Abstract

As global progress stalls on the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, robotics has emerged as crucial for sustainability transformation. However, current testbeds limit robotics research by offering either controlled indoor precision or uncontrolled outdoor realism, creating a critical gap. We propose a sustainability-oriented testbed design framework emphasizing multi-environment representation, modular adaptability, and digital twins. Exemplified by the DroneHub, this approach bridges the lab-field divide, enabling experimentation that is vital for robust and responsible robotics aligned with global sustainability targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 9th edition of the Sustainable Development Report (SDR) recently revealed a concerning trend: none of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are on track to be fully achieved by 2030, with only 16% of targets showing measurable progress1. Addressing this shortfall demands transformative strategies, including the development and deployment of innovative technological solutions. Robotics and robotic artificial intelligence (RAI) have emerged as powerful enablers in this context, demonstrating significant impacts across SDG-relevant applications such as forest monitoring2, autonomous infrastructure inspection3, and sustainable agriculture4.

Despite ongoing progress, most robotic initiatives still target individual SDGs, often overlooking the wider ecological, social, and economic impact of their systems5,6. Sustainability Robotics aims to create an integrated framework that accounts for sustainability at every stage of the robotic system, from design to manufacturing, and eventual disposal. Anchored in three key principles, minimal invasiveness, accessibility, and omni-benefit, these robots aim to fit smoothly within natural ecosystems and human-built settings, reducing ecological disturbance, broadening equitable access, and creating shared value for society and the environment. Minimal invasiveness reduces disruption to natural and socio-economic systems through biodegradable materials and human-augmenting rather than replacing designs. Accessibility enables deployment in underserved communities via renewable-powered, physically intelligent robots requiring minimal infrastructure. Omni-benefit transforms extractive approaches into regenerative ones, creating mutualistic relationships where technologies simultaneously restore ecosystems and serve human needs, such as coral restoration robots that monitor marine health.

Achieving this integrated vision requires a shared reevaluation of the purpose and design of robotics testbeds. Specialised research infrastructures are needed to bridge the critical gap between highly controlled indoor laboratories and unpredictable real-world environments. Currently, most existing testbeds provide either precise instrumentation in artificial indoor settings or vast open outdoor spaces with limited experimental control. Very few facilities offer a semi-controlled outdoor environment where robotic systems can undergo realistic yet structured experimentation.

In response, we propose a design framework for sustainability-oriented robotics testbeds. This framework emphasises modularity, adaptability, interdisciplinary co-evolution, and integrated simulation-physical experimentation loops. As a concrete instantiation, we introduce the DroneHub, an outdoor, multi-environment research infrastructure specifically engineered to address this gap. The DroneHub, which is now operational, features modular, reconfigurable zones designed to replicate diverse terrains, structural elements, and ecological contexts, enabling researchers to systematically investigate critical scientific questions at the heart of Sustainability Robotics.

This paper first presents the overarching design principles and architecture of sustainability-oriented testbeds. It then describes the DroneHub as a practical embodiment of this approach, detailing its distinct environments, software framework, and operational dynamics. Finally, the paper discusses how this generalised design methodology can inform broader research infrastructure development, catalysing aerial robotics as a pivotal contributor to sustainable global development.

Foundation for a sustainability-oriented testbed design framework

The establishment of robotics testbeds has been driven by the need to create controlled environments that facilitate the development, testing, and validation of complex robotic systems7. These environments are essential for advancing research in autonomous robots.

Gaps and opportunities in current robotics testbeds

The global landscape of robotics research and development is underpinned by a diverse array of specialised testbeds, which facilitate groundbreaking experimentation and innovation8. These testbeds vary widely in scope and application, ranging from indoor setups designed for precise localisation and control to outdoor and multi-terrain environments that test robots under dynamic and unpredictable conditions. Concentrated in technologically advanced countries, these facilities reflect significant investments in science and engineering and serve as vital platforms for advancing robotics across diverse domains. The following highlights several notable testbeds worldwide, offering context rather than a comprehensive systematic review of the field and illustrating their contributions to advancing robotics research and application.

North America hosts numerous well-established robotic testbeds. A well-known example is the Robotarium9, a remotely accessible testbed that democratises multi-robot research by eliminating traditional barriers related to cost and complexity while ensuring safety through built-in protocols. Another established testbed is Duckietown10, which offers an open-source, low-cost ecosystem for education and research in autonomy, featuring simple robotic vehicles navigating through model urban settings to facilitate learning in perception and control. Similarly, RAVEN (Real-time indoor Autonomous Vehicle test Environment)11 is an indoor testbed focused on autonomous multi-agent missions, streamlining the development process by simplifying hardware and control management to concentrate on high-level task algorithms. Moreover, the GRASP multiple-MAV testbed12 supports coordinated and dynamic flight research using off-the-shelf micro aerial vehicles, advancing studies in group behaviours pertinent to applications like surveillance and reconnaissance.

Europe boasts a strong presence of robotic testbeds in countries like Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and France, supporting research in industrial automation, service robotics, aerial robotics, and human-robot interaction. The Flying Machine Arena13, located in Switzerland, provides a modular and robust framework for experimenting with fleets of aerial robots, enabling rapid prototyping and demonstration of complex control concepts. Additionally, ETH has the new “RobotX” arena under development, which will leverage ETH’s strong expertise in robotics and develop it further in a research and education platform. In Spain, CATEC at the University of Seville features a 15 × 15 × 5 meter indoor testbed with twenty motion capture cameras for aerial robotics and multi-vehicle coordination research. At EPFL, the Laboratory of Intelligent Systems features an instrumented flight arena with an open wind tunnel and high-resolution motion tracking for avian-inspired aerial robotics research14. The United Kingdom has several facilities, such as the ITER Robotics Test Facility (IRTF)15 that helps the Remote Applications in Challenging Environments (RACE) team experiment on nuclear fusion systems’ autonomous maintenance, the National Robotarium16, which has a living lab to experiment with trialling the technology in a realistic home setting, and the multi-terrain arena at Imperial College London to work on multi-modal locomotion17.

In Asia, universities and research institutions have established advanced testbeds in countries such as Japan, China, and South Korea, reflecting the significant contributions from these regions to robotics innovation, particularly in humanoid robotics, manufacturing automation, and autonomous systems. Collectively, these testbeds demonstrate the crucial role of tailored experimental indoor testbeds in advancing robotics research and applications.

Concurrently, large-scale outdoor testing facilities are also crucial for advancing autonomous systems, as they provide diverse, real-world environments for rigorous testing. With expansive airspace and open fields, locations like Schmerlat Airfield18, Pendleton Unmanned Aerial Systems Test Range19, Aviation Innovation Centre20, Barcelona Drone Centre21, Droneport22, and the UAS Denmark Test Centre23 are ideal for developing drones for industrial and commercial applications. Similarly, the CSIRO Flight Operations Centre24 and the Canadian Centre for Field Robotics (CCFR)25 offer vast outdoor areas for research in environmental and agricultural robotics. Testbed Digitalised Agriculture26 specialises in precision farming technologies within controlled agricultural settings, while JPL MarsYard III27 simulates the Martian surface to test robots designed for space exploration.

Although robotics testbeds around the world offer a range of specialised capabilities, a comparative review (Table 1) reveals that common structural gaps persist across both indoor and outdoor facilities. Technical, methodological, and systemic limitations collectively hinder the transition from research prototypes to solutions that can operate at scale in real-world settings.

-

- A fundamental architectural challenge lies in the trade-off between scalability and specificity: while some testbeds offer general applicability across research domains, others prioritise domain-specific configurations at the expense of broader relevance. This tension becomes especially pronounced when attempting to bridge micro-scale precision tasks with large-scale, long-range robotic operations.

-

- Adaptability and environmental diversity remain constrained. Most infrastructures are designed for either indoor precision or outdoor ruggedness, but few can accommodate both. As a result, meaningful research across varied operational domains remains difficult to support within a single facility.

-

- Perhaps most critically, testbeds that introduce real-world complexity often do so at the expense of reproducibility. Environmental factors such as weather, lighting, and seasonal variation introduce stochasticity that undermines experimental control, creating a reproducibility paradox.

-

These technical challenges are further compounded by systemic issues: fragmented benchmarking ecosystems hinder cross-institutional validation; operational costs and obsolescence raise concerns about long-term sustainability; legal and regulatory landscapes present evolving compliance burdens; and institutional coordination and training requirements constrain accessibility and scalability.

These technical, methodological, and systemic limitations highlight the need for a new design paradigm tailored to the demands of sustainability-driven robotics research.

A framework for testbed design in Sustainability Robotics

The emergence of Sustainability Robotics calls for a fundamental rethinking of how robotic systems are designed, tested, and validated. This emerging discipline is not merely about deploying robots in sustainable domains, but about embedding sustainability into the technological, operational, and ethical dimensions of robotics itself. As engineers develop more robots to address pressing societal and ecological challenges, including environmental monitoring, circular construction, adaptive infrastructure, and planetary health, new testbeds must support rigorous, representative, and interdisciplinary experimentation.

Existing testbeds offer highly controlled indoor environments for precise algorithmic validation or expansive outdoor fields for real-world exposure, but few provide the middle ground necessary for transitioning research into deployable sustainability solutions, as it can be seen in Fig. 1. Building on the limitations articulated in the previous section, we propose a design framework for sustainability-oriented robotics testbeds that formalises the architectural, operational, and epistemological requirements for such infrastructures. This framework defines five interdependent design principles:

-

Modular multi-environment architecture: Testbeds should include separate physical and functional zones that mimic key operational settings such as urban, ecological, and industrial areas, and allow rapid reconfiguration of structures, terrain, and embedded infrastructure. This design supports applicability across domains, speeds iteration for varied use cases, and allows for sustainable reuse of the facility.

-

Adaptive representative environments: Environments must reflect authentic outdoor dynamics (e.g., lighting, weather, terrain heterogeneity) while preserving a degree of experimental control for applicability and be flexible to change and adapt their settings. Such realism and flexibility are critical for evaluating robustness, adaptivity, and uncertainty-aware autonomy.

-

Bridging the simulation gap: The testbed should be integrated with digital twin infrastructure and simulation pipelines, enabling continuous transitions between virtual experimentation and physical validation. This allows scalable testing across technology readiness levels while reducing waste and development time, and eases accessibility.

-

Interdisciplinary co-evolution: The testbed should be designed for co-development with adjacent fields such as materials science, environmental sensing, architecture, and policy28. Configurability in physical layout, sensing modalities, and experimental access is essential for transdisciplinary collaboration.

-

Embedded lifecycle metrics: The testbed must natively record sustainability indicators, such as energy use, emissions, waste, safety, and reuse, so that experimental results reveal both task success and the broader environmental and social effects.

The left column shows examples of existing indoor test facilities (e.g., the UK National Robotarium, CSIRO Flight Centre, Duckietown, and UPenn Robotarium) designed for highly controlled conditions and precise benchmarking. The right column illustrates large-scale outdoor sites (e.g., UAS Denmark, Schmerlat Airfield, Pendleton Test Range, and the Barcelona Drone Centre) that provide realistic, often unpredictable environments. In the centre, the DroneHub offers a transitional, semi-controlled outdoor space that blends elements of both environments, enabling researchers to methodically scale up robotic testing from the stability of the lab to the complexity of the real world.

Together, these five principles, which is illustrated in Fig. 2, mark a shift in how we conceptualise testbeds: from static domains optimised for single robot performance to living, reconfigurable infrastructures that enable systems-level innovation. A testbed built on this framework is not merely a proving ground; it becomes a scientific instrument for posing new questions about how robots can act responsibly in complex environments.

In the next section, we introduce the DroneHub as an operational realisation of this framework. By incorporating modular environments, embedded constraints, and simulation-to-real pipelines, the DroneHub offers a structured yet realistic context for experimental research in Sustainability Robotics. It serves as an early exemplar of how robotics testbeds can evolve in response to the systemic demands of sustainability.

The DroneHub: Sustainability Robotics testbed

Building on the design framework from the previous section, the DroneHub serves not just as a physical testing space but as a sustainability-focused scientific instrument, created to enable scalable development, validation, and deployment of robotic systems that advance environmental and societal goals.

The DroneHub is located in the Duebendorf Campus of the Swiss Federal Laboratories of Materials Science and Technology (Empa), occupying the top floor of the Next Evolution of Sustainable Infrastructure (NEST) as its latest unit29.

NEST, which is depicted in Fig. 3, serves as a modular innovation platform designed to accelerate the implementation of sustainable technologies through collaborations between academia and industry. It comprises a central backbone infrastructure to which experimental research units are physically and functionally attached. These units address focused research domains, ranging from digital fabrication to energy systems, and function as fully operational residential and office spaces that are continuously monitored and evaluated. The NEST complex is vertically structured and centrally serviced by shared water, heating, and energy systems, fostering interconnectivity between units.

This unique location enables the DroneHub to operate not only as a physical site for robotic experimentation but as an active component within a broader ecosystem of public engagement, technological innovation, and cohabitation. Its integration into NEST’s highly visible and interdisciplinary setting provides a distinctive platform for testing sustainable robotic systems under authentic infrastructure and usage scenarios.

Framework-aligned research environments

The DroneHub comprises an outdoor flight arena and two indoor spaces depicted in Fig. 3. The “flight arena” has a floor space of 87 m2 and a maximum height of 11 m, allowing drone experiments on two levels. The full-height space is the “Construction Robotics Zone” and has a footprint of 8 by 6 m. The elevated space on top of the “Infrastructure Robotics Interface” is the “Biosphere for Robotics”, which can be observed from Fig. 4. The space is enclosed with a steel structure wrapped in a steel mesh. This structure provides an environment for outdoor drone experiments and complies with the safety requirements of the nearby airport. The “Infrastructure Robotics Interface” is a lightweight timber structure inside the net enclosure. This is used to develop building facade elements to interact with and host aerial robots. A flexible curtain wall facade to the “Construction Robotics Zone” and an identical facade segment facing the Empa campus outside allow for iterative development and testing of the facade prototypes on a full scale. The “Control Room”, which can be seen on the right of the Fig. 5 is embedded in the Nest building adjacent to the AAM wall. It helps the users to monitor and supervise ongoing aerial robot flights in the outdoor arena.

(Center) A close-up look at the example use cases of the biosphere. (Bottom) Several examples of the robotic testbed are depicted for each capability instance for environmental sensing. (1) Bio-inspired morphing wing drone65, (2) Revolving-wing drone92, (3). Flapping-wing microscale drone93, (4) Multi-modal mobility morphobot (M4)66, (5) Hitchhiker multi-modal drone67, (6) TJ-FlyingFish68, (7) Rotorigami94, (8) Soft-bodied aerial robot95, (9) Collision resilient aerial robot96, (10) Bird-inspired perching drone97, (11) Ornithopter-inspired perching drone98, (12) Metamorphic aerial robot99, (13) Seed-inspired soft robot100, (14) Transient biodegradable drone74, (15) Degradable elastomer for soft robotics101.

(Center) The “Aerial AM Wall” lift mechanism hosts three liftable columns with different widths. The modular structure of the mechanism consists of aluminium back plates and horizontal mounting bars that can be deployed as needed. (Bottom) Instances of main features of robotic research to be further developed in the “Construction Robotics Zone” and example landmark robots for each feature. (1) Protocentric aerial manipulation39, (2) Soft-robotic origami arm40, (3) Aeroarms Project102, (4) High-payload co-axial tricopter43, (5). Voliro44, (6) Elios 3 - Flyability45, (7) Modquad46, (8) Reconfigurable architecture system UAV.47, (9) Flight assembled architecture installation UAV48, (10) Aerial AM37, (11) 3D printing with flying robots52, (12) An integrated delta manipulator drone53, (13) Building bridge with flying robots49, (14) SpiderMAV50, (15) ICD/ITKE Research pavilion drone51.

Construction robotics zone

Aerial robots are increasingly contributing to sustainable construction by enabling high-precision inspection, maintenance, and fabrication tasks30. Beyond their established roles in monitoring and data collection31, recent advancements have positioned aerial platforms to perform interactive tasks32,33,34,35 such as spray painting36, damage detection, and additive manufacturing37, technologies that directly enhance structural resilience and extend infrastructure lifespans.

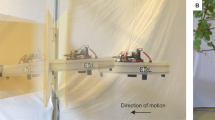

The Construction Robotics Zone within the DroneHub is specifically designed to support research in these domains. At the heart of this zone is the “Aerial AM Wall,” a modular experimental interface that enables a wide range of aerial interactions, from discrete and tensile to continuous material deposition, under semi-controlled yet realistic outdoor conditions (Fig. 5).

The Aerial AM Wall consists of three manually liftable columns, one central column (2 m wide) and two side columns (1 m wide each), mounted on a vertical facade adjacent to the DFAB unit38. These columns host interchangeable horizontal bars onto which modular plates can be attached. Researchers can affix sheets of various materials to this structure to test different fabrication strategies. The wall spans a test area of up to 6 m in height and 4.9 m in width, while maintaining clearances for safe drone operation. The system supports a payload capacity of up to 550 kg, enabling full-scale experimental setups.

Designed with flexibility in mind, the structure accommodates different surface sizes and configurations depending on the experiment. This modularity makes it ideally suited for investigating a wide range of aerial construction and interaction scenarios. Example applications include ad-hoc manipulation with custom arms and grippers39,40,41,42, infrastructure inspection and data collection for BIM and digital twins43,44,45, and aerial additive manufacturing using discrete46,47,48, tensile49,50,51, and continuous methods37,52,53,54,55 with different material types56.

To support feedback-driven experimentation, the wall is being equipped with force sensors and close-range cameras, enabling precise monitoring of aerial contact, adhesion, and material behaviour. This setup facilitates novel testing methods and the real-time evaluation of adaptive algorithms and research questions as follows:

-

- How can real-time feedback systems enhance structural accuracy and environmental adaptability of aerial fabrication?

-

- How do substrate characteristics such as surface texture, porosity, or geometry influence deposition quality and adhesion dynamics?

-

- How can simulation-informed, learning-based frameworks improve the robustness and scalability of AAM processes in diverse outdoor scenarios?

Robotics Biosphere Zone

Today’s environmental challenges, such as biodiversity loss, deforestation, water pollution, and ocean acidification, demand novel sensing and interaction technologies to assess ecosystem dynamics and inform climate models. In particular, monitoring fragile or remote environments requires high-resolution, temporally rich data that traditional methods often fail to capture57,58. Robotics and Artificial Intelligence (RAI) systems offer promising alternatives by automating data collection, improving spatial coverage, and enhancing access to ecologically sensitive areas59,60.

While contributing to these workflows, aerial robots face unique challenges in natural environments. Tasks such as localisation, navigation, perching, and sensor placement within dense vegetation require advanced, adaptive technologies2. Moreover, hardware failures, like crashes or communication loss, pose greater risks to fragile ecosystems61. To prevent environmental harm, the development of biodegradable or even edible components, including sensors, electronics, and structural elements, is essential for promoting circularity and ecological safety62.

To support research in this domain, the DroneHub includes the Robotics Biosphere Zone, a semi-natural, modular test environment for validating aquatic, arboreal, and biodegradable robotic systems. The zone features artificial flora, a configurable soil bed, and a water element, all of which can be rearranged to replicate different ecological scenarios. Branches can be reconfigured to simulate open or dense canopy structures, and soil sub-zones contain diverse substrates such as sand, clay, saline, or alluvial deposits.

Within this environment, researchers can develop and test a wide range of robotic capabilities, including bio-inspired flight strategies for agile, low-noise operation in cluttered spaces63,64,65; multi-modal locomotion across air, water, and ground66,67,68; collision-resilient structures that enhance operational safety and robustness69,70,71; perching and grasping behaviours for sensor deployment or long-term observation72,73; and fully biodegradable platforms designed for environmentally sensitive missions74. The zone also incorporates weather stations and environmental sensors to provide real-time feedback on temperature, humidity, wind, and light; enabling adaptive, closed-loop control under dynamic field-like conditions.

This setup enables the investigation of key scientific questions at the interface of ecology and robotics.

-

- How can sensor fusion and machine learning be leveraged to accurately map biodiversity, soil chemistry, and microclimatic gradients in heterogeneous environments?

-

- In what ways can biodegradable materials and adaptive sensor arrays improve in situ assessments while ensuring minimal disturbance?

-

- How can multimodal sensing architectures that integrate optical, thermal, acoustic, and biochemical data enable long-term, autonomous ecological monitoring in service of sustainable environmental stewardship?

Infrastructure Robotics Interface

As robots become increasingly integrated into everyday life, from autonomous vacuum cleaners and surgical assistants to delivery drones and social robots75,76,77, their potential to interact meaningfully with buildings and urban environments is rapidly expanding. The DroneHub envisions a future in which such robotic systems act as an “immune system” for cities: performing routine inspections, enabling preventive maintenance, and supporting emergency responses to enhance the resilience and longevity of critical infrastructure78.

This vision aligns with the emerging research domain of Human–Robot–Infrastructure (HRI) interaction, which embodies key principles of sustainability robotics. These systems must be accessible and operate in densely inhabited urban environments while generating omnibenefits by optimising resource use, monitoring building health, and minimising disruption to everyday activities. Through sensor fusion, real-time data analytics, and adaptive decision-making, robots can uphold a minimally invasive approach to infrastructure care, enabling cities to become more responsive and efficient45,79.

To facilitate this research, the DroneHub includes the Infrastructure Robotics Interface, a modular testing environment designed to explore physical and digital integration between robots and architectural systems. This zone includes reconfigurable building facade elements developed in collaboration with academic and industrial partners, supporting a broad spectrum of interfacing strategies, from autonomous inspection and perching to wireless energy transfer and payload delivery for emergency response logistics44,80,81. These facades are embedded in a semi-controlled urban context, allowing researchers to replicate complex real-world interaction scenarios while maintaining experimental repeatability (Fig. 6).

(Center) Their modular design allows novel interface facade agents to be designed and developed to host different applications. (Bottom) Examples fitting the development cases of the interface are depicted. (1) Autonomous human-assisting robot75, (2) Social humanoid robot76, (3) Health assistance robot77, (4) Matternet transportation drone103, (5) CityAirbus79, (6) Jedsy transportation VTOL80, (7) FireDrone78, (8) Water rescue drone104, (9) Ambulance drone105, (10) ANYmal106, (11) Sweeping robot107, (12) Gekko solar panel cleaning robot81, (13) KTV window cleaning drone108, (14) Gekko facade cleaning robot81.

Within this environment, researchers can develop and test a range of robotic capabilities tailored to urban infrastructure contexts. These include close-proximity facade navigation and adaptive perching for structural inspection44, energy-efficient path planning in GPS-denied zones, and persistent flight missions enabled by wireless charging systems81. Payload deployment for maintenance or emergency response, autonomous docking procedures, and multi-robot coordination for swarm-based monitoring can also be evaluated. The modular facades further support research on human-aware flight behaviour, data exchange protocols, and digital twin integration for real-time performance tracking and scenario planning.

These experimental capabilities enable fundamental research questions to be addressed:

-

- How can sensor fusion and adaptive decision-making improve infrastructure monitoring by detecting fatigue, inefficiencies, or pollutant buildup while safely navigating dense urban settings?

-

- How can multi-modal perception, informed by architectural constraints and planning insights, support efficient and resilient inspection strategies?

-

- How can feedback loops that integrate structural models, human activity data, and environmental sensing improve robotic maintenance, emergency response, and urban service delivery?

The digital twin: DroneHub cloud

Simulation environment and remote access

We developed a physics-based simulation pipeline to support the design, testing, and validation of aerial robotic systems in the DroneHub testbed. At its core, the simulation stack builds on the PX4 Gazebo simulation framework, extended from the RotorS simulator82, and integrates with ROS2 using consistent topic and parameter conventions. Gazebo provides a robust physics engine, rich library of third-party plugins, real-time sensor emulation capabilities, and open-source accessibility83.

While Gazebo serves as our current foundation, we acknowledge the rapid evolution of simulation technologies and remain open to exploring emerging tools that may better serve sustainability robotics. Future iterations of DroneHub may integrate novel simulation environments that account for sustainability parameters, such as abiotic factors (weather patterns, atmospheric conditions, and terrain characteristics), and biotic data (wildlife behaviour, vegetation dynamics, and ecosystem interactions). Such advanced simulation capabilities could provide more comprehensive environmental modelling to support truly sustainable robotic operations.

Our current high-fidelity DroneHub model supports remote experimentation, and a secure global access infrastructure is under development to democratize participation and enable collaborative research across diverse geographic and institutional contexts.

Data collection, storage, and open-sourcing

Robust data management is a foundational pillar of the DroneHub, supporting reproducible research, system benchmarking, and collaborative development. Our framework is designed to capture, store, and disseminate heterogeneous data streams in line with open science practices and emerging standards in robotics research9,84,85,86,87,88.

Our continuous monitoring system logs:

-

- ROS-native data via rosbag to collect synchronised sensor streams, control commands, and robot state data during all experiments. This includes LiDAR, visual, inertial, and GNSS signals for field deployment scenarios, and motion capture data for structured benchmarking. While motion capture provides high-precision ground truth, our systems are designed to operate independently of such infrastructure, favouring deployment realism through onboard sensing modalities88.

-

- Environmental and interaction data, such as abiotic conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, illumination, precipitation), biotic signals (audio-visual biosphere recordings), and force-feedback from aerial manipulation tasks.

-

- Multi-angle experiment video footage, for qualitative verification, dissemination, and offline annotation.

To ensure experimental reproducibility, each dataset includes structured metadata that records robot count, operational parameters, test duration, risk assessments, and resource consumption while following FAIR data standards principles89.

Inspired by benchmark-setting efforts such as KITTI85, EuRoC MAV84, Robotarium9, and BridgeData88, we have established a dedicated open-access platform90. This portal hosts curated datasets, experiment protocols, simulation environments, and source code, enabling researchers to replicate DroneHub workflows, benchmark algorithms, and contribute their extensions.

Operation and engagement

Ensuring the safe and effective operation of the DroneHub is essential. Our protocol includes detailed user manuals, mandatory safety inductions, and comprehensive risk assessments for all experiments. Manuals for all tools, including the Aerial AM Wall, cover setup, operation, and troubleshooting, and are available both online and on-site.

Prior to access, all users undergo a structured induction covering safety procedures, hazard identification, and emergency protocols. This approach ensures a secure and well-regulated environment for aerial robotics experimentation.

To foster innovation and external collaboration, we offer a three-tier engagement model:

-

Level 1: External users bring their own robots and operate independently.

-

Level 2: External users receive technical support from the DroneHub team during experiments.

-

Level 3: Full integration, where partners use in-house robots (e.g. Fig. 7) with co-development support from our team.

This flexible framework accommodates varying needs, from independent testing to collaborative research, while upholding operational safety and excellence.

Conclusion and outlook

Robotics and robotic artificial intelligence (RAI) are increasingly recognised as transformative technologies with the potential to address some of the most urgent challenges of our time, from climate resilience and sustainable infrastructure to food security and biodiversity loss. Yet to fulfil this promise, the development of robotic systems must extend beyond technical optimisation and embrace principles of sustainability, accessibility, and real-world adaptability. This requires not only rethinking how robots are built and deployed, but also how they are tested, validated, and matured.

This paper has argued for a new generation of robotics testbeds designed explicitly for sustainability-driven research. We introduced a five-principle design framework that redefines testbeds as scientific instruments: modular, reconfigurable, semi-controlled environments that support interdisciplinary experimentation under realistic constraints. The DroneHub serves as an operational realisation of this framework, offering a flexible, outdoor, multi-environment platform where robotic systems can be rigorously evaluated across diverse sustainability-relevant scenarios.

With the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals rapidly approaching, platforms like the DroneHub will be critical enablers, not only for advancing technical readiness but for shaping how we assess, benchmark, and guide the role of robotics in a sustainable future. The ability to conduct structured experiments under real-world ecological and infrastructural conditions will be essential for transitioning robots from controlled environments to systems that operate responsibly in the wild.

Looking ahead, the future of experimental robotics will be shaped by intelligent, interconnected, and inclusive research infrastructures. Digital twins and high-fidelity simulations will enable predictive testing by synchronising virtual models with physical systems, helping to close the longstanding sim-to-real gap. Cloud-based platforms and remote-access interfaces will democratize experimentation, empowering researchers across geographies and institutions to engage with physical testbeds. These environments will increasingly incorporate AI-driven features such as reconfigurable surfaces, interactive agents, and responsive structures, which replicate the complexity and unpredictability of real-world conditions more accurately than static setups. Autonomous maintenance systems, including self-charging and self-diagnosing components, will minimise downtime and ensure continuous operation. Standardised protocols and shared benchmarking frameworks will anchor reproducibility, while federated testbed networks will support distributed, multi-location experimentation at scale. Underpinning these systems, AI-driven orchestration will optimise scheduling, resource allocation, and experiment design, transforming testbeds into self-regulating scientific instruments. Together, these developments promise not only to accelerate the development of robust, adaptive robotic systems but to fundamentally reshape robotics research into a more accessible, responsive, and sustainability-driven enterprise.

Ultimately, we urge the robotics community to see testbeds not only as proving grounds but also as shared research tools, places where engineers, ecologists, designers, and policy makers gather to co-create sustainable technological futures. Through such collaboration, autonomous systems can make meaningful, ethical, and lasting contributions to the challenges that define this century.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sachs, J. D., Lafortune, G. & Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future (SDSN, Dublin University Press, 2024).

Kocer, B. B. et al. Forest Drones for Environmental Sensing and Nature Conservation, 1–8 (IEEE, 2021).

Nwaogu, J. M., Yang, Y., Chan, A. P. & Chi, H.-L. Application of drones in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. Autom. Constr. 150, 104827 (2023).

Shamshiri, R. R. et al. Research and development in agricultural robotics: a perspective of digital farming. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 14, 1–14 (2018).

Guenat, S. et al. Meeting sustainable development goals via robotics and autonomous systems. Nat. Commun. 13, 3559 (2022).

Haidegger, T. et al. Robotics: Enabler and inhibitor of the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 43, 422–434 (2023).

Michael, N., Fink, J. & Kumar, V. Experimental testbed for large multirobot teams. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 15, 53–61 (2008).

Jim´enez-Gonz´alez, A., Martinez-de Dios, J. R. & Ollero, A. Testbeds for ubiquitous robotics: a survey. Robot. Autonomous Syst. 61, 1487–1501 (2013).

Pickem, D. et al. The Robotarium: A Remotely Accessible Swarm Robotics Research Testbed, 1699–1706 (IEEE, 2017).

Paull, L. et al. Duckietown: An Open, Inexpensive and Flexible Platform for Autonomy Education and Research, 1497–1504 (IEEE, 2017).

How, J. P., Behihke, B., Frank, A., Dale, D. & Vian, J. Real-time indoor autonomous vehicle test environment. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 28, 51–64 (2008).

Michael, N., Mellinger, D., Lindsey, Q. & Kumar, V. The grasp multiple micro- UAV testbed. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 17, 56–65 (2010).

Lupashin, S. et al. A platform for aerial robotics research and demonstration: The flying machine arena. Mechatronics 24, 41–54 (2014).

Jeger, S. L., Wu¨est, V., Toumieh, C. & Floreano, D. Adaptive morphing of wing and tail for stable, resilient, and energy-efficient flight of avian-inspired drones. npj Robot. 2, 8 (2024).

ITER Robotics Test Facility — RACE UKAEA — race.ukaea.uk. https://race.ukaea.uk/programmes/iter/ (2016). [Accessed 26-11-2024].

The National Robotarium -UK. https://bayes-centre.ed.ac.uk/access-to-expertise/specialist-areas/space-satellites/space-hub/facilities/robotarium (2022). [Accessed 26-11-2024].

Brahmal Vasudevan Aerial Robotics Lab, Imperial College London. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/aerial-robotics/facilities/ (2017). [Accessed 26-11-2024].

Schaffhausen Schmerlat Airfield. Smart mobility area. https://www.schaffhausen-area.ch/smart-mobility (2025). Accessed: 2025-06-19.

Pendleton UAS Test Range — Infrastructure — Oregon. https://www.pendletonuasrange.com/infrastructure (2014). Accessed 26-11-2024.

The Annexe Goodwood Aerodrome Chichester. Aviation innovation centre. https://aviationinnovationcentre.com/ (2024). Accessed: 2025-06-19.

Barcelona Drone Center — UAV Test Site & Training School. https://www.barcelonadronecenter.com/ (2014). Accessed 26-11-2024.

DronePort NV 2024 - Business park and test center for innovative companies. URL https://droneport.eu/ (2024).

UAS Denmark International Test Center. URL https://uasdenmark.dk/ (2024).

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation - Our facilities. URL https://research.csiro.au/robotics/who-we-are/our-facilities/ (2024).

Canadian Centre for Field Robotics (CCFR). URL https://navigator.innovation.ca/en/facility/york-university/canadian-centre-field-robotics-ccfr. (2013). Accessed 26-11-2024.

RISE Research Institutes of Sweden - Testbed Digitalized Agriculture. URL https://www.ri.se/en/what-we-do/test-demo/digitalizedagriculture. (2019). Accessed 26-11-2024.

JPL Robotics - Facilities: The MarsYard III. URL https://www-robotics.jpl.nasa.gov/how-we-do-it/facilities/marsyard-iii/. (2011). Accessed 26-11-2024.

Miriyev, A. & Kovač, M. Skills for physical artificial intelligence. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 658–660 (2020).

Richner, P., Heer, P., Largo, R., Marchesi, E. & Zimmermann, M. Nest – a platform for the acceleration of innovation in buildings. Inf. Constr. 69, e222 (2017).

Zhou, S. & Gheisari, M. Unmanned aerial system applications in construction: a systematic review. Constr. Innov. 18, 453–468 (2018).

Budiharto, W. et al. Mapping and 3 d modelling using quadrotor drone and GIS software. J. Big Data 8, 1–12 (2021).

Ollero, A., Tognon, M., Suarez, A., Lee, D. & Franchi, A. Past, present, and future of aerial robotic manipulators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 38, 626–645 (2021).

Kocer, B. B. et al. An Intelligent Aerial Manipulator for Wind Turbine Inspection and Repair, 226–227 (IEEE, 2022).

Kaya, Y. F., Orr, L., Kocer, B. B. & Kovac, M. Aerial repair and aerial additive manufacturing. In Infrastructure Robotics: Methodologies, Robotic Systems and Applications 367–384 (IEEE, 2024).

Kaya, Y. F. et al. Aerial additive manufacturing: toward on-site building construction with aerial robots. Sci. Robot. 10, eado6251 (2025).

Vempati, A. S. et al. Paintcopter: an autonomous UAV for spray painting on three-dimensional surfaces. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 3, 2862–2869 (2018).

Zhang, K. et al. Aerial additive manufacturing with multiple autonomous robots. Nature 609, 709–717 (2022).

Graser, K. et al. DFAB house: a comprehensive demonstrator of digital fabrication in architecture. In Fabricate 2020: Making Resilient Architecture 130–140 (UCL Press, 2020).

Tognon, M., Yuksel, B., Buondonno, G. & Franchi, A. Dynamic Decentralized Control for Protocentric Aerial Manipulators, 6375–6380 (IEEE, 2017).

Zhang, K., Zhu, Y., Lou, C., Zheng, P. & Kovac, M. A Design and Fabrication Approach for Pneumatic Soft Robotic Arms using 3d Printed Origami Skeletons, 821–827 (IEEE, 2019).

Stephens, B., Orr, L., Kocer, B. B., Nguyen, H.-N. & Kovac, M. An aerial parallel manipulator with shared compliance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 11902–11909 (2022).

Bodie, K., Brunner, M. & Allenspach, M. Omnidirectional Tilt-Rotor Flying Robots for Aerial Physical Interaction: Modelling, Control, Design and Experiments, vol. 157 (Springer Nature, 2023).

Orr, L., Stephens, B., Kocer, B. B. & Kovac, M. A High Payload Aerial Platform for Infrastructure Repair and Manufacturing, 1–6 (IEEE, 2021).

Voliro solution — Voliro — voliro.com. https://voliro.com/voliro-solution/. (2019). Accessed 05-04-2024.

Elios 3 - Digitizing the inaccessible. http://www.flyability.com. (2022). Accessed 05-04-2024.

Saldana, D., Gabrich, B., Li, G., Yim, M. & Kumar, V. Modquad: The Flying Modular Structure that Self-assembles in Midair, 691–698 (IEEE, 2018).

Wood, D. et al. Cyber Physical Macro Material as a UAV [re] Configurable Architectural System, 320–335 (Springer, 2019).

Augugliaro, F. et al. The flight assembled architecture installation: cooperative construction with flying machines. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 34, 46–64 (2014).

Mirjan, A., Augugliaro, F., D’Andrea, R., Gramazio, F. & Kohler, M. Building a bridge with flying robots. Robot. Fabrication Architecture Art. Des. 2016, 34–47 (2016).

Zhang, K., Chermprayong, P., Alhinai, T., Siddall, R. & Kovac, M. Spidermav: Perching and Stabilizing Micro Aerial Vehicles with Bio-inspired Tensile Anchoring Systems, 6849–6854 (IEEE, 2017).

Vasey, L., Felbrich, B., Prado, M., Tahanzadeh, B. & Menges, A. Physically distributed multi-robot coordination and collaboration in construction: A case study in long span coreless filament winding for fiber composites. Constr. Robot. 4, 3–18 (2020).

Hunt, G., Mitzalis, F., Alhinai, T., Hooper, P. A. & Kovac, M. 3d Printing with Flying Robots, 4493–4499 (IEEE, 2014).

Chermprayong, P., Zhang, K., Xiao, F. & Kovac, M. An integrated delta manipulator for aerial repair: a new aerial robotic system. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 26, 54–66 (2019).

Dams, B. et al. Deposition dynamics and analysis of polyurethane foam structure boundaries for aerial additive manufacturing. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 19, e2305213 (2024).

Dams, B. et al. Fresh properties and autonomous deposition of pseudoplastic cementitious mortars for aerial additive manufacturing. IEEE Access, 12, 34606–34631 (2024).

Dams, B. et al. The rise of aerial additive manufacturing in construction: a review of material advancements. Front. Mater. 11, 1458752 (2025).

Dunbabin, M. & Marques, L. Robots for environmental monitoring: Significant advancements and applications. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 19, 24–39 (2012).

Koh, L. P. & Wich, S. A. Dawn of drone ecology: low-cost autonomous aerial vehicles for conservation. Tropical Conserv. Sci. 5, 121–132 (2012).

Debruyn, D. et al. Medusa: A multi-environment dual-robot for underwater sample acquisition. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 4564–4571 (2020).

Farinha, A., Zufferey, R., Zheng, P., Armanini, S. F. & Kovac, M. Unmanned aerial sensor placement for cluttered environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 6623–6630 (2020).

Heinrich, M. et al. Hygroscopically-driven Transient Actuator for Environmental Sensor Deployment, 1–8 (IEEE, 2023).

Sethi, S. S., Kovac, M., Wiesemu¨ller, F., Miriyev, A. & Boutry, C. M. Biodegradable sensors are ready to transform autonomous ecological monitoring. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1245–1247 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. A biologically inspired, flapping-wing, hybrid aerial-aquatic microrobot. Sci. Robot. 2, eaao5619 (2017).

Ajanic, E., Feroskhan, M., Mintchev, S., Noca, F. & Floreano, D. Bioinspired wing and tail morphing extends drone flight capabilities. Sci. Robot. 5, eabc2897 (2020).

Di Luca, M., Mintchev, S., Heitz, G., Noca, F. & Floreano, D. Bioinspired morphing wings for extended flight envelope and roll control of small drones. Interface focus 7, 20160092 (2017).

Sihite, E., Kalantari, A., Nemovi, R., Ramezani, A. & Gharib, M. Multi-modal mobility morphobot (m4) with appendage repurposing for locomotion plasticity enhancement. Nat. Commun. 14, 3323 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Aerial-aquatic robots capable of crossing the air-water boundary and hitchhiking on surfaces. Sci. Robot. 7, eabm6695 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. TJ-FlyingFish: Design and Implementation of an Aerial-Aquatic Quadrotor with Tiltable Propulsion Units, 7324–7330 (IEEE, 2023).

Liu, Z. & Karydis, K. Toward Impact-resilient Quadrotor Design, Collision Characterization and Recovery Control to Sustain Flight after Collisions, 183–189 (IEEE, 2021).

de Azambuja, R., Fouad, H., Bouteiller, Y., Sol, C. & Beltrame, G. When being Soft makes You Tough: A Collision-resilient Quadcopter Inspired by Arthropods’ Exoskeletons, 7854–7860 (IEEE, 2022).

Bui, S. T. et al. Tombo propeller: bioinspired deformable structure toward collision-accommodated control for drones. IEEE Trans. Robot. 39, 521–538 (2022).

Hauf, F. et al. Learning Tethered Perching for Aerial Robots, 1298–1304 (IEEE, 2023).

Lan, T., Romanello, L., Kovac, M., Armanini, S. F. & Kocer, B. B. Aerial Tensile Perching and Disentangling Mechanism for Long-term Environmental Monitoring. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 3827–3833 (IEEE, 2024).

Wiesemu¨ller, F. et al. Biopolymer cryogels for transient ecology-drones. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2300037 (2023).

Bear Robotics — Servi. https://www.bearrobotics.ai/servi. (2020). Accessed 05-04- 2024.

Pepper Robot - PROVEN Robotics. https://provenrobotics.ai/pepper/. (2014). Accessed 05-04-2024.

Warring, C. Moxi — Diligent Robotics. https://www.diligentrobots.com/blog/meet-moxi-why-we-invested-in-diligent-robotics. (2017). Accessed 05-04-2024.

H¨ausermann, D. et al. Firedrone: multi-environment thermally agnostic aerial robot. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2300101 (2023).

Airbus. CityAirbus NextGen. https://www.airbus.com/en/innovation/energy-transition/hybrid-and-electric-flight/cityairbus-nextgen (2024). Accessed 2025-06-27.

Gliders — jedsy.com. https://jedsy.com/pages/gliders. (2021). Accessed 05-04-2024.

GEKKO Facade Robot. https://www.serbot.ch/en/facades-surfaces-cleaning/gekko-facade-robot. (2013). Accessed 05-04-2024.

Furrer, F., Burri, M., Achtelik, M. & Siegwart, R. RotorS—a modular gazebo mav simulator framework, 4448–4453. URL https://github.com/ethz-asl/rotorssimulator (2016).

Koenig, N. & Howard, A. Design and Use Paradigms for Gazebo, An Open-Source Multi-robot Simulator, Vol. 3, 2149–2154 (IEEE, 2004).

Burri, M. et al. The Euroc micro aerial vehicle datasets. Int. J. Robot. Res. 35, 1157–1163 (2016).

Geiger, A., Lenz, P. & Urtasun, R. Are We Ready for Autonomous Driving? The Kitti Vision Benchmark Suite, 3354–3361 (IEEE, 2012).

Khazatsky, A. et al. DROID: A Large-Scale In-The-Wild Robot Manipulation Dataset. In Proc. Robotics: Science and Systems(RSS), Delft, Netherlands, https://doi.org/10.15607/RSS.2024.XX.120 (2024).

O’Neill, A. et al. Open X-Embodiment: Robotic Learning Datasets and RT-X Models : Open X-Embodiment Collaboration0. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 6892–6903, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA57147.2024.10611477 (2024).

Walke, H. R. et al. BridgeData V2: A dataset for robotlearning at scale. Proc. Conf. Robot Learn. 229, 1723–1736 (2023).

Reijnders, D. et al. Implementing Fair Principles for Robotic Marine Data (IEEE, 2022).

The DroneHub. URL https://sustainability-robotics.squarespace.com/. (2024). Accessed: 2025-01-21.

Block, P. et al. Nest hilo: Investigating lightweight construction and adaptive energy systems. J. Build. Eng. 12, 332–341 (2017).

Bai, S., He, Q. & Chirarattananon, P. A bioinspired revolving-wing drone with passive attitude stability and efficient hovering flight. Sci. Robot. 7, eabg5913 (2022).

Jafferis, N. T., Helbling, E. F., Karpelson, M. & Wood, R. J. Untethered flight of an insect-sized flapping-wing microscale aerial vehicle. Nature 570, 491–495 (2019).

Sareh, P., Chermprayong, P., Emmanuelli, M., Nadeem, H. & Kovac, M. Rotorigami: a rotary origami protective system for robotic rotorcraft. Sci. Robot. 3, eaah5228 (2018).

Nguyen, P. H., Patnaik, K., Mishra, S., Polygerinos, P. & Zhang, W. A soft-bodied aerial robot for collision resilience and contact-reactive perching. Soft Robot. 10, 838–851 (2023).

Briod, A., Kornatowski, P., Zufferey, J.-C. & Floreano, D. A collision-resilient flying robot. J. Field Robot. 31, 496–509 (2014).

Roderick, W. R., Cutkosky, M. R. & Lentink, D. Bird-inspired dynamic grasping and perching in arboreal environments. Sci. Robot. 6, eabj7562 (2021).

Zufferey, R. et al. How ornithopters can perch autonomously on a branch. Nat. Commun. 13, 7713 (2022).

Zheng, P., Xiao, F., Nguyen, P. H., Farinha, A. & Kovac, M. Metamorphic aerial robot capable of mid-air shape morphing for rapid perching. Sci. Rep. 13, 1297 (2023).

Cecchini, L. et al. 4 d printing of humidity-driven seed inspired soft robots. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205146 (2023).

Walker, S. et al. Using an environmentally benign and degradable elastomer in soft robotics. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 1, 124–142 (2017).

Ollero, A. et al. The aeroarms project: Aerial robots with advanced manipulation capabilities for inspection and maintenance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 25, 12–23 (2018).

Matternet. https://www.mttr.net/product. (2011) Accessed 05-04-2024.

Water Rescue Drone TY-3R Flying Lifebuoy. https://didiokmaking.com/products/water-rescue-drone-ty-3r-flying-lifebuoy. (2024). Accessed 05-04-2024.

Claesson, A. et al. Time to delivery of an automated external defibrillator using a drone for simulated out-of-hospital cardiac arrests vs emergency medical services. JAMA 317, 2332–2334 (2017).

ANYmal. https://www.anybotics.com/robotics/anymal/. (2016). Accessed 05-04-2024.

ViaBot Inc. — Sunnyvale. https://www.viabot.com/. (2016). Accessed 05-04-2024.

KTV Working Drone. https://ktvworkingdrone.com/facadecleaning/. (2020). Accessed 05-04-2024.

Lan, T., Romanello, L., Kovac, M., Armanini, S. F. & Bahadir Kocer, B. Aerial Tensile Perching and Disentangling Mechanism for Long-Term Environmental Monitoring. 2024 IEEE International Conference Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 3827–3833, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA57147.2024.10609975 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by internal Empa funding as well as funding from EPSRC (award no./N018494/1, EP/R026173/1, EP/R009953/1, EP/S031464/1, EP/W001136/1), BBSRC (award no. BB/X004988/1), European Research Council Consolidator ProteusDrone (grant no: SERI MB22.00066), the Empa-Imperial College London research partnership, and the EPFL-Empa joint professorship. Mirko Kovac was partially supported by the Royal Society Wolfson fellowship (RSWF/R1/18003) and Yusuf Furkan Kaya is a Turkish Ministry of Education International Higher Education scholar. We would like to thank the other members of the Aerial Robotics Lab, Imperial College London, and the Laboratory of Sustainability Robotics, Empa, and EPFL along Dr Aslan Miriyev for their support and numerous stimulating discussions on this topic. We would also like to thank the project team, each of whom contributed significantly to the realisation of the DroneHub: Dr. Peter Richner, Reto Largo, Enrico Marchesi, Michael Knauss, Reto Fischer, and Christoph Stapfer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and M.K.; investigation, Y.K., D.H., L.O., H.P., M.K.; resources, Y.K., D.H., L.O., H.P. and M.K.; data curation, Y.K., D.H., L.O., H.P.; writing-original draft preparation, Y.K., D.H., L.O., H.P., M.K.; writing-review and editing, Y.K., D.H., L.O., H.P. and M.K.; visualization, Y.K., M.K.; supervision, H.P and M.K.; project administration, Y.K., D.H., and M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaya, Y.F., Häusermann, D., Nguyen, P.H. et al. The DroneHub: a multi-environment testbed for sustainability robotics. npj Robot 4, 9 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00054-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00054-z