Abstract

Here we present the ambiphilic reactivity of alkyl sulfonyl fluorides in the stereoselective synthesis of diverse cyclopropanes from olefins, under palladium(II) catalysis. The sulfonyl fluoride functionality serves as both an acidifying group and an internal oxidant within the ambiphile, enabling successive carbopalladation and oxidative addition steps in the catalytic cycle, respectively. The transformation grants access to cis-substituted cyclopropanes and exhibits broad compatibility with various alkyl sulfonyl fluorides, including those bearing –CN, –CO2R, isoxazolyl, pyrazolyl and aryl groups. With internal alkene substrates, 1,2,3-trisubstituted cyclopropanes that are otherwise challenging to synthesize are formed in good-to-moderate yields and predictable diastereoselectivity. Detailed mechanistic insights from reaction progress kinetic analysis and density functional theory calculations reveal that the SN2-type C–SO2F oxidative addition is the turnover-limiting and diastereoselectivity-determining step.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

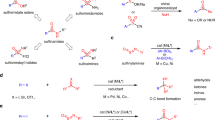

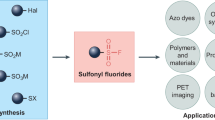

Organosulfonyl fluorides have emerged as central players in organic synthesis1,2,3, owing to the rise of sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEX) chemistry, which enables rapid and reliable diversification through nucleophilic displacement of fluoride with oxygen and nitrogen nucleophiles4,5,6. The utility of organosulfonyl fluorides in this context has motivated the development of a growing number of methods to synthesize structurally diverse sulfonyl fluorides in an efficient, selective and modular manner7,8,9,10,11 (Fig. 1a).

In contrast to widely studied aryl-12,13,14,15,16,17, alkenyl-18,19,20,21 and alkynyl sulfonyl fluorides11, alkyl sulfonyl fluorides have been less thoroughly investigated despite offering unique opportunities as synthetic building blocks owing to the acidifying effect of the sulfonyl group on the α-protons5. In recent work, Bull developed an elegant series of desulfonative couplings of azetidine and oxetane sulfonyl fluorides for C–heteroatom bond formation22,23. Prior work has demonstrated the utility of alkyl sulfonyl fluorides in C–C bond formation through reaction with classical electrophiles, such as alkyl halides and carbonyl compounds, in the presence of base16,17,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 (Fig. 1b). We surmised that alkyl sulfonyl fluorides could exhibit unique ambiphilic reactivity in transition metal catalysis, capitalizing on the ability of the sulfonyl fluoride group to serve the dual role as a pronucleophile activator and electrophilic reactive group (internal oxidant).

Our laboratory previously developed a palladium-catalysed anti-cyclopropanation of olefins with various carbon pronucleophiles and I2 as the bystanding oxidant, where the hypothesized mechanism involves initial α-iodination of the nucleophile, directed carbopalladation, PdII/PdIV oxidative addition of the newly formed C(sp3)–I bond and, finally, C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination from the palladacyclobutane intermediate31. The need for doubly activated carbon pronucleophiles in all cases but nitromethane limits the scope of substituted cyclopropanes that can be accessed with this method, leading us to search for alternative nucleophilic coupling partners in which a leaving group and an acidifying group could be merged into the same entity.

Here, we demonstrate alkyl sulfonyl fluorides acting as ambiphilic coupling partners in the stereoselective cyclopropanation of unactivated olefins through the PdII/PdIV redox couple. The catalytic cycle leverages a novel mode of reactivity, C(sp3)–SO2F bonds oxidatively adding to organopalladium(II) intermediates, to deliver stereochemical outcomes that are inaccessible using conventional leaving groups32,33,34,35 (Fig. 1b). While this paper was in revision, Mane and Baidya reported a directed cyclopropanation reaction involving ketone-derived sulfoxonium ylides to access related cis-1,2-disubstituted cyclopropane products36.

Results and discussion

Reaction development

In this context, alkenyl amide 1a, featuring the 8-aminoquinoline directing auxiliary required for reactivity31, and alkyl sulfonyl fluoride 2a were selected as model substrates. After extensive screening, we identified optimal reaction conditions using a combination of Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%) and Na2CO3 (1.0 equiv.) in dimethylacetamide (DMA) (0.33 M) under a nitrogen atmosphere to afford cyclopropane 3aa in 94% yield with 98:2 diastereomeric ratio (d.r.); the unusual cis-configuration of the major product was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction37,38,39,40,41,42 (Table 1). Key findings from our optimization campaign include the important role of Na2CO3 as the base, as other carbonate salts, such as K2CO3 and Cs2CO3, led to substantially lower yields (entries 2 and 3), as did bases with other counteranions (entries 4 and 5). Other commonly used PdII sources, such as PdCl2 and Pd(TFA)2 (where TFA is trifluoroacetate), gave slightly lower yields and comparable diastereoselectivity (entries 6 and 7). Increasing the concentration of the reaction mixture decreased the yield (entry 8). The use of a polar aprotic solvent was crucial, and dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were reasonably effective alternatives to DMA (entries 9–13). We were also pleased to find that the reaction gave 92% yield even when set up and run under air with anhydrous DMA (entry 14). In control experiments, we found that changing the leaving group to sulfonyl chloride (LG2), phenyl sulfonyl (LG3) or methyl sulfonyl (LG4) groups led to no reaction or trace product formation (entry 15), indicating that the sulfonyl fluoride is key for the observed reaction. A representative sulfonium bromide sulfur ylide precursor (LG5) gave moderate yields but poor d.r. Beyond sulfur-based leaving groups, halides were also tested but found to be ineffective. An additional control experiment revealed that 2a furnished a different product, a tri-substituted cyclopropane with the –SO2F group intact, when subjected to previously reported conditions for PdII-catalysed cyclopropanation31 (see ‘Pd(0) salt screening and control experiments’ section in Supplementary Information).

In seeking to rationalize the optimization data, we considered previous reports that found alkyl sulfonyl fluorides, such as phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), to be highly unstable in aqueous solutions43. We questioned whether yield differences could be partially attributed to the competitive decomposition of the nucleophile under different conditions (in different solvents and in the presence or absence of adventitious water). To this end, we examined the stability of alkyl sulfonyl fluoride 2a in DMA, DMF and DMSO (see Table 2 and ‘Stability tests’ section in Supplementary Information for details). Surprisingly, alkyl sulfonyl fluoride 2a was fully decomposed in anhydrous DMSO after 2 h but proved to be relatively stable in anhydrous DMF. Similarly, we found no decomposition of alkyl sulfonyl fluoride 2a in anhydrous DMA under an inert atmosphere. However, under air, moderate levels of decomposition in DMA could be detected, and complete decomposition was observed in wet DMA. Under aerobic conditions, oxidation and subsequent decomposition of DMA into N-methylacetamide and formaldehyde has been previously documented and could be a contributing factor to these observations44. These results indicate that the rate of decomposition of 2a is dependent on the solvent identity and amount of adventitious water in the solution.

Substrate scope

Having optimized the conditions, we began investigating the scope with respect to the alkyl sulfonyl fluoride, many of which are commercially available or readily accessible using routine procedures (see ‘General procedures for starting material preparation’ section in Supplementary Information) (Fig. 2). The reaction proceeded in moderate-to-excellent yields with various ester nucleophiles, including ethyl ester (3ab), tert-butyl ester (3ac), benzyl ester (3ad), allyl ester (3ae) and phenyl ester (3af), providing the corresponding cis-cyclopropanes as the major products with high diastereoselectivity and without appreciable base-mediated epimerization45. Amide or nitrile-based coupling partners (3ag–3ah) led to diminished yield but maintained excellent cis-diastereoselectivity (>20:1). We found that the reaction could tolerate weaker electron-withdrawing groups, including a 2-bromopropenyl group (3ai) and various heterocycles, including isoxazole (3aj) and 1-methyl-1H-pyrazole (3ak), which gave 32%, 43% and 20% yield, respectively. An α-aryl alkyl sulfonyl fluoride nucleophile participated in the reaction to form a fully substituted carbon centre within the cyclopropane, albeit with moderate yield and d.r. (3al). Aryl-substituted methylene sulfonyl fluorides were also investigated. Interestingly, the reaction did not proceed with unsubstituted, electron-neutral benzylsulfonyl fluoride, but proceeded with substituted benzylsulfonyl fluoride substrates bearing electron-withdrawing groups at the para-position (3am–3ap). Stronger electron-withdrawing groups led to improved yields and diastereoselectivity. A meta-nitro substrate was also tolerated (3aq).

Reactions performed on 0.1 mmol scale. Percentages represent isolated yields. The d.r. was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of crude or purified reaction mixture. The diastereomeric centre is highlighted with a blue circle. aReactions performed under 20 mol% catalyst loading. bReactions performed under 5 equiv. alkyl fluoride loading. cReactions performed under 24 h. dReactions performed under 36 h.

Next, the scope of alkenes was investigated. Internal alkenes afforded good-to-moderate yields (4aa–4ae). Notably, (Z)-alkenes reacted with excellent diastereoselectivity (>20:1), affording a single diastereomer. To our delight, under the standard condition, the thermodynamically and kinetically unfavourable all-cis cyclopropane could be synthesized from an (E)-configured internal alkene in one step in moderate yield (4ad) with 1.1:1 d.r. In addition, α-substituted β,γ-unsaturated amide substrates are well tolerated, giving the desired products in moderate-to-excellent yields (4af–4ai). Specifically, a diene substrate (4ag) could be chemoselectively cyclopropanated at the β,γ-alkene, while leaving the δ,ε-alkene unperturbed. When the tether length between the alkene and directing group was extended and a γ,δ-unsaturated amide was tested, the cyclopropane product was furnished in moderate yield with excellent diastereoselectivity (4ak).

The methodology could be easily scaled up and performed on 1.0-mmol scale under the standard reaction conditions, giving cis-cyclopropane 3aa in 86% yield (Fig. 3a). Performing the reaction on 100 mmol scale resulted in 81% yield with 9:1 d.r. Removal of the directing auxiliary was possible through a two-step sequence46. Initial introduction of an N-Boc activating group proceeded in 83% yield (5aa). Then, hydrolysis with LiOOH/water gave carboxylic acid 6aa in 86% yield on multigram-scale, which has been commercialized by Enamine (Fig. 3b). Alternatively, a representative amine could be used in the second step in a net transamidation (58% yield, 6ab). If desired by the practitioner, the loading of nucleophile 2a can be lowered to 1.5 equiv. while maintaining comparable yield and diastereoselectivity with a dual base system (0.75 equiv. NaF and 0.25 equiv. Na2CO3) (Fig. 3c; see ‘Base screening at lower nucleophile loading’ section in Supplementary Information for details).

Kinetic studies

The distinctive reactivity of alkyl sulfonyl fluorides in this cyclopropanation, along with the observed stereochemical outcomes, prompted us to examine the mechanism through experimental and computational techniques. We performed reaction progress kinetic analysis to determine key mechanistic features of the reaction from a minimal number of experiments47. First, we compared the standard reaction profile with a ‘same excess’ experiment that simulated 25% conversion (Fig. 4a). Time-shifting reveals that the two curves overlap as the reaction proceeds to approximately 50% conversion; beyond this point, a slight deviation emerges—an indication of either mild product inhibition or partial catalyst deactivation. To distinguish between the two possibilities, a third experiment was performed with product 3aa (83 mM) as an additive, and overlay with the same excess experiment confirmed mild catalyst deactivation. The lack of product inhibition is notable given the capacity of the product to bind to the catalyst in a polydentate fashion. To explore potential coordination between the product and catalyst further, 3aa was treated with Pd(OAc)2 (1 equiv.), resulting in the formation of N,N,C-palladacycle Pd–3aa in which the 3 °C (cyclopropyl)–H bond was cleaved (Fig. 4b) as characterized by X-ray crystallography48. Complex Pd–3aa proved to be catalytically competent under the standard reaction conditions, showing the reversibility of C–H activation, consistent with the lack of product inhibition. Next, to estimate the order of the reaction components, we performed a series of ‘different excess’ experiments (Fig. 4c). Considering that catalyst deactivation becomes more pronounced at higher conversion, we focused on the early stages of the reaction (<50% conversion). The variable time normalization analysis49 plot showed both alkene (1a) and nucleophile (2a) to be close to zero-order and Pd(OAc)2 to be close to first-order. Overall, the kinetic data are consistent with either oxidative addition or reductive elimination as the rate-determining step. To gain further insights into the rate-determining step, we conducted an Eyring analysis to obtain activation parameters (Fig. 4d). At temperatures close to standard conditions (70–100 °C), the experimental ΔS‡ was determined to be −25.8 e.u. and ΔH‡ to be 16.1 kcal mol−1 (ΔG‡80°C = 25.2 kcal mol−1). Given that large negative ΔS‡ values are commonly observed with bimolecular associative reactions50, and oxidative addition and reductive elimination of the current system are unimolecular steps, the data suggest potential desolvation and coordination of a ligand to the metal centre in traversing from the catalyst resting state to the rate-limiting transition state along the potential energy surface, which informed subsequent density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

a, Reaction progress kinetic analysis: same excess. b, Product binding experiments. c, Variable time normalization analysis. [Nuc] = [SO2F]. d, Eyring analysis.

Computational studies

DFT calculations with alkene 1a and alkyl sulfonyl fluoride nucleophile 2a as model substrates were performed to gain insights into various facets of the catalytic cycle, including the rate- and diastereoselectivity-determining steps (Fig. 5a). A particular focus was placed on the oxidative addition mechanisms and the origin of diastereoselectivity favouring the cis-cyclopropane product 3aa. Ligand exchange of the precatalyst Pd(OAc)2 with 1a forms π-alkene PdII complex Pd-1 with the 8-aminoquinoline directing group binding to the Pd in a bidentate fashion. Two competing anti-nucleopalladation transition states with the deprotonated nucleophile 2aʹ were considered (TS1 and TS1ʹ), which lead to two different diastereomers of the palladacycle intermediate (A and Aʹ, respectively). The deprotonation of 2a to form 2aʹ is expected to be facile based on its predicted aqueous pKa value of 7.75 for 2a and the experimental pKa of 6.83 for the analogous trifluoromethanesulfonyl51,52,53 (see Supplementary Fig. 10 for details). In the more stable transition state TS1, the largest substituent on the nucleophile, SO2F, is placed anti-periplanar with the alkene C=C bond, which could minimize steric strain, whereas in the less stable diastereomeric transition state TS1ʹ, the ester group is anti-periplanar with the C=C bond (Supplementary Fig. 4). This steric effect probably leads to the 3.4 kcal mol−1 higher energy of TS1ʹ than that of TS1. Although the formation of palladacycle A is kinetically favoured in the anti-nucleopalladation, diastereomers A and Aʹ rapidly epimerize via deprotonation of the acidic α-C–H. The Na2CO3-mediated deprotonation of A to form enolate Aʹʹ is predicted to be exergonic by 8.4 kcal mol−1 (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for details). This deprotonation process is in part entropy-driven as the enolate oxygen replaces the acetate ligand in A to form a six-membered chelation with the Pd centre.

a, DFT-computed reaction energy profile of the formation of cyclopropane 3aa. The DFT calculations were performed at the ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP/SMD(DMA)//B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d)–SDD(Pd) level of theory. The reaction energy profile was calculated at the experimental reaction temperature (80 °C). See the ‘Density functional theory (DFT) calculations’ section in Supplementary Information for computational details. All Gibbs free energies and enthalpies are with respect to Pd-1. b, Oxidative addition transition states. All activation barriers are with respect to the enolate resting state Aʹʹ.

Due to the ablation of the new α-stereocentre formed after nucleopalladation, under the Curtin–Hammett conditions, the product diastereoselectivity is determined in the subsequent steps. Our calculations indicate that the oxidative addition proceeds via an SN2-type stereoinvertive mechanism (TS2 and TS2ʹ). Other oxidative addition pathways, including the four- and three-centred C–S oxidative addition (TS4–TS6; Fig. 5b) and the S–F oxidative addition16,17 (Supplementary Fig. 6), were found to be less favourable. Subsequent reductive elimination from the PdIV intermediate B (TS3) is kinetically facile with a low barrier of 1.7 kcal mol−1 with respect to B, consistent with our recent computational study on the strain-release-promoted reductive elimination from PdIV to form cyclopropane rings31. The liberated SO2F− anion then decomposes to SO2 gas and F− anion, similar to previous reports by Bull and coworkers22,23. In situ 19F NMR spectroscopy monitoring indicates that F− is ultimately converted to bifluoride (FHF−) (see ‘Fluorine tracking experiments’ section in Supplementary Information for details). The computed reaction energy profile indicates that the irreversible intramolecular SN2-type oxidative addition (TS2) is the rate- and diastereoselectivity-determining step. The computed overall barrier from the Pd–enolate resting state Aʹʹ to TS2 (ΔG‡ = 28.7 kcal mol−1, ΔH‡ = 17.5 kcal mol−1) is in qualitative agreement with the experimentally determined activation parameters. The large negative activation entropy (ΔS‡ = − 31.7 e.u. compared with the experimental value of −25.8 e.u.) is primarily attributed to entropy loss during the association of an OAc− ligand upon reprotonation of the enolate resting state Aʹʹ. The computed diastereoselectivity indicates that the SN2-type oxidative addition via TS2 leading to the cis-cyclopropane product is 3.0 kcal mol−1 more favourable than the minor pathway via TS2ʹ leading to the trans product, which is consistent with the experimentally observed diastereoselectivity (>20:1 d.r.). TS2ʹ is probably destabilized by steric interactions between the acetate ligand and the ester group. The SN2-type oxidative addition with a phenyl ester (2f) had an increased barrier (ΔG‡ = 30.9 kcal mol−1) and lower computed diastereoselectivity (ΔΔG‡ = 1.2 kcal mol−1), attributed to steric repulsions between the directing group and the ester that stabilize the transition state leading to the cis-cyclopropane product (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Conclusion

A highly diastereoselective PdII/PdIV-catalysed cyclopropanation of unactivated alkenes with alkyl sulfonyl fluorides has been developed. The synthetic versatility of this method stems from the diverse array of pronucleophiles that are compatible. With internal alkenes, all cis-substituted cyclopropanes that are otherwise difficult to access can be prepared in one step. Kinetic experiments and DFT calculations indicate that the SN2-type oxidative addition is the rate- and diastereoselectivity-determining step.

Methods

Outside of the glovebox, the appropriate alkene substrate (0.1 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.01 mmol, 10mol%) and Na2CO3 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) were added to an oven-dried 1-dram (4 ml) vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar. The vial was then introduced into a nitrogen-filled glovebox antechamber. Once transferred inside the glovebox, alkyl sulfonyl fluoride (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv.) was added to the vial, followed by anhydrous DMA (0.3 ml, 0.33 M). The vial was sealed with a screw-top septum cap, removed from the glovebox and placed in a heating block that was preheated to 80 °C for 14 h. After this time period, the resulting mixture was filtered through a pad of celite. Saturated NaHCO3 solution (10 ml) was added to the filtrate, and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 2 ml). The combined organic layers were concentrated and purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using ethyl acetate/hexanes as the eluent.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Experimental procedures, characterization data for all new compounds and details for DFT calculations can be found in Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2171740 ((±)-3aa), CCDC 2345363 ((±)-3aj), CCDC 2351469 ((±)-3al′), CCDC 2345089 ((±)-4aa), CCDC 2376390 ((±)-4ad), CCDC 2367118 ((±)-4ah), CCDC 2394329 ((±)-6aa) and CCDC 2171739 (Pd–3aa); copies of the data can be obtained free of charge at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

References

Chinthakindi, P. K. & Arvidsson, P. I. Sulfonyl fluorides (SFs): more than click reagents? Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 3648–3666 (2018).

Zhao, C., Rakesh, K. P., Ravidar, L., Fang, W.-Y. & Qin, H.-L. Pharmaceutical and medicinal significance of sulfur (SVI)-containing motifs for drug discovery: a critical review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 162, 679–734 (2019).

Lou, T. S.-B. & Willis, M. C. Sulfonyl fluorides as targets and substrates in the development of new synthetic methods. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 146–162 (2022).

Narayanan, A. & Jones, L. H. Sulfonyl fluorides as privileged warheads in chemical biology. Chem. Sci. 6, 2650–2659 (2015).

Dong, J., Krasnova, L., Finn, M. G. & Sharpless, K. B. Sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEx): another good reaction for click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9430–9448 (2014).

Barrow, A. S. et al. The growing applications of SuFEx click chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4731–4758 (2019).

Tribby, A. L., Rodríguez, I., Shariffudin, S. & Ball, N. D. Pd-catalyzed conversion of aryl iodides to sulfonyl fluorides using SO2 surrogate DABSO and Selectfluor. J. Org. Chem. 82, 2294–2299 (2017).

Kwon, J. & Kim, B. M. Synthesis of arenesulfonyl fluorides via sulfuryl fluoride incorporation from arynes. Org. Lett. 21, 428–433 (2019).

Laudadio, G. et al. Sulfonyl fluoride synthesis through electrochemical oxidative coupling of thiols and potassium fluoride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 11832–11836 (2019).

Lee, C., Ball, N. D. & Sammis, G. M. One-pot fluorosulfurylation of Grignard reagents using sulfuryl fluoride. Chem. Commun. 55, 14753–14756 (2019).

Smedley, C. J. et al. Diversity oriented clicking (DOC): divergent synthesis of SuFExable pharmacophores from 2-substituted-alkynyl-1-sulfonyl fluoride (SASF) hubs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12460–12469 (2020).

Erchinger, J. E. et al. EnT-mediated N–S bond homolysis of a bifunctional reagent leading to aliphatic sulfonyl fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2364–2374 (2023).

Chinthakindi, P. K., Kruger, H. G., Govender, T., Naicker, T. & Arvidsson, P. I. On-water synthesis of biaryl sulfonyl fluorides. J. Org. Chem. 81, 2618–2623 (2016).

Cherepakha, A. Y. et al. Hetaryl bromides bearing the SO2F group—versatile substrates for palladium-catalyzed C–C coupling reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 6682–6692 (2018).

Lou, T. S.-B. & Willis, M. C. Arylsulfonyl fluoride boronic acids: preparation and coupling reactivity. Tetrahedron 76, 130782 (2020).

Chatelain, P. et al. Desulfonative Suzuki–Miyaura coupling of sulfonyl fluorides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 25307–25312 (2021).

Zhang, G., Guan, C., Zhao, Y., Miao, H. & Ding, C. “Awaken” aryl sulfonyl fluoride: a new partner in the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction. New J. Chem. 46, 3560–3564 (2022).

Nielsen, M. K., Ugaz, C. R., Li, W. & Doyle, A. G. PyFluor: a low-cost, stable, and selective deoxyfluorination reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9571–9574 (2015).

Chen, Q., Mayer, P. & Mayr, H. Ethenesulfonyl fluoride: the most perfect Michael acceptor ever found? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12664–12667 (2016).

Qin, H.-L., Zheng, Q., Bare, G. A. L., Wu, P. & Sharpless, K. B. A Heck–Matsuda process for the synthesis of β-arylethenesulfonyl fluorides: selectively addressable bis-electrophiles for SuFEx click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14155–14158 (2016).

Zha, G.-F. et al. Palladium-catalyzed fluorosulfonylvinylation of organic iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 4849–4852 (2017).

Rojas, J. J. et al. Amino-oxetanes as amide isosteres by an alternative defluorosulfonylative coupling of sulfonyl fluorides. Nat. Chem. 14, 160–169 (2022).

Symes, O. L. et al. Harnessing oxetane and azetidine sulfonyl fluorides for opportunities in drug discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 35377–35389 (2024).

Hawkins, J. M., Lewis, T. A. & Raw, A. S. Substituent effects on sulfonate ester based olefinations. Tetrahedron Lett. 31, 981–984 (1990).

Kagabu, S., Hara, K. & Takahashi, J. Alkene formation through condensation of phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride with carbonyl compounds. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 408–410 (1991).

Kagabu, S. et al. Reaction of phenyl- and alkoxycarbonylmethanesulfonyl fluoride with activated haloalkanes. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 129, 435–439 (1992).

Górski, B., Talko, A., Basak, T. & Barbasiewicz, M. Olefination with sulfonyl halides and esters: scope, limitations, and mechanistic studies of the Hawkins reaction. Org. Lett. 19, 1756–1759 (2017).

Górski, B. et al. Olefination with sulfonyl halides and esters: E-selective synthesis of alkenes from semistabilized carbanion precursors. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 1774–1784 (2018).

Tryniszewski, M., Basiak, D. & Barbasiewicz, M. Olefination with sulfonyl halides and esters: synthesis of unsaturated sulfonyl fluorides. Org. Lett. 24, 4270–4274 (2022).

Liang, H. et al. Amidation of β-keto sulfonyl fluorides via C–C bond cleavage. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 27, e202400391 (2024).

Ni, H.-Q. et al. Anti-selective cyclopropanation of nonconjugated alkenes with diverse pronucleophiles via directed nucleopalladation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 24503–24514 (2024).

Davies, H. M. L. & Antoulinakis, E. Intermolecular metal-catalyzed carbenoid cyclopropanations. Org. React. 57, 1–326 (2001).

Lebel, H., Marcoux, J.-F., Molinaro, C. & Charette, A. B. Stereoselective cyclopropanation reactions. Chem. Rev. 103, 977–1050 (2003).

Maas, G. Ruthenium-catalysed carbenoid cyclopropanation reactions with diazo compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 33, 183–190 (2004).

Ford, A. et al. Modern organic synthesis with α-diazocarbonyl compounds. Chem. Rev. 115, 9981–10080 (2015).

Ballav, N., Giri, C. K., Saha, S. N., Mane, M. V. & Baidya, M. Empowering diastereoselective cyclopropanation of unactivated alkenes with sulfur ylides through nucleopalladation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 13017–13026 (2025).

Lévesque, É., Goudreau, S. R. & Charette, A. B. Improved zinc-catalyzed Simmons–Smith reaction: access to various 1,2,3-trisubstituted cyclopropanes. Org. Lett. 16, 1490–1493 (2014).

Yasui, M., Ota, R., Tsukano, C. & Takemoto, Y. Synthesis of cis-/all-cis-substituted cyclopropanes through stereocontrolled metalation and Pd-catalyzed Negishi coupling. Org. Lett. 20, 7656–7660 (2018).

Piou, T., Romanov-Michailidis, F., Ashley, M. A., Romanova-Michaelides, M. & Rovis, T. Stereodivergent rhodium(III)-catalyzed cis-cyclopropanation enabled by multivariate optimization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9587–9593 (2018).

Phipps, E. J. T. & Rovis, T. Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H activation-initiated directed cyclopropanation of allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6807–6811 (2019).

Costantini, M. & Mendoza, A. Modular enantioselective synthesis of cis-cyclopropanes through self-sensitized stereoselective photodecarboxylation with benzothiazolines. ACS Catal. 11, 13312–13319 (2021).

Mato, M., Herlé, B. & Echavarren, A. M. Cyclopropanation by gold- or zinc-catalyzed retro-Buchner reaction at room temperature. Org. Lett. 20, 4341–4345 (2018).

James, G. T. Inactivation of the protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride in buffers. Anal. Biochem. 86, 574–579 (1978).

Palermo, A. F., Chiu, B. S., Patel, P. & Rousseaux, S. A. Nickel-catalyzed reductive alkyne hydrocyanation enabled by malononitrile and a formaldehyde additive. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24981–24989 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Diastereoselective synthesis of cyclopropanes bearing trifluoromethyl-substituted all-carbon quaternary centers from 2-trifluoromethyl-1,3-enynes beyond fluorine elimination. Chem. Commun. 55, 3879–3882 (2019).

Antermite, D., Affron, D. P. & Bull, J. A. Regio- and stereoselective palladium-catalyzed C(sp3)–H arylation of pyrrolidines and piperidines with C(3) directing groups. Org. Lett. 20, 3948–3952 (2018).

Blackmond, D. G. Reaction progress kinetic analysis: a powerful methodology for mechanistic studies of complex catalytic reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4302–4320 (2005).

Hoshiya, N., Kobayashi, T., Arisawa, M. & Shuto, S. Palladium-catalyzed arylation of cyclopropanes via directing group-mediated C(sp3)–H bond activation to construct quaternary carbon centers: synthesis of cis- and trans-1,1,2-trisubstituted chiral cyclopropanes. Org. Lett. 15, 6202–6205 (2013).

Nielsen, C. D.-T. & Burés, J. Visual kinetic analysis. Chem. Sci. 10, 348–353 (2019).

Anslyn, E. V. & Dougherty, D. A. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry (Univ. Science Books, 2006).

Goumont, R., Magnier, E., Kizilian, E. & Terrier, F. Acidity inversions of α-NO2 and α-SO2CF3 activated carbon acids as a result of contrasting solvent effects on transfer from water to dimethyl sulfoxide solutions. J. Org. Chem. 68, 6566–6570 (2003).

Wagen, C. C. & Wagen, A. M. Efficient and accurate pKa prediction enabled by pre-trained machine-learned interatomic potentials. Preprint at ChemRxiv https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-8489b (2024).

Anstine, D. M., Zubatyuk, R. & Isayev, O. AIMNet2: a neural network potential to meet your neutral, charged, organic, and elemental-organic needs. Chem. Sci. 16, 10228–10244 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the US National Science Foundation (CHE-2046286, K.M.E.), the US National Institutes of Health (R35 GM128779, P.L.), Pfizer, Inc. and Enamine Ltd. We thank the David C. Fairchild Endowed Fellowship Fund for a graduate fellowship (Y.C.), the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT5-RGJ63023-177) for a graduate fellowship (W.R.), the Skaggs Endowed Fellowship programme for a graduate fellowship (Z.R.), the Schimmel Family Endowed Fellowship Fund for a graduate fellowship (A.V.R.D.L.) and the EPSRC for studentship (EP/S023828/1) funding through the OxICFM CDT (J.J.C.S.). We further thank J. Bailey (UCSD), M. Gembicky (UCSD), S. Yang (Scripps Research) and S. Shishkina (IOC, Kyiv) for X-ray crystallographic analysis. We are grateful to J. S. Chen, B. B. Sanchez, Q. N. Wong and J. Lee (Scripps Research Automated Synthesis Facility) for assistance with supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis. DFT calculations were carried out at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing and Data and the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) programme, supported by NSF award numbers OAC-2117681, OAC-1928147 and OAC-1928224. We also thank J. Yu (Scripps Research), M. Deng (Scripps Research) and E. M. Di Tommaso (Scripps Research) for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.R., K.M.E. and K.B.S. conceived the project. Y.C. and W.R. optimized the reaction. Y.C. evaluated the substrate scope. T.M.A. and P.L. carried out computation work. Y.C., T.S. and P.K.M. carried out the synthesis of alkyl sulfonyl fluoride reagents. Y.C., Z.R. and H.-Q.N. carried out the synthesis of alkene starting materials. A.V.R.D.L. and J.J.C.S. carried out kinetic studies under the guidance of D.G.B. Y.C., T.S. and P.K.M. carried out gram-scale synthesis. P.K.M., R.P.L., S.Y., I.J.M., P.L., K.B.S. and K.M.E. directed the research. Y.C., T.M.A., A.V.R.D.L., P.L. and K.M.E. wrote the paper with input from all other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Synthesis thanks Lucía Morán-González and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Thomas West, in collaboration with the Nature Synthesis team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Experimental details, Supplementary Figs. 1–12 and Tables 1–36.

Supplementary Data 1

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-3aa, CCDC 2171740.

Supplementary Data 2

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-3aj, CCDC 2345363.

Supplementary Data 3

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-3al′, CCDC 2351469.

Supplementary Data 4

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-4aa, CCDC 2345089.

Supplementary Data 5

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-4ad, CCDC 2376390.

Supplementary Data 6

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-4ah, CCDC 2367118.

Supplementary Data 7

Crystallographic data for compound (±)-6aa, CCDC 2394329.

Supplementary Data 8

Crystallographic data for compound Pd–3aa, CCDC 2171739.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Y., Rodphon, W., Alturaifi, T.M. et al. Alkyl sulfonyl fluorides as ambiphiles in the stereoselective palladium(II)-catalysed cyclopropanation of unactivated alkenes. Nat. Synth 5, 281–289 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-025-00925-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-025-00925-1