Abstract

Bridging the gap between farmers’ local knowledge and scientific evidence, we examine adaptation strategies of smallholder rice farmers in coastal areas, where salinity intrusion increasingly threatens food security. Drawing on surveys of 200 farmers and 60 field trials in four salinity-prone regions, research highlights a strong alignment between farmers’ perceptions and scientific evidence. Most farmers (58.5%) reported rising salinity, largely due to shrimp farming, and 93% cited salinity and freshwater scarcity as major constraints during the Boro season. In response, farmers adopted salt-tolerant varieties, freshwater irrigation, and adjusted transplanting times. Early transplanting emerged as the most effective, reducing salinity stress during reproductive stage and improving yields. Field data confirmed its advantage over mid and late transplanting. Findings underscore the value of integrating local knowledge into adaptation research and policy, promoting cost-effective strategies. Strengthening such approaches through targeted extension and support can build resilience and contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salinity intrusion is a growing threat to rice production in the coastal regions of Bangladesh, where millions of smallholder farmers rely on rice as both a staple crop and a primary source of income. In Bangladesh, salinity reduces rice production by 20–30%1. In some areas of Vietnam, it leads to agricultural failure, reduced rice productivity, and an average yield loss of 0.164 tons per hectare2,3,4. Over recent decades, salinization has intensified due to anthropogenic activities such as shrimp farming (because of the prolonged submergence of farmlands with saline water for shrimp farming)5,6, along with natural drivers like tidal flooding and declining freshwater flow7. Despite several interventions—including the promotion of salt-tolerant varieties and coastal embankments8,9—salinity continues to undermine food security, raising concerns about the appropriateness and uptake of existing adaptation strategies.

Understanding farmers’ perceptions of salinity is critical for developing locally relevant solutions. These farmers directly experience salinity stress in their fields and rely on experiential knowledge to make agricultural decisions. Yet, their perspectives are often overlooked in research and policy, resulting in a disconnect between top-down interventions and grassroots realities10,11,12. Most national adaptation frameworks emphasize technical or infrastructural responses—such as polders or breeding programs—without fully accounting for the dynamic and localized ways that farmers interpret and respond to salinity.

While there is growing literature on climate change impacts on agriculture in Bangladesh13,14, relatively few studies have examined salinity from the lens of farmer perception, particularly during the Boro rice production season, which is highly vulnerable due to its dependence on irrigation during15,16. Boro rice is also the country’s most productive season, making it critical for national food security. However, when salinity coincides with sensitive reproductive stages, it can cause substantial yield loss17,18.

Furthermore, salinity is often treated as an agronomic or technical issue, but in practice, it is a slow-onset, spatially variable hazard19, with social, economic, and ecological dimensions. Unlike acute disasters such as floods or cyclones, salinity’s gradual progression makes it more difficult to address through conventional disaster management approaches20,21. Current policies tend to focus on hard engineering, but long-term resilience may depend more on locally-grounded adaptation strategies22,23.

A small number of studies have explored farmer perceptions of salinity in coastal Bangladesh16,24, but these have been geographically limited or focused primarily on water quality and health. There remains a lack of comprehensive research linking farmer perceptions of salinity’s causes, timing, and effects on crop development stages with actual field measurements and outcomes.

This study aims to address this gap by combining farmer surveys and field trials in four coastal sub-districts (upazilas) to (1) document farmers’ perceptions of salinity and its impacts on Boro rice, (2) assess their adaptation strategies—particularly related to salinity impact, transplanting time and variety selection, and (3) evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies through scientific measurements. By integrating farmer knowledge with empirical data, we aim to validate low-cost, locally practiced methods that can inform more inclusive and evidence-based adaptation policies. By integrating farmers’ firsthand experiences—referred to as “victim knowledge” with scientific evidence, the system will strengthen resilience in climate-vulnerable agricultural communities. The results of this study contribute to the discourse on climate adaptation, offering insights to inform policies and practices that more effectively support smallholder rice farmers in Bangladesh.

Results

Demographic characteristics of rice farmers

Table 1 provides demographic details of the farmers interviewed across the study areas. Educational levels varied significantly among the farmers, with those in Kaliganj averaging two more years of schooling than farmers in the other locations. Additionally, the average farm size in Kaliganj (46 decimals) was significantly larger than in the other areas. Although rice cultivation in Bangladesh includes three seasons, the farmers in all study locations cultivated rice only in the T. Aman and Boro seasons. Debhata farmers allocated a significantly larger area to rice during the Boro season compared to the other locations. Significant differences were observed in land ownership across the regions (F = 3.96, df = 3, P = 0.009), farmers in Kaliganj and Debhata owned more land (74.34 decimals on average) than those in Asashuni and Koyra, where the average land ownership was 50.33 and 39.77 decimals, respectively. Monthly income was also significantly differed (F = 10.2, df = 3, P < 0.001) and higher for farmers in Debhata (US$ 153.90) and Kaliganj (US$ 150.55) than in Asashuni (US$ 106.87) and Koyra (US$ 123.46). While the average age of the interviewed farmers was similar across locations (45 ± 1 years), farmers in Asashuni (22.43 years) and Koyra (21.7 years) had more farming experience than those in Kaliganj (11.8 years) and Debhata (12.9 years).

Table 2 shows the variability in educational qualifications by age group across the four locations. Younger farmers (30–40 years) were generally better educated than older farmers, with higher illiteracy rates among the oldest age groups. On average, farmers had secondary education, although 21% could only sign their name with only older age group, indicating limited literacy.

Farmers’ perceptions of the context of salinization in the coastal areas

Table 3 presents farmers’ perceptions regarding trends in salinity, both past and present, as well as their views on the causes of increased salinity in their fields. There was a significant difference among farmers from the four study locations regarding their perceptions of salinity trend (χ2 = 147.4; P < 0.001). Across all locations, 92.5% of surveyed farmers reported that salinity had increased in their fields, while 7.5% stated it had decreased over the past 20 years. This contrasts sharply with perceptions from 20 years ago, when only 11.5% viewed salinity as high and 88.5% regarded it as low.

Shrimp farming was widely identified as the primary driver of increased salinity, with 83.5% of farmers across locations attributing salinization to this factor, while only 13.0% cited natural events, such as cyclones (Sidr, Aila), as contributing factors (Table 3). This perception was significantly varied to locations (χ2 = 38.83; P < 0.01). In Kaliganj, 94.4% of participants attributed salinity increases to shrimp farming, 2.8% to cyclones, and 2.8% to river siltation. Similarly, in Debhata, 87.5% of participants identified shrimp farming as the main cause, with 9.4% attributing it to cyclones. In Koyra, 59.6% of farmers saw shrimp farming as the primary cause, while 32.7% cited cyclones, and 3.5% noted embankment erosion as contributing to increased salinity. In Assasuni, over 95% of farmers identified shrimp farming as the primary cause of current salinity levels, with only a small proportion attributing it to cyclones. These findings suggest a strong consensus among farmers that shrimp farming is a major driver of salinity in coastal agricultural fields, with natural hazards playing a secondary role.

Farmers’ perceptions of salinity problems in Boro season rice cultivation

The area selected for this study is featured during the Boro season (Table 4), rice growers reported several challenges, including salinity, inadequate irrigation water, pests and diseases, and unpredictable rainfall. Across all study areas, the vast majority of farmers (93%) viewed the combination of salinity and water scarcity as the most pressing issue during Boro rice cultivation, followed by irrigation alone (4%) and salinity alone (3%) (Fig. 1).

Farmers identified the reproductive stage of rice—particularly the panicle initiation, booting, and flowering stages—as the most sensitive to salinity, with vegetative (seedling and tillering) and ripening stages following in susceptibility (Fig. 2). Their perception was significantly differed among the study regions (χ2 = 127.3; P < 0.001). Among reproductive stages, the flowering stage was considered the most vulnerable. In Kaliganj, 47.2% of farmers perceived the flowering stage as the most salinity-sensitive, followed by 33.3% who viewed the booting stage as highly susceptible, with fewer farmers citing the panicle initiation, seedling, and tillering stages. Assasuni and Debhata displayed similar trends, with 46.9% of farmers identifying the flowering stage as most vulnerable, and 28.1% and 18.8% indicating booting as susceptible. In contrast, Koyra farmers had a different perspective: 26.9% and 23.1% identified the booting and flowering stages, respectively, as the most sensitive to salinity (Fig. 2).

Across all locations, 60% of farmers reported that salinity led to empty grains in rice plants, 25% observed reduced panicle exertion, 21% noted stunted plants, and 10.5% mentioned that salinity caused the upper leaves to turn white (Table 4). There were, however, significant differences in perceptions of salinity damage across the study areas (χ2 = 163.3; P < 0.001). In Assasuni, 53.1% of farmers cited empty grains as a result of salinity, followed by those in Debhata, Koyra, and Kaliganj. In terms of reduced panicle exertion, 39.1% of farmers in Debhata, 26.6% in Kaliganj, 9.3% in Koyra, and 3.1% in Assasuni reported this as a consequence of salinity (Table 4). These findings underscore the significant impact of salinity on rice cultivation, particularly during critical reproductive stages, and highlight variation in farmers’ perceptions of salinity-related damage across different locations.

Farmers’ adaptation strategies for addressing salinity in Boro rice cultivation

In the coastal regions of Bangladesh, farmers employ a range of adaptation strategies to manage salinity during the Boro rice season and their adaptive approaches significantly varied among locations (χ2 = 65.20; P < 0.001). Most rice farmers in Kaliganj (72.2%) utilized salt-tolerant rice varieties along with fresh water for irrigation, while the remaining farmers transplanted early and irrigated with fresh water to mitigate high salinity during the reproductive stage (Table 5). A similar pattern was observed in Debhata, where 76.6% of farmers grew salt-tolerant rice cultivars and used fresh water irrigation, and only 17.2% transplanted early with fresh water irrigation (Table 5).

In contrast, different approaches were noted in Assasuni and Koyra. In Assasuni, 37.5% of farmers transplanted early and irrigated with fresh water, while 35.4% grew salt-tolerant varieties. Farmers in Koyra showed the highest percentage of those relying solely on fresh water irrigation, followed by those growing salt-tolerant varieties, early transplanting with fresh water, and applying ash/K fertilizer along with fresh water irrigation. These findings indicate that, regardless of location, farmers commonly combine fresh water irrigation with other methods for salinity management (Table 5), with the most widely adopted approach being salt-tolerant varieties combined with fresh water irrigation. However, across locations 22.5% of farmers used early transplanting schedule in combination with fresh water supply.

Transplanting date influences the salinity level at sensitive stages of rice plant

We assessed the three different transplanting date for avoiding high salinity level at plant sensitive stage. Model results show that transplanting schedule significantly reduce the risk of higher salinity problem at most sensitive stages of rice. Early transplanting date reduced the risk of rice plants facing high salinity stress at reproductive stage (Fig. 3). Late transplanting has a positive effect on salinity (Estimate = 1.5903, p = 0.0119), meaning late transplanting is associated with higher salinity levels during the vegetative stage compared to the early schedule. Mid transplanting also significantly increases salinity (Estimate = 2.5556, p = 0.00251) and shows a stronger effect than late transplanting. The significance levels and estimates indicate that adjusting transplanting time could be a practical way to manage salinity levels at plant stages. Similar effects were observed during reproductive stage. Both late (Estimate = 2.7573, p = 0.0032), and mid transplanting times are significant contributors to increased salinity during the reproductive stage, with mid transplanting having the strongest association (Estimate = 3.0161, p = 0.00025). In summary, comparing with early transplanting date, both late and mid transplanting times significantly increase salinity levels during both the vegetative and reproductive stage, with the highest increase associated with mid transplanting. The significant effects of transplanting time imply that adjusting transplanting schedules could impact salinity management in crops, especially during critical growth stages. This insight could be useful for agricultural planning aimed at optimizing plant health under variable salinity conditions.

Transplanting date influences the salinity level impacting rice yield

Figure 4 shows the effect of transplanting date on the yield of rice. The model indicates that early transplanting significantly improves yield, with the highest estimated yield of 6.28 t/ha (df = 45, t = 25.886, P < 0.001). In comparison, late transplanting results in a notably lower yield, with an estimated reduction of 1.31 t/ha (df = 45, t = −3.311, P = 0.0017). Mid transplanting shows a small, non-significant yield decrease of 0.59 t/ha relative to early transplanting (df = 45, t = −1.622, P = 0.113), indicating no substantial difference from either early or late transplanting. These results suggest that adjusting transplanting timing earlier in the season may enhance yield. Furthermore, the negligible variance observed in location (3.839e-21) and field (0.000e) effects suggests consistent results across sites, warranting further investigation into the factors influencing these effects.

Discussion

This study reveals how smallholder rice farmers in coastal Bangladesh perceive and respond to increasing salinity during Boro season cultivation. Farmers’ strong awareness of salinity’s effects—particularly during critical reproductive stages—demonstrates their close observation and accumulated experiential knowledge. These perceptions are not only valid but also highly aligned with agronomic findings and field measurements from this study, highlighting the importance of integrating farmers’ insights into adaptation planning. The variation in farmers’ educational levels, farm sizes, and incomes across locations reveals socioeconomic differences that likely influence adaptive capacity. Higher education and income levels in Kaliganj and Debhata, for example, may facilitate better access to resources, information, and adaptive options. This supports both earlier and recent findings that wealth, education, and farm size are positively associated with increased climate resilience and the capacity to adopt adaptation strategies in climate-vulnerable communities16,25,26,27,28.

This study found that a significant majority of rice farmers (92.5%) across all four study locations reported a noticeable increase in soil salinity over time, with 88.5% perceiving salinity levels to be higher now than they were 20 years ago. These perceptions were consistent regardless of socioeconomic status or age, although farmers with higher education and longer farming experience demonstrated a more nuanced awareness of salinity-related land degradation, a pattern echoed in earlier findings29.

Notably, more than 83% of respondents attributed the rise in salinity primarily to shrimp farming, while relatively few cited natural events such as cyclones or coastal flooding. This attribution aligns with prior studies identifying shrimp aquaculture as a dominant driver of coastal salinization in Bangladesh5,30. Farmers’ emphasis on anthropogenic causes—rather than natural disasters—highlights their understanding of how land-use decisions and water management practices influence agricultural sustainability. This view is also supported by evidence that shrimp cultivation has expanded rapidly in coastal areas since the 1980s, often replacing traditional rice fields31.

Perceptions of salinity causes varied slightly by location, reflecting the socially constructed nature of disaster understanding, which is shaped by local experience and livelihood context32,33. For instance, communities with greater exposure to aquaculture infrastructure were more likely to associate salinity with human-induced changes, whereas areas with recent cyclone damage showed mixed attribution. As rice cultivation declines due to salinity intrusion, some farmers are shifting to more profitable but environmentally harmful saltwater shrimp farming16,34. This has resulted in increasing tension among rice, shrimp, and salt producers, as salinization threatens long-term agricultural productivity and food security35. In this context, land-use change not only alters ecological dynamics but also contributes to resource conflicts and reduced resilience of smallholder farming systems.

Given these interlinked challenges, there is an urgent need for integrated land-use planning that balances economic viability with environmental sustainability. Recent studies27,36 have called for suitability-based land zoning, a strategy also endorsed by the Bangladesh government37,38. Such zoning would delineate areas best suited for rice, shrimp, or mixed farming based on biophysical conditions and salinity thresholds, supported by participatory planning processes involving all stakeholders.

Effective land-use governance must go beyond technical zoning to incorporate local knowledge and perceptions, ensuring that farmers’ lived experiences inform sustainable resource management. Their awareness of the salinity problem—its timing, causes, and consequences—provides a valuable foundation for designing inclusive policies that address the root causes of degradation while supporting climate-resilient livelihoods.

Our study revealed that farmers consistently identified increased salinity and limited availability of irrigation water as the two primary challenges affecting rice cultivation during the Boro season (Fig. 2). These challenges pose significant threats to rice production in Bangladesh’s coastal regions, as documented in earlier and recent studies39,40,41. Scientific literature corroborates farmers’ observations of declining freshwater resources and reduced precipitation, factors that exacerbate salinity problems and negatively impact rice yields5,42.

Farmers specifically perceive that high salinity during the reproductive stages of rice—the most sensitive period—leads to reduced panicle extrusion (heading), white panicles, and empty grains, all contributing to substantial yield losses (Table 4). This aligns with agronomic research showing that elevated salinity inhibits shoot and root growth, decreases photosynthetic and transpiration rates, lowers chlorophyll concentration, and impairs stomatal conductance, ultimately causing significant yield reductions17,43,44,45. Our findings also highlight farmers’ particular concern about salinity impacts during early reproductive stages. While rice is also sensitive to salinity during vegetative growth46,47, farmers in our study showed comparatively less concern about effects at the seedling stage.

Farmers’ perceptions of salinity correspond closely to seasonal salinity patterns, which increase through March and peak between April and May48, coinciding with the reproductive phase of late-transplanted rice in coastal Bangladesh49,50. Such correspondence suggests that farmers’ understanding of salinity issues is grounded in real-time field observations. The strong alignment between their perceptions and scientific evidence indicates a nuanced and practical knowledge of salinity stress in rice cultivation51,52,53.

Salinity was most frequently reported as a challenge during the reproductive stage, particularly panicle initiation, booting, and flowering. These stages are physiologically vulnerable due to increased water and nutrient demands18,54. Interestingly, farmers in Koyra identified booting as the most salinity-sensitive stage, differing slightly from other regions—possibly due to localized environmental conditions or crop damage experience. This mirrors findings by Miah et al51,55. and others, emphasizing the role of experiential knowledge in guiding adaptive strategies under salinity stress.

The reported symptoms—empty grains, reduced panicle exertion, and stunted plants—reflect significant yield loss potential, directly threatening food security and farmer livelihoods. These findings are consistent with recent studies linking salinity stress to decreased rice productivity in coastal Bangladesh56,57,58,59. The physiological impacts reported by farmers reinforce the need for location-specific, stage-sensitive salinity management strategies targeting critical growth phases of rice.

To cope with increasing salinity, farmers adopt strategies such as early transplanting, using salt-tolerant rice varieties, and applying freshwater irrigation (Table 5). Over 50% use salt-tolerant varieties with freshwater, while 21.5% depend solely on freshwater irrigation. Early transplanting, practiced by 22.5% of farmers, helps avoid peak salinity during sensitive reproductive stages, improving yields. Our field trials confirmed that adjusting transplanting dates significantly reduces salinity exposure at critical growth phases (Fig. 3). These practices align with adaptive responses reported in other salinity-prone regions53,60,61,62. To support farmers, BRRI has developed salt-tolerant rice varieties such as BRRI dhan47, BRRI dhan67, BRRI dhan73, BRRI dhan97, BRRI dhan99, and BRRI dhan112, capable of tolerating salinity levels of 6–10 dS/m15,63,64.

Field data and farmer insights consistently showed that early transplanting helps rice avoid peak salinity during critical growth stages, especially the reproductive phase, which begins around 90–95 days after germination and lasts about 30–35 days53. This timing typically bypasses peak salinity, which often occurs in April in coastal regions62 (Sarker et al., 2024). Early transplanting, combined with the use of salt-tolerant varieties and freshwater irrigation—particularly effective in Kaliganj and Debhata—significantly reduced salinity stress and improved outcomes. Adjusting transplanting dates enables farmers to avoid high-salinity windows, minimizing damage to crop development30,63. These adaptive practices, rooted in local knowledge, offer practical and low-cost solutions aligned with traditional farming systems. The reliance on salt-tolerant varieties and freshwater access underscores the importance of varietal selection and irrigation timing as key resilience strategies for smallholder farmers.

Our data confirm that transplanting schedules significantly affect salinity exposure during sensitive growth stages. Early transplanting reduced salinity stress during reproductive stages, while mid and late transplanting increased salinity levels during both vegetative and reproductive phases. Yield data support this finding—early-transplanted fields consistently achieved the highest yields across all sites (Fig. 4), indicating the broad applicability of this approach as a climate-resilient and cost-effective strategy in salinity-prone areas of coastal Bangladesh.

To achieve UN sustainable development goals (SDGs), Bangladesh has several important policies such as NAPA 2009; BCCSAP 2009; PPB 2012; NSDS 2013; and NAP 2018 which are specifically designed to promote sustainable agricultural production. The development of these policies has actively involved stakeholders across national, local, and regional levels, with a focus on identifying key agricultural vulnerabilities, particularly in coastal regions. Each of these policy frameworks highlights coastal salinity as a major challenge to sustainable rice production.

Although local stakeholders were involved in identifying issues during the formulation of these policies, most adaptation strategies have been established primarily at the national level. As a result, farmers’ views/knowledge on salinity and their local adaptation practices have largely been overlooked in policy formulation. For instance, while BCCSAP and NAPA have prioritized projects to address salinity, and PPB, NSDS, and NAP have included chapters on breeding salt-tolerant crop varieties, crop diversification, and strengthening polders and embankments, these efforts primarily target salinity in Bangladesh’s coastal areas8,9,65,66. Consequently, government agencies have developed and promoted several salt-tolerant rice varieties. However, although these varieties can withstand salinity up to 12.0 dS/m during the vegetative phase (seedling to tillering)15,64,67, their tolerance decreases to 8.0 dS/m during the reproductive phase. In the study area, salinity levels often exceed this threshold during the reproductive stage, which farmers recognize as the most vulnerable phase for rice. Future breeding efforts for salt-tolerant rice should therefore aim to enhance salinity tolerance specifically during the reproductive phase to address these local conditions effectively.

Farmers identified shrimp farming as the key driver of salinity increase. While government-promoted engineering solutions like polders and reinforced embankments8,65,68 may help reduce saltwater intrusion from storm surges, these strategies are less effective in cases where land use shifts to saltwater-dependent activities, such as shrimp production69,70. Our study highlights the need for integrated policy and research efforts that incorporate the perspectives of diverse farming groups; rice, shrimp, and salt farmers, to address local needs while also aligning with national SDG targets.

We identified a low-cost effective adaptation strategy (early transplanting schedule) which has currently been adopted by only 22.5% of affected farmers. This indicates that this low-cost adaptive strategy could be shared across coastal regions of Bangladesh through extension efforts to showcase their effectiveness. Developing salt-tolerant varieties is also a good option and is well-accepted by farmers but is expensive and takes many years to implement. To more quickly address farmers’ concerns, adjusting planting time field trials and coordinated educational programs should be implemented in areas affected by salinity. Financial support is required to replicate this adaptation strategy and trials should be conducted jointly with farmers because innovations developed jointly by farmers and researchers have greater potential to be adopted by more farmers.

Our findings showed that most of the farmers (73.5%) did not receive any guidelines (such as early transplanting to avoid high salinity periods during rice’s reproductive growth stages, or salt-tolerant rice seedlings) from government agencies for mitigating salinity in staple food crop cultivation. In addition, more than 77% of farmers highlighted their demand to supply fresh water for irrigating rice. Therefore, integrating farmers’ insights and concerns into policy could effectively shape future research, extension services, and long-term adaptation planning. This approach would support efforts to achieve UN sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly in poverty reduction (SDG-1), food and nutrition security (SDG-2), and overall public health (SDG-3).

This study underscores that adaptive management, grounded in local knowledge and supported by scientific insights, offers promising avenues for mitigating salinity stress in coastal rice farming. The emphasis on early transplanting, salt-tolerant varieties, and sustainable water management can support farmers in enhancing resilience and sustaining rice production under escalating climate pressures. Policies promoting awareness of climate-resilient practices, educating about instant management practices, combined with access to financial and technical support, could empower farmers to implement effective salinity management strategies25. Furthermore, limiting shrimp farming in vulnerable agricultural areas or enforcing sustainable aquaculture practices could mitigate salinity intrusion and reduce long-term soil degradation in coastal farming systems. Future research could explore policy interventions and long-term monitoring of these strategies’ effectiveness and investigate additional location-specific factors influencing adaptive capacity in coastal agricultural systems.

Based on farmer survey findings and field trial results, the following policy actions are recommended to enhance rice production and farmer resilience in salinity-affected areas:

-

Develop region-specific transplanting calendars and integrate them into Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) advisory services.

-

Expand certified seed production and distribution of BRRI-released salt-tolerant varieties (e.g., BRRI dhan67, BRRI dhan112).

-

Conduct farmer field schools and on-farm demonstrations on seedling preparation, fertilizer management, and water control under saline conditions.

-

Targeted training equips farmers with practical strategies that align with local challenges.

-

Incorporate insights from this study—such as vulnerable crop stages and desired government support—into training materials and seasonal advisories.

-

Aligning extension messages with farmers’ real-world perceptions increases adoption and impact.

-

Deploy portable EC meters through local DAE offices or cooperatives and share real-time salinity updates via SMS or village meetings. Timely salinity information helps farmers make informed management decisions.

Methods

Study sites

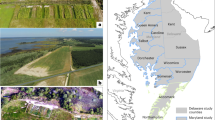

Before commencing field trials in collaboration with farmers, we conducted interviews with 200 smallholder rice farmers to understand their perceptions of climate change, particularly regarding salinity issues in food production, as well as their adaptation strategies. It is important to note that rice is the staple food for the local population and is the primary crop cultivated in the study regions. We selected four upazilas (Kaliganj, Debhata, Asashuni, and Koyra) from two administrative districts (Satkhira and Khulna) in Bangladesh. These sites were purposively selected based on three key criteria: (i) high salinity exposure, as indicated by long-term data from the Soil Resource Development Institute71,72; (ii) agricultural relevance, particularly their active involvement in Boro season rice cultivation despite salinity challenges; and (iii) socioeconomic diversity, enabling comparative analysis of farmers’ perceptions and adaptation strategies under varying resource conditions. These upazilas also reflect the geographical gradient of salinity intensity across the southwest coastal region, making them ideal for assessing both field-level salinity effects and locally practiced adaptive responses. The locations for the field trials and the survey participants were chosen using a multistage sampling procedure. The details of the study sites, including geographic positions and the exact locations of 60 field trials, are illustrated in Fig. 5. Historical salinity data indicate that Bangladesh’s coastal areas have experienced a significant increase in salinity-affected cultivable land over the past few decades, peaking in 200971 and continue to increase each year. However, the intensity of salinity-affected areas varies considerably, particularly in the coastal districts of the country16. The selection criteria highlighted distinct characteristics of the coastal regions of Bangladesh, resulting in significant differences in the areas affected by salinity16, topography, and river systems72,73.

Data source and data collection method

Data were collected through household interviews using a structured questionnaire. Trained agricultural field assistants, recruited for the “Partnership Enhancement and Engaged in Research” (PEER) Project supported by National Academy of Science (NAS), USA, conducted face-to-face interviews. These field assistants received training from the research team at the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) prior to the field study. The interviewers were supervised by the research team, with the lead author also participating in some interviews. The questionnaire was developed by the research team and piloted before use in the field.

Households were randomly selected from two districts and four upazilas within coastal areas (Fig. 5), in consultation with the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) of Bangladesh. The questionnaire comprised 26 individual questions that included basic demographic information such as age, gender, household size, number of household members, household income, education level, and questions related to behaviors. To validate the suitability of the questionnaire, a pre-survey was conducted with 25 households to ensure appropriate responses to all the questions. Following this pre-survey, we made slight modifications to the questionnaire, finalizing it to include 26 key questions addressing the knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and adaptation strategies of local farmers concerning salinity issues in food crop production.

We then randomly interviewed 200 households across four salinity-prone coastal upazilas: Kaliganj, Debhata, Asashuni, and Koyra. Within each upazila, two representative villages were selected based on the degree of salinity exposure, rice cultivation intensity, and accessibility. From each village, 25 rice farmers were selected using purposive criteria, including their active involvement in Boro rice cultivation, long-term residence in the area, and firsthand experience with salinity-related challenges. This resulted in a total sample size of 200 farmers (4 upazilas × 2 villages × 25 farmers). One family member involved in rice production was interviewed from each household. Questions were asked sequentially, allowing sufficient time for respondents to think and provide appropriate answers. Since many respondents were illiterate or had only primary education, we occasionally needed to clarify questions to obtain accurate responses. Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents were free to decline to provide information at any time; however, none refused to be interviewed. Each respondent received a small gift (soap) worth USD 0.75$ as an incentive for their time. This gift was given after the interview, ensuring it did not influence their responses and served as a refreshment for the interviewed participants. The interviews were conducted prior to the start of the Boro rice growing season in Bangladesh, and we encountered no refusals or incomplete questionnaires.

Based on our previous experiences, we selected locations where salt concentrations were highest during the Boro season. Rice farms were chosen from a list of households that harvested rice during this season. The questions aimed to explore various aspects of farmers’ perceptions regarding salinity trends in their fields over the past 20 years. Few questions were also listed for further government policy formulation. Each rice farmer was asked a series of both closed and open-ended questions addressing: The challenges they faced during rice cultivation in the latter half of the season, The most significant difficulties encountered during Boro rice cultivation, their perceptions of the stages of rice crops most susceptible to salinity and their observations of plant responses during those stages, alternative strategies they employed to manage salinity issues in rice cultivation and what have they already got and further need from government?

Field trials for salinity adaptation strategy

Based on the survey, we compared farmers’ perceptions of salinity levels, the effects of salinity on rice crops, and adaptation strategies by comparing these perceptions with actual in-field salinity measurements. Each location included 15 fields, with five fields for each of three different transplanting dates, resulting in a total of 60 fields (5 fields × 3 transplanting dates × 4 locations). The transplanting dates were categorized as follows: early transplanting occurred when seedlings were transplanted in the main field before January 1; mid transplanting was defined as seedlings transplanted from January 1 to January 14; and late transplanting occurred when seedlings were transplanted after January 14. Salinity levels varied in rice fields depending on the transplanting dates16.

Experimental setup

Farmers prepared seedbeds and land following standard BRRI guidelines. Seedlings were 40–45 days old at transplanting. The varieties used included BRRI dhan28, BRRI dhan67, IT, Aftab-70, Babilon-2, Aftab-106, Sathi, and Hira, reflecting the local varietal diversity. All intercultural operations (weeding, irrigation, fertilizer application, urea top dressing) followed standard BRRI protocols to minimize management variation across fields15. Field assistants provided oversight and guidance throughout the season to ensure protocol compliance.

Salinity measurements

Salinity levels were measured using a portable electrical conductivity (EC) meter (Model H199301, Hanna Instruments, United Kingdom). Salinity level was measured at three fixed points in each plot, and EC values were averaged to represent the field salinity at each time point. Measurements were taken weekly from the time of transplanting until the ripening stage.

Yield measurement

At physiological maturity, grain yield was estimated using the standard crop-cut method. In each field, three 1 m² quadrats were randomly selected and harvested. Grain from these quadrats was threshed, cleaned, and weighed. Moisture content was measured and adjusted to a standard 14% moisture level, and yields were expressed in tons per hectare (t ha⁻¹).

Statistical analysis

All data were transcribed word-for-word from Bengali to English by the lead author, who is proficient in both languages. Responses to open-ended questions were categorized into common themes to ensure consistency in interpretation, minimizing potential variation that could arise with multiple coders. Each theme was assigned a numeric code for analysis in SPSS (Version 16). Nonparametric chi-square tests were applied to demographic variables to examine mean differences across study locations. These variables included age, education level, farm size, years of farming experience, monthly income, total rice area, and Boro season rice area. For continuous demographic variables, we used Kruskal-Wallis test to evaluate differences in medians across locations. Farmers’ perceptions regarding salinization (e.g., causes of salinity, rice stages most affected, impacts at these stages, and adaptation strategies) were analyzed using cross-tabulation to compare responses (frequencies by category) across study locations.

We tested the normality of farmers’ perceptions of field salinity measurement and management data using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Linear mixed model was used to analyze the effect of transplanting time on salinity levels during the vegetative stage and reproductive stages separately. For each stage, the model includes transplanting time as a fixed effect and location and field as random effects. In case of yield data, we tested the effect of three transplanting dates (early, mid, and late) on yield, with a linear mixed-effects model applied to log-transformed yield data.

The dataset consisted of 60 observations collected from four experimental locations. Within each location, there were five replicated fields, giving a total of 15 replication units. For each replication, yield was recorded under one of three transplanting dates (early, mid, late). This nested structure required us to account for location and replication effects when analyzing treatment differences.

Where, Yieldijk = observed yield under transplanting date i, at location j, and replication k within location j; μ = overall intercept (mean yield under the reference level of transplanting date); Ti = fixed effect of transplanting date (early, mid, late); Lj = random effect of location; Rk(j) = random effect of replication nested within location; eijk = residual error. This model included transplanting date as a fixed effect and location & field as random effects

The linear mixed model used was:

with transplanting date as a fixed effect and Location and Replication (nested within Location) as random effects. Normality test was shown in Figure S1. The model converged successfully using the REML criterion (-93). Scaled residuals ranged from −2.1764 to 1.9267, indicating a reasonable distribution of residuals.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Islam, M., Rahman, M. A., Hossain, M. A. & Akter, S. Impact of salinity on rice production in coastal regions of Bangladesh. J. Agric. Sci. 15, 101–110 (2023).

Dam, T. T. H. et al. The impact of salinity on paddy production and possible varietal portfolio transition: a Vietnamese case study. Paddy Water Environ. 17, 771–782 (2019).

Kamoshita, A., Wahid, A. N. M. & Vinh, V. Q. Vulnerability of rice production systems to salinity stress: a case study from Vietnam. Paddy Water Environ 18, 299–310 (2020).

Kavency, L., Nguyen, T. H. & Tran, M. D. Salinity intrusion and its impact on rice farming in the Mekong Delta. Vietnam. Agric. Water Manag. 275, 108004 (2023).

Hossain, M. S. et al. Recent changes in ecosystem services and human well-being in the Bangladesh coastal zone. Reg. Environ. Change 16, 429–443 (2016).

Rahman, M. M., Saha, N. & Hossain, M. S. Mapping and monitoring salinity intrusion in the coastal area of Bangladesh using MODIS time-series images. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 1–12 (2019).

Afroz, T., Cramb, R. & Grunbuhel, C. Addressing salinity-induced land degradation in coastal Bangladesh: farmers’ perspectives and responses. Land Use Policy 79, 398–407 (2018).

BCCSAP. Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan 2009 (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2009).

NAP. National Adaptation Plan (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of Bangladesh, 2018).

Berkhout, F. Adaptation to climate change by organizations. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 3, 91–106 (2012).

Islam, M. M., Sarker, M. H. & Hossain, M. M. Farmers’ perceptions on the causes and consequences of climate change in Bangladesh. Sustainability 10, 4574 (2018).

Khan, S. M., Rabiul, I. & Islam, M. Salinity-induced food insecurity in Bangladesh: challenges and solutions. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 55, 324–334 (2020).

Hossain, M. S. et al. Social-ecological resilience to climate change in coastal Bangladesh. Ecol. Soc. 23, 45 (2018).

Rahman, M. A., Sarker, M. A. R. & Rahman, M. M. Salinity effect on yield and yield attributes of rice in coastal area of Bangladesh. Progress. Agric. 30, 123–130 (2019).

BRRI. Modern Rice Cultivation, 24th edn, 112 (BRRI, 2022).

Islam, M. A. et al. The importance of farmers’ perceptions of salinity and adaptation strategies for ensuring food security: evidence from the coastal rice-growing areas of Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 727, 138674 (2020).

Hasanuzzaman, M., Hossain, M. A. & Fujita, M. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of nitric oxide-induced salinity tolerance in rice seedlings. Plant Soil 329, 217–231 (2009).

Munns, R. & Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681 (2008).

Adamo, S. B. Slow-onset hazards and population displacement in the context of climate change. in Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Assessing the Evidence (eds Laczko, F. & Aghazarm, C.) (IOM, 2011).

Greiner, R. & Parton, K. A. Salinity: a cost to agriculture. Aust. J. Agric. Econ. 39, 209–225 (1995).

Thomalla, F. et al. Reducing hazard vulnerability: toward a common approach between disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation. Disasters 30, 39–58 (2006).

Hall, J. W., Sayers, P. B. & Dawson, R. J. National-scale assessment of current and future flood risk in England and Wales. Nat. Hazards 32, 129–149 (2004).

Nguyen, H. T. et al. Evaluation of salt-tolerant rice genotypes under salinity conditions in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Agronomy 8, 147 (2018).

Abedin, M. A., Habiba, U. & Shaw, R. Community perception and adaptation to safe drinking water scarcity: salinity, arsenic and drought risks in coastal Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 5, 110–124 (2014).

Adger, W. N. et al. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change?. Clim. Change 93, 335–354 (2009).

Adger, W., Barnett, J., Brown, K. et al. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 112–117 (2013).

Alam, G. M. M., Alam, K. & Mushtaq, S. Determinants of climate change adaptation decisions and farmers’ resilience in Bangladesh. Clim. Risk Manag. 39, 100512 (2023).

Bryan, E. et al. Adapting agriculture to climate change in Kenya: household strategies and determinants. J. Environ. Manage. 90, 1107–1117 (2009).

Alam, G. M. M., Alam, K. & Mushtaq, S. Climate change perceptions and local adaptation strategies of hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Clim. Risk Manag. 17, 52–63 (2017).

Rahman, M. M., Sultana, M. S. & Hossain, M. M. Salinity adaptation strategies in coastal rice farming: insights from field-level assessments in Bangladesh. Agric. Syst. 207, 103624 (2023).

Mamun, A. A., Nasrin, S. & Dewan, C. Land use change due to shrimp aquaculture and its impact on food security in southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 7, 221–226 (2014).

Wachinger, G., Renn, O., Begg, C. & Kuhlicke, C. The risk perception paradox—implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk Anal. 33(6), 1049–1065 (2013).

Habiba, U., Abedin, A., Shaw, R. & Hassan, A. W. R. Salinity-induced livelihood stress in coastal region of Bangladesh. in Water Insecurity: A Social Dilemma, 139–165 (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2013)

Roy, B., Hassan, M.dA. bu, Khan, M.dA. l-A. min & Sheikh, S. hakil Environmental impact of shrimp farming: a case study of coastal community. J. Agrofor. Environ. 17(2), 234–247 (2024).

Lam, Y., Winch, P. J., Nizame, F. A. et al. Salinity and food security in southwest coastal Bangladesh: impacts on household food production and strategies for adaptation. Food Sec. 14, 229–248, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01177-5 (2022).

Khan, M. S. A., Alam, M. J. & Saroar, M. M. Land-use zoning for sustainable agriculture in the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh: a geospatial approach. Land Use Policy 95, 104603 (2020).

Islam, M. S. The coastal land-use zoning in Bangladesh: problems and prospects. in Coastal Environment and Resource Management: Bangladesh Perspective (eds Chowdhury, M. A. H. & Khan, M. R.) 45–60 (PDO-ICZMP/WARPO, 2006).

LandAC. Zoning for sustainable land use: lessons from Bangladesh (Policy Brief, Land Governance for Equitable and Sustainable Development, 2019).

Haque, S. A. Salinity problems and crop production in coastal regions of Bangladesh. Pak. J. Bot. 38, 1359–1365 (2006).

Islam, R., Nursey-Bray, M. & Rist, P. Social vulnerability and adaptation to climate change in riverine communities of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manage. 256, 109948 (2021).

Mahmud, K., Kabir, M. H. & Rahman, M. S. Challenges of rice cultivation in salinity-prone areas of Bangladesh: evidence from the coastal zone. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innov. Technol 13, 27–34 (2023).

Sattar, M. A., Ali, M. H. & Chowdhury, M. A. I. Freshwater scarcity and its implication on agriculture in coastal Bangladesh. Water Resour. Manage. 36, 487–504 (2022).

Abbas, G., Saqib, M., Akhtar, J. & Haq, M. A. Interactive effects of salinity and boron on growth, photosynthesis and mineral composition in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Nutr. 38, 1590–1606 (2015).

Khatun, M. T., Amin, M. R. & Haque, M. E. Effect of salinity stress on growth and yield attributes of rice genotypes. Int. J. Agron. Agric. Res. 17, 1–10 (2020).

Yin, X., Yang, H., Zhang, S. & Li, X. Salt stress impairs reproductive development and grain yield in rice: physiological and transcriptomic insights. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 204, 107354 (2024).

Grattan, S. R. et al. Rice is more sensitive to salinity than previously thought. Calif. Agric. 56, 189–195 (2002).

Islam, M. T. & Karim, Z. Salinity and drought stress tolerance in rice: progress and challenges. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 196, 270–281 (2010).

Clarke, D., Mainuddin, M. & Rahman, R. Salinity in the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. CSIRO Water for a Healthy Country Flagship (2015).

Islam, M. T. & Shelley, I. J. Salinity intrusion and its impacts on agriculture in coastal Bangladesh: local perception and adaptation. in Salinity Intrusion and Climate Change, 109–128 (Springer, 2016).

Hasan, M. M., Islam, M. T. & Shamsuddoha, M. Mapping salinity tolerance of rice at reproductive stages in southern Bangladesh using GIS. Agric. Water Manag 286, 108395 (2023).

Miah, M. G., Islam, A. K. M. R. & Rahman, M. A. Farmers’ perception and knowledge on salinity and salt-tolerant rice cultivation in southwest coastal Bangladesh. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Res. 6, 161–171 (2019).

Akter, M., Islam, M. R. & Mahmud, M. S. Farmers’ perception of salinity and its impact on crop production in the coastal region of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 13, 51–56 (2020).

Roy, T. K., Sultana, S. & Hossain, M. S. Farmers’ adaptation to salinity stress: evidence from the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 61, 103581 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Mechanisms of plant responses and adaptation to soil salinity. Innovation 2, 100017 (2021).

Miah, M. G., Rahman, M. A. & Islam, A. K. M. R. Salinity tolerance and management strategies for rice production in coastal areas of Bangladesh. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ 18, 723–732 (2020).

Ismail, A. M., Heuer, S., Thomson, M. J. & Wissuwa, M. Genetic and genomic approaches to develop rice germplasm for problem soils. Plant Mol. Biol. 65, 547–570 (2007).

Islam, M. S., Akter, M. & Rahman, M. M. Effect of salinity on yield and yield components of rice varieties at reproductive stage. Progress. Agric 29, 194–200 (2018).

Nasrin, M., Rahman, M. M. & Hossain, M. A. Effect of salinity stress on reproductive stage of BRRI Dhan67 rice. Bangladesh Rice J. 26, 29–35 (2022).

Islam, R. et al. Salinity hazard drives the alteration of occupation, land use and ecosystem service in the coastal areas: Evidence from the south-western coastal region of Bangladesh. Heliyon 9, e18512 (2023).

Can, N. D. Farmers’ adaptive strategies to salinity intrusion in the Mekong Delta. Vietnam. J. Environ. Plan. Manage. 59, 1939–1954 (2016).

Hossain, M. et al. Climate change and rice production in Bangladesh: a review. J. Clim. Change 4, 187–203 (2018).

Sarker, M. A. R., Haque, A. M. & Mahmud, M. S. Timing transplanting to reduce salinity stress in coastal rice: a case study in Bangladesh. Field Crops Res. 302, 109208 (2024).

Bhuyan, M. I. et al. Effect of soil and water salinity on dry-season boro rice production in the south-central coastal area of Bangladesh. Heliyon 9, e19180 (2023).

Debsharma, S. K. et al. Developing climate-resilient rice varieties (BRRI dhan97 and BRRI dhan99) suitable for salt-stress environments in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 20, e0317153 (2024).

NAPA. Revised National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) 2009 (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2009).

NSDS. National Sustainable Development Strategy (Planning Commission, Government of Bangladesh, 2013).

BINA. Annual Report 2018–2019 (Bangladesh Institute of Nuclear Agriculture, 2019).

GED. Perspective Plan of Bangladesh 2010–2021: Making Vision 2021 a Reality (Planning Commission, Govt. of Bangladesh, 2012).

Mamun AI, A., Nasrin, S. & Dewan, C. Land use change due to shrimp aquaculture and its impact on food security in southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 7, 221–226 (2014).

Barai, M. K., Islam, M. R. & Sarker, M. H. Impact of shrimp farming on land use changes and sustainability in coastal Bangladesh. Environ. Manage. 63, 664–676 (2019).

SRDI. Salinity in Bangladesh: Assessment and Changes Over Time (Soil Resource Development Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of Bangladesh, 2010).

BWDB. Coastal Embankment Improvement Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report (Ministry of Water Resources, Govt. of Bangladesh, 2013).

Hossain, M. Z. & Roy, M. K. Climate change and sea-level rise in Bangladesh: issues and implications. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 3, 57–65 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by USAID-sponsored Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) Program’s Cycle 6 project, entitled “Ecosystem services in a changing climate: assessing critical services in Bangladesh rice production landscapes”. PEER is implemented by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) via USAID and NAS Prime Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-11 -00012. D.A.L. also acknowledges support by the National Science Foundation Long-term Ecological Research Program (DEB 1832042 and DEB 2224712) at the Kellogg Biological Station and by Michigan State University AgBioResearch. The authors thank the field staff recruited through PEER funding for collecting data from experimental fields and the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) for providing other necessary support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.A. and D.A.L.; experiments, M.P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.A.; writing—review and editing, M.P.A. and D.A.L.; materials and equipment, M.P.A.; supervision, M.P.A. and D.A.L.; funding acquisition, M.P.A. and D.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, M., Landis, D.A. Adapting to salinity in coastal rice farming: integrating farmer perceptions with empirical field evidence. npj Clim. Action 4, 90 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00287-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00287-6