Abstract

Conventional dry filtration materials present a high initial efficiency but suffer from poor regenerability and limited functionality. Conversely, liquid-based purification strategies leverage the high capture potential of gas–liquid interfaces, but face challenges such as insufficient material strength, complex fabrication, and difficulties in large-scale application. Here, we proposed a porous ceramic-based bubble-enhanced filtration system (PCBEFS). The proposed system employs tunable porous ceramics as bubble generators in the water medium, thereby enabling highly efficient wet removal of particulate matter, while simultaneously providing air humidification, formaldehyde removal, and antibacterial functions. Furthermore, we established an empirical mathematical model linking pore structure, bubble characteristics, and removal performance, which elucidates the structure–activity relationship and presents insights into the capture mechanism jointly governed by porous ceramics and gas–liquid interfaces. PCBEFS addresses the limitations of the existing liquid-based purification systems and contributes substantially to multifunctional indoor air pollution control with strong engineering potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Particulate matter (PM) pollution, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), has been classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO)1, and presents considerable risk to human health worldwide2,3. When compared with outdoor particles, PM2.5 in indoor environments presents a more direct and prolonged health risk owing to longer exposure times. Indoor PM2.5 originates from daily activities such as cooking, smoking, and incense burning4, along with outdoor sources, such as industrial emissions and vehicle exhaust5,6 via air leakage pathways7,8. PM2.5 can penetrate deep into the alveoli and cause multifaceted damage to the respiratory, immune, and cardiovascular systems owing to its ultrafine size9,10. Therefore, controlling indoor PM2.5 pollution is crucial for improving living environments and enhancing public health.

Currently, the mainstream indoor air purification technologies are dominated by dry filtration. High-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, are widely implemented in portable air purifiers and building ventilation and air-conditioning systems owing to their high initial filtration efficiency11,12,13. However, during long-term operation, PM gradually accumulates on the HEPA surface, presenting increased pressure drop, performance degradation, and even becoming a potential source of secondary PM pollution14,15,16. In addition, HEPA filters are primarily composed of fibers17, which are poorly washable and lack renewability, thereby limiting their sustainable application. To overcome these limitations, wet air purification technologies based on gas–liquid interactions have been developed. Conventional wet air purification devices are typically applied in industrial environments18,19,20, relying primarily on spraying21,22,23,24 and water baths25,26,27. Although they can capture particulates and certain gaseous pollutants, they typically suffer from oversized droplets22, low purification efficiency, and bulky equipment28, making them unsuitable for typical indoor environments.

In recent years, the advantages of gas–liquid interfaces in particulate capture have gained considerable interest in liquid-based air purification strategies29,30. Hou et al.31 proposed an electrochemical liquid-based system (ELBS), in which polymer-coated metal meshes and functional liquids generate bubbles. Additionally, electrochemical devices regulate the interfacial wettability, achieving excellent removal efficiency. Zhao et a.l32 developed a liquid-gated topological gradient microfluidic device (LGTGM), where 3D-printed photocured resin combined with functional liquids enables uniform bubble generation and high-efficiency air purification. Hong et al.33, developed a circulation/respiration air purification system (CAPS) based on the human circulatory and respiratory systems, which uses PDMS organic membranes and water to achieve particle capture and gas exchange. These studies demonstrate the potential of liquid-based materials in air purification. However, they also face several challenges. For example, the mechanical strength of organic membranes or resins cannot34 satisfy the requirements of long-term engineering applications. The fabrication process for bubble-generating materials is complex and expensive and typically depends on specific functional liquids for effective operation. Some systems require additional electrochemical control devices, thereby hindering large-scale deployment. Thus, retaining the advantages of gas–liquid interfacial purification while overcoming the problems of scalability and durability is a major challenge in this field.

Porous ceramics present an ideal solution to these limitations. As rigid inorganic materials with high mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and controllable pore structures35,36,37, porous ceramics exhibit excellent regenerability38 and can also serve as stable bubble generators. They overcome the fragility of organic membranes and resins owing to their flexural strength that reaches tens of MPa. Their advanced fabrication processes and low cost greatly enhance the scalability of liquid-based strategies for large-scale applications. Additionally, their tunable pore size distributions present a unique platform for analyzing synergistic mechanisms between gas–liquid interfaces and dry filtration (Supplementary Note S1, for detailed discussion). Therefore, introducing porous ceramics into liquid-based air purification strategies can ensure structural stability and pore tunability, and enable scalable fabrication based on advanced processes, thereby bridging the performance optimization and practical application.

Although previous studies3,39,40 have reported the use of porous ceramics in dry filtration, their potential in liquid-based air purification systems has not yet been systematically analyzed. The previous studies conducted on bubble dynamics41,42,43 have primarily focused on the effects of operating conditions on bubble behavior in commercial microporous media. Conversely, limited research has been conducted on the influence of the pore structures of matrix materials on the bubble characteristics, which affects the particulate removal efficiency. In particular, systematic analyses have not yet been conducted on optimizing the wet removal performance by tailoring the pore structures of bubble-generating materials.

In this study, we proposed an innovative Porous Ceramic-Based Bubble-Enhanced Filtration System (PCBEFS) to address these challenges. Using water as the working medium and porous ceramics prepared by the pore-forming agent method as bubble generators, this system achieves highly efficient wet removal of PM2.5. By analyzing the pore size distribution and bubble generation characteristics, this study demonstrates the influence of pore structures on the wet removal efficiency and establishes an empirical mathematical model linking pore structure, bubble characteristics, and removal performance, thereby elucidating the structure–activity relationship. Consequently, the applications of PCBEFS are further extended to air humidification, formaldehyde removal, antibacterial performance, and multisystem integration, thereby presenting theoretical support and practical pathways for constructing renewable, structurally tunable, and integrated air purification systems.

Results

Working mechanism of PCBEFS

The working mechanism of PCBEFS comprises two stages: preliminary filtration and secondary absorption (Fig. 1). Dusty air enters the system from the bottom, where the porous ceramic first captures larger airborne particles during preliminary filtration. Subsequently, the air bubbles enveloping the smaller microparticles ascend through the water, effectuating the secondary absorption. During the preliminary filtration stage, a gas–solid system was formed between the particles and the porous ceramics, wherein filtration was primarily achieved through interception, inertial collision, and diffusion. In the secondary absorption stage, a solid–gas–liquid system emerged as particles attached to rising bubbles continued to ascend owing to inertia, and were captured at the gas–liquid interfaces. These particles were ultimately submerged in the water under the combined forces of liquid surface tension (Fγ), gravity (FG), and capillary pressure within the bubbles31,44.

Particulate matter (PM) undergoes preliminary filtration through interception, inertial collision, and diffusion, followed by secondary absorption as particles are transported across the gas–liquid medium within the bubbles. During the bubble-forming stage, particles are subjected to gravity (FG), resistance (FD), and force generated by the pressure difference across the pores (FP1). During the bubble-rising stage, particles are subjected to gravity (FG) and resistance (FD). During the particle capturing stage, the forces include those of gravity (FG), that generated by the capillary pressure inside the bubble (FP2), and surface tension of the liquid (Fγ)31,44.

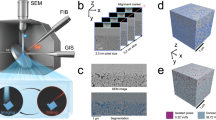

Physical properties of porous ceramics

We prepared nine groups of porous ceramics with varying pore size distributions by implementing the pore-forming agent method using alumina as the framework material, glass powder as the sintering aid, and graphite as the pore-forming agent (Fig. 2a). These porous ceramics were categorized into two groups: in the first group, only the additive amount of the pore-forming agent added to each sample was varied; in the second group, only the particle size of the pore-forming agent added to each sample was varied. We aimed to analyze the effects of pore-forming agent addition and particle size change on the pore size distribution of porous ceramics, respectively. The porous ceramics prepared by varying only the amount of pore-forming agent added were termed C0, C10, C20, C30, and C40.The number after C represents the mass percentage (wt%) of the pore-forming agent. The porous ceramics that vary only the porous agent particle size are termed as P10, P75, P100, and P200, and the number after P represents the particle size of the porous agent (μm).

a Preparation process of porous ceramics. Five samples with graphite addition of 0%, 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% were prepared by selecting 50 μm graphite and named as C0, C10, C20, C30 and C40, respectively. Four groups of samples containing 10, 75, 100, and 200 μm graphite were prepared by maintaining the graphite addition at 20%, which are termed as P10, P75, P100, and P200, respectively. b SEM images of the longitudinal sections of various porous ceramics. c XRD patterns of porous ceramics including sintered porous ceramics, graphite-added but unsintered green body, and no-graphite but unsintered green body. d, e Pore size distribution curves of different porous ceramics. f Bending strength and apparent porosity of different porous ceramics. All data points and error bars represent mean values ± s.d., calculated from four measurements for bending strength and five measurements for porosity. g, h Pressure-drop gradient versus air infiltration rate for different porous ceramics. i Darcy permeability k1 and bubble point pressure of different porous ceramics. All data points and error bars in bubble point pressure represent mean values ± s.d. of three measurements.

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images presented in Fig. 2b show that in the absence of a pore-forming agent, the pores predominantly comprise closed pores created through the aggregation of alumina particles. These pores are characterized by a lower quantity of pores, smaller pore diameters, and limited connectivity among the pores. The addition of a pore-forming agent presents a higher number of pores and improved connectivity, which presents an increase in the penetration of pores and the presence of localized large pores (Fig. 2b, C40). With a smaller particle size of the pore-forming agent, the pores were small and distributed relatively uniformly. The number of pores decreased with the increase in the particle size of the pore-forming agent; however, the size of each pore increased markedly, causing the formation of strip-like macropores (Fig. 2b, P200). This strip-like formation was attributed to the scale-like form of the pore-forming agent.

Figure 2c shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples before and after sintering. Following sintering, the crystalline phases of the porous ceramics were all α-Al2O3. Prior to sintering, the primary crystalline phase of the billet without graphite addition was α-Al2O3, and the secondary crystalline phase was diaoyudaoite (NaAl11O17), which was formed by glass powder. The primary crystalline phase of the graphite-added blanks was α-Al2O3, and the secondary crystalline phases were diaoyudaoite (NaAl11O17) and carbon (C).

The most probable pore diameter, identified as the peak in the pore size distribution graphs (Fig. 2d and e), is a crucial parameter that indicates the pore size that was observed most frequently in the distribution of porous ceramics45,46. The pore size distribution of each sample was typically dominated by a single peak distribution. As the amount of pore-forming agent added or the particle size increases, the most probable pore size gradually increases, while the pore size distribution curve shifts to the right. For the sample groups, P10–P200, despite the same amount of pore-forming agent added, the most-probable pore diameters were smaller than the actual sizes of the pore-forming agent particles used. This discrepancy was attributed to the linear shrinkage that occurs during the sintering of porous ceramics, which similarly reduced the pore sizes (Supplementary Fig. S1). These experimental findings concurred with those reported by Tuncer et al.47.

Figure 2f shows an opposite trend between the apparent porosity and bending strength in each of the C and P-series samples. This phenomenon can be attributed to the pore-formation mechanism of the pore-forming agent within the porous ceramics. An increase in the addition of the pore-forming agent enhances the pore structure along with the apparent porosity. Furthermore, it disrupts the connectivity among the alumina particles, thereby causing an increase in the microcracks within the internal structure, which subsequently reduces the bending strength. Furthermore, increasing the graphite particle size presents a lesser impact on the apparent porosity; however, it substantially decreased the bending strength. This reduction was attributed to the larger pore-forming agent particles creating more pronounced defects during sintering. These defects then become focal points of stress concentration under mechanical load, thereby reducing the mechanical properties of the material.

Air permeability and bubble generation

The Darcy permeability is an essential index that describes the fluid permeation capacity of porous ceramics, which was determined by factors such as the pore size, porosity, and pore structure48. Typically, higher air permeability in porous ceramics corresponds to a smaller pressure drop gradient and greater gas flow rate through the material within a given time frame. However, excessively high permeability can reduce the ability of the material to intercept PM and can cause the excessive generation of air bubbles. This overproduction may cause bubble agglomeration and interference, thereby disrupting the stable transport of PM across the gas–liquid interface.

Figure 2g and h shows the relationship between the pressure drop gradient and air infiltration velocity as air passes through the samples. A linear correlation, which was consistent with Darcy’s law, was observed and can be expressed as shown in Eq. (1), which is applicable within the range of the air infiltration velocities examined in this study49,50,51.

where \(\frac{dP}{dL}\) denotes the pressure drop gradient, η denotes the hydrodynamic viscosity, k1 denotes the Darcy permeability, and vs denotes the air infiltration rate.

Therefore, the Darcy permeability (k1) of each sample was determined through fitting performed according to Eq. (1). Notably, the order of magnitude of permeability for the samples lies in the order of 10−9, which is considerably higher than those reported in some previous studies39,52, while the bubble point pressure is lower than those observed in certain other works41,43,53 (Fig. 2i). The permeability can be characterized by the Carman–Kozeny equation \({k}_{1}\propto (p{d}^{2}/16{f}_{CK}{\tau }^{2})\), and the bubble point pressure can be described by the Laplace equation \({P}_{B}\propto (2\sigma \,\cos \theta /d)\)53. Both are governed by the characteristic pore size d and are theoretically negatively correlated. The results observed in this study are consistent with this theoretical expectation. A comparison between the P-series and C-series samples shows that graphite content (which primarily determines the number of through-pores) has a more pronounced effect on permeability than graphite particle size (which mainly determines pore size). Increasing the number of through-pores substantially enlarges the effective flow cross-sectional area and the number of parallel channels, thereby reducing overall flow resistance and lowering bubble point pressure. In contrast, simply increasing pore size decreases local channel resistance but has a less pronounced impact on overall permeability. Compared with previous studies, the porous ceramics in this study exhibit excellent gas permeability (Supplementary Note S2), which facilitates the generation of high-throughput bubbles.

By tuning graphite content and particle size, it is possible not only to regulate the permeability of porous ceramics—that is, the gas transport within the porous matrix—but also to control bubble generation. On this basis, we further analyzed the bubble generation characteristics. Figure 3a illustrates bubble generation at a single pore. High-speed imaging reveals that bubble clusters on the porous ceramic surface display high-throughput release behavior (Fig. 3b). Due to the non-uniform pore size distribution of porous ceramics, bubbles of different scales emerge simultaneously in different regions even under the same permeation velocity. At a flow rate of ~0.2 L min−1, large, medium, and small bubbles can form simultaneously on the same porous ceramic surface (Fig. 3c). Their generation proceeds through three typical stages: gas tongue formation, necking, and pinch-off (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Video 1). This indicates that bubble generation is not governed solely by individual pore size, but is jointly influenced by the pore size distribution and local flow conditions.

a Schematic of bubble generation at a single pore. b High-speed camera images of high-throughput bubbles generated at a flow rate of ~0.2 L min−1 (same flow rate as in c, d). c Representative images of large, medium, and small bubbles produced from nonuniform pores on the same porous ceramic surface. d Time-resolved snapshots of bubble formation, showing three stages: gas tongue formation, neck formation, and pinch-off. e Kernel density estimation of equivalent bubble diameters for nine groups of porous ceramic samples at a flow rate of 0.5 L min−1, arranged from top to bottom by increasing most probable pore size. f Distributions of average equivalent bubble diameter across porous ceramic samples under four different flow rates.

To further reveal the relationship between pore size distribution and bubble size distribution, we analyzed bubble diameters across nine groups of porous ceramic samples. At a flow rate of 0.5 L min−1, the kernel density estimation curves (Fig. 3e) of equivalent bubble diameter shift rightward and broaden as the most probable pore size increases, evolving from unimodal to bimodal. This indicates that average bubble size increases while size uniformity decreases. Samples with smaller pore sizes produce smaller bubbles with narrower distributions, whereas those with larger pore sizes generate larger bubbles with lower uniformity. Cross-flowrate comparisons (Fig. 3f) further show that at the same flow rate, the average equivalent bubble diameter increases with increasing most probable pore size; while for the same sample, bubble size increases as flow rate rises. Together, these results confirm that pore size distribution governs not only air permeation performance but also directly controls bubble size distribution and uniformity. The rightward shift and broadening of the bubble distribution curve are consistent with the overall rightward shift in the pore size distribution as the most probable pore size of porous ceramics increases. This intuitively reflects the direct control of bubble size by the material’s pore structure. This finding aligns with the observation by Jiang et al.53 that smaller pore sizes with narrower distributions favor the generation of smaller and more uniform bubbles.

PM removal performance of PCBEFS

A portable device was designed for operating PCBEFS (Fig. 4a) based on the exceptional permeability of porous ceramics. The device comprised two containers: the upper vessel for water addition and the lower vessel for gas introduction. Porous ceramic was placed between the two containers, and secured with sealing rings and flanges to ensure airtight integrity. Due to the weak hydrophilic or hydrophobic properties of the porous ceramic surface (Supplementary Fig. S2), the PCBEFS can retain a substantial amount of water, while preventing droplet leakage under gravity. The gas flow rate was regulated using a rotameter and a high-precision electronic flowmeter, thereby enabling bubble generation at various gas supply rates (Supplementary Video 2). PM-laden gas pumped from the lower chamber into the PCBEFS generated bubbles in water via the porous ceramic. As the bubbles ascended, PM particles were captured at the gas–liquid interface (Fig. 4b). This mechanism was experimentally validated: the particles generated from mosquito coil combustion readily crossed the interface into the liquid when contacting water droplets, as shown in Fig. 4c. Furthermore, we established an air purification efficiency testing system for PCBEFS (Supplementary Fig. S3). The gases produced by mosquito coil combustion were pumped into the system for purification by PCBEFS, while a dust monitor tracked PM concentrations at the inlet and outlet. The clarity of the purified gas was markedly improved when compared with the polluted gas, as shown in Fig. 4d. Light scattering measurements of water samples before and after PCBEFS operation revealed enhanced light scattering in the post-treatment water. SEM images of dried water samples revealed abundant particulate matter (Supplementary Fig. S4), confirming the effective transfer of particles from the gas phase to the liquid phase. Furthermore, when compared with porous ceramics operated in a dry state, those operated in water exhibited cleaner surfaces (Fig. 4e), indicating that the liquid lining mitigated PM clogging within the pores.

a Schematic of the PCBEFS-integrated device. b Schematic of the process of particle capture by the gas–liquid interfaces. c Optical microscopy image of particles (collected by burning mosquito coils) captured by the gas–liquid interface. d Photographs of gas phase before and after purification, and light scattering intensity of liquid phase before and after capturing particles (Tyndall effect). e SEM images of the surface of porous ceramic with and without liquid lining. f Effect of different flow rates and water levels on the wet PM2.5 removal efficiency of various porous ceramics. g Long-term PM removal efficiency test of PCBEFS with different porous ceramics and HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air filter) over 180 min at an air flow rate of 3 L min-1. h Efficiency loss rate for different PCBEFS and HEPA. i Comparison of the mathematical model curve describing the structure–activity relationship and the curves in the study by Chen et al.54. All data points and error bars in i represent mean values ± s.d. of all measurements for each sample in g between 30 and 180 minutes.

Regarding the operating parameters, the proposed system analyzed the effects of different flow rates and water levels on the PM2.5 removal efficiency of the PCBEFS (Fig. 4f). The results indicated that the PM2.5 removal efficiency of PCBEFS units composed of various porous ceramics remained between 96.58% and 99.97% across all three flow rates and three liquid levels. Lower flow rates and higher liquid levels are conducive to improving removal efficiency. This was observed because lower flow rates generated smaller bubbles and reduced the generation frequency, thereby increasing the gas–liquid interface area. Higher liquid levels extended the bubble residence time in the liquid phase, thereby enhancing the opportunity for particle capture.

To further evaluate the stability under conditions relevant to engineering applications, we conducted a 180-minute long-term operation test (Fig. 4g) under relatively high air flow rate (3 L/min, approximately 5 cm/s air permeation velocity) and a 6 cm water level. The results indicated that the PCBEFS, comprising partially porous ceramics, exhibited reduced removal efficiency during the initial 30 min, primarily due to droplet interference. The droplets generated by bubble collapse may be misidentified as particulate matter by the dust collector, presenting overestimated outlet concentrations. This interference was more pronounced in the initial phase but diminished after approximately 30 minutes, with the removal efficiency stabilizing thereafter. Therefore, this study defines the 0–30 min period as the prestabilization stage, 30–60 min as the initial stage, and 150–180 min as the final stage. The removal efficiency loss rate d was calculated as follows:

where a1 denotes the average removal efficiency in the initial stage, a2 denotes the average removal efficiency in the end stage, and d denotes the removal efficiency loss rate.

The results (Fig. 4h) indicated that within 180 min, the HEPA filter exhibited a loss rate of 5.14%, whereas all the PCBEFS filters demonstrated loss rates below 3.45%, indicating that PCBEFS maintains good efficiency retention over a certain operating period. In particular, the PCBEFS comprising C10 samples surpassed HEPA in terms of the removal efficiency after approximately 85 min, maintaining a slightly higher and relatively stable performance thereafter. Furthermore, within the 30–180-min interval, its average wet removal efficiency reached 86.9%, representing the best performance among all the samples under high-flow conditions. Overall, PCBEFS demonstrated relatively good stability and application potential at higher flow rates.

Furthermore, we evaluated the renewable performance of the porous ceramic. The results indicated that HEPA exhibited a notable decline in the removal efficiency after multiple ultrasonic cleanings, whereas the porous ceramic maintained stable removal efficiency post-cleaning and demonstrated a lower pressure drop increase rate. This indicated that the porous ceramic outperformed HEPA in terms of the structural stability and reusability, exhibiting favorable renewable potential (see Supplementary Note S3 for detailed experimental data and results).

Structure–activity relationship

The pore structure of porous ceramics strongly affects the bubble size, which affects the PM removal efficiency in PCBEFS. In particular, larger pore sizes produced larger bubbles, thereby reducing the specific surface area available for contact between the PM and the gas–liquid interface. Conversely, smaller pore sizes cause the formation of smaller bubbles, thereby increasing the specific surface area and enhancing the probability of PM contact with the gas–liquid interface. Therefore, the structure–activity relationship between the pore structure of porous ceramics and PM removal efficiency within PCBEFS must be analyzed.

Under constant air permeability and water level height, a describable mapping relationship exists between the bubble diameter and pore size. Based on the research conducted by Okada et al.41, the relationship between the bubble diameter and pore size can be expressed as follows:

where DB denotes the bubble diameter, γ denotes the surface tension of water, DP denotes the pore radius (the most probable pore radius), ρ denotes the density of water, and g denotes the acceleration due to gravity.

Consequently, we characterized the pore structure of porous ceramics using the most probable pore radius and comprehensively analyzed nine sample groups. The most probable pore radius of porous ceramics serves as the input parameter, converted to the corresponding bubble diameter via Eq. (3). The bubble diameters undergo further normalization to eliminate the order-of-magnitude differences. We employed a GaussAmp function for fitting using the normalized bubble diameter as the independent variable and the average wet removal efficiency of PM2.5 by PCBEFS within the 30–180 min interval as the dependent variable (Fig. 4g). This yielded an empirical mathematical model describing the structure–activity relationship linking pore structure, bubble characteristics, and removal performance:

where x denotes the normalized bubble diameter; \(\eta\) denotes the average wet removal efficiency of PM2.5; \({\eta }_{0}\) denotes the dry removal efficiency of porous ceramics; A denotes the interfacial transport coefficient reflecting particle transport efficiency across the gas–liquid interface; \({x}_{c}\) denotes the optimal bubble diameter for wet removal efficiency; w denotes a parameter corresponding to the full width at half maximum.

According to the fitting results, R2 = 0.95, which demonstrates that the model exhibits excellent fitting performance. Notably, the fitted dry efficiency, η0 = 0.696 aligns well with the dry removal efficiency range (approximately 0.6–0.7) observed in regeneration experiments conducted with porous ceramics (Supplementary Note S3), demonstrating the physical significance of the parameters. Thus, the overall removal efficiency of PCBEFS can be decomposed into the sum of the dry removal efficiency of the porous ceramic itself and the particle transport efficiency across the gas–liquid interface. The former is determined by the trapping effect of the porous structure, while the latter is regulated by the bubble dynamics characteristics. Furthermore, we evaluated the statistical robustness of the model through confidence intervals, residual analysis, and comparative fitting with multiple classical functional models. Results indicate that the GaussAmp model demonstrates superior accuracy and physical interpretability (see Supplementary Note S4 for details).

Further analysis indicates that the relationship between the most probable pore size and the kernel density estimation curve of equivalent bubble diameter has demonstrated that the pore size distribution directly determines the bubble diameter distribution and its uniformity. Smaller pore sizes produce smaller and more concentrated bubbles, while larger pore sizes generate larger bubbles with poorer uniformity. This pore size-induced variation in bubble distribution is further reflected in the model as the removal efficiency trend with respect to the normalized bubble diameter. The fitted curve (Fig. 4i) shows that the PM2.5 removal efficiency first increased and then decreased with an increase in the normalized bubble diameter, indicating an optimal size range for bubbles. This result strongly concurred with the findings of Chen et al.54. Based on VOF-DPM numerical simulations and electrocapacitive vector tomography (ECVT) experiments, they found that small bubbles exhibit low efficiency due to limited deformation and flow field effects, while large bubbles also show poor efficiency as they tend toward a spherical cap state with reduced specific surface area. Medium-sized bubbles, however, demonstrate the highest efficiency due to enhanced oscillation and wake effects. The interfacial transport coefficient in the proposed GaussAmp model partially reflects this physical mechanism. Thus, this model not only numerically aligns with experimental results but also gains support from existing research in terms of physical interpretation.

In summary, the mathematical model established in this study reveals the structure–activity relationship where porous ceramic structures influenced the particle removal efficiency by regulating bubble generation. Thus, the wet removal efficiency was jointly determined by the dry efficiency and interfacial transport efficiency. This finding not only highlights the dual-action mechanism of porous ceramics within the system but also provides a theoretical basis for optimizing the pore structure design of porous ceramics in PCBEFS.

Multifunctional application of PCBEFS

To further analyze the functionality of the PCBEFS, we observed that the PCBEFS demonstrated considerable potential for application in indoor air humidification, formaldehyde removal, and antibacterial function (Fig. 5a). The winter climate in northern China presents low indoor humidity, typically under 35%55, particularly under heating conditions. Under the winter working conditions, each PCBEFS can increase the relative humidity of a certain surrounding space by 27%–44% within 30 min, as shown in Fig. 5b(i) and (ii). Among them, the humidification effect of the PCBEFS, where P10 is located, was the most evident and the most stable, which can increase the RH in the chamber from the initial 33.9% to 78.1%, which represents an increase of 44.2%, exceeding the RH range of 30% to 60% at normal room temperature provided by ASHREA Standard56. This indicates that PCBEFS helps in improving the indoor humidity. Under summer operating conditions, each PCBEFS can increase the RH of a certain surrounding space to 20% to 25% within 30 min, as shown in Fig. 5b(iii) and (iv). Among them, the humidification effect of the PCBEFS, where C40 was located, was the most pronounced, which can increase the relative humidity of a small room from 59.3% to 84.5%. In addition to particulate pollution, the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) represented by formaldehyde (HCHO) were prevalent in indoor air, which also present a risk to human health57,58. In this study, we introduced a functional liquid comprising KMnO4 and H2SO4 for the efficient removal of HCHO. Among them, KMnO4 serves as a strong oxidant to oxidize HCHO to nontoxic carbon dioxide and water, whereas the acidic environment provided by H2SO4 helps in promoting the oxidation reaction. The formaldehyde removal efficiency of PCBEFS was more than 90% within 1 h under continuous operation conditions, as shown in Fig. 5c. Additionally, the control of microbial contamination in indoor air was equally important, particularly in underground spaces or densely populated environments, where microorganisms can cause disease transmission59,60. In this study, we introduced gentamicin into water to enhance the inhibition of airborne bacteria using PCBEFS. Using Escherichia coli as a typical strain of indoor air, changes in the bacterial activity before and after the addition of gentamicin to PCBEFS were observed through fluorescence staining imaging, and the antimicrobial efficiency was calculated. Following the addition of gentamicin, the vast majority of E. coli could be inactivated, and the antimicrobial efficiency reached over 90%, as shown in Fig. 5d and e. The results indicated that PCBEFS presents considerable advantages in particle removal and can increase the indoor humidity, efficiently remove indoor formaldehyde, and inhibit bacterial growth. Additionally, multiple PCBEFS devices can be modularly connected in series and parallel; the series connection can improve the air purification efficiency and the parallel connection can be used to realize high-throughput air purification (Supplementary Fig. S5), which presents a new possible pathway for realizing integrated indoor air purification.

a Schematic of the (i) humidification, (ii) formaldehyde removal, and (iii) antimicrobial functions of PCBEFS. b Humidification effect of PCBEFS on indoor localized space in northern China in winter and summer. (i) and (ii) show the humidification effect in winter. (iii) and (iv) depict the humidification effect in summer. c Comparison of formaldehyde removal efficiency of PCBEFS with KMnO4/H2SO4 and blank control (water only) within 1 h. d Fluorescence images of E. coli in water with and without antibiotics. Live bacteria were stained with SYTO-9 and dead bacteria were stained with PI. e Inactivation ratio of E. coli by the addition of antibiotics to the water. All the data points and error bars represent mean values ± s.d. of three measurements in b, and six measurements in d. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA; ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed an innovative multifunctional air purification system called the PCBEFS that can achieve efficient wet removal of PM, indoor air humidification, formaldehyde removal, and antibacterial functions. By regulating the addition and particle size of the pore-forming agent, the pore size distribution can be adjusted to optimize the particulate removal efficiency. This study reveals the structure–activity relationship between pore structure, bubble characteristics, and removal performance, presenting experimental support for analyzing the capture mechanisms dominated by porous ceramics and gas–liquid interfaces. Furthermore, PCBEFS demonstrates excellent multifunctional synergy and regenerability. Its performance can be restored through simple ultrasonic cleaning, overcoming the water-wash resistance limitations of traditional HEPA materials. Simultaneously, the system exhibits distinct advantages in the coupled removal of particulate matter, gaseous pollutants, and microorganisms, offering a potential pathway for air purification to transition from single-filter approaches to multifaceted governance. Importantly, PCBEFS exhibits excellent scalability and engineering application potential. The proposed system enables flexible modular integration to adapt to varying spatial and air quality requirements owing to the high mechanical strength, low-cost fabrication processes, and diverse forming methods of porous ceramics. This feature distinguishes it from the existing liquid-based purification systems, addressing bottlenecks in mechanical stability, fabrication complexity, and large-scale application. Further optimization of pore structure and interfacial control presents considerable potential for enhancing the gas–liquid interface efficiency in PCBEFS. Coupling the proposed system with functional units such as photocatalysts or piezoelectric ceramics could evolve it into a multimodal air purification platform. This simple, renewable, and scalable porous-based bubble-enhanced purification strategy presents the potential to become an important technological pathway for improving the indoor air quality.

Methods

Materials

Al2O3 powder was purchased from Hebei Zhuyan Alloy Materials Co., Ltd. Glass powder was purchased from Foshan Youhe Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Natural graphite powder was purchased from Qingdao Huatai Lubrication and Sealing Technology Co., Ltd. Polyvinyl alcohol was purchased from Wuxi Yatai United Chemical Co., Ltd. Formaldehyde solution was purchased from Guangdong Kona Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. KMnO4 solution and H2SO4 solution were purchased from Guangzhou Howei Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. Escherichia coli (ATCC25922) was obtained from Guangzhou Biological Preservation Center. Gentamicin was purchased from Shanghai Ruichu Biotech Co., Ltd. SYTO-9 was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. PI was purchased from Beijing Solepol Science and Technology Co., Ltd. The liquid used in PCBEFS was tap water.

Preparation of porous ceramics

Porous ceramics were prepared using graphite as a pore-forming agent, alumina as an aggregate, polyvinyl alcohol solution of 5% mass fraction as a binder and glass powder as a sintering aid. Table 1 lists the proportions of the raw materials. The preparation process began with weighing each raw material and ball-milling for 12 h. Subsequently, the well-mixed powder was transferred to a mortar and pestle, where it was stirred and milled while a 5% mass fraction of polyvinyl alcohol solution was added drop-wise to achieve the required viscosity. The appropriate amount of powder was then weighed and placed into a round metal mold of diameter 50 mm. This mixture was then compacted into a green body with a thickness of 1.5 mm using a manual powder compactor at 58 MPa. The green body was dried in an oven at 110 °C for 12 h in air. Lastly, the green body was sintered in a muffle furnace with a temperature increase rate of 2.5 °C min−1, reaching a final temperature of 1150 °C for 3 h. Nine groups of samples were prepared using this method, with variations in the pore-forming agent additions and particle sizes.

Characterization

The microstructure of the samples was observed using field-emission SEM (FEI-NOVA NANO 230, USA). The pore size distribution was determined using the mercury intrusion porosimetry method (Micromeritics, AutoPore IV 9520, USA). The samples were cut into dimensions of 16 mm × 3 mm × 4 mm and tested for bending strength on a universal testing machine (UMT-5105, China) using the three-point bending method. The loading rate was set to 0.5 mm min−1 with a span of 16 mm. Five parallel samples were tested for each set, and the mean values were calculated. The apparent porosity of the samples was measured using the Archimedes’ principle, with deionized water used as the impregnation medium. The contact angle on the surface of the ceramic samples was tested using a contact angle meter (JC2000DM, China). A high-speed video camera (Revealer, M230M/C, China) with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 and a frame rate of 1000 fps was used to characterize the bubble generation and rise process on the porous ceramic surface. The photographs were analyzed using ImageJ software, and the equivalent bubble diameter was calculated as \(2\sqrt{A/\pi }\) where A is the projected area of an individual bubble in the image.

Air permeability testing

The relationship between the air penetration velocity and pressure drop gradient was determined using a custom-built device. The pressure gradient, \(\frac{dP}{dL}\), as air passes through the sample was calculated using Eq. (5). The air penetration velocity, \({v}_{s}\), through the sample was determined using Eq. (6).

where Pi denotes the inlet pressure; Po denotes the outlet pressure; P denotes the pressure at which the airflow rate is measured, which is represented by Po; and L denotes the thickness of the sample.

where Q denotes the volume flow rate of air and A denotes the contact area of the sample with the air.

Evaluation of PM removal performance

Relevant studies39 reported that dust-laden air produced by burning mosquito coils is relatively stable and has been widely used as a dust generator61,62,63. Therefore, burning mosquito coils (Zhongshan Lanju Daily Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., China) were selected as the dust generator for this study, which can provide air with PM2.5 mass concentrations exceeding 1000 μg m−3. Such air quality conditions are harsh for typical indoor environments and correspond to the “very bad” air quality level as designated by the Korean Ministry of Environment23,25, and far exceed the latest WHO target values of 5 μg m−3 for annual average and 15 μg m−3 for daily average64. Two identical dust meters (TSI, DustTrak 8530, USA) were used to monitor the PM2.5 mass concentrations before and after the system. These instruments were fully calibrated by the manufacturer prior to use to ensure matching accuracy. Pressures, Pi and Po, before and after the samples were recorded using a digital manometer (TSI, 5825, USA). An air compressor (Dayi, China) provided a stable air supply. The contact area of the porous ceramic with the gas was 10.18 cm2. The removal efficiency, η, of PM was calculated as follows:

where \({{{{\boldsymbol{C}}}}}_{{{{\bf{inlet}}}}}\) and \({{{{\boldsymbol{C}}}}}_{{{{\bf{outlet}}}}}\) denote the PM2.5 mass concentrations at the system inlet and outlet, respectively.

Regeneration by ultrasonic cleaning

The renewable performance of the samples was evaluated using an ultrasonic cleaning method. For comparison, we used a MERV 17 HEPA filter (Blueair, Sweden). Initially, the mass of the sample was recorded. The sample then underwent dust loading for 30 min at an air penetration rate of 5 cm s−1, followed by cleaning in an ultrasonic cleaner with distilled water at 40 kHz for 120 s at ambient temperature65,66,67. Subsequently, the samples were dried completely at 70 °C, reweighed, and subjected to another 30-min dust loading session. This cycle was repeated for six dust loadings and five ultrasonic cleanings, cumulating to 180 min of dust loading. Pressure drops were recorded 1 min after each dust loading session began and subsequently at 1 min intervals. This procedure was identical for both the HEPA filter and porous ceramics. If the moisture content of the sample, calculated using Eq. (8), was within ±3%, the sample was completely dry and ready for the next dust-loading phase.

where w denotes the moisture content of the sample, m0 denotes the original mass, and m1 denotes the mass after drying.

Humidity enhancement testing

Humidity enhancement testing was conducted in Xi’an, China, during both the winter and summer seasons. To increase the contact area between water and air, humidification tests were conducted using a modified PCBEFS device with a diameter of 11 cm. The PCBEFS was placed within a chamber measuring 35 cm × 35 cm × 60 cm (Supplementary Fig. S4). The dimensions of the chamber were selected for two main reasons68: first, the volume is sufficiently large to accommodate all the necessary testing equipment; second, it is compact enough to effectively capture and accurately measure the relative humidity of the air treated by the PCBEFS, while minimizing interference from external environmental factors. The air penetration rate of the PCBEFS was maintained at 5 cm s−1, and the water level height was set at 6 cm69. Three humidity probes, designated No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3, were installed 21 cm above the PCBEFS. These probes were aligned on the same plane that passes through the center axis of the chamber. Probe No. 2 was positioned directly above the center axis of the upper space of the chamber, and probe Nos. 1 and 3 were placed 9 cm to the left and right of probe No. 2, respectively. The relative humidity of the air treated by the PCBEFS was determined by averaging the readings obtained from these three probes over a test period of 30 min. During winter, the initial temperature of the chamber was 18.3 ± 0.3 °C with an initial relative humidity ranging between 30% and 35%. In the summer, the initial conditions were 26 ± 0.5 °C and a relative humidity between 55% and 60%. Before each test, the chamber door was opened to restore the temperature and relative humidity to these initial values.

Formaldehyde removal testing

A mixture of 0.1 M KMnO4 and 0.05 M H2SO4 was used as the functional liquid for formaldehyde removal. Formaldehyde gas was generated by volatilization of a formaldehyde solution with a volume fraction of 0.3% and delivered at 1.4 L min−1 using a micro air pump (Hilintec, D27M-BL4EC1, China), which could provide formaldehyde gas with a concentration stabilized at 0.5 to 0.7 mg m−3 to the PCBEFS. Real-time formaldehyde concentrations were detected by an air quality detector (Dretec, O-710WTDR, Japan). Additionally, a blank control experiment was conducted by replacing the functional liquid with an equal volume of tap water under the same operating conditions to evaluate the intrinsic formaldehyde removal capability of the system.

Antibacterial activity

Gram-negative Escherichia coli (ATCC25922) was selected as the indicator strain to evaluate the antimicrobial properties of PCBEFS by two-fold serial dilution in 96-well plates. E. coli was initially stored at 4 °C. Prior to the experiment, colonies were inoculated into LB liquid medium, precultured at 37 °C, and the concentration of the bacterial solution was adjusted to OD600 = 0.1 (corresponding to a concentration of approximately 108 CFU mL−1). Subsequently, the bacterial solution was diluted to 106 CFU mL−1 at a ratio of 1:100 for subsequent antimicrobial experiments. The 50 μg mL−1 gentamicin solution was mixed with LB liquid medium at a 1:1 ratio, and 200 μL was added to the first well of the 96-well plate. Next, 100 μL of LB liquid medium was added to each of the second to twelfth wells, and then diluted by two-fold serial dilution method. Subsequently, 100 μL of the diluted bacterial solution was added to each of the aforementioned twelve wells. followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. Three experimental groups were set according to this procedure. Gentamicin was replaced with tap water and three control groups were set up with the same process. One blank control group containing only bacterial solution and one group without bacterial addition containing only LB liquid medium were set up. Subsequently, the third well of liquid from the experimental and control groups was withdrawn, and the bacterial precipitate was collected after centrifugation; the bacterial precipitate was washed with sterile PBS solution. Staining working solutions were prepared (working concentration of 5 μg mL−1 for SYTO-9 and 2 μg mL−1 for PI), and 0.5 mL of the staining working solution was used to resuspend the precipitates, followed by incubation at 37 °C and protected from light for 15 min. The fluorescence images of the bacteria were then visualized using a laser confocal scanning microscope (Olympus FV1200). Additionally, we supplemented the antibacterial efficiency verification with the spread plate method to verify the reliability of the fluorescence image analysis results (Supplementary Note S5).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Hamra, G. B. et al. Outdoor particulate matter exposure and lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 906–911 (2014).

Morawska, L. et al. A paradigm shift to combat indoor respiratory infection. Science 372, 689–691 (2021).

Kwon, H. J. et al. Long-lifetime water-washable ceramic catalyst filter for air purification. Nat. Commun. 14, 520 (2023).

González-Martín, J., Kraakman, N. J. R., Pérez, C., Lebrero, R. & Muñoz, R. A state–of–the-art review on indoor air pollution and strategies for indoor air pollution control. Chemosphere 262, 128376 (2021).

Dominici, F., Greenstone, M. & Sunstein, C. R. Particulate matter matters. Science 344, 257–259 (2014).

Carotenuto, C., Di Natale, F. & Lancia, A. Wet electrostatic scrubbers for the abatement of submicronic particulate. Chem. Eng. J. 165, 35–45 (2010).

Chen, C., Zhao, B. & Yang, X. Impact of two-way air flow due to temperature difference on preventing the entry of outdoor particles using indoor positive pressure control method. J. Hazard. Mater. 186, 1290–1299 (2011).

Chen, C., Zhao, B., Zhou, W., Jiang, X. & Tan, Z. A methodology for predicting particle penetration factor through cracks of windows and doors for actual engineering application. Build. Environ. 47, 339–348 (2012).

Zhou, M. et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 394, 1145–1158 (2019).

Nel, A. Air pollution-related illness: effects of particles. Science 308, 804–806 (2005).

Chen, Y. et al. Roll-to-roll production of metal-organic framework coatings for particulate matter removal. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606221 (2017).

Gu, G. Q. et al. Triboelectric nanogenerator enhanced multilayered antibacterial nanofiber air filters for efficient removal of ultrafine particulate matter. Nano Res 11, 4090–4101 (2018).

Wang, Y., Lin, Z. & Zhang, W. Comparison of effects of particle charging, media characteristics, humidity and aerosols on loading performance of electret media. Build. Environ. 179, 106962 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Antifouling sandwich-structured electrospun nanofibrous membranes by integrating fluffy and hydrophobic layers for long-term airborne particulate matter segregation. Environ. Sci.: Nano 8, 3322–3330 (2021).

Chen, J.-P. et al. Preparation of transparent, amphiphobic and recyclable electrospun window screen air filter for high-efficiency particulate matters capture. J. Membr. Sci. 675, 121545 (2023).

Zhong, Z. et al. Unusual air filters with ultrahigh efficiency and antibacterial functionality enabled by ZnO nanorods. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 21538–21544 (2015).

Kang, Y., Low, Z.-X., Zou, D., Zhong, Z. & Xing, W. Multifunctional nanofibrous membranes for integrated air purification. Adv. Fiber Mater. 6, 1306–1342 (2024).

Lee, B.-K., Mohan, B. R., Byeon, S.-H., Lim, K.-S. & Hong, E.-P. Evaluating the performance of a turbulent wet scrubber for scrubbing particulate matter. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 63, 499–506 (2013).

Hu, S. et al. Experimental study of the dust-removal performance of a wet scrubber. Int J. Coal Sci. Technol. 8, 228–239 (2021).

Nie, W. et al. Study of spray atomization law and dust suppression effect of a wet dust catcher on a hydraulic support. Energy 305, 132296 (2024).

Lee, S. U., Lee, J. Y., Lee, S. H. & Jeon, G. W. A sustainable water vortex-based air purification for indoor air quality. Build. Environ. 243, 110610 (2023).

Kim, D. & Lee, S. J. Effect of water microdroplet size on the removal of indoor particulate matter. Build. Environ. 181, 107097 (2020).

Kim, D., Kim, J. & Lee, S. J. Effectual removal of indoor ultrafine PM using submicron water droplets. J. Environ. Manag. 296, 113166 (2021).

Kim, J., Kim, J. J. & Lee, S. J. Efficient removal of indoor particulate matter using water microdroplets generated by a MHz-frequency ultrasonic atomizer. Build. Environ. 175, 106797 (2020).

Kim, J., Kim, J. J., Park, S., Kim, J. & Lee, S. J. Electric charge effect of micro-droplets generated by electrospray atomization on removal of indoor fine particulate matter. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 14, 101711 (2023).

Jumlongkul, A. Water-based air purifier with ventilation fan system: a novel approach for cleaning indoor/outdoor transitional air during the pandemic. SN Appl. Sci. 4, 257 (2022).

Fermo, P. et al. Improving indoor air quality through an air purifier able to reduce aerosol particulate matter (PM) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs): Experimental results. Environ. Res. 197, 111131 (2021).

Koo, J., Hong, J., Lee, H. & Shin, S. Effects of the particle residence time and the spray droplet size on the particle removal efficiencies in a wet scrubber. Heat. Mass Transf. 46, 649–656 (2010).

Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Han, Y. & Hou, X. Liquid-based materials for air purification. Rev. Mater. Res. 1, 100072 (2025).

Yu, S. et al. Liquid–solid composites with confined interface behaviors. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwae423 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Continuous air purification by aqueous interface filtration and absorption. Nature 610, 74–80 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Biomimetic air purification with liquid-gating topological gradient microfluidics. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 650–660 (2024).

Jeong, S. et al. Human circulatory/respiratory-inspired comprehensive air purification system. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405568 (2024).

Johnston, I. D., McCluskey, D. K., Tan, C. K. L. & Tracey, M. C. Mechanical characterization of bulk Sylgard 184 for microfluidics and microengineering. J. Micromech. Microeng. 24, 035017 (2014).

Chen, Y., Wang, N., Ola, O., Xia, Y. & Zhu, Y. Porous ceramics: Light in weight but heavy in energy and environment technologies. Mater. Sci. Eng.: R: Rep. 143, 100589 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Design, fabrication, microstructure, and properties of highly porous alumina whisker foam ceramic. Ceram. Int. 48, 2776–2781 (2022).

Gong, Y., Zou, D., Zhong, Z. & Xing, W. High-performance mullite fibrous ceramic filter enhanced by composite sintering aids for dust-laden gas filtration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 292, 120967 (2022).

Hashimoto, K. et al. Effect of fine bubbles for washing of monolith type porous ceramic membranes treating oil-in-water emulsions. Chemosphere 305, 135487 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Novel low pressure drop and easy regeneration ceramic whisker membrane for submicron particulate matter filtration. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 43, 3849–3853 (2023).

Cuo, Z. et al. Highly porous fibrous mullite ceramic membrane with interconnected pores for high performance dust removal. Ceram. Int. 44, 11778–11782 (2018).

Okada, K. et al. Characteristics of microbubbles generated by porous mullite ceramics prepared by an extrusion method using organic fibers as the pore former. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 30, 1245–1251 (2010).

Sadatomi, M., Kawahara, A., Matsuura, H. & Shikatani, S. Micro-bubble generation rate and bubble dissolution rate into water by a simple multi-fluid mixer with orifice and porous tube. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 41, 23–30 (2012).

Xie, B. Q., Zhou, C. J., Sang, L., Ma, X. D. & Zhang, J. S. Preparation and characterization of microbubbles with a porous ceramic membrane. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif. 159, 108213 (2021).

Liu, C., Liang, B., Tang, S. & Min, E. Effects of Orifice orientation and gas-liquid flow pattern on initial bubble size. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 21, 1206–1215 (2013).

Lin, J., Zhang, Y., Guo, Z. & Du, H. Impact of synthetic fibers on spalling and intrinsic pore structure of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) under elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 439, 137325 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Micro-nano scale pore structure and fractal dimension of ultra-high performance cementitious composites modified with nanofillers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 141, 105129 (2023).

Tuncer, N., Arslan, G., Maire, E. & Salvo, L. Influence of cell aspect ratio on architecture and compressive strength of titanium foams. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 528, 7368–7374 (2011).

Xu, X. et al. Effect of preparation conditions on gas permeability parameters of porous SiC ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41, 3252–3263 (2021).

Han, F. et al. High gas permeability of SiC porous ceramics reinforced by mullite fibers. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 36, 3909–3917 (2016).

Wang, X., Xiang, H., Wang, G. & Zhou, Y. A green fabrication strategy for porous Yb3Al5O12 ceramics with high strength and tunable gas permeability. J. Mater. Res. 31, 3078–3087 (2016).

Wang, B. et al. Gas permeability and adsorbability of the glass-bonded porous silicon carbide ceramics with controlled pore size. Ceram. Int. 41, 2279–2285 (2015).

Simão, L., Caldato, R. F., Innocentini, M. D. M. & Montedo, O. R. K. Permeability of porous ceramic based on calcium carbonate as pore generating agent. Ceram. Int. 41, 4782–4788 (2015).

Pei, W. et al. SiC ceramic membranes for high-efficiency micron-sized bubble aeration. J. Membr. Sci. 731, 124240 (2025).

Pan, W., Chen, X., Dai, G. & Wang, F. Enhanced effect of bubble deformation on internal particle transport. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 905–918 (2020).

Zhang, H. & Yoshino, H. Analysis of indoor humidity environment in Chinese residential buildings. Build. Environ. 45, 2132–2140 (2010).

ASHRAE. 2016 ASHRAE Handbook: Heating, Ventilating, and Air-Conditioning Systems and Equipment. ASHRAE, Atlanta, USA (2016).

He, F., Weon, S., Jeon, W., Chung, M. W. & Choi, W. Self-wetting triphase photocatalysis for effective and selective removal of hydrophilic volatile organic compounds in air. Nat. Commun. 12, 6259 (2021).

He, F., Jeon, W. & Choi, W. Photocatalytic air purification mimicking the self-cleaning process of the atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 12, 2528 (2021).

Peng, L. et al. Bioinspired artificial spider silk photocatalyst for the high-efficiency capture and inactivation of bacteria aerosols. Nat. Commun. 14, 2412 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Metal-organic frameworks with photocatalytic bactericidal activity for integrated air cleaning. Nat. Commun. 10, 2177 (2019).

See, S. W. & Balasubramanian, R. Characterization of fine particle emissions from incense burning. Build. Environ. 46, 1074–1080 (2011).

Ji, X. et al. Characterization of particles emitted by incense burning in an experimental house. Indoor Air 20, 147–158 (2010).

Jung, C.-C., Syu, Z.-H., Su, H.-J., Lian, P.-Y. & Chen, N.-T. Stable C and N isotopes of PM2.5 and size-segregated particles emitted from incense stick and cigarette burning. Environ. Res. 212, 113346 (2022).

World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. WHO, Bonn, Germany (2021).

Gao, S., Wang, Z., Ren, T. & Zhang, Y. A combined mechanism (the open pores-cake dissolution) model for describing the trans-membrane pressure (P(t)) reduction in the backwash process at a constant flow rate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106871 (2021).

Kalboussi, N. et al. Optimal control of physical backwash strategy - towards the enhancement of membrane filtration process performance. J. Membr. Sci. 545, 38–48 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Ultrasonic-assisted acid cleaning of nanofiltration membranes fouled by inorganic scales in arsenic-rich brackish water. Desalination 377, 172–177 (2016).

Zhu, X., Lv, M. & Yang, X. Performance of sorption-based portable air cleaners in formaldehyde removal: Laboratory tests and field verification. Build. Environ. 136, 177–184 (2018).

Zhang, L., Cheng, G. & Gao, S. Experimental study on air bubbling humidification. Desalin. Water Treat. 29, 258–263 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research project was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China General Program (Grant No. 52178090), the National Natural Science Foundation of China General Program (Grant No. 51878533), the Outstanding Youth Science Foundation Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2024JC-JCQN-50), the Youth Innovation Team of Shaanxi Universities, the Science and Technology Project of Xi’an (22GXFW0018) and (2017071CG/RC034(SXSF002)) and the Shaanxi Provincial Technological Innovation Guidance Special (2023GXLH-051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G.L. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. J.K.R., R.G. and B.Y.S. performed the porous ceramics preparation and characterization experiments. J.K.R., A.T., Y.Y.W. and Y.B.G. recorded and processed the data. J.K.R. analyzed the data. J.K.R., R.G., T.O., Y.Z. and C.Q.Y. contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript and to the interpretation of the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Sukjoon Hong and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Philip Coatsworth, Ros Daw].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, J., Gao, R., Li, A. et al. Efficient air purification using porous ceramic-based bubble-enhanced filtration system. Commun Eng 5, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00559-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00559-3