Abstract

Low-energy-use morphing structures can greatly impact various engineering disciplines. In aeronautics, aircraft wings must adapt to diverse flight conditions to ensure optimally shaped wings for enhanced performance, maneuverability, and efficiency. Shape morphing enables aircraft to maximize aerodynamic performance but often requires complex system designs with heavy components, leading to continuous energy consumption and reduced payload capacity. To address these challenges, we introduce a new class of additively manufactured, bistable rotating elements designed for aircraft wing structures. Leveraging geometric nonlinearity, our proposed design creates bistable geometries that enable substantial and reversible alterations in the wing’s chordwise geometry. This eliminates the need for continuous energy use during various maneuvers, thus conserving fuel or battery usage and contributing to weight reduction, particularly in Uncrewed Air Vehicles (UAVs). The proposed multistable morphing wing offers mechanical and geometric tunability, allowing for precise adjustments in stiffness and degrees of rotation. Experimental validation, including wind tunnel tests, and Finite Element Analysis confirm the mechanical reliability of the multistable rotational morphing wing. Demonstrating its ability to maintain the morphed shape across various flight conditions, this concept shows promise for enhancing UAV performance in real-world applications and extending its potential to fields beyond aerospace engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aircraft traverse various flight regimes–takeoff, climb, cruise, descent, approach, and landing, to name a few—each with distinct requirements on the wing shape that is responsible for performance, maneuverability, and efficiency. This variability makes aircraft an ideal subject for studying the benefits of bistable structures. Fixed-wing aircraft typically utilize ailerons, flaps, and slats to increase lift or drag and to affect aerodynamic control. These elements are segmented portions of the wing’s leading or trailing edge, usually actuated by servo motors or hydraulics. Flaps and slats create the largest changes in wing shape, generating substantial increases in lift needed for takeoff and landing. However, they require constant energy input in the actuated state. In contrast, relatively small magnitude aileron deflections are used for aircraft control. Fixed-wing Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), especially smaller ones, typically do not have flaps due to weight, space, energy, and cost constraints. However, they could substantially benefit from active control surfaces, resulting in a net weight reduction and increased efficiency and versatility. For instance, such control surfaces could also allow for reducing the number of rotors from four to two in tail-sitter UAVs, leading to improved performance and operational capabilities. By incorporating energy-efficient actuating systems into control surfaces, the necessity for additional motors to regulate flight direction can be eliminated.

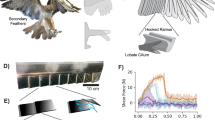

Avian-inspired morphing wing designs enhance aviation performance and efficiency through adaptability and energy-efficient mechanisms, which are crucial for complex maneuvers like hovering and gliding. These designs draw from biological architecture, incorporating feather-like structures and wing folding capabilities1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Innovations such as elastic honeycomb-connected slats for planform modifications8, partitioned trailing edges9, and inflatable wings10 address the challenges of varying flight conditions. Z-shaped wings11,12,13, morphing angle winglets14,15,16,17, chordwise18,19,20,21,22,23,24, and spanwise morphing25,26,27 further optimize aerodynamic performance, reduce noise, and improve fuel efficiency. These developments and challenges of morphing wings, including the need for advanced materials, integrated morphing systems, improved actuation, and sensing technologies, have also been extensively reviewed28. The use of autonomous material composites indicates a promising direction for achieving adaptability and morphing at an avian scale29.

In the expansive domain of morphing aircraft, camber morphing has emerged as particularly advantageous, distinguishing itself among a range of innovative technologies by enhancing control authority and efficiency through simple mechanisms30,31. Its unique contributions to the design of wings and airfoils play a pivotal role in improving the efficiency and maneuverability of aerial systems32,33. The Fishbone Active Camber (FishBAC) system, inspired by compliant biological structures, features a thin, bending spine with stringers. It substantially improves performance over traditional, non-morphing airfoils across various flight conditions, showing effectiveness nearly equivalent to more intricate mechanisms despite its simplicity34,35. The Spanwise Morphing Trailing Edge (SMTE) utilizes embedded Macro-Fiber Composites (MFC) and a flexure box mechanism, created through multi-material 3D printing and based on the expanded cascading bimorph concept36. This design optimizes spanwise lift distribution by spacing actuators along the wing and employing an elastomer to maintain continuity and efficiency of the morphing trailing edge36. A multifunctional morphing airfoil that integrates MFCs as both skin and actuators, with internal piezoelectric flex sensors for autonomous adaptation to flow conditions has also been demonstrated37. Post-Buckled Precompressed (PBP) actuator technology, which enhances piezoelectric actuator performance through axial compression, increases stroke and blocked force capability while reducing system weight, increasing bandwidth, and lowering power consumption38. A low-fidelity aeroelastic model for an active camber morphing wing incorporates steady and unsteady aerodynamic models was explored39, which identified critical speed requirements and key design factors like segment length to chord ratios and relative stiffness, simulating flap-like functionality. An autonomous camber morphing concept featuring a temperature-responsive increase in the camber of helicopter rotor blades over the inboard section integrates Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs) on the lower surface of the blade aft of the leading-edge spar was shown to enhance the rotor’s performance in hot conditions40.

The concept of laminate compliance mechanisms in morphing aircraft has been progressively developed across several studies. Aerostructural optimization was employed to design a tailed morphing wing, with performance validated through wind tunnel and flight testing41. This approach was extended to a tailless aircraft, where the planform, aero-structural layout, and flight control were optimized for enhanced adaptability42. Subsequently, concurrent aero-structural optimization of a camber-morphing flying wing was conducted, integrating structural and wind tunnel testing to refine the design43. The control authority of a similar flying wing was then investigated using conventional actuators, highlighting practical implementation aspects44. This progression was culminated in a comprehensive framework established for the concurrent design of structural, aerodynamic, and control systems for a tailless morphing wing tailored to airborne wind energy missions45.

Applying bistable mechanisms in morphing wings offers several key advantages, enabling UAVs to efficiently switch between two stable configurations31,46,47,48. This adaptability facilitates rapid changes in aerodynamic properties for various flight conditions, storing potential energy for release during transitions, and reducing the need for continuous energy input. Bistable mechanism designs can be lightweight and compact, which is crucial for UAVs, where weight directly impacts flight performance, including maneuverability and payload capacity. For instance, thin unsymmetric laminates exhibit mechanical bistability, enabling them to achieve substantial deflections between stable equilibrium positions with minimal energy input49. A bistable laminated composite structure facilitates camber morphing in airfoils50. While early designs necessitated stiffeners or locking mechanisms due to compliance limitations, potentially negatively impacting weight and performance, recent advancements have demonstrated that optimized designs and actuation strategies can overcome these challenges. Effective configuration control of wing-like bistable composite laminate under aerodynamic loads has been demonstrated without the need for mechanical locking mechanisms51. More recently, a topology-optimized multistable morphing wing section with selective stiffness, utilizing carbon-reinforced laminate, has been developed and experimentally validated, achieving stable aerodynamic shape control without additional reinforcements52. Cosine-profiled bistable arches, designed to reduce peak stresses in morphing wings, can be used individually or in multistable honeycomb structures53. Morphing airfoil designs utilizing compliant mechanisms for shape alteration through a single input force or torque have been demonstrated, with this single actuation input affecting both leading and trailing sections54. Although bistable mechanisms in helicopter rotor blades save energy, they face challenges with adaptability, comprehensive control, and sustained shape maintenance55,56. Despite some of the challenges, a topology-optimized, hyperelastic material-based camber morphing mechanism for bistable airfoils surpasses traditional actuation in efficiency57.

Most existing bistable morphing wing concepts rely on distributed translational degrees of freedom, which, when combined, can enable more complex motion profiles20,31,38,47,48. However, distinct rotational motion—and bistability—would centralize and substantially reduce the size and consequently the weight of integrated shape-morphing mechanisms, particularly for features that specifically require rotation, such as flaps. Despite its potential, distinct rotational bistability has not yet been integrated, as the limited existing options for such elements are generally unsuitable for morphing wings due to their high design complexity, asymmetric potential energy landscape, or restricted load-bearing capacity58,59,60,61,62. For instance, one-dimensional beam or truss-based elements exhibit lower potential energy barriers than plate geometries, while the absence of pre-stress results in a less distinct energy well, and fully 3D-printed elements currently cannot achieve symmetric bistability60.

Here, we introduce a new class of bistable torsional elements that take advantage of the post-buckling concept, utilizing a single, localized point of rotation to achieve purely rotational morphing, capable of maintaining 2n unique, stable aerodynamic conditions, where n = 2 represents the number of integrated bistable elements in our exemplary UAV airfoil. This concept uniquely enables substantial angular rotation tailored to morphing wings, and shape changes require minimal and brief energy pulses to initiate a stable shape change. To prove this concept, we will demonstrate aerodynamic performance as a function of shape adaptation with zero held energy and present validation data, including experimental measurements of displacement-shape and aerodynamic loads.

Results

Rotational bistable mechanism design

Energy consumption in UAVs is crucial for mission duration and operational efficiency. Traditional UAV designs with fixed airfoil profiles typically optimize for one flight condition or average over several combined flight regimes, whereas active actuation systems for morphing wings require additional actuators that draw energy over time in deformed shapes, in exchange for improved aerodynamic performance and efficiency. In contrast, our proposed design incorporates bistable morphing mechanisms into UAVs, which only require energy during the initial shape change. This approach substantially enhances both aerodynamic performance and energy efficiency, facilitating more agile and fuel-efficient flight, longer mission duration, and broader operational ranges. Fig. 1A illustrates different flight regimes along a schematic flight path. A qualitative comparison of energy consumption shows that traditional UAVs, and those with active actuation systems, require substantial energy use over time for actuation during various flight regimes. UAVs equipped with bistable morphing mechanisms eliminate the need for continuous energy input and demonstrate considerably lower energy consumption, underscoring the importance and superiority of energy-saving technologies in UAV design (Fig. 1B). A representative application of our multistable morphing wing concept comprises a central element affixed to a UAV body, serving as the reference plane (Fig. 1C). This integration mirrors the central wing box design along with the use of slats and flaps commonly seen on large passenger aircraft. We utilize integrated rotational bistable mechanisms to camber morph both the leading edge (LE), akin to a slat, and the trailing edge (TE), similar to a flap. This design allows the wing to lock into a specific degree of rotation without requiring additional power to maintain its position during flight (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). The initial configuration of the wing is shown as a solid structure; the morphed states of the LE and TE are depicted as wireframes, indicating the actuation angles αLE and αTE, respectively.

A An exemplary flight path of q drone showing different flight regimes. B A schematic morphing energy consumption comparison for a UAV with bistable morphing wings (this work) and a UAV with a traditional morphing system requiring a constant energy supply. C A schematic 3D model of an uncrewed aerial vehicle. D The proposed morphing wing with two bistable mechanisms consists of a leading edge (LE) morphing section, a fixed section, and a trailing edge (TE) morphing section. Both LE and TE sections can be morphed independently. The geometric design parameters of the bistable parts can tune the morphing angles for LE and TE. (E, i) Unassembled internal part, (ii) first stable state after assembly, (iii) and second stable state. F Elastic potential energy diagram from the finite element (FE) analysis. Two stable states have minimum potential energy at αLE = 0° and 17.4° for LE and at αLE = 0° and 17.5° for TE. G FE and experimental results depicting the torque-rotation graph for the leading edge and trailing edges in deflected and recovered states. Scale bars=10 mm.

The rotational bistable elements consist of distinct internal and external components (Fig. 1E). The internal component features six slender plates (fins) arranged radially around a central circle—the rotational axis (Fig. 1Ei). The fins’ opposite ends are connected to an external frame, forming a honeycomb-shaped module. The geometric properties of the fins are designed such that the ratio of fin thickness to fin width or height remains below 0.1, allowing them to be treated as thin-walled structures63,64,65. During assembly, the internal plates are elastically and unidirectionally buckled by freely rotating the axis, while the frame retains its shape, establishing one of two symmetric stable states (Fig. 1Eii). Applying torque in the opposite direction of the buckled walls via a connecting shaft in the square hole results in the second stable state (Fig. 1Eiii). The rotation degree is adjustable by altering wall lengths, and the required torque is determined by wall thickness and material properties. Finite element analysis (FEA), corroborated by experimental data, estimated the bistable hinge’s energy barrier and stable states by modeling elastic potential energy (Fig. 1F). The LE hinges have stable states at αLE = 0° and 17.4°, and the TE hinges at αTE = 0° and 17.5°. The extremes at both ends of this data represent the energy wells. Although the potential energy outside this range is not explicitly depicted, it is substantially higher, ensuring the system’s stability within the operational region. The energy barrier is crucial for the design, providing the stiffness needed to withstand forces on the wing. Switching between stable states involves overcoming the elastic energy barrier through actuators, which remain active only during the transition. The torque for rotation, obtained from both experimental result and FEA simulation (Fig. 1G), is about 1 N ⋅ m (Supplementary Table 1). Once the barrier’s peak is exceeded, the structure shifts automatically to the opposite stable state without further energy input. Exceeding the energy minima through rotation causes elastic deformation, stabilizing the states within narrow ranges, and preventing backlash in either direction.

The LE requires slightly higher strain energy than TE (0.0133 J and 0.0123 J, respectively) and, consequently, a higher torque value (1.01 N.m and 0.91 N.m) to deflect (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, recovering from the deflected position back to the baseline produced higher strain energy (0.0133 J and 0.0118 J) and torque (0.99 N.m and 0.75 N.m) for the LE hinge compared to the TE one (Supplementary Table 1). The small differences between strain energies and torques for the deflected and recovered states of each hinge were due to the slight difference in geometry between the two stable states concerning the instability point. Specifically, the LE deflected after approximately 8.5° of downwards rotation, but over 11° upwards rotation was required for recovery. The TE exhibited a less pronounced, asymmetry in the torque/total strain energy required for transition due to geometric effects, requiring 9.5° rotation for deployment and 12° rotation for recovery (Fig. 1G). Notably, both experimental results and simulations demonstrated that the LE required higher torque and strain energy for both deflection and recovery compared to the TE (Supplementary Table 1). This higher torque requirement was expected given the LE bistable elements were larger than the TE bistable elements (32 mm and 28 mm, respectively), specifically due to the airfoil shape. Conversely, due to the volumetric considerations, the total strain energy to deflect was similar for the deployment of the LE and TE.

By altering the geometric and material characteristics of the bistable components, the torque required to transition between stable states, both for LE and TE, as well as the degree of rotation, can be precisely modulated to desired levels. The elastic modulus of the material directly influences the critical buckling load. Using a stiffer material with a higher elastic modulus results in a higher torque for rotation. Additionally, the moment of inertia and the length of the fins play a crucial role in determining the buckling load. Hence, for a selected material, by controlling the length of the fins (Fig. 2A–C), thickness (Fig. 2D), width (Fig. 2E), and number of fins (Fig. 2F), we can achieve the desierd torque capacity of the bistable element. The amount of rotation at both the LE and TE can be correlated with the curvature of the buckled parts, which is directly proportional to the length of the fins. Using slightly longer bistable beams within the fixed circumference of the middle section enables larger rotations and higher torques (Fig. 2C). The torque magnitude can be controlled by varying the fin thickness (Fig. 2D) or fin width (Fig. 2E) while maintaining the angular displacement constant. Losing fins during operation will reduce the device’s maximum torque and rotational capabilities, but the mechanisms continue to function effectively under lower loads (Fig. 2F).

Energy landscape and wing structure define flight envelope

The NACA 4412 airfoil was chosen as the reference wing profile for its well-understood aerodynamic properties and adaptability (Fig. 3A). Featuring a thickness-to-chord ratio of 12% along with 4% camber peaking around 40% of the chord, it provides a balanced lift-to-drag ratio suitable for a variety of applications, including general aviation and UAVs. Its nearly flat bottom surface makes the construction of experimental models convenient, enabling easier investigation of LE and TE morphing effects. Importantly, while the NACA 4412 was chosen for this study, the bistable rotational mechanisms can be applied to any airfoil with sufficient thickness, offering versatility for future applications.

Two bistable systems were incorporated, dedicated to morphing the LE and the TE, positioned at 25% and 50% of the chord length, respectively. The external parts of bistable mechanisms were embedded in the fixed middle section, with the internal bistable parts incorporated into the leading and trailing edges. This integration along the chord results in a multistable configuration with four distinct stable states: the initial undeformed state, LE deflected, both LE and TE deflected (LE-TE), and TE deflected states (Fig. 3A). Importantly, scaling up the design space of the 2D FEA of individual elements to entire 3D airfoils provided good agreement with the experimental parts concerning deformation angles and the overall deformed airfoil shape (Fig. 3B).

Aerodynamic analysis was performed using a 2D-panel method with XFLR5, a low-Reynolds number aircraft aerodynamic analysis tool. This analysis generated coefficient of pressure distributions over the suction surface (upper surface) and pressure surface (lower surface) of the wing in each morphing configuration for angles of attack (AoA) ranging from − 10° to 20°. In this study, the AoA is defined as the angle between the middle section of the wing segments and the incoming airflow. Torques on the LE hinge and TE hinge were calculated as a sum of moments generated by each discrete panel, j, in the respective active airfoil sections,

where N is the total number of panels on the active section in question, Cpj and ℓj are the pressure coefficient and panel length (normalized by chord length), used to scale the moment vector calculated with the unit vector normal to the panel, \({\hat{n}}_{j}\), and position vector between the hinge (LE or TE) and panel, \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{j}\) (normalized by chord length). Moment directions were defined as positive (red) when applied in the direction of camber deflection, and negative (blue) when applied in the direction of recovery (Fig. 3E). The summed moment was dimensionalized by the dynamic pressure, q, which is proportional to the flow velocity, U, and the wing area, S. Moments were calculated at each AoA for flow velocities ranging from 0 ms−1 to 30 ms−1 (Fig. 3F, G). The activation torque of 1 N ⋅ m for the bistable mechanism was exceeded by negative (blue) and positive (red) pitching moments at different AoA-velocity combinations for each morphing configuration. This created a frontier of operation (highlighted by a solid line) for which our wing can maintain a morphing configuration without powered actuation. For example, when the TE is deflected during flight near an AoA of 5°, the aerodynamic loading will restore the TE to its original state at flow speeds above 15 ms−1 (Fig. 3F-LE).

The operational space in which the bistable wing can fly without aerodynamically induced shape change was largely dependent on hinge position and morphing configuration. In non-deployed configurations, hinge stiffness must withstand the associated positive torques (red) to prevent unwanted deployment, whereas deployed configurations must withstand negative torques (blue). Within the tested flight envelop, the LE hinge was only subject to aerodynamically induced deployments at negative angles of attack, and aerodynamically induced recoveries at positive angles of attack (Fig. 3F). Notably, producing an additional TE shape change (LE-TE) shifted the operational frontier toward smaller angles of attack, reducing the operational space for the LE hinge. Regarding the TE hinge, aerodynamically induced deployments were not found within the considered flight envelope; however, aerodynamically induced recovery limited the operational velocity during the TE deflected configuration for all considered AoAs (Fig. 3G). Interestingly, including an additional LE deflection (LE-TE) increased the operational space, specifically at negative AoAs.

Aerodynamic morphing airfoil performance

Wind tunnel tests were conducted to validate the operational principles of the multistable morphing wing (Fig. 4, Supplementary Movies 3 to 5). These tests aimed to measure lift forces and displacement patterns across the span and the chord at various speeds and AoAs. The testing procedure in the wind tunnel was divided into two phases. Initially, the specimen underwent testing at varying velocities ranging from 0 to 17.5 ms−1, in 2.5 ms−1 intervals, while maintaining a constant AoA of 5°. Subsequently, the load cell was attached beneath the aerodynamic splitter plate, and aerodynamic force data were collected at a constant velocity of 5 ms−1 for a wide range of AoAs, from −5° to 20°, in 2.5° increments. Each test was replicated four times. A Digital Image Correlation (DIC) system was utilized to capture the wing’s deformation shape. Chordwise and spanwise surface cross-sections were determined based on the out-of-plane displacement (Z coordinate), at 50% of the span, and 40% of the chord, respectively (Fig. 4F).

A Schematics of the model inside the tunnel section. B, C The fully assembled wing consists of two actuation segments, one multistable segment, and two simple segments. A load cell is connected to the bottom part of the wing. The whole sample is ready to be mounted into the wind tunnel section, the attached load cell is located beneath the aerodynamic splitter plate. D Wind tunnel facility. E The sample is located inside the wind tunnel test section (Supplementary Movie 5); two high-speed digital video cameras are located in front of the sample perpendicular to the top surface of the wing to capture the DIC data. F DIC-captured image of the sample inside the wind tunnel test section. G Actuation sequence for LE and TE in the wind tunnel test section, with State 0 representing the first stable configuration and State 1 indicating the second.

The DIC images and displacement graphs (Fig. 5) illustrate the span shapes (Supplementary Movie 6) and chord shapes (Supplementary Movie 7) for various configurations at an AoA of 5°, with wind tunnel speeds varying from 2.5 ms−1 to 17.5 ms−1. The maximum tip displacement (100% span) occurred at the highest speed (17.5 ms−1) for the TE configuration (Fig. 5D), which exhibits the highest lift force compared to other configurations. The chord displacements exhibit consistent LE and TE positions for each configuration across different speeds, indicating that the bistable mechanism can maintain shape even under aerodynamic loading. However, at a speed of 17.5 ms−1, the servo motors were unable to actuate the trailing edge, suggesting that the combined torque from the bistable mechanism and the aerodynamic force exceeded the servo motor’s capacity and that servo motors capable of greater torque may be required for this specific configuration to achieve and maintain configurations at higher air speeds (Fig. 5C). The DIC counters (Fig. 5C, D) indicate a slight twist in the trailing edge. This effect can be attributed to the cantilever nature of the setup, where the sample is fixed at a single point on one end through the load cell and is free at the other end (Fig. 4A, C). Due to this configuration, the deformation gradient is expected to vary along the length of the sample, with a bit larger deformation occurring closer to the free end. While the observed twist is minor, measuring approximately 2.5% of the chord length, it is sufficient to be captured in the DIC contour images. Additionally, the placement of the multistable segment influences the deformation pattern. In this setup, a single multistable segment is positioned near the left end. Introducing a second segment symmetrically on the opposite end would increase stability and minimize the twist in real-world applications.

DIC captured image of the sample inside the wind tunnel test section (Supplementary Movie 6 and 7) with span and chord displacement graphs at the speed of 2.5 to 17.5 ms−1 and 5° AoA, for undeformed sample (A), leading edge deflected (B), leading and trailing edge deflected (C), and trailing edge deflected (D).

Span displacements of the wing (Fig. 6A) and corresponding chord displacements (Fig. 6B) for all configurations were derived from the DIC data at a speed of 5 ms−1 across all AoAs. Tip displacements (Fig. 6A 100% span) ranged from 0 to 3 mm, reflecting the lift force increase with the rising of AoA. The chord displacement graphs (Fig. 6B) illustrate the leading and trailing edge movements, when actuated, showing a relatively consistent position even at varying AoAs. This indicated that all stable states can be maintained without the need for constant energy input. The trailing edge displacement becomes more pronounced, on the order of 5-10 mm, as the AoA–and thus lift–increases, slightly bending the model, but not forcing the bistable mechanism back to its baseline position.

A Span displacement graphs and B chord displacement graphs for all AoAs at the speed of 5 ms−1. C Coefficient of lift (CL) vs Angle of Attack (AoA) for all stable states at the speed of 5 ms−1. D Required power and E morphing energy consumption to actuate the bistable morphing system (red line) and maintain the morphing state in the traditional morphing system (blue line).

The lift on the model in all four states was recorded at a velocity of 5 ms−1 (Re ≈ 1.2 × 105) to compare against the XFLR5 numerical models (Fig. 6C). The 3D XFLR5 model accurately predicted the lift measured in the wind tunnel for the Baseline and LE morphing configurations, but it was less accurate for the LE-TE and TE configurations. The 2D XFLR5 model, adjusted for aspect ratio, provided a more accurate estimate of the challenging LE-TE and TE configurations, thus it was selected for hinge moment calculations. A higher fidelity STAR-CCM+ model offered further validation for the XFLR5 2D panel method (Fig. 6C). As expected, at this airspeed, the lift coefficient in relation to the angle of attack demonstrated an almost linear increase (Fig. 6C). In all four states, a noticeable variation in the coefficient of lift was observed within the AoA range of 10° to 15°. The results suggest that the TE deflection has a more pronounced effect on the lift coefficient when compared to the leading edge. At an AoA of 0°, the coefficient of lift (CL) was approximately 0.25 in the original undeformed state. Deflecting the leading edge decreased the CL to 0, while deflecting the trailing edge increased the CL to 0.75. In the LE-TE deflected state, the CL was approximately 0.35.

To quantify the energy savings associated with the proposed mechanism, we conducted power consumption tests. In traditional morphing mode, maintaining the morphed shape during flight requires a constant torque to hold the leading and trailing edges in place, with the actuator remaining active throughout the respective segment. In contrast, our multistable design uses the same actuation mechanism only to rotate the parts into position; once they lock, the actuator is disengaged until another switch is needed. Results indicate a substantial reduction in power requirements (Fig. 6D) and approximately 80% energy savings for equivalent test sequences in the wind tunnel (Fig. 6E). It is important to note that the power consumption shown in the graph represents only the energy required for the morphing mechanism and not the overall power for the entire aircraft. The snap-through buckling behavior of rotational bistable elements is instrumental in eliminating the need for continuous energy input to maintain desired wing shapes.

Conclusion

We have introduced a new class of bistable rotating elements and applied them to enable angular motion for chordwise morphing applications in UAV wings. By leveraging the principles of geometric nonlinearity, our design systematically generates sets of bistable geometries that capitalize on linear-elastic deformation. The suggested multistable morphing wing can be mechanically tuned to achieve targeted torque or degrees of rotation in leading and trailing edges (Fig. 2C–F). This facilitates substantial, repeatable, and reversible changes in the wing’s airfoil shape. The developed proof-of-concept prototype was experimentally tested to verify its efficiency across diverse flight conditions and validate the simulations. FEA and aerodynamic analysis were conducted to validate the design and integration. For instance, wind tunnel experiments on the prototype morphing wing, covering velocities from 2.5 ms−1 to 17.5 ms−1 and angles of attack from − 5° to 20°, demonstrate the mechanical reliability of the multistable rotational morphing system, where the occurrence of snap-through buckling within the rotational bistable elements eliminates the need for continuous energy to maintain the desired wing shape during specific maneuvers. This conserves substantial fuel or battery usage during flight and contributes to the overall weight reduction of UAVs (Fig. 6D).

To achieve further weight savings, airfoil shape changes could be triggered by brief and specifically designed flight maneuvers that exceed the peak transition load in the bistable elements, thereby not affecting general flight regimes and eliminating the need for dedicated actuators. Future work might also explore alternative actuation mechanisms integrated at the materials level, for instance, by utilizing electroactive or magnetic materials such as shape memory alloys (SMAs). These materials have the potential to further reduce weight or enable more complex shape changes by incorporating additional bistable elements. Although we implemented our proposed elements in a small UAV, typically a low-altitude, low-speed aerial vehicle, future work could explore its application in larger-scale and high-lift aircraft, drawing on existing studies that utilize morphing droop noses66.

Overall, the proposed mechanism offers several key advantages for morphing wing applications: its simplicity arises from fewer elements and uniform dimensions, streamlining design, fabrication, and modular integration, such as in honeycomb lattices. Stability is enhanced by using thin-walled structures instead of beams or trusses, creating a more favorable energy landscape with narrow stable states and tunable barriers. Robustness improves as outer hinges allow free rotation, reducing local stress by eliminating the need for beams to double-act as hinges. Additionally, free rotation at the hinges ensures near-perfect symmetry between bistable states, which is not currently possible in fully 3D-printed solutions. The mechanism maintains substantial tunability without altering outer dimensions, simplifying design and, again, enhancing integration into existing structures. Lastly, these bistable structures add only 1.91% to the total wing weight. Given that the current design has not been optimized for weight reduction, this presents a promising opportunity for future work.

The concept of rotational bistability could have widespread applications in various fields beyond aerospace engineering. These include grippers or manipulators in robotics and automation, multistable hinges in foldable or flexible consumer electronics like smartphones or laptops, adjustable stability or flexibility in prosthetics and orthotics, bistable windows, facades, louvers or other components that respond to environmental conditions in construction and architecture, among many other potential uses.

Methods

Finite element analysis

For the structural analysis, the complete multistable wing structure was simulated using Abaqus 2023 and was comprised of three distinct parts: LE, middle section, and TE. Each segment was modeled using C3D10 elements, with approximately 70,000 elements for each of the LE and TE segments and approximately 141,000 elements in the middle segment. Note that the highest element density is in the bistable arms for the LE and TE segments, as well as the circular features connecting the LE / TE segments to the middle segment. All segments were modeled using a simple linear, elastic constitutive model with an elastic modulus of 2 GPa, a Poisson’s ratio of 0.36, and a density of 1.2 gcm−3, derived from PLA material properties.

The simulation of the bistable system consisted of four steps. In the first step, the tips of the bistable beams of the LE and TE segments are bent from their initially straight shape into the circular slots on the middle segment (representative of going from Fig. 1.C.i to Fig. 1.C.ii). For this first step, the sides of the LE, middle, and TE segments are fully constrained such that the only motion is that of the bistable beams. After this initial bistable beam deformation step, the tips of the bistable elements of the LE and TE are constrained within the circular features of the middle segment, but the sides of the LE and TE are released such that the LE and TE can move in response to rotation of the central rotational axis of the LE and TE. In step two, the central rotational axis of the LE and TE is sequentially rotated from the original, un-actuated position to the actuated position. Hard contact interactions are imposed between the members of the LE and TE which connect to the hub of the bistable elements and the surfaces of the middle segment, ensuring that no penetration occurs when transitioning between stable states. Step three acts as an intermediate relaxation step wherein the rotational boundary conditions are removed, thereby validating that the second stable shape for both the LE and TE has been reached. Step four reverses the LE and TE actuation by sequentially rotating the respective central axes back to the original position, thereby recovering the original NACA 4412 wing profile. It should be noted that step one is simulated using a general static solver. In contrast, steps two through four are simulated using the dynamic, quasi-static solver due to the dynamic nature of the bistable elements during snap-through. All steps assume non-linear geometry.

System design

The complete wing structure comprises one or more multistable segments, actuation segments, and simple segments. In this study, a single multistable segment has been employed. However, depending on factors such as the desired maximum torque and the capacity of the servo motors, it is feasible to utilize two or more multistable segments similar to the one depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. This figure provides a visual representation of these components and outlines the assembly procedure, which contains a comprehensive 3D model and its primary segments (Supplementary Fig. 1 A-D), the corresponding 3D printed segments (Supplementary Fig. 1E-H), and the fully unassembled 3D-printed parts for each primary segment (Supplementary Fig. 1 IF-IH). As mentioned previously, the proposed rotational multistable segment can provide four stable states along the wing chord (Supplementary Fig. 1C, G). The dimensions of the multistable segment, which was used in this study, are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2. These dimensions can be adjusted to accommodate various airfoils, torque levels, and degrees of rotation for morphing components.

A suitable actuation system is essential to overcome the bistable torques along with the torque induced by aerodynamic forces. The actuation segments, positioned at both ends of the span, incorporate two servo motors for each LE and TE. Supplementary Fig. 1(D, H, and IH) represents the 3D model, 3D printed parts, and unassembled components of the actuation segment, respectively. The LE and TE deflect motors function independently, however, each pair of servo motors (LE or TE) along the span rotate simultaneously in opposite directions. Small torque adapters and two square steel bars are utilized to transfer the generated torque from servo motors to bistable segments (Supplementary Fig. 1IH). To maintain an appropriate aspect ratio of the wing’s chord and span, simple segments are positioned between the other functional segments. These no functionality and serve as a filler component (Supplementary Fig. 1B, F, and IF). The entire system is interconnected using seven square steel bars, forming an integrated morphing wing structure.

Based on the width dimensions of each segment (Supplementary Fig. 1A), the bistable section occupies only 8% of the total wing span. The total weight of the wing—excluding actuators—is 1575.75 grams, of which the bistable components account for 30.07 grams, representing approximately 1.91%. This indicates that the bistable parts occupy only a small portion of the airfoil in terms of both size and weight.

Wind tunnel test

The tests were carried out in the DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory (ARL) wind tunnel facility. Additional facility details can be found in67. The wind tunnel test model, made with PLA material, was 3D printed using a Prusa MK3 FDM 3D printer and has a total span of 420 mm and a chord length of 336 mm. An aerodynamic splitter plate was attached to the left side of the wing and an ATI Nano-25 load cell was connected to the other side of the plate at 40 percent of the chord length (Fig. 4A). The fully assembled morphing wing (Fig. 4B, C) was fixed vertically via the load cell to the wind tunnel turn-table on the floor of the test section (Fig. 4D, E). The actuation system within the model was controlled by an operation board, which was placed outside the test section. The operational board comprises a PCA9685 servo shield stacked on an Arduino Uno R3, enabling the control of four servo motors. An actuation sequence was used, which defined 10-second intervals for each morphing configuration (original undeformed state, LE deflected, LE-TE deflected, TE deflected, and back to the original state - Fig. 4G). Three repeated trials were conducted, collecting aerodynamic force data at a measurement speed of 1 kHz. The force data was collected using a NI-DAQ system and LabVIEW software. Voltage measurements from the load cell were converted to forces using the manufacturer-supplied calibration matrix, which were then converted to lift coefficient using \({C}_{L}=L/(\frac{1}{2}\rho {V}^{2}S)\), where ρ is air density (1.225 kg/m3) and S is the wing area. Uncertainty in the lift coefficient was calculated as a 95% confidence interval using standard deviation and was typically on the order of CL ≈ 0.03.

An in-situ three-dimensional digital image correlation (DIC) system was employed to capture the in-plane and out-of-plane displacements, as well as the initial positions of the morphing wing model within the wind tunnel. Two Point Grey Research 5 MP video cameras (GS3-U3-50S5M-C) were mounted in stereo, aligned with the wing span spaced approximately 1000 mm from the wing at a tilt angle of 30° (Fig. 4E) with respect to each other. Cameras were focused on mid-chord and mid-span throughout the testing. The recorded images were correlated using VIC3D software which measured displacement field data, the deformed shape of the wing, in the specified area of interest. The center point (35–50% chord) movement of the model due to generated lift across the not moving portion of the model was removed from the chordwise data to show relative model displacement as a function of AoA and wind speed to determine if the leading edge and trailing edge positions were maintained by the bistable mechanisms.

Tunability test

To demonstrate the tunability of the proposed rotational bistable element, various experiments were conducted with different geometric configurations. The effects of altering internal and external dimensions (Fig. 2A) were extensively investigated with the experimental setup and various samples characterized in Fig. 2B.

Initially, the fin length (L) was varied while maintaining all other dimensions constant. Results revealed that a slight increase of 0.3% in fin length led to a 50% increase in torque, from 0.86 N ⋅ m to 1.33 N ⋅ m. Similarly, the degree of rotation increased from 13.13° to 17.41° (Fig. 2C).

Subsequently, fin thickness was modified while keeping other dimensions fixed. The degree of rotation remained unchanged, but torque amplitude increased. When fin thickness was increased from 0.8 mm to 0.9 mm and then to 1.0 mm, torque increased from 1.33 N ⋅ m to 1.60 N ⋅ m and then to 1.93 N ⋅ m, respectively (Fig. 2D).

Adjusting fin width had a minor impact on the degree of rotation but substantially affected torque amplitude. Increasing fin width from 10 mm to 25 mm in 5 mm increments resulted in torque increases from 0.46 N ⋅ m to 0.75 N ⋅ m, 1.04 N ⋅ m, and 1.33 N ⋅ m, respectively (Fig. 2E).

Finally, the number of fins was varied to simulate potential damage. Reducing the number of fins decreased torque from 1.33 N ⋅ m to 0.89 N ⋅ m, representing a 33% reduction in operational capacity. The device remained bistable, but the degree of rotation decreased from 17.41° to 15.82° (Fig. 2F).

Power consumption test

To compare the energy consumption between our proposed design and traditional morphing approaches, we used the same wing structure but in traditional morphing mode, eliminating the bistable modulus by replacing segment C in the multistable wing with segment B (Supplementary Fig. 1A, E). This means that, to maintain the morphed shape during flight in a traditional morphing wing, a constant torque must be applied to keep the leading and trailing edges in their morphed positions, as determined by the wind tunnel tests. We utilized the same actuator in both cases. The key difference is that in our multistable design, the actuator only needs to rotate the parts; once locked in place, the actuator stops operating until another morphing state is required. In contrast, for the traditional morphing mechanism, the actuator must remain active throughout the flight to maintain the required torque and rotation. Voltage was applied using a power supply device, and the consumed current was measured (Kungber Power Supply - SPS1203). The power and energy consumption were calculated based on the input voltage and the measured current. The graphs in Fig. 6D, E illustrate these differences.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the relevant data are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file or from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Taylor, G. K., Carruthers, A. C., Hubel, T. Y. & Walker, S. M. Wing morphing in insects, birds and bats: mechanism and function. Morphing Aerospace vehicles and structures 11–40 (2012).

Dharmdas, A. et al. An Experimental and Simulation Study of the Active Camber Morphing Concept on Airfoils Using Bio-Inspired Structures. Biomimetics 8 (2023).

Kilian, L., Shahid, F., Zhao, J. S. & Nayeri, C. N. Bioinspired morphing wings: Mechanical design and wind tunnel experiments. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 17 (2022).

Harvey, C., Baliga, V. B., Goates, C. D., Hunsaker, D. F. & Inman, D. J. Gull-inspired joint-driven wing morphing allows adaptive longitudinal flight control. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 18 (2021).

Matloff, L. Y. et al. How flight feathers stick together to form a continuous morphing wing. Science 367, 293–297 (2020).

Xiao, K., Chen, Y., Jiang, W., Wang, C. & Zhao, L. Modeling, simulation and implementation of a bird-inspired morphing wing aircraf. In 2019 3rd International Conference on Robotics and Automation Sciences (ICRAS), 238–243 (IEEE, 2019).

Abdulrahim, M. & Lind, R. Flight testing and response characteristics of a variable gull-wing morphing aircraft. In Collection of Technical Papers - AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, vol. 3, 1664–1679 (2004).

Haughn, K. P., Gamble, L. L. & Inman, D. J. Horizontal planform morphing tail for an avian inspired uav using shape memory alloys. In Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, vol. 51951, V002T06A003 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2018).

Abdulrahim, M. Flight dynamics and control of an aircraft with segmented control surfaces. In AIAA Paper, 128 (2004).

Cadogan, D., Smith, T., Uhelsky, F. & Mackusick, M. Morphing inflatable wing development for compact package unmanned aerial vehicles. In 45th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics & Materials Conference, 1807 (2004).

Xie, C., Chen, Z. & An, C. Study on the aeroelastic response of a z-shaped folding wing during the morphing process. In AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum, 0849 (2022).

Guo, X., Wang, S., Qu, Y. & Cao, D. Nonlinear dynamics of z-shaped morphing wings in subsonic flow. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 119 (2021).

Wu, M., Shi, Z., Xiao, T. & Ang, H. Energy optimization and investigation for Z-shaped sun-tracking morphing-wing solar-powered UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 91, 1–11 (2019).

Bourdin, P., Gatto, A. & Friswell, M. The application of variable cant angle winglets for morphing aircraft control. In 24th AIAA applied aerodynamics conference, 3660 (2006).

Henry, T. C., Hrynuk, J. T., Del Colliano, A. & King, P. Wing strike reduction for small fixed wing uncrewed aerial vehicles. Aerospace Science and Technology 142 (2023).

Dimino, I. et al. Integrated design of a morphing winglet for active load control and alleviation of turboprop regional aircraft. Appl. Sci. 11, 2439 (2021).

Chen, X., Liu, J. & Li, Q. The smart morphing winglet driven by the piezoelectric macro fiber composite actuator. Aeronautical J. 126, 830–847 (2022).

Gandhi, F. & Anusonti-Inthra, P. Skin design studies for variable camber morphing airfoils. Smart Materials and Structures 17 (2008).

Yokozeki, T., Sugiura, A. & Hirano, Y. Development of variable camber morphing airfoil using corrugated structure. J. Aircr. 51, 1023–1029 (2014).

Kuder, I. K., Arrieta, A. F., Rist, M. & Ermanni, P. Aeroelastic response of a selectively compliant morphing aerofoil featuring integrated variable stiffness bi-stable laminates. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 27, 1949–1966 (2016).

Kuder, I. K., Fasel, U., Ermanni, P. & Arrieta, A. F. Concurrent design of a morphing aerofoil with variable stiffness bi-stable laminates. Smart Mater. Struct. 25, 115001 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Ge, W., Zhang, Z., Mo, X. & Zhang, Y. Design of compliant mechanism-based variable camber morphing wing with nonlinear large deformation. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 16 (2019).

Bashir, M., Longtin-Martel, S., Botez, R. M. & Wong, T. Aerodynamic design optimization of a morphing leading edge and trailing edge airfoil-application on the uas-s45. Appl. Sci. (Switz.) 11, 1–34 (2021).

Cheng, G., Ma, T., Yang, J., Chang, N. & Zhou, X. Design and experiment of a seamless morphing trailing edge. Aerospace 10 (2023).

Bishay, P. L., Burg, E., Akinwunmi, A., Phan, R. & Sepulveda, K. Development of a new span-morphing wing core design. Designs 3, 1–11 (2019).

Ajaj, R. M. & Jankee, G. K. The Transformer aircraft: a multimission unmanned aerial vehicle capable of symmetric and asymmetric span morphing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 76, 512–522 (2018).

Henry, T. C., Hrynuk, J. T. & Phillips, F. R. Assessment of 3D-printed span change structures applied to small unmanned aerial vehicles. Int. J. Micro Air Veh. 13 (2021).

Li, D. et al. A review of modelling and analysis of morphing wings. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 100, 46–62 (2018).

Ozel, C., Ozbek, E. & Ekici, S. A review on applications and effects of morphing wing technology on UAVs. Int. J. Aviat. Sci. Technol. vm01, 30–40 (2020).

Barbarino, S., Bilgen, O., Ajaj, R. M., Friswell, M. I. & Inman, D. J. A review of morphing aircraft. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 22, 823–877 (2011).

Daynes, S., Weaver, P. & Potter, K. Aeroelastic study of bistable composite airfoils. J. Aircr. 46, 2169–2174 (2009).

Sanders, B., Eastep, F. & Forster, E. Aerodynamic and aeroelastic characteristics of wings with conformal control surfaces for morphing aircraft. J. Aircr. 40, 94–99 (2003).

Woods, B. K., Bilgen, O. & Friswell, M. I. Wind tunnel testing of the fish bone active camber morphing concept. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 25, 772–785 (2014).

Fincham, J. & Friswell, M. Aerodynamic optimisation of a camber morphing aerofoil. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 43, 245–255 (2015).

Woods, B. K. S. & Friswell, M. I. Preliminary investigation of a fishbone active camber concept. In Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, Vol. 45103, 555–563 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2012).

Pankonien, A. & Inman, D. J. Experimental testing of spanwise morphing trailing edge concept. In Active and Passive Smart Structures and Integrated Systems 2013, vol. 8688, 352–364 (SPIE, 2013).

Haughn, K. P., Gamble, L. L. & Inman, D. J. Deep reinforcement learning achieves multifunctional morphing airfoil control. J. Composite Mater. 57, 721–736 (2023).

Vos, R. & Barrett, R. Post-buckled precompressed techniques in adaptive aerostructures: an overview. J. Mech. Des. 132, 031004 (2010).

Zhang, J. et al. Aeroelastic model and analysis of an active camber morphing wing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 111, 106534 (2021).

DiPalma, M. & Gandhi, F. Autonomous camber morphing of a helicopter rotor blade with temperature change using integrated shape memory alloys. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 32, 499–515 (2021).

Molinari, G., Arrieta, A. F., Guillaume, M. & Ermanni, P. Aerostructural performance of distributed compliance morphing wings: wind tunnel and flight testing. AIAA J. 54, 3859–3871 (2016).

Molinari, G., Arrieta, A. F. & Ermanni, P. Planform, aero-structural and flight control optimization for tailless morphing aircraft. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 29, 3847–3872 (2018).

Keidel, D., Molinari, G. & Ermanni, P. Aero-structural optimization and analysis of a camber-morphing flying wing: Structural and wind tunnel testing. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 30, 908–923 (2019).

Keidel, D., Fasel, U. & Ermanni, P. Control authority of a camber morphing flying wing. J. Aircr. 57, 603–614 (2020).

Fasel, U., Tiso, P., Keidel, D. & Ermanni, P. Concurrent design and flight mission optimization of morphing airborne wind energy wings. AIAA J. 59, 1254–1268 (2021).

Chen, T., Müller, J. & Shea, K. Design and fabrication of a bistable unit actuator with multi-material additive manufacturing (2016).

Vos, R., Barrett, R., de Breuker, R. & Tiso, P. Post-buckled precompressed elements: a new class of control actuators for morphing wing uavs. Smart Mater. Struct. 16, 919 (2007).

Haldar, A., Jansen, E., Hofmeister, B., Bruns, M. & Rolfes, R. Analysis of novel morphing trailing edge flap actuated by multistable laminates. AIAA J. 58, 3149–3158 (2020).

Emam, S. A. & Inman, D. J. A Review on Bistable Composite Laminates for Morphing and Energy Harvesting. Appl. Mech. Rev. 67, 060803 (2015).

Diaconu, C. G., Weaver, P. M. & Mattioni, F. Concepts for morphing airfoil sections using bi-stable laminated composite structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 46, 689–701 (2008).

Arrieta, A. F., Bilgen, O., Friswell, M. I. & Ermanni, P. Modelling and configuration control of wing-shaped bi-stable piezoelectric composites under aerodynamic loads. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 29, 453–461 (2013).

Rivas-Padilla, J. R., Boston, D. M., Boddapati, K. & Arrieta, A. F. Aero-structural optimization and actuation analysis of a morphing wing section with embedded selectively stiff bistable elements. J. Composite Mater. 57, 737–757 (2023).

Pontecorvo, M. E., Barbarino, S., Murray, G. J. & Gandhi, F. S. Bistable arches for morphing applications. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 24, 274–286 (2013).

Saggere, L. & Kota, S. Static shape control of smart structures using compliant mechanisms. AIAA J. 37, 572–578 (1999).

Daynes, S. et al. On a bistable flap for an airfoil. In 50th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference 17th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference 11th AIAA No, 2103 (2009).

Mukherjee, A., Kumar, D., Ali, S. F. & Arockiarajan, A. Design and conception of a trailing edge morphing wing concept with bistable composite skin. In Han, J.-H. (ed.) Active and Passive Smart Structures and Integrated Systems XIV, vol. 11376, 113762K (SPIE, International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2020).

Bhattacharyya, A., Conlan-Smith, C. & James, K. A. Design of a bi-stable airfoil with tailored snap-through response using topology optimization. Computer-Aided Des. 108, 42–55 (2019).

Seyedkanani, A. & Akbarzadeh, A. Magnetically assisted rotationally multistable metamaterials for tunable energy trapping–dissipation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2207581 (2022).

Luharuka, R. & Hesketh, P. J. Design of fully compliant, in-plane rotary, bistable micromechanisms for mems applications. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 134, 231–238 (2007).

Jeong, H. Y. et al. 3d printing of twisting and rotational bistable structures with tuning elements. Sci. Rep. 9, 324 (2019).

Li, Y., Chandra, A., Dorn, C. J. & Lang, R. J. Reconfigurable surfaces employing linear-rotational and bistable-translational (lrbt) joints. Int. J. Solids Struct. 207, 22–41 (2020).

Pan, D., Xu, Y., Li, W. & Wu, Z. Novel rotational motion actuated beam-type multistable metastructures. Mater. Des. 224, 111309 (2022).

Timoshenko, S. & Woinowsky-Krieger, S. Theory of plates and shells (1959).

Ugural, A. C. Stresses in plates and shells (1999).

Ventsel, E., Krauthammer, T. & Carrera, E. Thin plates and shells: theory, analysis, and applications. Appl. Mech. Rev. 55, B72–B73 (2002).

Kintscher, M., Kirn, J., Storm, S. & Peter, F. Assessment of the saristu enhanced adaptive droop nose. In Smart Intelligent Aircraft Structures (SARISTU) Proceedings of the Final Project Conference, 113–140 (Springer, 2015).

Hrynuk, J. T., Olson, D., Stutz, C. & Jackson, J. Effects of turbulence on naca 0012 airfoil performance at low reynolds number. AIAA J. 62, 409–417 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Research was sponsored by DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory and was accomplished under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-22-2-0068. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Laboratory or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (K.B., T.C.H., K.P.T.H., F.R.P., J.T.H., and J.M.) designed research; K.B., T.C.H., K.P.T.H., and F.R.P. performed research; all authors (K.B., T.C.H., K.P.T.H., F.R.P., J.T.H., and J.M.) analyzed data; and all authors (K.B., T.C.H., K.P.T.H., F.R.P., J.T.H., and J.M.) wrote and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Toshiyuki Nakata and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Ros Daw].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barri, K., Haughn, K.P.T., Henry, T.C. et al. Rotational bistable mechanisms for morphing wings and beyond. Commun Eng 4, 164 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00495-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00495-2