Abstract

Field-based reactive control provides a minimalist, decentralized route to guiding robots that lack onboard computation. Such schemes are well suited to resource-limited machines like microrobots, yet implementation artifacts, limited behaviors, and the frequent lack of formal guarantees blunt adoption. Here, we address these challenges with a new geometric approach called artificial spacetimes. We show that reactive robots navigating control fields obey the same dynamics as light rays in general relativity. This surprising connection allows us to adopt techniques from relativity and optics for constructing and analyzing control fields. When implemented, artificial spacetimes guide robots around structured environments, simultaneously avoiding boundaries and executing tasks like rallying or navigation, even when the field itself is static. We augment these capabilities with formal tools for analyzing what robots will do and provide experimental validation with silicon-based microrobots. Combined, this work provides a new framework for generating composed robot behaviors with minimal overhead.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microrobots hold promise for a variety of applications including drug-delivery1,2, environmental remediation3,4, and micro-manufacturing5. However, their small size imposes significant limitations for onboard computation, sensing, and actuation, making many traditional control architectures difficult to implement. As a result, new and unique strategies are required to guide robots too small to see by eye (i.e., sub-mm robots).

Existing microrobot control schemes can be divided into two groups, depending on whether the feedback mechanism is on-robot. In the majority of work, feedback is implemented externally by an auxiliary system that continuously monitors robots and updates forcing fields that guide them toward desired states. These approaches, often implemented using optical tweezers6, electromagnetic actuation7,8,9,10, and/or acoustic fields11,12,13, provide precise and adaptable control, making them well-suited for complex, multi-step tasks or those requiring high accuracy. However, existing implementations struggle with accommodating large numbers of independent microrobots, as many of the forcing fields are hard to spatiotemporally pattern and face trade-offs between resolution and field of view when scaled to large workspaces14,15. Further compounding these challenges is the fact that these approaches often require extensive calibration or bespoke pieces of laboratory equipment to operate.

Reactive control strategies provide a complementary approach that could help address these shortcomings, emphasizing parallelism and decentralization. Rather than relying on continuous external feedback, they use on-robot sensory inputs to immediately modulate the robot’s actions in response to a global control field. This approach is minimalist and well suited to microrobots that often lack sophisticated sensing or computation due to their small size. Common examples are stimuli-responsive micromotors that achieve taxis16, artificial potential fields that coordinate motion through attractive and repulsive forces17, and microrobot swarms whose behavior emerges through collective interactions18,19,20,21. Because each robot executes actions without waiting for a central controller, these approaches reduce implementation overhead and enable microrobots to operate in parallel without individualized tracking and intervention. Furthermore, many microrobots are made from field-responsive engines16,22,23, making reactive control a natural framework.

A major challenge for reactive control is designing fields that promote sophisticated actions. While a variety of work has demonstrated simple behaviors (e.g., taxis)16,24,25, it remains difficult to realize complex tasks like navigating a structured environment or independently guiding multiple trajectories to converge to a desired location using a single, static field. Further, many algorithms for reactive control are heuristic, lacking formal guarantees and suffering from implementation artifacts (e.g., local minima) unless further optimized26,27,28. In cases where control fields do yield desired results, it is challenging to port the solution to a new problem, often requiring fields to be redesigned to match each application.

In this work, we propose a new approach to creating reactive control fields, called artificial spacetimes, which lends itself to addressing some of these issues. This geometric framework allows us rationally construct fields that Braitenberg-like robots29 can use to carry out tasks in structured environments, offers formal methods for analyzing what a robot will do and when, and enables solutions to be reused across problems.

Our starting point is the observation that trajectories of a common class of microrobots are formally equivalent to the path light follows in general relativity30,31. Under these conditions, robots satisfy a generalized ‘Fermat’s Principle’, which can be made clear by treating their coordinates in space and time as the principle dynamical variables. From this point of view, control fields play the role of metric tensors on the manifold of space-time coordinates, defining extremal paths (i.e. geodesics).

The task of controlling these reactive robots becomes tantamount to engineering a metric with geodesics that implement a desired behavior. To do so, we adapt mathematical tools, specialized coordinate transformations, and well-studied metrics from optics and relativity. First, we present metrics that generate primitive behaviors in unobstructed environments. These include navigating to specific locations, confining, diverging, or turning in prescribed ways. We then extended these results to spaces with boundaries by exploiting the invariance of geodesic motion under conformal transformations. Specifically, we conformally map arbitrary, polygonal boundaries to trivial ones and then compose the transformed space with a desired motion-primitive metric. The composite field simultaneously prevents robot collisions with walls and gives instructions for navigation, patrolling, turning, or dispersion without requiring explicit on-robot computation. In addition to theoretical results, we validate this framework through both simulations and experiments with microrobots and draw connections to established results in nonlinear geometric control theory. Combined, these results show a promising new way to extract interesting behaviors from small robots that lack the ability to compute.

Results

In Fig. 1a, we outline the kinematics for a common microrobot design that maps its local sensory inputs to motor speed (also known as a Braitenberg vehicle29). The robot has two motors that each move at their own velocity based on a time-independent sensory intensity I(x, y) (e.g., light intensity) that we assume to be continuous in space, differentiable, and nonnegative. The body of the robot traces a path in two dimensions with curvature κ, proportional to the normalized difference in motor velocities, at a speed VB equal to the average speed of the two motors. Equivalently, the robot’s heading vector rotates at a rate proportional to the difference in engine speeds. Since dynamics at the microscale are almost always overdamped, proportionality between force and velocity is ubiquitous and this model has been successfully applied to a variety of microrobot propulsion mechanisms22,32.

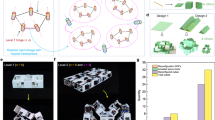

a On top, the kinematics of a robot with two motors, separated by a distance w, that move at speeds VL and VR. The overall body speed VB is given by the average of the motor velocities, and the curvature κ is proportional to the normalized difference in motor velocity. Each velocity is proportional to the control field I, depicted below. The projection of the field gradient in the direction perpendicular to the heading determines how the robot rotates. b Plotted in space and time (vertical axis), robots travel along trajectories connecting cones of accessible spatiotemporal locations. The width of the cone w1 or w2 depends on the velocity of the robot, which in turn is set by the local intensity. c For a specially chosen intensity field that increases linearly from the origin, robots with an initial angle in the range + π/2 → − π/2 are guaranteed to converge, while angles outside of this range escape. d Convergence time for a variety of initial orientations. The black lines are the predicted results for the derived exponential relationship \(r(t)={r}_{0}exp(-t\cos ({\alpha }_{0}))\).

Placed in a spatially varying sensory field, robots turn due to the unequal stimulation of the motors, as depicted in Fig. 1a. We note that despite having no onboard computer or memory system, a robot navigating in this way remains under closed-loop control; the robot takes local measurements of its environment and its speed and direction are modulated in response.

With an eye towards microrobots, we consider the case that the sensory field varies slowly in space relative to the size of the robot. In other words, variation in I takes place over a much larger length scale than the robot’s size. Under this assumption, I can be approximated locally by a Taylor series, leading to a family of equations for the robot’s position xi parameterized by its arc length s:

where \(\epsilon =\left(\begin{array}{ll}0&-1\\ 1&0\end{array}\right)\) is a 90° counter-clockwise rotation matrix and we’ve used the notation xi to compactly represent position (i.e., x1 = x, x2 = y). In all equations, we use Einstein notation, where any repeated index implies summation.

Equations (1) and (2) have several symmetries that suggest a geometric interpretation. First, the dynamics are invariant under I → I/λ, t → tλ; scaling the sensory field changes transit time without changing trajectory shape, a direct consequence of the fact that velocity is proportional to intensity. Second, solutions are invariant under parity and time reversal. That is, a new solution can be generated by sending dxi/ds → − dxi/ds and dt → − dt. As a result, robots can either ascend or descend gradients in intensity, depending on orientation. Finally, both equations are a subset of the ’unicycle’ model, a classic problem in nonlinear geometric control (see methods for a discussion of overlap), suggesting tools from differential geometry could prove useful in analyzing behavior.

In fact, both equations can be given a geometric interpretation, but surprisingly as geodesics in the space-time geometry of relativity. Note, equation (1) is structurally consistent with the general form of a geodesic: the right hand side is quadratic in the coordinate velocities, while the left hand side is an acceleration. Further, equation (2) can be rewritten as I2(x, y)dt2 − dx2 − dy2 = 0 by squaring both sides. This form shows the robot’s next position in space and time is constrained to a cone extending along the temporal axis, a hallmark of Lorentzian geometry30 where time is singled out as a privileged direction (see Methods—Brief Discussion on Manifolds for an informal introduction). The cone’s opening angle varies in space and time, controlled by the sensory field I, and the robot’s trajectory is defined by where these cones meet. Finally, prior work33,34 has shown surprising experimental connections between differential drive macro-scale robots and relativistic physics, suggesting the possibility of a formal relationship.

Together, these observations strongly suggest that the robot’s motion could be derived by minimizing an action on an appropriately curved spacetime. By applying calculus of variations to the metric implied by equation (2), we find this correspondence is exact: the robot’s motion is formally identical to the path light takes in general relativity. We provide a full derivation in the methods (Methods - Deriving Geodesic Equations); briefly, the steps are as follows. We define a 3-vector dxμ = [dt, dx, dy]. These increments are such that they satisfy (2) along the path. Thus, we interpret 0 = ds2 = I2dt2 − dx2 − dy2 as a constraint on the spacetime interval ds2 = dxμgμνdxν where the pseudo-Riemannian metric tensor gμν has nonzero components g00 = I2 for the time-like component and gij = − δij for the two space-like coordinates. The geodesic equations, defined by extremizing the integral of ds2 along a path, yield Equations (1) and (2).

Connecting the path of a reactive control robot to a Lorentzian geodesic brings significant formal structure. One can use known symmetries in the spacetime to predict how long it will take a robot to traverse a path or predict whether a region of space is asymptotically attracting. The geodesic formulation also enables connections to nonlinear geometric control35, with a unique difference that here we can tune the metric (and thus curvature) of the underlying manifold (see Methods for further discussion). Crucially, the numerous tools, intuitions, and solved problems from both relativistic mechanics and ray optics can be appropriated for the task of engineering robot behaviors.

As an example, we analyze a proportional control field intended to guide robots to the origin from the point of view of Lorentzian geodesics. Specifically, we take the sensory field \(I=\sqrt{{x}^{2}+{y}^{2}}=r\) such that each motor’s velocity is proportional to its distance from the target location. Heuristically, this scheme aims to both align robots to the target location and slow them down as they approach.

Using our geometric formalism, we determine the range of initial headings and positions that are guaranteed to arrive at the origin and their rate of convergence. Since this metric depends only on the radial distance, the dynamics conserve both energy E = − r2dt/dλ and angular momentum L = r2dϕ/dλ where λ is an affine parametrization and ϕ is the angle between the robot’s position and the origin. Using these symmetries and the null-affine parametrization dλ = I2dt36, equation (2) simplifies to a first order equation for the radial velocity (Methods - Analysis of the Proportional Metric)

Since the sign of the right hand side of Eq. (3) cannot pass through zero; robots cannot change whether they are headed towards or away from the origin. Indeed, explicitly computing the angular momentum gives \(L=\sin ({\alpha }_{0})\) where α0 is the initial misalignment between the robot’s heading and its radial vector (Methods—Analysis of the Proportional Metric); the phase space is always split between strictly ingoing and outgoing paths. Furthermore, as r is a strictly positive function and its rate of change is strictly negative when a trajectory is initially in-falling, it can be used as a local Lyapunov function to show convergence.

Focusing on the inward falling trajectories, we directly compute the rate of convergence. Integrating Eq. (3), we find \(r(t)={r}_{0}\exp [-t\cos ({\alpha }_{0})]\). In other words, any robot with an initial misalignment between + π/2 and − π/2 converges exponentially fast to the origin, regardless of its initial distance from the target location. Figure 1c, d show simulations of robots compared to the theory, validating the result (Methods—Simulating Robot Trajectories). Trajectories initially facing inward descend the intensity field towards the origin, while outward facing trajectories ascend it, traveling to infinity. No fit parameters are used.

This simple example hints at how Lorentzian geometry can address control problems. Yet, the use of symmetry arguments raises the question of how to handle more realistic geometries. A structured environment like a maze would clearly lack the radial symmetry of an unobstructed position control problem.

This issue can be resolved by leveraging the coordinate invariance of geodesic motion and light-like trajectories31,37. By choosing a new set of coordinates, complex boundaries can be mapped into simple ones, extending the reach of rudimentary control fields. One particularly powerful class of transformations are those that locally preserve angles, or conformal transformations. By definition, a conformal transformation from \(x\to \tilde{x}(x)\) transforms the spacetime interval as \(d{\tilde{s}}^{2}=d{s}^{2}{{\rm{\Omega }}}^{2}(x)\). Because the overall effect on the interval is multiplication by scalar function, a null geodesic in one coordinate system remains a null geodesic in the transformed space. The value arises from the fact that many known conformal transformations map complicated boundaries (e.g., arbitrary polygons) to trivial ones (e.g., a disk). Of note, conformal mapping of geodesics is used extensively in optics to build devices ranging from lenses to mirrors to cloaks31,38,39,40, and transformations can often be generated with computationally efficient algorithms (e.g., root-exponential convergence to solutions)41,42,43 that can be adapted to a range of topologies44,45. As a starting point, in this work we use the Schwarz-Christoffel transform43 which maps arbitrary, closed polygonal boundaries to disks, strips or rectangles.

Conformal invariance presents a two-stage composition procedure for building reactive control fields, illustrated schematically in Fig. 2. First, encode all the boundary information via conformal transformation to a simple virtual space. In virtual space, implement the desired behavior with a control metric. The conformal transformation can then be inverted to map the control law back to physical space, resulting in a composite metric that expresses both the desired behavior and stores information about how to avoid obstacles. We note that the process of converting the complex boundary into an isotropic space is agnostic to the initial position of the robot and is carried out numerically before the experiment starts; the robot only ever experiences the completed, composite field.

Coordinate transformations enable metrics for behaviors to be composed with metrics for boundary avoidance. First, we map a physical space with a complex boundary to a simple virtual space by a conformal transformation. A control metrics is then implemented in virtual space to dictate the robot’s behavior. For example, here robots all travel to a target location. Mapping back to physical space, we produce a composite metric that both encodes the behavior and boundary information in a single scalar field.

As proof of this approach, we simulate robots, governed by equations (1) and (2), navigating non-trivial boundaries under reactive control. Specifically, we demonstrate the task of maze traversal by mapping the maze to a rectangular virtual space, imposing the proportional control metric, and inverting the transform to build the composite control field for physical space (Methods—Generating Intensity Profiles). As seen in Fig. 3a, three robots with different initial positions trace out the maze and reach the target location. While virtual space shows essentially the same behavior as trajectories in Fig. 1c, guiding robots to the goal, the mapping back to physical space adds the missing information needed for robot to avoid collisions with the walls.

a A maze traversal demonstration with an embedded proportional control metric that directs robots to the same target location. For visualization, the control field magnitude is plotted logarithmically. b The hyperbolic plane is mapped into virtual space, causing robots, initialized with the same position and different headings, to diverge and end up in different regions of the maze. The difference between the largest and smallest headings (cyan vs. purple), defined as Δθ, is only 1.06°, and changes as small as 0.06° demonstrate the effect (red vs. blue). c A turning metric directs robots to different sides of the space based on the initial trajectory. In each case, robots use the same static fields, agnostic to their initialization conditions.

This two-stage approach can be used with other virtual space metrics to complete tasks besides position control. For instance, metrics originally developed for optics exist to diverge, confine, rotate, or deflect trajectories46,47,48,49,50,51,52. As a complement to convergence, in Fig. 3b we implement a metric that diverges trajectories by mapping the hyperbolic plane into virtual space. As a result, every point acts like a saddle point, causing robots with the same initial position but small changes in heading (0.06°−1.06°) to reach drastically different locations (Fig. 3b). Similarly, the paths in Fig. 1a and Fig. 1b are characteristic of confinement, showing robots patrolling a circular region53 and focusing them to patrol along a linear path54,55, respectively. Finally, Fig. 3c shows a metric that turns robots by a fixed amount based on their incident heading in virtual space. Mapped to real space, robots turn upon exiting a junction based on their initial pose, each arriving at a unique position despite the fact that they use the same static control field.

As a final test of our framework, we present experimental studies on microscale robots, showing their applicability in the physical world. We fabricate (Methods—Microrobot Fabrication) silicon-based microrobots (Fig. 4a) that use electrokinetic motors in solution to move around their environments23. As in the model, each robot has two motors, made up of discrete arrays of silicon photovoltaics, that move at speeds proportional to incident light intensity (Methods—Microrobot Propulsion). We utilize the optical setup in Fig. 4a to project spatially varying intensity fields on the bottom surface of petri dish that holds the robot (Methods—Experimental Optical Setup), enabling us to establish tunable metrics.

a A silicon-based microrobot with two electrokinetic motors and differential drive kinematics and an optical setup that creates spatially varying intensity fields. b Experimental demonstrations of various control metrics implemented as intensity fields (top) compared to simulation results (bottom). In the 90° and double 90° turning metric experiments, the simulated traces in red most closely match the initial pose of the experimental demonstration above.

Figure 4 b compares several control fields corresponding to oscillatory motion along a linear axis54,55,56, orbiting trajectories53, and fixed-angle turning57,58 with simulated trajectories (Fig. 4b, bottom). We find agreement between the two. For example, the 90° turning metric57,58 rotates our robot’s heading ≈ 82°, with the robot path falling on a simulated geodesic. Aligned comparisons between the simulation and experiments is included as supplementary data as well (Methods - Quantifying Positional Accuracy). As seen in the simulation, the behavior is relatively insensitive to the initial heading and provides approximate 90° turns for a 40° window of entry angles, suggesting this strategy could be deployed without precise knowledge of the robot’s initial orientation.

Metrics can also be directly joined in space, provided they either extrapolate to a constant value or share a boundary with the same overall intensity field values. To demonstrate, we place two 90° turning lenses next to each other (Fig. 4b). Similar to optics where lenses can be added or removed from the beam path to change the overall behavior, the adjacent control gradients yield a composite effect, turning the robot by a full 180°. In addition to being fairly insensitive to the input angle, control metrics can accept a range of input positions while retaining their functionality. For example, in Fig. 4b, robots with initial positions spanning ~33% of the lens width are rotated and output with a much narrower spread (~15% of the width).

Discussion

Artificial spacetimes provide a versatile framework for controlling robots that lack the capacity to compute. Long term, our control strategy could potentially enable microrobots to traverse anatomical structures for drug delivery or cover specific areas in environmental remediation applications without explicit knowledge of the robot’s location. Such results could even find use for microrobots with on-board computation59,60, reducing memory requirements by offloading the information required for navigation into a sensory field.

While here we have focused on a specific robot class (i.e., Braitenberg vehicles in 2D), there are several promising paths towards generalization. One route could extend the metrics to vary in time. Many applications of autonomous robots require multiple, conditioned, sequential steps. As the manifold here is fundamentally spatiotemporal, it may be possible to encode some of these actions as temporal variations in I without losing geodesic structure. Work along this route might target robot-to-robot collision avoidance or sequential exploration of space by causing individual robots to speed up or slow down upon arriving at specific spacetime locations, or be cloaked from one another when in proximity50. Noise could also be included in the robot or metric structure, playing an analog to physical theories like stochastic geodesics61 or stochastic gravity62, respectively. As an added benefit, temporally varying metrics are of interest in related scientific fields, namely optical metamaterials63,64 and experimental analog gravity65. As dynamic or noisy metrics are generally difficult to realize, robots have a unique opportunity to guide scientific explorations by analogy.

A second generalization could expand the robot hardware. While here we use silicon microrobotics with electrokinetic motors, many microrobot platforms have a mapping between propulsion speed and local measurements like chemical concentration66, light intensity67, or temperature68. Provided there is a way to create a spatially varying control field, our two-stage composition procedure can be adopted. Alternatively, the governing geometric principles can be generalized to 3D: in the methods we specify robot dynamics that extend equations (1) and (2) to produce Lorentzian geodesic motion in three spatial dimensions.

A final generalization could allow robots to establish the control field themselves. While here we project the governing metric onto the system, other works have explored how swarms of reactive robots can realize emergent behaviors by creating their own control fields or leveraging interactions18,69,70,71,72,73,74. In this case, the geometry couples to what the robots are doing, making the metric a dynamical variable and moving even closer in spirit to general relativity. While the metric dynamics would likely be different, relativistic mathematical and numerical tools might lend themselves to analyzing and controlling the collectively formed geometry, motion, and behaviors.

Methods

Deriving equations of motion

We derive the equations of motion for a robot with the kinematics shown in Fig. 1a traveling through a spatially varying sensory field. As in the rest of the text, we use Einstein notation to simplify equations, where two repeated indices imply summation (akbk ⇒ Σkakbk). Note, repeated indices are thus arbitrary (akbk = albl). Similarly, we adopt a common convention in physics and electromagnetism, using the same symbol to denote different, related objects depending on the index. Specifically, we use x with no index, with a Roman index, and with a Greek index. When written with no index, x, we refer to the coordinate x. When written with a Roman subscript, xi, we are denoting the position vector with two spatial components x1 = x and x2 = y. Finally, a Greek index, i.e. xμ, indicates a spacetime vector with components x0 = t, x1 = x, x2 = y.

To start the derivation, akin to a differential drive robot, each motor moves at a speed VL or VR. The speed along a path is given as

and the angle ϕ subtended by the robot’s arc length at the center of curvature (ICC) changes at a rate

defining w as the distance from the center of one motor to the center of the other and counterclockwise rotation as positive. We can rewrite equation (5) using the robot’s heading vector \(\chi =[\cos (\theta ),\sin (\theta )]\) where θ is the heading angle with respect to the global coordinate system. By definition of the ICC, dθ = − dϕ, so using the chain rule we get

or equivalently,

where ϵij is a 90° counter-clockwise rotation matrix. That is

Substituting in our definition of \(\frac{d\phi }{dt}\), we put the equations of motion in terms of the motor velocities.

Next, we aim to define these equations in terms of the intensity I. If we assume that the variation in motor speeds comes from a continuous spatial gradient in intensity that is small over the robot’s body (i.e. negligible intensity changes on a size scale smaller than the robot), we can approximate intensity at a point as

To find the average intensity over a motor, we choose \(\Delta {x}_{i}={\epsilon }_{ij}{\chi }_{j}(\frac{w}{2})+{\chi }_{i}u\) where u spans the length, L, of the robot body, i.e. u = [− L/2, L/2]. We then integrate over u to obtain the average intensity on the motor.

The intensity over the other motor can be found by substituting w → − w.

Assuming light intensity is proportional to motor speed, we can substitute IL and IR for VL and VR in equation (9) and equation (10) to get our equations of motion in terms of the intensity,

In the limit that w, L → 0 and using \({\chi }_{i}=\frac{d{x}_{i}}{ds}\), the leading order equations of motion are

We note that in this work we neglect terms of higher order in the robot dimensions (e.g., terms of \({\mathcal{O}}({w}^{2})\)), giving a base model only. Future work could consider extending the results derived here with a robust control framework by treating the neglected higher order terms perturbatively and/or bounding their magnitude and effect on the robot’s trajectory. Moreover, since the base model is Hamiltonian, a number of useful theoretical constructs could be brought to bear to describe the effect of extra terms.

Brief Discussion on Manifolds

To be self-contained, we provide we provide a brief, introductory description of manifolds and Lorentzian manifolds. Those interested in detailed, formal definitions can find them in our references. In particular Brockett35 provides a good overview of manifolds for those with a controls background and Carroll30 is a good first-introduction to manifolds in spacetime.

To motivate the concept of a manifold, we start by looking at the full phase space of equations (1) and (2) in two different ways. One perspective is that they represent a pair of second order nonlinear equations (and thus a four-dimensional Euclidean phase space) subject to a constraint. Yet, constraining a higher dimensional Euclidean embedding space is a perfectly valid definition for a manifold35. Thus, we are also free to take a second perspective and do away with the ‘embedding’ space. Specifically, the constraint equation means the manifold locally has a tangent space of three dimensions, and we are free to consider only the local, 3D patches that stitch together to cover the full manifold. The two concepts are equivalent, but the latter offers a range of useful mathematical tools.

By Lorentzian manifold, we are making a stronger statement, namely that we can impose a pseudo-Riemannian metric (i.e. a bilinear form that takes tangent vectors on the manifold and returns a real scalar) that this metric always has two negative eigenvalues and one positive one (though they may vary in magnitude along the manifold). Note Lorentzian manifolds distinguish one direction (the so-called time-like direction) and the metric is not positive-definite. Given a particular choice of metric, we can then define geodesics as paths between two points that extremize the functional (19). These special trajectories are exactly the original equations of motion (1) and (2).

Finally, we have made no statements regarding the topology of the manifold because it is task dependent. For instance, since we’re free to choose the specific form of the metric, looking at the metric topology is to some degree user-specified. Alternately, if there are regions of the initial physical space that a robot cannot access (e.g. a disk of excluded positions), this will have implications on the topology of the Lorentzian manifold as well. These topological effects would not change the geodesic equations, but will add requirements to the conformal mapping procedure44.

Finding geodesic equations

We follow the standard procedure for deriving the geodesic equation by varying the associated action. gμν is the system’s metric tensor and dxμ = [dt, dx, dy]30. From squaring the speed equation to write I2(x, y)dt2 − dx2 − dy2 = 0, we associate a metric

To get the geodesic equation, we define an affine parameterization of the curve, λ, and vary the action

For the given metric g, a valid affine parameterization is dλ ∝ I2dt = Ids36. Varying the action with respect to the coordinate x,

Using our parameterization of λ, we substitute \(\frac{dt}{d\lambda }=\frac{1}{{I}^{2}}\) and dλ = Ids to get

We apply the chain rule and get

Substituting \(1={\left(\frac{dx}{ds}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{dy}{ds}\right)}^{2}\) on the right hand side,

We can then cancel \(-\frac{1}{I}(\frac{dI}{dx}{(\frac{dx}{ds})}^{2})\) from both sides, leaving

Rearranging, we have the light-like geodesic equation for this space,

The y component follows a similar derivation, leading to the general equation

This is identical to the robot’s equation of motion, equation (1), derived from differential drive kinematics. Similarly, variation with respect to the time coordinate t(λ) directly enforces the null condition (2).

Analysis of the proportional metric

Here we provide a detailed derivation of the region and rate of convergence for the proportional control metric, whose spacetime interval is, in polar coordinates:

We can note immediately that the metric does not have any explicit dependence on t or on ϕ. Thus, the dynamics admit two conserved quantities corresponding to the generalized momentum for these coordinates. Explicitly, if we write the action principle as

Then the momenta \(E={\partial }_{dt/d\lambda }{\mathcal{L}}=-{r}^{2}dt/d\lambda\) and \(L={\partial }_{d\phi /d\lambda }{\mathcal{L}}={r}^{2}d\phi /d\lambda\) are constants of motion.

Rather than explicitly solve the geodesics, we can insert these conserved quantities into the null condition for our geodesics. Such an analysis is standard in relativity, and used to determine closest approach in a two-body problem30. Specifically, inserting the constants of motion to reduce \(-{r}^{2}{\frac{dt}{d\lambda }}^{2}+{\frac{dr}{d\lambda }}^{2}+{r}^{2}{\frac{d\phi }{d\lambda }}^{2}=0\) gives us

Finally, we use the known null-affine parametrization for this metric form36, dλ = I2dt = r2dt to arrive at Eq. (3):

The final steps in our derivation are linking L and E back to robot parameters for comparison. In our explicit affine parametrization, E = − r2dt/(r2dt) = − 1 for all initial placements. For the angular part, we find L = dϕ/dt. To simplify comparison, we can rewrite this result using the heading vector and initial velocity as

Or noting that \(\frac{1}{r}\frac{d\overrightarrow{x}}{dt}\) is the normalized heading of the robot \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\) while \(\overrightarrow{x}/r=\hat{r}\) we can write

where the last line follows as \(\hat{r}\) and \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\) are both unit length.

With the above expressions for L and E we can derive the rate of convergence. Explicitly, Eq. (3), becomes:

We again note that the right hand side of the expression can only reach zero when the robot halts at the origin. Thus, any in-falling trajectory is always in-falling while any out-falling trajectory is always out-falling. Since the sign of dr/dt is fixed from the initial conditions, we can take the square root of both sides and apply the appropriate sign based on initial orientation. The result is simple first order differential equation for the radial coordinate which is easily solved to give the convergence equation from the main text:

As a final comment, we point out that the single-signed nature of convergence is unique to this metric: most others feature a so-called centrifugal barrier in which the conserved angular momentum sets a distance of closest approach. By selecting a proportional metric, we eliminate this problem since the E and L terms in the governing radial equation follow the same functional dependence on R. This eliminates the possibility of a special distance at which dr/dt vanishes, and by extension, precludes turning points.

Simulating robot trajectories

Robot trajectories are simulated using Python’s ’solve_ivp’ differential equation solver. To start, we manually initialize the robot’s position and heading inside the desired geometry in physical space. Then, we locate the motor positions by rotating the heading vector 90° and incrementing by \(\frac{1}{2}w\) (half our simulated inter-motor distance) in each direction. Once we have the motor locations, we map these points to virtual space and calculate the intensity on each motor by taking the magnitude of the mapping function derivative and it multiplying with the virtual space metric. As intensity is directly proportional to velocity, we can calculate \(\frac{dx}{dt}\) and \(\frac{dy}{dt}\) by multiplying with the relevant component of the heading vector

It is also straightforward to calculate the heading change,

At each timestep, these values are calculated and passed to the solver to initialize the next iteration. Notably, this entire simulation takes place in physical space, only utilizing virtual space to look up the corresponding intensity value. For simplicity, we do not currently account for the finite body size and shape of the robot in performing tasks like maze navigation, instead treating the robot as point-like.

Generating intensity profiles

Recent work in transformation optics has demonstrated the capability to guide and control light by building spatially varying index of refraction profiles. Because our robot’s motion is light-like, we can implement these same techniques for robot control. Of note, in this work, there is an inverse relationship between index of refraction and intensity. Light travels slower in a medium with a higher index of refraction, and the robots discussed here travel faster at higher intensity. However, this is simply handled by taking the index of refraction profile n used to guide light and calculating \(\frac{1}{n}\) to build an intensity profile.

Many transformation optics components, such as spherically-symmetric lenses and GRIN lenses, have straightforward functions corresponding to their index of refraction profiles53. To generate these components as an intensity field, we calculate the profile over a grid of points, take the inverse, and map these values to a grayscale image (0-255). Various components are generated in this way and implemented in Fig. 4.

Further, it is well-known in transformation optics how to build an index of refraction profile corresponding to a conformal mapping function f38,39,40. Simply taking the magnitude of the map’s derivative will produce a profile that embeds the coordinate transform, and arbitrary metrics such as proportional controllers can be encoded by multiplying a metric nvirtual with this profile, i.e.

Again, keeping in mind the inverse relationship between n and I, it is straightforward to build an intensity profile that handles both the geometry of the system and the control law.

Microrobot fabrication

Robots are fabricated massively in parallel using standard semiconductor fabrication tools and techniques as previously demonstrated by our group23,75. To start, we take silicon on insulator (SOI) wafers with a 2 micron (p-type) device layer on top of 500 nm insulating silicon dioxide. These two layers sit on 500 microns of handle silicon. We fabricate photovoltaics by diffusing n-type dopants into the silicon device layer using phosphorus-based spin on glass (Filmtronics P509) in a rapid thermal annealer. We plasma etch mesa structures to expose the underlying p-type silicon, conformally deposit silicon dioxide to insulate the entire sample, and form contacts to the p-type and n-type regions by selectively HF etching the oxide and then sputtering titanium and platinum into the holes. Next, we form interconnects between the photovoltaics and the electrodes that act as the robot’s actuator by sputtering titanium and platinum. We encapsulate the entire structure in SU8 for insulation, plasma etch the silicon dioxide layer to define the robot body, and release robots from the SOI by covering the sample in aluminum and underetching the handle silicon with XeF2 vapor. We then dissolve the aluminum support film to free robots into solution.

Microrobot propulsion

The microrobot propulsion scheme used here is outlined in detail in a prior work from our group23. Briefly, each microrobot is made up of two distinct electrokinetic motors consisting of an array of silicon photovoltaics wired in series (Fig. 4a). Each individual motor feeds current into solution proportional to the incident light intensity, forming an electric field along the length of the motor. This electric field causes ions in the solution and double layer around the robot’s body to migrate, generating a fluid flow for propulsion. By modulating the electric field strength using incident optical power, we directly control propulsion speed. In our previous work23, we showed that the relationship between field strength and propulsion speed is linear for these motors, allowing us to simply tie two motors together to obtain standard differential drive kinematics (Fig. 4a).

The key feature, that speed is proportional to stimulus, is common in microrobotics and reproduced across many other propulsion schemes22,32. It is a direct consequence of operating at small sizes where inertial effects are negligible. As an illustration, suppose our robot turns off its motors. Assuming viscous, Stokes drag on the body, it will come to rest under the governing equation \(m\dot{v}=-L\mu \nu\). For a density of 1000kg/m3, size of 100 microns, and choosing the viscosity of water 1mPa ⋅ s, the relaxation timescale would be 10ms. The positional error of fully neglecting inertia would be on the order of a micron, below the resolution limit of the camera.

Experimental optical setup

To form spatially varying intensity fields, we use a commercially available DLP projector (NP-V332W) connected to a computer and display grayscale images corresponding to the control fields. Utilizing the projector’s direct mapping between grayscale pixel value (0-255) and the light intensity, projected fields manifest as spatially varying intensity fields on the bottom surface of the petri dish containing our robots. For imaging, we use a DSLR camera (Canon Mark IV EOS) with a macro lens (Laowa 25 mm f/2.8 2.5–5X Ultra Macro).

Due to the limitations of our optical system and finite turning rate for our robots, we are currently constrained to balance task complexity against workspace size. The robot itself has a finite minimum radius of curvature (set by the on-board electronics and light intensity). As a result, matching its behavior to simulations like those in Fig. 3 would require scaling up the spatial coordinates in the control field. However, in our current form, we are limited by the field of view of our imaging system, restricting us to basic tasks. Experimental realizations could be improved by laser raster scanning, optical holography, or smaller robot designs capable of tighter turns.

Transformation optics components as control fields

In this work, we utilize a GRIN lens and two spherically-symmetric lenses called the Maxwell fisheye and the Eaton lens. Each of these has a well-defined index of refraction profile utilized in transformation optics. As such, we can directly generate these components as intensity fields for the robot by utilizing the inverse relationship between index of refraction and intensity.

The GRIN lens has a central optical axis with an intensity minimum that spans the length of the lens according to the optical profile

where n0 is the baseline index of refraction value (e.g. 1), A is a constant known as the gradient parameter, and s is the distance from the center optical axis. Light oscillates sinusoidally as it travels through the lens with a consistent period.

The first of the spherically symmetric lenses, the Maxwell fisheye, has an optical profile corresponding to the following equation53

where r is the distance from the center point of the lens. Light-like trajectories in these profiles circle the center.

The second spherically symmetric lens is the Eaton lens. It has an approximate profile76 given by \(n(r)\approx {(\frac{2}{r}-1)}^{\frac{\theta }{\theta +\pi }}\) where r is the distance to the center of the lens and theta is the desired turning angle.

Quantifying positional accuracy

We can directly compare our experimental data to simulation results in order to quantify the positional accuracy of this control scheme. To do so, we track the center of mass of a robot traveling through a control field (e.g. the experiments in Fig. 4) and simulate a trajectory with the same starting position/heading. We then upsample the experimental curve, ensuring the same number of points in the simulation and experimental datasets, and compare pointwise to obtain the distance in pixels. Finally, we measure a known distance in the experimental data to determine a scale factor between pixels and microns and apply this to our results to get the plots shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.1.

We note that the difference between the experimental and simulated trajectories is generally small, at worst about 10% of the robot’s body size. These deviations are likely due to two sources. First, while the microrobots are well approximated by differential drive kinematics23, our prior work, there is experimental variability due to fabrication defects and environmental uncertainty, which are difficult to predict or compensate at the microscale. Second, we point out that the experimental and simulated trajectories tend to deviate in the areas where the gradient is largest. As noted in the main text, a fundamental assumption is that the spatial gradients are small relative to the robot’s body, allowing us to average intensity over the engine. Deviations from this assumption would be strongest in high gradient regions.

Extending results to 3D

While in this work we have focused on robots confined to moving in a plane, many of the underlying concepts can be translated to 3D. As an explicit example, consider a robot that moves with a speed fixed by its position

along a heading vector \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\). Treating \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\) as a three dimensional vector, we seek a generalization of equation (1) that preserves the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\) under time evolution, depends on the gradient in I, and acts to turn the robot away from regions of high intensity. These conditions can all be satisfied by choosing:

Heuristically, this equation acts to rotate away from regions where I is large while the cross product ensures the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\) is clearly fixed. To show it represents a good generalization of equation (1) we can consider what happens when the intensity gradients and heading are purely co-planar. In this case, the term \(\overrightarrow{\chi }\times \nabla I=\hat{z}({\chi }_{x}{\partial }_{y}I-{\chi }_{y}{\partial }_{x}I)=\hat{z}{\chi }_{i}{\epsilon }_{ij}{\partial }_{j}I\) while the second cross product reduces to \(-\hat{z}\times \overrightarrow{\chi }={\epsilon }_{ij}{\chi }_{j}\). In other words, when restricted to motion in 2D, we recover Eq. (2) and (1), as anticipated.

To connect this 3D motion to relativistic geodesics in a 3+1 spacetime, we cast the dynamics into a slightly different form by applying the double cross product identity

This result makes it clear that the motion of the robot is to descend gradients in the sensory field, subject to the constraint that it preserves the length of the heading. We then compare this result to geodesic equations resulting from treating eq. (41) as an interval, giving the action principle

Varying with respect to the spatial coordinates gives

Again, using the affine parametrization36dλ = I2dt we find

We now note that \(\frac{dx}{dt}/I={\chi }_{x}\), letting us factor terms on the LHS to yield

After applying the chain rule and re-arranging we find

The same derivation applies for all spatial components. When we merge these results by explicitly writing them in vector form, we reproduce the robot’s governing equation for its heading vector (i.e. eq. (43)) :

Thus, the simple dynamics of a robot following equations (43) and (41) both generalize the 2D motion studied here and are formally identical to light rays in a fully 3+1 dimensional spacetime.

Connections to affine control

The geometric formalism used here has strong connections to geometric control theory and affine control systems, which here we make explicit35.

First, note that equations (1) and (2) are in the same family as the unicycle or differential drive model:

where in this work, we are restricted to control laws of the form u1 = I(x, y) and \({u}_{2}=-\cos [\theta ]{\partial }_{y}I+\sin [\theta ]{\partial }_{x}I\). Thus, general statements about the control of the differential drive model have consequences for control with artificial spacetime.

There are two classic results that manifest themselves. First, nonlinear effects play a central role in achieving controllability for differential drive systems. By extension, linearization-based approaches (e.g., Hartman-Grobman) are ill-suited to describing their qualitative behaviors. Second, there can be obstructions to control that require non-smooth or time varying policies. Accordingly, the analog of a control policy for artificial spacetime (though not the intensity fields) used here are, by construction, non-smooth.

To illustrate the breakdown of linearization effects, we first review what goes wrong for the generic differential drive system. If we linearize equation (50) around a target location of x = y = θ = 0, we find the equation of motion for the y-coordinate drops out:

Interpreted naively, this would imply that we cannot control both position degrees of freedom. Of course, this is wrong: by using a ’parallel parking procedure’, it’s possible to position such a robot anywhere in space. The essential point is that parallel parking is an intrinsically nonlinear operation: it relies upon non-commuting, second order effects. In other words, linearization throws out exactly the terms that are essential for control.

A similar effect happens if one attempts to linearize the artificial spacetime dynamics. Writing out the dynamics parameterized by arc length we find

Again, any attempt to linearize around an angle would introduce a zero mode, necessitating higher order terms.

Moreover, the equation for the angle variable diverges whenever I → 0. Since equation (2) implies that these are the only locations where robots can come to rest, theorems that assume differentiable vector fields generally cannot be applied to analyze stability. Indeed, this divergence is a necessary condition for controlling the robot in the first place: Brockett’s theorem77 establishes that a differential drive system cannot be stabilized by a C1, static feedback mechanism. We explicitly break the smoothness condition, since the feedback policy diverges at any candidate rest position for the robot. Indeed, similar divergences have been explored in prior work78 on wheeled systems.

Finally we point out that our results can be put in the typical form of geometric control by working with the Hamiltonian formulation of the geodesic equation. Given the action (19), Hamiltonian’s equations of motion give:

This form makes it clear that the robot’s dynamics define a drift-less affine control problem where the conjugate momentum plays the role of the so called ’action variables’ and the metric tensor gives the ’velocity fields’. A notable difference is that typically in affine control one assumes fixed velocity vector fields and adjusts the ’action variables’. Here, the situation is reversed: we have freedom in adjusting the form of velocity fields themselves, but are subject to a fixed structure in the control policy (namely the dynamic equation for the conjugate momentum). Results from the main manuscript can also be rephrased in geometric control language. For instance, symmetries like angular momentum conservation correspond to vector fields Kμ(x) where Kμ(x)pμ is a conserved along a geodesic (i.e., Killing vector fields). By enforcing a metric with this symmetry (e.g., the proportional control metric), we are in effect imposing a constraint on the control variables pμ. Such insight could be useful in reverse engineering new metrics to better match existing results from the affine control literature.

Code availability

Code to simulate robot trajectories will be hosted on Github (https://github.com/whreinhardt/).

References

Nelson, B. J., Kaliakatsos, I. K. & Abbott, J. J. Microrobots for minimally invasive medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 12, 55–85 (2010).

Iacovacci, V., Diller, E., Ahmed, D. & Menciassi, A. Medical microrobots. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 26, 561-591 (2024).

Zarei, M. & Zarei, M. Self-propelled micro/nanomotors for sensing and environmental remediation. Small 14, 1800912 (2018).

Urso, M., Ussia, M. & Pumera, M. Smart micro-and nanorobots for water purification. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 1, 236–251 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Liu, J., Dai, C. & Sun, Y. Robotic micromanipulation: fundamentals and applications. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2, 181–203 (2019).

Zhang, D., Barbot, A., Lo, B. & Yang, G.-Z. Distributed force control for microrobot manipulation via planar multi-spot optical tweezer. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2000543 (2020).

Diller, E., Giltinan, J. & Sitti, M. Independent control of multiple magnetic microrobots in three dimensions. Int. J. Robot. Res. 32, 614–631 (2013).

Ghosh, A. & Fischer, P. Controlled propulsion of artificial magnetic nanostructured propellers. Nano Lett. 9, 2243–2245 (2009).

Frutiger, D. R., Vollmers, K., Kratochvil, B. E. & Nelson, B. J. Small, fast, and under control: wireless resonant magnetic micro-agents. Int. J. Robot. Res. 29, 613–636 (2010).

Khalil, I. S. M., Pichel, M. P., Abelmann, L. & Misra, S. Closed-loop control of magnetotactic bacteria. Int. J. Robot. Res. 32, 637–649 (2013).

Ahmed, D. et al. Selectively manipulable acoustic-powered microswimmers. Sci. Rep. 5, 9744 (2015).

Ahmed, D., Dillinger, C., Hong, A. & Nelson, B. J. Artificial acousto-magnetic soft microswimmers. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2, 1700050 (2017).

Del Campo Fonseca, A. et al. Ultrasound trapping and navigation of microrobots in the mouse brain vasculature. Nat. Commun. 14, 5889 (2023).

Jiang, J., Yang, Z., Ferreira, A. & Zhang, L. Control and autonomy of microrobots: recent progress and perspective. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2100279 (2022).

Chowdhury, S., Jing, W. & Cappelleri, D. J. Controlling multiple microrobots: recent progress and future challenges. J. Micro-Bio Robot. 10, 1–11 (2015).

You, M., Chen, C., Xu, L., Mou, F. & Guan, J. Intelligent Micro/nanomotors with Taxis. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 3006–3014 (2018).

Kim, H. & Kim, M. J. Electric field control of bacteria-powered microrobots using a static obstacle avoidance algorithm. IEEE Trans. Robot. 32, 125–137 (2016).

Ceron, S., Gardi, G., Petersen, K. & Sitti, M. Programmable self-organization of heterogeneous microrobot collectives. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2221913120 (2023).

Ji, F., Wu, Y., Pumera, M. & Zhang, L. Collective behaviors of active matter learning from natural taxes across scales. Adv. Mater. 35, 2203959 (2023).

Gardi, G., Ceron, S., Wang, W., Petersen, K. & Sitti, M. Microrobot collectives with reconfigurable morphologies, behaviors, and functions. Nat. Commun. 13, 2239 (2022).

Wang, H. & Pumera, M. Coordinated behaviors of artificial micro/nanomachines: from mutual interactions to interactions with the environment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 3211–3230 (2020).

Pellicciotta, N. et al. Light controlled biohybrid microbots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214801 (2023).

Hanson, L. C., Reinhardt, W. H., Shrager, S., Sivakumar, T. & Miskin, M. Z. Electrokinetic propulsion for electronically integrated microscopic robots. PNAS 122, e2500526122 (2025).

Zhuang, J., Wright Carlsen, R. & Sitti, M. pH-taxis of biohybrid microsystems. Sci. Rep. 5, 11403 (2015).

Gao, C., Feng, Y., Wilson, D. A., Tu, Y. & Peng, F. Micro-nano motors with taxis behavior: principles, designs, and biomedical applications. Small 18, 2106263 (2022).

Rafai, A. N. A., Adzhar, N. & Jaini, N. I. A review on path planning and obstacle avoidance algorithms for autonomous mobile robots. J. Robot. 2022, 2538220 (2022).

Rehman, A. u., Tanveer, A., Ashraf, M. T. & Khan, U. Motion planning for autonomous ground vehicles using artificial potential fields: A Review http://arxiv.org/abs/2310.14339 (2023).

Duhé, J.-F., Victor, S. & Melchior, P. Contributions on artificial potential field method for effective obstacle avoidance. Fract. Calculus Appl. Anal. 24, 421–446 (2021).

Hotton, S. & Yoshimi, J.The Open Dynamics of Braitenberg Vehicles (MIT Press, 2024).

Carroll, S.Spacetime and geometry: an introduction to general relativity (Addison Wesley, 2004).

Leonhardt, U. & Philbin, T. G. Transformation optics and the geometry of light http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.4778 ArXiv:0805.4778 [physics] (2008).

Yang, Z. et al. SerpenBot, a Laser Driven Locomotive Microrobot for Dry Environments using Learning Control. In 2022 International Conference on Manipulation, Automation and Robotics at Small Scales (MARSS), 1–6 https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9870255/ (2022).

Li, S. et al. A robophysical model of spacetime dynamics. Sci. Rep. 13, 21589 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Field-mediated locomotor dynamics on highly deformable surfaces. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2113912119 (2022).

Brockett, R. The early days of geometric nonlinear control. Automatica 50, 2203–2224 (2014).

Visser, M. Efficient computation of null affine parameters http://arxiv.org/abs/2211.07835 (2023).

Post, E. J. Formal Structure of Electromagnetics: General Covariance and Electromagnetics (Courier Corporation, 1997).

Leonhardt, U. Optical conformal mapping. Science 312, 1777–1780 (2006).

Xu, L. & Chen, H. Conformal transformation optics. Nat. Photonics 9, 15–23 (2015).

Turpin, J. P., Massoud, A. T., Jiang, Z. H., Werner, P. L. & Werner, D. H. Conformal mappings to achieve simple material parameters for transformation optics devices. Opt. Express 18, 244–252 (2010).

Trefethen, L. N. Numerical conformal mapping with rational functions. Comput. Methods Funct. Theory 20, 369–387 (2020).

Driscoll, T. A. & Trefethen, L. N. Schwarz-Christoffel Mapping. Cambridge Monographs on Applied and Computational Mathematics https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/schwarzchristoffel-mapping/E8439E14F3CFE0F8CC2943217A5CA4C4 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002).

Driscoll, T. A. Algorithm 756: a MATLAB toolbox for Schwarz-Christoffel mapping. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 22, 168–186 (1996).

Hu, C. Algorithm 785: a software package for computing Schwarz-Christoffel conformal transformation for doubly connected polygonal regions. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 24, 317–333 (1998).

Kharevych, L., Springborn, B. & Schröder, P. Discrete conformal mappings via circle patterns. ACM Trans. Graph. 25, 412–438 (2006).

Xiong, S., Feng, Y., Jiang, T. & Zhao, J. Designing retrodirective reflector on a planar surface by transformation optics. AIP Adv. 3, 012113 (2013).

Gallina, I., Castaldi, G. & Galdi, V. Transformation media for thin planar retrodirective reflectors. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 7, 603–605 (2008).

Nazarzadeh, F. & Heidari, A. A. Wideband flat reflector antenna based on conformal transformation optics. Optik 264, 169429 (2022).

Liang, L. & Hum, S. V. Wide-angle scannable reflector design using conformal transformation optics. Opt. Express 21, 2133–2146 (2013).

Lee, K.-T., Ji, C., Iizuka, H. & Banerjee, D. Optical cloaking and invisibility: from fiction toward a technological reality. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 231101 (2021).

Sun, F. et al. Transformation optics: from classic theory and applications to its new branches. Laser Photonics Rev. 11, 1700034 (2017).

Alitalo, P. & Tretyakov, S. Electromagnetic cloaking with metamaterials. Mater. Today 12, 22–29 (2009).

Tyc, T., Herzánová, L., Šarbort, M. & Bering, K. Absolute instruments and perfect imaging in geometrical optics. N. J. Phys. 13, 115004 (2011).

Gomez-Reino, C., Perez, M., Bao, C. & Flores-Arias, M. Design of GRIN optical components for coupling and interconnects. Laser Photonics Rev. 2, 203–215 (2008).

Bouchard, S. & Thibault, S. GRIN planar waveguide concentrator used with a single axis tracker. Opt. Express 22, A248–A258 (2014).

Hecht, E.Optics, 5 edn (Pearson Education, Inc., 2017).

Zhao, C.-H. Analytic solution for an eaton lens for rotating 90°. Curr. Opt. Photonics 4, 326–329 (2020).

Li, J. Y. The 90° rotating Eaton lens synthesized by metasurfaces. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8367795.

Xu, L. et al. A 210x340x50 μm Integrated CMOS System for Micro-Robots with Energy Harvesting, Sensing, Processing, Communication and Actuation. In 2022 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), vol. 65, 1–3 https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9731743/references#references (2022).

Reynolds, M. F. et al. Microscopic robots with onboard digital control. Sci. Robot. 7, eabq2296 (2022).

Cruzeiro, A. B. & Zambrini, J.-C. Stochastic geodesics http://arxiv.org/abs/2007.05291 (2020).

Moffat, J. W. Stochastic gravity. Phys. Rev. D. 56, 6264–6277 (1997).

Engheta, N. Four-dimensional optics using time-varying metamaterials. Science 379, 1190–1191 (2023).

Leonhardt, U. & Philbin, T. G. Transformation optics and the geometry of light. In Progress in Optics, vol. 53, 69–152 (Elsevier, 2009).

Barcelo, C., Liberati, S. & Visser, M. Analogue gravity. Living Rev. Relativ. 14, 1–159 (2011).

Feng, Y., An, M., Liu, Y., Sarwar, M. T. & Yang, H. Advances in chemically powered micro/nanorobots for biological applications: a review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2209883 (2023).

Leonardo, R. D. et al. Biohybrid microbots driven by light. In Optical Trapping and Optical Micromanipulation XX, vol. PC12649, PC126490B https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/PC12649/PC126490B/Biohybrid-microbots-driven-by-light/10.1117/12.2682753.full (SPIE, 2023).

Ji, Y. et al. Thermoresponsive polymer brush modulation on the direction of motion of phoretically driven Janus micromotors. Angew. Chem. 131, 4228–4232 (2019).

Defay, J. A., Nilles, A. Q. & Petersen, K. Characterization of the design space of collective Braitenberg vehicles. In International Symposium on Distributed Autonomous Robotic Systems, 257–272 (Springer, 2022).

Gauci, M., Chen, J., Li, W., Dodd, T. J. & Groç, R. Self-organized aggregation without computation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 33, 1145–1161 (2014).

Sinigaglia, C., Manzoni, A., Braghin, F. & Berman, S. Indirect optimal control of advection-diffusion fields through distributed robotic swarms. IFAC-PapersOnLine 55, 299–304 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Autonomous environment-adaptive microrobot swarm navigation enabled by deep learning-based real-time distribution planning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 480–493 (2022).

Beal, J. & Viroli, M. Aggregate Programming: From Foundations to Applications. In Bernardo, M., De Nicola, R. & Hillston, J. (eds.) Formal Methods for the Quantitative Evaluation of Collective Adaptive Systems, vol. 9700, 233–260 http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-34096-8_8 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Ferrari, S., Foderaro, G., Zhu, P. & Wettergren, T. A. Distributed optimal control of multiscale dynamical systems: a tutorial. IEEE Control Syst. 36, 102–116 (2016).

Miskin, M. Z. et al. Electronically integrated, mass-manufactured, microscopic robots. Nature 584, 557–561 (2020).

Kim, S.-H. Retroreflector approximation of a generalized Eaton lens. J. Mod. Opt. 59, 839–842 (2012).

Brockett, R. W. et al. Asymptotic stability and feedback stabilization. Differential Geometric Control Theory 27, 181–191 (1983).

Aicardi, M., Casalino, G., Bicchi, A. & Balestrino, A. Closed loop steering of unicycle like vehicles via Lyapunov techniques. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2, 27–35 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank Professor Nader Engheta, Professor Nikolai Matni, Caroline Zhao, and Jordan Shegog for helpful discussions. We also thank our anonymous reviewers for numerous insightful comments. This work was supported by the Army Research Office (ARO YIP W911NF-17-S-0002), the Sloan Foundation, the Packard Foundation, and was carried out at the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, which is supported by the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program under grant NNCI-2025608.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.H.R and M.Z.M designed the research. W.H.R fabricated the robots, wrote the simulation, performed experiments, and analyzed data. M.Z.M conceived of the original idea, developed the theory, and supervised research. W.H.R and M.Z.M wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reinhardt, W.H., Miskin, M.Z. Artificial spacetimes for reactive control of resource-limited robots. npj Robot 3, 39 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00058-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00058-9