large language models to identify social determinants of health in electronic health records. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 6 (2024).

Mamachang, L. et al. Nejm-medqa-diagnostic-reasoning-dataset. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01010-1 (2024).

Zou, J. et al. Medcasereasoning. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.11733 (2023).

Ayoub, B. et al. Neural network for classification each line. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555909 (2023).

Ayoub, B. et al. Umls matching code. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555909 (2023).

Ayoub, B. et al. Clinical agent simulation code. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17555909 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Grant number: W2542038, the Shanghai Jiao Tong University 2030 Initiative, and the Major Program of the Chinese National Foundation of Social Sciences under Grant No. 23&ZD213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. contributed Conceptualization, Method, Experiment analysis, Writing—review & editing. H.Z. contributed supervision, investigation, Writing—review & editing. L.L. contributed data curation, methodology, Writing—review & editing. D.Y. contributed formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. S.H. contributed Writing—review & editing. J.A.W. contributed invagination Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayoub, M., Zhao, H., Li, L. et al. Structured clinical approach to enable large language models to be used for improved clinical diagnosis and explainable reasoning. Commun Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01348-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01348-x