Abstract

Roll-to-roll microcontact printing enables high-throughput production of flexible electronic devices by continuously transferring inks onto substrates via polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps. Traditional rectangular or cylindrical PDMS stamps yield uniform pattern sizes, limiting manufacturing versatility. This study introduces V-shaped PDMS stamps for variable pattern printing using a single stamp geometry. A physics-based deformation model was developed by combining finite element simulations and experiments to characterize the out-of-plane behavior of V-shaped PDMS under displacement. Leveraging this model, we implemented a neural network-based model predictive control system to precisely regulate vertical displacement and achieve desired pattern dimensions. Experimental results demonstrate that a single V-shaped PDMS stamp can reliably produce variable pattern sizes with high repeatability, improving the adaptability and process efficiency of roll-to-roll microcontact printing for flexible electronics manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

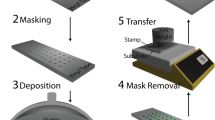

Microcontact printing (µCP)1, first introduced by Whitesides and colleagues in the 1990s, is a soft lithography technique that utilizes elastomeric stamps, typically made of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), to transfer molecular patterns onto diverse substrates through conformal contact2,3. Its simplicity, low cost, and compatibility with diverse materials have made µCP a widely adopted method in fields such as molecular electronics4, surface chemistry5,6,7, and biosensing8,9,10,11. The initial demonstrations of µCP employed rectangular PDMS stamps to pattern microscale gold features. Since then, most µCP studies and applications have used stamps that are vertically symmetrical, such as rectangular or cylindrical shapes12,13, whose deformation behaviors have been extensively characterized. For example, prior work14 has shown that for rectangular stamps, the size of the printed pattern remains constant regardless of the applied load, meaning that a single stamp can only produce one pattern size. Given that PDMS stamp fabrication is typically time-consuming, this constraint introduces complexity and delays in the development cycle for application-specific designs.

To address this limitation and enable more flexible printing capabilities, several strategies have been explored to allow a single PDMS stamp to generate variable pattern sizes. One approach involves multi-pass printing on the same substrate15; by rotating the stamp between successive printings, diverse shapes and sizes can be achieved. However, this method is hindered by limited alignment accuracy and is typically constrained to simple geometries, such as lines or arrays, which restricts its applicability for fabricating complex layouts in flexible electronics.

An alternative strategy involves altering the stamp geometry, with pyramidal PDMS stamps being the most widely studied16. These stamps enable variable pattern sizes by exploiting their deformation under different applied loads: increasing the load expands the tip contact area with the substrate, and vice versa. Initially developed to print dot-array patterns for protein patterning, pyramidal stamps are typically fabricated via photolithography and anisotropic etching. Subsequent studies have investigated their deformation behavior both experimentally and analytically. For instance, pyramidal PDMS stamps with a base size of 6 μm and height of 4.24 μm have been fabricated and tested under varying pressures17. The experimentally measured contact areas closely matched finite element analysis (FEA) predictions, validating their potential for tunable patterning. More recent work18 has incorporated dynamic modeling using the Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) contact mechanics framework to describe the deformation during printing. Despite these advances, pyramidal PDMS stamps are still limited to producing arrays of simple shapes (e.g., rectangular dots) and are therefore unsuitable for applications that require complex or arbitrary patterns.

Inspired by the concept of pyramidal PDMS stamps, which enable variable contact areas through controllable deformation, we explore an alternative geometry: the V-shaped PDMS stamp. This structure offers the potential for continuous modulation of contact area through its load-dependent out-of-plane deformation, making it a promising candidate for variable pattern printing in µCP. Unlike pyramidal PDMS stamps, which are typically limited to printing dot arrays or regular geometric patterns, the V-shaped PDMS stamp is capable of printing complex, arbitrarily shaped circuit layouts, thereby offering greater flexibility for advanced applications in flexible electronics.

Notably, V-shaped PDMS stamps have previously been used for µCP19, where a two-layer configuration was used: a 2–4 mm thick Sylgard 184 PDMS substrate supported a 30 μm thick hard PDMS (h-PDMS) film with a V-shaped surface profile. This study demonstrated sub-50 nm feature replication in a plate-to-plate µCP setup under a static load of ~20 g. However, the primary focus of that work was on achieving high-resolution static pattern transfer, rather than enabling continuous pattern size variation through controlled deformation. Furthermore, to date, there has been no systematic investigation into the deformation dynamics of V-shaped PDMS stamps, nor their application in roll-to-roll (R2R) µCP.

Therefore, we investigate the feasibility of using V-shaped PDMS stamps to achieve variable pattern sizes in R2R µCP as shown in Fig. 1a. The key to enabling tunable printing lies in precisely controlling the out-of-plane deformation of the stamp, which governs the contact area between the stamp and the substrate. In most existing R2R µCP systems, stable contact between the PDMS stamp and the substrate is typically maintained through force-based control schemes. Actuators, such as voice coils or stepper motors, regulate the vertical contact force, which is commonly measured by load cells due to the challenges associated with directly sensing interface pressure. For example, a flexure-guided R2R system achieved force variation control within 0.05 N using voice coil actuation20. Another system integrated air dampers and step motors in a hybrid configuration, maintaining force stability with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) below 0.25 N through load-cell-based feedback21.

a Illustration of the R2R µCP process with V-shaped PDMS stamps. b The proposed approach for displacement control of a V-shaped PDMS stamp in the R2R µCP process consists of offline and online stages. The offline stage comprises two independent processes. First, data from a single roller system and finite element analysis (FEA) simulations are used to model the displacement-contact area behavior of the V-shaped PDMS stamp. Second, a neural network-based model predictive control (MPC) system is trained offline to control stamp displacement. In the online stage, the physical model of displacement-contact area behavior is integrated with the neural network-based MPC to achieve high-precision control of the V-shaped PDMS stamp based on linewidth setpoints.

However, our findings reveal that even under precise force control, achieving a RMSE of 0.05 N, variations in printed pattern size still occur when using V-shaped PDMS stamps (Supplementary Fig. S1). A likely explanation for this variability lies in the limitations of load cell measurements: in addition to the actual contact force, load cells also capture vertical forces induced by web tension. Due to assembly imperfections and coupling effects, the controlled web tension can fluctuate within a range of ±1 N, effectively doubling the measured force and introducing unintended deformation in the PDMS stamp. Such deformation leads to inconsistent contact areas, undermining pattern transfer fidelity. To address this, we propose displacement-based control, which directly prescribes stamp deformation to ensure consistent contact areas.

In this work, we developed a physics-informed displacement control for V-shaped stamps in R2R µCP that maps stamp deformation to contact area, enabling variable linewidth printing from a single stamp as shown in Fig. 1b. We first derived a model that captures the relationship between the displacement of the V-shaped PDMS and the resulting contact area from physics-based FEA simulation and validated using a single roller experimental system. Subsequently, we implemented a neural network-based Model Predict Control (MPC) strategy to precisely regulate the displacement of V-shaped PDMS stamps during the R2R µCP process. Experimental results demonstrate that this displacement-driven control system achieves high precision in controlling pattern size and enables tunable printing with a single PDMS stamp geometry. These findings underscore the advantages of displacement-based control with V-shaped PDMS stamps in improving pattern size accuracy, process stability, and adaptability, advancing R2R μCP for next-generation flexible electronics manufacturing.

Methods

V-shaped PDMS Stamp Manufacturing

The analysis and results in this paper examine a V-shaped stamp with periodic lines on its surface, as shown in the cross-section depicted in Fig. 2a. The stamp features a larger rectangular base of height \(t\), integrated with a triangular feature defined by a width \(w\), and height \(h\). Ratio \(A\) represents the relationship between the width and height of the triangular feature. Figure 2b illustrates the PDMS fabrication workflow: mold fabrication, casting, and demolding. We first used SolidWorks to create the CAD drawing of the master mold for the PDMS. The master mold was then fabricated using a Profluidics P285D 3D printer. The use of Profluidics P285D reduces fabrication time and eliminates the need for a cleanroom. The real mold after 3D printing is shown in Fig. 2c. The Sylgard 184 PDMS mixture, prepared in a 10:1 weight ratio of elastomer base to curing agent, was mixed in a clean, dry container for 5 min, with the sides and bottom scraped to ensure uniformity. The mixture was then degassed in a vacuum chamber until no air bubbles remained. Subsequently, the degassed PDMS was poured into the prepared master mold and cured at 60 °C for 4 h. After curing, the V-shaped PDMS stamp was demolded. The resulting stamp is shown on Fig. 2d, with Fig. 2e illustrating a cross-sectional microscope image of the V-shaped PDMS structure.

Physics-informed deformation model derivation

Due to the inherent limitations of R2R μCP systems, the contact area between the PDMS stamp and the substrate cannot be directly monitored in situ. To address this, we developed a model to predict the contact area using indirect methods, deriving the physical relationship between applied displacement and contact area from FEA simulations and experimental data. This approach enables precise control of the contact area by adjusting displacement during the R2R μCP process. For the FEA simulation, a hyperelastic Neo-Hookean material model was used to represent the PDMS properties22. FEA simulations were conducted using Abaqus, a commercial software widely used for modeling nonlinear materials such as PDMS and complex geometries like V-shaped stamps23. We performed FEA across a range of aspect ratios, keeping the base width constant while varying the height to map the relationship between imposed displacement and contact area. A detailed description of the FEA modeling is provided in Supplementary Note 1. For the experimental part, we built a single-roller system to mimic the R2R µCP with the ability to monitor the contact area with a camera (Supplementary Fig. S3). The primary components of the single-roller system include a force measuring roller, a camera, a motion stage, and a glass plate. The glass plate was positioned beneath the print pattern and connected to a motion stage, emulating the continuous motion of the R2R system. The high-resolution camera is strategically positioned underneath the glass plate to capture detailed images of the contact area. The displacement was controlled by inserting different pieces of tape under the roller. The acquired contact area images (Supplementary Fig. S4) are processed using custom MATLAB code to calculate the contact width for each displacement setting.

R2R µCP with displacement sensors and printing quality monitoring system

A customized R2R μCP system, detailed in Supplementary Note 2, was developed to evaluate displacement-based control for printing variable pattern sizes24. Unlike conventional systems, this setup integrates two displacement sensors to measure the vertical displacement of the V-shaped PDMS stamp (Supplementary Fig. S5). Each sensor consists of a metal plate, affixed to the print roller for vertical movement, and a capacitive sensor (CS3, Micro-Epsilon) mounted on the system frame via an adaptor. The sensors were calibrated using a three-point method, leveraging the linear relationship between capacitance and the plate-sensor separation to accurately measure PDMS displacement. Before each experiment, the system was calibrated to a zero-displacement reference by gradually raising the print roller until the load cell detected contact between the PDMS stamp and the substrate, marking this as the zero-displacement position.

To monitor the printing results, a condensation figure (CF) monitoring system (Supplementary Fig. S6) was integrated into the R2R platform. During printing, areas covered by ink exhibit higher surface energy than unprinted gold regions, leading to different droplet formation behavior when exposed to water vapor25. Specifically, droplets formed on gold surfaces are denser and larger than those on printed areas, enabling in-situ visual differentiation of the printed patterns under CFs prior to the etching step. The captured CF images are subsequently segmented to extract the linewidth information, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S7.

Neural network-based MPC control

To achieve high-precision control in R2R μCP, our system employs a flexure-based mechanism that uses elastic deformation of compliant elements to eliminate backlash and friction, enabling superior positioning accuracy. Flexures are widely used in high-resolution R2R printing for enhanced motion and force control. However, modeling the dynamics of complex flexure mechanisms is challenging due to their nonlinear behavior and computationally intensive parameter identification26. Traditional PID controllers are inadequate for managing these nonlinear dynamics in R2R μCP24, necessitating advanced control strategies. To address this issue, we propose a neural network-based MPC strategy for precise flexure-based position control in R2R μCP. A feedforward neural network approximates the nonlinear system dynamics, using delayed control signals (actuator voltages) and measured displacements as inputs to predict displacement. Integrated into an MPC framework, this model optimizes control inputs in real-time for accurate tracking of the desired displacement trajectory of the V-shaped PDMS stamp. Details are provided in Supplementary Note 3 and Note 4.

R2R microcontact printing

To evaluate V-shaped PDMS stamps under realistic R2R μCP conditions, a standard printing process was conducted using hexadecanethiol (HDT) ink (15 mM in ethanol), V-shaped PDMS stamps fabricated as described previously, and a 0.1 mm polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate coated with a 30 nm gold layer via R2R sputtering. A custom ink reservoir beneath the print roller ensured consistent ink delivery. The fully automated system was initialized via software, with web tension, web speed, and stamp displacement preconfigured. During printing, the ink reservoir was raised to transfer ink to the stamp, while voice coil actuators, controlled by the neural network-based MPC, applied precise compressive displacement derived from the physics-informed model relating stamp deformation to contact area. Web transport was then activated, with an inline monitoring system assessing print quality in real time. After printing, the patterned substrate was wet-etched for 8 minutes in a solution of 0.1 M thiourea and 0.01 M ferric nitrate in deionized water to selectively remove unprotected gold, finalizing the printed structures.

Results

V-shaped PDMS stamp deformation

To establish the relationship between displacement and contact area, we employed a combined numerical and experimental method as shown in Fig. 3a. In the simulation, we examined PDMS stamps with various aspect ratios, and the results are presented in Fig. 3b. The data reveal a strong correlation between displacement and contact area, which is expected because the primary deformation occurs at the triangular tip of the stamp rather than in the bulk of the PDMS body during compression.

a The schematic diagram and experimental setup of the single-roller system, along with simulated deformation of the V-shaped polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp under applied displacements. b The simulated contact linewidth as a function of displacement for five different aspect ratios A of the stamp is compared with experimental results. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the contact area across six measurements from the single-roller system.

To validate the simulation, we fabricated PDMS stamps with aspect ratios of 0.33 and 0.5 and evaluated them using our custom-built single-roller system. The experimental results overlaid with the simulation in Fig. 3b show strong agreement with the simulation across the full displacement range. This consistency confirms the accuracy of the numerical model and demonstrates its practical value in guiding the R2R µCP process. These collected data will be used to derive the dynamics between the displacement and contact area. Specifically, for a target linewidth required by a given application, the model enables determination of the appropriate stamp displacement, thereby improving process predictability and control.

Training of the neural network

To enable closed-loop displacement control, we trained a neural network to model the system dynamics. Training data were first collected via pulse-train excitation. Figure 4a and b show the input pulse sequence with randomly varying amplitudes and the corresponding displacement response of the system. Each pulse lasts for one second, allowing the system to reach a steady-state response within each interval. The sampling interval is set to 10 ms, consistent with the control loop rate. The input voltages to the voice coil actuators are randomly selected within the range of [1.5 V, 2.5 V]. These bounds were established by first identifying the minimum voltage at which a measurable force is detected by the load cells and then adding an additional 1 V to ensure that the resulting displacement remains within approximately 150 μm. To sufficiently span the dynamic range of the system, a total of 60,000 samples were collected, with 80% of the data used for training and the remaining 20% reserved for testing.

a Pulse train inputs to the voice coil actuator. b Responses of the V-shaped polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) displacement. c Actual displacement and predicted displacement by the neural network model. d The corresponding errors of the predicted displacement. e Experimental results of the neural network-based MPC controller using sinusoidal signals as the setpoint.

Since the displacement behavior depends on both historical output values and input control signals, the system dynamics are approximated using a nonlinear autoregressive model with exogenous inputs, as detailed in the Supplementary Note 3. The input and output time delays are set to 2. The neural network contains 7 hidden nodes, selected as a trade-off between inference time and prediction accuracy. A tangent-sigmoid activation function is used, as the input data are normalized within the range [−1, 1]. The neural network was trained in MATLAB using the Levenberg–Marquardt solver. The maximum epoch was set to 1000 and used two termination criteria: (i) a minimum-gradient threshold (training stops when the gradient norm falls below 1 × 10⁻⁷) and (ii) validation early stopping (training stops when the validation error fails to improve for six consecutive validation checks). The prediction performance on the testing dataset is illustrated in Fig. 4c and d, achieving an RMSE of 0.88 μm. Additional comparisons with Long Short-Term Memory networks are provided in the Supplementary Fig. S8.

Displacement control performance

We implemented a neural network-based MPC to control the displacement of the V-shaped PDMS stamp in the R2R μCP system, using a neural network model of the system’s displacement behavior. MPC parameters, including control horizon (\(M\)), prediction horizon (\(P\)), and weighting factor (\(\lambda\)), were tuned in a MATLAB simulation environment, where the neural network model replicated the R2R system’s dynamics. \(M\) and \(P\) were incrementally increased from 1 to 20 sampling intervals, with stable displacement control achieved at \(M\ge 2\). Optimal values of \(M=4\) and \(P=11\) were selected, yielding precise real-time displacement control (Supplementary Table S4). Timing tests confirmed an MPC runtime of approximately 7 ms, meeting the 10 ms control loop requirement (Supplementary Table S5). Considering both displacement control performance and potential shock to the system, we select λ = 0.01 as shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. These parameters were then applied to the R2R system for evaluation.

The neural network-based MPC controller was evaluated using sinusoidal reference signals as displacement setpoints, with results shown in Fig. 4e. As the V-shaped PDMS stamp’s length is shorter than the print roller’s circumference, two stamps were stitched together, causing minor displacement variations at their junction. However, the enlarged view in Fig. 4e shows the actual displacement closely tracks the reference trajectory, achieving an RMSE of 5 μm, demonstrating the controller’s high accuracy and responsiveness in R2R μCP displacement regulation.

Variable linewidth printing results

To demonstrate the versatility of a single V-shaped PDMS stamp (width 146 µm, height 73 µm, aspect ratio 0.5), we printed three distinct linewidths in the R2R μCP process using controlled displacements of 10 µm, 30 µm, and 50 µm. A custom imaging system captured CFs for non-destructive, contact-free linewidth measurements without etching. The resulting linewidths, averaged from six measurements, were 18.13 ± 1.04 µm, 67.09 ± 1.13 µm, and 110.52 ± 2.60 µm, respectively, with representative patterns shown in Fig. 5a, showcasing precise displacement-controlled patterning.

a Different pattern sizes were printed using a single V-shaped polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp, with displacement setpoints of 10 µm, 30 µm, and 50 µm from left to right, respectively. b The size of the printed patterns can be also derived from the measured displacement according to the physical model. Here we printed a pattern with changing linewidth and the predicted linewidth from the physical model and the measured linewidth from the condensation figures are compared. c Coplanar inverted-F antenna patterns of varying scales were printed using a single V-shaped PDMS stamp, resulting in linewidths of 193.3 ± 13.96 µm (narrow) and 440.83 ± 30.29 µm (wide), with their radio frequency responses characterized. Shaded areas represent the standard deviation of the measured line width from six measurements.

Additionally, we performed continuous printing of variable linewidths by dynamically adjusting the displacement setpoint (Supplementary Movie 1). In this experiment, a stepwise varying displacement profile was applied to the controller, and the corresponding linewidths were predicted based on the previously established displacement-to-width relationship. The printed results and corresponding CFs are presented in Fig. 5b. The predicted widths were computed from the recorded displacement, while the measured widths were extracted from the CFs. Due to the 2 Hz frame rate of the imaging system, the measured widths exhibit higher fluctuations compared to the predicted values. Nevertheless, the predicted and measured widths show strong agreement, confirming the system’s capability for real-time control of variable-width patterning using a single V-shaped PDMS stamp.

Antenna printing using V-shaped PDMS

To demonstrate the feasibility and versatility of our approach, we used the V-shaped PDMS stamp to print more complex geometries on flexible substrates. First, we designed a coplanar inverted-F antenna consisting solely of straight-line segments. The V-shaped PDMS stamp used in this experiment has a width of 1 mm and height of 0.5 mm. Two different linewidths were printed using a single stamp with linewidths of 193.3 ± 13.96 µm (narrow) and 440.83 ± 30.29 µm (wide) as shown in Fig. 5c. The results show that the patterns can be proportionally scaled by adjusting the displacement, which is advantageous for parametric studies. For the coplanar inverted-F antennas with different linewidths, the narrower device shows a shallower resonance with S11 ≈ − 6.5 dB, indicating increased ohmic loss, and a lower quality factor Q (broader resonance) as shown in Fig. 5c. In contrast, the wider device reaches S11 ≈ − 10.5 dB reflecting reduced loss, and a higher Q.

To further demonstrate the practical utility of the V-shaped PDMS stamp, we also designed and printed spiral and kinked patterns (Supplementary Fig. S10 and Table S6). The molds for the spiral and kinked patterns were created using the Swept Cut function in SolidWorks. Applying different displacements during printing altered the linewidths of the spiral and kinked patterns, confirming the controllable feature size of our displacement-based printing method.

Discussions

This work demonstrates variable-size patterning in R2R µCP using V-shaped PDMS stamps. While the approach enables continuous tuning of linewidths, the practically achievable resolution is bounded by master fabrication and actuator precision. In our study, we used a commercial printer to fabricate V-shaped masters, which imposes a limit on the minimum achievable feature size. To evaluate stamp fabrication consistency, we designed a meander pattern stamp for testing (printed pattern example shown in Supplementary Fig. S11), with a detailed analysis provided in Supplementary Note 5. In the literature, alternative fabrication techniques have been reported that enable higher-resolution molds for PDMS casting. For instance, V-shaped molds can be produced via photolithography followed by wet etching of silicon, enabling sub-100 nm apex dimensions at the base of the V-shaped trenches27. Other conventional photolithography can be also applied for high-precision molds such as grayscale masks for multi-depth exposure28 or moving masks29 to produce V-shaped structures. When such nanoscale features are employed in printing, the displacement control system must also offer commensurate resolution to maintain pattern fidelity. In our current setup, the displacement control resolution is approximately 5 µm. This limitation is partly due to the mechanical components of the R2R system being fabricated in an academic machine shop, where precision machining tolerances are difficult to achieve. Future work will focus on enhancing the mechanical precision of the R2R platform, potentially through the integration of high-accuracy, professionally machined components to improve displacement control and overall printing resolution.

Against this backdrop, we compared V-shaped and pyramidal PDMS stamps for μCP. Both utilize elastic deformation to tune feature size, but their geometries produce distinct outcomes: V-shaped stamps enable a continuous, monotonic mapping from applied deformation to printed linewidth, facilitating real-time adjustments with a single master, whereas pyramidal stamps primarily modify the contact area to modulate square-dot features, resulting in discrete changes in printed feature area. In terms of pattern versatility, V-shaped PDMS stamps effectively produce diverse circuit geometries, while pyramidal PDMS stamps are better suited for periodic dot arrays. From a control perspective, displacement-based regulation on our R2R platform enhances contact mechanics stability, reducing linewidth variability compared to force-based control, thus providing V-shaped stamps with superior accuracy and run-to-run consistency. At the prototyping scale, system costs are comparable, as both approaches support a cleanroom-free fabrication (e.g., using 3D-printed masters), with photolithography available for applications requiring higher precision.

Conclusions

In this work, we demonstrate that V-shaped PDMS stamps can be used in R2R µCP to enable variable pattern size printing. Since force-based control cannot precisely regulate the deformation of PDMS stamps, we adopt a displacement-based control strategy to achieve stable and tunable linewidth printing. The physical relationship between stamp displacement and contact area is established through a combination of simulation and experimental data. The simulation employs a Neo-Hookean model to represent the hyperelastic properties of PDMS, and stamps with varying aspect ratios are analyzed. To validate the simulation results, we utilize a single-roller system that mimics the actual R2R printing process. This setup allows for simultaneous measurement of displacement and contact area, enabling direct comparison with simulation outputs. Together, the experimental and simulation data form the physics-informed model of PDMS deformation. Building on this model, we develop a neural network-based MPC framework to regulate the displacement of the PDMS stamp in the R2R system. The displacement can be precisely controlled using the proposed control algorithm, allowing us to print lines with different widths using a single PDMS stamp and demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed control method. Finally, we demonstrated the system’s versatility and broad applicability by successfully printing a coplanar inverted-F antenna, a spiral pattern, and various kinked patterns.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Code for the work is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Kumar, A. & Whitesides, G. M. Features of gold having micrometer to centimeter dimensions can be formed through a combination of stamping with an elastomeric stamp and an alkanethiol ‘“ink”’ followed by chemical etching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 63, 2002–2004 (1993).

Pallab, N. et al. Polymer brush-assisted microcontact printing: using a tailor-made polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp for precise patterning of rough surfaces. Polym. Chem. 15, 853–867 (2024).

Mukherjee, A. et al. Synthesis and Microcontact Printing of novel nanoflowers of ZnO_Ag_rGO nanocomposite to check microbial adhesion. Nano Struct. Nano-Objects 38, 101140 (2024).

Torres-Cavanillas, R., Gavara-Edo, M. & Coronado, E. Bistable spin-crossover nanoparticles for molecular electronics. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307718 (2024).

Du, B. et al. Combined laser-induced graphene and microcontact printing for processing scalable and stackable micro-stripe patterns toward multifunctional electronic devices. Carbon 225, 119148 (2024).

Gödrich, S., Brodoceanu, D., Kuznetsov, V., Kraus, T. & Papastavrou, G. Defined transfer of colloidal particles by electrochemical microcontact printing. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2400202 (2024).

Larrañaga, E. et al. Long-range organization of intestinal 2D-crypts using exogenous Wnt3a micropatterning. Nat. Commun. 16, 382 (2025).

Sun, M., Zhang, J., Xuanyuan, T., Liu, X. & Liu, W. Facile and rapid microcontact printing of additive-free polydimethylsiloxane for biological patterning diversity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 20132–20142 (2024).

Khan, S. et al. Comprehensive fluorescence profiles of contamination-prone foods applied to the design of microcontact-printed in situ functional oligonucleotide sensors. Sci. Rep. 14, 8277 (2024).

Hager, R. et al. Microcontact printing of biomolecules on various polymeric substrates: limitations and applicability for fluorescence microscopy and subcellular micropatterning assays. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4, 6887–6896 (2022).

Shiwarski, D. J. et al. Fibronectin-based nanomechanical biosensors to map 3D surface strains in live cells and tissue. Nat. Commun. 11, 5883 (2020).

Garibyan, M. et al. Engineering programmable material-to-cell pathways via synthetic notch receptors to spatially control differentiation in multicellular constructs. Nat. Commun. 15, 5891 (2024).

Xue, X. et al. A patterned human neural tube model using microfluidic gradients. Nature 628, 391–399 (2024).

Petrzelka, J. E. & Hardt, D. E. Static load-displacement behavior of PDMS microfeatures for soft lithography. J. Micromech. Microeng. 22, 075015 (2012).

Xia, Y. & Whitesides, G. M. Extending Microcontact Printing as a Microlithographic Technique. Langmuir 13, 2059–2067 (1997).

Filipponi, L., Livingston, P., Kašpar, O., Tokárová, V. & Nicolau, D. V. Protein patterning by microcontact printing using pyramidal PDMS stamps. Biomed. Microdevices 18, 9 (2016).

Hong, J. M., Ozkeskin, F. M. & Zou, J. A micromachined elastomeric tip array for contact printing with variable dot size and density. J. Micromech. Microeng. 18, 015003 (2008).

Jin, C. & Qiao, Q. Deformation of Pyramidal PDMS Stamps During Microcontact Printing. Journal of Applied Mechanics 83, (2016).

Li, H.-W., Muir, B. V. O., Fichet, G. & Huck, W. T. S. Nanocontact Printing: A Route to Sub-50-nm-Scale Chemical and Biological Patterning. Langmuir 19, 1963–1965 (2003).

Zhou, X., Xu, H., Cheng, J., Zhao, N. & Chen, S.-C. Flexure-based Roll-to-roll Platform: A Practical Solution for Realizing Large-area Microcontact Printing. Sci. Rep. 5, 10402 (2015).

Choi, Y.-M., Kang, D., Lim, S., Lee, M. G. & Lee, S.-H. High-Precision Printing Force Control System for Roll-to-Roll Manufacturing. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 22, 2351–2358 (2017).

Petrzelka, J. E. Contact region fidelity, sensitivity, and control in roll-based soft lithography. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2012).

Peng, J., Tomsia, A. P., Jiang, L., Tang, B. Z. & Cheng, Q. Stiff and tough PDMS-MMT layered nanocomposites visualized by AIE luminogens. Nat. Commun. 12, 4539 (2021).

Yan, J. & Du, X. Neural-network-based adaptive model predictive control for a flexure-based roll-to-roll contact printing system. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 27, 5084–5094 (2022).

Yan, J., Ma, R. & Du, X. Consistent optical surface inspection based on open environment droplet size-controlled condensation figures. Meas. Sci. Technol. 32, 105405 (2021).

Zhou, X., Wang, D., Wang, J. & Chen, S.-C. Precision design and control of a flexure-based roll-to-roll printing system. Precis. Eng. 45, 332–341 (2016).

Wu, J., Tao, K. & Miao, J. Production of centimeter-scale sub-wavelength nanopatterns by controlling the light path of adhesive photomasks. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 6796–6808 (2015).

Schuster, C., Ekindorf, G., Voigt, A., Schleunitz, A. & Grützner, G. Pushing deep greyscale lithography beyond 100-µm pattern depth with a novel photoresist. in Novel Patterning Technologies 2023 vol. 12497 203–216 (SPIE, 2023).

Hirai, Y., Inamoto, Y., Sugano, K., Tsuchiya, T. & Tabata, O. Moving mask UV lithography for three-dimensional structuring. J. Micromech. Microeng. 17, 199 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank Isabella Lambros and Ilya McCune-Pedit for setting up the single-roller experimental platform. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. CMMI-1942185.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors are with the Department of Mechanical and Industrial of Engineering, and the Institute for Applied Life Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, 01003, USA. J.Y. conducted all experiments and drafted the initial manuscript. H.D. performed the finite element analysis and contributed to select experiments. X.D. supervised the project, secured funding, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Anabel Renteria and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Cecilia de Carvalho Castro Silva] and [Philip Coatsworth]. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, J., Du, H. & Du, X. Physics-informed displacement control for variable pattern printing with V-shaped PDMS stamps in roll-to-roll microcontact printing. Commun Eng 4, 214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00553-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00553-9