Abstract

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) is a promising magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that provides molecular-level information in vivo. To obtain this unique contrast, repeated acquisition at multiple frequency offsets is needed, resulting a long scanning time. In this study, we propose a hybrid strategy at k-space and image domain to accelerate CEST MRI to facilitate its wider application. In k-space, we developed a complementary undersampling strategy which enforces adjacent frequency offsets by acquiring different subregions of k-space. Both Cartesian and spiral k-space trajectories were applied to validate its effectiveness. In the image domain, we developed a multi-offset transformer reconstruction network that uses complementary information from adjacent frequency offsets to improve reconstruction performance. Additionally, we introduced a data consistency layer to preserve undersampled k-space and a differentiable coil combination layer to leverage multi-coil information. The proposed method was evaluated on rodent brain and multi-coil human brain CEST images from both pre-clinical and clinical 3 T MRI scanners. Compared to fully-sampled images, our method outperforms a number of state-of-the-art CEST MRI reconstruction methods in both accuracy and image fidelity. CEST maps, including amide proton transfer (APT) and relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement (rNOE), were calculated. The results also showed close agreement with fully-sampled ones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Detecting molecular-level information in vivo to reveal tissue metabolism is of great interest in clinic1,2. As a relatively new MRI contrast, CEST can detect endogenous low-concentration molecules containing exchangeable protons, without the need to administer exogenous contrast agents3,4. Unlike standard MRI contrast that depends on the relaxation properties of water protons5,6, CEST originates from proton exchange between water and solute molecules7,8. As a spectrum-based method, CEST imaging applies a series of saturation pulses at varying frequency offsets to acquire multiple saturated images, which are then used to calculate Z-spectra. A chemical group with a certain resonance shift can be identified through a distinct signal drop in Z-spectra. A variety of endogenous CEST contrast agents have been studied, such as amide at 3.5 ppm9,10,11, amine at 2.75 ppm12,13,14, hydroxyl at 1.28 ppm15,16,17, and guanidinium at 2.0 ppm18,19,20 (ppm, parts per million). Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CEST MRI in mapping a wide range of proteins and metabolites, such as peptides21,22,23,24, lipids25,26,27, and glucose28,29,30. Therefore, CEST MRI has been applied to imaging molecular-level changes of many diseases, such as cancer31,32, stroke33,34,35, and neurodegenerative disorders35,36,37. Despite promising results, the wider application of CEST MRI is still hampered by its long scanning time38.

The total scan time of CEST MRI can be mathematically represented by39:

where TR is the repetition time, \({N}_{{{\rm{offs}}}}\) is the number of frequency offsets according to research needs, and \({N}_{{{\rm{shot}}}}\) is the number of imaging shots to fully sample k-space. The repetition time TR is determined by the length of the saturation pulse, acquisition time, and recovery time, and should have a longer duration than \({T}_{1}\) in order to prevent the loss of the saturation signal40. There have been many efforts in the literature to accelerate CEST MRI, primarily through the reduction of \({N}_{{{\rm{shot}}}}\). These methods can be divided into two categories: (1) undersampling k-space and (2) sampling k-space more efficiently through fast imaging sequences. Turbo spin echo (TSE) is a commonly used imaging sequence to acquire CEST images. Multiple refocusing pulses are applied after an excitation pulse to generate a train of echo signals. Because of the exponential decay of transverse magnetization, standard TSE is inefficient to cover the full k-space at a single shot without blurring artifacts41. Therefore, a variety of fast imaging sequences have been developed to improve the acquisition efficiency of CEST MRI, such as echo planar imaging (EPI)42,43,44, gradient echo (GRE)45,46, and steady state free precession (SSFP)47. For instance, Zaiss et al.45 proposed a gradient echo-based acquisition module to achieve snapshot CEST imaging. A rectangular spiral-centric reordered k-space trajectory is used to further improve image quality. While generally effective, fast imaging sequences are more susceptible to field inhomogeneity48 and introduce additional complexity in CEST MRI quantification49.

Undersampling k-space using conventional TSE sequences is another commonly used strategy to accelerate CEST MRI50. The limitations of fast imaging sequences could be alleviated. Since undersampling below the Nyquist rate introduces imaging artifacts, a retrospective reconstruction method is required to recover missing information. Conventional reconstruction methods, such as compressed sensing, exploit the sparsity underlying image space. A sparsifying operator, like the wavelet transform, is applied to iteratively optimize reconstructed images51. A major limitation of compressed sensing is the lengthy computation time for nonlinear optimization52, particularly in CEST MRI, which involves dozens of saturated images. Recently, deep learning-based reconstruction methods have been successfully applied to CEST MRI, showing improvements in both image quality and computational efficiency39,53,54,55. Deep neural networks such as U-Net56 and variational network57 are first optimized with sufficient training data, and then, taking undersampled images as input, the discriminative features underlying image space can be extracted to generate reconstructed images. For instance, Pemmasani Prabakaran et al.39 proposed a deep residual channel attention network to perform super-resolution of undersampled CEST images. A fixed Cartesian undersampling mask was used to acquire the center of k-space. Despite promising results, the inherent complementarity of CEST images is not fully explored. Besides, highly efficient non-Cartesian k-space trajectories are rarely considered in deep learning-based CEST MRI reconstruction.

In acquired CEST images along the frequency-offset dimension, the image intensity varies due to proton saturation and chemical exchange effects, while the structural information within the field-of-view (FOV) remains consistent. Therefore, there are massive redundancies within CEST data, which can be leveraged to accelerate CEST MRI without compromising image quality. Previous studies have demonstrated that frequency-offset-dependent k-space sampling patterns can improve downstream reconstruction performance58,59,60. These prompted us to propose a hybrid strategy to accelerate CEST MRI. Firstly, we introduce complementary undersampling in k-space, where each frequency-offset samples a distinct subregion while adjacent frequency offsets cover different subregions. We apply this complementary undersampling strategy to two commonly used k-space trajectories: the Cartesian trajectory and the non-Cartesian spiral trajectory. Secondly, we propose a multi-offset transformer reconstruction (MoTR) network to generate high-fidelity images. Figure 1 illustrates the diagram of the MoTR network. By utilizing the strength of the transformer module in modeling long-range feature dependencies61, each frequency offset can gather partial data from adjacent frequency offsets to compensate for missing information. Besides, the undersampled k-space is preserved in reconstructed images through a data consistency (DC) layer. A differentiable coil combination layer is also introduced, along with a two-step training strategy, to better utilize multi-coil information. The proposed method was evaluated using rodent brain and multi-coil human brain CEST images acquired from different centers. Multiple undersampling factors were examined, including \(3\times\) and \(6\times\) undersampling. Prospective spiral imaging was also conducted to assess real non-Cartesian data from the scanner. The experimental results demonstrated a better performance of the proposed method over a number of state-of-the-art CEST MRI reconstruction methods. Lorentzian difference analysis (LDA)62 was used to derive CEST contrasts. The resulting CEST maps also closely matched the fully sampled ones.

A Architecture of the MoTR network in the case of spiral and Cartesian k-space trajectories, respectively. B Details of the MoTR module. C, D Data consistency (DC) layer in the case of spiral and Cartesian trajectories, respectively. The DC layer in the case of a Cartesian trajectory is simplified because all trajectory points are on-grid. For multi-coil data, coil-wise reconstruction was performed, then a differentiable coil combination layer calculates coil-combined images.

Results

Rodent brain imaging with different acceleration rates

Normal rodent brain imaging was performed on a pre-clinical scanner, and a total of eight male C57BL/6 mice were used. We acquired 60 CEST scans with an echo-train-length (ETL) of 32 and 16 CEST scans with an ETL of 16. The ETL-32 CEST scans have \({N}_{{{\rm{shot}}}}\) of 3 and were used for 3\(\times\) undersampling. The ETL-16 CEST scans have \({N}_{{{\rm{shot}}}}\) of 6 and were used for 6\(\times\) undersampling. Out of 60 ETL-32 CEST scans, 48 were randomly selected for training and validation, while the remaining 12 were reserved for testing. For the ETL-16 CEST scans, four-fold cross-validation was performed. The k-space of each CEST scan was retrospectively undersampled via complementary undersampling. In the case of the Cartesian trajectory, for 3\(\times\)/6\(\times\) undersampling, 16/8 lines were sampled at the center of k-space, which concentrates most energy of the MRI signal. The remaining peripheral k-space was sampled by \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}\) adjacent frequency offsets in a cyclic manner. Therefore, \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}=5\)/\({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}=11\) adjacent frequency offsets were used to fully cover peripheral k-space for 3\(\times\)/6\(\times\) undersampling. In the case of a spiral trajectory, the leaf-length \(L\) was varied to simulate different undersampling factors, while \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}\) was kept at 6 in the experiments. We adopted a variable-density spiral sampling pattern63 and the gradient amplitude and slew rate limit were set to 8 G/cm and 90 G/cm/ms, respectively, resulting in a leaf-length \(L\) of 3185/1504 under 3\(\times\)/6\(\times\) undersampling.

We compared the reconstruction performance of the proposed method with a conventional compressed sensing-based method (CS-Wavelet50) and four deep learning-based reconstruction methods. Different methods use different k-space sampling patterns and network structures: (1) PROPELLER-CEST53 uses PROPELLER trajectory64 and U-Net for image reconstruction; (2) AMO-CEST55 designs a pseudo-radial trajectory and uses attention U-Net for image reconstruction; (3) DLSR-CEST39 samples center of k-space and uses a deep residual channel attention network65 for image reconstruction; (4) CEST-VN54 uses a data-sharing Cartesian trajectory and a variational network for image reconstruction. The number of trajectory points \(L\) was kept consistent across different methods to ensure the same undersampling factors.

The quantitative evaluation results for all compared methods are summarized in Table 1, which lists the average and standard deviation of PSNR and SSIM for both 3\(\times\) and 6\(\times\) undersampling. Our method outperforms all compared methods for both Cartesian and spiral k-space trajectories. In addition, we performed Wilcoxon signed-rank tests on both PSNR and SSIM results, yielding \(p\)-values of \(p\ll 0.0001\) for all compared methods, i.e., statistical significance. Figure 2 shows qualitative evaluation results of all compared methods. The reconstructed images and their corresponding error maps (relative to fully sampled images) are shown. The error maps are computed using the formula \(100 \% \times \left|\hat{x}-x\right|/{\max }_{95 \% }\left(x\right)\), where \(\hat{x}\) represents the reconstructed images, and \(x\) denotes the fully sampled images. All error maps are displayed using the same color scale. Our method achieves higher consistency to fully sampled images, with enhanced image fidelity and fewer structural distortions visible in error maps.

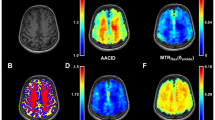

Figure 3 displays Z-spectra derived from fully sampled and reconstructed CEST images. The reference spectra \({Z}_{{{\rm{ref}}}}\), Z-spectra \({Z}\), and Lorentzian difference spectra \(\Delta Z\) are plotted using dotted, solid, and dashed lines, respectively. Two representative regions of interest, i.e., the cortex and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), are analyzed, and the residuals between fully sampled and reconstructed Z-spectra are plotted for comparison. The reconstruction error remains below 0.5% across most frequency offsets; however, elevated errors occur near 0 ppm, potentially due to the rapidly varying image intensities in this region. Figure 4 displays two CEST maps: amide proton transfer (APT) and relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement (rNOE). APT, derived from \(\Delta Z\) at 3.5 ppm, reflects amide group distribution, while rNOE, obtained from \(\Delta Z\) at −3.5 ppm, detects macromolecules such as membrane lipids66,67. CEST maps from our method exhibit strong agreement with the fully sampled ones.

(a) and (d) display a grayscale image and regions of interest to extract Z-spectra. (b) and (e) display Z-spectra from the CSF region, while panels (c) and (f) display those from the cortex region. The dotted line, solid line, and dashed line represent reference spectra, Z-spectra, and Lorentzian difference spectra, respectively.

Aside from simulated spiral trajectory out of Cartesian k-space data, we also performed prospective spiral imaging on the same pre-clinical scanner. Five spiral CEST scans were acquired, each of which consists of 6 interleaves. A \(3\times\) complementary undersampling scheme was applied with \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}=3\). Five-fold cross-validation was performed, with no simulated data used for training. On prospectively acquired spiral images, representative reconstruction results and corresponding CEST maps are displayed in Fig. 5. Only the foreground region was included to evaluate the reconstruction performance. Our method achieved SSIM and PSNR values of \(0.9796\pm 0.0285\) and \(40.2978\pm 1.4111\), respectively, outperforming zero-filled reconstruction (\(0.8020\pm 0.0233\) and \(21.9895\pm 1.1696\)). The results demonstrate excellent agreement with fully sampled data, indicating that our method generalizes well to non-Cartesian acquisitions on the scanner.

Rodent brain imaging with pathologies

A total of 12 CEST scans were acquired from tumor-bearing rodents on the pre-clinical scanner. All CEST scans were randomly divided into training and testing sets at a 3:1 ratio. The 3\(\times\) undersampling was performed using a Cartesian trajectory, while all other experimental settings matched those of the normal rodent brain study. Compared to fully sampled images, zero-filled images had a low quality (SSIM: \(0.8288\pm 0.0488\); PSNR: \(27.3578\pm 3.7827\)). In contrast, our method demonstrated a superior reconstruction performance (SSIM: \(0.9790\pm 0.0276\); PSNR: \(37.6490\pm 4.692\)). To evaluate generalization ability, we applied our model (trained exclusively on normal brain images) to tumor-bearing testing cases. The reconstructed tumor images maintained high fidelity (SSIM: \(0.9795\pm 0.0279\); PSNR: \(37.5641\pm 4.5304\)). Therefore, our method can generalize well to unseen pathologies, even when the scan parameters are different. Figure 6 displays qualitative evaluation results. We used Ours (T) to represent the model trained exclusively on tumor brain images and used Ours (N) to indicate the model trained solely on normal brain images. Zero-filled images exhibited strong aliasing artifacts at 3\(\times\) undersampling, while images reconstructed by our method closely resemble the fully sampled ones. We observed a decrease in APT and rNOE signals around tumor regions compared to the contralateral side, suggesting a distinct chemical environment. These subtle signal changes remained detectable in our reconstructed images, demonstrating the high sensitivity of the proposed method.

Human brain imaging with different acceleration rates

Five CEST scans were acquired on the clinical MRI scanner, and reconstruction performance was evaluated via five-fold cross-validation. Similar to the rodent brain study, here we performed \(3\times\) and \(6\times\) undersampling, which was applied to the k-space of each individual coil. For \(3\times\) and \(6\times\) complementary undersampling, 16 and 8 central k-space lines were densely sampled, respectively, while the peripheral k-space was covered by \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}=5\) and \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}=11\) adjacent frequency offsets in a cyclic manner. All other parameters, including the comparative deep learning methods, remained consistent with those used in the rodent brain study. Because of the long computation time and low reconstruction performance, CS-Wavelet was excluded from the human brain study. For each comparative method except CEST-VN, reconstruction was performed on individual coil data rather than on coil-combined images. Coil-sensitivity maps were estimated from reconstructed k-space using ESPIRiT68. Final coil-combined images were generated using the SENSE algorithm69. CEST-VN here followed the original multi-coil implementation.

Quantitative evaluation results are summarized in Table 2, including mean and standard deviation values for both PSNR and SSIM metrics. Our method significantly outperforms all compared methods by a large margin (\(p\) ≪ 0.0001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Figure 7 displayed representative saturated images and corresponding CEST maps at 6\(\times\) undersampling. According to error maps, our method yields more consistent results for fully sampled images. Figure 8 presented reconstructed images from the 5th and 15th receiver coils at 6\(\times\) undersampling. Individual coil images exhibited relatively low SNR and strong signal intensity decay with increasing distance to the receiver coil. Our method demonstrates better image fidelity. In this work, a two-step training strategy was proposed to effectively leverage multi-coil information. During pretraining, our method was trained on individual coil data, achieving SSIM/PSNR values of \(0.9815\pm 0.0547\)/\(40.7928\pm 1.8572\) (\(3\times\) undersampling) and \(0.9634\pm 0.0914\)/\(37.8063\pm 1.0193\) (\(6\times\) undersampling). In the finetuning stage, we incorporated a differentiable coil combination layer to further optimize the output coil-combined images. This multi-coil refinement stage provides additional performance gains beyond the individual coil results, achieving SSIM/PSNR values of \(0.9825\pm 0.0128\)/\(43.8960\pm 1.8080\) (\(3\times\) undersampling) and \(0.9652\pm 0.0365\)/\(41.0399\pm 1.0433\) (\(6\times\) undersampling).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated a hybrid strategy to accelerate CEST MRI, combining k-space domain complementary undersampling and image-domain deep learning-based multi-offset transformer reconstruction. We investigated the effects of different k-space trajectories and various undersampling factors, and evaluated our method on normal and tumor-bearing rodent brain data and multi-coil human brain data. Prospective spiral imaging was also performed. The results from the rodent brain study showed that deep learning-based reconstruction outperforms conventional compressed sensing. Performance also varies among different deep learning approaches. DLSR-CEST and PROPELLER-CEST neglect data consistency during reconstruction. Although data sharing and multi-coil information were incorporated in CEST-VN, the variational network is slow to train and is limited in extracting feature dependency. While AMO-CEST demonstrates good performance in human brain study, its sampling pattern is a Cartesian mask with pseudo-radial appearance, which differs fundamentally from the real radial trajectory in the scanner.

Unlike structural MRI, CEST MRI relies on the intensity value of each pixel to determine molecular information. In this work, unsaturated images were kept fully sampled to ensure accurate normalization of Z-spectra. CEST effects are typically of small magnitude, posing great challenges for image reconstruction. In the rodent brain study, the reconstructed images from our method showed high consistency with fully sampled ones, yielding high-quality CEST maps. In the human brain study, the reconstructed APT and rNOE maps exhibited slight deviations from fully sampled ones at \(6\times\) undersampling. Since CEST effects are calculated from the entire Z-spectrum, the reconstruction errors will accumulate across all frequency offsets. The reconstruction performance is also influenced by k-space sampling patterns. CS-Wavelet, DLSR-CEST, and CEST-VN use a Cartesian trajectory, while PROPELLER-CEST and AMO-CEST employ a non-Cartesian trajectory. Undersampling with a Cartesian trajectory typically introduces aliasing artifacts, while non-Cartesian undersampling leads to incoherent aliasing artifacts and off-resonance-induced blurring, but more details can be preserved. The compared deep learning approaches still exhibit blurring effects, particularly in human brain studies. Our method, in contrast, delivered sharper reconstruction with better image fidelity, suggesting more effective recovery of the missing k-space signal. We also evaluated our method on simulated spiral k-space in a rodent brain study, and it demonstrated comparable reconstruction performance to the Cartesian k-space. In prospective spiral imaging, the reconstructed images and CEST maps also closely matched the fully sampled ones, but the performance is inferior to the simulated spiral k-space, as evidenced by error maps. Such discrepancy mainly stems from imaging-related factors: there are gradient imperfections in the acquired spiral k-space (Fig. S2B).

The proposed method consists of three major components: the complementary undersampling scheme, the MoTR module, and the data consistency (DC) layer. To validate the effectiveness of each component, we conducted an ablation study on normal rodent brain data. Since the transformer layer is the core of the MoTR module, in the ablation analysis, we removed it to study the effectiveness of the MoTR module. When the complementary undersampling scheme was omitted, all input frequency offsets shared the same k-space trajectory. The ablation results in Table 3 demonstrate that removing any component degrades the reconstruction performance. At high undersampling factors, input images are highly blurred, necessitating reliance on the original k-space information (via the DC layer) and complementary information from adjacent frequency offsets (via the MoTR module) to achieve high-fidelity reconstruction.

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed method, we trained the reconstruction network on normal rodent brain images using different proportions of the training set (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%). The experimental results are plotted in Fig. 9A. We observed that even with limited training data, the reconstruction performance is still close to the model trained on the full training set. The SSIM of reconstructed images barely drops, but the standard deviation of PSNR increases, suggesting a relatively unstable reconstruction quality with limited training data. Additionally, to assess the robustness against imaging noise, we added different levels of white Gaussian noise to the undersampled k-space according to the formula \(\hat{k}=k+\eta * {{\rm{rdm}}}\), where \(k\) is the undersampled k-space, \(\eta\) is the noise level, and \({{\rm{rdm}}}\) denotes a normally distributed random function. The experiment was conducted on normal rodent brain data, with the network trained on noise-free images. The evaluation results are plotted in Fig. 9B and Fig. 9C. We found that under small to moderate noise levels (\(\eta \le 0.001\)), the reconstruction performance remains stable.

A Reconstruction performance with varying amounts of training data. B Reconstruction performance under different noise levels. C Example input (zero-filled) and output (reconstructed) images across the tested noise conditions. The statistical analysis was performed on CEST scans of the mouse brain (n = 12). The box plots show the mean, median, lower and upper quartiles, and the minimum and maximum values.

Methods

In CEST MRI, saturated images were sequentially acquired by varying the frequency offset of the saturation pulse. Let \(x\in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{{N}_{{{\rm{offs}}}}\times H\times W}\) be complex-valued saturated images to be reconstructed, where \(H\) and \(W\) are the height and width of each image, and given the undersampled k-space data \(y\in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{{N}_{{{\rm{offs}}}}\times L}\left(L\ll H\times W\right)\), our goal is to reconstruct \(x\) from \(y\) by solving the constrained optimization problem51:

where \(A\) is the Fourier undersampling operator and \(R\) is the regularization term. In this work, we formulate \(A\) as complementary undersampling and \(R\) as a multi-offset transformer reconstruction (MoTR) network, with details given in the following subsections.

Complementary undersampling

The saturated images \(x\) were acquired sequentially by circulating a complementary undersampling pattern. In this work, complementary undersampling is applied to both Cartesian and spiral trajectories. A diagram illustrating a complementary undersampling pattern is provided in Fig. S1.

In the case of a Cartesian trajectory, the Fourier undersampling operator \(A=M{{\mathscr{F}}}\), where \(M\) is a binary undersampling mask, and \({{\mathscr{F}}}\) is the fast Fourier transform (FFT). In complementary undersampling, \(M=\{{M}_{n}{|n}=1,\ldots ,{N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}\}\) subjects to \({\bigcup }_{n=1}^{{N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}}{M}_{n}=\Omega\) and \({\bigcap }_{n=1}^{{N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}}{M}_{n}=C\), where \(\Omega\) represents full k-space, and \(C\) represents center k-space. For a non-Cartesian trajectory, the trajectory points are mostly off-grid, therefore cannot be represented by a mask like \(M\). In this case, \(A\) is formulated as a non-uniform fast Fourier transform (NUFFT)70:

where \({{{\mathscr{F}}}}_{s}\) is FFT with an oversampling factor \(s\), \(k\) is the k-space trajectory, and \({{\mathscr{G}}}\) is a k-space interpolator to estimate values of trajectory points. For each frequency offset, the k-space trajectory starts at the origin and spirals to the edge of k-space, following an Archimedean design71:

where \({k}_{\max }\) indicates the maximum radius of the spiral, which is determined by the desired image size and FOV, \(N\) is the number of turns of the spiral, \(\theta \left(t\right)\) describes the azimuthal trajectory sweep, and its value increases monotonously from 0 to 1. The design of \(\theta \left(t\right)\) is governed by constraints of slew rate limit \({S}_{0}\) and amplitude limit \({G}_{\max }\) of the gradient system:

In this work, we adopt a Gaussian-weighted variable-density spiral trajectory63, and \(\theta \left(t\right)\) is solved through the above differential equations by iterative means72. For complementary undersampling, the spiral trajectory is rotated by \(\alpha =\frac{2\pi }{{N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}}\) when going to the next frequency offset. Therefore, the \(n\)-th k-space trajectory can be parameterized by:

Multi-offset transformer reconstruction network

Using the gradient descent algorithm, the reconstructed images \(x\) can be iteratively optimized by:

Similar to the variational network57, we unroll \(K\) update steps in the gradient descent algorithm and convert it to a deep neural network with \(K\) iterative blocks, as shown in Fig. 1. The core component of each iterative block is a data consistency (DC) layer and a MoTR module, corresponding to the second and third term in Eq. (2).

Due to the difference in the Fourier undersampling operator \(A\) between Cartesian and spiral trajectories, the design of the DC layer varies for the two cases. As shown in Fig. 1C, for the spiral trajectory, the k-space of reconstructed images is first oversampled by zero-padding the image space. The off-grid trajectory points are then interpolated using a Kaiser-Bessel kernel73. Next, a gridding operator maps the residual between the interpolated and undersampled k-space to grid points, so that a residual image can be calculated via inverse FFT (iFFT). Finally, this residual image is subtracted from the reconstructed image to enforce data consistency. For a Cartesian trajectory, since sampling points are on-grid, data consistency can be greatly simplified. Specifically, the undersampled k-space is used to directly replace the reconstructed k-space at the sampling locations. As illustrated in Fig. 1D, the undersampling mask \(M\) is inverted and multiplied by the reconstructed k-space. The undersampled k-space is then added back to directly form data-consistent images. For multi-coil images, we employ a two-step training strategy to better leverage multi-coil information. During pretraining, the reconstruction network is trained on individual coil images. Because of numerous receiver coils, this single-coil strategy benefits from an expanded training set compared to training on coil-combined images. In the finetuning stage, we incorporate a differentiable coil combination layer at the network output to calculate coil-combined images. The coil-sensitivity maps were derived from the individual coil reconstruction at the pretraining stage, as these images already reflect the relative signal weighting of each coil. Within the coil combination layer, coil-combined images were computed through a weighted sum of individual coil images, where the weighting factors were the complex conjugate of coil-sensitivity maps.

The idea of the MoTR module is to recover missing information in each undersampled CEST image by fusing complementary information from its adjacent images. As shown in Fig. 1B, the MoTR module is composed of feature embedding, self-attention, and feature mapping layers. It accepts \({N}_{{{\rm{adj}}}}\) undersampled images as input and outputs corresponding reconstructed images. Feature embedding layer projects all CEST images onto the underlying feature space through a convolution layer, resulting in an embedding feature \({X}_{{{\rm{in}}}}\) of size \({H}\times {W}\times C\). In self-attention layer, \({X}_{{{\rm{in}}}}\) is first flattened and then input into three different fully connected (FC) layers \({W}^{Q}\), \({W}^{K}\), and \({W}^{V}\) to get query(\(Q\)), key(\(K\)), and value(\(V\)) features of size \({HW}\times {D}\). Then features \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) are divided into 8 heads to perform multi-head self-attention61, resulting in fused features \({X}_{{{\rm{out}}}}\) of size \({H}\times {W}\times {C}\):

where \(\sigma\) is a learnable scaling factor. Benefiting from this self-attention mechanism, the feature dependency of adjacent CEST images can be established. In the feature mapping layer, \({X}_{{{\rm{out}}}}\) is processed by another convolution layer to generate reconstructed images. The reconstruction network is trained in an end-to-end manner using fully sampled images as ground truth by \(l1\)-norm loss. The number of iterative blocks \(K\) is set to 6, the weight \(\lambda\) is set to 1, and the embedding feature dimensions \(C\) and \(D\) are set to 16 and 512, respectively. The reconstruction network was implemented using the PyTorch library and was trained on an RTX4090 GPU with 64GB of system memory. NUFFT-related operations were implemented using the software package torchbknufft74. The complex-valued image was regarded as a dual-channel tensor during reconstruction. During training, we utilized Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, batch size of 8, and the number of training epochs was set to 30 to prevent overfitting. The training time, inference time, and the number of network parameters are given in Table S1. To quantify reconstruction performance, we adopted two evaluation metrics, i.e., structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR).

Lorentzian difference analysis

A major advantage of CEST MRI is its ability to resolve molecular-level information within tissues. A CEST scan is acquired with dozens of frequency offsets and needs post-processing to extract molecular-level information. In this work, we adopt Lorentzian difference analysis (LDA) to calculate CEST maps. After data acquisition, the Z-spectra are first calculated by:

where \(\Delta \omega\) is the frequency offset, \({M}_{{{\rm{sat}}}}\) is the saturated image, and \({M}_{0}\) is the unsaturated image. The Lorentzian difference analysis involves two steps. Firstly, a Z-spectrum is fitted with a Lorentzian line to derive reference spectrum \({Z}_{{{\rm{ref}}}}\), which reflects direct water saturation:

where \(a\) and \(\Gamma\) are the water peak amplitude and its full-width-at-half-maximum, and \(\delta\) is the water peak shift due to \({B}_{0}\) inhomogeneity. The initial values and boundary conditions for Lorentzian fitting are given in Table S2. Then, the fitted reference spectrum subtracts Z-spectrum to get Lorentzian difference spectrum \(\Delta Z\):

Normal rodent brain imaging

CEST data were acquired on a horizontal bore 3 T Bruker BioSpec system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with an 82 mm quadrature volume resonator as transmitter and a single surface coil as receiver. Eight male C57BL/6 mice were used in this study. The animal experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee and followed the institutional guidelines of the Institutional Laboratory Animal Research Unit of City University of Hong Kong. Each mouse was initially anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and maintained with 1−1.5% isoflurane in concentrated oxygen. A warming pad connected to a water-heating system (Thermo Scientific) was used to maintain the mouse body temperature at 37 °C. Respiration was continuously monitored using an MRI-compatible monitor system (SA Instruments). The CEST sequence was composed of a continuous-wave (CW) saturation pulse and a TSE acquisition module. The saturation power was set to 0.6/1.2 \({{\rm{\mu }}}\)T, the saturation time was set to 3 s, and 95 saturation frequency offsets ranging from −20 to 20 ppm were acquired. The step size was 0.25 ppm within −10 to 10 ppm and 1.0 ppm elsewhere. Three unsaturated images at a frequency offset of −300 ppm were acquired separately. Other scanning parameters were set as follows: repetition time (TR) = 5 s, echo time (TE) = 10 ms, FOV = 16 \(\times\)16 mm2, image size = 96 \(\times\)96, slice thickness = 1.5 mm. Five mice were scanned at an ETL of 32, and a total number of 60 CEST scans were acquired. Each CEST scan contains 95 saturated images corresponding to 95 frequency offsets. The total scan time for a complete CEST scan was 24 min. The rest three mice were scanned at an ETL of 16, and 16 CEST scans with a total of 1520 saturated images were acquired. The total scan time per CEST scan was 48 min.

Apart from Cartesian k-space sampling with TSE readout, prospective spiral imaging was also performed on the same pre-clinical scanner. Five male C57BL/6 mice aged 12 weeks were used. The animal experiment was approved by the local animal ethics committee. CEST imaging was performed using a single-slice SPIRAL readout in FID mode with the following scan parameters: flip angle = 60°, TR/TE = 3000/1.54 ms, slice thickness = 2 mm, FOV = 25 \(\times\)25 mm2, matrix size = \(96\times 96\), \({B}_{1}=0.8\,{{\rm{\mu }}}T\), \({T}_{{\mathrm{sat}}}=2\,{{\rm{s}}}\). The gradient coil has a maximum gradient strength of 450 mT/m and a maximum slew rate of 4200 T/m/s. For spiral imaging, the gradient limit and slew rate limit were set to 19.5% and 90%, respectively, with 6 interleaves (1352 points per leaf). The total scan time per CEST scan was 30 m 18 s. The spiral trajectory and corresponding gradient waveform are shown in Fig. S2A. The real k-space trajectory was calculated using a vendor-provided function that determines k-space positions from the phases of multiple FID signals. Five CEST scans were acquired, each containing 99 saturated images spanning −20 ppm to 20 ppm.

Pathological rodent brain imaging

All animal experiments were approved by the Department of Health (DH) of Hong Kong and complied with the Regulation of Animals (Control of Experiments) Ordinance. Twelve NOD-SCID (6–8 weeks) mice were anesthetized using 1–1.5% isoflurane in oxygen at 1–1.5 L/min and injected with U87 MG glioma cells. For cell inoculation, a cell with a density of 0.5 million/3 \({{\rm{\mu }}}\)L using a Hamilton airtight syringe (10 \({\mathrm{\mu L}}\)) was injected with a flow rate of 0.3 \({\mathrm{\mu L}}\)/min. The injection coordinates were 2.0 mm lateral, 0.2 mm anterior to the bregma, and 3.8 mm deep. All tumor-bearing mice were scanned two weeks post-inoculation when tumor volume reached approximately 2 mm3. CEST imaging was performed on the 3 T Bruker Biospec system using the following scan parameters: \({B}_{1}=0.8\,{\mathrm{\mu T}}\), \({T}_{{\mathrm{sat}}}=3\,{{\rm{s}}}\), TR/TE = 5000/5.9 ms, slice thickness = 1 mm, matrix size = 96 \(\times\)96, FOV = 18 \(\times\)18 mm2, and ETL = 32. The number of frequency offsets was 97, ranging from −15 ppm to 15 ppm, and a total of 12 CEST scans were acquired. The total scan time for a complete CEST scan was 24min15s.

Healthy human brain imaging

The human brain study was approved by the institutional review board of Zhejiang University and conducted according to guidelines. The MRI scanning was performed on a 3 T MRI scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Three healthy volunteers were involved, and informed consent was obtained from all volunteers prior to scanning. The CEST sequence was acquired with a single-slice TSE readout using a 20-channel head array coil. The saturation module consists of a train of 10 Gaussian pulses, each with a duration of 100 ms and a saturation power of 2 \({\mathrm{\mu T}}\). The scan parameters were as follows: flip angle = \(90^\circ\), TE = 6.7 ms, TR = 3000 ms, slice thickness = 5 mm, FOV = 212 \(\times\)186 mm2, matrix size = 96 \(\times\)96. Five CEST scans were acquired, each containing 63 saturated images covering frequency offsets from −6 ppm to 6 ppm.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code of our method is made publicly available at https://github.com/hb-liu/cest-cu.

References

Weissleder, R. Molecular imaging in cancer. Science 312, 1168–1171 (2006).

Pysz, M. A., Gambhir, S. S. & Willmann, J. K. Molecular imaging: current status and emerging strategies. Clin. Radiol. 65, 500–516 (2010).

Van Zijl, P. C. & Yadav, N. N. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn. Reson. Med. 65, 927–948 (2011).

Ward, K., Aletras, A. & Balaban, R. S. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J. Magn. Reson. 143, 79–87 (2000).

Katti, G., Ara, S. A. & Shireen, A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–a review. Int. J. Dent. Clin. 3, 65–70 (2011).

Tóth, É., Helm, L. & Merbach, A. E. Relaxivity of MRI contrast agents. In Contrast Agents I: Magnetic Resonance Imaging 61−101 (Springer, 2002).

Vinogradov, E., Sherry, A. D. & Lenkinski, R. E. CEST: from basic principles to applications, challenges and opportunities. J. Magn. Reson. 229, 155–172 (2013).

Wu, B. et al. An overview of CEST MRI for non-MR physicists. EJNMMI Phys. 3, 1–21 (2016).

Jones, C. K. et al. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magn. Reson. Med. 56, 585–592 (2006).

Togao, O. et al. Amide proton transfer imaging of adult diffuse gliomas: correlation with histopathological grades. Neuro Oncol. 16, 441–448 (2014).

Zhou, J. et al. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn. Reson. Med. 50, 1120–1126 (2003).

Desmond, K. L., Moosvi, F. & Stanisz, G. J. Mapping of amide, amine, and aliphatic peaks in the CEST spectra of murine xenografts at 7 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 71, 1841–1853 (2014).

Sun, C., Zhao, Y. & Zu, Z. Validation of the presence of fast exchanging amine CEST effect at low saturation powers and its influence on the quantification of APT. Magn. Reson. Med. 90, 1502–1517 (2023).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. CEST imaging of fast exchanging amine pools with corrections for competing effects at 9.4 T. NMR Biomed. 30, e3715 (2017).

Yao, J., Wang, C. & Ellingson, B. M. Influence of phosphate concentration on amine, amide, and hydroxyl CEST contrast. Magn. Reson. Med. 85, 1062–1078 (2021).

He, H. et al. Detection and chiral recognition of α-hydroxyl acid through 1H and CEST NMR spectroscopy using a ytterbium macrocyclic complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 18286–18289 (2019).

Jin, T. & Kim, S. G. Advantages of chemical exchange-sensitive spin-lock (CESL) over chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) for hydroxyl–and amine–water proton exchange studies. NMR Biomed. 27, 1313–1324 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. The exchange rate of creatine CEST in mouse brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 90, 373–384 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. Creatine mapping of the brain at 3T by CEST MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 91, 51–60 (2024).

Kumar, D. et al. Recovery kinetics of creatine in mild plantar flexion exercise using 3D creatine CEST imaging at 7 Tesla. Magn. Reson. Med. 85, 802–817 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat. Med. 9, 1085–1090 (2003).

Wen, Z. et al. MR imaging of high-grade brain tumors using endogenous protein and peptide-based contrast. Neuroimage 51, 616–622 (2010).

Jia, G. et al. Amide proton transfer MR imaging of prostate cancer: a preliminary study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 33, 647–654 (2011).

Huang, J. et al. Deep neural network based CEST and AREX processing: Application in imaging a model of Alzheimer’s disease at 3 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 87, 1529–1545 (2022).

Jones, C. K. et al. Nuclear overhauser enhancement (NOE) imaging in the human brain at 7 T. Neuroimage 77, 114–124 (2013).

Zhou, I. Y. et al. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI of glioma using Image Downsampling Expedited Adaptive Least-squares (IDEAL) fitting. Sci. Rep. 7, 84 (2017).

Goerke, S. et al. Relaxation-compensated APT and rNOE CEST-MRI of human brain tumors at 3 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 82, 622–632 (2019).

Chan, K. W. et al. Natural D-glucose as a biodegradable MRI contrast agent for detecting cancer. Magn. Reson. Med. 68, 1764–1773 (2012).

Huang, J. et al. Sensitivity schemes for dynamic glucose-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to detect glucose uptake and clearance in mouse brain at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 35, e4640 (2022).

Zhang, S., Trokowski, R. & Sherry, A. D. A paramagnetic CEST agent for imaging glucose by MRI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 15288–15289 (2003).

Paech, D. et al. Assessing the predictability of IDH mutation and MGMT methylation status in glioma patients using relaxation-compensated multipool CEST MRI at 7.0 T. Neuro Oncol. 20, 1661–1671 (2018).

Jiang, S. et al. Predicting IDH mutation status in grade II gliomas using amide proton transfer-weighted (APTw) MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 78, 1100–1109 (2017).

Zaiss, M. et al. Inverse Z-spectrum analysis for spillover-, MT-, and T1-corrected steady-state pulsed CEST-MRI–application to pH-weighted MRI of acute stroke. NMR Biomed. 27, 240–252 (2014).

Tietze, A. et al. Assessment of ischemic penumbra in patients with hyperacute stroke using amide proton transfer (APT) chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. NMR Biomed. 27, 163–174 (2014).

Lai, J. H. et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging for longitudinal assessment of intracerebral hemorrhage and deferoxamine treatment at 3T in a mouse model. Stroke 54, 255–264 (2023).

Pépin, J. et al. In vivo imaging of brain glutamate defects in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neuroimage 139, 53–64 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. Relayed nuclear Overhauser effect weighted (rNOEw) imaging identifies multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 32, 102867 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Acquisition sequences and reconstruction methods for fast chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging. NMR Biomed. 36, e4699 (2023).

Pemmasani Prabakaran, R. S. et al. Deep-learning-based super-resolution for accelerating chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 37, e5130 (2024).

Zaiss, M. & Bachert, P. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and MR Z-spectroscopy in vivo: a review of theoretical approaches and methods. Phys. Med. Biol. 58, R221 (2013).

Li, Z. et al. Sliding-slab three-dimensional TSE imaging with a spiral-in/out readout. Magn. Reson. Med. 75, 729–738 (2016).

Mueller, S. et al. Whole brain snapshot CEST at 3T using 3D-EPI: aiming for speed, volume, and homogeneity. Magn. Reson. Med. 84, 2469–2483 (2020).

Ellingson, B. M. et al. pH-weighted molecular MRI in human traumatic brain injury (TBI) using amine proton chemical exchange saturation transfer echoplanar imaging (CEST EPI). Neuroimage Clin. 22, 101736 (2019).

Akbey, S. et al. Whole-brain snapshot CEST imaging at 7 T using 3D-EPI. Magn. Reson. Med. 82, 1741–1752 (2019).

Zaiss, M., Ehses, P. & Scheffler, K. Snapshot-CEST: optimizing spiral-centric-reordered gradient echo acquisition for fast and robust 3D CEST MRI at 9.4 T. NMR Biomed. 31, e3879 (2018).

Dixon, W. T. et al. A multislice gradient echo pulse sequence for CEST imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 63, 253–256 (2010).

Kim, B., So, S. & Park, H. Optimization of steady-state pulsed CEST imaging for amide proton transfer at 3T MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 81, 3616–3627 (2019).

Morgan, P. S. et al. Correction of spatial distortion in EPI due to inhomogeneous static magnetic fields using the reversed gradient method. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 19, 499–507 (2004).

Wang, K. et al. Guanidinium and amide CEST mapping of human brain by high spectral resolution CEST at 3 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 89, 177–191 (2023).

Heo, H. Y. et al. Accelerating chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI by combining compressed sensing and sensitivity encoding techniques. Magn. Reson. Med. 77, 779–786 (2017).

Lustig, M., Donoho, D. & Pauly, J. M. Sparse MRI: the application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 58, 1182–1195 (2007).

Feng, L. et al. Compressed sensing for body MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 45, 966–987 (2017).

Guo, C. et al. Fast chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging based on PROPELLER acquisition and deep neural network reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. 84, 3192–3205 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Accelerating CEST imaging using a model-based deep neural network with synthetic training data. Magn. Reson. Med. 91, 583–599 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Attention-based MultiOffset deep learning reconstruction of chemical exchange saturation transfer (AMO-CEST) MRI. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 28, 4636–4647 (2024).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III (Springer, 2015).

Hammernik, K. et al. Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data. Magn. Reson. Med. 79, 3055–3071 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Highly-accelerated CEST MRI using frequency-offset-dependent k-space sampling and deep-learning reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. 92, 688–701 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Model-based chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI for robust z-spectrum analysis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 283–293 (2019).

Kwiatkowski, G. & Kozerke, S. Accelerating CEST MRI in the mouse brain at 9.4 T by exploiting sparsity in the Z-spectrum domain. NMR Biomed. 33, e4360 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NeurIPS, 2017).

Zaiß, M., Schmitt, B. & Bachert, P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzian-line-fit analysis of z-spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 211, 149–155 (2011).

Elgavish, R. A. & Twieg, D. B. Improved depiction of small anatomic structures in MR images using Gaussian-weighted spirals and zero-filled interpolation. Magn. Reson. Imaging 21, 103–112 (2003).

Pipe, J. G. Motion correction with PROPELLER MRI: application to head motion and free-breathing cardiac imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 963–969 (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. In Proc. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 286-301 (Springer, 2018).

Van Zijl, P. C. et al. Mechanism of magnetization transfer during on-resonance water saturation. A new approach to detect mobile proteins, peptides, and lipids. Magn. Reson. Med. 49, 440–449 (2003).

Zhao, Y., Sun, C. & Zu, Z. Assignment of molecular origins of NOE signal at− 3.5 ppm in the brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 90, 673–685 (2023).

Uecker, M. et al. ESPIRiT—an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magn. Reson. Med. 71, 990–1001 (2014).

Pruessmann, K. P. et al. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 952–962 (1999).

Fessler, J. A. & Sutton, B. P. Nonuniform fast Fourier transforms using min-max interpolation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 51, 560–574 (2003).

Schröder, C., Börnert, P. & Aldefeld, B. Spatial excitation using variable-density spiral trajectories. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 18, 136–141 (2003).

Lustig, M., Kim, S.-J. & Pauly, J. M. A fast method for designing time-optimal gradient waveforms for arbitrary k-space trajectories. IEEE Trans. Med. imaging 27, 866–873 (2008).

Lewitt, R. M. Multidimensional digital image representations using generalized Kaiser–Bessel window functions. JOSA A 7, 1834–1846 (1990).

Muckley, M. J. et al. TorchKbNufft: A high-level, hardware-agnostic non-uniform fast Fourier transform. In ISMRM Workshop on Data Sampling & Image Reconstruction 22 (ISMRM, 2020).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge the funding supports from Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (11206325, 11102218, 11200422, CityUHK RFS2223-1S02); HMRF (21222621); ITF-MHKJFS (MHP/076/23); InnoHK initiative of the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government - Hong Kong Centre for Cerebro-cardiovascular Health Engineering; City University of Hong Kong (7030012, 9678372, 9229504, 9609321 and 9610616), Institute of Digital Medicine, Tung Biomedical Sciences Centre; State Key Laboratory of Terahertz and Millimeter Waves; The University of Hong Kong (109000487, 204610401 and 204610519); National Key Research and Development Program of China: 2023YFE0210300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Writing – original draft. Z.C., L.H.L., Y.L., Z.W., and J.W.: Data curation and Visualization. Y.Z., D.S., J.H., and K.C.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, and Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Or Perlman] and [Rosamund Daw].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Chen, Z., Law, L.H. et al. Accelerating CEST MRI through complementary undersampling and multi-offset transformer reconstruction. Commun Eng 5, 24 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00580-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00580-6