Abstract

Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects about 1% of births and is linked to differences in thinking and learning. Understanding how birth, genetic, clinical, and environmental factors together explain cognitive variability can inform monitoring and care. This study builds a multivariate model predicting cognition across multiple domains in adolescents and young adults with CHD.

Methods

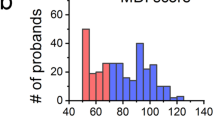

We studied 89 adolescents and young adults (AYAs; mean age 16 years) with CHD who completed structural and diffusion MRI and fifteen neurocognitive tests across seven domains. Using an enhanced forward-inclusion and backward-elimination strategy with cross-validation, we built multivariate models incorporating biological, socioeconomic, clinical, genetic, and brain imaging features. Performance was evaluated using Pearson correlation (\(r\)) between observed and inferred scores, mean absolute error (MAE), and inverse inferability score (IIS).

Results

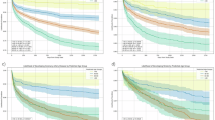

Here we show that models infer scores with moderate accuracy (\(r\) = 0.245–0.648; MAE = 1.6–12.0 points; mean MAE = 6.3). Highest correlations include Digit Span (\(r\) = 0.65; p < 0.001), Verbal Comprehension Index (\(r\) = 0.594; p < 0.001), and Matrix Reasoning (\(r\) = 0.574; p < 0.001). Domain ranking by IIS shows the best (lowest) scores for general intelligence (0.0886), followed by working memory (0.7100), and a higher (worse) score for perceptual reasoning (1.9199).

Conclusions

A multivariate approach combining brain imaging with genetic, clinical, and environmental factors provides clinically meaningful inference of individual cognitive performance in AYAs with CHD. These findings suggest complementary roles of brain, genetic, and contextual factors in shaping cognitive variability and motivate validation in larger cohorts.

Plain Language Summary

Children born with congenital heart disease can have differences in thinking and learning. We aimed to learn which factors, brain structure, genetics, medical history, and family environment, explain these differences in teens and young adults. We combined brain scans with health, family, and genetic information and used computer models to estimate scores on standard tests. The models reasonably estimated individual scores; some abilities, such as general thinking skills, working memory, and processing speed, were estimated more accurately than others. These findings suggest that brain scans, together with medical and family information, can provide a clearer picture of thinking skills. With further testing in larger, diverse groups, this approach could help guide follow‑up care tailored to each person.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The source data underlying Fig. 2 are provided in Supplementary Data 1–3. Specifically, Fig. 2a data are available in Supplementary Data 1, Fig. 2b in Supplementary Data 2, and Fig. 2c-q in Supplementary Data 3. The datasets used for model training and validation contain controlled-access human subject data, including brain MRI, genomic (whole-exome/genome–derived variants), demographic, and socioeconomic information from participants enrolled in the PCGC CHD Brain and Genes study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03070197). These data are not publicly available due to ethical, legal, and privacy considerations associated with identifiable and potentially re-identifiable participant information, as governed by the informed consent, institutional review board (IRB) approvals, and NIH data-sharing policies. Conditions of access. Access to the controlled datasets may be granted to qualified investigators for legitimate academic research purposes, subject to (i) approval by the data-holding institution(s), (ii) verification of IRB or equivalent ethics approval at the requesting institution (or determination of exemption, as applicable), and (iii) execution of an appropriate Data Use Agreement (DUA). Timeframe for response. Data access requests will be acknowledged within 2 weeks of receipt, and a decision will typically be communicated within 4–8 weeks, depending on the completion of institutional review and DUA processing. Restrictions on data use. Approved data may be used only for the purposes described in the approved request and in compliance with the DUA. Restrictions include but are not limited to: (a) no attempts at participant re-identification; (b) no redistribution or sharing of the data with third parties; (c) secure data storage and access limited to authorized personnel; and (d) destruction or return of the data upon completion of the approved research, as specified in the DUA. Request process. Access requests should be directed to Prof. Yangming Ou, PhD (yangming.ou@childrens.harvard.edu) or Prof. Sarah U. Morton, MD, PhD (sarah.morton@childrens.harvard.edu), who are responsible for coordinating institutional review and responding to data access requests.

Code availability

The source codes of our enhanced forward inclusion and backward elimination (FIBE)62 approach used in this manuscript are available at https://github.com/i3-research/fibe and at Zenodo62.

References

Lopez, K. N., Morris, S. A., Sexson Tejtel, S. K., Espaillat, A. & Salemi, J. L. US Mortality Attributable to Congenital Heart Disease across the Lifespan from 1999 through 2017 Exposes Persistent Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Circulation 142, 1132–1147 (2020).

Udine, M. L., Evans, F., Burns, K. M., Pearson, G. D. & Kaltman, J. R. Geographical Variation in Infant Mortality Due to Congenital Heart Disease in the USA: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 5, 483–490 (2021).

Boneva, R. S. et al. Mortality Associated with Congenital Heart Defects in the United States: Trends and Racial Disparities, 1979–1997. Circulation 103, 2376–2381 (2001).

Gilboa, S. M., Salemi, J. L., Nembhard, W. N., Fixler, D. E. & Correa, A. Mortality Resulting from Congenital Heart Disease among Children and Adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Circulation 122, 2254–2263 (2010).

Russell, M. W., Chung, W. K., Kaltman, J. R. & Miller, T. A. Advances in the Understanding of the Genetic Determinants of Congenital Heart Disease and Their Impact on Clinical Outcomes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e006906 (2018).

Sun, R., Liu, M., Lu, L., Zheng, Y. & Zhang, P. Congenital Heart Disease: Causes, Diagnosis, Symptoms, and Treatments. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 72, 857–860 (2015).

Kasmi, L. et al. Neurocognitive and Psychological Outcomes in Adults with Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries Corrected by the Arterial Switch Operation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 105, 830–836 (2018).

Bellinger, D. C. et al. Neuropsychological Status and Structural Brain Imaging in Adolescents with Single Ventricle Who Underwent the Fontan Procedure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e002302 (2015).

Schaefer, C. et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcome, Psychological Adjustment, and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Congenital Heart Disease. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 55, 1143–1149 (2013).

Miller, S. P. et al. Abnormal Brain Development in Newborns with Congenital Heart Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1928–1938 (2007).

Donofrio, M. T. & Limperopoulos, C. Impact of Congenital Heart Disease on Fetal Brain Development and Injury. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 23, 502–511 (2011).

McQuillen, P. S., Goff, D. A. & Licht, D. J. Effects of Congenital Heart Disease on Brain Development. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 29, 79–85 (2010).

Marelli, A., Miller, S. P., Marino, B. S., Jefferson, A. L. & Newburger, J. W. Brain in Congenital Heart Disease across the Lifespan: The Cumulative Burden of Injury. Circulation 133, 1951–1962 (2016).

von Rhein, M. et al. Brain Volumes Predict Neurodevelopment in Adolescents after Surgery for Congenital Heart Disease. Brain 137, 268–276 (2014).

Areias, M. E. et al. Neurocognitive Profiles in Adolescents and Young Adults with Congenital Heart Disease. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 37, 923–931 (2018).

Cassidy, A. R., Newburger, J. W. & Bellinger, D. C. Learning and Memory in Adolescents with Critical Biventricular Congenital Heart Disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 23, 627–639 (2017).

DeMaso, D. R. et al. Psychiatric Disorders in Adolescents with Single Ventricle Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatrics 2017, 139 .

Lankalapalli, R. et al. Accelerated Brain Aging in Congenital Heart Disease and Relation to Neurodevelopmental Outcome. In 60th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology; ASNR, 2022.

Bagge, C. N. et al. Risk of Dementia in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: Population-Based Cohort Study. Circulation 137, 1912–1920 (2018).

Downing, K. F., Oster, M. E., Olivari, B. S. & Farr, S. L. Early-Onset Dementia among Privately-Insured Adults with and without Congenital Heart Defects in the United States, 2015–2017. Int. J. Cardiol. 358, 34–38 (2022).

Miller, R. Neuroeducation: Integrating Brain-Based Psychoeducation into Clinical Practice. J. Ment. Health Couns. 38, 103–115 (2016).

Özdemir, M. B. & Bengisoy, A. Effects of an Online Solution-Focused Psychoeducation Programme on Children’s Emotional Resilience and Problem-Solving Skills. Front. Psychol. 13, 870464 (2022).

McCusker, C. G. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Interventions to Promote Adjustment in Children with Congenital Heart Disease Entering School and Their Families. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 37, 1089–1103 (2012).

Klingberg, T. et al. Computerized Training of Working Memory in Children with ADHD-a Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 44, 177–186 (2005).

Diamond, A. & Lee, K. Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science 333, 959–964 (2011).

Calderon, J. & Bellinger, D. C. Executive Function Deficits in Congenital Heart Disease: Why Is Intervention Important? Cardiol. Young 25, 1238–1246 (2015).

Liamlahi, R. & Latal, B. Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Children with Congenital Heart Disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 162, 329–345 (2019).

Urschel, S. et al. Neurocognitive Outcomes after Heart Transplantation in Early Childhood. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 37, 740–748 (2018).

Sterling, L. H. et al. Neurocognitive Disorders amongst Patients with Congenital Heart Disease Undergoing Procedures in Childhood. Int. J. Cardiol. 336, 47–53 (2021).

Verrall, C. E. et al. Big Issues’ in Neurodevelopment for Children and Adults with Congenital Heart Disease. Open Heart 6, e000998 (2019).

Forbess, J. M. et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcome after Congenital Heart Surgery: Results from an Institutional Registry. Circulation 106, I-95-I–102 (2002).

Goldberg, C. S. et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Patients after the Fontan Operation: A Comparison between Children with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome and Other Functional Single Ventricle Lesions. J. Pediatr. 137, 646–652 (2000).

Morton, S. U. et al. Association of Potentially Damaging de Novo Gene Variants with Neurologic Outcomes in Congenital Heart Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2253191–e2253191 (2023).

Williams, I. A. et al. Fetal Cerebrovascular Resistance and Neonatal EEG Predict 18-month Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Infants with Congenital Heart Disease. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 40, 304–309 (2012).

Skotting, M. B. et al. Infants with Congenital Heart Defects Have Reduced Brain Volumes. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–8 (2021).

Kessler, N. et al. Structural Brain Abnormalities in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: Prevalence and Association with Estimated Intelligence Quotient. Int. J. Cardiol. 306, 61–66 (2020).

Bolduc, M.-E., Lambert, H., Ganeshamoorthy, S. & Brossard-Racine, M. Structural Brain Abnormalities in Adolescents and Young Adults with Congenital Heart Defect: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 60, 1209–1224 (2018).

Asschenfeldt, B. et al. Neuropsychological Status and Structural Brain Imaging in Adults with Simple Congenital Heart Defects Closed in Childhood. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e015843 (2020).

Oster, M. E., Watkins, S., Hill, K. D., Knight, J. H. & Meyer, R. E. Academic Outcomes in Children with Congenital Heart Defects: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 10, e003074 (2017).

Savory, K., Manivannan, S., Zaben, M., Uzun, O. & Syed, Y. A. Impact of Copy Number Variation on Human Neurocognitive Deficits and Congenital Heart Defects: A Systematic Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 108, 83–93 (2020).

Derridj, N. et al. Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Children with Congenital Heart Defects. J. Pediatr. 237, 109–114. e5 (2021).

Gaynor, J. W. et al. International Cardiac Collaborative on Neurodevelopment (ICCON) Investigators. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes after Cardiac Surgery in Infancy. Pediatrics 135, 816–825 (2015).

Gaynor, J. W. et al. Impact of Operative and Postoperative Factors on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes after Cardiac Operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 102, 843–849 (2016).

Hussain, M. A., Li, G., Grant, E. & Ou, Y. Influence of Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Brain Structural Factors on Adolescent Neurocognition: A Correlation Analysis in the ABCD Initiative. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.02. 24.529930.

Von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

He, S., Grant, P. E. & Ou, Y. Global-Local Transformer for Brain Age Estimation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 213–224 (2021).

He, S., Feng, Y., Grant, P. E. & Ou, Y. Deep Relation Learning for Regression and Its Application to Brain Age Estimation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 2304–2317 (2022).

He, S. et al. Multi-Channel Attention-Fusion Neural Network for Brain Age Estimation: Accuracy, Generality, and Interpretation with 16,705 Healthy MRIs across Lifespan. Med. Image Anal. 72, 102091 (2021).

Tisdall, M. D. et al. Volumetric Navigators for Prospective Motion Correction and Selective Reacquisition in Neuroanatomical MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 68, 389–399 (2012).

White, N. et al. PROMO: Real-time Prospective Motion Correction in MRI Using Image-based Tracking. Magn. Reson. Med. Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 63, 91–105 (2010).

Zhuang, J. et al. Correction of Eddy-current Distortions in Diffusion Tensor Images Using the Known Directions and Strengths of Diffusion Gradients. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 24, 1188–1193 (2006).

Andersson, J. L. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. An Integrated Approach to Correction for Off-Resonance Effects and Subject Movement in Diffusion MR Imaging. Neuroimage 125, 1063–1078 (2016).

Jovicich, J. et al. Reliability in Multi-Site Structural MRI Studies: Effects of Gradient Non-Linearity Correction on Phantom and Human Data. Neuroimage 30, 436–443 (2006).

Wells III, W. M., Viola, P., Atsumi, H., Nakajima, S. & Kikinis, R. Multi-Modal Volume Registration by Maximization of Mutual Information. Med. Image Anal. 1, 35–51 (1996).

Fortin, J.-P. et al. others. Harmonization of Cortical Thickness Measurements across Scanners and Sites. Neuroimage 167, 104–120 (2018).

Vandewouw, M. M. et al. others. Identifying Novel Data-Driven Subgroups in Congenital Heart Disease Using Multi-Modal Measures of Brain Structure. NeuroImage 297, 120721 (2024).

Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781 (2012).

Niileksela, C. R. & Reynolds, M. R. Enduring the Tests of Age and Time: Wechsler Constructs across Versions and Revisions. Intelligence 77, 101403 (2019).

Moser, R. S., Schatz, P., Grosner, E. & Kollias, K. One Year Test–Retest Reliability of Neurocognitive Baseline Scores in 10-to 12-Year Olds. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 6, 166–171 (2017).

Pauls, F. & Daseking, M. Revisiting the Factor Structure of the German WISC-V for Clinical Interpretability: An Exploratory and Confirmatory Approach on the 10 Primary Subtests. Front. Psychol. 12, 710929 (2021).

Staios, M. athew et al. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition, Greek Adaptation (WAIS-IV GR): Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Specific Reference Group Normative Data for Greek Australian Older Adults. Aust. Psychol. 58, 248–263 (2023).

Hussain, M. A. FeatureMint: Efficient Feature Selection Using Forward Inclusion & Backward Elimination, 2025. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17773415.

Da, X. et al. Integration and Relative Value of Biomarkers for Prediction of MCI to AD Progression: Spatial Patterns of Brain Atrophy, Cognitive Scores, APOE Genotype and CSF Biomarkers. NeuroImage Clin 4, 164–173 (2014).

Ou, Y., Sotiras, A., Paragios, N. & Davatzikos, C. DRAMMS: Deformable Registration via Attribute Matching and Mutual-Saliency Weighting. Med. Image Anal. 15, 622–639 (2011).

Ou, Y. et al. Sampling the Spatial Patterns of Cancer: Optimized Biopsy Procedures for Estimating Prostate Cancer Volume and Gleason Score. Med. Image Anal. 13, 609–620 (2009).

Ji, W. et al. De Novo Damaging Variants Associated with Congenital Heart Diseases Contribute to the Connectome. Sci. Rep. 10, 7046 (2020).

Patt, E., Singhania, A., Roberts, A. E. & Morton, S. U. The Genetics of Neurodevelopment in Congenital Heart Disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 39, 97–114 (2023).

Marino, B. S. et al. others. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children with Congenital Heart Disease: Evaluation and Management: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 126, 1143–1172 (2012).

Phillips, K. et al. Neuroimaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes among Individuals with Complex Congenital Heart Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82, 2225–2245 (2023).

Spillmann, R. et al. Congenital Heart Disease in School-Aged Children: Cognition, Education, and Participation in Leisure Activities. Pediatr. Res. 94, 1523–1529 (2023).

Ortinau, C. M. et al. Optimizing Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Neonates with Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatrics. 150, e2022056415L (2022).

Violant-Holz, V., Muñoz-Violant, S. & Rodrigo-Pedrosa, O. Challenges of Inclusive Schooling for Children and Adolescents with Congenital Heart Disease: A Phenomenological Study. Psychol. Sch. 60, 4946–4966 (2023).

Dardas, L. A. et al. Beyond the Heart: Cognitive and Verbal Outcomes in Arab Children with Congenital Heart Diseases. Birth Defects Res 116, e2374 (2024).

Jonas, R. A. Challenges for Adult Survivors of Simple Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association 9, e017210 (2020).

Sood, E. et al. others. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes for Individuals with Congenital Heart Disease: Updates in Neuroprotection, Risk-Stratification, Evaluation, and Management: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 149, e997–e1022 (2024).

Marelli, A., Gauvreau, K., Landzberg, M. & Jenkins, K. Sex Differences in Mortality in Children Undergoing Congenital Heart Disease Surgery: A United States Population–Based Study. Circulation 122, S234–S240 (2010).

Chang, R.-K. R., Chen, A. Y. & Klitzner, T. S. Female Sex as a Risk Factor for In-Hospital Mortality among Children Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Circulation 106, 1514–1522 (2002).

Crain, A. K. et al. Meta-Analysis on Sex Differences in Mortality and Neurodevelopment in Congenital Heart Defects. Sci. Rep. 15, 8152 (2025).

Rollins, C. K. et al. White Matter Volume Predicts Language Development in Congenital Heart Disease. J. Pediatr. 181, 42–48 (2017).

Marelli, A. Trajectories of Care in Congenital Heart Disease–the Long Arm of Disease in the Womb. J. Intern. Med. 288, 390–399 (2020).

Fiez, J. A. & Petersen, S. E. Neuroimaging Studies of Word Reading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 914–921 (1998).

Wehbe, L. et al. Simultaneously Uncovering the Patterns of Brain Regions Involved in Different Story Reading Subprocesses. PloS One 9, e112575 (2014).

Fengler, A., Meyer, L. & Friederici, A. D. Brain Structural Correlates of Complex Sentence Comprehension in Children. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 15, 48–57 (2015).

Philipose, L. E. et al. Neural Regions Essential for Reading and Spelling of Words and Pseudowords. Ann. Neurol. Off. J. Am. Neurol. Assoc. Child Neurol. Soc. 62, 481–492 (2007).

Brookman-Byrne, A., Mareschal, D., Tolmie, A. K. & Dumontheil, I. The Unique Contributions of Verbal Analogical Reasoning and Nonverbal Matrix Reasoning to Science and Maths Problem-Solving in Adolescence. Mind Brain Educ 13, 211–223 (2019).

Van den Broek, G. S., Takashima, A., Segers, E., Fernández, G. & Verhoeven, L. Neural Correlates of Testing Effects in Vocabulary Learning. NeuroImage 78, 94–102 (2013).

Colom, R., Jung, R. E. & Haier, R. J. Distributed Brain Sites for the G-Factor of Intelligence. Neuroimage 31, 1359–1365 (2006).

Turken, U. et al. Cognitive Processing Speed and the Structure of White Matter Pathways: Convergent Evidence from Normal Variation and Lesion Studies. Neuroimage 42, 1032–1044 (2008).

Silva da, P. H. R. et al. Brain Functional and Effective Connectivity Underlying the Information Processing Speed Assessed by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Neuroimage 184, 761–770 (2019).

Joung, H. et al. Functional Neural Correlates of the WAIS-IV Block Design Test in Older Adult with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroscience 463, 197–203 (2021).

Desco, M. et al. Mathematically Gifted Adolescents Use More Extensive and More Bilateral Areas of the Fronto-Parietal Network than Controls during Executive Functioning and Fluid Reasoning Tasks. Neuroimage 57, 281–292 (2011).

Yang, Z. et al. Intrinsic Brain Indices of Verbal Working Memory Capacity in Children and Adolescents. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 15, 67–82 (2015).

Jung, R. E. & Haier, R. J. The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) of Intelligence: Converging Neuroimaging Evidence. Behav. Brain Sci. 30, 135–154 (2007).

Aleksonis, H. A. & King, T. Z. Relationships among Structural Neuroimaging and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 33, 432–458 (2023).

Karczewski, K. J. et al. The Mutational Constraint Spectrum Quantified from Variation in 141,456 Humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the families and participants whose time and commitment made this research possible. We also thank the clinical coordinators, research staff, and collaborators who supported data collection and processing including Somer Bishop, Henry Buswell, Christopher Cannistraci, Johanna Calderon, Victor Chen, Lauren Christopher, Todd Constable, Nancy Cross, Cecelia DeSoto, Lazar Fleysher, John Foxe, Ed Freedman, Borjan Gagoski, Anne Snow Gallagher, Judith Geva, Emily Griffin, Dorota Gruber, Abha Gupta, Brandi Henson, Rick Kim, Alex Kolevzon, Linda Lambert, Kristen Lanzilotta, Brande Latney, Christina Layton, Derek Lundahl, Shannon Lundy, Stacy Lurie, Meghan MacNeal, Laura Ment, Julith S. Miller, Leona Oakes, Sharon O’Neill, Minhui Ouyang, Emily Richardson, Angela Romano-Adesman, Kelly Sadamitsu, Hedy Sarofin, Anjali Sadhwani, Dustin Scheinost, Zoey Shaw, Paige Siper, Deepak Srivastava, Sherin Stahl, Eileen Taillie, Allison Thomas, Alexandra Thompson, Nhu Tran, Marti Tristani, Henry Wang, Ting Wang, Wing Wang, Sarah Winter, Julie Wolf, Han Yin, Duan Xu, Amy Young, Yensy Zetino, and Brandon Zielinski for their contributions to the study. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health – 1066 [5U01HL131003-09 (subaward number: OS00000958)]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.U.M. and Y.O. jointly supervised the research. M.A.H. and Y.O. conceptualized and designed the study. M.A.H. developed the machine learning algorithm. M.A.H., S.U.M., and Y.O. conducted the data analysis and interpreted the results. D.C.B., W.K.C., D.X., Y.S., J.W.N., and P.E.G. offered senior mentorship and insightful comments that shaped the study design and interpretation. S.H. generated the brain age deviation data. H.R.A. assisted in organizing the neurocognitive functions into their respective broad cognitive domains. E.A., M.B., J.C., B.D.G., E.G., D.J.H., H.H., P.M.Q., T.A.M., A.N.B., G.A.P., N.T., M.E.T., and J.W.N. contributed to the collection and structured organization of data from participating centers. M.A.H., S.U.M., and Y.O. contributed to drafting the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks John Jairo Araujo, Jitse S. Amelink and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussain, M.A., He, S., Adams, H.R. et al. Machine learning to infer neurocognitive testing scores among adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease. Commun Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-026-01417-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-026-01417-9