Abstract

Sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting (SAWH) offers a promising solution to global water scarcity. However, practical implementation is limited by discontinuities in the mass transfer process inside sorbents. This perspective reviews current SAWH technologies and introduces a new concept, mass transfer of SAWH (MT-SAWH), which ensures continuous water collection by facilitating the movement of water molecules within a fixed sorbent bed. We discuss design principles and the potential for using renewable energy to maintain a stable water supply. Our goal is to highlight the future potential of SAWH and encourage the development of efficient water harvesting systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water resources have become a critical issue that threatens human health, security, and development due to rapid global population growth and economic development1. However, global freshwater supplies are scarce and unevenly distributed, with two-thirds of the global population (4.0 billion people) living under conditions of severe water scarcity at least 1 month of the year2. To alleviate the water crisis, it is necessary not only to protect current sources of drinking water and to improve water efficiency and public awareness of water conservation but also to explore new sources of water. The atmosphere is a potentially vast water resource, containing approximately 12,900 trillion liters of water in the form of water vapor and droplets3. This amount represents about 0.04% of global fresh water and is six times the total volume of rivers on the earth4. Because the atmosphere is fluid and interconnected, atmospheric water can be used and consumed anywhere, regardless of geographic, topographic, and hydrologic conditions5. Atmospheric water is a clean water resource, containing minimal levels of harmful chemicals and microorganisms. It can be used as drinking water or industrial water after simple and direct purification6. In addition, atmospheric water is a renewable resource that can be constantly replenished by surface water and ocean evaporation7. Therefore, atmospheric water harvesting offers an attractive solution to global freshwater scarcity.

Atmospheric water harvesting (AWH) involves capturing water droplets and extracting water molecules from the air8. Fog collection9,10 and vapor condensation11 are ancient, yet useful AWH techniques without consuming energy. Sorption-based AWH (SAWH) is an emerging technology that uses direct solar radiation as a heat source to drive water production12. These solar-powered SAWH systems provide a sustainable solution for all-day freshwater harvesting to address the global challenge of water scarcity13. Currently, SAWH systems can be categorized into two modes, discontinuous and continuous. The discontinuous SAWH system produces water intermittently. It typically adsorbs moisture at night and uses solar energy or other heat sources for desorption during the day14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. This mode alternates between sorption and desorption processes, resulting in a low water production efficiency. In contrast, the continuous SAWH system is able to synchronize the sorption and desorption process22,23,24,25,26, thereby enabling practical applications for all-day water harvesting and improving water production efficiency.

The SAWH system employs sorbent materials to extract water molecules from the atmosphere, demonstrating advantages such as portability and low energy consumption, thus providing a feasible alternative for water production that does not rely on conventional water sources. To date, great effort has been focused on the development and improvement of sorbent materials and SAWH systems27,28,29,30. The former concerns the capacity of sorbent to adsorb and desorb water molecules in the air, which involves the mass transfer process at the sorbent and air interface. The latter is concerned with the temporal synchronization of the sorption and desorption processes in the SAWH system. Unfortunately, the research on the mass transfer inside the sorbent and the continuity of the mass transfer process of the whole system has been neglected. It is evidently detrimental to the integrity and continuity of the mass transfer process in the SAWH system. It also constrains the optimization and improvement of the SAWH system, ultimately affecting its practical applicability in practical scenarios. Therefore, it is imperative to enhance the investigation of the mass transfer inside the sorbent, which is beneficial for interpreting and optimizing the overall mass transfer process of the SAWH system. This will provide new insights and perspectives for the development of high-performance SAWH systems.

Herein, we analyze the available SAWH processes from a mass transfer point of view. We summarize the distribution of water production efficiency for different SAWH systems and highlight the mass transfer process, including water molecule sorption/desorption and migration inside the sorbent. We discuss the origin of the discontinuity and discover that an integrated and continuous mass transfer process can be achieved by utilizing the directional migration of water molecules inside the sorbent. Based on this process, we propose a novel SAWH system that resembles an atmospheric water plant. This system has the potential to consistently and continuously produce fresh water from the air, making it suitable for decentralized drinking water supply in islands and remote areas, and enhancing the resilience of urban water supply systems to ensure a reliable source of potable water during unforeseen emergencies.

Current available SAWH systems

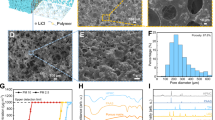

The urgent need for freshwater resources has driven considerable advancements in SAWH technology, leading to the development of various SAWH devices. As illustrated in Fig. 1, these devices can be categorized into discontinuous and continuous modes. Key parameters such as the number of sorbent beds, daily cycle frequency, and active and passive operation modes play crucial roles in optimizing water production efficiency by SAWH. The ongoing evolution of these devices has not only enhanced reliability and cost-effectiveness but also holds the potential to revolutionize water production methods, offering sustainable solutions to meet the increasing global demand for freshwater resources.

a Experimental setup of the solar glass desiccant-based system16. Copyright 2015, Elsevier. b Schematic of the water harvester consisting of a water sorption unit and a case21. Copyright 2018, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. c Working principle of the water harvesting device19. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. d Atmospheric water harvesting prototype, from top to bottom: aluminum plate, sorbent, upper chamber–metal funnel with a hydrophobic coating, and lower chamber-cooling water outlet20. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. e Operation principle of this rapid-cycling continuous water harvester24. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. f Working principles of the active and continuous SAWH system26. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. g Schematic of a cross-sectional view of the sorption-based continuous AWG prototype22. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. h Design of the autonomous airborne water supplier32. Copyright 2020, The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Discontinuous SAWH systems

Discontinuous SAWH devices typically utilize a single sorbent bed and alternate between sorption and desorption modes. As shown in Fig. 1a, the discontinuous SAWH device consists of a sorbent bed enclosed within a box with a glass lid serving as a condenser16. The box is opened at night to allow the sorbent bed to absorb moisture from the surrounding air, while it is closed during the day to utilize solar radiation-generated heat to elevate the temperature of the sorbent bed, leading to the release of water vapor that condenses on the glass cover. In contrast, the SAWH device in Fig. 1b incorporates a heat exchange mechanism between the side walls and the external environment to facilitate water vapor condensation21. Such passive systems have no secondary energy input to drive moisture migration or phase change. All components are assembled to realize the sorption or desorption-migration-condensation of water vapor spontaneously. Unlike these designs, the SAWH devices in Fig. 1c, d position the sorbent bed on top of the box and external cooling sources at the bottom, enabling the condensation of water vapor into liquid water at the bottom of the device19,20. These structural optimizations enhance the efficiency of condensation in the SAWH system.

The initial SAWH design was a discontinuous portable water extraction device capable of extracting water from low relative humidity (RH) locations. However, these discontinuous SAWH devices have relatively low water production capacity and utilize solar energy as a driving force for the desorption process, exhibiting instability in the water production process, thereby it is difficult to utilize them to address severe regional water scarcity. Therefore, developing active, continuous, efficient, and stable SAWH systems is crucial for overcoming the limitations of the discontinuous SAWH design and improving sustainable water management. Continuous SAWH systems would ensure a consistent and uninterrupted water extraction process, enabling a more reliable and efficient water supply. Continuous SAWH systems would also maximize water production while minimizing energy consumption, making them more cost-effective and environmentally friendly. By developing advanced SAWH systems, we can pave the way for a more sustainable and resilient water future.

Continuous SAWH systems

Currently, several SAWH devices have been developed to enable continuous water production, primarily by increasing the number of sorbent beds or utilizing moving sorbent beds. The SAWH device designed based on the former strategy incorporates multiple sorbent beds (Fig. 1e, f). During operation, one sorbent bed releases water vapor while the other sorbent bed is responsible for water molecule collection. The number of sorbent beds can be adjusted in the continuous SAWH systems. Figure 1f demonstrates a continuous SAWH device configured with dual sorbent beds26. In this setup, sorbent bed 1 captures water while sorbent bed 2 releases water vapor, and conversely, sorbent bed 2 captures water while sorbent bed 1 releases water. The two sorbent beds alternate to form a continuous cycle. When the SAWH device is configured with four sorbent beds, one bed is responsible for water release, while the remaining three beds are exposed to ambient air for water vapor capture (Fig. 1e)24.

An alternative approach to achieve a continuous SAWH process involves using a moving sorbent bed. This method allows the sorbent bed to move linearly/rotationally to switch between sorption and desorption modes and achieve a continuous water production process. As shown in Fig. 1g, a continuous SAWH process can be achieved through a cylindrical bed that fixed between two corrugated frames22. During operation, the top of the bed is exposed to sunlight to release water vapor in the condensation chamber, while the bottom is exposed to the environment to capture water molecules from the atmosphere. The use of a rotating sorbent bed enables a smooth transition between sorption and desorption modes, facilitating continuous water production. Wang et al. 31 suggested that the implementation of such a moving sorbent bed-based continuous SAWH system should involve a multi-stage approach with enhanced thermal and mass barriers at each stage.

However, the above-mentioned continuous SAWH systems require the cyclic alternation or movement of sorbent beds in order to achieve continuous water production. Consequently, the auxiliary devices and external energy sources are necessary to facilitate the movement of the sorbent bed, as well as to enable cyclic alternation between the sorption and desorption modes. It is evident that these requirements augment the complexity and energy consumption of the system. Furthermore, the function of sorbent beds in these continuous SAWH systems is limited to capturing water molecules from the atmosphere and subsequently releasing water vapor when relocated. However, the mass transfer process inside the sorbent has not received adequate attention or been fully explored for its potential applications.

Very recently, a unique continuous SAWH process32 that relies on mass transfer inside the sorbent has attracted our attention (Fig. 1h). This innovative technique utilizes specialized sorbent materials capable of capturing atmospheric water and spontaneously releasing liquid water. Unlike other continuous SAWH systems, this process enables a continuous sorption-desorption process through the direct release of weakly bound water clusters, eliminating the requirement for moving sorbent beds or switching between sorption and desorption modes. However, the removal of detained water inside the sorbent is another challenge in practical application.

We also plotted the water production efficiency distribution for different SAWH systems. As shown in Fig. 2, where the dots represent the water yield corresponding to a specific humidity and the horizontal stripes represent the water yield in that humidity range. Of the SAWH systems mentioned above, the water production efficiency of discontinuous SAWH systems ranges from 0.18 to 0.92 L kg−1 d−1, with the RH ranging from 20% to 88%16,17,18,19,20. For continuous SAWH systems, the water harvesting efficiency ranges from 0.6 to 2.12 L kg−1 d−1, corresponding to an RH range of 20–90%22,23,24,25,26. Notably, at 90% RH, the water production efficiency of autonomous SAWH reaches an impressive 6 L kg−1 d−1, surpassing the efficiency of other SAWH processes32. This finding highlights the potential of investigating and optimizing mass transfer inside the sorbent as a promising avenue for advancing continuous SAWH technology.

Additionally, our perspective introduces the concept of “mass transfer of sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting (MT-SAWH)”, which utilizes mass transfer inside the sorbent for simultaneous water sorption and desorption within a fixed sorbent bed. This approach is fundamentally different from the mass transfer process described by autonomous SAWH, and the MT-SAWH system would be more stable and sustainable, further improving the efficiency of water production.

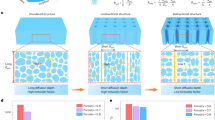

Mass transfer in SAWH

A conventional SAWH process involves sorption and desorption within the sorbent material, followed by condensation within the water collector (Fig. 3a)28. During the sorption stage, water molecules in the atmosphere are captured and accumulate as liquid water inside the sorbent. Next, the sorbent is heated, leading the liquid water to evaporate as water vapor. Finally, the resulting water vapor is converted back into liquid water, which is then accumulated in a water collector. Upon analyzing the movement of water molecules, it is observed that water molecules are merely captured and then released from the sorbent. For a single sorbent in the traditional SAWH systems, sorption and desorption are performed alternately. The effect of mass transfer processes inside the sorbent is neglected. We believe this is the origin of the discontinuity in the SAWH process. Clearly, a discontinuous mass transfer process diminishes the water production efficiency and stability of the SAWH system.

By contrast, an alternative SAWH based on the continuous mass transfer process inside the sorbent, denoted as MT-SAWH, is depicted in Fig. 3b. To ensure continuous water production, the MT-SAWH system needs constantly involves the sorbent sorption and desorption modes. In the MT-SAWH system, different processes can occur simultaneously inside the sorbent: sorption, vapor transport, liquid transport, heat transport, and desorption33. Water vapor is taken up by the side of the sorbent in contact with the ambient, and water molecules stick to a surface via physical (physisorption) or chemical (chemisorption) bonds involving gas-to-liquid phase transitions. Figure 3b describes the mass transfer process of water molecules, where liquid transport inside the sorbent from regions of high liquid concentration to regions of low concentration (Fig. 3b, blue dotted arrow). During desorption, interfacial heat supplied to the sorbent surface causes the release of vapor.

To realize continuous water harvesting, internal water transport is a key point, some advanced materials have been reported, including bioinspired topological design with unidirectional water transfer for efficient atmospheric water harvesting34. Moreover, gradient-structured hydrogels have been researched for direction-limited water transport35, which will have an important impact on the design of the MT-SAWH system and the field of mass transfer.

Different from other SAWH systems, the sorbent is fixed in the MT-SAWH system. Water molecules are adsorbed and desorbed separately on either side of the sorbent, and transported inside the sorbent. This internal mass transfer process effectively connects the sorption and desorption processes on both sides, enabling synchronous water sorption and desorption for continuous water production. By leveraging the mass transfer function of the sorbent, water molecules captured on the surface of the sorbent are transported to the other side and released immediately, thus eliminating the limitation of water production due to sorbent saturation. Furthermore, this continuous directional mass transfer process allows simultaneous sorption and desorption of water molecules on both sides of the fixed sorbent bed, improving sorbent utilization, simplifying system design, enhancing system reliability, and reducing maintenance difficulties.

SAWH is based on a continuous mass-transfer process

A continuous mass transfer process requires a match of water sorption rate, water desorption rate, and internal water migration rate. This process involves complex mechanisms. In this perspective, we introduce an ideal mass transfer model that assumes that the sorbent undergoes a sorption–diffusion–desorption process along the axial direction.

Without external forces, the transport of water molecules is realized by spontaneous migration along the humidity gradient, which is essentially driven by the difference in chemical potential36,37. The kinetics of sorption and desorption are predominantly influenced by the interactions between the sorbent and water molecules, as well as by temperature, humidity, and other pertinent factors. To achieve the necessary temperature gradients for the sorption and desorption phases, we propose to utilize external energy supplies. Specifically, a cooling system is employed to lower the temperature on one side of the sorbent, facilitating the sorption of water molecules. Conversely, a heating system is used to increase the temperature on the opposite side, promoting the desorption process.

Concurrently, the process of internal water transport is intimately linked to the structure and properties of the sorbent38. The structural characteristics of the sorbent, such as pore size, porosity, and surface properties, have a great impact on the transfer of water molecules inside the sorbent. A well-designed sorbent structure can enhance the diffusion coefficient of water molecules, leading to improved efficiency and stability of mass transfer. Moreover, the equilibrium concentration of water molecules adsorbed/desorbed on the sorbent surface is influenced by humidity and temperature. Adjusting the air flow rate and temperature can regulate the sorption/desorption rate of water molecules on the sorbent surface, enabling the achievement of a continuous SAWH process that aligns with the desired mass transfer rate.

Description of a proposed MT-SAWH system

As shown in Fig. 4, the conceptual graph of the MT-SAWH system is depicted as consisting of sorption, mass transfer layer, desorption, and condensation components. The mass transfer layer comprises a sorbent that involves water sorption and desorption processes. Atmospheric water molecules are captured and accumulated on one side of the sorbent, then transferred inside the sorbent (Fig. 4, blue dotted arrow), and released on the surface of the opposite side. Auxiliary devices such as fans can be used to enhance the sorption of water molecules to the sorbent’s surface, ensuring a sufficient supply of water molecules under low humidity conditions. On the opposite side, an auxiliary heat source or solar radiation provides the necessary heat energy for releasing water vapor from the sorbent surface. The resulting water vapor is then liquefied in the condenser and collected in a container. The energy required for the MT-SAWH system is supplied by a solar module, which consists of solar panels and energy storage batteries. This module effectively overcomes the intermittent and fluctuating nature of solar irradiation, thereby improving the overall efficiency of the MT-SAWH system. A solar-powered MT-SAWH system can achieve 24-hour continuous operation and adapt to different environmental conditions.

A complete MT-SAWH process can be described as follows: (1) air is fed into the system using auxiliary equipment such as a fan; (2) water molecules are captured and concentrated on the surface of the sorbent; (3) water molecules move inside the mass transfer layer toward the desorption side, propelled by the concentration gradient of the water molecules; (4) water molecules on the surface of the sorbent are released as water vapor by adjusting the temperature at the desorption side; (5) the resulting water vapor is condensed by the condenser and collected in the container. The MT-SAWH system operates continuously and steadily, optimizing the fan speed and the temperature of the desorption heat source to achieve a balance of sorption, mass transfer, and desorption, thereby enabling continuous and consistent water production.

Prospects of the MT-SAWH system

Due to the continuous and stable mass transfer process, the MT-SAWH system can be considered as a kind of atmospheric water plant, which is expected to serve as a new water production process that extracts water from the air as the primary source. This innovative approach not only demonstrates the capability to harness atmospheric water but also signifies a paradigm transition toward sustainable and resource-rich water management. By utilizing air as the feedstock, the MT-SAWH system demonstrates ingenuity in tackling water scarcity challenges. This concept positions the system as a pivotal player in water harvesting and represents a stride towards more environmentally friendly and efficient water production solutions.

As an expected innovation for water generation, MT-SAWH is anticipated to provide a solution for fresh water production in various geographical and climatic settings, enable efficient use and equitable distribution of water resources, and effectively address the global water crisis. For example, in remote regions where conventional water sources are not readily available, the MT-SAWH system can utilize atmospheric moisture to provide dependable water supplies and fulfill the drinking water requirements of the population. Moreover, following natural disasters such as earthquakes or floods, when conventional urban water supply systems may be compromised, the MT-SAWH system can function as a rapid-response alternative water source to bolster a city’s resilience in the face of disasters.

On the other side, a continuous and stable MT-SAWH system is expected to reduce reliance on conventional water sources. In arid and semi-arid regions, conventional surface reservoirs suffer substantial water evaporation losses, resulting in the squandering of valuable water resources. However, employing the MT-SAWH system to capture evaporated water from reservoirs can enhance and optimize the local water cycle, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of utilizing and distributing regional water resources. Furthermore, MT-SAWH can help prevent excessive exploitation of groundwater resources, safeguard groundwater levels, and maintain ecological balance. Therefore, the MT-SAWH system delivers multiple environmental and social benefits, presenting innovative and effective approaches to global water resource management and protection.

Challenges and outlook

The key challenge for MT-SAWH includes improving water production efficiency and expanding the RH range. These challenges can be tackled through sorbent material design and system optimization. The first involves enhancing sorption in low RH air, optimizing water desorption, and improving water diffusion inside the sorbent. The second focuses on expanding the sorbent’s effective area, optimizing energy usage, and implementing control strategies for mass transfer. Additionally, challenges such as maintenance, consumable replacement, and coping with unpredictable climates should be considered for on-site water production. By focusing on these areas, the MT-SAWH system can be improved to achieve higher water production efficiency, operate over a wider range of relative humidity, and overcome challenges associated with on-site water production. This will contribute to more sustainable and reliable water resource management.

-

(1)

Sorbent material design. To enhance the sorption of water molecules in low RH air, it is crucial to develop sorbent materials with a high surface area and tailored surface chemistry. This can be achieved by exploring advanced manufacturing techniques, such as nanostructuring or surface modification, to increase the sorption capacity and efficiency of the materials. Additionally, optimizing water desorption is essential for efficient water release from the sorbent. This can be accomplished by investigating novel desorption techniques, such as thermal, solar, or mechanical methods, to improve the desorption kinetics and overall water release. Furthermore, improving water diffusion inside the sorbent is critical for efficient water transport. Designing porous structures that facilitate rapid and unhindered water diffusion can minimize diffusion limitations and enhance overall water harvesting performance.

-

(2)

System design optimization. Enhancing the effective area of the sorbent is crucial for maximizing water harvesting capacity. This can be achieved by designing systems with larger surface areas or incorporating multiple sorbent layers to increase the contact area between the sorbent and the surrounding air. Additionally, optimizing energy utilization is essential to reduce reliance on external energy sources. Integrating renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind, can power the water harvesting process and improve overall energy efficiency. Implementing reasonable control strategies, such as feedback control algorithms or smart sensors, can regulate the mass transfer process and optimize water harvesting efficiency by adjusting parameters such as airflow, temperature, or humidity levels.

-

(3)

Mass transfer mechanism

The mass transfer mechanism is a major challenge that requires an in-depth understanding of the microstructure and chemistry of sorbent materials. Existing ideal sorption-diffusion-desorption models may not be fully applicable to real and complex SAWH systems. Combining the theoretical models with practical applications to simulate and optimize mass transfer behavior is a research priority. Moreover, it is essential to construct equations and perform necessary calculations to better understand and optimize the water transport inside the sorbent for continuous SAWH.

-

(4)

Energy supply

The integration of the system and the driving of the water harvesting process require energy supply, the solar-thermal conversion efficiency of PV, inevitable heat loss during the desorption process, and the condensation efficiency of the condenser will affect the overall efficiency of the system. To optimize system performance, future practical designs must carefully consider these elements. Enhancing solar-thermal conversion efficiency can be achieved through advanced materials and innovative design strategies. Minimizing heat loss during desorption requires improved insulation and heat recovery techniques. Additionally, maximizing condensation efficiency involves optimizing condenser design and employing effective cooling methods. Addressing these aspects will be crucial for developing efficient and sustainable atmospheric water harvesting systems

-

(5)

Addressing on-site water production challenges. Developing maintenance protocols and strategies is crucial to ensure the long-term performance and reliability of the MT-SAWH system. Regular cleaning, regeneration, and replacement of consumables and components should be implemented to prevent degradation and maintain optimal performance. Additionally, strategies to cope with unpredictable climatic conditions should be considered. This may involve incorporating backup water storage systems to ensure a continuous water supply during periods of low humidity or integrating weather forecasting data into control algorithms for adaptive operation, allowing the system to adjust its operation based on anticipated weather conditions.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4667 (2021). (The study quantified global urban water scarcity in 2016 and 2050 under four socioeconomic and climate change scenarios, and explored potential solutions.).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500323 (2016).

Alayli, Y., Hadji, N. E. & Leblond, J. A new process for the extraction of water from air. Desalination 67, 227–229 (1987).

Shiklomanov, I. A. World Water Resources: A New Appraisal and Assessment for the 21st Century: A Summary of the Monograph World Water Resources. UNESCO http://www.mendeley.com/research/world-water-resources-new-appraisal-assessment-21st-century/ (1998).

Liu, X., Beysens, D. & Bourouina, T. Water harvesting from air: current passive approaches and outlook. ACS Mater. Lett. 4, 1003–1024 (2022).

Wang, B., Zhou, X., Guo, Z. & Liu, W. Recent advances in atmosphere water harvesting: design principle, materials, devices, and applications. Nano Today 40, 101283 (2021).

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006).

LaPotin, A., Kim, H., Rao, S. R. & Wang, E. N. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting: impact of material and component properties on system-level performance. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1588 (2019).

Klemm, O. et al. Fog as a fresh-water resource: overview and perspectives. Ambio 41, 221–234 (2012).

Gultepe, I. et al. Fog research: a review of past achievements and future perspectives. Pure Appl. Geophys. 164, 1121–1159 (2007).

Zhou, M. et al. Vapor condensation with daytime radiative cooling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2019292118 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Recent progress on sorption/desorption-based atmospheric water harvesting powered by solar energy. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 230, 111233 (2021).

Lord, J. et al. Global potential for harvesting drinking water from air using solar energy. Nature 598, 611 (2021). (The study presented an assessment of solar-driven, continuous-mode AWH (SC-AWH) using global data.).

Aleid, S. et al. Salting-in effect of zwitterionic polymer hydrogel facilitates atmospheric water harvesting. ACS Mater. Lett. 4, 511–520 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. High-yield and scalable water harvesting of honeycomb hygroscopic polymer driven by natural sunlight. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100954 (2022).

Kumar, M. & Yadav, A. Experimental investigation of solar powered water production from atmospheric air by using composite desiccant material “CaCl2/saw wood”. Desalination 367, 216–222 (2015).

Xu, J. et al. Efficient solar-driven water harvesting from arid air with metal-organic frameworks modified by hygroscopic salt. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5202–5210 (2020).

Kim, H. et al. Water harvesting from air with metal-organic frameworks powered by natural sunlight. Science 356, 430–434 (2017).

Kim, H. et al. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting device for arid climates. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03162-7 (2018).

Ejeian, M., Entezari, A. & Wang, R. Z. Solar powered atmospheric water harvesting with enhanced LiCl /MgSO4/ACF composite. Appl. Therm. Eng. 176, 115396 (2020).

Fathieh, F. et al. Practical water production from desert air. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat3198 (2018).

Li, R., Shi, Y., Wu, M., Hong, S. & Wang, P. Improving atmospheric water production yield: Enabling multiple water harvesting cycles with nano sorbent. Nano Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104255 (2020).

Wu, Q., Su, W., Li, Q., Tao, Y. & Li, H. Enabling continuous and improved solar-driven atmospheric water harvesting with Ti3C2-incorporated metal–organic framework monoliths. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13, 38906–38915 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Ultrahigh solar-driven atmospheric water production enabled by scalable rapid-cycling water harvester with vertically aligned nanocomposite sorbent. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5979–5994 (2021).

Shao, Z. et al. Modular all-day continuous thermal-driven atmospheric water harvester with rotating adsorption strategy. Appl. Phys. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0164055 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. All-day freshwater production enabled by an active continuous sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting system. Energy Conv. Manag. 264, 115745 (2022).

Feng, A. et al. Recent development of atmospheric water harvesting materials: a review. Acs Mater. Au 2, 576–595 (2022).

Ejeian, M. & Wang, R. Z. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting. Joule 5, 1678–1703 (2021).

Bilal, M. et al. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting: a review of adsorbents and systems. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 133, 105961 (2022).

Gado, M. G., Nasser, M., Hassan, A. A. & Hassan, H. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting powered by solar energy: comprehensive review on desiccant materials and systems. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 160, 166–183 (2022).

Poredos, P., Shan, H., Wang, C., Deng, F. & Wang, R. Sustainable water generation: grand challenges in continuous atmospheric water harvesting. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 3223–3235 (2022).

Yilmaz, G. et al. Autonomous atmospheric water seeping MOF matrix. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc8605 (2020).

Díaz-Marín, C. D. et al. Heat and mass transfer in hygroscopic hydrogels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 195, 123103 (2022).

Bu, Y. et al. Bioinspired topological design with unidirectional water transfer for efficient atmospheric water harvesting. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 15147–15158 (2023).

Liang, X. et al. Direction-limited water transport and inhibited heat convection loss of gradient-structured hydrogels for highly efficient interfacial evaporation. Solar Energy 201, 581–588 (2020).

Díaz-Marín, C. D. et al. Kinetics of sorption in hygroscopic hydrogels. Nano Lett. 22, 1100–1107 (2022).

Yang, K. et al. A roadmap to sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting: from molecular sorption mechanism to sorbent design and system optimization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6542–6560 (2021).

Graeber, G., Díaz-Marín, C. D., Gaugler, L. C. & El Fil, B. Intrinsic water transport in moisture-capturing hydrogels. Nano Lett. 24, 3858–3865 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52325001 and 52170009), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader, China (No. 21XD1424000), the International Cooperation Project of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (No. 20230714100), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. and C.P. conceived the idea and jointly proposed this perspective. J.D. wrote the draft of the paper, and all co-authors proofread and revised the paper; W.C. and C.P. provided valuable suggestions, including the framework design and writing. Z. X. participated and discussed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Manabu Fujii, Ros Daw, Mengying Su, Anastasiia Vasylchenkova, Miranda Vinay.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, W., Ding, J., Peng, C. et al. Advancements in atmospheric water harvesting: toward continuous operation through mass transfer optimization. Commun Eng 3, 180 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-024-00324-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-024-00324-y

This article is cited by

-

Solar-driven atmospheric water yields under climate stress: A 23-year global data analysis

Environmental Earth Sciences (2026)