Abstract

Micro light-emitting diode devices (microLEDs) have the potential to lead the next generation of displays. However, their integration for achieving high brightness is severely limited by the challenge of their low external quantum efficiency (EQE). Another limiting factor of such devices is their Lambertian emission, which requires secondary optics to beam the emitted light in defined directions. To address these limitations, we introduce metallic and dielectric metasurfaces to improve light outcoupling efficiency and control the emission directionality of blue LEDs with micrometer size. The proposed mechanism relies on the interaction between light emitted by multiple quantum wells (MQWs) and metasurfaces supporting collective resonances that result from the coupling of localized resonances in nanoparticles throughout the array. We implemented a hexagonal diffraction lattice of resonant Al and SiO2 nanoparticles in LED devices to achieve reshaping of the far-field electroluminescence, thus demonstrating light beam control capabilities on these emitters. To expand and validate the proposed approach for small LED devices (even at the sub-micrometer scale), we integrate a subdiffraction lattice of Al nanoparticles into the device’s architecture. Implementing the proposed design allows us to control the generated light and achieve enhanced far-field emission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Micro-size light-emitting diodes (microLEDs) are at the forefront of reshaping the future of display technology, bringing a variety of potential advantages, including high contrast, fast switching speeds, long life span, high energy efficiency, and exceptional color purity1. These advantages address the demands of emerging applications, such as wearable smartwatches, augmented reality (AR) glasses, and related mobile devices. Among the most important requirements, low power consumption and high compactness are particularly pushing the boundaries of the display industry, and hence driving the evolution of LED technology, which is facing a number of industrial challenges, ranging from mass manufacturing yields to minimum luminous intensity figures. With respect to the latter, two closely related optical performance characteristics that deserve significant attention are light extraction efficiency (LEE) and angular emission2,3,4,5. Although high LEE has been demonstrated in conventional millimeter-size LEDs, light outcoupling in microLEDs has become a primary concern due to multiple detrimental factors such as the lack of encapsulation aid (e.g., silicone dome), the increase in optical losses on the mesa sidewall, and other geometrical and technological constraints preventing the use of Ag as preferred reflector material, the photoelectrochemical etching processes for surface texturing, and the epitaxial growth on micron-size patterned sapphire substrates (PSS)6,7,8,9. The lack of efficient light extraction techniques combined with the increase in photon absorption can significantly reduce the LEE in the visible wavelength range from peak levels of approximately 90% down to 20–40%, depending on the choice of materials and device architectures. The LEE dependence on pixel size does not follow a monotonic function; notably, worst-case scenarios may occur for pixel sizes above 10 μm. For lateral dimensions comparable to the epitaxial thickness (e.g., 5 μm), proper optimization of mesa sidewall angles can significantly improve the LEE10,11,12,13. Furthermore, radiation outcoupling from the light source into an adequate angular cone is essential, since it dictates the size versus efficiency trade-off of the optical system, as given by the conservation of etendue14. In this context, some of the most demanding practical applications involve the preconditioning of the source emission through secondary collimator lenses, as encountered in AR systems15. Therefore, it is often desirable for the angular radiation of microLEDs to be directional rather than Lambertian, thereby enabling miniaturization while maintaining high optical system efficiency.

Several recent studies have been conducted to address these challenges, with integrated photonic metasurfaces being reviewed as potential candidate solutions16,17,18. Integrated photonics in LED devices has been proven to offer performance advantages. For example, in ref. 19, the proposed resonant cavity (RC) LED is designed to support guided modes in ultra-thin epitaxial structures that can be coupled to photonic crystal Bloch modes. This device not only achieves strong beaming capabilities but also allows for tailoring the Purcell effect, thereby enhancing spontaneous emission. In ref. 20, enhanced LEE and beaming are demonstrated using photonic crystal structures processed on the Light Escaping Surface (LES) of conventionally thick epitaxial layers. This approach alone represents a significant advantage in terms of industrialization feasibility compared to RC-LEDs. Thus, LES nanopatterning has been more recently the subject of progressive scrutiny in the industry21. However, microLED structures with patterned LES may present several fabrication challenges. To illustrate this, Fig. 1 (a) depicts a candidate microLED structure where the LES forms an Ohmic contact with a transparent conductive oxide (TCO) layer, which laterally distributes current to the cathode metallization, serving as an optical lateral barrier. The formation of an Ohmic contact on the LES can be achieved in three steps: GaN etch-back, planarization, and TCO deposition. The anode contact comprises a composite layer with a second TCO layer, a dielectric layer with via openings, and a stack of metal layers, including a bonding layer. Due to manufacturing feasibility constraints, this pixel structure presents challenges for texturing the top LES with a coated TCO layer. Consequently, it may be advantageous to consider p-side patterning.

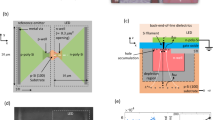

a Reference microLED structure featuring a composite mirror reflector and thin TCO layers for both n-type and p-type semiconductor contacts. The LED area is such that the lateral length is significantly greater than the epitaxial thickness, and therefore the dependence of side-walls on optical efficiency is low. b Reference microLED structure with integrated metasurface in the composite mirror reflector. The metasurface comprises a hexagonal lattice of nanodisks embedded in high refractive index material.

In this manuscript, we investigate the effectiveness of the microLED with an integrated metasurface, which prevents epitaxial damage while still offering a feasible structure featuring light outcoupling enhancement and beaming control. Figure 1 (b) presents the proposed integrated metasurface structure where the patterned nanostructures are fabricated on the TCO surface, thereby avoiding potential damage of the epitaxial layers. A high refractive index coating layer (e.g., TiO2) is applied to the nanostructures in order to maximize the field coupling between the metasurface and the source. Additionally, a low refractive index spacer may be deposited between the coated nanostructures and the anode metal reflector, thereby reducing optical losses. The nanopatterned structures may comprise metallic or dielectric nanoscale particles. Since the p-doped GaN and TCO layers are generally optically thin, the close proximity of the metasurface to the active region may further facilitate the control of the incoherent light emission, as shown previously22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Metallic metasurfaces can support various resonance modes, such as localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPR), and collective or extended plasmonic resonances (surface lattice resonances)33,34,35,36,37,38. The extended modes refer to the non-localized modes that efficiently couple with the quantum well emitters. This mode extension leads to large field enhancements not only close to the nanoparticles but also extending to the quantum wells, which are located at a distance from the metasurfaces. However, metallic nanoparticles incur Ohmic losses, which restrict the enhancement achievable through plasmonic resonances. These losses can be mitigated with the alternative use of dielectric nanoparticles. The existence of dielectric (Mie) resonances in the blue emission spectrum can be achieved with dielectric materials39,40,41,42.

The close interaction between metasurfaces and MQWs in LEDs has previously been devised and shown to offer light beaming, radiation enhancement, and LEE improvements3,26,42,43,44,45. Recently, in ref. 46, the authors discuss the necessity of partially patterning the semiconductor by etching the p-doped GaN layer in order to enhance the coupling of the emission with the supporting modes of the metasurface. Other more aggressive approaches have been explored, including etching through the active region to form nanopillar LEDs, as demonstrated in refs. 26,42. The implementation of these structures presents two primary practical challenges. Firstly, there is the issue of epitaxial reliability, which is compromised by the formation of defects and damage to the active region47. Secondly, there is an anticipated negative impact on the internal quantum efficiency (IQE) due to the associated damage and creation of surface states, which introduce additional nonradiative recombination channels48. It should be noted that similar structures employing plasmonic metasurfaces have been investigated for organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs)49. However, these may face further manufacturing challenges related to the properties and processing of organic materials.

We address here the design, optimization, and implementation of arrays of Al and SiO2 nanoparticles defining metasurfaces into microLED devices. These metasurfaces are organized in hexagonal lattices. The investigated devices feature InGaN MQWs that emit blue with an emission peak at 450 nm. We conducted wafer-level experimental investigations by electrical excitation of devices and measurements of the enhancement and beaming of the electroluminescence (EL). The experimental results show an emission enhancement of 7.5 for the Al nanoparticles and 12.3 for the SiO2 nanoparticles. The Local Kirchhoff’s Law can be used to determine the emitted power from metasurfaces from the absorptivity of the active material32. We carry out here numerical calculations based on the reciprocity theorem to optimize the device’s performance compared to the equivalent planar architectures by exploring how the integrated metasurfaces impact the directionality of the electroluminescence and the outcoupling efficiency. The goal of our study is to investigate architectures that are adequately feasible for industrialization aspects of microLEDs. Therefore, we implemented metasurfaces into operational microLED devices. We focus on pixels with lateral dimensions greater than 10μm and epitaxial thicknesses lower than 5μm (after etch-back) such that the impact of the sidewalls on LEE is much less than the aid of the metasurface.

Results

Blue LEDs and metasurface structures

The blue-emitting LED wafer was fabricated by the company Lumileds. The wafer consists of multiple layers, including a TCO layer with a thickness of 20 nm, a 50 nm layer of p-GaN, two InGaN quantum wells structure with a total thickness of 10 nm, an n-GaN layer with a thickness of 6 μm, and a 240 μm thick backside-polished sapphire substrate. For simplicity, we fabricated the devices without the (low refractive index) spacer layer shown in Fig. 1(b) as the resulting structure equally serves the purpose of demonstrating the fundamental effects we intend to investigate. ITO material is used as TCO layer to form both anode and cathode contacts. Therefore, this layer is chemically etched, defining squared areas to separate both contacts. The metasurfaces included in our study consist of Al and SiO2 nanoparticles arranged in hexagonal lattices. The Al metasurfaces are fabricated by defining their area on squared surfaces through electron beam lithography (EBL), subsequent Al deposition, and lift-off processes. For the metasurfaces of SiO2, we initially deposited a layer of SiO2 with the target thickness. Similarly to the process for Al metasurfaces, the area is defined on a square surface using EBL, followed by Au deposition and lift-off processes. Au serves as a hard mask for etching SiO2 using a plasma etching procedure to create SiO2 nanoparticles. Subsequently, the remaining Au material was removed using a chemical etching process. Then, a layer of titanium dioxide (TiO2) was deposited on the metasurfaces using atomic layer deposition (ALD) to create a conformal surrounding environment without a high refractive index contrast with the wafer. A sub-channel with a width of 5 μm was etched into the TiO2 layer to establish direct contact with the ITO layer. Therefore, rectangular pixel arrangements defining LEDs with a size of 20 μm × 300 μm are established. To electrically excite the devices, a 100 nm thick layer of Al was deposited to form anode and cathode contacts. The anode also functions as a mirror, directing the emission of the microLED device toward the sapphire substrate. Consequently, no emission is observed from the TiO2 layer. To visualize the device configuration, a schematic representation is shown in Fig. 2 (a). Top-view SEM images of the fabricated Al and SiO2 metasurfaces on the LED wafer are shown in Fig. 2 (b),(c), respectively. More details on the fabrication process can be found in the Methods section.

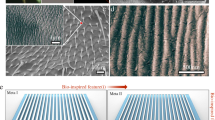

a Schematic cross-section of a LED device integrated with an Al metasurface. By applying a DC voltage, the device emits electroluminescence with a central wavelength of 450 nm from the sapphire side. The device size is 300 μm × 300 μm, divided into rectangular pixel arrangements with a size of 20 μm × 300 μm. Top view scanning electron microscope images for the hexagonal lattice structures of (b) Al and (c) SiO2 metasurfaces fabricated on the LED wafer. The scale bars correspond to 300 nm.

Numerical results

We have developed a numerical model to evaluate the far-field emission pattern that the proposed devices would generate. With this model, we can optimize the geometric parameters of the device before fabrication, such as the thickness of the TiO2 layer or the dimensions of the metasurface. To solve the electromagnetic field within the device and obtain the far-field emission pattern, we combine the finite element method (FEM) to solve the propagation of light through the metasurface, with Fresnel equations to propagate the fields along the planar stacks50. The InGaN MQWs are modeled as sheets of uniformly distributed and randomly oriented dipoles, which are inserted into the model using their angular spectrum representation51. Sidewall effects are ignored in the simulations because the pixel’s lateral dimension to thickness ratio is assumed to be large enough such that LEE enhancement is primarily induced by the effects of the metasurface. To provide greater precision and account for the anisotropy of the MQWs, we represent the orientation distribution of the dipole moments as a combination of 10% of out-of-plane dipole moments and 90% of in-plane dipole moments52.

The method used to solve Maxwell’s equations directly gives us the angular spectrum representation of the electric field, \(\hat{E}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\), in any layer of the device, including the external air region. We can directly obtain the radiation pattern produced by the LED from this angular spectrum51. More details about the model can be found in the Methods section. The focus of this manuscript is to study the impact of metasurfaces on improving the radiation of microLEDs in a narrow solid angle region around the normal direction. We have used the numerical model to optimize the geometric parameters of the metasurface, to maximize the radiated power within the far-field emission cone of ± 22.5°. We have performed the optimization process for various parameters of the device: the radius (Rdisk) and height of the nanodisks (Hdisk), the lattice constant (Llatt), and the thickness of the TiO2 layer. These are the main parameters of the device that we can control during the fabrication of the metasurfaces. The hybrid numerical model significantly reduces the computational effort required for parameter optimization. This method allows fast scanning of some parameters, such as the TiO2 layer thickness, and takes a few seconds for each combination of the other parameters. Moreover, this parameter optimization process facilitates the observation of how a specific geometry reacts to deviations resulting from fabrication tolerances.

Initially, we have optimized the microLED device for the Al metasurfaces. The optimal parameters of the Al metasurface for the given figure of merit described above are Llatt = 240 nm, Rdisk = 70 nm, Hdisk = 20 nm, and the thickness of the TiO2 layer of 210 nm. The calculated far-field intensity pattern for the optimized microLED device is shown in Fig. 3 (a). However, metallic nanoparticles introduce unavoidable Ohmic losses to the devices, limiting their effectiveness in achieving larger light-extraction enhancements. To overcome these losses, we have studied the performance of microLED, which implements dielectric (SiO2 metasurfaces). By substituting Al nanoparticles with SiO2 nanoparticles, we optimized the dimensions of SiO2 nanodisks and tuned the thickness of TiO2 to maximize the efficiency of light extraction. The optimized parameters for this microLED are Rdisk = 90 nm, Hdisk = 65 nm, arranged in a hexagonal lattice with Llatt = 220 nm, and a TiO2 layer with a thickness of 130 nm. Figure 3 (b) illustrates the simulated far-field emission pattern of the optimized microLED with the SiO2 nanodisks. For both devices, the emission pattern exhibits a six-fold symmetry, due to the hexagonal lattice that forms the metasurfaces. Figure S1 (a) and (b) display the electric field strength distribution normalized to the incident electric field (polarized along the Y-direction) for the Al and SiO2 microLED metasurface devices, respectively. The figure shows a unit cell in the YZ plane, which is defined through the center of the Al and SiO2 nanoparticles. The electric field enhancement can reach a large distance from the individual nanoparticles, enabling the coupling to distant emitters. This coupling enables the enhancement and control of the quantum-well emission.

a Emission of the microLED designed with the optimized Al metasurface. b Emission of the microLED with the SiO2 metasurface. c Emission of the reference flat device with the optimized TiO2 layer thickness. The calculated intensities are normalized to the power emitted by dipoles embedded in a homogeneous and infinitely extended layer of GaN. The emission pattern is plotted as a function of the normalized in-plane components of the wave vector, \(\frac{{k}_{x}}{{k}_{0}}\) and \(\frac{{k}_{y}}{{k}_{0}}\), ranging from 0 to 1. d Relative directional enhancement emitted by the microLED designed with Al and SiO2 metasurfaces, compared to the optimized reference. The solid angle extends from 0 sr, i.e., emission in the normal direction, up to 2π sr, i.e., emission over the whole upper hemisphere. The dashed blue line represents the emission within the emission cone of ± 30°, which is equivalent to 0.36 π sr.

As a reference in this study, we have optimized a flat device with an additional TiO2 layer to improve light outcoupling from constructive interference between the generated light and its reflection from the top Al electrode. The optimal thickness determined through this process was found to be 50 nm. Therefore, the far-field computed from the reference device with the optimum TiO2 layer shows Lambertian emission, as seen in Fig. 3 (c). All the values of the far-field intensity (in Fig. 3 (a–c)) are relative to the power emitted by the dipoles if placed in a homogeneous and infinitely extended layer of GaN, such that the integral of the far-field intensity over the whole solid angle region returns the value of the Purcell enhancement factor times the light extraction efficiency.

Introducing the Al or SiO2 metasurfaces results in a significant reshaping of the far-field emission (Fig. 3(a) and (b)), and induces a strong beaming effect concentrated within narrow emission angles. This beaming effect arises from the near-field coupling between the Al or SiO2 metasurface and the emission originating from the InGaN MQWs. The physical mechanism producing the beaming is the decay of the incoherent emitters into the extended modes supported by the metasurfaces, and the subsequent outcoupling of the emission by the metasurface53. This mechanism increases the spatial coherence of the emission by the effective delocalization over the array, which leads to the highly directional outcoupling that can be engineered by the metasurface37. The beaming is not only influenced by near-field coupling to the extended metasurface modes, but also results from constructive interference between the MQWs and the reflections from the metasurfaces. To further investigate the impact of metasurfaces on improving the extraction efficiency and beaming of light emitted by microLEDs compared to the reference device with the optimized TiO2 layer, we have determined the enhancement of the directionality of the emission (DE),

where Ims and Iref are the emission intensities from the microLED with the metasurface and the reference, respectively. ϕ represents the azimuth angle, which ranges from 0 to π/2, while \({\theta }^{{\prime} }\) is the polar angle, which is defined in air and can vary within the range of 0 to π/2. Subsequently, we convert \({\theta }^{{\prime} }\) to the solid angle (sr) using \({{\Omega }}=2\pi (1-\cos (\theta ))\). We achieved a directionality enhancement of 1.27 and 2.65 within the ± 30° emission cone for the optimized microLED featuring Al and SiO2 metasurfaces, respectively, compared to the optimized reference device, as demonstrated in Fig. 3 (d). However, as the collection solid angle increases, the enhancement reduces, reaching levels lower than 1 and 1.67 for the entire solid angle cone (2π) for the Al and SiO2 metasurfaces, respectively. This result confirms that the beaming effect introduced by plasmonics or dielectric metasurfaces improves the emission of globally optimized microLEDs in defined directions. Despite the fact that there was a net reduction in the integrated emission of the Al metasurfaces over all angles due to Ohmic losses in the metal.

Experimental results

We have experimentally investigated three different types of metasurface LED devices. The first, which we call microLED1, consists of a metasurface formed by a hexagonal diffraction array of aluminum (Al) nanoparticles on top of InGaN MQWs to achieve directional enhancement of the EL. The specific parameters for Al nanoparticles in microLED1 are detailed in the Numerical Results section. The second type (microLED2) consists of a similar sub-diffraction metasurface at the emission wavelengths of the MQWs. The absence of diffractive coupling of individual nanoparticles and the concomitant absence of diffractive scattering leads to enhanced omnidirectional light outcoupling. Sub-diffraction metasurfaces will contribute to smaller LED devices up to 1 μm scale, where collective or extended mode effects in metasurfaces are not possible because of their small size. The smallest microLED possible will be formed by a single nanoparticle. For the last type (microLED3), we replace the Al nanoparticles in the hexagonal diffraction array with SiO2 nanoparticles to avoid Ohmic losses in the metal and further improve the LEE. The specific parameters for SiO2 nanoparticles in microLED3 are detailed in the Numerical Results section. In our experiments, the references are the same device structures, but without the metasurfaces and the TiO2 layer. The reference devices undergo measurements within the same sample substrate as those of the three devices for a direct comparison. Further details on the optimization process are available in the Methods section and the supporting information document.

Al diffraction metasurface LED (microLED1)

We first focus on the device with the optimized hexagonal Al diffraction metasurface (microLED1), and the reference device with the same structure but without the Al metasurface and the TiO2 layer used to match the refractive index of the upper medium with the GaN substrate. This index matching is important to enable the radiative coupling between the nanoparticles in the array, leading to the extended mode response of the metasurface54,55. An optical image of the fabricated microLED1 device is presented in Fig. S1 (a). In our experimental analysis, we have investigated devices with a size of 300 μm × 300 μm. For this investigation, we used Fourier microscopy combined with a two-probe station featuring a 25 μm tip diameter (further details on the experimental setup are provided in the “Methods” section). This configuration enables us to electrically excite the devices, collect the EL, and capture the far-field emission pattern. The emitted blue light can be enhanced by coupling the plasmonic resonances of the optimized Al metasurfaces with the generated light from InGaN MQWs.

For electrical injection of charge carriers in the MQWs, the anode should be connected to the p-GaN layer, while the cathode should be connected to the n-GaN layer. To establish the cathode contact, an etching process is required to etch ITO/p-GaN/InGaN MQWs/n-GaN, allowing the contact to be placed on the n-GaN layers (for clearer visualization, refer to Fig. 2 (a)). This etching process has significant challenges and, therefore, we propose here an alternative method to electrically excite microLED devices without the need for etching. For the devices, we chemically etched the ITO layer and manufactured both anode and cathode contacts on the surface of the device (as discussed in Section “Results” and illustrated in Fig. 2 (a)). By applying a voltage difference to the contacts, the injected current experiences a significantly high resistance, which prevents it from reaching the n-GaN layer. This situation can be represented in a circuit model as a connection of two diodes in series, arranged in an antiparallel orientation concerning the supplied voltage. To overcome the challenge presented by the high resistance of the reverse diode, we used a high-voltage pulse generator to apply short pulses with a pulse duration of 5 ms and 25 V to the devices (more details can be found in the Methods section). These pulses are applied to reach the breakdown region while the diode is in reverse bias, called diode burning. It takes approximately 10 pulses to cause the diode to break down. Through this process, a current pathway for the anode is established by selectively breaking down one diode in the reverse configuration through a controlled burning process. By establishing a permanent current path through the p-GaN layer of the microLED devices, we enable the operation of the devices under forward bias conditions, effectively providing access to the charges to the n-GaN layer. A current-voltage curve is obtained by varying the applied voltage and measuring the current to ensure that the device operates in the forward bias, as shown in Fig. S3. This curve shows the expected single-diode characteristic.

We conducted measurements of the EL far-field emission pattern of microLED1. The EL was collected using a Nikon Plan Fluor 100x objective with a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.9 and directed to a spectrometer (Ocean Optics HR2000+) or a CCD camera (Thorlabs: 1500M-GE) combined with a bandpass filter with a center wavelength of 450 nm and a bandwidth of 10 nm. Note that the collected emission angles (θ) are limited to the NA of the objective, resulting in a range of θ from −64° to 64°. To quantify the device performance, we measured EL spectra at various current densities (A/cm2) by controlling the applied voltage across the junction. For both devices (microLED1 and the reference), the collected EL counts through the bandpass filter are integrated and plotted versus the current density, as illustrated in Fig. S4 (a). Subsequently, the integrated EL is divided by the injected electrical power density (voltage × current/device’s area) to estimate the relative emission power. The relative emission power curves for microLED1 and the reference are normalized to the maximum value obtained from the reference. This normalization enables us to determine the relative enhancement of the emission as a function of current density, as depicted in Fig. S5 (a).

To quantify the differences between microLED1 and the reference device, we select an operating current density of 66 A/cm2 for microLED1, which corresponds to the maximum relative emission power (as illustrated in Fig. S4 (a)), and compare the EL with the emission of the reference at a similar current density (70 A/cm2). This far-field emission intensity (I(kx, ky)) captured by the CCD camera is represented in reciprocal space coordinates, defined as \({k}_{x}={k}_{0}\sin \theta \cos \phi\) and \({k}_{y}={k}_{0}\sin \theta \sin \phi\), where k0 = 2π/λ is the wave vector in vacuum. The far-field EL measured from microLED1 is shown in Fig. 4 (a) and exhibits a six-fold symmetry, due to the hexagonal lattice forming the Al metasurface. This metasurface enables precise control of the EL emission direction. In contrast, the far-field emission of the reference device shows a Lambertian emission, lacking any directionality over the emission angles (Fig. 4 (b)). The beaming effect induced by the metasurfaces is crucial for numerous lighting applications where secondary optics are otherwise required to guide the emitted light.

a Electroluminescence of microLED1 and (b) electroluminescence of the reference device without Al metasurface and TiO2 layer. For both images, the x axis is kx/k0, and the y axis is ky/k0, and they have a radius of 0.9, which corresponds to the numerical aperture of the objective used in the setup. c Far field electroluminescence of microLED1 as a function of \(\sin \theta\), with θ the emission angle at kx = 0 (red-dashed line in (a)) and ky = 0 (blue-dashed line in (a)) and electroluminescence of the reference device for ky = 0 (black-dashed line in (b)). d Directional emission enhancement of microLED1 compared to the reference device as a function of the emission solid angle. The vertical dashed black line indicates the emission within 0.36 π sr, which is equal to the emission within the ± 30∘ emission cone. e EL emission spectrum integrated over the emission angles collected by the objective of microLED1 (red curve) and the reference (black curve).

To further elucidate the light beaming, we have made 2D cuts in the far-field EL emission intensity pattern as a function of \(\sin \theta\) for the microLED1 device with ky = 0 and kx = 0, as well as for the reference device with ky = 0. These cuts are shown in Fig. 4 (c). We achieve a strong beaming effect in the microLED1 device, characterized by a high emission enhancement at θ = 0°. To assess the EL enhancement across the angular emission angles resulting from the Al metasurfaces, we have determined the emission directionality enhancement (DE). We have normalized the emission from the microLED1 device to the reference device using Eq. (1) and transformed the polar angle (θ) into the solid angle (sr). The microLED1 device shows a DE of approximately 8.6 within the emission cone of ± 30°, corresponding to an NA = 0.5, as illustrated in Fig. 4 (d). This enhancement decreases as the emission solid angle increases until it reaches a DE of 7.5 for the entire solid angle collected. The larger enhancement of the measured DE than the simulation presented in Section 3 is because the simulation is compared to an optimized planar microLED reference, while the measurements are compared to the planar reference that can be fabricated and measured in the same LED substrate as the metasurface LED.

We have also simulated the measured reference LED to evaluate better the performance of microLED1 and compare it to the measurements. The simulated far-field emission pattern of the reference device exhibits a Lambertian emission, as shown in Fig. S6 (a). When comparing the emission of microLED1 with the reference device, the microLED1 device emits more than 13.9 times the power emitted by the reference within the ± 30° emission angles. Similarly to the experiment, the ratio between the emitted powers decreases as the solid angle increases, reaching a value of 5.8 for the emission over the entire hemisphere, as shown in Fig. S6 (b). We achieve good qualitative agreement between the experimental results and the simulations, including both the far-field emission pattern and the beaming effect. However, the simulated beaming effect (Fig. 3 (a)) is more pronounced than the values obtained in the experiments. This discrepancy could be attributed to the rough and conformal layer created by the deposition of TiO2, which was not considered in the numerical calculations (the characterization of the roughness of TiO2 by atomic force microscopy (AFM) is presented in Fig. S7 (a)).

Furthermore, we have also carried out measurements of the EL spectra of microLED1 and the reference device at the same current densities. The results indicate an approximate twelve-fold increase in the emission spectrum of the microLED1 device compared to the reference device, as shown in Fig. 4 (e). The EL beaming and enhancement of emission confirm the ability of a simple design featuring a hexagonal lattice of Al nanoparticles to control the directionality of emission while improving the light-outcoupling efficacy of a microLED device. In addition, we have calculated the beam efficiency for microLED 1 and the reference device. The beam efficiency is defined as the ratio of emission within a specific solid angle to the total emission of this device, as illustrated in Fig. S8.

Al sub-diffraction metasurface LEDs (microLED2)

The previously discussed microLED1 device features a hexagonal diffraction lattice, which imposes limitations on the minimum dimensions due to the character of the metasurface56. To quantify the effect of the size of the metasurface on the beaming effect, we have computed the far-field emission pattern for a finite number of Al nanoparticles. With approximately an area of 2 μm × 2 μm (8 periods), we obtained a beamed light emission comparable to that achieved by an infinite Al metasurface, as depicted in Fig. S9.

To demonstrate the potential realization of a working device of sub-micrometer size, we optimized and manufactured microLED2 that incorporates Al metasurfaces with nanoparticles with a diameter of 95 nm, and height of 30 nm in a subdiffraction lattice with a lattice constant of 125 nm. This design avoids diffractive coupling between the nanoparticles, while their near-field coupling is also negligible. Therefore, the emission intensity normalized by the emitting area in microLED2 is constant. Subsequently, a layer of 110 nm of TiO2 was deposited on the Al metasurfaces, followed by the top Al contact (anode contact). To characterize the fabricated device, we acquired a focused ion beam (FIB) scanning electron microscope (SEM) image, as shown in Fig. 5 (c). The FIB image provides a cross-sectional perspective of the microLED2 device, revealing all layers except the sapphire substrate. It should be noted that the platinum (Pt) layer on top of the Al contact is deposited to achieve a high-resolution image. The deposited TiO2 layer has a conformal shape that follows the shape of the nanoparticles, resulting in a conformal Al contact as well.

a Experimental far-field EL emission pattern from microLED2 collected by the Fourier setup using a CCD camera with a bandpass filter with a bandwidth of 10 nm and a center wavelength of 450 nm. b EL spectra of microLED2 and of the reference device. c FIB-SEM image of microLED2, showing the different layers. The Pt layer on top does not correspond to the device, but is deposited for the FIB-SEM measurements. The scale bar corresponds to 200 nm.

We have used the same methodology as discussed for microLED1 to realize contacts and electrically inject carriers into the MQWs. We have measured the EL spectra for different current densities and used the reference device fabricated on the same substrate but without the additional TiO2 layer and the Al metasurface. The integrated emission over the spectrum is shown in Fig. S4(b) as a function of the current density. To compare the EL of microLED2 with the reference, we chose the operating current density at which the maximum relative emission power was observed, as shown in Fig. S5 (b) (~50 A/cm2). We have obtained the far-field emission pattern, revealing a Lambertian emission in the presence of the hexagonal sub-diffraction lattice, as depicted in Fig. 5 (a). Applying the same current density of 50 A/cm2, we have conducted measurements of the EL emission spectra. Figure 5 (b) shows these spectra for microLED2 and reference devices, where an enhancement factor of 2.6 is observed.

SiO2 diffraction metasurface LEDs (microLED3)

The enhancement achieved by implementing Al metasurfaces in microLEDs addresses important limitations in the development of the next generation of LED displays. However, metallic nanoparticles introduce unavoidable Ohmic losses to the devices, limiting their effectiveness in achieving larger light-extraction enhancements. To overcome these losses, we have studied the performance of microLED3, which implements dielectric (SiO2 metasurfaces. To experimentally investigate the optimized device, we have fabricated microLED3 as described in Section “Results”. An SEM image illustrating the fabricated SiO2 metasurfaces is presented in Fig. 2 (c). In addition, an optical image of the fabricated microLED3 device is shown in Fig. S2 (b). The device allows for a direct comparison with the reference, which lacks both the TiO2 layer and the metasurface. We followed the same experiment methodology applied to study the performance of the microLEDs devices with Al metasurfaces and collected the emitted EL from both microLED3 and the reference. Subsequently, we integrated the emission spectra, peaking at 450 nm, for different current densities, as depicted in Fig. S4(c). The integrated spectra were then normalized to the injected power density, as presented in Fig. S5(c).

Both devices, microLED3 and the reference, were operated at the same current density, ~37 A/cm2, corresponding to the maximum relative emission power achieved by microLED3. The measured far-field emission pattern from microLED3 shows a reshaping of the emitted light, displaying a hexagonal pattern due to the hexagonal SiO2 metasurface, as shown in Fig. 6(a). However, this hexagonal pattern is considerably weaker than the calculated far-field emission pattern in Fig. 6(a). This difference can be attributed to the quality of the deposited TiO2 layer, which exhibits cracks and lacks uniformity, as shown in Figs. S2 (b) and (c), and S7 (b). Consequently, fabrication imperfections impact both the emission pattern and the overall device’s efficiency. The non-uniformity of the TiO2 layer has a detrimental impact on the emission pattern. In contrast, it might introduce additional scattering, leading to a higher LEE compared to the numerical calculations.

a Fourier measurement of the far-field EL emission pattern from microLED3 collected using a bandpass filter with a bandwidth of 10 nm and a center wavelength of 450 nm. The x-axis represents kx/k0, and the y-axis represents ky/k0, with values ranging from -0.9 to 0.9. b EL emission spectra of microLED3 (red curve) and the reference (black curve).

In Fig. 6 (b), the EL spectra of both microLED3 and the reference device are shown. For microLED3, we achieve an integrated LEE of 21.4 compared to the reference device. Consequently, we have conducted a numerical comparison between microLED3 and the flat reference device without the TiO2 layer and the metasurface. The outcome reveals a DE of 29 within the emission cone of ± 30°. However, this enhancement gradually decreases at higher solid angles, eventually reaching a value of 12.3 over the entire hemisphere, as shown in Fig. S6 (b).

Discussion and conclusion

We have demonstrated the potential to integrate both metallic and dielectric metasurfaces into microLED devices, effectively coupling optical modes in the metasurfaces with the emission of InGaN MQWs. This integration not only generates a beaming effect for both types of metasurfaces but also enhances the light extraction efficiency, especially for dielectric metasurfaces. We have developed a numerical model to optimize the performance of these devices. This model enables us to study the impact of the metasurface’s geometrical parameters and the device’s architecture on both the far-field emission pattern and the light-extraction enhancement. Arrays of Al and SiO2 metasurfaces have been fabricated on GaN wafers, followed by the fabrication of blue LED emitters, and the electroluminescence has been experimentally investigated using a Fourier setup. The proposed Al metasurfaces have been configured in diffraction and sub-diffraction hexagonal lattices, enabling us to investigate beaming effects enabled by the extended mode response of the metasurfaces as a result of radiative coupling between nanopartices, and the light extraction by scattering from individual nanoparticles. Beamed directional emission enhancements of 3.3 and 9 times within a narrow solid-angle emission ( ± 30°) are reported for Al and SiO2 metasurfaces, respectively, compared to the emission of optimized planar microLEDs (without metasurface). The integrated angular emission from SiO2 metasurface microLEDs also exceeds the integrated emission of our optimized reference microLEDs.

Our approach illustrates that metasurfaces offer a distinctive way of manipulating the light generated from microLED devices to achieve beaming and/or light extraction enhancement, without the need to etch the active material to form mesa structures. The beaming obtained from the devices is important for various applications, such as VR and head-up displays, that demand secondary optics to focus the emitted light from microLED devices. High light extraction efficiencies from microLEDs, as demonstrated in this manuscript, open new opportunities for high-resolution LED displays.

Given that electron beam lithography is unsuitable for mass production due to its low throughput and high cost, alternative techniques such as nano-imprinting lithography present promising solutions. Nano-imprinting stands out as a strong candidate for large-area metasurface production, offering high throughput at a low cost57.

Methods

Numerical model

To solve the electromagnetic field within the device and obtain the far-field emission, we use a model that combines the finite element method (FEM) to solve light propagation through the metasurface, and Fresnel equations to propagate the fields along the planar stacks50. The quantum wells are modeled as sheets of uniformly distributed and randomly oriented dipoles that are inserted into the model using their angular spectrum representation51. The FEM is used to calculate reflection and transmission matrices that link the amplitudes of incoming plane waves with the amplitudes of their diffraction orders produced by the metasurface. These matrices are then coupled with the Fresnel equations to build a larger system matrix that models the field propagation along all the layers of the device. The quantum wells, modeled as a distribution of dipoles, are included as an additive term in the active region51,58. Note that the approach we use is a variation of the Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) that allows us to directly obtain the field in every layer of the device, instead of at the outermost layers only, as it happens with the TMM50. The primary reason for employing a combination of both methods, rather than relying only on FEM simulations, is to reduce the computational effort necessary to address light propagation through the relatively thick 6 μm GaN layer. Furthermore, this hybrid approach allows us to explore variations in geometry, such as TiO2 layer thickness, with minimal computational overhead. Also, using a plane wave basis to expand the electromagnetic fields in each layer of the device allows us to use an efficient approximation to incoherence effects in the GaN layer, without the need to solve the problem for many different excitation wavelengths. A schematic of the numerical method is illustrated in Fig. S10 ((a) and (b)), and additional details can be found in the SI.

Sample fabrication

The wafer was manufactured by Lumileds, and the GaN layer was grown using a metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) reactor on a polished sapphire substrate. A 20 nm layer of indium tin oxide (ITO), which serves as a conductive layer, was deposited by magnetron sputtering. Electron beam lithography (EBL) was used to define the area where ITO etching was required to separate the contacts. A solution of HCL:TO2 in a 1:1 ratio was used to etch the ITO. Subsequently, another round of EBL exposure followed by a lift-off process was used to fabricate the metasurfaces on top of the ITO layer. The process continued with the deposition of a TiO2 layer using atomic layer deposition (ALD). Another EBL exposure was necessary to define the sub-contact channel between the top contact and the ITO layer. The TiO2 layer was etched using reactive ion etching (RIE). An additional EBL exposure was required to define the positions of the contacts. Finally, a layer of Al with a thickness of 100 nm was deposited using an electron beam evaporator.

EL and Fourier measurements

A working microLED device requires electrical injection of charges to characterize and evaluate its performance in terms of light extraction enhancement and EL beaming. The size of the devices imposes restrictions on the size of the electrical contacts, thus requiring the use of a microprobe station. Therefore, we have assembled a Fourier microscope setup, which is combined with a microprobe station connected to a DC voltage source. This configuration enables us to apply a current to the LED devices, collect the EL spectrum as a function of the excitation current density, and capture both real and Fourier space images using CCD cameras. The emitted light was collected by 0.9NA Nikon Plan Fluor 100x and directed to a CCD camera or a spectrometer. To capture the far-field pattern, a bandpass filter with a center wavelength of 450 nm (bandwidth of 10 nm) is placed in front of the CCD camera. To measure the EL spectrum, we direct the emitted light to a spectrometer (Ocean Optics 2000+). A schematic of the experimental setup used to characterize the fabricated microLED devices is illustrated in Fig. S11, and additional details can be found in the SI.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and supporting information. Additional data related to this article can be requested from the authors.

References

Wu, Y., Ma, J., Su, P., Zhang, L. & Xia, B. Full-color realization of micro-LED displays. Nanomaterials 10, 2482 (2020).

Zhmakin, A. I. Enhancement of light extraction from light emitting diodes. Phys. Rep. 498, 189–241 (2011).

Gu, X., Qiu, T., Zhang, W. & Chu, P. K. Light-emitting diodes enhanced by localized surface plasmon resonance. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 1–12 (2011).

Lee, H. K., Ko, Y. H., Raju, G. S. R. & Yu, J. S. Light-extraction enhancement and directional emission control of GaN-based LEDs by self-assembled monolayer of silica spheres. Opt. Express 20, 25058–25063 (2012).

Dang, S. et al. Light-extraction enhancement and directional emission control of GaN-based LED with transmission grating. Optik 125, 3623–3627 (2014).

Lee, Y.-J., Kuo, H.-C., Lu, T.-C., Su, B. & Wang, S. Fabrication and characterization of gan-based leds grown on chemical wet-etched patterned sapphire substrates. J. Electrochem. Soc. 153, 1106 (2006).

Shchekin, O. et al. High performance thin-film flip-chip InGaN–GaN light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 071109 (2006).

Gao, H. et al. Enhancement of the light output power of InGaN/GaN light-emitting diodes grown on pyramidal patterned sapphire substrates in the micro-and nanoscale. J. Appl. Phys. 103 (2008).

Flemish, J., Soer, W.: Development and industrialization of InGaN/GaN LEDs on patterned sapphire substrates for low cost emitter architecture. (Technical report, Lumileds LLC, 2015).

Hwang, D., Mughal, A., Pynn, C. D., Nakamura, S. & DenBaars, S. P. Sustained high external quantum efficiency in ultrasmall blue III–nitride micro-leds. Appl. Phys. Express 10, 032101 (2017).

Olivier, F., Daami, A., Licitra, C. & Templier, F. Shockley-read-hall and Auger non-radiative recombination in GaN based LEDs: A size effect study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 022104 (2017).

Bulashevich, K. A., Konoplev, S. S. & Karpov, S. Y. Effect of die shape and size on performance of III-nitride micro-leds: A modeling study. In: Photonics, vol. 5, p. 41 (2018).

Park, J., Baek, W., Geum, D.-M. & Kim, S. Understanding the sidewall passivation effects in AlGaInP/GaInP micro-led. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 17, 29 (2022).

Baruah, L. Microled microdisplays: an invention fueled by augmented reality. Inf. Disp. 38, 13–18 (2022).

Mukawa, H. et al. A full-color eyewear display using planar waveguides with reflection volume holograms. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 17, 185–193 (2009).

Ndiaye, A. et al. Enhanced conversion efficiency and tailored radiation patterns assisted by photonic-crystal light-extractors in compact MQW based color-converters for μled applications. In: Light-Emitting Devices, Materials, and Applications XXVI, vol. 12022, pp. 167–175 (2022).

Ndiaye, A., Nguyen, H. S., Seassal, C., Drouard, E. & Ben Bakir, B. Farfield pattern and guided-mode extraction analysis for highly directional emission from photonic-crystal based AlGaInP/InGaP MQW color-converters in thin-film geometry. AIP Adv. 12, 045122 (2022).

Schubert, M. F. & Hammond, A. M. Fourier modal method for inverse design of metasurface-enhanced micro-leds. Opt. Express 31, 42945–42960 (2023).

Wierer Jr, J. J., David, A. & Megens, M. M. III-nitride photonic-crystal light-emitting diodes with high extraction efficiency. Nat. Photonics 3, 163–169 (2009).

Wierer, J. et al. Ingan/gan quantum-well heterostructure light-emitting diodes employing photonic crystal structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3885–3887 (2004).

Ohya, M., Naniwae, K., Suzuki, A., Kondo, T. & Mori, M. LED element. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. US 9,634,188 B2 (2017).

Greffet, J.-J. et al. Coherent emission of light by thermal sources. Nature 416, 61–64 (2002).

Auer-Berger, M., Tretnak, V., Wenzl, F.-P., Krenn, J.R. & List-Kratochvil, E.J. Aluminum-nanodisc-induced collective lattice resonances: controlling the light extraction in organic light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 173301 (2017).

Joo, W.-J. et al. Metasurface-driven OLED displays beyond 10,000 pixels per inch. Science 370, 459–463 (2020).

Khaidarov, E. et al. Control of LED emission with functional dielectric metasurfaces. Laser Photonics Rev. 14, 1900235 (2020).

Mohtashami, Y. et al. Light-emitting metalenses and meta-axicons for focusing and beaming of spontaneous emission. Nat. Commun. 12, 3591 (2021).

Abdelkhalik, M. S., Vaskin, A., López, T., Abass, A. & Rivas, J. G. Unveiling light collection and pump enhancement from quantum wells with plasmonic metasurfaces using power dependent measurements. J. Phys. Photonics 5, 025001 (2023).

Liu, Z., Ren, K., Dai, G. & Zhang, J. A review on micro-led display integrating metasurface structures. Micromachines 14, 1354 (2023).

Kaito, S. et al. Enhancement of the bandgap emission from GaN epilayer by surface plasmon resonance in the quadrupole oscillation mode using Ag nanoparticles protected by an oxide thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 151110 (2023).

Oto, T. et al. Plasmonic red-light-emission enhancement by honeycomb-latticed InGaN/GaN ordered fine nanocolumn arrays. Appl. Phys. Express 16, 115001 (2023).

Kim, T., Uthirakumar, P., Cho, Y.-H. & Lee, I.-H. Enabling localized surface plasmon emission from InGaN/GaN nano-leds integrated with Ag/SiO2 nanoparticles. ACS Photonics 11, 570–579 (2024).

Bailly, E. et al. 2d silver-nanoplatelets metasurface for bright directional photoluminescence, designed with the local Kirchhoff’s law. ACS Nano 18, 4903–4910 (2024).

Muskens, O., Giannini, V., Sánchez-Gil, J. A. & Gómez Rivas, J. Strong enhancement of the radiative decay rate of emitters by single plasmonic nanoantennas. Nano Lett. 7, 2871–2875 (2007).

Auguié, B. & Barnes, W. L. Collective resonances in gold nanoparticle arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 143902 (2008).

Sung, J.-H. et al. Enhanced luminescence of GaN-based light-emitting diode with a localized surface plasmon resonance. Microelectron. Eng. 86, 1120–1123 (2009).

Knight, M. W. et al. Aluminum plasmonic nanoantennas. Nano Lett. 12, 6000–6004 (2012).

Lozano, G., Rodriguez, S. R., Verschuuren, M. A. & Gómez Rivas, J. Metallic nanostructures for efficient LED lighting. Light. Sci. Appl. 5, 16080–16080 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. The rich photonic world of plasmonic nanoparticle arrays. Mater. today 21, 303–314 (2018).

Bouchet, D. et al. Enhancement and inhibition of spontaneous photon emission by resonant silicon nanoantennas. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 064016 (2016).

Gili, V. F. et al. Monolithic AlGaAs second-harmonic nanoantennas. Opt. Express 24, 15965–15971 (2016).

Vaskin, A., Kolkowski, R., Koenderink, A. F. & Staude, I. Light-emitting metasurfaces. Nanophotonics 8, 1151–1198 (2019).

Iyer, P. P. et al. Unidirectional luminescence from InGaN/GaN quantum-well metasurfaces. Nat. Photonics 14, 543–548 (2020).

Okamoto, K. et al. Surface-plasmon-enhanced light emitters based on InGaN quantum wells. Nat. Mater. 3, 601–605 (2004).

Wu, R.-N. et al. Surface plasmon coupling of Ag nanoparticles with InGaN/GaN quantum wells for enhancing the emission efficiency of light-emitting devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 8288–8297 (2022).

Abdelkhalik, M. S. et al. Surface lattice resonances for beaming and outcoupling green μ leds emission. Nanophotonics 12, 3553–3562 (2023).

López-Fraguas, E. et al. Tripling the light extraction efficiency of a deep ultraviolet LED using a nanostructured p-contact. Sci. Rep. 12, 11480 (2022).

Wang, X. & Samukawa, S. Damage-free neutral beam etching for gan micro-leds processing. Semicond. Semimet. 106, 203–221 (2021).

Smith, J. M. et al. Comparison of size-dependent characteristics of blue and green InGaN microLEDs down to 1 μm in diameter. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 071102 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. Reflecting metagrating-enhanced thin-film organic light emitting devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 053302 (2021).

Brekhovskikh, L. Waves in Layered Media, vol. 16. (Elsevier, 2012).

Novotny, L., Hecht, B. Principles of Nano-optics. Cambridge University Press, ??? (2012).

Masui, H., Fellows, N. N., Nakamura, S. & DenBaars, S. P. Optical polarization characteristics of light emission from sidewalls of primary-color light-emitting diodes. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 23, 072001 (2008).

Vecchi, G., Giannini, V. & Gómez Rivas, J. Shaping the fluorescent emission by lattice resonances in plasmonic crystals of nanoantennas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 146807 (2009).

Auguié, B., Bendana, X. M., Barnes, W. L. & Abajo, F. J. G. Diffractive arrays of gold nanoparticles near an interface: Critical role of the substrate. Phys. Rev. B 82, 155447 (2010).

Murai, S. et al. Hybrid plasmonic-photonic modes in diffractive arrays of nanoparticles coupled to light-emitting optical waveguides. Opt. express 21, 4250–4262 (2013).

Rodriguez, S., Schaafsma, M., Berrier, A. & Rivas, J. G. Collective resonances in plasmonic crystals: Size matters. Phys. B Condens. Matter 407, 4081–4085 (2012).

Verschuuren, M. A. Substrate conformal imprint lithography for nanophotonics. Ph. D. Thesis (2010).

Lukosz, W. Light emission by multipole sources in thin layers. I. Radiation patterns of electric and magnetic dipoles. JOSA 71, 744–754 (1981).

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to Aleksandr Vaskin for engaging in discussions and initiating ideas for potential metasurface materials. The authors thank Minpeng Liang for designing the illustration figure of the device. This work has been financially supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO), domain Applied and Engineering Sciences (TTW), through grant no 17100 (NanoLEDs).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiments were conceived by J.G.R. and T.L., and carried out by M.A. and T.R. with the assistance of M.B. and L.J. The data analysis was performed by M.A. with support from T.L. and J.G.R. The calculations were performed by X.G. The paper was written by M.A., X.G., T.J., T.L., M.B., L.J., and J.G.R.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Jaehyuck Jang and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Anastasiia Vasylchenkova and Rosamund Daw].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelkhalik, M.S., Garcia-Santiago, X., van Raaij, TJ. et al. Enhanced and directional electroluminescence from MicroLEDs using metallic or dielectric metasurfaces. Commun Eng 4, 63 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00401-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00401-w