Abstract

X-ray photon-counting computed tomography (PCCT) has garnered considerable interest owing to its low-dose administration, high-quality imaging, and material decomposition characteristics. Current commercial PCCT systems employ compound semiconductor photon-counting X-ray detectors, which offer good energy resolution. However, the choice of materials is limited, and cadmium telluride or cadmium zinc telluride is mostly used. Although indirect radiation detectors can be used as alternatives to compound semiconductor detectors, implementing fine-pitch segmentation in such detectors is challenging. Here we designed an indirect fine-pitch X-ray photon-counting detector by combining miniaturized silicon photomultiplier arrays and fast scintillation crystals, with a pixel size of 250 µm, for future indirect PCCT. The fabricated array detector has the potential to discriminate photon energies with a 27% resolution at 122 keV, 296 µm spatial resolution, and charge-sharing inhibition ability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

X-ray photon-counting detectors (PCDs) are expected to be utilized in next-generation photon-counting computed tomography (PCCT) machines for medical applications1,2,3 as well as in various industrial applications, such as line scanners for detecting unwanted objects during contamination inspection4. Thus, PCDs should be compact, exhibit a high detection efficiency, and resolve X-ray energies to identify scattering or absorption events during scans. A good energy resolution, which is the prerequisite for realizing “material decomposition” in target objects, such as the human body and foods, reportedly facilitates low-dose CT scanning5,6,7. Current commercial PCCT devices provide a fine spatial resolution of ~200 µm, outperforming the conventional CT scanners8,9,10,11,12. A typical PCD is expected to exhibit good energy resolution to realize typically more than three threshold bins, fine spatial resolution of a few hundred micrometers, and high-count-rate handling capability. Accordingly, the feasibility of employing state-of-the-art compound-semiconductor-based detectors, such as cadmium telluride (CdTe), Gallium Arsenide (GaAs), and cadmium zinc telluride (CZT), in PCDs in various applications has been investigated owing to the good energy resolution (of the order of 1% at 662 keV) of these detectors13,14,15. Moreover, studies to improve their performance through various approaches are ongoing, such as suppression of charge sharing, which degrades the spatial resolution of such detectors13,16. These direct compound semiconductor PCDs have sophisticated performances17,18,19,20,21,22.

An indirect radiation detector, formed by combining a scintillation crystal with a photon sensor, is another commonly used radiation detection device. In these indirect detectors, incident X-rays are converted into scintillation photons (visible light wavelength), which are subsequently detected by a photon sensor. The energy resolution of an indirect detector is inferior to that of a direct-conversion semiconductor detector. Notably, owing to recent advances in photon sensing technology (such as improvements in silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs))23, which is based on arrays of numerous single-photon avalanche diodes (SPADs)24,25,26,27, indirect radiation detectors have recently come under the spotlight as viable PCDs28. However, studies on material identification using detection systems composed of scintillation crystals combined with SiPMs, featuring small pixel sizes (such as 1 mm), are scarce28,29. For instance, Koyama et al. reported 500-µm fine-pitch SiPM arrays for positron emission tomography scanners30. Maruhashi et al. developed a 16-channel multipixel photon counter array with 1 mm pixel size as an indirect-type PCD for multicolor three-dimensional PCCT imaging28. Notably, indirect-type PCDs with realistic pixel sizes of a few hundred micrometers and good energy resolution for PCCT have not yet been reported. In typical PCCT, 3–4 thresholds are used, which indicates that ~25–30% energy resolution is preferable for 100 keV of photon energy. It is still challenging and important to achieve small pixel-size PCD with indirect conversion method31.

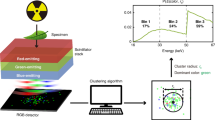

In this study, we designed and developed a functional fine-pitch energy-resolving PCD technology demonstrator composed of a scintillation crystal array and fine-pitch SiPM array, for future indirect PCCT. The microcell sizes in the SiPM array as well as interconnection between the scintillation crystal and SiPM arrays were optimized to obtain the best performance.

Results

Energy-resolution optimization using single crystals

We fabricated a custom 250-µm SPAD array (SiPM) and 250-µm pixel scintillation crystals as shown in Fig. 1a, b, respectively, and evaluated the performance of the combined setup. For single-crystal evaluation, we put one crystal (same as the one in the array) on one of the pixels in the SiPM array as shown in Fig. 1c. The crystals and SiPMs were coupled with an optical grease (TSK5353). Figure 2 shows the measured energy spectrum, and Table 1 summarizes the energy resolution (full width at half maximum (FWHM)) measured with the combined setup composed of gadolinium aluminum gallium garnet (GAGG)/gadolinium fine aluminum gallate (GFAG) crystals and a 15-µm/20-µm microcell SiPM. The combination of GAGG and 20-µm microcell shows the best-measured energy resolution of ~16% at 122 keV (GAGG + 20-µm) as shown in Fig. 2a, b. This excellent energy resolution can be attributed to the high gain of the 20-µm microcell SiPM and good intrinsic energy resolution of GAGG, which is superior to that of GFAG. Similar gain and intrinsic energy resolution differences are observed between GAGG (19.9% (GAGG + 15-µm) and 16% (GAGG + 20-µm), respectively at 122 keV) and GFAG (27.1% (GFAG + 15-µm) and 22.2% (GFAG + 20-µm), respectively at 122 keV) when combined with the 15-µm microcell SiPM. However, at low energies (~14 keV), the energy resolution of the 15-µm device is better than that of the 20-µm device. This result can be attributed to the number of microcells (196 and 96 in the 15- and 20-µm devices, respectively), which limits the statistics of photon measurement. Since the scintillation decay is longer than the SiPM response time, more photons than the number of microcells are involved in the pulse generation, affecting the energy resolution. The GFAG + 15-µm device shows moderate energy resolution from low to high energies and is optimal for our experiment. In some low-flux applications, GAGG can be the most useful candidate. By contrast, the time resolution of GFAG is superior to that of GAGG, as demonstrated later. Based on these results, the GFAG + 15-µm array device was used in our experiment.

a Fabricated 10 × 10 SiPM (silicon photomultiplier) array with a pitch of 250 µm. b Fabricated 10 × 10 GFAG (gadolinium fine aluminum gallate) array with a pitch of 250 µm and separated by a 50-µm-thick reflector layer and coupled device. c Single pixel and array coupling. The pixel size of the fabricated SiPM array is 250 µm, and the sensitive area is located on the left side of the chip. The right side of the chip contains the readout pads connected to the output of the SiPM pixels via wire bonding. In this study, 12-, 15-, and 20-µm microcell-type SiPM arrays were fabricated. The 200-µm GAGG (gadolinium aluminum gallium garnet)/GFAG pixels are separated by 50-µm-thick white urethane reflectors.

a Log-scale energy spectra obtained from four combinations (15 µm-GAGG, 15 µm-GFAG, 20 µm-GAGG, and 20 µm-GFAG). The 122 and 14 keV γ-rays originating from a 57Co radioisotope source as well as an escape peak (79 keV) are clearly visible. b Linear-scale energy spectrum of the 20 µm-GAGG combination. Three distinctly separated peaks are visible, indicating that the energy resolution is sufficient to set more than three thresholds in the PCD (photon counting detector). c Log-scale energy spectra of GAGG-single and GAGG-array devices. GAGG-array shows a slightly degraded energy resolution and shifted peak position, in addition to a new peak at 43 keV, which corresponds to escape X-rays of gadolinium.

Energy resolution of PCD array

The GAGG/20-µm microcell SiPM shows the best energy resolution in the experiment. Thus, the energy resolution of the single pixel in the GAGG/20-µm microcell SiPM-based PCD array is compared with that of its single-pixel counterpart, and the corresponding results are shown in Fig. 2c. At 122 keV, the measured energy resolution of the array is 18%, which slightly degrades from 16.2% for the single pixel. The position of the 122-keV peak also shifts by ~82%, indicating that ~18% of the photons are lost in the pixel array compared with those in the single pixel. This photon loss may be attributed to the thin reflector (50 µm thickness) made of white urethan resin. The reduced light collection also explains the slight degradation of the energy resolution.

In addition, the spectrum obtained from the pixel array shows a prominent peak at ~43 keV, which is not observed in the spectrum obtained from the single pixel. This peak can be ascribed to the gadolinium X-rays that escape from the neighboring pixel. Peaks due to optical crosstalk between channels are not observed at the expense of sensitivity loss, ~36% by reflector layer. The height of 14-keV peak in the spectrum obtained from the array pixel is higher than that of the peak observed in the single-pixel spectrum. This suggests that optical crosstalk peak may be included in this peak. However, the crosstalk estimated from the measured energy spectrum is less than ~10%. Therefore, the fabricated indirect detector does not show any crosstalk effect, such as charge sharing, which is encountered in direct detectors. Pixel crosstalk primarily originates from escaping X-rays, which should be calibrated during the reconstruction stage.

Energy-resolution distribution in the PCD array

We fabricated a 10 × 10 PCD array of 250-µm GFAG coupled to 15-µm microcell SiPMs and evaluated its performance. This array (GFAG/15-µm) provided fast time resolution and a moderate energy-resolution response in a wide range. The energy spectrum spanning 96 out of 100 channels, connected via wire bonding, was evaluated. Figure 3a shows the summed energy spectra of all the working channels normalized with respect to the 79-keV peak and their fitting result obtained by fitting a fourth-order Gaussian function to the spectra. The spectra are uniform, and distinct peaks are located at 122, 79, 43, and 14 keV in the summed spectrum. The calculated energy resolution values at 122, 79, and 14 keV are 27%, 27.5%, and 48.6%, respectively, which shows good uniformity and the possibility of setting 3–4 thresholds in energy discrimination applications.

a Summed energy spectrum by the 96-channel array detector (GFAG (gadolinium fine aluminum gallate)/15-µm). b Distribution of energy resolution (E.R.) at 79 and 122 keV, and peak position in the pixel array. a shows the summed spectrum normalized with respect to the peak at 79 keV and fitted with a fourth-order Gaussian function spanning 96 channels. b energy distribution at 79 keV (left) and at 122 keV(middle) and the peak position distribution(right) are shown as a color bar.

Timing performance of the SiPM

Timing performance is important in several aspects. Rise time is important for the application of TOF-CT; it was recently proposed to reject scattered events. The pulse duration is important in deciding the maximum count rate in the application. First, to examine the SiPM response, we observed the waveforms obtained from the SiPMs (12-, 15-, 20-µm devices) under pulsed laser irradiation (Hamamatsu 520 nm pico-second laser); the waveforms were captured on a 20 GHz Lecroy oscilloscope, and the rise and fall times were computed from the averaged data. Figure 4 shows that the 12-µm devices exhibit the smallest pulse width, which is crucial in photon counting applications. Further, among all the devices, the 20-µm and 15-µm devices exhibit the fastest rise time, which may be ascribed to the high gain and good uniformity of this SiPM device.

Timing performance of the PCD

Table 2 shows the measured time parameters (rise time, decay time, FWHM, and full width at tenth maximum (FWTM)) of the various combinations of GAGG/GFAG and microcell SiPMs (12, 15, and 20 µm devices). The measured scintillation decay times of GAGG (~90 ns) and GFAG (<40 ns) reveal that the timing response of GFAG is two to three times faster than that of GAGG in all the corresponding device combinations. However, the size of the microcell also affects the response time; that is, the timing response of the smallest microcell device (12 µm) is faster than that of the largest microcell device (20 µm) evaluated in this study. In this experiment, no experimental evaluation was performed for count rate capability. However, compared with the reference, the device (GFAG-15 µm) is expected to have more than 40 Mcps/mm2 at 30% pileup-loss condition32.

Evaluation of spatial resolution

Figure 5 shows the spatial resolution evaluation results with the Line pair (LP) profile in Fig. 5a, b and the slanted edge method in Fig. 5c. LP/mm s of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 mm were scanned. (a) shows the measured LP profile of the gauge (Moriyama TYP11) with different tube voltages (35, 40, 60, 80, and 100 kV) indicating a clear separation of 2.5 LP/mm. (b) shows the modulation transfer function (MTF) at 10% values for each tube voltage and the results indicate a spatial resolution of ~2.9 LP/mm for all conditions. (c) shows the spatial resolution with the slanted edge method with FWHM and MTF (10%). The measured FWHM-based resolution shows from 251 µm to 283 µm depending on the tube voltage. The estimated spatial resolution by MTF at 10% was from 296 µm to 334 µm.

a shows the measured LP profile of gauge (Moriyama TYP11) with different tube voltages (35, 40, 60, 80, and 100 kV) for 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 LP/mm2 from left to right; b shows the modulation transfer function (MTF) 10% plot for each tube voltage showing ~2.9 LP/mm. The values are summarized in Table 3. c shows the spatial resolution with the slanted edge method with FWHM (full-width-half-maximum) and MTF(10%). The summarized values are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

We designed and fabricated a fine-pitch (250 µm), energy-resolving indirect detector by combining a brand-new fine-pitch SiPM with a fine-pitch scintillation crystal array. The resulting detector shows reasonable energy-resolving performance; that is, the single and array pixels show approximately <20% and <30% resolutions, respectively, which are necessary for its application as a PCD in future PCCT systems. Because the crystals are separated by 50-µm-thick reflectors, ~36% photon loss is estimated from the size compared to the monolithic detector. However, the measurement results demonstrate the presence of only minor optical crosstalk between the pixels. This crosstalk inhibition characteristic is a major advantage of this indirect detector over compound-semiconductor-based PCDs, which exhibit extensive charge sharing between pixels, providing poor energy resolution.

Escape X-rays originating from the gadolinium atoms in the GAGG crystals are also observed; such escape X-ray peaks are commonly observed in the spectra generated by both direct and indirect PCDs. Thus, future studies should focus on suppressing these escape X-rays in reconstructing original energy spectra. The calculated attenuation length in the crystal using NIST-XCOM data is ~220 µm.

The method could be further improved. In this study, we adopted a GFAG scintillation detector because of its stability, non-hygroscopicity, moderate energy resolution, and fast decay. However, the performance of the system can be further improved using faster and better-performing scintillation detectors (e.g., LaBr3 and CeBr3) with decay times of less than 20 ns and better energy resolutions33,34,35,36. However, such detectors have packaging issues; that is, they require mitigation of hygroscopicity to be potential candidates for PCCT. Our group is currently investigating the feasibility of fabricating a faster GFAG scintillator with a decay time of less than 30 ns by cooping a high concentration of Mg. In the present study, we used 15 µm and 20 µm devices; however, in terms of saturation, a 12-µm device can be an interesting candidate when combined with high-light yield scintillators. Furthermore, improving the pico-second range response time of the SiPMs (SPAD array) is imperative in processing faster signals generated from scintillation photons. In addition, indirect scintillator–SPAD array-based PCDs can be used to realize X-ray-based TOF-CT37,38, in which the noise caused by scattered photons can be suppressed using the timing information of the PCDs. Indirect detectors with short response times are suitable for this modality.

In this study, signal readout was performed using a simple wire-bonding method and discrete circuit. In the future, a dedicated readout application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) with TSV connections can be developed to construct buttable detector modules for PCCT applications. More efforts and developments are necessary for the practical clinical CT application.

Methods

Fine-pitch SiPM

For practical PCCT applications, detectors with pixel sizes of a few hundred micrometers are necessary. The currently available commercial PCCT scanners are composed of CdTe compound semiconductor-based detectors with a pixel size of 250 µm. At Fondazione Bruno Kessler (FBK), Trento, Italy, we designed and fabricated a 10 × 10 array of mini-SiPM elements with a pitch of 250 µm39, as shown in Fig. 1a. The left half of the figure shows the photon-sensitive area of the SiPM, and the right half shows the readout pad connected to each SiPM pixel via wire bonding. The wire-bonding method was applied to obtain good performance test conditions. However, despite the good performance, such a solution has limited scalability. Therefore, future devices will be constructed using the advanced through-silica via (TSV) and three-dimensional integration techniques, which have been recently developed in FBK, Italy40.

Microcells of three different sizes (12, 15, and 20 µm) were fabricated to determine the best-performing pixelated scintillation crystal–SiPM microcell combination. The devices formed by combining one 250-µm pixel with 12-, 15-, and 20-µm microcells, contained 260, 176, and 96 microcells, respectively. Because the SiPM was fabricated using the FBK RGB-HD technology39, its sensitivity was similar to that of a previously reported one39.

The current-voltage responses of the detectors were evaluated to identify the breakdown voltages, and the microcell gains were estimated from the plot of the number of pulses counted at different applied voltages. Figure 6a shows the current-voltage characteristics of the fabricated SiPMs. The measured breakdown voltage was ~27.5 V. At an overvoltage of 5 V, the measured gains of the 20,-, 15-, and 12- µm microcell devices increased to approximately >106, 5 × 105, and 2 × 105, respectively as shown in Fig. 6b. These results indicate that the gains exhibited by the 15- and 20-µm devices were sufficiently high for the energy resolution measurements conducted in this study.

Fine-pitch scintillation crystal array

To achieve one-to-one coupling with the SiPM array, a fine-pitch scintillation crystal array with a pixel size of 250 µm was designed and fabricated. Ce:GAGG and Mg-co-doped GAGG (GFAG) crystals (C&A Corporation41,42,43,44) were selected as candidates owing to their high stability, non-hygroscopicity, and moderate energy resolutions. GAGG exhibits a high light yield of ~45,000–55,000 photons/MeV, a decay time of 90 ns, and an energy resolution of 8–9% at 662 keV. In contrast, GFAG exhibits a light yield of 25,000–35,000 photons/MeV, a decay time of less than 40 ns, and an ~15% energy resolution at 662 keV. Both GAGG and GFAG have a density of 6.63 g/cm3, and their effective atomic number is 52. Figure 1b shows the fabricated pixel array of scintillation crystals used to collect and guide the generated scintillation photons toward the SiPMs. In this figure, the yellow and white parts represent a 200-µm crystal and 50-µm-thick reflector (white urethane resin), respectively. This low-density reflector, which separated each crystal, was applied to suppress the generation of unnecessary escape peaks.

To fabricate the array, first, a 1-mm-thick scintillator plate was fabricated, and then, a multiwire saw was used to form grid-like 0.8-mm-deep cuts in the plate. The groove and pixel widths were 50 ± 7 and 200 ± 6 μm, respectively. Subsequently, a white reflective material was poured into the grid-like grooves and dried. The residual layer was ground, and the white reflective material was applied to the top surface as well. This dicing-based fabrication method enabled accurate alignment as shown in the figure. Notably, 700-µm-thick crystals were used in this study to achieve high X-ray detection efficiencies, such as more than 75% efficiency at 100 keV.

Interconnection and readout electronics

A flip-chip bonding machine was used to join the 250-µm 10 × 10 SiPM array to the 250-µm 10 × 10 GFAG array, and optical grease was filled in between the two arrays. The readout PADs located at the right side of the SiPM chip (see Fig. 1b) were connected to a custom readout board via wire bonding. In this step, 96 out of 100 channels could be connected to the custom board for testing, and thus, the subsequent analyses were performed using the 96 working channels. Notably, for the preliminary energy spectrum measurement, each channel was singularly connected to an FBK custom transimpedance preamplifier.

The energy resolutions of the devices were measured using 57Co (386 kBq) and 241Am (3.15 MBq) radioactive sources. The signal waveform was sampled using a high-speed oscilloscope (EXR104A Keysight) to integrate the waveform for charge measurements.

To examine spectral uniformity, the measured energy spectra were normalized with respect to the 79-keV escape peak, and summed peaks corresponding to all the channels were evaluated. The energy resolution of each peak was determined by fitting a fourth-order Gaussian function to each peak and recording the corresponding FWHM value.

Characterization of timing performance

A PCCT system is expected to be operated under high fluxes, such as 1000 Mcps/mm2. Thus, assessing the response time of the associated detector is crucial, in addition to its energy resolution. The response times of the detectors were determined from the convoluted response pulses of the SiPMs and scintillators. To analyze the response times of the devices formed by various combinations of the GAGG/GFAG crystals and 12, 15-, and 20-µm microcells, various parameters, viz. rise time, decay time, FWHM, and FWTM, were extracted from their measured average waveforms (Fig. 7). The waveforms were sampled at a sampling rate of 16 GSa/s and bandwidth of 1 GHz using an oscilloscope. The rise time is defined as the time required by the pulse to increase its amplitude from 10% to 90%, which is the maximum level. Decay time is defined as the time constant τ of pulse decay fitted by the function: \(f\left(t\right)=\exp (-\frac{t}{\tau })\). FWHM is the full width half maximum of the measured pulse, and FWTM is the full width at the tenth maximum of the measured pulse.

Rise time, decay time, FWHM(full-width-half-maximum), and FWTM (full-width-tenth-maximum) of the pulse are extracted and compared for different crystals (GAGG (gadolinium aluminum gallium garnet)/GFAG (gadolinium fine aluminium gallate))–SiPM (silicon photomulitiplier) microcell (12, 15, and 20 µm) combinations.

Evaluation of spatial resolution

To verify the position resolution performance of the fabricated detector, we determined the spatial resolution of the detectors using an X-ray chart (Moriyama Typ. 11) with LP profile and slanted edge methods. In LP profile evaluation, we moved the X-ray chart in 50-µm steps in front of the detector. An X-ray generator (Raytech TS-120) with tube voltage/current combinations of 35 kV/2 mA, 40 kV/2 mA, 60 kV/0.2 mA, 80 kV/0.1 mA, and 100 kV/ 0.05 mA was used. The measurement time of each step was 2 s. Parallel signal readout was conducted using 64-channel discrete shaping amplifiers, comparators, and digitized signals were counted by counters, which were implemented using field programmable gate arrays (FPGA). One single threshold of approximately less than 30 keV was used for the entire experiment. The discriminated signals were counted using an FPGA-based data acquisition system (PETnet)45. PETnet has the function to record its rising and falling edges with an accuracy of 125 ps. Figure 8 shows the whole structure of the signal processing circuit employed in this study. To determine the intensity of each pixel, we calculated the attenuation as \({\mu }_{i}=-{\mathrm{ln}}\frac{{I}_{m}}{{I}_{b}}\), where \({\mu }_{i}\) is the estimated attenuation coefficient of the object through which the X-rays propagate, \({I}_{m}\) is the intensity measured in the presence of the object, and \({I}_{b}\) is the intensity measured without the object.

One channel is composed of a preamplifier, shaping amplifier, and discriminator with DAC (digital-to-analog converter) -based threshold control using an FPGA (field programmable gate array) as shown in (a). The converted digital signal is fed to the FPGA based ToT (time over threshold) data acquisition system named as PETnet (positron emission tomography net) to count the number of pulses and record them. b shows the parameters of the preamplifier and shaping amplifier used in the experiment.

The spatial resolution for each tube voltage was estimated based on the sharp edge profile. The MTF profile was generated by taking the Fourier transform of the line spread function (LSF). The spatial resolution was also examined by measuring the intensity gradient using the slanted edge method. The edge spread function (ESF) was estimated from the edge profile and fitted with the Gaussian error function. The spatial resolution was derived from FWHM divided by √2 of estimated LSF which is the first derivative of ESF46,47. The MTF was calculated by applying the Fourier transform to LSF and the spatial resolution was alternatively estimated by taking the inverse of spatial frequency at 10% of maximum MTF48,49.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that support the analysis of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Flohr, T. et al. Photon-counting CT review. Phys. Med. 79, 126–136 (2020).

Jalal, S. & Savvas, N. Advanced imaging technology: photon counting CT. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 75, 20–21 (2024).

Rau, A. et al. Photon-counting computed tomography (PCCT) of the spine: impact on diagnostic confidence and radiation dose. Eur. Radiol. 33, 5578–5586 (2023).

Haff, R. P. & Natsuko, T. X-ray detection of defects and contaminants in the food industry. Sens. Instrum. Food Quality Saf. 2, 262–276 (2008).

Alessio, A. M. & MacDonald, L. R. Quantitative material characterization from multi‐energy photon counting CT. Med. Phys. 40, 031108 (2013).

Shikhaliev, P. M. Photon counting spectral CT: improved material decomposition with K-edge-filtered X-rays. Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 1595 (2012).

Schirra, C. O. et al. Statistical reconstruction of material decomposed data in spectral CT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 32, 1249–1257 (2013).

Nadkarni, R. et al. Material decomposition from photon-counting CT using a convolutional neural network and energy-integrating CT training labels. Phys. Med. Biol. 67, 155003 (2022).

Grunz, J.-P. et al. Image quality assessment for clinical cadmium telluride-based photon-counting computed tomography detector in cadaveric wrist imaging. Investig. Radiol. 56, 785–790 (2021).

Symons, R. et al. Photon‐counting CT for simultaneous imaging of multiple contrast agents in the abdomen: an in vivo study. Med. Phys. 44, 5120–5127 (2017).

Rajendran, K. et al. First clinical photon-counting detector CT system: technical evaluation. Radiology 303, 130–138 (2022).

Douek, P. C. et al. Clinical applications of photon-counting CT: a review of pioneer studies and a glimpse into the future. Radiology 309, e222432 (2023).

Xu, C., Danielsson, M. & Bornefalk, H. Evaluation of energy loss and charge sharing in cadmium telluride detectors for photon-counting computed tomography. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 58, 614–625 (2011).

Takahashi, T. et al. High-resolution CdTe detector and applications to imaging devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 48, 287–291 (2001).

Szeles, C. CdZnTe and CdTe materials for X‐ray and gamma ray radiation detector applications. Phys. Status Solidi 241, 783–790 (2004).

Ullberg, C. et al. Measurements of a dual-energy fast photon counting CdTe detector with integrated charge sharing correction. In Medical Imaging 2013: Physics of Medical Imaging. 169–176 (SPIE, 2013).

Veale, M. C. et al. Measurements of charge sharing in small pixel CdTe detectors. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 767, 218–226 (2014).

Trojanova, E. et al. Evaluation of Timepix3 based CdTe photon counting detector for fully spectroscopic small animal SPECT imaging. JINST 13, C01001 (2018).

Dudak, J. High-resolution X-ray imaging applications of hybrid-pixel photon counting detectors Timepix. Radiat. Meas. 137, 106409 (2020).

Procz, S. et al. Investigation of CdTe, GaAs, Se and Si as sensor materials for mammography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 39, 3766–3778 (2020).

Clements, N., Richtsmeier, D., Hart, A. & Bazalova-Carter, M. Multi-contrast CT imaging using a high energy resolution CdTe detector and a CZT photon-counting detector. JINST 17, P01004 (2022).

Nguyen, J., Rodesch, P. A., Richtsmeier, D., Iniewski, K. & Bazalova-Carter, M. Optimization of a CZT photon counting detector for contaminant detection. JINST 16, P11015 (2021).

Acerbi, F. et al. Silicon photomultipliers: technology optimizations for ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared range. Instruments 3, 15 (2019).

Buzhan, P. et al. Silicon photomultiplier and its possible applications. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 504, 48–52 (2003).

Bronzi, D. et al. SPAD figures of merit for photon-counting, photon-timing, and imaging applications: a review. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 3–12 (2015).

Gundacker, S. & Heering, A. The silicon photomultiplier: fundamentals and applications of a modern solid-state photon detector. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 17TR01 (2020).

Acerbi, F. & Gundacker, S. Understanding and simulating SiPMs. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 926, 16–35 (2019).

Maruhashi, T. et al. Evaluation of a novel photon-counting CT system using a 16-channel MPPC array for multicolor 3-D imaging. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 936, 5–9 (2019).

Kiji, H. et al. 64-channel photon-counting computed tomography using a new MPPC-CT system. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 984, 164610 (2020).

Koyama, A. et al. Fabrication and characterization of a 500-μm-pitch 64-channel silicon photomultiplier prototype.”. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 912, 368–371 (2018).

van der Sar, S. J., Brunner, S. E. & Schaart, D. R. Silicon photomultiplier‐based scintillation detectors for photon‐counting CT: A feasibility study. Med. Phys. 48, 6324–6338 (2021).

Tuccori, N. & Peeters, S. J. Photon-counting computed tomography and scintillator-based detectors: a simulation analysis with scintillating and reflecting materials currently on the market. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 70, 1404–1412 (2023).

Higgins, W. M. et al. Crystal growth of large diameter LaBr3:Ce and CeBr3. J. Cryst. Growth 310, 2085–2089 (2008).

Quarati, F. et al. X-ray and gamma-ray response of a 2 ″× 2 ″LaBr3:Ce scintillation detector. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 574, 115–120 (2007).

Kaburagi, M. et al. Gamma-ray spectroscopy with a CeBr3 scintillator under intense γ-ray fields for nuclear decommissioning. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 988, 164900 (2021).

Otaka, Y. et al. Performance evaluation of liquinert-processed CeBr3 crystals coupled with a multipixel photon counter. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 67, 988–993 (2020).

Rossignol, J. et al. Time-of-flight computed tomography-proof of principle. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 085013 (2020).

Rossignol, J. et al. Time-of-flight scatter rejection in x-ray radiography. Phys. Med. Biol. 69, 055027 (2024).

Acerbi, F. et al. High-density silicon photomultipliers: performance and linearity evaluation for high efficiency and dynamic-range applications. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 54, 1–7 (2018).

Parellada-Monreal, L. et al. 3D integration technologies for custom SiPM: from BSI to TSV interconnections. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 1049, 168042 (2023).

Yoshino, M. et al. Development and performance evaluation of time-over-threshold based digital PET (TODPET2) scanner using SiPM/Ce: GAGG-arrays for non-invasive measurement of blood RI concentrations. J. Instrum. 12, C02028 (2017).

Kamada, K. et al. Cz grown 2-in. size Ce:Gd3(Al,Ga)5O12 single crystal; relationship between Al, Ga site occupancy and scintillation properties. Opt. Mater. 36, 1942–1945 (2014).

Iwanowska-Hanke, J. et al. Cerium-doped gadolinium fine aluminum gallate in scintillation spectrometry. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 979, 164464 (2020).

Shimazoe, K. et al. Development of simultaneous PET and Compton imaging using GAGG-SiPM based pixel detectors. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 954, 161499 (2020).

Sato, S., Uenomachi, M. & Shimazoe, K. Development of multichannel high time resolution data acquisition system for TOT-ASIC. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 68, 1801–1806 (2021).

Roque, R. C., et al. Spatial resolution properties of krypton-based mixtures using a 100 thick gas electron multiplier. J. Instrum. 13, P10010 (2018).

Zhang, S., Wang, F., Wu, X., Gao, K. MTF measurement by slanted-edge method based on improved zernike moments. Sensors 23, 509 (2023).

Hamdan, M. et al. The fabrication and characterization of direct conversion flat panel X-ray imager with TlBr film. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1064, 169372 (2024).

Scharenberg, L. et al. X-ray imaging with gaseous detectors using the VMM3a and the SRS. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A, 1011, 165576 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is partly supported by the JSPS KAKENHI 19H00672.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The concept was conceived by K.S. and K.K. The devices are prepared by F.A, A.G, K.K and Y.S. The experiments were conducted and analyzed by D.K., M.H., K.S., and K.S. K.S. prepared the manuscript. All the authors contributed in result discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Andrea Fabbri and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Anastasiia Vasylchenkova. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimazoe, K., Kim, D., Hamdan, M. et al. An energy-resolving photon-counting X-ray detector for computed tomography combining silicon-photomultiplier arrays and scintillation crystals. Commun Eng 3, 167 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-024-00313-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-024-00313-1

This article is cited by

-

Bulk single crystal growth and scintillation properties of Ce and Mg co-doped Y3Ga3Al2O12 for advanced X-ray imaging

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Metal halide perovskites: a platform for next-generation multifunctional devices

Advances in Industrial and Engineering Chemistry (2025)